| Next Part | Main Index |

The publishers are grateful to the estate of Miss Jennie Hall and to her many friends for assistance in planning the publication of this book. Especial thanks are due to Miss Nell C. Curtis of the Lincoln School, New York City, for helping to finish Miss Hall's work of choosing the pictures, and to Miss Irene I. Cleaves of the Francis Parker School, Chicago, who wrote the captions. It was Miss Katharine Taylor, now of the Shady Hill School, Cambridge, who brought these stories to our attention.

Do you like to dig for hidden treasure? Have you ever found Indian arrowheads or Indian pottery? I knew a boy who was digging a cave in a sandy place, and he found an Indian grave. With his own hands he uncovered the bones and skull of some brave warrior. That brown skull was more precious to him than a mint of money. Another boy I knew was making a cave of his own. Suddenly he dug into an older one made years before. He crawled into it with a leaping heart and began to explore. He found an old carpet and a bit of burned candle. They proved that some one had lived there. What kind of a man had he been and what kind of life had he lived—black or white or red, robber or beggar or adventurer? Some of us were walking in the woods one day when we saw a bone sticking out of the ground. Luckily we had a spade, and we set to work digging. Not one moment was the tool idle. First one bone and then another came to light and among them a perfect horse's skull. We felt as though we had rescued Captain Kidd's treasure, and we went home draped in bones.

Suppose that instead of finding the bones of a horse we had uncovered a gold-wrapped king. Suppose that instead of a deserted cave that boy had dug into a whole buried city with theaters and mills and shops and beautiful houses. Suppose that instead of picking up an Indian arrowhead you could find old golden vases and crowns and bronze swords lying in the earth. If you could be a digger and a finder and could choose your find, would you choose a marble statue or a buried bakeshop with bread two thousand years old still in the oven or a king's grave filled with golden gifts? It is of such digging and such finding that this book tells.

POMPEII1. The Greek Slave and the Little Roman Boy 2. Vesuvius Pictures of Pompeii:Peristyle of the House of the Vettii |

Ariston, the Greek slave, was busily painting. He stood in a little room with three smooth walls. The fourth side was open upon a court. A little fountain splashed there. Above stretched the brilliant sky of Italy. The August sun shone hotly down. It cut sharp shadows of the columns on the cement floor. This was the master's room. The artist was painting the walls. Two were already gay with pictures. They showed the mighty deeds of warlike Herakles. Here was Herakles strangling the lion, Herakles killing the hideous hydra, Herakles carrying the wild boar on his shoulders, Herakles training the mad horses. But now the boy was painting the best deed of all—Herakles saving Alcestis from death. He had made the hero big and beautiful. The strong muscles lay smooth in the great body. One hand trailed the club. On the other arm hung the famous lion skin. With that hand the god led Alcestis. He turned his head toward her and smiled. On the ground lay Death, bruised and bleeding. One batlike black wing hung broken. He scowled after the hero and the woman. In the sky above him stood Apollo, the lord of life, looking down. But the picture of the god was only half finished. The figure was sketched in outline. Ariston was rapidly laying on paint with his little brushes. His eyes glowed with Apollo's own fire. His lips were open, and his breath came through them pantingly.

"O god of beauty, god of Hellas, god of freedom, help me!" he half whispered while his brush worked.

For he had a great plan in his mind. Here he was, a slave in this rich Roman's house. Yet he was a free-born son of Athens, from a family of painters. Pirates had brought him here to Pompeii, and had sold him as a slave. His artist's skill had helped him, even in this cruel land. For his master, Tetreius, loved beauty. The Roman had soon found that his young Greek slave was a painter. He had said to his steward:

"Let this boy work at the mill no longer. He shall paint the walls of my private room."

So he had talked to Ariston about what the pictures should be. The Greek had found that this solemn, frowning Roman was really a kind man. Then hope had sprung up in his breast and had sung of freedom.

"I will do my best to please him," he had thought. "When all the walls are beautiful, perhaps he will smile at my work. Then I will clasp his knees. I will tell him of my father, of Athens, of how I was stolen. Perhaps he will send me home."

Now the painting was almost done. As he worked, a thousand pictures were flashing through his mind. He saw his beloved old home in lovely Athens. He felt his father's hand on his, teaching him to paint. He gazed again at the Parthenon, more beautiful than a dream. Then he saw himself playing on the fishing boat on that terrible holiday. He saw the pirate ship sail swiftly from behind a rocky point and pounce upon them. He saw himself and his friends dragged aboard. He felt the tight rope on his wrists as they bound him and threw him under the deck. He saw himself standing here in the market place of Pompeii. He heard himself sold for a slave. At that thought he threw down his brush and groaned.

But soon he grew calmer. Perhaps the sweet drip of the fountain cooled his hot thoughts. Perhaps the soft touch of the sun soothed his heart. He took up his brushes again and set to work.

"The last figure shall be the most beautiful of all," he said to himself. "It is my own god, Apollo."

So he worked tenderly on the face. With a few little strokes he made the mouth smile kindly. He made the blue eyes deep and gentle. He lifted the golden curls with a little breeze from Olympos. The god's smile cheered him. The beautiful colors filled his mind. He forgot his sorrows. He forgot everything but his picture. Minute by minute it grew under his moving brush. He smiled into the god's eyes.

Meantime a great noise arose in the house. There were cries of fear. There was running of feet.

"A great cloud!" "Earthquake!" "Fire and hail!" "Smoke from hell!" "The end of the world!" "Run! Run!"

And men and women, all slaves, ran screaming through the house and out of the front door. But the painter only half heard the cries. His ears, his eyes, his thoughts were full of Apollo.

For a little the house was still. Only the fountain and the shadows and the artist's brush moved there. Then came a great noise as though the sky had split open. The low, sturdy house trembled. Ariston's brush was shaken and blotted Apollo's eye. Then there was a clattering on the cement floor as of a million arrows. Ariston ran into the court. From the heavens showered a hail of gray, soft little pebbles like beans. They burned his upturned face. They stung his bare arms. He gave a cry and ran back under the porch roof. Then he heard a shrill call above all the clattering. It came from the far end of the house. Ariston ran back into the private court. There lay Caius, his master's little sick son. His couch was under the open sky, and the gray hail was pelting down upon him. He was covering his head with his arms and wailing.

"Little master!" called Ariston. "What is it? What has happened to us?" "Oh, take me!" cried the little boy.

"Where are the others?" asked Ariston.

"They ran away," answered Caius. "They were afraid, Look! O-o-h!"

He pointed to the sky and screamed with terror.

Ariston looked. Behind the city lay a beautiful hill, green with trees. But now from the flat top towered a huge, black cloud. It rose straight like a pine tree and then spread its black branches over the heavens. And from that cloud showered these hot, pelting pebbles of pumice stone.

"It is a volcano," cried Ariston.

He had seen one spouting fire as he had voyaged on the pirate ship.

"I want my father," wailed the little boy.

Then Ariston remembered that his master was away from home. He had gone in a ship to Rome to get a great physician for his sick boy. He had left Caius in the charge of his nurse, for the boy's mother was dead. But now every slave had turned coward and had run away and left the little master to die.

Ariston pulled the couch into one of the rooms. Here the roof kept off the hail of stones.

"Your father is expected home to-day, master Caius," said the Greek. "He will come. He never breaks his word. We will wait for him here. This strange shower will soon be over."

So he sat on the edge of the couch, and the little Roman laid his head in his slave's lap and sobbed. Ariston watched the falling pebbles. They were light and full of little holes. Every now and then black rocks of the size of his head whizzed through the air. Sometimes one fell into the open cistern and the water hissed at its heat. The pebbles lay piled a foot deep all over the courtyard floor. And still they fell thick and fast.

"Will it never stop?" thought Ariston.

Several times the ground swayed under him. It felt like the moving of a ship in a storm. Once there was thunder and a trembling of the house. Ariston was looking at a little bronze statue that stood on a tall, slender column. It tottered to and fro in the earthquake. Then it fell, crashing into the piled-up stones. In a few minutes the falling shower had covered it.

Ariston began to be more afraid. He thought of Death as he had painted him in his picture. He imagined that he saw him hiding behind a column. He thought he heard his cruel laugh. He tried to look up toward the mountain, but the stones pelted him down. He felt terribly alone. Was all the rest of the world dead? Or was every one else in some safe place?

"Come, Caius, we must get away," he cried. "We shall be buried here."

He snatched up one of the blankets from the couch. He threw the ends over his shoulders and let a loop hang at his back. He stood the sick boy in this and wound the ends around them both. Caius was tied to his slave's back. His heavy little head hung on Ariston's shoulder. Then the Greek tied a pillow over his own head. He snatched up a staff and ran from the house. He looked at his picture as he passed. He thought he saw Death half rise from the ground. But Apollo seemed to smile at his artist.

At the front door Ariston stumbled. He found the street piled deep with the gray, soft pebbles. He had to scramble up on his hands and knees. From the house opposite ran a man. He looked wild with fear. He was clutching a little statue of gold. Ariston called to him, "Which way to the gate?"

But the man did not hear. He rushed madly on. Ariston followed him. It cheered the boy a little to see that somebody else was still alive in the world. But he had a hard task. He could not run. The soft pebbles crunched under his feet and made him stumble. He leaned far forward under his heavy burden. The falling shower scorched his bare arms and legs. Once a heavy stone struck him on his cushioned head, and he fell. But he was up in an instant. He looked around bewildered. His head was ringing. The air was hot and choking. The sun was gone. The shower was blinding. Whose house was this? The door stood open. The court was empty. Where was the city gate? Would he never get out? He did not know this street. Here on the corner was a wine shop with its open sides. But no men stood there drinking. Wine cups were tipped over and broken on the marble counter. Ariston stood in a daze and watched the wine spilling into the street.

