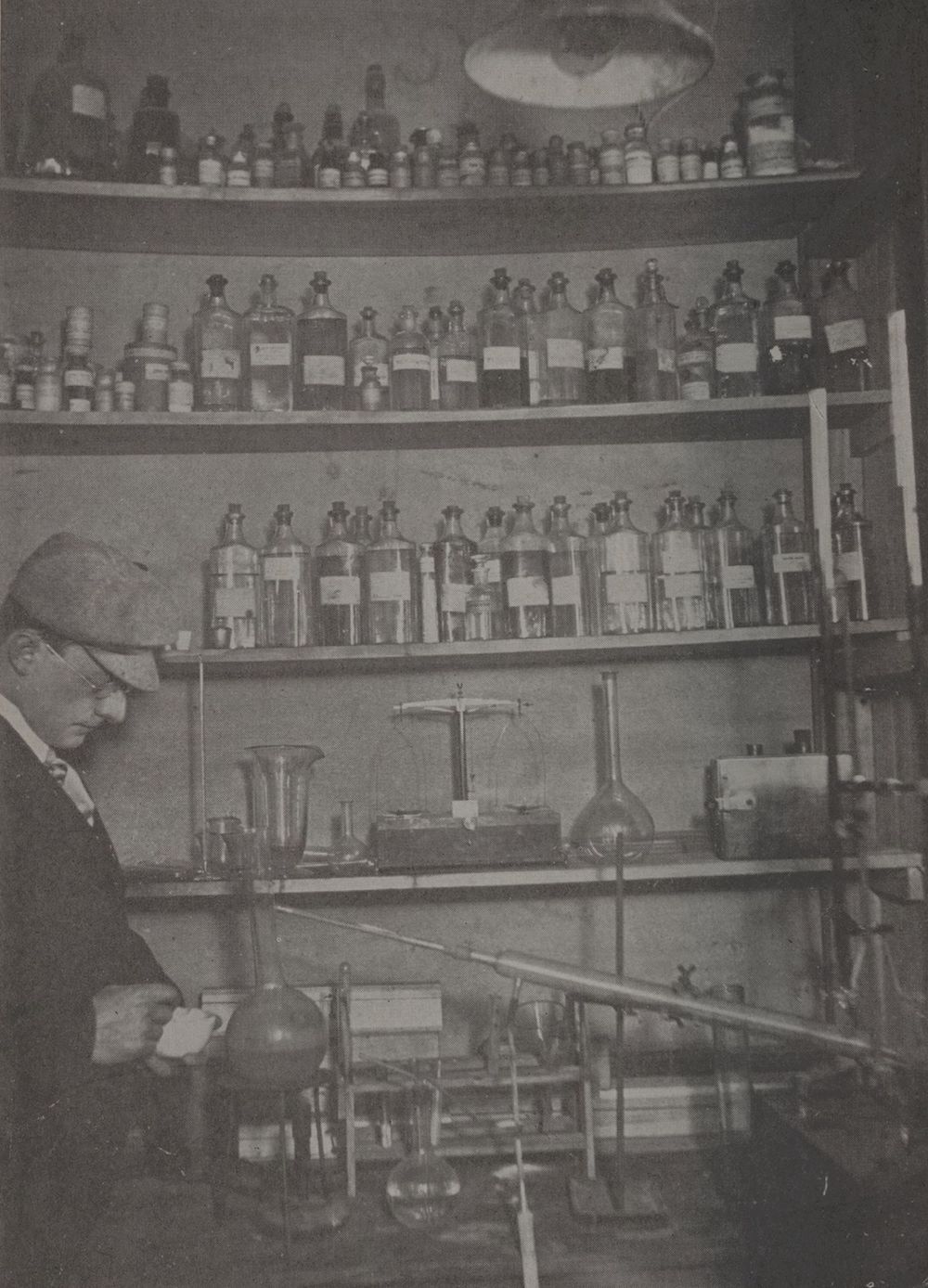

MODERN GLUE-TESTING LABORATORY

(Courtesy of A. T. Deinzer, Monroe, Mich.)

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The glue book, by J. A. Taggart

Title: The glue book

How to select, prepare and use glue

Author: J. A. Taggart

Release Date: April 10, 2023 [eBook #70517]

Language: English

Produced by: deaurider, Lukas Bystricky and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[Pg 1]

THE GLUE BOOK

[Pg 4]

[Pg 5]

HOW TO SELECT

PREPARE AND

USE GLUE

A SHORT, PRACTICAL

DISCUSSION OF MATTERS

IMPORTANT TO EVERY

GLUE USER

J. A. TAGGART, TOLEDO, O.

[Pg 6]

[Pg 7]

The purpose of this manual is to provide a practical guide for glue users, to help in eliminating waste and improving the quality of product.

That there is an enormous waste due to improper preparation and use of glue is well known to all who are in touch with the subject.

Some authorities estimate that 70% of the glue used in the United States is improperly handled. The actual waste is said to be in excess of 25% of the amount of glue used; to say nothing of the loss due to imperfect condition of the completed work.

The writer knows from actual experience that many glue users are ignorant of the proper methods to be employed; and that many others are careless, or indifferent.

[Pg 8]

The handling of glue is a subject on which much new light has been shed in recent years. There is no longer any reason why the glue user should not know the correct methods to follow.

This treatise is intended as a handbook for the glue user who is interested in increasing the efficiency of his operations.

Technical expressions have been avoided, the whole matter being set forth as much as possible in the everyday terms in familiar use in the glue-room.

So far as the author can learn, from an extended investigation, no book has been published on this subject exactly answering the needs of the average glue user. Several excellent works are available which would be interesting to a man technically trained in the subject; but although they embody many helpful suggestions, they are not in such form[Pg 9] as to be of the greatest value to the practical man. No pretense is made for the present manual of disclosing new facts; but rather of assembling in handy and easy reference form a summary of the best modern practice which the glue user of today may rely upon as a safe and convenient guide.

