The cover image for this eBook was created by the transcriber and is entered into the public domain.

From a Drawing by Gilbert Holiday.

‘NOBODY BLUNDERED.’

[See page 110.

THE BALKAN TRAIL

BY

FREDERICK MOORE

WITH 62 ILLUSTRATIONS AND A MAP

LONDON

SMITH, ELDER, & CO., 15 WATERLOO PLACE

1906

[All rights reserved]

TO MY FRIEND

I. N. F.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Bulgarian Border | 1 |

| II. | The Road to Rilo | 15 |

| III. | The Trail of the Missionaries | 34 |

| IV. | Sofia and the Bulgarians | 49 |

| V. | Constantinople and the Turks | 68 |

| VI. | Salonica and the Jews | 82 |

| VII. | The Dynamiters | 105 |

| VIII. | Monastir and the Greeks | 134 |

| IX. | Across Country | 159 |

| X. | Uskub and the Serbs | 183 |

| XI. | Metrovitza and the Albanians | 212 |

| XII. | The Long Trail | 228 |

| XIII. | The Trail of the Insurgent | 246 |

| XIV. | On the Track of the Turk | 262 |

| XV. | The Last Trail | 277 |

| ‘NOBODY BLUNDERED’ | Frontispiece | ||

| From a drawing by Gilbert Holiday | |||

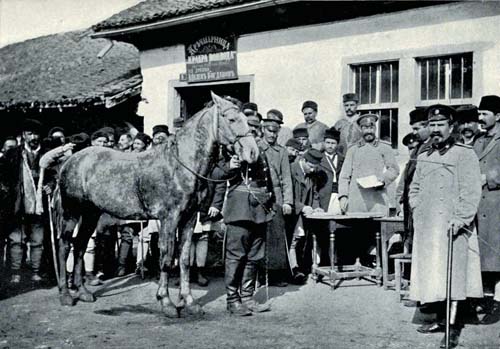

| COUNTING ANIMALS AVAILABLE FOR MILITARY SERVICE | To face p. | 6 | |

| ON A FRONTIER BRIDGE | ” | 10 | |

| THE AMAZON | } | ” | 12 |

| THE MASCOT | |||

| THE ROAD TO RILO | ” | 20 | |

| A BULGARIAN BLOCKHOUSE | } | ” | 24 |

| THE BRIDGE OVER THE STRUMA: TURK AND BULGAR | |||

| RILO MONASTERY: GRACE BEFORE GRUB | ” | 28 | |

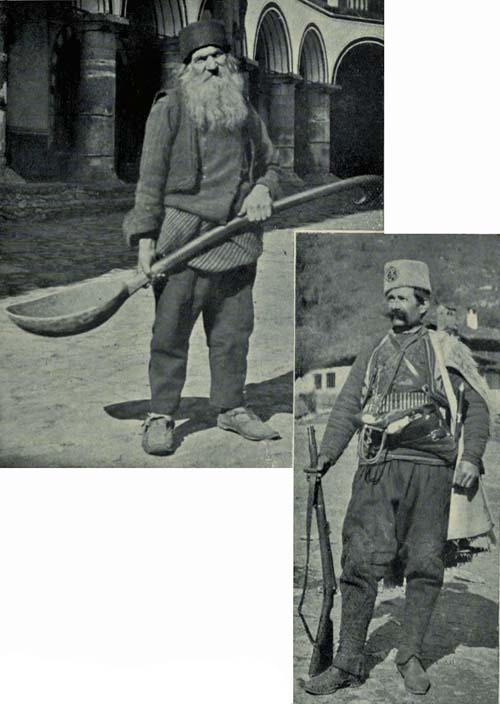

| FATHER COOK AND THE BRIGAND | ” | 32 | |

| BULGARIAN PEASANTS, SAMAKOV | ” | 36 | |

| BULGARIAN INFANTRY | ” | 48 | |

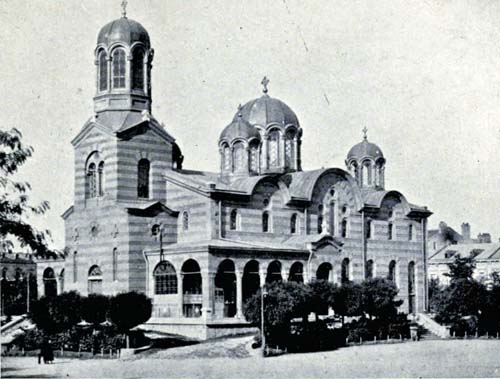

| THE CATHEDRAL, SOFIA | } | ” | 54 |

| THE BRITISH AGENCY, SOFIA: A DEMONSTRATION | |||

| A VIEW OF SOFIA, VITOSH IN THE BACKGROUND | ” | 58 | |

| ON THE MARKET PLACE, SOFIA | ” | 60 | |

| DOGS OCCUPY THE PAVEMENT; PEOPLE WALK IN THE STREETS | } | ” | 70 |

| THE TURKISH BARBERSHOP | |||

| CONSTANTINOPLE: MOSQUE OF YÉNI-DJAMI ON THE BOSPHORUS | ” | 74[x] | |

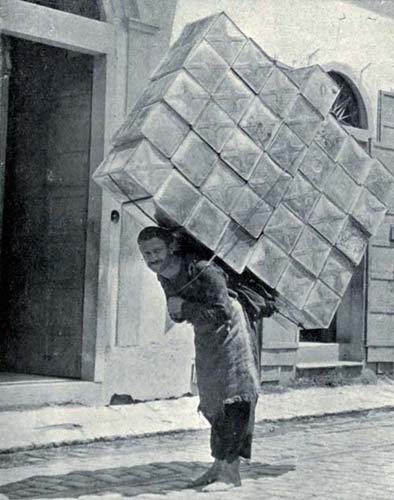

| A HAMMAL AND A LOAD OF PETROLEUM TINS | ” | 78 | |

| THE WALL AND BEYOND, SALONICA | ” | 86 | |

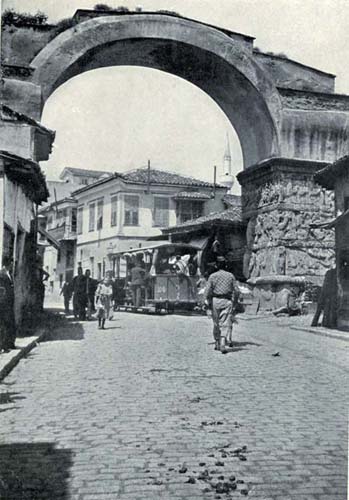

| THE ANCIENT ARCH OF CONSTANTINE, SALONICA | ” | 90 | |

| THE TURKISH BUTCHER | ” | 92 | |

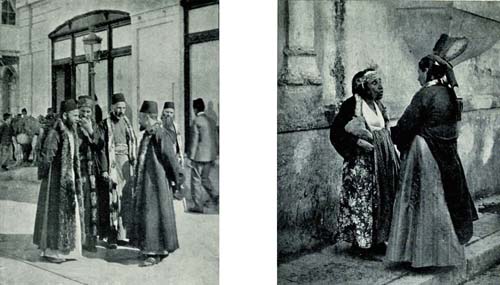

| JEWS | } | ” | 96 |

| JEWISH WOMEN | |||

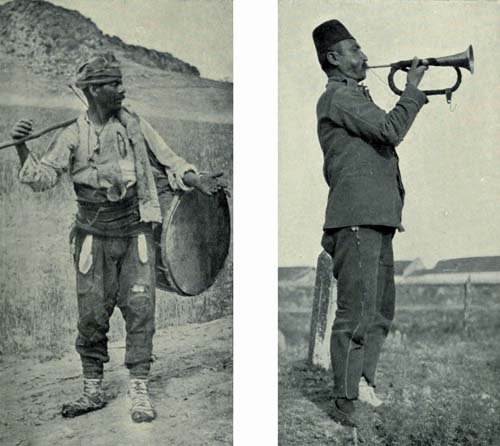

| ASIATIC SOLDIERS: ‘REDIFS’ | } | ” | 106 |

| WAITING FOR DYNAMITERS, SALONICA | |||

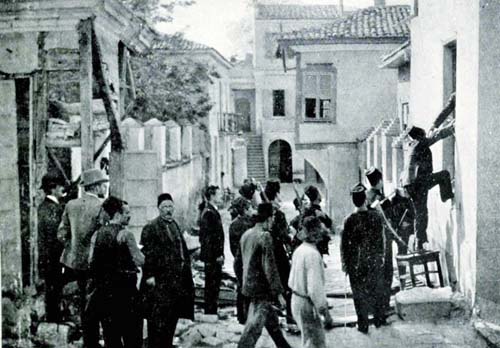

| THE WRECK OF THE OTTOMAN BANK | } | ” | 116 |

| ENTERING THE DYNAMITERS’ DEN | |||

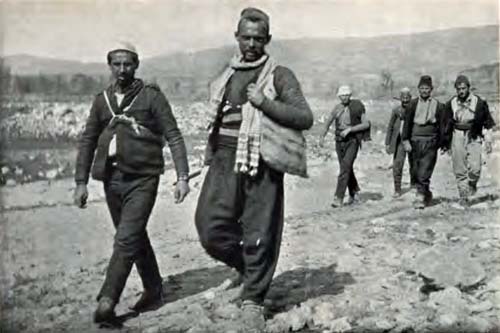

| EXILES, SHIPPED WEEKLY FROM SALONICA | ” | 126 | |

| ON A MACEDONIAN LAKE | ” | 136 | |

| A GREEK | ” | 142 | |

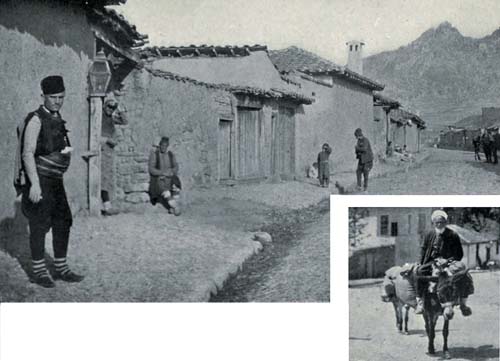

| A BIT OF OLD MONASTIR | ” | 148 | |

| ORTHODOX PRIESTS | ” | 154 | |

| CAPTIVES ALBANIANS, BULGARIANS | ” | 166 | |

| TURKISH WEDDING FESTIVITIES | ” | 168 | |

| A GYPSY MINSTREL | } | ” | 170 |

| A TURKISH TRUMPETER | |||

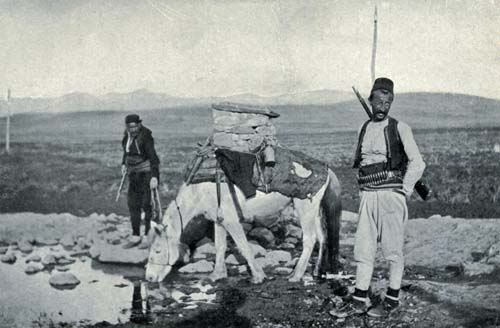

| OUR ESCORT FORDING A STREAM | ” | 172 | |

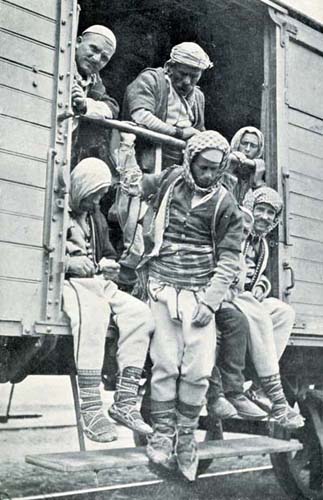

| ‘8 CHEVAUX OU 48 HOMMES’: ALBANIAN RECRUITS | ” | 184 | |

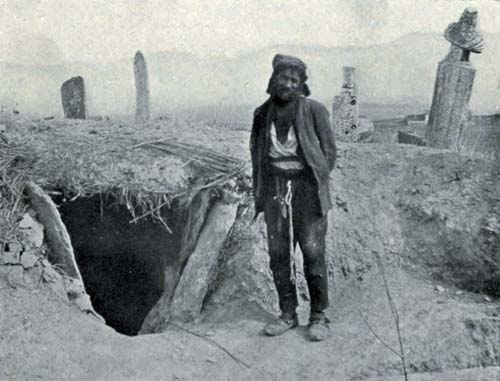

| GRAVES OF DEAD COMMITTAJIS | } | ” | 194 |

| THE OLD TURKISH SEXTON WHO LIVED IN A GRAVE | |||

| THE HORSE MARKET | } | ” | 198 |

| SWEARING TO A BARGAIN | |||

| ALBANIAN WOMEN | ” | 210[xi] | |

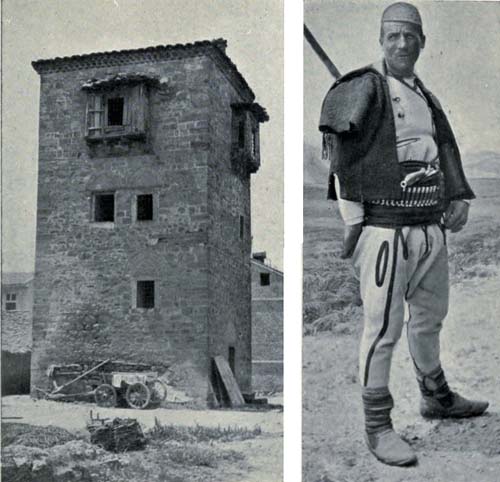

| THE ALBANIAN AND HIS KULER | } | ” | 220 |

| ALBANIAN | |||

| A GROUP OF ALBANIANS | ” | 222 | |

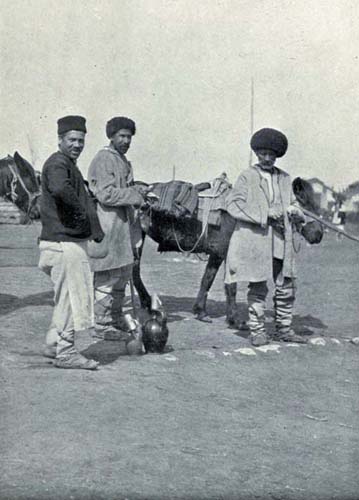

| WAYFARERS AT A ROADSIDE FOUNTAIN: TURKS | ” | 228 | |

| IN A MOUNTAIN VILLAGE: BULGARIAN PEASANTS DANCING THE HORO | ” | 236 | |

| THE TURKISH QUARTER: DJUMA-BALA | ” | 242 | |

