Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

ANNE WARWICK

BOOKS BY ANNE WARWICK

COMPENSATION

$1.30 net

THE UNKNOWN WOMAN

$1.30 net

JOHN LANE COMPANY

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Underwood & Underwood

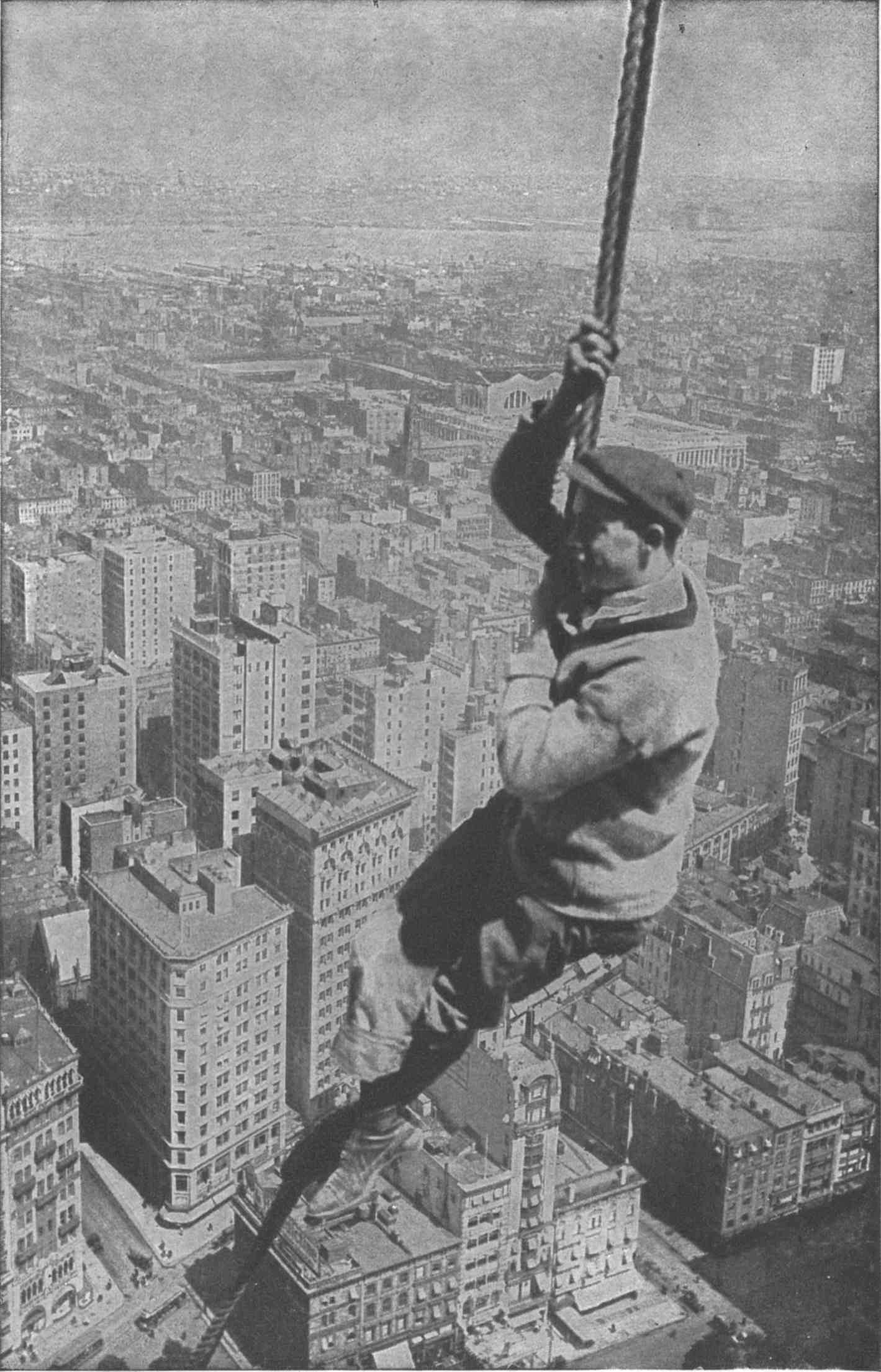

AN AMERICAN ALLEGORY: FIVE HUNDRED FEET ABOVE HIS SKYSCRAPER, AND STILL CLIMBING!

THE MECCAS OF

THE WORLD

THE PLAY OF MODERN LIFE IN

NEW YORK, PARIS, VIENNA,

MADRID AND LONDON

BY

ANNE WARWICK

AUTHOR OF “THE UNKNOWN WOMAN,” “COMPENSATION,” ETC.

NEW YORK

JOHN LANE COMPANY

MCMXIII

Copyright, 1913, by

JOHN LANE COMPANY

TO

MY FATHER

| PART I | ||

| IN REHEARSAL | ||

| (New York) | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Cast | 3 |

| II. | Convenience vs. Culture | 16 |

| III. | Off Duty | 30 |

| IV. | Miss New York, Jr. | 44 |

| V. | Matrimony & Co. | 59 |

| PART II | ||

| THE CURTAIN RISES | ||

| (Paris) | ||

| I. | On the Great Artiste | 77 |

| II. | On Her Everyday Performance | 90 |

| III. | And Its Sequel | 107 |

| PART III | ||

| THE CHILDREN’S PERFORMANCE | ||

| (Vienna) | ||

| I. | The Playhouse | 127 |

| II. | The Players Who Never Grow Old | 139 |

| III. | The Fairy Play | 153 |

| PART IV | ||

| THE BROKEN-DOWN ACTOR | ||

| (Madrid) | ||

| I. | His Corner Apart | 173 |

| II. | His Arts and Amusements | 187 |

| III. | One of His Big Scenes | 205 |

| IV. | His Foibles and Finenesses | 215 |

| PART V | ||

| IN REVIEW | ||

| (London) | ||

| I. | The Critics | 235 |

| II. | The Judgment | 248 |

| An American Allegory | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Afternoon Parade on Fifth Avenue | 10 |

