Title: Two young lumbermen

Subtitle: From Maine to Oregon for fortune

Author: Edward Stratemeyer

Illustrator: A. B. Shute

Release Date: August 17, 2023 [eBook #71427]

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Great American Industries Series

OR

FROM MAINE TO OREGON FOR FORTUNE

BY EDWARD STRATEMEYER

Author of "At the Fall of Montreal," "Young Explorers of the

Isthmus," "American Boy's Life of William McKinley,"

"Old Glory Series," "Between Boer and

Briton," "On to Pekin," etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY A. B. SHUTE

BOSTON

LEE AND SHEPARD

1903

Published, October, 1903

Copyright, 1903, by Lee and Shepard

All rights reserved

Norwood Press

Berwick & Smith

Norwood, Mass.

U. S. A.

"Two Young Lumbermen" is a complete story in itself, but forms the first volume of a line to be issued under the general title of "Great American Industries Series."

In beginning this series, I have in mind to acquaint our boys and young men with the main details of a number of industries which have become of prime importance, not alone to ourselves as a nation, but likewise to a large part of the world in general.

Our United States is a large country and consequently the industries are many, yet none is perhaps of greater importance than that of the lumber trade. Lumber gives us material for our buildings and our ships, our railroads and our telegraph lines, and furnishes the pulp from which millions of pounds of paper are made annually. We export lumber to Europe, to the West Indies, and even to the Orient, drawing on a forest treasure that covers thousands of square miles of territory.

The tale opens in Maine, which in years gone by was the paradise of the American lumberman. In those days pine was king, and Maine became known far and wide as the Pine Tree State. When the best of the pine had disappeared, spruce claimed the logger's attention; and then the lumberman looked elsewhere for his timber, first in Michigan and along the Great Lakes, and in the South, and then in California, and in that vast section of our country drained by the Columbia (or Oregon) River.

The two young lumbermen of this story are hardly heroes in the accepted sense of that term. They are bright youths of to-day, willing to work hard for what they get, but always on the alert to better their condition. As choppers, river-drivers, mill hands, and general camp workers they have a variety of adventures, but only such as fall to the lot of more than one lumberman working in the woods of Maine, Michigan, or Oregon to-day. It was in the Far West that they found their greatest opportunity for advancement, and how they made the most of that chance is described in the pages which follow.

In presenting this work the author desires once again to thank the many who have interested themselves in his previous books. May they find the reading of this volume even more interesting and profitable.

Edward Stratemeyer.

August 1, 1903.

"Do you mean to tell me that Hickley said he wouldn't send over that lot of logs I ordered last week?"

"That is what he said, Mr. Larson. He is short himself, and said he told you he thought he couldn't spare them. Not a drive has come down the river for three weeks."

"I know that, Bradford." John Larson, the owner of the Enterprise Lumber Mill, rubbed his chin thoughtfully. "It's hard luck. I guess I'll have to shut down after all. And I was calculating to keep you all working."

The face of Dale Bradford became as serious as that of his employer. "How soon will you close up the mill?" he asked after a pause.

"As soon as those logs over yonder are cut up." The owner of the sawmill kicked a block of wood out of his way rather savagely. "It's a shame not to get logs, with so much timber cut ready to use."

"The pulp mill is what's done it," replied Dale. "They have a big contract to fill, so I was told over in Oldtown, and so they are willing to pay big prices for any sort of stuff."

"You're right, Bradford. They'll buy little sticks that we couldn't afford to handle."

"What we've got on hand won't keep us going longer than Saturday," continued Dale, gazing around at the small pile of logs resting partly in and partly out of the stream upon which the sawmill was situated.

"Just about Saturday."

"And there's no telling when we'll be able to start up again, I suppose."

"Just as soon as I can get hold of the stuff to go ahead with. I don't like to have the mill idle any more than you or the others like to be out of work."

"I'll have to get something to do pretty quick," said Dale earnestly. "I can't live on nothing."

"You ought to have something saved."

"A fellow can't save much out of six dollars a week, Mr. Larson. Besides, I've been paying off that little debt my father left when he died."

"I see, I see," interposed the mill owner hastily. "You're a good sort of a lad, Dale—as good a lad as your father was a man. If we shut down on Saturday perhaps I can keep you on a week longer—cleaning up around the mill and along the river, and doing other odd jobs. That will give you more time in which to look for another opening."

The head sawyer of the mill now came up to question John Larson concerning the cutting up of certain large logs, and Dale moved away to resume his regular work, that of piling up the boards in the little yard adjoining the steamboat landing.

It was hard work, especially in this summer, noon-day sun, but Dale was used to it and did not complain. And this was a good thing, as nobody would have listened to his complaint, for all around that mill worked just as hard as he did. John Larson was a just man, but a strict one, and he required every man he employed to earn his salary.

Dale Bradford was an orphan, eighteen years of age, tall, muscular, healthy, and as sunburnt as outdoor life could make him. He was the only son of Joel Bradford, who in years gone by had owned a good-sized lumber tract on the west branch of the Penobscot River, in Maine, where this story opens.

When a small boy Dale had had two sisters, and his home with his parents, on the shore of Chesuncook Lake, had been a happy one. But the death of the two sisters and the mother had caused great grief to the father and the son, and it can truthfully be said that after these loved ones were laid away in the little cemetery among the pines, Joel Bradford was never the same. He lost interest in his lumber camp and in the spot that had been his home for so many years, and at the first opportunity he sold out and moved down to Bangor.

It was at Bangor that he fell in with several men who were interested in the gold and silver mines of the great West. One of these men induced him to invest nearly all his money in a mine said to be located in Oregon. The ground was purchased by Joel Bradford, and preparations were made to begin mining on a small scale, when word came that no gold or silver was to be found in that locality, and the scheme fell through, and the man who had induced Mr. Bradford to invest disappeared.

The money lost in this transaction amounted to six thousand dollars—nearly the whole of Joel Bradford's capital—and the former lumberman felt the blow keenly. He grew reckless and speculated in lumber in and around Bangor, and soon found himself in debt to the sum of five hundred dollars. This he paid all but a hundred dollars, when, during unusually severe weather on the river, he contracted pneumonia, from which he never recovered.

Dale was not yet seventeen years of age when he found himself utterly alone in the world, for this branch of the Bradford family had never been large and the grandparents had come to Maine from Connecticut years before. Dale had a fair common-school education, but most of his life had been spent at the lumber camps and along the river and the lakes with his father. He could fell a tree almost as well as a regular lumberman, and had followed more than one drive down the stream to the boom or the sawmill.

"I've got to buckle in and make a man of myself," was what he told himself after the first great grief over the loss of his father was over. "I can't afford to sit down and do nothing. I've got to support myself, and pay off that debt father left behind him."

He had been doing odd jobs for a lumber firm owning an interest in yards at Bangor and at Oldtown, twelve miles further up the Penobscot. But these did not pay very well, and he looked further, until he struck Larson's Run, a small settlement located on a tributary of the big river. Larson had known Joel Bradford well for years, and had purchased many a cut of logs from him.

"So your father is dead and you want a job," John Larson had said. "Well, I'll give you the best that I have open"; and then and there he had engaged Dale at a salary of four dollars per week, a sum which was afterwards raised to six dollars.

Dale secured board with a mill hand living near by, and as soon as he was settled he began a systematic reduction of the debt his father had left unpaid. He felt that this was a duty he owed to the memory of his parent and to the honor of the family at large.

"They shan't say that he swindled anybody," was the way he put it to himself. "I'll pay every dollar of it before I buy a thing for myself that isn't actually necessary."

In the bottom of his trunk at the boarding house Dale had the deed to the land in Oregon which his father had purchased—that unfortunate transaction that had practically beggared them. The young lumberman often read the papers over carefully. They showed that his father had been the sole owner of many acres of territory located in the heart of the great West. Of this great tract of land Dale was now the sole owner.

"And to think that the tract is only a rocky mountain side, good for nothing at all," he would say with a sigh. "Now, if it were only a stretch of farm land, I might go out and try my luck at farming some day. I guess it's only fit for a stone quarry,—same as the rocky lands here,—but nobody wants a quarry out there, a hundred miles or more from nowhere at all."

So far Dale had managed to pay up all but thirty dollars of the debt left behind by his parent. He might have paid this, but a log had rolled on his foot, causing him a bruise that had kept him from work for two weeks and given him a doctor's bill to pay in addition.

The thirty dollars was owing to a riverman named Hen McNair. The fellow was a Scotchman and exceedingly close-fisted, and he had bothered Dale a good deal, hoping to have his claim paid at once.

