THE MILLS OF THE GODS SET UP IN THE NORTHERN FASTNESS GRIND OUT PERIL AND LOYALTY, FEAR AND COURAGE—AND THE TESTS THAT ARE TO TRY THE SOULS OF THOSE WHOSE DESTINY CALLS THEM TO THE LAND OF FROST AND GOLD.

He threw back his head and howled eerily. His muzzle lifted to the stars and the most mournful sound known to man poured from his throat and was echoed and reëchoed by the hooded cedars and the rocks about him. He could not have told you why he howled. Dogs are not prone to introspection. But he knew that his master, who should be in the cabin yonder, would never come out again. He knew that the dying wisps of smoke from the chimney would never billow out in thick gray clouds again. And he knew that the other man—who had come out so hastily and gone swinging down the river trail—would never, never return.

Cheechako was chained. It had originally been a mark of disgrace, an unbearable humiliation to a malamute pup, but he did not mind it any longer. His master had made sleeping quarters for him that were vastly warmer than a snow-bed even in the coldest weather, and Cheechako wholeheartedly approved. He was comfortable, he was fed, and Carson released him now and then to stretch his legs and swore at him affectionately from time to time, and no reasonable dog will demand any more. Or so Cheechako viewed it, anyhow.

But now his muzzle tilted up. His eyes half-closed, and from his throat those desolate and despairing howls poured forth. A-a-o-oooo-e-e! A-a-o-oooo-e-e! They were a dirge and a lament. They were sounds of grief and they were noises of despair. Cheechako could not explain their meaning at all, but when a man dies they spring full-bodied from that man’s dog’s throat.

The hooded cedars watched, and echoed back the sound. The rocks about him watched, and gave tongue stilly in a faint reflection of his sorrow. The river listened, and babbled absently of sympathy and rippled on. The river has seen too many men die to be disturbed. The wilds listened. For many miles around the despairing, grief-stricken howling reached. To tree and forest, and hill and valley, the thin and muted wailing bore its message. Only the cabin seemed indifferent, though the tragedy was within it. Somewhere within the four log walls Carson lay sprawled out. Cheechako knew that he was dead without knowing how he knew. There had been a shot. Later, the other man had come out hastily with a pack on his back. He had taken the river trail and disappeared.

And long into the night, until the pale moonlight faded and died, Cheechako howled his sorrow for a thing he did not understand. Of his own predicament, the dog had yet no knowledge. It was natural to be chained. Food was brought when one was chained. That there was now no one to bring him food, that no one was likely to come, and that the most pertinacious of puppy teeth could not work through the chain that bound him; these things did not disturb him. His head thrown back, his eyes half-closed, he howled in an ecstasy of grief.

And while he gave vent to his sorrow in the immemorable tradition of his race, a faint rumbling set up afar off in the wilds. It was hardly more than a murmur, and maybe it was the wind among the trees. Maybe it was a minor landslide in the hills not so many miles away—a few hundred tons of earth and stone that plunged downward when the thaw of spring released its keystone. Maybe it was any one of any number of things, even a giant spruce tree crashing thunderously to the ground. But it lasted a little too long for any such simple explanation. If one were inclined to be fanciful, one would say it was the mill of one of the forest gods, grinding the grist of men’s destinies, and set going now by the murder of which Cheechako howled.

Certainly many unrelated things began to happen which bore obscurely upon that killing. The man who had fled down-river reflected on his cleverness and grinned to himself. He opened thick sausage-like bags and ran his fingers through shining yellow dust. Remembering his security against detection or punishment, he laughed cacklingly.

And very far away—away down in Seattle—Bob Holliday found courage to ask a girl to marry him, and promised to go back to Alaska only long enough to gather together what capital he had accumulated, when they would be married. Most of what he owned, he told her, was in a placer claim that he and Sam Carson worked together. He would sell out to Sam and return. But he would not take her back to the hardships he had endured. He was filled with a fierce desire to shield and protect her. That meant money, Outside, of course. And he started north eagerly for the results of many years’ suffering and work, which Sam Carson was guarding for him.

And again, in a dingy small building a sleepy mail clerk discovered a letter that had slipped behind account-books and been hidden for months on end. He canceled its stamp and dropped it into a mail bag to go to its proper destination.

