Courteously Yours,

W. L. Adams

BY

PRESS OF

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

PHILADELPHIA

1911

Copyright, 1911

By William L. Adams

All Rights Reserved

This Book is Respectfully

Inscribed to my

“BUNKIES AND SHIPMATES”

OF THE

ARMY AND NAVY

In introducing the following narratives, the contents of which have been gleaned through my voyage around the earth in quest of excitement and natural oddities, for which since childhood I have possessed an insatiable desire, I wish to acquaint the reader, in a brief prefatory discourse, with the nature of the work that is to follow, and thereby gratify the curiosity, so natural at the beginning, in a reader of reminiscences.

Through the prevailing influence of some loyal friends, whom it has been my good fortune to have had as correspondents during my military career, I herein attempt to depict events as they actually happened, without recourse to imagination.

Having served under the dominion of “Old Glory” in the Occident and Orient, on land and on sea, in war and peace, for the period of ten years, I naturally fell heir to novel and interesting occurrences, so numerous that to attempt to describe in detail would necessitate the space of many volumes; I therefore resort to conciseness, at the same time selecting and giving a comprehensive description of those occurrences which are most important in my category of adventures.

As an author I do not wish to be misunderstood. I merely desire to portray what has come under my observation, rather than make a Marathon with the laurels of so dignified a profession, and in so doing communicate to those whose arduous duties at home have deprived them of the romance of globetrotting, and thereby distribute the knowledge that some more silent person might never unfetter.

In conclusion to this preface, I desire to say, that I have refrained from the manufacture of episodes or any tendency toward fiction, which I trust the following pages will confirm, and that, as from the description of a spectator, these narratives will meet with the approval of those into whose hands they might chance to fall.

The Author.

| Chapter | Page | |

| I | Campaign of the “Governor’s Troop,” Penna. Vol. Cavalry | 15 |

| II | On board a “Man-of-war” from New York to Morocco | 45 |

| III | Thrilling Adventure with Moors in the “Kasbah” of Algiers | 63 |

| IV | From the Pyramids of Egypt to Singapore | 71 |

| V | Hong Kong, China, and the Denizens of the Underworld | 90 |

| VI | A Trip to Japan | 103 |

| VII | War Orders in the “Land of the Rising Sun” | 118 |

| VIII | The Cowboy Soldier, a Coincidence | 145 |

| IX | Life Among Hostile Moros in the Jungles of Mindanao | 169 |

| X | A Midnight Phantasy in California | 197 |

| XI | “Semper Fidelis,” the Marine “Guard of Honor,” World’s Fair, St. Louis. 1904 | 208 |

| XII | Topographical Survey in the Jungles of Luzon | 242 |

| XIII | “Cock-fighting,” the National Sport of the Philippines | 271 |

| XIV | Departure of the 29th Infantry for the Home-land; Reception in Honolulu | 279 |

| Page | ||

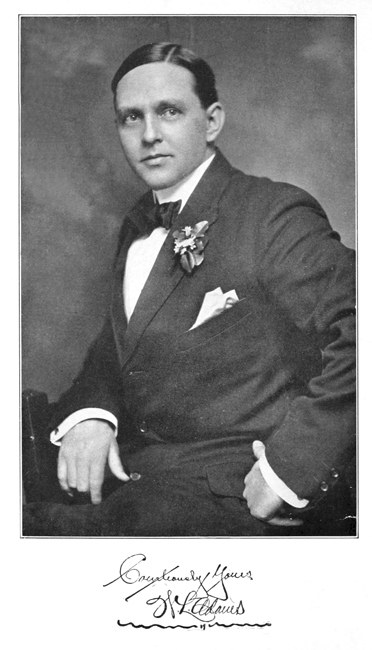

| William Llewellyn Adams | Frontispiece | |

| Detachment of “Governor’s Troop,” Mt. Gretna, 1898 | 20 | |

| A Trooper | 42 | |

| Tent No. 2, Fynmore and Adams, “World’s Fair,” St. Louis, 1904 | 214 | |

| Coleman and Adams, Gun-mule “Dewey,” Machine-gun Battery | 258 | |

| Machine Gun Platoon of the 29th Infantry in the Snow Capped Wasatch Range, Utah | 260 | |

The “Pandora Box”—Call for Volunteers—Mustered In—Breaking of Horses at Mt. Gretna—Liberality of the Ladies of Harrisburg and Hazleton—Departure of the Tenth Pennsylvania for the Philippines—My First Rebuff, by Major-General Graham—Thirty Thousand Soldiers Celebrate the Victory of Santiago—Troopers Decorated with Flowers by the Maidens of Richmond—The Concert Halls of Newport News—The Ghost Walks—Off for the Front—Convoyed by Battleships—Porto Rico—Spanish Hospitality—Wounded by a Shell—Jack the “Mascot” Passes the Deal—Reception in New York, Harrisburg, and Hazleton.

The destruction of the United States battleship Maine in Havana harbor, on the night of February 15, 1898, was the key to the mysterious “Pandora Box,” containing maps of new United States possessions, the commission of an admiral, the creation of a President, the construction of a formidable army and navy, the humiliation of a proud nation, and numerous other undisputed ascendencies.

The uncivilized, brutal, and oppressive methods resorted to by the Spaniards in conducting military operations on the Island of Cuba and other territory adjacent to the United States had long been a theme of discussion by patriotic and sympathizing Americans. When the news flashed over the wires that the big man-of-war, the Maine, had been blown up and two hundred and sixty-six members of her gallant crew had been sent to a watery grave, the hearts of American youths burned with indignation and every mother’s son yearned to avenge what was considered Spanish treachery. What followed is entered in the archives of American history and is familiar to all. The call for volunteers was responded to universally, there being so many applicants to fill the ranks that only the flower of the American youth was accepted.

When the news was wired broadcast that Commodore Dewey had fairly annihilated the Spanish fleet in Asiatic waters, without the loss of a man, there was a burst of enthusiasm that can well be imagined by those too young to remember the occasion. At 9.00 A.M. on the second of May, 1898, this news was received in Hazleton, Pennsylvania. It was followed by a telegram from the Captain of the “Governor’s Troop,” Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry, of Harrisburg, which stated that twelve vacancies existed in that troop and that in accordance with the request of Governor Hastings these vacancies should be filled with the first volunteers from the city of Hazleton. In two hours’ time the recipient of the telegram, Mr. Willard Young, had notified and enlisted twelve of Hazleton’s stalwart sons, and at 7.40 A.M. the next morning, amidst the waving of the national colors and cheers from the populace the boys were escorted by the famous old Liberty Band to the Lehigh Valley Station where, after bidding adieu to relatives, sweethearts, and friends, they boarded a train for Mt. Gretna, the military rendezvous.

The men who comprised this Hazleton assemblage were—

Ario P. Platte, Jr.

Schuyler Ridgeway

John J. Turnbach

William K. Byrnes

Willard Young

Charles H. Rohland

Edward R. Turnbach

Stephen A. Barber

Edwin W. Barton

Herbert S. Houck

Clarence H. Hertz

William L. Adams

En route to Pottsville the train was boarded by my life-long friend, David L. Thomas, who was on his way to his law office. On learning the destination of the patriots he laid down his “Blackstone” and wired his parents in Mahanoy City that he had cast his fortunes with the avengers of Spanish tyranny. Of this group of volunteers, two loyal soldiers have answered the last roll call, namely: Ario P. Platte, Jr., and David L. Thomas.

Arriving at Mt. Gretna we beheld, under miles of canvas, Pennsylvania’s gallant National Guard. Upon inquiry we found the cavalry headquarters, consisting of the “City Troop” of Philadelphia, the “Sheridan Troop” of Tyrone, and the “Governor’s Troop” of Harrisburg, stationed in a clump of forest near the lake.

Immediately reporting to Captain Ott, commanding the “Governor’s Troop,” we were assigned to quarters in large Sibly tents and met the old members of the troop, among whom I was delighted to find Feight and Barker, two classmates of mine at “Dickinson Seminary.” We were at once issued mess kits, the most necessary equipment required by a soldier when not in the face of the enemy, and, roaming hither and thither, awaited the usual medical examination preparatory to being mustered into the service of the United States, which, after several dreary and monotonous days, occurred on the 13th of May. After being fitted in natty cavalry uniforms we were drilled twice daily on foot by an ex-sergeant of the regular army, whose service in the regulars had qualified him for the arduous task of breaking in raw recruits. This drill was an experience not relished very much, as profound obedience was required, and many wished the war was over before it had really begun.

