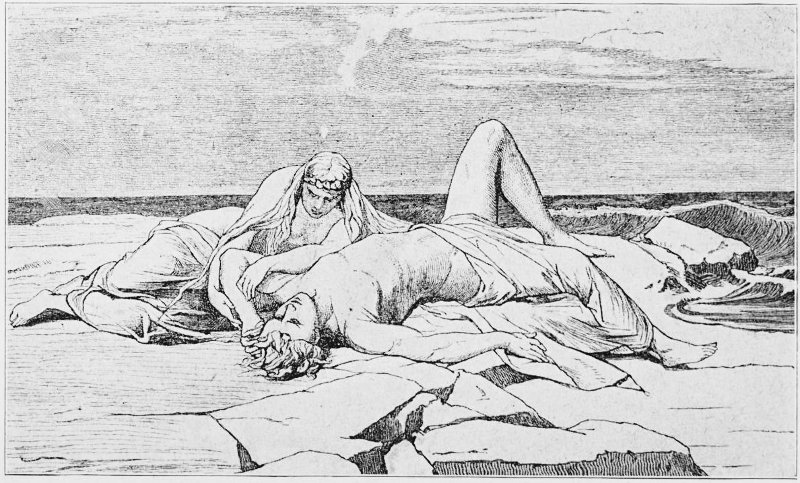

DEATH OF HECTOR

Life Stories for Young People

Translated, and abridged from the German of

Carl Friedrich Becker

BY

GEORGE P. UPTON

Translator of “Memories,” “Immensee,” etc.

WITH THREE ILLUSTRATIONS

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1912

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1912

Published September, 1912

THE·PLIMPTON·PRESS

[W·D·O]

NORWOOD·MASS·U·S·A

In tracing the career of Achilles in connection with the Trojan war, that inimitable classic story-teller, Carl Friedrich Becker, follows the lines of Homer’s Iliad. He gives the reader a graphic picture of the stirring events in the ten years’ siege maintained by the Greeks, under the leadership of Agamemnon, king of Mycenæ, in their finally successful effort to redress the injury done to Menelaus, king of Sparta, whose wife, Helen, was carried off by Paris. The striking points in this thrilling narrative are the quarrel between Agamemnon and Achilles; the exploits of Hector, noblest character of them all; the human impersonations of the gods, who take part in the strife—some on one side, some on the other; the death of Patroclus; the final reconciliation of Achilles and Agamemnon and the former’s tremendous exploits; the death of Hector, and the touching interview with the aged Priam, who seeks to recover his body.

The ultimate fate of Achilles and the fall of the city are not told, nor the wretched end of Agamemnon, who, according to Æschylus, was killed by Clytemnestra, the queen, upon his return. Hector is one of the most conspicuous figures in this great drama and appears only second to Achilles among all the warriors. The exciting Trojan war story has never been told more graphically or interestingly in modern prose than in Becker’s version. In adapting it to the series of “Life Stories” the translator has been obliged to abridge the original work somewhat, but the parts omitted do not interfere with the flow of the story.

G. P. U.

Chicago, May, 1912.

Troy was a small portion of that section of Asia Minor which was later called Phrygia. Its northern coast touched the entrance to the Hellespont. It was very densely populated and had, besides many little plantations, villages, and settlements of farmers or herdsmen, a large city with a strong wall, towers, and gates. Homer never called the city Troy, but always Ilios or Ilium. The surroundings he calls Troy and the inhabitants Trojans, after an ancestor named Tros, who was said to have founded the city. He describes them as a bold, enterprising people, who lived in a high degree of comfort and practised many arts of which the Europeans of that time were ignorant.

The Achaians, as Homer calls the inhabitants of Greece, and the Trojans, engaged in mutual depredations upon each other’s property,—until at last the long-standing national hatred broke out violently through the fault of the Trojans. Alexandros, or Paris, one of the sons of the old Trojan king, Priam, sailed across to Europe and paid a visit to King Menelaus, ruler over several cities in Sparta. He was hospitably received and entertained for many days, but repaid his good host with most shameless ingratitude. He persuaded the queen, the beautiful Helen, to forget her duty and flee with him. Menelaus sought revenge and called upon his brother Agamemnon, ruler over Mycenæ, old Nestor of Pylos, Ulysses of Ithaca, and many other valiant princes to ally themselves with him. A number of young lords who had long been wishing to take part in some glorious enterprise, like the expedition of the Argonauts, of which their fathers had so much to tell, offered their services with innumerable followers.

News of the mighty campaign which was being arranged spread throughout Greece, causing great rejoicing. Everyone looked upon it as a great opportunity and an event in which it would be shameful not to take part. A whole year passed in preparing the equipments. In the meanwhile Nestor and Ulysses travelled about everywhere to persuade the princes of Greece and its neighboring islands, who had hesitated hitherto, not to miss their share in the honors and spoils which so brilliant a campaign was sure to afford. For the object was nothing less than the destruction of the celebrated city of Troy, and the booty which was to be expected from such a rich people was incalculable. They had excellent success on this recruiting expedition, calling upon Peleus, father of Achilles in Thessalia, King Idomeneus in Crete, old Telamon in Salamis, and others.