Then, the rumbling murmur which might have been the mill of a forest god off in the wilds stopped abruptly. The grist had had its first grinding.

But the mill was not put away. Oh, no. Cheechako howled on until the moonlight paled and day came again. And the letter that had lain so long was dropped into a canoe and floated down to the coast in charge of a half-breed paddleman. And Bob Holliday sped north for Alaska and his partner, Sam Carson, who guarded a small fortune that Holliday had earned in sweat and agony and fierce battle with the wilds and winter snows. Holliday was very happy. The money his partner held for him would mean comforts and even luxuries for the girl he loved.

The mill of the forest god was simply laid aside for a little while. They grind, not slowly—these mills of the gods—but very swiftly, more swiftly than the grist can come to their grinding stones. Now and then they are forced to wait for more. But everything upon the earth comes to them some time. High ambitions and most base desires, and women’s laughter and red blood gushing, and all hopes and fears and lusts and terrors together disappear between the millstones and come out transformed into the product that the gods desire.

The mill was merely waiting.

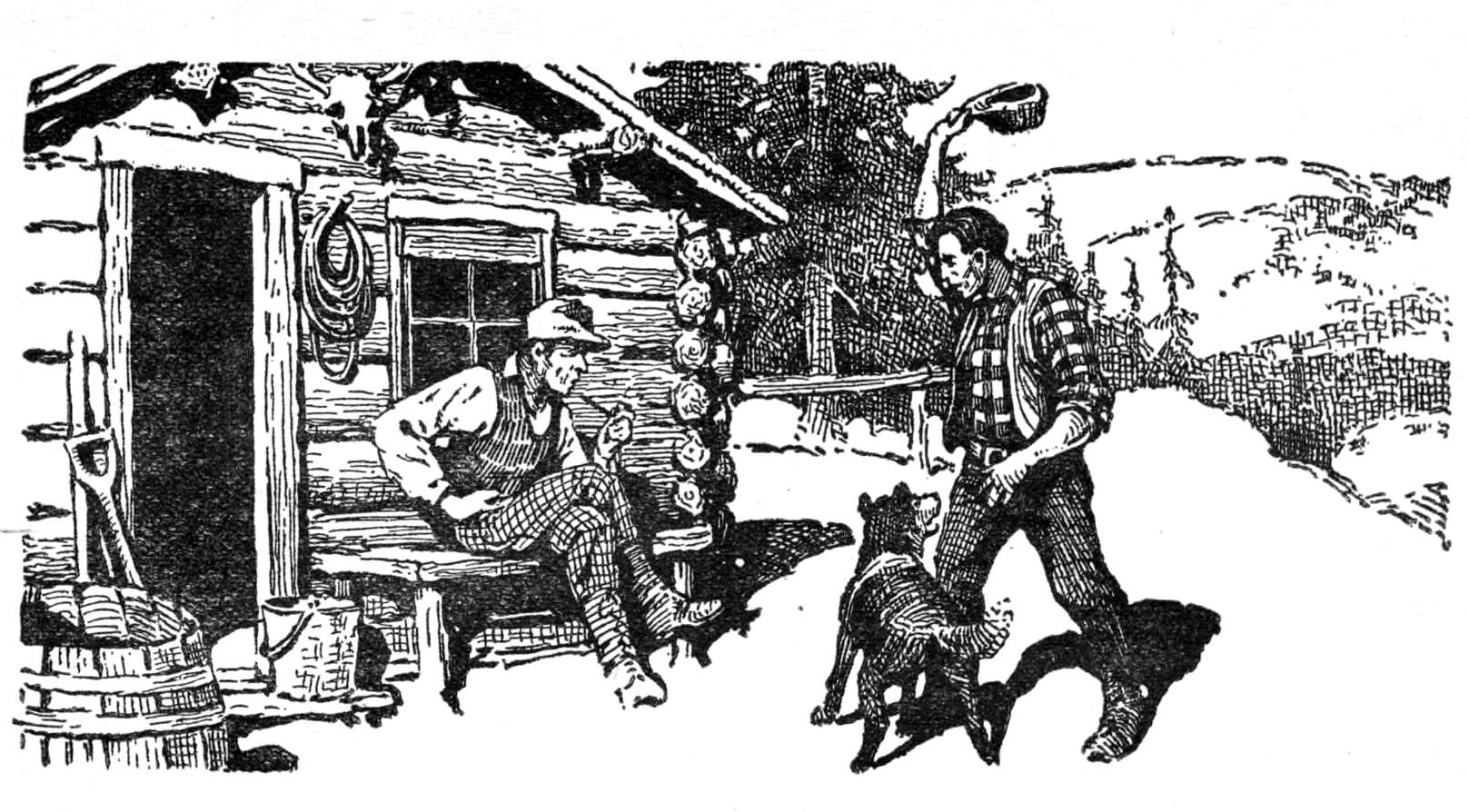

The place had that indefinable air of desertion that comes upon a wilderness cabin in such an amazingly short time. The wood-pile, huge, yet clearly but the remnant of a winter’s supply, had not yet sprouted any of the mosses and lichens that multiply on dead wood in the short Alaskan summer. The axe, even, was leaned against the door. Chips still rested on blades of the quickly-growing grass that comes before the snow has vanished. A pipe rested on a bench before the house. But the place was deserted. The feel of emptiness was in the air.

Holliday had drawn in his breath for a shout to announce his coming when the curious desolation all about struck home. It was almost like a blow. Every sign and symbol of occupancy. Every possible indication that the place was what it seemed to be—the winter quarters of an old-timer thriftily remaining near his claim. And then, suddenly, the feeling of emptiness that was like death.

He disembarked in silence, his forehead creased in a quick and puzzled frown. He was walking swiftly when he climbed the bluff, glancing sharply here and there. A sudden cold apprehension made him hesitate. Then he shook himself impatiently and moved more quickly still.

