“‘D’ Y’ KNOW WHAT THIS IS?’ JABEZ SMITH ASKED, HOLDING OUT THE STRIP OF PAPER.”

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/tommyremingtonsb00stev |

“‘D’ Y’ KNOW WHAT THIS IS?’ JABEZ SMITH ASKED, HOLDING OUT THE STRIP OF PAPER.”

Lessons were ended for the day, and an unwonted noise and bustle filled the little school-house as the children caught up their books and hats, eager to breathe again the fresh air with the keen scent of the woods in it, to revel in the bright sunshine bathing hill and valley.

“Good-by, Miss Bessie.”

“Good-by, dear.”

Three or four of the girls had lingered for the parting greeting, and then they, too, hurried away, while Miss Andrews stood in the school-house door and looked after the little figures as they tripped down the narrow path toward the group of coal-grimed houses which made the town of Wentworth, and she sighed unconsciously as they passed from sight behind an ugly pile of slack. It was not a pretty scene, this part along the river which man had made, with its crazy coal-tipples, its rows of dirty little cabins, its lines of coke-ovens, and the grime of coal-dust over everything.

How different was that part of nature’s handiwork which had been left unmarred! Mountain after mountain, clothed in green to the very summit, towered up from the narrow valley where New River picked its difficult way along, over great boulders and past beetling cliffs. How many centuries had it taken the little stream to cut for itself this pathway through the very heart of the Alleghanies! With what exhaustless patience had it gone about the task, washing away a bit of earth here, undermining a great rock there, banking up yonder behind some mountain wall which it could not get around, until it overtopped it and began the work of eating it away—so had it labored on, never wearying, never resting, never growing discouraged, seeking always the easiest way around the mountain-foot, but when no such way could be found, attacking the great wall before it with undaunted courage, singing at its work and splashing brightly in the sunshine—until at last it had conquered, as such perseverance always must, and springing clear of the hills, dashed joyously away across the level plains which would lead it to the sea.

And all this labor had not been in vain, for nature’s work had rendered man’s much easier when the time came to build a railroad over these mountains in order that the great wealth of coal and iron and other minerals which lay buried under them might be brought forth and so become of value to the world. The engineers who were sent forward to find a way for the road soon saw that the New River valley had been placed there, as it were, by Providence, for this very purpose, and when the road was built, it did not attempt to go straight forward, as railroads always like to do, but crept patiently along the river’s edge, following every winding, until the mountains were left behind. And the great men who built the road were very thankful for this little stream’s assistance.

It was not at the mountains nor at the river that Bessie Andrews looked, but at the grimy cabins of the miners, scattered along the hillside, and she thought with a sigh how little successful she had been in winning the hearts of their occupants. She had come from Richmond in a flush of happiness at her good fortune in getting the school, and determined to make a success of it, but she found it “uphill work” indeed.

Her story was that of so many other Southern girls coming of families old and one time wealthy, but ruined by the Civil War. The father, who had gone forth to battle in the strength of his young manhood, left his right arm on the bloody field at Gettysburg, and came home, at last, to find himself quite ruined. He could get no laborers to cultivate his fields, rank with the weeds of four years’ neglect; his stock had been seized by one or other of the armies, for both had fought back and forth across his land, with a necessity of need that knew no law; his people had been freed, and, excepting two or three of the older house-servants who had grown gray in the family’s service, had drifted away no one knew whither. For three years he struggled to bring order out of this desolation, but the task was greater than his strength. So the plantation was sold for a mere fraction of its worth before the war, and the family had moved to Richmond, in the hope that life there would be easier. There, ten years after the city fell before Grant’s army, Bessie Andrews was born; and there, some twelve years later, her father died, gray before his time, bowed down with care, so broken by his grim battle with the world that disease found him an easy victim.

So Bessie Andrews had never known the luxury and kindliness and easy hospitality of the old plantation life, but its influences and traditions lived still in her blood. She was a gentlewoman, with all a gentlewoman’s shrinking from the tragic and sordid and mean things in life; so it was only after a struggle with herself, as well as with her widowed mother, that she had ventured forth into the world to attempt to add something to the scanty income left them by her father. She had been educated with some care, at home for the most part, so she tried to secure a position as teacher in the public schools, deciding that it was this she was best fitted for; but there were no vacancies. Yet the superintendent, impressed by her earnestness, promised to keep her in mind, and one day sent for her.

“I have a letter here,” he said, “from one of the directors of a little school near Wentworth, in the mining district. He wants me to send him a teacher. Do you think you would care for the place?”

Miss Andrews gasped. She had not thought of leaving home. Yet she could do even that, if need be.

“I think I should be very glad to have the place,” she said. “Do you know anything about it, sir?”

He shook his head.

“Very little. I do not imagine the region is attractive, but the salary is fair, and the director who has written me this letter, and who seems to be a competent man, will board you without extra expense. Think it over and let me know your decision to-morrow.”

There was a very tearful interview between mother and daughter that night, but it was evident to both of them that the place must be accepted.

“If I could only go with you,” said her mother, at last. But Bessie silenced her with an imperative little gesture.

“Absurd!” she cried. “Do you think I would let you go with me into that wilderness, little mother? Besides,” she added, laughing, “I doubt very much if the director would consent to board the whole family. My one appetite may appal him and make him repent his bargain. And I shall not be gone very long—only until June.”

So it was settled, and the next day the superintendent formally recommended Miss Elizabeth Andrews as the teacher for the Wentworth school. In due time came the reply, directing her to report for duty at once, and she arrived at her journey’s end one bright day in late September.

She had determined from the first to make the people love her, but she found them another race from the genial, cultured, open-hearted Virginians who live along the James. Years of labor in the mines had marred their brains no less than their bodies; both, shut out from God’s pure air, and blue sky, and beautiful, green-clad world, grew crooked and misshapen, just as everything must do that has life in it.

She had gone to work among them with brave face but trembling heart. There was no lack of children in the grimy cabins; it made her soul sick to look at them. She asked that she might be permitted to teach them. But she encountered a strange apathy. The parents looked at her with suspicion. She was not one of them; why should she wish to meddle? Besides, the boys must help the men; the girls must help the women—even a very small girl can take care of a baby, and so lift that weight from the mother’s shoulders.

“But have the children never been sent to school?” she asked.

No, they said, never. The other teachers didn’t bother them. Why should she? The children could grow up as their parents had. They had other things to think about besides going to school. There was the coal to be dug.

A few of the better families sent their children, however—the superintendent, the school directors, the mine bosses, the fire bosses,—in the mines, every one is a “boss” who is paid a fixed monthly wage by the company,—but Bessie Andrews found herself every day looking over the vacant forms in the little schoolhouse and telling herself that she had failed—that she had not reached the people who most needed it.

More than once had she been tempted to confess her defeat, resign the place, and return to Richmond; yet the sympathy and encouragement of Jabez Smith, the director who had secured her appointment, gave her strength to keep up the fight. A simple, homely man, a justice of the peace and postmaster of Wentworth, he had welcomed her kindly, and she had found his house a place of refuge.

“You’ll git discouraged,” he had said to her the first day, “but don’t you give up. Th’ people up here ain’t th’ kind you’ve been used to, an’ it takes ’em some little time t’ git acquainted. You jest keep at it, an’ you’ll win out in the end.”

There was another, too, who spoke words of hope and comfort—the Rev. Robert Bayliss, minister of the little church on the hillside, who had come, like herself, a pilgrim into this wilderness.

“You are doing finely,” he would say. “Why, look at me. I’ve been here four years, and am almost as far from my goal as you are; but I’m not going to give up the fight till I get every miner and every miner’s wife into that church. As yet, I haven’t got a dozen of them.”

And as she glanced askant at his firm mouth and determined chin, she decided inwardly that this was the kind of man who always won his battles, whether of the spirit or of the flesh.

As she stood there in the school-house door, thinking of all this and looking out across the valley, she heard the whistle blow at the drift-mouth, a signal that no more coal would be weighed that day; and in a few moments she saw a line of men coming down the hillside toward her. She waited to see them pass,—grimy, weary, perspiring, fresh from the mine and the never-ending battle with the great veins of coal,—and she noted sadly how many boys there were among them. Some of them glanced at her shyly and touched their hats, but the most went by without heeding her, the younger, the driver-boys, laughing and jesting among themselves, the older tramping along in the silence of utter fatigue. She watched them as they went, and then turned slowly back into the room and picked up her hat.

