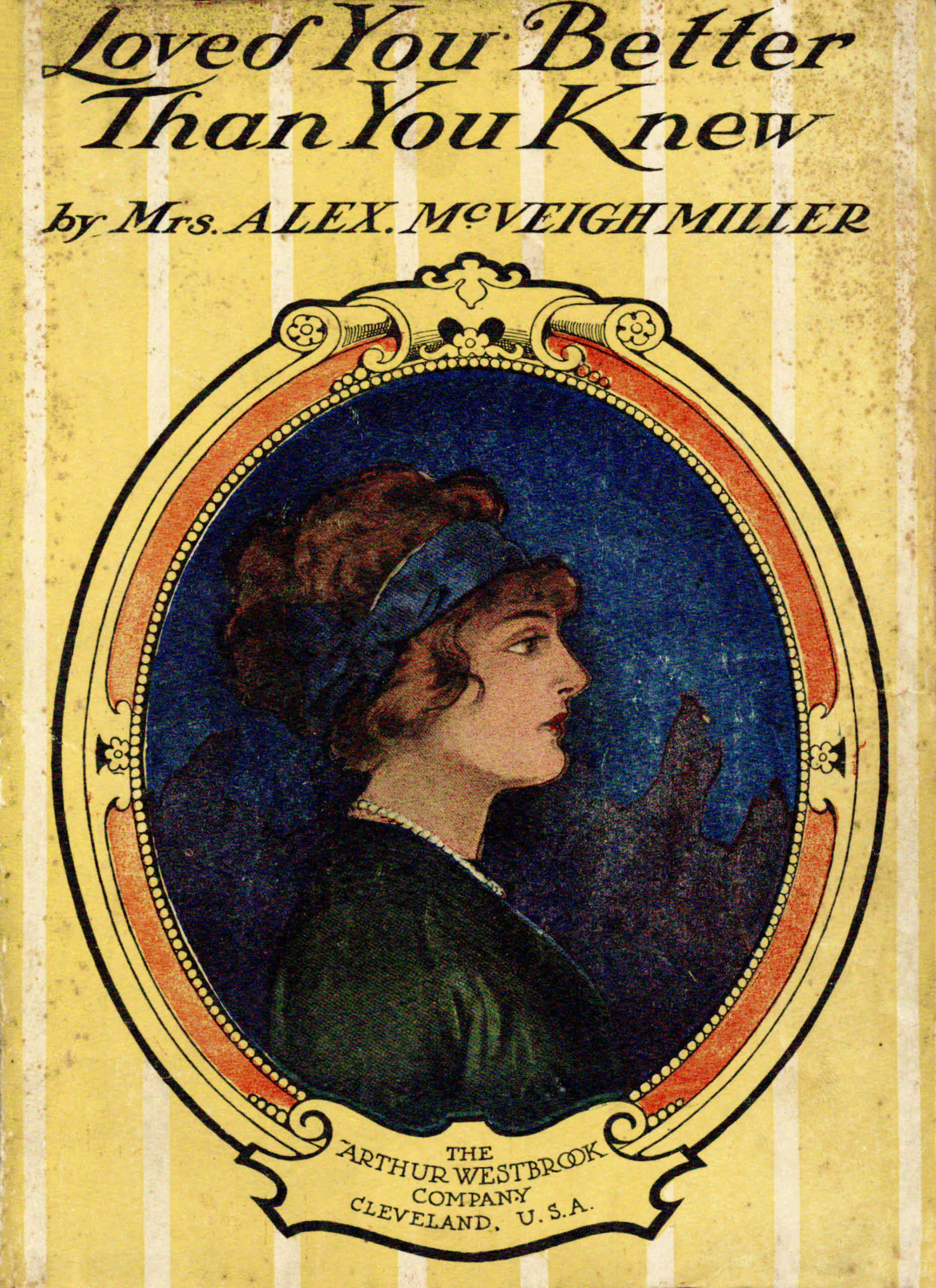

By Mrs. Alex. McVeigh Miller

HART SERIES NO. 59

COPYRIGHT 1897

BY GEO. MUNRO’S SONS

Published By

THE ARTHUR WESTBROOK COMPANY

Cleveland, O., U. S. A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Cupid in the Rain | 5 |

| II. | One Golden Hour | 13 |

| III. | The Sweet Old Story | 21 |

| IV. | Breakers Ahead | 25 |

| V. | Retrospection | 29 |

| VI. | Rebellion | 34 |

| VII. | “The Fates Forbid It” | 40 |

| VIII. | A Dark Secret | 45 |

| IX. | A Bunch of Roses | 51 |

| X. | A Feminine Weakness | 55 |

| XI. | Cinthia’s Elopement | 63 |

| XII. | Outwitted | 69 |

| XIII. | Oh, What a Night! | 74 |

| XIV. | Parted at the Altar | 79 |

| XV. | “An Eternal Farewell!” | 85 |

| XVI. | “Oh, What a Time!” | 90 |

| XVII. | A Deadly Feud | 95 |

| XVIII. | “Remember That I Loved You Well” | 103 |

| XIX. | A Tragic Past | 109 |

| XX. | Love and Loss | 113 |

| XXI. | A Quarrel with Fate | 119 |

| XXII. | When Years Had Fled | 127 |

| XXIII. | “I Can Not Love Again!” | 137 |

| XXIV. | “The Pangs That Rend My Heart in Twain!” | 144 |

| XXV. | “Like an Angel” | 147 |

| XXVI. | ’Neath Southern Skies | 152 |

| XXVII. | “Where the Clematis Boughs Intwine” | 156 |

| XXVIII. | Only Friends | 161 |

| XXIX. | A Secret Sorrow | 169 |

| XXX. | Mysteries | 172 |

| XXXI. | Most Bitterly Bereaved | 176 |

| XXXII. | “A Cold Gray Life” | 181 |

| XXXIII. | Puppets of Fate | 187 |

| XXXIV. | “The Weight of Cruel Years Piled Into One Long Agony” | 192 |

| XXXV. | Cinthia’s Betrothal | 197 |

| XXXVI. | An Obstinate Woman | 201 |

| XXXVII. | Beyond Forgiveness | 208 |

| XXXVIII. | Her Side of the Story | 214 |

| XXXIX. | A Mortal Wound | 219 |

| XL. | A Late Repentance | 224 |

| XLI. | “The Greed of Gold” | 230 |

| XLII. | In the Sunshine | 235 |

Loved You Better Than You Knew

Could one lift the impenetrable veil of mystery that hides the future from our curious eyes, what secrets would often be revealed, what shadows would fall upon hearts now light and thoughtless—shadows of grief, of horror, and despair!

“It is better not to know,” agree both the poets and sages.

[6]

Beautiful Cinthia Dawn did not think of that as she drummed upon the window-pane that rainy autumn day, exclaiming rebelliously:

“I wish something would happen to break up the dreadful monotony of my life.”

Widow Flint, who was her aunt and guardian, and as crabbed and crusty as her name, looked at her with dismay, and retorted:

“Some people don’t know when they’re well off. You have enough to eat, to drink, and to wear, and a good home. What more do you want?”

The girl looked at the dingy sitting-room, her own shabby gray gown, then out at the dismal landscape, blurred by the rain and low-hanging clouds, with something like frank contempt, and answered, recklessly:

“I want pretty clothes and jewels, beautiful surroundings, gay times, and lovers, such as other girls have instead of this humdrum, poky existence—so there!”

“Humph!”

It was all Mrs. Flint said aloud, but to herself she added:

“Good land! I do wish my brother would come home from his eternal wanderings and take charge of his rattled-brained daughter. She’s too pretty and restless, and I don’t see how I’m going to hold her down much longer.”

Cinthia Dawn was seventeen now, and ever since she had been given into her aunt’s sole keeping at five years[7] old, the strait-laced soul, who was as prim and particular as an old maid, had been engaged in the difficult task of “holding down” her spirited young niece. She had even erred on the side of prudence, so great was her anxiety to bring her up in the way she should go.

When the lovely child first came her aunt said frankly to all:

“I don’t want anybody ever to tell Cinthy that she is pretty.”

“She can find it out for herself by just looking in the glass,” objected one of her cronies.

“I’ll tend to that,” said Mrs. Flint, crustily, and she furnished her rooms with cracked and distorted mirrors, whose blurred surfaces gave back indeed no fair reflection of the child’s beauty.

She carried out her programme further by dressing the child in the plainest, commonest clothing, and plaiting all her wealth of golden curls in a single tail down her back, though she could not prevent it even then from breaking out on her brow and neck in enchanting little ringlets that a ballroom belle might have envied.

To her dearest crony Mrs. Flint excused her course by saying, confidentially:

“Cinthy’s mother, who is dead now, was the vainest and prettiest creature on earth, and she did wicked work with her beauty. I don’t want to say aught against her now that she is dead; but Cinthy must have a different raising, that’s all. My brother said so when he put her[8] in my charge. ‘Bring her up good and simple in your old-fashion way, Rebecca,’ was what he said.”