| RUINS OF KREMEN | ” | 244 | |

| A TURKISH BAND LEAVING MONASTIR | } | ” | 252 |

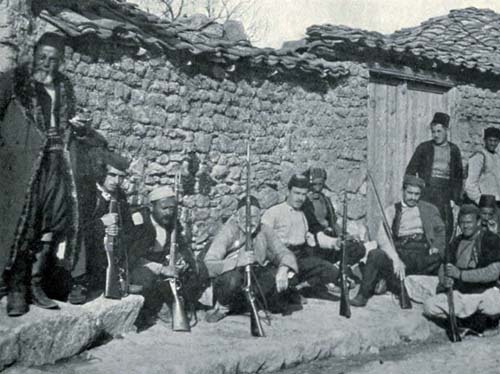

| BASHI-BAZOUKS | |||

| TURKS ON THE MARCH | ” | 256 | |

| TURKISH TROOPS | ” | 260 | |

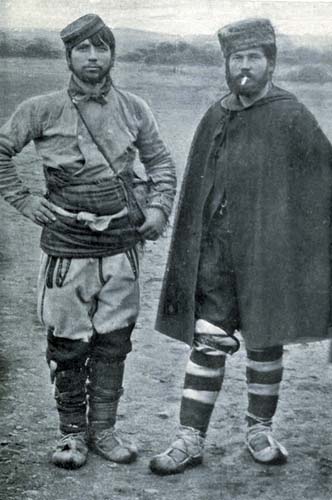

| VLACHS | ” | 266 | |

| ‘HELL HOLE,’ KRUSHEVO | ” | 274 | |

| THE MACEDONIAN | ” | 280 | |

| COMMITTAJIS OFF DUTY | ” | 292 | |

| MAP OF THE BALKANS | ” | 296 | |

Men of position are proud and prejudiced. In humble Sofia, where there is little pretence, the judge of a supreme court, whose salary was 72l. a year, declined an offer of double that wage to serve me as interpreter. An officer in the army, and other Government officials to whom I made approaches, displayed similar pride and lack of enterprise. I was bound for the border, and the only individuals willing to accompany me were two fallen stars of feeble age, in circumstances of despair; and at last I was obliged to choose between these luckless linguists. One was an anarchist, light of head and heavy of heart, the other a bankrupt viscount with a bad eye. I selected the nobleman, but a word for the anarchist; he is dead.

He was a very dirty anarchist, with long, shaggy, unkempt mane, and a hungry, haunted look. He wore a silk-lined frock coat of ample capacity, a pair of trousers of doubtful suspension, shoes in which his[2] feet flapped, a silk hat of bygone glory, no collar, no cuffs. He was of small stature, but his outfit had been created for no little man. A wonderful ‘gift of gab’ had he; in a few moments I knew his whole history. He had acquired his knowledge of English in the States, where in the ’sixties he had served (probably soup) with the Stars and Stripes when the Stars and Bars were in the field. But—and the veteran is unique in this regard—he could not procure a pension from the United States Government. Nevertheless he loved my country. He had never gone hungry there, while he had often felt the pangs in Bulgaria. What had Bulgaria done for him? Even the clothes he was wearing had been given him by an Englishman. For his country’s neglect of her travelled son, he had acquired the Irish complaint, he was ‘agin’ the government.’ He was for sending Prince Ferdinand to the hereafter, and favoured the fashionable dynamite bomb. He was a simple soul; before he could execute his plot he was sent to eternity himself—though not quite hoist by his own petard. He was shot, one bright summer evening, in the public park in front of the palace. Old Barnacle had not known David Harum’s precept, ‘Do unto the other feller what he would do unto you—but do it furst.’

Barnacle was an honest man, and he would have been faithful; all he needed to make him generous was a little success. I knew him well before he died. But in selecting my interpreter I felt compelled to act on[3] the principle that a clever crook is sometimes a safer companion than an honest simpleton.

The man with the bad eye proved to be a character with a most romantic past, a Continental count who had fallen from his high estate, but still a man of good taste—particularly for food. He, too, had been a soldier; he had commanded a company of cavalry in the Russo-Turkish war, and could still, in his age, ride me out of my saddle. But he was a Jew, and wisely, as time has proved, did not return after the war to the land of his birth. He was not a dragoman by profession, there was nothing servile about him. An English correspondent would not have tolerated his patronage. But in America, a man and his master, and a master and his man, equal pretty much the same thing; and we have heard that things which are equal to the same thing are equal to each other. No serious class prejudices hampered me, and I was content to permit my man to be my companion in a land where I could communicate direct with so few.