Then a crowd came rushing past him. It was evidently a family fleeing for their lives. Their mouths were open as though they were crying. But Ariston could not hear their voices. His ears shook with the roar of the mountain. An old man was hugging a chest. Gold coins were spilling out as he ran. Another man was dragging a fainting woman. A young girl ran ahead of them with white face and streaming hair. Ariston stumbled on after this company. A great black slave came swiftly around a corner and ran into him and knocked him over, but fled on without looking back. As the Greek boy fell forward, the rough little pebbles scoured his face. He lay there moaning. Then he began to forget his troubles. His aching body began to rest. He thought he would sleep. He saw Apollo smiling. Then Caius struggled and cried out. He pulled at the blanket and tried to free himself. This roused Ariston, and he sat up. He felt the hot pebbles again. He heard the mountain roar. He dragged himself to his feet and started on. Suddenly the street led him out into a broad space. Ariston looked around him. All about stretched wide porches with their columns. Temple roofs rose above them. Statues stood high on their pedestals. He was in the forum. The great open square was crowded with hurrying people. Under one of the porches Ariston saw the money changers locking their boxes. From a wide doorway ran several men. They were carrying great bundles of woolen cloth, richly embroidered and dyed with precious purple. Down the great steps of Jupiter's temple ran a priest. Under his arms he clutched two large platters of gold. Men were running across the forum dragging bags behind them.

Every one seemed trying to save his most precious things. And every one was hurrying to the gate at the far end. Then that was the way out! Ariston picked up his heavy feet and ran. Suddenly the earth swayed under him. He heard horrible thunder. He thought the mountain was falling upon him. He looked behind. He saw the columns of the porch tottering. A man was running out from one of the buildings. But as he ran, the walls crashed down. The gallery above fell cracking. He was buried. Ariston saw it all and cried out in horror. Then he prayed:

"O Lord Poseidon, shaker of the earth, save me! I am a Greek!"

Then he came out of the forum. A steep street sloped down to a gate. A river of people was pouring out there. The air was full of cries. The great noise of the crowd made itself heard even in the noise of the volcano. The streets were full of lost treasures. Men pushed and fell and were trodden upon. But at last Ariston passed through the gateway and was out of the city. He looked about.

"It is no better," he sobbed to himself.

The air was thicker now. The shower had changed to hot dust as fine as ashes. It blurred his eyes. It stopped his nostrils. It choked his lungs. He tore his chiton from top to bottom and wrapped it about his mouth and nose. He looked back at Caius and pulled the blanket over his head. Behind him a huge cloud was reaching out long black arms from the mountain to catch him. Ahead, the sun was only a red wafer in the shower of ashes. Around him people were running off to hide under rocks or trees or in the country houses. Some were running, running anywhere to get away. Out of one courtyard dashed a chariot. The driver was lashing his horses. He pushed them ahead through the crowd. He knocked people over, but he did not stop to see what harm he had done. Curses flew after him. He drove on down the road.

Ariston remembered when he himself had been dragged up here two years ago from the pirate ship.

"This leads to the sea," he thought. "I will go there. Perhaps I shall meet my master, Tetreius. He will come by ship. Surely I shall find him. The gods will send him to me. O blessed gods!"

But what a sea! It roared and tossed and boiled. While Ariston looked, a ship was picked up and crushed and swallowed. The sea poured up the steep shore for hundreds of feet. Then it rushed back and left its strange fish gasping on the dry land. Great rocks fell from the sky, and steam rose up as they splashed into the water. The sun was growing fainter. The black cloud was coming on. Soon it would be dark. And then what? Ariston lay down where the last huge wave had cooled the ground. "It is all over, Caius," he murmured. "I shall never see Athens again."

For a while there were no more earthquakes. The sea grew a little less wild. Then the half-fainting Ariston heard shouts. He lifted his head. A small boat had come ashore. The rowers had leaped out. They were dragging it up out of reach of the waves.

"How strange!" thought Ariston. "They are not running away. They must be brave. We are all cowards."

"Wait for me here!" cried a lordly voice to the rowers.

When he heard that voice Ariston struggled to his feet and called.

"Marcus Tetreius! Master!"

He saw the man turn and run toward him. Then the boy toppled over and lay face down in the ashes.

When he came to himself he felt a great shower of water in his face. The burden was gone from his back. He was lying in a row boat, and the boat was falling to the bottom of the sea. Then it was flung up to the skies. Tetreius was shouting orders. The rowers were streaming with sweat and sea water.

In some way or other they all got up on the waiting ship. It always seemed to Ariston as though a wave had thrown him there. Or had Poseidon carried him? At any rate, the great oars of the galley were flying. He could hear every rower groan as he pulled at his oar. The sails, too, were spread. The master himself stood at the helm. His face was one great frown. The boat was flung up and down like a ball. Then fell darkness blacker than night.

"Who can steer without sun or stars?" thought the boy.

Then he remembered the look on his master's face as he stood at the tiller. Such a look Ariston had painted on Herakles' face as he strangled the lion.

"He will get us out," thought the slave.

For an hour the swift ship fought with the waves. The oarsmen were rowing for their lives. The master's arm was strong, and his heart was not for a minute afraid. The wind was helping. At last they reached calm waters.

"Thanks be to the gods!" cried Tetreius. "We are out of that boiling pot."

At his words fire shot out of the mountain. It glowed red in the dusty air. It flung great red arms across the sky after the ship. Every man and spar and oar on the vessel seemed burning in its light. Then the fire died, and thick darkness swallowed everything. Ariston's heart seemed smothered in his breast. He heard the slaves on the rowers' benches scream with fear. Then he heard their leader crying to them. He heard a whip whiz through the air and strike on bare shoulders. Then there was a crash as though the mountain had clapped its hands. A thicker shower of ashes filled the air. But the rowers were at their oars again. The ship was flying.

So for two hours or more Tetreius and his men fought for safety. Then they came out into fresher air and calmer water. Tetreius left the rudder. "Let the men rest and thank the gods," he said to his overseer. "We have come up out of the grave."

When Ariston heard that, he remembered the Death he had left painted on his master's wall. By that time the picture was surely buried under stones and ashes. The boy covered his face with his ragged chiton and wept. He hardly knew what he was crying for—the slavery, the picture, the buried city, the fear of that horrid night, the sorrows of the people left back there, his father, his dear home in Athens. At last he fell asleep. The night was horrible with dreams—fire, earthquake, strangling ashes, cries, thunder, lightning. But his tired body held him asleep for several hours. Finally he awoke. He was lying on a soft mattress. A warm blanket covered him. Clean air filled his nostrils. The gentle light of dawn lay upon his eyes. A strange face bent over him.

"It is only weariness," a kind voice was saying. "He needs food and rest more than medicine."

Then Ariston saw Tetreius, also, bending over him. The slave leaped to his feet. He was ashamed to be caught asleep in his master's presence. He feared a frown for his laziness.

"My picture is finished, master," he cried, still half asleep.

"And so is your slavery," said Tetreius, and his eyes shone.

"It was not a slave who carried my son out of hell on his back. It was a hero." He turned around and called, "Come hither, my friends."

Three Roman gentlemen stepped up. They looked kindly upon Ariston.

"This is the lad who saved my son," said Tetreius. "I call you to witness that he is no longer a slave. Ariston, I send you from my hand a free man."

He struck his hand lightly on the Greek's shoulder, as all Roman masters did when they freed a slave. Ariston cried aloud with joy. He sank to his knees weeping. But Tetreius went on.

"This kind physician says that Caius will live. But he needs good air and good nursing. He must go to some one of Aesculapius' holy places. He shall sleep in the temple and sit in the shady porches, and walk in the sacred groves. The wise priests will give him medicines. The god will send healing dreams. Do you know of any such place, Ariston?"

The Greek thought of the temple and garden of Aesculapius on the sunny side of the Acropolis at home in Athens. But he could not speak. He gazed hungrily into Tetreius' eyes. The Roman smiled.

"Ariston, this ship is bound for Athens! All my life I have loved her—her statues, her poems, her great deeds. I have wished that my son might learn from her wise men. The volcano has buried my home, Ariston. But my wealth and my friends and my son are aboard this ship. What do you say, my friend? Will you be our guide in Athens?" Ariston leaped up from his knees. A fire of joy burned in his eyes. He stretched his hands to the sky.

"O blessed Herakles," he cried, "again thou hast conquered Death. Thou didst snatch us from the grave of Pompeii. Give health to this Roman boy. O fairest Athena, shed new beauty upon our violet crowned Athens. For there is coming to visit her the best of men, my master Tetreius."

So a living city was buried in a few hours. Wooded hills and green fields lay covered under great ash heaps. Ever since that terrible eruption Vesuvius has been restless. Sometimes she has been quiet for a hundred years or more and men have almost forgotten that she ever thundered and spouted and buried cities. But all at once she would move again. She would shoot steam and ashes into the sky. At night fire would leap out of her top. A few times she sent out dust and lava and destroyed houses and fields. A man who lived five hundred years after Pompeii was destroyed described Vesuvius as she was in his time. He said:

"This mountain is steep and thick with woods below. Above, it is very craggy and wild. At the top is a deep cave. It seems to reach the bottom of the mountain. If you peep in you can see fire. But this ordinarily keeps in and does not trouble the people. But sometimes the mountain bellows like an ox. Soon after it casts out huge masses of cinders. If these catch a man, he hath no way to save his life. If they fall upon houses, the roofs are crushed by the weight. If the wind blow stiff, the ashes rise out of sight and are carried to far countries. But this bellowing comes only every hundred years or thereabout. And the air around the mountain is pure. None is more healthy. Physicians send thither sick men to get well."

The ashes that had covered Pompeii changed to rich soil. Green vines and shrubs and trees sprang up and covered it, and flowers made it gay. Therefore people said to themselves:

"After all, she is a good old mountain. There will never be another eruption while we are alive."

So villages grew up around her feet. Farmers came and built little houses and planted crops and were happy working the fertile soil. They did not dream that they were living above a buried city, that the roots of their vines sucked water from an old Roman house, that buried statues lay gazing up toward them as they worked.