"You can pay up if you want to," said McNair in his Scotch accent. "If you've not the money sell off some of your things."

"I've sold off all I can spare," had been Dale's reply. "You'll have to wait. From next Saturday on I'll pay you two dollars a week."

"Hoot! 'Twill be fifteen weeks—nigh four months—before we come to the end."

"It's the very best I can do."

"Can't you pay me five or ten dollars now?"

"No. The most I can give you is two dollars."

"Then give me that. And see you keep your word about the balance." And stuffing the bill Dale handed him into his pocket, Hen McNair had gone off grumbling something about the want of honor in a lad who wouldn't pull himself together and pay his father's honest debts.

The sawmill owned by John Larson was run both by water power and by steam—the latter helping out the former when the flow of the stream was not at its best. Rain had been wanting for several weeks, and this had delayed a drive of logs the mill owner had counted on, and had also made it necessary to depend entirely on steam as a motive power. The plant employed twenty-four hands, and this and another mill on the opposite shore were the main industries of the Run.

"How did you make out about those logs, Dale?" questioned a fellow worker in the yard, as the young lumberman resumed his labors.

"Didn't get them," was the laconic answer.

"Didn't think you would," went on Philip Sommers. "Hickley is in with the pulp mill. If he can't get logs, what is the old man going to do?"

"He'll have to shut down."

"Phew! That's bad!"

"Yes, and the worst of it is there is no telling when we'll start up again."

"In that case I'm going to pack up and go up to the West Branch. A friend of mine is going to open up on a claim there about the first of October."

"That is a good while yet. I can't afford to be idle that long."

"What will you do?"

"I don't know yet—perhaps try the other mills."

"Better try the pulp mill—they've got the business just now. Folks must have paper even if they don't get boards," and Philip Sommers gave a short laugh.

"I don't think I'd care to work in a pulp mill," answered Dale. "I like a sawmill or else being out in a lumber camp. But I'd rather work in a pulp mill than be idle."

"The pulp mill over——Hullo, there goes the noon whistle!" Philip Sommers dropped the board he was carrying. "Aint got time to talk any more," he cried. "Going home for something to eat." And picking up his jacket from a lumber pile, he walked away, leaving Dale alone.

The hoarse whistle of the mill, proclaiming the noon hour, sounded out fully half a minute, and when it ceased the machinery in the mill also came to a stop, and men and boys poured forth to get their dinner. Some went to their homes, or to their boarding-places, while others, who lived at a distance and had brought their dinner with them, sought shady and cool spots along the bank of the stream.

Dale did not quit work instantly, as Philip Sommers had done. He, too, was carrying a board, and this he placed on a pile a hundred feet away, as originally intended. Then he straightened out the whole pile of boards, work that took another five minutes of his time.

"Hullo, Bradford, working overtime?" cried one of the mill hands, who had quit at the first sound of the whistle.

"Sure," answered Dale pleasantly.

"Of course the old man is going to pay you double wages for it."

"Guess he will—if I ask him."

"You won't get a cent. Better stop and make the job last."

"I'll stop, now I have finished," answered Dale, and walked away with a quiet smile.

Although neither Dale nor the other workman knew it, John Larson overheard the conversation.

"Young Bradford is a good one," he murmured. "Just as good as his father was before him. Hang such men as Felton, who are always looking at their watches or waiting for the whistle to blow."

It soon became noised around among the workmen that their employer had been unable to obtain the logs he had sent for, and that evening, after the mill had shut down, a number of them waited on John Larson and asked him about the prospects. He was frank and told them what he had told Dale.

"I expected to keep going all summer," he said. "But I can't do it, and after this week I'm afraid you'll have to look for other openings."

As a consequence of this talk several of the men that very evening rowed over to the mill opposite, while some went down to the mills on the Penobscot. A few obtained other situations and left John Larson's employ the next day, but the majority came back from their quests unsuccessful.

By Saturday noon the big circular saws had cut up the last of the logs, and two hours later the men at the shingle machine also stopped work. Then ensued several hours of sorting out and clearing up, and by five o'clock the hands of the Enterprise Lumber Mill were paid off and told that when they should be wanted again they would be notified.

Dale had been asked by John Larson to remain after the others, and he did so.

"I told you I'd keep you another week," said the mill owner. "There is not a great deal to do, and you can come around every morning at six o'clock and work until twelve, and then have the rest of the day in which to hunt up another job. On Saturday I'll pay you for a full week."

This was certainly very fair, and Dale thanked his employer heartily for his kindness. Yet the youth's heart was heavy, for he knew that finding another opening would not be easy.

"I'll tell you what to do, Dale," said Frank Martinson, the man with whom he boarded. "You try down to Crocker's and over to Odell's. Tell 'em I sent you. They'll give you a job if they have anything at all to do."

"All right, I will," answered the young lumberman.

Crocker's mill was located down on the Penobscot. It was a new place, filled with the latest of machinery, and employing over half a hundred hands. Dale visited it on Monday afternoon, going down on a small lumber raft that happened to be passing.

The din around this hive of industry was terrific, for Crocker turned out much lumber in the rough for a furniture company, and the buzzing and zipping went on constantly from morning till night. The mill itself was knee-deep in shavings and sawdust, a good portion of which was fed into the furnaces under the boilers for fuel.

"Sorry, young man, but I can't take you on," said the superintendent of the works. "Had an opening last week, but it is filled now. Come around in two or three weeks. If Frank Martinson recommends you I know you're all right." And thus poor Dale had his trip for nothing. It took him until midnight to get home, and he had to walk a good part of the distance.

But he was not one to give up easily, and two days later borrowed one of John Larson's horses and directly after dinner set off for the mill run by Peter Odell. This was up in the hills, on the edge of a small lake, a ride of thirteen miles.

The way was rough, but Dale did not mind this, and as he loved to ride on horseback, the journey proved pleasant enough. Once he stopped at a brook to let the horse drink and sprang down himself to quench his thirst and bathe his face and hands.

"This is like old times, when I used to be home with all the others," he thought. "Oh, how I wish those times could come back."

At last he came in sight of the mill, nestling among the trees bordering the little lake—a scene full of rural beauty. To his surprise all was quiet about the place.

"It can't be that Odell has shut down, too," he thought. "If that is so we ought to have heard of it before this."

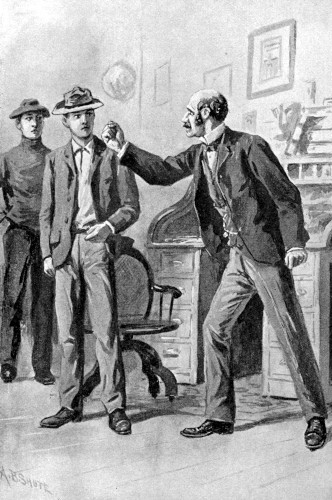

He was just turning into a side path leading to the mill when a man leaped out from behind a clump of trees and caught his animal by the bridle. The fellow was a French-Canadian, with a dark face and dark, evil-looking eyes.

"Hi! what do you mean by that?" demanded Dale. He did not like the looks of the stranger.

"You stop, talk wiz me," said the Canadian.

"What do you want?"

"You go to de mill, yes?"

"What if I am going to the mill?"

At this the French-Canadian muttered something in French which the young lumberman could not understand. "You look for job, hey? No job no more down by de Larson mill, hey?"

"That is none of your business. Let go of my horse."

Again the man muttered something in French. "You no go to de mill. Geet hurt sure. All mens dare on de strike. You go back." And now he shook his fist in Dale's face.

"Are you on a strike?"

"Yees."

"What are you striking about?"

"Dat none your bus'nees. You go back."

"I will not go back!" declared Dale, his temper rising. "If you don't let go of that horse pretty quick, somebody will get hurt."

"Hah! You are von big fool!" snarled the man, and clung to the animal as tightly as ever. The horse began to prance, and, watching his chance, Dale leaned forward and struck the French-Canadian a sharp blow in the forehead that caused him to stagger back in dismay.

"Good for you!" sang out a voice not far off, and looking in the direction Dale saw a young man of twenty approaching. The newcomer was a young lumberman like himself, and Dale had met him several times, on the river and elsewhere.

"Hullo, Owen," replied Dale. "Who is this chap?"

"That is Baptiste Ducrot, one of the mill hands up here," replied Owen Webb. "Odell hired him about a month ago, but I guess he wishes he hadn't, for the rascal drinks like a fish."