“That’s right. ‘Favor is deceitful and beauty is vain, but a woman that feareth the Lord, she shall be praised.’ That’s Cinthy’s Bible verse, and I hope she’ll live up to it,” returned the good crony, Deacon Rood’s wife.

So Cinthia Dawn was reared simply and plainly almost to severity. She received her education at the public school, and at home helped her aunt with the house-work. Surreptitiously she read poetry and novels.

Such a simple, quiet life—just like thousands and thousands of others—but Cinthia was outgrowing it now. She was seventeen—the most romantic age in the world—and she chafed at the dreariness of her life.

School-days were ended now, and her merry mates had their new gowns, their dances, and their lovers. There were none of these for Cinthia Dawn.

Mrs. Flint said her niece was nothing but a child yet, so she was not permitted to attend parties, and she vowed she had no money to spend on finery. As for lovers, if she had any, the bravest would not have dared present himself at Mrs. Flint’s door. She would have said to him as to the veriest tramp:

“Be off!”

It was just the life to drive a pretty, spirited girl frantic with impatience of the present, and longings for something better than she had known—the longing that found impatient expression that afternoon when she watched the[9] dead leaves flying in sodden drifts beneath the chill November rain.

After Mrs. Flint’s curt rejoinder to her complaints she remained silent several minutes drumming impatiently on the pane, then burst out:

“Oh, Aunt Beck, don’t you want me to run down to the post-office for your Christian Advocate?”

“In all this storm?”

“Oh, I won’t mind it a bit! I’m in a mood for fighting the elements!”

“Then take your umbrella and overshoes, and hurry back.”

“Yes, aunt.”

Glad to escape from the monotony of the little brown house, she hurried out into the teeth of the storm, and made her way through the village streets to the little post-office. The rain blew in her face, and the wind crimsoned her cheeks and made her dark eyes flash like stars. Cinthia did not care. In her splendor of youth and health she found it exhilarating.

But going back, the storm, that had been gathering its forces for a fiercer onslaught, increased in angry violence.

She had left the paved main street, too, now, and was emerging into the thinly populated suburbs where her home was situated.

A great gust of wind met her at the corner of a street, taking her breath with its fierce onslaught, wrapping her damp skirts about her ankles, and whisking her umbrella[10] from her grasp. She chased it wildly almost a block, only to see it whirled into the middle of the street and crushed under the wheels of a heavily loaded farm wagon lumbering into the little town. Meanwhile, the vagrant wind pelted her with drifts of dead leaves, and the flood-gates of heaven opened and poured down torrents of water.

“Take my umbrella, Miss Dawn!” cried the gay musical voice of a young man who had been chasing her as fast as she flew after the umbrella.

Turning with a quick start, she looked into the face of Arthur Varian, a new comer in the town, with whom she had recently formed an acquaintance. His laughing blue eyes were irresistible, and she cried merrily as she took shelter under the umbrella:

“Didn’t I look comical chasing the parachute? I was hoping no one saw me. Thank you, but I can not deprive you of it.”

“Then you will let me hold it over you? It is large enough for both,” stepping along by her side, and giving her the best half of it as they struggled along against the high wind. “I saw you coming out of the post-office and have been trying to overtake you ever since. I thought perhaps you would allow me the pleasure of walking home with you,” continued Arthur Varian, bending his admiring blue eyes on the beautiful face by his side—the bright, arch face with its large, soft dark eyes set off by that aureole of curly golden hair, now blown into the most enchanting spiral rings by the wind and rain.

[11]

He had met her several times before, and he knew enough of her lonely life to make him sympathize with her forlornness, even if her beauty had not already charmed him with its girlish perfection.

Cinthia met that glance and looked down with a kindling blush and a wildly beating heart, for—it was of him she had been thinking when she uttered her complaints to Mrs. Flint, longing for the privileges of other young girls of her class that she might have opportunities of meeting him and winning his heart.

Who could blame her? for Arthur Varian was very winning and handsome—tall, with wavy brown hair, regular features, a slight brown mustache, a beautiful mouth—“just made for kissing,” vowed all the girls—well dressed, and having that indefinable air of ease and elegance that betokens good breeding joined to prosperity.

Perhaps the fates had heard Cinthia’s longing for something to happen, for the storm now gathered fresh force, and the darkening earth was irradiated by a vivid and brilliant flash of lightning, followed by a terrific thunder peal.

The rain poured out of heaven like a waterfall, and the fierce driving gale caught the frightened girl up like a feather and tossed her against the young man’s breast and into his arms, that clasped and held her protectingly, while all about them the air was darkened with flying débris and broken branches of trees that swayed, and[12] creaked, and bent, and crashed in agony beneath the cyclonic force of the elements.

Cinthia was not a coward, but the situation was enough to strike terror to the bravest heart. The edge of a cyclone had indeed struck the village, and in almost an instant of time dozens of trees had been uprooted, several houses unroofed, and the air filled with flying projectiles, one of which suddenly struck Arthur Varian with such force that both he and his companion were hurled to the ground. It was a portion of a tin roof, and cut a gash on the young man’s hand from which the blood began to stream in a ruddy tide.

In another minute the wind began to abate, and they struggled up to their feet.

“Oh, you are cut, you are bleeding! and you did it to save me! I saw you ward off that horrible missile from me with your hand. It must have killed me had I received the blow, for, as it was, it grazed my head. Oh, what can I do? Let me bind your hand to stop the blood,” sobbed Cinthia, unwinding the silk scarf from her neck and wrapping it tightly, with untaught skill, about his wrist above the wound to stop the spurting blood.

[13]

She trembled and paled as the warm blood spurted over her own white and dainty hands as she essayed the task, and her heart throbbed wildly with new and sweet emotion. She could have clasped her arms about his neck and wept over the cruel wound he had received in her defense and for her sake.

“Thank you. That will do very well,” Arthur Varian cried, gratefully; and taking her hand gently, he added: “I see we are almost at the gates of my home. You must come in with me till the storm is over, then I will take you home in the carriage.”

Thoroughly frightened, and glad of a shelter from the still angry elements, Cinthia accompanied him inside the gates of the finest residence in the county—Idlewild, as it was called—being a large rambling old stone mansion, exceedingly picturesque in style, and surrounded by a fine estate in lawns, gardens, and virgin woodlands. For many years the place had been tenantless, save for the old housekeeper in charge, but last summer it had been carefully renovated, and Arthur Varian and his widowed mother, who owned the place, had come there to live.

As the young man led Cinthia in, he added, thoughtfully:

“You are quite drenched, but my mother will give[14] you some hot tea and dry clothing, and perhaps that will prevent your getting sick.”

“Oh, I don’t think the wetting will hurt me. I’m very strong,” Cinthia answered; adding, bashfully: “I shouldn’t like your mother to see me looking like I had been fished out of the river. You had better take me to the housekeeper. I know her well. She has been lending me novels and poetry from your library ever since I was a little girl.”

And, in fact, before they rang the bell the front door flew open, and the old woman appeared, pouncing upon Cinthia, and exclaiming:

“Come right in out of the wet, you poor, dear child! I saw it all from the window, and I thought you both were killed when the piece of tin knocked you both down. I believe it is a piece off of our own roof. My heart jumped in my mouth, and I was about to faint when I saw you both rising to your feet, and I got better at once. But, law sakes! wasn’t it terrible? Your hand’s cut, too, ain’t it, Mr. Varian? Well, I’ll see to’t in a minute, as soon as I take Cinthy to my room.”

Leading the dripping girl along the corridors to a plain, neat bedroom, she produced a dainty white night-gown, saying:

“There, honey; jest strip off your wet clothes and put on that, and jump into my bed and kiver up warm, whiles I go and sew up that cut on Mr. Arthur’s hand, for I can do it jest as neat as any doctor. Then I’ll dry[15] your clothes and brew you both some bone-set tea to keep you from ketching cold.”

She bustled away, and Cinthia gladly did as she was bid, looking ruefully at the puddles of water that streamed from her clothing on to the neat Brussels carpet.

When Mrs. Bowles returned she was indeed covered up in the warm bed, with only her bright eyes and the top of her golden head visible.

“Do you feel chilly, dearie? Drink this, to warm your blood,” she said, forcing a bitter concoction of bone-set tea on the protesting girl; adding: “Law, now, ’tisn’t so bad, after all, is it? Why, Mr. Varian drank his dose without so much as a wry face. Law, honey, but that was a deep cut! It almost severed an artery. It took all my nerve to sew it up, I tell you, and he’ll have to carry his hand in a sling some time, sure.”

“He saved my life!” cried Cinthia, eagerly. “I would have received that blow on my head but that he so quickly warded it off with his hand. See, it just grazed my temple,” showing a little bleeding scratch under her ringlets.

“Dearie me, let me put a strip of court-plaster on it! There, it’ll be well in a day or two. Now, Cinthia, you take a little nap whiles I hang your clothes to dry in the laundry,” gathering them up into a bucket.

“I’ve ruined your carpet,” sighed the girl.

“Oh, no; it’ll be all right when it’s dry. Them colors[16] won’t run. Don’t worrit over that, but shet your eyes and go to sleep,” bustling out again.