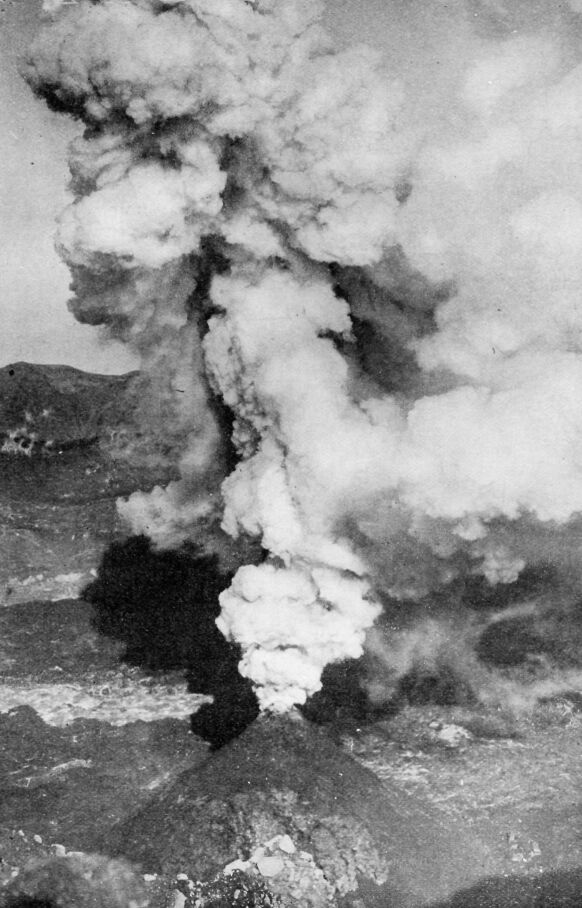

About three hundred years ago came another terrible eruption. Again there were earthquakes. Again the mountain bellowed. Again black clouds turned day into night. Lightning flashed from cloud to cloud. Tempests of hot rain fell. The sea rushed back and forth on the shore. The whole top of the mountain was blown out or sank into the melting pot. Seven rivers of red-hot lava poured down the slopes. They flowed for five miles and fell into the sea. On the way they set fire to forests and covered five little villages. Thousands of people were killed.

Since that time Vesuvius has been very active. Almost every year there have been eruptions with thunder and earthquakes and showers and lava. A few of these have done much damage. [Footnote: In this year, 1922, Vesuvius has been very active for the first time since 1906. It has been causing considerable alarm in Naples. A new cone, 230 feet high, has developed.—Ed.] And even on her calmest days a cloud has always hung above the mountain top. Sometimes it has been thin and white—a cloud of steam. Sometimes it has been black and curling—a cloud of dust.

Vesuvius is a dangerous thing, but very beautiful. It stands tall and pointed and graceful against a lovely sky. Its little cloud waves from it like a plume. At night the mountain is swallowed by the dark. But the red rivers down its slopes glare in the sky. It is beautiful and terrible like a tiger. Thousands of people have loved it. They have climbed it and looked down its crater. It is like looking into the heart of the earth. One of these travelers wrote of his visit in 1793. He said:

"For many days Vesuvius has been in action. I have watched it from Naples. It is wonderfully beautiful and always changing. On one day huge clouds poured out of the top. They hung in the sky far above, white as snow. Suddenly a cloud of smoke rushed out of another mouth. It was as black as ink. The black column rose tall and curling beside the snowy clouds. That was a picture in black and white. But at another time I saw one in bright colors.

"On a certain night there were towers and curls and waves and spires of flames leaping from the top of the mountain. Millions of red-hot stones were shot into the sky. They sailed upward for hundreds of feet, then curved and fell like skyrockets. I looked through my telescope and saw liquid lava boiling and bubbling over the crater's edge. I could see it splash upon the rocks and glide slowly down the sides of the cone. The whole top of the mountain was red with melted rock. And above it waved the changing flames of red, orange, yellow, blue.

"On another night, as I was getting into bed, I felt an earthquake. I looked out of my window toward Vesuvius. All the top was glowing with red-hot matter. A terrible roaring came from the mountain. In an instant fire shot high into the air. The red column curved and showered the whole cone. In half a minute came another earthquake shock. My doors and windows rattled. Things were shaken from my table to the floor. Then came the thunder of an explosion from the mountain and another shower of fire. After a few seconds there were noises like the trampling of horses' hoofs. It was, of course, the noise of the shot-out stones falling upon the rocks of the mountainsides eight miles away.

"I decided to ascend the volcano and see the crater from which all these interesting things came. A few friends went with me. For most of the way we traveled on horses. After two or three hours we reached the bottom of the cone of rocks and ashes. From there we had to go on foot. We went over to the river of red-hot lava. We planned to walk up along its edge. But the hot rock was smoking, and the wind blew the smoke into our faces. A thick mist of fine ashes from the crater almost suffocated us. Sulphur fumes blew toward us and choked us. I said,

"'We must cross the stream of lava. On the other side the wind will not trouble us.'

"'Cross that melted rock?' my friends cried out. 'We should sink into it and be burned alive.'

"But as we stood talking great stones were thrown out of the volcano. They rolled down the mountainside close to us. If they had struck us it would have been death. There was only one way to save ourselves. I covered my face with my hat and rushed across the stream of lava. The melted rock was so thick and heavy that I did not sink in. I only burned my boots and scorched my hands. My friends followed me. On that side we were safe. We climbed for half an hour. Then we came to the head of our red river. It did not flow over the edge of the crater. Many feet down from the top it had torn a hole through the cone. I shall never forget the sight as long as I live. There was a vast arch in the black rock. From this arch rushed a clear torrent of lava. It flowed smoothly like honey. It glowed with all the splendor of the sun. It looked thin like golden water.

"'I could stir it with a stick,' said one of my friends.

"'I doubt it,' I said. 'See how slowly it flows. It must be very thick and heavy.'

"To test it we threw pebbles into it. They did not sink, but floated on like corks. We rolled in heavier stones of seventy or eighty pounds. They only made shallow dents in the stream and floated down with the current. A great rock of three hundred pounds lay near. I raised it upon end and let it fall into the lava. Very slowly it sank and disappeared.

"As the stream flowed on it spread out wider over the mountain. Farther down the slope it grew darker and harder. It started from the arch like melted gold. Then it changed to orange, to bright red, to dark red, to brown, as it cooled. At the lower end it was black and hard and broken like cinders.

"We climbed a little higher above the arch. There was a kind of chimney in the rock. Smoke and stream were coming out of it. I went close. The fumes of sulphur choked me. I reached out and picked some lumps of pure sulphur from the edge of the rock. For one moment the smoke ceased. I held my breath and looked down the hole. I saw the glare of red-hot lava flowing beneath. The mountain was a pot, full of boiling rock."

Another man writes of a visit in 1868, a quieter year.

"At first we climbed gentle slopes through vineyards and fields and villages. Sometimes we came suddenly upon a black line in a green meadow. A few years before it had flowed down red-hot. Further up we reached large stretches of rock. Here wild vines and lupines were growing in patches where the lava had decayed into soil. Then came bare slopes with dark hollow and sharp ridges. We walked on old stiff lava-streams. Sometimes we had to plod through piles of coarse, porous cinders. Sometimes we climbed over tangled, lumpy beds of twisted, shiny rock. Sometimes we looked into dark arched tunnels. Red streams had once flowed out of them. A few times we passed near fresh cracks in the mountain. Here steam puffed out.

"At last we reached a broad, hot piece of ground. Here were smoking holes. The night before I had looked at them with a telescope from the foot of the mountain. I had seen red rivers flowing from them. Now they were empty. Last night's lava lay on the slope, cooled and black. I was standing on it. My feet grew hot. I had to keep moving. The air I breathed was warm and smelled like that of an iron foundry. I pushed my pole into a crack in the rock. The wood caught fire. I was standing on a thin crust. What was below? I broke out a piece of the hard lava. A red spot glared up at me. Under the crust red-hot lava was still flowing. I knew that it would be several years before it would be perfectly cool."

So for three centuries people have watched Vesuvius at work. But she is much older than that—thousands of years older—older than any city or country or people in the world. In all that time she has poured out millions of tons of matter—lava, huge glassy boulders, little pebbles of pumice stone, long shining hairs, fine dust or ashes. All these things are different forms of melted rock. Sometimes the steam blows the liquid into fine dust; sometimes it breaks it into little pieces and fills them with bubbles. At another time the steam is not so strong and only pushes the stuff out gently over the crater's edge. Many different minerals are found in these rocks—iron, copper, lead, mica, zinc, sulphur. Some pieces are beautiful in color—blue, green, red, yellow. Precious stones have sometimes been found—garnets, topaz, quartz, tourmaline, lapis lazuli. But most of the stone is dull black or brown or gray.

All this heavy matter drops close to the mountain. And on calm days the ashes, also, fall near at home. Indeed, the volcano has built up its own mountain. But a heavy wind often carries the fine dust for hundreds of miles. Once it was blown as far as Constantinople and it darkened the sun and frightened people there. Some of the ashes fall into the sea. For years the currents carry them about from shore to shore. At last they settle to the bottom and make clay or sand or mud. The material lies there for thousands of years and is hard packed into a soft fine grained rock, called tufa. The city of Naples to-day is built of such stone that once lay under the sea. An earthquake long ago lifted the ocean bottom and turned it into dry land. Now men live upon it and cut streets in it and grow crops on it.

So for many miles about, Vesuvius has been making earth. Her ashes lie hundreds of feet deep. Men dig wells and still find only material that has been thrown out of the volcano. When this matter grows old and lies under the sun and rain it turns to good soil. The acids of water and air and plants eat into it. Rain wears it away. Plant roots crack the rocks open. The top layer becomes powdered and rotted and mixed with vegetable loam and is fertile soil. So the country all around the volcano is a rich garden. Tomatoes, melons, grapes, olives, figs, cover the land.

But Vesuvius alone has not made all this ground. She is in a nest of volcanoes. They have all been at work like her, spouting ashes and pumice and rocks and lava. Ten miles away is a wide stretch of country where there are more than a dozen old craters. Twenty miles out in the blue bay a volcano stands up out of the water. A hundred miles south is a group of small volcanic islands. They have hot springs. One has a volcano that spouts every five or six minutes. At night it is like a lighthouse for sailors. One of these Islands is only two thousand years old. The men of Pompeii saw it pushed up out of the sea during an earthquake. A little farther south is Mt. Aetna in Sicily. It is a greater mountain than Vesuvius and has done more work than she has done. So all the southern part of Italy seems to be the home of volcanoes and earthquakes.

There are many other such places scattered over the world—Iceland, Mexico, South America, Japan, the Sandwich Islands. Here the same terrible play is going on—thunder, clouds, falling ashes, scalding rain, flowing lava. The earth is being turned inside out, and men are learning what she is made of.

