[Pg 1]

| GRATIS WITH] | [SOMETHING TO READ. |

| No. 675.] |

CONTAINS A COMPLETE STORY AND PRESENTED GRATIS EVERY WEEK

WITH THE JOURNAL “SOMETHING TO READ.” EDITED BY EDWIN J. BRETT. | [Vol. XXVII. |

By G. P. S.

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

“My dear Miss Standen,—Now that the arch-enemy of mankind (in reality he is often a friend) has deprived you of your—shall I say foster mother? it is time for me to say that I hope you will always regard me as a friend, who has known you from your earliest childhood. There are some events in your family history which a promise to the dead kept me from relating during Mrs. O’Hara’s lifetime. I will acquaint you with them fully in a few days. As a preliminary, Mrs. Gascoigne and myself will be delighted to have you with us while you decide about the future. The sooner the better. Shall we say to-day at your own time? A house of mourning is not a suitable place for a young girl who—although she may have experienced much kindness—is no way connected with the deceased. Forgive an old lawyer’s bluntness; you are too sensible, I am sure, to take offence at my home-truths (which are always disagreeable). Awaiting you and your luggage,

“Believe me, my dear Miss Standen,

“Your sincere friend,

“Henry Morton Gascoigne.”

It was impossible not to believe in the sincerity of the letter, and Muriel Standen read it a second time with a keen sense of gratitude for the writer.

She had believed herself entirely alone in the world, penniless, and without a home.

For, after the death of Mrs. O’Hara, she could no longer stay at the farm.

Tom was to be married in a few weeks at his mother’s last request, and although she had mentioned Muriel’s name, apparently with the intention of adding something regarding her, death had intervened.

Mrs. O’Hara died before the girl could ascertain any particulars of her early life.

She answered Mr. Gascoigne’s letter, thankfully accepting his kind offer, and sent it by one of the farm-hands.

Then she packed her two small trunks and said good-bye to sturdy Tom O’Hara, who said the farm would miss her sadly.

“But it is not the place for a lady like you, Miss Standen. My mother was next door to being one, as you know, and even she detested farm life. It was better for you when she was here. Now you will go among your own people, I hope. I wish I could tell you who they are, but my mother kept her knowledge—if she had any—to herself.”

“Thank you,” she said, sadly. “I do not know where I am going when I leave Mr. and Mrs. Gascoigne. I expect that I am quite alone in the world, otherwise my people could hardly have left me without any sign all these years.”

“If it comes to that, Miss Standen,” and[Pg 2] the big fellow strode hastily across the room to her, “the farm’s a home to you whenever you like to make use of it. Maggie’s a good girl, and she would feel honoured by your staying here.”

“I thank you Tom most warmly,” giving him both her hands. “You are a kind hearted man, and I shall never forget your generosity. But I intend to go to London to make my living there.

“I have made some enquiries, and my voice ought to do something for me. Mr. Gascoigne will always have my address, and he will give me news of you now and then. Good-bye, I must not keep your horse waiting any longer.”

“I am going to drive you myself, Miss Standen, if you will allow me. It will be the last time.”

“Well, well, my dear, there is no immediate hurry. You have scarcely been with us two days. As a matter of fact, Mrs. Gascoigne and myself would be only too glad if you could make up your mind to remain with us altogether, but I suppose you are tired of the country.”

“You beggar me of gratitude,” she said, flushing. “I have not the slightest claim upon you and you treat me like a daughter—almost.”

“I wish you were now that my own are so far away. Well, if you are determined to hear I must tell you, sit down in that arm-chair comfortably, and remember that a lawyer does not like to be interrupted. At the same time my dear, prepare yourself to hear some sad news.

“Twenty years ago, your mother came to Abbott Mansfield with you, a little child just able to walk without falling.

“She rented the cottage, known as the Laurels, which was then let furnished, and lived there for four years with a nurse for you and one other maid servant.

“She dressed always in widow’s weeds, made no acquaintances whatever, and refused to see any people who from kindness or curiosity called upon her.

“One day I received a note asking me to go to the Laurels.

“I went, and found your mother dying.

“The doctor said it was general weakness, want of vitality and nervous power, and had advised her to go to a warm climate some weeks before.

“She told me it was a broken heart, my dear.”

Muriel had grown white and her eyes were dark with suppressed tears.

“You will find me brutally matter-of-fact. Do not think me devoid of sympathy. Cry as much as you like. Shall I go on?” after a few moments pause.

“Yes, please.”

“Mrs. Standen’s story was a sad one, but unfortunately, no new thing. She had married when very young, and, being a lovely attractive woman, as I saw by the miniature which is in your possession, had no lack of attention from her husband’s friends.

“He was a major in the —th Hussars, a good officer and beloved by all who knew him. Unfortunately he trusted too much, and he trusted Captain Ainslie absolutely.

“The two were the closest of friends, and even the marriage of Major Winstanley had not weakened their friendship.

“Your father was a very striking-looking man, Miss Winstanley, I will show you a portrait of him when I have finished, a thoroughbred gentleman, nobility and integrity stamped on every feature; but the captain was handsome in the style admired by ladies—fair, with blue eyes, a long moustache, and, no doubt, golden hair.

“Your father was passionately attached to your mother, and up to the time of your birth they were very happy.

“He had a strong, stern nature, however, and in addition to his duties, which, of course, absorbed a good part of each day, he was fond of literary pursuits.

“A man does not care the less for his wife, Miss Winstanley, because he does not keep up his honeymoon all his married life. Your mother did not say that she was neglected; but Captain Ainslie got into the habit of going to see her every day, when, nine times out of ten, she was alone.

“He was the type of man who is found in ladies’ drawing-rooms at tea-times. Sometimes he took her out for drives or rides, the major trusted him entirely.

“When you were about a year old, Major Winstanley was summoned to the death-bed of his father; as the journey to the North was long and fatiguing, he did not take his wife, for she was not strong and from the time of your birth had always been delicate. Four days later, when Major Winstanley returned—”

The old lawyer stopped, the look on the girl’s face was so piteous to see.

Her large grey eyes were wide and dark, the sweet mouth was quivering with feeling.

