Transcriber’s Notes

Cover created by Transcriber and placed in the Public Domain.

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

IV

AMERICAN EXPLORERS SERIES

Early Steamboating on Missouri River

VOL. I.

LIFE AND ADVENTURES

OF

JOSEPH LA BARGE

PIONEER NAVIGATOR AND INDIAN TRADER

FOR FIFTY YEARS IDENTIFIED WITH THE COMMERCE OF THE

MISSOURI VALLEY

BY

HIRAM MARTIN CHITTENDEN

Captain Corps of Engineers, U. S. A.

Author of “American Fur Trade of the Far West,” “History

of the Yellowstone National Park,” etc.

WITH MAP AND ILLUSTRATIONS

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL. I.

NEW YORK

FRANCIS P. HARPER

1903

Copyright, 1903,

BY

FRANCIS P. HARPER.

Edition Limited

to 950 Copies.

TO

THE MEMORY

OF THE

Missouri River Pilot

| PAGE | |

| Preface, | xi |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Ancestry of Captain La Barge, | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Childhood and Youth, | 13 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Enters the Fur Trade, | 22 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Cholera on the “Yellowstone,” | 32 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Further Service at Cabanné’s, | 40 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Last Year at Cabanné’s, | 49 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Captain La Barge in “Opposition,” | 59 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Missouri River, | 73 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Kinds of Boats Used on the Missouri, | 90 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Steamboat Navigation on the Missouri River, | 115 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The Steamboat in the Fur Trade, | 133 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Voyage of 1843, | 141 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Voyage of 1844, | 154 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Changed Conditions, | 167 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Incidents on the River (1845–50), | 177 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Incidents on the River (1851–53), | 189 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Ice Break-up of 1856, | 200 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| The Head of Navigation Reached, | 216 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Fort Benton, | 222 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Abraham Lincoln on the Missouri, | 240 |