Years came and went and changed the world. The old gods died, and the new religion of Christ grew strong. The old temples fell into ruins, and new churches were built in their places. Instead of the old Roman in his white toga came merchants in crimson velvet and knights in steel armor and gentlemen in ruffles and modern men in plain clothes.

Among all these changes, Pompeii was almost forgotten. But after a long while people began to be much interested in ancient Italy. They read old Roman books, and learned of her wonderful cities. They began to dig here and there and find beautiful statues and vases and jewels. They read the story of Pompeii in an old Roman book—a whole city suddenly buried just as her people had left her!

"There we should find treasures!" they said. "We should see houses, temples, shops, streets, as they were seventeen hundred years ago. We should find them full of statues and rich things. Perhaps we should find some of the people who lived in ancient days. But where to dig?"

Their question was answered by accident. At that time certain men were making a tunnel to carry spring water from the hills across the country to a little town near Naples. The tunnel happened to pass over buried Pompeii. They dug up some blocks of stone with Latin inscriptions carved on them. After that other people found little ancient relics near the same place.

"This must be where Pompeii lies buried," the wise men said.

They began to excavate. That was about two hundred years ago. Ever since that time the work has gone on. Sometimes people have been discouraged and have given up. At other times six hundred men have been working busily. Kings have given money. Emperors and princes and queens have visited the excavations. Artists have made pictures of the ruins, and scholars have written books about them. But it is a great task to uncover a whole city that is buried ten or twelve feet deep. The excavation is not yet finished. Perhaps when you are old men and women the work will be completed, and a whole Roman city will be open to your eyes.

But even as it is to-day, that ghost of a city is among the world's wonders. There is the thick stone wall that goes all about the town. On its wide top the soldiers used to stand to fight in ancient days. Now the stones are fallen; its towers are broken; its gates are open. Yet there the battered little giant stands at its task of protecting the town. Out of its eight gates stretch the paved streets.

Perhaps some day you will cross the ocean to visit this "dead city." It lies on a slope at the foot of Vesuvius. Behind stands the tall, graceful volcano with its floating feather of steam and smoke. In front lies a little plain, and beyond it a long ridge of steep mountains. Off at the side shines the dark blue sea with island peaks rising out of it. On hillsides and plain are green vineyards and dark forests dotted with white farmhouses.

In some places there are high mounds of dirt outside the city wall. They are made by the ashes that have been dug out by the excavators and piled here. If you climb one of them you will be able to look over the city. You will find it a little place—less than a mile long and half a mile wide inside its ragged wall. And yet many thousand people used to live here. So the houses had to be crowded together. You will see no grassy lawns nor vacant lots nor playgrounds nor parks with pleasant trees. Many narrow streets cross one another and cut the city into solid blocks of buildings. You will be confused because you will see thousands of broken walls standing up, but no roofs. They are gone—crushed by the piling ashes long ago.

At last you will come down and go in at one of the gates through the rough, thick wall, past the empty watch towers. You will tread the very paving stones that men's feet trampled nineteen hundred years ago as they fled from the volcano. You will climb a steep, narrow street. This is the street the fishermen and sailors used in olden times when they came in from the river or sea, carrying baskets of fish or leading mules loaded with goods from their ships. This is the street where people poured out to the sea on that terrible day of the eruption.

You will pass a ruined temple of Apollo with standing columns and lonely altar and steps that lead to a room that is gone. A little farther on you will come out into a large open paved space. It is the forum. This used to be the busiest place in all Pompeii. At certain hours of the day it was filled with little tables and with merchants calling out and with gentlemen and slaves buying good's. But now it is empty and very still. Around the sides a few beautiful columns are yet standing with carved marble at the top connecting them. But others lie broken, and most of them are gone entirely. This is all that is left of the porches where men used to walk and talk of business and war and politics and gossip.

At one end of the forum is a high stone platform and wide stone steps leading up to a row of broken columns in front of a fallen wall. This is the ruin of the temple of Jupiter, the great Roman god. Daily, men used to come here to pray before a statue in a dim room. Here, in the ruins, the excavators found the head of that statue—a beautiful marble thing with long curling hair and beard, and calm face. They found, too, a great broken body of marble. And in that large body a smaller statue was partly carved. This was a puzzling thing, but the excavators studied it out at last. They said:

"Old Roman books tell us that sixteen years before the great eruption there had been another earthquake. It had shaken down many buildings and had cracked many walls. But the people loved their city, and when the earthquake was over, they began to rebuild and to make their houses and temples better than ever. We have found many signs of that earthquake. We have found uncarved blocks of marble in the forum. Evidently masons were at work there when the eruption stopped them. We have found rebuilt walls in some of the houses. And here is the temple of Jupiter being used as a marble shop. Probably the early earthquake had shaken down and broken the statue of the god. A sculptor was set to work to carve a new one from the ruin. But suddenly the volcano burst forth, the artist dropped his chisel and mallet, and here we have found his unfinished work—a statue within a statue."

Behind the roofless porches of the forum are other ruined buildings—where the officers of the city did business, where the citizens met to vote, where tailors spread out their cloth and sold robes and cloaks. One large market building is particularly interesting. You will enter a courtyard with walls all around it and signs of lost porches. Broken partitions show where little stalls used to open upon the court. Other stalls opened upon the street. In some of these the excavators found, buried in the ashes and charred by the fire, figs, chestnuts, plums, grapes, glass dishes of fruit, loaves of bread, and little cakes. Were customers buying the night's dessert when Vesuvius frightened them away? In a cool corner of the building is a fish market with sloping marble counter. Near it in the middle of the courtyard are the bases of columns arranged in a circle around a deep basin in the floor. In the bottom of this basin the excavators found a thick layer of fish scales. Evidently the masters used to buy their fish from the market in the corner. Then the slaves carried them here to the shaded pool of water and cleaned them and scaled them and washed them. In another corner the excavators found skeletons of sheep. Here was a pen for live animals which a man might buy for his banquet or for a sacrifice to his gods. His slave would lead the sheep away through the crowds. But on that terrible day when the volcano belched, the poor bleating animals were deserted. Their pen held them and the ashes covered them and to-day we can see their skeletons.

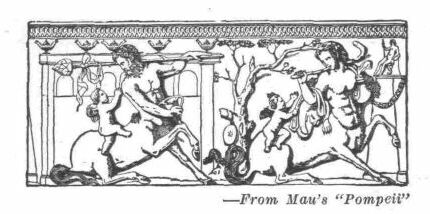

The walls around the market are still standing, though the top is broken and the roof is fallen. They are still covered with paintings. If you will look at them you can guess what used to be for sale here. There are game birds and fish and wine jars all pictured here in beautiful colors. There are cupids playing about a flour mill and cupids weaving garlands. There are also pictures of the gods and heroes and the deeds they did. Imagine this painted market full of chattering people, the little shops gay with piles of beautiful fruit and vegetables, the graceful columns and dark porches adding beauty. Imagine these people crying out and running and these columns swaying and falling when Vesuvius bellowed and shook the earth. And yet we can see the very fruits that men were buying and the pictures they were enjoying.

The forum with its markets and shops and offices and temples and statues was the very heart of the city. Many streets led into it. Perhaps you will walk down one of them, between broken walls, past open doorways. After several street corners you will come to a large building with high walls still standing and with tall, arched entrance. This also was one of the gay places in Pompeii, for it was a bathhouse. Every day all the ladies and gentlemen of the town came strolling toward it down the streets. The men went in at the wide doorway. The women turned and entered their own apartments around the corner. And as they walked toward the entrance they passed little shops built into the walls of the bathhouse. At every stall stood the shopkeeper, bowing, smiling, begging, calling. "Perfumes, sweet lady!"

"Rings, rings, beautiful madam, for your beautiful fingers!"

"Oil for your body, sir, after the bath!"

"A taste of sweets, madam, before you enter! Honey cakes of my own making!"

"Don't forget to buy my dressing for your hair before you go in! You'll get nothing like it in there."

So they chattered and called and coaxed. Some of the people bought, and some went laughing by and entered the bathhouse. As the gentlemen went in, a large court opened before them. Here were men bowling or jumping or running or punching the bag or playing ball or taking some other kind of exercise before the bath. Others were resting in the shade of the porches. A poet sat in a cool corner reading his verses to a few listeners. Some men, after their games, were scraping their sweating bodies with the strigil. Others were splashing in the marble swimming tank. Here and there barbers were working over handsome gentlemen—smoothing their faces, perfuming their hair, polishing their nails. There was talk and laughter everywhere. Men were lazily coming and going through a door that led into the baths. There were large rooms with high ceilings and painted walls. In one we can still see the round marble basin. The walls are painted with trees and birds and swimming fish and statues. It was like bathing in a beautiful garden to bathe here. Another room was for the hot bath, with double walls and hot air circulating between to make the whole room warm. The bathhouse was a great building full of comforts. No wonder that all the idle Pompeians came here to bathe, to play, to visit, to tell and hear the news. It was a gay and noisy place. We have a letter that one of those old Romans wrote to a friend. He says:

"I am living near a bath. Sounds are heard on all sides. The men of strong muscle exercise and swing the heavy lead weights. I hear their groans as they strain, and the whistling of their breath. I hear the massagist slapping a lazy fellow who is being rubbed with ointment. A ball player begins to play and counts his throws. Perhaps there is a sudden quarrel, or a thief is caught, or some one is singing in the bath. And the bathers plunge into the swimming tank with loud splashes. Above all the din you hear the calls of the hair puller and the sellers of cakes and sweetmeats and sausages."

After you leave the baths perhaps you will turn down Stabian Street. It has narrow sidewalks. The broken walls of houses fence it in closely on both sides and cast black shadows across it. It is paved with clean blocks of lava. You will see wheel ruts worn deep in the hard stone. Almost two thousand years old they are, made by the carts of the farmers, perhaps, who brought in vegetables for the market. At the street crossings you will see three or four big stone blocks standing up above the pavement. They are stepping-stones for rainy weather. Evidently floods used to pour down these sloping streets. You can imagine little Roman boys skipping across from block to block and trying to keep their sandals dry.