The harbor of Aulis in Bœotia was selected for the place of meeting and at the appointed time more than one thousand ships assembled, with men from all parts of Greece. They agreed to offer the command to Agamemnon, one of the foremost among the princes, partly because he had brought the largest following and partly because he and his brother had organized the campaign. He was, besides, a clever and honorable man and a brave warrior, although considerably inferior in physical strength to Achilles, the invincible.

All was ready for departure, but the ships waited in vain for a favorable wind. It was supposed that some god was delaying the voyage and that he must be propitiated by an offering, so the priest Calchas was commanded to consult the oracle. After observing the usual signs he announced that Agamemnon had slain a sacred animal in the chase, thereby offending Artemis, who now demanded a human sacrifice in the shape of Agamemnon’s eldest daughter, Iphigenia. She was accordingly brought to the altar, but Artemis relented at the moment when the fatal stroke was about to be given, removed the trembling maiden in a dense cloud, and put an animal in her place. When Iphigenia awoke from her swoon, she found herself in the temple of Artemis in Taurus, where she served for a long time as priestess.

The same day, after this sacrifice, a favorable wind swelled the sails and the impatient heroes boarded their ships. In a few days the fleet arrived at Troy. On the way they had stopped to plunder a few cities on the islands of Scyros and Lesbos, had killed the men, and taken the women on board as slaves. After landing they proceeded in the same manner in the country about Troy. At the end of the war the godlike Achilles boasted that he alone with his Myrmidons had conquered twelve rich cities by sea and eleven by land in the Trojan territory. The booty which each skirmishing party brought in to camp was divided and the chief always received the best of everything. The inhabitants of the capital were safe behind their walls, and as the Greek forces were seldom united, the Trojans were often able, by a sudden sortie, to repulse the attacking parties which ventured too near the gates. This desultory warfare continued for several years, until many of the Achaians began to long for home. But they were ashamed to depart thus, without having accomplished their object. The leaders concentrated their men and began the siege in earnest.

The Trojans now took measures for more careful defence and sent to the neighboring peoples to demand their aid. Many princes responded to the call with their followers, until they had formed an alliance equal in strength to the Achaians. In the tenth year of the siege fortune seemed to have turned her back on the Greeks, for besides the hardships of war, they had to contend with a pestilence, and finally were nearly destroyed by the Trojans, while their two mightiest chiefs, Agamemnon and Achilles, were quarrelling.

Agamemnon had plundered a city and had taken Chryseïs, daughter of a priest of Apollo, for his slave. In the same way Achilles had become possessed of a maid named Briseïs, to whom he became so attached that he wished to keep her always with him. After a time the priest appeared in the Greek camp with rich presents to ransom his daughter, but Agamemnon did not wish to give up the maiden and returned a harsh answer. The Greeks urged him to release the maid out of respect for the priest and for fear of Apollo’s wrath, but the obstinate man refused to listen to reason and bade the father depart on pain of chastisement. With loud lamentations the old man retired to the seacoast and prayed to Apollo. The legend tells us that Apollo at once left Olympus, seated himself at some distance from the ships, and began to shoot his arrows into the Greek camp. Whatever was struck died a sudden death by the plague. First the donkeys and dogs and then the men fell victims. The pestilence raged for nine days, during which the funeral pyres burned incessantly.

This filled the leaders with great apprehension, so that on the tenth day Achilles summoned a folk assembly and advised the people to call upon the seer Calchas to discover what fault of the army had brought this woe upon them and by means of what sacrifice the god might be appeased. Calchas hesitated, but at length answered that he knew the reason, but feared to give it until the bravest among the heroes had sworn to protect him in case a man of great power among the Achaians should be angry at his decree. Then Achilles stood up and made a public vow to protect him, even though the man he meant were Agamemnon, mightiest of the Greeks. “Very well, then,” replied Calchas, “I will declare the truth. Yes, it is Agamemnon with whom Apollo is angry, for he has dishonored his priest and has refused to restore his daughter to him. Therefore hath he sent this punishment upon us and we cannot escape it until the maiden shall be returned freely to her father and a rich sacrifice has been offered to the god upon his holy altar.”

Agamemnon, trembling with rage, cried: “Miserable seer, must I do penance for the people’s sins? The maiden is wise and well trained in feminine tasks. I prize her above my spouse, Clytemnestra, and must I give her up? Let it be so; take her! I will bear even more than this for the people’s good. But I tell you, ye must provide another gift in her place, for she was my share of the booty.”

“Avaricious, insatiable man,” answered Achilles, “what dost thou demand? I knew not that we had treasures in reserve. Therefore be patient until the gods aid us to conquer rich Troy. Then thou mayst replace thy treasure many times over.”