The Count had Bulgarian, Turkish, and Russian history, as well as all the languages of Europe, at his fingers’ ends. In view of his many accomplishments I agreed to pay him six francs a day and his living and travelling expenses. But this was not all my man got from me.

The price of a good lunch in London will keep two men for a day in Balkan country, but I did not know this when I commissioned the Count to provide a hamper of food for the first days of our journey.[4] Three loaves of bread, a hunk of Bulgarian cheese, some dried lamb, and two bottles of native wine cost him more of my money than twice the quantity would have come to in London. After the investment he dined at the ‘Pannachoff.’ I sat behind him unnoticed and watched him consume three times as much food as an ordinary man.

His string of names did justice to his characteristics, Isaac Swindelbaum von Stuffsky. He was a real count: Isaac Swindelbaum was all his card bore; an impostor in his predicament would have flaunted the title. He was called ‘count’ to his face and a ‘Russian spy’ behind his back. But he was not the latter, he was too poor. Until the correspondents came, he had lived on the meals and the drinks which tales of his exploits in the war that created Bulgaria won him from her officers.

When a man has no visible means of support in either Bulgaria or Turkey he is always labelled Spy. In Bulgaria the term is one of reproach, but in Turkey spies are looked up to and envied as among the only regularly paid servants of the Sultan. But the officers of Sofia knew that my man was not a spy. They said he was an emissary of Russia simply because he insisted that the great Slav country and Austria, allies for reform, were sincere in their desire to bring about peace in Macedonia, which none of the officers believed.

It was a run of only forty kilometres from Sofia to Radomir, but it took our train half the day to cover[5] the distance. Radomir is the terminus of the railway to the south, and about half-way to the frontier. Only one mixed goods and passenger train makes the trip to and from Sofia each day, and the line is not very profitable. If the Turkish Government would allow a junction railway to be constructed from Uskub or Koumanova up to Egri-Palanka, this road would then be continued to meet it, and all Bulgaria as well as Macedonia would reap a benefit. But the Turkish rulers like not civilising institutions.

Our train stopped now and again to pick up some peasant’s pig or waited ten minutes for a late passenger, and we had opportunity to see something of the villages at which it stopped. At one little town there was a striking scene. It was early in March; the snow on the Balkans had not yet begun to melt, and the peasants were still clad in their sheepskin coats. Before a low khan (a caravansary) were two cavalry officers and several private soldiers; and all about surged to and fro white-clad, furry peasants leading horses of all breeds and in all conditions—nags which had never eaten other feed than grass, and well-groomed, blooded beasts, bred from the special stables maintained by the Government for the purpose of improving the native stock. The officers were counting animals available for military service in case of war, and the peasants had come from miles around, eager to have their horses tried and graded.

As a result of this fair, riding horses were not to be hired when we arrived at Radomir; so we[6] negotiated for one of the customary cross-country conveyances, cast-off city carriages of all designs, drawn by numerous nags. The drivers told my Count that were he not with me they would get thirty francs a day from me. I should have thought that charge cheap. But, despite my price-elevating presence, my dragoman brought them down in the end to regular fares. This Jew of mine saved double his wage every day, and though he swindled me whenever he had an opportunity, no one else had the chance while he was with me.

But the bargain took a long time to strike. For an hour he wrangled with these drivers, who seemed to have formed an anti-American trust. At last I entered the negotiations, and demanded what all the talk was about.

‘I’m saving money for you,’ the Count informed me. ‘I’ve got them down to twelve francs.’

‘Good! then hire a team and we will start.’

‘I’ve just hired this man,’ said the Count, and he proceeded to inform one of the clamouring coachmen that he was engaged. The delighted driver dashed off to get his team, and in a few minutes a jingle of bells announced his return with the coach. It was a most dilapidated vehicle, patched and strengthened with many pieces of rough plank and bits of rope; but they were all alike.

I had particularly fancied a four-horse team, the horses all abreast as in a chariot, but this hired by the Count had only three.

COUNTING ANIMALS AVAILABLE FOR MILITARY SERVICE.

[7]‘I think we had better have four horses, Count,’ I suggested. ‘We have a long drive before us, and I don’t like moving slowly.’

‘I have already engaged this man, sir. He asks only twelve francs a day and guarantees to get us over the mountains in the best time possible.’

‘What’s the price of a four-horse team?’

‘They ask fifteen francs.’

‘Well, I think we can afford twelve shillings for a conveyance, four horses and a man, Count!’

‘But I have already engaged this man, sir.’

‘Count, we will take a four-horse team.’

The Count expostulated, and I had to repeat. It was then I discovered that there was something of the Rob Roy in my old Jew. He would rob me because, as he informed me later, Americans were rolling in wealth, but he was going to do the right thing by a peasant.

‘But I have hired this man, sir,’ he said again. ‘We shall have to pay him if we take another.’

I told the Count to give him half a day’s wages, which he did, and the peasant nearly collapsed with surprise.

The drive over the mountains to Kustendil consumed six hours, so we did not arrive there until long after dark.

My advance had been telegraphed ahead from Sofia, and soon after breakfast next morning I was waited on by the governor of the district and all his staff in a body. The governor had instructions from[8] the Minister of the Interior to facilitate my journey in every way, and was ready to do anything he could to aid me. I expressed my appreciation of his kindness, and promised to avail myself of it if necessary. There was method in this hospitality: the Bulgarians are not ordinarily so polite.

The arrival of an American correspondent was a great event in the little town, and hard on the heels of the governor came two English-speaking Bulgars, college graduates respectively of Princeton and the University of West Virginia. One of them was a magistrate, the other a minister acting under the direction of the American missionaries. Politically the magistrate and the governor were enemies, and the officials, all members of the Orthodox Church, were none too friendly with the Protestant preacher. The courtesy between the parties was stiff and measured. When the governor and his staff took their leave, the minister and the judge commandeered me for the rest of the day to talk over old times in America. We went over to Fournagieff’s home, a plain building with whitewashed walls of stucco, a low door, and a narrow, ladder-like staircase leading up to the mission-room. There we hunted out a book of college songs, and all three sang old Princeton airs for an hour to the accompaniment of an American melodeon.

Fournagieff’s father was among the refugees from Macedonia who were then in Kustendil, having come across the border to escape a search for arms in the Raslog district. I could not get the old man to admit[9] his association with the Committajis (committee-men), but I think there is no doubt that he was a local voivoda. At any rate, the Turkish officials suspected him of being a chief, of organising and arming the peasants of his village, and planned to subject him with others to an inquisition; but a friendly Turk warned him of the prospective arrival of troops and advised escape. Old Fournagieff’s Turkish friend supplied a testimonial vouching for his loyalty to the Padisha, which enabled him to pass over to Bulgaria by the bridge on the Struma, and saved him the hardship and dangers of climbing the border Balkans between Turkish posts.

Kustendil is not a favourite place of refuge, and there were few fugitives here; but the town suits the purposes of the insurgents, and rightly has a bad name among the Turks for breeding ‘brigands.’ The mountains in this district are wooded and rugged, and an infinitely larger and more vigilant force than the Turkish Government maintains on the frontier is necessary to close it to the committajis. There were several bands in Kustendil at this time, preparing to cross into Turkey, and the leaders of one called at the hotel and invited me to accompany them. I should see everything in Macedonia, they said, if I went under their guidance, whereas, if I trusted myself to the Turks, I should see only the beauties of the land and none of its horrors. I questioned these fellows as to the conditions of the scheme, and learned these: I should have to travel by night and[10] keep closely hidden by day; I should have to wear the peasant garb peculiar to the district in which I was, and raise a beard to hide my foreign physiognomy; I should have to live on the coarsest of native food and sometimes go without any; I should not be allowed to talk to anyone, for the band could not take along my antique interpreter.

I was very anxious to see one of their fights, I said, and I asked if they would have one within a reasonable time.

Certainly, came the reply; they could have a small one whenever I liked.

I was much tempted to the adventure, but afraid to trust myself to the tender mercies of these ‘brigands,’ and mildly told them so. This gave the leader an idea.

‘Would you like to get rich?’ he asked.

‘I would,’ I replied.

‘If you will permit us to capture you, we will share whatever ransom we obtain.’

Before I could reply the Count delivered his advice, which it suited me to follow. The Count did not like the idea of the brigands taking me out of his hands.

ON A FRONTIER BRIDGE.

While I was entertaining the committajis the governor returned to the khan to invite me to luncheon, and entered my room unannounced. I expected to see a hurried scattering of my guests, but none of them so much as changed countenance. The governor took them in at a glance, but otherwise completely ignored them. At this time the Bulgarian Foreign Office was[11] declaring emphatically that every effort was being made to prevent the passing of bands from the Principality into the sovereign State, so it rested with the governor to make excuse for the inactivity of the law in this case. The governor gave explanation at his table. He said he knew every one of the insurgents who were in my room, and that they were all bogus warriors, not worthy of arrest. None of them had ever been to Turkey. They belonged to the External Committee, and they took good care to do no internal work.

While strolling through the town with my Count at a later day, there appeared a band of some twenty unarmed insurgents under arrest. One gendarme had charge of the whole party, and took little heed of their scattering. They were on their way to Sofia. They had just come back from Macedonia after hiding their arms in the mountains, and had come down to the town to surrender. If they allowed themselves to be arrested, I understood, they received free transportation to the capital, where their names were recorded and they were set free on parole; whereas, if they avoided arrest, they were compelled to walk to wherever they would be, for none of them possessed sufficient money to pay railway or coach fare.