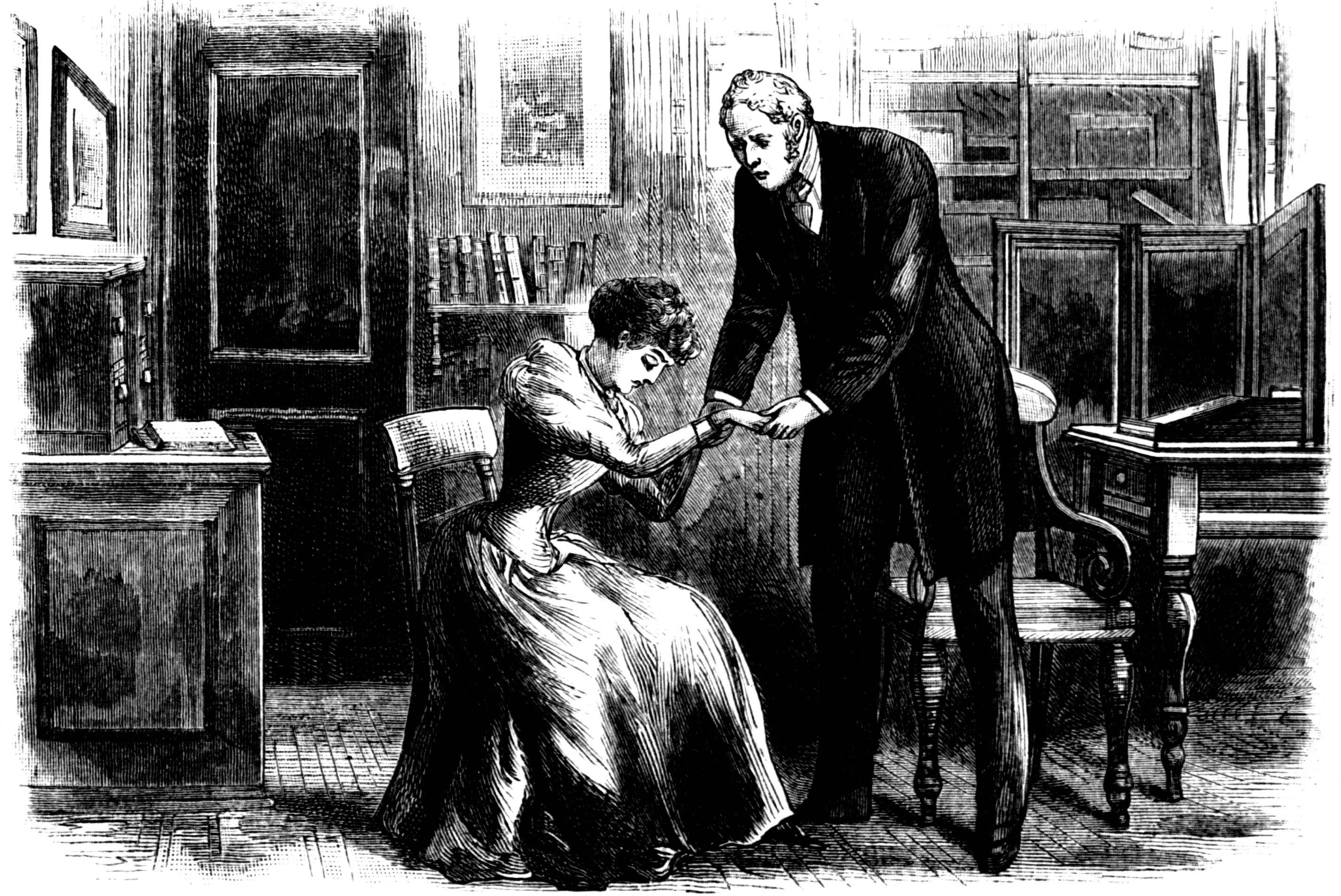

He went up to her and took her hands in his kindly.

“It is a sorry tale for young ears, my child, but I promised a dying woman to tell you, and to hide nothing. Cheer up a little, it ended better than could have been hoped. Captain Ainslie had gone off with his friend’s wife. But Major Winstanley was a modern Don Quixote; he traced them, followed them, and found his wife in a Paris hotel, sobbing with grief for her sin, the consciousness of which could not be effaced in spite of her companion’s attempts at consolation.

“Her husband went up to her and said very quietly, ‘Marion, come home dear.’ To Captain Ainslie he uttered one reproach, ‘What had I done to you to merit this?’ But his heart was broken. He took his wife home, and to the day of his death, which occurred a month afterwards, he showed her nothing but love and kindness.

“When she was left a widow, Mrs. Winstanley found that a bank, in which most of her husband’s money was deposited, had failed—misfortunes never come singly—and so she was reduced to poverty. She thereupon sold her furniture, and came to Abbott Mansfield with her child, changing her name to that of Standen, for she wished to be forgotten by all who had formerly known her. As both she and her husband had few relations, and these but distant ones, her object was attained. She lived quite alone.

“When she knew that her days were numbered, she sent for me and told me all the painful story, making me take it down in writing, to be handed to my executors in case of my death before you became of age.

“By her wish I was to be her child’s guardian, to place her in the care of some trustworthy person, and, on her twenty-first birthday to acquaint her with the facts; also to hand over to her the sum of one thousand pounds, which was all that Mrs. Winstanley had to leave. The interest of this has been paid to Mrs. O’Hara for her care of you.

“I need not tell you, my dear, that no other person has the slightest idea of your identity—or of this story. Here is the paper with your mother’s signature.”

He handed her the document, which she took with trembling hands, looking at the shaking writing “Marion Orme Winstanley” with dim eyes.

“There is nothing to prevent you from burning that here in my library, if you choose. In this box are your certificates of birth and baptism, with your mother’s marriage papers, so that your identity can easily be established with my help. What do you say, my dear?”

“I will take your advice in everything,” Muriel said, faintly. “You have been so kind——”

“Pish! my dear. Had it not been for the expense of having three sons and two daughters to educate, Mrs. Gascoigne and I would have taken you in here. They are all out in the world now, and there is nothing to prevent your making this your home, if you would like it.”

“There is no question of liking, dear Mr. Gascoigne; I could not be such a burden to you. I have thought of using my voice——”

“As a singer? You will require at least a year’s more training. Although Mr. Oateson has given you invaluable help, he has not been in London for years, and the competition is so great that you would stand little chance at present, free as your voice is; and then, it will be very uphill work, my child.”

The old lawyer watched the girl as she looked into the fire, her pale, delicately-cut profile standing out against the dark marble background of the mantel-piece.

“As a child, you played with the boys, and with them you were a general favourite. You liked them all?”

“Ah! how could I help it?” she said, impulsively. “And Kitty and Madge were so sweet with me; they were my only friends, for I felt instinctively that Mrs. Erskine did not wish me to go to the Rectory, and so I kept aloof from Ethel and Dick.”

“If they were not so scattered about the world, Kitty and Madge would have had you to visit them; but India and Canada are so far off. Reginald is coming here for a few weeks before he goes to Melbourne to join his brother. You know that Robert is married out there?”

“Yes. I hope he is as happy as Henry is with his wife.”

“I believe they are much attached to one another. Two years ago, when Reginald came back from Oxford, he told me of something which may, or may not, be news to you.”

“To me?” the girl repeated, meeting old Mr. Gascoigne’s keen scrutiny with amazement.

“Yes; he told me that, subject to my approval, he would, when he was in a suitable position, ask you to be his wife. Have you never suspected this?”

She stood up, staring in silent astonishment.

“Never. I—can hardly believe it. Reginald! We have seen so little of each other—he has been so much away at his uncle’s.”

“That is the very reason why he was struck so much with your beauty and fascination, my dear; the others, growing up with you, had become accustomed to both. Well—is Reginald’s feeling for you reciprocated?”

The girl went up to him, and laid one hand—a little timidly—on his arm.

“Do I understand that—you would sanction it, knowing—who I am?”

“With the greatest pleasure, my child,” returned the old lawyer, smiling. “Your father was a major in a crack regiment, and the daughter of such a man as Major Winstanley is a prize for any man. Tut—tut! my dear,” as she stammered out her mother’s name, “we are none of us perfect. If she sinned, poor woman, she expiated her sin.”

She stooped and kissed his hand, then drew herself upright, and brushed the tears from her eyes.

“You are the noblest man I have ever known. I shall never forget your generosity—your goodness to one who would be treated with scorn and contumely by all who knew her story. With all my heart I thank you and Reginald. Please tell him and that I appreciate the honour he does me to the uttermost, but dear Mr. Gascoigne—I—” she flushed scarlet, and raised her face appealingly to his; “I—have never thought of him in that way, only as a friend. And now that I know who I am,” gathering strength as she went on, “I shall never marry. You will understand me, will you not? I must go right away—to London, and earn my own living where no one knows me. Mary Allen, who used to be at the farm, is married respectably to an ex-butler, and they let lodgings near Russell Square. I can go there, can I not? Please do not be angry with me, Mr. Gascoigne.”

“I am not angry, my dear. Think it all over at your leisure, there is no hurry whatever for a few days. Reginald will not be here for a fortnight. Your money is so well invested that it has increased to fifteen hundred pounds, but that only means about seventy pounds a year, and the lessons will be a consideration. That, my dear, will be my affair; as your guardian I insist upon it, and you will not refuse me. And what about that paper?”

“I will burn it,” said Muriel, putting it into the fire when she had again thanked him. “And when I am successful you will let me pay off my debt, please?” smiling sadly. “If I am a failure——”

“Never despair—you have youth, beauty, and talent; and you have a home here whenever you like to come. By the bye, here is your father’s portrait. His face is a very fine one.”

[Pg 3]

She took it eagerly, and after a long scrutiny kissed it passionately again and again.

“Captain Ainslie must have been a traitor of the deepest dye to wrong such a friend as my father—and he escaped scot-free,” she said, in tones of concentrated scorn and contempt. “No doubt he is living in happiness and luxury, reckless of the misery he caused.”

“He may have really loved your mother. For five years he led a wandering life. Of course he left the regiment, loathed by everyone in it. Then he married, and settled down in the West Indies. I ascertained this myself; but I do not know now whether he is living or dead.”

A railway train is sometimes the scene of much misery in those who travel by its carriages; sometimes of much mirth, most often of the assumed indifference adopted by English people as a rule, and which, despite the contempt with which it is spoken of by dwellers on the Continent, is also the theme of admiration to chatterers.

Two people occupying a first class carriage, of congenial sympathies, can often while away the tedium of several hours. If their sympathies are opposed, they will of course entertain mutual distrust and dislike.

When they are of opposite sexes, and experienced enough to judge of character impartially, friendships are often formed which endure for a lifetime.

“I owe you many thanks for the pleasure you have permitted me to enjoy. I looked forward to a wearisome journey only, but you have accepted my society, and made me your debtor as well.”

“I could not help myself, you see,” smiling.

“But you might have frozen me up in the true British style, and then I should have had to wait in helpless misery for the first stopping-place. You looked very annoyed when I got in at Swindon.”

