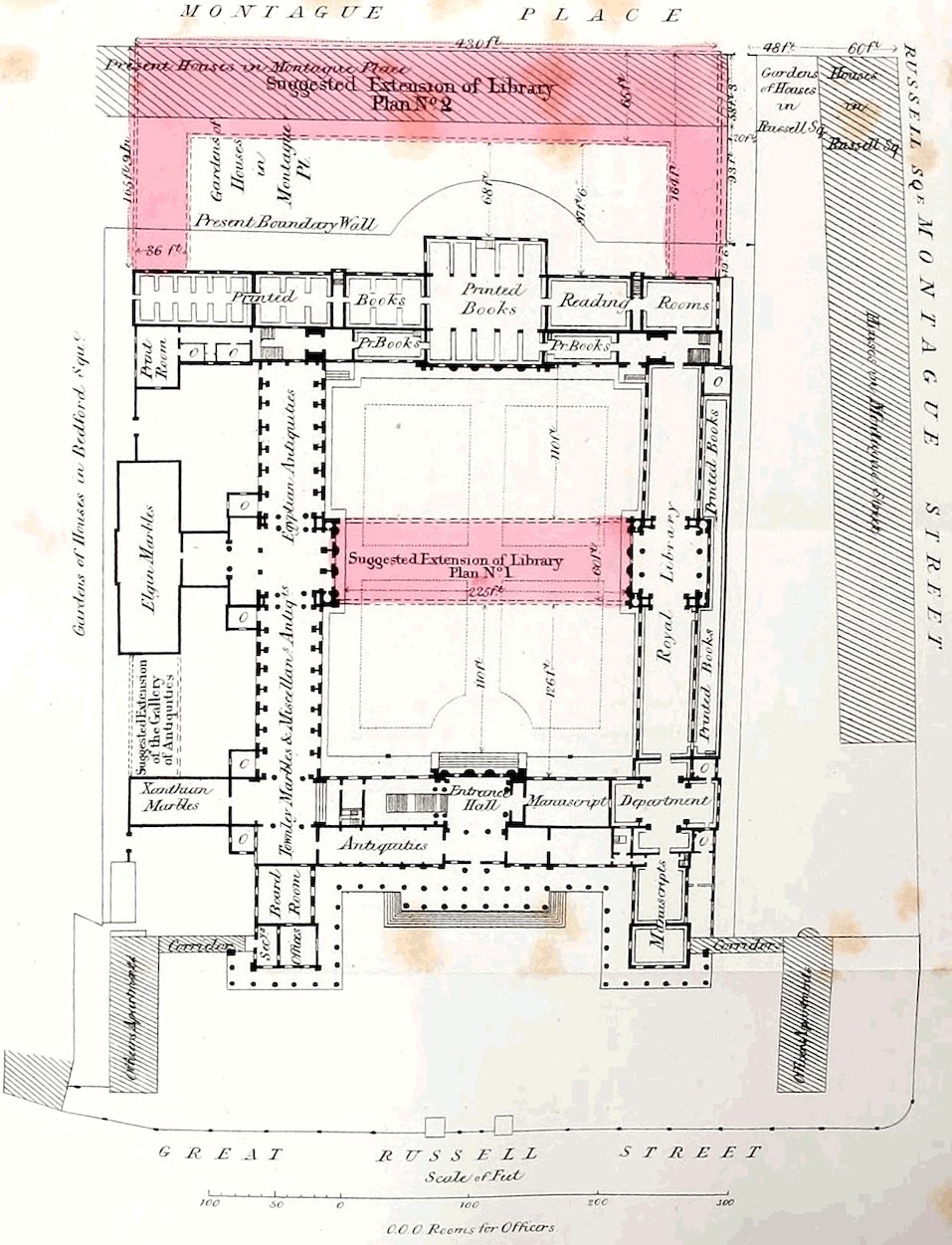

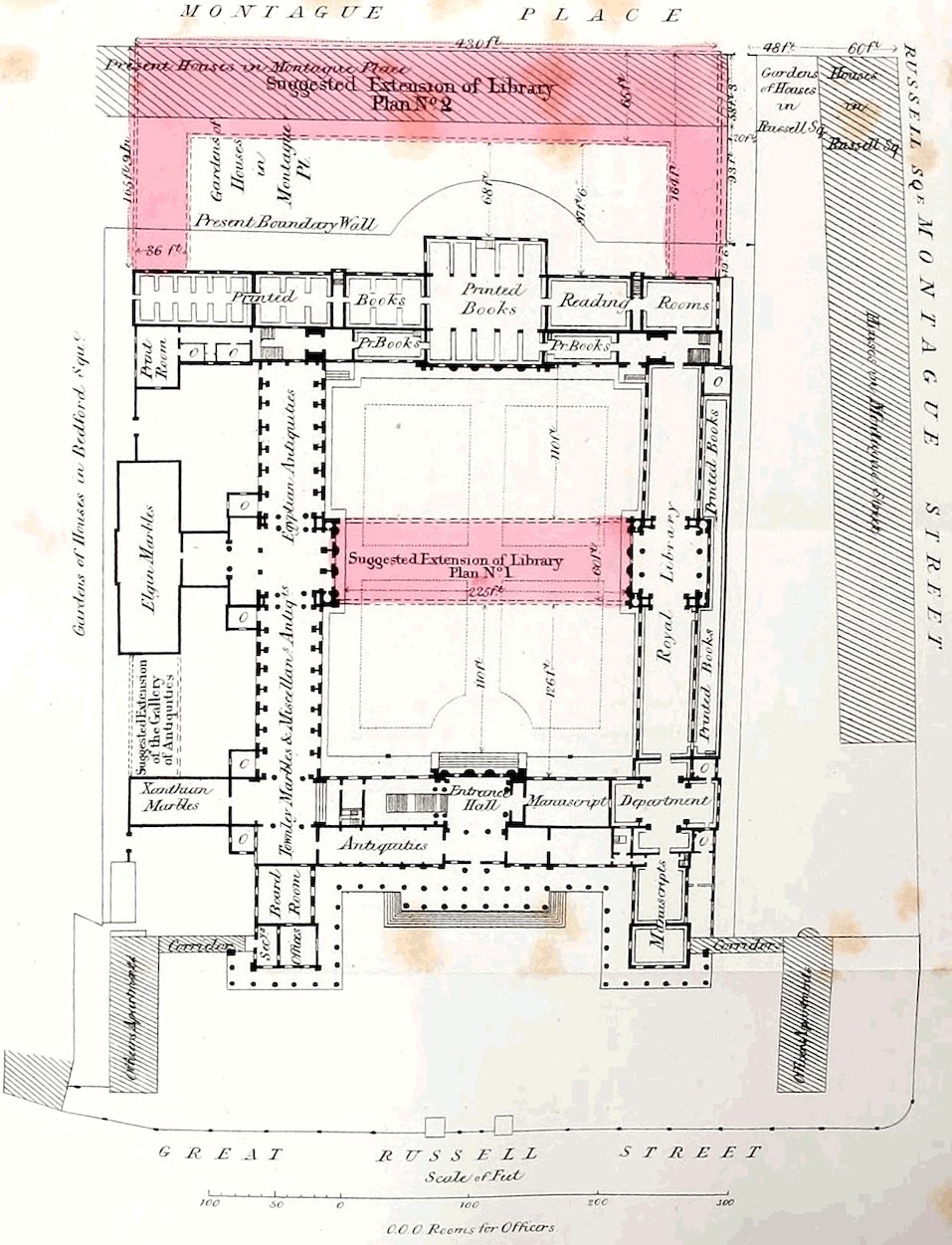

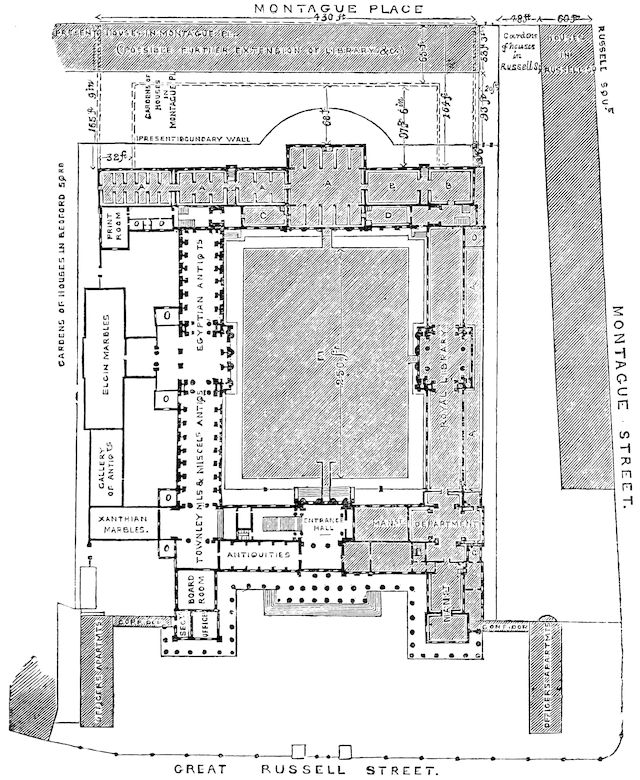

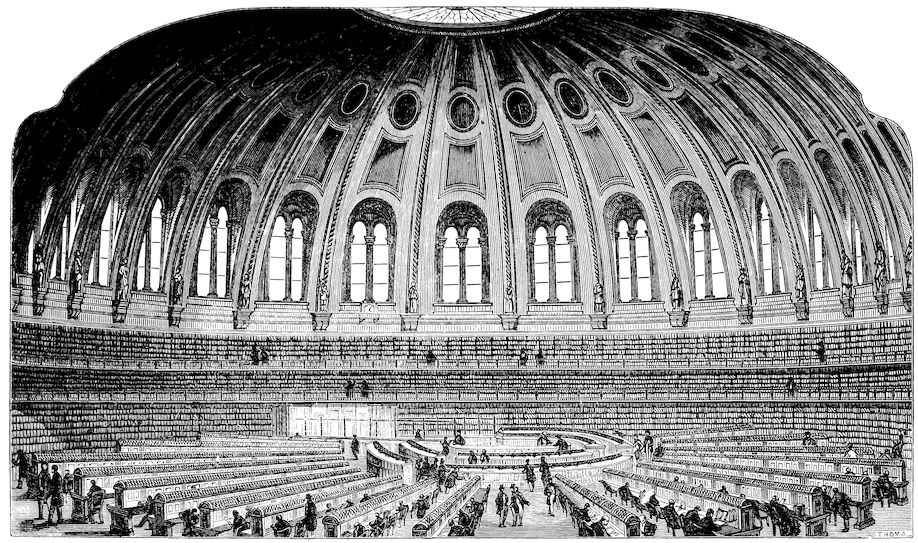

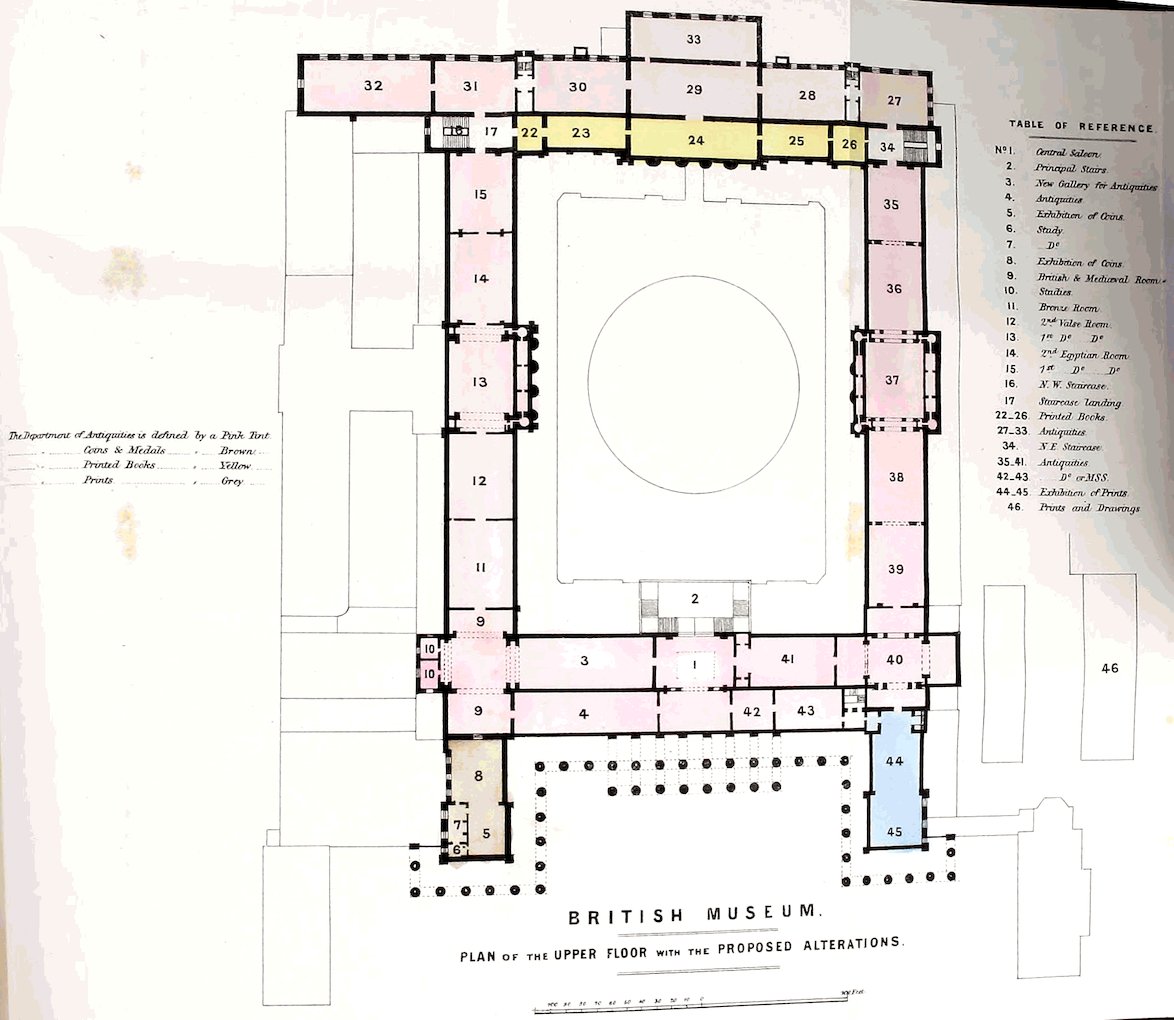

Plate Nº 2

SUGGESTIONS, MADE IN 1847.

FOR THE ENLARGEMENT OF THE LIBRARY OF THE

BRITISH MUSEUM.

BEING THE FAC-SIMILE OF A PLAN INSERTED IN A PAMPHLET (WRITTEN IN 1846.)

ENTITLED

PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN LONDON AND PARIS.

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

‘If we were to take away from the Museum Collection [of Books] the King’s Library, and the collection which George the Third gave before that, and then the magnificent collection of Mr. Cracherode, as well as those of Sir William Musgrave, Sir Joseph Banks, Sir Richard Colt Hoare, and many others,—and also all the books received under the Copyright Act,—if we were to take away all the books so given, I am satisfied not one half of the books [in 1836], nor one third of the value of the Library, has been procured with money voted by the Nation. The Nation has done almost nothing for the Library....

‘Considering the British Museum to be a National Library for research, its utility increases in proportion with the very rare and costly books, in preference to modern books.... I think that scholars have a right to look, for these expensive works, to the Government of the Country....

‘I want a poor student to have the same means of indulging his learned curiosity,—of following his rational pursuits,—of consulting the same authorities,—of fathoming the most intricate inquiry,—as the richest man in the kingdom, as far as books go. And I contend that Government is bound to give him the most liberal and unlimited assistance in this respect. I want the Library of the British Museum to have books of both descriptions....

‘When you have given a hundred thousand pounds,—in ten or twelve years,—you will begin to have a library worthy of the British Nation.’—

Notices of some early Donors of Books.—The Life and Collections of Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode.—William Petty, first Marquess of Lansdowne, and his Library of Manuscripts.—The Literary Life and Collections of Dr. Charles Burney.—Francis Hargrave and his Manuscripts.—The Life and Testamentary Foundations of Francis Henry Egerton, Ninth Earl of Bridgewater.

The Reader has now seen that, within some twelve or fifteen years, a Collection of Antiquities, comparatively small and insignificant, was so enriched as to gain the aspect of a National Museum of which all English-speaking men might 414be proud, and mere fragments of which enlightened Foreign Sovereigns were under sore temptation to covet. He has seen, also, that the praise of so striking a change was due, in the main, to the public spirit and the liberal endeavours of a small group of antiquarians and scholars. They were, most of them, men of high birth, and of generous education. They were, in fact, precisely such men as, in the jargon of our present day, it is too much the mode to speak of as the antitheses of ‘the People,’ although in earlier days men of that strain were thought to be part of the very core and kernel of a nation.