| A Patch of the Crazy Quilt | 14 |

| “New York’s Finest.” | 30 |

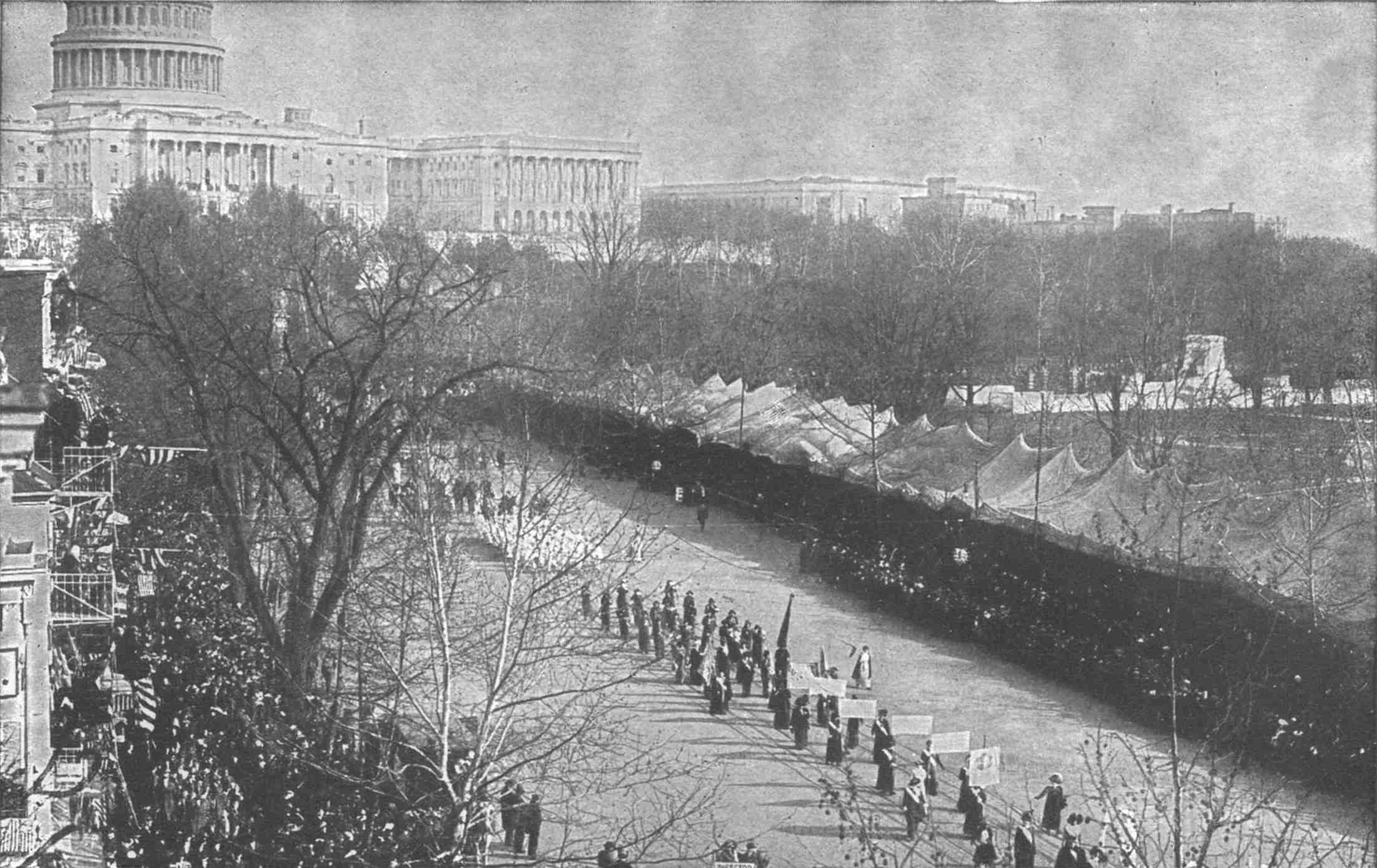

| American Woman Goes to War | 58 |

| The Triumphant “Third Sex” Takes Washington | 66 |

| Open-Air Ball on the 14th July | 82 |

| L’Heure du Rendez-vous | 110 |

| The Soul of Old Spain | 173 |

| The Queen of Spain and Prince of Asturias | 184 |

| Fair Enthusiasts at the Bull-Fight | 190 |

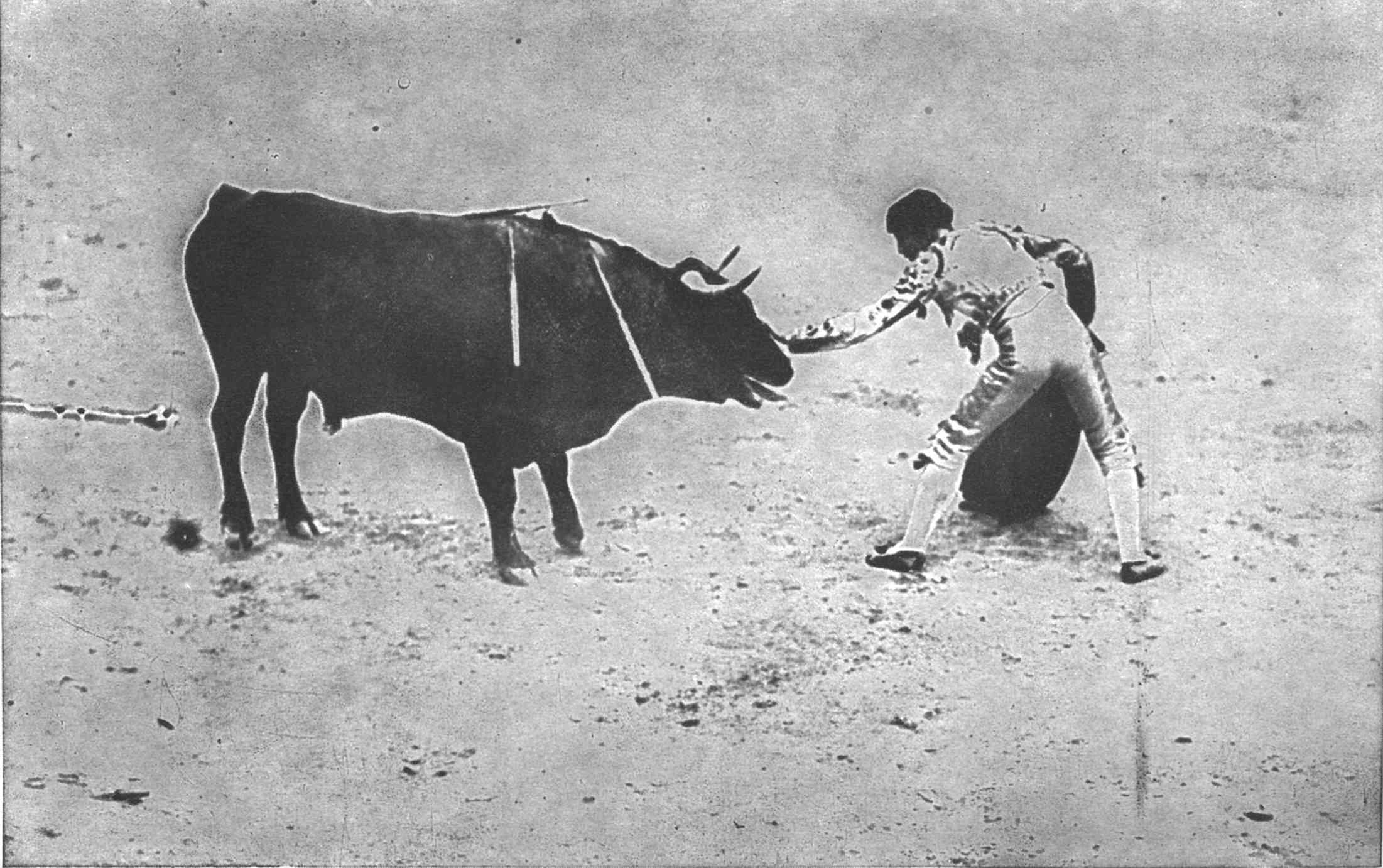

| The Supreme Moment | 192 |

| A Typical Posture of the Spanish Dance | 204 |

| The Royal Family of Spain after a Chapel Service | 210 |

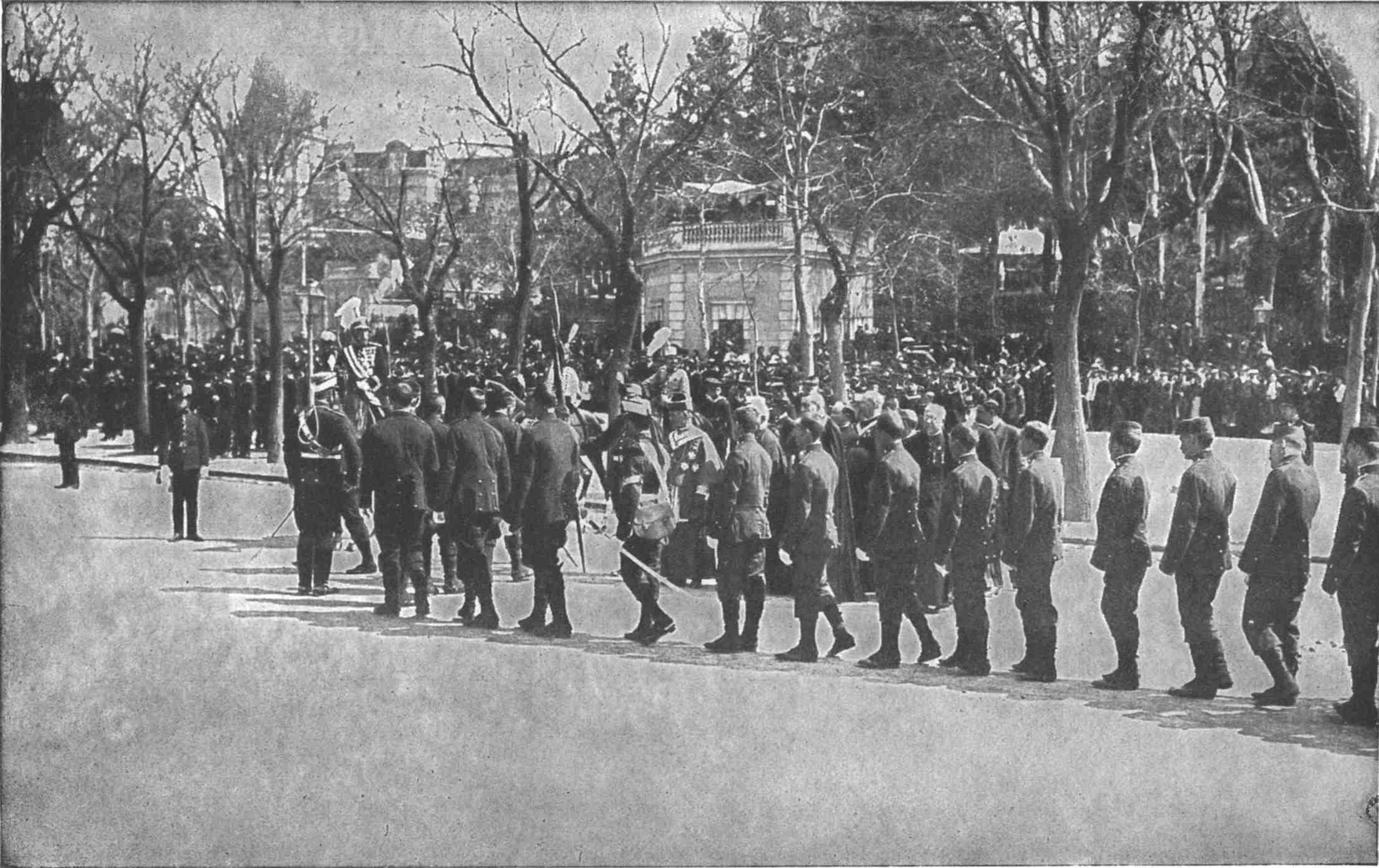

| King Alfonso Swearing-in Recruits, April 13, 1913 | 212 |

| “The Restful Sweep of Parks” | 235 |

| London: The Empire Capital | 252 |

| The Great Island Site | 256 |

| Linking the New Era and the Old | 258 |

A play is a play in so much as it furnishes a fragment of actual life. Being only a fragment, and thus literally torn out of the mass of life, it is bound to be sketchy; to a certain extent even superficial. Particularly is this the case where the scene shifts between five places radically different in elements and ideals. The author can only present the (to her) most impressive aspects of the several pictures, trusting to her sincerity to bridge the gaps her enforced brevity must create. And first she invites you to look at the piece in rehearsal.

3

Thanks to the promoters of opéra bouffe we are accustomed as a universe to screw our eye to a single peep-hole in the curtain that conceals a nation, and innocently to accept what we see therefrom as typical of the entire people. Thus England is generally supposed to be inhabited by a blond youth with a top-hat on the back of his head, and a large boutonnière overwhelming his morning-coat. He carries a loud stick, and says “Ah,” and is invariably strolling along Piccadilly. In France, the youth has grown into a bad, bold man of thirty—a boulevardier, of course—whose features consist of a pair of inky moustaches and a wicked leer. He sits at a table and drinks absinthe, and watches the world go by. The world is never by chance engaged elsewhere; it obligingly continues to go by.

Spain has a rose over her ear, and listens with patience to a perpetual guitar; Austria forever is waltzing upstairs, while America is known to be populated by a sandy-haired person of no definite age or embellishments, who spends his time in the alternate amusements of tripling his fortune and ejaculating “I guess!” He has a white marble mansion4 on Fifth Avenue, and an office in Wall Street, where daily he corners cotton or sugar or crude oil—as the fancy strikes him. And he is bounded on every side by sky-scrapers.

Like most widely accepted notions, this is picturesque but untrue. The Americans of America, or at least the New Yorkers of New York, are not the handful of men cutting off coupons in mahogany offices “down-town”; nor the silken, sacheted women gliding in and out of limousines, with gold purses. They are the swarm of shop-keepers and “specialists,” mechanics and small retailers, newspaper reporters and petty clerks, such as flood the Subways and Elevated railways of New York morning and night; fighting like savages for a seat. They are the army of tailors’ and shirt-makers’ and milliners’ girls who daily pour through the cross-streets, to and from their sordid work; they are the palely determined hordes who batter at the artistic door of the city, and live on nothing a week. They are the vast troops of creatures born under a dozen different flags, whom the city has seduced with her golden wand, whom she has prostituted to her own greed, whom she will shortly fling away as worthless scrap—and who love her with a passion that is the root and fibre of their souls.

So much for the actual New Yorkers, as contrasted with the gilded nonentity of musical comedy and best-selling fiction. As for New York itself, it has the appearance of behind the scenes at a gigantic theatre. Coming into the harbour is like entering the house5 of a great lady by the back door. Jagged rows of match-like buildings present their blank rear walls to the river, or form lurid bills of advertisement for somebody’s pork and beans; huge barns of ferry terminuses overlap with their galleries the narrow streets beneath; slim towers shoot up, giddy and dazzling-white, in the midst of grimy tenements and a hideous black network of elevated railways; the domes of churches and of pickle factories, the turrets of prisons and of terra cotta hotels, the electric signs of theatres and of cemetery companies, are mingled indiscriminately in a vast, hurled-together heap. While everywhere great piles of stone and steel are dizzily jutting skyward, ragged and unfinished.