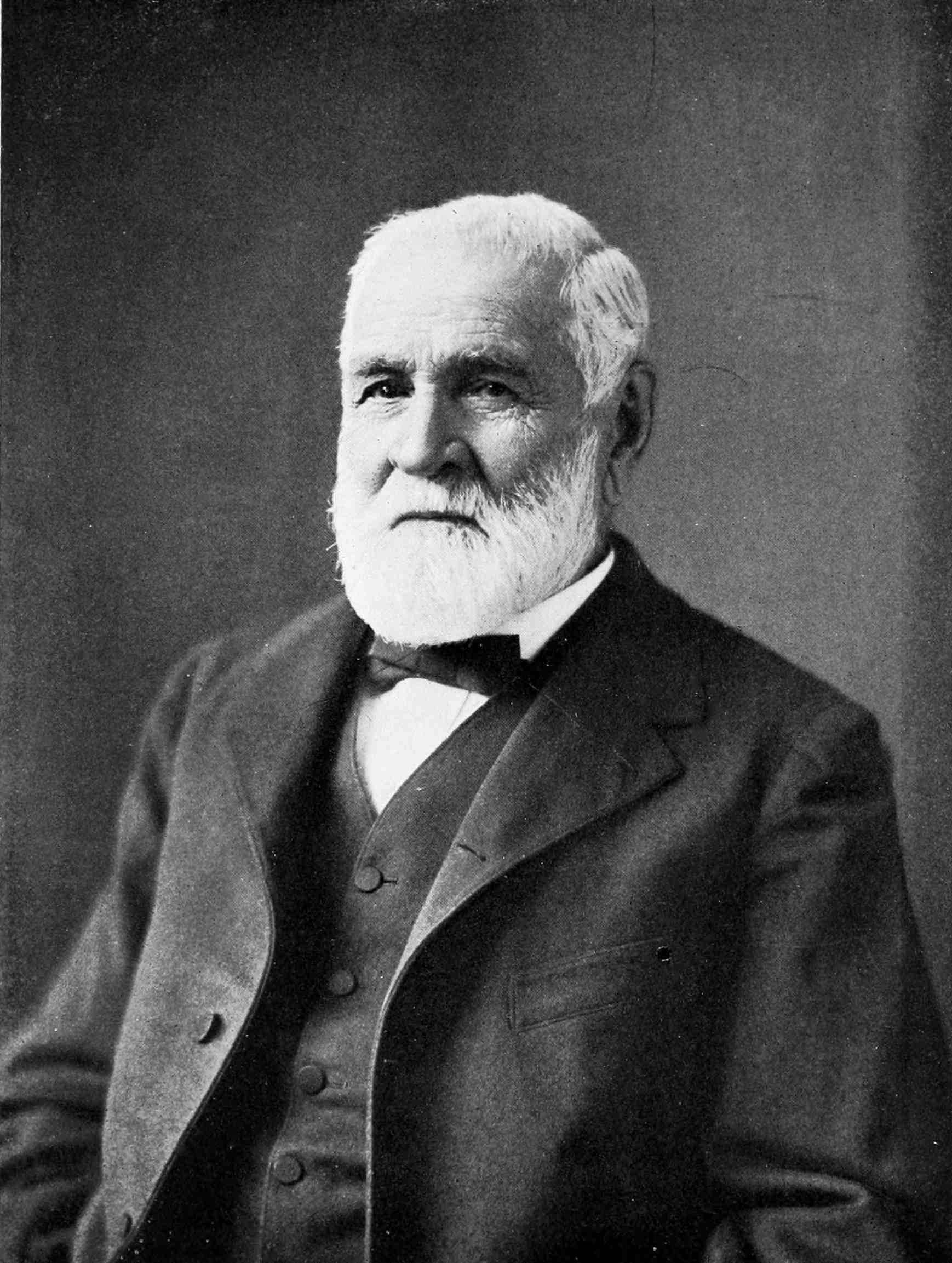

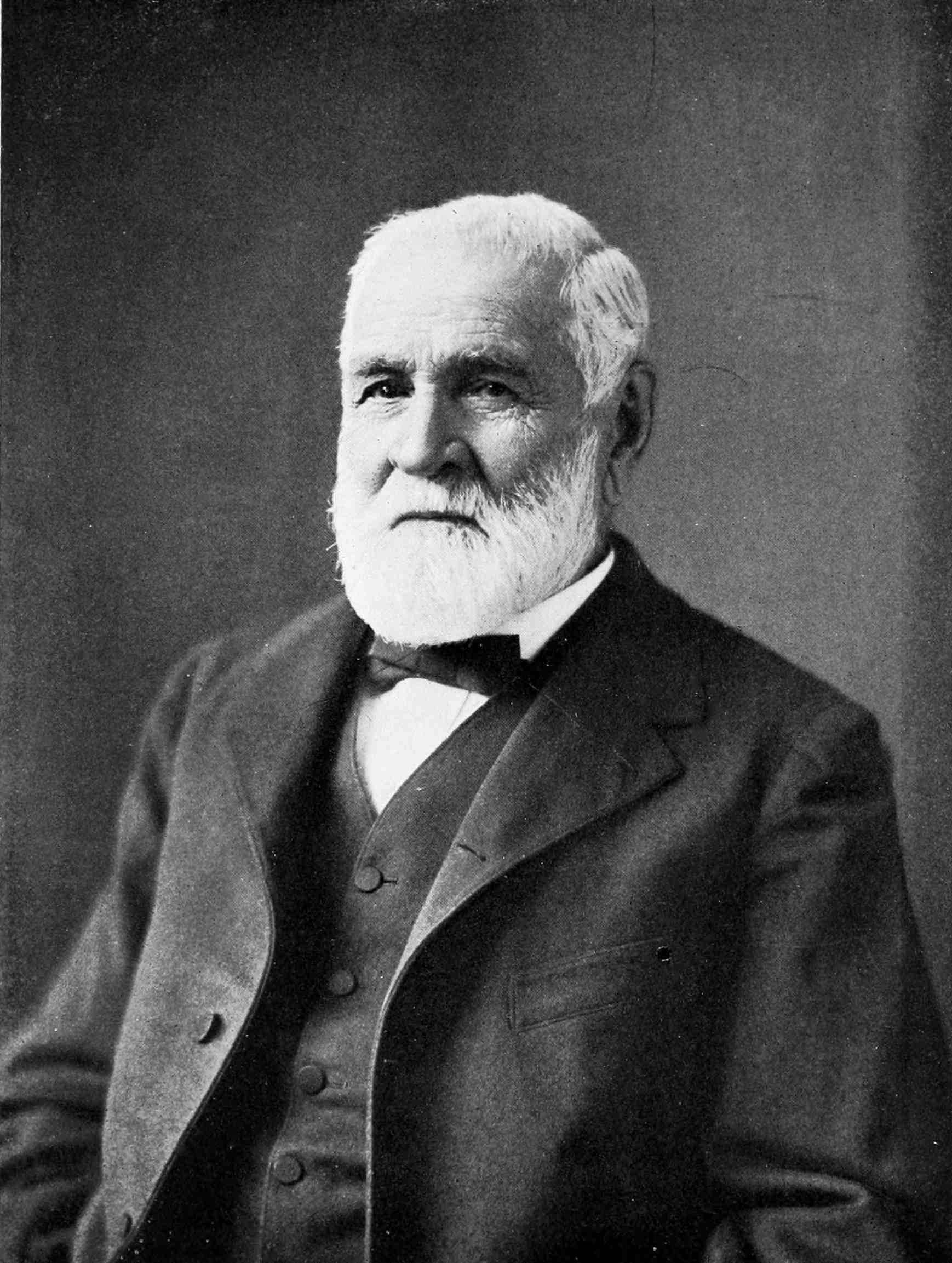

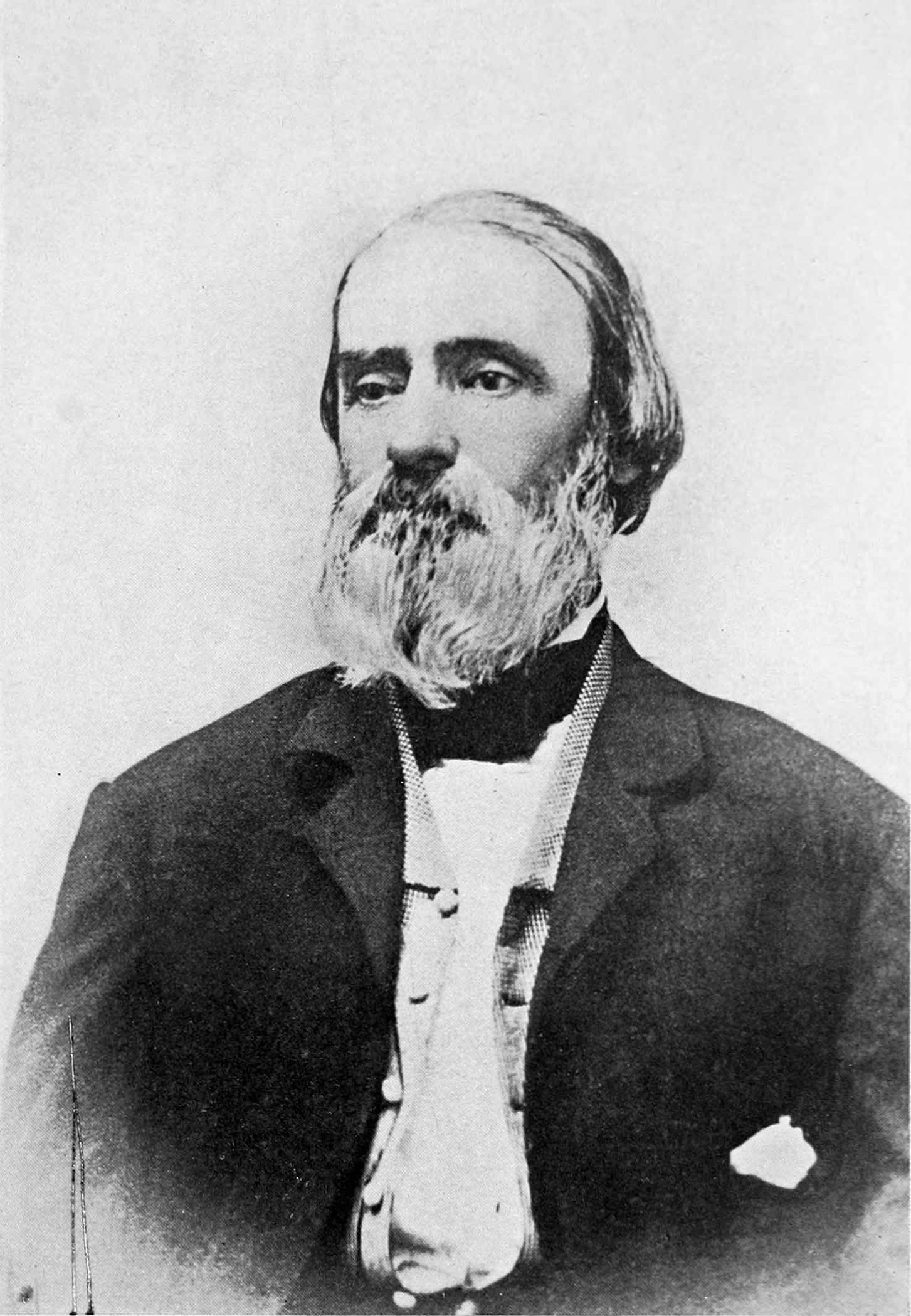

| Captain Joseph La Barge, | Frontispiece |

| Facing page | |

| Captain Joseph La Barge (when young), | 1 |

| A New “Cut-off” in the River, | 77 |

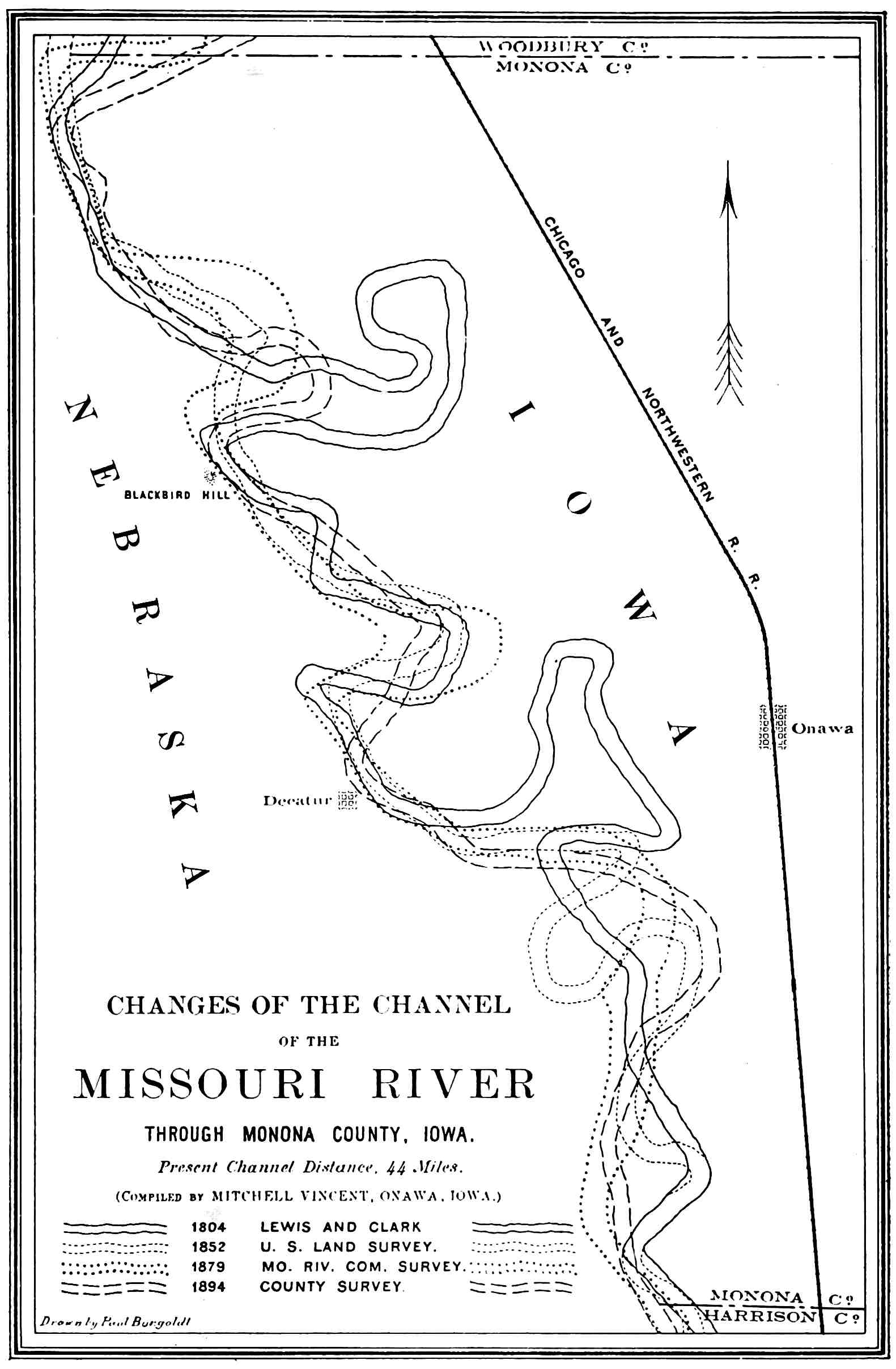

| Map of the Missouri River Channel, | 79 |

| Snags in the Missouri River, | 80 |

| The Indian Bullboat, | 97 |

| Missouri River Keelboat, | 102 |

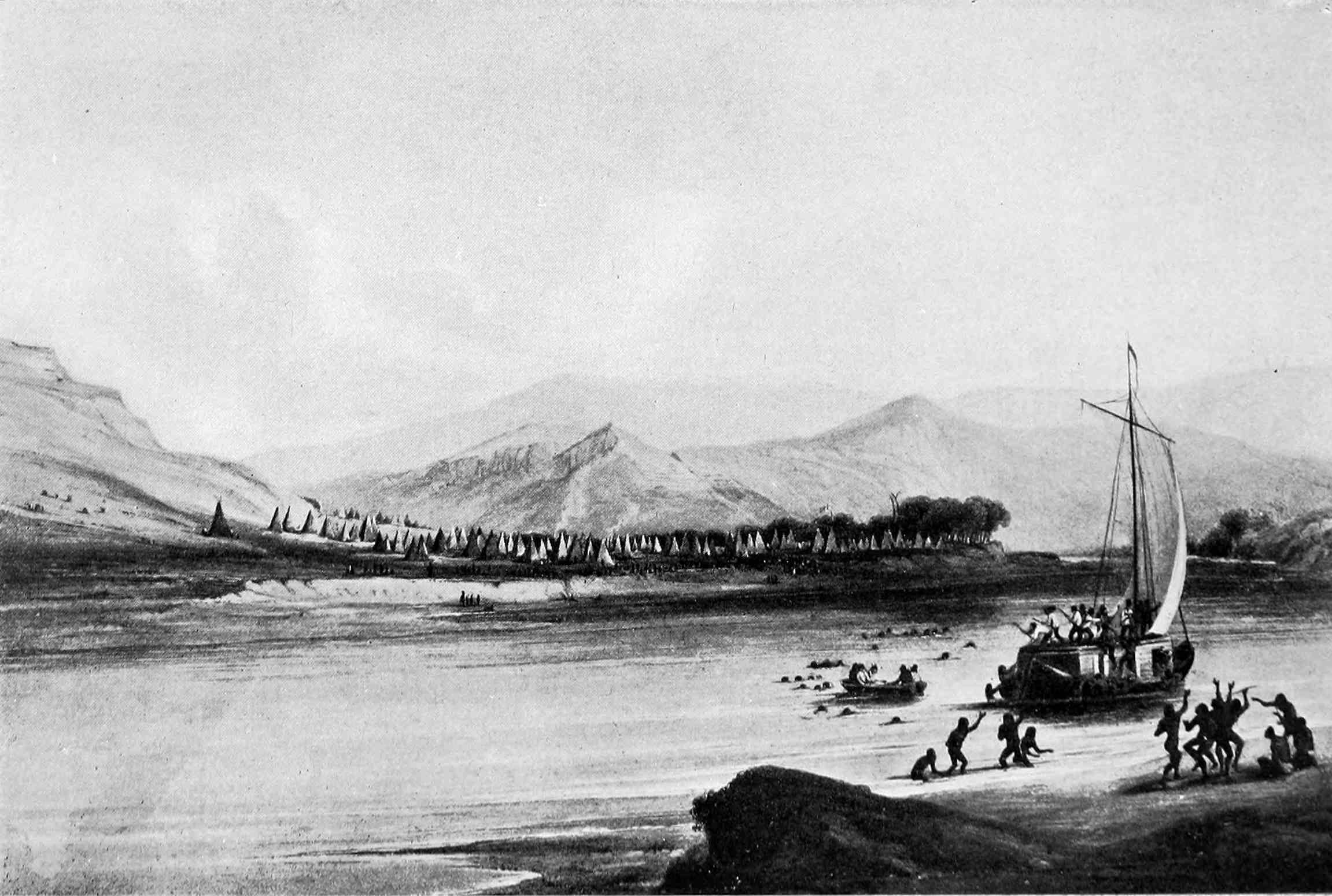

| The First “Yellowstone,” | 137 |

| Alexander Culbertson, | 228 |

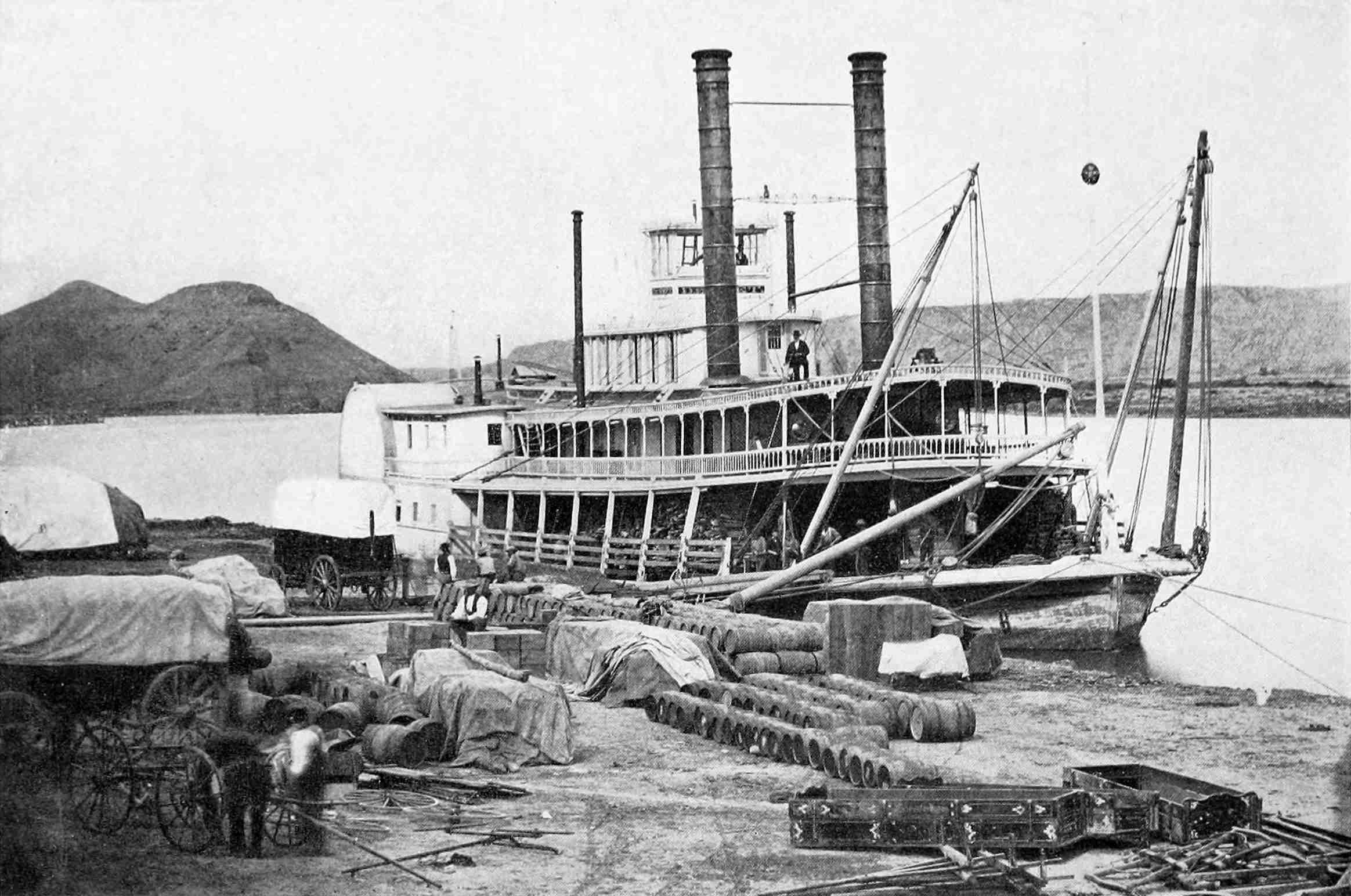

| Fort Benton Levee, | 238 |

xi

In the summer of 1896 the author of this work, while engaged in collecting data for a history of the American Fur Trade of the Far West, met the venerable Missouri River pilot, Captain Joseph La Barge, at his home in St. Louis. In the course of several interviews he became deeply impressed with the range and accuracy of the old gentleman’s knowledge of early Western history, and asked him if he had ever taken any steps to preserve the record of his adventurous career. He replied that he had often been urged to do so, but that lack of familiarity with that kind of work had hitherto caused him to shrink from it, and he presumed he should die without ever undertaking it. Believing that his memoirs were well worth preserving, as a part of the history of the West, the author proposed to prepare them for publication if he would consent to dictate them. After some hesitation he concluded to try it, and the work was forthwith begun. Full notes were taken in the rough, and a clean copy was then submitted to Captain La Barge for revision. He went through the whole with painstaking care, and the record was left as complete as axii memory of extraordinary power could make it. The intention was, at the time, to put the notes into shape for publication at once; but the Spanish-American war interfered with the author’s part of the work, and before it could be resumed Captain La Barge died.

This event led to a material change in the plan of the work, and it was decided to make it, not merely a narrative of personal experiences, but a history of steamboat navigation on the Missouri River. Very few people now have any conception of the part which this remarkable business played in the upbuilding of the West. There is no railroad system in the United States to-day whose importance to its tributary country is relatively greater than was that of the Missouri River to the trans-Mississippi territory in the first seventy-five years of the nineteenth century. The business of the fur trade, the intercourse of government agents with the Indians, the campaigns of the army throughout the valley, and the wild rush of gold-seekers to the mountains, all depended, in greater or less degree, upon the Missouri River as a line of transportation.

It is not alone from a commercial point of view that the record of this business is an important one. From beginning to end it abounds in thrilling incident, and the life which it fostered was full of picturesque and even tragic details. The circumstances surroundingxiii a voyage up or down the Missouri, whether by canoe, mackinaw, keelboat, or steamboat, were quite out of the line of ordinary experience. No other river in this country has a record to compare with it.

Captain La Barge’s life embraced the entire era of active boating business on the river. He saw it all—from the time when the Creole and Canadian voyageurs cordelled their keelboats up the refractory stream to the time when the railroad won its final victory over the steamboat. He was on the first boat that went to the far upper river, and he made the last through voyage from St. Louis to Fort Benton. He typified in his own career the meteoric rise and fall of that peculiar business. He grew up with it, prospered with it, and was ruined with and by it. He saw and shared the wonderful metamorphosis that came over the Missouri Valley in the space of fourscore years, and his reminiscences are a succession of living pictures taken all along the line.

It is hoped that the method adopted, of weaving the story which it is here attempted to relate around the biography of its most distinguished personality, will not detract from its value as historical material. It is not the bare narration of events that gives history its true value, but those intimate pictures of human life in other times that show what people really did and the motives by which they were actuated. To thisxiv end, biography, and even fiction, possess distinct advantages over the ordinary method of historical writing.