“I am sorry; but the guard was fee’d to let me be alone if possible. Perhaps the desire of wanting to hide yourself, to get away even from one’s best friends, is happily strange to you.”

He was silent for a little, not looking at her.

Had anyone told Muriel that she would be holding a conversation with a perfect stranger less than an hour after she had started, she would have repudiated the imputation with scorn.

Her nature was a very proud and reticent one, she was not given to sudden confidences.

But there was in her as in all natural women—a hidden spring of impulse, and on meeting a nature sympathetic with her own, she almost unconsciously broke down her guard, with the result that she and her companion were talking as naturally as if they had known each other for years.

“May I hope that you will forgive my presumption in expressing sympathy? You are so young to experience suffering.”

“I am twenty-one in years, but I feel quite old,” she said, quietly. “I am going to London to make my fortune—or to fail.”

“You have resolution enough to succeed, but a woman has many difficulties to encounter. And you aren’t of the calibre to be a governess.”

“Never.” She shuddered a little. “I possess no certificates.”

“Had you a dozen, your face and air would debar you,” he said, with quiet courtesy. “May one ask which of the professions you are wishing to enter? I know a great many people, and perhaps you may allow me the pleasure of being of some service to you.”

“I thank you very much, but I am thinking of the stage.”

He started, and looked at her for a moment or two, at which she laughed, and drew farther into her corner.

“Your offer of introduction had better be withdrawn. You did not expect to hear that.”

“You are right. I did not expect to hear that,” he repeated.

“You think that it is a pity I have chosen this—career?”

“It is fraught with many dangers, particularly for one gently born and brought up with luxury.”

“My father and my mother were; but I lost them both in earliest childhood, and all my life has been passed in a farmhouse amid middle-class poverty.”

“But your friends? Pardon me if I am impertinent; I do not mean to be.”

“I know that you do not,” she said, simply. “My mother had changed her name, so that no one knew me. The lawyer of the place was appointed my guardian; he and his wife were very kind to me, even when—” She paused, then went on again. “I was a great deal with them and their family, in fact, we grew up together. They are all in the world now, most of them married. The girls live abroad, too far for me to visit them.”

“Have you made up your mind to become an actress?”

“It is the only thing I am fit for. I can sing a little; the organist at Idleminster Cathedral was a good musician, and he trained my voice. I used to sing the solo in the anthems and oratorios on special occasions—hidden behind a screen, of course. And I have had lessons in elocution and declamation from an actor. He knew Shakespeare and most of the French and English dramatists by heart. I used to listen to him for hours.”

“What was his name?”

“Gray Leighton.”

He started violently with excitement.

“Gray Leighton. You knew him well. I have been trying to find him for four years. You are fortunate to have had lessons from one of the most gifted actors of the day. Did you know his history?”

“No. He was crippled, and could not stand for more than a few minutes at a time. He came to Idleminster about four years ago, and lived very quietly, making no friends nor ever reciting in public. I got to know him through his little boy. The child was very lovely. I used to play with him, teach him music, and take him out. His father would always trust Bertie with me.”

Watching her lovely face, with its look of sweet girl-woman’s sympathy in the deep clear eyes, the man thought it was matter for small wonder that a father had trusted her with his only child.

“Different versions of his story will reach your ears in London, so it is as well that you should know the truth. Leighton’s professional name was Lyon Fenton. His mother was an Italian, and he inherited her southern nature. As an actor, it is hardly too extravagant to say that he took the world by storm. Paris, Florence, Milan, and Vienna idolised him. He was five-and-thirty when he came to London, and there his slight foreign accent was the only impediment to his success. His Romeo, Othello, Shylock, and Hamlet were the constant theme among critics, who almost to a man praised him. But he did not like London and left it after the second year for Italy. On the eve of his marriage with a beautiful young actress who played Juliette to his Romeo, his fiancée eloped with his best friend.”

Muriel was listening with breathless attention, her eyes full of indignation at his last sentence.

“What horrible treachery!”

“Unfortunately no new thing. The girl was duped into believing some base fabrications about Fenton, and impetuously went off with the man who considered nothing so long as he attained his object. Fenton followed them, and a duel was fought, in which he was unfortunately wounded in the hip. His adversary escaped, for Fenton generously fired in the air rather than injure the man who had married the girl he himself loved.

“Here you have the man’s character—erratic, quixotic, impetuous, but noble to the core.

“When the girl discovered her husband’s treachery she poisoned him and herself, leaving a letter for Fenton, entreating his forgiveness. The child Bertie is theirs.”

Muriel drew a long breath, unconscious that tears were trembling on her eyelashes.

“Oh!” she said with feeling, “what a tragedy, and all occasioned by a man’s perfidy. The world has lost a great actor, whose whole life is spoiled. Then Mr. Leighton is not Bertie’s father?”

“He has never married; the man’s nature is not one to change. He must be about five-and-forty now. I knew all this, as I was a personal friend of Fenton, for whom I had the greatest admiration. But when his injury necessitated his leaving the stage, he disappeared, and none of his former friends nor acquaintances ever heard of him. Knowing his sensitive nature, I understood, and did not try to find his whereabouts. From time to time he sent me tidings, but it is quite four years since I heard anything.”

“How strange it is that we should both know him,” Muriel said, reflectively.

“Very. I can understand your desire for the dramatic profession if you have been under the spell of Leighton’s influence. He gave you lessons, you said?”

“Three times a week for the last two years and a half. I thought it wisest to prepare myself as much as possible; but I did not like to tell Mr. Gascoigne, the lawyer, that I was thinking of the stage. He knows that I can sing a little, and that I am wanting to come out by-and-bye.”

“It is but a step from the vocal to the dramatic stage,” he said, smiling a little. Then, very gravely: “I have lived so many years longer in the world than you, that you will possibly permit me to give you my opinion. For one absolutely alone in the world, as you are, of gentle birth, you will be cruelly exposed to fearful dangers, from which it will be next to impossible to escape.”

“But I am not so very young,” she said wistfully “and the Gascoignes will never lose sight of me, I think. I am going to live in Bloomsbury, with a very respectable woman and her husband who let lodgings, and I should pay her to accompany me to the theatre. She used to be one of the maids at the farm.

“What other can I do? I have about £70 a year of my own, which will just keep me from starving; barely that in London, but I detest the country. I cannot be a governess, nor serve in a shop. Mr. Leighton has given me two letters of introduction to the managers of the ‘Coliseum,’ and ‘Opera Comique.’”

“So, then he has a very high opinion of your powers or you would not have obtained those introductions.”

“To the two best theatres, owning the most critical of managers? But I would rather be condemned by them than praised by the inferior ones. Mr. Gascoigne has promised to come up and see me in three or four weeks, and I am to go down there for Easter. I suppose he thinks that I shall fail.”

They were nearing Charing Cross by this, and Muriel looked out at the densely packed houses.

“Is this your first visit to town?”

“Yes,” she said, wondering whether he would tell her what his name was, or whether they would never meet again.

“In a very short time we shall have arrived,” he said quickly. “You will permit me to say that I hope we shall meet as friends? Here is my card. Please do not look at it now—I have a reason,” meeting her look of inquiry with a smile as he handed her the little slip of cardboard to her. “If you will grant me permission I will send you seats for the ‘Coliseum’ to-morrow, as I—know the manager, Mr. Harbury, and so it is nothing. You will like to see Hamlet?”

“Very much indeed. I have the greatest longing to see Francis Keene, and to compare him with Mr. Leighton.”

“He will not bear the comparison,” her companion smiled. “You would not, I suppose, entertain the idea of acting as secretary to a literary man?” he said presently. “And possibly writing his wife’s letters as well? I have a friend who is wanting a lady in that capacity, and I think you would suit him admirably, that is, if I am not too impertinent?”

“Oh! no; you are very kind to think of me. How you must dislike the stage,” laughing a little, “to endeavour to persuade even a stranger to leave it alone.”

[Pg 4]

He turned to her and held out his hand.

“It is because I no longer think of you as a stranger, Miss——”

“Winstanley,” putting her hand into his.

“Thank you. I will give you the address of my friend, so that if you should care to see him you might write in a day or two; in any case, he would be a good person for you to know. May I mention your name? His wife gives ‘At Homes’ every Saturday, and you would meet many professionals there. Here is the address.”

“Meanwhile I am not to know of whom I am to think as a true friend.”

“Until the day after to-morrow,” smiling; “that is if you think your landlady will accompany you to the theatre. I imagine you see that you have no one else at present, though that will not be for long.”

“Mrs. Armstrong will look rather strange—”

“She will not be noticed much in a box. Here we are. What a pleasant journey it has been. Shall I get you a cab?”