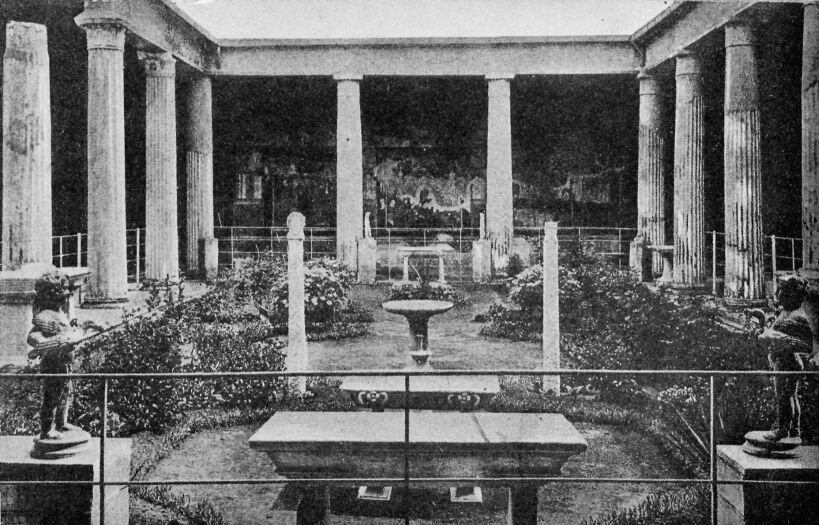

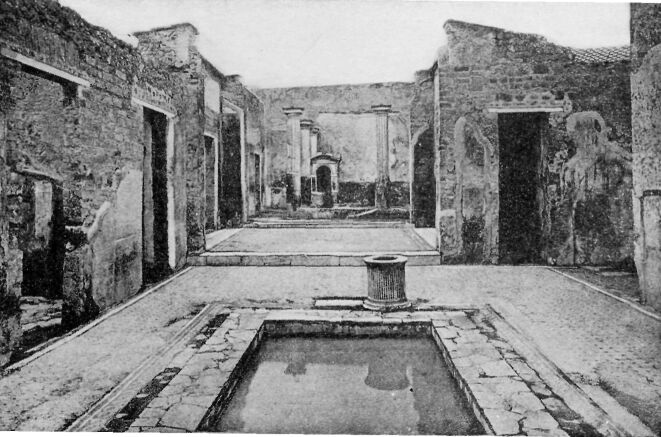

The street will lead you to the district of good houses where the wealthy men lived. Through open doorways you will get glimpses into the old ruined courtyards. It is hard guessing how the rooms used to look. But when you come to the door of the house of Vettius you will cry out with wonder. There is a lovely garden in the corner of the house. A long passage leads to it straight from the street. Around it runs a paved porch with pretty columns. Here you will walk in the shade and look out at the gay little garden, blooming in the sunshine. In every corner tiny streams of water spurt from little statues of bronze and marble and trickle into cool basins. Marble tables stand among the flowers. You will half expect a slave to bring out old drinking cups and wine bowls and set them here for his master's pleasure, or tablets and stylus for him to write his letters. Everything is in order and beautiful. It was not quite so when the excavators uncovered this house. The statues were thrown down. The flowers were scorched and dead under the piled-up ashes. But it was easy for the modern excavators to tell from the ground where the flower beds had been and where the gravel paths. Even the lead water pipe that carried the stream to the fountain needed little repairing. So the excavators set up the statues, cleaned the marble tables and benches, planted shrubs and flowers, repaired the porch roof, and we have a garden such as the old Romans loved and such as many houses in Pompeii had.

Several rooms look out upon this garden. One of them is perhaps the most interesting place in all Pompeii. You will walk into it and look around and laugh with delight. The whole wall is painted with pictures, big and little—pictures of columns and roofs, of plants and animals, of men and gods. They are all framed in with wide spaces of beautiful red. And tucked away between them in narrow bands of black are the gayest little scenes in the world. They are worth going all the way across the ocean to see. Psyches—delicate little winged girls like fairies—are picking slender flowers and putting them into tall, graceful baskets. They are so light and so tiny that they seem to be flitting along the wall like bright butterflies. In other panels plump little cupids—winged boys—are playing at being men. They are picking grapes and working a wine press and selling wine. It is big work for tiny creatures, and they must kick up their dimpled legs and puff out their chubby cheeks to do it. They are melting gold and carrying gold dishes and selling jewelry and swinging a blacksmith's hammer with their fat little arms. They are carrying roses to market on a ragged goat and weaving rose garlands and selling them to an elegant little lady. Everywhere these gay little creatures are skipping about at their play among the beautiful red spaces and large pictures. This was surely a charming dining room in the old days. The guests must have been merry every time their eyes lighted upon the bright wall. And if they looked out at the open side, there smiled the garden with its flowers and statues and splashing fountains and columns.

There lived in this house two men by the name of Vettius. We know this because the excavators found here two seals. In those days men fastened their letters and receipts and bills with wax. While the wax was soft they stamped their names in it with a metal seal. On the stamps that were found in this house were carved Aulus Vettius Restitutus and Aulus Vettius Conviva. Perhaps they were freedmen who once had been slaves of Aulus Vettius. But they must have earned a fortune for themselves, for there were two money chests in the house. And they must have had slaves of their own to take care of their twenty rooms and more. In the tiny kitchen the excavators found a good store of charcoal and the ashes of a little fire on top of the stone stove. And on its three little legs a bronze dish was sitting over the dead fire. A slave must have been cooking his master's dinner when the volcano frightened him away.

Vettius' dining room is empty of its wooden tables and couches. But some houses had stone ones built in their gardens for pleasant summer days. These the ashes did not crush, and they are still in place. Columns stood about the tables and vines climbed up them and across to make cool shade. The tables were always long and narrow and built around three sides of a rectangle. Low couches stand along the outside edges. Here guests used to lie propped up on their left elbows with pretty cushions to make them comfortable. In the open space in the middle of the square servants came and went and passed the dishes across the narrow tables. Children used to have little wooden stools and sit in this middle space opposite their elders. But in one old ruined garden dining room you will see a little stone bench for the children, built along the end of the table. It must have been pleasant to have supper there with the sunset coloring the sky, behind old Vesuvius, the cool breeze shaking the leaves of the garden shrubs, and the fountain tinkling, and a bird chirping in a corner, and the shadows beginning to creep under the long porches, and the tiny flames of lamps fluttering in the dusky rooms behind.

After you leave the house of Vettius and walk down the street, you will come to a certain door. In the sidewalk before it you will see "Have" spelled with bits of colored marble. It is the old Latin word for "Welcome." It is too pleasant an invitation to refuse. Go in through the high doorway and down the narrow passage to the atrium. Every Roman house had this atrium. It is like a large reception hall with many rooms opening off it—bedrooms, dining rooms, sitting rooms. Beautiful hangings instead of doors used to shut these rooms in. The atrium had an opening in the roof where the sun shone in and softly lighted the big room. Here the master used to receive his guests. In the house of Vettius the two money chests were found in the atrium. In this same room in the house of "Welcome," there was found on the floor a little bronze statue, a dancing faun, one of the gay friends of Dionysus. It is a tiny thing only two feet high, but so pretty that the excavators named the house after it—The House of the Faun. Evidently the old owner loved beautiful things and had money to buy them. Even the floors of some of his rooms are made in mosaic pictures. There are doves at play, and ducks and fish and shells all laid under your feet in bright bits of colored marble. And beyond the pleasant court with its porches and garden is a large sitting room. In the floor of this the excavators found the most wonderful mosaic picture of all, a picture of a battle, with waving spears and prancing horses and fallen men. Two kings are facing each other to fight—Darius, king of Persia, standing in his chariot, and Alexander, king of Greece, riding his war horse. The bits of stone are so small and of such perfect color that the mosaic looks like a beautiful painting. Imagine how the excavators' hearts leaped when the spades took the gray ashes off this bright picture. It was too precious a thing to leave here in the rain and wind. So the excavators carefully took it up and put it into the museum of Naples where there are other valuable things from Pompeii.