Although this speech was just, the angry man imagined that it was intended in mockery and he cried: “Not so, Achilles; strong and brave as thou art, thou shalt not intimidate me! Dost thou expect to keep thy spoils and the others theirs, while mine is taken from me? I tell thee, if I receive no compensation, I will myself take it from thy tent or those of Ulysses or of Ajax, or wherever I please, and let him whom I despoil avenge himself. Take now the maiden, put her aboard the ship, together with the sacrificial steer, and row her to Chryse, where her father lives, that the god may no longer be angry with us.”

This speech infuriated Achilles and he cried angrily: “What! Thou wouldst take away my prize? Did we march against the Trojans for our own sakes? Not I, indeed! They never injured me, nor ever robbed me of a horse or cow, nor pillaged my newly sown fields. I was well protected by wooded hills and the broad sea and never thought of Troy in my Phthian home. It was solely on thy account, thou selfish, shameless man, that I came hither to avenge thine and thy brother’s sullied honor. And this hast thou so speedily forgotten and threatenest even to take away the spoils which the Achaians have unanimously accorded me and which I have honestly earned? Have I not hitherto borne the chief burden of the war? Who has fought as much as I? Let him appear! And when have I received prizes like thine? Thou hast always taken the best of everything, while I have contented myself with little. Very well! Thou mayest fight alone! I return to Phthia!”

“Fly, if thy heart bids thee!” flashed forth Agamemnon in anger. “Truly I shall not beg thee to remain. There are other warriors here through whom Jupiter will help me to achieve honor. Thou hast been obnoxious to me from the beginning. Thou hast ever loved quarrelling and strife and hast never kept peace. Thy strength hath been given thee by the gods and thou dost pride thyself altogether too much upon it. Thou mayest sail away with all thy followers and rule peacefully over thy Myrmidons. Thy wrath is nothing to me. But I tell thee, that as Phœbus Apollo has taken Chryse’s daughter from me, I shall take from thee the rosy daughter of Briseïs, thy prize, so that thou mayest learn how much more powerful I am than thou, and that no other in future shall dare to defy me as thou hast done.”

In a rage Achilles drew his shining sword from its scabbard to cut down Agamemnon. Suddenly, unseen by all the rest, the goddess Athena stood behind him and whispered to him not to draw his sword against the king, but that he might scold as much as he pleased. “Thy word I must obey, oh goddess,” answered Achilles, “though anger fills my heart. The gods attend those who follow their counsel.” With these words he returned his sword to its scabbard, but turning to Agamemnon he cried: “Thou miserable drunkard, with the look of a dog and the courage of a hare! Never hast thou dared to risk a decisive battle or to lie in ambush with the other nobles; but it is more comfortable to take away his prize from the single man who opposes thee. I swear that thou shalt never again see me raise my arm against the Trojans, though all thy Achaians should perish and thou shouldst beseech me on thy knees to save thee.”

Thus he spake, and dashing his sceptre upon the ground, sat down in silence. Agamemnon was preparing to answer this passionate speech when up rose old Nestor, reverenced like a father by everyone for his age, wisdom, and experience. When it was seen that he wished to speak all were quiet. Even Agamemnon bridled his anger, and the well-meaning old man began: “Dear friends, what are you about! What an unhappy fate do ye bring upon us all! How Priam, his sons, and the whole Trojan people will rejoice when they hear that the foremost Achaians are quarrelling. Listen to me, for ye are all much younger than I. However much power the Achaians have given thee, Agamemnon, do not abuse it. Let Achilles keep the prize with which the Achaians have rewarded him. And thou, Achilles, do not defy the king, for never has Jupiter crowned a king with such honor as this one. Though thou art stronger than he and boastest thyself of divine ancestry, he is the more powerful and all the people obey him.”

“Truly, honorable father,” answered Agamemnon, “thou hast spoken worthily. But this man is unreasonable; he wishes to be above all others, to rule all, to make laws for all.”

Achilles interrupted him. “Indeed I should be a coward did I submit to all thy insults. I will keep the vow I have sworn. One thing I will say—if the Achaians wish the maiden they have given me, they may have her. But woe to thee if thou layest hands upon my other spoils.”

Agamemnon insisted on taking the maiden, and he had the power to carry out his threats. Wisdom counselled Achilles to surrender what he was not strong enough to hold. He withdrew from the quarrel with more dignity than his unjust enemy, and his threat of abandoning the war gave him ample satisfaction. The result proved his value. He had thus far been the only one able to vanquish Hector, Priam’s most valiant son; and now that he had withdrawn, it was the Trojans, day after day, who were the victors. It seemed as though a god had doomed the Greeks to destruction.

Agamemnon first sent Ulysses to conduct his slave and the appointed animals for the sacrifice to her father’s home. Next he called upon two heralds to fetch the beautiful Briseïs from Achilles’ tent. They obeyed his command in fear and trembling. But Achilles banished their fears, saying: “Come hither, ye sacred messengers and peace be with ye. For ye are not to blame, but he who sends ye. He shall have the maid. Go, Patroclus, and fetch her out. Ye are all witnesses before gods and men that I have sworn never to lift a hand again for Agamemnon against Troy.”

