To the courtesy of the editors of the “Argonaut,” “Out West,” “Criterion,” “Arena” and “Munsey’s”—in which publications many of these sketches have already seen print—is due their reappearance in more permanent form.

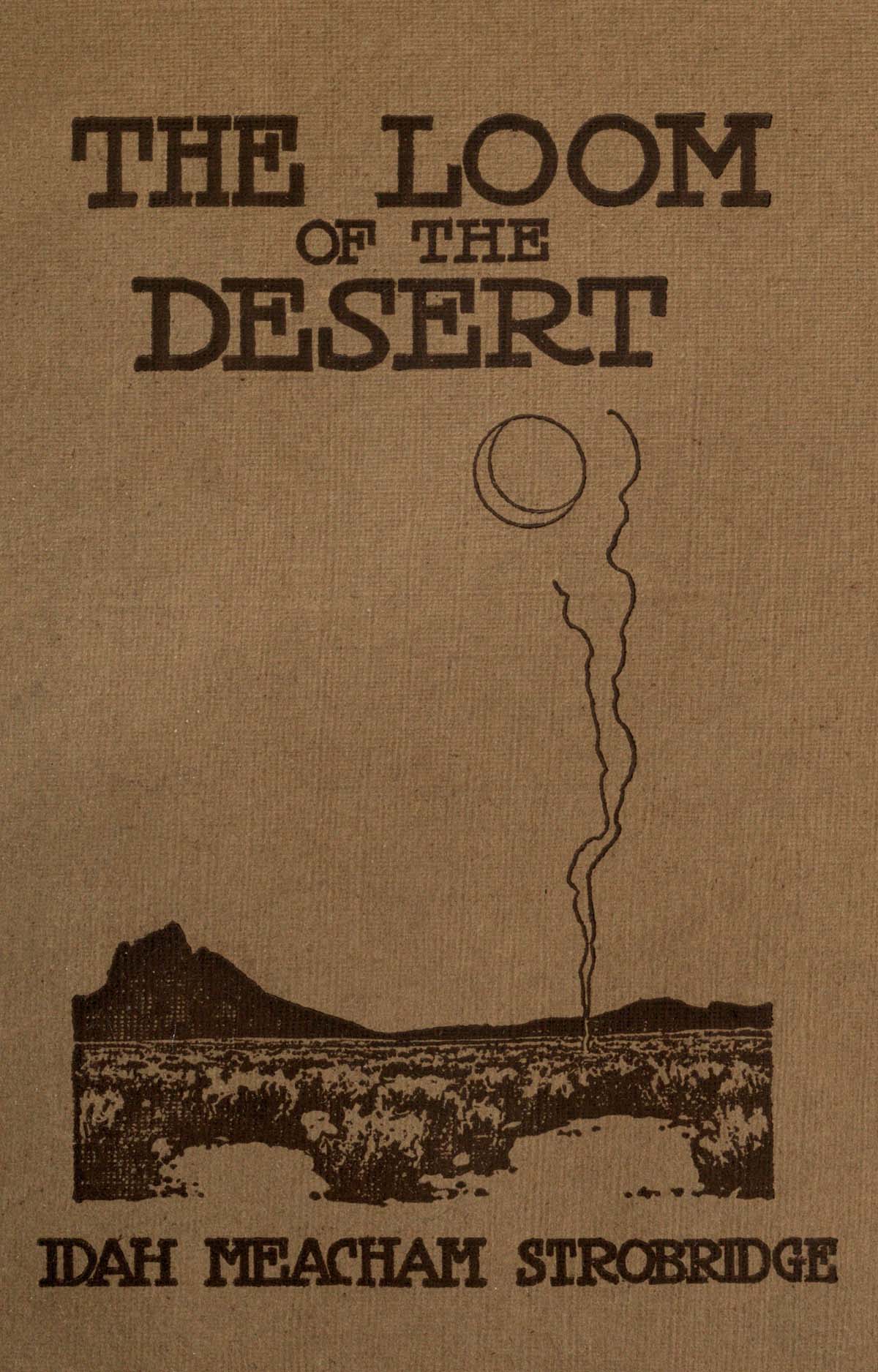

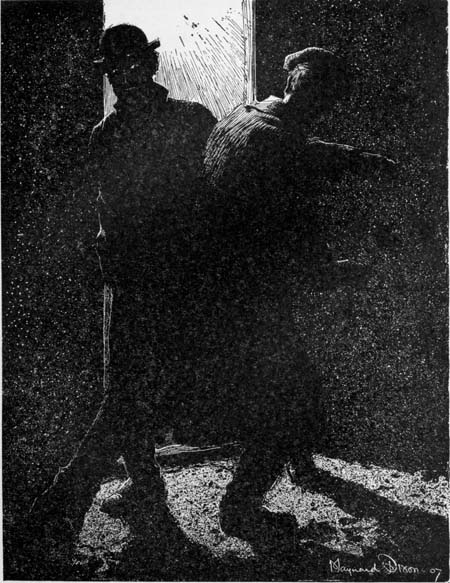

“The boy swayed backward—backward.”—Page 10

The Loom of the Desert

by

Idah Meacham Strobridge

LOS ANGELES

MCMVII

Copyright, 1907, by

Idah Meacham Strobridge

Printed by the

Baumgardt Publishing Company

Los Angeles, California

Of this autographed edition of

“The Loom of the Desert,” one

thousand copies were made; this

one being number 351

Idah M. Strobridge

MARRIED: In Newark, New Jersey, Thursday,

evening, June the Second, 1852, Phebe

Amelia Craiger of Newark, to George Washington

Meacham of California.

To these—my dearest;

the FATHER and MOTHER who are my comrades still,

I dedicate

these stories of a land where we were pioneers.

There, in that land set apart for Silence, and Space, and the Great Winds, Fate—a grim, still figure—sat at her loom weaving the destinies of desert men and women. The shuttles shot to and fro without ceasing, and into the strange web were woven the threads of Light, and Joy, and Love; but more often were they those of Sorrow, or Death, or Sin. From the wide Gray Waste the Weaver had drawn the color and design; and so the fabric’s warp and woof were of the desert’s tone. Keeping this always well in mind will help you the better to understand those people of the plains, whose lives must needs be often sombre-hued.

MISS GLENDOWER sat on the ranch-house piazza, shading her eyes from the white glare of the sun by holding above them—in beautiful, beringed fingers—the last number of a Boston magazine. It was all very new and delightful to her—this strange, unfinished country, and each day developed fresh charm. As a spectacle it was perfect—the very desolation and silence of the desert stirred something within her that the Back Bay had never remotely roused. Viewed from the front row of the dress circle, as it were, nothing could be more fascinating to her art-loving sense than this simple, wholesome life lived out as Nature teaches, and to feel that, for the time, the big, conventional world of wise insincerities was completely shut away behind those far purple mountains out of which rose the desert sun.

As for becoming an integral part of all this one’s self—Ah, that was a different matter! The very thought of her cousin, Blanche Madison, and Roy—her husband—deliberately turning their backs on the refinements of civilization, and accepting the daily drudgery and routine of life on a cattle ranch, filled her with wondering amazement. When she fell to speculating on what their future years here would[2] be, she shuddered. From the crown of her sleek and perfectly poised little head, to the hollowed sole of her modishly booted foot, Miss Audrey Glendower was Bostonian.

Still, for the short space of time that she waited Lawrence Irving’s coming, life here was full of charm for her—its ways were alluring, and not the least among its fascinations was Mesquite.

She smiled amusedly as she thought of the tall cowboy’s utter unconsciousness of any social difference between them—at his simple acceptance of her notice. Miss Glendower was finding vast entertainment in his honest-hearted, undisguised adoration. She had come West for experiences, and one of the first (as decidedly the most exciting and interesting) had been found in Mesquite. Besides, it gave her something to write of when she sent her weekly letter to Lawrence Irving. Sometimes she found writing to him a bit of a bore—when topics were few.

But Mesquite—— The boy was a revelation of fresh surprises every day. There was no boredom where he was. Amusing; yes, that was the word. There he was now!—crossing the bare and hard beaten square of gray earth that lay between the ranch house and the corrals. Though he was looking beyond the piazza to where the other boys were driving a “bunch” of bellowing, dust-stirring cattle into an enclosure, yet she felt it was she whom his eyes saw. He was coming straight toward the house—and her. She knew it. Miss Glendower knew many things, learned in the varied experience of her eight-and-twenty years. Her worldly wisdom was more—much more—than his would be at double his present age. Mesquite was twenty.