Within ten yards of the door he stopped stock-still. And then he fairly rushed for the cabin and plunged within.

It was a long time later that he came out. He was very pale, and looked like a man who has been shaken to the core. He was swearing brokenly. Then he made himself stop and sit down. With shaking fingers he filled his pipe and lighted it.

“In his bunk,” he said evenly to the universe. “A bullet through his head. No sign of a fight. It isn’t credible—but there isn’t a sign of any dust or any supplies, and somebody else had been bunking in there with him. Murder, of course.”

He smoked. Presently he got up and found a path which he followed. At its end he saw what he was looking for. He poked about the cradle there, and expertly fingered the heap of gravel that had been thawed and dug out to be washed when summer came again.

“He’d cleaned up,” he said evenly. “He must have had a lot of dust, and the man with him knew it. I’ve got to find that man.”

His hands clenched and unclenched as he went back toward the cabin. Then he calmed himself again. His eyes searched for a suitable spot for the thing he had to do.

And then, quite suddenly, “My God!” said Holliday.

It was Cheechako, who had dragged himself to the limit of his chain and with his last atom of strength managed to whimper faintly. Cheechako was not pretty to look at. It had been a very long time since the night that he howled to the stars of his grief for the man who was dead. And he had been chained fast. Cheechako was alive, and that was all.

He lay on the ground, looking up with agonized, pitiful eyes. Holliday stared down at him and reached for his gun in sheer mercy. Then his eyes hardened.

“No-o-o. I guess not. You’ll be Sam’s dog. You’ll have to stay alive a while yet. Maybe you can pick out his murderer for me.”

He unbuckled the collar that Cheechako’s most frenzied efforts had not enabled him to reach, and took the mass of skin and boniness beneath down toward his canoe. With a face like stone he tended Cheechako with infinite gentleness.

And that night he left Cheechako wrapped up in his own blankets while he carved deeply upon a crudely fashioned wooden cross. His expression frightened Cheechako a little, but the dog lay huddled in the blankets and gazed at him hungrily. Cheechako hoped desperately that this man would be his master hereafter. Only, he also hoped desperately that he would never, never use a chain.