“Dear old soul!” sighed Cinthia, grateful for the kiss pressed on top of her curly head. She shut her eyes, but she was too nervous to sleep.

She lay listening to the storm that still raged outside, and wondering what her aunt would think of her protracted stay, if she would be angry, or just frightened. Then her thoughts flew to Arthur Varian, his tender smiles, his bonny blue eyes.

“I will never marry any man but a blue-eyed one,” she thought, thrillingly, and at last fell into a gentle doze induced by weariness, the warmth of the bed, and the dose she had swallowed.

The nap lasted an hour, and when she opened her eyes Mrs. Bowles was rocking placidly by the cozy fire in the twilight.

“Oh, I have been asleep! How long?” she cried, uneasily.

“Most an hour. Do you feel rested?”

“Oh, yes, indeed, and I’d like to get up and go home. Are my clothes dry?”

“Oh, no—not yet; and as for that gray woolen frock of yours, it has shrunk that much you can never hook it up again, I can tell you that! But no matter. You’ve had it two years a’ready. I know, and it was too skimp for a growing girl, anyway. But Mrs. Varian has sent[17] you in a suit of her clothes to put on, and when you’re dressed you are to take tea with her and her son.”

“Oh, but, Mrs. Bowles, I ought to go home at once. Aunt Beck will be so uneasy over me.”

“Listen to the wind and the rain, child. The storm is still raging, and the horses can’t be taken out till the weather clears up. So make your mind easy, and get up and dress, for Mrs. Varian will be in to see you presently.”

Cinthia got up rather nervously, with a little dread of Mrs. Varian, whom she had seen at church and out riding—a beautiful, haughty-looking woman, with olive skin and flashing dark eyes, very young looking to have a grown son of twenty-three or four.

“I would rather have my own clothes,” she said pleadingly.

“They are all over mud and water, child, and I don’t think the maid can have them fit for you till to-morrow. Mrs. Varian very kindly offered the loan of hers, and unless you wear them, you’ll have to go to bed again, that’s all. Here, let me help you,” said Mrs. Bowles, beginning to slip the garments over Cinthia’s shining head.

“But this crimson silk with white lace trimmings—it is too fine for me, dear Mrs. Bowles.”

“It can’t be helped, for this is more likely to fit—too tight in the waist for her, she said, and she never wore it but twice; and see, it laps over two inches on you. But I can hide that with the lace at the neck and the bow at[18] the waist. Now let me comb your hair loose over your shoulders, it’s so damp yet. My! how it crimples up and curls, and shines in the light! You look well, Cinthy Dawn!” She would have said beautiful, but she was mindful of Mrs. Flint’s objection, though she said to herself:

“She can’t keep Mr. Arthur from finding it out, that’s sure. He knows it a’ready, by the look in his eyes when he brought her in. And it’s hot, impulsive blood that flows in the Varians’ veins. What is going to come of this accident, I wonder? for I saw love in her eyes when she told me how he saved her life. I hope he didn’t save it just to blight it.”

Cinthia went to the old woman’s mirror and looked at herself in the unaccustomed gown.

The glass was not blurred and cracked like those at home, and it gave back her charming reflection truthfully.

“Why, how pretty I look!” she cried, gazing in frank delight at the beautiful vision, the lissom form, just above medium height, the regular features, the fair arch face, the starry dark eyes, the rose-red mouth, the enchanting dimples, and the aureole of golden hair that set it off like a halo of light. “Why, Mrs. Bowles, I did not know I was so pretty! But perhaps it’s only the dress.”

“Fine feathers make fine birds,” returned the housekeeper, discreetly.

“Yes,” sighed Cinthia; but she continued to gaze at[19] herself in delight, wondering, shyly, what Arthur Varian would think of her in his mother’s fine gown.

Then she turned with a start, for a light tap at the door announced the entrance of Mrs. Varian, and the housekeeper hastened to present the young girl to her mistress.

Both thrilled with admiration, for both were rarely beautiful in their opposite types, the elder a brunette of the finest style, the younger a dark-eyed blonde, so rarely seen, so much admired.

“I hope you have quite recovered from your fright, Miss Dawn,” her hostess said, in a voice so exquisitely modulated that it was as pleasant as music.

Cinthia murmured in reply that she had enjoyed a delicious rest, and was so grateful for the loan of the clothes that made it possible for her to escape from bed.

“I dare say our good Mrs. Bowles would have liked to keep you there all night. She suggested that plan to Arthur after dosing him with bitter herb tea; but he disregarded her advice, and is now waiting impatiently for you,” rejoined the lady, casting an arch glance at the old woman while she took Cinthia’s hand and drew her toward the door.

When the door closed on them the old housekeeper wagged her head doubtfully.

“How sweet my mistress can be when she pleases; but I wonder if she would be as kind if she guessed what I have read in those young peoples’ eyes—that story of[20] love—love between a rich young man and a poor young girl, that folks like Mrs. Varian call misalliances?” she muttered, uneasily.

No matter what the outcome was to be, Cinthia Dawn had come to the happiest night of her life.

Though outside the windows the wild wind and rain swirled and beat with ghostly fingers, inside Mrs. Varian’s luxurious drawing-room all was warmth and light and pleasure.

The lady and her son exerted themselves to make their young guest happy, and she was so glad and grateful in her pleasant surroundings that all were mutually sorry when toward ten o’clock the storm abated, and the moon struggled fitfully through the lowering clouds.

“I must go home!” cried Cinthia, with wholesome dread of Mrs. Flint’s wrath; and their warmest urgings could not prevail on her to stay—though in her secret heart she longed to do so forever. “I shall bring back your clothes to-morrow,” she laughed, as Mrs. Varian bid her a cordial good-night.

Then Arthur handed her into the waiting carriage, stepped in by her side, and the driver closed the door; and of that ride home we shall hear more in our next chapter.

[21]

Mrs. Flint grew very uneasy over her absent niece as the short afternoon waned and the fury of the storm increased to positive danger for any luckless pedestrian. After fidgeting and worrying until the early twilight fell, she began to say to herself that Cinthia was probably all right, anyway. She had doubtless gone into some friend’s for shelter, and would not likely return until morning.

She took her frugal tea alone and in something like sadness, for Cinthia had seldom been absent from a meal before, and she began to feel what a loss it was to miss the fair young face about the house. She suddenly realized the tenderness lying dormant in her heart for the wilful girl.

She sat down by the cozy fire with her knitting, and listened to the tempest of wind and rain soughing in the trees outside, and Cinthia’s rebellion that afternoon kept repeating itself over and over in her brain until she muttered aloud:

“She wants fine things and parties and lovers, does she? Well, well, I s’pose it’s natural enough for her mother’s child, and for any young girl for that matter, but where’s she going to get them? The lovers would be easy enough—she’s as pretty as a pink—but I don’t want[22] to encourage her vanity, and it’s better to save the money her father sends till she needs it worse. What if he should die way off yonder somewhere, and maybe not leave her a penny? I wish he’d come home, I do, or I wish she was homely as sin, with red hair and freckles, and a snub nose like Jane Ann Johnson!”

So she fretted and fumed until past ten o’clock, and that was an hour beyond her usual bed-time; but somehow she could not get Cinthia out of her mind, could not bear to retire while she was away, so she kept glancing at the window, though scarcely expecting her to arrive before morning. How could she, in such a storm, though the wind had lulled somewhat, and the patter of the rain was dulled on the drifts of dead leaves that muffled the sound of carriage-wheels, pausing too, so that Mrs. Flint almost jumped out of her skin when there suddenly came a loud rat-a-tat, rat-a-tat, upon the front door.

But she was not naturally nervous, so after a moment’s startled indecision, she flew to the door and demanded, through the key-hole, to know who was there.

“It is Cinthia, aunt,” returned a sweet, mirthful voice.

With a sigh of relief the old lady unlocked the door, and there stepped into the narrow hall a vision that took her breath away.

Was it Cinthia Dawn or a fairy princess, this beautiful creature in the crimson silk and misty lace, the furred white opera-cloak falling from her shoulders, the rippling lengths of sunny hair enveloping her like a halo, the dark[23] eyes beaming with “that light that never was on sea or land,” but only in the glance of the happy and the loving?

“Cinthia Dawn!” she began, in a dazed voice; but just then she became aware that a tall and handsome young man, hat in hand, was standing on the threshold. She knew who he was. Her pastor had introduced her last Sunday, at church, to the master of Idlewild.

“Good-evening, Mrs. Flint,” he began, beamingly. “I have brought Cinthia home safe to you. My mother took care of her during the storm.” He paused, faintly hoping that she would ask him to enter, it was so early yet.

But he did not yet know Mrs. Flint, much as he had heard of her eccentricities. She simply bridled, and returned, in her stiffest manner:

“I’m sure we are very much obliged to your mother, and you, too. Good-evening.”

Thus curtly dismissed, the young man shot a tender glance at his sweetheart, and bowed himself out into the night again, the lady slamming the door behind him before he was fairly down the steps.