It is plain to be seen that here life is in preparation—a piece in rehearsal; with the scene-shifters a bit scarce, or untutored in their business. One has the uncomfortable sensation of having been in too great haste to call; and so caught the haughty city on her moving-in day. This breeds humility in the visitor, and indulgence for the poor lady who is doing her best to set her house to rights. It is a splendid house, and a distinctly clever lady; and certainly in time they will adjust themselves to one another and to the world outside. For the present they loftily enjoy a gorgeous chaos.

Into this the stranger is landed summarily, and with no pause of railway journey before he attacks the city. London, Paris, Madrid, may discreetly withdraw a hundred miles or more further from the6 impatient foreigner: New York confronts him brusquely on the pier. And from his peaceful cabin he is plunged into a vortex of hysterical reunions, rushing porters, lordly customs officials, newspaper men, express-agents, bootblacks and boys shouting “Tel-egram!” He has been on the dock only five minutes, when he realizes that the dock itself is unequivocally, uncompromisingly New York.

Being New York, it has at once all the conveniences and all the annoyances known to man, there at his elbow. One can talk by long distance telephone from the pier to any part of the United States; or one can telegraph a “day letter” or a “night letter” and be sure of its delivery in any section of the three-thousand mile continent by eight o’clock next morning. One can check one’s trunks, when they have passed the customs, direct to one’s residence—whether it be Fifth Avenue, New York, or Nob Hill, San Francisco; time, distance, the clumsiness of inanimate things, are dissipated before the eyes of the dazzled stranger.

On the other hand, before even he has set foot on American soil, he becomes acquainted with American arrogance, American indifference, the fantasy of American democracy. The national attitude of I-am-as-good-as-you-are has been conveyed to him through the surly answers of the porter, the cheerful familiarity of the customs examiner, the grinning impudence of the express-man. These excellent public servants would have the foreigner know once and for all that he is in a land where all men are indisputably7 proven free and equal, every minute. The extremely interesting fact that all men are most unequal—slaves to their own potentialities—has still to occur to the American. He is in the stage of doing, not yet of thinking; therefore he finds disgrace in saying “sir” to another man, but none in showing him rudeness.

In a civilization like that of America, where the office-boy of today is the millionaire of tomorrow, and the millionaire of today tomorrow will be begging a job, there cannot exist the hard and fast lines which in older worlds definitely fix one man as a gentleman, another as his servant. Under this management of lightning changes, the most insignificant of the chorus nurses (and with reason) the belief that he may be jumped overnight into the leading rôle. There is something rather fine in the desperate self-confidence of every American in the ultimate rise of his particular star. Out of it, I believe, grows much of that feverish activity which the visitor to New York invariably records among his first impressions. One has barely arrived, and been whirled from the dock into the roar and rush of Twenty-third Street and Broadway, when he begins to realize the relentless energy of the place.

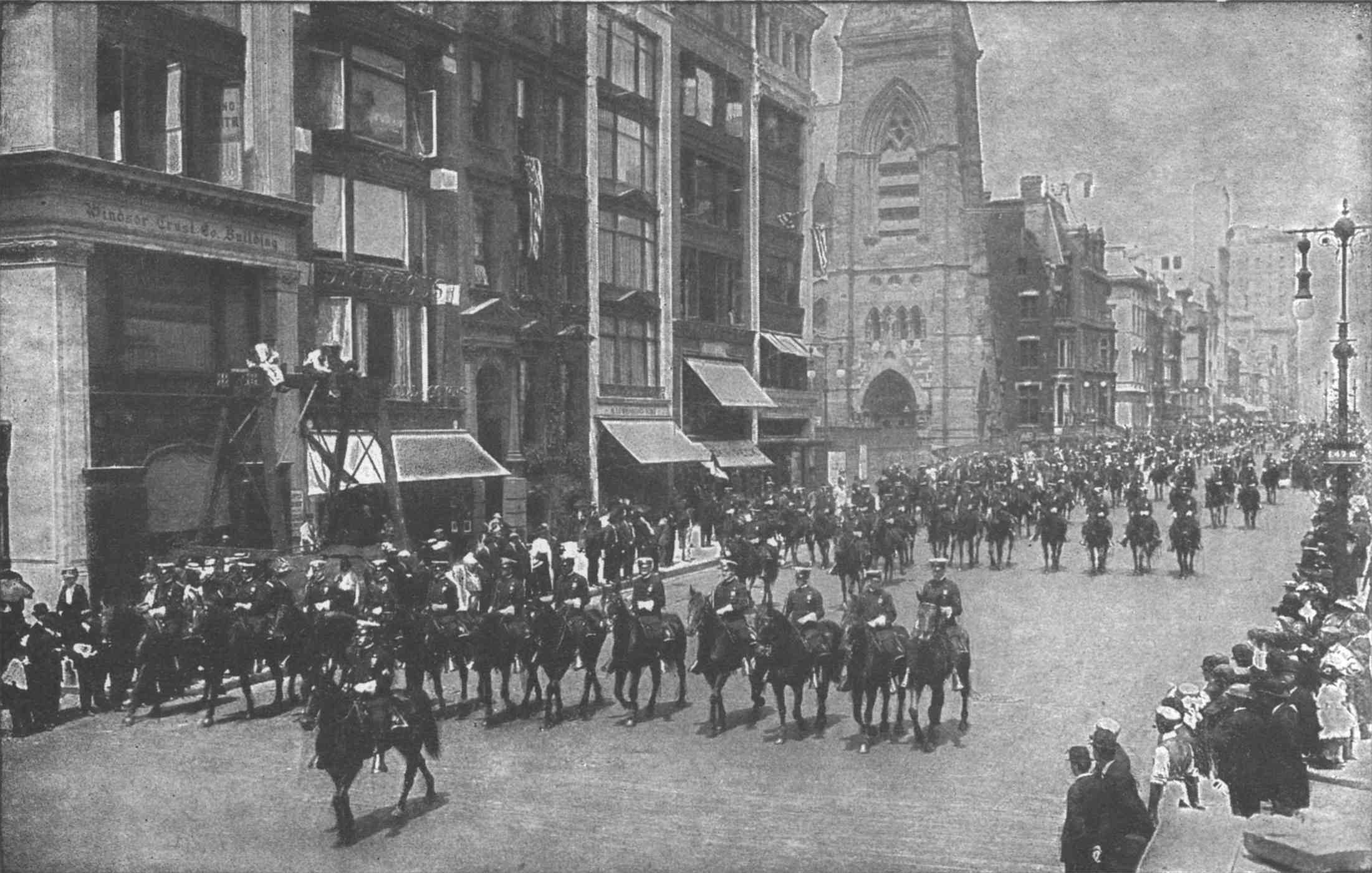

The very wind sweeps along the tunnel-like streets, through the rows of monster buildings, with a speed that takes the breath. In the fiercest of the gale, at the intersection of the two great thoroughfares of Fifth Avenue and Broadway, rises the solid, serene bulk of the Flatiron Building—like a majestic8 Wingèd Victory breasting the storm. Over to the right, in Madison Square, Metropolitan Tower rears its disdainful white loftiness; far above the dusky gold and browns of old Madison Square Garden; above the dwarfed Manhattan Club, the round Byzantine dome of the Madison Square Presbyterian Church. But the Flatiron itself has the proudest site in New York; facing, to the north, on one side the tangle and turmoil of Broadway—its unceasing whirr of business, business, business; on the other side, the broad elegance and dignity of Fifth Avenue, with its impressive cavalcade of mounted police. While East and West, before this giant building, rush the trams and traffic of Twenty-third Street; and to the South lie the arches of aristocratic old Washington Square.

It is as though at this converging point one gathers together all the outstanding threads in the fabric of the city, to visualize its central pattern. And the outstanding types of the city here are gathered also. One sees the ubiquitous “businessman,” in his careful square-shouldered clothes, hurrying from bus to tram, or tearing down-town in a taxi; the almost ubiquitous business-woman, trig and quietly self-confident, on her brisk up-town walk to the office; and the out-of-town woman “shopper,” with her enormous hand-bag, and the anxious-eyed Hebrew “importer” (whose sign reads Maison Marcel), and his stunted little errand-girl darting through the maze of traffic like a fish through well-known waters; the idle young man-about-town, immortalized9 in the sock and collar advertisements of every surface car and Subway; and the equally idle young girl, in her elaborate sameness the prototype of the same cover of the best magazines: even in one day, there comes to be a strange familiarity about all these people.

They are peculiar to their own special class, but within that class they are as like as peas in a pod. They have the same features, wear the same clothes even to a certain shade, and do the same things in identically the same day. With all about them shifting, progressing, alternating from hour to hour, New Yorkers, in themselves, remain unaltered. Or, if they change, they change together as one creature—be he millionaire or Hebrew shop-keeper, doctor of divinity or manager of comic opera. For, of all men under the sun, the New Yorker is a type; acutely suspicious of and instinctively opposed to anything independent of the type. Hence, in spite of the vast numbers of different peoples brought together on Manhattan Island, we find not a community of Americans growing cosmopolitan, but a community of cosmopolitans forced to grow New Yorkers. This, under the potent influence of extreme American adaptability, they do in a remarkably short time; the human potpourri who five years ago had never seen Manhattan, today being indistinguishable in the representative city mass.