And as Muriel found herself driving to Charlotte Street in a hansom she thought that if all her days in London were only half as pleasant as this had proved, she would never have cause to regret leaving Abbot Mansfield.

The “Coliseum” was crowded as usual.

Nine months in the year the cultivated and impassioned acting of Francis Keene drew rapt admiration from packed audiences, who listened to every syllable that fell from his firm mouth.

As lessee, stage-manager, and principal actor, he had his hands full, and his genius for staging a play from Shakespeare downwards was known throughout Europe.

Critics could find no flaw in this, though they occasionally differed about his rendering of a part.

His tall, well-proportioned figure moved easily on the stage, and the clearly-cut features and musical, perfectly-trained voice were especially fitted for picturesque rôles, although Keene was too true an actor to adhere to them.

His Shylock was as fine as his Romeo, and King Lear as Benedict, Othello as Iago.

Down in rural little Abbot Mansfield his name of course was known, but as he was particularly averse to being interviewed and would not allow his photographs to be exhibited in any shop or photographer’s window, his face was totally unfamiliar to Muriel Winstanley.

Even Gray Leighton had no portrait amongst his large collection of celebrated members of the profession.

Her delight at being about to witness the finest play of the greatest dramatist the world has ever produced, and of seeing the great actor in his favourite part—many pronouncing him to be absolutely unrivalled in it—was so intense that she was strung up to the greatest pitch of excitement.

Mrs. Armstrong had been with her husband in the pit she told Muriel, and in her own language, “he looked that beautiful, miss, but so sad as made me quite miserable, I did want him to ’ave ’ad the poor young lady all comf’table at the end, and she so pretty, but it goes contrary all through.”

Muriel’s black evening gown would not attract much, if any, attention she hoped in their box on the second tier, and Mrs. Armstrong was, as she expressed it frequently, that flustered at being for the first time in such an exalted position, that she kept well backward from observation in the intervals between the acts.

It was a grand performance.

Keene’s theory was that Hamlet was a man about thirty years of age.

His eccentricity and madness merely assumed of course, and in the scene with Ophelia, his

“Get thee to a nunnery, go,”

was uttered with regretful longing rather than peremptory harshness, great love for her was revealed beneath the stern language, and his last wild embrace was full of a man’s passionate agony in parting from all that made life worth living to him.

The girl sat as one entranced, drinking in every word, not letting a single gesture escape her keen scrutiny.

Her eyes flashed responsively, her breath came in gasps, she was deaf and blind to her surroundings.

Once or twice Keene himself glanced up at the beautiful sympathetic face, and his own eyes glowed with quiet triumph.

“My dear, Mr. Keene was perfectly right to advise you as he did. A man of the world’s advice may always be taken in matters of this sort; and a girl who lives alone is always open to criticism, you know, even if she have no relations.”

“I am singularly fortunate in my friends,” the girl said, with a bright smile. “Mr. Gascoigne says I was born under a lucky star.”

“In meeting Mr. Keene you were undoubtedly,” Mrs. Carroll said, with a swift look at the tall, graceful figure bending over the escretoire; “but if you knew how many failures Mr. Carroll and I have had in trying to get a lady secretary, you would say that we were the lucky people. There seemed to be no chance of finding what we wanted. If a girl were clever, she was vulgar or self-assertive; if lady-like, utterly stupid, or worse still,”—laughing—“weak and incapable of holding an opinion. Perhaps the most objectionable type was the girl of the period—masculine, irrepressible, and in fact——”

“Full of bounce,” added Mr. Carroll, laughing and looking up from the Times; “like Miss Morton, who dictated to me instead of taking down my ideas. I assure you, Miss Winstanley, that she argued about every chapter in ‘Young Calderon’s Career,’ until I suggested that she should write a novel herself and leave me to my own little sphere.”

“I wish that I knew shorthand,” Muriel said, presently, getting paper and pens ready; “it would be so much quicker for you.”

“But it entails re-writing into longhand, whereas you get my MSS. all ready for the printers. No, I prefer this way; you are the quickest longhand writer I have ever known. I am only afraid that just when you get into my ways and ‘fads’ you will blossom into a Mrs. Siddons, and I shall be in misery again.”

The girl laughed.

“Mr. Keene is too severe a critic, and since he has so very kindly undertaken to bring me out, he will not let me do anything in a hurry. It will be months yet, I expect.”

“Humph! I hope it will,” muttered the novelist. “My dear,” to his wife, “have you any letters for Miss Winstanley this morning, because the sooner I can begin the better.”

“Only a few more invitations for my ‘At Home’ on the 25th,” said Mrs. Carroll; “here is the list. And a line to Lady Hetherington to say that I expect her and all her party. I wish she were more æsthetic in her tastes—her friends are so often objectionable; but it cannot be helped.”

Muriel wrote the letter and the invitations rapidly in her clear, somewhat eccentric, handwriting, then handed them to Mrs. Carroll, who passed into the adjoining room, which was only separated by gracefully-draped curtains, for the novelist and his wife were original enough to care for one another after ten years of married life, and Mr. Carroll liked to have his dainty little wife always in view whilst he was dictating, and even composing.

Her morning-room and his library were thus in juxtaposition, and as he walked up and down, with his notes or MSS. in his hand, smoking an eternal cigarette or cigar, he would catch a gleam of her golden hair, as she sat surrounded by a pretty mass of crewel silks and broideries.

Muriel got an hour or more before ten o’clock a.m. for study, and after two o’clock she was free, Mrs. Carroll only asking her to accompany her in her drives and calls as a friendly request, to be refused or accepted at will.

She would drive her down to the “Coliseum” when Mr. Keene had wished her to witness a rehearsal; and in the evenings there were always stalls or a box for one of the theatres, for Muriel was to see and hear everything by way of gaining experience.

She herself did not know what Mr. Keene[Pg 5] had informed the Carrolls, who were his greatest friends.

That Gray Leighton had so carefully trained her in voice, gesture, manner, expression, having the most responsive ground to work upon, she was so well drilled in Shakespeare, Sheridan, Molière, Racine—in fact, in the brilliant actor’s splendid repertoire—that personal experience was the one thing lacking to develop her splendid powers.

She knew now that Keene and Leighton had been friends united by the closest sympathy.

The older man lacked the younger’s sustaining power, which at five-and-twenty—his age when Leighton left England—was not at its full zenith of course.

Leighton had at once perceived his young rival’s strength, and knew that his own fame would never be so lasting.

The critics had condemned a too great enthusiasm in him, alleging that his excitable nature led him to expend himself too soon in a play; that, in consequence, his finale was apt to be lacking in the interest felt by his audience in the early part of the evening.

Keene had felt the greatest admiration, however, for him, and he had spoken to Muriel as he had thought from the first, his own modesty underrating his own capabilities.

As a manager he knew that he himself had no living equal.

Sparing no pains, care, nor expense, he searched the world’s most remote corners for unique talent and objets d’art, so that he never incurred the mortification of reading that his productions were “one-act plays.”

All the minor rôles were as carefully rehearsed as his own, and the actors in his cast, even the very servants, received the most tempting offers and larger salaries than were usually paid—by outside men as inducement to leave the “Coliseum.”

“Are you ready, Miss Winstanley?” asked the novelist, as Mrs. Carroll left the room. “I don’t mind if you stop me twenty times; but for Heaven’s sake don’t go on too fast and get muddled. I have only notes here, you know. Where did we leave off?”

“The twins want to go to the theatre—the Gaiety,” said Muriel, in tones of suppressed laughter, as she read what she had written. “‘Let’s pit it to-night,’ whispered Henry. ‘Ma’s in the humour to fork out, as the lodgers have paid up.’”

“Got that? All right then,” and Mr. Carroll began striding up and down, puffing out smoke, and looking at his notes.

“‘How much are you worth?’ asked Henrietta. ‘I’m stumped.’

“‘Two bob. But I shall make her give us five, and we can go on the top of a ’bus. You go and eat some sandwiches, and I’ll tackle her now. She can have a flirtation with the major all the evening.’

“‘Poor wretch, I pity him!’ said Henrietta. ‘Ma will talk about her poor husband until he’ll wish himself out of it. I do want to see the serpentine dance. It’s lovely.’

“‘You’ll be trying to do it with a table-cloth, to-morrow,’ sneered Henry. ‘You’re mad on dancing.’

“‘I’d rather be mad on dancing than on lodgers,’ Henrietta answered, epigrammatically, bouncing out of the room. ‘You get the cash,’ she called as a parting shot.”

“What are you laughing at!” Mr. Carroll asked, in surprise. “Do you find it amusing? It is very vulgar, of course; but I assure you, no exaggeration.”