“Oh, Aunt Beck! how could you be so rude after all their kindness to me? And he saved my life, too. Didn’t you see his arm in a sling?” indignantly.

“I don’t know as I noticed it. I was so flustrated seeing you bringing a beau home, and you nothing but a child yet!” snapped the old lady.

“Child!” echoed Cinthia, scornfully, as she held her[24] chilly fingers to the blaze and the ruddy light played over her beautiful garments.

“But what are you doing with the silk gown, and that grand white cloak, all brocade and ermine? I don’t understand!” cried the old lady, suspiciously.

Cinthia laughed out gayly, happily, her eyes shining, her voice as sweet as silver bells.

“Why, I was caught in the rain and almost drowned, Aunt Beck, and my wretched old duds were nothing but mud and water, so Mrs. Varian lent me these things to come home in. Aren’t they becoming? Don’t I look pretty?” setting her graceful head one side, like a bird.

“Humph! ‘Pretty is as pretty does,’” grunted her aunt, though she could not keep her eyes off the charming creature as she flung herself back in an easy-chair and continued, gayly:

“If you are not sleepy, Aunt Beck, I’ll tell you all about it.”

“I guess I can keep my eyes open!” ungraciously, though she was dying of curiosity.

Thereupon Cinthia related all the events of the evening, from the time she had left home until she bid Mrs. Varian good-night to return in the grand carriage with the handsome master of Idlewild. Clasping her tiny hands, she cried, in an ecstacy:

“Oh, aunt, I can’t tell you how I enjoyed it all! Mrs. Varian is as proud and beautiful as a queen; but she was so kind and sweet to me that I felt quite at home in[25] her grand house. As for her son—oh!” and Cinthia paused and blushed divinely.

Mrs. Flint snapped, irately:

“Now, Cinthia Dawn, don’t you go getting your head turned by idle flatteries from rich young men. Anybody but a silly child would know they don’t mean anything.”

“Oh, Aunt Beck, please don’t call me a child any more. I am as grown up as anybody, and you know it—seventeen last April. And—and”—wistfully and defiantly all at once—“he does mean it. He loves me dearly—and—we—are—engaged!”

Aunt Beck gave a jump of uncontrollable surprise.

“Cinthy Dawn, you don’t mean it?”

“Yes, I do, Aunt Beck. I have promised to marry Arthur Varian.”

“But, land sakes, child—oh, I forgot; well girl, then—you don’t hardly know each other!”

“Oh, yes, we do. We have been acquainted some time. We fell in love weeks ago, and—and—he told me in the carriage he loved me and wanted to marry me.”

Mrs. Flint was so surprised she could not speak; she could only stare in wonder at the beautiful, excited creature with her happy face.

[26]

“Oh, aunt, you are not angry, are you? He’s very, very nice, I’m sure—and rich, too! He said my every fancy should be gratified—that he would worship me. You will give your consent, won’t you, because he’s coming here to-morrow morning to ask you.”

Mrs. Flint found her voice, and muttered, sarcastically:

“A wonder he didn’t ask me to-night! Why didn’t you tell him you would have to get your father’s consent?”

“Because papa has deserted me ever since I was small, and cares nothing for me. It is you I’ve had to look for the care of father and mother both. Why, look you, papa has never written me a line all these years! He does not care what becomes of me. And we shall not ask him anything. You are my guardian, and will give us leave to marry, won’t you, dear?”

“When, Cinthy?”

“Oh, very soon, he said—not later than Christmas, anyway. We don’t want to wait long. You’ll be willing, won’t you?” impetuously.

“I don’t know, dear. I’ll have to sleep on it before I make up my mind; you’ve given me such a surprise. Though I don’t say but that it’s a grand match for a girl like you, Cinthy.”

“He said I was made for a prince.”

“Of course. People in love are silly enough to say anything. But take your candle and go to bed now, Cinthy, and we will talk about this again to-morrow.”

[27]

“Good-night, aunt,” and she lingered, perhaps hoping for a kindlier word.

The old lady, moved in spite of herself, and secretly proud of Cinthia’s conquest, actually kissed the rosy cheek, saying, merrily:

“Good-night—Mrs. Varian that is to be.”

Cinthia’s heart leaped with joy and pride, for she took this concession to mean approbation of her choice.

With the chorus of a love song Arthur had sung that evening on her happy lips, she went upstairs to her pretty bed-room, and was soon fast asleep and dreaming sweetly of her splendid lover.

But as for Mrs. Flint, she sat down again by the fire, in a sort of dazed condition, to think it all over.

Little Cinthia engaged to be married! Why, it was like some strange dream!

But the more she thought it over, the better pleased she was, for Cinthia’s future had been a burden to her mind, and this would be such a relief, marrying her off to such a good catch as Arthur Varian. Why, the little girl had done as well for herself as the most anxious father could desire, and she decided to give her consent to the match to-morrow without the formality of asking his advice.

Just as she came to this conclusion, she was startled again by another rat-a-tat upon the door.

“Good gracious! Who can it be knocking there at midnight almost? Some lunatic, surely! Or maybe Cinthia’s beau come back to ask for her to-night, too impatient[28] to wait for morning!” she soliloquized, as she sallied out into the hall, with the demand:

“Who’s there?”

To her utter consternation and amazement, a manly voice replied, impatiently:

“Your long-lost brother, Rebecca. Open the door. This wind is very cutting!”

Unlocking the door, a traveler stepped into the hall—a tall, brown-bearded man of perhaps forty-five, blue-eyed, and rarely handsome.

“Welcome, Everard!” she cried, and put her arm around his neck and kissed him with unwonted affection.

He had been her baby half-brother when she was married, the pet and pride of the family.

“Oh, I have such news for you! This return is very timely!” she exclaimed, when they were seated again by the fireside.

Thereupon she poured out the exciting story of his daughter’s engagement, dilating with unusual volubility on the eligibility of the suitor.

“I suppose I shall have to consent,” he said, carelessly; then: “Oh, by the way, what is the young man’s name?”

“Arthur Varian.”

The man sprung to his feet as if she had thrust a knife into his heart.

“Arthur Varian!” he repeated, trembling like a leaf in a storm, his face growing deathly white under the bronze of travel.

[29]

“Why, Everard, what is the matter? Do you know him? Is there anything wrong about him?”

“Yes, no—that is, I must see him first! Oh, Rebecca, this is a terrible thing! How fortunate that I came in time to nip this in the bud, for Arthur Varian can never marry my daughter.”

“You will break her heart.”

He dropped back into his seat, groaning:

“I can not help it, miserable man that I am; for Cinthia Dawn had better be dead than the bride of Arthur Varian!”

Everard Dawn’s words fell on his sister’s ears with a great shock, so deep was the anguish of his tone and the emotion of his face, his lips trembling under the rich brown beard, and his eyes gleaming under their heavy[30] brows like shadowed surfaces of deep blue pools, while the pallor of his face was ghastly to behold.

She studied the agitated man in wonder and terror, for he was almost like a stranger to his sister, having never met her since he was a youth of sixteen, just entering college.

Since she had married in Virginia while on a visit from her home in the far South, her communications with her relatives had been almost broken off; the death of her father soon followed her marriage, and her only visit home had been to the death-bed of her step-mother when Everard was just entering college.

She was his only near relative, and she had urged the lonely boy to visit her often, but he had never accepted the invitation but once, having to work too hard at his chosen profession—the law—to find time, he said.

Their correspondence had been infrequent, and she knew little of him, save that he had been married twice, and that on the death of his second wife he had brought her his child to raise, and gone away abruptly, a broken-hearted, lonely man.

Yet, as she looked at him sitting there, so handsome still in his young, splendid prime, with threads of premature silver creeping into the thick locks on his temples, and remembered how heavily the shadows of grief had stretched across his life, the woman’s heart was moved to pity and tenderness, such as she had felt in his babyhood[31] days, when he was the pet and darling of all. Her cold gray eyes softened with sympathy, as she cried:

“Surely, Everard, you have had more than your share of sorrow in life! What new trouble is this? For, of course, you would not oppose such a splendid match for your daughter without grave reasons.”

He lifted his heavy eyes to her troubled face, and answered, bitterly:

“Yes, I have reasons, grave and bitter reasons, for forbidding this marriage, and I thank Heaven I came in time to prevent it. But ask me nothing, Rebecca, for I shall never willingly divulge my reasons, not even to the man whom I must send away sorrowing to-morrow over a broken love-dream.”

His voice fell to exquisite pathos, as if he almost pitied the man he intended to wound so cruelly.

Mrs. Flint was disappointed, crest-fallen, she had been so elated over her niece’s prospects.

She rejoined, uneasily:

“I don’t know what Cinthy will say to this. Her heart is set on Arthur Varian. He stands for everything she longs for most, and her hatred of her life with me is intense and rebellious. You can never reconcile her to it again.”

“I must make a change in it, then, though my means are not large,” he sighed.

“So much the worse, for she loves luxury and pleasure, and her heart is almost starved for love. You know I[32] have a reserved nature, Everard, and never pet anything. I have brought her up kindly, but rigidly, and she resents my discipline and your neglect almost equally.”