In the preparation of this work valuable personal aid has been received from many sources, particularly from the Hon. Phil E. Chappelle of Kansas City, Mo.; Messrs. N. P. Langford and J. B. Hubbell of St. Paul, Minn.; Hon. Wilbur F. Sanders of Helena, Mont.; and General Grenville M. Dodge of New York City.

CAPTAIN JOSEPH LA BARGE

(When a young man)

1

In the far-reaching operations of the French Government upon the continent of America, by which its western empire at one time embraced fully half of what is now the United States and Canada, two streams of colonization flowed inward from the sea. The course of one was along the valleys of the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes to the upper Mississippi and its tributaries. That of the other was along the lower Mississippi northward from the Gulf of Mexico. The two streams met at the mouth of the Missouri, where their blended currents were deflected westward toward the unknown regions of the setting sun. Near this place of meeting there arose, more than a decade before the birth of the American Republic, a village which has now become one of the greatest cities in the western world. Here, in the early days, the Canadians from the north and the2 Creoles from the south, kindred in language and tradition, mingled in common pursuits and enterprises, and for many years bore an important part in the great movement which proceeded onward from this common starting-point.

Among the well-known families identified with this movement was one whose ancestral line represented both the northern and the southern blood, and was a pure type of their united quality. This was the family of Captain Joseph La Barge, the subject of the present sketch. The father of Captain La Barge was a typical representative of the French peasantry of Quebec. His mother was a Creole descendant of both the Spanish and French elements in the settlement of the Mississippi Valley.

On the paternal side the ancestors of Captain La Barge came from Normandy, France. Robert Laberge was a native of Columbière in the diocese of Bayonne, and was born in 1633. He came to America early in life and settled in the county of Montmorency, below Quebec, where he was married in 1663. He is said to have been the only person of the name who ever emigrated to America. His descendants are now of the most numerous family in the district of Beauharnois, if not in the entire province of Quebec, where it has held important positions both in Church and State. Its ramifications in the3 United States have likewise become very extensive. The true spelling of the name was Laberge, and this form still prevails in Quebec; but the St. Louis branch of the family has for many years spelled the name in two words, La Barge.

Captain La Barge was of the sixth generation from his Norman ancestors. His father, Joseph Marie La Barge, was born at Assomption, Quebec, July 4, 1787.1 He emigrated to St. Louis about 1808, just as he was arriving of age. He traveled by the usual route, up the Ottawa River and through the intricate system of waterways in northern Ontario which leads to Georgian Bay and to Lake Huron. Thence he went by way of Mackinaw Strait and Lake Michigan to Green Bay, and along the Fox and Wisconsin rivers to the Mississippi, which he descended to St. Louis. He used a single birch-bark canoe all the way, with only eight miles of portaging.

The elder La Barge led a varied career in St. Louis, as did most of the pioneers in those days, when fixed callings were few and men turned their hands to whatever fell in their way. A good deal of information has survived concerning him, and all to his credit.4 He was evidently a man of good parts, of strict integrity, loyal in his business relations, and a bold lover of the adventurous life which characterized the early history of this new country.2

At the time when the Sac and Fox Indians were giving the government so much trouble, and endangering human life all along the upper Mississippi, La Barge senior was employed in the perilous business of carrying dispatches to Rock Island, having volunteered for this service when others refused to go. He served in the War of 1812, and was present in the battle of the River Raisin, or Frenchtown, January 22, 1813, and was there shot in the hand, losing two fingers. He also received a tomahawk wound on the head, and carried the scar through life. He became naturalized as a result of this service in the army. Although entitled to a pension under the laws of the United States, he never asked for nor received any.