“It is very wonderful to me,” Muriel said, taking a fresh sheet of paper, “that you can philosophise so deeply when you please, and then put in a chapter like this—the variety is unique.”

“The publishers tell me that it is what the public like. Life is not all beer and skittles, you know, and yet if it were, we should very soon tire of them. There were two little brutes who talked just like that in a place where I stayed once in my young days. ‘Chapter thirty-four. The howl of the pessimist is one of the signs of the times, one that cannot be checked too strongly, for it is the outcome of a discontent fatal to any great achievement, and as false as it is hurtful.’”

A dissertation on pessimism followed, and quotations from so many classical authors of olden and modern time as showed that the author knew his subject thoroughly, and was a man of no mean understanding.

Mrs. Carroll’s “At Home” promised to be a very brilliant affair.

There were two ambassadors coming, the latest social “lion,” and the most brilliant members of the legal, literary and dramatic professions.

Mrs. Carroll had asked Muriel to go with her to Madame Irène’s about ten days beforehand, for she said she always felt more comfortable if she put on her gown before a friend whose judgment she could rely upon.

All innocently Muriel assented, and expressed genuine admiration when the dainty little woman had herself arrayed in soft, thick brocade of the colours of almond blossom and delicate green leaves, with some real old lace on the bodice.

“It doesn’t make me look too old? My husband likes handsome materials,” she said, anxiously.

“Mais, madame is superbe,” the Frenchwoman said, clasping her hands.

“It suits you perfectly, Mrs. Carroll. Everyone wears brocade now, and you will never look old,” Muriel said, smiling.

Mrs. Carroll gave a sigh of relief, and then turned to inspect some white silks that were hanging over chairs.

“Do you like this, Muriel?” she said, touching one of the thickest.

“It would suit mademoiselle,” said Madame Irène, looking at the delicate complexion and the waves of deep gold hair.

Muriel shook her head.

“I am in mourning—”

“But you will look sweet in white,” said Mrs. Carroll. “You must have a new gown too. Madame, can you make one in time?”

And, in spite of the girl’s look of entreaty, the little woman carried her point, laughingly telling her as they drove home that she had arranged it beforehand with her husband.

“We wanted you to look your best, and white is so becoming for girls. Old married people can do anything, you know,” she added, with a bewitching little smile that went to Muriel’s heart as she tried to thank her.

Very lovely she looked on the night in the long straight folds of the perfectly-fitting gown, with some white moss-rose buds fastened at her breast.

They had been sent to her anonymously, and she thought it was merely another of Mrs. Carroll’s many kindnesses.

She could not resist the pleasure of wearing them, although she discovered her mistake when she made her appearance in the drawing-room.

As soon as the rooms began filling, music, songs, and recitations succeeded each other, there being so many professionals present that there was no danger of ennui.

Muriel played and sang, Signor Losti, the great master, taking a great fancy to her voice, and, finding that she knew Gray Leighton, striking up a friendship on the spot.

Mr. Keene came on from the “Coliseum,” and, heedless of fatigue, took his part amongst the performers with the winning courtesy so often seen in great artistes.

He said little to Muriel, seeing that she was surrounded by a circle of admirers, until late in the evening, when Mrs. Carroll approached him and asked with a smile if he would give them one more delight.

He smiled and went up to Muriel.

“Miss Winstanley, are you tired?”

“No,” she smiled, rising instantly, wondering a little at his question.

“I want you to recite with me.”

“I?” starting back and turning white; “Mr. Keene—you are cruel!”

“No,” he returned kindly, “I am quite sure that you can if you will. You will not be nervous?”

“Horribly—I—perhaps by myself I could, but with the greatest actor of the day, it would be such a terrible ordeal—”

“No worse than with Gray Leighton. Come and rehearse with me.”

[Pg 6]

Trembling, she placed her one hand on his arm and he led her through the conservatory, across the hall, into the library.

“Do not be so frightened, child. You are positively shaking,” he said, putting one hand on her shoulder. “Imagine that you are in Leighton’s library in Idleminster and that I am he. You know Beatrice’s lines in Much Ado? Yes, I am sure of your memory. Take me up in the Church Scene, Act IV. Exeunt Friar, Hero and Leonato. Beatrice and Benedict are alone.”

He went back a few steps to give her time to pull herself together, then approached her with:

“‘Lady Beatrice, have you wept all this while?’”

For one instant only she hesitated, the remembrance of the scene with its dawning of passion under cover of the exquisite badinage sending a flood of colour to her face.

Then she gave her answer—

“‘Yea, and I will weep awhile longer,’” with trembling excitement, giving the sound of indignant tears in the rich but wondrously sweet tone, trained to perfection by Gray Leighton’s sensitive ear.

The scene went on to its end without a break.

Keene, knowing the passionate nature of the girl woman, letting himself reveal the great love of Benedict despite the laughing nature, and the torrent of light jest that rolls from his lips.

She rose to it, keeping well under control even when with the confession of her love almost unconsciously forced from her:

“‘I love you with so much of my heart, that none is left to protest.’”

He caught her to his heart, kissing her hair as he murmured passionately—“Come, bid me do anything for thee.”

She paled, but laughed as he released her, with sweetest witchery pelting him with taunts until he protests:

“‘By this hand, Claudio shall render me a dear account,’” and the scene ends.

She stood perfectly still, then swayed a moment, falling on a chair as he went forward.

Seeing the severe tension to which her nerves were pitched, he left her again, quietly looking over some books, but watching her covertly, knowing she would not faint now.

And in a few minutes she drew a deep breath and got to her feet again, going to him, her eyes asking the question her lips could not utter.

He took her hands in his, pressing them with a strong close grasp.

“I am satisfied. You are worthy of Gray Leighton’s tutelage. I will prove my words soon. Meanwhile—hush, child, do not give way now,” her features were quivering as she read the enthusiasm in the strong, intellectual face looking down at her so kindly. With a great effort she forced down her emotion and murmured, brokenly, “How can I thank you?”

“By coming back with me and going through it again before Mrs. Carroll’s guests. You can—will you? You can trust yourself?”

“Can I, Mr. Keene? For God’s sake think—can I?” she asked, looking at him with all the anxious longing of a great soul in her beautiful eyes.

He gave her his arm with a reassuring little nod, and they entered the drawing-room.

Keene took his hostess aside and explained in a few words. Then, turning to Muriel, led her to the centre of the room, and simply announced the scene.

She did not hesitate now.

Clear as a bell her laughter rang out, her gestures full of quaint witchery, void of ordinary theatrical assumption, her manner that of a perfectly-bred lady as she alternately yielded and taunted Benedict.

There was a storm of applause as they finished, from every one of either sex.

Again and again Keene was pressed to give an encore, but he knew that the girl had been taxed to the uttermost for that night, and he let her go.

Old Losti went up to him and muttered a few significant words—

“My friend, do you know what Scott Roberts has just said to me? Mr. Keene will do well to transplant that diamond to the ‘Coliseum.’”

The actor’s eyes flashed, but he said curtly—

“I say nothing, for I do not know myself. Miss Winstanley is only an amateur at present.”

Later on when the guests had all departed Carroll, who had been enjoying a cigar, strolled up to Keene, who was making his adieux to Muriel and his hostess.

“Do not hurry, Keene, have a cigar in the library, the ladies will not object to two smokers, and they can stand umpires.”

“Why?” laughed the other, as he looked for Mrs. Carroll’s permission before lighting up.

“You know the misery I have endured for the last year with inefficient secretaries,” said the novelist, with mock indignation; “my hair nearly turned white with worry. You introduce a pearl beyond price to me, and when I begin to breathe freely—it’s perfectly monstrous, Keene. You are going to turn her into a Ristori, and leave me to my misery again.”

“My dear fellow,” the other rejoined, laughing; “can I or any other man make a Ristori out of a nonentity? Miss Winstanley’s inner consciousness told her long ago in what direction her talent lay, and Gray Leighton confirmed her. I have done nothing but test my friend’s pupil—and I find what I expected.”

“She is too good to be kept back,” Mrs. Carroll said, kissing Muriel, who was flushing and trying to escape. “Much as I regret it in one way, for we shall be the losers, it would be unfair to attempt to dissuade her. And you know, Colin, that Mr. Keene told us from the first——” she stopped, laughing. “The mischief is out; forgive me for my indiscretion.”

Muriel had turned quickly to the actor, her eyes sparkling.