“Poor girl! Perhaps she has cause. I have certainly almost forgotten her existence in these years of exile. But what alleviation was there to my misery except to forget?” he cried, passionately.

“Poor boy!” she sighed, forgetting that he was forty-five. She was twenty years older, and to her he appeared young.

He made a movement of keen self-scorn.

“I don’t deserve your pity!” he cried. “I have been a coward, shifting my burden on your shoulders, hating to come home, weary of my life. But at last the voice of duty clamored at my heart. I remembered you were growing old, and that the child was almost a woman. I came at last, but even then reluctantly. Can you ever forgive my fault?”

Many times she had said to herself, in her impatience of Cinthia’s discontent, that she could never forgive her brother for saddling her with the care of a child in her old age; but at the sight of him, so sad, so broken, so self-accusing, she could not utter the words of blame that at first had trembled on her tongue. She answered instead:

“What could you have done with a girl-child? And I was the only one you could turn to in your trouble. But I must warn you that you will not find an affectionate daughter. You have been away so long that she scarcely[33] remembers your face, and she has chafed bitterly at your neglect.”

“I suppose that is natural, and—I do not think we shall ever be very fond of each other,” he replied, with strange bitterness.

“When do you wish to see her, Everard? She is in bed now.”

“Do not disturb her sweet dreams. Our interview can easily wait till to-morrow,” he said, with strange coldness for a man whose nearest tie was this beautiful, neglected daughter.

He got up and stood with his back to the fire, his pale troubled face in shadow.

“Don’t let me keep you up longer. You look pale and tired, poor soul!” he said, kindly; adding: “Can you give me a bed, or shall I go to the hotel?”

“I can give you a room,” she answered, lighting a bedroom-candle for him and leading the way to a cozy down-stairs chamber.

“Good-night. I hope you will sleep well,” she said, leaving him to ascend to her own quarters opposite Cinthia’s own little white-hung room that she took much pains in beautifying after her girlish fancies.

She peeped in at the girl and saw that she was wrapped in pleasant dreams, for the murmured name of Arthur passed her lips, and she smiled in joy beneath the gazer’s troubled eyes.

“Poor little girl—poor little girl!” she murmured, as[34] she withdrew, her heart heavy with sympathy for the sweet love-dream so soon to be blighted by the father’s stern edict of separation.

“It is very, very, strange, the way Everard takes on about it. Why, he went wild just at the very name of Varian,” she said aloud to the large portrait of her long dead husband, Deacon Flint, good soul, that hung over her mantel. She had acquired a habit of talking absently to this portrait as if it were alive.

She read her short chapter in the Bible, mumbled over her prayer, and crept shivering into bed. But slumber was far from her eyes. The events of the evening had unstrung her nerves, and she lay awake, dreading the dawn of the morrow that was to usher in such disappointment and sorrow to the sleeping girl now dreaming so happily of the lover who was never to be her husband.

Cinthia would have slept later than usual that morning but for her aunt’s hand gently shaking her as she said:

“Get up, Cinthy. Breakfast is almost ready. Put on your Sunday gown, and try to look your best when you come down-stairs.”

“Is—is—Arthur here—already?” cried the girl, a beautiful flash of joy illuminating her face.

[35]

“Never mind about that; only come down as soon as you can, or the biscuit will be soggy,” returned the old lady, hurrying out in trepidation. The sight of the beautiful, happy face made her nervous.

Cinthia hurried her toilet, not taking time to plait her hair, but letting the bright mass fall in careless waves over the brown cloth gown—her “Sunday best.”

“How ugly it is!” she cried, with an envious glance at Mrs. Varian’s finery spread over a chair; then she sped down-stairs, wondering happily if Arthur had indeed arrived so soon to ask her aunt’s consent.

But a strange man, tall, grave, brown-bearded, stood with his back to the fire, scanning her with moody blue eyes as she fluttered in, and Aunt Beck said in nervous tones:

“Your father, Cinthy.”

“Oh!” she faltered, in more surprise than joy, and paused, irresolute.

“What a pretty girl you have grown, my dear!” said Everard Dawn, coming forward and giving her a careless kiss. Then he took her hand and seated her at the table, saying laughingly that her aunt had been fretting about the biscuits.

No emotion had been shown on either side. The man seemed indifferent, with an under-current of repressed agitation; the girl was secretly wounded and indignant. Her own father! yet he had never shown her a sign of[36] real love. Between this pair her poor heart had been starved for tenderness.

A little triumphant thought thrilled her through and through:

“What do I care for his coming or going now? I shall soon be happy with my darling!”

She was wondrously beautiful this morning, even in the plain dark gown that simply served as a foil to her fairness. Everard Dawn could not help from seeing it, and saying to himself:

“What peerless beauty! No wonder Arthur Varian lost his head!”

He felt like groaning aloud, his sudden home-coming had precipitated him into such a tragic plight, for the task that lay before him was most bitter.

He could not help from seeing the pride and resentment in her eyes, and something moved him to say, apologetically:

“I dare say you have been vexed with me for staying away so long, Cinthia; but I have been working for you, trying to lay aside a little pile, so that you could enjoy your young ladyhood. You shall have pretty gowns and pleasures henceforth. Are you not glad?”

It cost him effort to say so much, but there was no gratitude in his daughter’s proud face, only a mutinous flash of the great dark eyes as she answered:

“I shall not need your belated kindness now.”

“What do you mean?” impatiently.

[37]

“Haven’t you told him, Aunt Beck, about—about—Arthur?” blushing vividly.

“Yes—yes, dear.”

Cinthia nodded her head at him with a mixture of childish triumph and womanliness.

“You see,” she said, proudly, “I am going to be married soon. I shall have a husband who will give me all I want—even,” bitterly, “the love I have missed all my life!” tears sparkling into her eyes under the curling lashes.

He felt the keen reproach deeply, and exclaimed, gently and sadly:

“Poor little Cinthia.”

“Not poor now,” she answered, quickly. “It is rich Cinthia now—rich in Arthur’s love and the certainty of a happy future.”

She meant to be scathing, poor, neglected, wounded Cinthia, but she could never guess how the words cut into his heart and tortured him with secret agony—he who meant to lay her love and hopes in ruins, to blight all the joys of her life by the exercise of a father’s privilege of breaking her will.

But no shadow crossed his face, no trouble was apparent in his manner as he laughed easily, and answered:

“Nonsense! you are scarcely more than a child yet—too young to be dreaming of marriage. I shall send you to school to complete your education before you can begin to think of lovers.”

[38]

“I will not go!” she said rebelliously, with startled eyes upon his inscrutable face.

“Cinthy!” reproved her aunt.

“I will not go!” the girl repeated, defiantly. “I shall marry Arthur, as I promised, before Christmas!”

She sprung from her seat and rushed to the window, drumming tempestuously upon the pane, her habit when greatly excited.

Outside the prospect was dreary. The débris of yesterday’s storm littered the ground, the limbs of some of the trees hung broken, the sun was hidden under clouds that hinted at snow.

Mrs. Flint whispered to her brother, apprehensively:

“I told you so. She has a rebellious will, and she thinks you have no authority over her now, because you stayed away so long.”

“She will find out better about that before long,” he answered, decisively, though the curious paleness of last night settled again upon his handsome face.

He went over and stood by Cinthia’s side.

“It will snow before to-morrow,” he said, quietly.

“Yes;” and she looked around at him with a flushed face, crying: “Oh, papa, you were jesting?”

“No. I can not give you to Arthur Varian, Cinthia. You must forget him, my dear child.”

“I can not, will not! I should die without him!” passionately.

“No, no, you will soon get over this fancy, for you[39] have known Mr. Varian but a little time, and to-morrow I shall take you away from this place, and amid new surroundings you will forget the face that dazzled you here.”

“I will never forget Arthur, nor will I go away!” she protested.

“You can not set at naught a father’s authority, Cinthia.”

“I disclaim it, I defy it! You have given me neither love nor care, so you forfeit every right! Oh, I am sorry you ever came back here!” stormed the angry girl.

“Cinthy, Cinthy, come and help me with the work!” her aunt called, sharply; and she left him with the mien of an offended princess.

He took refuge in a cigar, and smoked moodily, till the click of the gate-latch made him look up, with a face working with emotion, at a handsome, elegantly clad young man walking up to the door.

Cinthia had gone upstairs to make the beds, and her aunt went to admit the caller.

In a minute she ushered him into the little sitting-room, saying nervously:

“Mr. Varian—my brother, Mr. Dawn.”

[40]

Arthur Varian gave a slight start of surprise as he was presented to Mr. Dawn, but the latter, more prepared for the encounter, bowed with gracious courtesy, frankly shook hands with the visitor, and pushed forward a chair.

Then they looked at each other silently a moment, and that glance prepossessed each in favor of the other—a natural sequence for Arthur, since he guessed that his new acquaintance must be Cinthia’s father.