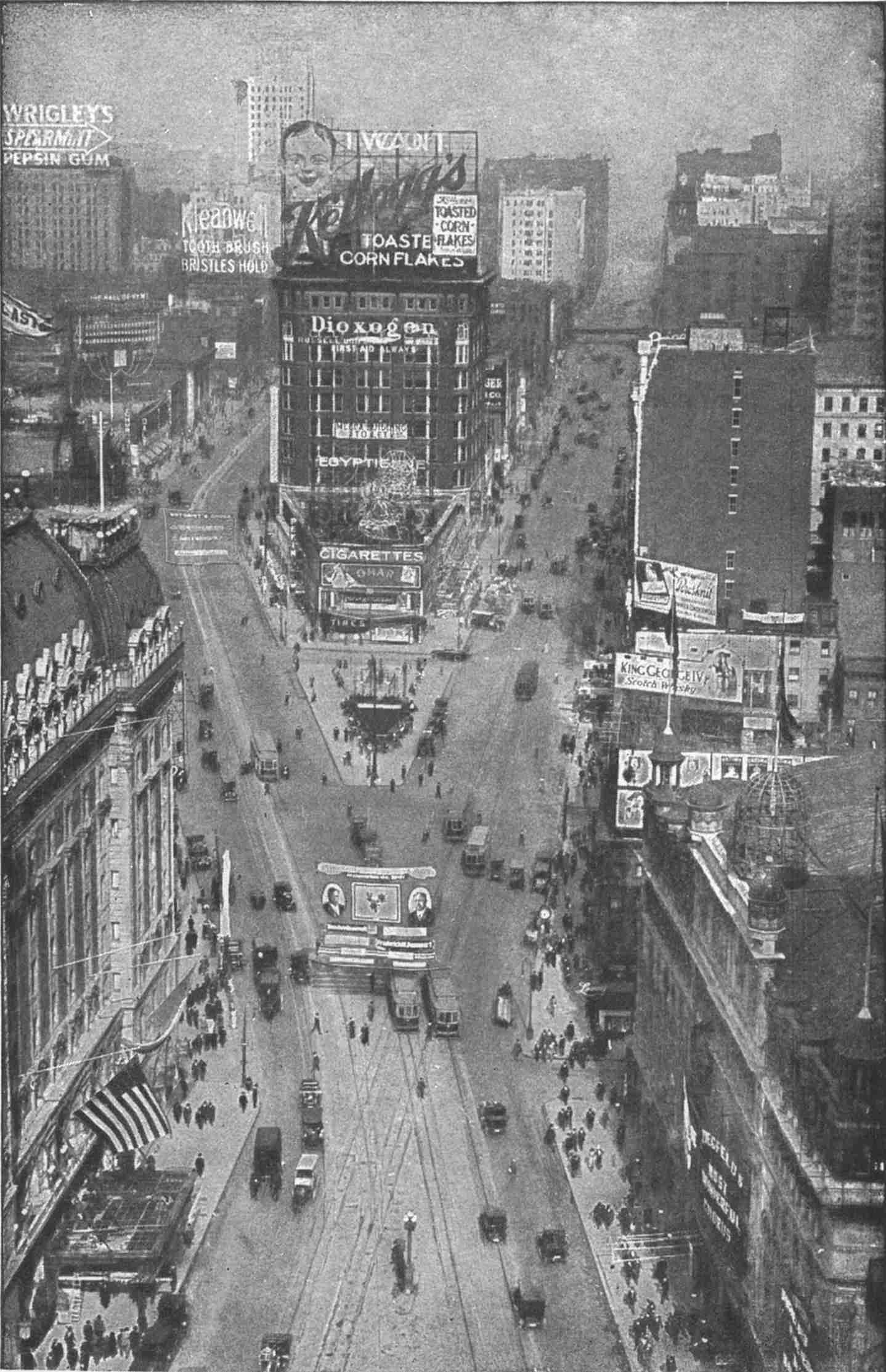

Walk out Fifth Avenue at the hour of afternoon parade, or along Broadway on a matinée day: the habitués of the two promenades differ only in degree.10 Broadway is blatant. Fifth Avenue is desperately toned-down. On Broadway, voices and millinery are a few shades more strident, self-assertion a few shades more arrogant than on the less ingenuous Avenue. Otherwise, what do you find? The same over-animated women, the same over-languid young girls; wearing the same velvets and furs and huge corsage bouquets, and—unhappily—the same pearl powder and rouge, whether they be sixteen or sixty, married or demoiselle. Ten years ago New York could boast the loveliest, naturally beautiful galaxy of young girls in the world; today, since the onslaught of French fashion and artificiality, this is no longer true. On the other hand, it is pitiable to see the hard painted lines and fixed smile of the women of the world in the faces of these girls of seventeen and eighteen who walk up and down the Avenue day after day to stare and be stared at with almost the boldness of a boulevard trotteuse.

Underwood & Underwood

THE AFTERNOON PARADE ON FIFTH AVENUE

Foreigners who watch them from club windows write enthusiastic eulogies in their praise. To me they seem a terrible travesty on all that youth is meant to be. They take their models from pictures of French demi-mondaines shown in ultra-daring race costumes, in the Sunday newspapers; and whom they fondly believe to be great ladies of society. I had almost said that from head to foot they are victims of an entirely false conception of beauty and grace; but when it comes to their feet, they are genuine American, and, so, frank and attractive. Indeed there is no woman as daintily and appropriately shod as the American woman, whose trim short skirts betray this pleasant fact with every step she takes.

Nowhere, however, is appearance and its detail more misrepresentative than in New York. Strangers exclaim at the opulence of the frocks and furs displayed by even the average woman. They have no idea that the average woman lives in a two-by-four hall bedroom—or at best a three-room flat; and that she has saved and scrimped, or more probably gone into debt to acquire that one indispensable good costume. Nor could they imagine that her chief joy in a round of sordid days is parade in it as one of the luxurious throng that crowd Fifth Avenue and its adjacent tea-rooms from four till six every afternoon.

Not only the women of Manhattan itself revel in this daily scene; but their neighbors from Brooklyn, Staten Island, Jersey City and Newark pour in by the hundreds, from the underground tubes and the ferries that connect these places with New York. The whole raison d’être of countless women and girls who live within an hour’s distance of the city is this everyday excursion to their Mecca: the leisurely stroll up Fifth Avenue from Twenty-third Street, down from Fifty-ninth; the cup of tea at one of the rococo hotels along the way. It is a routine of which they never seem to tire—a monotony always new to them. And the pathetic part of it is that while they all—the indigent “roomers,” the anxious suburbanites, and the floating fraction of tourists from the West and12 South—fondly imagine they are beholding the Four Hundred of New York society, they are simply staring at each other!

And accepting each other naïvely at their clothes value. The woman of the hall bedroom receives the same appreciative glance as the woman with a bank account of five figures; provided that outwardly she has achieved the same result. The prime mania of New York is results—or what appear to be results. Every sky-scraper in itself is an exclamation-point of accomplishment. And the matter is not how one accomplishes, but how much; so that the more sluggish European can feel the minutes being snatched and squeezed by these determined people round him and made to yield their very utmost before being allowed to pass into telling hours and days.

With this goes an air of almost offensive competency—an air that is part of the garments of the true New Yorker; as though he and he alone can compass the affair towards which he is forever hurrying. There is about him, always, the piquant insinuation that he is keeping someone waiting; that he can. I have been guilty of suspecting that this attitude, together with his painstakingly correct clothes, constitute the chief elements in the New Yorker’s game of “bluff.” Let him wear what the ready-made tailor describes as “snappy” clothes, and he is at once respected as successful. A man may be living on one meal a day, but if he can contrive a prosperous appearance, together with the preoccupied air of having more business than he can attend to, he is in13 the way of being begged to accept a position, at any moment.

No one is so ready to be “bluffed” as the American who spends his life “bluffing.” In him are united the extremes of ingenuousness and shrewdness; so that often through pretending to be something he is not, he does actually come to be it. A Frenchman or a German or an Englishman is born a barber; he remains a barber and dies a barber, like his father and grandfather before him. His one idea is to be the best barber he can be; to excell every other barber in his street. The American scorns such lack of “push.” If his father is a barber, he himself learns barbering only just well enough to make a living while he looks for a “bigger job.” His mind is not on pleasing his clients, but on himself—five, ten, twenty years hence.

He sees himself a confidential clerk, then manager’s assistant, then manager of an independent business—soap, perhaps; he sees himself taken into partnership, his wife giving dinners, his children sent to college. And so vivid are these possibilities to him, reading and hearing of like histories every day in the newspapers and on the street, that unconsciously he begins to affect the manners and habits of the class he intends to make his own. In an astonishingly short time they are his own; which means that he has taken the main step towards the realization of his dream. It is the outward and visible signs of belonging which eventually bring about that one does belong; and no one is quicker to grasp this than the14 obscure American. He has the instincts of the born climber. He never stops imitating until he dies; and by that time his son is probably governor of the State, and his daughter married to a title. What a people! As a Frenchman has put it, “il n’y a que des phenomènes!”

One cannot conclude an introductory sketch of some of their phenomena without a glance at their amazing architecture. The first complacent question of the newspaper interviewer to every foreigner is: “What do you think of our sky-scrapers?” And one is certainly compelled to do a prodigious deal of thinking about them, whether he will or no. For they are being torn down and hammered up higher, all over New York, till conversation to be carried on in the street must needs become a dialogue in monosyllabic shouts; while walking, in conjunction with the upheavals of new Subway tunnelling, has all the excitements of traversing an earthquake district.

Underwood & Underwood

A PATCH OF THE CRAZY-QUILT BROADWAY, FROM 42d STREET

This perpetual transition finds its motive in the enormous business concentrated on the small island of Manhattan, and the constant increase in office space demanded thereby. The commerce of the city persistently moves north, and the residents flee before it; leaving their fine old Knickerbocker homes to be converted into great department stores, publishing houses, but above all into the omnivorous office-building. The mass of these are hideous—dizzy, squeezed-together abortions of brick and steel—but here and there among the horrors are to be found examples of true if fantastic beauty. The Flatiron 15Building is one, the Woolworth Building (especially in its marvellous illumination by night) another, the new colonnaded offices of the Grand Central Station a third. Yet the general impression of New York architecture upon the average foreigner is of illimitable confusion and ugliness.

It is because the American in art is a Futurist. He so far scorns the ideal as to have done with imagination altogether; substituting for it an invention so titanic in audacity that to the untrained it appears grotesque. In place of the ideal he has set up the one thing greater: truth. And as truth to every man is different (only standard being relatively fixed) how can he hope for concurrence in his masterpiece? The sky-scraper is more than a masterpiece: it is a fact. A fact of violence, of grim struggle, and of victory; over the earth that is too small, and the winds that rage in impotence, and the heavens that heretofore have been useless. It is the accomplished fact of man’s dauntless determination to wrest from the elements that which he sees he needs; and as such it has a beauty too terrible to be described.

16

Here are the two prime motives waging war in the American drama of today. Time is money; whether for the American it is to mean anything more is still a question. Meanwhile every time-saving convenience that can be invented is put at his disposal, be he labouring man or governor of a state. And, as we have seen in the case of the sky-scraper, little or no heed is paid to the form of finish of the invention; its beauty is its practicability for immediate and exhaustive use.

Take that most useful of all, for example: the hotel. An Englishman goes to a hotel when he is obliged to, and then chooses the quietest he can find. Generally it has the appearance of a private house, all but the discreet brass plate on the door. He rings for a servant to admit him; his meals are served in his rooms, and weeks go by without his seeing another guest in the house. The idea is to make the hotel in as far as possible duplicate the home.

In America it is the other way round; the New Yorker in particular models his home after his hotel, and seizes every opportunity to close his own house17 and live for weeks at a time in one of the huge caravanseries that gobble up great areas of the city. “It is so convenient,” he tells you, lounging in the gaudy lobby of one of these hideous terra-cotta structures. “No servant problem, no housekeeping worries for madame, and everything we want within reach of the telephone bell!”