Before bringing the troop to attention, the sergeant would usually say: “Now boys, I want you to pay attention to my orders, and if you make mistakes I am apt to say some things I do not really mean.” So we would take his word for this, but ofttimes thought things we did mean. This was his song: “Fall in,” “Troop attention,” “Right dress,” “Front,” “Count off,” “Backward guide right,” “March,” “As skirmishers,” “March,” “Get some speed on you,” “Wake up,” “Wake up,” “Assemble double time,” “March,” “Look to the front, and get in step, you walk like farmers hoeing corn,” “Close in,” “Close in,” “Take up that interval.” These were the daily commands, until the troop was able to execute close and extended order to perfection. Then came the horses, and the monkey drill, and some pitiful sights of horsemanship, until each of the boys had accustomed himself to his own horse and had become hardened to the saddle.

At first we were equipped with the old Springfield rifle, but this was soon replaced by the Krag-Jorgensen carbine. Each trooper was soon fully equipped as follows: horse, McClellen saddle, saddle bags, bridle, halter, and horse blanket, carbine, saber, Colt revolver, belts, and ammunition, canteen, mess kits, sleeping blanket, shelter half, and uniforms.

The ladies of Harrisburg and Hazleton were extremely generous to the troop. From Harrisburg each soldier received a large and beautiful yellow silk neckerchief, a Bible, and a large quantity of pipes and tobacco. From Hazleton came literature and boxes after boxes of edibles, which were greatly relished by the troopers.

Some time was consumed in the breaking of horses, getting them bridle wise, and training them to the saddle, and this afforded great amusement to the thousands of spectators who visited the reservation daily. The troop, which consisted of one hundred privates and three commissioned officers, was made up of men from various walks of life. Lawyers, athletes, students, merchants, ex-regular-army soldiers, cowboys, and Indians swapped stories around the camp-fires at night. Every day, after the usual routine of duty had been performed, games of all descriptions were indulged in, poker under the shade of an “A” wall tent usually predominating. One of the entertaining features of the camp was a quartette of singers, members of the “Sheridan” and “Governor’s” troops, and ex-members of the University of Pennsylvania Glee Club. These boys were always in demand.

“Broncho buster,” George S. Reed, an ex-Texas ranger, Nome gold miner, and survivor of several duels, the most noted man of the “Governor’s Troop,” had cast his fortunes with the soldier “lay out,” and had boasted that there never was a broncho foaled that he could not cling to. “Broncho’s” debut as an equestrian was to ride a horse we called the “rat,” a bad one. Reed had great difficulty in getting his foot in the stirrup, as this animal would bite, buck, and kick, and besides held a few tricks in reserve. Finally, taking a desperate chance, “Broncho” swung himself into the saddle and the show was on. The horse plunged, bolted, and bucked, in trying to unseat the rider. When all efforts seemed to have been exhausted, the “rat” bucked, and made a complete somersault, rolling the ranger on the turf, then rising and doing a contortion, wriggled through the saddle girth and blanket, and bolted for the timber. “That horse is mad,” said Reed, brushing the dust from his uniform. “Did you see it loop the loop?” The horse that fell to “Broncho’s” lot was a gentle animal, that could tell by instinct when the canteen was empty, and would stand without hitching at any point where the goods could be supplied.

Each day brought forth news of the mobilization of troops and the progress of the war. Mt. Gretna, an ideal place for a military rendezvous, presented a grand spectacle. Regiments were rigidly disciplined and drilled to the requirements of war, sham battles were fought, galloping horsemen could be seen repulsing the enemy, while the wild cheering of the infantry in the charge, and the reckless maneuvering of artillery in establishing points of vantage for getting into action, had the aspect of mimic war.

Days rolled by and the troops yearned for active service. The Tenth Pennsylvania Infantry, having received orders to proceed to the Philippine Islands, was the first regiment to break the monotony. There was great activity in breaking camp, and a speedy departure amidst a wild demonstration enthused the boys whose fate lay with the fortunes of war, and whose valiant bravery along the south line, from Bacoor to Manila, will ever remain vivid in the annals of the insurrection.

The news of the departure of the “Rough Riders” for Cuba was heralded with much joy as a forerunner of our getting to the front, also the distribution of regiments to southern camps, where the sons of the “Blue and the Gray” commingled and fraternized as comrades fighting for the same cause, and spun yarns of the bloody strife of the rebellion in which their fathers had opposed each other in a bitter struggle.

The promulgation of the general order directing our departure for the South was received with cheers. Breaking camp was immediately begun, the loading of horses and equipment on the train being accomplished with the dexterity of a troop of regulars. All along the route the train met with an ovation. There was waving of flags and handkerchiefs, bells were tolled, and the shrill whistles of factories welcomed the boys on to the front. Arriving at Falls Church, Virginia, we at once set to work unloading our horses and accoutrements of war, which was accomplished with almost insuperable difficulty, due to our having reached our destination at night and in a blinding rain-storm.

Among the members of our troop was a Swedish Count, and at this point I recall a little incident which it will not be amiss to relate. We had unloaded our horses and were awaiting orders, when the Count approached me and said:

““Bill, ven do ve eat?”

““I guess we don’t eat, Count,” I replied; “these are the horrors of war.”

“Vell, py tam,” said the Count, “dis vore vas all horrores. I vanted to blay benuckle on der train und der corporal say: ‘You go mit der baggage car, unt cook some beans,’ unt by tam, I couldn’t cook vater yet.”

We remained at Falls Church over night, and in the morning marched to Camp Alger through blinding torrents of rain and fetlock-deep in mud. This camp, like most Southern camps, was very unhealthy, the heat was stifling, and many soldiers succumbed to fever. Here the troops of cavalry were consolidated into a squadron, consisting of Troop “A” of New York, Troop “C” of Brooklyn, “City Troop” of Philadelphia, “Sheridan Troop” of Tyrone, and “The Governor’s Troop” of Harrisburg, under the command of Major Jones, formerly captain of the “Sheridan Troop,” who relieved Captain Groome, of the “City Troop” of Philadelphia, who had been temporarily in command.

Camp Alger was a city of tents, as far as the eye could discern in every direction, there being about thirty thousand soldiers in the camp. My first duty at this Post was a detail as “orderly,” at General Graham’s headquarters. With a well-groomed horse, polished saddle, and soldierly immaculateness, I reported for duty. Entering the General’s spacious tent and saluting, I said:

“Sir, Trooper Adams, of the ‘Governor’s Troop,’ reports as orderly to the Commanding General.”

“Very well,” replied the General; “give the Colonel of the Second Tennessee my compliments and tell him I will review his regiment at 4.30 P.M.”

“Yes, sir, but, by the way, General,” said I, “where is the Second Tennessee located?”

“Make an about face and follow your nose,” the old man replied, and I did; but if the old General could have heard the mute invectives aimed at him I probably never would have told this yarn. I do not blame him now, as I realize how unmilitary I was. I had no difficulty in finding the Colonel of the Second Tennessee, as I kept my nose right in front of me.

The news of the victory of Santiago was celebrated by the troops in gorgeous style. Regiment followed regiment in wild acclaim, cheers after cheers resounded from the throats of the thirty thousand soldiers who were anxiously awaiting their call to the front. Bonfires of tar barrels were kept burning all night, and the excitement of the camp was intense.

The cavalry was ordered to Newport News to await the arrival of the transports; but, unlike the Sixth Massachusetts, that was stoned in Baltimore at the outbreak of the rebellion, our greetings in the South were exceptionally friendly. At Richmond bouquets of flowers were scattered in profusion among the soldiers, and many a fair maiden left the station with a pair of cross sabers pinned to her shirtwaist.

Our camp at Newport News was on sandy soil on the banks of the James River, which afforded excellent bathing and fishing. Here the cavalry received their khaki uniforms, which were the first issued to United States troops and had the appearance of an officer’s regimentals. As a consequence it was a common sight to see a “doughboy” saluting a trooper as he strolled through the city. A member of a Kentucky regiment was heard to remark: “That Pennsylvania cavalry is hot stuff; they are all officers.”

A few days after pitching camp, something happened; it is an occasion when a soldier possesses that air of complacency which invariably pervades the atmosphere. It is when the “ghost walks” (pay day) that the soldier is not only happy, but has a keen desire for making every one with whom he comes in contact happy. As a dispenser of pleasure, when he has “the necessary,” his speed brooks no competition, and all others look like “pikers” compared with “the man behind the gun.”