But if it be undeniably true that the chief and primary merit of so good a piece of public service was due to the Hamiltons, Towneleys, Elgins, and Knights of the last generation, it is also true that the Public, through their representatives, did, at length, join fairly in the work by bearing their part of the cost, though they could share neither the enterprise, the self-denial, nor the wearing toils, which the work had exacted.

Now that the story turns to another department of the National Museum, we find that the same primary and salient characteristic—private liberality of individuals, as distinguished from public support by the Kingdom—still holds good. But we have to wait a very long time indeed, before we perceive public effort at length falling into rank with private, in the shape of parliamentary grants for the purchase of books, calculated even upon a rough approximation towards equality.

As Cotton, Sloane, Harley, and Arthur Edwards, were the first founders of the Library, so Birch, Musgrave, Tyrwhitt, Cracherode, Banks, and Hoare, were its chief augmentors, until almost ninety years had elapsed since the Act of Organization. Of the Collections of those 415ten benefactors, eight came by absolute gift. For the other two, much less than one half of their value was returned to the representatives of the founders. And that, it has been shown, was provided, not by a parliamentary grant, but out of the profits of a lottery.

The first important addition to the Library, subsequent to those gifts which have been mentioned in a preceding chapter as nearly contemporaneous with the creation of the Museum, was made by the Will of Dr. Thomas Birch, |Bequest of Dr. Thomas Birch, January, 1766.| one of the original Trustees. It comprised a valuable series of manuscripts, rich in collections on the history, and especially the biographical history, of the realm, and a considerable number of printed books of a like character.

Dr. Birch was born in 1705, and died on the ninth of January, 1766. He was one of the many friends of Sir Hans Sloane, in the later years of Sir Hans’ life. When the Museum was in course of organization, Birch acted not only as a zealous Trustee, but he occasionally supplied the place of Dr. Morton as Secretary. His literary productions have real and enduring value, though their value would probably have been greater had their number been less. His activity is sufficiently evidenced by the works which he printed, but can only be measured when the large manuscript collections which he bequeathed are taken into the account. Very few scholars will now be inclined to echo Horace Walpole’s inquiry—made when he saw the Catalogue of the Birch MSS.—‘Who cares for the correspondence of Dr. Birch?’

Soon after the receipt of the Birch Collection, a choice assemblage of English plays was bequeathed to the Museum by David Garrick. Its formation had been one of the favourite relaxations of the great actor. And the study of 416the plays gathered by Garrick had a large share in moulding the tastes and the literary career of Charles Lamb. Thence he drew the materials of the volume of Specimens which has made the rich stores of the early drama known to thousands of readers who but for it, and for the Collection which enabled him to compile it, could have formed no fair or adequate idea of an important epoch in our literature.