Quite true, when the pompadoured princess below-stairs condescends to answer it. Otherwise you may sit in impotent rage, ten stories up, while she finishes a twenty-minute conversation with her “friend” or arranges to go to a “show” with the head barber; for in all this palace of marble staircases and frescoed ceilings, Louis Quinze suites and Russian baths there is not an ordinary bell in the room to call a servant. Everything must be ordered by telephone; and what boots it that there is a telegraph office, a stock exchange bureau, a ladies’ outfitting shop, a railroad agency, a notary, a pharmacist and an osteopath in the building—if to control these conveniences one must wander through miles of corridors and be shot up and down a dozen lifts, because the telephone girl refuses to answer?

From personal experience, I should say that the servant problem is quite as tormenting in hotels as in most other American establishments. The condescension of these worthies, when they deign to supply you with some simple want, is amazing. Not only in hotels, but in well-run private houses, they seize every chance for conversation, and always turn to the subject of their own affairs—their former prosperity,18 the mere temporary necessity of their being in service, and their glowing prospects for the future. They insist on giving you their confidential opinion of the establishment in which you are a guest, and which is invariably far inferior to others in which they have been employed. They comment amiably on your garments, if they are pleased with them, or are quite as ready to convey that they are not. And woe to him who shows resentment! He may beseech their service henceforth in vain. If, however, he meekly accepts them as they are, they will graciously be pleased to perform for him the duties for which they are paid fabulous wages.

Hotel servants constitute the aristocracy among “domestics,” as they prefer to call themselves; just as hotel dwellers—of the more luxurious type—constitute a kind of aristocracy among third-rate society in New York. These people lead a strange, unreal sort of existence, living as it were in a thickly gilded, thickly padded vacuum, whence they issue periodically into the hands of a retinue of hangers-on: manicures, masseurs, hair-dressers, and for the men a train of speculators and sporting parasites. In this world, where there are no definite duties or responsibilities, there are naturally no fixed hours for anything. Meals occur when the caprice of the individual demands them—breakfast at one, or at three, if he likes; dinner at the supper hour, or, instead of tea, a restaurant is always at his elbow. With the same irresponsibility, engagements are broken or kept an hour late; agreements are forfeited or forgotten altogether;19 order of any sort is unknown, and the only activity of this large class of wealthy people is a hectic, unregulated striving after pleasure.

Women especially grow into hotel fungi of this description, sitting about the hot, over-decorated lobbies and in the huge, crowded restaurants, with nothing to do but stare and be stared at. They are a curious by-product of the energetic, capable American woman in general; and one thinks there might be salvation for them in the “housekeeping” worries they disdainfully repudiate. Still, it cannot be denied that with the serious problem of servants and the exorbitant prices of household commodities a home is far more difficult to maintain in America than in the average modern country. Hospitality under the present conditions presents features slightly careworn; and the New York hostess is apt to be more anxious than charming, and to end her career on the dismal verandas of a sanatorium for nervous diseases.

But society the world round has very much the same character. For types peculiar to a country, one must descend the ladder to rungs nearer the native soil; in New York there are the John Browns of Harlem, for example. No one outside America has heard of Harlem. Does the loyal Englishman abroad speak of Hammersmith? Does the Frenchman en voyage descant on the beauties of the Batignolles? These abominations are locked within the national bosom; only Hyde Park and the Champs Elysées and Fifth Avenue are allowed out for alien gaze. Yet quite as emphatic of New York struggle and achievement20 as the few score millionaire palaces along the avenue are the tens of thousands of cramped Harlem flats that overspread the northern end of the island from One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street to the Bronx. For tens of thousands of John Browns have daily to wage war in the deadly field of American commercial competition, in order to pay the rent and the gas bill, and the monthly installment on the furniture of these miniature homes. They have not, however, to pay for the electric light, or the hot-water heating, or a dozen other comforts which are a recurring source of amazement to the foreigner in such a place. For twenty dollars a month, John Brown and his wife are furnished not only with three rooms and a luxurious porcelain bath in a white-tiled bathroom; but also the use of two lifts, the inexhaustible services of the janitor, a comfortable roof garden in summer, and an imposing entrance hall downstairs, done in imitation Carrara marble and imitation Cordova leather. With this goes a still more imposing address, and Mrs. John can rouse the eternal envy of the weary Sixth Avenue shop-girl by ordering her lemon-squeezer or two yards of linoleum sent to “Marie Antoinette Court,” or “The Cornwallis Arms.” The shop-girl understands that Mrs. John’s husband is a success.

That is, that he earns in the neighborhood of a hundred dollars a month. With this he can afford to pay the household expenses, to dress himself and his wife a bit better than their position demands, to subscribe to two or three of the ten-cent magazines,21 and to do a play on Broadway now and then. Mrs. John of course is a matinée fiend, and has the candy habit. These excesses must be provided for; also John’s five-cent cigars and his occasional mild “spree with the boys.” For the rest, they are a prudent couple; methodically religious, inordinately moral; banking a few dollars every month against the menacing rainy-day, and, if this has not arrived by vacation time in August, promptly spending the money on the lurid delights of Atlantic City or some other ocean resort. Thence they return haggard but triumphant, with a coat of tan laboriously acquired by wetting faces and arms, and then sitting for hours in the broiling sun—to impress the Tom Smiths in the flat next door that they have had a “perfectly grand time.”

A naïve, hard-working, kindly couple, severely conventional in their prejudices, impressionable as children in their affections, and with a certain persistent cleverness that shoots beyond the limitations of their type, and hints to them of the habits and manners of a finer. In them the passionate motive of self-development that dominates all American life has so far found an outlet only in demand for the conveniences and material comforts of the further advanced whom they imitate. When in the natural course of things they turn their eyes towards the culture of the Man Higher Up, they will obtain that, too. And meanwhile does not Mrs. Brown have her Tennyson Club, and John his uniform edition of Shakespeare?

Some New Yorkers who shudder at Harlem are not as lucky. I was once the guest of a lady who had22 just moved into her sumptuous new home on Riverside Drive. My rooms, to quote the first-class hotel circular, were replete with every luxury; I could turn on the light from seven different places; I could make the chairs into couches or the couches into chairs; I could talk by one of the marvellous ebony and silver telephones to the valet or the cook, or if I pleased to Chicago. There was nothing mortal man could invent that had not been put in those rooms, including six varieties of reading-lamps, and a bed-reading-table that shot out and arranged itself obligingly when one pushed a button.

But there was nothing to read. Apologetically, I sought my hostess. Would she allow me to pilfer the library? For a moment the lady looked blank. Then, with a smile of relief, she said: “Of course! You want some magazines. How stupid of the servants. I’ll have them sent to you at once; but you know we have no library. I think books are so ugly, don’t you?”

I am not hopelessly addicted to veracity, but I will set my hand and seal to this story; also to the fact that in all that palace of the superfluous there was not to my knowledge one book of any sort. Even the favourite whipped-cream novel of society was wanting; but magazines of every kind and description littered the place. The reason for this apparently inexplicable state of affairs is simple; time is money; therefore not to be expended without calculation. In the magazine the rushed business man, and the equally rushed business or society woman, has a literary23 quick-lunch that can be swallowed in convenient bites at odd moments during the day.

Is the business man dining out? He looks at the reviews of books he has not read on the way to his office in the morning; criticisms of plays he has not seen, on the way back at night. Half an hour of magazine is made thus to yield some eight hours of theatre and twenty-four of reading books—and his vis-à-vis at dinner records at next day’s tea party, “what a well-informed man that Mr. Worriton is! He seems to find time for everything.”

Is the society woman “looking in” at an important reception? Between a fitting at her dressmaker’s, luncheon, bridge and two teas, she catches up the last Review from the pocket of her limousine, and runs over the political notes, war news, foreign events of the week. Result: “that Mrs. Newrich is really a remarkable woman!” declares the distinguished guest of the reception to his hostess. “Such a breadth of interest, such an intelligent outlook! It is genuine pleasure to meet a woman who shows some acquaintance with the affairs of the day.”

And so again they hoodwink one another, each practicing the same deceptive game of superficial show; yet none suspecting any of the rest. And the magazine syndicates flourish and multiply. In this piece that is in preparation, the actors are too busy proving themselves capable of their parts really to take time to become so. To succeed with them, you must offer your dose in tabloids: highly concentrated essence of whatever it is, and always sugar-coated.24 Then they will swallow it promptly, and demand more. Remember, too, that what they want in the way of “culture” is not drama, or literature, or music; but excitement—of admiration, pity, the erotic or the sternly moral sense. Their nerves must be kept at a certain perpetual tension. He who overlooks this supreme fact, in creating for them, fails.

There are in America today some thousands of men and women who have taken the one step further than their fellows in that they realize this, and so are able shrewdly to pander to the national appetites. The result is a continuous outpouring of novels and short stories, plays and hybrid songs, such as in a less vast and less extravagant country would ruin one another by their very multitude; but which in the United States meet with an appalling success. Appalling, because it is not a primitive, but a too exotic, fancy that delights in them. For his mind as for his body, the American demands an overheated dwelling; when not plunged within the hectic details of a “best-seller,” by way of recreation, he is apt to be immersed in the florid joys of a Broadway extravaganza.

These unique American productions, made up of large beauty choruses, magnificent scenery, gorgeous costumes, elaborate fantasies of ballet and song, bear the same relation to actual drama that the best-sellers bear to literature, and are as popular. The Hippodrome, with its huge stage accommodating four hundred people, and its enormous central tank for water spectacles, is easily first among the extravaganza houses of New York. Twice a day an eager audience,25 drawn from all classes of metropolitan and transient society, crowds the great amphitheatre to the doors. The performance prepared for them is on the order of a French révue: a combination circus and vaudeville, held together by a thin thread of plot that permits the white-flannelled youth and bejewelled maiden, who have faithfully exclaimed over each new sensation of the piece, finally to embrace one another, with the novel cry of “at last!”

Meanwhile kangaroos engage in a boxing match, hippopotami splash most of the reservoir over the “South Sea Girls”; the Monte Carlo Casino presents its hoary tables as background for the “Dance of the Jeunesse Dorée,” and Maoris from New Zealand give an imitation of an army of tarantulas writhing from one side of the stage to another. The climax is a stupendous tableau en pyramide of fountains, marble staircases, gilded thrones, and opalescent canopies; built up, banked, and held together by girls of every costume and complexion. Nothing succeeds in New York without girls; the more there are, the more triumphant the success. So the Hippodrome, being in every way triumphant, has mountains of them: tall girls and little girls, Spanish girls, Japanese girls, Hindoo girls and French girls; and at the very top of the peak, where the “spot” points its dazzling ray, the American girl, wrapped in the Stars and Stripes of her apotheosis. Ecco! The last word has been said; applause thunders to the rafters; the flag is unfurled, to show the maiden in the victorious garb of a Captain of the Volunteers; and the curtain26 falls amid the lusty strains of the national anthem. Everybody goes home happy, and the box office nets five thousand dollars. They know the value of patriotism, these good Hebrews.