[Pg 11]

| CHAPTER I | |

| IMPORTANCE OF THE INDUSTRY | |

| Glue industry founded in America by Peter Cooper — increase in capital invested — increase in production — variety of uses — increase in requirements | Page 15 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| THE MANUFACTURE OF GLUE | |

| Sources from which glue is made — boiling the stock — drying — preparation in commercial form | Page 17 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| TESTING AND GRADING GLUE | |

| Grades established by Peter Cooper — the tests — viscosity or fluidity test — the jelly test — apparatus for making jelly test — the finger test — a simple, practical test for glue users — sampling — bubbles — surface indications — color indications — alkaline or acid quality — breaking quality — foam — grease — keeping properties — odor — laboratory test | Page 25 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| CORRECT METHODS IN THE GLUE-ROOM | |

| Much waste through faulty methods — importance of correct practice — soak glue in cold water before melting — test glue by[Pg 12] water absorption — appliance for water absorption test — melting or dissolving glue — do not heat higher than 150° F. — apply heat indirectly — live steam ruins glue — use thermometer — heat glue slowly — cleaning the melting pot — importance of using copper, brass or aluminum utensils — guard against evaporation — melt only the amount required — importance of cleanliness — keeping the glue-room warm — use by weight — storing — applying glue — securing workers’ co-operation | Page 43 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| MODERN GLUE-ROOM EQUIPMENT | |

| Modern appliances now available for all users — only copper, brass or aluminum should come in contact with glue — the scientific glue-heater — the automatic temperature controller — keep steam away from glue — glue spreaders — clamps and presses — distributing glue in large plants | Page 65 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| WHICH GLUE TO USE | |

| Accurate records important — the best glue for wood joints — veneers — sizing — paper boxes — belting and other leather goods — bookbinding — emery purposes — how much to pay — waterproof glue — vegetable glue — quick-setting glue — flexible glue | Page 79 |

[Pg 13]

[Pg 15]

Glue is now so extensively used, and for so many different purposes, that it certainly deserves much more intelligent treatment at the hands of users than it has received heretofore.

Since 1837, in which year Peter Cooper, who may justly be regarded as the founder of the glue-making industry in the United States, produced the first American-made glue, the yearly output has steadily increased.

By 1880, the amount of capital invested in the making of glue had reached $4,000,000. In 1905, it was $10,000,000, and is now between $12,000,000 and $13,000,000.

The annual production has increased in about the same ratio. In 1880, it was $4,000,000; at present it is about $15,000,000.

[Pg 16]

Glue is an important by-product of the great packing houses. Those in touch with the industry know how extensively glue enters into the manufacture of articles of everyday use. The general public hardly realizes that glue is used not only in making wood-joints and veneers, but in the production of paper, of silks, hats, carpets, rugs, and hundreds of other necessities.

America now produces glue of excellent quality to meet practically all requirements. So great are the requirements that almost the entire amount of the American-made glue is absorbed by the home demand.

[Pg 17]

An understanding of the sources from which glue is derived and of the processes of manufacture will be found of practical importance to the glue user. It will give many valuable side-lights on the proper methods of preparation and handling.

Glue is an organic substance of adhesive properties obtained from the hides, skins, bones and sinews of cattle, sheep, deer, horses, and other animals. Tails, snouts, ears, and the pith of the horn are also used. Some glue is produced from the heads, bones and sinews of fish.

The tendons and intestines of many animals, the swimming bladder of many varieties of fish; rabbit skins, or “coney,” from which the fur has been removed; old waste leather, such as gloves, butchers’ offal, or “country bone;” “junk” bones, and much other apparently worthless matter, all contribute to the raw material[Pg 18] of the glue-maker. In its broadest sense glue may be understood to include gelatine, but the use of the word is here confined to the substance known commercially as glue, and which in contrast with gelatine has greater adhesiveness, stiffness, and elasticity, and is also darker in color and more nearly opaque.

Neither gelatine nor glue exists already formed in nature; they are both the products of the action of heat and water on nitrogenous animal tissue. It is not definitely known just how this change takes place. Some writers regard glue as impure gelatine; others believe that there is a difference in nature between gelatine and glue. This question is without present importance for our purpose.

Glue is produced by boiling the animal substances mentioned above, and drying the resulting liquor.

[Pg 19]

The following may be noted in connection with the use of skins. The outer covering, in which the wool, fur or hair is rooted, is of no importance to the glue-maker. The portion that produces the glue lies next to it, being composed of fibres which run in every direction and contain the fluid matter which aids in keeping the skin moist and pliable. The fat cells are directly beneath the glue-yielding portion, and as fat is undesirable, because it makes the glue greasy, the shreds of fat are saponified by being subjected to a lime bath. The lime bath is also useful in removing any hair still adhering; and is used also in preparing tissue, to remove bloody and fleshy particles.

This part of the process may consume from one to three days.

It may be noted in passing that the older the animal, the more solid the glue will be. On this account many manufacturers sort the skins before using.

[Pg 20]

Being animal stock, the raw material of glue is subject to decomposition, and the scraps of hide are therefore carefully preserved, especially during the summer season.

The tanneries supply most of the hide stock, but only waste pieces reach the glue manufacturer, as leather is more valuable than glue, and the larger portion is therefore reserved for the tanner’s use. Various names are used to describe the parts of hide that the tanner discards for the glue-maker’s use—the heavy trimmings are “pieces;” the hide pared off the hair or grain side, “skivings;” the parts scraped from the flesh side are “fleshings.”

At the packing houses the heads, feet, ribs, and other bony structures go direct to the glue-room. If bone is sweet and fresh it is known as “green,” or “packer” bone. The waste of button and knife factories is also used.

[Pg 21]

Bones are usually ground, and they are treated with a sulphuric acid bath to attack and separate the lime and gelatine of which the bone is composed. Bones, after being treated in this way, become pliable and soft, and the sulphuric acid is then removed by centrifugal force.

The acid must all be removed, as the glue will granulate if any remains.

Other parts of the stock are always carefully washed before boiling.

After the stock has been prepared, it is placed in a boiler with false bottom provided with an opening through which the liquid may be run off. The boiling of the stock is an operation that must be carefully conducted, as the application of a greater degree of heat, or for a longer time than is necessary, damages the glue.

The boiler is heated by direct firing. As the boiling proceeds, test quantities of the liquid are run off for examination, and when a sample is found on cooling to form a stiff jelly, it is ready to draw off.[Pg 22] The first boiling usually occupies about eight hours. When the liquid has been run off from this boiling, more water is added and the boiling is continued. This operation is repeated until the stock has yielded all of its gelatinous matter. As many as six or eight boilings may be made.

The liquid first run off—the “first boiling”—is always best, as the effect of repeated or prolonged application of heat is to weaken the glue tissue. The later boilings are also as a rule darker in color than the earlier ones.

The glue-solution from the boiling process is run into wooden troughs or “coolers,” about 6 feet long, 2 feet broad, and a foot deep, in which the solution sets in a firm jelly.

When set, a little water is run over the surface, the jelly is detached from the cooler, cut into uniform slices of the thickness desired, and placed on galvanized or linen nets to dry.