"He says there is a strike on at the mill."

"So there is, among the Canadians. They wanted me to join, but I wouldn't do it."

While this talk was in progress, Baptiste Ducrot recovered himself and glared first at Dale and then at Owen Webb. Evidently he did not fancy the coming of his fellow workman to the spot. Dale now smelt the liquor on Ducrot and noticed that his steps were far from steady. He urged his horse forward, and left the French-Canadian standing in the road shaking his fist savagely.

"That was a neat crack you gave him," observed Owen Webb, as he strode along beside Dale. "I guess he won't forgive you for it."

"He had no business to stop me, Owen."

"You're right there. What brought you up? I heard something of a shut-down at Larson's."

"Yes, we've shut down and I came up here to look for work."

"You came at a bad time—with some of the men on a strike."

"That's true." Dale's brow grew thoughtful. "Perhaps I had better go back, after all. I don't want to do some poor chap out of his job."

"They don't deserve work—half of them!" declared Owen. "The crowd that is out is the drinking gang. They want more money to waste on liquor. All the steady fellows are working the same as usual."

"Then I'll see Mr. Odell and chance it. Where can I find him?"

"He was in the mill a short while ago."

Owen had a mission up the lake and soon left Dale, and the latter dismounted and entered the mill, just as the machinery started up once more.

Mr. Odell was a burly old lumberman of sixty. He had spent all his life in the woods and few knew woodcraft or mill work better than he. He gazed at Dale sharply when he listened to what the young lumberman had to say.

"Well, I guess I can give you a job, seeing as how about half of my crew is gone," said Peter Odell. "But I can't guarantee it to last, for I'm 'most in the same fix as Larson. The pulp mills have knocked the sawmills endways up here."

"What about the strikers? I don't want to——"

"I haven't any strikers around here. Those fellows drank too much and I discharged them, that's all. I won't take 'em back—I'll lock up the mill first." And the mill owner's manner showed that he meant what he said.

It was arranged that Dale should come to work the following Monday, at the same rate of wages he was now receiving. He was to labor both in and out of the mill and was to board at the same house where Owen Webb was stopping. This latter arrangement suited him exactly, for he had taken quite a fancy to Owen, who, like himself, was alone in the world.

The summer day was drawing to a close when Dale started on his return to Larson's Run. He looked around to see if Baptiste Ducrot was at hand, but the fellow did not show himself.

"I hope he keeps out of sight," thought the young lumberman. "I don't want to have another quarrel with him."

The lake front was soon left behind and he plunged into the trail leading down the hillside. Under the trees it was quite dark, and he had to keep a tight rein on his horse for fear the animal might stumble and break a leg.

"I must return the horse in as good a condition as when I took him out," he told himself. "It wouldn't be fair to Mr. Larson if I didn't."

Soon he reached the brook where he had stopped to obtain a drink. Here he paused as before.

As he was bending to quench his thirst he heard a slight noise behind him. Then he received a violent push from the rear that sent him headlong into the stream. His head struck on the rocks at the bottom of the shallow watercourse, and for the time being he was partly stunned.

For several minutes Dale could think of nothing but that he was at the bottom of the brook and in danger of drowning. His head hurt, there was a strange ringing in his ears, and almost before he knew it he had gulped down a quantity of the cool water.

But "self-preservation is the first law of nature," and even though dazed he floundered around and tried to pull himself up out of the stream. Twice he slipped back. Then his hand fastened on a tree root and he stuck there, gasping for breath, spluttering, and trying to collect his senses.

"Who—who hit me?" he muttered at last.

When he felt strong enough to do so, he crawled up the bank of the stream and sank in a heap at the foot of a big tree. On one side of his forehead was a big lump, and on the other a small cut from which the blood was flowing.

"Just wait till I catch the fellow who did that," he told himself. "I'll square up with him."

His mind reverted to Baptiste Ducrot. Had the French-Canadian been the one to attack him? It was more than likely.

It was fully five minutes later when the young lumberman made another discovery. He was bathing the cut when, on glancing around, he noted that the horse he had been riding had disappeared.

"Hullo, Jerry is gone," he said to himself. "Jerry! Jerry! Where are you?" he called.

No sound came back in answer, nor did the animal put in an appearance. Staggering to his feet, Dale walked a short distance up and down the watercourse. It was useless; the horse could not be found.

With a sinking heart the young lumberman was retracing his steps to the ford when he saw a form on horseback advancing along the trail. As the person came closer he recognized Owen Webb.

"Owen!"

"Why, Dale, is that you?"

"Have you seen anything of my horse?"

"Your horse? No. Didn't you ride him back?"

"I rode him as far as here. Then somebody struck me and knocked me into the brook, and now the horse is gone," went on Dale.

He told the particulars of the occurrence so far as they were clear to him. Owen Webb was of a sympathetic nature, and as he listened his face grew clouded.

"It must have been Ducrot, Dale. It's just like the cowardly sneak. Didn't you see him at all?"

"No. I was attacked so quickly I didn't know a thing until I was trying to pull myself out of the water. If he took the horse where do you suppose he went to?"

"That's a conundrum. It's not likely he went on to Larson's Run, for the folks there would recognize the horse. And he didn't go back to Odell's, or I should have met him."

"I guess you are right, Owen. With the horse gone I don't know what to do."

"Let us make sure that he hasn't strayed away, Dale. Then, if you wish, you can ride behind me. That's better than walking the five miles."

Owen made a thorough search of the vicinity, while Dale again bathed his wound. No horse came to view, and a little later the journey to Larson's Run was resumed.

As said before, Owen Webb was a young man of twenty. He was alone in the world, and after the death of his parents had drifted from Portland to Bangor in search of employment. He had worked in several lumber yards and sawmills before hiring out to Peter Odell. He was a good workman and a clever fellow, and if he had any fault it was that of moving from one locality to another, "just for the change," as he expressed it. He generally spent his money as fast as he made it, but his want of capital never bothered him. Like Dale, he was no drinker, as are, unfortunately, so many lumbermen, and if his money went, it went legitimately, for good board and clothing, music and newspapers, and charity. Dale had liked him from the start, and the more the pair saw of each other the more intimate did they become.

Owen was bound for a blacksmith shop located near the Run, and at this place the two separated, and Dale continued his journey to John Larson's home on foot. He felt much worried over the loss of Jerry, but resolved to make a clean breast of the matter and did so.

John Larson was a good reader of character and saw that the young lumberman was telling him the strict truth. "It must have been that Ducrot who took the horse," he said. "I know him and never liked him. Why Odell hired him is a mystery to me. I'll send out an alarm and I guess I'll get the horse back sooner or later."

"And if you don't, Mr. Larson, I'll do what I can to pay for him," said Dale.

His last week at the Run soon came to an end, and Monday morning found Dale located at Odell's, and as hard at work as ever. In the meantime Peter Odell had refused again to treat with the men who called themselves strikers, and one by one they left the locality, taking their belongings with them.

The going away of these men left a vacancy at the boarding place where Owen was stopping, and this room was taken by Dale, so the two young lumbermen saw more of each other than ever. Owen was a fair performer on the violin and the banjo, and Dale could play a harmonica and sing, and they often spent an evening over their music, which the other boarders listened to with keen relish, for amusements in that out-of-the-way spot were not numerous.

For several weeks nothing out of the ordinary occurred. Dale worked hard, early and late, and for this Peter Odell gave him something extra to do, with extra pay. By this means the young lumberman was enabled to save more than usual, and one Saturday afternoon he had the satisfaction of sending Hen McNair a letter containing Peter Odell's check for the balance due the close-fisted riverman.

"That wipes out the last of my father's debts," said Dale to Owen. "I can tell you it makes me feel like a different person to have everything paid."

"I believe you, Dale. My father didn't leave any debts, but I had to square up for the funeral, and that was no small sum."

"Now all I have left to do is to square up for the horse that was stolen."

"What was he worth?"

"I don't know exactly. I asked Mr. Larson, but he said to wait a while, that Jerry might turn up somewhere."

So far the only word received concerning Baptiste Ducrot was through an old riverman, who had once seen the French-Canadian in a drinking resort near the upper end of Moosehead Lake. What had become of Ducrot after that nobody knew.

The summer was drawing to an end, and still the sawmill at Larson's Run remained idle. It was impossible to get logs, and soon Peter Odell began to complain.

"I shouldn't be surprised if we had to shut down too," said Owen one day. "If we do, Dale, what are you going to do?"

"I'm sure I don't know. This is certainly a hard year in the lumber trade."