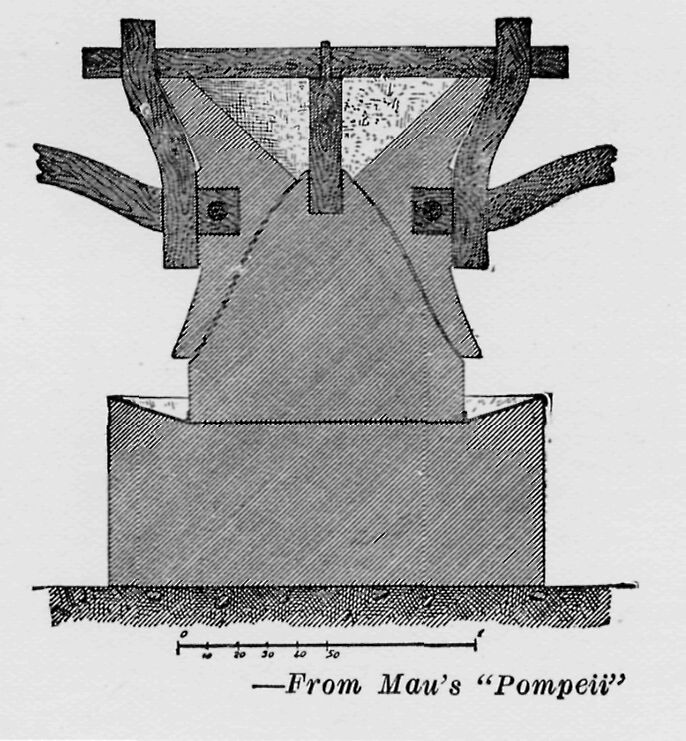

There are many other houses almost as pleasant and beautiful as this House of the Faun. Every one has its atrium and its sunny court and its fountains and statues and its painted walls. But Pompeii was a city of business, too, and had many workshops. There is a dye shop where the excavators found large lead pots and glass bottles still full of dye. There are cleaners' shops where the slaves used to take their masters' robes to be cleaned. Here the excavators found vats and white clay for cleaning, and pictures on the wall showing men at work. There are tanneries where leather was made. The rusted tools were found which the men had thrown down so long ago. There is a pottery shop with two ovens for baking the vases. On a certain street corner you will see an old wine shop. It is a little room cut into the corner wall of a great house. Its two sides are open upon the street with broad marble counters. Below the counters are big, deep jars. Their open tops thrust themselves through the slab. You can look into their mouths where the shopkeeper used to dip out the wine. On the walls of the room are marks that show where shelves hung in ancient days to hold cups and glasses. In the outer edge of the sidewalk before the shop are two round holes cut into the stone. Long ago poles were thrust into them to hold an awning that shaded the walk in front of the counters. We can imagine men stopping in this pleasant shade as they passed. The busy slave inside the shop whips out a cup and a graceful, long-handled ladle and dips out the sweet-smelling wine from the wide-mouthed jar. And we can imagine how the cups fell clattering from the men's hands when Vesuvius thundered. In one shop, indeed, the excavators found an overturned cup on the counter and a wine stain on the marble. But the most interesting shops are the bakeries. There were twenty of them in Pompeii. You will see the ovens in the courtyard. They are big beehives built of stone or brick. The baker made a fire inside and let the walls become hot. Then he raked out the coals and cleaned the floor and put in his bread. The hot walls baked the loaves. In one oven the excavators found a burned loaf eighteen hundred years old. When the earthquake shook his house, did the baker snatch out the rest of the ovenful to feed his hungry family as they groped about for safety in the terrible darkness? In several bakeries you will see, also, the mills. They are great mortar-shaped things standing taller than a man. The heavy stone above turned around upon the stone below. A man poured wheat in at the top. It fell down and was ground between the two stones and dropped out at the bottom as flour. A horse or donkey was hitched to the mill to turn it. Around and around he walked all day. He was blindfolded to prevent his becoming dizzy. You will see on the stone floor in one bakery the path that was made by years of this walking. In the old days this silent empty court must have been an interesting place. The donkey's hoofs beat lazy time on the stone floor. Now and then a slave lifted up a bag of wheat and poured it into the mill or scooped out the white flour from the trough at the bottom. Another man sifted the flour and the breeze blew the white dust over his bare arms. Some of the ovens were smoking and glowing with fresh fire. Others were shut, with the browning bread inside, and a good smell hung in the air. And out in front was a little shop where the master sold the thin loaves and the fancy little cakes.

In the hundreds of houses and shops of this little town the excavators have found bronze tables and lamps and lamp stands and wine jars and kitchen pots and pans and spoons and glass vases and silver cups and gold hairpins and jewelry and ivory combs and bronze strigils and mirrors and several statues of bronze and marble. But where they had hoped to find thousands of precious things they have found only hundreds. Many pedestals are empty of their statues. Here and there the very paintings have been cut from the walls. Those are the pictures we should most like to see. How beautiful could they have been?

"Evidently men came back soon after the eruption," say the excavators. "The tops of their ruined houses must have stood up above the ashes. They dug down and rescued their most precious things. We have even found broken places in walls where we think men dug tunnels from one house to another. That is why the temple and market place have so few statues. That is why we find so little jewelry and money and dishes. But we have enough. The city is our treasure."

One rich find they did make, however. There was a pleasant farmhouse out of town on the slope of Vesuvius. Evidently the man who owned it had a vineyard and an olive grove and grain fields. For there are olive presses and wine presses and a great court full of vats for making wine and a floor for threshing wheat and a mill for grinding flour and a stable and a wide courtyard that must have held many carts. And there are bathrooms and many pleasant rooms besides. In the room with the wine presses was a stone cistern for storing the fresh grape juice. Here the excavators found a treasure and a mystery. In this cistern lay the skeleton of a man. With him were a thousand pieces of gold money, some gold jewelry, and a wonderful dinner set of silver dishes. There are a hundred and three pieces—plates, platters, cups, bowls. And every one has beaten up from it beautiful designs of flowers and people. An artist must have made them, and a rich man must have bought them. How did they come here in this farmhouse? They must have been meant for a nobleman's table. Had some thief stolen them and hidden here, only to be caught by the volcano? Did some rich lady of the city have this farm for her country place? And had she sent her treasure here to escape when the volcano burst forth? At any rate here it lay for eighteen hundred years. And now it is in a museum in Paris, far from its old owner's home.

In this buried city we find the houses in which men lived, the pictures they loved, the food they ate, the jewels they wore, the cups they drank from. But what of the people themselves? Were they real men and women? How did they look? Did they all escape? Not all, for many skeletons have been found here and there through the city—in the market place, in the streets, in the houses. And sometimes the excavators have found still stranger, sadder things. Often as a man has been digging in the hard-packed ashes, his spade has struck into a hole. Then he has called the chief excavator.

"Let us see what it is," the excavator has said, "Perhaps it will be something interesting."

So they have mixed plaster and poured it into the hole. They have given it a little time to harden and then have dug away the ashes from around it. In that way they have made a plaster cast just the shape of the hole. And several times when they have uncovered their cast they have found it to be the form of a man or woman or child. Perhaps the person had been hurrying through the street and had stumbled and fallen. The gases had choked him, the ashes had slowly covered him. Under the moistening rain and the pressure of all the hundreds of years the ashes had hardened almost to stone. Meantime the body had decayed and had sunk down into a handful of dust. But the hardened ashes still stood firm around the space where the body had been. When this hole was filled with plaster, the cast took just the form of the one who had been buried there so long ago—the folds of his clothes, the ring on his finger, the girl's knot of hair, the negro slave's woolly head. So we can really look upon the faces of some of the ancient people of Pompeii. And in another way we can learn the names of many of them.

One of the streets that leads out from the wall is called the "Street of Tombs." It is the ancient burying ground. You will walk along the paved street between rows of monuments. Some will be like great square altars of marble beautifully carved. Some will be tall platforms with steps leading up. There will be marble benches where you may sit and think of the old Pompeians who were twice buried in their beautiful tombs. And there on the marble monument you will see their names carved in old Latin letters, and kind things that their friends said about them. There are:

Marcus Cerrinius Restitutus; Aulus Veius, who was several times an officer of the city; Mamia, a priestess; Marcus Porcius; Numerius Istacidius and his wife and daughter and others of his family, all in a great tomb standing on a high platform; Titus Terentius Felix, whose wife, Fabia Sabina, built his tomb; Tyche, a slave; Aulus Umbricius Scaurus, whose statue was set up in the market place to do him honor; Gaius Calventius Quietus, who was given a seat of honor at the theater on account of his generosity; Nævoleia Tyche, who had once been a slave, but who had been freed, had married, and grown wealthy and had slaves of her own; Gnæus Vibius Saturninus, whose freedman built his tomb; Marcus Arrius Diomedes, a freedman; Numerius Velasius Gratus, twelve years old; Salvinus, six years old; and many another.

After seeing the tombs and houses and shops you will leave that little city, I think, feeling that the people of ancient times were much like us, that men and mountains have done wonderful things in this old world, that it is good to know how people of other times lived and worked and died.

This statue, now in the Metropolitan Museum, was found at Pompeii. Probably Caius was dressed just like this, and carried such a stick when he played in his father's courtyard.

Nowadays men know from history what may happen when Vesuvius wakes. But in 79 A.D., when Pompeii was buried, the mountain had slept for hundreds of years, and no man knew that an eruption might bury a city.

The roofs are all gone and all the partitions inside the houses show. That is why it all looks so crowded and confused. But if you study it carefully you can see some interesting things. The big open space is the forum. It is about five hundred feet long, running northeast and southwest. South of it is the temple of Apollo. North of it, where you see the bases of columns in a circle, was the market. Next to the market is the place where the gods of the city were worshipped. The broad street beside the forum running southeast is the one down which Ariston fled. Then he turned into the forum, ran out the gate near the lower end into the steep street that runs southwest and ends at a city gate near the sea. NOLA STREET AND THE TEMPLE OF FORTUNE.

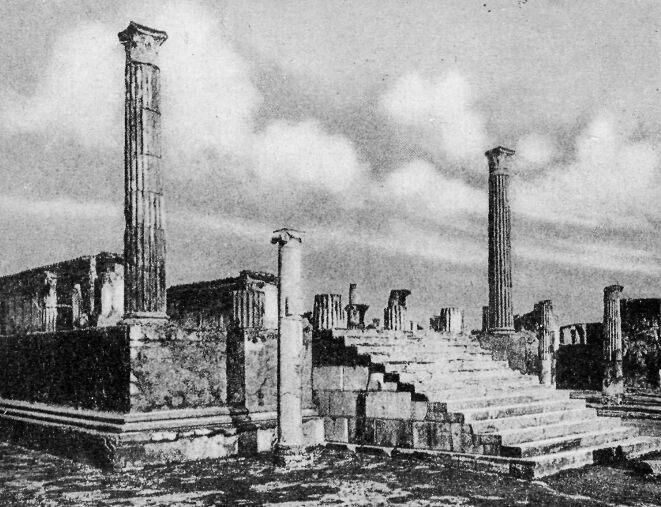

You must imagine this temple with an altar in front, a broad flight of steps, and a portico of beautiful columns. You can see the street paved with blocks of lava, the deep wheel ruts, and the stepping stones for rainy weather.

Pompeii was surrounded by two high walls fifteen feet apart, with earth

between. An embankment of earth was piled up inside also. This is one of

the eight gates in the wall.

On the tomb of Nævoleia Tyche was a carving of a ship gliding into port, the sailors furling the sails. Within this tomb is a chamber where funeral urns stand, containing the ashes of Tyche and her husband, and of the slaves they had freed. Pompeians always burned the bodies of the dead.

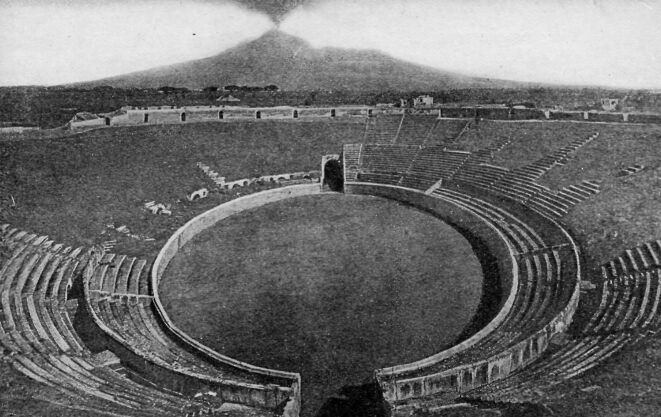

Like other Roman towns, Pompeii had an amphitheater. Here twenty thousand people could come and watch the gladiators fight in pairs till one was killed. Then the dead body was dragged off, and another pair appeared and fought. Sometimes the gladiators were prisoners captured in war, like the famous Spartacus; sometimes they were slaves; sometimes criminals condemned to death. Sometimes a man was pitted against a wild beast; sometimes two wild beasts fought each other. The amphitheater had no roof. Vesuvius, with its column of smoke, was in plain view from the seats. There was a great awning to protect the spectators. The lower seats were for officials and distinguished people; for the middle rows there was an admission fee; all the upper seats were free.