[Pg 23]

Drying may be done in the open air if weather conditions are favorable, or in a drying-room. The latter method is preferable. Conditions can be regulated to insure uniform drying.

Piles of the nets, or “stacks,” are loaded on trucks and taken into the drying-room, where they are exposed to the effect of warm air currents induced by blower or pressure fans, or exhaust or suction fans.

The drying is a source of concern to the manufacturer. It is extremely important to keep the temperature at just the right point, to protect the glue from dust and dirt, and to avoid the possibility of bacterial growth in the glue-jelly, which is very susceptible to the development of harmful organisms.

The final form of the glue will be in sheets, strips or flakes, or ground. For commercial purposes it is put up in packages, bags and barrels.

[Pg 25]

There is as yet no uniformity of opinion among glue manufacturers and glue users as to how glue should be tested and graded. In a general way the manufacturer knows what kind of glue a certain stock will produce; but on account of variations that are sure to occur, it is necessary to subject each glue to certain tests, according to standards more or less definitely established.

The grades in general use are those originally employed by Peter Cooper, and are as follows:

A EXTRA

No. 1

1 x

1¼, 1⅜, 1½, 1⅝, 1¾, 1⅞

The only way to determine which is the best glue to use, is by trying out various grades in actual practice. The[Pg 26] best glues for ordinary uses are well understood (see pages 79 to 85 for suggestions on this subject). Between two or more glues of any one type, actual experiment is the only safe guide. Most glue men will give you good advice; but above all, keep accurate records of results of the different grades used. When you have found the right glue, keep to it.

Glue is graded on physical characteristics rather than on chemical composition. Various chemical tests have been proposed, but they are unimportant so far as practical working value is concerned.

The most important physical tests are those for viscosity, and jelly strength.

The test for viscosity, or fluidity, is based on the idea that the greater the tenacity of the glue, the greater will be[Pg 27] its cohesiveness, and the less will be its flowing power. In other words, the higher will be its viscosity.

In testing for viscosity, water is used as a standard. A solution is made of the glue, and the rate of flow of the solution at a certain temperature is compared with the rate of flow of water under the same conditions.

Several devices are on the market under the name of “viscosimeter” for measuring the viscosity of glue.

While they vary in detail they are in principle a pipette from which the glue-solution flows at a given temperature. The time required for the glue to run out of the pipette as compared with the time consumed in the same operation by the same quantity of water gives the relative viscosity of the glue.

The viscosity test is not entirely accurate in itself, but taken in connection with the jelly test it forms a very satisfactory basis for grading.

[Pg 28]

The jelly test is based on the comparative resistance power of the various glue-jellies. Several mechanical devices for determining jelly-strength have been perfected. One of these consists of a brass vessel which rests upon the glue-jelly, and into which shot is poured; the weight of the cup and the contained shot upon having penetrated to a certain depth in the glue-jelly, gives a figure which expresses the comparative strength of the jelly with the standard.

Another apparatus that has been found accurate and practical is the device illustrated on the next page. It consists of a pressure tube (A), over the mouth of which is stretched a thin rubber diaphragm (B). The tube connects to a rubber bulb (M) and to a pressure gauge, or manometer (E) with a scale (F). The pressure tube is filled with water to the[Pg 29][Pg 30] point (C). The manometer tubes also contain water. A three-way stop-cock (D) connects the tubes either to the bulb (M), or to the air, depending on the position. Below the pressure tube is a brass table (G), on which is placed the glass containing the glue-jelly to be tested.

When the glass is in position, the table is raised by means of a threaded wheel until the glue surface forces the water resting on the flexible diaphragm up to the fixed mark L. Then the stop-cock is turned to connect the pressure tube and gauge to the rubber bulb. By pressing the bulb the water is forced down in the pressure tube and so expands the diaphragm into the jelly, the liquid in the gauge rising simultaneously. Pressure on the bulb is continued until the water reaches the mark N.

Thereupon the stop-cock is again turned, the water is held at the point N, and the pressure is indicated by the height of the liquid in the gauge. The[Pg 31] degree of pressure is the measure of the consistency of the glue-jelly.

The initial contact between the jelly and the rubber diaphragm is always the same, all jellies therefore having the same initial pressure. When the diaphragm is forced down into the jelly, the pressure required depends entirely upon the resistance that the jelly offers. The slightest difference in the consistencies of the various jellies will alter the pressure required, the differences being accurately recorded by the gauge upon the scale.

Advantages of this apparatus are that the relative value of the jelly compared with the standard is expressed in concrete figures; the method of operation is simple; and the instrument is so sensitive that it will record a change in reading between two samples of glue in which a difference of ¹⁄₁₀₀th ounce of dry glue is used. Repeated tests may be made on the same jelly, as the surface is not[Pg 32] broken. With a little practice a single glue may be tested in twenty seconds, or less.

One of the most satisfactory methods of determining jelly-strength—and the one perhaps in most general use, is the finger test.

In this test the various glue-jellies are arranged before the tester, who presses each with the tip of the finger, comparing it with the standard as to resistance power. While this may seem to expose the final decision too greatly to the personal equation, as represented by the personality of the glue-tester, it is nevertheless true that an expert develops the most extraordinary precision, arriving at conclusions that are corroborated by the results of other tests and by the results in actual practice. The work of the glue-tester is analogous to that of the coffee-taster and the tea-taster, or experts[Pg 33] in other lines, who through a highly developed and keenly discriminating sense of taste, or touch, or smell, determine with extreme nicety the physical characteristics of the substances that they are accustomed to test.

To perform the tests described requires a degree of experience and an equipment beyond the reach of the ordinary buyer and user of glue.

Certain tests may however be made that are of great value in determining important facts about the glue it is intended to buy and use.

These tests could not be used as a basis for grading glue scientifically, but they are exceedingly valuable in determining its purity and its adaptability to the work in hand.

[Pg 34]

In the first place you should carefully sample your glue with a view to testing.

Take several samples from various parts of the barrel. Flake glue is often made up of different varieties, and a single sample may not be at all representative. Ground glue, from its very nature, is easily adulterated. It should be examined in a good light, for evidence of foreign substances. Examine flake glue carefully also for uniformity of odor and general appearance. If glue has been adulterated while in original form it is practically impossible to determine the adulteration by external appearance. Subsequent adulteration may be detected.

If you should notice white bubbles, in the shape of round blots, on the surface of the glue, you have found evidence of decay. If there is any doubt in your mind you can complete the evidence by[Pg 35] moistening the glue. If it gives off a sour odor you have an additional indication of putrefaction. Such glue should be avoided.