He looked up with unconcealed pleasure in her presence[3] as he seated himself on the piazza—swinging his spurred heels against each other, while he leaned his head back against one of the pillars. Miss Glendower’s eyes rested on the burned, boyish face with delight. There was something so näive, so sweetly childish about him. It was simply delicious to hear his “Yes, ma’am,” or his “Which?” Just now his yellow hair lay in little damp rings on his forehead, like a baby’s just awakened from sleep. He sat with his big, dust-covered sombrero shoved back from a forehead guiltless of tan or freckles as the petals of a white rose. But the lower part of his face was roughened by wind and burned by the sun to an Indian red, making the blue eyes the bluer—those great, babyish eyes that looked out with a belying innocence from under their marvelous fringe of upcurling lashes. The blue eyes were well used to looking upon sights that would have shocked Miss Glendower’s New England training, could she have known; and the babyish lips were quite familiar with language that would have made her pale with horror and disgust to hear. But then, she didn’t know. Neither could he have understood her standpoint.

He was only the product of his environment, and one of the best things that it had taught him was to have no disguises. So he sat today looking up at his lady with all his love showing in his face.

Then, in the late afternoon warmth, as the day’s red ball of burning wrath dropped down behind the western desert rim of their little world, he rode beside her, across sand hills where sweet flowers began to open their snow-white petals to the night wind’s touch, and over barren alkali flats to the postoffice half a dozen miles away.

[4]There was only one letter waiting for Miss Glendower that night. It began:

“I will be with you, my darling, twenty-four hours after you get this. Just one more day, Love, and I may hold you in my arms again! Just one more week, and you will be my wife, Audrey. Think of it!”

She had thought; she was thinking now. She was also wondering how Mesquite would take it. She glanced at the boy as she put the letter away and turned her horse’s head toward home. Such a short time and she would return to the old life that, for the hour, seemed so strangely far away! Now—alone in the desert with Mesquite—it would not be hard to persuade herself that this was all there was of the world or of life.

As they loped across the wide stretch of desert flats that reached to the sand hills, shutting the ranch from sight, the twilight fell, and with it came sharp gusts of wind that now and then brought a whirl of desert dust. Harder and harder it blew. Nearer and nearer—then it fell upon them in its malevolence, to catch them—to hold them in its uncanny clasp an instant—and then, releasing them, go madly racing off to the farther twilight, moaning in undertone as it went. Then heat lightning struck vividly at the horizon, and the air everywhere became surcharged with the electric current of a desert sand storm. They heard its roar coming up the valley. Audrey Glendower felt her nerves a-tingle. This, too, was an experience! In sheer delight she laughed aloud at the excitement showing in the quivering horses—their ears nervously pointing forward, and their nostrils distended, as with long, eager strides they pounded away over the wind-beaten levels.

Then the storm caught them at its wildest. Suddenly[5] a tumble-weed, dry and uprooted from its slight moorings somewhere away on the far side of the flats, came whirling toward them broadside in the vortex of a mad rush of wind in which—without warning—they were in an instant enveloped. As the great, rolling, ball-like weed struck her horse, Miss Glendower took a tighter grip on the reins and steadied herself for the runaway rush into the dust storm and the darkness. The wild wind caught her, shrieked in her ears, tore at her habit as though to wrest it from her body, dragged at the braids of heavy hair until—loosened—the strands whipped about her head, a tangled mass of stinging lashes.

She was alone—drawn into the maelstrom of the mad element; alone—with the fury of the desert storm; alone—in the awful darkness it wrapped about her, the darkness of the strange storm and the darkness of the coming night. The frightened, furious horse beneath her terrified her less than the weird, rainless storm that had so swiftly slipped in between her and Mesquite, carrying her away into its unknown depths. Where was he? In spite of the mastering fear that was gaining upon her, in spite of her struggle for courage, was a consciousness which told her that more than all else—that more than everyone else in the world—it was Mesquite she wanted. Had others, to the number of a great army, ridden down to her rescue she would have turned away from them all to reach out her arms to the boy vaquero. Perhaps it was because she had seen his marvelous feats of daring in the saddle (for Mesquite was the star rider of the range), and she felt instinctively that he could help her as none other; perhaps it was because of the past days that had so drawn him toward her; perhaps (and most likely) it was because[6] he had but just been at her side. However it might be, she was praying with all her soul for his help—for him to come to her—while mile after mile she rode on, unable to either guide or slacken the stride of her horse. His pace had been terrific; and not until it had carried him out of the line of the storm, and up from the plain into the sand hills, did he lessen his speed. Then the hoofs were dragged down by the heavy sand, and the storm’s strength—all but spent—was left away back on the desert.

She felt about her only the softest of West winds; the dust that had strangled her was gone, and in its place was the syringa-like fragrance of the wild, white primroses, star-strewing the earth, as the heavens were strewn with their own night blossoms.

Just above the purple-black bar of the horizon burned a great blood-red star in the sky. It danced and wavered before her—rising and falling unsteadily—and she realized that her strength was spent—that she was falling. Then, just as the loosened girth let the saddle turn with her swaying body, a hand caught at her bridle-rein, and——

Ah, she was lying sobbing and utterly weak, but unutterably happy, on Mesquite’s breast—Mesquite’s arms about her! She made no resistance to the passionate kisses the boyish lips laid half fearfully on her face. She was only glad of the sweetness of it all; just as the sweetness of the evening primroses (so like the fragrance of jasmine, or tuberose, or syringa) sunk into her senses. So she rested against his breast, seeing still—through closed eyelids—the glowing, red star. She was unstrung by the wild ride and the winds that had wrought on her nerves. It made yielding so easy.

At last she drew back from him; and instantly his[7] arms were unlocked. She was free! Not a second of time would he clasp her unwillingly. Neither had spoken. Nor, after resetting the saddle, when he took her again in his arms and lifted her, as he would a little child, upon her horse, did they speak. Only when the ranch buildings—outlined against the darkness—showed dimly before them, and they knew that the ride was at an end, did he voice what was uppermost in his mind.

“Yo’ don’t—— Yo’ ain’t—— Oh, my pretty, yo’ ain’t mad at me, are yo’?”

“No, Mesquite,” came the softly whispered answer.

“I’m glad o’ that. Shore, I didn’t mean fur to go an’ do sech a thing; but—— Gawd! I couldn’t help it.”

But when lifting her down at the ranch-house gate he would have again held her sweetness a moment within his clasp, Miss Glendower (she was once again Miss Glendower of the great world) let her cool, steady voice slip between:

“The letter I got tonight is from the man I am to marry in a week. He will be here tomorrow. But, I want to tell you—— Mesquite—— I want you to know that I—I shall always remember this ride of ours. Always.”

Mesquite did not answer.

“Good-night, Mesquite.” She waited. Still there was no reply.

Mesquite led the horses away and Miss Glendower turned and went into the house. Being an uneducated cowboy he was remiss in many matters of courtesy.

When Lawrence Irving arrived at the Madison ranch, his host, in the list of entertainment he was offering the Bostonian, promised an exhibition of[8] bronco riding that would stir even the beat of that serene gentleman’s well regulated pulse.

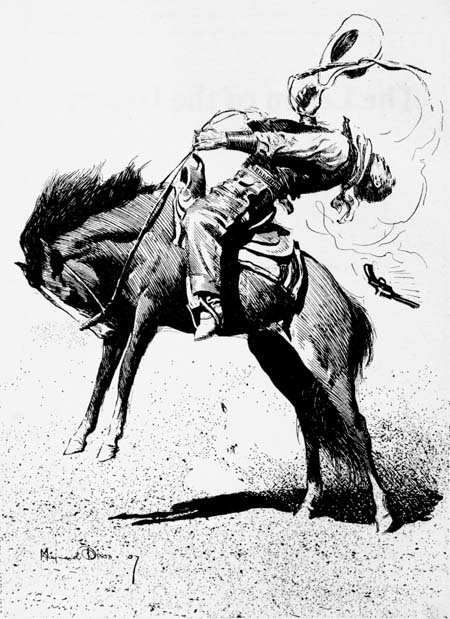

“This morning,” said Madison, “I was afraid that I wouldn’t be able to get my star bronco buster out for your edification, Lawrence, for the boys have been telling me that he has been ‘hitting the jug’ pretty lively down at the store for the past twenty-four hours (he’s never been much of a drinker, either), but when I told him Miss Glendower wanted to show you the convolutions of a bucking horse, it seemed to sober him up a bit, and he not only promised to furnish the thrills, but to do the business up with all the trimmings on—for he’s going to ride ‘Sobrepaso,’ a big, blaze-face sorrel that they call ‘the man killer,’ and that every vaquero in the country has given up unconquered. Mesquite himself refused to mount him again, some time ago; but today he is in a humor that I can’t quite understand—even allowing for all the bad whiskey that he’s been getting away with—and seems not only ready but eager to tackle anything.”

“I’m grateful to you, Rob,” began Irving, “for——”

“Oh, you’ll have to thank Audrey for the show! Mesquite is doing it solely for her sake. He has been her abject slave ever since she came.”