Sir William Musgrave was another early Trustee whose gifts to the Public illustrated the wisdom of Sloane’s plan for the government of his Museum and of its parliamentary adoption. Musgrave shared the predilection of Dr. Birch for the study of British biography and archæology, and he had larger means for amassing its materials. He was descended from a branch of the Musgraves of Edenhall, and was the second son of Sir Richard Musgrave of Hayton Castle, to whom he eventually succeeded. He made large and very curious manuscript collections for the history of portrait-painting in England (now Additional MSS. 6391–6393), and also on many points of the administrative and political history of the country. He was a zealous Trustee of the British Museum, and in his lifetime made several additions to its stores. On his death, in 1799, all his manuscripts were bequeathed to the Museum, together with a Library of printed British Biography—more complete than anything of its kind theretofore collected.

This last-named Collection extended (if we include a partial and previous gift made in 1790) to nearly two thousand volumes, and it probably embraced much more than twice that number of separate works. For it was rich in those biographical ephemera which are so precious to the historical inquirer, and often so difficult of obtainment, when needed. Nearly at the same period (1786) a 417valuable Collection of classical authors, in about nine hundred volumes, was bequeathed by another worthy Trustee, Mr. Thomas Tyrwhitt, distinguished both as a scholar and as the Editor of Chaucer.

But all the early gifts to the Museum, made after its parliamentary organization, were eclipsed, at the close of the century, by the bequest of the Cracherode Collections. |The Bequest of the Cracherode Collection.| That bequest comprised a very choice library of printed books; a cabinet of coins, medals, and gems; and a series of original drawings by the great masters, chosen, like the books and the coins, with exquisite taste, and, as the auctioneers say, quite regardless of expense. |1799.| It also included a small but precious cabinet of minerals.

The collector of these rarities was wont to speak of them with great modesty. They are, he would say, mere ‘specimen collections.’ But to amass them had been the chief pursuit of a quiet and blameless life.

Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode was born in London about the year 1730. And he was ‘a Londoner’ in a sense and degree to which, in this railway generation, it would be hard to find a parallel. Among the rich possessions which he inherited from Colonel Cracherode, his father—whose fortune had been gathered, or increased, during an active career in remote parts of the world—was an estate in Hertfordshire, on which there grew a certain famous chestnut-tree, the cynosure of all the country-side for its size and antiquity. This tree was never seen by its new owner, save as he saw the poplars of Lombardy, or the cedars of Lebanon—in an etching. In the course of a long life he never reached a greater distance from the metropolis than Oxford. He never mounted a horse. The ordinary extent of his travels, during the prime years of a long life, was from Queen Square, in Westminster, to Clapham. For 418almost forty years it was his daily practice to walk from his house to the shop of Elmsly, a bookseller in the Strand, and thence to the still more noted shop of Tom Payne, by ‘the Mews-Gate.’ Once a week, he varied the daily walk by calling on Mudge, a chronometer-maker, to get his watch regulated. His excursions had, indeed, one other and not infrequent variety—dictated by the calls of Christian benevolence—but of these he took care to have no note taken.

Early in life, and probably to meet his father’s wish, he received holy orders, but he never accepted any preferment in the Church. He took the restraints of the clerical profession, without any of its emoluments. His classical attainments were considerable, but the sole publication of a long life of leisure was a university prize poem, printed in the Carmina Quadragesimalia of 1748. The only early tribulation of a life of idyllic peacefulness was a dread that he might possibly be called upon, at a coronation, to appear in public as the King’s cupbearer—his manor of Great Wymondley being held by a tenure of grand-serjeantry in that onerous employment. Its one later tinge of bitterness lay in the dread of a French invasion. These may seem small sorrows, to men who have had a full share in the stress and anguish of the battle of life. But the weight of a burden is no measure of the pain it may inflict. Mr. Cracherode looked to his possible cupbearership, with apprehension just as acute as that with which Cowper contemplated the awful task of reading in public the Journals of the House of Lords. And the sleepless nights which long afterwards were brought to Cracherode by the horrors of the French revolutionary war were caused less by personal fears than by the dread of public calamities, more terrible than death. During one 419year of the devastations on the other side of the Channel, chronicled by our daily papers, Mr. Cracherode was thought by his friends to have ‘aged’ full ten years in his aspect.

The one active and incessant pursuit of this noiseless career was the gathering together of the most choice books, the finest coins and gems, the most exquisite drawings and prints, which money could buy, without the toils of travel. Our Collector’s liberality of purse enabled him to profit, at his ease, by the truth expressed in one of the wise maxims of John Selden:—‘The giving a dealer his price hath this advantage;—he that will do so shall have the refusal of whatsoever comes to the dealer’s hand, and so by that means get many things which otherwise he never should have seen.’ The enjoyment—almost a century ago—of six hundred pounds a year in land, and of nearly one hundred thousand pounds invested in the ‘sweet simplicity’ of the three per cents., enabled Mr. Cracherode to outbid a good many competitors. His natural wish that what he had so eagerly gathered should not be scattered to the four winds on the instant he was carried to his grave, and also the public spirit which dictated the choice of a national repository as the permanent abode of his Collections, has already made that long course of daily visits to the London dealers in books, coins, and drawings, fruitful of good to hundreds of poorer students and toilers, during more than two generations. From stores such as Mr. Cracherode’s—when so preserved—many a useful labourer gets part of his best equipment for the tasks of his life. He, too, would enjoy a visit to the ‘Paynes’ and the ‘Elmslys’ of the day as keenly as any book-lover that ever lived, but is too often, perhaps, obliged to content himself with an outside glance at the windows. Public libraries put him practically 420on a level with the wealthiest connoisseur. When, as in this case—and in a hundred more—such libraries derive much of their best possessions from private liberality, a life like Mordaunt Cracherode’s has its ample vindication, and the sting is taken out of all such sarcasms as that which was levelled—in the shape of the query, ‘In all that big library is there a single book written by the Collector himself?’—by some snarling epistolary critic, when commenting on a notice that appeared in The Times on the occasion of Mr. Cracherode’s death.

On another point our Collector was exposed to the shafts of sarcastic comment. He loved a good book to be printed on the very choicest material, and clothed in the richest fashion. The treasure within would not incline him to tolerate blemishes without.—

In Cracherode’s eyes, external charms such as these were scarcely less essential than the intrinsic worth of the author. ‘Large paper’ and broad pure margins are fancies which it needs not much culture or much wit to banter. But now and then, they are ridiculed by those who have just as little capacity to judge the pith and 421substance of books, as of taste to appreciate beauty in their outward form.[1]

The solidity of those three per cents., and the plodding perseverance of their owner, were in time rewarded by the collection (1) of a library containing only four thousand five hundred volumes, but of which probably every volume—on an average of the whole—was worth, in mercantile eyes, some three pounds; (2) of seven portfolios of drawings, still more choice; (3) of a hundred portfolios of prints, many of which were almost priceless; and (4) of coins and gems—such as the cameo of a lion on sardonyx, and the intaglio of the Discobolos—worthy of an imperial cabinet.

The ruling passion kept its strength to the last. An agent was buying prints, for addition to the store, when the Collector was dying. About four days before his death, Mr. Cracherode mustered strength to pay a farewell visit to the old shop at the Mews-Gate. He put a finely printed Terence (from the press of Foulis) into one pocket, and a large paper Cebes into another; and then,—with a longing look at a certain choice Homer, in the course of which he mentally, and somewhat doubtingly, balanced its charms with those of its twin brother in Queen Square,—parted finally from the daily haunt of forty peripatetic and studious years.

Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode died towards the close of 1799. He bequeathed the whole of his collections to the Nation, with the exception of two volumes of books. A polyglot Bible was given to Shute Barrington, Bishop 422of Durham; a princeps Homer to Cyril Jackson, Dean of Christ Church. Those justly venerated men were his two dearest friends.

The next conspicuous donor to the Library of the British Museum was a contemporary of the learned recluse of Queen Square, but one whose life was passed in the thick of that worldly turmoil and conflict of which Mr. Cracherode had so mortal a dread. |The Collector of the Lansdowne Manuscripts.| To the Collector of the ‘Lansdowne Manuscripts,’ political excitement was the congenial air in which it was indeed life to live. But he, also, was a man beloved by all who had the privilege of his intimate friendship.

William Petty-Fitzmaurice, third Earl of Shelburne, and first Marquess of Lansdowne, was born in Dublin, in May, 1737. He was the son of John, Earl of Shelburne in the peerage of Ireland, and afterwards Baron Wycombe in the peerage of Great Britain. The Marquess’s father united the possessions of the family founded by Sir William Petty with those which the Irish wars had left to the ancient line of Fitzmaurice.

William, Earl of Shelburne, was educated by private tutors, and then sent to Christ Church, Oxford. He left the University early, to take (in or about the year 1756) a commission in the Guards. He was present in the battles of Campen and of Minden. At Minden, in particular, he evinced distinguished bravery. In May, 1760, and again in April, 1761, he was elected by the burgesses of High Wycombe to represent them in the House of Commons. But the death of Earl John, in the middle of 1761, called his son to take his seat in the House of Lords. He soon evinced the possession of powers eminently fitted to shine in Parliament. The impetuosity he had shown on the field 423of Minden did not desert him in the strife of politics. Those who had listened to the early speeches of Pitt might well think that the army had again sent them a ‘terrible cornet of horse.’ So good a judge of political oratory as was Lord Camden thought Shelburne to be second only to Chatham himself.

Lord Shelburne’s first speech in Parliament—the first, at least, that attracted general notice—was made in support of the Court and the Ministry (November 3, 1762). Within less than six months after its delivery he was called to the Privy Council, and placed at the head of the Board of Trade and Plantations. This appointment was made on the 23rd of April, 1763. Just before it he had taken part in that delicate negotiation between Lord Bute and Henry Fox (afterwards Lord Holland) which has been kept well in memory by a jest of the man who thought himself the loser in it. This early incident is in some sort a key to many later incidents in Lord Shelburne’s life.