“SHE TURNED QUICKLY AND SAW STANDING THERE ONE OF THE BOYS.”

“Please, ma’am—” said a timid voice at the door.

She turned quickly and saw standing there one of the boys who had passed a moment before.

“Yes?” she questioned, encouragingly. “Come in, won’t you?”

The boy took off his cap and stepped bashfully across the threshold.

“Sit down here,” she said, and herself took the seat opposite. “Now what can I do for you?”

He glanced up into her eyes. There was no mistaking their kindliness, and he gathered a shade more confidence.

“Please, ma’am,” he said, “I wanted t’ ask you t’ read this bill t’ me,” and he produced from his pocket a gaudy circus poster. “They’s been put up down at th’ deepot,” he added, in explanation, “but none of us boys kin read ’em.”

She took the bill from him with quick sympathy.

“Of course I’ll read it to you,” she cried. And she proceeded to recount the wonders of “Bashford’s Great and Only Menagerie and Hippodrome” as described by the poster. Most of the high-flown language was, of course, quite beyond the boy’s understanding, but he sat with round eyes fixed on her face till she had finished. It was a minute before he could speak.

“What is that thing?” he asked at last, pointing to a great, unwieldy beast with wide-open mouth.

“That’s a hippopotamus.”

“A—a what?” he asked wonderingly.

“A hippopotamus—a river-horse.”

“A river-horse,” he repeated; and his eyes grew rounder than ever. “A horse what lives in th’ river? But it ain’t a horse,” he added, looking at it again to make certain. “It ain’t nothin’ like a horse.”

“No,” said Miss Andrews, smiling, “it’s not a horse. That’s only a name for it. See, here it is,” and she pointed to the line below the picture. “‘The Hippopotamus, the Great African River Horse.’”

He gazed at the line a moment in silence. Then he sighed.

“I must go,” he said, and reached out his hand for the bill.

“But you haven’t told me your name yet,” she protested. “What is your name?”

“Tommy Remington,” he answered, his shyness back upon him in an instant.

“And your father’s a miner?”

He nodded. She looked at him a moment without speaking, rapidly considering how she might say best what she wished to say.

“Tommy,” she began, “wouldn’t you like to learn to read all this for yourself—all these books, all these stories,” and she waved her hand toward the little shelf above her desk. “It is a splendid thing—to know how to read!”

He looked at her with eyes wide opened.

“But I couldn’t!” he gasped incredulously. “None of th’ boys kin. Why, even none of th’ men kin—none I know.”

“Oh, yes, you could!” she cried. “Any one can. The reason none of the other boys can is because they have never tried, and the men probably never had a good chance. Of course you can’t learn if you don’t try. But it’s not at all difficult, when one really wants to learn. If you’ll only come and let me teach you!”

He glanced again at her face and then out across the valley. The shadows were deepening along the river, and above the trees upon the mountain-side great columns of white mist circled slowly upward.

“Promise me you’ll come,” she repeated.

The boy looked back at her, and she saw the light in his eyes.

“My father—” he began, and stopped.

“I’ll see your father,” she said impetuously. “Only you must tell him you want to come, and ask him yourself. Promise me you’ll do that.”

There was no resisting her in her great earnestness.

“I promise,” he whispered, and stooped to pick up his cap, which had fallen from his trembling fingers.

“If he refuses, I will see him to-morrow myself,” she said. “Remember, you are going to learn to read and write and to do many other things. Good night, Tommy.”

“Good night, ma’am,” he answered with uncertain voice, and hastened away.

She watched him until the gathering darkness hid him, and then turned back, picked up her hat again, locked the door, and hurried down the path with singing heart. It was her first real victory—for she was certain it would prove a victory—and she felt as the traveler feels who, toiling wearily across a great waste of Alpine snow and ice,—shivering, desolate,—comes suddenly upon a delicate flower, looking up at him from the dreary way with a face of hope and comfort.

Tommy Remington, meanwhile, trudged on through the gathering darkness, his heart big with purpose. Heretofore the mastery of the art of reading had appeared to him, when he considered the subject at all, as a thing requiring such tremendous effort as few people were capable of. Certainly he, who knew little beyond the rudiments of mining and the management of a mine mule, could never hope to solve the mystery of those rows of queer-looking characters he had seen sometimes in almanacs and old newspapers, and more recently on the circus poster he carried in his pocket. But now a new and charming vista was of a sudden opened to him. The teacher had assured him that it was quite easy to learn to read,—that any one could do so who really tried,—and he rammed his fists deep down in his pockets and drew a long breath at the sheer wonder of the thing.

It is difficult, perhaps, for a boy brought up, as most boys are, within sound of a school bell, where school-going begins inevitably in the earliest years, where every one he knows can read and write as a matter of course, and where books and papers form part of the possessions of every household, to understand the awe with which Tommy Remington thought over the task he was about to undertake. Such a boy may have seen occasionally the queer picture-writing in front of a Chinese laundry or on the outside of packages of tea, and wondered what such funny marks could possibly mean. To Tommy English appeared no less queer and difficult than Chinese, and he would have attacked the latter with equal confidence—or, more correctly, with an equal lack of confidence.

But he had little time to ponder over all this, for a few minutes’ walk brought him to the dingy cabin on the hillside which—with a similar dwelling back in the Pennsylvania coal-fields—was the only home he had ever known. His father had thrown away his youth in the Pennsylvania mines while the industry was yet almost in its infancy and the miners’ wages were twice or thrice those that could be earned by any other kind of manual labor—the high pay counter-balancing, in a way, the great danger which in those days was a part of coal-mining. Mr. Remington had, by good fortune, escaped the dangers, and had lived to see the importation of foreign laborers to the Pennsylvania fields,—Huns, Slavs, Poles, and what not,—who prospered on wages on which an Anglo-Saxon would starve. Besides, the dangers of the work had been very materially reduced, and to the mine-owner it seemed only right that the wages should be reduced with them, especially since competition had become so close that profits were cut in half, or sometimes even wiped out altogether.

It was just at the time when matters were at their worst that the great West Virginia coal-fields were discovered and a railroad built through the mountains. Good wages were offered experienced miners, and Mr. Remington was one of the first to move his family into the new region—into the very cabin, indeed, where he still lived, and which at that time had been just completed. The unusual thickness of the seams of coal, their accessibility, and the ease with which the coal could be got to market, together with the purity and value of the coal itself, all combined to render it possible for the miner to make good wages, and for a time Remington prospered—as much, that is, as a coal-miner can ever prosper, which means merely that he can provide his family with shelter from the cold, with enough to eat, and with clothes to wear, and at the same time keep out of debt. But the discovery of new fields and the ever-growing competition for the market had gradually tended to decrease wages until they were again almost at the point where one man could not support a family, and his boys—mere children sometimes—went into the mines with him to assist in the struggle for existence—the younger ones as drivers of the mine mules, which hauled the coal to “daylight,” the older ones as laborers in the chambers where their fathers blasted it down from the great seams.

Tommy mounted the steps of the cabin to the little porch in front, and paused for a backward glance down into the valley. The mountains had deepened from green to purple, and the eddying clouds of mist showed sharply against this dark background. The river splashed merrily along, a ribbon of silver at the bottom of the valley. The kindly night had hidden all the marks of man’s handiwork along its banks, and the scene was wholly beautiful. Yet it was not at mountains or river that the boy looked. He had seen them every day for years, and they had ceased to be a novelty long since. He looked instead at a little white frame building just discernible through the gloom, and he thought with a strange stirring of his blood that it was perhaps in that building he was to learn to read and write. A shrill voice from the house startled him from his reverie.

“Tommy,” it called, “ain’t you ever comin’ in, or air you goin’ t’ stand there till jedgment? Come right in here an’ wash up an’ git ready fer supper. Where’s your pa?”

“Yes’m,” said Tommy, and hurried obediently into the house. “Pa went over t’ th’ store t’ git some bacon. He said he’d be ’long in a minute.”

Mrs. Remington sniffed contemptuously and banged a pan viciously down on the table.