In 1898 Barton’s Theatre and Concert Hall was a nightly scene of revelry, by cavalry, artillery, and infantry, and from a spectator’s point of view it was hard to decide which was of more interest, the scenes in front or in rear of the footlights. Songs that reached a soldier’s heart were sung by dashing “prima donnas from the cottonfields of Dixie,” the soldiers joining in the chorus. After the “ghost had walked” this particular concert hall fell into the hands of the boys, among whom was found talent far surpassing anything behind the footlights. The soubrettes of the ballet dance mingled with the boys, and these scenes were equivalent to the “Can Can” of the famous “Red Mill” of Paris, or a Creole “Bal Masque” during a New Orleans “Mardi Gras.”

As the orchestra struck up the music to “For he is only a Soldier Boy,” a dashing southern beauty, in military costume, would saunter to the footlights, accompanied by a chorus of lesser lights, whose evolutions, combined with their singing, were extremely pretty and inspiring to the soldiers. This sketch brought forth deafening applause, dying out only as a trooper announced that he would endeavor to recite “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere,” or perhaps “Tam O’Shanter,” while another would volunteer to inflict us with “Casey at the Bat” or “The Face upon the Bar-room Floor,” to the mournful strains from the dirge of Imogen, a sure harbinger for the dispensers of “sangaree” to get busy and take orders. Another song, and the dance was on once more and continued until the “dog watch” of the night, when the soldiers realized that at reveille every man must be in ranks to answer to the call of his name or suffer the alternative, a berth in the “brig.”

This was the bright side of war, and, as each soldier was intent on getting to the front, it was the exception rather than the rule to hear of a misdemeanor being committed, or even to hear of a man being confined to the “guard house.”

Newport News was a gay place in ’98. Its people were very hospitable and friendly with the troops. Old Point Comfort and the Forts of Hampton Roads were but a short run by rail from the camp, and these were favorite resorts of the soldiers. Great excitement prevailed when the order for the Porto Rican expedition—“Pennsylvania Cavalry to the front”—was received.

The transport Manitoba had been fitted from an old cattle scow to a serviceable troop-ship, and had just returned from conveying a detachment of “Rough Riders” to Cuba. This vessel was spacious but lacking in the accommodations of our present-day transports that ply the Pacific. Considerable time was spent in getting our horses and munitions of war on board. When the signal to cast loose and provide was given we had on board three troops of cavalry, three batteries of field artillery, one battalion of Kentucky infantry, and detachments of engineer, hospital, and signal corps, seven hundred head of horses, and three hundred head of mules, besides the cargo of munitions of war.

Our time on board was occupied in preparing for a harder campaign than materialized. Carbines and six-shooters were oiled, and sabers burnished (the scabbards of these, being nickel-plated, required merely a coating of oil to keep them from rust). Our boots were greased, and the front and rear sights of our carbines were blackened. The boys scalloped the rims of their campaign hats, and some were tattooed by adepts in the art. Cards and reading were other pastimes of the voyage.

The fifth day out the United States cruiser Columbia and battleship Indiana were sighted; they had come to convoy the ship into the harbor of Playa Del Ponce. Arriving in the harbor at night, we had the misfortune to run on a sand-bar, where, being compelled to anchor with a list of about forty degrees, the possibility of our landing at night became rather vague. While making preparations for an attempt to land, a heavy gale encompassed the bay, making our position perilous, and, as this continued throughout the following day, it was with the utmost difficulty that our horses and mules were landed, a number of them being swung overboard and allowed to swim ashore.

Having finally reached the ground of the enemy, great precaution was taken to avoid a surprise; the water was inspected to make sure that it contained no poisonous substance and the orders in posting sentinels were rigidly enforced—each sentry before being posted had to be thoroughly familiar with his orders, being required to repeat them verbatim, and was also admonished as to the importance of keeping constantly on the alert. He was forewarned that to be found asleep on post in the enemy’s country meant to be tried by court-martial and if convicted to suffer the penalty of death.

Our first rendezvous was alongside of an old Spanish cathedral, surrounded by plantations of sugarcane, coffee, hemp, and tobacco; here we pitched a camp of shelter or “dog-tents” as they were generally called. As we were getting our accoutrements of war in shape the rapid fire of the Sixteenth Pennsylvania engaging the enemy could be distinctly heard, this engagement, however, being of short duration, like all other Spanish-American encounters in the West Indies.

Playa Del Ponce is the port of the city of Ponce, and is the shipping point for that section of the Island of Porto Rico. The town is surrounded by rich plantations of tobacco, coffee, sugarcane, and rice, also trees teeming with oranges, cocoanuts, guavas, lemons, grape-fruit, and groves of bananas and plantains. The staple production of the island is tobacco, from which is manufactured a very choice brand of cigars. The city of Ponce lies inland a distance of about three miles, and is typically Spanish in its architecture.

Shortly after our arrival at Playa Del Ponce, I had occasion to take my horse in the ocean for a swim, which was great sport and beneficial to the animal. In dismounting on my return to the beach, I had the painful misfortune to tread on a thin sea shell which penetrated my heel, breaking into several pieces. On my return to the camp I found the troop surgeon had left for Ponce, so seeking the assistance of a Spanish-Porto Rican physician, one Garcia Del Valyo, I was relieved after considerable probing, of the broken pieces of shell. The wet season being in progress and our hospital facilities limited, the doctor kindly offered me quarters in his beautiful residence, and recommended to my troop commander that I remain at his home until my wound had healed. To this the officer acquiesced.

I was given a room overlooking the bay on one side, with the town bounding the other; a crutch and an oil-cloth shoe were provided for me, with which I was able to hobble around with the two beautiful daughters of the old gentleman, namely, Anita and Consuelo Del Valyo. They spoke the Anglo-Saxon language fairly well and taught me my first lessons in Spanish, while I in return instructed them in my language. Both were artistes, being skilled in painting, sculpture, and music, and I often recall the happy evenings spent listening to the sweet notes of “La Paloma” as sung to the trembling tones of a mandolin accompaniment. Traditional custom permitted the piano and various Spanish songs during the day, but never “La Paloma,” wine, and the “Fandango” until after twilight. It was a picturesque sight to watch these senoritas perform the “Fandango,” clicking the castanets and gracefully tapping the tambourine as they whirled through coils of cigarette smoke.

I spent nine days in this hospitable domicile and was sorry when my wound had healed, but alas! I had to join my troop, which had departed for the interior. Before leaving Playa Del Ponce, I was presented with a small gold case containing the miniatures of these charming ladies. During the campaign on the island, I made several trips in to see them, accompanied by members of the troop, and before our departure from Porto Rico, had the extreme pleasure of attending a genuine Porto Rican “Fiesta.” It is sad to relate that the entire family suffered the fate of a large percentage of the population of Playa Del Ponce, in the terrible tidal wave which swept that portion of the island in 1899. Far be it from me to ever forget the kindness, engaging presence, and irresistible charm of these unfortunate people.

On my way to join the troop, I met the Sixteenth Pennsylvania Infantry, escorting about eight hundred prisoners of war into the city, where they were to remain in incarceration until the arrival of the transports which were to convey the Spanish soldiers to Spain. When they halted near the old stockade in the city of Ponce I secured some unique curios including a Spanish coronet of solid gold (a watch charm), rings, knives, Spanish coins, and ornaments of various kinds.

Having finally reached my troop and reported for duty, I joined my old “bunkies,” Young and Turnbach, and learned from them that the soldiers were starving to death on a diet commonly known as “canned Eagan,” others dubbed it “embalmed beef” and swore that no cattle were ever taken alive that supplied such meat, as they were too tough to surrender. Suffice it to say it was at least a very unwholesome diet. The British bull-dog “Jack,” a “blue ribbon” winner that had been purchased at a London dog-show by Norman Parke, a member of the troop, was a worthy “mascot” and general favorite among the soldiers of the squadron. Parke, having been detailed as orderly to Colonel Castleman, which necessitated his absence from the troop, presented the dog to Trooper Schuyler Ridgeway, in whom “Jack” found an indulgent master. Schuyler, in order to demonstrate the quality of the “encased mystery,” had a can of it tapped, and invited the dog to sink his teeth in it. “Jack” with true bull-dog sagacity refused, realizing, I presume, that it would be attempted suicide, and withdrawing a short distance gave vent to his spleen by a wicked growl, after which a pitiful whine which seemed to say, “Home was never like this.” Reed, the ranger, said he had played the starvation game before, even to chopping wood in some kind lady’s woodshed for his dinner, and added that Spanish bullets were only a side line to the present grit he had hit.