For, in all the acts and offices of a political career, save only one, Lord Shelburne was characteristically a lover of soft words. In debate, he could speak scathingly. In conversation, he was always under temptation to flatter his interlocutor. In this conversation of 1763 with Fox, Shelburne’s innate love of smoothing asperities co-operated with his belief that it was really for the common interest that Bute and Fox should come to an agreement, to make him put the premier’s offer into the most pleasing light. When Fox found he was to get less than he thought to have, he fiercely assailed the negotiator. Lord Shelburne’s friends dwelt on his love of peace and good fellowship. At worst, said they, it was but a ‘pious fraud.’ ‘I can see the fraud plainly enough,’ rejoined Fox, ‘but where is the piety?’

424The office accepted in April was resigned in September, when the coalition with ‘the Bedford party’ was made. Lord Shelburne’s loss was felt in the House of Lords. But it was in the Commons that the Ministry were now feeblest. ‘I don’t see how they can meet Parliament,’ said Chesterfield. ‘In the Commons they have not a man with ability and words enough to call a coach.’

In February, 1765, Shelburne married Lady Sophia Carteret, one of the daughters of the Earl of Granville. The marriage was a very happy one. Not long after it, he began to form his library. |Formation of Lord Shelburne’s Library.| Political manuscripts, state papers of every kind, and all such documents as tend to throw light on the arcana of history, were, more especially, the objects which he sought. And the quest, as will be seen presently, was very successful. For during his early researches he had but few competitors.

On the organization of the Duke of Grafton’s Ministry in 1766 (July 30) Lord Shelburne was made Secretary of State for the Southern Department, to which at that time the Colonial business was attached. |1766–1768.| His colleague, in the Northern, was Conway, who now led the House of Commons. As Secretary, Lord Shelburne’s most conspicuous and influential act was his approval of that rejection of certain members of the Council of Massachusetts by Governor Bernard, which had so important a bearing on colonial events to come.

Shelburne, however, was one of a class of statesmen of whom, very happily, this country has had many. He was able to render more efficient service in opposition than in office. Of the Board of Trade he had had the headship but a few months. As Secretary of State, under the Grafton Administration, he served little more than two years. His opponents were wont to call him an ‘impracticable’ man. 425But if he shared some of Chatham’s weaknesses, he also shared much of his greatness. And on the capital question of the American dispute, they were at one. They both thought that the Colonies had been atrociously misgoverned. They were willing to make large concessions to regain the loyalty of the Colonists. They were utterly averse to admit of a severance.

Under circumstances familiar to all readers, and by the personal urgency of the King, Lord Shelburne was dismissed from his first Secretaryship in October, 1768. His dismissal led to Chatham’s resignation. Shelburne became a prominent and powerful leader of the Opposition, an object of special dislike to a large force of political adversaries, and of warm attachment to a small number of political friends. His personal friends were, at all times, many.

The nickname under which his opponents were wont to satirize him has been kept in memory by one of the many infelicities of speech which did such cruel injustice to the fine parts and the generous heart of Goldsmith. The story has been many times told, but will bear to be told once again. The author of the Vicar of Wakefield was an occasional supporter of the Opposition in the newspapers. One day, in the autumn of 1773, he wrote an article in praise of Lord Shelburne’s ardent friend in the City, the Lord Mayor Townshend. Sitting, in company with Topham Beauclerc, at Drury Lane Theatre, just after the appearance of the article, Goldsmith found himself close beside Lord Shelburne. His companion told the statesman that his City friend’s eulogy came from Goldsmith’s pen. |1773. November.| ‘I hope,’ said his Lordship—addressing the poet—‘you put nothing in it about Malagrida?’ |Hardy, Life of Lord Charlemont, vol. i, p. 177.| ‘Do you know,’ rejoined poor Goldsmith, ‘I could never conceive the reason why they call you “Malagrida,”—for Malagrida was a very good 426sort of man.’ This small misplacement of an emphasis was of course quoted in the clubs against the unlucky speaker. ‘Ah!’ said Horace Walpole, with his wonted charity, ‘that’s a picture of the man’s whole life.’

Lord Shelburne’s library profited by his long releasement from the cares of office. He bestowed much of his leisure upon its enrichment, and especially upon the acquisition of manuscript political literature. In 1770, he was fortunate enough to obtain a considerable portion of the large and curious Collection of State Papers which Sir Julius Cæsar had begun to amass almost two centuries before. Two years later, he acquired no inconsiderable portion of that far more important series which had been gathered by Burghley.

Whilst Lord Shelburne was serving with the army in Germany, the ‘Cæsar Papers’ had been dispersed by auction. There were then—1757—a hundred and eighty-seven of them. About sixty volumes were purchased by Philip Cartaret Webb, a lawyer and juridical writer, as well as antiquary, of some distinction. On Mr. Webb’s death, in 1770, these were purchased by Shelburne from his executors. On examining his acquisition, the new possessor found that about twenty volumes related to various matters of British history and antiquities; thirty-one volumes to the business of the British Admiralty and its Courts; ten volumes to that of the Treasury, Star Chamber, and other public departments; two volumes contained treaties; and one volume, papers on the affairs of Ireland.

The ‘Burghley papers,’ acquired in 1772, had passed from Sir Michael Hickes, one of that statesman’s secretaries, to a descendant, Sir William Hickes, by whom they were sold to Chiswell, a bookseller, and by him to 427Strype, the historian. These (as has been mentioned in a former chapter) were looked upon with somewhat covetous eyes by Humphrey Wanley, who hoped to have seen them become part of the treasures of the Harleian Library. On Strype’s death they passed into the hands of James West, and from his executors into the Library at Shelburne House. They comprised a hundred and twenty-one volumes of the collections and correspondence of Lord Burghley, together with his private note-book and journal.

Another valuable acquisition, made after Lord Shelburne’s retirement in 1768 from political office, consisted of the vast historical Collections of Bishop White Kennett, extending to a hundred and seven volumes, of which a large proportion are in the Bishop’s own untiring hand. Twenty-two of these volumes contain important materials for English Church History. Eleven volumes contain biographical collections, ranging between the years 1500 and 1717. All that have been enumerated are now national property.

Other choice manuscript collections were added from time to time. Among them may be cited the papers of Sir Paul Rycaut—which include information both on Irish and on Continental affairs towards the close of the seventeenth century; the correspondence of Dr. John Pell, and that of the Jacobite Earl of Melfort.

These varied accessions—with many others of minor importance—raised the Shelburne Library into the first rank among private repositories of historical lore. To amass and to study them was to prove to its owner the solace of deep personal affliction, as well as the relief of public toils. At the close of 1770, he lost a beloved wife, 428after a union of less than six years. He remained a widower until 1779.

Another source of solace was found in labours that have an inexhaustible charm, for those who are so happy as to have means as well as taste for them. |Lord Shelburne as a Landscape Gardener.| Lord Shelburne lived much at Loakes—now called Wycombe Abbey—a delightful seat, just above the little town of High Wycombe. Its striking framework of beech-woods, its fine plane-trees and ash-trees, and its broad piece of water, make up a lovely picture, much of the attraction of which is due to the skill and judgment with which its then owner elicited and heightened the natural beauties of the place.[2] But those of Bowood exceeded them in Lord Shelburne’s eyes. There, too, he did very much to enhance what nature had already done, and he had the able assistance of Mr. Hamilton of Pains-Hill. In consequence of their joint labours, almost every species of oak may be seen at Bowood, with great variety of exotic trees of all sorts. Both wood and water combine to make, from some points of view, a resemblance between Wycombe and Bowood. And both differ from many much bepraised country seats in the wise preference of natural beauty—selected and heightened—to artificial beauty. Lord Shelburne himself was wont to say: ‘Mere workmanship should never be introduced where the beauty and variety of the scenery are, in themselves, sufficient to excite admiration.’

But, in their true place, few men better loved the productions of artistic genius. He collected pictures and sculpture, as well as trees and books. He was the first of 429his name who made Lansdowne House in London, as well as Loakes and Bowood in the country, centres of the best society in the intellectual as well as in the fashionable world.

Years passed on. The course of public events—and especially the death of Lord Chatham and the issues of the American war—together with many conspicuous proofs of his powers in debate, tended more and more to bring Lord Shelburne to the front. Between him and Lord Rockingham, as far as regards real personal ability—whether parliamentary or administrative—there could, in truth, be little ground for comparison. But in party connection and following, the claims of the inferior man were incontestible. Lord Shelburne, towards the close of 1779, signified his readiness to waive his pretensions to take the lead—in the event of the overthrow of the existing Government—and his willingness to serve under Lord Rockingham; so little truth was there in the assertion, |H. Walpole to Mann; 1780. March 21.| made by Horace Walpole to his correspondent at Florence, that Shelburne ‘will stick at nothing to gratify his ambition.’

But that very charge is, in fact, a tribute. Walpole’s indignation had been excited just at that moment by the zealous assistance which Shelburne had given, in the House of Lords, to the efforts of Burke in the lower House in favour of economical reforms. He had brought forward a motion on that subject on the same night on which Burke had given notice for the introduction of his famous Bill (December, 1779). He continued his efforts, and presently had to encounter a more active and pertinacious opponent of retrenchment than Horace Walpole.

In the course of a vigorous speech on reform in the 430administration of the army, Lord Shelburne had censured a transaction in which Mr. Fullerton, a Member of the House of Commons, was intimately concerned. |Lord Shelburne’s Duel with Fullerton.| Fullerton made a violent attack, in his place in the House, upon his censor. But his speech was so disorderly that he was forced to break off. In his anger he sent Lord Shelburne a minute, not only of what he had actually spoken, but of what he had intended to say, in addition, had the rules of Parliament permitted. And he had the effrontery to wind up his obliging communication with these words:—‘You correspond, as I have heard abroad, with the enemies of your country.’ His letter was presented to Lord Shelburne by a messenger.