They were a mongrel crew, only one clean ‘man’ among them, and that a woman. They looked as if they had seen service. Their outfits covered a wide range of variety, and were much torn and tattered. A few had military overcoats with many[12] patches, some wore native cloaks of broad black and white stripes, and others were wrapped in blankets like American Indians. The woman had no greatcoat, but her uniform was warmer and in better condition than those of the men: the patches were perfect. She carried a needle and thread, but only one kind of medicine, though a red cross decorated her arm. She caught my eye at once, and I sent the Count into the band to ascertain if she would honour me with an interview. My man went up to her with the blunt and burly manner he was wont to wear, grabbed her by the arm, and explained his errand in a word. This, I can imagine, is what he said: ‘Come with me; an American correspondent wants to hear your story!’ The whole band, including the single guard, stopped, wheeled round, and followed the bad-eyed Count and his captive. They gathered about the girl and me, and prompted her memory whenever it failed on points of detail.

THE AMAZON. THE MASCOT.

We sat on two empty wine casks in front of a peasant’s khan, and I took notes as the Count drew from the Amazon an account of her adventures beyond the border.

This band had been in the enemy’s country for about six months, in which time they had had five fights, and she estimated that she herself had killed and wounded no fewer than eight Turks. While she talked she crossed her trousered limbs and drew a dagger from her legging as a Scot would from his sock. She tossed the weapon about and caught it dexterously[13] by the handle, and told me how she marched with her brothers-in-arms fifty miles and more a night.

In the daytime they rested at the summit of some lonely mountain which commanded a length of road and a breadth of valley, and from these ‘crows’ nests’ in the height descended by night to ambush small bodies of Turks or swoop down on little towns, attempting the total destruction of the garrison and the last male Moslem therein. This woman had no mercy on Turks; she said they had slain her mother, her father, and all her brothers in one day. She was a soldier of fortune; revenge was hers, and hope for Macedonia. In concluding her remarks the lady drew a phial of arsenic from her trousers-pocket and informed me that the poison was for the purpose of taking her own life in case of capture by the Turks. I took her photograph, with and without her companions, and the whole band shook hands with me and resumed their march to the railway terminus.

This was the only female fighter I encountered on my tracks through the Balkans, but there are many with the bands. A missionary told me an interesting story of one, which throws light on the strange mental workings of some of the insurgent chiefs. The missionary met the Amazon, a pretty young woman about twenty, wandering along a high road near Samakov. The girl asked the way to the town, and told the following story: She had been betrothed to a young man who felt called to the service of his country. She threatened her lover that if he joined a revolutionary[14] band she would go with him. Both firm in their purpose, they both joined the band, and for several weeks fought side by side. But the girl was not able to stand the hardships, and the heavy work soon began to tell on her. She began to lag behind the others on the hard night marches, and would not have been able to keep up at all except for the assistance of her strong young lover. Finally the voivoda called the man before him and delivered himself thus: ‘Committajis have their work to do and cannot be hampered with women. The woman must be left behind to-night, but you must continue with the band.’ The man protested, entreated, threatened, but all to no avail. That night the insurgents started, leaving the woman to an unknown fate; the man refused to accompany them. The chief did not hesitate to order the recognised punishment, and his men, though they liked the young man well, did not hesitate to execute the command.

The youth was taken into a secluded dell, from which he never came forth. The girl listened, but no sound escaped. The report of a gun might have attracted Turks.

She found his body later, stabbed, and buried it in leaves. The insurgents punish with death; they have no prisons.

A representative body of Bulgarians assembled at the khan on the morning of our departure from Kustendil. Several army officers, who were staying at the khan, rose early and ate a five-o’clock breakfast with us; a deputation of committajis arrived before we had finished the meal; at six o’clock the missionary and the judge appeared; and a mounted officer and two gendarmes drew up before the door; peasants on their way to the fields, and meek and miserable refugees, for want of something better to do, gathered to see the strange foreigners depart. Everybody was anxious to be of service to us, and ready at a word to do anything we required. But the judge and the minister managed to secure all of my few commissions, because they, speaking English, did not have to wait like the others until the Count interpreted my wants. I had to arrange several minor matters, such as the forwarding of telegrams and letters, and to send some of my luggage back to Sofia, because we had discharged our shandrydan at this point, and would proceed down the frontier mounted.

While I was engaged stuffing a toothbrush, a box[16] of Keating’s, a couple of pairs of socks, and other absolute necessities into my saddle-bags, the Count, ever busying himself with money matters, went to the khanji and requested the statement of our account. Now, the innkeeper was a Greek, and, true to Hellenic principles, he had charged us all and more than he had any hope of getting. He tried to put the Count off and get a settlement from me. But my Jew was not to be thrust aside by any mere Greek.

The khanji informed the Count—after much insistence on the part of the latter—that we owed him a sum of several napoleons (I do not remember the exact amount).

‘What!’ exclaimed the Jew. ‘Let me see your book.’

The Greek passed over a much ear-marked memorandum book in which he had kept the record of the number of nights we had slept at his hostelry, and what we had eaten. We had been charged three francs per night per cot, while two officers who shared a room with us and had like accommodation, were paying less than a franc apiece; two francs fifty for each meal—for which the Bulgarians paid less than a third as much—and a franc a flagon for the Count’s wine, correspondingly high for the native vintage. My man began to talk to the khanji in loud, loose language, which let the entire assembly know of the Greek’s crime. The officers, the committajis,[17] and even the ordinary natives became indignant at this ‘attempt to impose on a foreigner,’ and in a body joined the Count in abusing the garrulous Greek. The Greek stood his ground in a manner worthy of his ancient forefathers, and declined to take one sou off his bill, arguing that I should pay at the rate at which I was accustomed to paying. The foreigner, he contended, should not profit by native prices, but the native should profit by foreign prices. Good reasoning. I offered to ‘split the difference’ between native and foreign prices. The Greek agreed, but the sum to be paid figured out too much to meet the approval of the Count, who left the khan most disgruntled, because, he said sorrowfully, ‘It hurts me to be cheated; and even if it suits you to throw away money, I would have you refrain from lavishing it upon Greeks, who do not appreciate it, and puff themselves up with pride at having successfully swindled me!’ My old Jew assumed more the rôle of manager than man, and I did not dislike him for it. While I acted on my own judgment in matters of more or less importance, I always listened to his counsel, for it was generally good, and I took no measures to suppress him.

We made so early a start from Kustendil that the governor was unable to be present; but he sent a representative to wish us a pleasant journey and to offer me an escort of gendarmes.

‘Isn’t the district safe?’ I asked.

The question was offensive. Everybody generally[18] responded to my inquiries in one breath, but this brought a dignified silence over the assembly; only the official person, the governor’s representative, replied:

‘Every district in Bulgaria is perfectly safe. You can travel anywhere in our land as securely as you can in your own.’

‘Then of course we need no escort?’

‘But there is danger,’ interrupted the Count, unconsciously blinking his bad eye. ‘The route which we are taking is seldom travelled, and if we encounter border patrols we shall arouse suspicion.’ The Count knew what the company of gendarmes would mean in foraging, and to old Von Stuffsky the grub was the thing!

The gendarmes were fairly well mounted, but the only animals that we could obtain were two tiny pack-ponies full of tantalising pack-train habits. They were strong little beasts, and could travel all day without showing fatigue, but it was impossible to get them out of a pack-train gait, and under no circumstance would they travel side by side. After the Count had struggled desperately with his little brute for quite an hour, he borrowed one of the officer’s spurs, and we all halted while he sat on a rock and fastened it to a foot; for had we not waited, the Count’s animal, having no other to follow, would have taken him back to its stable. When the old man mounted again his temper had cooled, and instead of giving his pony a vicious kick, as I expected, he brought his heels together gently but firmly. The horse lifted a hind leg[19] and kicked viciously at the bite. But this did not rid him of the annoyance, so he turned his head around and sought the insect with his teeth. For this he got a kick in the nose, and then began to learn what the spur meant.

The price for the hire of the ponies was absurd, a franc a day apiece; and we paid another franc a day for a boy to go with us and care for them. This boy was wise; he came along on foot.

From the crest of the first high hill Macedonia came into view. The land sweeps on as one; there is no line to mark where Occident ends and Orient begins; but somewhere down there the order of things reverses. Here, where we stood, the Mohamedan is the infidel; across the valley the Christian is the giaour.

We took a course generally along the Struma, as near the border as we could pass without being halted by frontier guards. We kept to the north bank as much as possible; when compelled, because of bad ground, to take the south side, we did not lose sight of the river, for there was no other line to keep us within the border. There was no high road on our route, and for many miles not even a footpath. We had no guide, and neither of the gendarmes had been over the route before. Consequently we had often to retrace our steps and make long détours, sometimes for miles, when we happened to get into a ‘blind’ cañon or meet the edge of a mountain side too steep for descent. Once, while following the river (which was generally fordable), we[20] came to a gorge less than a hundred feet in breadth, through which the water poured swift and deep, and on both sides the mountains rose almost perpendicularly. We could not venture the horses into the seething waters, nor was it possible to get them up the steep slopes, so we were obliged to make our way back up stream until we found an incline gradual enough to climb.

It was often necessary to dismount and make our way on foot. For several miles we followed a footpath seldom more than two feet wide, high up on the side of a steep, rocky mountain. Fortunately the ponies were cool-headed and sure-footed. On one such ledge we overtook a committaji pack-train making its way towards the frontier from Dupnitza with ammunition and provisions for a band. We hailed the insurgents and accompanied them to an apparently deserted hut with a little wooden cross at its top. When we came in sight of this place the voivoda gave a long, loud whistle, and two men appeared. Where were the others? We were all disappointed to hear that the band had had a good opportunity to cross the border the evening before, and had gone back into Turkey without waiting for the supplies.