Both men laughed and looked at Miss Glendower, who did not even smile. It might have been that she did not hear them. They rose and went out to the shaded piazza where it was cooler. The heat was making Miss Glendower look pale.

They, and the ranch hands who saw “Sobrepaso” (“the beautiful red devil,” Mrs. Madison called him) brought out into the gray, hard beaten square that formed the arena, felt a thrill of nervous expectancy—a chilling thrill—as Mesquite made ready to mount.[9] The horse was blindfolded ere the saddle was thrown on; but with all the fury of a fiend he fought—in turn—blanket, and saddle, and cincha. The jaquima was slipped on, the stirrups tied together under the horse’s belly, and all the while his squeals of rage and maddened snorts were those of an untamed beast that would battle to the death. The blind then was pulled up from his eyes, and—at the end of a sixty-foot riata—he was freed to go bucking and plunging in a fury of uncontrolled wrath around the enclosure. At last sweating and with every nerve twitching in his mad hatred of the meddling of Man he was brought to a standstill, and the blind was slipped down once more. He stood with all four feet braced stiffly, awkwardly apart, and his head down, while Mesquite hitched the cartridge belt (from which hung his pistol’s holster) in place; tightened the wide-brimmed, battered hat on his head; slipped the strap of a quirt on his wrist; looked at the fastenings of his big-rowelled, jingling spurs; and then (with a quick, upward glance at Miss Glendower—the first he had given her) he touched caressingly a little bunch of white primroses he had plucked that morning from their bed in the sand hills and pinned to the lapel of his unbuttoned vest.

Mesquite had gathered the reins into his left hand, and was ready for his cat-like spring into place. His left foot was thrust into the stirrup—there was the sweep of a long leg thrown across the saddle—a sinuous swing into place, and Mesquite—“the star rider of the range” had mounted the man killer. Quickly the blind was whipped up from the blood-shot eyes, the spurred heels gripped onto the cincha, there was a shout from his rider and a devilish sound from the mustang as he made his first upward leap, and then went[10] madly fighting his way around and around the enclosure.

Mesquite sat the infuriated animal as though he himself were but a part of the sorrel whirlwind. His seat was superb. Miss Glendower felt a tremor of pride stir her as she watched him—pride that her lover should witness this matchless horsemanship. She was panting between fear and delight while she watched the boy’s face (wearing the sweet, boyish smile—like, yet so unlike—the smile she had come to know in the past weeks), and the yellow curls blowing back from the bared forehead.

“Sobrepaso” rose in his leaps to great heights—almost falling backward—to plunge forward, with squeals of rage that he could not unseat his rider. The boy sat there, a king—king of his own little world, while he slapped at the sorrel’s head and withers with the sombrero that swung in his hand. Plunging and leaping, round and round—now here and now there—about the enclosure they went, the horse a mad hurricane and his rider a centaur. Mesquite was swayed back and forth, to and fro, but no surge could unseat him. Miss Glendower grew warm in her joy of him as she looked.

Then, somehow (as the “man killer” made another great upward leap) the pistol swinging from Mesquite’s belt was thrown from its holster, and—striking the cantle of the saddle as it fell—there was a sharp report, and a cloud-like puff (not from the dust raised by beating hoofs), and a sound (not the terrible sounds made by a maddened horse), and the boy swayed backward—backward—with the boyish smile chilled on his lips, and the wet, yellow curls blowing back from his white forehead that soon would grow yet whiter.

[11]Miss Glendower did not faint, neither did she scream; she was one with her emotions held always well in hand, and she expressed the proper amount of regret the occasion required—shuddering a little over its horror. But to this day (and she is Mrs. Lawrence Irving now) she cannot look quite steadily at a big, red star that sometimes burns in the West at early eve; and the scent of tuberoses, or jasmine, or syringa makes her deathly sick.

THERE was nothing pleasing in the scene. It was in that part of the vast West where a gray sky looked down upon the grayer soil beneath; where neither brilliant birds nor bright blossoms, nor glittering rivulets made lovely the place in which human beings went up and down the earth daily performing those labors that made the sum of what they called life. Neither tree nor shrub, nor spear of grass showed green with the healthy color of plant-life. As far as the eye could reach was the monotonous gray of sagebrush, and greasewood, and sand. The muddy river, with its myriad curves, ran between abrupt banks of soft alkali ground, where now and then as it ate into the confining walls, portions would fall with a loud splash into the water. A hurrying, treacherous river—with its many silent eddies—it turned and twisted and doubled on itself a thousand times as it wound its way down the valley. Here, where it circled in a great curve called “Scott’s Bend,” the waters were always being churned by the ponderous wheel of a little quartz-mill, painted by storm and sunshine in the leaden tones of its sad-colored surroundings.

On the bluff above, near the ore platform, were grouped a dozen houses. Fenceless, they faced the mill,[13] which day after day pounded away at the ore with a maddening monotony. All day, all night, the stamps kept up their ceaseless monotone. The weather-worn mill and drab adobe houses had stood there, year after year, through the heat of summer days, when the sun blistered and burned the whole valley, and in winter, when the winds of the desert moaned and wailed at the windows.

Today the air is quiet, save for the tiny whirlwinds that, running over the tailings below the mill, have caught up the fine powder and carried bits of it away with them, a white cloud, as they went. The sun, too, is shining painfully bright and burning. By the well a woman stands, her eyes intently following a chance wayfarer who has turned into the Sherman road—in all the waste, the only moving thing.

How surely human beings take on themselves the reflection of their surroundings! Living in the dull solitude of this valley that woman’s life has become but a gray reflection of its never-ending sameness. As we look, we fall a-wondering. Has she never known what it is to live in the way we understand it? Has nothing ever set her pulses tingling with the exultation of Life? Does she know only an existence which is but the compulsory working of a piece of human machinery? Has she never known what it is to feel hope, or joy, or love, in the way we feel it—never experienced one single stirring emotion in the whole round of her pitifully barren life? Is it possible that she has never realized the poverty of her existence?

Yet, she was a creature meant for Life. What a beautiful woman she is, too, with all that brilliance of coloring—that copper-hued hair, and those great, velvety eyes, lovely in spite of their apathetic stare. What a model for some painter’s brush! Such beauty and such[14] apathy combined; such expressionless perfection of feature; “faultily faultless, icily regular, splendidly null—dead perfection.”

Martha Scott is one of those women whose commanding figure and magnificent coloring are always sufficient to attract the admiration of even the most indifferent. No doubt now in her maturity she is far more beautiful than when, nearly twenty years ago, she became Old Scott’s wife. A tall, unformed girl then, she gave no promise of her later beauty, except in the velvety softness of the great eyes that never seemed to take heed of anything in the world about her, and the great mass of shining hair that had the red-gold of a Western sunset in it.

There had been a courtship so brief that they were still strangers when he took her to the small, untidy house where he had come to realize that the presence of a woman was needed. He wanted a wife to cook for him; to wash—to sew. And so they were married.

The sheep which numbered thousands, the little mill—always grinding in its jaws the ores brought down the mountain by the snail-paced teams to fill its hungry maw, these added daily to the hoard Old Scott clutched with gripping, penurious fingers. Early and late, unceasingly, he worked, and chose that Martha should labor as he labored, live as he lived. But, as she mechanically took up her burden of life, there came to the sweet, uncomplaining mouth a droop at the corners that grew with the years, telling to those who had the eyes to see, that while accepting with mute lips the unhappy conditions of her lot, she longed with all her starved soul for something different from her yearly round of never-ending toil.

Once—only once—in a whirlwind of revolt, she felt that she could endure it no longer—that she must break[15] away from the dull routine which made the measure of her days; felt that she must go out among happy human beings—to be in the rush and whirl of life under Pleasure’s sunshine—to bask in its warmth as others did. She longed to enjoy life as Youth enjoys; herself to be young once more. Yes, even to dance as she had danced when a girl! In the upheaval of her passionate revolt, flushed and trembling, she begged her husband to take her to one of the country balls of the neighborhood.

“Take me wunst!” she pleaded, her eyes glistening with unshed tears; “only this wunst; I won’t never ask you no more. But I do want to have one right good time. You never take me nowheres. Please take me, Fred, won’t you?”

Old Scott straightened himself from the task over which he was bending and looked at her in incredulous wonder. For more than a minute he stared at her; then, breaking into a loud laugh, he mocked:

“You’d look pretty, now, wouldn’t you, a-goin’ and a-toein’ it like you was a young gal!”

She shrank from him as though he had raised a lash over her, and the light died out of her face. Without a word she turned and went back to her work.