“A minute,” she repeated. “I guess so. Half an hour, most likely, ef he gits t’ talkin’ with thet shif’less gang thet’s allers loafin’ round there.”

Tommy deemed it best to make no reply to this remark, and in silence he took off his cap and jumper and threw them on a chair. Even in the semi-darkness it was easy to see that the house was not an inviting place. Perched high up on the side of the hill, it had been built by contract as cheaply as might be, and was one of a long row of houses of identical design which the Great Eastern Coal Company had constructed as homes for its employees. Three rooms were all that were needed by any family, said the company—a kitchen and two bedrooms. More than that would be a luxury for which the miners could have no possible use and which would only tend to spoil them. Perhaps the houses were clean when they were built, but the grime of the coal-fields had long since conquered them and reduced them to a uniform dinginess. Mrs. Remington had battled valiantly against the invader at first; but it was a losing fight, and she had finally given it up in despair. The dust was pervading, omnipresent, over everything. It was in the water, in the beds, in the food. It soaked clothing through and through. They lived in it, slept in it, ate it, drank it. Small wonder that, as the years passed, Mrs. Remington’s face lost whatever of youth and freshness it had ever had, and that her voice grew harsh and her temper most uncertain.

“Now hurry up, Tommy,” she repeated. “Wash your hands an’ face, an’ then fetch some water from th’ spring. There ain’t a drop in the bucket.”

“All right, ma,” answered the boy, cheerfully. And he soon had his face and hands covered with lather. It was no slight task to cleanse the dust from the skin, for it seemed to creep into every crevice and to cling there with such tenacious grip that it became almost a part of the skin itself. But at last the task was accomplished, as well as soap and water could accomplish it, and he picked up the bucket and started for the spring.

The air was fresh and sweet, and he breathed it in with a relish somewhat unusual as he climbed the steep path up the mountain-side. He placed the bucket under the little stream of pure, limpid water that gushed from beneath a great ledge of rock, summer and winter, fed from some exhaustless reservoir within the mountain, and sat down to wait for it to fill. A cluster of lights along the river showed where the town stood, and he heard an engine puffing heavily up the grade, taking another train of coal to the great Eastern market. Presently its headlight flashed into view, and he watched it until it plunged into the tunnel that intersected a spur of the mountain around which there had been no way found. What a place it must be,—the East,—and how many people must live there to use so much coal! The bucket was full, and he picked it up and started back toward the house. As he neared it, he heard his mother clattering the supper-things about with quite unnecessary violence.

“Your pa ain’t come home yit,” she cried, as Tommy entered. “He don’t need t’ think we’ll wait fer him all night. I’ll send Johnny after him.” She went to the front door. “John-ny—o-o-o-oh, Johnny!” she called down the hillside.

“Yes’m,” came back a faint answer.

“Come here right away,” she called again; and in a moment a little figure toddled up the steps. It was a boy of six—Tommy’s younger brother. All the others—brothers and sisters alike—lay buried in a row back of the little church. They had found the battle of life too hard amid such surroundings, and had been soon defeated.

“Where you been?” she asked, as he panted up, breathless.

“Me an’ Freddy Roberts found a snake,” he began, “down there under some stones. He tried t’ git away, but we got him. I’m awful hungry,” he added, as an afterthought.

But his mother was not listening to him. She had caught the sound of approaching footsteps down the path.

“Take him in an’ wash his hands an’ face, Tommy,” she said grimly. “Look at them clothes! I hear your pa comin’, so hurry up.”

Johnny submitted gracefully to a scrubbing with soap and water administered by his brother’s vigorous arm, and emerged an almost cherubic child so far as hands and face were concerned, but no amount of brushing could render his clothes presentable. His father came in a moment later, a little, dried-up man, whose spirit had been crushed and broken by a lifetime of labor in the mines—as what man’s would not? He grunted in reply to his wife’s shrill greeting, laid a piece of bacon on the table, and calmly proceeded with his ablutions, quite oblivious of the storm that circled about his head. Supper was soon on the table, a lamp, whose lighting had been deferred to the last moment for the sake of economy, was placed in the middle of the board, and Mrs. Remington, finding that her remarks upon his delay met with no response, sat down behind the steaming coffee-pot to show that she would wait no longer.

Hard labor and mountain air are rare appetizers, and for a time they ate in silence. At last Johnny, having taken the edge off his hunger, began to relate the story of his thrilling encounter with the snake, and even his mother was betrayed into a smile as she looked at his dancing eyes. Tommy, who had been vainly striving to muster up courage to broach the subject nearest his heart, saw his father’s face soften, and judged it a good time to begin.

“Pa,” he remarked, “there’s a circus comin’, ain’t they?”

“Yes,” said his father; “I see some bills down at the mine.”

“When’s it comin’?”

“I don’t know. You kin ask somebody. Want t’ go?”

Mrs. Remington snorted to show her disapproval of the proposed extravagance.

“No, it ain’t that,” answered Tommy, in a choked voice. “I don’t keer a cent about th’ circus. Pa, I want t’ go t’ school.”

Mr. Remington sat suddenly upright, as though something had stung him on the back, and rubbed his head in a bewildered way. His brother stared at Tommy, awe-struck.

“Go t’ school!” repeated his father, at last, when he had conquered his amazement sufficiently to speak. “What on airth fer?”

“T’ learn how t’ read,” said Tommy, gathering courage from his father’s dismay. “Pa, I want t’ know how t’ read an’ write. Why, I can’t even read th’ show-bill!”

“Well,” said his father, “neither kin I.”

Tommy stopped a moment to consider his words, for he felt he was on delicate ground. In all his fourteen years of life, he had never been so desperate as at this moment.

But his mother came unexpectedly to his rescue.

“Well, an’ if you can’t read, Silas,” she said sharply, “is thet any reason th’ boy shouldn’t git a chance? Maybe he won’t hev t’ work in th’ mines ef he gits a little book-l’arnin’. Heaven knows, it’s a hard life.”

“Yes, it’s a hard life,” assented the miner, absently. “It’s a hard life. Nobody knows thet better ’n me.”

Tommy looked at his mother, his eyes bright with gratitude.

“I stopped at th’ school-house t’ git th’ teacher t’ read th’ bill t’ me,” he said, “an’ she told me thet anybody kin learn t’ read—thet ’tain’t hard at all. It’s a free school, an’ it won’t cost nothin’ but fer my books. I’ve got purty near three dollars in my bank. Thet ort t’ pay fer ’em.”

“But who’ll help me at th’ mine?” asked his father. “I’ve got t’ hev a helper, an’ I can’t pay one out of th’ starvation wages th’ company gives us. What’ll I do?”

“I tell you, pa,” said Tommy, eagerly. “I kin help you in th’ afternoons, an’ all th’ time in th’ summer when they ain’t no school. I’ll jest go in th’ mornin’s, an’ you kin keep on blastin’ till I git there t’ help y’ load. I know th’ boss won’t keer. Kin I go?”

His face was rosy with anticipation. His father looked at him doubtfully a moment.

“Of course you kin go,” broke in his mother, sharply. “You’ve said yourself, Silas, many a time,” she added to her husband, “thet th’ minin’ business’s gittin’ worse an’ worse, an’ thet a man can’t make a livin’ at it any more. Th’ boy ort t’ hev a chance.”

Tommy shot another grateful glance at his mother, and then looked back at his father. He knew that from him must come the final word.

“You kin try it,” said his father, at last. “I reckon you’ll soon git tired of it, anyway.”

But Tommy was out of his chair before he could say more, and threw his arms about his neck.

“I’m so glad!” he cried. “You’ll see how I’ll work in th’ afternoons. We’ll git out more coal ’n ever!”

“Well, well,” protested Silas, awkwardly returning his caress, “we’ll see. I don’t know but what your ma’s right. You’ve been a good boy, Tommy, an’ deserve a chance.”

And mother and father alike looked after the boy with unaccustomed tenderness as he ran out of the house and up the mountain-side to think it all over. Up there, with only the stars to see, Tommy flung himself on the ground and sobbed aloud in sheer gladness of heart.