Bubbles may appear within the glue—not on the surface—without being an indication of putrefaction. As a matter of fact, bubbles are practically always found in certain high-grade glues, though practically never in low-grade bone or hide glues. They are supposed to be due to the air which gets in when the glue is poured into the moulds. When glue is originally dried on nets in very cool and dry weather, such bubbles are frequently found. Always beware of glue showing surface bubbles.

Besides being free from bubbles or blots a good glue is smooth, though not necessarily glossy. Sometimes the very best glue will be of a dull color, and many inferior glues even have a very shiny surface.[Pg 36] The surface should be uniform in color and in appearance.

These are not important, as a rule. The color of any particular lot of glue should be nearly uniform; otherwise it is subject to the suspicion of adulteration.

Bone glues are usually darker than hide glues, but some bone glues go through an artificial clarifying process which gives them the appearance of high-grade glues but really detracts from their strength. Very frequently oxide of zinc is added to glue, the effect being to make it set quickly, as well as to give it a light color. Some glues contain so much oxide of zinc that they are milk-white. Zinc oxide is not harmful except when added in very large quantities.

The best glues are neutral as to acid and alkali. Glues with an excess of acid[Pg 37] should be avoided, especially when used with oak or chestnut or other woods with strong acid qualities, as the acids in the glue may unite with those in the wood in such way as to have a destructive effect upon the glue. In such cases the glue will granulate after a time and the work will pull apart.

When a wood is being used that is strong in acid it is advisable to use a glue containing enough oxide of zinc to neutralize the acid in the wood. In making sizing for paper a glue containing either acid or alkali in excess should be avoided. It is also held by some authorities that acid in glue tends to bring about decay.

To test for alkali or acid, dissolve a small quantity of glue in water and dip a piece of litmus paper into the solution. Acid will turn the paper violet or red. Alkali will turn it blue. Litmus paper may be procured at any drug store.

[Pg 38]

This is a simple test that affords an important indication of the quality of glue. Take a small piece between the thumb and forefinger of each hand and bend it. A very thin piece of good glue will bend without breaking. When it does break, if the edges are splintery, great tensile strength is indicated. A clean fracture, on the other hand, indicates a brittle, low-grade glue, which has been subjected to heat so long as to destroy the tissue; or else it has been made from bone stock. High-grade glues never show glassy fractures, but bone glues do. In making this test, the air conditions of the room should be taken into account. If the glue has been kept in a dry room it will naturally break much more readily than if it has been in a moist atmosphere. This is especially important to bear in mind if comparative tests are being made.

[Pg 39]

A simple test for foam is to beat a solution of glue with an ordinary eggbeater. Glue which shows foam, or in which foam does not quickly subside, probably contains impurities. Foam is especially frequent in alum-dried glues and in cheap bone glues.

Some authorities believe that foam is caused by overheating, due to scalding by contact with steam jacket, or by steam coming into direct contact with the glue, or by heating for too long a time, or it may be due to the fact that all the grease has not been eradicated.

Glue that foams at ordinary temperature should be avoided for good work.

A moderate amount of grease may be a good thing when using with clay or with colors, but a large proportion of grease should be avoided when making glazed or coated papers, or in general use.

[Pg 40]

A glue at ordinary temperature which is not overheated on which a scum rises has an excessive amount of grease. It shows that the glue has not been properly skimmed in manufacture.

The keeping property of glue may be determined by letting the glue-jelly stand for several days exposed to the air, and noting any deterioration. It is customary to let the jelly stand at room temperature—but if the glue is to be kept under any special conditions the test should be made as nearly under these conditions as possible.

Deterioration is always accompanied by a sour odor. Avoid using any glue that does not smell clean and sweet.

Up-to-date practice in all the larger concerns using glue demands a laboratory for making tests. An expert is put in[Pg 41] charge and the glue analyzed chemically as well as for its physical properties. This method cuts the guess-work down to a minimum. Manufacturers whose output would not permit the employment of an expert all the year round can have glue analyzed in laboratories maintained for such purposes. It means often a great saving of money in the end to learn the exact properties of the glue you propose to use, or that you may be actually using.

We may also repeat what we have already said about securing competent advice from manufacturers. The glue user who takes a responsible manufacturer or glue house into his confidence will secure valuable counsel.

It is to the glue-maker’s and glue salesman’s interest to have you secure good results. They have a large experience to draw on, and when checked up by the results from actual practice in your glue-room their advice in regard to the selection of glues is usually worth heeding.

[Pg 43]

It is quite certain that glue-room methods in many factories are years behind the times. This is due to poor equipment, to ignorance and to carelessness. Many factories could not continue in business if the hit-and-miss methods of the glue-room prevailed in other departments.

It is possible to spoil the very best glue by improper methods of preparation; and not only is a vast amount of glue rendered totally unfit for satisfactory work, but a great deal is wasted; the total loss, through faulty methods, being about 25% of the entire amount used.

There is no reason why there should be such loss in the glue-room. The proper methods of procedure have been definitely established. Putting them into effect not only saves glue, but it enables better work; saves time of workmen, and increases greatly the general efficiency[Pg 44] of glue-room operations. The following rules are a guide to correct practice.

The function of soaking is to get back into the glue the liquid it originally contained.

Soaking in cold water gets the glue into proper condition to dissolve readily when heat is applied. If glue is soaked in warm water, or if melted without soaking, the glue on the outside will dissolve at once, and this will coat the remainder with a film, so that it will not readily dissolve, except when heat is applied in a degree that is harmful.

Glue has an affinity for cold water. Good glue will absorb from 1½ times to 2½ times its weight of cold water.

If glue is in flakes or strips, break up into small pieces. Soak the pieces from 10 to 12 hours in cold water. Soak ground glue 1 to 4 hours in cold water. Naturally[Pg 45] the thinner the glue the less time required for thorough soaking. The glue should be soaked through thoroughly and not merely moistened on the outside. You can determine whether the soaking has been completed by breaking a piece in two and noting conditions at the centre. If pieces are permitted to stick out beyond the level of the water, the natural result is that such pieces will be only partially softened. As the melting proceeds, these will slip to the bottom of the kettle, and in order to melt them long heating and high temperature are required. This means damaging the strength and adhesiveness of the glue.

In soaking ground glue it is a good plan to keep stirring as the glue is added to the water in the soaking vessel, as this helps to keep the fine particles of glue immersed in the water, instead of floating on the top. This is true also of thin-cut, high test glues.

[Pg 46]

In soaking and thinning glue, use only pure, cold water. Unless heater is provided with pure water attachment or pure water chamber, avoid using water from the glue-heater. Do not use water from boilers, for such water contains pipe-rust, acids from boiler compounds, sediment, and other matter extremely harmful to glue. See to it that all soaking vessels are scrupulously clean.