This sentiment, always near the surface with Americans, grows deeper and more fervid as it localizes; leading to a curiously intense snobbism on the part of one section of the country towards another. Thus New York society sniffs at Westerners; let them approach the citadel ever so heavily armed with gold mines, they have a long siege before it surrenders to them. On the other hand, the same society smiles eagerly upon Southerners of no pocket-books at all; and feeds and fêtes and fawns upon them, because they are doomed, the minute their Southern accent is heard, to come of “a good old family.” The idea of a decayed aristocracy in two-hundred-year-old America is not without comedy, but in the States Southerners are taken very solemnly, by themselves as by everyone else.

My friend of the æsthetic antipathy to books (really a delightful person) is a Southerner—or was, before gathered into the fold of the New York Four Hundred. She apologized for taking me to the Horse Show (which she thought might amuse me, however), because “no one goes any more. It’s all Middle West and commuters.” For the benefit of those imperfect in social geography I must explain that Middle West is the one thing worse than West, and that commuters are those unfortunates without the sacred pale, who are forced to journey to and27 from Manhattan by ferries or underground tubes. They are the butt of comic newspaper supplements, topical songs, and society witticisms; also the despised and over-charged “out-of-town customers” of the haughty Fifth Avenue importer.

For the latter (a phenomenon unique to New York) has her own system of snobbism, quite as elaborate as that of her proudest client. They are really a remarkable mixture of superciliousness and abject servility, these Irish and Hebrew “Madame Celestes,” whose thriving establishments form so conspicuous a part of the important avenue. As exponents of the vagaries of American democracy, they deserve a paragraph to themselves.

Each has her rococo shop, and her retinue of mannequin assistants garbed in the extreme of fashion; each makes her yearly or bi-yearly trip to Paris, from which she returns with strange and bizarre creations, which she assures her patrons are the “only thing” being worn by Parisiennes this season. Now even the untutored male knows that there is never an “only thing” favoured by the capricious and original Parisienne; but that she changes with every wind, and in all seasons wears everything under the sun (including ankle-bracelets and Cubist hats), provided it has the one hall-mark: chic.

But Madame New York meekly accepts the Irish lady’s dictum, and arrays herself accordingly—with what result of extravagant monotony we shall see later on. Enough for the present that she is absolutely submissive to the vulgar taste and iron decrees28 of the rubicund “Celeste” from Cork, and that the latter alternately condescends and grovels to her, in a manner amazing to the foreigner, who may be looking on. Yet on second thoughts it is quite explicable: after the habit of all Americans, native or naturalized, “Celeste” cannot conceal that she considers herself “as good as” anyone, if not a shade better than some. At the same time, again truly American, she worships the dollars madame represents (and whose aggregate she can quote to a decimal), and respects the lady in proportion. Hence her bewildering combinations of “certainly, Madame—it shall be exactly as Madame orders,” with “Oh, my dear, I wouldn’t have that! Why, girlie, that on you with your dark skin would look like sky-blue on an Indian! But, see, dear, here’s a pretty pink model”—etc., etc.

And so it continues, unctuous deference sandwiched between endearments and snubs throughout the entire conference of shopkeeper and customer; and the latter takes it all as a matter of course, though, if her own husband should venture to disagree with her on any point of judgment, she would be furious with him for a week. When I commented to one lady on these familiar blandishments and criticisms of shop people in New York, she said indulgently: “Oh, they all do it. They don’t mean anything; it’s only their way.”

Yet I have heard that same lady hotly protest against the wife of a Colorado silver magnate (whom she had known for years) daring to address her by her Christian name. “That vulgar Westerner!” she29 exclaimed; “the next thing she’ll be calling me dear!”

Democracy remains democracy as long as it cannot possibly encroach upon the social sphere; the moment the boundary is passed, however, and the successful “climber” threatens equal footing with the grande dame on the other side, herself still climbing in England or Europe, anathema! The fact is, that Americans, like all other very young people, seek to hide their lack of assurance—social and otherwise—by an aggressive policy of defense which they call independence; but which is verily snobbism of the most virulent brand. From the John Browns to the multimillionaires with daughters who are duchesses, they are intent on emphasizing their own position and its privileges; unconscious that if they themselves were sure of it so would be everyone else.

But inevitably the actors must stumble and stammer, and insert false lines, before finally they shall “feel” their parts, and forge ahead to the victory of finished performance.

30

When one ponders what the New Yorker in his leisure hours most enjoys, one answers without hesitation: feeding. The word is not elegant, but neither is the act, as one sees it in process at the mammoth restaurants. Far heavier and more prolonged than mere eating and drinking is this serious cult of food on the part of the average Manhattanite. It has even led to the forming of a distinct “set,” christened by some satirical outsider: “Lobster Society.”

Here are met the moneyed plutocrat and his exuberant “lady friend,” the mauve-waistcoated sporting man, the society déclassée with her gorgeous jewels and little air of tragedy, the expansive Hebrew and his chorus girl, the gauche out-of-town couple with their beaming smiles and last season’s clothes: all that hazy limbo that hovers on the social boundary-line, but hovers futilely—and that seeks to smother its disappointment with elaborate feasts of over-rich food.

Underwood & Underwood

“NEW YORK’S FINEST”: THE FAMOUS MOUNTED POLICE SQUAD

It is amazing the thousands of these people that there are—New York seems to breed them faster than any other type; and the hundreds of restaurants they support. Every hotel has its three or four huge 31dining-rooms, its Palm Garden, Dutch Grill, etc.; but, as all these were not enough, shrewd Frenchmen and Germans and Viennese have dotted the city with cafés and brauhausen and Little Hungaries, to say nothing of the alarming Egyptian and Turkish abortions that are the favourite erection of the American restaurateur himself.

The typical New York feeding-place from the outside is a palace in terra cotta; from the inside, a vast galleried room or set of rooms, upheld by rose or ochre marble pillars, carpeted with thick red rugs, furnished with bright gilt chairs and heavily damasked, flower-laden tables—the whole interspersed and overtopped and surrounded by a jumble of fountains, gilt-and-onyx Sphinxes, caryatids, centaurs, bacchantes, and heaven knows what else of the superfluous and disassociated. To reach one’s table, one must thread one’s way through a maze of lions couchant, peacocks with spread mother o’ pearl tails, and opalescent dragons that turn out to be lights: proud detail of the “million dollar decorative scheme” referred to in the advertisements of the house. Finally anchored in this sea of sumptuousness, one is confronted with the dire necessity of ordering a meal from a menu that would have staggered Epicurus.

There is the table d’hôte of nine courses—any one of them a meal in itself; or there is the bewildering carte du jour, from which to choose strawberries in December, oranges in May, or whatever collection of ruinous exotics one pleases. The New Yorker himself goes methodically down the list, from oysters to32 iced pudding; impartial in his recognition of the merits of lobster bisque, sole au gratin, creamed sweetbreads, porterhouse steak, broiled partridge and Russian salad. He sits down to this orgy about seven o’clock, and rises—or is assisted to rise—about ten or half past, unless he is going on to a play, in which case he disposes of his nine courses with the same lightning execution displayed at his quick-lunch, only increasing his drink supply to facilitate the process.

Meanwhile there is the “Neapolitan Quartet,” and the Hungarian Rhapsodist, and the lady in the pink satin blouse who sings “The Rosary,” to amuse our up-to-date Nero. I wonder what the Romans would make of the modern cabaret? Like so many French importations, stripped in transit of their saving coat of French esprit, the cabaret in American becomes helplessly vulgar. Extreme youth cannot carry off the risqué, which requires the salt of worldly wisdom; it only succeeds in being rowdy. And the noisy songs, the loud jokes, the blatant dances—all the spurious clap-trap which in these New York feeding-resorts passes for amusement—point to the most youthful sort of rowdyism: to a popular discrimination still in embryo. But the New Yorker dotes on it—the cabaret, I mean; if for no other reason, because it satisfies his passion for getting his money’s worth. He is ready to pay a handsome price, but he demands handsome return, and no “extras” if you please.

When the ten-cent charge for bread and butter33 was inaugurated by New York restaurateurs last Spring, their patrons were furious; it hinted of the parsimonious European charge for “cover.” But if the short-sighted proprietors had quietly added five cents to the price of each article on the menu, it would have passed unnoticed: it is not paying that the American minds, it is “being done.” Conceal from him this humiliating consciousness, and he will empty his pockets. Thus, at the theatre, seats are considerably higher than in European cities, but they are also far more comfortable; and include a program, sufficient room for one’s hat and wrap, the free services of the usher, and as many glasses of the beloved ice-water as one cares to call for. People would not tolerate being disturbed throughout the performance by the incessant demands for a “petite service” and other supplements that persecute the Continental theatre-goer; while as for being forced to leave one’s wraps in a garde-robe, and to pay for the privilege of fighting to recover them, the independent American would snort at the bare idea. He insists on a maximum amount of comfort for his money, and on paying for it in a lump sum, either at the beginning or at the end. Convenience, the almighty god, acknowledges no limits to its sway.

It was convenience that until recently made it the custom for the average New York play-goer to appear at the theatre in morning dress. The tired business man could afford to go to the play, but had not the energy to change for it; so, naturally, his wife and daughter did not change either, and the orchestra34 presented a commonplace aspect, made up of shirtwaists and high-buttoned coats. Now, however, following the example of society, people are beginning to break away from this unattractive austerity; and theatre audiences are enlivened by a sprinkling of light frocks and white shirts.

We have already commented on the most popular type of dramatic amusement in America: the extravaganza, and musical comedy so-called; it is time now to mention the gradually developing legitimate drama, which has its able exponents in Augustus Thomas, Edward Sheldon, Eugene Walter, the late Clyde Fitch, and half a dozen others of no less insight and ability. Their plays present the stirring and highly dramatic scenes of American business and social life (using social in its original sense); and while for the foreigner many of the situations lose their full significance—being peculiar to America, in rather greater degree than French plays are peculiar to France, and English to England—even he must be impressed with the vivid realism and powerful climax of the best American comedies.

The nation as a whole is vehemently opposed to tragedy in any form, and demands of books and plays alike that they invariably shall end well. Such brilliant exceptions as Eugene Walter’s “The Easiest Way” and Sheldon’s “The Nigger,” only prove the rule that the successful piece must have a “happy ending.” High finance plays naturally an important part as nucleus of plots; also the marriage of working girls with scions of the Upper Ten. But the35 playwright has only to look into the newspapers, in this country of perpetual adventure, to find enough romance and sensation to fill every theatre in New York.

It seems almost as though the people themselves are surfeited with the actual drama that surrounds them, for they are rather languid as an audience, and must be piqued by more and more startling “thrillers” before moved to enthusiasm. Even then their applause is usually directed towards the “star,” in whom they take far keener interest than in the play itself. It is interesting to follow this passionate individualism of the nation that dominates its amusements as well as its activities. The player, not the play’s the thing with Americans; and on theatrical bills the name of the principal actor or actress is always given the largest type, the title of the piece next largest; while the author is tucked away like an afterthought in letters that can just be seen.