They received the maid from the hands of his friend, Patroclus, and she went reluctantly away with them, often glancing sorrowfully backward toward the tent of her former beloved master.

Achilles gazed gloomily after the men, then arose quickly and seated himself far from his companions on the beach, looking moodily out over the dark waters. He bethought him of his mother, Thetis, who lived in the blue depths of the sea, spread out his arms, and prayed to her for aid. She heard him and hastened to appear. Floating over the sea like a cloud, she seated herself beside her weeping son and tenderly caressed him. “Dear son, why dost thou weep?” she asked. “What troubles thee? Speak! Conceal nothing from me.” With deep sighs he related what had happened to him, begging his mother to avenge his wrongs and to intercede for him with Jupiter.

It was early on the twelfth day since Achilles had retired from the fray when Thetis rose from the dark waves and ascended the heights of Olympus. She found the mighty Jupiter seated on the summit of the mountain, apart from the other gods, bowed herself before him, embraced his knees with her left hand, and caressed his chin with her right hand. “Father Jupiter,” she said coaxingly, “if thou lovest me, grant me a boon and show favor to my son, who has but a short life to live. Give him redress against Agamemnon and let the Trojans prevail, until the Achaians shall be obliged to recompense him with redoubled honors, for this base insult.”

The father of the gods and men began dejectedly: “Thou wilt involve me in strife and enmity with Juno. Even now she quarrels with me and says I am aiding the Trojans. Leave me quickly, that she may not see thee, and I will grant thy request with a nod.”

The goddess descended from the shining heights of Olympus into the depths of the sea, while Jupiter arose and went to his palace. When the gods saw him coming they all left their places and went respectfully to meet him. He approached the throne and seated himself. But his jealous consort had noticed Thetis and began straightway to pick a quarrel with him. “Yes, I saw the silver-footed Thetis at thy knee, saw thy nod, and saw her depart content. Doubtless thou art about to honor Achilles once more, castigate the Achaians, and protect the insolent Trojans.”

“Thou art continually spying upon me,” answered the ruler. “But it shall do thee no good—I do as I please. Therefore sit still and be silent, for shouldst thou arouse my anger, all the immortals together could not save thee from my powerful hands.”

Thus spake the Thunderer, and Juno was frightened. All the gods were sorry for her, especially Hephæstus, the artist god of fire; for she was his mother, and he had already learned that Jove’s threats often received terrible fulfilment. He began in his mother’s behalf: “It is intolerable that thou shouldst quarrel over mortals. I admonish thee, mother, to bear thyself acceptably, that our father may be content and our feast be undisturbed.” He took his goblet, and handing it to his mother, said: “Be patient, dear mother, even though grieved at heart, that I may not have to look upon thy punishment. Once before when he struck thee and I attempted to restrain him, he took me by the heel and cast me down into the air, so that I fell for a whole day before I struck the earth, and I have limped ever since.”

The mother smiled and took the cup, and Hephæstus filled the goblets of the other gods. Then Apollo with his muses broke forth in sweet song, and thus the day passed among the immortals in blissful contentment. When Helios had put out his flaming torch, each went to his dwelling to rest. Jove was the only one whom sleep fled. He meditated anxiously how he might favor Achilles by defeating the Greeks. He sent a deceptive dream to Agamemnon, telling him to prepare for battle and that it would be easy for him to conquer the city. As soon as he awoke, Agamemnon told the other princes of his dream. The assembly was called together. Agamemnon was uncertain whether he dared call upon the discontented army, and wishing first to feel his way, he began to talk of their return. “Here we have lain for ten years,” he said. “The ships are rotting, the anchor ropes are mouldering, and we have as yet accomplished nothing. Indeed the gods seem to be against us. Therefore my advice is that we quickly put to sea and sail for home before the Trojans do us a greater mischief. You all must see that we cannot take the city.”

He had scarcely ended when the whole company rushed exultantly away to the ships, for all were anxious to return to their homes. This was more than the king had expected and he looked on in despair, while the other brave leaders gnashed their teeth. They were powerless to stay the tumultuous rabble until Ulysses, hurrying forward with quick presence of mind, admonished leaders and men to return to the assembly. “Do not be in such a hurry,” he would say when he met one of the princes; “hear the end. Thou dost not know the king’s mind yet. He but wished to test us, and woe to thee if the mighty king’s wrath overtake thee.” Then he drove the people back, and they came with a roar like angry waves breaking on a rocky shore. They knew Ulysses’ warlike spirit and feared he might advise renewal of the struggle. Only respect for his great authority moved them to return.

When all the princes were seated and order had once more been restored, Ulysses was about to take up the sceptre. Suddenly Thersites pushed forward. He was despised by the whole army as a quarrelsome, insolent fellow, who seldom let an opportunity go by to insult the princes, not excepting Agamemnon himself, with mocking, rebellious words. He was the ugliest of all the Greeks, having a lame foot, a deformed shoulder, a pointed, bald head, and a cast in one eye.