The soaking of glue in cold water before using is employed in some factories as a basis for comparative test of working quality. The amount of water absorbed may vary as much as 10 ounces in half a pound. Other things being equal, the glue that absorbs the most water is of course the cheapest to use. As a comparative test, melt up say 10 pounds of glue and see how much work it will do compared with the glue you are now using.

[Pg 47]

A simple and accurate apparatus may be had for determining the amount of water the glue will absorb for best working results, and also whether the amount of water actually used is the proper amount for this particular glue.

It is important to know these facts, since the more water a glue will absorb under proper working conditions, the cheaper that glue is to use.

The apparatus in question is illustrated on the next page. It consists of a copper pot and a hydrometer arranged for a temperature of 75° C., or 167° F. A sample of the glue to be tested is poured into the pot and the hydrometer is slowly allowed to sink into the solution until it finds its correct position. If the glue-solution is, for instance, 1 part glue to 3 parts water, the hydrometer will drop to 25 on the hydrometer scale. This will show that you have 25% dry[Pg 48] glue in the solution. The hydrometer is fitted with a temperature correction scale that enables the readings to be adjusted to the temperature of the glue-solution.

By noting the working qualities of glue prepared with various proportions of water, you can determine what is the correct amount of water to use, and then by using the hydrometer as each batch is prepared, you can be sure that the correct proportions are always being used. By making readings from time to time with the hydrometer, you can also determine the amount of evaporation that is going on, and in this way guard against the glue becoming too thick for proper use.

[Pg 49]

No special skill is required to use the hydrometer, and the readings are so quickly made, that tests can be made in every department in which glue is used without loss of time.

After the glue has been soaked in the manner described, the most important part of the process is undertaken—that is, the melting of the glue by application of heat.

The words “most important” are used advisedly. It is safe to say that most of the damage done to glue occurs in the melting process. There are all kinds of ways of melting glue, but many of them absolutely ruin glue for practical work. As this is a very important subject, it is well to get the rudiments thoroughly in mind—and for this purpose the reader should remember what has been said about the nature of glue—that it is made from animal matter; and that[Pg 50] it is composed of innumerable small fibres on whose strength the holding power of the glue depends.

Whatever injures and breaks down these fibres inevitably weakens the glue; so that in melting, every care must be observed to avoid the breaking down of the glue-fibres.

The most common destructive agent is heat. Just as the application of heat breaks down the fibres of a roast of beef, rendering it “tender” as the saying is, so the prolonged application of heat, or heat of too great an intensity, will destroy the glue-fibres, and therefore radically impair their value for actual use.

So, it is absolutely necessary to employ no more heat in melting glue than is required to reduce the soaked mass to the proper working consistency.

By actual experience it has been determined that a temperature of 130° to[Pg 51] 150° F. is all that is required to melt the glue to the requisite consistency; any greater heat is actually harmful, as it assists just so much more in the process of disintegration.

The term “boiling,” or “cooking,” never should be applied to the process of glue melting. These words imply a temperature of 212° F.—and such a temperature is ruinous to glue. In producing glue from the original stock—from the hides, bones, sinews, etc.,—boiling is necessary, in order to extract the gelatinous matter—but as we have already seen, the longer the stock is boiled, the weaker the product. “First boilings” are always best. In preparing for use, however, boiling is not necessary; therefore, never heat glue above 150° F.

Heat never should be applied directly, as this results in burning, or scalding, the glue.

[Pg 52]

Some glue-melting appliances have been constructed in which steam is turned directly upon the glue mass. This is bad practice of the most harmful kind.

Steam never should come into direct contact with glue. The temperature of steam is always at least 212° F.—under pressure it is much higher—and consequently it cooks the glue and destroys the fibres. Live steam burns glue just as it burns your hand if turned directly upon it.

The destructive effect of live steam upon glue may not be noticed at once, but work on which overheated glue has been used will eventually pull apart on account of the destruction of the glue-fibres.

One of the largest glue manufacturers in the country makes the following comment on this subject:

“In regard to the effect of live steam turned into a pot of glue, whether flake,[Pg 53] ground, or jelly—the glue would become overheated, and you know that always has a disastrous effect. The temperature of live steam is 212°, and under pressure it is even higher, so that at least the glue around the pipe will attain a temperature of 212°. The effect will be that the glue will be cooked to death and lose its strength. We would certainly discourage the application of live steam for dissolving glue as there is nothing to gain by it and everything to lose.”

Opinions of other manufacturers are unanimous on this point.

“We know of factories where they have made a careful test,” writes one, “and the results obtained from glue where it was melted with a live steam jet and where it was dissolved in a jacketed kettle were so greatly in favor of the latter method that it is used universally today.”

A further vital objection to the use of steam direct is that the steam contains[Pg 54] acids from boiler compounds, dirt, pipe-rust and sediment, all of them injurious to the strength and to the elasticity of glue.

Then too, glue always takes up moisture from steam. This changes the consistency of the glue. It leads to guess-work. The quantity of water added to glue must always be exactly regulated. Turning live steam on glue prevents proportions of glue and water remaining constant.

The only safe procedure in melting glue is to use a thermometer. If glue is melted in an open pot, or one in which the contents of the glue chamber can be reached easily, an ordinary drop thermometer, encased in a frame for protection, may be used.

It is preferable, however, to have the thermometer a part of the apparatus, with the mercury tube extending into[Pg 55] the glue chamber. In this way it is easy to keep watch on the temperature of the glue mass at all times.

An improvement even on this method is found in the automatic temperature controller that may be had with some glue-melting appliances, by which the supply of heat is automatically regulated. When the temperature in the glue chamber passes 150° F.—the absolute maximum of safe temperature—the valve automatically closes and shuts off the heat, re-opening again when the temperature has lowered from 5° to 10°. By the use of the automatic temperature controller the temperature is kept at the proper point, and there is no necessity of making observations with the thermometer except to verify your controller.

The temperature controller not only permits the scientifically correct preparation of glue, preventing overheating and ruined work, but saves also in expense of supervision.

[Pg 56]

Glue should be heated slowly, requiring about 30 minutes. Rapid heating dissolves the outer portions of the glue quickly, and a scum is then formed over the rest of the glue, preventing its proper melting.

The following precautions will be found useful to put into practice.