“Ah! please tell me, Mr. Keene. Did you think—before—that I——

“Could act?” enjoying her confusion quietly. “Yes, Miss Winstanley, after I had spoken to you for half-an-hour I felt convinced that you had a great talent for the stage; and the more I knew you, the stronger grew my impression. To-night you have given us all proof, and I am sure,” with a smile at the Carrolls, “that no one of your friends would wish to rob the histrionic profession of one of its future stars. Having had the advantage of two or three years of such excellent training, there need not be such long delay as is necessary with a complete novice. Experience is requisite, after which I hope you will have a brilliant career.”

“Abominable!” cried Carroll. “If you were not beyond criticism, Keene, I would get Scott Roberts and Alex. Fraser to slate your next production. But you stand on such a deuced high pedestal that no one can touch you.”

They all laughed as the actor rose to go, Carroll putting his arm around his shoulders as they left the room.

The two had been close friends for years.

True to his promise, Mr. Gascoigne came up to town and saw Muriel.

She had of course told him of her good fortune in meeting with the Carrolls, and when he saw the genuine affection they both felt for her, and heard from the novelist how delighted he was with his new secretary, he strongly advised her to give up the idea of using her voice in any way as a professional.

She smiled, but Mrs. Carroll told him of her triumph with Mr. Keene, and of his sanguine prognostications for her future, and the old lawyer raised his eyebrows.

“I have seen Francis Keene in most of his best rôles. He is not the sort of man to take a sudden fancy I should say. He is considered one of the most relentless of managers and sternest of critics; if he asked you to act with him, Muriel, your future is evidently decided, and you are to be congratulated.”

“We hope to keep her with us for as long as she likes to stay. My husband is so happy with her secretarial work that he dreads the time when she will not have the leisure,” Mrs. Carroll said, looking at Muriel affectionately.

“Well, it is of no use for me to remind you of your promised visit to us at Easter,” Mr. Gascoigne said, when leaving. “As things are it would only make a break, I suppose. You know you have only to come, child, when you like. Let me have a wire or a letter when your first appearance is arranged, and I will run up to applaud you. Mrs. Gascoigne sends her dearest love; she is, as you know, too much of an invalid to travel. Reginald wanted to see you very badly, but I thought I would come alone this time. You can let him have a message if—the wish should ever prove reciprocal,” he added, laughing grimly.

“Oh, I shall not do anything for a very long time yet,” the girl said, shaking her head, leaving the last sentence unanswered. “As you say, Mr. Keene is far too particular to recommend me anywhere until I am pretty certain not to disgrace his introduction.”

About a fortnight after Mrs. Carroll’s “At Home,” Muriel was sitting alone in the drawing-room one afternoon, playing some of her favourite Chopin’s nocturnes.

It had been a wet day, and Mrs. Carroll, who detested rain, had gone to her room to nurse a headache.

The servant announced Mr. Keene, and Muriel got up quickly.

“Mr. Carroll is out, and Mrs. Carroll is in her room, but I will go to her——”

“I came to see you, Miss Winstanley,” he said, quietly. “Miss D’Orsay broke down after acting last night, and the doctor says she must go abroad at once, as her chest is very delicate. Her understudy, Miss Cameron, is in great trouble, for her mother is dying. I gave her permission to go down to Bath yesterday, and I shall be sorry to have to wire to her for to-night.”

“To-night?”

“Yes. Miss D’Orsay is too ill. Besides, she cannot speak above a whisper. Will you take her place with me?”

The girl looked at him with wide open startled eyes.

“You ask me to act in the ‘Coliseum’?” she gasped. “Merciful Heaven! Am I dreaming?”

“No. Listen. I intend to put on ‘Much Ado About Nothing’ in a fortnight, and after you went through that scene with me, I meant you to be my Beatrice. Ophelia is not a difficult part except for the mad scene. Your voice is so exceptionally fine that the songs will be a great feature. If you know the old music you know mine. Nothing is new. Will you do it? You are word perfect, of course? Gray Leighton was so wrapped up in ‘Hamlet,’ that you must have often rehearsed with him.”

“Yes. I am word perfect,” said Muriel, slowly. “I have done it many times, and I know the music; but——”

She raised her eyes piteously to his face.

“Will you do it as a favour to me?”

“Can I face the audience, Mr. Keene? That is my only fear.”

“Yes, or I would not ask you. I do not count a failure at the ‘Coliseum,’” he said, smiling. “Will you come back with me and rehearse at once? I have all the people there, and we have over three hours. You shall dine at the theatre.”

“Then you were sure of me?” she said, smiling in spite of herself, and the colour crept back to her face.

“I felt I might rely upon your sympathy and[Pg 7] help,” he returned, taking her hands and pressing them closely. “You see that I am in a difficulty, and I am selfish enough to come to you.”

“How you put things,” the girl said, flushing. “I will do my best. I shall never dare to look straight in front of me, and if I die for it I will get through my part somehow.”

“Thank you. Then there is no time to be lost. Will you let Mrs. Carroll know and put your hat on? You shall have some tea after the first rehearsal.”

Mr. Carroll entered at that moment, and as Muriel passed him, she struck a sudden attitude, crying laughingly:

“Behold Ophelia of the Coliseum Theatre!” and left the astonished novelist to receive explanation from Keene.

In less than a few minutes she was back again in a picturesque big feathered hat and cloak, with some thick, fluffy furs round her throat.

The actor’s brougham was waiting, and Mr. Carroll put her in, promising to be at the theatre with his wife as soon as possible.

Keene had remembered every detail.

A dressmaker was in attendance to make alterations in the dresses.

Every employée was ordered to go into the auditorium.

All the cast had been requested to attend for extra rehearsal before Muriel had been electrified by being asked to take the part.

There was hardly any hitch.

She was not only letter-perfect, but every gesture even to stage business had been carefully drilled in her; and her own rare receptivity and lightning-like perception saved her from many errors.

She had acted before in the little theatre at Idleminster, but the difference from that to the big, stately grandeur of the ‘Coliseum’ was appalling.

But Keene never took his eyes off her.

Before going on he told her that she was to turn to him for every direction without fear.

“No matter how slight your doubt, let me know.”

And she obeyed him to the letter.

So much so that after the first rehearsal of Ophelia’s part, he directed her to play to the house.

Carroll had come down with about a dozen friends hastily collected, and these, with the employées, made a good appearance in the stalls.

With a few directions, which were given in an undertone, under cover of mere conversation, the girl went through a second time.

“Let yourself go,” said Keene. “Don’t be afraid.”

“You have acted before?” said Rivers to her, who played Laertes. “But I have never had the pleasure of seeing you. I fancied that—from something Mr. Keene said—you were a novice; but I see my error. As he approves of course there can be no doubt of your success. He is well pleased I know.”

“This is my first appearance in London,” she said, quietly. “I have taken parts in a little country theatre.”

He stared at her for a little.

“Then you have genius, Miss Winstanley,” he said, with courteous respect, and Keene approached.

“You have done better than I hoped. It is needless to give you more fatigue. Go and rest until seven. Will you dine here?” to the Carrolls and two eminent critics who had come down out of kindness and friendship for Keene. “It will save you the trouble of going back, and it is past six already.”

They at once accepted, and a very merry party it was.

Keene took care that Muriel had a good dinner in spite of her protestations that she was too excited to eat, and some very especial Mumm was produced to wish her success.

11.30 p.m.

It was over.

The theatre was just empty.

Mr. Keene’s room was crowded, and Muriel’s name was in everyone’s mouth.

She was a success.

Three times had she been called before the curtain, trembling so that Keene had grasped her hand tightly, and the last time almost carried her to Mrs. Carroll who was awaiting her in the dressing-room.

“Her fortune’s made!” said Scott Roberts, as he and Alex. Fraser went to greet her when Mrs. Carroll brought her to the green-room.

“As usual, Keene’s on his feet. I did not see her bit of Beatrice the other night——”

“I did,” nodded Fraser. “She was delightful. But anything like her acting to-night has never been heard of. All in a minute, you know. Marvellous I call it. And never hesitated for a word.”

“I am glad you are pleased,” Muriel said, simply, but flushing with pleasure at the tone of genuine praise. “I was so horribly frightened and nervous when I heard someone say the house was packed that I thought I should have made an idiot of myself.”

“You positively looked at the audience,” said Carroll. “Bang into the boxes too. My dear child, to talk of nervousness after that! You are a fraud!”

“That was only when Mr. Keene was on the stage with me. I did not feel so afraid then.”

“Your mad scene was quite novel. May one ask whether your rendering was entirely original, Miss Winstanley?” asked Alex. Fraser.

But Keene came up, and laughingly pushed him aside.

“Go home and write your ‘copy’ Fraser. She has had enough of it for one night, and I will not have her interviewed. When you have seen her as ‘Beatrice’ on my stage you shall hear who trained her.”