Cheechako learned much and forgot a little in the weeks that followed. When he could stand on his wabbling paws, Holliday took him off invalid’s diet and fed him more naturally canine dishes—the perpetual dried or frozen fish of the dog-teams, for instance. Cheechako wolfed it as he wolfed everything else, and in that connection learned a lesson. Once in his eagerness he leaped up to snatch it from Holliday’s hand. His snapping teeth closed on empty air, and he was soundly thrashed for the effort. Later, he learned not to snarl or snap if his food was taken squarely from between his teeth. When he had mastered that, he was tamed. He understood that he was not to try to bite Holliday under any circumstances whatever. And when he had mastered the idea he was almost pitifully anxious to prove his loyalty to Holliday. The only thing was that in learning that he got it into his head that he was not to snarl at or try to sink his teeth in any man.

That was possibly why Holliday was disappointed when he took the dog grimly downstream and made his inquiries as to who had come down in the two weeks after Carson’s murder. He found the names of every arrival, and he grimly pursued every one who might have been the man he was looking for. Each one had a plausible tale to tell. Most of them were known and could prove their whereabouts at the time of Carson’s death. But enough had trapped or wintered inland near their claims to make the absence of any explanation at all no proof of guilt. That was where Cheechako was to come in.

Always, before his grim interrogation was over, Holliday unobtrusively allowed Cheechako to draw near. Cheechako had known the man who had been with Carson when he was murdered. Holliday watched him closely. He would sniff at the man, glance up at his master, and wag his tail placatingly. Holliday watched for some sign of recognition. Cheechako grew to consider it a part of the greeting of every man his master met. That was the difference between them. Cheechako simply did not understand. He had already forgotten a great deal of what had happened to him, and Holliday was his master now. Carson was a dim and misty figure of the past.

By the time Holliday actually came upon the man of whom he was in search, Cheechako considered the little ceremony a part of the scheme of things, not to be deviated from.

They found him camping alone, after trailing him for two days.

“Howdy,” said he, looking up from his fire with its sizzling pan of beans and bacon.

“Howdy,” said Holliday curtly. “You came down-river about a month ago?”

The man bent forward over his fire. Cheechako, watching patiently, saw his whole figure stiffen.

“I come down, yes,” said the camper, stirring his beans. Sweat came out on his forehead, but he made no movement toward a weapon. He was not the sort to fight anything out.

“Know Sam Carson?” demanded Holliday.

“Hm—” said the camper. “Seems like I knew him once in Nome.”

His eyes rested on Cheechako, and flicked away. Cheechako knew that he was recognized and he wagged his tail tentatively, but he had changed allegiance now. He waited to see what Holliday would do.

“Stop at his cabin?” demanded Holliday grimly.

“Nope,” said the camper. “What’s up?”

“Pup!” said Holliday.

This was Cheechako’s cue. Holliday did not know what Carson had called him, and “Pup” had been a substitute. Knowing, then, what Holliday expected of him and anxious to do nothing of which his master would not approve, Cheechako went forward and sniffed politely at the man’s legs. He rather expected some sign of recognition. When it came, Cheechako would respond as cordially as was consonant in a dog who belonged to someone else. But the man who had stayed with Carson made no move whatever, though his smell to Cheechako was the smell of a thing in deadly fear.

Cheechako glanced up at Holliday, and wagged his tail placatingly.

“He don’t seem to know you,” said Holliday grimly. “I guess you didn’t.”

They camped with the stranger, then, and he told Holliday that his name was Dugan and that he was a placer man, and told stories at which Holliday unbent enough to smile faintly.

Holliday was grim and silent, these days, because he had a man-hunt on his hands, and the gold dust that was to have made a certain girl happy had been stolen by the murderer of his friend. He listened abstractedly to Dugan’s jests, but mostly he brooded over the death of his friend and his own hopes in the same instant.

Cheechako lay at the edge of the circle of firelight and watched the two men. Mostly he watched Holliday, because Holliday was his master, but often his eyes dwelt puzzledly on Dugan. He knew Dugan, and Dugan knew him. Vaguely, a dim remembrance arose, of Dugan in Carson’s cabin, feeding him a sweet and pleasant-tasting liquid out of a bottle while he laughed uproariously. Yes, Cheechako remembered it distinctly. He wondered if Dugan had any more of that pleasant stuff.