Dirt enters the melting-pot through the glue itself, the introduction of dirty brushes, or the exposure of the pot to dust, etc. If glue is melted in a dirty pot, the skin forming on the surface of the glue liquor gradually accumulates at the sides of the kettle and slowly decomposes. This may or may not fall into subsequent melts, thus contaminating them. The only way to make sure that it will not do so is to clean the pot.

Much unnecessary waste of glue may be avoided through observance of the[Pg 57] following procedure. The contents of the melting-pot exhausted, scraps of dried glue, as well as scraps of partially dried jelly adhering to the sides should be detached mechanically, as thoroughly as possible, and examined. If clean, they may be replaced in the bottom of the kettle; if dirty, they are to be set aside temporarily.

In the first instance, they are covered with the minimum of water necessary to soften, and the sides of the kettle swabbed with a little water in order to soften any glue that has dried and has not been detached mechanically. The pot is then gently heated in order to bring the scraps into solution, this solution used in work, and the pot thoroughly washed out with hot water and cooled before soaking a fresh portion of glue.

If the scraps have proved dirty, but not sour, they may be kept warm enough to permit the dirt to settle, when the glue may be used without risk. If sour[Pg 58] they must be thrown away. If the glue-pot is properly cleaned there is no danger of souring and all the glue may be used without waste.

It may be contended that much labor may be saved by adding sufficient water for the next melt, and through this means soften all glue adhering to the kettle in connection with that added fresh. It will be found, however, that the freshly added glue will absorb the bulk if not all of the water, leaving adhering scraps practically unsoftened, which in this way continue to accumulate, interfering with the proper working of the glue.

Pots, kettles, brushes, everything that comes into contact with glue, should be regularly and rigidly inspected, and kept absolutely free from dust and dirt. This is extremely important.

An important aid to cleanliness is the use of copper, aluminum or brass for all[Pg 59] parts of the apparatus with which glue comes into contact. Not only are copper, aluminum and brass the cheapest materials to use in the long run, due to their resisting acids in glue, water and steam which quickly corrode iron, but copper, aluminum and brass are practically self-cleaning.

Iron equipment is especially bad. It is most expensive in the end, for iron is quickly eaten away by acids in glue and water. Iron rusts, and the rust impairs the color and quality of the glue liquid. Do not use iron vessels under any conditions.

A great deal of waste in the use of glue is due to evaporation. If glue is heated in open pots, evaporation is very great. Evaporation weakens glue; makes it too thick for use, and also makes it very uneven in quality. Glue should always be melted in a closed vessel.

[Pg 60]

As glue deteriorates quickly if allowed to stand, no more should be prepared than is needed for a single day’s work. It is even better to prepare it twice or oftener during the day.

If glue is dissolved at the proper temperature and kept at that same temperature after melting, no noticeable deterioration results during the course of the working day. But if allowed to stand over night its value decreases, and it should not be mixed with fresh glue, as it is not of the same consistency.

With practice and observation you can easily determine each day’s needs in advance and prepare each morning just the right amount.

Glue is extremely sensitive to impurities.

[Pg 61]

Cultures of germs are grown by bacteriologists in gelatine glue because they afford an ideal breeding place for germs.

Glue quickly absorbs odors, and decays rapidly if exposed to impurities.

Decayed or decaying glue is not only extremely unpleasant to handle, but it is worthless to work with. Keep your glue clean. Keep it away from strong odors. Glue will keep sweet and clean before melting just as long as you care to keep it so.

Glue can not be expected to do good work if not kept at uniform temperature. See that the glue-room is of a temperature that facilitates uniform consistency of glue. Avoid possibility of drafts and consequent chilling of the melted glue.

Do not let glue freeze. If glue-jelly is frozen through it will crumble and act about like overheated glue. Glue frozen[Pg 62] only around the edges does not show pronounced deterioration. Do not take any chances. Keep the glue-room temperature above freezing at all times.

Glue is sold by the pound and should be used by the pound. Weigh not only the glue, but weigh the water as well. Keep an accurate record of weights.

Glue should be stored in a dry place. Barrels should not be unheaded prematurely, and after having been opened should be kept covered when not in use.

All surfaces to which glue is to be applied should be warm and dry. Hot glue will chill if applied to a cold surface, and if wood is being glued, moisture will have the effect of clogging the pores of the wood. Heat dries and expands the pores, allowing the glue-fibres to penetrate[Pg 63] deeply, thus insuring perfect adhesion.

At the same time there is danger of getting wood too dry, making it absorb too much glue, and too speedily. This causes a very quick setting, and may result in “starving” the glue joint.

Some users on this account recommend adding a little moisture to the surface of stock, by steaming or by application of a little warm water. There is more or less uncertainty on this subject. As a general conclusion it is safe to say that stock must always be warm; surplus moisture must be expelled; no “green” stock must be used.

Here again, as in so many other problems of the glue-room, observation of results under actual conditions should be the guide to practice.

One more thing of extreme importance—the employer should do everything[Pg 64] possible to secure the co-operation of every worker in the glue-room, from the foreman down, in using proper methods. A little personal interest here will be rewarded a thousand fold. Provide your workmen with proper equipment, which in itself encourages cleanliness, and show them how the quality of work may be improved.

Show them that an unclean, ill-smelling glue-pot is unnecessary. Show them that there is a right way, and a wrong way, to prepare glue—and the right way is the way to use. Introduce system into the glue-room, as into every other part of the plant.

Many workers are still ignorant of modern glue methods. It is the duty of the employer to know what the correct practice is, and to see that it is employed in his glue-room.

[Pg 65]

With the increased knowledge of the nature of glue, and of proper methods of handling, has come a great improvement in apparatus used. The primitive way of melting glue was to heat it in an open pot over a fire. No heed was given to the loss through evaporation; nor to the scalding of glue; nor to the dirty condition of the glue-pot, and consequently contamination of fresh glue by the remains of former melts frequently occurred.

We say “primitive” methods advisedly in speaking of this old-time way of melting glue; for in the light of modern knowledge such methods belong to a day gone by. Yet some glue-rooms still use the old open glue-pot, and many others use apparatus which shows little, if any, improvement.

Modern glue-room appliances are now available for every glue-room, for every[Pg 66] purpose. No glue user, large or small, can afford to use any but modern, scientific equipment. The saving in time, and in materials, and in improved quality of the completed work, and in the greater respect and increased efficiency of workers in the glue-room, all these things result in quickly repaying the increased outlay required.

The advantage of using copper, brass, and aluminum in glue-room appliances, due to their self-cleansing properties, already has been mentioned.

In apparatus designed for melting glue the use of copper, brass, and aluminum is absolutely required for economy and good results. Copper, brass, and aluminum are the only materials available that are not affected unfavorably by the action of acids in glue, steam and water; by boiler compounds, dirt, pipe-rust and sediment.