A few large houses had baths of their own, but most people went every

day to a great public bath which was a very gay place. This open court

which you see, was for games.

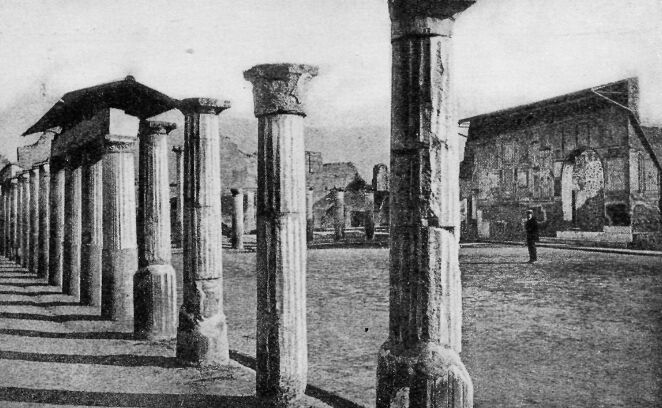

The temple was built on a high foundation. A broad flight of steps led up to it, with an altar at the foot. There was a porch all round it held up by a row of columns. Some of the columns have stood up through all the earthquakes and eruptions of two thousand years. Inside the porch was a small room for the statue of Apollo. In the paved court around this temple were many altars and statues of the gods. This was at one time the most important temple in Pompeii.

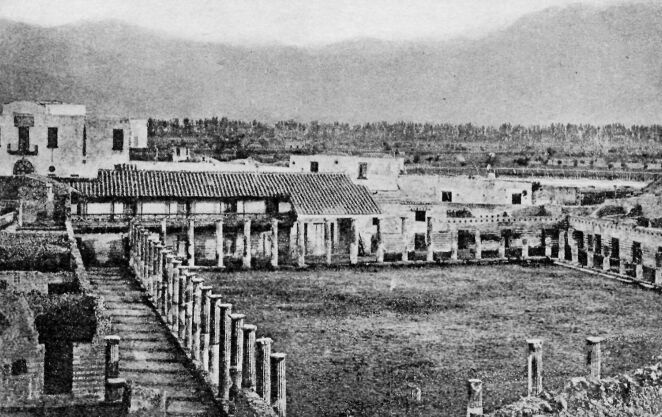

In this large open court the gladiators had their training and practice.

In small cells around the court they lived. They were kept under close

guard, for they were dangerous men. Sixty-three skeletons were found

here, many of them in irons.

Pompeii had two theaters for plays and music, besides the amphitheater

where the gladiators fought. The smaller theater, unlike the others, had

a roof. It seated fifteen hundred people. We think perhaps contests in

music were held here.

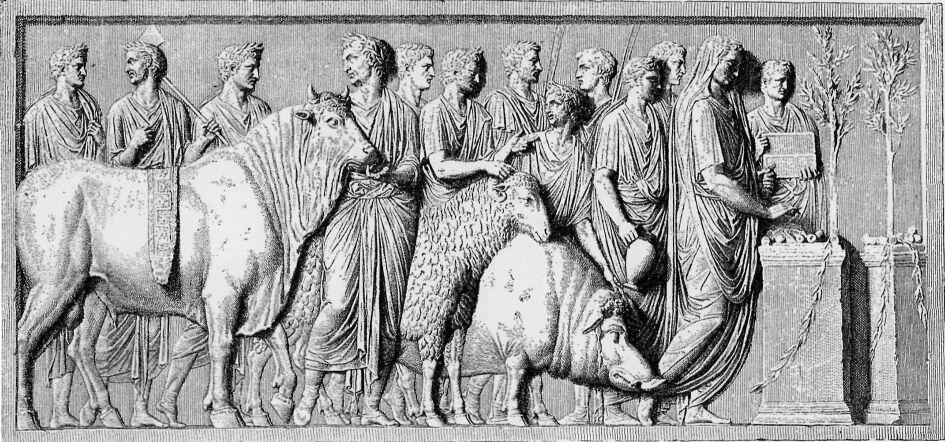

A boar, a ram, and a bull are to be killed, and a part of the flesh is

to be burned on the altar to please the gods.

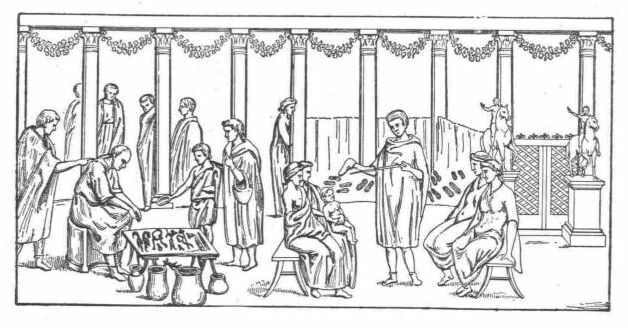

On the walls of a room in a house in Pompeii men found this picture, showing how interesting the life of the forum was. At the left is a table where a man has kitchen utensils for sale. But he is dreaming and does not see a customer coming. So his friend is waking him up. Near him is a shoemaker selling sandals to some women.

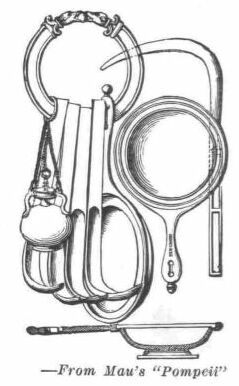

Underneath are two ivory toilet boxes. One was probably for perfumed oil.

These were found hanging in a ring in one of the great public baths. You

see a flask for oil, a saucer to pour the oil into, and four scrapers to

scrape off the oil and dirt before a plunge.

With the columns and tables and statues that were found, this court has been built on the site of an old ruined villa. Flowers bloom and the fountain plays in it to-day just as they did over two thousand years ago. There are wall paintings in the shadows at the back. The little boys holding the ducks must look very much like Caius when he was a little boy. When he went to the farm in the hills for a hot summer, he had ducks to play with; here are statues to remind him, in the winter time, of what fun that was.

A garden like this, not generally so large, was laid out inside every important house in Pompeii. The family rooms surrounded it. These rooms received most of their light and air from this garden. Caius was lying on a couch in a garden like this, when the shower of pebbles suddenly began. Ariston was painting the walls of a room that overlooked the garden.

This is part of a beautiful wall painting in a Pompeian house, the sort of painting that Ariston was making when the volcano burst forth. See how much the little boy looks like his mother, and what beautiful bands they both have in their hair. Chairs like this one have been found in the ruins, and the same design is on many other pieces of furniture.

The Metropolitan Museum owns the complete wall paintings for a Pompeian

room. They are put up just as they were in Pompeii. There is even an

iron window grating. A beautiful table from Pompeii stands in the

center. The room is one of the gayest in the whole museum, with its rich

reds and bright yellows, greens, and blues.

In this house the cook must have been in the kitchen, just ready to go

to work when he had to flee. He left the pot on a tripod on a bed of

coals, ready for use. You can see an arched opening underneath the

fireplace. This was where the cook kept his fuel. The small size of

the kitchens shows that the Pompeians were not great gluttons.

These kettles and frying pans and ladles are made of bronze, an alloy of copper and tin. They look very much like our kitchen furnishings.

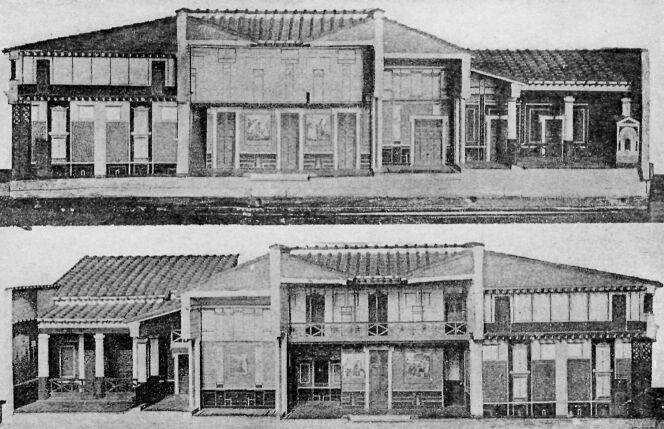

Some rich Pompeian had a pair of beautiful silver cups with graceful handles. The design was made in hammered silver, and showed centaurs talking to cupids that are sitting on their backs. A centaur was half man, half horse.

From the ruins and from ancient books, men know almost all the rooms of a Pompeian house. So they have pictured this one as it was before the disaster, with its many beautiful wall paintings, its mosaic floors, its tiled roofs. If you can imagine these two halves fitted together, and yourself inside, you can visit one of the most attractive houses in Pompeii. Do you see how the tiled roof slants downward from four sides to a rectangular opening in the highest part of the house? Below this opening was a shallow basin into which the rainwater fell. This basin was in the center of the atrium, the most important room in the house. The walls of this room were painted with scenes from the Trojan war. This is the house which has the mosaic picture of a dog on the floor of the long entrance hall (see next page). On each side of the hall, facing the street, are large rooms for shops, where, doubtless, the owner conducted his business. He was not a "Tragic Poet." Some people think he was a goldsmith. On each side of the atrium were sleeping rooms. Can you see that the doors are very high with a grating at the top to let in light and air? Windows were few and small, and generally the rooms took light and air from the inside courts rather than from outside. Back of the atrium was a large reception room with bedrooms on each side. And back of this was a large open court, or garden, with a colonnade on three sides and a solid wall at the back. Opening on this garden was a large dining room with beautiful wall paintings, a tiny kitchen, and some sleeping rooms. This house had stairways and second story rooms over the shops. This seems to us a very comfortable homelike house.

Here you see the shallow basin in the floor of the atrium. This basin

had two outlets. You can see the round cistern mouth near the pool.

There was also an outlet to the street to carry off the overflow. At the

back of the garden you can see a shrine to the household gods. At every

meal a portion was set aside in little dishes for the gods.