"I don't believe it is as hard elsewhere as it is in Maine. My uncle, Jack Hoover, who owns a lumber camp out in Michigan, wrote that he was as busy as ever. He said I might come on if I couldn't find anything to do here."

"Why don't you go?"

Owen drew down the corners of his mouth into a peculiar pucker.

"You wouldn't ask that if you knew my Uncle Jack," he said.

"Anything wrong?"

"Uncle Jack is a worker—morning, noon, and night, and between times. He never knows when to stop, and he expects everybody around him to work just as hard or harder. Fact is, he's a regular slave driver. And in addition to that he's as close-fisted as Hen McNair."

"In that case, I don't wonder you don't want to engage with him," said Dale, with a laugh.

"Uncle Jack means well, but he never knows when to let up. I've heard my mother say that more than once. He was her step-brother. He started as a poor man, and when he went to Michigan he had less than a thousand dollars. Now he must be worth thirty or forty thousand, and maybe more."

"I don't believe you'll be worth that, Owen; not if you have to save it yourself."

"I don't want to be rich if I've got to slave like Uncle Jack. Money isn't everything in this world."

"But you ought to save something. Supposing you got sick, or something else happened to you?"

"Well, I'm going to start to save a little, some time."

"The best time to start is now. Some time generally means no time. You can put away as much as I put away, if you try."

"All right, I'll do it—next week."

"No, this week," and Dale smiled good-humoredly.

"Gracious, Dale! are you becoming my guardian?"

"Not at all, Owen. But I want to see you begin."

"I can't spare the money this week. I've got to have some new strings for the banjo, and hair for the fiddle bow, and have these boots mended, and pay my board, and buy some shirts, and——"

"Not all this week. That fiddle bow will last a week or two yet, and so will your shirts. Now here is this cigar box I've been using for a bank. I cleaned it out paying off Hen McNair, but I am going to start a new account. When I put in a dollar you put in a dollar, and when you put in a dollar I'll do the same. Then, when we want our money, we can whack up."

"How much are you putting in to start on?"

"Two dollars."

Owen gave something like a groan.

"All right, if I must, I must," he said, bringing out his week's wages. "But it's worse than having a tooth pulled."

"It won't be after you get in the habit of it."

"I don't believe I could get in the habit of having my teeth pulled."

"You know what I mean. After a while it will become just as easy to save money as to spend it—that is, a fair proportion of what you earn."

"Want me to become as close as my Uncle Jack?"

"I guess there is small danger of that." Dale reached for his harmonica, which rested on a shelf. "Now strike up on the fiddle, and then you'll forget all about the hardships of saving."

This was a sure way of pleasing Owen, and soon he had the violin from its peg on the wall and was tuning up. Then the pair began to play, one familiar tune after another, and thus the evening ended pleasantly enough.

The shut-down at Odell's came sooner than anticipated. The mill owner had been almost positive about another consignment of logs, but at the last minute one of the pulp mills drove up the price on the timber and the logs went elsewhere.

"It's no use," said Peter Odell, to his men. "I've got to shut down until next spring. During the winter I'll make cast-iron contracts for the next supply of timber, so there won't be any further trip-ups, pulp mills or no pulp mills. It's going to cost me money to quit, but, as you can see, I'm helpless in the matter."

To this the men said but little. A few of them felt that Odell was to blame just as John Larson was to blame—because he had not made "cast-iron" contracts before. But these mill owners were of the old-fashioned sort, easy-going and willing to take matters largely as they came.

"The pulp mills have the upper hand of the business," said Owen to Dale. "They'll take anything that is cut down, and that gives them the advantage. Now it wouldn't pay Odell, or Larson either, to handle logs less than fourteen inches in diameter."

"But the loggers are foolish to cut small stuff," answered Dale. "They don't give the trees a chance to grow, and before long there won't be a tree left to cut."

"The most of 'em think only of the money to be had right now; not what they might get later on. If I had my way I'd pass a law making it a crime to cut down small trees."

There were but few other sawmills in that vicinity, and each of these was working only three-quarters or half time. Water being low, power was scarce, and the general condition was certainly disheartening.

The two young lumbermen spent an entire week in seeking other employment, but without success. The only place offered was one to Owen at a pulp mill, tending a row of vats, but the pay was so small he declined it.

"I hate a pulp mill anyhow," he declared. "Now that winter is coming on, I'd rather try my luck up the river at one of the big camps."

"Exactly my idea!" cried Dale. "Say the word, and I'll start with you Monday morning. I'm sure we can find something to do up on the West Branch, or along one of the lakes."

"The trouble is, how are we to get up on the West Branch?" came from Owen. "I haven't any desire to tramp the distance."

"We can take the railroad train up to the lake," answered Dale, after a moment's thought. "I know Phil Bailey, who runs on the night freight. He'll give us a lift that far, I am sure. After we get to the lake we can try for a job on one of the boats going up the river."

This was satisfactory to Owen, and the pair made preparations to leave Odell's on Monday at noon. In the meantime Dale penned a letter to John Larson, stating that he had not forgotten about the missing horse, and, if the animal did not turn up, he would some day settle for him.

"It's the best that I can do," he said. "He was worth at least one hundred and fifty dollars, and it will take me a good long while to save up that amount."

The nearest railroad station on the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad was a small place called Hemway. Here a passenger train stopped twice a day and a mixed freight did the same. Phil Bailey lived at Hemway, so it was not difficult for Dale to find the brakeman.

"Yes, I'll take you along," said Bailey, "and glad to give you a lift. Carsons is sick, so I'm in charge this week. I'll look for you at the freight switch when the train comes along."

As a consequence that night found Dale and Owen housed in the caboose of the freight train, bumping along at the rate of twenty miles an hour in the direction of the lake. It was not very comfortable riding, and the stops and delays were frequent, but as Owen said, "it beat walking all hollow," and as it cost them nothing they were well content.

"I don't know that this beating the railroad out of a fare is just right," observed Dale, as they rode along. "But I guess such a corporation won't miss our few dollars."

"They'll make the summer tourists foot the bill," said Owen, with a grin. "Did you notice how crowded the train going south was?"

"I did. The cold snap last week is causing them to scatter. In a few weeks more they'll be flying home fast, and leaving everything to us lumbermen."

"And to the hunters."

It was early in the morning and still dark when the lake was reached. Thanking Phil Bailey for his kindness they crawled from the caboose just before the freight switch was gained and made their way down to one of the lumber yards along the shore. Here they found a comfortable corner in a shanty and slept until daybreak.

Lakeport, as the settlement was called, was divided into two parts, the bluff, where the fine cottages and the Lake View Hotel were located, and the lower end, where were situated several lumber yards and a number of lumbermen's cabins and two general stores.

Down at the lumber yards everything was quiet, for the booms from the former winter's cuttings had long since been distributed to the mills far below, and scarcely anything would be received until the spring "yarding" began. Only a few men were around, and the majority of these were either preparing to go up into the timber to work or else to act as guides and cooks to the sportsmen who would soon put in an appearance for a winter's hunt after moose and other game.

Each of the young lumbermen wore the typical costume of the woodsmen of that locality, so neither attracted special attention when they walked into one of the general stores. The wife of the storekeeper took boarders and she readily consented to serve them with breakfast and as many other meals as they wanted and were willing to pay for. The ride had made them tremendously hungry and they ate all that was set before them with keen relish.

"Going up among the loggers, eh?" said the storekeeper, when they were settling their bill. "Well, I reckon as how it's going to be a mighty good year—logs is wanted the wust way, not only fer the sawmills an' pulp mills, but also fer export."

"Right you are, Sanson," put in another man who was present. "I heard from a deputy surveyor at Bangor that we cut over 150,000,000 feet o' pine and spruce last year and they expect to cut even more this year. Twelve million feet was exported to England—an' we got a rousin' good price fer it, too."

"Yes, but times aint as good as they was," came from the storekeeper. "1899 was the banner year fer lumber here. The cut was 183,000,000 feet, an' not only thet, but spruce thet had been sellin' fer $14 and $18 a thousand sold down to Boston fer $20 and $24. Times aint what they was." And the storekeeper heaved a long sigh.

At the side door of the general store a clerk was loading a wagon with various provisions, beans, potatoes, salt fish, flour, a sack of coffee, and the like. Dale watched him for a few seconds and then accosted him.

"Loading up for one of the hotels?" he questioned pleasantly.

"No, this load is going up the river," was the answer.

"May I ask who is going to take it and where it is bound?"