[Pg 67]

An iron agitator or stirrer in a glue-heater is corroded so quickly by the acids in glue, water and steam that in six months it is unfit for use.

A brass agitator, on the other hand, will last practically forever. So it is with every part of the glue-heater with which glue comes into direct contact.

The glue user who has had experience with galvanized iron heaters does not need to be told that the iron quickly is eaten away and the apparatus rendered unfit for use. It is certainly the part of wisdom to invest in copper, brass, and aluminum equipment, to which metals there is practically no “wear-out.”

Glue-room equipment of iron is still sold, but only because there are still some users who are so blinded by the initial small saving in outlay, as not to see the saving that accrues in the end from using indestructible materials—and the additional saving due to good work and economy of glue.

[Pg 68]

The facts already mentioned about the melting of glue should be borne in mind in choosing a glue melter, or glue-heater—always remembering in particular that it is of utmost importance that the heating agent should not come into direct contact with glue, and that the glue should not be overheated in preparation.

The glue-heater that has been proved most economical and efficient in wide-spread use has an air-tight glue chamber (to prevent evaporation), surrounded by a water-jacket (to prevent burning or scalding glue), the water in the jacket being heated either by direct injection of steam or by the use of copper heating coils. Electricity is also used successfully as a heating agent.

The heater is made of copper and brass throughout, and is therefore not affected by the harmful effect of acids in glue, steam and water, dirt, grease, pipe-rust,[Pg 69] sediment and other harmful substances. In this heater glue is reduced to a uniform and correct working consistency, and with unusual speed, if desired; 5 gallons of glue may be melted in less than 15 minutes, and as much as 50 gallons in less than one hour.

It has already been noticed that excessive speed in heating requires a degree of heat that is injurious.

A thermometer is provided with this heater that gives accurate readings of the temperature within the glue chamber, so that the heat may be turned off when the danger point of 150° F. is reached.

A still more recent and valuable improvement is the automatic temperature controller, a thermostatic valve which operates automatically to keep the temperature in the glue chamber between 145° F. and 150° F., or at any temperature for which it is set.

[Pg 70]

Not only overheating of the glue is prevented, but expense of supervision is reduced. The heater does not need to be constantly watched for fear glue will not be kept at correct temperature.

This particular heater is also provided with a brass agitator (hand or power) for keeping glue thoroughly mixed while melting, and with a special faucet by means of which the melted glue is drawn off without dripping or clogging. It is made in sizes from 2 gallons to 500 gallons liquid capacity, and for use with any heating agent—gas, electricity, or steam.

An apparatus of this kind not only facilitates economical melting of glue, by preventing evaporation, waste, formation of scum, sour and dirty glue, but it also insures uniform “spread.” Furthermore, it is a great incentive to accuracy and cleanliness on the part of workmen, encouraging them to good work by providing them with a neat and clean glue-melting appliance, in contrast with[Pg 71] the old-fashioned, unsightly and ill-smelling “glue-pot;” and providing them also with glue that has been properly prepared.

Above all, keep steam away from glue. Some glue-melting devices are on the market in which glue is prepared by subjecting to the direct application of steam. This produces only bad results. All authorities are now agreed on this subject. It is safe to say that the chief development in glue-room methods of the past ten years hinges entirely on the discovery of these facts: that steam ruins glue; that glue never should be heated above 130° to 150° F. at the utmost; that the other properties in steam—boiler compounds, acids, dirt, pipe-rust, sediment, and grease—are absolutely injurious to glue.

Do not let the argument of speed blind you to the damage resulting from the live steam type of dissolver. If you want speed, use a type of instantaneous[Pg 72] dissolver that prevents steam from coming directly into contact with glue. The very best practice, the one generally recommended by experts, is to heat glue slowly, with a heat not above 130° to 150° F. Then the glue is in the very best possible condition for work.

The effect of acids is such that they have been known to turn a pot of good glue black.

In wood-working establishments where much glue is used, it should be applied mechanically, by means of glue spreaders.

Some spreaders are made with Brussels carpet covering for rolls, but this is not good practice. The carpet covering absorbs dirt quickly, is difficult to keep clean, is liable to tear, is sure to stretch and eventually rots and wears out.

The simplest, cleanest, and cheapest method in the long run is to have rolls with corrugated surface; even spread is[Pg 73] thus assured, and there is practically no “wear-out” to them.

In order to keep glue at right temperature during use, it is best to have the glue-pans surrounded by heating coils. These may easily be connected with the steam boiler or gas heater; or electricity may be used.

A further improvement is to have the spreader connected with the glue-heater, as then only a minimum quantity of glue need be carried in the pans. By this method a quantity of glue sufficient for a day’s work or half-day’s work may be melted in the morning and maintained steadily at uniform thickness and temperature until used. The melted glue is fed to the pans only as needed, through open copper troughs.

Glue pans should of course be made of copper, for the reasons already mentioned. Another advantage is that copper pans are self-cleaning, as glue does not adhere to this material.

[Pg 74]

Spreaders may be had as a single-roll machine, for coating one side of stock, or as a double-roll, for coating both sides, or as a combination single and double-roll. They may be operated by hand or with power. When used with power a good operator can coat 13,500 lineal feet per day, with a good machine. The results with a glue spreader are largely due to the proper adjustment of the scrapers.

Glue spreaders can be used to coat flats, edges, straights and mitres equally well.

For coating plain and straight surfaces, use a solid roll. For tongued and grooved pieces, V-shaped stock, dovetails and other irregular shapes, use a brush roll. Some spreaders are fitted with combination solid and brush roll; a very convenient and economical arrangement.

The spreaders should be kept scrupulously clean, and also the brushes, if any are used. Clean brushes by filling glue pan with hot water and revolving the[Pg 75] brush in it until all the glue has been removed.

After gluing, the work should be kept under pressure for a sufficient length of time to insure perfect adhesion. In the case of hide glues the time required is from three to four hours. The time varies with variations in the glue, in condition of stock, and in temperature of room. No general statement can be made to cover the case; experience is the best guide. Either retaining clamps or presses are used.

Pressure should be distributed as evenly as possible. Presses may be had in almost every style for every need—open on one side, or on two sides; for veneered stock; sectional presses; etc. Very excellent presses are being made of structural steel. They are practically indestructible, very efficient, and yet simple in operation.

