By H. B. FYFE

Illustrated by SUMMERS

There were no courts on the isolated world.

But there was a Judge.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories March 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

At the roar of landing rockets, Quasmin's first impulse was to dash out to the hilltop to scan the skies.

When he left his shack, however, he did so cautiously, carrying a small telescope salvaged from the crack-up of his own ship. This planet was so far beyond the Terran sphere of exploration that he feared the new-comers might not be human.

He was surprised to sight the spaceship settling about half a mile away, in the vicinity of the wreck. The lines seemed to be Terran.

"They picked that spot on purpose," he muttered. "Couldn't be somebody after me, could it?"

There was no lack of good reason for the law to be after him. In the first place, the battered hull out there had not belonged to him. In the second, the authorities might be trying to find out what had become of the original crew. Quasmin could not answer that even if he wanted to—a corpse was difficult to locate in interstellar space.

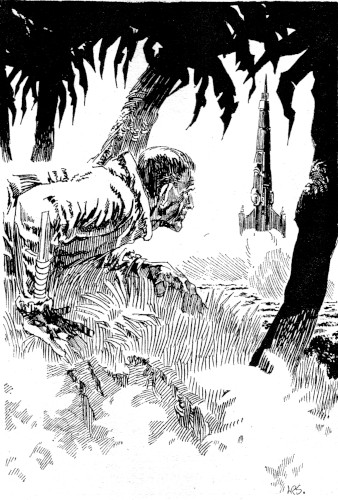

He took advantage of the cooling period after the ship had touched down to make his way through the scrubby growth that resembled a forest except for the purplish color of the drooping fronds. He found a good spy point on a low hill and settled down to watch.

In due time, the airlock within Quasmin's view opened. A single space-suited figure climbed clumsily down the ladder, paused to glance about, and walked a circuit of the ship as if to survey the terrain.

Apparently deciding that nothing dangerous flew or crept in the vicinity, the spacer returned to the base of the ladder to remove his suit. He dropped it there, hitched at his belt—suggesting to Quasmin the weight of a weapon—and began to stroll across the turf of springy creepers toward the wreck. Quasmin followed as sneakily as he could.

Passing the strange ship, some instinct told him that it was now unoccupied. The whole attitude of the spacer had suggested a man as much alone as Quasmin himself. The latter temporarily abandoned his skulking pace to walk boldly where he might be seen by any crew members on watch. No activity resulted.

Keeping one eye on the distant figure, Quasmin moved toward the spacesuit at the foot of the ladder. Just as he was about to reach out for it, the air took on the resiliency of sponge-covered springs and thrust his outstretched hand right back at him.

"Force shield!" he growled. "Damn! Probably set to his voice or some such code. Well, I can't get closer, but it proves he must be alone."

He squinted at the nametape on the breast of the spacesuit and read, "J. Trolla."

Then he hurried after the spacer, who was just disappearing behind a clump of shrubbery.

He could not decide later just when Trolla had in some fashion become aware of him. Quasmin could remember no careless move that might have given him away, nor did he think it likely that he was confronted by a practiced telepath. Such people existed, but they were not normally permitted to risk their unique talents flitting about the unexplored depths of interstellar space. Quasmin blamed it on natural animal instinct.

If he could have seen Trolla during the latter's inspection of the wrecked ship's interior, he would have worried even more. It was no idle poking about for possible salvage. The spacer spent over an hour examining those compartments accessible without the use of a torch to burn away crumpled metal and plastic bulkheads. He displayed unusual interest in things of obscure value, such as articles of clothing and empty plastic crates that had once held food supplies.

He also talked a good deal to himself in a low voice, but the battered hull concealed this from the man lurking outside.

That there was a watcher there, Trolla stopped doubting when he mentally summed up the amount of minor equipment obviously removed from the ship since the crash. He decided it was not necessary to penetrate the broken-up drive sections in what had been the lower levels before the hull had toppled over. The scavenging looked like the work of one individual unable to salvage any of the heavier machinery.