Martha Scott never again alluded to the meagre pleasures of her life. She went back to her work of cooking the coarse food which was their only fare; of mending the heavy, uncouth clothing which week-day and Sunday alike, was her husband’s only apparel; of washing and ironing the cheap calicoes, and coarse, unbleached muslins of her own poor, and scanty wardrobe, fulfilling her part as a bread-winner. The man never saw that he failed in performing the part of a[16] good and loving husband; and if anyone had pointed out to him that her existence was impoverished by his indifference and neglect, he still would have been unable to see wherein he had erred. He would have argued that she had enough to eat, enough to wear; that they owned their home—their neighbors having no better, nor any larger; he was laying aside money all the time; he did not drink; he never struck her. What more could any woman ask?

That the home which suited him, and the life to which he was used, could be other than all she desired, had never once occurred to him. As a boy, “back East” in the old days, he had never cared for the sports and pleasures enjoyed by other young people. How much less, now that the natural pleasure-time of life was past, could he tolerate pleasure-seeking in others!

“Folks show better sense to work an’ save their money,” he would say, “than to go gaddin’ about havin’ a good time an’ comin’ home broke.”

Together they lived in the house which through all their married life they had called “home;” together they worked side by side through all their years of youth and middle age. But not farther are we from the farthest star than were these two apart in their real lives. Yet she was his wife; this woman for whom he had no dearer name than “Marth’,” and to whom—for years—he had given no caress. She looked the incarnation of indifference and apathy. Ah! but was she?

A few years ago there came a mining expert from San Francisco to examine the Yellow Bird mine; and with him came a younger man, who appeared to have no particular business but to look around at the country, and to fish and hunt. There is the finest kind of[17] sport for the hunter over in the Smoky Range; and this fellow, Baird—Alfred Baird was his name—spent much of his time there shooting antelope and deer.

He was courteous and gentle mannered; he was finely educated—polished in address; he spoke three or four languages, and was good to look at. He stayed with the Scotts for a time—and a long time it proved to be; a self-invited guest, whether or no. Yet all the while he did not fail to reiterate his intentions to “handsomely remunerate them for their generous hospitality in a country where there were so few or no hotels.” He assured them he was “daily expecting a remittance from home. The delay was inexcusable—unless the mail had miscarried. Very annoying! So embarrassing!” And so on. It was the old stereotyped story which that sort of a fellow always carries on the tip of his tongue. And the wonder of it all was that Scott—surly and gruff to all others—was so completely under the scamp’s will, and ready to humor his slightest wish. Baird used without question his saddle and best horse; and it was Scott who fitted him out whenever he went hunting deer over in the Smokies.

By and by there came a time when Scott himself had to go away on a trip into the Smoky Range, and which would keep him from home a week. He left his wife behind, as was his custom. He also left Alfred Baird there—for Baird was still “boarding” at Scott’s.

When old Fred Scott came back, it was to find the house in as perfect order as ever, with every little detail of house work faithfully performed up to the last moment of her staying, but the wife was gone. Neither wife, nor the money—hidden away in an old powder-can behind the corner cupboard—were there.

Both were gone—the woman and the gold pieces; and it was characteristic of Old Scott that his first feelings[18] of grief and rage were not for the loss of his wife, but for the coins she had taken from the powder-can. He was like a maniac—breaking everything he had ever seen his wife use; tearing to pieces with his strong, sinewy hands every article of her clothing his eyes fell upon. He raved like a madman, and cursed like a fiend. Then he found her letter.

“Dear Fred:—

Now I’m a going away, and I’m a going to stay a year. The money will last us two just about that long. I asked Mr. Baird to go with me, so you needn’t blame him. I ain’t got nothing against you, only you wouldn’t never take me nowheres; and I just couldn’t stand it no longer. I’ve been a good wife, and worked hard, and earned money for you; but I ain’t never had none of it myself to spend. So I’m a going to have it now; for some of it is mine anyway. It has been work—work all the time, and you wouldn’t take me nowheres. So I’m a going now myself. I don’t like Mr. Baird better than I do you—that ain’t it—and if you want me to come back to you in a year I will. And I’ll be a good wife to you again, like I was before. Only you needn’t expect for me to say that I’ll be sorry because I done it, for I won’t be. I won’t never be sorry I done it; never, never! So, good-by.

Your loving wife,

Martha J. Scott.”

If, through the long years, he had not been blind, he could have saved her from it. Not a vicious woman—not a wantonly sinning woman; only one who—weak and ignorant—was dazed and bewildered by the possibilities she saw in just one year of unrestricted freedom to enjoy all the pleasures that might come within her reach.

To be sure, it did seem preposterous that a young[19] and handsome man, with refined tastes and education, should go away with a woman years older than himself, and one, too, who was uncouth in manner and in speech. However strange it looked to the world, the fact remained that they eloped. But both were well away before it was suspected that they had gone together. Old Scott volunteered no information to the curious; and his grim silence forbade the questions they would have asked. It was long before the truth was known, for people were slow to credit so strange a story.

The two were seen in San Francisco one day as they were buying their tickets on the eve of sailing for Honolulu. She looked very lovely, and was as tastefully and becomingly gowned as any woman one might see. Baird, no doubt, had seen to that; for he had exquisite taste, and he was too wise to challenge adverse criticism by letting her dress in the glaring colors and startling styles she would have chosen, had she been allowed to follow her own tastes. In her pretty, new clothes, with her really handsome face all aglow from sheer joy in the new life she was beginning, she looked twenty years younger, and attracted general attention because of her unusual eyes and her magnificently-colored hair.

She was radiant with happiness; and there was no apparent consciousness of wrong-doing. Baird always showed a gracious deference to all women, and to her he was devotion itself. The little attentions that will charm and captivate any woman—attentions to which she was so unused—fed her starved nature, and for the time satisfied without sating her. They sailed for the Islands, and were there a year. They kept to themselves, seeking no acquaintance with those around them—living but for one another. And those who saw them,[20] told they seemed thoroughly fond of each other. He was too much in love with himself and the surroundings which catered to his extravagant tastes, to have a great love for any woman; and she was scarcely the person, in spite of her beauty—the beauty of some magnificent animal—to inspire lasting affection in a man like Baird. He was shrewd enough to keep people at a distance, for unless one entered into conversation with her she might easily be taken for the really cultivated woman she looked. Yet the refined and aesthetic side of Alfred Baird’s nature—and there was such—much have met with some pretty severe shocks during a twelvemonth’s close companionship. Too indolent to work to support himself, he bore (he felt, heroically) any mortification he was subjected to, and was content in his degradation. But the woman herself was intensely happy; happier than, in all her dreary life, she had ever dreamed that mortals could be. She was in love with the beautiful new world, which was like a dream of fairy-land after her sordid life in the desolate valley. That Hawaiian year must have been a revelation of hitherto unimagined things to her. Baird’s moral sense was blunted by his past dissipations, but her moral sense was simply undeveloped. In her ignorance she had no definition of morality. The man was nothing to her except as an accessory to the fascinating life which she had allowed herself “while the money lasted.”

When the twelve months were run she philosophically admitted the end of it all, and parted with him—apparently—without a pang. If, at the moment of parting, any regrets were felt by either because of the separation, it was he, not she, who would have chosen to drift longer down the stream. The year had run its course; she would again take up the old[21] life. This could not last. Perhaps—who knows?—in time he might have palled on her. No doubt, in time, his weak nature would have wearied her; her own was too eager for strong emotions, to find in him a fitting mate.

Whether, at the last, she wrote to her husband, or if he came to her when the year came to its end, no one knows. But one day the people of the desert saw her back at the adobes on the bluff. She returned as suddenly as she had disappeared.

She seems to have settled into the old groove again. She moves in the same apathetic way as before the stirring events of her life. In her letter she said she would not be sorry. It is not probable that she ever was, or ever will be; but neither is it likely that she has ever seen the affair from the point of view a moralist would take. Her limited intelligence only allowed her to perceive the dreariness of her own poor life, and when her longings touched no responsive chord in the man whom she had married, she deliberately took one year of her existence and hung its walls with all the gorgeous tapestries and rich paintings that could be wrought by the witchery of those magic days in the Pacific.

Fires have burned as fiercely within that woman’s breast as ever burned the fires of Kilauea; and when they were ready to burst their bounds, she fled in her impulse to the coral isles of the peaceful Western sea, and there her ears heard the sound, and her heart learned the meaning of words that have left no visible sign upon her—the wondrous, sweet words of a dream, whispered to her unceasingly, while she[22] gave herself up to an enchantment as mad and bewildering as that of the rhythmic hula-hula.

If she sinned, she does not seem to know it. Going about at her work, as before, the expressionless face is a mask; yet it may be she is moving in a dream-world, wherein she lives over once again the months that were hers—once—in the far Hawaiian Isles.

SHE had been lying by the stone wall all day. And the sun was so hot that the blood beating in her ears sounded like the White Man’s fire-horse that had just pulled a freight train into the station, and was grunting and drinking down at the water tank a hundred yards away. It was getting all the water it wanted; why couldn’t she have all the water she wanted, too?