"It's going up to the Paxton camp. Old Joel Winthrop and a couple of other men are going to take it up. Paxton is going to start in early this fall, so we're rushing the stuff up to him."

"How many hands does he employ?"

"About a hundred or more. Want a job?"

"Want a job, eh?"

"Yes."

"Then you'd better see Winthrop about it. He's looking for likely men."

"Where can I find him?"

"Down to the lake. He's got a bateau he calls the Lily—name is daubed on the stern. You can't miss him."

"Thanks; we'll try him," answered Dale, and set off, followed by Owen.

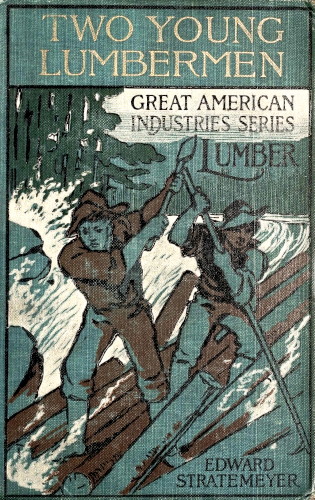

It was not a difficult task to locate Joel Winthrop, an aged woodsman, with whitish hair and beard, and shrewd gray eyes. He had been patching up a leak in his clumsy craft, and he listened to Dale's application while holding a pitch pot in one hand and a brush in the other.

"Want a job, eh?" he said, looking them over. "What can you do?"

"Almost anything but cook," answered Owen. "Might do that, but I shouldn't care to risk it."

"Guess you wouldn't—not up to our camp," laughed Joel Winthrop. "Had a cook last year who burnt the beans an' they tuk him down to the river, chopped a hole in the ice, an' soused him under three times. He never burnt a bean after thet, so long as he stayed."

"We'd like to go as choppers or swampers," said Dale. A chopper is one who fells trees, while a swamper is one who cuts down brushwood and makes a road from the forest to where the logs are piled for shipment in the spring.

"An' what wages are you expectin'?"

"Regular wages," said Dale boldly. "We expect to do regular men's work."

"Got a recommend?"

"Several of them," and Dale handed over the letters he had received from Larson, Odell, and his other employers. Owen also exhibited several recommendations he possessed.

"I see ye don't drink," said Joel Winthrop. "Glad to hear o' that. Drink is the curse of a lumber camp, you know that well as I do. The question is, can ye both stand the work fer a whole season?"

"If we can't you'll not have to keep us," answered Owen.

"Ours is a mighty cold camp, I can tell ye that."

"We are used to roughing it," said Dale. "I was brought up that way from a baby."

"We aint payin' young fellows like you more'n twenty dollars a month an' found."

"How many months work?" asked Owen.

"Six months, an' maybe seven or eight."

"I'll accept," said Owen.

"So will I," said Dale.

The old lumberman then said he knew John Larson fairly well and that a recommendation from such a person must be all right.

"We're going to start up the lake this afternoon," said he. "So if ye mean business be on hand at two o'clock sharp. I'll give ye free passage, an' you help work the boat and carry stuff around the falls."

By this time the provisions from the store were arriving, and both set to work to assist Joel Winthrop in stowing them away. Then, having nothing else to do, the two young lumbermen strolled around the settlement, past the big hotel and back by way of the freight yard.

As they were passing the latter place, the down freight came in, stopped to take on two cars piled with lumber, and then started on its way again. As it moved off a man ran from the freight yard and leaped on board of the last car.

"Well, I declare!" gasped Dale. "Did you see that fellow?"

"Who?" questioned Owen, with interest.

"The fellow who jumped on the last car." Dale pointed to the fast-vanishing figure. "As sure as I stand here it was Baptiste Ducrot!"

Owen was as amazed as Dale to think that the man who had leaped on the disappearing freight train was the French-Canadian who had caused the latter so much trouble.

"Well, he's gone," said he, after a moment's pause. "It's a pity you didn't spot him before the train started."

"He didn't show himself, Owen." Dale drew a long breath. "Do you know what I think? I think he was hanging around this town, when he saw us and made up his mind that he had better get out."

They made a number of inquiries and soon learned that Ducrot had been in Lakeport two days. He had applied to Joel Winthrop and several other lumbermen for a position, but had smelt so strongly of liquor that nobody had cared to engage him. From general indications all the lumbermen doubted if the fellow had much money in his possession.

"I'll wager he sold the horse and drank up the best part of the proceeds," said Dale. "It's a rank shame, too! I'll have to save a long time to square up with Mr. Larson. I'd give a week's wages if I could have Ducrot arrested."

"You might telegraph to the next station, Dale."

"So I might!" Dale's face brightened a little, then fell again. "But I guess I won't. It will cost extra money, and I'll have to go and identify him, and stay around when he is tried, and all that. No, I'll watch my chance to catch him some time when it is more convenient."

Promptly at the time appointed by old Joel Winthrop the journey up the lake was begun. Counting Dale and Owen there were five lumbermen on the Lily, which was a craft ten feet wide by about twenty feet long. The Lily was to be towed along by a small tug which did all sorts of odd jobs around the lake. The bateau was piled high with the provisions and with the boxes and valises belonging to the lumbermen, not forgetting the case that contained Owen's precious violin and the green bag with the banjo.

"I see you're a player," said Joel Winthrop. "I used to scratch a fiddle myself years ago. You'll have to give us some music goin' up." And Owen did, much to the satisfaction of all on board.

The distance to the Paxton lumber camp was over a hundred and fifteen miles, and it took five days to cover the journey. At the end of the lake the goods had to be portaged up to the river, and then had to be portaged around the falls beyond. On the West Branch and the side stream on which the camp was located the bateau had to be poled along, and owing to the low water often caught on the mud or the rocks. But nobody minded the work, and as the weather was cool and dry the journey passed off pleasantly enough.

The two strange lumbermen were from Bangor and were named Gilroy and Andrews. They were experienced hands, and Gilroy was an under boss at the camp, having charge of the North-Section Gang, as it was called. All the older men loved to talk about lumbering in general and old times in Maine in particular, and Dale and Owen listened to the conversation with interest.

"Got to go putty far back for lumber now," said Joel Winthrop. "All the good stuff nigh to the river has been cut away."

"I've heard my grandfather tell of the times when they cut good logs less than ten miles from Bangor," put in Gilroy. "I reckon they didn't think what an industry lumbering would become in these days."

"I suppose they cut nothing but pine in those days," said Dale.

"Nothing but pine, lad; spruce wasn't looked at."

"Yes, and pine was the great thing even up to the Civil War," said Joel Winthrop. "But that was the last of it, and a couple of years after the war ended spruce came to the front, and now, as you perhaps know, we cut five times as much spruce as we do anything else."

"I've often wondered how many men worked in Maine at lumbering," said Owen. "There must be a small army of us, all told."

"I heard that last year more than fourteen thousand men were in the woods," came from Andrews. "The total number of feet of all kinds of lumber cut was over half a billion."

"What a stack of logs!" cried Dale.

"No wonder we have a pine tree on the coat of arms of the State," added Owen. "But it ought to be a spruce tree now instead of a pine," he continued.

"I can remember the day when the lumber camps claimed the very best of our people," said Joel Winthrop. "Folks wasn't stuck up in them days, and many of the richest men in Bangor and Portland earned their first dollar choppin' down pine trees. But now we've got all sorts in the camps, an' have to take 'em or git nobody. Not but what we've got good men at our camp," he added hastily.

"I wouldn't mind a job as a lumber surveyor," said Dale. "They get good wages, don't they?"

"A deputy surveyor gets ten cents a thousand on all the lumber he checks off," answered Gilroy. "I've known a man to make six to ten dollars a day at it. The fellows who overhaul the lumber for him get seven and a half cents a thousand each. The surveyor-general of the county gets a cent a thousand on all lumber passed on in the county."

"Some day I reckon I'll be a surveyor-general," observed Owen dryly.

"I'd rather own a rich lumber tract," returned Dale. "I'd work it systematically, cutting nothing but big trees and planting a new tree for every old one cut. By that means I'd make the tract bring me in a regular income."

"That's the way to talk," came from Joel Winthrop. "And unless the owners do something like that putty soon Maine won't be in the lumber business no more."

"They tell me that the big pulp mill near here can use up 50,000,000 feet of lumber in a year," went on Dale.

"It's true," said Gilroy. "They'll chew up logs almost as fast as you can raft 'em along. What we are coming to if the pulp mills and paper makers keep on crowding us for logs, I don't know."