When Bessie Andrews came within sight of the door of the little schoolhouse next morning, she was surprised to see a boy sitting on the step; but as she drew nearer, she discovered it was her visitor of the evening before. He arose when he saw her coming and took off his cap. Cap and clothes alike showed evidence of work in the mines, but face and hands had been polished until they shone again. Her heart leaped as she recognized him, for she had hardly dared to hope that her talk with him would bear such immediate and splendid fruit. Perhaps this was only the beginning, she thought, and she hurried forward toward him, her face alight with pleasure.

“Good morning,” she said, holding out her hand. “Your father said yes? I’m so glad!”

He placed his hand in hers awkwardly. She could feel how rough and hard it was with labor—not a child’s hand at all.

“Yes’m,” he answered shyly. “Pa said I might try it.”

“Come in”; and she unlocked the door and opened it. “Sit down there a minute till I take off my things.”

He sat down obediently and watched her as she removed her hat and gloves. The clear morning light revealed to him how different she was from the women he had known—a difference which, had it been visible the evening before, might have kept him from her. His eyes dwelt upon the fresh outline of her face, the softness of her hair and its graceful waviness, the daintiness of her gown, which alone would have proclaimed her not of the coal-fields, and he realized in a vague way how very far she was removed from the people among whom he had always lived.

“SHE HURRIED FORWARD TOWARD HIM, HER FACE ALIGHT WITH PLEASURE.”

“Now first about the studies,” she said, sitting down near him. “Of course we shall have to begin at the very beginning, and for a time you will be in a class of children much younger than yourself. But you mustn’t mind that. You won’t have to stay there long, for I know you are going to learn, and learn rapidly.”

She noticed that he was fumbling in his pocket and seemed hesitating at what to say.

“What is it?” she asked.

“I’ll need some books, I guess,” he stammered. “Pa’s been givin’ me a quarter of a dollar every week fer a long time fer helpin’ him at th’ mine, an’ I’ve got about three dollars saved up.”

With a final wrench he produced from his pocket a little toy bank, with an opening in the chimney through which coins could be dropped inside, and held it toward her.

“Will that be enough?” he asked anxiously.

The quick tears sprang to her eyes as she pressed the bank back into his hands.

“No, no,” she protested. “You won’t need any books at all at first, for I will write your lessons on the blackboard yonder. After that, I have plenty of books here that you can use. Keep the money, and we’ll find a better way to spend it.”

He looked at her doubtfully.

“A better way?” he repeated, as though it seemed impossible there could be a better way.

“Yes. You’ll see. You’ll want something besides mere school-books before long. Put your bank in your pocket,” she added. “Here come the other children.”

He put it back reluctantly, and in a few minutes had made the acquaintance of the dozen children which were all that Miss Andrews had been able to bring together. Most of them belonged to the more important families of the neighborhood. Tommy, of course, had never before associated with them, and he felt strangely awkward and embarrassed in their presence. He reflected inwardly, however, that he could undoubtedly whip the biggest boy in the crowd in fair fight; but all the reassurance that came from his physical strength was presently taken out of him when he heard some of them, much younger than himself, reading with more or less glibness from their books.

He himself had his first struggle with the alphabet, and before the hour ended had mastered some dozen letters. He rejoiced when he learned that there were only twenty-six, but his heart fell again when he found that each of them had two forms, a written and a printed form, and that there were two variations of each form, capitals and small letters. Between these he was, as yet, unable to trace any resemblance or connection; but he kept manfully at work, attacking each new letter much as a great general attacks each division of the enemy’s army, until he has overcome them all. And it is safe to say that no general ever felt a greater joy in his conquests.

It is not an easy thing for a boy totally unused to study to undertake a task like this, and more than once he found his attention wandering from the board before him, where the various letters were set down. He wondered how his father was getting along at the mine without him; he caught himself gazing through the window at the cows on the hillside opposite; he had an impulse to run to the door and watch the New York express whirl by. The hum of the children about him, reciting to the teacher or conning their lessons at their desks, set his head to nodding; but he sat erect again heroically, rubbed his eyes, and went back to his task. The teacher was watching him, and smiled to herself with pleasure at this sign of his earnestness.

I think the greatest lesson he learned that morning—the lesson, indeed, which it is the end of all education to teach—was the value of concentration, of keeping his mind on the work in hand. The power he had not yet acquired, of course,—very few people, and they only great ones, ever do acquire it completely,—yet he made a long stride forward, and when at last noon came and school was dismissed, he started homeward with the feeling that he had won a victory.

That afternoon, as he worked beside his father in the mine, loading the loosened coal into the little cars, and pushing them down the chamber to be hauled away, he kept repeating the letters to himself, and from time to time he took from his pocket the soiled circus poster, and holding it up before his flickering lamp, picked out upon it the letters that he knew, to make certain he had not forgotten them. His father watched him curiously, but made no comment, being somewhat out of humor from having to work alone all the morning. Yet this passed in time, for Tommy labored with such purpose and good will that when the whistle blew their output was very nearly as large as it ever was.

After supper that evening, Tommy hurried forth to the hillside, and flinging himself face downward on the ground, spread out the bill before him and went over and over it again so long as the light enabled him to distinguish one letter from another, until he was quite certain he could never forget them.

At the end of a very few days he knew his alphabet, but, to his dismay, he found this was only the first and very easiest step toward learning to read. Those twenty-six letters were capable of an infinite number of combinations, and each combination meant a different thing. It was with a real exultation he conquered the easiest forms,—“cat” and “dog” and “ax” and “boy,”—and after that his progress was more rapid.

“HE PICKED OUT THE LETTERS HE KNEW, TO MAKE CERTAIN HE HAD NOT FORGOTTEN THEM.”

It is always the first steps which are the most difficult, and as the weeks passed he was regularly promoted from one class to another. The great secret of his success lay in the fact that he did not put his lessons from him and forget all about them the moment the school door closed behind him, but kept at least one of his books with him always. His mother even went to the unprecedented extravagance of keeping a lamp burning in the evening that he might study by it, and hour after hour sat there with him, sewing or knitting, and glancing proudly from time to time at his bowed head. They were the only ones awake, for husband and younger child always went to bed early, the one worn out by the day’s work, the other by the day’s play.

To Tommy those days and evenings were each crowded with wonders. He learned not only that the letters may be combined into words, but that the ten figures may be combined into numbers. The figures, indeed, admitted of even more wonderful combinations, for they could be added and subtracted and multiplied and divided one by another, something that could not be done with letters at all, which seemed to him a very singular thing.

The first triumph came one evening when, after questioning his father as to the amount of coal he had mined that day and the price he was paid for each ton of it, he succeeded in demonstrating how much money he had earned, reaching exactly the same result that his father had reached by means of some intricate method of reckoning understood only by himself. It was no small triumph, for from that moment his father began dimly to perceive that all of this book-learning might one day be useful. So when winter and spring had passed, and the time drew near for dismissing the school for the summer, Tommy could not only read fairly well and write a little, but could do simple sums in addition and subtraction, and knew his multiplication-table as high as seven. Small wonder his mother looked at him proudly, and that even his father was a little in awe of him!

It was about a week before the end of the term that Miss Andrews called him to her.

“You remember, Tommy,” she asked, “that I told you we would use your money for something better than buying mere school-books?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said; “I remember.”

“Well, bring me one dollar of it, and I will show you what I meant when I told you that.”

So the next day he placed the money in her hands, and a few days later she called him again.

“I have something for you,” she said, and picked up a package that was lying on her desk. “Unwrap it.”

He took off the paper with trembling fingers, and found there were four books within.

“They are yours,” she said. “They were bought with your money, and you are to read them this summer. This one is ‘Ivanhoe,’ and was written by a very famous man named Sir Walter Scott; this is ‘David Copperfield,’ and was written by Charles Dickens; this is ‘Henry Esmond,’ and was written by William Makepeace Thackeray; and this last one is ‘Lorna Doone,’ by Richard Doddridge Blackmore. They are among the greatest stories that have ever been written in the English language, and I want you to read them over and over. You may not understand quite all of them at first, but I think you will after a time. If there is anything you find you cannot understand, go to Mr. Bayliss at the church, and ask him about it. He has told me that he will be glad to help you.”

Tommy tied up his treasures again, too overcome by their munificence to speak, and when he started for home that noon, he was holding them close against his breast.