Today they had brought her the tomato can only half full. Such a little drink! And her mouth was so hot and dry! They were starving her to death—had been starving her for days and days. Oh, yes! she knew what they were doing. She knew why they were doing it, too. It was because she was in the way.

She was an old squaw. For weeks she had been half dead; she had lain for weeks whimpering and moaning in a corner of the camp on a heap of refuse and rotting rags, where they had first shoved her aside when she could no longer gather herself up on her withered limbs and go about to wait upon herself.

They had cursed her for her uselessness; and had let the children throw dirt at her, and take her scant share of food away and give it to the dogs. Then they had laughed at her when one of the older grandchildren had spat at her; and when she had striven[24] to strike at the mocking, devilish face, and in her feebleness had failed, they had but laughed the louder while she shrieked out in her hatred of them all.

Her children, and her children’s children—her flesh and bone! They were young, and well, and strong; and she was old, feeble and dying. Old—old—old! Too old to work. Too old to do for herself any longer, they were tired of her; and now they had put her out of the wick-i-up to die alone there by the stone wall. She knew it—knew the truth; but what could she do?

She was only an old Paiute squaw.

At first they had given her half the amount of food which they allowed her before she had grown so feeble. Then it was but a quarter; and then again it was divided in half. Now—at the last—they were bringing her only water.

One day when she was faint and almost crazed from hunger, one of the boys (her own son’s son) had come with a meat bone and thrown it down before her; but when she reached out with trembling, fleshless hands to grasp it, he had jerked at the string to which it was tied, and snatched it away. Again and again he threw it toward her; again and again she tried to be quick enough to close her fingers upon it before he could jerk it from her. Then (when, at last, he was tired of the play) he had flung it only an arm’s length beyond her reach, and had run laughing down to the railroad to beg nickels from the passengers on the train. When he had gone a dog came and dropped down beside her, and gnawed the bone where it lay. She had crawled out into the sunshine that day, and lay huddled in a heap close to the door-flap at the wick-i-up entrance. The warm sunlight at first felt good to her chilled blood, and she had lain there long;[25] but finally when she would have dragged her feeble body within again, a young squaw (the one who had mated with the firstborn son, and was now ruler of the camp) had thrust her back with her foot, and said that her whining and crying were making the Great Spirit angry; and that henceforth she must stay outside the camp, for a punishment.

Ah, she knew! She knew! They could not deceive her. It was not the Great Spirit that had put her out, but her own flesh and blood. How she hated them all! If she could only be young again she would have them put to death, as she herself had had others put to death when there were many to do her bidding. But she was old; and she must lie outside, away from those who had put her there to starve, while in the gray dusk they gathered around the campfire and ate, and laughed, and forgot her. She wished the cool, dark night might last longer, with the sage-scented winds from the plain blowing over her. But morning would come with a blood-red sun shining through the summer haze, and she would have to lie there under the furnace heat through all the long daylight hours, with only a few swallows of water brought to her in the tomato can to quench her intolerable thirst.

They were slowly starving her to death just because she was old. They hated squaws when they got old. They did not tell her so; but she knew. She, too, had hated them once. That was long ago. Long, long ago; when she was young, and strong, and swift.

She was straight then and good to look at. All of the young men of her tribe had striven for her; and two had fought long—had fought wildly and wickedly. That was when the White Man had first come into the country of her people, and they had fought with[26] knives they had taken from the Whites. Knives long, and shining, and sharp. They had fought and slashed, and cut each other till the hard ground was red and slippery where they stood. Then—still fighting—they had fallen down, down; and where they fell, they died. Died for her—a squaw! Well, what of it, now? Tomorrow she, too, would die. She whom they, and others, had loved.

Once, long ago—long before the time when she had become Wi-o-chee’s wife—at the Fort on the other side of the mountain, where the morning sun comes first, there had been a White Man whose eyes were the blue of the soldier-blue he wore; and whose mustache was yellow like the gold he wore on his shoulders.

He, too, was young, and straight, and strong; and one day he had caught her in his arms and held her while he kissed her on mouth and eyes, and under her little round chin. And when she had broken away from him and had run—run fast as the deer runs—he had called after her: “Josie! Josie! Come back!” But she had run the faster till, by and by, when he had ceased calling, she had stolen back and had thrown a handful of grass at him as he sat, with bowed head, on the doorstep of the officers’ quarters; his white fingers pressed tight over his eyelids. Then when he had looked up she had gone shyly to him, and put her hand in his. And when he stood up, looking eagerly in her eyes, she had thrown her head back, where she let it lay against his arm, and laughed, showing the snow-white line of her teeth, till he was dazzled by what he saw and hid the whiteness that gleamed between her lips by the gold that swept across his own.

That was long ago. Not yesterday, nor last week,[27] nor last month; but so long ago that it did not even awaken in her an interest in remembering how he had taught her English words to say to him, and laughed with her when she said them so badly.

She did not care about it, at all, now. She only wanted a drink of water; and her children would not give her what she craved.

Always, she had been brave. She had feared nothing—nothing. She could ride faster, run farther, dare more than other young squaws of the tribe. She had been stronger and suppler. Yet today she was dying here by the stone wall—put out of the camp by her children’s children to die.

She would die tomorrow; or next day, at latest. Perhaps tonight. She had thought she was to die last night when the lean coyote came and stood off from her, and watched with hungry eyes. All night he watched. Going away, and coming back. Coming and going all night. All night his little bright eyes shone like stars. And the stars, too, watched her there dying for water and meat, but they handed nothing down to her from the cool sky.

Oh, for strength again! For life, and to be young! But she was old and weak. She would die; and when she was dead they would take her in her rags, and—winding the shred of a gray blanket about her (the blanket on which she lay)—they would tie it tightly at her head and at her feet; and so she would be made ready for her last journey.

Dragging her to a waiting pony she would be laid across the saddle, face down. To the stirrups, which would be tied together beneath the horse that they might not swing, her head and feet would be fastened—her head at one stirrup, her feet at the other.

Then they would lead the pony off through the[28] greasewood. Along the stony trail across the upland to the foothills the little buckskin pony would pick his way, stumbling on the rocks while his burden would slip and shake about, lying across the saddle. Then they would lay her in a shallow place, and heaping earth and gravel over her, would come away. That was the way they had done with her mother, with Wi-o-chee, and the son who had died.

Tomorrow—yes, tomorrow—they would take her to the foothills. Perhaps the coyote would go there tomorrow night; would go there, and dig.

He had come now, and stood watching her from the shelter of the sagebrush. He was afraid to come nearer—now. She was too weak to move even a finger today, yet he was afraid. He would not come close till she was dead. He knew.

Once he walked a few steps toward her, watching her all the while with his little cruel eyes. Then he turned and trotted back into the sagebrush. He knew. Not yet.

All day the sun had lain in heavy heat on the tangle of vile rags by the stone wall. All day the magpie, hopping along the wall, watched with head bent sidewise at the rags that only moved with the faint breathing of the body beneath. All day long two buzzards far up in the still air swung slowly in great circling sweeps. All day, from early dawn till dusk, a brown hand—skinny and foully dirty—clutched the tomato can; but the can today had been left empty. Forgotten.

[29]When it grew dark and a big, bright star glowed in the West, the coyote came out of the shadows of the sagebrush and stood looking at the tangled rags by the stone wall.

Only a moment he stood there. He threw up his head, and his voice went out in a chilling call to his mate. Then with lifted lip he walked quickly forward. He was no longer afraid.

“YES, you’re right, Sid; in these days of multi-millionaires, nothing that is written with less than eight figures is considered ‘wealth.’ Yet, even so, I count this something more than a ‘tidy little sum’ you’ve cleaned up—even if you do not. And now tell me, what are you going to do with it?”

The man sitting at the uncovered pine table in the center of the room opened his lips to answer, checked himself as if doubtful of the reception of what he might say, and then went on nervously sorting and rearranging the handful of papers and letters which he held. However, the light that came into his eyes at Keith’s question, and the smile that played around his weak lips, showed without a doubt that the “tidy little sum” promised to him at least the fulfillment of unspoken dreams.

He was a handsome man of thirty—a man of feminine beauty rather than that which is masculine. And though dressed in rough corduroys and flannels, like his companion, they added to, rather than detracted from his picturesque charm. Slightly—almost delicately proportioned, he seemed to be taller than he really was. In spite of his great beauty, however, his face was not a satisfying one under the[31] scrutiny of a close observer, for it lacked character. There was refinement and a certain sweetness of temperament there, but the ensemble was essentially weak—it was the face of a man of whom one felt it would not be well for any believing, loving woman to pin her faith to.