Once he rose and started forward tentatively. Dugan had been smelling quite normally human, but as Cheechako drew near him he again smelled like something that is afraid. It puzzled Cheechako. He sniffed and would have gone nearer but first, of course, he looked at Holliday. And Holliday merely glanced at him and did not notice. Cheechako was used to such ignoring. He wagged his tail a little and went back outside the firelight. His master did not want him near.

But later that night, when the two men lay rolled in their blankets in the smoke of the smudge fire, Cheechako went thoughtfully forward again. He began to nudge Dugan’s kit with his nose. There might be some of that sweet-tasting liquid.

Holliday awoke and sat up with a start. The other man had not gone to sleep.

“What the hell’s your dog doing in my kit?” he demanded hysterically.

“We’ll see,” said Holliday. His voice had a curious edge to it.

Cheechako sniffed about. There was something there that had a familiar odor. He drew in his breath in a long and luxurious smell. Then he began to scratch busily.

“I’ll take a look at that,” said Holliday grimly.

He went to where Cheechako scratched, while Dugan moved cautiously among his blankets. The firelight glinted momentarily on polished metal among the coverings. The metal thing was pointed at Holliday’s back, though it trembled slightly.

Holliday looked up.

“Your bacon,” he said, his tone altered. “Get out!” he ordered Cheechako.

Cheechako went away after wagging his tail placatingly. Presently he curled up and slept fitfully, the odor he had sniffed permeating all his dreams. The odor was that of Carson, and Cheechako dreamed of times in the cabin when Dugan was there. Holliday, too, composed himself to slumber, but Dugan lay awake and shivered. Some of Carson’s possessions were in the kit Cheechako had nosed at, and though he had had his revolver on Holliday, Dugan was by no means sure he could have summoned the nerve to kill him. He had killed Carson in a fashion peculiarly his own which did not require that he discharge the weapon himself. But now he debated in a panicky fear if he had not better shoot Holliday sleeping. It would be dangerous down here, not like the hills at all. But it might be best. If that damned dog kept sniffing around——

The next morning he cursed in a species of hysterical relief when he saw Cheechako trotting soberly away behind his master. Cheechako wagged his tail politely in parting. He did not understand why Dugan had feigned not to remember him. Now they were going to find another man, and Holliday would expect him to sniff that man’s legs and look up and wag his tail. It was a ceremony that was part of the scheme of things. Cheechako simply remembered Dugan as a man who had stayed a long time with Carson in the cabin upriver, and had fed him sweet liquid out of a bottle, and now smelled as if he were afraid.

But Holliday, of course, did not know that. Otherwise he would have been burying Dugan by this time, with a grimly satisfied look upon his face.

Far off in the wilderness where the cedars meditated beside a deserted cabin, a faint rumbling murmur set up again. Of course it might have been the wind in the trees, or a minor landslide in the hills not many miles away, or even a giant spruce tree crashing thunderously to the earth. But it lasted just a bit too long for such a simple explanation. To a fanciful hearer, it might have sounded as if the mill of the forest god were grinding its grist again.

And just as such an idea would demand, many unrelated things began to happen which bore obscurely upon the murder of a man now buried deeply beneath a deeply-carved wooden cross.

Holliday, for instance, received two letters. One was from the girl who loved him. One was from the dead man, stained and draggled with long journeying and much forwarding and months on its travels. The letter from the girl told him pitifully that she loved him and wanted to be near him, and offered to come and share any trial or hardship rather than endure the numbing pain of separation. Holliday, of course, knew better than to take her at her word.

The other letter was very short:

Dear Bob:

I’m sending this down by a Chillicoot buck what stopped to ask for some matches. The claim is proving up kind of a bonanza because I already took out near twenty thousand in dust which makes a damn big poke for you with what you got me to keep for you. You better look out or I’ll steal it. Ha, ha.

I got me a new dog that I call Cheechako. He’s a pretty good dog an’ I got a feller to help me out until you come back an’ he’s taut the pup to drink molasses out of a bottle. You out to see it.

Well, no more until next time. Yrs,

Sam.