Miss Andrews looked after him as he went, and wondered, for the hundredth time, if the books she had given him had been the wisest selection. His first youth was past, she had reasoned, and he must make the most of what remained. So she had finally decided upon these four masterpieces. She sighed as she turned away from the door, perhaps with envy at thought of the rare delights which lay before him in the wonderful countries he was about to enter.

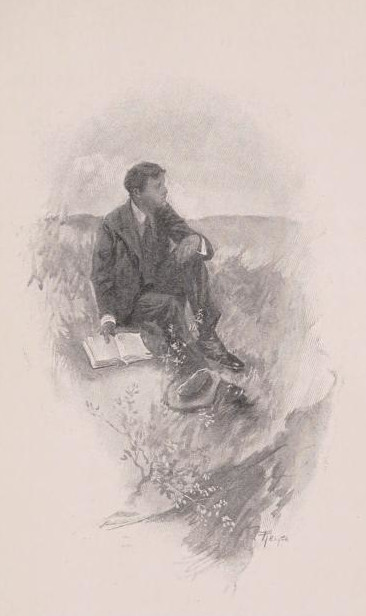

And what delights they were, when once he found time to taste of them! He was kept busy at his studies until school closed, as it did one Friday in early June, and that afternoon he said good-by to his teacher and saw her whisked away eastward to the home she loved. He went from the station to the mine with heavy heart, and labored there with his father until evening came. He did not open his books that night, for he was just beginning to realize all that his teacher had been to him and how he had come to rely upon her for encouragement and help. All day Saturday he worked in the mine with his father. But Sunday dawned clear and bright, and as soon as he had eaten his breakfast, he climbed high up on the hillside to his favorite nook, with only “Lorna Doone” for company. There, in a grassy spot, he lay down and opened the book before him.

He read it stumblingly and haltingly; as his teacher had foreseen, many of the words were quite beyond him; but it was written in English so pure, so clear, so simple, that little of importance escaped him. And what a world of enchantment it opened to him!—the wide moorlands of Exmoor, the narrow Doone valley, the water-slide, the great London road. And what people, too!—the lawless Doones, Captain, Counselor, Carver, who, for all their villainy, had something attractive about them, Lorna, and great John Ridd. Of course he did not see the full beauty of the book, but its magic he caught some glimpses of, and it bore him quite away from the eventless valley of New River to that other valley where the Doones reigned in all their insolence and pride, and kept Lorna prisoner to be a bride to Carver.

Hunger warned him of the dinner-hour, but he begrudged the time it took to go down to the house, swallow his food, and get back again to his place on the hillside. The afternoon passed almost before he knew it, and the lengthening shadows warned him that evening was at hand. Still he read on, glancing up only now and then to mark how the light was fading, and when it failed altogether it left John just in the midst of his adventures in London. Tommy lay for a long time looking down the valley and thinking over what he had read, and at last, with a sigh, picked up the book and started homeward.

What need to detail further? All summer long he walked in a land of enchantment, whether with John Ridd on Exmoor, with David Copperfield in London, with Richard Lion-heart in Sherwood Forest, or with Henry Esmond at Castlewood. As he went onward he grew stronger in his reading, and so found the way less difficult, and at last acquired such proficiency that he would read portions of his books aloud to his wondering parents and to Johnny.

Mr. Bayliss found them sitting so one Sunday afternoon, and paused at the porch to listen. Tommy was reading of that last desperate struggle between John Ridd and Carver Doone:

“The black bog had him by the feet; the sucking of the ground drew on him like the thirsty lips of death. In our fury, we had heeded neither wet nor dry, nor thought of earth beneath us. I myself might scarcely leap, with the last spring of o’erlabored legs, from the engulfing grave of slime. He fell back with his swarthy breast (from which my gripe had rent all clothing) like a hummock of bog-oak standing out the quagmire; and then he tossed his arms to heaven, and they were black to the elbow, and the glare of his eyes was ghastly. I could only gaze and pant, for my strength was no more than an infant’s, from the fury and the horror. Scarcely could I turn away, while, joint by joint, he sank from sight.”

For an instant there was silence. Then, with a sigh, Tommy’s father relaxed his attitude of strained attention and dropped back in his chair.

“Jee-rusalem!” he said at last. “Ter think of it! Th’ bog swallered him up. Good fer him! He ort t’ got worse ’n thet fer killin’ Lorna.”

Tommy smiled to himself, in his superior knowledge.

“That ain’t all,” he said. “There’s another chapter.”

“Another chapter!” cried his father. “Maybe Lorna ain’t dead, then. It’ll tell about her funeral, anyway. Go on, Tommy.”

And as Tommy turned to the book again, Mr. Bayliss stole away down the path, convinced that this was not the time to make his presence known. On his homeward way he pondered deeply the scene he had just witnessed. Its significance moved him strongly, for he saw a ray of hope ahead for the success of his ministry among this people. Five years before, when he was a senior at the Princeton Theological Seminary, he had chanced upon an open letter in a mission magazine which stated that for miles and miles along this valley there was not a single minister nor church, and that hundreds of people, from year-end to year-end, never heard the Word of God. He had decided that this should be his field of labor, and so soon as he had been ordained he had journeyed to Wentworth. At first he had held services in an old cabin; gradually he succeeded in interesting charitable people in his work, and finally secured enough money to build a small church, and to purchase and consecrate a piece of ground behind it for a burying-place.

But in matters of religion, as in matters of education, he had found the people strangely apathetic. They came to him to be married, and sent for him sometimes in sickness; it was he who committed their bodies to the grave: but marriages and deaths aside, he had small part in their lives. He had thought sometimes that the reason of failure must be some fault in himself, and had his moments of discouragement, as all men have; but the scene he had just witnessed gave him a clue to one cause of failure. He saw that some degree of education must come before there could be deep and genuine spiritual awakening. He had realized the truth of this more than once in his ministry, but most deeply shortly after his arrival, when he had undertaken to distribute some Bibles among the squalid cabins on the hillside.

“We-uns don’t need no Bible,” said the woman in the first house he entered.

“Do not need one?” he echoed. “Why? Have you one in the house already?”

“No, we ain’t got none. What could we-uns do with one?”

“Do with it? Read it, of course.”

“But we can’t read,” said the woman, sullenly. “They ain’t no chance t’ learn. It’s work, work, from sun-up t’ dark.”

Mr. Bayliss stood for a moment nonplussed.

“Not read!” he repeated at last. “But, surely, some of the miners or their families can read.”

The woman shook her head.

“Not many,” she said. “How kin we?” she continued, more fiercely. “What chance d’ we hev? We ain’t knowed nothin’ but work all our lives. A man don’t stop t’ learn t’ read when he needs bread t’ eat.”

She paused to look darkly at her visitor. He was so moved with pity and distress that he could find no answer. Perhaps she read his thought in his eyes, for she grew more gentle.

“Thet’s one reason we-uns don’t come down t’ them meetin’s o’ yourn,” she went on. “By th’ time Sunday comes, we’re too tired t’ care fer anything but rest. And then,” she added defiantly, “most of us has got so we don’t care, noway.”

Mr. Bayliss went back to his study with his Bibles still under his arm. He felt that he was just beginning to understand the problem which confronted him, and he had sought vainly for a solution to it. Since the miners could not read, he had visited such of them as would permit him and had read to them, but they had received him for the most part with indifference. He had labored patiently, though sometimes despairingly. And now, of a sudden, after these years, he saw a glimmering of light. It was only a miner’s boy reading to his parents—a little thing, perhaps, yet even little things sometimes lead to great ones. And the minister determined to do all he could for that boy, that he might serve as a guide to others.

He found he could do much. He helped the boy over difficult places in his books, gave him a dictionary that he might find out for himself the meaning of the words, and taught him how to use it. Gradually, as he came to know him better, the project, which at first had been very vague, began to take shape in his mind. Why should not this boy become a helper to his own people? Who could understand them and minister to them as one who had sprung from among them? But of this he said nothing to any one, only pondered it more and more.

It was quite a different Tommy from the one she had known that Miss Andrews found awaiting her when she returned in September to open her school again. His eyes had a new light in them. It was as if a wide, dreary landscape had been suddenly touched and glorified by the sun. On his face, now, glowed the sunlight of intelligence and understanding—a light which deep acquaintance with the books Tommy had been reading will bring to any face. She had a talk with him the very first day.