It was night when they reached the landing place nearest to the Paxton camp, which was located up the hillside, half a mile away. At this point the stream opened up into something of a pond, with a cove in which several small boats were moored.

The shores of the pond were rocky and covered in spots with a stunted undergrowth, while further back was the forest of spruce, pine, fir, and a few other trees, sending forth a delicious fragrance that was as invigorating as it was delightful. As the bateau grounded, Dale leaped ashore, stretched himself and took a long, deep breath, filling his lungs to their utmost capacity.

"This is what I like!" he cried. "It's better than a tonic or any other medicine."

"And what an appetite it will give a fellow," added Owen. "I can always eat like a horse when I'm in the woods working."

As it was a clear night, the bateau was hauled up on the shore and the provisions carefully covered with a thick tarpaulin. Then the party struck out up the hillside for the camp, Joel Winthrop leading the way.

The trail was a rough one, for this camp was new, being located nearly a mile from the one of the season before, the loggers moving from place to place according to the cutting to be done. More than once they had to climb over the rough rocks with care, and once Owen slipped into a hollow and gave his leg a twist that was far from agreeable. The ground lay thick with needles, cones, and dead leaves, and here and there a fallen tree brought down by storm or old age.

The young lumbermen had already been informed that the camp was a new one, so they were not surprised when they learned that so far only a cook's shanty had been erected and that the men assembled were sleeping in little shacks and tents or in the open. When they arrived they found but two men awake, the others having retired almost immediately after supper.

Joel Winthrop had his own shack, a primitive affair, made by leaning a number of poles against a rocky cliff eight or ten feet high. Over the poles were placed a number of pine boughs, and boughs were also placed on the floor of the structure, for bedding purposes.

"Come right in and make yourselves at home," he said cheerily, after lighting a camp lantern and hanging it on a notch of one of the poles. "Nothing more to do to-night, so we might as well go to sleep."

"The boys can sleep with you; I'll stay outside where I can get the fresh air," said Gilroy, and wrapping himself in a blanket he went to rest at the foot of a neighboring tree, with Andrews beside him.

A youth not used to roughing it might have found the flooring of the shack rather a hard bed. But Dale and Owen thought nothing of this. The last day on the river had been a busy one, and soon each was in the land of dreams, neither of them being disturbed in the slightest by the loud snoring around them—for lumbermen in camp do snore, and that most outrageously—why, nobody can tell, excepting it may be as a warning to wild beasts to keep away!

The next morning the sun came up as brightly as ever. Long before that time the camp was astir, and from the cook's shanty floated the aroma of broiled mackerel, fried potatoes, and coffee.

"That smells like home!" exclaimed Owen and started for a spring near by, where there was a small tub, in which the men washed, one after another.

A table of rough deal boards had been erected under the trees, with a long bench on either side. There was no tablecloth, but the table was as clean as water and soap could make it. Each man was provided with a tin cup, a tin plate, a knife, a fork, and a spoon, and each was served his portion by the cook or the cook's assistant. If the man wanted more he usually rapped on his empty cup or plate until he was supplied.

The cook was a burly negro named Jeff, his full name being Jefferson Jackson. Jeff was usually good-natured, but when the men hurried him too much for their victuals he would often growl back at them.

"Fo' de lan' sake!" he would bellow. "Say, can't you gib dis chile no chance 'tall? Yo' lobsters dun got no bottom to yo' stummicks. T'ink I'se heah to fill up de hull ob de 'Nobscot Ribber? Yo' dun eat like yo' been starvin' all summah."

"Jeff wants to turn us into skeletons," cried one of the young lumbermen, winking at the others. "He's got a contract to furnish a Boston museum with 'em."

"Skellertons, am it?" exploded Jeff. "Wot yo' is gwine to do is to hire out to 'em fer a fat man—if yo' kin git filled up yere. But Mastah Paxton aint raisin' no fat men fo' no museums 'round dis camp, so yo' jest dun hole yo' hosses till I gits 'round dar a fo'th time."

And then the men would have to wait, until each had had his fill, when he would scramble from his seat with scant ceremony and prepare for the day's work.

Before the morning meal was over Dale and Owen became acquainted with ten or a dozen of the lumbermen, all rough-and-ready fellows, but above the average of the lumber camps in manner and speech.

"I'm glad we didn't strike a tough crowd," said Dale, remembering a lumber camp he had once visited, in which drinking was in evidence all day long and the talk was filled with profanity.

"So am I," answered Owen. "But I knew this camp was O. K. from the way Winthrop talked."

Luke Paxton, the owner of the camp, was away, but he came in during the forenoon and had a talk with each of the new hands. He was of a similar turn to Winthrop, and asked Dale and Owen a number of short questions, all of which they answered promptly.

"I guess I knew your father," he said to Owen. "I used to have an interest in a lumber yard in Portland. He was a good man." And then he turned away to give directions for putting up two additional shanties in the camp and a log cabin, which would become the general home of the lumbermen when cold weather set in.

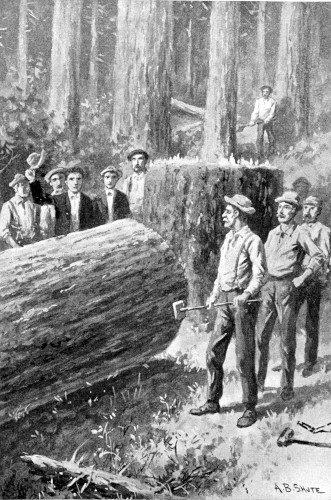

That afternoon found Dale and Owen at work close to the camp, helping to cut the timbers for the new cabin. Joel Winthrop watched them as each brought down the first tree. "That's all right," he said, and then gave them directions for continuing their labors.

The men in the camp were divided into gangs of twenty to thirty persons, consisting of choppers or fellers, swampers, drivers or haulers, and a boss who watched the work, picking out the trees to be cut and directing just how they should be made to fall, so that they could be gotten away with the least trouble. Later in the season there would be sled drivers and tenders, or loaders, and also a man to bring out the midday meal when the gang was too far into the woods to come to camp to eat.

The building of the big cabin was no mean task, and it took one gang three weeks to do it. It was built of rough logs, notched and set together at the ends. There was a heavy ridge-pole, with a sloping roof of logs on either side, and the floor was also of logs, slightly smoothed on the upper side.

When the cabin proper was complete it was divided into two parts, each containing a window, and one a door in addition. One end was the sleeping room, with bunks built of rough boards, each bunk four feet wide and twelve feet long. Each bottom bunk had another over it, and each was meant for four sleepers, a pair at each end, with feet all together. The bunks had clean pine boughs in them, and a pair of regular camp blankets for each occupant.

The second apartment was that devoted to eating and general living purposes. The door was close to the cook's shanty, but when the weather grew colder the big cooking stove would be placed directly in the middle of the living room, to add its warmth to the comfort of the place. The stove was of course a wood burner, a square affair capable of taking in a log a yard long. For a dining table the deal table from outside was brought in, with its benches, and half a dozen empty provision boxes were also brought in for extra seats. To keep out the cold the cracks of the entire building were stuffed with mud, and on the inside certain parts were covered with heavy roofing paper and strips of bark.

"Now we are ready for cold weather," said Owen, when the cabin was finished and the most of the men of their gang had moved in. He and Dale had a small corner bunk which held but two, and in this they were "as snug as a bug in a rug," as the younger of the lumbermen declared.

The last of the choppers had now arrived, and it was found necessary to put up another cabin for them. Dale and Owen, however, did not work on this, but instead spent every day in the depths of the great forest, bringing down one tree after another, as Gilroy, who now had charge of the gang, directed. Each of the young lumbermen proved that he could swing an ax with the best of the workers, and Gilroy pronounced himself satisfied with all they did.

"It only shows what a young fellow can do when he's put to it," said the foreman one day to Owen. "Now, half these chaps are merely working for their wages and their grub. They do as little as they can for their money, and the minute the season is over they'll go down to Oldtown or Bangor, or some other city, and blow in every dollar they have earned."

"But this camp is better than lots of others."

"Yes, I know that. It's because old Winthrop and Mr. Paxton sort out the men they engage. They won't take every tramp who strikes them for a job."

The men often worked in sets of fours, and when this happened Dale and Owen's usual companions were Andrews and a short, stout French-Canadian named Jean Colette. Colette was good-natured to the last degree and full of fun in the bargain.