Camp life in the tropics in active service was not without its pleasures, however, and, as fruit grew in abundance, sustenance was maintained even if it was of the Indian variety. Details of mounted scouting parties galloped through the mountains daily, taking observations and frequently exchanging shots with guerrillas, who in riding and marksmanship were no match for the American troopers. The cavalry squadron figured in several skirmishes, but the retreat of the Spanish from the carbine volleys and glittering sabers of their foe put them to rout, so that I doubt if the same troops ever reassembled.

At last the news of the armistice was received, hostilities had ceased, and preparations for the trip to the home land were begun. Hither and thither we had marched for months, in cold and hot climates, slept in rain under ponchos with saddle-bags for pillows, lived on the scanty rations of field service, and now the time had come for our return, the war being practically over. The transport Mississippi, a miserable specimen of “troop-ship,” had been put at our disposal, and was to convey the greater part of General Miles’ expedition to New York City.

After striking camp and loading all the equipage of war accessories onto army schooners, a march of a few hours brought the cavalry to the point of embarkation. Playa Del Ponce presented a spectacle of grand military activity. Soldiers representing the army in all its branches were busily engaged in storing aboard ship the munitions of war and necessary rations for the homeward bound voyage. The artillery and cavalry were spared the irksome duty of loading their horses, these animals being left behind for the relief of the “regulars.” When all was in readiness and the signal given, the “homeward bound pennant” was flown to the breeze, as the ship’s bell tolled seven. Steaming northwest over a sea of calm saline billows, three cheers from the deck of the transport resounded to the shore, and, as the troops wafted adieu to this verdant island of the West Indies, it was with silent regret that lack of opportunity had prevented them from accomplishing the notable achievements of their forefathers—but such are the fortunes of war.

Our return was uneventful until we reached Sandy Hook, where the transport was met and convoyed through New York Harbor by myriads of yachts, launches, and tugs loaded with relatives and friends of the boys who had offered their lives for their country and many of whom the grim reaper had grasped from loving ties and the comradeship of their compatriots.

The reception in New York City was one grand elaboration of hospitality, evidenced by the demonstration of the thousands of people who thronged the landing place. Numerous bands of music played inspiring airs, as the city’s fair ladies dispensed chicken sandwiches and demijohns of wine to the soldiers, while others fairly covered the squadron with garlands of beautiful flowers. The reception in New York lasted about four hours, after which the “Governor’s Troop,” led by its gallant commander, Captain (now Major) Ott, of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, marched to and boarded a section of Pennsylvania Railroad coaches, and was ere long rolling over the rails toward the capital of the Keystone State.

On the arrival at Harrisburg, the home of the “Governor’s Troop,” an immense demonstration awaited the boys. Leaving the train in their worn habiliments of the jungle, the troopers were soon dressed in ranks, answered roll call, had counted off, and were marching behind a band of music, under a bower of pyrotechnics that resembled a mythological scene in “Hades.” After parading through the principal streets of the city, the troop was marched to the armory, which was beautifully decorated for the occasion; here the battle-scarred heroes of a successful campaign sat down to a banquet, over which an host of Harrisburg’s fair maidens presided. Oh for a moving picture of that scene! Each soldier wore a vestige of the pretty silk neckerchief the Harrisburg ladies had presented him with. Speeches were made by prominent citizens, songs were sung and toasts responded to, and it was with a feeling of deep appreciation that the troop left the banquet hall to seek a much-needed rest. The following day was spent in meeting friends and relating episodes of the campaign.

The Hazletonian complement of the “Governor’s Troop” had been apprised of a demonstration awaiting them at their home city, and upon the reception of the prescribed two months’ furlough, departed for the scene of the climax to the campaign. This Hazleton greeting was the most enthusiastic reception of all, perhaps because this was home. Alighting from the cars amidst thousands of people who thronged the platform and streets, the soldiers were met by a committee, relatives, and friends, and it was with great difficulty that the horses provided for the troopers were reached. As each man swung into the saddle, the famous old Liberty Band struck up a march, and as the procession, consisting of the Band, Reception Committee, Clergy, Grand Army, National Guard, Police, Fire Department, Secret Organizations, and others, turned into the main street of the city, a burst of exultation extolled the welcome home, and as the line of march advanced between thousands of people under a bower of phosphorescence it was with a keen sensibility of delight that we had lived to enjoy such a unique and prodigious reception. A sumptuous banquet was tendered the cavalrymen in the spacious dining-hall of the Central Hotel, where addresses and toasts were made by prominent Hazletonians, terminating a successful campaign of the “Governor’s Troop.” After the expiration of the two months’ furlough, this troop of cavalry was mustered out of the service of the United States.

Admiral’s Orderly on the U. S. Cruiser New York—A Storm on the Atlantic—Duties of a Marine—The Author Reads his own Obituary—Under the Guns of Gibraltar—A Bull-fight in Spain—Pressing an Indemnity Against the Sultan of Morocco—An American Subject Burned at the Stake by Moors—Burial in Morocco of a Shipmate.

The Boxer outbreak in China in 1900 attracted the attention of the entire civilized world, and was the incitement that inspired many of an adventurous turn of mind to cast their fortunes with the allied forces in suppressing the depredations of the Tartar tribes in the land of the Heathen Chinee. In August, 1900, while a spectator at the Corbett-McCoy bout, in “Madison Square Garden,” New York, I learned, from a chief petty officer of the battleship Massachusetts, that the United States cruiser New York, lying in dry dock at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, was being rapidly prepared to be put in commission, and was to be the “flag-ship” of Rear Admiral Rodgers, who was destined for a cruise to the Chinese coast. Upon further inquiries at the Navy Yard, I heard this news authentically corroborated, and at once determined to see the Orient.

A battalion of marines under the command of Major Waller had won laurels in Tien Tsin and Pekin, being among the first to enter the Forbidden City. Keeping tabs on the daily progress of the war, I became more and more interested, and, having learned that marines were the first landing force during hostilities, I enlisted in this branch of the service, and ere long was installed in the “Lyceum” of the Brooklyn Navy Yard operating telephone switches. From my window in the “Lyceum” I could gaze on the sailors who were rapidly putting the big cruiser in readiness for her cruise around the world; for, contrary to expectations, the order to proceed direct to China was abrogated in lieu of an indemnity which required pressure in Morocco.

Having made application for the “marine guard” of the New York, which consisted of seventy-two men, one captain, and one lieutenant, I was very much pleased when informed that my application had been approved of, and that I was to prepare to board the vessel in the capacity of “orderly” to the admiral. I was relieved from duty in the “Lyceum” and ordered to join the “guard,” which had been undergoing a process of special drill.

On being ordered aboard the ship, we were assigned to quarters, instructed as to our stations for boat drill, fire drill, large gun drill, abandon ship, arm and away, strip ship for action, collision drill, and the positions of alignment on the quarter-deck, where the “present arms,” the courtesy extended to military and civil dignitaries at home and abroad, had to be daily executed.

The New York, which had been the “flag-ship” of Rear Admiral Bunce, who commanded the “North Atlantic Squadron,” and later the “flag-ship” of Rear Admiral Sampson at the battle of Santiago, was in 1900 the show ship of the navy, making a magnificent appearance while under way. She carried a complement of six eight-inch guns, twelve four-inch, and ten six-pounders, and had a speed of more than twenty-one knots per hour.

A feature of the New York was her enormous engine strength compared with her weight, the battleship Indiana developing nine thousand horse-power on a ten thousand two hundred ton displacement, while that of the cruiser New York was seventeen thousand horse-power on a displacement of eight thousand two hundred tons.

The day having arrived for placing the vessel in commission, a galaxy of army and navy officers, civilians, and beautiful women assembled on the quarter-deck, which was inclosed and draped with flags of all nations. Orderlies were kept busy announcing the arrival of the guests to the admiral and captain, many of whose names included exclusive members of New York’s “Four Hundred,” whose ancestral genealogies, emblazoned with ensigns of heraldry, adorn their multitudinous—what not?—though ofttimes, let it be known, the power and honor behind the throne can be traced to the purchasing power of filthy lucre. Not unlike the “Sons and Daughters of the Revolution,” whose sacred heritage and portals have been defiled by the presence of incognizable descendants of ancestors who in reality were unloyal to the colonies, Tories of King George III., some of whom sat in that august body the “General Assembly” and cried Treason! Treason! as Patrick Henry introduced his famous resolutions in denunciation of the Stamp Act, and in a passionate burst of eloquence uttered those never-to-be-forgotten words, “Cæsar had his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell, and George the Third”—pausing awhile during the interruption by Tories, calmly added—“may profit by their example.”