And by-and-bye the Carrolls took her home.

For one minute, as they were waiting for the brougham and the attention of the Carrolls was taken by some friends, Muriel turned to the actor, who was standing close behind her.

“You have not criticized me,” she said, wistfully. “Mr. Keene was I even half what you expected? Shall I ever be good enough?”

He leaned down to her, speaking in her ear.

“I will answer your question to-morrow. I cannot thank you to-night.”

Then aloud:

“Will you be round at five o’clock to-morrow, Miss Winstanley, please? I should like you to go through one or two scenes with me—a full rehearsal will not be necessary.”

“I will not fail,” she said, giving him her hand.

As they were driven away, Mrs. Carroll took her in her arms and kissed her.

“You were simply wonderful, my dear. Everyone was electrified, and even after the other night I could hardly believe my eyes. We shall lose you now.”

“Not a bit of it,” said her husband. “She must live somewhere, and why not with us? And she can still help me in the mornings, eh, my dear?”

“How good you are to me,” she returned, gratefully. “Of course I will, Mr. Carroll. But when Miss D’Orsay gets well I shall have to wait perhaps a long time——”

The novelist laughed.

“You made a hit, my dear; your singing alone was worth hearing. Keene was pleased, though he said nothing; he seldom does. Think of it. You have made your début on the stage of the ‘Coliseum,’ acting with the greatest man of the time, not as a super either but as leading lady. I shall put you into my next novel, and everyone will say how far-fetched is the plot.”

The next day Mrs. Carroll drove her down to the theatre, saying she would return in time to take her back to dinner.

As Muriel went to the green-room, Keene came out of his own and led her in, merely greeting her in his usual courteous way.

The room was empty, and the girl looked round a little wonderingly.

“Am I to rehearse here instead of on the stage?”

He did not answer for a moment.

She threw aside her wraps and stood waiting until he approached her quite closely.

“I have heard from Miss D’Orsay that it is uncertain whether she will ever be strong enough to return to the stage,” he said distinctly, but in low tones. “Will you accept the position of leading lady, Miss Winstanley?”

She drew back a few steps, staring at him in bewilderment, her deep eyes looking almost dazed.

Then they flashed, and she ran towards him with outstretched hands.

“Ah, you cannot mean it, you cannot,” she gasped, breathing convulsively.

He took her hands in both his own, and drew her towards him very gently, looking into her eyes with such intensity that she felt he was reading her very soul.

Her colour came and went with each breath.

She was powerless to resist the strong magnetic influence felt by all who knew Francis Keene.

“Yes, I mean it. I offer you the post for life if you will accept it. I want you to play Beatrice to my Benedict for all time. I have loved you from the time of our first meeting. Am I too presumptuous, or do you care a little for me? When I saw my roses in your breast, when you yielded to my caress that was inevitable then, I fancied that my touch had power to thrill you. Muriel—”

Her eyes sank beneath his, and he held her close to his heart, stooping until his lips rested on hers.

For a moment she rested so, then, with a sudden shudder, she drew herself away.

“You do not know who I am,” she whispered hoarsely. “My mother—was—guilty of a great sin.”

“Do not tell me, my child,” he interrupted. “I love you. Whoever or whatever were your people and their doings is nothing to me.”

“I can never marry,” she said, clasping her hands to her heart, and speaking with passionate strength, “for if ever I meet a man named Philip Ainslie I will kill him. He merits death. If he has any descendants I will tell them of their father’s iniquity.”

Keene started violently, and looked at her with amazement in his face.

Then he went slowly to her, and put his hands on her shoulders.

“My darling, what phantasy is this? Philip Ainslie was my father. I am his eldest son, Francis Ainslie. How has my father wronged you?”

He never forgot the horror and misery that his words brought into her features, nor the pathos with which she recoiled, shuddering in every limb.

“Oh, dear God! You, Francis Ainslie——”

“Keene is my theatrical name. What is it, my child? What is the sin?” he asked, very tenderly. “Come to me and tell me.”

But she shrank from him, pressing her hands to her eyes as though to shut him out from her sight.

“You—you—” she moaned. “I cannot tell you—I cannot——”

With two steps he caught her in his arms, crushing her resistance with unconscious strength, pressing passionate kisses on her pale, quivering lips.

“You love me—you cannot deny that. I will yield you to no other, listen to no reason that can separate you from me. By this kiss I swear that you shall be my wife. Now tell me,” releasing her, “what was the wrong done by my father? What did he do. Tell me, Muriel.”

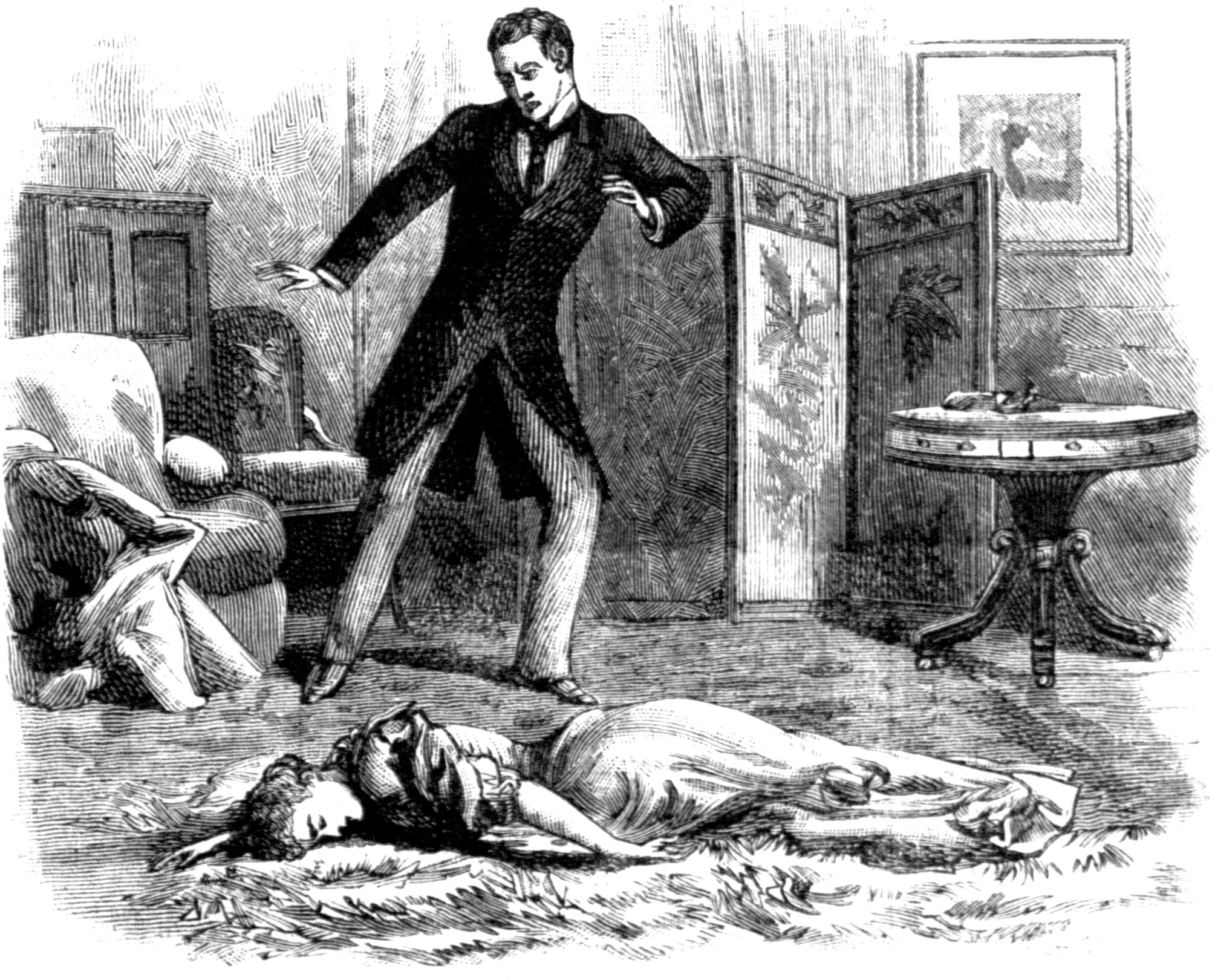

White as death, she met his look and answered faintly—

“He betrayed my mother and murdered my father.”

[Pg 8]

Then, before he could prevent, slipped to the ground.

For the first time in her life, she had fainted.

He raised her to a chair, and fetched brandy himself, but it was some minutes before she opened her eyes.

As soon as she was fully sensible he made her drink some brandy mixed with water, fairly pouring it down her throat.