"Vat is de use to cry ven de t'ing go wrong," he would say. "My fadder he say you mus' laugh at eferyt'ing, oui! I laugh an' I no geet seek, neffair! I like de people to laugh, an' sing, an' dance. Dat ees best, oui!"

"You're right on that score," said Owen. "But some folks would rather grumble than laugh any day."

"Dat is de truf. Bon! You play de feedle, de banyo; he play de mout' harmonee an' sing, an' yo' are happy, oui? I like dat. No bad man sing an' play, neffair!" And the little man bobbed his head vigorously.

"What a difference between a man like Colette and that Ducrot!" said Dale to Owen, later on. "Yet they come from the same place in Canada, so I've heard."

"Well, there are good men and bad in every town in Maine," answered Owen sagely. "Locality has nothing to do with it."

The fact that Dale and Owen could play and sing was a source of pleasure to many in the camp, and the pair were often asked to "tune up," as the lumbermen expressed it. There was also another violin player at hand, and many of the men could sing, in their rough, unconventional way, so amusement was not lacking during the cold winter evenings. More than once the men would get up a dance, jigs and reels being the favorite numbers, with a genuine break-down from Jeff, the cook, that no one could match.

Winter came on early, as it usually does in this section of our country, and by the end of October the snow lay deep among the trees of the forest, while the pond and the river presented a surface of unbroken ice, swept clear in spots by the wind. For many days the wind howled and tore through the tall trees, and banked up the snow on one side of the cabin to the roof. The thermometer went down rapidly, and everybody was glad enough to hug the stove when not working.

"This winter is going to be a corker, mark my words," observed Owen.

"I know that," answered Dale. "I found a squirrel's nest yesterday and it was simply loaded with nuts. That squirrel was laying up for a long spell of cold."

Yet the lumbermen did not dress as warmly when working as one might suppose. A heavy woolen shirt, heavy trousers, strong boots, and a thick cap was the simple outfit of more than one, and even Dale and Owen rarely wore their coats.

"Swinging an ax warms me, no matter how low the glass is," said Owen. "And I haven't got to pile any liquor in me either."

Often, while deep in the woods, the two young lumbermen would catch sight of a wolf or a fox, attracted to the neighborhood by the smell of the camp cooking. But though the beasts were hungry they knew enough to keep their distance.

"But I don't like them so close to me," said Owen. "After this I'm going to take my gun to work with me," and he did, and Dale took with him a double-barrelled pistol left to him by his father. Some of the others also went armed, and one man brought in a small deer from up the river, which gave all hands on the following Sunday a dinner of venison—quite a relief from the rather wearisome pork and beans, or corned beef, cabbage, and onions.

"To bring down a deer would just suit me," said Dale.

"Just wait, your chance may come yet," answered Owen, but he never dreamed of what was really in store for them.

It was a bitter-cold day in November that found the pair working on something of a ridge, where stood a dozen or more pines of extra-large growth. Each worked at a tree by himself, while Andrews and Jean Colette were some distance away, working in the spruces.

"Hark!" cried Dale presently. "Did you hear that?"

"It was a gun shot, wasn't it?" questioned Owen, as he stopped chopping.

"Yes. There goes another shot. Do you suppose one of the men are after another deer?"

"Either that, or else there are some hunters on the mountain. If they are hunters I hope they don't shoot this way."

"So do I, Owen. Only last year a hunter up here took one of the choppers for a wild animal and put a ball through his shoulder."

"If they shoot this way and I see them I'll give 'em a piece of my mind. They ought to be careful. A fellow——Hark!"

Both listened and from a distance made out a strange crashing through the underbrush of the forest. Then came a thud and more crashing.

"It's a wild animal, coming this way!" sang out Dale. "Better get your gun."

"Perhaps it's a bear!" ejaculated Owen, and lost no time in dropping his ax and picking up his gun.

The crashing now ceased for a moment, and the only sound that reached their ears was the moaning of the wind through the treetops far overhead. The wind was blowing up the hillside, so that the wild beast, if such it really was, could not scent them.

Another shot rang out, from the same direction as the first. This appeared to rouse up whatever was in the wood, and the crashing was resumed with increasing vigor.

"It's coming, whatever it is!" sang out Dale, and pointed out the direction with his hand.

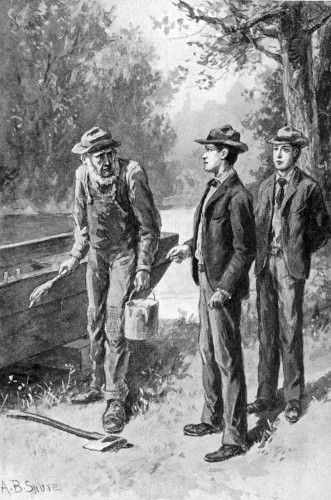

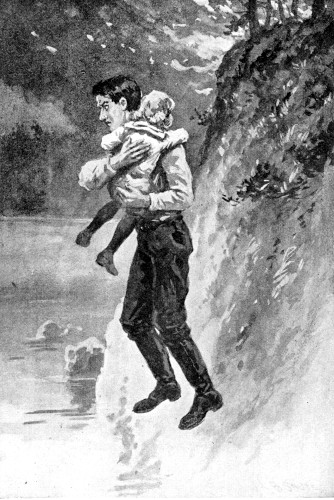

Hardly had the words left his lips when the underbrush and snow beyond the ridge were pushed aside and into the opening staggered a magnificent moose, with wide-spreading antlers and wild, terror-struck eyes. The game limped because of a wound in the left flank, and there was another wound in the side, from which the blood was flowing freely.

"A moose!" shouted Owen, and raising his gun he took hasty aim and fired at the beast.

Now, although Owen was a good woodsman, he was only a fair shot, and the charge in the gun merely grazed the moose's back. It caused the animal to give an added snort of pain. It stopped short for an instant, then its eyes lighted on Dale, and with another snort it leaped forward with lowered antlers directly for the young lumberman!

It leaped forward with lowered antlers directly for the young lumberman.

Bang! went Dale's pistol, and the bullet struck the moose in the forehead. But the rush of the animal was not lessened, and in a twinkling the youth was struck and hurled over the ridge into the gully below, and the moose disappeared after him!

The attack by this monarch of the Maine forest had been so sudden that Dale had no time in which to leap out of the way or do anything further to defend himself. Down he went, into a mass of rough rocks and brushwood, and the moose came almost on top of him.

With bated breath, Owen saw youth and beast disappear. His heart leaped into his throat, for he felt that his chum must surely be killed. Then he gave a yell that speedily brought Andrews and Colette to the scene.

"What is it?" demanded Andrews.

"A wounded moose! He just knocked Dale over the bluff."

"Ees he killed?" screamed Colette.

"I hope not. Come, help me."

Owen had now recovered somewhat from his first scare and he picked up his ax. Running to the edge of the ridge he looked over, and saw the moose as the beast struggled to get up on the top of the rocks below.

In the meantime Dale was not idle. Fortunately his fall was not a serious one, for he landed in a mass of thick brushwood, thus saving himself one or more broken bones. From this point he slipped into a hollow and the next instant felt the side of the moose pressing him on the shoulder.

The animal was suffering from loss of blood, and its efforts to regain its feet were wild and ineffectual. The sharp hoofs worked convulsively and one, catching Dale on the shoulder, cut a gash several inches long. Then the moose rolled in one direction, and the young lumberman lost no time in rolling in another.

It was at this point in the conflict that Owen came down to Dale's assistance, leaping from the bluff above, ax in hand. After him came Andrews and Colette, the latter armed with both his ax and an old French fowling-piece.

"Hit him, Owen!" panted Dale. "Hit him in the head!"

"I will—if I can," was the answer, and Owen advanced swiftly but cautiously.

"Stop! I shoot heem!" screamed Jean Colette, and raised his fowling-piece. Bang! went the weapon, and the moose received a dose of bird-shot in his left flank, something which caused him to kick and struggle worse than ever.

Owen now saw his opportunity, and, bending forward, he dealt the moose a swift blow on the shoulder. The beast struck back, but Owen leaped aside, and then the ax came down with renewed force. This time it hit the moose directly between the eyes. There was a cracking of bone and then a convulsive shudder. To make sure of his work, the young lumberman struck out once more, and then the game lay still.

"Yo—you've finished him," said Dale, after a pause.

"Yes, he's dead," put in Andrews, as he gave the game a crack with his own ax, "for luck," as he put it.

"Vat a magnificent creature!" exclaimed Colette. "Bon! Ve vill haf de fine dinnair now, oui?" And his eyes twinkled in anticipation.