We ate lunch at the insurgent armoury, and had a contest at target-shooting after the meal. Some of the insurgents were very good marksmen, but the gendarmerie officer hit more ‘bull’s eyes’ than any of us.

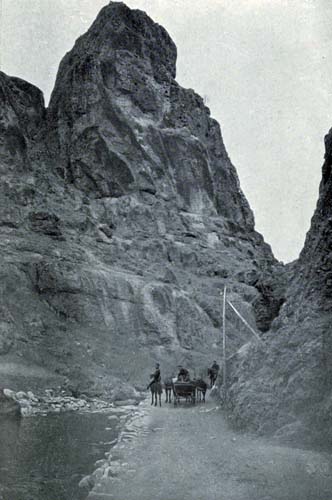

THE ROAD TO RILO.

[21]For hours before we came upon this hut we had not passed a single habitation, and for quite a while after we left it the mountains were completely deserted. It was just the place for a brigand camp. Most of the country through which we passed this day was not only uncultivated, but almost entirely barren; dwarfed shrubs grew in patches here and there, but no woods did we pass in the whole twelve hours’ track.

In the afternoon we came upon a faint footpath which led in our direction. After following it for half an hour, we found it change abruptly into a waggon track, though no farmhouse or ploughed field excused this sudden transformation. The road began at nowhere, but led down to the river again, through it, and up to Boborshevo, where we had planned to spend the night. We found our boy already established at the khan; he had outstripped us early in the day.

We were all weary and dusty, and ravenously hungry, but the khan’s larder contained only a huge round loaf of brown bread, a few bits of garlic, and the materials for Turkish coffee, which I had not yet come to regard as fit to drink; nor did it seem possible to obtain much else in the village. We despatched the boy to make inquiries, and he returned with the information that each of four peasant families could supply a loaf. Not a very promising outlook for supper! I asked if the villagers ate nothing else themselves, and learned that they lived practically by bread alone. They have generally a bit of cheese[22] or an onion with which to flavour the bread; but meat or fowl or eggs they indulge in only on fête days.

But our gendarmes assured us that we should get a supper, and presently the meal came bleating through the door. It was allowed to stop in the café for a few minutes, where it cuddled up to the Count, while the khanji sharpened his knife. Then the poor little thing was dragged back into the stable, and in about half an hour a smoking stew was set before us.

This town afforded about the worst accommodation we had yet found, but it provided a wandering minstrel. All the creature could do was laugh; but his laugh was incessant and infectious. We gave him supper, and he returned again in the morning for breakfast, whereafter I took the preceding photograph of him, which by no means does justice to the breadth of his grin. The cap which he wore was made (he told us) by an insurgent in a band with which he had travelled as a mascot. It was an extra large committaji cap bearing the committee’s motto, in the usual brass design,‘Liberty or Death.’ It lacked, however, the skull and crossbones sometimes worn.

The khanji at Boborshevo apologised for the bill he presented at our departure. He had stabled and fed nine of us, including the four ponies, and our indebtedness came to a grand total of eleven francs! The khan-keeper was a Bulgarian.

It is interesting to observe that a Turk swindles you to demonstrate to himself how much more clever[23] he is than is an ‘infidel’; a Greek swindles you because he desires your money; while both Turk and Greek declare the Bulgarian too stupid to cheat.

We expected to find a high road leading out of Boborshevo, but if there was one it did not lead in our direction. The only road towards the east was another waggon track which again crossed the Struma. By this time we had come to feel as much at home in the water as out of it. We had at first shown consideration for our boy by taking him across the river on one of our horses, but we both got tired of this, and he soon struck his own course, invariably arriving at appointed meeting places an hour or more before us. We met him at Kotcharinova this day at noon, resting at the village fountain and making a meal of bread and lump sugar. He declined a piece of lamb, saying that to eat meat two days in succession would make him ill.

To the south of Kotcharinova, less than half a mile, is a border post, where the casernes of the respective forces stand on the opposite shores of the narrow Struma, and the Bulgarian and Turkish sentries pace side by side, bayonets fixed, at the centre of the bridge. We made a détour to Barakova (such is the name of this post), leaving our escort to await us on the road to Rilo. There was no difficulty in securing from the Bulgarian officer permission to visit the Turkish side, but we were halted for a quarter of an hour at the magic line while the Turkish sentry called the corporal, and the corporal called the sergeant, and[24] the sergeant went and waked the commandant, who first peeped out of his window, then rose, dressed, and came to fetch us. The first remarks of this smartly uniformed officer, who spoke some French, were in the nature of apologies for the Turkish part of the bridge; a Graphic artist, with whom I visited Barakova a year later, described it as ‘made of holes with a few boards between.’

The half-dozen fezzed soldiers whom we saw from the bridge were fine specimens of men, and at a glance compared favourably in uniforms and arms with the Bulgarians. I was curious to go through their camp, but the officer would show me only his own room. The Turks possess no military secret unknown to the European, but they are all afraid he might find one in their camps.

‘It is quite absurd,’ said the officer at Barakova, as, seated on his rough divans, we sipped his coffee; ‘it is quite absurd for the foreign journals to say that Turks commit atrocities. We are a highly civilised people, and our Padisha is a most enlightened and humane monarch, and it is ridiculous to accuse him or his army of doing a single barbarous deed. Now, the Bulgarians are barbarians, and, naturally, it is they who perpetrate all these massacres and other horrible crimes.

‘Tell me,’ continued the Turk without abatement, ‘are sections of America still barbarous? I read of blacks being burned at the stake.’ Clever Turk.

A BULGARIAN BLOCKHOUSE.

THE BRIDGE OVER THE STRUMA: TURK AND BULGAR.

[25]More than a year later I returned to Barakova from the Turkish side and asked the same Turkish commander for permission to visit the Bulgarian barracks; but he had many excuses to offer. Perhaps the Bulgarian garrison would not like us to visit them unannounced; it was against all regulations for anyone to step across that border without a passavant which could not be issued nearer than at Djuma-bala; if anything should happen to us while on the Bulgarian side, the Padisha would be seriously grieved at his (the officer’s) having permitted us to go over into Bulgaria. But we had despatches to forward and letters to post, and vented upon the Turk three hours’ persistent persuasion, when finally he consented to take us over the bridge himself. Six other officers accompanied him, and our interpreter was detained in the Turkish barracks as a hostage. There was no other way than to deliver our letters to the Bulgarians in the presence of the Turks, and the moment was awkward for all parties.

Shortly after leaving Barakova we got the first view of Perim Dagh, a celebrated high peak in Macedonia, renowned among the Bulgarians as the mountain from which Sarafoff issued his call ‘to his brothers’—Sarafoff and St. Paul!—to come over into Macedonia and help him!

This was a more productive district than that through which we had passed the day before; the land was generally tilled and settlements were comparatively numerous. And after passing Rilo Silo (Rilo[26] village), where the long climb to the monastery begins, the way leads through a dense forest which covers the mountains.

The road to Rilo is by the side of a rapid brook, which has its source somewhere in the wild woods far above the monastery, up under the line of perpetual snow. It tumbles for more than twenty miles over the small boulders, and between the big ones, down, down, down to the village; this, at least, is as far as I know it tumbles, from having followed it. On both sides of the brook rise the Balkans, the crest of the range to the south forming the border-line. From Rilo Silo to Rilo Monastery there is but one pass through these mountains, and in this gateway to Turkey stands the Bulgarian blockhouse shown in the preceding picture. In spite of the fact that it was yet winter, the leaves on the trees were thick enough to keep the rays of sun from the road, and there was a chill under the grove which soon caused us all to unpack our greatcoats. As our elevation increased, the air grew yet colder; the brook took on icy rims, icicles clung to the bigger boulders, and snowdrifts lodged by the side of the road. We dismounted one by one, for the slow up-hill pace of the horses afforded no exercise, and we needed more warmth than our coats would give. The gendarmes, as I have said, were better mounted than were the Count and I, but on foot we had the advantage of them. Their horses had always to be led—and did not lead as well as they drove—while our pack-ponies, ever content to follow pace, could[27] be turned loose, and would follow the other animals as tenaciously as if tied to their tails.

The sun had long dropped behind the mountains—though the day had not yet gone—when we emerged from the forest into a clearing, and the first view of the great, bleak, deserted-looking monastery broke suddenly upon us. The heavy gates were swung back, grating on their rusty hinges, and a long-bearded, black-robed priest came forth to welcome us. The gendarmerie officer had telegraphed from Rilo Silo that we would arrive that night, and the hospitable monks had got our rooms warm and ready, and prepared a splendid supper for us.

There was no fireplace or stove in the room which was allotted to me, but a broad, tiled chimney came through the wall from an ante-room. A queer little dwarf—not a monk, but long-haired and bearded like them—who occupied this room, was assigned to the task of waiting on us and stoking the fire in the oven.

The Rilo Monastery is a great rectangular pile four storeys high, built of stone around a spacious courtyard. On the outside a height of sheer wall is broken by small barred windows only above the second floor, and two arched gateways below, one at each end of the place. The old convent was built for siege. Within, facing on the courtyard, are broad balconies, quite a sixth of a mile around. The chapel stands in the centre of the court, and beside it there is an ancient tower and dungeon dating from mediæval times. Although the foundation of the monastery is very old,[28] most of the present structure and the church date from only 150 years back. At one time it sheltered several hundred monks, but the number has dwindled away until to-day there are but fifty or sixty there. The old abbot said ruefully that since the Bulgarians had become free they are not so willing to enter holy orders as they were when under the Turks. Naturally; this monastery, for some reason, was always exempt from ravage by Turkish troops, and to enter it was to find safety for body as well as soul. The greater part of the building is now usually unoccupied, and its vast, bare rooms have a most desolate appearance.