“And you liked the books?” she asked.

His sparkling eyes gave answer.

“Which hero did you like the best?”

“Oh, John Ridd,” he cried. “John Ridd best of all. He was so big, so strong, so brave, so—”

He paused, at loss for a word.

“So steadfast,” she said, helping him, “so honest, so good, so true. Yes, I think I like him best, too—better than David or Ivanhoe or Henry Esmond. And now, Tommy,” she continued, more seriously, “I want you to do something for me—something I am sure you can do, and which will help me very much.”

“Oh, if I could!” he cried, with bright face.

“I am sure you can. How many children do you suppose there are in that row of houses where you live?”

He stopped for a moment to compute them.

“About twenty-five,” he said at last.

“And how many of them come to school?”

“None of them but me.”

“Don’t you think they ought to come? Aren’t you glad that you came?”

“Oh, yes!” cried Tommy.

“Well, I have tried to get them to come, and failed,” she said. “Perhaps I didn’t know the right way to approach them. Now I want you to try. I believe you will know better how to reach them than I did. You may fail, too, but at least you can try.”

“I will try,” he said, and that evening he visited all the cabins in the row, one after another. What arts he used was never known—what subtleties of flattery and promise. He met with much discouragement; for instance, he could get none of the men to consent to send to school any of the boys who were old enough to help them in the mines. But when he started to school next morning, six small children accompanied him, among them his brother Johnny. And what a welcome the teacher gave him! She seemed unable to speak for a moment, and her eyes gleamed queerly, but when she did speak, it was with words that sent a curious warmth to his heart.

That half-dozen children was only the first instalment to come from the cabins. Tommy, prizing above everything his teacher’s gratitude, kept resolutely at work, and soon the benches at the schoolroom began to assume quite a different appearance from that they had had at the opening of school; and one day when Jabez Smith came down to look the school over, he declared that it would soon be necessary to put in some new forms.

“And you were gittin’ discouraged,” he said, half jestingly, to Miss Andrews. “Didn’t I tell you t’ stick to it an’ you’d win?”

“Oh, but it wasn’t I who won!” she cried. And in a few words she told him the story of Tommy’s missionary work, and of his connection with the school.

“Which is th’ boy?” he asked quickly, when the story was finished, and she pointed out Tommy where he sat bending over his book.

Mr. Smith looked at him for some moments without speaking.

“There must be somethin’ in th’ boy, Miss Bessie,” he said at last. “We must do somethin’ fer him. When you’re ready, let me know. Mebbe I kin help.” And he went out hastily, before she could answer him.

But the words sang through her brain. “Do something for him”—of course they must do something for him; but what? The question did not long remain unanswered.

It was when she met Mr. Bayliss one Sunday in a walk along the river, and related to him the success of Tommy’s efforts, that he broached the project he had been developing.

“The boy must be given a chance,” he said. “I believe he could do a great work among these people—greater, surely, than I have been able to do.” And he sighed as he thought of his years of effort and of the empty seats which confronted him at every service. “See how he has helped you. Now he must help me.”

“But how?” she asked. And old Jabez Smith’s promise again recurred to her.

“I haven’t thought it out fully, but in outline it is something like this. We will teach him here all that we can teach. Then we’ll send him to the preparatory school at Lawrenceville for the final touches. Then he will enter Princeton, and—if his bent lies as I believe it does—the seminary. Think what he could do, coming back here equipped as such a course would equip him, and having, too, a perfect understanding of the peculiar people he is to work among! Why, I tell you, it would almost work a miracle from one end of this valley to the other.” And he paused to contemplate for a moment this golden-hued picture which his words had conjured up.

His companion caught the glow of his enthusiasm.

“It would,” she cried; “it would! But can he take such a polish? Is he strong enough? Is it not too late?”

“I believe he is strong enough. I believe it is not too late. The only trouble,” he added reflectively, “will be about the cost.”

“The cost?”

“Yes. There will be no question of that after he gets to Princeton, for I can easily get him a scholarship, and there are many ways in which a student can earn money enough to pay his other expenses. But at Lawrenceville it is different.”

Miss Andrews looked up at him with dancing eyes.

“About what will the expense at Lawrenceville be?” she asked.

He paused a moment to consider.

“Say three hundred dollars a year. I think I can arrange for it not to cost more than that, if I can get him one of the Foundation Scholarships, as I am certain I can.”

“And the course?”

“Is four years—but we may be able to cut it down to three. Let us count on three.”

“Nine hundred dollars,” she said, half to herself. Then of a sudden, “Mr. Bayliss, I believe I can provide the money.”

“You!” he cried in astonishment.

“Oh, not I myself,” she laughed. “One of my friends. I will talk it over with him.”

He looked at her, still more astonished.

“Talk it over?” he repeated. “Do you mean to say that we have a philanthropist in our midst?”

She nodded.

“But I shall not tell you his name,” she said, her eyes alight. “Not just yet, at any rate. Let us get on to other particulars. I see another rock ahead in the person of his father. Do you think he will consent?”

“I had thought of that,” answered the minister, slowly. “That will be another great difficulty. But I believe he will consent if we go about it carefully. He is beginning to take a certain pride in the boy,—so is the mother,—and I shall appeal to that. It is worth trying.”

“Yes, it is worth trying,” she repeated, “and we will try.”

Tommy, who lay in his favorite spot high up on the mountain, reading for the tenth time of John Ridd’s fight for Lorna, saw them walking together along the river path. He watched them pacing slowly back and forth, deep in converse, but he had no thought that they were planning his life for him.

When one is fired with an idea, the wisest thing is to work it out immediately, and Miss Andrews lost no time in carrying through her part of the bargain. She knew Jabez Smith’s habits from a year’s observation, and that evening, after supper, she hunted him out where he sat on the back porch of the house, reflectively smoking his pipe. His preference for the back porch over the front porch was one of his peculiarities. From the front porch one could see the whole sweep of the valley, with its ever-changing beauties of light and shade. From the back one, nothing was visible but the imminent hillside mounting steeply upward.

To be sure, if one leaned forward in his chair, a glimpse might be had of the mouth of a coal-mine high up on the hillside, and his sister said that it was to look at this that Jabez sat on the back porch. It seemed likely enough, for it was from that drift that he had drawn enough money to make his remaining years comfortable. Jabez Smith had come into these mountains while they were yet a wilderness, unknown, or almost so, to white men, save where the highroads crossed them scores of miles apart. What circumstance had driven him from his home near Philadelphia was never known, but certain it was that he had plunged alone into the mountains, and battled through them until he had reached the New River valley. Caprice, or perhaps the beauty of the place, moved him to make his home here. He bought two hundred acres of land for half as many dollars, built himself a rude log cabin, and settled down, apparently to spend the remainder of his life in solitude.

Then came the discovery of the great beds of coal, and the building of the railroad through this very valley. His two hundred acres jumped in value to a thousand times what he had paid for them, and when the Great Eastern Coal Company was organized to develop the mines, he sold to them all of the land except a few acres which he reserved for his home. There he had built a comfortable house, and had sent for his widowed sister to come and live with him. He gradually grew to be something of a power in the place, and had been postmaster ever since an office had been established there. It was he who had secured money for the erection of the school-house, and he had been the only local contributor to Mr. Bayliss’s church. Still, he was a peculiar man, and bore the reputation of being harsh. Women said that was because he had never married. Men wondered why, with all his wealth, he should be content to spend his life in this humdrum and unattractive place. But he seemed to pay no heed to all these comments. He formed habits of peculiar regularity, and one of these was, as has been already said, to sit on the back porch after supper and smoke an evening pipe.

It was there he was that Sunday evening, and he turned as he heard steps on the porch behind him.

“Ah, Miss Bessie, good evenin’,” he said cordially. “Won’t y’ take a cheer?” And he waved his hand toward a little low rocker that stood in one corner. “I hope y’ don’t object t’ terbaccer,” he added, as she brought the chair forward and sat down.

“Do you suppose I should have come here to disturb you if I did?” she retorted laughingly. “I want you to keep on smoking. I know a man is always more inclined to grant a favor when he’s smoking.”