La Barge married in 1813, and some two years5 afterward acquired a farm at Baden, a small village a few miles north of St. Louis, and now within the limits of that city. His main business here was the manufacture of charcoal, which he hauled to St. Louis for sale. He soon moved to town, where he had gained quite an extensive acquaintance, particularly among the Canadian voyageurs. Here he opened up a boarding-house, which developed into a regular hotel or tavern, with a livery attachment, at that time one of the most important in the city. It was while engaged in this business that he served the English traveler, James Stuart, already referred to.

La Barge senior was, to a considerable extent, identified with the early trapping business in the Far West, and has left his name on geographical features in widely separated localities. There is a La Barge or Battle Creek, a tributary of the Missouri, which took its name from some affair with the Indians in which La Barge bore a part; but the details are apparently lost. The same is true of La Barge Creek, a tributary of Green River in Wyoming, which was named before 1830. La Barge was present in General Ashley’s disastrous fight with the Aricara Indians on the Missouri River in 1823, and was the man who cut the cable of one of the keelboats so that it might drift out of range of the fire of the Indians.3

6

La Barge senior lived to a good old age, and was sound and healthy to the last. As a remarkable evidence of this, it was long remembered by his acquaintances that he practiced in old age his favorite winter pastime of skating. His death was the result of accident. He had heard that a brother-in-law, Joseph Hortiz, was ill, and he resolved to go to see him. It was a cold wintry day, and Captain La Barge tried to dissuade him, but to no purpose. He slipped on the icy sidewalk at the corner of Olive and Fourth streets, in St. Louis, struck the curb, and received injuries from which he died two days later, January 22, 1860.

Many interesting anecdotes of the elder La Barge have come down to us, some of which are worth relating as illustrating the character of the man in different situations. One of these comes from General Harney, who was long an intimate friend of Captain La Barge. In the later years of General Harney’s life, when physical ailments prevented his leaving the house, he used to send for Captain La Barge, if the latter happened to be derelict in his visits, to come and talk over old times. On one of these occasions, not long before his death, he gave the Captain the following story:

“Your father,” he said, “was the only man who ever scared me. We were ascending the Missouri River on a keelboat laden with troops and supplies,7 he in charge of the boat, and I, a lieutenant, on duty with the soldiers. In one place the boat had to round a sharp point, where there was an accumulation of driftwood. The current was very strong, and it required the utmost efforts of the men to stem it. When we reached the most difficult place, the Captain stimulated his men by calling out to them (in the French language), ‘Hale fort! Hale fort!’ (‘Pull hard! Pull hard!’). I didn’t understand French, but thought I detected in the Captain’s language something like the military command, ‘Halt.’ As some of the troops were on the line with the voyageurs, and as they might not understand, I thought I could help the Captain by repeating to them his command. This created some confusion, for my men began to slacken while the Captain’s were pulling harder than ever. Again he commanded, ‘Hale fort!’ and again I called to the men to halt. The situation was extremely critical when the Captain thundered a third time, ‘Hale fort!’ in a voice and manner not to be misunderstood. The men all bent to the line and finally extricated the boat from its perilous position. The Captain then came over to where I was standing and told me that if I ever dared interfere again with his management of the boat he would pitch me into the river. I knew he meant what he said, and thereafter confined myself to my military duties.”

8

One fine morning in the early twenties a man called at the house of Mr. La Barge, who met him at the door and asked him what he wanted. The man said: “I applied to you a short time since for employment, having heard that you were hiring men for the Ashley Expedition.4 I was refused, and I would like to know the reason.”

“Simply because you did not suit,” replied La Barge.

“I am as good a man as you are or any you have employed, and I take the liberty of telling you so,” rejoined the six-footer.

“I want no trouble,” replied La Barge, “and therefore will request you to get out, or I will be compelled to put you out.”

“Just what I want you to undertake,” was the retort. Scarcely were the words out of his mouth when La Barge seized a rawhide riding whip and started for the fellow and laid him about the back and shoulders so vigorously that the man soon gave up the contest and took to his heels.

The next morning a constable came and arrested La Barge on the charge of assault and battery, with directions to bring him at once before Esquire Garnier, Justice of the Peace.

9

“Lead the way, and I will follow,” said La Barge, taking down his rawhide and starting along with the constable. La Barge told the people he met on the way to come and see the fun. In due course the trial came off and La Barge was fined four dollars. He thanked the Justice, but handed him eight dollars, saying that the fun was cheap at that price, and he would give the fellow another dose. He then seized his whip and started for him, chasing him out into the street, where he gave him a second drubbing, to the great delight of the crowd, who stood around shouting and setting him on.

Another incident, which occurred late in life, exhibits the sterling integrity of the man who could withstand the temptations of wealth rather than do the smallest act of injustice. About the time that the elder La Barge was married he purchased from Joseph Morin, for the sum of twenty-five dollars, a small tract of land on Cedar Street, between Second and Third. Land was then of very little value, and transfers were often made without deed and with no more formality than in exchanging cattle or horses. In this way La Barge traded off his lot on Cedar Street to Chauvin Lebeau for a horse, with which he moved to his Baden farm, only recently purchased. Here, as already narrated, he manufactured charcoal and hauled it to town, where he sold it to Theodore Bosseron and Vilrais10 Papin, then the principal blacksmiths of the village. Long years afterward, when these transactions were almost forgotten, and the property had become very valuable, a lawyer presented himself to the old gentleman and asked him if he had ever owned any property on Cedar Street. La Barge replied in the affirmative and described its locality. The lawyer then asked him when and how he disposed of it. He could not at first recall, but Mrs. La Barge remembered the circumstances and related them to the lawyer, at the same time remarking to her husband that that was the way they got their horse to set themselves up on the farm with. The lawyer then assured La Barge that the title to this property was still in him, and that he could hold it against all comers, for there was absolutely no record of the conveyance in existence. The old gentleman, with a look of indignation, asked the lawyer if he took him for a thief. “I traded that land,” said he, “to Chauvin Lebeau for a horse, which was worth more to me then than the land was. I shall stand by the bargain now. If Chauvin Lebeau’s heirs have no title, tell them to come to me and I will make them a deed before I die.”

Such are some of the glimpses we still have through the mists of time of the father of Captain La Barge.

On the maternal side he was likewise descended from11 creditable ancestry. Among the early mechanics in the village of Fort de Chartres, near the mouth of the Ohio River, when to be a mechanic was to be a leading citizen, were Gabriel Dodier and Jean Baptiste Becquet, blacksmiths. The younger of these two men, Becquet, married the daughter of the other. They had three children, the eldest being a daughter, Marguerite Marianne. On the 27th of January, 1780, this daughter was married to Joseph Alvarez Hortiz, who was the son of François Alvarez and Bernada Hortiz, and was born in the town of Lienira, in the Province of Estremadura, Spain, in the year 1753. Alvarez was a private soldier in the military service of Spain, and came to St. Louis after Spanish authority had been established there in 1770. He attained the rank of sergeant, and being a man of some education, was for several years detailed as military attaché to the Governor. He finally became Secretary to the last two Spanish Governors, Trudeau and Delassus, and had charge of the public archives down to 1804. He had nine children, of whom the eighth was a daughter, of the name of Eulalie. This daughter was married to Joseph Marie La Barge in St. Louis, August 13, 1813.

The parents of Captain La Barge thus represented the best traditions of French and Spanish occupancy of the Mississippi Valley. Their marriage took place after their country had become American territory,12 and their offspring, the subject of our present inquiries, was born an American citizen.5

13

Joseph La Barge, son of Joseph Marie La Barge and Eulalie Hortiz, was born in St. Louis, October 1, 1815. He was the second child in a family of seven children, three boys and four girls, who all grew to adult years. The two brothers were Charles S., who was killed in a steamboat explosion in 1852, and John B., who dropped dead at the wheel in 1885 while making a steamboat landing at Bismarck, N. D.

Soon after the birth of Captain La Barge the parents moved to the newly acquired farm in Baden. There is but one incident relating to the young child while living here that need detain us. Although this place was distant only six miles from where the courthouse of St. Louis now stands, it was at that time unsettled and uncleared, and Indians not infrequently roamed in the vicinity. The Sac and Fox tribes were particularly troublesome, and many were the outrages which they committed upon the isolated settlement. The incident in question occurred one day just before the father had started on his usual trip to town. He was14 loading his cart at some distance from the garden, where Mrs. La Barge had gone to dig some potatoes to send to her mother in the village. Housewives in those days seldom enjoyed the luxury of nurses, and Mrs. La Barge was obliged to carry her child with her into the garden. Depositing him between the rows of potatoes, she was proceeding with her work, when suddenly the house dog set up a cry of alarm. Looking up, Mrs. La Barge was horrified to see an Indian approaching. She uttered a scream and started for the house, forgetting in the suddenness of her alarm the baby in the garden. Meanwhile the father had heard the dog’s bark and his wife’s screams, and hastened to see what was the matter. His first question was about the baby, and Mrs. La Barge, more terrified than ever, rushed back to where she had left him. Fortunately the dog had held the Indian at bay, and when the father arrived, gun in hand, he beat a prompt retreat. Captain La Barge’s father often reminded him of this incident in after years, predicting that he would always escape harm from the Indians, for they had had their opportunity and had failed. In his many experiences with the Indians throughout a life spent in their country, he never suffered personal injury at their hands, and came to have faith in his father’s prediction.

Captain La Barge was not yet two years old when15 the first steamboat came to St. Louis, nor four when the first one entered the Missouri River. It is said that his father used to take him to the river bank to see these early boats, and that they always had a great attraction for his youthful fancy. To be a steamboat master was his ambition, and he spent much of his time as a child in drawing boats and making models, and thus unwittingly training himself for his after career.

The boy was a leader among his fellows, and an expert in all youthful games practiced at the time. In contests of skill among the boys of the village each side was anxious to secure Joe La Barge. “He could jump higher,” says one authority, “run faster, and swim farther than any other lad in the town.”