"Just took some things to make himself more comfortable," he murmured. "A few instruments, food, medicines, self-powered appliances, and the like."

He considered returning to his own ship for equipment with which to make a real check that would include search for and analysis of fingerprints, hair, perspiration traces ... and perhaps even blood samples.

"Why waste time?" he asked himself. "It has to be Quasmin, and there's not much chance of finding anyone with him. Why not just see where he's holed up—before he starts running again and makes it a long job?"

Emerging through a rent in the hull, he was again struck by the sensation of being watched. He could not control a slight motion of one hand to his belt for the reassuring touch of his gas gun. With it, he could fill the air around any attacker with a scattering of tiny, anesthetic pellets while the personal force shield he wore would protect him from any hostile return. Though assuming that Quasmin would be armed, he did not think the man could have obtained a shield. None had been reported missing by any law-enforcement agency within imaginable range of this untouched planet.

Trolla walked about the wreck twice before he spotted the dim trail that revealed infrequent visits to the place. Cautiously, he followed it along the edge of the taller, purplish growth that almost boasted the dimensions of trees, wondering if he would presently detect sounds of someone trailing him.

By the time he sighted the crude shack from a low hilltop, he believed he had heard sounds three or four times. They might have been indications of native life forms. He forgot about them as he examined the refuge that Quasmin had built.

The hut was crookedly assembled of bulkhead sections ripped from the wreck. There had evidently been batteries available to power simple tools, for lengths of bent plastic were bolted around the corners, and two windows had been cut in the walls. A mound of dirt had been heaped up against one of the sides.

"Digging in for the winter season," muttered Trolla, nodding. "Yes, he'll need some insulation."

He delayed looking inside, lest he provoke some reaction before learning all that he wished. Instead, he walked on past the shack, and thus came upon a small stream and an almost pitiful attempt at building a waterwheel.

"Must work, though," he told himself. "He must have been using it to recharge batteries for the distress calls he has the nerve to keep broadcasting. Wonder if he knows they don't have much effect over fifty billion miles?"

He crossed the brook and looked over the two small fields beyond. They had been cleared and roughly ploughed by some laborious means he preferred not to contemplate. It was standard procedure for spaceships to carry planting supplies for just such situations, and he had to approve the beginnings made by Quasmin. Retracing his steps to the shack, he found the opportunity to say so.

"Oh, there you are!" said Quasmin. "I was looking out near your ship to see who landed. Is there just you?"

Trolla savored the glint of animal cunning not quite disguised in the other's glance. He decided to quash the verbal sparring at the outset.

"How many did you expect, Quasmin?" he inquired pleasantly. "My department has to police three planetary systems, spread widely along this frontier. We can't afford fuel and rations to send a brass band after you!"

The shock was good for three or four minutes of bristling silence.

Twice, Quasmin opened his mouth as if to deny his identity, but thought better of it. His scowl faded into an expression of studied insolence.

"So you're a cop," he sneered. "What d'ya think ya gonna do, way out here where ya can hardly even call in to headquarters?"

"That depends," said Trolla, eyeing him analytically. "To be perfectly frank, I can't call headquarters. Don't you know how far out we are from the outmost little observation post of humanity? Or did you just give up all astrogation whenever you got rid of those crewmen you kidnapped?"

"How can you prove I got rid of them?" demanded Quasmin with the same sneer.

"I don't even want to bother. There are eleven murder charges hanging over you besides drug-smuggling and that rape on Vammu IV; and even I can hardly understand that last. Those people are only semi-humanoid!"

Quasmin grinned. Trolla felt vaguely sickened at the sudden realization that his momentary betrayal of a sense of decency was taken as a sign of timidity.

The other turned aside and took a few slow steps to where an empty plastic crate had been braced against a rock for a seat. He sat down and leaned his shoulders against the rock, but with an attitude of alertness. It was the first physical move made by either since Trolla had walked around the corner of the hut.