"Did he hurt you?" asked Owen, turning from the game to his chum.

"He gave me a pretty bad dig with his hoof," was the reply. "I guess I'll have to have that bound up before I do anything else. He came kind of sudden, didn't he?"

"Those hunters up the mountain drove him down here. I suppose they'll be after him soon."

"Doesn't he belong to us, Owen? You killed him."

"That's a question. They wounded him pretty badly—otherwise he would never have stumbled this way."

"I'd claim the game," came from Andrews. "Somebody wounded him, it's true, but they would never have gotten the moose."

Leaving Andrews and Colette to watch the game, Dale, accompanied by Owen, walked back to camp, where he had his wound washed and dressed. The cut was a clean one, for which the young lumberman was thankful. Some salve was put on it; and in the course of a couple of weeks the spot was almost as well as ever.

The shots had been heard by a number of the other lumbermen, and a dozen gathered around and walked to the gully to look at the moose. It was certainly a fine creature, with a noble pair of antlers.

"If nobody comes to claim that carcass you've got somethin' worth having," was old Winthrop's comment. "But some hunter will be along soon, don't ye worry."

Yet, strange to say, no one came to put in a claim, and a few hours later the moose was placed on a drag and taken to camp. All the men had a grand feast on the meat, and the antlers and pelt were sold at a fair price to a trader who happened to come that way. The total amount was put into the cigar box by Owen.

"For it belongs to Dale as much as myself," said Owen. Jean Colette claimed nothing, for he knew that his bird-shot had had little effect on the moose.

Dale was afraid that he would run behind the others in work because of his wound. But such was not the case, for the day after the encounter at the ridge it began to snow and blow at a furious rate, so that none of the loggers could go out. The time was spent mostly indoors or at the stables where the ten horses belonging to the camp were kept. The men were never very idle, for they had their own mending to do and often their own washing. The days, too, were short, and the majority of the hands retired to their bunks as soon as it grew dark.

"This weather will bring out the sleds," observed Owen. "I guess Mr. Paxton will give orders to carry logs as soon as it clears off."

The camp boasted of four long, low double-runner sleds. These were driven by two Canadians and two Scotchmen, all expert at getting a load of logs over the uneven ground without spilling them. The horses were intelligent animals, used to logging, and would haul with all their might and main when required.

Owen was right; the sleds were brought out on the first clear day, and while the majority of the men continued to cut logs, some were set to work to make a road down to the pond and others were set at the task of loading the logs ready for transportation.

Dale had already put in a week or two at swamping, and now he and Andrews were detailed to fix a bit of the road that ran around a hilltop overlooking the stream far below. Near this spot was a long sweep of fairly even ground, sloping gradually toward the watercourse, and Joel Winthrop had an idea that many logs could be rolled to the bottom without the trouble of loading and chaining them on the sleds.

"Such a method will certainly save a lot of trouble," said Andrews, as he went out with Dale. "But the men below want to stand from under when the logs come down."

The storm had given way to sunshine that made all the trees and bushes glisten as if burnished with silver. From the hilltop an expanse of country, many miles in extent, could be surveyed—a prospect that never grew tiresome to Dale, for he was a true lover of nature, even though occupied in destroying a part of her primeval beauty.

"Just think of the days when this country was full of Indians," he said to Andrews. "It's not so very many years ago."

"Right you are; times change very quickly. Why, the first sawmill wasn't built on the Penobscot until 1818, and in those days Bangor was only a small town and many of the other places weren't even dreamed of. The Indians had their own way in the backwoods, and they used to do lots of trading with the white folks when they felt like it."

"Yes, and fought the white folks when they didn't feel like it," laughed Dale. "But then the red men weren't treated just right either," he added soberly.

"I can remember the time when these woods were simply alive with game of all sorts," went on the older lumberman. "If you wanted a deer all you had to do was to lay low for him down by his drinking place. But now to get anything is by no means easy. That moose you and Webb got is a haul not to be duplicated."

The work at the hilltop progressed slowly, but at the end of two weeks all the small trees and brushwood in the vicinity were cut down and disposed of, and then a road to the edge of the hill was leveled off and packed down.

In the meantime one of the sleds had been at work among the trees cut down just back of the edge, and these trees were now piled up in several heaps.

"We'll try some of the logs this afternoon," said Gilroy, one Friday morning, and the trial was made directly after dinner. Four logs were pushed over the edge, one directly after the other, and down they went, with a speed that increased rapidly and sent the loose snow flying in all directions. At the bottom they struck several trees left standing for that purpose and came to a stop with thuds that could be heard a long distance off.

"Hurrah! That beats sledding all to pieces!" cried Dale. "We can roll down a hundred logs while a sled is taking down a dozen."

"We can roll down all we have up here to-morrow," said Gilroy. "And the sled can go to the cut below. The biggest logs are in the hollow and it will take every team we have to get 'em out."

Yarding had already begun at the edge of the pond, and Saturday found Owen at work among a number of small trees and thick brushwood which Mr. Paxton had ordered cut away, for the head lumberman loved to see everything around his camp in what he termed "apple-pie order." This is nothing unusual among the better class of lumbermen in Maine, and they often vie with each other as to which camp presents the best appearance and whose cut of logs foots up the cleanest.

Among the logs at the hilltop was a giant tree, left standing for many years and now cut for a special purpose by old Joel Winthrop himself. A friend of his, an old sea captain, was building a schooner at Belfast, and Winthrop had promised him a mast that should stand any strain put on it.

"Aint no better stick nor thet in the whole State o' Maine," said Joel Winthrop to Andrews and Dale. "An' I want ye to be careful how ye roll it down the hill." And they promised to be as careful as they could.

It was no easy task to get the big log just where they wanted it, and it was Monday afternoon before they were ready to let it start on its short but swift journey to the edge of the pond. During the day the sky had clouded over and now it looked snowy once more.

"I guess we are ready to bid her good-by," observed Dale, as he looked the log over and measured the snowy slope with his eye.

"All ready!" sang out Andrews. "Now then, up with your stick and let her drive!"

Each was using a long pole as a lever, and each now pressed down. This started the log toward the edge, and in a second the stick began to slide downward, slowly at first and then faster and faster.

"Hullo! hullo!" sang out a voice from far below. "Don't send any more logs down just yet!"

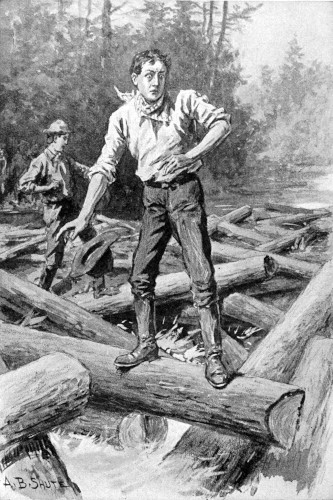

"It's Owen calling!" gasped Dale, his face growing suddenly white. "Owen, where are you?"

"There he is!" came from Andrews, holding up his hands in horror. "There, right in the way of that log!" He raised his voice into a shriek. "Run for your life! Run, or you'll be smashed into a jelly!"

Owen heard the shriek, and although he did not understand the exact words uttered, he realized that it was meant for a warning.

He was about fifty feet up the side of the hill, ax in hand, preparing to cut down a bunch of saplings which, so far, had not been touched. The saplings had been knocked over by the other logs sent down, but the young lumberman thought it would be better if they were out of the way altogether.

Standing on something of a knob he looked up and saw the log coming down upon him, rolling and sliding with ever-increasing rapidity. That it was coming directly for him there could be no question, and for the moment his heart seemed to stop beating and a great cold chill crept up and down his backbone, while he had a mental vision of being crushed into a shapeless mass by that ponderous weight.

"Jump!" screamed Dale. "Jump, for the love of Heaven, Owen!"

"Jump! Don't wait! Jump!" yelled Owen.

And then Owen jumped, far from the knob to the portion of the slide below him. It was a flying leap of over a rod, and when he landed he struck partly on his feet and partly on his left hand. Then from this crouched-up position he took another leap, very much as might a huge frog, and landing this time on his side, rolled over and over to the bottom of the slide.

The log was following swiftly and the swish of the flying snow and ice reached his ears plainly. It had scraped a bit at the knob, placing a fraction of a second of time in his favor. But now it came on, bound for the bank of the pond, straight for the young lumberman, as before!

It is said that in moments of extreme peril persons will sometimes do by instinct that which they might not have done at all had they stopped to reason the matter out. So it was with Owen in the present case.