The painting of the place is most peculiar. Outside the stones are left their natural colour, but the courtyard walls are whitewashed and striped with red. The balconies and the overhanging roof, the rafters of which are visible, are almost black from age. The place would be magnificent were it not made hideous with atrocious frescoes, which might have originated in the mind of a Doré and must have been executed by a schoolboy. The pictures covering both the outer and inner walls of the chapel, which stands in the centre of the court, are grouped in pairs or sets, and portray side by side the after torments of the wicked and the bliss of the good. Many of the sleeping-rooms are likewise decorated in a manner conducive to nightmare.

RILO MONASTERY: GRACE BEFORE GRUB.

There is a museum at Rilo of old Bulgarian books, icons, and other church relics, of all of which the monks are very proud. Many of the books were saved[29] from destruction at the hands of the Greek priests in their late attempt to Hellenise the Bulgarians by obliterating their language. There are presents from the Sultans, and some articles of intrinsic value.

I was much interested in a retired brigand who lived at the monastery, and invited him and a committaji sojourning there to join us one evening at supper. We were a strange gathering that sat down to the monks’ good fare that memorable night. There were many monks, in flowing robes and headgear like stove-pipe hats worn upside down. In the centre of this sombre assembly was our party: the brigand, a powerful mountain fellow who had worn his weapons day and night for thirty years; a desperate revolutionist engaged in directing the passage of bands across the Balkans; a border officer who had been picked for his nerve and judgment to serve on the Turkish frontier; my Count and myself.

It took much persuasion and many glasses of the monks’ good wine to make the brigand tell us of his adventures; but when he had fairly begun he went into most extravagant detail and gave us substantial demonstration of how he had done his many deeds of valour. He took his yataghan and wielded it about him in a desperate manner as he told us of how, when surrounded on one occasion, he cut his way through overwhelming numbers of Turkish troops; he drew his dagger at another period and crept stealthily along to slay an adversary by surprise; and he stretched himself full length on the floor and[30] aimed his rifle over imaginary rocks when giving an account of what he considered the narrowest escape he had ever had.

He and his band had been forced by a body of Turks up a mountain side at the back of which was a yawning precipice. Half of his men dropped behind rocks and held the Turks at bay while the others took off their long red sashes and tied them together into a rope, by which all but four managed to escape by sliding down the chasm into a thickly wooded valley below. The brigand told us that he had chopped off the heads of Turks with a single blow, and had to his credit in all seventeen dead men. He was an Albanian—a Christian Albanian—which accounts for the record he kept of his killings.

Everybody at the monastery but myself was accustomed to such narratives as these, and no one else—not even the holy monks—showed the least emotion at the bloody recital. It was purely for my benefit.

Towards midnight the conversation turned to combats to come, and both the officer and the committaji assured me there would be no lack of blood-letting as soon as the snows melted. Ammunition was going across the frontier nightly, and preparations for the revolution were being prosecuted vigorously under the very noses of the Turkish authorities. But it was necessary in some districts, where the Government officials were keenly on the alert, to adopt curious means of getting arms into the towns. The[31] insurgent told this story of how a supply of dynamite bombs was got into Monastir. A funeral parade started from an ungarrisoned village near by, and marched into the town to the solemn chant of a mock priest, attired in gilded vestments, and acolytes swinging incense. Mourners, men and women, followed the corpse, weeping copiously. The Turks did not notice that the dead man was exceptionally heavy, and required twice the usual number of pall-bearers. The insurgents buried their load in the Bulgarian cemetery with all due dust to dust and ashes to ashes. The local voivodas were apprised of the fact, and the following night a select delegation robbed the grave.

There were no refugees at Rilo on the occasion of my first visit. Several months had elapsed since the search for arms in the Struma and Razlog districts, and the fugitives who had come to the monastery to escape this inquisition in Macedonia had now moved on to the towns and villages further from the frontier. But six months later, when I returned after the revolution in Macedonia, the place was crowded with refugees. There were nearly two thousand quartered in the main building and in the stables and cornbins round about, and more were arriving daily. Some reached the monastery driving a cow or two, and others leading ponies and donkeys heavily laden with all their poor possessions; but many came with only what they carried on their backs. The special burden of the little girls seemed to be their mothers’ babies, borne in bags strapped to their backs.

[32]Some of the young mothers bore between their eyes peculiar marks which attracted my attention. They were crosses tattooed there. They told me that these life marks were for the purpose of preventing the Turks from stealing them; but I am of the opinion that the sign of the Cross would not prevent a Moslem from taking a Christian woman.

A caravan of pack-ponies arrived at Rilo every morning, bringing bread, which was supplied to the refugees by the Bulgarian Government. Besides this they received soup from the monastery once a day.

The kitchen at Rilo is quite worthy of description. It is on the ground floor, but above it there are no other rooms. Its walls go up to the roof. The fire is built in the centre of the room, on the floor, which is of stone, and the smoke rises a hundred feet and escapes through a round hole about a foot in diameter. The refugee soup was boiled in a huge iron cauldron, suspended by chains over the fire. So large was this pot that the cook had to stand on a box to stir the boiling beverage, which he did with a great wooden spoon almost as long as himself. At noon the refugees gathered in the courtyard with earthen vessels, and as the names of their villages were called they came up to the pot, and the old grey-bearded cook dished out a big spoonful of soup to each mother, and a monk handed her a loaf or more of bread according to the number of children she had.

FATHER COOK AND THE BRIGAND.

The native costumes of the Macedonians are of[33] the gayest colours, and this midday scene was beautiful as well as pitiable. But there was a night scene at the monastery which was even more fascinating. There were two companies of infantry also quartered here, and as there was no hall to spare for use as mess-room, they were obliged to eat their meals in the open courtyard. A few minutes before the supper-hour pots of stew or soup, or other army rations, were set in a row on the stone pavement. When the call to mess was sounded the soldiers fell in behind the pots, each with half a loaf of bread and a tin spoon, and stood facing the chapel. The drums beat again, and with one accord the line of yellow-coated men doffed their caps. Their officer, likewise reverencing, pronounced the grace, and the company made the sign of the Cross three times in drill regularity. The men then seated themselves, eight round a pot, and began their meal in the golden light of pine torches fastened to the great pillars which support the balconies.

In the Balkans the Christian call to mass is beaten on a pine board. The hours of prayer are regular at Rilo, and the time of day is told by the shrill tattoo. The next lap of our trail was long, and we rose and saddled horses at the call to six o’clock mass.

From Rilo it is a day’s track to Samakov, a primitive, dreamy town, full of frontier colour and character. A mosque and a Turkish fountain still do duty in the market place, and many times a day Turks come to the fountain to wash before entering the mosque to prayer—just as they do across the border. But over there the Christian drawing drinking water makes way for the Moslem to wash his feet, while here the Turk is made to wait his turn like any other man. Samakov is much like other border towns, built largely of mud bricks, roofed with red tiles, crowned with storks’ nests. It possesses, however, one distinctive feature.

The largest American college in South-Eastern Europe, outside of Constantinople, is here. It is conducted by the American missionaries, and educates most of the Bulgarian teachers employed in the Protestant schools throughout Bulgaria and Macedonia. It is something more than a theological institute; it is also an industrial school, patterned after those most successful in the United States, where boys learning trades may earn part or all of their tuition.[35] The carpentering department and the printing press are both conducted at a profit, which is credited proportionately to the boys who do the work. In the girls’ school the duties of home and life are taught, as well as book knowledge, and some of the young women are trained for the positions of teachers in the smaller mission schools.

The Bulgarians owe much to the American missionaries, both directly and indirectly. For one thing, the Americans have excited, without intention, the jealousy of the Orthodox Church, which has undoubtedly assisted in keeping the priests active in developing their own educational institutions. It was not until the American missionaries opened a school for girls in their land that the Bulgarians began to educate their women. But that was many years ago, before Bulgaria became a quasi-independent State; now the State schools afford every advantage the Americans can offer—except the American language.

The Bulgarian Government attempts to administer justice to all denominations and to maintain religious equality before the law, and the Government comes fairly near to this aim. The Greeks complain that Greek schools are not subsidised, but Turkish schools are maintained by the State. It is due to the freedom of religious opinion existing in Bulgaria that the missionaries have become so closely allied with the Bulgarians, for in no other Balkan country, except perhaps Rumania, is there the same liberty of thought. The Servian Government prohibits by law all proselytising[36] to Protestantism. The Greeks—though they welcomed the aid and sympathy of the missionaries in the Greek war of independence—have since enacted laws which make the teaching of ‘sacred lessons’ in the schools compulsory, lessons of a character which the missionaries refuse to disseminate. The Sultan would not tolerate the missionaries in his dominions if they attempted to convert Mohamedans, while the few Turks who have deserted Mohamedanism have mysteriously disappeared. And it has been found almost impossible to convert Jews. So the missionaries are left only the Bulgarians on whom to work. Their schools and churches are open to other nationalities in both Bulgaria and Macedonia; but, for the double reason that they are institutions of Protestants and of Bulgarians, very few of the other races ever seek admission.

BULGARIAN PEASANTS, SAMAKOV.