Among the noteworthy events of Captain La Barge’s childhood, the memory of which clung by him even in old age, was the visit of Lafayette to St. Louis in 1825. This venerable patriot, whom, next to Washington, Americans in that day delighted to honor, arrived in St. Louis on board the steamer Natchez, at 9 A. M., May 29. He was met at the wharf by a committee of leading citizens, and an address of welcome was made by the Mayor, to which Lafayette responded. He then entered a carriage with the Mayor and Mr. Auguste Chouteau and Stephen Hempstead, a soldier of the Revolution, and was driven to16 the house of Mr. Pierre Chouteau, Sr., which had been prepared for his reception. He was escorted by a company of light horsemen, and also by a company of uniformed boys, of whom Captain La Barge, then ten years old, was one. The Captain always remembered the venerable appearance of the General and his review of the youthful troop. He shook hands with them, indulged in the pleasant questions which age delights to ask of youth, and doubtless himself took a keen pleasure in the incident, because most of his youthful auditors could reply in his own tongue.6

An interesting sequel of Lafayette’s visit to St. Louis occurred in that city in 1881, on the occasion of17 the visit of Lafayette’s grandson with General Boulanger and party, who had come to America to attend the centennial celebration of the surrender of Yorktown. Captain La Barge was sent for, to meet the distinguished company at the Merchants’ Exchange. When introduced to the members of the party, the grandson of Lafayette came forward, and taking La Barge by both hands, looked at him a moment and said: “You have seen one whom I wish it were my lot to have seen, and that is my revered grandfather.” He cordially urged the Captain to come to his home if he should ever visit France, and in other ways showed an almost affectionate interest in this individual who had once, though but a boy, beheld the face of his distinguished ancestor.

Captain La Barge’s schooling was necessarily very limited, for the educational facilities of St. Louis in those days were of a truly primitive order. He first went to a schoolmaster of considerable local renown, Jean Baptiste Trudeau, at the latter’s private residence on Pine Street, between Main and Second. Here he studied the common branches, all in French. He went for a time to Salmon Giddings, founder of the First Presbyterian Church, in St. Louis, and later to a more pretentious school kept by Elihu H. Shephard, an excellent teacher. At both of these schools instruction was given in English. Captain La Barge’s18 parents foresaw that their native tongue could not long survive in common use, and felt it to be their duty to equip their son, so far as their slender means would permit, with the language of his country. The pupil found the task a tedious one, and was a long while in mastering it. He never forgot the almost insurmountable obstacle he found in the English “th.” He used his native language in common intercourse down to nearly 1850, and retained a fluent command of it to his death. He also acquired a very perfect command of English, in which there was no trace of foreign accent, but in which the mellowing influence of the softer tongue had produced a modulation of the voice that was very pleasant to listen to.

In 1819 there was established in Perry County, Mo., a Catholic School, St. Mary’s College. Young La Barge was sent there at the age of twelve, and remained three years. On their way to the college himself and father traveled by the steamer Tuscumbia. It was Captain La Barge’s first ride in a kind of boat with which most of his after life was to be connected. The desire of the young man’s parents was to educate their son for the priesthood, and his course at college was shaped somewhat to that end. But the boy did not fall in with their plans, as his tastes ran in a different direction. He did not finish the course, for his career at the school was summarily cut short by a19 delinquency which is the only one we have to record in a life of more than fourscore years. He became involved in intrigues with young women to an extent which barred him from a further continuation of his course.

Associated with him in this unfortunate episode was Edward Liguest Chouteau, a youth of about the same age as himself. The young men walked to St. Genevieve, on the Mississippi. Chouteau was without funds, and La Barge nearly so, having scarcely the amount of a single steamboat fare to St. Louis. They found the De Witt Clinton at the bank on her way up the river. La Barge told the captain of the boat the straight story of their misfortune: that they had only enough money for a single fare to St. Louis, and would have to walk unless they could make some arrangement with him. He laughed, and told them to get on board and he would see them home. This incident, in which the two young men were companions in misfortune, was not forgotten by either, and we shall have occasion to refer to it again in the course of this narrative.

After La Barge left college his father placed him in the office of John Bent, a leading lawyer of St. Louis, and one of the noted Bent brothers. He soon became disgusted with his new situation on account of his preceptor’s habit of excessive drink. He then went20 into a clothing store, and after remaining about a year, left that.

The restless ambition of the young man was now directed toward a kind of life which, in every portion of the country, has filled up the period between discovery and settlement—the business of the fur trade. At this particular time it was the only business carried on in the trans-Mississippi territory beyond the few scattering settlements along the lower Missouri. Large parties of hunters and trappers remained constantly in the wilderness, wandering all over those vast regions in quest of beaver and other fur. Each spring expeditions set out for various points in the Far West from Santa Fe to the British boundary, carrying supplies and recruits and bringing back the furs collected during the previous year. The great bulk of this business was done along the Missouri River, where trading posts were established throughout the entire valley. The annual journeys to these posts were always made by water. In the keelboat days they consumed an entire summer, but after the steamboat came they were completed by the middle of July.

From its very nature this business was one of adventure and excitement, and particularly attractive to those who were fond of an independent and out-of-door life. We can but faintly imagine at this day how strong was the attraction for youth in this wild life.21 Now it is considered a great piece of good luck for a boy to get on a common surveying party in the mountains, where he may see something of the wildness of nature, and perhaps catch sight of some surviving specimens of the larger game. In those days a trip to the mountains meant adventure of the genuine sort—absence from civilization, ever-present danger from the Indians, game of all kinds in abundance, and the grandeur and beauty of nature in a region still unknown except to a very few.

Being now at the impressionable age of sixteen, young La Barge became infatuated with the tales of adventure related by those who came back every year from the distant mountains. He told his father that, for the present, his mind was made up. He would join one of the fur-trade expeditions and see something of the Indian country. This decision met a responsive chord in the adventurous nature of the father, who said he had no objection if the mother were willing. The matter was laid before her, and after much entreaty and expostulation, her consent was secured. This was in the year 1831.

22

Captain La Barge did not immediately find an opportunity to visit the Indian country. The annual expeditions for the year had all gone. The Yellowstone was already far away on her historic first trip up the Missouri for the American Fur Company, and nothing was left for the impatient youth but to await a later opportunity. When the Yellowstone returned from her voyage, she was sent down the Mississippi to pass the time until the following spring in the Bayou la Fourche sugar trade. La Barge was engaged as second clerk on this voyage and found himself in constant demand as interpreter during the winter. The people of the Bayou la Fourche district spoke only French, which most of the officers of the boat did not understand. La Barge, who knew both French and English well, was of great use in carrying on the trade.

In the spring of 1832 the Yellowstone returned to St. Louis to prepare for her second voyage up the Missouri. This boat had been built as an experiment,23 to determine if it would be practicable to substitute steamboats for keelboats in the trade of the upper river. In the summer of 1831 she had gone as far as Fort Tecumseh, which stood on the opposite shore from the present capital of South Dakota. It was now proposed to take her as far as the mouth of the Yellowstone. The attempt was completely successful, and the voyage has ever since been considered one of the landmarks of the early history of the West.

Although La Barge was only in his seventeenth year he signed a contract binding himself to the service of the American Fur Company, as voyageur, engagé, or clerk, for a period of three years, at a salary of seven hundred dollars for the whole time.7 He did not go as part of the boat’s crew, but as an employee of one of the posts. No place was specified in his engagement, but his assignment was left to the bourgeois of the different posts, who came down to the boat when it arrived, looked over the new engagés, and selected such as they thought would suit them. Young La Barge was a promising-looking lad, and did not get above Council Bluffs, where he was taken off and put to work at Cabanné’s post, a few miles above the modern city of Omaha.

24

When the Yellowstone returned from Fort Union, John P. Cabanné, the bourgeois in charge of the post, went down to St. Louis and took La Barge with him. While waiting to return to the upper country the young engagé took temporary service on the steamboat Warrior, Captain Throckmorton, bound for the seat of the Blackhawk, or Sac and Fox, war. She was loaded with government stores for Prairie du Chien, and La Barge went along in some subordinate capacity. It happened that she arrived at the scene of the Battle of Bad Axe just as that decisive conflict was going on. Captain Throckmorton saw a number of Indians trying to make their escape by swimming the river and he fired into them, killing several. They proved to be all women, and the over-zealous captain long had reason to regret his hasty action. After this adventure the Warrior returned to St. Louis.

When Cabanné went back to his post at the Council Bluffs young La Barge went with him to commence in earnest his life in the Indian country. His initiation into the business of the fur trade was such as to leave a lasting impression on his mind. He had not been at Cabanné’s post very long when he had a lively experience of the evils of competition in that business, and of the extreme measures to which unrestrained rivalry sometimes led. Narcisse Leclerc, at one time25 an employee of the American Fur Company, had saved a little means, which certain parties in St. Louis eked out to a respectable sum, and he resolved to go into the trading business on his own and their account. Under the style of the Northwest Fur Company he carried on a prosperous trade in a small way for two or three seasons. The American Fur Company, jealous of all opposition, always treated these petty rivals with the utmost severity, and, if possible, crushed them by sheer force. When it could not do this it bought them out. Leclerc, who was a shrewd fellow, and as unscrupulous as any of the company’s agents, had developed staying qualities which caused the company a good deal of uneasiness. He went up the river in the autumn of 1832 with a larger outfit than ever, and the company determined that something must be done to arrest his career. The problem was left for Cabanné to solve, and he was given authority, as a last resort, to offer Leclerc outright a thousand dollars if he would not carry his trade up the river beyond a specified point.

Circumstances, however, threw in Cabanné’s way what he considered a better means of dealing with Leclerc. Congress had lately passed a law prohibiting the importation of liquor into the Indian country. Cabanné found out in some way that Leclerc had smuggled a considerable quantity past the military authorities26 at Leavenworth. Here was his opportunity. He would stop the expedition, and confiscate the property on the ground that Leclerc was violating the law of the land. It did not seem to occur to him that the enforcement of the law is intrusted to duly constituted officials, and that he, not being one of these, could not legally do more than inform against Leclerc. He did not trouble himself about fine distinctions of that sort. Exultantly he wrote to the house in St. Louis: “Have no fear; leave the matter to me, and I will make our incapable adversary bite the dust.”

Cabanné laid his plans well for the capture of Leclerc’s outfit. As soon as the boat passed his post he organized a party under charge of Peter A. Sarpy, clerk at the post, to go and arrest Leclerc. Sarpy picked out about a dozen men, among whom was the new engagé, La Barge. They were all well armed and carried besides a small cannon. Going to a point near old Fort Lisa, where the channel of the river came in close to a high impending bank, Sarpy stationed his men there and awaited Leclerc’s arrival. At the proper time, when the voyageurs were cordelling the boat along a sandbar just opposite, scarcely a hundred yards off, he ordered Leclerc’s party to surrender or he would “blow everything out of the water.” Although Leclerc had some thirty men, they were mostly unarmed, and could make no effective27 resistance. They surrendered, and the whole outfit returned to Cabanné’s post, where the liquor was confiscated and the expedition broken up.

This drastic measure came near proving fatal to the company’s business upon the river. Leclerc immediately returned to St. Louis, where he began suit against the company and lodged a criminal complaint against Cabanné. The matter bore a very serious aspect for a time. It was with the utmost difficulty, and with an evident resort to misrepresentation, that the company’s license was saved; and doubtless it would have been revoked but for the influence of Senator Thomas H. Benton. As it was, it cost the company a large sum of money, increased the public distrust of this powerful concern, and banished Cabanné, one of its most efficient servants, permanently from the country.