And the man who had come down the river trail and left Cheechako chained to starve these many long moons past; he found himself growing short of cash and lacking an easier way to recoup his fortunes, decided to do some placer work himself. When he worked with Sam Carson he had marked down a likely spot, but did not trouble to work it because he could attain to wealth so much more simply. Just a bullet that he need not even fire himself. He took canoe and went paddling up the river, having a winter’s supplies bundled up in the bow.

Then the mill stopped again, and again for lack of grist to grind. Doubtless the forest god to whom it belonged went on about his other affairs.

Cheechako slept within the cabin that winter, stretched out before the fire and soaking the heat into his body with the luxurious enjoyment that only a dog can compass. There was no need for the discipline that before had made his chaining necessary. Holliday’s training had had better results than Carson’s. Cheechako was a well-mannered dog, now, who listened soberly when Holliday talked to him.

And Holliday talked often. Loneliness in the wilds is quite different from loneliness anywhere else. With the snow piled in monster drifts about the cabin, so that there was an actual tunnel a good part of the way from the door to the wood-pile, he was utterly isolated from the world. He had to talk. He told Cheechako confidentially just what the girl Outside meant to him. He would not have said it to any living man, but the dog listened soberly. Sometimes Holliday grew morose. Sometimes he called himself a fool for not bringing her with him—and then gave thanks that he did not. And he had moments of passionate jealousy and doubt, wondering if she were waiting for him and believing in him through all the months when no word from either could reach the other.

He read her last letter into tiny fragments, long after he could recite it word for word. He read strange meanings into it, as that she began to feel her loyalty wavering and in honesty wished to place it beyond recall. And then he read them out again and was bitterly ashamed that such things had entered his mind at all. All this was during the days of storm when he could not even build monster fires and thaw out gravel to be shifted where the first waters of spring would wash out its infinitesimal proportion of gold for him.

But Dugan appeared at the cabin in December.

He came on snowshoes and had conquered his first surprise before he shouted outside the cabin door. Dugan had come over in hopes of finding some stray reading-matter, anything to break the monotony of his own cabin some four miles or more away. The smoke warned him that someone was within and no more than a flicker of his eyelids expressed surprise that Holliday was the occupant.

Holliday greeted him with a feverish cordiality, pressed tobacco upon him, bade him remain and eat, presented Cheechako and they talked interminably. Dugan was jollity itself. He was soon assured that Holliday had no suspicion of him. He had left no clue after the murder and Cheechako—who might have gamboled about him—had been trained by Holliday into the perfection of canine manners. Cheechako remembered, yes, but he did not associate Dugan with the death of his former master. And in any event he was a dog, and there was but one master in the world for him. Injuries done to a past owner would not arouse Cheechako now, though he would fight to the last drop of his blood for Holliday. Dugan had every reason in the world to feel secure.

He was secure. In his gratitude for having someone to talk to, Holliday would have welcomed the devil himself. When Dugan finally left for his own cabin, Holliday was more nearly normal than for months.

And it may be that Dugan’s presence kept Holliday sane that winter. He was surely used to loneliness, but no such loneliness as possessed him now. No man is lonely who can keep his brain busy with the things of the moment and the place he is in, but Holliday could not do that. A picture of the girl who waited for him was always at hand. His presence and his desperate work was due to her. He could not help thinking and dreaming of her, and that thinking and dreaming made the solitude into a corroding horror.

Dugan changed all that. He was someone to talk to. Holliday even told him about the girl. He talked for hours about her, while Cheechako lay at one side of the cabin floor and watched gravely, his ears alert and his eyes somber. Often he watched Dugan, and vague memories crept disturbingly about his mind. Here, in this same cabin——

Dugan knew about the murder, too, how Holliday had come joyously to the cabin—and found his best friend murdered and his happiness destroyed in the one instant. Sam Carson had been the keeper of most of Holliday’s possessions, and they had been stolen by the murderer.

It was probably his own feigned sympathy and secret sardonic amusement that suggested a duplication of his former feat to Dugan. Dugan’s own claim was rich—how rich he could not tell until spring. But Holliday’s claim was little worse. Carson had skimmed the cream, but the rest was worth taking, if it could be done without risk.