The receiver, when he had read it, said to the bearer: ‘The best answer I can give Mr. Fullerton is to desire him to meet me in Hyde Park, at five, to-morrow morning.’ They fought, and Shelburne was wounded. On being asked how he felt himself, he looked at the wound, and said: ‘I do not think that Lady Shelburne will be the worse for this.’ But it was severe enough to interrupt, for a while, his political labours.

On the formation in March, 1782, of the Rockingham Administration, he accepted the Secretaryship of State, and took with him four of his adherents into the Cabinet. But the most curious feature in the transaction was that Lord Shelburne carried on, personally, all the intercourse in the royal closet that necessarily preceded the formation of the Ministry, although he was not to be its head. George the Third would not admit Lord Rockingham to an audience until his Cabinet was completely formed. The man whose exclusion from the Grafton Ministry the King had so warmly urged a few years before, was now not less warmly urged by him to throw over his party, and to 431head a cabinet of his own. He resisted all blandishment, and virtually told the King that the triumph of the Opposition must be its triumph as an unbroken whole; though he doubtless felt, within himself, that the cohesion was of singularly frail tenacity.

On the 24th of March, Shelburne had the satisfaction of conveying to Lord Rockingham the royal concession of his constitutional demands—obtained after a wearisome negotiation, and only by the piling up of argument on argument in successive conversations at the ‘Queen’s House,’ lasting sometimes for three mortal hours. |Death of Lord Rockingham, 1782, 1 July.| Three months afterwards, the new Premier was dead. And with him departed the cohesion of the Whigs.

As Secretary of State, Lord Shelburne’s chief task had been the control of that double and most unwelcome negotiation which was carried on at Paris with France and with America.[3] For it had fallen to the lot of the utterer of the ‘sunset-speech,’[4]—‘if we let America go, the sun of Great Britain is set’—to arrange the terms of American pacification. And the obstructions in that path which were created at home were even more serious stumbling-blocks than were the difficulties abroad. The cardinal points of Lord Shelburne’s policy, at this time, were to retain, by hook or crook, some amount or other of hold upon America, and at the worst to keep the Court of France from enjoying the prestige, or setting up the pretence, of having dictated the terms of peace.

That the split in the Whig party was really and altogether 432inevitable, now that Rockingham’s death had placed Shelburne above reasonable competition for the premiership, was made known to him when at Court, in the most abrupt manner. On the 7th of July (six days after the death of the Marquess), Fox took him by the sleeve, with the blunt question: ‘Are you to be First Lord of the Treasury?’ |Walpole to Mann (from an eye witness), 1782, July 7.| When Shelburne said ‘Yes,’ the instant rejoinder was, ‘Then, my Lord, I shall resign.’ Fox had brought the seals in his pocket, and proceeded immediately to return them to the King.

In his first speech as Premier, Lord Shelburne spoke thus:—‘It has been said that I have changed my opinion about the independence of America.... My opinion is still the same. When that independence shall have been established, the sun of England may be said to have set. I have used every effort, public and private—in England, and out of it—to avert so dreadful a disaster.... |Parliamentary Debates, vol. xxiii, col. 194.| But though this country should have received a fatal blow, there is still a duty incumbent upon its Ministers to use their most vigorous exertions to prevent the Court of France from being in a situation to dictate the terms of Peace. The sun of England may have set. But we will improve the twilight. We will prepare for the rising of that sun again. And I hope England may yet see many, many happy days.’

The best achievements of the brief government of Lord Shelburne were (first) the resolute defence, in its diplomacy at Paris and Versailles, of our territories in Canada, and (secondly) its consistent assertion of the principle that underlay a sentence contained in a former speech of the |Merits of the Shelburne Ministry.| Premier—a sentence which, at one time, was much upon men’s lips:—‘I will never consent,’ he had said, ‘that the King of England shall be a King of the Mahrattas.’ The 433merits, I venture to think, of that short Ministry, have had scant acknowledgment in our current histories. And the reason is, perhaps, not far to seek.

The popular history of George the Third’s reign has been, in a large degree, imbued with Whiggism. The historians most in vogue have had a sort of small apostolical succession amongst themselves, which has had the result of giving a strong party tinge to those versions of the course of political events in that reign which have most readily gained the public ear. When the full story shall come to be told, in a later day and from a higher stand-point, Lord Shelburne, not improbably, will be one among several statesmen whose reputation with posterity (in common—in some measure—with that of their royal master himself, it may even be) will be found to have been elevated, rather than lowered, by the process.

But, be that as it may, party intrigue, rather than ministerial incapacity, had to do, confessedly, with the rapid overthrow of the Government of July, 1782.

Personally, Lord Shelburne was in a position which, in several points of view, bears a resemblance to that in which another able statesman, who had to fight against a powerful coterie, was to find himself forty years later. But in Shelburne’s case, the struggle of the politician did not, as in Canning’s, break down the bodily vigour of the man. Lord Shelburne had twenty-two years of retirement yet before him, when he resigned the premiership in 1783. And they were years of much happiness.

Part of that happiness was the result of the domestic union just adverted to. Another part of it accrued from the rich Library which the research and attention of many years had gradually built up, and from the increased leisure that had now been secured, both for study and for the 434enjoyment of the choice society which gathered habitually at Lansdowne House and at Bowood.

Lord Shelburne’s retirement had been followed, in 1784, by his creation as Earl Wycombe and Marquess of Lansdowne. In the following year, he sold the Wycombe mansion and its charming park to Lord Carrington. Thenceforward, Bowood had the benefit, exclusively, of his taste and skill in landscape-gardening. Unfortunately, his next successor, far from continuing his father’s work, did much to injure and spoil it. But the third Marquess, in whom so many of his father’s best qualities were combined with some that were especially his own, made ample amends.

The exciting debates which grew out of the French Revolution and the ensuing events on the Continent, called Lord Lansdowne, now and then, into the old arena. But the domestic employments which have been mentioned, together with that which was entailed by a large and varied correspondence, both at home and abroad, were the things which chiefly filled up his later years. The Marquess died in London on the seventh of May, 1805. He was but sixty-eight years of age, yet he was then the oldest general officer on the army list, having been gazetted as a major-general just forty years before.

In order to acquire for the nation that precious portion of Lord Lansdowne’s Library which was in manuscript, the national purse-strings were now, for the first time, opened on behalf of the literary stores of the British Museum. Fifty-three years had passed since its complete foundation as a national institution, and exactly twice that number of years since the first public establishment of the Cottonian Library, yet no grant had been hitherto made by Parliament 435for the improvement of the national collections of books.

Four thousand nine hundred and twenty-five pounds was the sum given to Lord Lansdowne’s executors for his manuscripts. Besides the successive accumulations of State Papers heretofore mentioned, the Lansdowne Collection included other historical documents, extending in date from the reign of Henry the Sixth to that of George the Third; the varied Collections of William Petyt on parliamentary and juridical lore; those of Warburton on the topography and family history of Yorkshire, and of Holles, containing matter of a like character for the local concerns of the county of Lincoln; the Heraldic and Genealogical Collections of Segar, Saint George, Dugdale, and Le Neve; and a most curious series of early treatises upon music, which had been collected by John Wylde, who was for many years precentor of Waltham Abbey, in the time of the second of the Tudor monarchs.

The Lansdowne Collection did not contain very much of a classical character. Its strength, it has been seen already, lay in the sections of Modern History and Politics. The next important addition to the Library of the Museum—that of the manuscripts and printed books of Francis Hargrave—was likewise chiefly composed of political and juridical literature. But the third parliamentary acquisition brought to the Museum a store of classical wealth, both in manuscripts and in printed books. Hargrave’s Legal Library was bought in 1813. Charles Burney’s Classical Library was bought in 1818. In the biographical point of view neither of these men ran a career which offers much of narrative interest. The one career 436was that of a busy lawyer; the other, that of a laborious scholar. But to Burney’s life a few sentences may be briefly and fitly given.

The second Charles Burney was a younger son of the well-known historian of Music, who for more than fifty years was a prominent figure in the literary circles—and especially in the Johnsonian circle—of London; and in whose well-filled life a very moderate share of literary ability was made to go a long way, and to elicit a very resonant echo. That ‘clever dog Burney,’ as he was wont to be called by the autocrat of the dinner-table, had the good fortune to be the father of several children even more clever than himself. Their reputation enhanced his own.

Charles Burney, junior, was born at Lynn, in Norfolk, on the 10th of December, 1757. He was educated at the Charter House in London, at Caius College, Cambridge, and at King’s College, Aberdeen. At Aberdeen, Burney formed a friendship with Dr. Dunbar, a Scottish professor of some distinction, and an incident which grew, in after-years, out of that connection, determined the scene and character of the principal employments of Burney’s life. He devoted himself to scholastic labours, in both senses of the term; their union proved mutually advantageous, and as tuition gave leisure for literary labour, so the successful issues of that labour spread far and wide his fame as a schoolmaster. He was one of the not very large group of men who in that employment have won wealth as well as honour. It was finely said, many years ago—in one of the State Papers written by Guizot, when he was Minister of Public Instruction in France—‘the good schoolmaster must work for man, and be content to await his reward from God.’ In Burney’s case, the combined 437assiduity of an energetic man at the author’s writing-table, at the master’s desk, and also (it must in truthful candour be added) at his flogging block,[5] brought him a large fortune as well as a wide-spread reputation. This fortune enabled him to collect what, for a schoolmaster, I imagine to have been a Classical Library hardly ever rivalled in beauty and value. It was the gathering of a deeply read critic, as well as of an open-handed purchaser.