At Cabanné’s post La Barge was employed in the various duties of engagé, and was frequently sent out to surrounding bands of Indians with small outfits of merchandise to trade for their furs. His most interesting and valuable experience in this line was with the Pawnees, who resided on the Loup Fork of the Platte, about one hundred miles west of the Missouri. They were what are called permanent village Indians; that is, they had fixed villages made of large, strong houses, where they regularly lived; while many of the28 tribes, like the Sioux, Crows, and Blackfeet, lived only in tents, and were always moving from one place to another. The Pawnees, it is true, roved about a great deal on their hunting and war expeditions, but they had a fixed place of abode to which they always returned from their wanderings. Their houses were circular in form and quite large, being sometimes sixty feet in diameter, and, to judge from pictures of them, resembled in appearance, when seen from a distance, a group of oil tanks in a modern petroleum district.

Near to their villages the Pawnees cultivated extensive fields of maize or Indian corn. After the spring planting was over they generally went on long excursions to hunt buffalo, to make war, or to secure wood and other materials for the village. Their cornfields were left to shift for themselves during this period, and their enemies sometimes took advantage of this fact; but on the whole the latter were very cautious about what they did, for they knew that the wily Pawnee would learn who the robbers were and would not fail to exact full retribution. When the corn was ripe the Indians gathered it and remained in their villages a considerable part of the winter. Their business, however, compelled them at this season to make their hunts for robes and furs, which were salable only when taken during the cold weather. When the skins were brought into the villages the squaws took them,29 scraped them down, rubbed them with brains or pork, and otherwise manipulated them until they were soft and flexible and ready for the trade.

The custom of the traders was to send over from their posts near the old Council Bluffs one or more clerks, with a few men and the necessary merchandise, to reside in the villages until the trade was over. The clerk generally lived in the lodge of the principal chief, kept his goods there, and also such furs as were received in trade. After the season’s business was over the furs were loaded into bullboats, in which they were floated down the Loup and the Platte rivers to the Missouri. Here they were reshipped in large cargoes to St. Louis.

It was on a business of this kind that young La Barge spent his first winter in the Indian country—1832–33. His party consisted of four men, who, with the merchandise, were accommodated in the lodge of the chief Big Axe. Here they settled down to genuine Indian life—not half so uninteresting and repulsive as one might be disposed to think. The business of the trade, the ceremonials, the games and gambling, and the never-failing attractions of the gentler sex, which, one may easily believe, are as potent in the wilderness as in the city, all operated to make the time pass agreeably during the long and severe winters. The huts were very comfortable, and Captain30 La Barge always remembered them as the coolest habitations in summer and the warmest in winter of any that he had ever occupied. He noted as a remarkable peculiarity that mosquitoes never entered them.

During his winter sojourn among the Pawnees La Barge applied himself assiduously to learning their language. The interpreter would give him words and sentences in Pawnee and he would write them down and learn them. He practically mastered the language in the course of the winter, to the great astonishment of the natives and even of the whites. To the Indians the process of writing was a great curiosity, a “big medicine,” and when they saw young La Barge write down something and then read it off, they would put their hands to their mouths in their characteristic manner of expressing wonder.

There were numerous Indian scares during the winter, and Captain La Barge fully expected to see something of Indian warfare before he left the villages, but nothing of the sort actually occurred. In the spring of 1833, before he left for the Missouri, Major John Dougherty, Indian agent residing at Bellevue, about ten miles below the modern city of Omaha, arrived at the villages for the purpose of ransoming a female prisoner of the Crow nation, who had been sentenced to be burned at the stake. He prevailed,31 through Big Axe, chief of the Pawnee Loups, upon having her given up on payment of the ransom. He then started back with her to Bellevue, accompanied by an escort, until at a safe distance from the villages. When about ten miles on their way they were overtaken by a Pawnee chief, Spotted Horse, who came riding up at a gallop, and when opposite the woman, shot an arrow through her heart.

When the high water of spring arrived the furs were loaded into bullboats and shipped down to the mouth of the Platte. La Barge returned to Cabanné’s, and after a short time started for St. Louis with a fleet of mackinaw boats loaded with furs. He reached St. Louis in the latter part of May, 1833.

32

Before La Barge arrived in St. Louis the company had dispatched two boats to the upper river—the Yellowstone and the Assiniboine. The voyage of 1833 is particularly noteworthy as the one on which Prince Maximilian of Wied made his celebrated visit to the upper Missouri—a visit which has done more than any other one thing to preserve a true picture of those early times. The Yellowstone went only as far as Fort Pierre, whence she returned immediately, and as soon as another cargo could be shipped, started on a trip to Council Bluffs.

Captain La Barge went back up the river on this second trip of the Yellowstone to return to his post. It proved to be a most trying and pathetic voyage. The cholera, which was then epidemic throughout the country, broke out with great virulence on the boat, and so many of the crew died that Captain Bennett was forced to stop at the mouth of the Kansas River until he could go back to St. Louis for a crew. His pilot and most of his sub-officers were dead, and he33 was compelled to leave the boat in care of young La Barge, who thus began his career as a steamboat man on the Missouri. His several voyages had given him considerable knowledge of the art of handling these boats, and he had no misgivings in being left in charge, except the fear that the cholera might take him off. It was a very trying moment. Captain Bennett, when he started back to St. Louis, cried like a child. The terrible power of the disease unstrung everyone’s nerves. Victims often died within two hours after being attacked, and no one knew when his turn would come.

Scarcely had Captain Bennett left when a new difficulty arose. The “graybacks,” as the scattered population of western Missouri were then called, having learned that the Yellowstone had cholera on board, organized themselves into a pro tempore State board of health and ordered Captain La Barge to take the boat out of the State, or they would burn her up. The engineer and firemen were dead, so Captain La Barge fired up himself, and, acting as pilot, engineer, and all, succeeded in getting the boat above the mouth of the Kansas and on the west shore of the river, outside the jurisdiction of the State of Missouri.

The Yellowstone had a quantity of goods on board consigned to Cyprian Chouteau’s trading post, which was located some ten miles up the Kansas River.34 Captain Bennett had directed La Barge to turn over these goods to the consignees during his absence. Accordingly, at the first opportunity, he set off alone on foot to find the trading post and tell Mr. Chouteau to come and get his goods. When about a mile from the post he was met by a man who had been stationed there to watch for anyone coming from the Missouri. The news of the cholera was abroad and the lonely post had quarantined itself against the civilized world. The man would not permit La Barge to come nearer, and threatened to shoot him if he persisted. La Barge agreed to stay where he was if the man would return to the post and carry his message to Chouteau. This was done, and Chouteau sent back word to store the goods on the bank and leave them there. It was now too late to return to the boat that night after a fatiguing day’s work, and La Barge would have had to go supperless and coverless to sleep but for the kind offices of his old college chum and former companion in misfortune, Edward Liguest Chouteau, who happened to be at the post. Hearing of La Barge’s situation, he went to find him. He reached his friend’s bivouac about midnight and found him trying to pass the night in some comfort around a large bonfire. He brought something to eat and a large buffalo robe to sleep on, and La Barge got through the remainder of the night very well.

35

While the Yellowstone was lying above the mouth of the Kansas the Assiniboine passed down on her return trip.8 La Barge signaled for assistance, but Captain Pratt would not stop. “It was pretty hard,” observed the captain, in narrating this affair. “I never refused to answer a distress signal, even if the boat were engaged in the strongest opposition; but our two boats were in the same trade, bound to assist each other, and yet we were left there alone in the severest straits, with no idea when we should be relieved.”

When asked how these grave dangers, which were more or less his portion through life, affected him, Captain La Barge replied that, if in idleness and given time to think about them, they always depressed and in a measure unnerved him; but he was generally actively engaged, and the interest in his work and the responsibility resting upon him caused him to forget the danger. Violence and death were a familiar feature of the life in which he was engaged, and to some extent he became hardened to them. Speaking of the great number of deaths along the river, the Captain36 shook his head reflectively as he told of the many burials that it had been his lot to make. “There is a spot just below Kansas City—I could point it out now,” he said, “where I buried eight cholera victims in one grave. I could easily name a hundred localities along the river where I have buried passengers or crew. I generally sought some elevated ground for this purpose, which the ravages of the river could not reach. The graves were marked, if at all, with wooden head-boards, for there was generally no other material at hand, and if there were, time did not permit the use of it. It will never be known, and cannot now even be conjectured, how many of these forgotten graves there are, but enough to make the shores of the Missouri River one continuous cemetery from its source to its mouth. Were every white man’s grave along that stream distinctly marked, the voyageur would never be out of sight of these pathetic reminders of futile contests with the universal enemy. But, alas! no mark remains upon any but a very few, and the names of those who are buried in them are forever wrapped in oblivion.”

After a long delay Captain Bennett returned with a crew on the steamboat Otto, Captain James Hill, an opposition boat in the service of Sublette & Campbell. This was the year when Sublette & Campbell made such a strong show of competition with the American37 Fur Company.9 Sublette himself was on board the Otto at the time. As soon as Captain Bennett resumed charge of the Yellowstone the boat proceeded on her way and reached Cabanné’s post in August.

Cabanné having been expelled from the Indian country, the post had a new bourgeois, Joshua Pilcher, a man of long experience in the Indian country, and former president of the Missouri Fur Company. Late in the month of August Pilcher sent La Barge with a small outfit of goods to the Pawnee villages to buy some buffalo meat. La Barge packed his goods on five horses and set out. He found the Pawnees still absent, and as war parties of their enemies might be lurking around the vacant villages, he thought it prudent to await at a distance the return of the Indians. In the meanwhile his party ran out of provisions, and their situation was becoming serious when La Barge decided to go and get corn enough from the fields to last them until the Pawnees should return. He went with another man, and they soon loaded themselves with ears and returned to camp. This process continued successfully for several days, great pains being taken to levy tribute uniformly throughout the cornfield, so that the Indians might not detect the loss.38 They were not skillful enough in this, however, and finally had to pay for the corn.

On the fourth day of their foraging expeditions they were discovered by a small war party of Sioux about a mile off. They took to flight, and tried to infuse some life into their mules, but the stolid animals would not hurry. This was particularly the case with La Barge’s mule, which could scarcely be driven into a slow gallop. La Barge saw that at the rate they were going they would surely be cut off, and he told his companion, who had the best mule, to hurry to camp for help, and he would stand the Indians off with his rifle. The companion did not like to do this, but La Barge insisted. He felt comparatively safe for a short time, for he was in a perfectly open plain, where it was impossible for the Indians to approach under cover. Whenever they drew too near he would level his rifle at them and they would venture no further. In the meanwhile he kept moving on toward camp, and soon had the pleasure of seeing his companion riding up at full speed with re-enforcements.