“What wilt thou now, Atreus’ son?” he shrieked at Agamemnon. “I should have thought thou hadst collected enough money and valuable spoils to have satisfied thy avarice. Dost thou desire still more? Must the Achaians still sacrifice themselves to fill thy insatiable throat? Are ye not ashamed, ye princes, to suffer such a king to lead ye to destruction? But ye are women or ye would desert him and embark without him.”

“Silence, foolish babbler!” cried Ulysses. “If I ever again hear thee slander one of us so shamelessly, true as I live, I will tear thy clothes from thy body and whip thee out of the assembly so that the whole camp shall hear thy cries!” Thus spake the hero, beating him about the back and shoulders with the sceptre, so that he cowered down and then ran away crying out.

The heralds now commanded silence as Ulysses again stood up to speak. Turning to Agamemnon he said: “Oh son of Atreus, how badly have the Achaians kept faith with thee. They promised not to return home until we had conquered Troy, and now they act like children. I do not blame anyone for longing for his home after ten years of absence. But just because we have waited so long, it were a shame to return when we are so near the goal. For we must succeed or all the signs of the immortal Jove are a mockery. Did not Calchas tell us, back in Aulis, how it would be? Do ye not remember the sparrow’s nest in the beautiful maple tree near our altar? I can still see the spotted serpent gliding up its trunk and swallowing the eight young birds and catching the frightened mother bird at last by the wing. We were all alarmed at the omen, but Calchas interpreted the occurrence favorably. He said: ‘The war shall consume nine years, but in the tenth, Troy shall fall.’ Behold, friends, the prophecy is about to be fulfilled, and will ye now flee? Wait but a short time until we have taken the proud city of Priam, and then let us depart laden with rich booty and crowned with immortal glory.”

Old Nestor next arose to persuade those who still hesitated. “That is right,” he said. “Let reason speak to you. Shall our great plans go up in smoke and shall our sacred vows to Menelaus and his good brother, Agamemnon, be broken? Indeed no! Lead the Achaians into battle, great king, and most of them will, I hope, cheerfully follow thee. Let the men be gathered together by tribes, that each may fight for his own blood. Then thou shalt clearly see whether the gods protect the city or whether it is the cowardice and ignorance of our army which defeats us.”

“Well spoken!” cried Agamemnon. “We must not rest until the fortress is taken. Jove will surely aid us. His flashing lightnings as we left Aulis are the surest pledge of this. The city would already be ours had I ten men in my army as wise as thou art, O Nestor, and alas! had Achilles not left us—Achilles, whom I have wounded so sorely. But come! Let everyone prepare for the battle. Let us quickly refresh and strengthen ourselves and then advance upon the city in a body.”

With these words he dismissed the assembly and the people streamed back to the tents to arm themselves and take some food. The king invited all the chiefs to join him at breakfast in his tent. Nestor, Idomeneus, the two brave Ajaxes, Diomedes, and Ulysses were there, besides his brother Menelaus. They took a steer, strewing sacred barley upon it, and while they all stood about it in a circle, Agamemnon lifted up his voice and prayed to Jupiter for victory. Alas! he did not know that the god had turned against him.

The drivers harnessed their horses, the warriors donned helmet and shield and took up their lances, and the heralds lifted up their mighty voices above the din, to call the stragglers together. Company after company, they assembled like a swarm of migrating birds. Then the princes hastily mustered the ranks and arranged the races and tribes as Nestor had advised. But the king called to them in a loud voice to fight bravely, and when all was in readiness they swept forwards with a din and outcry, like a flock of screeching cranes.

The Trojan nobles were holding a council of war before the palace when Iris, a messenger from Jupiter, appearing in the shape of Priam’s son Polites, joined them. He came from one of the watch towers and brought the news that an incalculable number of Achaians was approaching. Hastily the council broke up, each chief going to assemble his people, that they might be ready to meet the Greeks before they should reach the city wall. In their midst were many heroes, but distinguished amongst them all for invincible strength and heroic courage were Hector, son of Priam, several of his brothers, and also Æneas, a connection of the royal house.

Masses of men now poured out of the open city gates and ranged themselves in long lines of battle. The Achaians advanced ever nearer, but could not be distinguished for the tremendous dust which arose before them, enveloping them like a cloud. When they came to a standstill the leaders at last recognized one another. In front of the Trojans marched the godlike Paris, wearing a leopard skin, his bow slung over his shoulder, his sword on his thigh, and swinging two javelins in his right hand. With mocking words he challenged the bravest Achaians to combat. His arch-enemy, Menelaus, was the first to hear him and his heart swelled with anger, while he burned to meet the robber of his honor. He guided his chariot toward him, sprang hastily down, and ran to meet him, eager as a lion to spring upon its prey. The handsome youth was frightened at his appearance and fled, vanishing among the throng of Trojans.