The acute American business man, who is always a business man, whether financing a railroad or a Broadway farce, is not slow to profit by the penchant of the public for “big” names. By means of unlimited advertising and the right kind of notoriety, he builds up ordinary actors into valuable theatrical properties. Given a comedian of average talent, average good looks, and an average amount of magnetism, and a clever press agent: he has a star! This brilliant being draws five times the salary of the leading lady of former years (a woman star is obviously a shade or two more radiant than a man), and in return36 has only to confide her life history and beauty recipés to her adoring public, via the current magazines. Furthermore stars are received with open arms by Society (which leading ladies were not), and may be divorced oftener than other people without injury—rather with distinct advantage—to their reputation. Each new divorce gives a fillip to the public curiosity, and so brings in money to the box office.

Not only in the field of the “legitimate” is a big name the all-important asset of an artist. Ladies who have figured in murder trials, gentlemen whom circumstantial evidence alone has failed to prove assassins, are eagerly sought after by enterprising vaudeville managers, who beg them to accept the paltry sum of a thousand dollars a week, for showing themselves to curious crowds, and delivering a ten-minute monologue on the deficiencies of American law! How or why the name has become “big” is a matter of only financial moment; and Americans of rigid respectability flock to stare at ex-criminals, members of the under-world temporarily in the limelight, and young persons whose sole claim to distinction lies in the glamour shed by one-time royal favour. Thanks to press agents and newspapers, the affairs of this motley collection—as indeed of “stars” of every lustre—are so constantly and so intimately before the public, that one hears people of all classes discussing them as though they were their lifelong friends.

Thus at the theatre: “Oh, no, the play isn’t anything, but I come to see Laura Lee. Isn’t she stunning?37 You ought to see her in blue—she says herself blue’s her colour. I don’t think much of these dresses she’s wearing tonight; she got them at Héloïse’s. Now generally she gets her things at Robert’s—she says Robert just suits her genre.”

Again, at the restaurant: “How seedy May Morris is looking—there she is, over by the window. You know she divorced her first husband because he made her pay the rent, and now she’s leading a cat-and-dog life with this one because he’s jealous of the manager. That’s Mrs. Willy Spry who just spoke to her; well, I didn’t know she knew her!”

What they do not know about celebrities of all sorts would be hard to teach Americans, particularly the women. They can tell you how many eggs Caruso eats for breakfast, and describe to the last rosebush Maude Adams’ country home; their interest in the drama and music these people interpret trails along tepidly, in wake of their worship for the successful individual. Americans are not a musical people. They go to opera because it is fashionable to be seen there, and to concerts and recitals for the most part because they confer the proper æsthetic touch. But only a handful have any real knowledge or love of music, and that handful is continually crucified by the indifference of the rest. I can think of no more painful experience for a sincere music-lover than to attend a performance at the Metropolitan Opera; and this not only because people are continually coming in and going out, destroying the continuity of the piece, but because the latter itself is carelessly executed and38 often faulty. Here again the quartet of exorbitantly paid stars are charged with the success of the entire performance; the conductor is an insignificant quantity, and the chorus goes its lackadaisical way unheeded—even smiling and exchanging remarks in the background, with no one the wiser. From a box near the stage I once saw two priests in “Aïda” jocosely tweak one another’s beards just at the moment of the majestic finale. Why not? The audience, if it pays attention to the opera at all, pays it to Caruso and Destinn and Homer—to the big name and the big voice; not to petty detail such as chorus and mise-en-scène.

But of course opera is the last thing for which people buy ten-dollar seats at the Metropolitan. The “Golden Horse-Shoe” is the spectacle they pay to see; the masterpieces of Céleste and Héloïse (as exhibited by Madame Millions and her intimates) rather than the masterpieces of Wagner or Puccini lure them within the great amphitheatre. And certain it is that the famous double tier of boxes boasts more beautiful women, gorgeously arrayed, than any other place of assembly in America. Yet as I first saw them, from my modest seat in the orchestra, they appeared to be a collection of radiant Venuses sitting in gilded bathtubs: above the high box-rail, only rows of gleaming shoulders, marvellously dressed heads, and winking jewels were visible. Later, in the foyer, I discovered that some of them at least were more modernly attired than the lady who rose from the sea, but the first impression has always remained the more vivid.

39

Society—ever deliciously naïve in airing its ignorance—is heard to express some quaint criticisms at opera. At a performance of Tristan, I sat next a débutante who had the reputation of being “musical.” In the midst of the glorious second act, she whispered plaintively, “I do hate it when our night falls on Tristan—it’s such a sad story!”

It will be interesting to follow New York musical education, if the indefatigable Mr. Hammerstein succeeds in his present proposal to offer the lighter French and Italian operas at popular prices. Hitherto music along with every other art in America has been so commercialized that wealth rather than appreciation and true fondness has controlled it. But meanwhile there has developed, instinctively and irrepressibly, the much disparaged ragtime. It is the pose among musical précieux loudly to decry any suggestion of ragtime as a national art; yet the fact remains that it has grown up spontaneously as the popular and the only distinctly American form of musical expression. Of course, the old shuffling clog-dances of the negroes were responsible for it in the beginning. I was visiting some Americans in Tokio when a portfolio of the “new music” was sent out to them (1899), and I remember that it consisted entirely of cakewalks and “coon songs,” with negro titles and pictures of negroes dancing, on the cover. But this has long since ceased to be characteristic of ragtime as a whole, which takes its inspiration from every phase of nervous, precipitate American life.

In the jerky, syncopated measures, one can almost40 hear between beats the familiar rush of feet, hurrying along—stumbling—halting abruptly—only to fly ahead faster. Ragtime is the pell-mell, helter-skelter, headlong spirit of America expressed in tune; and no other people, however charmed by its peculiar fascination and wild swing, can play or dance to it like Americans. It is instinctive with them; where classical music, so called, is a laboriously acquired taste.

New Yorkers in particular take their artistic hobbies very seriously; not only music and the conventional arts, but all those occult and mystic off-shoots that abound wherever there are idle people. To assuage the ennui that dogs excessive wealth, they devote themselves to all sorts of cults and intricate beliefs. Swamis, crystal-gazers, astrologers, mind-readers, and Messiahs of every kind and colour reap a luxurious harvest in New York. Women especially have a new creed for every month in the year; and discuss “the aura,” and “the submerged self,” and the “spiritual significance of colour,” with profound solemnity. On being presented to a lady, you are apt to be asked your birth date, the number of letters in your Christian name, your favourite hue, and other momentous questions that must be cleared away before acquaintance can proceed, or even begin at all.

“John?” cries the lady. “I knew you were a John, the minute I saw you! Now, what do you think I am?”

You are sure to say a “Mabel” where she is an “Edith,” or a Gladys where she is a Helen, or to commit some other blunder which takes the better part41 of an hour to be explained to you. Week-end parties are perfect hot-beds of occultism, each guest striving to out-argue every other in the race to gain proselytes for his religion of the moment.

The American house-party on the whole is a much more serious affair than its original English model. The anxious American hostess never quite gains that casual, easy manner of putting her house at the disposal of her guests, and then forgetting it and them. She must be always “entertaining,” than which there is no more dreary persecution for the long-suffering visitor. Except for this, her hospitality is delightful; and it is a joy to leave the dust and roar of New York, and motor out to one of the many charming country houses on Long Island or up the Hudson for a peaceful week-end. Americans show great good sense in clinging to their native Colonial architecture, which lends itself admirably to the simple, well-kept lawns and old-fashioned gardens. In comparison with country estates of the old world, one misses the dignity of ancient stone and trees; but gains the airy openness and many luxuries of modern comfort.

As for country life in general, it is further advanced than on the Continent, but not so far advanced as in England. Americans, being a young people, are naturally an informal people, however they may rig themselves out when they are on show. They love informal clothes, and customs, and the happy-go-lucky freedom of out-of-doors. On the other hand, they are not a sporting people, except by individuals. They are athletes rather than sportsmen;42 the passion for individual prowess being very strong, the devotion to sport for sport’s sake much less in evidence. The spirit of competition is as keen in the athletic field as it is in Wall Street; and at the intercollegiate games enthusiasm is always centred on the particular hero of each side, rather than on the play of the team as a whole. The American in general distinguishes himself in the “individual” rather than the team sports—in running, swimming, skating, and tennis; all of which display to fine advantage his wiry, lean agility.

At the same time, there is nothing more typically American or more inspiring to watch than one of the great collegiate team games, when thirty thousand spectators are massed round the field, breathlessly intent on every detail. Even in an immense city like New York, on the day of a big game, one feels a peculiar excitement in the air. The hotels are full of eager boys with sweaters, through the streets dash gaily decorated motors, and the stations are crowded with fathers, mothers, sisters and sweethearts on their way to cheer their particular hopeful. For once, too, the harassed man of affairs throws business to the four winds, remembers only that he is an “old grad” of Harvard or Princeton or Yale, and hurries off to cheer for his Alma Mater.

Then at the field there are the two vast semicircles of challenging colours, the advance “rooting”—the songs, yells, ringing of bells and tooting of horns—that grows to positive frenzy as the two contesting teams come in and take their places. And, as the43 game proceeds, the still more fervent shouts—middle-aged men standing up on their seats and bawling three-times-threes, young girls laughing, crying, splitting their gloves in madness of applause, small boys screeching encouragement to “our side,” withering taunts to the opponents; and then all at once a deathly hush—in such a huge congregation twice as impressive as all their noise—while a goal is made or a home base run. And the enthusiasm breaks forth more furious than ever.

We are a long way now from the stodgy, dull-eyed diner-out, in his murky lair; now, we are looking on at youth at its best—its most eager and unconscious; in which guise Americans in their vivid charm are irresistible.

44

There is no woman in modern times of whom so much has been written, so little said, as of the American woman. Essayists have echoed one another in pronouncing her the handsomest, the best dressed, the most virtuous, and altogether the most attractive woman the world round. Psychologists have let her carefully alone; she is not a simple problem to expound. She is, however, a most interesting one, and I have not the courage to slight her with the usual cursory remarks on eyes, hair, and figure. She deserves a second and more searching glance.

To her own countrymen she is a goddess on a pedestal that never totters; to the foreigner she is a pretty, restless, thoroughly selfish female, who roams the earth at scandalous liberty, while her husband sits at home and posts checks. Naturally, the truth—if one can get at truth regarding such a complex creature—falls between these two conceptions: the American woman is a splendid, faulty human being, in whom the extremes of human weakness and nobility seem surely to have met. She is the product of the extreme Western philosophy of absolute individualism,45 and as such is constituted a law unto herself, which she defies the world to gainsay. At the same time she knows herself so little that she changes and contradicts this law constantly, thus bewildering those who are trying to understand it and her.