Wafting adieu to old New York town, our sea-going home steamed out of New York harbor and down along the Atlantic coast to Hampton Roads, our first stop, anchoring midway between Fortress Monroe and the “Rip Raps,” where tons of coal were placed in the bunkers.

Coaling ship is the most disagreeable work a sailor can perform, but, as the task is usually accomplished in one day, each man tackles the work with that heroic resolve which has so characterized the American “man-of-war’s-man” in battle.

Immediately after coaling, the ship is thoroughly cleansed from truck to kelson; the decks are holy-stoned and the berth deck is shackled, after which the men take a thorough shower-bath, don immaculate uniforms, and all has the refreshing appearance of a swan on a lake.

The essential duty of a “marine” on board a ship is to preserve order; he fulfils the position of both sailor and soldier, and, while he is sometimes dubbed a leather-neck, on account of his tight-fitting uniform, by his more aquatically uniformed shipmate, it is nevertheless noticeable that he is the first to cross the gang-plank when there is trouble in the wind; and the number of “medals of honor” and “certificates of merit” that have been awarded to marines since 1898 is the mute indubitable evidence of his fidelity and bravery; however, this is not to be construed in any way to detract from the loyalty of our brave “Jack tars.”

Our ocean voyage from the Atlantic coast to the Fortress of Gibraltar was beset with difficulties, due to a severe storm we encountered the second day out, in which one of our cutters or life-boats was washed away. This it seems was picked up by a “liner” en route to Havre, France, and, as we were four days overdue at Gibraltar, it was believed that the cruiser had gone down with all on board. Some time later along the African coast, it was amusing to read, in the Paris edition of the New York Herald, our own obituary, and to see the picture of the “flag-ship” and her crew going down to “Davy Jones’s locker.”

The storm abated as we came in sight of the Madeira Islands, but, owing to our being overdue at the “Rock,” we were compelled to pass this beautiful place without stopping. The voyage from the Madeiras to the straits was quite calm, and we were again able to eat soup without the aid of a dipper.

When off duty I spent a great deal of time playing chess and reading. We had an excellent library stocked with the best editions from the pens of the most famous authors; besides a piano and excellent performers, among these being the ship’s printer, E. Ludwig, well known prior to his enlistment by the author.

As outlines of the “Pillars of Hercules” appeared on the horizon, it was evident that in a very few hours we would be plowing the waters of the great Mediterranean Sea. The quartermaster and signal-men were busy getting their signal-flags in shape, ammunition was hoisted for the salute, and the marine guard and band were busy policing themselves for the part they had to play in entering a foreign port.

Passing through the Straits of Gibraltar, which separate the mainland of Europe and Africa, we beheld, looming into the clouds, the most magnificent and impregnable fortress of the world, Gibraltar.

As we entered the bay of Algesiras, the huge guns of the fortress and battleships of various nations belched forth an admiral’s salute of thirteen guns; these were responded to by the American “flag-ship.”

Gibraltar is an impregnable promontory fortress, seven miles around at the base, and forms the southern extremity of Spain. It is fourteen hundred and forty feet high at its highest point, is studded with disappearing guns, and its honeycombed caverns contain munitions of war for a campaign of many years.

The population of Gibraltar is composed of English, Spaniards, Jews, and Moors. A causey separates the town from the mainland of Spain. The British side is patrolled by British soldiers, who are so close to the Spanish sentries that the challenge can be heard at night by either side.

We remained in Gibraltar ten days, and had the pleasure of meeting a large number of English soldiers and sailors at the “Royal Naval Canteen,” where we swapped stories over a can of “shandy gaff,” which is a mixture of stout and ginger ale.

At the solicitation of some of the soldiers of the Royal Artillery, we Americans accompanied them to the town of Algesiras, in Spain, to witness a bull-fight. Engaging passage to a point of landing about five miles across the bay, we embarked with a pent-up feeling of excitement, overly eager to see the gay Castilians in their holiday attire turn out en masse for their national sport.

On our arrival in town, we found business practically suspended, and all making their way to the arena, which was enclosed by a high board fence. On being admitted, we at once became objects of considerable scrutiny, as the war fever had scarcely died out.

Venders were busy disposing of their wares; senoritas, gayly bedecked in flowers and loud colors, seemed to bubble over with enthusiasm; horsemen galloped through the enclosure, and bands of music thrilled this novel audience with inspiration. As we took our seats and patiently awaited the onslaught, a sickening silence cast its pall over this picturesque assemblage. This was momentary, however, as a blast from a bugle was followed by the entrance of the alguazil and mounted toreadors in costumes of velvet; the arrival of these gladiators of the arena was heralded with a tumult of cheers, which became deafening as the gate was thrown open and the bull rushed in.

Mounted picadors were stationed in various parts of the arena, whose duty it was to infuriate the animal by thrusting banderillas, or spikes with ribbons attached, into the animal’s shoulders, others waved robes or capes for the same effect. Charge after charge was made on the matadore, who gracefully side-stepped the attack and awaited the return of the bull, which had become frantic from the sting of the banderillas.

The last charge is made with defiance, but alas! is met with the undaunted courage of the matadore, whose fatal blade reaches a vital spot, adding another victory to his list of successful combats. “Bravo! Bravo!” yell the maddened crowd, as the victor is showered with compliments and carried from the arena. Preparations immediately follow for a continuance of this semi-barbaric sport, and in like manner each encounter was attended with the same skill of the matadore and enthusiasm of the spectators.

On leaving the arena, it was with little wonder at the Spanish for their marked devotion to this their national sport, as it proved to be exceedingly fascinating and fraught with great excitement.

On our return to Gibraltar we journeyed to the naval canteen, where sailors and marines of the British battleships Endymion and Ben-bow were laying the foundation for a session of joy, the Boer war being the chief topic of discussion.

During the day the Governor-General of Gibraltar, Sir George White, whose appointment had recently followed his winning the “Victoria Cross” while in command of troops in South Africa, had been entertained on board the American ship, in company with other notables of the army and navy.

After the ship had been coaled and various stores taken aboard, anchors were weighed and the vessel steamed for Morocco, a sultanate on the northwest coast of Africa. On reaching the straits the signal was given to strip ship for action, all unnecessary impediment was removed from the gun-decks and superstructure, awnings were furled and secured by gasket, spars and davits lowered and all secured in places of safety, while the big eight-inch turret guns free from tompions were trained abeam or at right angles to the ship’s keel.

On entering the harbor of Tangier, the customary salute was fired; this was answered by the crumbling old forts of the Moors, relics of the Dark Ages and monuments of antiquity.

As the cruiser anchored with her starboard battery trained on the city, it was evident that the visit was of far greater import than that of a mere social call.

The pressure of an indemnity is a matter of deep concern, the wilful disregard of which is usually followed by hostilities. When one sovereign nation calls on another sovereign nation to apologize, the first nation is expected to resort to arms if the apology is not forthcoming. Though not representing a sovereign nation, the mission of the New York in the harbor of Tangier was clearly perceptible as an expounder of a precedent.

The grand vizier of the Sultan of Morocco had made himself obnoxious to America by refusing an interview with Mr. Gummere, United States consul at the port of Tangier. For this discourtesy and other claims of the United States long pending against the government of Morocco, it was found necessary to despatch a war-ship to put pressure on the Moors.

The history of the conflicts between the Moors and the United States had covered a period of more than one hundred years, dating back to the naval wars of the infant nation with the Mediterranean pirates. Discriminations against Americans and interference by officials of the Sultan with Americans doing business in Morocco were largely due to the ignorance of the Moors as to the power of the United States.

Claim after claim was ignored by the Sultan. In 1897, in order to bring this sublime potentate to a realizing sense of the importance of recognizing the demands of the United States, the United States cruisers Raleigh and San Francisco, in command of Rear Admiral Selfridge, were ordered from Smyrna to Tangier for the purpose of lending support to Consul-General Burke. This act had its effect, as promises were given that in the future discriminations would be eradicated.