From the vestibule of the House of the Tragic Poet. It says loudly,

"Beware the dog!" Pictures and patterns made of little pieces of

polished stone like this are called mosaic. Sometimes American

vestibules are tiled in a simple mosaic. Wouldn't it be fun if they had

such exciting pictures as this? A real dog, or two or three, probably

was standing inside the door, chained, or held by slaves.

There was a wine cellar under the colonnade. Here were twenty skeletons; two, children. Near the door were found skeletons of two men. One had a large key, doubtless the key of this door. He wore a gold ring and was carrying a good deal of money. He was probably the master of the house. Evidently the family thought at first that the wine cellar would be a safe place, but when they found that it was not so, the master took one slave and started out to find a way to escape. But they all perished.

If one of the mills that were found in the bakery were sawed in two, it would look like this. You can see where the baker's man poured in the wheat, and where the flour dropped down, and the heavy timbers fastened to the upper millstone to turn it by.

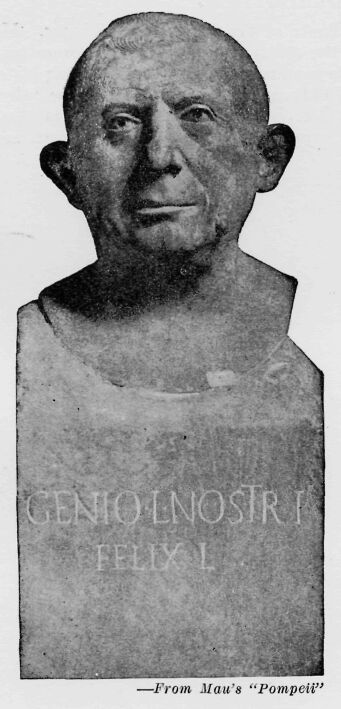

This Lucius was an auctioneer who had set free one of his slaves, Felix. Felix, in gratitude, had this portrait of his master cast in bronze. It stood on a marble pillar in the atrium of the house.

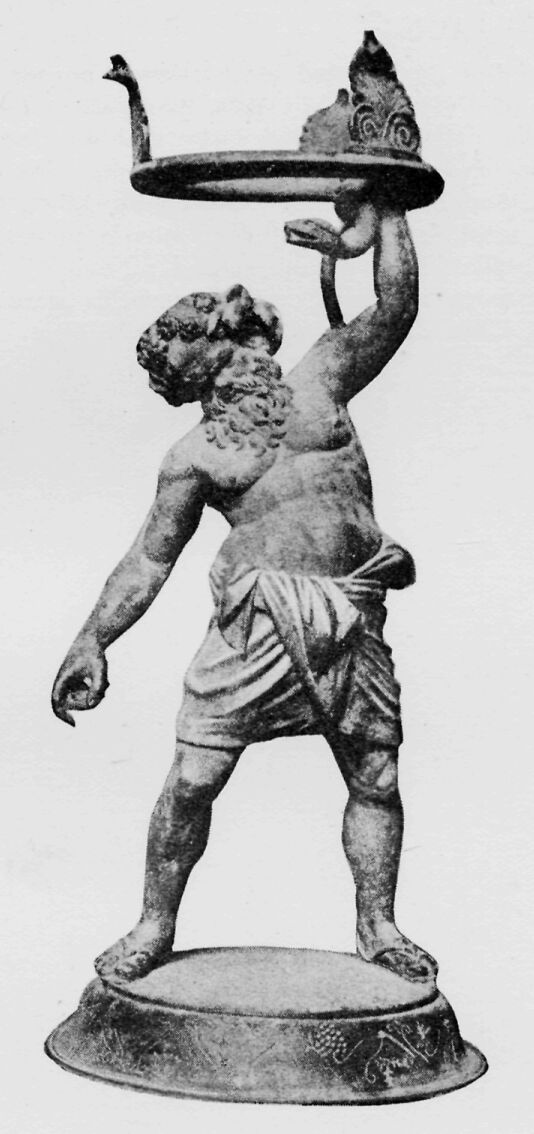

It is the figure of the Roman God Silenus. He was the son of Pan, and the oldest of the satyrs, who were supposed to be half goat. Can you find the goat's horns among his curls? He was a rollicking old satyr, very fond of wine, always getting into mischief. The grape design at the base of the little statue, and the snake supporting the candleholder, both are symbols of the sileni.

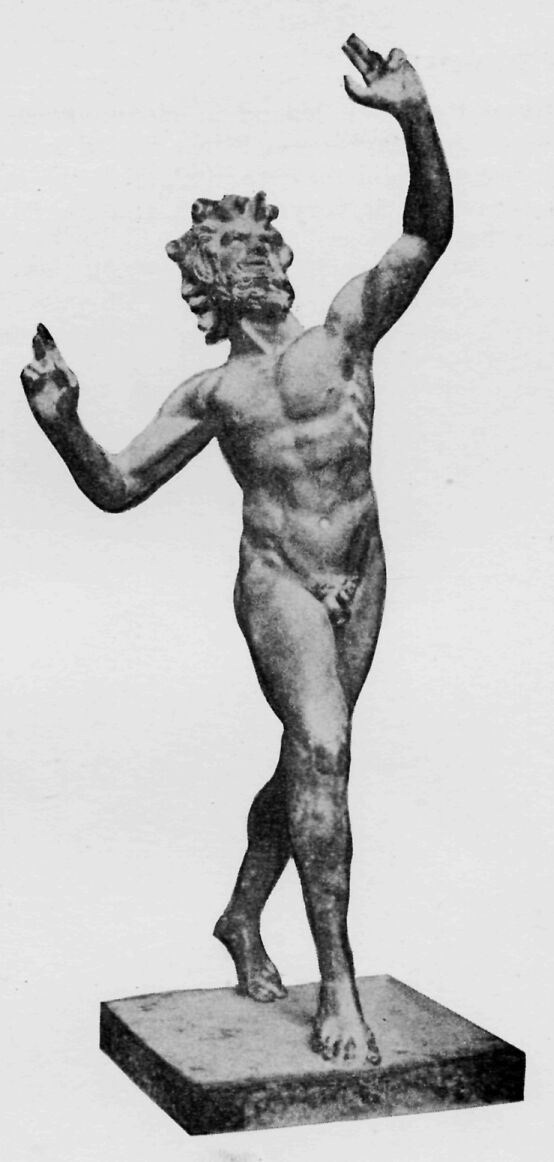

In one of the largest and most elegant houses in Pompeii, on the floor of the atrium, or principal room of the house, men found in the ashes this bronze statue of a dancing faun. Doesn't he look as if he loved to dance, snapping his fingers to keep time? Although this great house contained on the floor of one room the most famous of ancient mosaic pictures, representing Alexander the Great in battle, and although it contains many other fine mosaics, it was named from this statue, the House of the Faun, Casa del Fauno.

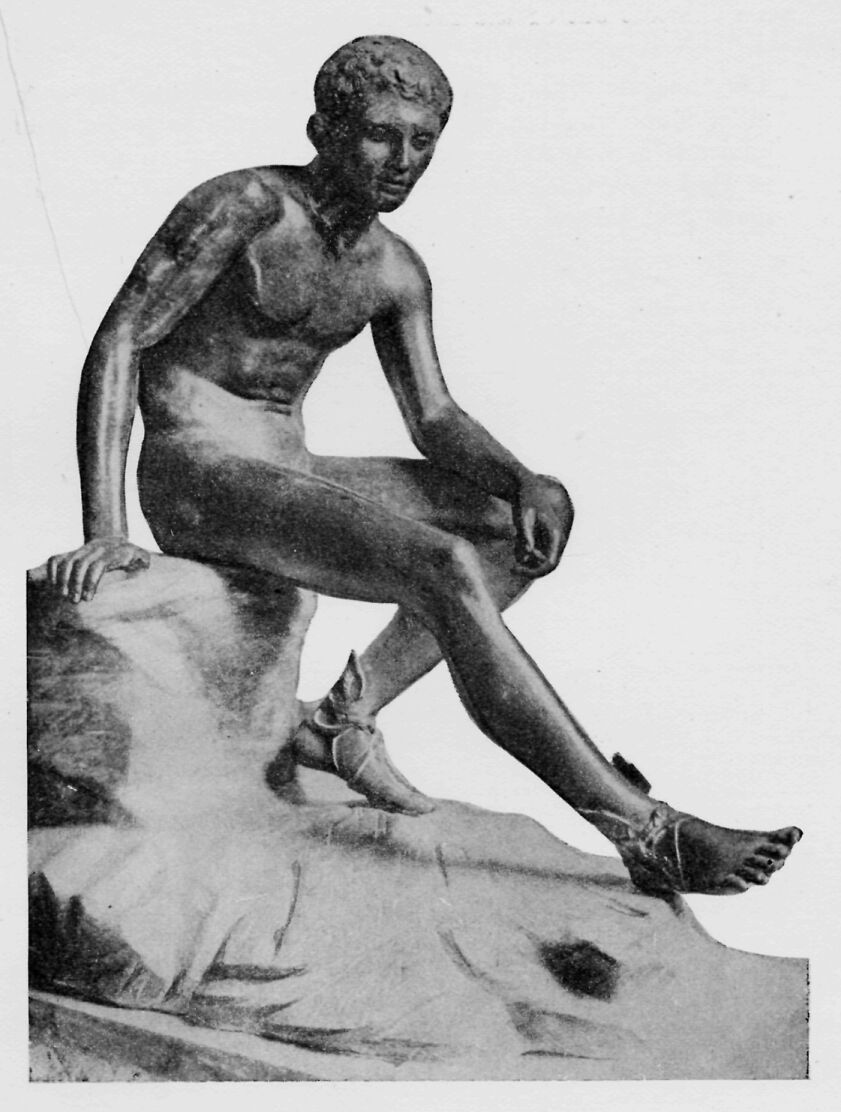

This bronze statue was found in Herculaneum, the city on the other slope of Vesuvius which was buried in liquid mud. This mud has become solid rock, from sixty to one hundred feet deep so that excavation is very difficult, and the city is still for the most part buried.

The visitors to-day are walking where Caius walked so long ago on the same paving stones. The three stones were set up to keep chariots out of the forum.

| Next Part | Main Index |