His brother Hector saw his flight and was indignant at the sight. “Coward,” he cried, “would that thou hadst never been born or else hadst died ere ever thou didst learn to seduce women! Now thou hast made a laughing-stock of thyself before both armies. I can only wonder how thou hadst ever the courage to go to a foreign land and there to steal away a beautiful woman. The deed has been the undoing of us all and brought eternal shame upon thyself. Menelaus appears quite different to thee to-day, I suppose, from what he did then? Had he caught thee, thy lute and curled hair, thy slender shape, and the favor of Aphrodite had availed thee little. Were the Trojans not a cowardly rabble thou wouldst long ago have paid the penalty for all thou hast brought upon them.”

Paris answered: “Thou art right, brother. But forgive me. Wouldst thou see me fight, bid the others cease and let me challenge Menelaus to single combat before the people. Then let whichever is the victor take Helen, with all the other treasures, that the Trojans and Achaians may part in peace.”

These words pleased Hector and he advanced, holding out his lance before the Greeks and calling upon them to cease fighting. The arrows of the enemy fell about him like rain until Agamemnon spied him and cried loudly: “Stop, men! Do not shoot, for he wishes to speak to us.”

Hector called out: “Hear me now, Achaians and Trojans! Paris, my brother, the cause of all this trouble, would also make an end of it and challenges Menelaus to single combat. Whichever wins shall take both Helen and the treasure and the death of the vanquished shall end the war. Ye shall all return to your homes and we will swear a bond of friendship.”

Menelaus listened, well pleased, and stepped forth to accept the challenge, only stipulating that a solemn pledge should be taken with all the customary sacrifices and observances and that King Priam should himself be present at the combat. All this was willingly granted.

In the meanwhile Agamemnon and Hector sent for the lambs and goats for the sacrifice. Priam was seated upon the city wall near the Scæan gate with the elders who were no longer able to go into battle, and there the message was brought him by a herald. Helen also received the message, which she heard with pleasure, hoping in her heart that Menelaus might be the victor; for she had begun to long for her former husband, her native city, and old friends. She hastily wrapped herself in a silvery veil of linen and hurried away to the Scæan gate, accompanied by two female attendants. The aged men at the tower were entranced with her beauty and compared her to one of the immortal goddesses. Priam welcomed her kindly, saying: “Approach, my daughter. Sit here beside me, that thou mayest see all thy dear relatives and thy former husband. Do not weep. It is not thy fault. It is the immortal gods who have sent us this unhappy war. But tell me, who is that stately man who stands out amongst all the others, so noble and commanding in appearance?”

“How kind thou art, gracious father, and how unhappy am I!” answered Helen. “Would I had died ere I followed thy son hither. That stately hero of whom thou speakest is Agamemnon, the powerful king of Mycenæ. He was my brother-in-law. Alas! would that he were now.”

“So that is Agamemnon!” replied Priam slowly, observing him with admiration. “But tell me more. I see one who is not so tall, but with broad chest and mighty shoulders. He has laid his weapons upon the ground and goes among the soldiers, from one company to another, even as a ram musters the flock.”

“That is Ulysses, Laërtes’ son,” said Helen; “a good soldier and the wisest of them all in council.”

“That is true, and now I recognize him myself,” said Antenor. “He came with Menelaus into the city, as ambassador from the Achaians, to make terms for thee.”

“But look!” cried Priam. “There go two others, who appear to be powerful kings.”

“Truly they are valiant heroes,” answered Helen. “The first is Ajax of Salamis and the other Idomeneus, king of Crete. He often visited us and Menelaus entertained him gladly, for he is an excellent man.”

While this conversation was going on, there came a herald to the aged king to announce that the chariot was waiting to take him to the battlefield. On their arrival in the midst of the two armies, Agamemnon advanced to meet the king, surrounded by the other princes. Heralds went among the company, sprinkling the hands of each with water; for none might perform a sacred rite with unclean hands. Then Agamemnon drew a great knife from his belt and sheared the wool from the lambs’ heads and the heralds gave a piece of it to each prince. Then Agamemnon lifted up his hands and prayed: “Father Jupiter, glorious ruler, and thou, Helios, all-seeing sungod; ye Streams and Earth and ye Shades who punish those who swear falsely, be ye witnesses of our vows and of this solemn treaty. If Paris vanquish King Menelaus, he shall keep Helen and her treasures and we will return to our country. But if he fall in the fight, the Trojans shall give up the woman, together with all the treasure, and pay us besides a fair tribute in this and future years. And should they ever refuse to fulfil this vow, I shall renew the war and never stop until I have received full satisfaction.” All took the oath and the king cut the throats of the lambs and laid them down upon the ground. Then each took wine and poured the first drops upon the earth in honor of the gods, saying: “May Jupiter thus spill the blood of him who shall first break the sacred oath.”