When the Pawnees returned La Barge bought a good supply of meat and took it to Cabanné’s. There he found that veteran mountaineer, Etienne Provost, who at that time probably knew the western country better than any other living man. He had just come in for the purpose of guiding Fontenelle and Drips,39 partners in the American Fur Company mountain service, and owners of the trading post at Bellevue, to the Bayou Salade (South Park, Colorado), where they intended to spend the winter trapping beaver. Provost heard of La Barge’s adventure and complimented him very warmly upon it. He was now an old man, but he came up to La Barge, took him by both hands, and said to him: “I am glad you did not show the white feather to those rascals. You are the kind of man for this country. I am going to ask Major Pilcher to let you go with me. I have need of such men.” La Barge was very anxious to go, filled as he was then with the thirst of youth for adventure. But Major Pilcher needed his services and would not consent. Pilcher was very kind to La Barge, even permitting him to eat at his table—a great concession, for none of the employees were allowed to eat with the bourgeois of the post unless it was so stipulated in their contract of service. Pilcher took a special pride in his young engagé, and tried to put opportunities for distinction in his way.

40

In November, 1833, Pilcher sent La Barge down to a small trading post at the mouth of the Nishnabotna (river where they make canoes), kept by Francis Duroins for the convenience of a local band of Indians. La Barge’s mission was to take two twenty-gallon kegs of alcohol to Duroins. He was accompanied by a half-blood Indian, and they made the trip in a canoe. The first night they encamped on Trudeau Island, about two and a half miles above the mouth of the Weeping Water River. This island was named after Zenon Trudeau, a trader, brother of the noted schoolmaster, Joseph Trudeau, and was later called Hurricane Island, from the circumstance of its having been swept by a tornado. It has since been entirely washed away. This was the night of the ever-to-be-remembered meteoric shower of 1833. La Barge was awaked from his sleep by the brilliant light, and, though not apprehensive of any impending calamity, was naturally awe-struck at the extraordinary display. The meteors were flying, as it seemed41 to him, in all directions, and their number and brilliancy made the night as light as day. The half-breed companion was absolutely panic-stricken, and declared that the day of doom was at hand. But he did not forget, in his fright, the divine injunction to “eat and drink, for to-morrow we die.” Rolling himself up in his blanket, he besought La Barge to open the keg of alcohol and let him meet his fate as became a man in that wild and lawless country.

As nearly as La Barge could recall, the heavier part of the shower lasted about two hours. A singular incident occurred early in its duration. A deer which had become frightened at the unusual sight came bounding through the undergrowth and plunged directly into camp, coming to a dead halt scarcely six paces from where La Barge was sitting. He seized a shotgun and killed it with a load of buckshot.

In January, 1834, the winter express came up from St. Louis. The express was a matter of great importance in the early fur trade. It was sent from St. Louis every winter to all the posts. Usually an express started downstream from the upper posts before the arrival of that from below. They generally met at Fort Pierre, exchanged dispatches, and each made the return trip from that point. By means of the express an interchange of views was had between the house in St. Louis and the partners in the field; and42 the latter were able to send down statements of business, requisitions for supplies, with information as to the prospects for the ensuing season’s trade at the upper posts, and the condition of snow in the mountains. The carrying of the express was a matter of great danger and hardship. It was generally done in the dead of winter. Between Pierre and St. Louis it was carried on horseback; above Pierre on dogsleds. The packages were put up with the most scrupulous care, and were intrusted only to those in whom the company had absolute confidence. The bearers were not permitted to carry anything else, nor to do errands for others, but were required to attend to the express only. The chief danger on the long journey was from the cold, for at this season the Indians were not dangerous, being generally huddled together in their villages for the winter. The route above Bellevue was along the west shore to opposite Vermillion, where it crossed the river and remained on the east shore the rest of the way until opposite Fort Pierre.

Captain La Barge’s father brought up the express from St. Louis in the winter of 1834. He was to return from Cabanné’s post, and Pilcher was to provide for its carriage the rest of the way. A few days before his arrival a brutal murder occurred at the post. A half-breed named Pinaud, while in a state of drunkenness, shot and killed a white man named43 Blair. Both of the men were hunters for the post. Pilcher immediately put Pinaud in irons, to be held until he could be sent to St. Louis for trial. When the elder La Barge arrived Pilcher asked him if he would undertake to deliver the prisoner to the United States authorities in St. Louis. He agreed to try it. When ready to start he requested Pilcher to remove the irons and put Pinaud on a mule. This astonished Pilcher a good deal, but La Barge explained that the man could ride better with the free use of his limbs, which was also necessary to keep him from freezing to death. He said he could catch him if he undertook to run, for the mule was no match in speed for his horse. He would take the irons and put them on in camp.

The prisoner was delivered in due time to the proper authorities in St. Louis, where he was held for trial. And now ensued one of those miscarriages, or rather travesties, of justice which marked the entire history of the American Fur Company on the Missouri River. Although Pinaud’s crime was a cold-blooded and causeless murder, it was nevertheless of vital importance that he be acquitted; otherwise it would bring out the fact that the Company was violating the Federal statutes by selling liquor at its posts. The company therefore took good care that none of the people from the upper country who were conversant with the44 facts should be in St. Louis when the trial came off. The prosecution, consequently, could produce no witnesses, and the man was acquitted.

Two or three days after the elder La Barge left Cabanné’s post for St. Louis, Pilcher summoned young La Barge to him and asked him to take the express to Pierre. “There are old voyageurs here whom I can send,” he said, “but I can’t trust them. I want you to go. What do you say to it?”

“Well, Major,” La Barge replied, “I have never been as far above this post in my life, but if you have confidence in me I think I can get through.”

“I believe you will,” said the Major. “I will trust you, at any rate. Get ready and you shall have the best horse in the post.”

In fact Pilcher gave La Barge his own horse, a very fine animal. Captain La Barge made ready and set out alone in a country entirely new to him, uninhabited by white men, and now buried in the embrace of a northern winter. He took a few pounds of hard bread and a few ears of corn to parch, but for the rest subsisted on game. He followed the foot of the bluffs as far as possible, and in due time reached Fort Pierre. Fortunately, the day after his arrival the express from Fort Union came in. Exchanges were made, and after a short rest La Barge set out on his return trip. He reached Cabanné in good time.45 The exploit gratified Pilcher highly, and he said to La Barge, “I knew I had made no mistake.”

Captain La Barge recalled only two incidents on this trip: He saw one day, what he never saw before nor afterward, although he had heard hunters and Indians relate similar experiences, two dead elk whose horns had become interlocked in fighting, and who had died bound together in that way. While in camp one night, just above Vermillion, he had a good fire of dry cottonwood and willows, and was roasting a prairie chicken in the flame. Happening to look up, he saw four gray wolves only a little way off on the opposite side of the fire, looking steadily at him. He was almost paralyzed at the sight, but nevertheless did not leave his place, but quietly got his gun and pistols convenient for action and sat still and watched his visitors. After looking at him a few minutes, and concluding, apparently, that he was not the kind of game they were after, they withdrew.

In the month of April, 1834, La Barge was sent with a party under one La Chapelle to go to the Pawnees and bring down the bullboats with the winter’s trade. They were detained several days at the Pawnee Loup village, waiting for some of the Indians to come in. During this delay a band of horse-stealing Sioux slipped into the village one stormy night, and, opening the corrals, let out some sixty head of horses and46 got away without waking anybody up. When the theft was discovered the following morning the chief called for volunteers to go in pursuit. Some seventy-five men started, and with them La Barge and a companion named Bercier. La Barge had never had an experience of this sort, and thought the present opportunity a good one. On the second evening after their departure they discovered the thieves and their horses encamped on the Elkhorn River. There were about fifteen of the Indians. The pursuers carefully reconnoitered the position, and next morning at daybreak attacked it, killing eleven of the Indians and capturing all of the horses. The man Bercier, who accompanied La Barge, met death at the hand of another tribe of Indians thirty-one years afterward. In 1865 he went up the Missouri with Captain La Barge to Fort Benton, and was killed by the Blackfeet on the Teton River near that post.

On their way down the Platte from the Pawnees, on this trip, the party were greatly annoyed by rattlesnakes at the camps on shore. If they made camp before dark they carefully scoured the entire neighborhood and killed or drove off these dangerous reptiles. But they often kept on the river as long as they could see, and on such occasions could not take the usual precaution. The snakes were not pugnacious, and sought the camp only because of the warm nestling47 places they found there. They liked to creep into or under the blankets, and the great danger was that when the occupant of the bed awoke he might step on or otherwise hurt the snakes and cause them to strike before he was conscious of their presence. On one occasion Captain La Barge found two of these snakes under his coat, which he had folded and used for a pillow. In some places they were so numerous as to cause the Indians to move their camps. An instance of this kind occurred at Red Cloud, below what is now Chamberlain, S. D., where the site of the agency had to be changed. As late as 1883, when Captain La Barge was pilot of a boat in the service of a United States surveying party, he took some members of the party to a point near the Bijoux hills, where he remembered having seen long years before a colony of rattlesnakes. Sure enough, there they were, still as thick as in former days. The party killed 130 within a few minutes. Captain La Barge could not recall a single death from a rattlesnake bite in his whole experience on the river. He stated that swine were the best exterminators of these reptiles.

As soon as the robes had been packed into mackinaw boats at the mouth of the Platte, about the middle of May, 1834, La Barge started for St. Louis. This was the last of his service with Pilcher, for before his return the Major had left the post for some more48 important business in St. Louis. He had taken a great liking to the young engagé and undertook to secure him a promotion. He sent down by La Barge a letter of recommendation to Daniel Lamont, one of the partners of the upper Missouri department of the American Fur Company. Captain La Barge knew nothing of the letter at the time. It eventually found its way into the Chouteau archives, where it was discovered by the author of this work and shown to Captain La Barge sixty-two years after it was written. It read as follows:

“Near the Bluffs, May 16, 1834.

“Dear Sir: The bearer of this, Joseph La Barge, wintered with me last winter, and has been faithful, active, and enterprising. He wishes to get a clerkship on the Missouri, but I have not employed him for the reason that I have no use for him, nor do I suppose that Mr. Chouteau will employ him for this post, as I have informed him that there is no use for additional clerks. La Barge writes a tolerably good hand, and if you have any place for him above, I can recommend him as a modest and good young man who has done his duty here (as an engagé) very faithfully, and I think him worthy of a better situation.