The bias of Dr. Burney’s learning and tastes in literature led him to a preference of the Greek classics far above the Latin. Naturally, his Library bore this character in counterpart. He aimed at collecting Greek authors—and especially the dramatists—in such a way that the collocation of his copies gave a sort of chronological view of the literary history of the books and of their successive recensions.

For the tragedians, more particularly, his researches were brilliantly successful. Of Æschylus he had amassed forty-seven editions; of Sophocles, one hundred and two; of Euripides, one hundred and sixty-six.

His first publication was a sharp criticism (in the Monthly Review) on Mr. (afterwards Bishop) Huntingford’s Collection of Greek poems entitled Monostrophica. This was followed, in 1789, by the issue of an Appendix to Scapula’s Lexicon; and in 1807 by a collection of the correspondence of Bentley and other scholars. Two years later, he gave to students of Greek his Tentamen de Metris ab Æschylo in choricis cantibus adhibitis, and to the youthful theologians his meritorious abridgment of Bishop Pearson’s 438Exposition of the Creed. In 1812, he published the Lexicon of Philemon.

The only Church preferments enjoyed by Dr. Burney were the rectory of St. Paul, Deptford, near London, and that of Cliffe, also in Kent. His only theological publication—other than the abridgment of Pearson—was a sermon which he had preached in St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1812. Late in life he was made a Prebendary of Lincoln.

Like his father, and others of his family, Charles Burney was a very sociable man. He lived much with Parr and with Porson, and, like those eminent scholars, he had the good and catholic taste which embraced in its appreciations, and with like geniality, old wine, as well as old books. He was less wise in nourishing a great dislike to cool breezes. ‘Shut the door,’ was usually his first greeting to any visitant who had to introduce himself to the Doctor’s notice; and it was a joke against him, in his later days, that the same words were his parting salutation to a couple of highwaymen who had taken his purse as he was journeying homewards in his carriage, and who were adding cruelty to robbery by exposing him to the fresh air when they made off.

Some of Dr. Burney’s choicest books were obtained when the Pinelli Library was brought to England from Italy. The prime ornament of his manuscript Collection, a thirteenth century copy of the Iliad, of great beauty and rich in scholia, was bought at the sale of the fine Library of Charles Towneley, Collector of the Marbles.

Although classical literature was the strength of the Burney Collection, it was also rich in some other departments. Of English newspapers, for example, he had brought together nearly seven hundred volumes of the 439seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, reaching from the reign of James the First to the reign of George the Third. No such assemblage had been theretofore formed, I think, by any Collector. He had also amassed nearly four hundred volumes containing materials for a history of the British Stage, which materials have subsequently been largely used by Mr. Genest, in his work on that subject. For Burney’s life-long study of the Greek drama had gradually inspired him with a desire to trace what, in a sense, may be termed its modern revival, in the grand sequel given to it by Shakespeare and his contemporaries. He had also collected about five thousand engraved theatrical portraits, and two thousand portraits of literary personages.

A large number of his printed books contained marginal manuscript notes by Bentley, Casaubon, Burmann, and other noted scholars. And in a series of one hundred and seventy volumes Burney had himself collected all the extant remains and fragments of Greek dramatic writers—about three hundred in number. These remains he had arranged under the collective title of Fragmenta Scenica Græca.

A splendid vellum manuscript of the Greek orators, in scription of the fourteenth century, had been obtained from Dr. Clarke, by whom it had been acquired during Lord Elgin’s Ottoman Embassy, and brought into England. It supplied lacunæ which are found wanting in all other known manuscripts. It completed an imperfect oration of Lycurgus, and another of Dinarchus. Another MS. of the Greek orators, of the fifteenth century, is only next in value to that derived from Clarke’s researches in the East, of 1800. There is also a very fine manuscript of the Geography of Ptolemy, with maps compiled in the fifteenth 440century, and two very choice copies of the Greek Gospels, one of which is of the tenth, and the other of the twelfth centuries.

In Latin classics, the Burney Manuscripts include a fourteenth century Plautus, containing no fewer than twenty plays—whereas a manuscript containing even twelve plays has long been regarded as a rarity. A fifteenth century copy of the mathematical tracts collected by Pappus Alexandrinus, a Callimachus of the same date, and a curious Manuscript of the Asinus Aureus of Apuleius, are also notable. The whole number of Classical Manuscripts which this Collector had brought together was stated, at the time of his death, to be three hundred and eighty-five.

Dr. Burney died on the twenty-eighth of December, 1817, having just entered upon his sixty-first year. He was buried at Deptford, amidst the lamentations of his parishioners at his loss.

For in Burney, too, the scholar and the Collector had not been suffered to dwarf or to engross the whole man. His parishioners assembled, soon after his death, to evince publicly their sense of what Death had robbed them of. The testimony then borne to his character was far better, because more pertinent, laudation, than is usually met with in the literature of tombstones. Those who had known the man intimately then said of him: ‘His attainments in learning were united with equal generosity and kindness of heart. His impressive discourses from the pulpit became doubly beneficial from the influence of his own example.’ The parishioners agreed to erect a monument to his memory, ‘as a record of their affection for their revered pastor, monitor, and friend; of their gratitude for his services, and of their unspeakable regret for his loss.’

441Another meeting was called shortly afterwards, with a like object, but of another sort. Despite his reverence for Busbeian traditions, Dr. Burney had known how to win the love of his pupils. |Annual Biography and Obituary, vol. iii, p. 225.| A large body of them met, under the chairmanship of the excellent John Kaye, then Regius Professor of Divinity at Cambridge, and afterwards Bishop of Lincoln, and they subscribed for the placing of a monument to their old master in Westminster Abbey.

On the twenty-third of February, 1818, the Trustees of the British Museum presented to the House of Commons a petition, praying that Dr. Burney’s Library should be acquired for the Public. The prayer of the petition was supported by Mr. Bankes and by Mr. Vansittart, and a Select Committee was appointed to inquire and report upon the application.

In order to an accurate estimate of the value of the Library, a comparison was instituted, in certain particulars, between its contents and those of the Collection already in the national Museum. In comparing the works of a series of twenty-four Greek authors, it was found that of those authors, taken collectively, the Museum possessed only two hundred and thirty-nine several editions, whereas Dr. Charles Burney had collected no fewer than seven hundred and twenty-five editions.[6] |Acquisition of the Burney Library by the Nation.| His Collection of the Greek dramatists was not only, as I have said, extensive, but it was arrayed after a peculiar and interesting manner. By making a considerable sacrifice of duplicate copies, he had brought his series of editions into an order which exhibited, 442at one view, all the diversities of text, recension, and commentary. His Greek grammarians were arrayed in like manner. And his collection of lexicographers generally, and of philologists, was both large and well selected.

The total number of printed books was nearly thirteen thousand five hundred volumes, that of manuscripts was five hundred and twenty; and the total sum given for the whole was thirteen thousand five hundred pounds.

It was estimated that the Collection had cost Dr. Burney a much larger sum, and that, possibly, if sold by public auction, it might have produced to his representatives more than twenty thousand pounds.

In the same year with the acquisition of the Burney Library, the national Collections were augmented by the purchase of the printed books of a distinguished Italian scholar long resident in France, and eminent for his contributions to French literature. |Collection of P. L. Ginguené. (Died 11 Nov., 1816.)| Pier Luigi Ginguené—author of the Histoire Littéraire d’Italie and a conspicuous contributor to the early volumes of the Biographie Universelle—had brought together a good Collection of Italian, French, and Classical literature. It comprised, amongst the rest, the materials which had been gathered for the book by which the Collector is now chiefly remembered, and extended, in the whole, to more than four thousand three hundred separate works, of which number nearly one thousand seven hundred related to Italian literature, or to its history. This valuable Collection was obtained by the Trustees—owing to the then depressed state of the Continental book-market—for one thousand pounds. And, in point of literary value, it may be described as the first—in point of price, as the cheapest—of a series of purchases which now began to be made on the Continent.

443A more numerous printed Library had been purchased together with a cabinet of coins and a valuable herbarium, at Munich, three years earlier, at the sale of the Collections of Baron Von Moll. His Library exceeded fourteen thousand volumes, nearly eight thousand of which related to the physical sciences and to cognate subjects. |Collection of Baron von Moll. (1815.)| The cost of this purchase, with the attendant expenses, was four thousand seven hundred and seventy pounds. The whole sum was defrayed out of the fund bequeathed by Major Arthur Edwards.[7]

These successive purchases, together with the Hargrave Collection—acquired in 1813—increased the theretofore much neglected Library by an aggregate addition of nearly thirty-five thousand volumes. And for four successive years (1812–15) Parliament made a special annual grant of one thousand pounds[8] for the purchase of printed books relating to British History.

The peculiar importance of the Hargrave Collection consisted in its manuscripts and its annotated printed books. The former were about five hundred in number, and were works of great juridical weight and authority, not merely the curiosities of black-letter law. Their Collector was the most eminent parliamentary lawyer of his day, but his devotion to the science of law had, to some degree, impeded his enjoyment of its sweets. During some of the best years of his life he had been more intent on increasing his legal lore than on swelling his legal 444profits. And thus the same legislative act which enriched the Museum Library, in both of its departments, helped to smooth the declining years of a man who had won an uncommon distinction in his special pursuit. Francis Hargrave died on the sixteenth of August, 1821, at the age of eighty.

Leaving now this not very long list of acquisitions made by the National Library, in the way of purchase, either at the public cost or from endowments, we have again to turn to a new and conspicuous instance of private liberality. Like Cracherode, and like Burney, Francis Henry Egerton belonged to a profession which at nearly all periods of our history—though in a very different degree in different ages—has done eminent honour and rendered large services to the nation, and that in an unusual variety of paths.