And Dugan, who had not nerve enough to shoot a man in cold blood, and was too cowardly to pick a fight, grinned obscurely to himself. He fingered his own pokes, which would be bulging when spring came. He thought of Holliday’s. And then he began to whittle out a little contrivance of wood and leathern thongs, which looked very much like a trap, but was much more deadly. It was a clever little idea of his own. Perfectly safe, and absolutely no risk. Suddenly, he stooped and listened. It seemed as if some noise to which his ears were unconsciously attuned had suddenly ceased.

Maybe the mill had stopped again.

And then spring came. From the trees came cracklings as their coatings of sleet and solidified snow were stripped off and fell melting to the earth below. From the river came minor rumblings as the thawed streams of the mountains poured their waters into it, and its surface ice, grown thinner, cracked across and spun downstream in crumbling icepans toward the sea. The rocks, from hooded things in dazzling cerements, peered out naked and glistening like newborn seals at the world that was stirring for its feverish growth of summer. The spruce buds swelled to bursting. Slowly dwindling patches of snow disclosed incongruously green grass prematurely sprouted. And the wild things seemed to awake. Bull caribou roared their challenges in the indefinite distance. Foxes moved about, keen and joyously savage, no longer hampered by the snow. Now and then the winter’s windrift above some hidden hollow stirred, and a peevish bear emerged from his long sleep, sleepily ferocious.

And Holliday worked like a madman. All day long he shoveled his gravel and dirt into the cradle through which a small stream ran. After the first few days he sang. It might be that he would not have a sum that would satisfy him, but he would squander some of it and see the girl who loved him. He would see her and speak to her again! It was no wonder that he sang.

And Dugan? He worked, too, and his eyes glistened at the size of his clean-ups. He filled one poke, then another, and still another as time went on. But Dugan would never be satisfied with what was his own. He went over to Holliday’s cabin now and then, and listened while Holliday told him excitedly of the miracle that would happen. He was going Outside! In a little while longer. He would see the girl.

He told the whole course of his progress to the man who had murdered his friend, while Cheechako sat between his feet and regarded Dugan speculatively. Cheechako could not understand why Dugan so consistently ignored him. It seemed illogical to the dog, because he remembered that in this same cabin——

And at last Holliday came back from the cradle, singing at the top of his voice.

Cheechako had caught some of his festive spirit and danced clumsily about him. Dugan was sitting on the bench before the cabin and his eyelids flickered when Holliday came into view.

“I’m through!” shouted Holliday, at sight of his visitor. “Dugan, I’m through! I’m going down-river in the morning with a fat poke in my pack to see the most wonderful girl in the world!”

Dugan grinned. He had been at the cabin for some little time, and there was a surprise he had prepared for Holliday inside. It was the same surprise he had prepared for Carson.

“I’m going down tomorrow myself,” he said. “Closed up my shack and quit my workings.”

“We’ll celebrate,” said Holliday exuberantly. “Man! I’m going Outside to the most wonderful——”

Cheechako sniffed the air in the cabin. Dugan did not smell normally human. He smelled as if he were afraid. And yet he was grinning and cracking jokes as if he shared in Holliday’s uproarious happiness.

Cheechako continued to be puzzled and to grow more puzzled. Two or three times he cocked up his ears as if listening to a faint rumbling murmur far off in the wilds which might have been anything—even the mill of a forest god, grinding the grist of men’s destinies. But mostly he watched the two men.

Dugan produced a bottle, long hoarded, but Holliday would not touch it. He wanted to stay awake, he said, that no atom of his wonderful good luck should go untasted to the full. He would be starting downstream at daybreak. And Dugan grinned, and drank himself.

Holliday began to cook a festive meal. The smells were savory and delicious, but Cheechako’s nose suddenly attracted him to an unusual spot. He went tentatively toward Holliday’s bunk. Being a well-mannered dog, he knew he should never climb upon his master’s bed, but something drew him there irresistibly. He sniffed, and Dugan’s smell was suddenly that of a thing in deadly fear. Cheechako turned his head and regarded him puzzledly. Dugan’s scent was on his master’s blankets, too, and Dugan had no business to be there. Cheechako sniffed, bewildered. This other odor——

“There’s just one thing,” said Holliday with a sudden wistful gravity. “Old Sam’s dead. I told you how he was murdered. I wish—well, I wish he was going Outside with me.”