But the Bulgarians do not appreciate the work of the Americans; indeed, those who are not converted distinctly rebel against what they term the ‘Christianising of Christians.’ I have said that the Government was just in religious matters; the members of the Government, however, are not. Government officials (adherents of the Orthodox Church, or they would not be elected) make it difficult for the missionaries to extend their work, by delaying necessary permits and privileges as long as possible; and they favour members of the Orthodox Church in making appointments to public service. The unfortunate missionaries are, therefore, between the devil and the deep sea; for while the[37] Bulgarians resent being the subject of missions, the Turks accuse the Americans of propagating a revolutionary spirit amongst the Bulgars. Of the latter, however, they are not directly guilty, though the education of a peasant naturally tends to fire his spirit.

But there was one occasion when the American missionaries came to be important instruments of the Macedonian revolutionary cause. This was in the notorious capture of Miss Ellen M. Stone, a certain feature of which, not correctly chronicled at the time, makes a most interesting narrative.

Early in July 1901, a party of Protestant missionaries and teachers—among whom Miss Stone was the only foreigner—left the American school at Samakov and crossed the Turkish frontier to Djuma-bala. From Djuma they proceeded into Macedonia, without an escort, considering that the party, numbering fifteen, was too large to be molested. Towards nightfall of the first day out the travellers, growing weary, allowed their ponies to straggle, as the Macedonian pony is wont to do. At dark the cavalcade began to ascend a rugged mountain in this disorder, and rode directly into an ambush laid for the Americans. It was an easy matter for the brigands to ‘round-up’ the whole number without firing a single shot. The brigands had no need for the other members of the company, being Bulgarians, and sent all of them on their way except Mrs. Tsilka, whom they detained as a companion for Miss Stone.

[38]The sum demanded for Miss Stone’s ransom was twenty-five thousand Turkish liras, slightly less in value than so many English pounds. The American Government took no effective measures to secure the release of its subject, and it was left to the American people to subscribe the ransom money. In a few months the sum of sixty-eight thousand dollars (fourteen thousand five hundred pounds Turkish) was collected, and the American Consul-General at Constantinople went to Sofia to negotiate the ransom. But in Bulgaria he was annoyed by the people and the press, and hampered by the Government, and he soon found it impracticable to pay the money to the brigands from that side of the border. The Orthodox churchmen had no sympathy for the American evangelist and treated the affair as a grand joke, while the Government sought to prevent payment of the ransom on Bulgarian soil, lest it should be called upon by the United States at a later date to refund the amount.

At the end of five months from the time of the capture, the Consul-General (Mr. Dickenson) had accomplished only an agreement with the brigands that Miss Stone should be set at liberty on payment of the sum collected in lieu of the one demanded, and he returned to Constantinople and transferred the work to a committee appointed by the American Minister on instructions from Washington.

According to accounts sent to the newspapers at the time by correspondents who, with many Turkish soldiers, dogged the footsteps of the three men who[39] formed the ransom committee, these gentlemen, Messrs. Peet, House, and Garguilo, after travelling over hundreds of miles of wild mountain roads, doubling on their tracks sometimes daily in their search for the brigands, finally despaired of paying the ransom in gold, sent the gold back to Constantinople, secured bank-notes in its stead, and paid two agents of the insurgents in paper money at a cross road when they (the committee) managed to escape the vigilance of the Turkish soldiers for a few minutes. But the correspondents were sadly duped, for necessity and the committajis demanded that they should be placed in the same category as the Turks, and regarded as dangerous characters.

If a member of the committee could tell this tale it would make a most readable volume, but the committee is bound by a promise to the insurgents to keep secret certain details, and I am able to give only a bare outline of the adventure.

I first learned that the original accounts of the ransoming were erroneous from Mr. Garguilo, whom I met one day at the American Legation at Constantinople, of which he is the dragoman. He was proud of having defeated some worthy men among my colleagues and the Turkish police at the same time. He told me bits of the story which whetted my curiosity, and I resolved to run it to earth.

Before I left Constantinople I called on Mr. Peet at his office, the headquarters of the American Mission Board, and, in the course of a conversation about the[40] Stone affair, added a few more facts to those Mr. Garguilo had given me. It was my good fortune, not long after, to meet Dr. House at the American mission at Salonica, and I took the opportunity of discussing the affair with him. And as I proceeded through Macedonia I encountered many others of the principal actors in the little drama. I came upon Mr. and Mrs. Tsilka at Monastir; then the Turkish officer who had been detached to follow the fourteen thousand five hundred pounds of gold; and later, in Bulgaria, I found a member of Sandansky’s band, the band which had captured Miss Stone. The brigand was the most communicative of all these principals, and I got from him some details which the ransom committee had been sworn not to divulge, for fear lest punishment should be meted out by the Turks to the town which played the important part in the delivery of the ransom.

On Mr. Dickenson’s return from Sofia the ransom committee left at once for the Raslog district. The brigands at this juncture had become indignant at the long delay in the payment of the money and had broken off negotiations with the Americans. The first work of the new committee, then, was to re-establish communication with the insurgents, and, in order to let the brigands learn that they were on their trail, the news of the fact was disseminated broadcast throughout Bulgaria and Macedonia, and also sent to the European press, which the revolutionary organisation follows closely. This eventually accomplished the desired effect, but also caused an increase of the[41] number of correspondents on the trail of the committee.

For nearly a month the committee moved from town to town through the snow—for it was now winter—faring on the coarsest of food, sleeping in comfortless khans and undergoing many hardships, but meeting with no success. Trail after trail drew blank. On one occasion word came that two frontier smugglers, captured by the Turks, had professed to having seen Miss Stone and Mrs. Tsilka’s baby strangled, and could take the committee to the graves! There had been several other reports that the brigands had wearied of waiting for the ransom and had killed their captives, but none so detailed as this. The Turkish authorities at the point from which this evidence came were anxiously petitioned for further facts. Another examination of the smugglers was made, and the following day a telegram announced that they were altering their testimony. ‘The alterations’ completely denied the first statement, without even an excuse on the part of the smugglers for having concocted it. It seems the Turks had asked them for information of Miss Stone, and the frightened smugglers had replied in the Macedonian manner, according to what they thought their questioners desired to hear.

After a while the committee broke up, Messrs. Peet and Garguilo establishing themselves at Djuma-bala and Dr. House going to Bansko, the most rebellious town of a most rebellious district, ‘to conduct a[42] series of missionary meetings.’ Dr. House was the only member of the committee who could speak Bulgarian and converse direct with the brigands, and his action was severely criticised by the correspondents. As the journalists saw the case, here was a member of the committee, the most valuable man because of his knowledge of the brigands’ language, wasting valuable time preaching Christianity to Christians, just when his every effort should be devoted to the task of freeing the two unfortunate women and a new-born babe, who were suffering untold tortures in some sheepfold high in the snow-covered mountains. But the correspondents were not aware that Dr. House had escaped their vigilance and that of the Turks, and, under the guidance of an insurgent disguised as an ordinary peasant, had visited a delegation of the brigands; nor did they know that further negotiations for paying the ransom were proceeding along with the revival meetings at Bansko.

After Dr. House had got into touch with the brigands the money was sent for. Mr. Smyth-Lyte, of the American Consulate, conveyed it from Constantinople. Two cases, containing fourteen thousand five hundred gold pieces and weighing four hundred pounds, were delivered to him from the Ottoman Bank, where the ransom fund had been deposited. The bullion was sent under proper guard to the railway station, where a special car was awaiting it. Two kavasses were sent with Mr. Smyth-Lyte from the bank, and these bodyguards always slept on the[43] money. At Demir-Hissar, where the train journey ended, Mr. Smyth-Lyte was met by a Turkish officer, who informed him, in polished French, that he (the officer) was the humble servant of Monsieur the Consul, for whom the Padisha had the greatest concern. Monsieur’s commands, he added, would be fulfilled even to the death of the officer and twenty trusty troopers who were under his command. The Turk was suave and smartly dressed, and the trusty troopers non-communicative and very ragged.

A rickety brougham was ready to take the American and the money to Djuma-bala, a two days’ journey. The two packages of gold were loaded into the doubtful conveyance, the troopers formed a cordon about it, and the journey was begun. But the party had hardly got fairly upon the road when the severe pounding of the gold as the carriage bumped over the rocks, carried away the floor, and down went the boxes. There was a halt and an attempt to patch up the vehicle, but it was useless. One of the pack-horses accompanying the soldiers was unloaded and the gold strapped on its back; but the packages were of unequal sizes, and would persist in finding their way under the stomach of the hapless brute. At last the two kavasses, who were well mounted, were each called upon to carry a box, and in this way the money was got over the mountains.

More troops fell in as the way became more dangerous, until the number of the escort reached a hundred. Some of the cavalry men went far ahead to[44] scout, especially through the great Kresna Pass, where a handful of men could ambush an army; and others dropped back far behind the cavalcade to cover the rear. But the journey was made without mishap, and late at night of the second day, Mr. Smyth-Lyte arrived at Djuma-bala, met there Messrs. Peet and Garguilo, and delivered over his precious charge. Early next morning he set off on the return trip with his kavasses and a guard of half a dozen men.[1]

On the arrival of the money at Djuma there was a general concentration of correspondents, Turkish soldiers, and spies about it. The committee was no longer the subject of attention; the money was now the thing. If they kept close to the money, reasoned the correspondents and the soldiers, they were bound to be in at the ransom. The correspondents had no other interest than to get the news, but the soldiers were bent on getting the brigands. The Turkish Government had no idea of allowing the bandits to reap their golden harvest.