“Worthy men,” said old Priam, with tears in his eyes, “grant me leave to return home that I may not look upon the combat. Let Jupiter decide. He knoweth best the right.” With these words he was lifted into his chariot and Antenor drove him swiftly to the palace.

Hector and Ulysses, the arbiters of the combat, now measured off the ground and put the lots in a helmet, one for Menelaus and one for Paris, in order to decide who should first cast his spear. Hector shook the helmet until one of the lots flew out. It was that of Paris. The bystanders at once retired to a distance and seated themselves in a circle. Paris, in shining armor and carrying a heavy javelin, advanced from one side and Menelaus from the other into the middle of the arena. They shook their weapons fiercely and Paris was the first to cast his javelin. But he struck only the edge of Menelaus’ shield; the point was bent and the spear fell harmless to the ground.

Menelaus cast his spear with such force that it pierced the shield and would have penetrated his heart had Paris not quickly sprung aside. But while he was gazing in dismay at the wreck of his shield, Menelaus sprang upon him with drawn sword and had cloven his head in twain had not the thick helmet shivered the brittle blade. For the third time he sprang at Paris and seized him by the helmet to throw him to the ground, but at the same moment the chin strap broke and Menelaus’ arm flew up and he found himself holding the empty helmet in his hand. Paris took the opportunity to rush away and take refuge among the Trojans, and when Menelaus turned to cast his spear a second time at him, he had already disappeared. It was the friendly goddess Aphrodite who had saved him.

While the Greeks were loudly acclaiming the victor, Jupiter put it into the heart of a Trojan to shoot an arrow at Menelaus. Pandarus was the man’s name and Athena herself had put the arrow into his hands just as Menelaus passed under the city wall. But the wound was not dangerous and was quickly dressed by Machaon with a salve which he always carried about him. The victorious cries of the Achaians now changed to cries of rage. All condemned the treacherous act and called down the vengeance of Jupiter upon the Trojan people.

RESCUE OF PARIS BY APHRODITE

Agamemnon assembled his cohorts once more and hastened among the ranks encouraging, threatening. Brave Idomeneus he found ready armed amongst his Cretans. Next he mustered the tribes under command of the two Ajaxes, which were ready to go into battle. The next company that he met were the Pylians, under the command of young princes whom old Nestor directed. The old man was even now going about among the men, restraining the horsemen and placing the weaker in the middle, with the more courageous and experienced at the front and on the sides, and giving much valuable advice to the young leaders. Well pleased, Agamemnon hurried on to the Athenians and Cephallenians, led by Menestheus and Ulysses. He found the two chieftains conversing unconcernedly together and called to them: “Is this the interest ye take in the war? All the rest are armed and ready and would ye be left behind? Ye are always foremost at the banquet and now ye look on while ten companies of Achaians enter the battlefield before ye.”

Ulysses answered, darkly frowning: “What words are these, oh ruler? When hast thou ever found us tardy in battle? When the fight begins we shall not be far away, and thou shalt see the father of Telemachus at the front amongst the Trojan horsemen. Those were empty words thou spakest!” Smiling at his anger Agamemnon answered: “Noble son of Laërtes, thou needest no advice nor blame from me, for we are of one mind. Let it be forgotten if I have spoken harshly.”

He hastened to the next company, where he found Diomedes and Sthenelus standing together in their chariot, the former with sad and disheartened mien. “What, son of Tydeus!” he said to him, “thou seemest disturbed and art trembling. Thy noble father knew no fear. What deeds that man accomplished! His son is less heroic in battle, though more ready of tongue.”

“Speak not falsely, Atride,” answered Sthenelus, as Diomedes bowed respectfully under the king’s reproaches. “We boast ourselves braver than our fathers, for they led many foot-soldiers and horsemen to Thebes and failed to take the city, while we stormed it with but few followers. Do not praise our fathers at our expense.”

“Silence, friend,” interrupted Diomedes. “I do not blame Agamemnon for inciting the Achaians to battle. The fame and gain will be his if the war is ended gloriously, and his the disgrace and ruin should the Achaians be put to flight.”

With these words he sprang from the chariot, so that his bronze harness rattled, and began to arm himself for the fight. Agamemnon passed on. While he was mustering the right wing, the left advanced to the attack. They moved slowly and silently forward, enveloped in a cloud of dust. At last Achaians and Trojans met; shield rang against shield, lance broke lance. Now loud shouts arose, and mingled with the battle cries were heard the groans of the wounded and dying being dragged away by their friends, that they might not be trampled upon or subjected to the cruelties of the enemy. Above the din of battle rose the commands of the chieftains and the cries of the soldiers. Swords hissed through the air, spears whistled, shields rang against one another.

Hector, seeing his companions give way, called to them: “Forward, Trojan horsemen! Come, do not leave the field to the Argives. They are made neither of iron nor stone that our spears should rebound from them, and Achilles, the great hero, no longer fights in their ranks.”