The faint rumbling outside that sounded like millstones grinding grew suddenly loud and harsh, as if the stones were crumbling up the last stray grains that had been fed to them. Cheechako cocked his ears, but that was only a noise. There was a queer smell on his master’s bunk. He heaved up his forepaws to sniff it more nearly.

“Cheechako!” snapped Dugan. Dugan had gone suddenly pale, and more than ever he had the smell of fear about him.

Holliday lifted his head and a curious expression came upon his face. Dugan went over and took Cheechako by the collar.

“Shedding fleas on your bunk,” he said to Holliday, grinning. “But he ought to share in the celebration, too. Got any molasses?”

He knew, of course. He reached up and took down the bottle of syrup Holliday had saved as a supreme luxury.

“Taught a dog to do this once,” grinned Dugan. “Here, you, Cheechako! Open your mouth!”

Cheechako sniffed at his leg. Then he saw the bottle. His eyes danced. Dugan had remembered at last! He jumped up to lick eagerly.

“Ho!” roared Dugan, as Cheechako struggled frantically to coax out the sticky sweet stuff faster than it would flow. “I knew you’d like it! Watch him, Holliday!”

Holliday straightened up.

“You’ve never heard me call that dog ‘Cheechako,’” he said queerly. “I’ve always called him ‘Pup.’ The only other man who’d know his name would be Sam Carson and—” Holliday’s voice changed swiftly—“and the man who killed him! And that trick— By God, you’re Sam Carson’s murderer!”

His revolver flashed out. Dugan gasped. The bottle fell to the floor and Cheechako lapped eagerly at its exuding contents.

“You shot him from behind,” said Holliday savagely. “With your gun not a foot from his head! Get out that gun now, Dugan. I give you just two seconds!”

Dugan’s teeth chattered. His eyes darted despairingly to the bunk. Holliday’s face was like stone. There was no faintest trace of mercy in it. With a sudden squeal like that of a cornered rat, Dugan rushed for him.

And Holliday’s revolver was out and in his hand, but Dugan’s open-handed attack brought an instinctive response in kind. His free fist shot out in a terrific blow. It caught Dugan squarely between the eyes and hurled him backward. He staggered, and his foot crushed Cheechako’s paw. The dog leaped up with a yelp and bared teeth and his movement was enough to upset Dugan’s balance completely. He toppled backward and a sudden terrible scream filled all the cabin.

He fell against the bunk and his arms clutched wildly, while his face showed only frozen horror. Then he crashed down on the blankets.

And there was a bellowing roar and a burst of smoke from the bunk. Dugan did not even shudder. He lay quite still. Presently a sullen little “drip-drip-drip” sounded on the floor.

Holliday bent over and pawed among the blankets. He brought out a curious little contrivance, very much like a trap. It was a board with a revolver tied to it and a thong so arranged that pressure on the thong would discharge the revolver into the source of the pressure.

Cheechako sniffed at it. It was the source of the peculiar odor he had noted in his master’s bunk. He wagged his tail placatingly and looked up at Holliday.

“Right where my head would have gone,” said Holliday, shuddering a little in spite of himself, “when I lay down to sleep. And he was going to stay here overnight. I see how he killed Carson now. Pfaugh!”

Sick with disgust, and a little shaken, he flung down the board.

Holliday did not go down-river at daybreak. It was nearer noon when he started. And instead of one deeply-carved cross in the ground about the cabin there were two. One read:

And the other:

Holliday paddled down the river with Cheechako in the bow of his canoe, looking with bright and curious eyes at all that was to be seen. Holliday had the gold that he had washed out himself during the winter. He had, besides, gold taken from Dugan’s pokes to the amount that Dugan had stolen. The surplus he had scattered in the river. He did not want it. He was going Outside to the girl who had waited for him.

And the mill? Oh, the mill had ground up all its grist. It stopped, until one day a half-breed killed a white man in some dispute over an Indian woman, and the echo of the shot traveled thinly over the wilds. And then a faint rumbling murmur set up which might, of course, have been the wind in the trees, or a landslide in the hills not so very far away. But, equally, of course, it might not.