Keith, sitting with his long legs crossed and his big, strong hands thrust deep into his trousers’ pockets, watched the younger man curiously, wondering what manner of woman she could have been who had chosen Sidney Williston for her lord and master.

“Poor little neglected woman,” thought Keith, with that tender and compassionate feeling he had for every feminine and helpless thing; “poor little patiently waiting wife! Will he ever go back to her, I wonder? I doubt it. And now to think of all this money!”

Williston had said but little to Keith about his wife. In fact, all reference to her very existence had been avoided when possible. Keith even doubted if his friend would ever again recognize the marriage tie between them unless the deserted one should unexpectedly present herself in person and claim her rights. Williston—vacillating, unstable—was the kind of a man in whom loyalty depends on the presence of its object as a continual reminder of obligations. Keith was sure, however, that the woman, whoever she might be, was more than deserving of pity.

“Sidney means well,” thought Keith trying to find excuse for him, “but he is weak—lamentably so—and sadly lacking in moral balance.” And never had Williston been so easily lead, so subservient to the will of another as now, since “that cursed Howard[32] woman” (as Keith called her under his breath) had got him into her toils.

Lovesick as any boy he was befooled to his heart’s content, wilfully blind to the fact that it was the old pitiful story of a woman’s greed, and that her white hands had caresses and her lips kisses for his gold—not for himself. Her arms were eager to hold in their clasp—not him, but—the great wealth which was his, the gold which had come from the fabulously rich strike he had cleaned up on the bedrock of the claim, where a cross reef had held it hidden a thousand years and more. Her red lips were athirst to lay kisses—— On his mouth? Nay! on the piles of minted gold that had lain in the bank vault since he had sold his mine. The Twentieth Century Aspasia has a hundred arts her sister of old knew naught of; and Williston was not the first man who has unwittingly played the part of proxy to another, or blissfully believed in the lying lips whose kisses sting like the sting of wild bees—those honey-sweet kisses that stab one’s soul with needles of passionate pain. All these were for the gold-god, not him; he was but the unconscious proxy.

Keith mused on the situation as he sat in the flickering candle-light blown by the night wind that—coming in through the open window—brought with it the pungent odor of sagebrush-covered hills.

“Strange,” he thought, “how a woman of that particular stamp gets a hold on some fellows! And with a whole world full of other women, too—sweet, good women who are ready to give a man the right sort of love and allegiance, if he’s a half-way decent sort of a fellow with anything at all worthy to give in exchange; God bless ’em!—and confound him! He[33] makes me angry; why can’t he pull himself together and be a man!”

Bayard Keith was no saint. Far from it. Yet, for all his drifting about the world, he had kept a pretty clean and wholesome moral tone. Women of the Gloria Howard class did not appeal to his taste; that was all there was about it. But he knew men a-plenty who, for her sake, would have committed almost any crime in the calendar if she set it for them to do. There were men who would have faced the decree of judge and jury without a tremor, if the deed was done for her sake. He himself could not understand such things. Not that he felt himself better or stronger than his fellows; it was simply that he was made of a different sort of stuff.

Yet, in spite of his manifest indifference to the charm of her large, splendid beauty—dazzling as the sun at noon-day—and that marked personality which all others who ever came within the circle of her presence seemed to feel, Keith knew he could have this woman’s love for the asking—the love of a woman who, ’twas said, won love from all, yet giving love to none. Nay, but he knew it was already his. His very indifference had fanned a flame in her breast; a flame which had been lit as her eyes were first lifted to his own and she beheld her master, and burning steadily it had become the consuming passion of this strange creature’s existence. Hopeless, she knew it was; yet it was stronger than her love of life. Even stronger than her inordinate love of money was this passion for the man whose heart she had utterly failed to touch.

That he must know it to be so, was but an added pain for her fierce nature to bear. Keith wondered if Williston had ever suspected, as she played her[34] part, the woman’s passionate and genuine attachment to himself. He hoped not, for the two men had been good comrades, though without the closer bond of a fine sympathy; and Keith’s wish was that their comradeship should continue, while he hoped the woman’s love, in time, would wear itself out. To Williston he had once tried to give a word of advice.

“Drop it, Keith,” came the quick answer to his warning, “I love her.”

“Granted that you do, why should you so completely enslave yourself to a woman of that type?”

“What do you mean by ‘that type?’ Take care! take care, Keith! I tell you I love her! Were I not already a married man I would make Mrs. Howard my wife.”

“Oh, no, you wouldn’t,” Keith answered quietly. “Howard refuses to get a divorce, and you know very well she cannot. Besides, Sid, it would be sheer madness for you to do such a thing, even were she free.”

“It makes no difference; I love her,” was again the reply, and said with the childish persistence of those with whom reiteration takes the place of argument.

Keith said no more, though he felt the shame of it that Sidney Williston’s fortune should be squandered on another woman, while—somewhere off there in the East—his wife waited for him to send for her. Keith’s shoulders shrugged with impatience over the whole pitiful affair. He was disgusted at Williston’s lack of principle and angered by his disregard of public censure. However, he reflected, trying to banish all thoughts of it, it was none of his business; he was not elected to be his brother’s keeper in this affair surely.

[35]As for himself, he believed the only love worth having was that upon which the foundation of the hearthstone was laid. He believed, too, that to no man do the gods bring this priceless treasure more than once. When a man like Keith believes this, it becomes his religion.

Through the gateway to his big, honest heart, one summer in the years gone by, love had entered, and—finding it the dwelling of honor and truth—it abided there still.

Thinking of Williston’s infatuation for Gloria Howard, he could but compare it to his own entire, endless love for Kathryn Verrill. He recalled a day that would always stand out in bold relief from all others in memory’s gallery.

In fancy now he could see the wide veranda built around one of the loveliest summer homes of the beautiful Thousand Islands. Cushions—soft and silken—lay tossed about on easy chairs and divans that were scattered about here and there among tubs of palms and potted plants. On little tables up and down the veranda’s length were summer novels open and face downward as their readers had left them, or dainty and neglected bits of fancy-work. Cooling drinks and dishes of luscious fruits had been placed there within their reach. Keith closed his eyes with a sigh, as the memory of it all came back to him. Here, amid the sage and desert sands, it was like a dream of lost Paradise.

It had been a day of opalescent lights, and through its translucence they (he and—she) could see the rest of the party on the sparkling waters, among the pleasure craft from other wooded islands, full of charm, near by. Only these two—he and she—were here on the broad veranda. The echo of distant laughter[36] came to them, but here was a languorous silence. Even the yellow-feathered warblers in the gilded cages above them had, for the time, hushed their songs.

Kathryn Verrill was swinging slowly back and forth in one of the hammocks swung along the veranda, the sunlight filtering through the slats of the lowered blinds streaking with gold her filmy draperies as they swept backward and forward on the polished floor. Her fingers had ceased their play on the mandolin strings, and there was now no sound about them louder than the hum of the big and gorgeous bumble-bee buzzing above their heads. Summer sweetness anywhere, and she the sweetest of it all! Then——

Ah, well! He had asked her to marry him, and the pained look that came into her face was his answer even before he heard her say that for two years she had been another’s—a secretly-wedded wife. Why she should now tell her carefully guarded secret to him she herself could hardly have told. No one else knew. Her husband had asked that it should be their dear secret until he could send for her to come to him out in the land of the setting sun, where he had gone alone in the hope that he would find enough of the yellow metal grains so that he could provide her with a fitting home. Her guardian had not liked the man of her choice—had made objections to his attentions. Then there was the clandestine marriage. And then he had gone away to make a home for her. But she loved him; oh, yes! he was her choice of all the world, her hero always—her husband now. She was glad to have done as she did—there was nothing to regret, except the enforced separation. So she was keeping their secret while feeding her soul with the hope of reunion that his[37] rare letters brought. But she had faith. Some day—some day he would win the fortune that would pave the way to him; then he would send for her. Some day. And she was waiting. And she loved him; loved him. That was all.

All, except that she was sorry for Keith, as all good women are sorry to hurt any human creature. No loyal, earnest, loving man ever offers his whole heart to any true and womanly woman (it matters not how little her own affections are moved by his appeal, or if they be stirred at all) that she does not feel touched and honored by the proffered gift. Womanly sympathy looked out of her gentle eyes, but she had for him no slightest feeling of other attraction. Keith gravely accepted his fate; but he knew that Love (that beautiful child born of Friendship—begot by Passion) would live forever in the inner chamber of his heart. To him, Kathryn Verrill would always be the one woman in all the world.

He went out of her life and back to the business routine of his own. In work he would try to forget his wounds. Later there were investments that turned out badly, and he lost heavily—lost all.