He glanced at her quickly, with just a trace of suspicion in his eyes, and moved uneasily in his chair.

“What’s th’ favor?” he asked.

“You remember I was telling you the other day about Tommy Remington,” she began, “and you said something must be done for the boy, and that you wished to help.”

“’Twasn’t exactly thet,” he corrected, smiling in spite of himself, “but thet’ll do.”

“Well, we have a plan,” she continued, “a good plan, I believe”; and she told him of her talk with Mr. Bayliss.

He sat silent for a long time after she had finished, smoking slowly, and looking at the hillside.

“I dunno,” he said at last. “I dunno. It’s a resky thing t’ send a boy out thet way. But mebbe it’ll turn out all right. As I understan’, it’ll take nine hunderd dollars t’ put it through.”

“Nine hundred,” she nodded.

He took a long whiff and watched the smoke as it circled slowly upward.

“Nine hunderd,” he repeated. “Thet’s a lot o’ money—a good bit o’ money. I’m afeard I ain’t got thet much t’ give away, Miss Bessie. I don’ believe in givin’ people money, anyways.”

He glanced at her and saw how her face changed. Her voice was trembling a little when she spoke.

“Very well, Mr. Smith,” she said. “Of course it is a lot of money. I had no right to ask you.” And she rose to go. “I’ll tell Mr. Bayliss, and we will find some other plan.”

“Set down!” he interrupted, almost roughly. “Set down, an’ wait till I git through.”

She sat down again, looking at him with astonishment not unmixed with fear.

“Now,” he continued, “I said I didn’t hev thet much money t’ give away, but thet ain’t sayin’ I ain’t got it t’ loan. Now I’m a business man. I don’ believe in fosterin’ porpers. If this yere Tommy o’ yourn shows he’s got th’ stuff in him t’ make a scholar, an’ you git his father t’ consent t’ his goin’ away, I’ll tell you what I’ll do, jest as a business proposition. I’ll loan him three hunderd dollars at five per cent., t’ be paid back when he earns it. Thet’ll pay fer one year, an’ I reckon I kin make th’ same proposition when th’ second an’ third years come round, pervided, of course, th’ boy turns out th’ way you expect. Ef ’t takes four years, why, all right.”

He stopped to get his pipe going again, and his hearer started from her chair with glistening eyes.

“Oh, Mr. Smith,” she began, but he waved her back.

“Set down, can’t yer?” he cried, more fiercely than ever; and she sank back again, beginning at last to understand something of this man. “I ain’t through yet. When you git ready fer the money, you come t’ me an’ I’ll make out th’ note. You kin take it t’ him an’ let him sign it. But I don’ want no polly-foxin’ roun’ me. I won’t stan’ it. You tell th’ boy t’ keep away from me, an’ don’ you let anybody else know about it, er I won’t loan him a cent.”

She sat looking at him, her lips trembling.

“Now you mind,” he repeated severely, shaking his pipe at her, but not daring to meet her eyes. “I won’t have no foolin’. Promise you’ll keep this t’ yourself.”

She was laughing now, her eyes bright with unshed tears.

“I promise,” she cried. “But oh, Mr. Smith, you can’t prevent my thinking, though you may prevent my talking. Do you want to know what I think of what you’ve done?”

He shook a threatening finger, but she was bending over him and looking down into his eyes.

“No, you can’t frighten me! I’m not in the least afraid of you, for I think you’re a dear, dear, dear!”

He half started from his chair, but she turned and fled into the house, casting one sparkling glance over her shoulder as she went. He sank back into his seat with a face quite the reverse of angry, and started up his pipe again, and as he gazed out at the hillside he was tasting one of the great sweetnesses of life.

That evening, at the close of the service in the little church, Miss Andrews waited for the minister, to tell him her good news.

“And who is this Good Samaritan?” he asked, when she had finished. “It may be business, as he says, but it’s rather queer business, it seems to me, to lend a boy nine hundred dollars, with no security but his own, and with an indefinite time in which to repay it. What could have persuaded him to do it?”

“Well,” she said thoughtfully, “he saw the boy.”

“And the boy had you to plead his cause,” he added, smiling at her. “Come, I’ll not ask you again who this mysterious benefactor is. Perhaps I suspect. I think I’ve had some dealings with him myself.”

“I knew it!” she cried, clapping her hands in her excitement. “I knew this was not the first time, the moment he began to talk harshly to me. Oh, you should have heard him!”

“I have heard him,” he laughed. “Yes, and felt him, too.”

“Tell me.”

He shook his head.

“He would not like it. Besides, I promised not to.”

“But you will mention no names,” she protested. “You will not tell me who he is. Surely, he could not object to that!”

“I fear that is a dangerous subtlety,” he said, smiling; “but it can do no harm, since you already know.”

Here is the story—with a few details about himself which the minister somehow neglected to give.

Three years before, there had been a strike in the mines of the Great Eastern Coal Company. What caused it is no matter now—some grievance, real or fancied, on the part of the miners. They had demanded redress, the company had refused to make any change in the existing order of things, and, in consequence, one morning, when the whistle blew, not a single man answered it, and the mines were shut down.

For a time things went much as usual in New River valley. The miners sat in front of their houses smoking, or gathered in little groups here and there to talk over the situation. But by degrees the appearance of contentment disappeared. None of the men had saved much money; many had none at all; still more were already in debt at the company store—they had got into the habit of exceeding their earnings there, of receiving, at the end of every month, instead of a pay envelope, a “snake statement,” with a zigzag line drawn from indebtedness to credit given. Further credit at the store was refused, and it was whispered about that the company meant to starve them into subjection. The faces of the men began to show an ominous scowl; the groups became larger and the talk took on a menacing tone. The reporters who had hurried to the scene telegraphed their papers that there would soon be trouble in the New River valley.

During all this time Mr. Bayliss had worked unceasingly to bring the strike to an end. He had labored with the officials of the company, and with the men. Both sides were obdurate. The men threatened violence; the company responded that in the event of violence it would call on the law to protect its property, and that the muskets of the troops would be loaded with ball. In the meantime the wives and children of the miners had no food, and things were growing desperate.

Just when matters were at their worst, a strange thing happened. One of the miners one morning found a sack of flour on his doorstep; another found a side of bacon; a third a basket of potatoes; a fourth, a measure of meal. Whence the gifts came no one knew; and no one tried to probe the mystery, for it was whispered about that it was bad luck to try to discover the giver, since he evidently wished to remain unknown. Word of all this came, of course, to Mr. Bayliss, and he wondered like the rest.

He was called, one night, to a cabin on the mountain-side, where a miner’s wife lay ill. It was not till long past midnight that she dropped asleep, and after comforting the husband and children as well as lay in his power, he left the cabin and started homeward. It was a clear, starlit night in late October, and he lingered on the way to breathe in the sweet, fresh fragrance of the woods—a pleasant contrast to the close cabin he had just left. As he paused for a moment to look along the valley, and wonder anew at its beauty, he heard footsteps mounting the path toward him, and glancing down, he saw a man approaching apparently carrying a heavy load. Wondering who it could be abroad at this hour, he stood where he was and awaited the stranger’s approach. But he did not come directly to him. He turned up a path which led to a cabin, and the watcher saw him place a bundle on the doorstep. With leaping heart, he understood. It was the man who had been saving the miners’ families from starvation.

His pulse was beating strangely as he saw the man return to the main path and again mount toward him. As he came opposite him, the minister stepped out of the shadow.

“My friend,” he said gently.

The stranger started as though detected in the commission of some crime, dropped the sacks he was carrying, and sprang upon the other.

“What d’ y’ mean?” he cried hoarsely, clutching him fiercely by the shoulders. “Spyin’, was y’?”

The minister smiled into his face, despite the pain his rough clasp caused him.

“No, I was not spying, Mr. Smith,” he said. “I came this way quite by accident. But I thank God for the accident that has made you known to me.”

Jabez Smith dropped his hands.

“The preacher!” he muttered, and looked at him shamefacedly. “Promise me you’ll fergit about this, Mr. Bayliss.”

“How can I promise what I can never do?” asked the other, with a smile. “I shall remember it night and morning in my prayers.”