In June, 1900, however, the strife was renewed when Marcus Ezegui, who was a naturalized American citizen and manager of the Fez branch of the French firm of Braunschweig and Co., while riding horseback through a narrow street in Fez, jolted against the mule of a Moroccan religious fanatic; a dispute ensued, the crowd siding with the Moor. In self-defence Ezegui drew his revolver and fired, wounding a native. This was the signal for a general attack on the American; he received a dozen knife wounds, and was burned at a stake before life had become extinct.

For this atrocious crime the United States asked an indemnity of $5000 and the punishment of the offenders; the request received little adherence by the Moorish government; then the State Department demanded $5000 for the failure of Morocco to punish the offenders.

After much diplomatic correspondence between Washington and Fez, the Moroccan capital, the United States battleship Kentucky was ordered across the Atlantic to procure the necessary demands. In this she was partially successful, though failing to negotiate the demands in their entirety. Time dragged on and promises remained unfulfilled. The capital was moved time and again between the cities of Tangier and Fez purposely to evade negotiations with the United States. It remained for the New York to consummate a successful issue, in the undertaking of which she was ably commanded by Rear Admiral Frederick Rodgers, whose iron-willed ancestors had bequeathed him a priceless heritage,—the courage of his convictions combined with executive diplomacy.

On the reception of Consul-General Gummere by the admiral, it became known adventitiously that the grand vizier of his Sultanic Majesty, in company with the Sultan, had departed for the city of Fez. This they called moving the capital. With the afore, aft, and waist eight-inch “long toms” trained idly on the city and forts, Admiral Rodgers, with flag-officers and escort and accompanied by Consul Gummere, departed on a small British yacht for the city of Fez, with the determination to promulgate his mission to his excellency’s government,—namely, its choice of a satisfactory adjustment of the indemnity or the unconditional alternate: a bombardment. It is needless to say that this was the final negotiation, terminating with a successful and honorable issue.

A member of the ship’s crew having crossed the “great divide,” permission for the obsequies and burial in Tangier was granted. In a casket draped with the American colors, the body was conveyed by launch to the beach, where pall-bearers, members of the departed sailor’s division, took charge of the conveyance to the cemetery. With muffled drums the band led off, playing a solemn funeral dirge, followed by the procession, which included an escort of honor and firing squad of marines.

A circuitous route of three miles through narrow streets, with buildings crumbling to decay and indicative of architecture of an early period, led us to the cemetery on a shady plateau near the outskirts of the city. Here the cortege halted, and the last rites were solemnized by Chaplain Chidwick of the New York, well known as the late chaplain of the ill-fated battleship Maine. Three volleys were fired over the sailor’s grave, and the services closed impressively with the sound of “taps,” “lights out.”

As the band struck up “In the good old summer-time,” ranks were broken, and the men roamed at will through the narrow, spicy-scented streets, thronged with semi-barbarians, rough-riding vassals of the Sultan costumed in turbans, sandals, and flowing robes, whose contempt for all foreigners cannot brook restraint. It was a pleasant relief to escape the fumes of this incensed city, to inhale the fresh ozone aboard the man-of-war.

On departing from Morocco, our cruise led to ports along the coast of the great Mediterranean Sea.

Moonlight on the Mediterranean—Meeting with O’Mally, a Pedestrian of the Globe—“Birds of a Feather” in the Moulin Rouge—A Midnight Hold-up by Moors; O’Mally with Gendarmes and French Soldiers to the Rescue—A Pitched Battle in which Blood Flows Freely—French Soldiers Drink the Health of the United States—Malta and Singers of the “Yama Yama.”

A calm moonlight night on the waters of the Mediterranean Sea is the most awe-inspiring feeling that can be manifested in the heart of a man-of-war’s-man. The dark blue billows, resembling a carpet of velvet, surging in mountainous swells, seem to reflect the glitter of every star in the celestial firmament, while moonbeams dance in shadowy vistas o’er the surface of the deep. It was on such a night that our cruiser plowed her course from Palermo, Sicily, and entered the land-locked harbor of the quaint old capital of Algeria.

I can vividly remember the embodiment of contentment with which I was possessed as I leaned on the taffrail of the ship and beheld the illuminated city of Algiers, rising from the water’s edge diagonally to an immense altitude.

Life-buoys dotted the harbor, and a small light-house played a search-light to our anchorage. After the anchors had been cast, booms spread, the gig, barge, and steam-launches lowered, the deep stentorian voice of the boatswain’s mate could be heard through the ship, piping silence about the deck; taps had been sounded, and all except those on duty were supposed to be swinging in their hammocks.

With the loud report of the morning gun could be heard “Jimmy-legs,” the master at arms, as he made his way through the berth-decks, singing his daily ditty, “Rise, shine, and lash up.” This, repeated rapidly for a period of five minutes, was likened unto a band of colored brethren at a Georgia camp-meeting hilariously singing, “Rise, shine, and give God the glory, glory,” et cetera. In fifteen minutes every hammock had to be lashed according to navy regulations and stored away in the hammock nettings.

After breakfast in port, every man must appear military. Uniforms must be pressed, buttons and shoes polished, and accoutrements ready for inspection, for at eight bells the colors are hoisted, the National air is played by the band, and visits of courtesy commence between the various fleets and shore officers.

The ship’s band renders music three times daily in port, and visiting parties are conducted through the ship. A large number of bum-boats, with their venders of fruit and curios, always surround the ship; these people are an interesting class and present a picturesque scene, with their quaint costumes, noisy chatter, and cargo of varieties.

As in all other ports, the men entitled to “liberty” (a word used to designate shore leave) make their preparation early, then await the noon hour, when the boatswain’s mate pipes his whistle, and cries out: “Lay aft all the liberty party.” All going ashore fall in, in double rank on the quarter-deck, where they answer their names and pass down the gangway and into boats, in which they are conveyed ashore, where the boys cut loose from discipline and nothing is too good for “Jack.”

On our first day in the harbor of Algiers I was on duty, and among other announcements I had to make to the admiral was the announcement of one Mr. O’Mally, a pedestrian from San Francisco, California, who desired an interview with the admiral of the flag-ship New York.

Mr. O’Mally was walking around the world for a wager; he had covered the distance from San Francisco to New York, had walked through Europe, and was at this time making his way through Africa. He had come on board the American ship to have Admiral Rodgers sign his credentials showing he had been at this point in Africa on this particular date. At the close of the interview the admiral ordered me to show our distinguished perambulator through the ship. I found him to be a very congenial fellow, and was very much interested with his stories of his travels by foot.

Accompanied by his French interpreter, we started through the vessel, I explaining everything of interest to their apparent satisfaction, after which we returned to the quarter-deck, and, after exchanging cards, Mr. O’Mally and his guide departed for the city, stating that he would probably meet me in Algiers the following day, where I would be on shore leave.

The next day, accompanied by five other marines, with that almost uncontrollable desire for pleasure and excitement known only by the men who undergo the rigid discipline of the navy, I boarded a sampan and was sculled ashore, where numerous guides, always in evidence in foreign ports, offered to conduct us through the labyrinths of gayety. Waving aside these pests, we ascended the stone steps leading to the plaza overlooking the bay and a grand boulevard. This plaza was thronged with pedestrians and equipages of the civic and military, French and Moorish officers, gendarmes, tourists, fakirs, fortune-tellers, Bedouins, and beggars, commingled, forming a most cosmopolitan scene. Seeking an exchange, we converted some money into centimes, sous, francs, and napoleons, and, after purchasing some relics from the bazaars, engaged landaus and proceeded to see the sights of this quaint African city.

Arabs, Moors, Spaniards, Jews, French, Germans, Maltese, and Italians—in fact, every nationality extant—seem to be represented here.

The City of Algiers was built about 935 A.D., was poorly governed by a long succession of Turkish deys, and fell under the yoke of French rule in 1830, obliterating the despotism which had long existed.

The Boulevards, beautifully adorned with arcades and lined on either side with orange and lime trees, are the scenes of magnificent equipages drawn by blooded Arabian horses.

The heat, though at times intense, is mitigated by a delightful cool sea-breeze.

The principal places of interest are the French bazaars, the Catholic cathedral, the hot baths of Hammam Phira, the marketplace, casino, public bath, coffee-houses, theatres, bank, quarters of the soldiers of the foreign legion, the Moulin Rouge, identical with the famous “Red Mill” of Paris, where “birds of a feather flock together,” and where L’amour et la fumee ne peuvent se cacher.