Each of these three clergymen is now chiefly remembered as a ‘Collector.’ Each of them would seem to have been placed quite out of his true element and sphere of labour, when assuming the responsibilities of a priest in the Church of England. Cracherode was scarcely more fitted for the work, at all events, of a preacher—save by the tacit lessons of a most meek and charitable life—than he was fitted to head a cavalry charge on the field of battle. Burney was manifestly cut out by nature for the work of a schoolmaster; although, as we have seen, he was able—late, comparatively, in life—so to discharge (for a very few years) the duties of a parish priest as to win the love of his flock. Egerton was unsuited to clerical work of almost any and every kind. Yet he, too, with all his eccentricities and his indefensible absenteeism, became a public benefactor. The last act of his life was to make a provision which has been fruitful in good, having a bearing—very 445real though indirect—upon the special duties of the priestly function, for which he was himself so little adapted. The bequests of Francis Egerton had, among their many useful results, the enabling of Thomas Chalmers to add one more to his fruitful labours for the Christian Church and for the world.

It may not, I trust, be out of place to notice in this connection, and as one among innumerable debts which our country owes specifically to its Church Establishment, the impressive and varied way in which the English Church has, at every period, inculcated the lesson (by no means, nowadays, a favourite lesson of ‘the age’) that men owe duties to posterity, as well as duties to their contemporaries. The fact bears directly on the subject of this book. Into every path of life many men must needs enter, from time to time, without possessing any peculiar and real fitness for it. In a path which (in the course of successive ages) has been trodden by some millions of men, there must needs have been a crowd of incomers who had been better on the outside. They were like the square men who get to be thrust violently into round holes. But, even of these misplaced men, not a few have learnt, under the teaching of the Church, that if they could not with efficiency do pulpit work or parish work, there was other work which they could do, and do perpetually. Men, for example, who loved literature could, for all time to come, secure for the poorest student ample access to the best books, and to the inexhaustible treasures they contain. Cracherode did this. Burney helped to do it. Egerton not only did the like, in his degree, in several parts of England, but he enabled other and abler men to write new books of a sort which are conspicuously adapted to add to the equipment of divines for their special duty and work in the world. 446Neglecting to learn many lessons which the Church teaches, to her clergy as well as to laymen, he had at least learnt one lesson of practical and permanent value.

Hence it is that, in addition to the matchless roll of English worthies which, in her best days, the Church has furnished—in that long line of men, from her ranks, who have done honour to her, and to England, under every point of view—she can show a subsidiary list, comprising men whose benefactions are more influential than were, or could have been, the labours of their lives; men of the sort who, being dead, can yet speak, and to much better purpose than ever they could speak when alive. Among such is the Churchman whose testamentary gifts have now very briefly to be mentioned.

Francis Henry Egerton was a younger son of John Egerton, Bishop of Durham, by the Lady Anna Sophia Grey, daughter and coheir of Henry Grey, Duke of Kent. He was born on the eleventh of November, 1756. The Bishop of Durham was fifth in descent from the famous Chancellor of England, Thomas Egerton, Viscount Brachley, to whom, as he lay upon his death-bed, Bacon came with the news of King James’s promise to make him an Earl. Before the patent could be sealed, the exchancellor, it will be remembered, was dead, and James, to show his gratitude to the departed statesman, sold for a large sum the Earldom of Bridgewater to the Chancellor’s son. Eventually, of that earldom Francis Henry Egerton was, in his old age, the eighth and last inheritor.

Mr. Egerton was educated at Eton and at All Souls. He took his M.A. in 1780, and in the following year was presented, by his relative, Francis, Duke of Bridgewater—the father of inland navigation in Britain—to the Rectory 447of Middle, in Shropshire, a living which he held for eight and forty years.

He was a toward and good scholar. From his youth he was a great reader and a lover of antiquities, as well as a respectable philologist. His foible was an overweening although a pardonable pride in his ancestry. That ancestry embraced what was noblest in the merely antiquarian point of view, along with the grand historical distinctions of state service rendered to Queen Elizabeth, and of a new element introduced into the mercantile greatness of England under George the Third. A man may be forgiven for being proud of a family which included the servant of Elizabeth and friend of Bacon, as well as the friend of Brindley. But the pride, as years increased, became somewhat wearisome to acquaintances; though it proved to be a source of no small profit to printers and engravers, both at home and abroad. Mr. Egerton’s writings in biography and genealogy are very numerous. They date from 1793 to 1826. Some of them are in French. All of them relate, more or less directly, to the family of Egerton.

In the year 1796, he appeared as an author in another department, and with much credit. His edition of the Hippolytus of Euripides is also noticeable for its modest and candid acknowledgment of the assistance he had derived from other scholars. He afterwards collected and edited some fragments of the odes of Sappho. The later years of his life were chiefly passed in Paris. His mind had been soured by some unhappy family troubles and discords, and as years increased a lamentable spirit of eccentricity increased with them. It had grown with his growth, but did not weaken with his loss of bodily and mental vigour.

448One of the most noted manifestations of this eccentricity was but the distortion of a good quality. He had a fondness for dumb animals. He could not bear to see them suffer by any infliction,—other than that necessitated by a love of field sports, which, to an Englishman, is as natural and as necessary as mother’s milk. At length, the Parisians were scandalised by the frequent sight of a carriage, full of dogs, attended with as much state and solemnity as if it contained ‘milord’ in person. To his servants he was a most liberal master. He provided largely for the parochial service and parochial charities of his two parishes of Middle and Whitchurch (both in Shropshire). He was, occasionally, a liberal benefactor to men of recondite learning, such as meet commonly with small reward in this world.[9] But much of his life was stamped with the ineffaceable discredit of sacred functions voluntarily assumed, yet habitually discharged by proxy.

On the death, in 1823, of his elder brother—who had become seventh Earl of Bridgewater, under the creation of 1617, on the decease of Francis third Duke and sixth (Egerton) Earl—Francis Henry Egerton became eighth Earl of Bridgewater. But he continued to live chiefly in Paris, where he died, in April, 1829, at the age of seventy-two years. With the peerage he had inherited a 449very large estate, although the vast ducal property in canals had passed, as is well known, in 1803, to the Leveson-Gowers.

Part of Lord Bridgewater’s leisure at Paris was given to the composition of a largely-planned treatise on Natural Theology. But the task was far above the powers of the undertaker. He had made considerable progress, after his fashion, and part of what he had written was put superbly into type, from the press of Didot. Very wisely, he resolved to enable abler men to do the work more efficiently. And this was a main object of his remarkable Will.

That portion of the document which eventually gave to the world the well-known ‘Bridgewater Treatises’ of Chalmers, Buckland, Whewell, Prout, Roget, and their fellows in the task, reads thus:—

‘I give and bequeath to the President of the Royal Society the sum of eight thousand pounds, to be applied according to the order and direction of the said President of the Royal Society, in full and without any diminution or abatement whatsoever, in such proportions and at such times, according to his discretion and judgment, and without being subject to any control or responsibility whatsoever, to such person or persons as the said President for the time being of the aforesaid Royal Society shall or may nominate or appoint and employ. And it is my will and particular request that some person or persons be nominated and appointed by him to write, print, publish, and expose to public sale, one thousand copies of a work “On Power, Wisdom, and Goodness of God, as manifested in the Creation,” illustrating such work by all reasonable arguments; as, for instance, the variety and formation of God’s creatures, in the animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms; 450the effect of digestion, and thereby of conversion; the construction of the hand of man, and an infinite variety of arrangements; as also by discoveries, ancient and modern, in arts, sciences, and in the whole extent of literature. And I desire that the profits arising from and out of the circulation and sale of the aforesaid work shall be paid by the said President of the said Royal Society, as of right, as a further remuneration and reward to such persons as the said President shall or may so nominate, appoint, and employ as aforesaid. And I hereby fully authorise and empower the said President, in his own discretion, to direct and cause to be paid and advanced to such person or persons during the printing and preparing of the said work the sum of three hundred pounds, and also the sum of five hundred pounds sterling to the same person or persons during the printing and preparing of the said work for the press, out of, and in part of, the same eight thousand pounds sterling. And I will and direct that the remainder of the said sum of eight thousand pounds sterling, or of the stocks or funds wherein the same shall have been invested, together with all interest, dividend, or dividends accrued thereon, be transferred, assigned, and paid over to such person or persons, their or his executors, administrators, or assigns, as shall have been so nominated, appointed, and employed by the said President of the said Royal Society, at the instance and request of the same President, as and when he shall deem the object of this bequest to have been fully complied with by such person or persons so nominated, appointed, and employed by him as aforesaid.’