Then he came West. Here, in the Nevada mountains, he had found companionship in Sidney Williston who, like himself, was a seeker for gold. A general similarity of tastes brought about by their former ways of living (for Williston, too, was an eastern man) had been the one reason for each choosing the companionship of the other. So, here in the paintless pine cabin in Porcupine Gulch, each working his separate claim, they had been living under the same roof for nearly two years; but Fate, that sees fit to play us strange tricks sometimes, had laid a fortune in Williston’s hands, while Keith’s were yet empty.

[38]Sidney Williston’s silence, when asked what he would do with his wealth, was answer enough. It would be for Gloria Howard. There he sat now, thinking of her—planning for her.

Millers, red-winged moths and flying ants fluttered around the candle, blindly batting at the burning wick and falling with singed wings on the table. The wind was rising again, and the blaze at times was nearly snuffed out, moth-beaten and blown by the strong breeze.

All the morning the sun had laid its hot hand heavily on the earth between the places where dense white clouds hung without a motion in the breathless sky. The clouds had spread great dark shadows on the cliffs below, where they clung to the rocks like time-blackened and century-old lichens. But in the shadowless spots the sun’s rays were intensely hot, as they so often are before a coming storm; while the fierce heat for the time prostrated plant-life, and sent the many tiny animals of the hills to those places where the darkest shadows lay. Flowers were wilting where they grew. White primroses growing in the sandy soil near the cabin had but the night before lifted their pale, sweet faces to the moon’s soft light—lovely evening primroses growing straight and strong. Noonday saw them drooping weakly on their stalks, blushing a rosy, shamed pink; kissed into color by the amorous caresses of that rough lover, the Sun. Night would find them faded and unlovely, their purity and sweetness ruthlessly wrested from them forever.

As the sun climbed to the zenith, there was not the slightest wind stirring; the terrible heat lay, fold on fold, upon the palpitating earth. But noon came and brought a breeze from out of the south. Stronger and stronger it swept toward the blue mountains[39] lying away to the northward. It gathered up sand particles and dust, and shook them out into the air till the sunlight was dulled, and the great valley below showed through a mist of gold. All the afternoon the atmosphere was oppressively hot, while the wind hurried over valley and upland and mountain. All the afternoon the dust storm in billowy clouds hurried on, blowing—blowing—blowing. A whistling wind it was, keeping up its mournful song in the cracks of the unpainted cabin, and whipping the burlap awning over the door into ragged shreds at the edges. The dark green window shades flapped and rattled their length, carried out level from their fastenings by the force of the hot in-blowing wind.

Then with the down-going of the sun the wind died down also. When twilight came, the heavens were overcast with rain-clouds that told of a hastening storm which would leave the world fresh and cool when it had passed. The horizon line was brightened now and again by zigzags of lightning. Inside the cabin the close air was full of dust particles.

Sidney Williston tossed a photograph across the table, as he gathered his papers together preparatory to putting them away.

“There’s my wife’s picture, Keith,” he said; “I don’t think I ever showed it to you, did I?”

Keith got up—six feet, and more, of magnificent manhood; tall, he was, and straight as a pine, and holding his head in kingly wise. Leisurely he walked across the bare floor, which echoed loudly to his tread; leisurely he picked it up.

It was the pictured face of Kathryn Verrill!

He did not say anything; neither did he move.... If you come to think of it, those who sustain[40] great shocks seldom do anything unusual except in novels. In real life people cry out and exclaim over trifles; but let a really stupendous thing happen, and you may be very sure that they will be proportionately silent. The mind, incapable of instantly grasping the magnitude of what has happened, makes one to stand immovable and in silence.

Keith said nothing. His breathing was quite as regular as usual, and his grasp on the picture was firm—untrembling. Yet in that instant of time he had received the greatest shock of his life, and myriad thoughts were running through his brain with the swiftness of the waters in the mining sluice. He held the bit of pasteboard so long that Williston at last looked up at him inquiringly.

When he handed it back his mind was made up. He knew what must be done. He knew what he must do—at once—for her sake.

When two or three hours later he heard Williston’s regular breathing coming from the bed across the room, he stole out in the darkness to the shed where the horses and buckboard were. It was their one vehicle of any sort, and the only means they had of reaching the valley. With the team gone, Williston would practically be a prisoner for several days. Keith had no hesitation in deciding which way his duty lay. It was thirty miles to the nearest town; to the telegraph; to Gloria Howard; to the railroad!

As he pulled the buckboard out of the shed and put the horses before it, the first raindrops began to fall. Big splashing drops they were, puncturing the parched dust as they beat down upon it. Flashes of lightning split the heavens, and each flash made the earth—for the instant—noon-bright. When he had buckled the last strap his hands tightened on the[41] reins, and he swung himself up to the seat as the thunder’s batteries were turned loose on the earth in a tremendous volley that set the very ground trembling. The frightened horses, crouching, swerved aside an instant, and then leaped forward into the darkness. Along the winding road they swept, like part of the wild storm, toward the town that lay off in the darkness of the valley below.

It was past midnight, and thirty miles lay between him and the railroad. There was no time to spare. He drove the horses at a pace which kept time with his whirlwind thoughts and his pulses.

He had been cool and his thoughts had been collected when under another’s possible scrutiny. Now, alone, with the midnight storm about him, his brain was whirling, and a like storm was coursing through his veins.

The crashing thunder that had seemed like an avalanche of boulders shattered and flung earthward by the fury of the storm, began to spend itself, and close following on the peals and flashes came the earth-scent of rain-wetted dust as the big drops came down. By and by the thunder died away in distant grumbling, and the fiery zigzags went out. There was the sound of splashing hoofs pounding along the road; and the warm, wet smell of horses’ steaming hides, blown back by the night wind.

Fifteen miles—ten—five miles yet to go. Not once had Keith slackened speed.

When at length he found himself on the low levels bordering the river, the storm had passed over, and ere he reached the town the rain had ceased falling. A dim light was breaking through the darkness in places, and scudding clouds left rifts between which brilliant stars were beginning to shine.

[42]As he drove across the bridge and into the lower town, he woke the echoes of a watch-dog’s barking; otherwise, the town was still. At the livery stable he roused the sleeping boy, who took his team; and flinging aside the water-soaked great-coat he wore, he walked rapidly toward the railroad station at the upper end of the town. The message he wrote was given to the telegraph operator with orders to “rush.” It read:

“I have found the fortune. Now I want my wife. Come.”

He signed it with Sidney Williston’s name.

“Is Number Two on time?” he asked.

“An hour late. It’ll be here about 4:10,” was the reply.

Leaving the office, he went back to the lower town. Down the hill and past the pleasant cottages half hidden under their thick poplar shade, and surrounded by neat, close-trimmed lawns. Leaf and grass-blade had been freshened by the summer storm; and the odor of sweet garden flowers—verbenas, mignonette and pinks—was wafted strongly to his nostrils on the night air. They were homes. He turned away from all the fragrance and sighed—the sigh of renunciation. Crickets were beginning to trill their night songs. Past the court-house he went, where it stood ghostly and still in the darkness; past the business buildings farther down, glistening with wet. He turned into a side street to the house where he had been told Gloria Howard lived. At the gate he hesitated a moment, then opening it, went inside. Stepping off the graveled walk, his feet pressed noiselessly into the rain-soaked turf as he turned a corner of the cottage, and—going to a side window—rapped on the casing.

[43]There was silence, absolute and deep. Again he rapped. Sharply this time; and he softly called her name twice. He heard a startled movement in the room, then a pause, as though she were listening. A moment later her white gown gleamed against the darkness of the bedchamber, and she stood at the open window under its thick awning of green hop vines. Her face was on a level with his own. Her hair exhaled the odor of violets. He could hear her breathing.

“Gloria,”——he began, softly.

“Who are you——what is it?” Then, “Keith! You!” she exclaimed; and in a moment more flung wide the wire screen that had divided them.

“Sh!”——he whispered. “I want to speak to you. But——hark! listen!” He laid his hand lightly on her lips.

She caught it quickly between both her own, and laid a hot cheek against it for an instant; then she pressed it tightly against her heart.

The night watchman patrolling the streets was passing; and they stood—he and she together—without movement, in the moist, dusky warmth of the rain-washed summer night, until the footsteps echoed faintly on the wet boards half a block away; the sound mingling with the croaking of the river frogs. Keith could feel the fast beating of her heart. The wet hop leaves shook down a shower of drops as they were touched by a passing breeze.

“Gloria,”——he spoke rapidly, but scarcely above his breath——“I am going away tonight——(he felt her start) away from this part of the country forever; and I have come to ask you to go with me. Will you? Tell me, Gloria, will you go?”

[44]She did not reply, but laying a hand on his still damp coat-sleeve, tried to draw him closer, leaning her face towards his, and striving to read in his own face the truth of his words.