Discharging our landaus, we journeyed through the Rue Bab Azoun, passing here and there groups of French and Moorish soldiers, and occasionally brushing against women of the true faith, whose veils hide many a beautiful face.

In the cabarets or cafés which line the plazas, French soldiers can frequently be heard singing the national air of France, the “Marseillaise.” The cosmopolites who comprise the foreign legion are an interesting body of soldiers, representing all nations, but serving under the dominion of the French government. Entering a cabaret where a game of roulette was in progress, we marines took a chance on the roll of the ivory ball, in which some of the party increased their wealth considerably. About every fourth turn of the ball, wine was dispensed. I had been very lucky in my play, having several times picked the number, column, and color at the same time, to the great disgust of the croupier, whose radiant smile beams only when the wheel wins.

As conversation had become boisterous and my luck had taken a sudden turn, I cashed in, and, after thanking the croupier for his kind donations, whose smile portrayed a feeling of derision, I made my exit.

After depositing for safe keeping, in one of the leading hotels, numerous curios and several hundred dollars in French currency, I roved at random through the city without any special point of direction.

Having heard a great deal about the interesting sights to be seen in the “Kasbah,” the Moorish quarter, which is the ancient fortress of the deys and commands a view of the city from a height of five hundred feet above sea level, I ventured to this weird section of the city. Climbing the long winding stairway, or steps of stone, I soon found myself encompassed by a collection of wild-looking Moors in flowing robes, turbans, and sandals, the women similarly dressed, whose veiled faces showed only their eyes, and the artistic tattooing in the centre of their eyebrows, pranced through dimly lighted lanes, like Rip Van Winkle’s hobgoblins of the Catskills.

Being unable to hold conversation with these barbarians, I contented myself with being a silent spectator of their grotesque actions.

After making the rounds of various places of interest, where it was distinctly obvious that I was an unwelcome visitor, I decided to return to the better-lighted and more civilized plazas of the city. As I tried to figure out my bearings on an imaginary compass, I became bewildered, and in consequence followed any street which had an incline.

From the main street of the “Kasbah” are numerous short streets or lanes, which seem to have no connection with other streets, terminating at the entrance to a building. I had tried various ways to reach the steps I had climbed, without success, and here realized the importance of having a guide or an interpreter. Finally I sighted the rays of a search-light, and later a light on the mainmast of a merchant marine entering the bay. Following in the direction of this light, I reached a badly lighted portion of this section of the city overlooking a precipice, when, without a semblance of warning, my arms and feet were pinioned, I was gagged with a roll of hemp, which was placed under my chin and drawn taut around my neck. I made a desperate struggle, but was helpless without the use of my arms, and was compelled to yield when a blood-thirsty brigand placed the point of a dirk against the spring of my affections,—namely, the region of my solar plexus; and it is needless to say that “to slow music” I was relieved of my personal possessions, including my watch, chain, finger-ring, keys, money, letters, and trinkets, by six Moorish brigands, who kindly refrained from casting me over the precipice. As they broke away, I was left to ponder in amazement.

It was absolutely futile for me to think of an attempt at anything except that of securing myself and reaching the heart of the city. At this juncture, and to my great surprise, I was delighted to see, coming out of one of the narrow streets, my friend Mr. O’Mally the pedestrian and his interpreter. Recognizing him instantly, I informed him as to what had happened, which brought a cry from his interpreter for the gendarmes and soldiers. In a few moments the soldiers and police had arrived, and I led them in the direction the bandits had taken, but at night it is impossible to distinguish one Moor from another, for like Chinese they all look alike at night; therefore, the soldiers contented themselves in beating them indiscriminately, as the Moor is the French soldier’s bitterest enemy.

These soldiers, unlike the American soldier, carry their side arms when off duty, and it was with great difficulty that the gendarmes prevented some of the Moors from being killed. At one stage of the game we had a battle royal, and there are a number of Moors in the “Kasbah” who carry scars as evidence of this night’s fracas.

On our return to the plaza, I discovered that besides leaving the buttons on my blouse the robbers had overlooked two gold napoleons which I carried in the watch-pocket of my trousers, and, as the French soldiers were not averse to accepting a potion of wine for their services, it was not long before we were drinking to the health of the United States and the French Republic.

Mr. O’Mally and his guide left the party in the “wee sma” hours of the morning, and, as three years intervened before my return to America, I lost all trace of this interesting gentleman.

Next day while returning to my ship, I received the intelligence that the other marines who had accompanied me ashore had fallen into the hands of the gendarmes for destroying the roulette-wheel and creating a general “rough house,” due, they claimed, to crooked work on the part of the croupier. Later in the day on paying a small fine they were released.

Our stay in Algiers covered a period of ten days, which included Easter Sunday. This was a gala day on the plazas and along the Boulevard; the services in the French cathedral were performed with great pomp and ceremony; flowers were banked in profusion, while the singing of the choir was decidedly of a rare quality.

Before leaving this memorable city I had the pleasure of attending a French masquerade ball in the Rue de Rome, where Parisian dancing novelties were introduced and where fantastic costumes had no limit.

The last day in Algiers was given to a reception, aboard the ship, to the foreign legations. As usual on these occasions, the ship was gayly decorated with flags of all nations. Easter lilies, which had been presented to the admiral by Algerians, fairly covered the quarter-deck. Dancing continued throughout the evening, the guests departing at midnight to the strains of the “Marseillaise.” A few hours later anchors were weighed, and, under a beautiful pale moonlight, our cruiser steamed out of the harbor, carrying with it everlasting memories of the picturesque City of Algiers.

After a cruise of four days the Island of Gozo was sighted, and ere long we had entered and anchored in Valetta, the capital of Malta. A large British fleet lay anchored here, also a yacht having on board his royal personage “The King of Siam,” who was making a cruise of the Mediterranean Sea. “The Duke and Duchess of York,” on board the Ophir bound for Australia, for the opening of Parliament, was also sighted in the Mediterranean Sea.

The Island of Malta is of Arabic origin, but at present an English possession. It is frequently mentioned in Biblical history, having been conquered by the Romans two hundred and fifty years before the birth of Christ.

Near the City of Valetta a spot is pointed out as having been the place where Paul the Apostle’s ship was wrecked.

I heard Captain McKenzie of the New York remark to the admiral that Malta is the only place where a Jew cannot prosper, as a Maltese will beat a Jew.

The principal sights of Malta are the Strada san Giovanni in Valetta, a wide stone stairway lined on either side with buildings of ancient architecture, the ruins of a Roman villa and the Beggar’s Stairs. The Maltese are a musically inclined people, and at night it was very inspiring to hear the young people, as they coursed around the ship in “gondolas,” singing selections from the famous “La Traviata” to the accompaniment of mandolins and guitars, invariably offering as an encore, the ever beautiful, Venetian “Yama Yama,” famous for ages along the shores of the Mediterranean Sea.

It was with regret that Alexandria, our next port, was to end our cruise on this magnificent body of water.

The Pyramids of Gizeh—The Sphinx—A Famous Relic of the Honeymoon of Cleopatra and Mark Antony—Cairo—Camel Caravansary en route from Syria to Cairo—Suez Canal—Red Sea—Mt. Sinai—Aden—A Monsoon in the Indian Ocean—Singalese of Ceylon—Singapore.

On the arrival of our ship at Port Said, Egypt, the haven of beach-combers and the most immoral city on the face of the earth, preparations were at once made for coaling ship. Lighters loaded with coal were towed alongside, and natives of the Nubian Desert relieved the crew of this detestable task. Men were granted liberty with the privilege of visiting Jerusalem or Cairo. It being necessary to travel by boat a long distance to Jaffa in order to get a train for the Holy Land, I decided to spend the time in seeing the sights of Cairo, the Pyramids, Sphinx, and the Nile.

Securing transportation, I boarded a train for the Egyptian capital; not a very pleasant trip, however, as the heat was intense, and thick gusts of dust were continually blown from the Sahara and Nubian Deserts.

The first novel sight that met my gaze was a camel caravansary with a band of Arabs on their way from Cairo to Syria. Upon entering the city, the Arabic architecture was the first to attract my attention, the mosques and minarets particularly appearing prominent. The streets were thronged with tourists of all nations; camels wending their way and donkeys for hire or sale at every corner gave the city the aspect of the “Far East.”