They conversed several moments on indifferent subjects, both rather grave and constrained, with a feeling of something serious in the air, then Arthur came to the point with manly frankness:

“I have found you here most opportunely this morning, Mr. Dawn. I came to see Mrs. Flint on a particular subject, but of course you are the proper person to consult,” ingratiatingly.

“Cinthia has already told me of your suit for her hand, Mr. Varian,” gently helping him out, as if anxious for it to be over.

“You know, then, that I love your daughter—that she has promised me her hand. I can give you every assurance, sir, of my possession of those requisites every good man wishes to find in a suitor for his daughter. I am rich, of the best blood of the South, my character irreproachable. May I hope to have your approval?”

[41]

He spoke diffidently, yet eagerly and with superb manliness, his dark-blue eyes shining with hope, his cheek glowing with honest pride that he had so much to offer to the lady of his choice. Without vanity, he knew that he was, in worldly parlance, an eligible parti. No thought of refusal crossed his mind.

Yet Everard Dawn was slow in replying to what many might have considered a compliment.

His eyes rested steadily and gravely on Cinthia’s lover, while his cheek paled to an ashen hue, and the hand that rested on his knee trembled as with an ague chill.

Arthur Varian noticed these signs of deep agitation, and attributed them to parental love. He added, gently:

“It seems cruel to harass you, almost in the first moment of your return, with this matter; but it is not as if I proposed taking Cinthia away from you immediately. We had planned for a Christmas wedding.”

“This is the first of November, Mr. Varian,” he reminded him, coldly.

“Yes, sir; so it would be almost two months before I took Cinthia away,” smilingly.

“My daughter is too young to marry yet. I came home to place her at a convent school in Canada for two years, not dreaming that she had notions of lovers in her childish head,” Everard Dawn continued, gravely.

“You see, sir, we have made other plans,” said Arthur, lightly, not taking him au serieux.

To his surprise, Mr. Dawn answered, frigidly:

[42]

“Of course, those plans made without my consent do not carry.”

Arthur began to grow excited by the portentous gravity of the other. He exclaimed, almost pleadingly:

“Mr. Dawn, you do not surely mean that you will make me wait two years for Cinthia?”

And to his utter horror and despair, the gentleman replied slowly, sadly, and gravely, as if every word cost him a pang:

“No, I do not wish you to wait for Cinthia, Arthur Varian, for the truth may as well be known to you first as last, cruel as it must seem at first. Believe me, I am sorry for your disappointment, and I hope your fancy for Cinthia has not taken very deep root, for—she can never be your wife.”

“Mr. Dawn!”

Arthur Varian sprung to his feet, and faced the speaker, with such a grief and amazement on his handsome face as might have melted the sternest heart.

“Mr. Dawn, you can not surely mean this refusal! What reasons could exist for deliberately wrecking two fond, loving hearts?”

“Unfortunately, the reasons exist; but such as they are, I can not explain them, Mr. Varian.”

Arthur cried out, eagerly:

“If you are offended at my impatience to claim Cinthia for my own, I will agree to wait the two years you mentioned, or even more. Nay, so deep and constant is[43] my love, that I would rather serve seven years for her, as Jacob did for Rachel, than lose the dear hope of winning her at last for my own.”

Everard Dawn rose from his chair, and grasping the back, to still the great trembling of his frame, answered, with passionate energy:

“Arthur Varian, there can never be a marriage between you and my daughter. The fates forbid it, the unknown forces that control your life and hers cry out upon it. You must forget each other, for your love is the most ill-fated and hopeless the world ever knew. Arguments and entreaties are alike useless. You will believe that I am in terrible earnest when I tell you that I would sooner see my daughter dead than give her to you as a bride.”

“This is strange—passing strange, Mr. Dawn,” the young man uttered, indignantly, yet still not as angrily as might have been expected.

A subtle something about the man, with his grave, sad, handsome visage, claimed his respectful admiration, in spite of the mystery that surrounded his rejection of his daughter’s suitor.

“It is strange, but true,” answered Everard Dawn, wearily; and he added: “Do not let us prolong this most painful conversation. Nothing can change the decrees of relentless fate.”

Arthur felt himself politely dismissed, and turned toward the door.

[44]

“You will at least permit me a parting interview with Cinthia?” he murmured.

“You must forego it. It is better so. To-morrow she leaves this place with me forever. Your two lives must never cross again!”

With a heart full of pain, and anger, and silent rebellion, the young man bowed, and walked out of the house; but ere he reached the gate, he heard flying footsteps behind him, and turned to greet Cinthia, bareheaded and breathless, her cheeks pale, the tears hanging on the curly fringe of her dark lashes.

She clasped her tiny hands around his arm, reckless of her father’s eyes watching disapprovingly from the window, and murmured:

“Well?”

“He refuses his consent, Cinthia, and says he will take you away to-morrow where we shall never meet again.”

“Arthur, you will never let him do it; you will not forsake me if you love me!” wildly, passionately.

“My darling, you know I can not live without you! Would you elope with me?”

“Yes, yes!” she began, eagerly; but just then her father appeared at the door.

“Cinthia, you must come in out of the cold!” he called, sternly; and Arthur said:

“Go, my darling!”

[45]

Cinthia did not obey. She only clung closer to her sorrowing lover.

“Oh, Arthur, don’t leave me! Take me home with you to your sweet, kind mother! I hate that man!” she sobbed in wild abandon.

Her father came down the walk toward them, and Arthur bent and whispered rapidly in her ear:

“Go in with him now, my own sweet love, for we can not defy him openly, we can only defeat him by strategy. Be brave, darling, for—I will come for you and take you away to-night.”

He kissed her, in spite of Mr. Dawn’s great eyes, and pushed her from him with gentle violence just as her father came out and took her hand.

“Come, Cinthia,” he said, with gentle firmness, and she followed, though she shook off his touch as though it had been a viper.

“Don’t touch me! I hate you—hate you!” she cried, like a little fury, her eyes flashing fire. “Do you think I will go with you to-morrow? Never—never! You have made my life empty of joy, and now you envy the sunshine that love has brought me! But you shall not part me from Arthur—no, no, no!” and desperately sobbing, she flung herself face downward on the floor.

[46]

He sought Mrs. Flint in terrible perturbation.

“Come, she is in hysterics!” he exclaimed, anxiously.

“I told you it would go hard with Cinthy,” she answered, curtly.

“Yes, I feared she would grieve; but, good Heaven! she is a little fury—all rage and rebellion, swearing she will not go with me to-morrow. She must be closely watched to-day, for there is no telling what such a desperate girl may do,” he said in alarm mixed with anger.

“Pshaw! she will simmer down when her fit of crying is over. I’ll get her upstairs and give her a soothing dose. Her temper-fits never last long, for Cinthy is a good child, after all, and I am sorry over her disappointment, she sets such store by love,” returned the old woman, in real sympathy for the girl and secret disapproval of his cold attitude to his neglected daughter.

He felt the implied reproach and answered, in weary self-excuse:

“Rebecca, I know you think me hard and cold, but my heart seems dead within me.”

“That is no excuse for neglect of duty,” she answered with telling effect as she went to the difficult task of soothing Cinthia and getting her upstairs to her room.

“A bitter home-coming!” he muttered, as he went out into the bleak morning air, with its scurrying flakes of threatening snow, to try to walk off some of his perturbation.

[47]

Somehow the dreary day dragged through to the drearier late afternoon.

Upstairs, Cinthia lay still and exhausted upon the bed after such a day of tears, and sobs, and passionate rebellion as Mrs. Flint hoped never to go through again.

Everard Dawn took his hat and great-coat, and set out for another long walk—this time in the direction of Arthur Varian’s home.

Had he repented his harshness? Was he going to recall Cinthia’s banished lover?

The air was keen with a biting east wind, the sky was gray with threatening clouds, and occasional light scurries of snow flew in his face and flecked his thick brown beard as he stepped briskly along, gazing over the low evergreen hedge at the beautiful grounds of the fine old estate he had refused for his daughter.

As he almost paused in his walk to gaze with deep interest at the picturesque old stone house, he saw a lady come out of a side-door and turn into an avenue of tall dark cedars that made a pleasant promenade, shutting off the rigorous wind very effectively.

He followed her progress with wistful eyes and tense lips.

It was indeed the stately mistress of the mansion. Wearying of its warmth and luxury, she had come out, wrapped in sealskin, for her favorite constitutional along the cedar avenue.

She walked slowly, with her hands behind her, and[48] her large, flashing dark eyes bent on the ground, as if in profound thought.

Everard Dawn gazed eagerly after Mrs. Varian till she was lost to view among the cedars, then, searching for a gate in the hedge, he entered and turned his steps toward the avenue, so as to meet her on her lonely walk.

Slowly they came on toward each other, the echo of their footsteps dulled by the carpet of dead leaves, dank and sodden with last night’s rain, and the face of the man, with its gleaming eyes and deep pallor, bore signs of unusual agitation.

Suddenly the lowering clouds parted, and a dull sunset glow sent gleams of light down through the cedar boughs upon the sodden path. The woman lifted her large, passionate orbs to the sky.