Had there been light enough for him to see, he would have marvelled at the varying expressions that followed in quick succession across her face. Surprise, incredulity, wonderment, a dawning of the real meaning of his words, triumph as she heard, and then—finally—a look of fierce, absorbing, tigerish love. For whatever else there might be to her discredit, her love for him was no lie in her life. She had for this man a passion as strong as her nature was intense.

“Gloria, Gloria, tell me! Will you leave all—everything and everybody—and go away with me?” he demanded impatiently. “Number Two is late—an hour late tonight, and you will have time to make yourself ready if you hasten. Come, Gloria, come!”

“Do——you——mean——it, Bayard Keith?” she breathed.

“I mean it. Yes.”

She knew his yea was yea; still she missed a certain quality in what he said—a certain something (she could not say what) in his tone.

She inhaled a long breath as she drew away from him.

“You are a strange man—a very, very strange man. Do you know it? All these many months you have shunned me; yet now you ask me to cast my lot with yours. Why?”

“Because I find I want you—at last.”

His answer seemed to satisfy her.

“For how long?” she asked.

Just for the imperceptible part of a second he hesitated.[45] His answer would be another unbreakable link in the chain he was forging for himself. Only the fraction of a second, though, he paused. Then his reply came, firm and decided:

“Forever, Gloria, if you will have it so.”

For answer she dropped her head on her folded arms while a dry, hard sob forced its way through her lips. It struck upon the chord within him that always thrilled to the sight or sound of anything, even remotely, touching grief. This sudden, unexpected joy of hers was so near akin to sorrow—ay, and she had had much sorrow, God knows! in her misspent life—it was cause enough for calling forth the gentle touch he laid upon her bowed head.

“Don’t, Gloria, girl! Don’t! It isn’t worth this, believe me. Yet, if you come, you shall never have cause for regret, if there’s anything left in a man’s honor.”

He stroked her hair silently a moment before he said:

“There are some things yet to be done before train time; so I must go now. Will you be there—at the station?”

“Yes.”

So it was that the thing was settled; and Keith accepted his fate in silence.

An evil thing done? Perhaps. Evil, that good might come of it. And he himself to be the sole sufferer. He was removing this woman beyond Sidney Williston’s reach forever. When the weak, erring husband should find himself free once more from the toils which had held him, his love (if love it was) would return to the neglected wife; and she, dear, faithful, loving woman that she was, would never, thank heaven! guess his unfaithfulness.

Bayard Keith did not feel himself to be a hero.[46] Such men as he are never vainglorious; and Keith had no thought of questioning Life’s way of spelling “duty” as he saw it written. He was being loyal for the sake of loyalty, a sacrifice for love’s own sake than which no man can make greater, for he knew that his martyrdom would be in forever being misjudged by the woman for whose dear sake it was done. He would be misjudged, of course, by Sidney Williston, and by all the world, for that matter; but for them he did not care. He was simply doing what he thought was right that he himself should do—for Kathryn Verrill’s sake. Her love had been denied him. Now he must even forfeit her respect. All for love’s sake. None must ever know why he had done this hideous thing. They must be made to think that he—like others—had yielded to a mad love for the bad, beautiful woman. In his very silence under condemnation lay security for Kathryn Verrill’s happiness. Only he himself would ever know how great would be his agony in bearing the load he had undertaken. Oh, if there might be some other way than this! If there could be but some still unthought-of means of escape whereby he could serve his dear lady, and yet be freed from yoking his life with a woman from whom his whole being would revolt. How would he be able through all the years to come—years upon years—to bear his life, with her?

As he walked past the darkened buildings he breathed heavily, each breath indrawn with a sibilant sound, like a badger at bay. Yet he had no thought of turning aside from his self-imposed immolation.

No one was astir in the lower town, save himself and the night watchman. Now and then he passed a dim light burning—here a low-turned burner in store or bank building; there the brighter glow of lamps[47] behind the ground glass of some saloon door. Halfway up the long street leading to the upper town he heard the rumble of an incoming train. Was Number Two on time, after all? Was a pitying Fate taking matters away from him, and into its own hands? Was escape being offered him?

If he hurried—if he ran—he could reach the station in time, but—alone! There would be no time to go back for Gloria Howard. He almost yielded for a moment to the coward’s impulse to shrink from responsibility, but the thought of Kathryn Verrill, waiting by the eastern sea for a message to come from the man she loved, roused him to his better self. He resolutely slackened his pace till the minutes had gone by wherein he could have become a deserter; then he went on up to the station.

“No, that was a freight train that just pulled out,” said the telegraph operator. “Number Two will be here pretty soon, though. Less’n half an hour. She’s made up a little time now.”

Keith went to the office counter and began to write. It was not a long letter, but it told all there was to say:

“Sid: I have wired to your wife to come to you, and I have signed your name. By the time this reaches you she will be on her way here. It will be wiser, of course, for you to assume the sending of the message, and to give her the welcome she will expect. It will be wiser, too—if I may offer suggestions—to travel about with her for a while; to go away from this place, where she certainly would hear of your unfaithfulness should she remain. Then go back with her to your friends, and live out the balance of your life, in the old home, as you ought. I know you will feel I am not a fit one to preach, for I myself am[48] going away tonight, taking Gloria Howard with me. I know, too, how you will look at what I am doing; but I have neither excuses nor explanations to offer.

Bayard Keith.”

That was all.

When he had sealed and directed it, he went to the livery stable and waked up Pete Dudley.

“See here, Pete,” he said, “I want you to do something for me.”

“Sure, Mr. Keith!” said Pete, rubbing his eyes.

“Here’s a letter for Mr. Williston out at our camp in Porcupine Gulch. I want you to take it to him, and take the buckboard, too.”

“All right, I’ll go in the morning.”

“No, no! Listen! Not till day after tomorrow. Wait, let me think—— You’d better wait a day longer——go the next day. Do you understand?”

“I guess I savvy. Not till Friday. Take the letter and the buckboard. Is that the racket?”

“Yes, that’s what I want, Pete. Here! Take them to him without fail on Friday. Good-night, Pete. Good bye!”

Keith walked back to the station and went in the waiting-room, where he sat down. His heart felt as heavy as lead. He had burned all his bridges behind him, and it made his soul sick to contemplate the long vista of the coming years.

As he sat there, the coward hope that she—Gloria—might not come, shot up in his heart, trying to make of him a traitor. He said to himself: “If——if——” Presently he heard the train whistle. He got up and went to the door. He felt he was choking. Daylight was coming fast; day-dawn in the eastern sky. The town, rain-cleansed and freshened, would soon awake and lift its face to the greeting of another morn.

[49]The ticket-office window was shoved up. It was nearing train time.

“Hello, Mr. Keith, going away?”

“Yes, I want a——” he hesitated.

“Where to?”

But Keith did not answer. A ticket? One, or two? If she should not come—— Was Fate——? What was he to do? But, no! Yet he hesitated, while the man at the window waited his reply. Two tickets, or only one? Or not any? Nay, but he must go; and there must be two.

Then the train thundered into the station, and almost at the same moment he heard, through the sound made by the clanging bell, the rustle of a woman’s rich garments. He turned. Gloria Howard stood there, beautiful and eager, panting from her hurried walk.

“Where to?” repeated the man at the window.

“San Francisco—two tickets,” said Keith.

“‘Two,’ did you say?” asked the man, looking up quickly at him and then glancing sideways at the radiant, laughing woman who had taken her place so confidently at Keith’s side.

Keith’s voice did not falter, nor did his eyes fall:

“Two.”

But the telegraph operator smiled to himself as he shoved the tickets across the window sill. To him, Keith was simply “Another one!” So, too, would the world judge him after he was gone.

Bayard Keith was no saint; but as he crossed to the cars in the waxing light of day-dawn, his countenance[50] was transfigured by an indescribable look we do not expect to see—ever—on the face of mortal man.

“For her dear sake!” he whispered softly to himself, as he looked away to the reddening East—to the eastward where “she” was. “For the sake of the woman I love.”

And “greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

IT all happened years ago. Before there was any railroad; even before there were any overland stages crossing the plains. Only the emigrant teams winding slowly down the valley on the road stretching westward.

Some there were, though, that had worked their way back from the Western sea, to stop at those Nevada cañons where there was silver to be had for the delving.

The cañons were beautiful with dashing, dancing streams, and blossoming shrubbery, and thick-leafed trees; and there grew up in the midst of these, tiny towns that called themselves “cities,” where the miners lived who came in with the return tide from the West.

There in one of the busiest, prettiest mining camps on a great mountain’s side, in one of the stone cabins set at the left of the single long street, dwelt Tony and his cousin Bruno—Italians, both. Bruno worked in the mines; but Tony, owning an ox team, hauled loads for the miners to and from the other settlements. A dangerous calling it was in those days, because an Indian in ambush had ever to be watched for when a White Man came down from the cañons to travel alone through the valley.