I visited the Sacred Gardens of the “Howling Dervishes,” the tombs of the Caliphs, an ostrich-breeding house, “Wells of Moses,” the mosque of the Sultan Hassan, and several museums containing relics of priceless value dating back to dynasties before the birth of Christ.

In Shephard’s Hotel, Napoleon’s headquarters during his campaign in Egypt, I saw, guarded with jealous care, the magnificent catamaran or gondola in which the Egyptian Queen Cleopatra cruised the Nile during her ostentatious honeymoon with Mark Antony.

After visiting the citadel and places of less interest, I journeyed to the streets where the music of the tomtoms was attracting attention. The shades of night having fallen and my appetite being keen, I sauntered into an Arabian café for dinner, where a string of Egyptian dancers amused the guests with the muscle-dance, far surpassing “Little Egypt” or “The Girl in Blue.” These dancers are serious in their art, and to snicker at them is to manifest ridicule and is considered an unpardonable breach of manners.

After my “Seely dinner,” every course of which was served quite warm, I repaired to my hotel and retired for the night.

The following day I engaged a hack and journeyed across the grand bridge of the Nile to the Pyramids and Sphinx. These landmarks of prehistoric ages, seventy in number and considered one of the seven wonders of the world, can be seen from a great distance looming up in the desert.

The Pyramids of Gizeh, on the west bank of the Nile, are the largest of the group. The first or Great Pyramid covers thirteen acres at the base, and is nearly five hundred feet high; it is honeycombed, and contains the remains of the ancient rulers of Egypt. One hundred thousand men were employed thirty years in its construction.

Following our guide through the cavernous catacombs, we finally reached the sarcophagus of Cheops, who ruled Egypt twenty-five dynasties before the Christian era. After a random tramp of more than an hour through this dreary dark abode, we returned to the light of day, and, climbing the Pyramid, reached a point from where Napoleon reviewed his troops after his campaign against the Mamelukes.

Lying three hundred feet east of the second Pyramid is the colossal form of the Sphinx, hewn out of solid natural rock, having the body of a lion with a human head. It is one hundred and seventy-two feet long and fifty-six feet high. The Sphinx was symbolic of strength, intellect, and force, and thousands of Egyptians were employed twenty years in its construction.

Having spent two days of most interesting sight-seeing in this old historical city, I returned to the cruiser, and after remaining a few days in the harbor of Port Said, commenced our journey through the Suez Canal.

This canal, which connects the Mediterranean and Red Seas, was built by Ferdinand De Lessepps, a Frenchman. France built the canal, but England owns it, although she permits Frenchmen to run it. The idea originally was not De Lessepps’, as there had been a canal connecting the Mediterranean and Red Seas thirteen centuries before Christ. When Napoleon was in Egypt, he also entertained the project, in order that France might supplant England in the eastern trade; but it required the indomitable courage and wonderful genius of De Lessepps to carry the herculean task to triumph.

The work was begun in 1860 and finished in 1869. One hundred million dollars were spent, and thirty thousand men were employed in its construction. The canal is eighty-eight miles long, twenty-six feet deep, one hundred feet wide at the bottom, and about three hundred feet wide at the top. The waters contain three times more salt than ordinary sea water. There are stations along the route where ships tie up to permit ships going in an opposite direction to pass. Its course lies through the Nubian Desert, the land which Pharaoh gave to Joseph for his father and brethren. An occasional drawbridge is in evidence where the caravansaries cross going to and coming from the Holy Lands.

A novel sight midway in the canal was a French transport loaded with French soldiers returning from the Boxer campaign in China. Vociferous cheering from the Americans was responded to by the Frenchmen.

After ploughing the waters of the Suez Canal, our ship entered Bitter Lake, where we anchored for the night, departing on our voyage at the break of dawn. Entering “The Gate of Tears,” a strait between Arabia and the continent of Africa, and so called from the danger arising to navigation caused by strong currents, we beheld the entrance to the Red Sea. The Twelve Apostles was the first memorial to remind us of the historical chronology of this broad body of water. These “apostles” seem to be of mysterious origin; they consist of twelve symmetrical columns of rock, which project from the sea in a straight line, the same distance apart, and shaped identically alike. Not far from the coast on our port side could be seen Mt. Sinai and Mt. Horeb, famed in biblical history. Some distance beyond is Mecca, the Jerusalem of the Mohammedans, near which a spot is pointed out as being the place where, under the providence of God, the Red Sea was divided, making a dry pass for the deliverance of the Israelites from their bondage in Egypt, under the leadership of Moses, the God-inspired liberator of his people.

Steaming by Mocha, celebrated for its production of the finest coffee in the world, we entered the harbor of Aden, our first port in Arabia. Aden is a city typical of the “Far East”; spices of a rich odor permeate the atmosphere for miles from the coast. The city is built in the crater of an extinct volcano, and has an altitude of one thousand feet, is strongly fortified, and commands the trade to India. Arabs engage in trade of all kinds; beautiful ostrich feathers, Bengal tiger skins, and ornaments of carved ivory, and souvenirs of sandal-wood are displayed in the bazaars. Aden is not the dreariest place on earth, but the few palm trees which surround the city only serve to remove it a bit from this inconceivable state.

The heat in this section of the world is intense, and, as we steamed out of the harbor of Aden, it seemed we were ploughing through molten copper; however, the nights were cool. After passing through the Straits of Bab el Mandeb and the Gulf of Aden, we entered the Indian Ocean, enjoying a delightful cool breeze; but soon encountered an interval of calm, which was followed by an East Indian “monsoon,” a veritable hurricane at sea. Engines were shut down, guns were lashed, hatches battened, and lookouts were strapped to the crow’s nest. Mountainous swells of water washed aboard the ship, and for nine hours the vessel was at the mercy of the waves. The storm having finally abated, our rigging was restored, awnings spread, and, after a few days of delightful cruising in the Indian Ocean, we entered the harbor of Colombo, the capital of Ceylon, firing the customary salute, which was returned by the forts and the various navies here represented.

Ceylon, a British possession, is an island in the Indian Ocean, lying southeast of the peninsula of Hindustan, and is covered with a rich luxuriance of tropical vegetation. The Singhalese are the most numerous of its inhabitants; they are devoted to Buddhism, the prevailing religion of the island. In Kandy, an inland town near the capital, the sacred tooth of Buddha is guarded with jealous care.

Ceylon is rich in metals, minerals, and precious stones; its gems, such as sapphires, rubies, topaz, garnets, amethysts, and cats-eye, have been celebrated from time immemorial. The interior of the island abounds with birds of paradise and immense bats resembling the vampire. Animals, such as the elephant, bear, leopard, wild boar, deer, and monkeys, roam at will, while the crocodile, tortoise, and large lizards, infest the bogs of the jungle. A celebrated mountain visible from Colombo is Adam’s Peak, which attains the height of 7420 feet above sea-level.

Colombo, the capital, a fortified city on the western side of the island, shaded by the trees of the cocoanut palm, is progressive as a maritime port and particularly as the entrepôt for the East India trade. The hotels are furnished with “punkahs,” while hammocks of rattan are stretched on every veranda.

In addition to the native Singhalese, Hindus, Tamils, Moors, Malays, and Portuguese engage in various occupations, a large number of these being employed on the coffee and tea plantations.

In the Prince of Wales Hotel I met some soldiers of the famous “Black Watch” who had participated in the Boer War and who had been sent to Colombo to recuperate; I accompanied them to their barracks, where we exchanged various curios.

A large revenue is derived by the government from the pearl-fishery in the Gulf of Manaar, and whales are captured off the coast.

Seven days were spent in the harbor of Colombo, after which our ship steamed across the Indian Ocean, and through the Straits of Malacca to Singapore, an island in the Straits Settlements, south of the Malay Peninsula, and eighty miles from the equator. It commands the highway leading from British India to China, and became a British possession by a treaty with the Sultan of Johore in the year 1824.

Singapore is the entrepôt for the trade of the Malayan archipelago and China; its chief exports are tapioca, tin, tortoise-shell, camphor, coffee, nutmegs, gutta percha, and rattan. Situated on the south side of the island, the town has a very oriental appearance, and its inhabitants represent sixteen nationalities speaking different tongues, the most enterprising of these being the Chinese. Though very warm, the climate is healthy and it is seldom subjected to quarantine.

For ages past the tiger has been a menace to Singapore, and the government’s archives record an average of three hundred Chinese and other natives carried off annually by these blood-thirsty man-eaters.