Then she stopped short and uttered a startled cry.

She had caught sight of the advancing man, the intruder upon her grounds.

He removed his hat and stood bowing before her in the dying sunset glow, the light shining on his pallid face and the streaks of gray in his thick locks.

“Mrs. Varian!” he exclaimed.

“Everard Dawn!” she answered, in a hollow voice, and her eyes glowed like live coals among dead embers, so ashy-pale was her beautiful face.

Pressing her gloved hand upon her side, as if her heart’s wild throbbings threatened to suffocate her, she called, hoarsely:

[49]

“Why are you here? How dare you face me, traitor?”

“I have not come to forgive you, Mrs. Varian, be sure of that!” he answered, sternly.

“You do well to talk of forgiveness—you!” she sneered, stamping the ground with her dainty foot.

“And—you—madame—would—do—well to crave it—not that it would ever be granted you, remember. Only angels could forgive injuries like mine!” the man answered, stormily, with upraised hand, as if longing to strike her down in her defiant beauty.

She did not shrink nor blanch, but her face was a picture of emotional rage, dead white against the setting of satin-black tresses and rich seal fur, her eyes flashing as only great oriental black eyes can flash, and her rare beauty of form showing to advantage as she drew herself haughtily erect, hissing out:

“Go, Everard Dawn! Take your hated form from my sight ere I summon my servants to drive you from the grounds!”

Turning, as if to put her threat into execution, she was arrested by a stern voice that said significantly:

“It is more to your interest to listen to me one moment, Mrs. Varian.”

She whirled back toward him again, saying, imperiously:

“Be brief, then, Everard Dawn, for you should know[50] that it suffocates me to breathe the same air with such as you!”

Evidently there was some strange secret between this haughty pair, for he flashed her a glance of kindling scorn, as he returned:

“What I have to say needs but one sentence to assure you of its importance. Your son, Mrs. Varian, wishes to wed—my daughter!”

A hoarse, strangled cry, and she fell back against the trunk of a tree, clasping its great bole, as if to prevent herself from falling. Her face wore such a look of agony as if he had plunged a knife into her heart.

Everard Dawn impetuously started forward, as if to catch her in his arms—the natural impulse of manhood at seeing a woman suffer.

Then he suddenly remembered himself, and drew haughtily back, waiting for her to speak again; but she was silent several moments, gazing at him with the reproachful eyes of a wounded animal at bay.

Then she gasped, faintly:

“Is she—is she—that Cinthia Dawn?”

“Yes. Cinthia Dawn is my daughter,” finishing the unended sentence. “She lives here with my sister, and I came home last night, after being self-exiled for weary years, and found Arthur Varian and Cinthia plighted lovers. I have forbidden their love, and sent him away; but they are defiant and rebellious. I shall take her away[51] to-morrow—but in the meantime I came to you, for you must help me to keep them apart.”

“I—oh, Heaven! what is there I can do?” she moaned, in piteous distress.

He looked at her in dead silence a moment, then answered, firmly:

“Cinthia is only a tender girl, and I will not have her young life blasted with the hideous truth. Arthur is a man, and if the dark secret that comes between their love must ever be divulged, it is to him alone it need be revealed. Will you charge yourself with this duty should he persist in his resolve to marry Cinthia?”

“If you asked me for all my fortune, I would rather give it you—but you are right. The duty is mine. I will not shirk it, though it slay me. Poor, poor Arthur!”

“That is well. I shall depend on you to curb his passion. Farewell, Mrs. Varian;” and with a lingering glance, he turned away just as the last sun-ray glimmered and faded in the west.

Cinthia had never spent such an unhappy day in the whole of her young life. She could not realize that only yesterday she had been railing at the monotony of existence.

[52]

It was only twenty-four hours later, and a tragedy of woe had overwhelmed her in its grim embrace.

Only yesterday she had been planning, and hoping, and wishing for some way to know Arthur Varian better, and now he was won, now he was her promised husband; and through all the bitterness of her father’s cruelty, that thought made glad her warm heart.

She had shed little rivers of tears, she had sulked at her father and aunt, she had refused to eat her dinner, and pouted among the pillows all day long; but through it all ran one thrilling thought, Arthur was coming to take her away to-night. He had promised, and she knew he would keep his word.

When her aunt went down about her household duties, she laughed to herself at the thought of outwitting those two—her cold-hearted aunt and her cruel father. The thought of their surprise, when they should find her gone in the morning was pure delight.

“There he goes now. I wish he would go and stay forever!” she cried, petulantly, as she heard the gate-latch click, and springing to the window, saw her father walking away into the gloomy distance.

She sat down and watched him out of sight, adding:

“He is very handsome and noble looking, and if he had treated me better, I should have learned to love him well. But now I hate and fear him, and I would die before I would go with him to-morrow. Dear,[53] dear Arthur, I hope nothing will prevent him from taking me away to-night.”

And while she was moping, her aunt came up with a magnificent bunch of roses, saying kindly:

“Cheer up now, Cinthy! Here’s a splendid big nosegay for you, and a box of French candy. I ’spose your pa sent it, because he went down into the town a while ago, and said he’d get you a present.”

“I don’t want any of his presents! Take them away!” Cinthia answered, angrily.

“Don’t be a little fool, Cinthy. I’m getting out of patience with your airs,” Mrs. Flint returned, severely, putting down the gifts and slamming the door as she stalked out.

Cinthia loved flowers dearly, and the scent of the roses wooed her to caress them presently, burying her face in the fragrant red and white beauties.

A note hidden among them scratched the tip of her nose, and she drew it out with a cry of wonder.

It was from Arthur Varian, and ran thus:

“I have thought it all over, darling, and I think the only way for us is to elope to Washington to-night and be married. I do not like to steal a man’s daughter away from him this way, but his obstinacy leaves us no other hope, and as there is really no reason to prevent our marrying, I hope he will soon be reconciled. No doubt, mother will help us to bring him around afterward, she is so very clever. And I shall not let her into the secret of to-night, so that he can not accuse her of connivance[54] in our plans. I will be waiting near your house with a carriage at twelve o’clock to-night, and you must slip out and join me. Then it is only two miles to the station, and away we go on the midnight train to Washington. Keep up your courage, my sweet love, for we are going to be the happiest pair in the world.

“Arthur.”

Cinthia refused to go down to supper, and made a meal of sweetmeats. The hours between dark and midnight seemed endless. She heard her aunt retire to her room at an early hour, and her father later on. The house was wrapped for an hour in profound silence, then she heard the hall-clock chiming twelve.

Cinthia was all ready, even to her hat and jacket, her face pale with eagerness, her heart throbbing wildly. She stepped to the door and turned the knob. Horrors! it did not yield to her touch. They had suspected her and locked her into the room.

An impulse came to her to shriek aloud in her wrath and defiance, and to try and batter down the door and escape; but a timely thought restrained her, and she drew back from the temptation, her eyes flaming luridly, her temper raging.

“They shall not baffle us, the cunning wretches! Arthur, my love, I am coming to you, though the whole world oppose!” she cried, wildly, rushing to the window and throwing up the sash.

It had been snowing steadily for hours, though she[55] did not know it. As she leaned out into the darkness a great gust of wind and big swirling flakes of snow stormed into the room, blowing out the light and clasping her in a cold embrace.

The night was black as Erebus, the wind cut like a knife, and the air was full of blinding snow that must have been falling for hours, it was banked so heavily against the window-ledge, almost freezing Cinthia’s hands as they plunged into it on leaning forward, for though she gasped and caught her breath as the wild elements blew in her face and tried to beat her back, she did not recoil from her fixed purpose, which was to drop out upon the top of the porch and climb down to the ground by the aid of a honeysuckle vine that wreathed over the trellis frame at one end. The icy blast that shrieked in her ears was not enough to chill the fiery ardor of her resentment at her father, and the yearning of her heart[56] for the dear lover from whom she feared to be separated forever.

Her tender young heart went out to him with an intensity of feeling as she peered out into the stormy darkness of the night, wondering if he was there waiting, and if he was growing impatient at her delay.

“Ah, my love,” she murmured, impetuously, “I am coming to you—coming! Neither bolts nor bars, nor storm nor darkness, nor anything under Heaven, shall keep us apart!”

The wind whistled past the eaves and seemed to take on an almost human voice of sorrowing, as though it echoed those dismal words: “Shall keep us apart, shall keep us apart!”

Cinthia caught her breath and listened, it was so strange, that almost human wail of the wind sighing through the great pine tree on the corner. It seemed to be sobbing: “Apart, apart!”

“How mournful it sounds!” she uttered, in an awe-stricken tone; then she climbed through the window and dropped with a dull thud out on the porch. Mrs. Flint heard the sound in her adjoining room, and muttered, drowsily:

“It is the snow sliding down from off the roof.”

Cinthia crawled to edge of the porch, and felt out carefully for the thick mat of the honeysuckle.

She knew she was making a desperate venture, but she[57] said to herself, bitterly, that desperate emergencies require desperate remedies.