"Maybe ya think you'll arrest me," he said, watching Trolla carefully. "Maybe ya think I don't pack the same handful of sleep you do!"

"And a shield too?"

Quasmin's eyes narrowed at that. He seemed to estimate his chances of calling a bluff, then relaxed slightly, accepting the truth.

"Suppose we shoot it out, then," he suggested. "You might kill me at this range, with an overdose before the pellets scatter. Ya get too much gas in me, an' you'll be up for murder too."

"That would be your mistake," said Trolla.

"Oh, you might get off," said Quasmin judiciously. "But there lots of people will still say it's murder. You bein' a cop makes no difference. Civilization bein' what it is, the law's gotta protect me too! I gotta right to be helped more than average, because I'm in more than average trouble—right?"

Trolla nodded, but less in agreement than confirming some suspicion of his own.

"And you'd refuse to come with me even if I ordered you?"

"What a dummy ya'd be to try an' make me!" grunted Quasmin. "You gotta sleep sometime—an' you'd sure as hell wake up the wrong side of the airlock!"

He grinned at the other with his ugly expression of petty triumph and added, "Ya got nerve to try it after a fair warning?"

"Perhaps not," admitted Trolla.

"Huh! Ya got some sense after all. Why don't ya just go away an' let me alone? Nobody ever gave your bunch jurisdiction out here. I bet this planet was never even reported, was it?"

"It's not on record," Trolla confirmed. "As far as I know, the only humans to reach it are you and I—and I almost turned back. How you picked it up, I don't know, but I was playing a hunch when I picked up your distress call."

Quasmin leaned back in more relaxed fashion.

"Well, ya got a problem," he grinned. "I ain't leavin' here with ya, an' what chance have ya got of bringin' a judge an' jury out here? I gotta right to a fair trial with legal an' psychiatric advice!"

Trolla took two steps to lean his shoulder against a corner of the hut. The ill-constructed joint sagged under his weight.

"Didn't it occur to you that you're having your trial right now?" he asked.

That reached him, he thought, with a certain ironic satisfaction.

Quasmin glared at him in outraged disbelief. He spat on the ground and demanded, "What're ya doin'? Settin' yourself up as judge an' jury all by yourself?"

"And executioner, if need be," agreed Trolla.

He watched in silence as the other's jaw hung slackly, then as Quasmin slowly turned red with temper.

"You ... you ... why, ya dirty cop, ya! That's against every law that ever was. They ... they wouldn't let ya!"

"There's no other way. As you said, they can't send out people to hold a trial here. It isn't safe to take you back alone. They couldn't spare more officers to come with me on the off chance you'd be found way out here."

"No matter how far it is, you ain't got any right to do that!"

Quasmin's right hand was beneath his shirt but Trolla, secure within his shield, ignored that.

"Well, then," he said, "if mere distance doesn't put this planet beyond human law, the same goes for you."

"I still have a fair trial comin' then!"

"You're having it right now," Trolla told him.

"Like hell!" Quasmin snarled. He was on his feet now, teetering on his toes. "I know my rights. I oughta be gettin' rescue an' rehabilitation help. You can't do anything but kill me. You got no right!"

Trolla pushed off from the corner of the shack with a hunch of his shoulder. He took a few steps toward the trail out of the clearing, then hesitated.

"You've had a lot of rehabilitation work, haven't you?" he pointed out. "I had plenty of time to study your records, on the way out from Blauchen III."

"Ya can't talk me into comin' in for more psych treatments!" growled Quasmin. "I had enough of those guys, since I was a kid."

"Yes, you were a little too smart for them," agreed Trolla. "The most they ever managed was a good, thorough conditioning against suicide, after you put on a psycho act to break up the second trial for murder."

Quasmin grinned again.

"I sure suckered them that time," he recalled with gloating. "The treatment didn't hurt any 'cause I never did have any idea of killin' myself; an' it got me outa the other mess till I could make a break."

"It won't get you out of this one."