Then he spoke to her, firmly holding her hands in a strong grasp.

And by degrees, with her face hidden on his shoulder, she told him the story of Ainslie’s treachery, her mother’s weakness, and of her father’s nobility, though it cost him his life.

As she finished she drew away from him and spoke very quietly—

“You see that I could never be your wife. I could not marry the son of my father’s murderer. Do not seek to persuade me.”

“Listen to me, my darling. My father was not a good man. He married at one-and-twenty my mother, a beautiful girl of seventeen, and in two years he deserted her after breaking her heart with his cruelty. She died when I was little more than six years old, but after nearly thirty years I can see her lovely face still, with its look of eternal unhappiness. I was educated at a monastery in Florence until I was eighteen, and I never saw my father’s face nor knew that he existed; he had made no sign nor troubled himself to know if I were living or dead. My mother’s father had settled some money upon me, which made me independent. When I came to England and went to Oxford I found that my father was living—that he had re-married. But though I sought him out, he betrayed such little interest in me that I left him, declaring that he would never see me again unless he summoned me.

“I carried out my own career without his aid. His life was a very unhappy one, his second wife was a woman who was my mother’s opposite entirely—strong, domineering, extravagant. He died two years ago, before I could go to him, of a painful disease.

“You see, my darling, that I knew nothing of his sin against your father—it must have been committed whilst I was in Florence. I will not press you now—you will require all your strength to act to-night. In a week from to-day I will hear your decision.”

And as she got up wearily he took her in his arms and kissed her quietly with a strength and mastery that were irresistible.

Neither by word nor look did Muriel feel that the man with whom she acted night after night remembered aught of their conversation concerning her mother’s and his father’s sin, nor of the love that he had shown to her.

Whatever his genius evinced to the audience—and with Ophelia there is but little of the tender passion to be shown—Muriel knew that he was keeping his word to the letter, and, woman-like, she experienced just a little pique that it was so.

His courtesy was always the same, but whether they were alone or not, his manner showed no more warmth than was requisite for a close friend.

It had been a Monday when she first acted at the “Coliseum”; the week would be up on Tuesday.

Muriel grew white and embarrassed, dreading to meet his look, yet looking forward each day to the evening.

On the Saturday when the Carrolls came to fetch her, the novelist turned to Keene.

“Will you drive down to Windsor with us to-morrow? Roberts is coming, and Sir Randal and Lady Trevelyan.”

“I should have been delighted,” the actor said, cordially; “but I have to go down into the country—to see a friend who is ill. I have been wanting to go all the week, but Sunday is my only day, you see.”

And on Monday when Muriel arrived at the theatre, her dresser brought her a note from Keene.

“My dear child,—You will find an old friend in the green room, who is anxious to see you. Can you go now? You had better dress first, however.

“Yours, F. Keene.”

“Who can it be?” she said to herself, telling her dresser to be very quick.

And in ten minutes she was ready and hastening to the green room.

Keene was there, leaning over someone lying on a sofa.

He turned to greet her, and then Muriel gave a little cry and ran forward to kneel by the couch.

“You!” she said. “Oh! Mr. Leighton, this is so delightful. I never dared to hope that you would come to London.”

The picturesque-looking man, sadly worn and wasted physically, lying back on the cushions, gave a warm smile, and took her hands in his.

“When your letter reached me, child, telling of your success, I felt tempted to try to get to town; but—you know my weakness and dislike to being seen.”

“Yes,” she said softly, “I know; and,” with a quick flush, “Mr. Keene managed it, I am sure.”

“He found me out through you, child, of course. And yesterday, Francis,” to the actor who had left them alone, “I wonder if you realised what it was to me to see you? It was like old times—”

Keene came back and went round to the other side from Muriel, leaning forward and putting one hand caressingly on Leighton’s shoulder.

When he spoke, Muriel knew that he was putting stern control over himself, not letting the emotion he felt be detected by the swift, restless eyes that now and then lit up with all the fire and intellect of a great actor’s enthusiasm.

It was no light thing, the meeting of the two men, separated by nearly ten years’ absence.

They had parted with Leighton in the full zenith of his career, Keene the rising young actor of five-and-twenty, even then considered by old playgoers to be far in advance of all others.

The one had been cut down in the prime of his manhood, his life’s happiness seared by one of the basest treacheries ever perpetrated by a friend. His enthusiasm damped, his sensitive nature shrinking beneath the blow, he could not endure the former publicity that had attached to his lightest action, preferring to live in an obscure country town, away from the torment of the world’s pity.

“You have reached so high a pinnacle that the critics cannot influence, yet you will not disdain my congratulations, Francis. You were always greater far than I, and to your own power you add that of unrivalled management——”

Keene laughingly put his hand over the speaker’s mouth.

“Opinions differ, my dear Lyon. I would give a very great deal to have the old days revived. You worked wonders with your pupil here. I had little or nothing to add to your training, given at such disadvantage.”

“I should like to witness the performance to-night from the front, if it can be managed. Can you put me somewhere out of sight?” Fenton asked; “if not——”

“Your chair will be placed in the stage box,” Keene answered, softly; “no one shall bother you. Colin Carroll—you remember him?”

“The writer? Yes; a very amusing fellow.”

“He has married since you knew him—a charming little woman. I thought of asking them to take care of you; here they are.”

“And Mr. Gascoigne!” cried Muriel. “Mr. Keene, you are inimitable.”

“That is true,” laughed Fenton. “There is the call-boy, Francis.”

The Carrolls came up, and the invalid’s chair was wheeled to the stage box.

Mr. Gascoigne went off to his stall, for Keene would not run the risk of wearying Fenton by too many faces and conversation at first.

The performance went off more brilliantly than ever.

Muriel, conscious of the white, worn face watching hers and Keene’s every movement, listening to every word, and of her old friend straight in front of her in the stalls, was in a fever of excitement.

Her eyes flashed and sparkled; in the mad scene she surpassed herself, her voice filling every corner of the vast theatre like the chime of silver bells, low but clear.

Keene was superb, and the audience thundered such applause that he was bound to appear after each act again and again, Muriel also being called for with him.

“You will be a great actress, my dear,” Lyon Fenton said to her afterwards. “Although you have had every possible advantage in going on with Keene, still an educated audience would not tolerate mediocrity even under such auspices. You have sympathy, you are en rapport with your part and with the people, and you are very beautiful. Go on working hard—Keene will never let you rest; and he is the greatest man of the time. You like him?”

She coloured hotly under the swift, searching scrutiny.

“My dear, you will not be offended with me—”

She knelt down by the chair.

They were alone; and the tears trembled on her eyelids.

“You know that I can never repay a tenth part of your goodness to me,” she said, with deepest feeling. “All my life, Mr. Fenton, I shall pray that—even yet—you may be happy. Without your training I could have done nothing, and your introduction—”

“No, no. That was all overshadowed by your meeting with Keene in the train. He loved you at first sight—I know all about it, my child. And yet there is a cloud between you. He is very attractive to women—surely you are not insensible to his affection and admiration? Tell me what is the matter. I am old enough to be your father, and, moreover, I have one foot in the grave and the other hovering on the brink. I believe that you do care for him with all your strength,” he added, putting one hand on her arm, gently, and lifting her face.

“Yes,” she said, suddenly, “I do, Mr. Fenton. How could I help it? He was so kind, so thoughtful, so generous; and, when I found that he knew you so well, it was not like speaking to a stranger.”

“And so, sweetheart, you will not visit my father’s sin upon me? I hoped that Fenton would persuade you. Indeed,” laughing, and turning her face up to his, “I am strongly of opinion that he is first with you. I have got his promise that he will live with us; so that his last years will be happier than the past ten have been. And the child loves you. Are you pleased, my darling?”

She put her arms round his neck, and, for the first time, laid her mouth on his with a long passionate kiss.

If he had doubted the strength of her love before, he never did after that.

“You are perfect, Francis. Quite perfect,” she said, gravely. “If you do not commit something mortal I shall be afraid of you.”

NOTICE.—The next Complete Novelette Story, to be Given Away with No. 676 of “Something to Read” Journal, will be entitled:

AT THE ALTAR RAILS.

Printed by A. Bradley, at the London and County Works, Drury Lane, W.C.; and Published for the Proprietor, Edwin J. Brett, at 173, Fleet Street, E.C.—Feb. 13, 1894.

This story was published as a separate eight-page booklet distributed as a give-away with the journal Something to Read.

Obvious typographical errors have been silently corrected.

Illustrations have been moved nearer the appropriate points in the text.

Table of contents has been added and placed into the public domain by the transcriber.