For example, we are convinced of her independence. We go with her to the milliner’s. She wants a hat with plumes. “Oh, but, my dear,” says the saleslady reprovingly, “they aren’t wearing plumes this season—they aren’t wearing them at all. Everybody is having Paradise feathers.” Madame New York instantly declares that in that case she must have Paradise feathers, too, and is thoroughly content when the same are added to the nine hundred and ninety-nine other feathers that flutter out the avenue next afternoon. Plumes may be far more becoming to her; in her heart she may secretly regret them; but she must have what everyone else has. She has not the independence to break away from the herd.

And so it is with all her costume, her coiffure, the very bag on her wrist and brooch at her throat: every detail must be that detail of the type. She neither dares nor knows how to be different. But, within the stronghold of the type, she dares anything. Are “they” wearing narrow skirts? Every New York woman challenges every other, with her frock three inches tighter than the last lady’s. Are they slashing skirts to the ankle in Paris? Madame New York slashes hers to the shoe-tops, always provided she has the concurrence of “those” of Manhattan. Once secured by the sanction of the mass, her instinct for exaggeration46 is unleashed; her perverse imagination shakes off its chronic torpor, and soars to flights of fearful and wonderful audacity.

Even then, however, she originates no fantasy of her own, but simply elaborates and enlarges upon the primary copy. Her impulse is not to think and create, but to observe and assimilate. It would never occur to her to study the lines of her head and arrange her hair accordingly; rather she studies the head of her next-door neighbour, and promptly duplicates it—generally with distinct improvement over the original. True to her race, she has a genius for imitation that will not be subdued. But she is not an artist.

For this reason, the American woman bores us with her vanity, where the Englishwoman rouses our tenderness, and the Frenchwoman piques and allures. There is an appealing clumsiness in the way the Englishwoman goes about adding her little touches of feminine adornment; the badly tied bow, the awkward bit of lace, making their deprecating bid for favour. The Frenchwoman, with her seductive devices of alternate concealment and daring displays, lays constant emphasis on the two outstanding charms of all femininity: mystery and change. But when we come to the American woman we are confronted with that most depressing of personalities, the stereotyped. She has made of herself a mannequin for the exposition of expensive clothes, costly jewels, and a mass of futile accessories that neither in themselves nor as pointers to an individuality signify anything whatsoever. This47 figure of set elegance she has overlaid with a determined animation that is never allowed to flag, but keeps the puppet in an incessant state of laughing, smiling, chattering—motion of one sort or another—till we long for the machinery to run down, and the show to be ended.

But this never occurs, except when the entire elaborate mechanism falls to pieces with a crash; and the woman becomes that wretched, sexless thing—a nervous wreck. Till then, to use her own favourite expression, “she will go till she drops,” and the onlooker is forced to watch her in the unattractive process.

Of course the motive of this excessive activity on the part of American men and women alike is the passionate wish to appear young. As in the extreme East age is worshipped, here in the extreme West youth constitutes a religion, of which young women are the high priestesses. Far from moving steadily on to a climax in ripe maturity, life for the American girl reaches its dazzling apex when she is eighteen or twenty; this, she is constantly told by parents, teachers and friends, is the golden period of her existence. She is urged to make the most of every precious minute; and everything and everybody must be sacrificed in helping her to do it.

As a matter of course, she is given the most comfortable room in the house, the prettiest clothes, the best seat at the theatre. As a matter of course, she accepts them. Why should it occur to her to defer to age, when age anxiously and at every turn defers48 to her? Oneself as the pivot of existence is far more interesting than any other creature; and it is all so brief. Soon will come marriage, with its tiresome responsibilities, its liberty curtailed, and children, the forerunners of awful middle age. Laugh, dance, and amuse yourself today is the eternal warning in the ears of the American girl; for tomorrow you will be on the shelf, and another generation will have come into your kingdom.

The young lady is not slow to hear the call—or to follow it. With feverish haste, she seizes her prerogative of queen of the moment, and demands the satisfaction of her every caprice. Her tastes and desires regulate the diversion and education of the community. What she favours succeeds; what she frowns on fails. A famous American actress told me that she traced her fortune to her popularity with young girls. “I never snub them,” she said; “when they write me silly letters, I answer them. I guard my reputation to the point of prudishness, so that I may meet them socially, and invite them to my home. They are the talisman of my career. It matters little what I play—if the young girls like me, I have a success.”

The wise theatrical manager, however, is differently minded. He, too, has his harvests to reap from the approval of Miss New York, Jr., and arranges his program accordingly. Thus the American play-goer is treated to a series of musical comedies, full of smart slang scrappily composed round a hybrid waltz; so-called “society plays,” stocked with sumptuous49 clothes, many servants, and shallow dialogue; unrecognizable “adapted” pieces, expurgated not only of the risqué, but of all wit and local atmosphere as well; and finally the magnificently vacuous extravaganza: this syrup and mush is regularly served to the theatre-going public, and labelled “drama”! Yet thousands of grown men and women meekly swallow it—even come to prefer it—because Mademoiselle Miss so decrees.

She also is originally responsible for the multitude of “society novels,” vapid short stories, and profusely illustrated gift books, which make up the literature of modern America. On her altar is the vulgar “Girl Calendar,” the still more vulgar poster; flaunting her self-conscious prettiness from every shop window, every subway and elevated book-stall. She is displayed to us with dogs, with cats, in the country, in town, getting into motors, getting out of boats, driving a four-in-hand, or again a vacuum cleaner—for she is indispensable to the advertising agent. Her fixed good looks and studied poses have invaded the Continent; and even in Spain, in the sleepy old town of Toledo, among the grave prints of Velasquez and Ribera, I came across the familiar pert silhouette with its worshipping-male counterpart, and read the familiar title: “At the Opera.”

From all this superficial self-importance, whether of her own or her elders’ making, one might easily write the American girl down as a vain, empty-headed nonentity, not worth thoughtful consideration. On the contrary, she decidedly is worth it. Behind her50 arrogance and foolish affectations is a mind alert to stimulus, a heart generous and warm to respond, a spirit brave and resourceful. It takes adversity to prove the true quality of this girl, for then her arrogance becomes high determination; her absurdities fall from her, like the cheap cloak they are, and she takes her natural place in the world as a courageous, clear-sighted woman.

I believe that among the working girls is to be found the finest and most distinct type of American woman. This sounds a sweeping statement, and one difficult to substantiate; but let us examine it. Whence are the working girls of New York recruited? From the families of immigrants, you guess at once. Only a very small fraction. The great majority come from American homes, in the North, South, or Middle West, where the fathers have failed in business, or died, or in some other way left the daughters to provide for themselves.

The first impulse, on the part of the latter, is to go to New York. If you are going to hang yourself, choose a big tree, says the Talmud; and Americans have written it into their copy-books forever. Whether they are to succeed or fail, they wish to do it in the biggest place, on the biggest scale they can achieve. The girl who has to earn her living, therefore, establishes herself in New York. And then begins the struggle that is the same for women the world over, but which the American girl meets with a sturdiness and obstinate ambition all her own.

She may have been the pampered darling of a51 mansion with ten servants; stoutly now she takes up her abode in a “third floor back,” and becomes her own laundress. For it is part of all the contradictions of which she is the unit that, while the most recklessly extravagant, she is also, when occasion demands, the most practical and saving of women. Her scant six or seven dollars a week are carefully portioned out to yield the utmost value on every penny. She walks to and from her work, thus saving ten cents and doing benefit to her complexion at the same time in the tingling New York air. In the shop or office she is quiet, competent, marvellously quick to seize and assimilate the details of a business which two months ago she had never heard of. Without apparent effort, she soon makes herself invaluable, and then comes the thrilling event of her first “raise.”

I am talking always of the American girl of good parentage and refinement, who is the average New York business girl; not of the gum-chewing, haughty misses of stupendous pompadour and impertinence, who condescend to wait on one in the cheaper shops. The average girl is sinned against rather than sinning, in the matter of impudence. Often of remarkable prettiness, and always of neat and attractive appearance, she has not only the usual masculine advances to contend with, but also the liberties of that inter-sex freedom peculiar to America. The Englishman or the European never outgrows his first rude sense of shock at the promiscuous contact between men and women, not only allowed, but taken as a matter of course in the new country. To see an52 employé, passing through a shop, touch a girl’s hand or pat her on the shoulder, while delivering some message or order, scandalizes the foreigner only less than the girl’s nonchalant acceptance of the familiarity.

But among these people there is none of the sex consciousness that pervades older civilizations. Boys and girls, instead of being strictly segregated from childhood, are brought up together in frank intimacy. Whether the result is more or less desirable, in the young man and young woman, the fact remains that the latter are quite without that sex sensitiveness which would make their mutual attitude impossible in any other country. If the girl in the shop resents the touch of the young employé, it is not because it is a man’s touch, but because it is (as she considers) the touch of an inferior. I know this to be true, from having watched young people in all classes of American society, and having observed the unvarying indifference with which these caresses are bestowed and received. Indeed it is slanderous to call them caresses; rather are they the playful motions of a lot of young puppies or kittens.

The American girl therefore is committing no breach of dignity when she allows herself to be touched by men who are her equals. But I have noticed time and again that the moment those trifling attentions take on the merest hint of the serious, she is on guard—and formidable. Having been trained all her life to take care of herself (and in this she is truly and admirably independent), without fuss or unnecessary words she proceeds to put her knowledge53 to practical demonstration. The following conversation, heard in an upper Avenue shop, is typical:

“Morning, Miss Dale. Say, but you’re looking some swell today—that waist’s a peach! (The young floor-walker lays an insinuating hand on Miss Dale’s sleeve.) How’d you like to take in a show tonight?”

“Thank you, I’m busy tonight.”

“Well, then, tomorrow?”

“I’m busy tomorrow night, too.”

“Oh, all right, make it Friday—any night you say.”

Miss Dale leaves the gloves she has been sorting, to face the floor-walker squarely across the counter. “Look here, Mr. Barnes; since you can’t take a hint, I’ll give it you straight from the shoulder: you’re not my kind, and I’m not yours. And the sooner that’s understood between us, the better for both. Good morning.”

Here is none of the hesitating reserve of the English or French woman under the same circumstances, but a frank, downright declaration of fact; infinitely more convincing than the usual stumbling feminine excuses. It may be added that, while the American girl in a shop is generally a fine type of creature, the American man in a shop is generally inferior. Otherwise he would “get out and hustle for a bigger job.” His feminine colleagues realize this, and are apt to despise him in consequence. Certainly there is little of any over-intimacy between shop men and girls; and the demoralizing English system of “living-in” does not exist.

54