Quasmin's grin left him.

"Made up your mind already?" he demanded, half drawing a gas pistol of his own.

"Not yet," said Trolla. "I'll go back to my ship to think it over."

He walked away, though keeping a prudent watch over his shoulder until he was a hundred meters distant. Even after that, he turned around occasionally. This made it difficult for Quasmin to follow him, but the outlaw managed to be in position to observe Trolla's arrival at his ship.

He spied as the detective recovered his spacesuit and climbed the ladder to the airlock. When there appeared to be no likelihood of his emerging for some time, Quasmin scuttled back to his hut.

"No sense bein' here if he comes lookin' for me with his gun an' shield," he growled to himself. "Maybe I bluffed him, an' maybe I didn't."

He threw together a small bundle of rations and rolled it with a water bottle in a blanket. As he did so, he muttered a stream of curses.

"He's got no right to try anythin'," he reassured himself. "The law says I gotta have a chance at rehabilitation whether I co-operate or not. I didn't make up the law, but I can use it as much as he can. He wouldn't dare overgas me!"

His anger helped him start out at a brisk pace. In less than three hours, he reached an area of rough, cliff-broken hills where there were caves that would take Trolla weeks to check. There he concealed himself for the night.

Sometime during the darkness, a distant rumble awakened him.

Suspiciously, Quasmin poked his head out of the cave in which he had been sleeping. He was just in time to see the flare of rockets in the starry sky.

"He backed down!" was his triumphant conclusion.

He watched the flaring light until he was satisfied that Trolla was making for space and not for another landing place. Then he returned to sleep.

Just to be sure, Quasmin remained in the hills two more days, until his supplies ran low and he thought it might be comfortable to return to the hut. He made his way back warily, lest Trolla should have left some sort of trap.

At the shack, he found nothing but his own things, so he hiked through the purplish shrubbery to the landing spot. To his surprise, he discovered that Trolla had left a number of crates behind. He sat down to think that over.

When no explanation occurred to him, he went to the wreck of his own ship. In the partly stripped control room were a few instruments that still functioned when he hooked up batteries to power them.

"Might be smart to see if he's in orbit," he muttered. "Maybe he thinks he can soften me up by leaving presents."

Emerging an hour later, he looked puzzled. As much by luck as by skill and accuracy, he had succeeded in picking up Trolla's ship on the rangefinder. The instrument was not meant to operate efficiently through an atmosphere and Quasmin was no expert in its use; but it definitely showed Trolla was heading out-system.

"Well, then, I might as well see if he left a bomb," decided Quasmin.

He approached the crates close enough to read the stenciled labels. Scowling in bewilderment, he set about opening them. Just as the lettering indicated, he found an assortment of electric motors, equipment for building a new generator that could be powered by his waterwheel, and even a supply of glow-panels for light if he should get an electrical system into operation.

There was also a chest of tools and parts, and several boxes of grain and vegetable seeds. The prize of all was a small, three-wheeled, battery-powered vehicle that looked just large enough to pull a homemade plow.

The man sat on an open crate and burst into hysterical laughter.

"All a bluff!" he chortled. "I knew he didn't dare do anything!"

It was after he staggered to his feet to haul the little machine from its crate that he found Trolla's note attached to the handlebar.

Dear Quasmin, it said. As you tried to point out, there is some argument whether a society has any moral right to punish a criminal or merely an obligation to help him heal himself.

Quasmin roared with laughter. He looked up at the clear sky.

"That's right, Trolla! I'm sick—an' don't you forget it!"

On the other hand, he read on, an individual owes support to the society that protects his rights. I think a breach of the contract by one party nullifies it for the other too. Think that over—Trolla.

Quasmin scowled at the words, then at the sky, and finally at the tools and materials that would help maintain him on this strange planet for many years.

"Years and years and years," he muttered, glancing about at the hanging, purplish fronds in the silent background.

A stunned expression crept over his face, as he realized what kind of sentence had been passed upon him.

THE END