“At least,” said Jabez, imploringly, “promise me you’ll tell nobody, sir. If y’ do tell,” he added fiercely, “it’ll stop right here!”

The minister smiled at him through a mist of tears.

“I’ll promise to tell no one, Mr. Smith,” he said.

“That’ll do,” growled Jabez. “Good night.” And he turned to pick up his bundles.

“Nay,” said the minister, quickly, “not yet. Let me help you. That is too heavy a load for one man, however light his heart may be.” And he stooped and picked up two of the sacks.

The other grumbled a little, but saw it was of no use to protest, and they toiled up the hill together. At last every one of the bundles had been left behind, and they turned homeward.

“Mr. Smith,” began the minister, softly, “I can’t tell you how my heart has been moved to-night.”

“Stop!” cried the other. “Stop! I won’t have it!”

“At least, let me ease you of this night toil,” persisted the minister. “You must not tax your strength like this, night after night. I can guess what joy it gives you, but you will kill yourself, or at best bring on serious illness.”

The other shook his head and walked on in silence.

“But I may help you as I have to-night,” the minister pleaded. “Let me do that. I should love to do it. I take no credit to myself, but I should love to do it.”

It was only after much persuasion that Jabez consented even to this. But consent he did, finally, and every night after that they went forth together on their errand of mercy, until at last miners and mine-owners reached a compromise and the strike ended. Since then, other cases of great need had been helped in the same way—only worthy cases, though, and in no instance had he helped the lazy or wilfully idle. A man who would not work, declared Jabez, sternly, deserved to starve.

When Miss Andrews that evening ran up the steps which led to the door of the Smith homestead, her lips still quivering from the story she had heard, she caught a glimpse of the owner. It was only a glimpse, for when he saw her coming he dived hastily indoors.

Life in New River valley, full of toil as it was, full of the stern, trying struggle for existence, had still its moments of relaxation, and in these, as she came to know the people better, the little schoolmistress was summoned to take a part—first in the church “socials,” which Mr. Bayliss organized from time to time in his unceasing efforts to bring the people within his doors and to get nearer to them; then at the informal little gatherings which took place at the homes of the wealthier families in the long winter evenings. Wealth is only a comparative term, and a man considered wealthy in the coal-fields may still be close to poverty; but most of them were honest and hospitable and open-hearted, and the lonely girl found many friends among them.

And they, when they saw her so thoroughly in earnest, regarded her with an admiration and respect which grew gradually to affection. To the men, roughened by labor in the mines and by year-long contact with the unlovely side of life, this delicate and gentle girl was singularly attractive, and their voices instinctively took a softer tone than usual when they spoke to her. To the women she was a revelation of neatness and refinement, and any suspicion or envy with which they may have regarded her at first was soon forgotten when they found her so eager to help them in every way she could, so free from guile and selfishness, so willing to give them of her best. Gradually, a keen observer might have noted, the hats of the women and girls of her acquaintance became less gaudy; gradually dresses of flaming greens and yellows disappeared; slowly certain rudiments of good taste began to be apparent. Of all the battles Bessie Andrews waged—and they numbered many more than may be set down in this short history—this one against the liking for garish things in dress was not the least heroic, requiring such patience, tact, and gentle resolution as few possess.

It was at a little party one evening at the home of George Lambert, superintendent of one of the larger mines, that her host swung suddenly around upon her with a proposition which for a moment took her breath away.

“You’ve been here nearly a year now, Miss Bessie,” he began, “and you’ve seen about everything the valley’s got to show. You’ve been on top of Old Nob—”

“Oh, yes; Mr. Bayliss and two of the boys took me up there last spring.”

“And you’ve been down to the falls?”

“Yes; we had a picnic there, you know.”

“But there’s one place you haven’t been.”

“And where is that, Mr. Lambert?”

“That’s back in our mine.”

For a moment she did not answer, and Mrs. Lambert laughed a little as she looked at her.

“That’s a great honor, Miss Bessie,” she said. “George is very particular about whom he asks to go through the mine. He thinks it’s the loveliest place on earth.”

Still she hesitated. It was one of the things she had longed yet feared to do. She had sometimes thought it was her duty to go, that she could not hope to wholly understand this people unless she saw them at their daily toil. But the black openings yawning here and there in the mountain-side frightened her; they called into life weird imaginings; it seemed so terrible to walk back into them, away from the air and the sunlight.

“Why,” laughed Lambert, reading her thoughts in her face, “to look at you one would think you could never hope to get out alive! There hasn’t been an accident—a really bad accident—in our mine for over eight years. It’s perfectly safe or I wouldn’t ask you to go. A coal-mine is a mighty interesting thing to see, Miss Bessie.”

There was something so encouraging in his eyes and voice, so reassuring in his confidence, that her fears slipped from her.

“Of course it is interesting,” she said, “and thank you for the invitation, sir. I shall be very glad to go.”

“And how about you, Mr. Bayliss?” asked Lambert.

“Why, yes; I should like to go, too. I’ve been through the mine three or four times, but it has a great fascination for me.”

“That’s good. Suppose we say Saturday morning. Will that suit you, Miss Bessie?”

“It will suit me very well, sir,” answered the girl, a little faintly, remembering that Saturday was only two days away.

“All right; Mr. Bayliss and I will stop for you. And say—there’s one thing; you want to wear the oldest dress you’ve got—a short skirt, you know.”

“Very well,” she smiled. “I think I have a gown that will answer.”

Whatever misgivings she may have experienced in the meantime, they were not apparent on her face when she came out to meet the two men bright and early that Saturday morning.

“That’s the stuff!” said Lambert, looking approvingly at her natty costume of waterproof. “That’s just the thing.”

“Yes; I think this will defy even a coalmine,” she answered, laughing. “It has withstood a good many mountain storms, I know.”

“Well, if you’re ready we are,” said Lambert, and set off along the railroad track that led to the big tipple.

“And you’re going to tell me everything about it?” she asked.

“Of course; that’s what I’m for. Mr. Bayliss maybe’ll help me a little if I get hoarse,” he added slyly.

“Not I!” cried that gentleman. “In the science of coal-mining I am still in the infant class. I’ll let you do the talking, Mr. Lambert, and will be very glad to listen myself.”

Lambert strode on, chuckling to himself. He was certainly qualified, if any one was, to tell her “everything.” He had made the mine a study and life-work, and regarded it with pride and affection. Every foot of its many passages was as familiar to him as those of his own home. The men knew that with him in charge the mine was as safe as skill and care could make it; in hours of trouble, which were certain to come at times, his clear eyes and cheery voice, his quick wit and indomitable will, were mighty rocks of refuge to cling to and lean against until the storm was past. As he walked along beside them this bright morning, alert, head erect, his two companions glanced admiringly at him more than once, knowing him for a man who did things worth doing.

“Well,” he said at last, as they reached the great wooden structure stretching above the track, “here we are at the tipple, and we might as well begin here, though it’s sort of beginning at the wrong end. Let’s go up to the top first, though,” and he led the way up a steep little stair. “Now, Miss Bessie, we have come to the first lesson in the book. The coal is let down from the mine on that inclined railway to this big building, which is built out over the railroad track so the coal can be dumped right into the cars without any extra handling. The coal, as it comes down, is in all sizes, called ‘run of mine’—big lumps and little, and a lot of dirt. So it is dumped out here on this screen,—the bars are an inch and a half apart, you see,—and all the coal that passes over it to that bin yonder is called ‘lump.’ The coal that goes through falls on that other screen down there, with bars three quarters of an inch apart, and all that passes over it is called ‘nut.’ All that falls through is called ‘slack,’ and is hauled away to those big piles you see all around here. Understand all that?”

“Oh, yes; that’s as clear as it can be.”

“That’s good. Now we’ll go up to the mine. Let’s get into this empty car. It’s not as clean as a Pullman, nor as big, but it’s the only kind we run on this road.”

They helped her in, and one sat on either side to steady her, as the tipple-hands coupled it to the cable and the trip up the steep grade began.

“You see, the loaded cars going down pull up the empty ones,” he said. “We make gravitation do all the work. It’s a simple way, and mighty convenient.”

The loaded car, heaped high with coal, passed them midway, and in a moment they were at the mouth of the mine. To her surprise, she saw that there were two openings, one much smaller than the other.