With infinite care and patience she managed to get hold of the strong matted vines, and swung herself carefully over the trellis, beginning to make the perilous descent with bated breath, for a fall might mean a broken limb, or, at the least, a sprained ankle.

The wet snow clung to her face and garments and chilled her to the bone; but she persevered, though the high wind threatened to loosen her hold and blow her down every instant. What did she care for it all, poor Cinthia fleeing from her dull life and her hated persecutors to the tender arms of love? She would endure anything rather than be cheated of her happiness.

The cold snow flecked her benumbed face and hands, the high wind swung her light form to and fro like a flower upon the vine, her breath seemed to freeze on her lips, but her courage never flagged. Out there in the night and the storm her lover was waiting. The thought kept her young heart warm.

She was more than half-way down now, and the wind began to lull. Courage, Cinthia; the danger will soon be over, sweetheart, and love rewarded for its brave struggles.

But, alas! how often bathos overcomes pathos.

Cinthia was only a girl, after all, with the usual feminine attributes.

As she swung herself carefully from branch to branch[58] of the vine, hoping and longing for her feet to touch terra firma, yet sustained by unfaltering courage, there came to her a sudden wild and terrifying thought that made the blood run colder in her veins than all the raging storm had force to do.

She had remembered that of late the immense vine to which she clung had afforded a delightful gymnasium for a score or so of large rodents, causing her aunt to threaten to cut it down.

The feminine mind has one idiosyncrasy known of all men, and accordingly ridiculed, but never overcome. Cinthia did not pretend to be stronger than her sex. With that sudden terrifying thought an uncontrollable shriek burst from her lips, her numb hands relaxed their grasp, and she went crashing down through space plump into a great, great bank of drifted snow blown into a heap below the vine.

Everard Dawn heard that shriek as he tossed on his pillow in restless dreams, and suddenly raised his head.

“What a night!” he cried, for he had been watching the storm ere he retired. “How the wind howls to-night, shrieking like a human voice through that splendid pine on the corner! How I used to love the wind in the pines in my far Southern home until—afterward! But since then it is an embodied grief to me, as in the plaint of one of our Southern poets:

[59]

He listened with his head on his arm but the wind had lulled for the moment, and the strangely human shriek he had heard began to affect him very unpleasantly.

“Was it really the wind?” he began to ask himself, wondering if it might not be an hysterical shriek of his rebellious daughter.

“Poor little Cinthia, God help her!” he uttered, sadly, and rising from his bed, began to dress hurriedly. “I will go and see if there is anything wrong,” he muttered.

He had been very angry when he returned at dusk from his strange interview with the scornful Mrs. Varian, and heard from his worried sister about the flowers and candy she had taken up to Cinthia.

“How is my little girl now?” he asked, anxiously, and started when she replied:

“She is in a dreadful temper, and when I took up the flowers and candy you sent her, she ordered me to throw them away.”

“Did you do it?”

“No; I told her not to be a little fool, put them down on the table, and came away.”

[60]

“Rebecca, I fear you have made a grave mistake. I did not send Cinthia anything. I intended to purchase a gift for her, but—I was—so troubled—I quite forgot it.”

Mrs. Flint studied a moment, then frankly admitted that the boy who brought the flowers had not said Mr. Dawn sent them, in fact, had merely said, “For Miss Cinthia,” and she had jumped at the conclusion that they came from her brother.

“They must have come from Arthur Varian. I take this very ill of him after what I said to him this morning,” angrily. “Are you sure,” he continued, “that no letter accompanied the flowers?”

“I did not see any,” the old lady replied, uneasily.

Everard Dawn was more versed in the ways of romantic lovers than his prosaic sister, so he said, with a troubled air:

“You may be sure that a sentimental note accompanied the gift, and they may possibly have planned an elopement this very night. I desire that you will lock her door on the outside without her knowledge when you retire to-night.”

“Very well,” she replied, and obeyed him to the letter.

Recalling all this, the thought came to him that perhaps Cinthia, finding her door locked, was indulging herself in a fit of hysterics.

“God help us all,” he sighed, as he finished dressing; and, taking his night-lamp, stole upstairs to listen outside her door.

[61]

But all was still as death at first, then the wind rose again, and he heard strange noises within the room. It was, in fact, the wind rushing through the window and banging things about in confusion.

He went and tapped on Mrs. Flint’s door, and she soon confronted him in her cap and gown, exclaiming:

“I thought I heard creaking steps in the hall. What is the matter? Are you ill, Everard?”

“No; but I fancied I heard strange noises from Cinthia’s room. Did you notice anything?”

“I heard the snow sliding off the roof, and the wind shrieking in the branches of that great pine out there. It always sounds so human in a storm, that I would cut it down only that Deacon Flint set store by it. He said he planted it when he was a little boy. But I will go in and peep at Cinthia just to ease your mind, Everard. ’Sh-h! we must not wake her if she is asleep,” turning the knob with a cautious hand and opening wide the door.

Whew! how the cold air rushed in her face and thrust her back. By the light that Everard carried she saw the window wide open and the snow-flakes flying in on the carpet.

“Why, how strange that the window should be open. Cinthia must be crazy. Wait till I shut it, Everard, and bring in the light,” she ejaculated.

He obeyed, and when he entered, they saw what had happened. The room was empty and Cinthia was gone.

Mrs. Flint could not believe it at first. She ran all[62] about the room, and then all over the house, crying in wild dismay:

“Cinthia! Cinthia! Cinthia! where are you hiding, honey?”

But no reply came back, and very soon the unhappy father found out the truth. She had actually escaped by way of the window. Securing a lantern from the kitchen, he went out for a short while, and returned with a very accurate report.

She had slid down the honeysuckle vine to the ground, and there were tracks in the snow leading to a sleigh that had been in waiting not far away. The marks of the runners were quite distinct, in spite of the drifting snow.

“She has eloped with Arthur Varian. I must follow and bring them back,” he said, with terrible calmness.

“Yes, for I found the letter that must have come with the flowers blowing about the floor of her room,” she answered, giving it to him.

He read it, groaned bitterly, and thrust it into his pocket.

“I must pursue them,” he said again. “Tell me where to find the nearest livery stable, Rebecca.”

“It is half a mile,” she said, giving him clear directions, but adding: “Oh, Everard, you will not venture out in such a storm. You may catch your death of cold!”

“You know not what you talk of, my sister. I would rather catch my death, as you say, than permit Arthur Varian to marry Cinthia Dawn!” he hurled back at her,[63] hoarsely, as he rushed from the house out into the night and storm.

Meanwhile Cinthia’s fall and shriek had been heard by other alert ears—no less than Arthur Varian’s, who had been waiting impatiently in the shadow of the trees for ten minutes, wondering whether Cinthia would come or not, fearing lest the fury of the storm should daunt her courage and hold her back.

With his eager eyes on her window, he presently saw the sash fly up and Cinthia’s beautiful face and form outlined against the background of the lighted room. The next moment the gale blew in and extinguished the lamp and darkened the beautiful picture.

But in that moment he saw enough to relieve his fears. Cinthia wore her hat and jacket ready for traveling. She was coming to him, his brave little darling, and out yonder waited a swift horse and sleigh, and plenty of cozy buffalo robes to shelter her from the cold in their swift drive to the station.

He advanced to the gate and stood with his eyes fixed on the door, eager to give her a joyous welcome when she appeared, lest the thick darkness frighten her back.

[64]

Then his ears caught the soft thud on the top of the porch, and, like Mrs. Flint, he thought at first it might be snow sliding off the roof.

The wind arose with a great bang and clatter among the loose shutters, deadening the sound of the branches as Cinthia swung herself off the vine and began her descent to the ground, while her eager lover strained his eyes through the thick darkness, watching the door to see her come.

Then suddenly the wind lulled so that he could catch his breath, and he heard a soft rustling in the vines, as if they strained under a dead weight.

“Heavens! what is that?” he muttered, with a half suspicion of the truth; and, tearing open the gate, he rushed across the yard through the wet, impeding snow, already half a foot deep, to the corner of the house just as Cinthia shrieked and fell into the little bank of drifted snow so soft and cold.

With a bound, Arthur was by her side, stretching out eager hands, crying, in a passion of love and grief:

“Cinthia, dearest, are you hurt?”

He reached down and gathered her up like a child in his strong arms.

“Oh, my love—my treasure! What a terrible risk you ran for me! Tell me if you are hurt!”

She whispered nervously against his breast:

“I don’t think I am, only frightened almost to death. I thought—thought—every bone—would be broken—but[65] the snow was as soft as a feather bed! Oh, let us get away, Arthur, before they hear us! You may carry me if you will—I am trembling so,” her teeth chattering so that she could scarcely speak.

“That’s what I meant to do,” Arthur replied, managing to find her face somehow in the darkness and imprint a kiss upon it ere he strode away with her to the sleigh, and tucked her in among the robes so that not a breath of cold could reach her, while he kept up her courage with the tenderest words, assuring her that she should never repent trusting herself to him.

“Oh, how dark it is! How shall you find your way along the dark country road?” she cried in alarm.