[Pg 76]

In selecting a veneer press equipment the amount of pressure per square inch must first be determined. Opinion varies with different manufacturers, some using 100 pounds, some 200 pounds, per square inch. The best general results are obtained by using 150 pounds per square inch. All presses made with a 2-inch screw should be designed to withstand a pressure of 8 tons or 16,000 pounds per screw. To find the tonnage of press that you require, multiply the length by the width of stock, this by the pressure per inch you desire and divide the results by 2,000. This will equal the tons pressure required. The number of screws per press can then be determined.

Glue is used in the wood-working industry mainly for making joints and veneers.

In large establishments, where many workmen are employed, a good plan for[Pg 77] distributing the melted glue is to arrange a battery of small glue-pots, or warmers, strung along a pipe line running from the steam boiler or gas heater.

Individual pots of copper which are filled at the central source of supply fit into cast-iron jackets, kept warm by steam which comes from the pipe line. The requisite temperature is thus maintained at minimum cost.

The valves may be so arranged as to cut off any warmer not in use, avoiding waste of heat. The arrangement is very satisfactory even in comparatively small establishments, and may be adapted to any number of individual pots.

When steam is used as the heating agent, only about one-fifth the amount of heat generated is actually used for heating the glue. Four-fifths of it radiates through the pipes and creates a heat so intense that the efficiency of the workmen[Pg 78] is reduced fully one-half in summer. With gas as the heating agent, the same conditions are present as with steam, plus the fire risk, which in itself is so great as to make gas extremely inadvisable.

Electricity is coming into greater favor every year, with the improvement of electrical glue-heating appliances. Electricity is still too expensive to justify its use as a heating agent, except for the exact purpose desired, but modern electrical devices, including the jacketed, heat-retaining glue-pot, make it possible to use electricity without waste.

The cost is less than either steam or gas and its advantages are so great that thousands of institutions are now using these “fireless” glue-heaters. The best electric glue-heaters are made of copper and brass, the greatest conductors of heat. They require much less heat than any other pot and the heat is required for just about one-fifth the time, owing to the heat-retaining jacket.

[Pg 79]

The answer to this question depends so largely on the individual conditions, that only very general suggestions may be given. We have already suggested the need of experimenting and accurately recording the results of using various kinds of glue. Once again, your dealer will give you good advice nine times out of ten—and your own experience should afford the most valuable check on his suggestions.

In general, the following glues are indicated:

Wood joints—High test hide glues. They make strong, firm joints, which is extremely important, as joints are subject to more or less tension; and they set rapidly.

Veneers—A moderately high test mixture of bone and sinew or bone and hide. The higher test glues set too quickly[Pg 80] for this particular kind of work. If a spreading machine is used, avoid a glue that tends to foam. Sometimes foaming is caused by its spreading too fast. Overheating glue also tends to foam it. This can be overcome by the addition of sweet oil or vaseline, paraffine or wax candle, but it is objectionable when veneering. It is best to be sure you have a glue that will not foam. Your dealer can tell you what glue to use.

Sizing—Use a glue free from grease and foam and one that flows freely.

Paper Boxes—A quick-setting hide glue is indicated for setting-up. For covering, a lower test bone glue is preferred, as it does not set so quickly. Paper box manufacturers are troubled more or less with foaming glue and can use the remedy suggested in the paragraph on veneers, as this will not be objectionable in paper box work.

Belting and Other Leather Goods—Here the principal requirements are[Pg 81] flexibility, resistance to moisture and tenacity. The higher test glues are generally preferred.

Bookbinding—For pasting covers, a low-grade bone glue answers all requirements sufficiently well. For rounding and backing, where strain is exerted, a high-grade hide glue should be used.

For Emery Purposes—Very high-grade glue that has been carefully prepared to eliminate all acids, alkalies and impurities. A good emery glue possesses superior water-absorbing qualities. To test a glue for emery purposes, soak an ounce in about five times its weight of water at room temperature for 48 hours. If at the end of the time the water shows discoloration, or if decomposition is evidenced by a disagreeable odor, the glue is not adapted to emery use; otherwise it may safely be used. Weigh glue after the operation, to get an idea of its water-taking properties.

[Pg 82]

While the high test glues cost more per pound, they go farther and do better work, except in cases when their quick-setting characteristics are an objection.

How much you can afford to pay for your glue is a question that you must answer from your own observation and tabulation of results. In certain lines it would be foolish to use a high-grade glue, where the work would not benefit in proportion to the increased expenditure. Any attention given to the subject will be well repaid.

Always keep accurate records, and base your future purchases upon the demonstrated comparative results already attained by the various glues you have used in actual practice.

No glue is good to use unless properly prepared. A 16-cent glue may be reduced to the grade of an 8-cent glue by overheating.[Pg 83] The grade of the glue at the time it is used is the important thing.

Do not by faulty methods of preparation impair the working quality of your glue. A glue of moderate high-grade properly prepared is better for practical purposes than a high-grade glue whose working quality has been destroyed by excessive or prolonged heating.

Sometimes it is desired to use glue with waterproof qualities. Glue is rendered practically waterproof by adding a small quantity (about 1%) of ammonium or potassium bichromate to the glue liquid. Upon hardening, the glue then becomes waterproof. Adding a small quantity of formaldehyde to the liquid glue will help it to resist the action of water after it has dried for some time.

Others suggest dissolving glue in an equal quantity of water and adding about as much linseed oil as water, with the[Pg 84] aid of heat, until a jelly is formed. This mixture is said to be practically waterproof.

A patented process has recently been put out for which the claim is made that it can be applied to any glue irrespective of grade or make, rendering it absolutely waterproof. The result is attained by mixing the glue with certain chemicals in specified proportions, and then adding a certain amount of formaldehyde. Any amount of glue can be treated and the process is said to be most effective.

Of recent years efforts have been made to find a substitute for animal glue. The effort has met with success to a certain extent for particular kinds of work. Probably the newest addition to the list of vegetable glues is the mineral glue-silicate of soda. Liquid silicates were first sold for the manufacture of soap. In recent years certain forms have been used for[Pg 85] light adhesive paper work. It is used in places where glue is too slow setting.

When a glue is desired to set very quickly the manufacturer can usually furnish glue with the setting qualities desired for the particular work in hand. If this cannot be done, for any reason, remember that the temperature of the glue is an important factor. A low temperature aids in quick setting. Some paper box manufacturers have had successful results in quick setting by adding a small quantity of turpentine to the liquid glue. Some add silicate of soda.

Specially made glues are supplied by manufacturers for work in which flexibility is needed. An easy way to increase the flexible quality of glue is to add a little glycerine to the liquid glue.

[Pg 86]

Inconsistent hyphenation has been standardized throughout.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.