“Your friend,

“Joshua Pilcher.”

49

After a few weeks’ visit among his friends in St. Louis in the spring of 1834 La Barge started back on the steamer Diana for Cabanné’s post. Pilcher was no longer in charge, having been succeeded by Peter A. Sarpy. During his service under Sarpy La Barge had an adventure which came near cutting off his career on the river almost at its beginning. Late in the fall of the year Sarpy sent him down to Bellevue to take charge of a herd of horses which was being wintered there for the mountain expeditions of Fontenelle and Drips. There were about 150 horses in the herd, and they were kept on the east side of the river in the bottoms, where they subsisted mostly on the bark of young cottonwood trees. This kind of forage was extensively used in those days. It was an excellent food and was liked by the stock. Instances are recorded where they have taken it in preference to grain. Horses throve well upon it, and it is related that Kenneth McKenzie at Fort Union fed it exclusively to his hunting stock.

50

The method of preparing the bark for forage along the Missouri River was as follows: The trees were cut down and the trunk then cut into short logs three or four feet long. In the winter time the bark was frozen and had to be thawed out before using. To do this the logs were stood up in front of a fire and turned around gradually until the bark was warmed through. It was then peeled off with drawknives and cut up into small pieces, after which it was ready for food. It was very essential that the bark be thawed out when fed, for the sharp edges of the shavings were like knife blades if frozen, and liable to cut the throats and stomachs of the horses. Animals were occasionally lost from this cause. After the logs had been stripped of their bark they were split and piled on the river bank, forming an excellent fuel for the next season’s steamboat. Traders at the various posts were under standing instructions to gather up the “horse wood” in their vicinity and pile it on the bank of the river, where it could be reached by the boats.

It was while engaged in this work of caring for horses that La Barge had the adventure just alluded to. It was mid-winter, 1834–35. The Missouri was frozen deep, and a pathway led from the post at Bellevue across the river on the ice to the east bottoms, where the herd was kept. The path ran between two large airholes through the ice—one just51 above and the other about a hundred yards below. The weather was extremely cold, and there was every indication of an approaching blizzard. Captain La Barge wrapped himself in a blanket coat, held tight to his body by a belt, and was armed with a rifle, tomahawk, and knife. He experienced no difficulty in crossing to the east shore, for the wind was behind his back. But before he was ready to return the blizzard was on in full force; the wind came from the west obliquely across the river, and the drifting snow completely obliterated the path. La Barge nevertheless felt confident of crossing all right, for the distance was short, and he knew the way so well that he felt as if he could follow it blindfolded. In fact, that was practically his present situation, for the wind drove the snow into his face so violently that it was impossible to look ahead. Getting his bearings as well as he could, he started across on a slow run in face of the blinding storm. It would seem in any case to have been a reckless performance, considering the existence of the airholes near the path; but La Barge was not given to enlarging upon future dangers, and forged boldly ahead. For once his confidence deceived him. All of a sudden he plunged headlong into the river. He instantly realized that he was in one of the air holes—but which one? If the lower one, he was certainly lost, for the swift current had borne him under the52 ice before he came to the surface. If the upper hole, he might float to the lower. But did the current flow directly from one to the other, and would he be at the top at the critical instant? All these questions and many more flashed through his mind with the rapidity of thought in the presence of imminent peril. He soon rose to the surface and bumped the overlying ice. Sinking and rising again he bumped the ice a second time. The limit of endurance was almost reached, when suddenly his head emerged into the open air. Spreading out his hands, he caught the edge of the ice. He held on until he could draw his knife, which he plunged into the ice far enough to give him something to pull against, and after much severe and perilous exertion he drew himself out. He had stuck to his rifle all the time without realizing the fact, and came out as fully armed as when he went in.

But now a new peril awaited him. The storm was at its height, the cold intense, and his clothing was drenched through. The bath which he had received had not chilled him in the least, for the water was much warmer than the air outside, and his exertion would have kept him warm anyway; but out in the wind the chances were that he would freeze if he did not quickly reach a fire. Hastily recovering his bearings, he set out anew, and had the good fortune to reach the post without any further delay.

53

It is needless to say that the inmates of the post were slow to credit the Captain’s story, in spite of the proof afforded by his frozen clothing. Martin Dorion, one of the most respectable of the numerous family of that name, said to La Barge, “Your time hasn’t come yet. Your work remains to be done.” It was not until after he had changed his clothing and had settled down by a strong fire that the reaction from the terrible strain came; but then for a little while he felt as if he could not keep himself together.

La Barge was an expert swimmer, having practiced the art from childhood. He learned to swim in the old Chouteau pond, which filled the hollow near where the Union Station of St. Louis now stands. It was not an uncommon feat for him in his younger days to leap from a boat when he saw an elk or deer crossing the river, outswim and catch it, hold on to it until its feet touched the bottom, and then kill it as it was ascending the bank.

In the year 1850 La Barge was making a voyage to the upper river on the steamer St. Ange. Mrs. La Barge and some other ladies were on board. One day a boy fell overboard from the forecastle. La Barge, who happened to be near, instantly leaped in and seized him, keeping him from the wheel (it was a sidewheel boat), and got him to shore before the boat could get there. A lady sitting on the deck with Mrs.54 La Barge asked her if she was not alarmed when her husband leaped overboard. She replied that she was not in the least; that she knew Captain La Barge’s qualities as a swimmer too well to doubt his ability to rescue the boy.

In the summer of 1838, when La Barge was serving as pilot on the Platte, another incident occurred which illustrated his skill as a swimmer. At a point some twelve miles below Fort Leavenworth one of the guys of the yawl derrick broke, precipitating the yawl into the river. This craft was so essential to the steamboat in navigating the Missouri River that its loss would at any time be irreparable. The alarm was instantly given that the yawl was overboard. Captain La Barge was in his stateroom, but immediately hastened to the stern of the boat, where he met Captain Moore, the master. The latter said he had ordered the steamboat to the shore and would send men down the bank to try to recover the yawl. Captain La Barge replied, “I will get the yawl; send some men down to help me bring it back.” So saying, he plunged into the river, overtook the yawl, and brought it to land half a mile below the boat.

In the spring of 1835 Captain La Barge went down, as usual, with the mackinaws to St. Louis. This terminated his three years’ engagement with the company. He remained in St. Louis all summer except55 when absent on short river trips in the vicinity. In the fall he went up the Missouri to the Black Snake Hills (St. Joseph, Mo.), where he engaged for the winter to the trader Robidoux, who was in charge. Nothing of interest transpired, and in the spring he returned to St. Louis.

The next four years of Captain La Barge’s life were a practical apprenticeship in the business which he was to follow as a career. They were spent almost entirely on the lower river in the various capacities of clerk, pilot, and master on different boats. Not many events of special note occurred, and the actual voyages made are now somewhat uncertain. But the experience was a useful one, and by the time it was over the Captain had won a reputation as a pilot which thereafter insured him continuous service.

The Captain’s first service during this time was as assistant pilot on the steamer St. Charles, but the boat was burned at Richmond landing, opposite Lexington, Mo., July 2, 1836. He then engaged as pilot on a new boat, the Kansas, and ran in the lower river the rest of the season. In the spring of 1837 he shipped as clerk on the steamboat Boonville, but this boat was wrecked on a snag early in November near the mouth of the Kansas River, and was lost with a full cargo of government freight. In the spring of 1838 he went as pilot on the Platte, a boat built during56 the previous winter, and the first double-engine boat that ever plied the river. He remained on this boat for two years, mainly on the lower river. He made but one trip to the far upper river, and started, in the fall of 1838, for the Bayou la Fourche, to spend the winter in the sugar trade. The boat had gone scarcely thirty miles below St. Louis when she ran upon a snag, which tore an immense hole in the bottom and caused her to sink immediately. In the spring of 1840 the Captain again entered the service of the American Fur Company as pilot of the steamer Emily, which was to make a trip to Fort Union. Before the season was over the company assigned him to work on a new steamboat, the Trapper. For some reason the Captain did not like this assignment and refused to accept it. This incensed the company, who considered him bound to serve wherever directed. Neither side would yield, and the Captain forthwith left the service of the company.

During these four years of apprenticeship several incidents of interest occurred, some pertaining to the local history of the country and others of a purely personal character. Captain La Barge saw a good deal of the Mormons, who at this time were undergoing those persecutions in western Missouri which finally drove them from the State. They were frequently57 on the steamboats, and the Captain at one time or another saw nearly all the leaders, including Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum, Sidney Rigdon, Orson Hyde, and others. Captain La Barge never liked the appearance or demeanor of Smith, and never believed in his sincerity. He thought more of Rigdon, who was a most pleasant talker and who once preached a sermon on his boat. Captain La Barge’s knowledge of the Mormons and their doings at this time led them to request him, nearly sixty years afterward (1895), to appear for them and give evidence as to their title to the land in Independence, Mo., on which their temple was built.

Another incident which occurred about this time calls up one of the famous characters of American frontier history—Daniel Boone. This noted pioneer had passed most of his life in Kentucky, but when settlement began to crowd upon his primeval domain he moved westward and settled in Warren County, near St. Charles, Mo., where he died in 1820. Some years later, by agreement between the governments of Kentucky and Missouri, Boone’s remains were moved to the latter State. A committee from the Kentucky Legislature went to Missouri on the occasion of the removal and were taken up the river to Marthasville, where Boone was buried, on the steamer Kansas. Captain La Barge, who was serving on the58 Kansas at the time, recalled the circumstances perfectly. Many years later he was invited to go to Frankfort, Ky., to attend an anniversary celebration pertaining to Boone’s career, but was not able to accept. La Barge’s father knew Boone intimately, and La Barge himself was a warm friend of his son Nathan Boone.

59

The term “opposition” in the early Missouri River fur trade had a definite and specific meaning. It applied to any trading concern, great or small, individual or collective, which was doing business in competition with the American Fur Company. So powerful was this company that it never permitted any other company or trader to occupy the same field with itself except at the cost of ruinous commercial warfare. There were many attempts to compete with it, but all of them ended in failure.

The incident related in the last chapter, which led Captain La Barge to quit the company’s service, induced him to try his own luck as an opposition trader; but the result, which quickly developed, was quite like that of his many predecessors and successors in the same line. The Captain had laid by a few thousand dollars, which he put into the venture, and secured additional capital from J. B. Roy and Henry Shaw of St. Louis. The steamer Thames was chartered to convey the cargo as far as Council Bluffs, for, owing60 to the lateness of the season, it was not thought safe to attempt to take the boat further. An outfit of wagons was carried along, and it was expected that they would be able to purchase enough horses and oxen to haul the goods the rest of the way.