What was done by the Trustees under this part of Lord Bridgewater’s Will, and with what result, is known to all readers. That other portion of the Will which relates to his bequest to the British Museum reads thus:—‘I give 451and bequeath to the Trustees for the time being of the British Museum at Montagu House, in London, to be there deposited ... for the use of the said Museum, in conformity with the rules, orders, and regulations of the said establishment, absolutely and for ever, all and every my Collection of Manuscripts as hereinafter particularly described. That is to say, the several volumes of Manuscripts, and all papers, parchments (written or printed), and all letters, despatches, registers, rolls, documents, evidences, authorities and signatures, and all impressions of seals and marks, of every description and sort, and of what nature or kind, severally and generally belonging to my Collection of Manuscripts, or in my possession, stamped with my arms or otherwise (except such letters, notes, papers, &c.), as are hereinafter directed to be burned and destroyed [‘two words cancelled, Bridgewater’], in the discretion of my Trustees and Executors hereinafter appointed; and also save and except all such letters, papers, and writings as are attached to and accompanying the printed books specifically bequeathed by me to the Library at Ashridge, and which said last-mentioned letters, papers, and writings are also, if I mistake not, stamped with my arms. And I also will and require that all and every the aforesaid manuscripts, papers, parchments (written or printed), letters, despatches, registers, rolls, documents, evidences, authorities, signatures, impressions of seals and marks of every description and sort, and every other Manuscript or Manuscripts appertaining to my said Collection whatsoever and wheresoever, or which shall or may hereafter, during my life, be added thereto (but not private letters, notes, or memorandums of any sort or kind, which I direct to be burned or destroyed), shall, within the space of two years from the day of my decease, be collected and removed to the British Museum as aforesaid, 452under the particular care, superintendence, and direction of Eugene Auguste Barbier, one of my Trustees and Executors hereinafter appointed; for which particular service I give and bequeath to him, the said Eugene Auguste Barbier, the sum of two thousand pounds sterling. I also give, bequeath, and demise unto the said Trustees of the British Museum all my estate, lands, parcels of land, ground, hereditaments and appurtenances, situate in the parish of Whitchurch-cum-Marbury, or in any other parish or place in the Counties of Salop or Chester, or in either or both of the said Counties, and also all the trees growing thereon, and all seats, sittings, and pews in the Parish Church of Whitchurch-cum-Marbury aforesaid, all or any of which I shall or may have bought or purchased, and which now belong to me by right of purchase, descent, or otherwise, to have and to hold the same estate, lands, parcels of land, ground, hereditaments and appurtenances, to them the said Trustees of the said British Museum for the time being for ever, upon the trusts nevertheless, and to and for the ends, intents, and purposes hereinafter particularly mentioned, expressed, and declared; that is to say, that the trees growing on the aforesaid estate, lands, parcels of lands, ground, hereditaments, and appurtenances, shall not be cut or brought down or destroyed, but shall and may be suffered to grow during their natural life, and that the smaller trees only may be thinned here and there, with care and judgment, so as to promote the growth of the larger trees; and that the same estate, lands, parcels of land, ground, hereditaments and appurtenances, seats, sittings or pews, or any part thereof, shall not be susceptible of being let, underlet or rented, by or to any person or persons who shall hold, have, take, or rent any estate, farm, lands, or property of or from the family of Egerton, or of or from any person or 453persons having that name, or of or from the Rector of Whitchurch-cum-Marbury aforesaid for the time being; and upon further trust that they the said Trustees of the British Museum for the time being do and shall lay out and apply the rents, issues, and profits which shall from time to time arise from and out of the said estate, lands, parcels of land, ground, hereditaments and appurtenances, in the purchase of manuscripts for the continual augmentation of the aforesaid Collection of Manuscripts. I further will and direct that my said Trustees hereinafter appointed, within the space of eighteen calendar months after my decease, do lay out and invest in the Three per cent. Consolidated stocks or funds of England, in the names of the Trustees of the British Museum for the time being, or in such names and for such account as the said Trustees shall direct, the sum of seven thousand pounds sterling, the interest and dividends whereof, as the same shall from time to time become due and payable, I desire and direct shall and may be paid over by the said Trustees to such person or persons as shall from time to time be charged with the care and superintendence of the said Collection of Manuscripts. I also give, grant, bequeath, and devise unto my Trustees hereinafter appointed all and singular my house, land, tenements, hereditaments, and appurtenances at or near Little Gaddesden, in the County of Herts, upon trust that they my said Trustees do and shall, during their joint lives and the life of the survivor of them, let and demise the same for such term or time as they shall think fit, for the best rent that can be had and gotten for the same; but the same premises, under no circumstances, to be let, underlet, or rented by or to any person or persons who shall have, hold, take, or rent any estate, farm, or property of or from the family of Egerton, or any person or persons bearing that name, and do and 454shall pay over the rents, issues, and profits thereof, as and when received, to the Trustees for the time being of the British Museum aforesaid, to be laid out and applied by such last-mentioned Trustees in the service and for the continued augmentation of the said Collection of Manuscripts; and from and after the decease of the survivor of them my said Trustees hereinafter appointed, I give and devise the said house, land, tenements, hereditaments and appurtenances, unto and for the use of the proprietor or proprietors of the Manor and Estate of Ashridge, his heirs and assigns for ever. And as to all the rest, residue and remainder of my real and personal estate and effects, of every nature and kind soever and wheresoever situate, not hereinbefore disposed of, or availably so, for the purposes intended, I give, devise, and bequeath the same to my said Trustees, upon trust that they my said Trustees do pay over and transfer the same to the said Trustees of the British Museum, and do otherwise render the same available for the service of and towards maintaining, preserving, keeping up, improving, augmenting, and extending, as opportunities may offer, |Will of Francis Henry, Earl of Bridgewater. (Official copy.)| my said Collection of Manuscripts so deposited in the British Museum as aforesaid, in the most advantageous manner, according to their judgment and discretion.’

The eccentricity of which I have spoken showed itself in the successive changes of detail and other modifications which these bequests underwent before the testator’s death. What with the Will and its many codicils, the documents, collectively, came to be of a kind which might task the acumen of a Fearne or a St. Leonards. But the drift of the Will was undisturbed. The restrictions as to the underletting of the Whitchurch estate, and the like, were now limited by codicils to a prescribed term of years after 455the testator’s death; power was given to the Museum Trustees to sell, also after a certain interval, the landed estate bequeathed for the purchase of manuscripts, should it be deemed conducive to the interest of the Library so to do; and an additional sum of five thousand pounds was given to the Trustees for the further increase of the Collection of Manuscripts, and for the reward of its keeper, in lieu of the residuary interest in the testator’s personal estate.

On the 10th of March, 1832, the Trustees resolved that the yearly proceeds of the last-named bequest should be paid to the Librarians in charge of the MSS., but that their ordinary salaries, on the establishment, should be diminished by a like amount.

The Manuscripts bequeathed by Lord Bridgewater comprise a considerable collection of the original letters of the Kings, Queens, Statesmen, Marshals, and Diplomatists, of France; another valuable series of original letters and papers of the authors and scientific men of France and of Italy; many papers of Italian Statesmen; and a portion of the donor’s own private correspondence. The latter series of papers includes, amongst others, letters by Andres, D’Ansse de Villoisin, the Prince of Aremberg, Auger, Barbier, the Duke of Blacas, Bodoni, Boissonade, Bonpland, Canova, Cuvier, Ginguené, Humboldt, Valckenaer, and Visconti. Some of these are merely letters of compliment. Others—and, in an especial degree, those of D’Ansse de Villoisin, of Boissonade, of Ginguené, of Humboldt, and of Visconti—contain much interesting matter on questions of archæology, art, and history.

The earliest additions to the Egerton Collection were made by the Trustees in May, 1832. In the selection of MSS. for purchase the Trustees, with great propriety, have given a preference—on the whole; not exclusively—to that 456class of documents of which the donor’s own Collection was mainly composed—the materials, namely, of Continental history. Amongst the earliest purchases of 1832 was a curious Venetian Portolano of the fifteenth century. |The Hardiman MSS. on Irish Archæology and English History.| In the same year a large series of Irish Manuscripts, collected by the late John Hardiman, was acquired. This extends from the Egerton number ‘74’ to ‘214’; and from the same Collector was obtained the valuable Minutes of Debates in the House of Commons, taken by Colonel Cavendish, between the years—so memorable in our history—from 1768 to 1774.[10] In the year 1835, a large collection of manuscripts illustrative of Spanish history was purchased from Mr. Rich, a literary agent in London, and another large series of miscellaneous manuscripts—historical, political, and literary—from the late bookseller, Thomas Rodd. From the same source another like collection was obtained in 1840. An extensive series of French State Papers was acquired (by the agency of Messrs. Barthes and Lowell) in 1843; and also, in that year, a collection of Persian MSS. In the following year a curious series of drawings, illustrating the antiquities, manners, and customs of China, was obtained; and, in 1845, another valuable series of French historical manuscripts.

Meanwhile, the example set by Lord Bridgewater had incited one of those many liberal-minded Trustees of the British Museum who have become its benefactors by augmentation, as well as by faithful guardianship, to follow it in exactly the same track. |Augmentation of Lord Bridgewater’s Gift by that of Lord Farnborough, 1838.| Charles Long, Lord Farnborough, bequeathed (in 1838) the sum of two thousand eight hundred and seventy-two pounds in Three per cent. Consols, specifically as an augmentation of the Bridgewater 457fund. Lord Farnborough’s bequest now produces eighty-six pounds a year; Lord Bridgewater’s, about four hundred and ninety pounds a year. Together, therefore, they yield five hundred and seventy pounds, annually, for the improvement of the National Collection of Manuscripts.

In 1850 and 1852, an extensive series of German Albums—many of them belonging to celebrated scholars—was acquired. These are now ‘Egerton MSS. 1179’ to ‘1499,’ inclusive, and ‘1540’ to ‘1607.’ A curious collection of papers relating to the Spanish Inquisition was also obtained in 1850. |Egerton MSS. 1704–1756.| |Ib. 1758–1772.| In 1857, the important historical collection, known as ‘the Bentinck Papers,’ was purchased from Tycho Mommsen, of Oldenburgh. In the following year, another series of Spanish State Papers, and also the Irish Manuscripts of Henry Monck Mason;—in 1860, a further series of ‘Bentinck Papers,’—and in 1861, an extensive collection of the Correspondence of Pope and of Bishop Warburton, were successively acquired.

To these large accumulations of the materials of history were added, in the succeeding years, other important collections of English correspondence, and of autograph MSS. of famous authors; and also a choice collection of Spanish and Portuguese Manuscripts brought together by Count da Ponte, and abounding with historical information. |Egerton MSS. 2047–2064.| To this an addition was made last year (1869) of other like papers, amongst which are notable some Venetian Relazioni; papers of Cardinals Carlo Caraffa and Flavio Orsini; and some letters of Antonio Perez. |Ib. 2077–2084.| In 1869, there was also obtained, by means of the conjoined Egerton and Farnborough funds, |Ib. 2087–2099.| a curious parcel of papers relating to the early affairs of the Corporation and trade of Dover, from the year 1387 to 1678; |Ib. 2086; 2100.| together with some other papers illustrative of the cradle-years of our Indian empire.