So it came to be the task of the ransoming committee to separate the gold from the correspondents and the soldiers, apparently a hopeless one. Every correspondent present was a man of sharp wits and almost untiring energy. Each of them had a dragoman always watching the Turks who surrounded the gold. The Turkish spies kept their eyes on the soldiers, the committee, and the correspondents alike.

The committee would decide at a moment’s notice[45] to leave a town for a visit to some mountain village, telling no one; but the soldiers were always with them, ostensibly guarding them from other brigands, and the tireless correspondents were on their track before the dust had settled behind their horses.

After a while Messrs. Peet and Garguilo, bringing the money, came to Bansko and there settled down with Dr. House, who was still preaching to the Bulgarians. The committee secured a private house to live in, and in one room stored the gold. Here a long rest took place. The correspondents railed against the committee, accusing it of laziness and love of comfort; but they, too, grew indolent and took their ease at their khan. At first they, with the Turks, dogged the very footsteps of the three men of the committee, but after a week of this they grew weary, for the ransoming committee were wont to walk far daily ‘for exercise,’ and loiter aimlessly on cold and unattractive mountain roads about the town. It was not probable that the brigands would venture very near to a village so heavily garrisoned and patrolled as was Bansko, and to watch the gold soon became sufficient for the correspondents. Had any of them put himself to the trouble of ascertaining what Mr. Garguilo’s habits were when comfortably ensconced at the Embassy at Constantinople, he would have discovered that any exertion whatever is distinctly foreign to that gentleman’s daily routine.

At the end of a month, to the intense surprise of everybody, a messenger came from Constantinople,[46] travelling in all the state which had dignified Mr. Smyth-Lyte’s journey. With great ceremony the two boxes of gold were delivered to him. There was no mistake about them; they were the same two boxes. They were still bound tight with iron bands and they still weighed four hundred pounds. One hundred soldiers escorted them back to Demir-Hissar. There they were carefully placed aboard another special car, and two kavasses ate and slept on them until they were safely delivered back to the Ottoman Bank at Constantinople.

A few days later the committee started on its return to the railway, with a small escort and only one correspondent. The others considered that for the present the affair was over.

At one place on the route Mr. Garguilo and Dr. House managed to leave their escort and the correspondent a little behind. The soldiers and the correspondents had lost interest now. At a cross-road they stopped and waited for their trackers. When the correspondent came up Mr. Garguilo told him that ‘the deed was done.’

On the ground there were several torn envelopes, such as a bank would use to cover notes. A few days later Miss Stone, Mrs. Tsilka, and the baby were ‘discovered,’ in a village near Seres. Two of the committee met and escorted them to Salonica.

It is obvious how the story that the money was paid in paper came to appear in the English and American press; but the money was not paid in paper.

[47]When Messrs. Garguilo, Peet, and House took their daily walks about Bansko they went out with heavy packages of gold concealed under their coats, and they returned with a like weight—but not of gold! Each night they removed a certain amount of the money, and on their return would place the lead in the bullion boxes—the vigilant guards about the house all unconscious that the gold was going. Finally, the fourteen thousand five hundred pieces had been delivered to the brigands, whom the committee-men met on their walks, and four hundred pounds of lead filled the boxes.

The return of the boxes to Constantinople with all the pomp and ceremony attendant upon the transport of treasure was not without an object. It was necessary to keep the fact that the ransom had been handed over a complete secret until the captives were released, in order that the Turks should not get on the track of the brigands. A promise that every effort should be made to throw the Turks off the trail was demanded by the brigands, as was an injunction of absolute secrecy concerning also the place and manner in which the money was paid.

But the time is past when the secret need be kept, and the brigands, now off duty between revolutions, are spinning this yarn, along with accounts of other adventures, to admiring friends in Sofia.

The money which the revolutionary organisation secured by this capture went a long way, I am told, in preparing the uprising of 1903. The insurgents say[48] that they expected the Government of the United States to exact from the Sultan the price of this ransom, thereby making the Padisha pay for the arms used against himself. But this has not been done.

We went to prayer meeting at Samakov at the invitation of the American missionaries, and took with us several officers of the garrison. The missionaries prayed fervently and at length that the Macedonian insurgents might be turned from their wicked ways. The prayer annoyed one of the officers, and, to my embarrassment, he rose and stalked out of the chapel. The others agreed with the missionaries—to a very limited extent—that the measures of the committajis were ‘often too drastic.’

The entire Bulgarian army is in sympathy with the work of the insurgents, and not the least enthusiastic with ‘the cause’ is the little mountain battery at Samakov. It is proud of the short cannon, carried in three parts on the backs of pack-ponies, and it is proud of its proficiency at handling them. The entire battery got out one morning and took us up into the mountains to show us how the guns worked. The Bulgarian army has been preparing for many years to fight the Turks.

BULGARIAN INFANTRY.

We drove back to Sofia in a small victoria drawn by four white ponies with blue beads around their necks and a diamond-shaped spot of henna on each forehead. Patriotism was running high in the country at the time, but the Bulgarian colours are red, white, and green. The decorations were in deference to the ‘Evil Eye.’

We came down the long valley to Sofia and entered the town at twilight, making our way to the Grand Hôtel de Bulgarie. The shops grew from peasant establishments where cheese and onions and odd shapes of bread were spread on open counters, to emporiums where French gloves and silk hats were on sale. Electric cars became numerous, double lines crossing each other at one corner. Here a sturdy gendarme raised his hand for us to stop; he was not as large as a London policeman, but he carried a sabre at his side. The chief of police explained to me later that the weapon was not for use, but simply to impress the other peasants, who would have no respect for the brown uniform alone.

At the head of the main street we came to a solid[50] drab-coloured, rectangular building, surrounded by high, drab-coloured walls. The massive iron gates were wide open, and before each paced two sentinels. This was the palace of the Prince. Just beyond the palace was the hotel.

Several army officers in uniform were standing before the Bulgarie as we drove up, and one hailed me in this familiar manner:

‘Well, how goes it? I see you are from “the land of the free and the brave.”’

He knew who I was; strangers are conspicuous in Sofia, and their presence becomes known quickly. There was to be a military ball at the officers’ club that evening, and I was invited forthwith. The ‘American,’ as this officer was called, waited at the hotel until I had dressed, and, after dining with me, took me to the dance.

The scene was very like that at a military hop in any civilised country. The officers looked martial in their simple Russian uniforms, and the ladies were tastefully but modestly dressed. There is no wealth in Bulgaria—not a millionaire in pounds in all the land—and the officers of the army live on their pay. Many members of the Government and other state officials were at the ball, wearing ordinary evening dress with some few decorations.

It is said of the Bulgarians that they dislike foreigners, which is true to an extent. Their attention to me on this occasion is to be accounted for in the observation of an historian, that they are[51] ‘a practical people and their gratitude is chiefly a sense of favours to come.’ I was the special correspondent of an important newspaper, and they were anxious that I should sympathise with their cause. They adopted no surreptitious means of making me do so; they went straight to the point and demanded my attitude. I intimated that I had come out to the Balkans to take nobody’s side; I had come ignorant even of the geography of South-Eastern Europe, and intended to withhold my judgment until I had seen the question from more sides than one. They granted that this was fair, and remarked that an honest man who was not a fool must perforce become a bitter partisan on the Balkan question.

The day before my departure from Sofia (on this first occasion) I excited the suspicions of a local journalist by declining to declare my sympathies. The reporter intimated that in his opinion a newspaper like mine would hardly send on such a mission a man who was quite as ignorant as I professed to be! They are bold, these Bulgars.

This journalist was my undoing. I did not see what he wrote about me until I returned to Sofia, a few weeks later, and found myself completely ignored by the very Bulgars who had been most attentive. Officers who had toasted me when I started for the frontier would not return my salute; newspaper men who had interviewed me now slunk by in the street, and statesmen and politicians barely nodded when I[52] lifted my hat. This was undoubtedly deliberate; the Bulgarians could not have forgotten me so soon. I sought my friend the officer who spoke American, and inquired of him if he knew in what way I had offended his fellow-countrymen. He did not hesitate a minute. The Vitcherna Posta, he informed me, had shown me up. The paper had discovered that I had come out to the Balkans pledged to support the Turks, and my pretended ignorance was simply a bluff. The proprietor of my paper, who would probably condemn another man for accepting a monetary bribe, had been bought with a paltry decoration from his Sultanic Majesty. No news but such as was favourable to the Turk and hostile to the Bulgar would be published in my paper. In proof of this statement the ‘Vampire Post’ called attention to the fact that I had paid frequent visits to the Turkish Agency before my late departure.

The young officer did not tell me this in the offensive manner of a candid friend; he delivered the accusations straight from the shoulder, and on concluding offered me a native drink, as if I could have no mitigating argument; he was satisfied of my guilt, but when he was in America my countrymen had treated him well.

‘The Bulgarians are not very politic,’ I observed; to which the officer assented and signed to me to drink, implying by a gesture: this disagreeable explanation is over, but you are my guest.

The Sofia journal had mistaken me; I was not the[53] correspondent of the paper whose proprietor had been decorated by the Sultan. Nor were the numerous visits I had paid to the Turkish Commissioner due to any but legitimate reasons. The Sultan’s representative, indeed, accused me of making a suspicious number of calls on Bulgarian officials and of receiving too many revolutionists at my hotel; and when I applied to him for permission to proceed to Macedonia I found many visits and much persuasion all of no avail. He had an antidote prepared for me, an immediate trip to Constantinople, where the diplomatic atmosphere is sympathetic with the Sultan. Thus, by trying to maintain the friendship of both Bulgar and Turk, I had incurred, at the very outset of my mission, the hostility of both.