The Trojans took courage at this and renewed the battle. Diores, the Greek, was stretched senseless upon the ground by a heavy stone, and just as his conqueror, the Trojan Peirus, had given him the deathblow with his spear and was about to strip his victim, Thoas the Ætolian rushed upon him with his sword and he fell across the body of Diores. But Thoas was obliged to flee in turn, for the Trojans ran up to carry off Peirus, and he had to seek other booty. It had been a hot day and horse and rider were panting.

The sun stood high in the heavens and the battle continued to rage with the greatest bitterness. Hector and Æneas, Agamemnon, Ulysses, and the other great heroes raged about the broad battlefield like beasts of prey. Diomedes was especially favored by Athena on this great day and laid many warriors in the dust. Among the Trojans, two sons of the rich and pious priest of Vulcan, Dares, spurred forward from the swarm of warriors against him. One of them cast his spear at the hero, but missed the mark, which but served to enrage the warrior. He grimly cast back at the youth and pierced him through the heart. His brother turned and fled and Diomedes quickly seized the handsome steeds and commanded his men to conduct them to the ships.

One could not tell to which side Diomedes belonged, for he was always in the midst of the fight. He was at last espied by Pandarus, the same who had broken the oath by shooting at Menelaus. He approached Diomedes stealthily from behind and shot a sharp arrow into his right shoulder, so that blood stained his coat of mail. “Come, ye Trojans,” he cried, “I have wounded the most formidable of the Achaians.” But the arrow had not penetrated so deeply as he thought. Diomedes sought his charioteer Sthenelus. “Friend,” he said, “come quickly and pluck this arrow from my shoulder.” As it was withdrawn, blood spurted from the wound and the warrior prayed to Athena: “Hear me, goddess, and as thou hast ever been my protector in battle, oh aid me now and let me slay the man who hath wounded me and boasts that I shall not much longer see the light of day.”

The goddess heard him and stanched the blood. “Thou canst return to the fight,” she said. “I have endowed thee with the strength and courage of thy father and will distinguish thee to-day above all other Achaians. Only take care not to oppose the immortal gods in battle, but attack all others courageously. If Jupiter’s daughter Aphrodite should enter the field, thou mayest wound her with thy sharp spear.” The goddess disappeared and Diomedes flew back to the foremost ranks with renewed ardor. Behind him came his followers, ready to strip his victims of their armor and to carry away the captured horses and chariots. Æneas called upon Pandarus and said: “Where are to-day thy bow and never-failing arrows? Here is a chance to distinguish thyself. See, there is a man who has slain many, and none of our warriors can prevail against him.”

“That is Diomedes, son of Tydeus,” interrupted Pandarus; “he must be under the protection of a god. Already my arrow has wounded him so that blood spurted from the place, and in spite of this he is again in the field wielding his deadly lance. I dare not aim at him again, for it is unlucky to contend with the gods. Besides, I came on foot to Ilium and have no horses or chariot.”

“Come, friend, take mine and learn what Trojan horses are. Here, take the whip and reins, while I remain on foot and watch the fight.”

“Do thou guide the steeds thyself, Æneas, for they know thee; else might Diomedes take them captive and slay us too. I will meet him with the point of my sharp spear.”

Together they mounted the handsome chariot and dashed toward Diomedes, who was driving across the field with Sthenelus. “Look!” cried Sthenelus. “There come two heroes making for us. Let me turn back, for they seem bold warriors, and thou art weary with long fighting and thy painful wound.”

“Not so,” said Diomedes angrily. “It is not my custom thus to flee. I will await them here, and if one of them escape, the other shall be my prey. Do thou follow me, and if I should wound them both, seize thou the enemy’s steeds. I know them. They are magnificent horses of the famous breed which Jupiter once gave to King Thoas for his captured son Ganymede. Hasten, for the chariot is already upon us.”

He swung himself to the ground and at the same moment Pandarus’ arrow struck his shield, and though it made him stagger, he shook the shield in Pandarus’ face and cried: “Do not triumph too soon, but rather take care that thou thyself escape death!” Æneas turned his steeds in terror, but he could not save his friend; Diomedes’ spear had struck him down. As Æneas descended to bear away the body, he too was sorely wounded. Sthenelus meanwhile led away the beautiful steeds and they were taken to Diomedes’ tents.

Aphrodite now approached her fainting son and her merciful arms bore him off the field. “It must be a goddess who has rescued him,” said Diomedes to himself. “But it can be none other than Aphrodite, who appears so unwarlike. Good, I will overtake her and attain undying fame.” He hastened after the goddess, swung his spear, and wounded her in the wrist, so that her clear blood stained the earth. The goddess screamed and let the warrior slip from her arms, but he was again rescued by Phœbus Apollo, who covered him with a dark cloud.

Diomedes still pursued the goddess with loud cries. “Retire, daughter of Jupiter, and leave the battlefield to men. It is bad enough that thou causest women to bring such misery upon the nations. Woe to thee shouldst thou come near me in the fight!” The goddess was terrified and fled as fast as she could. Iris came to meet her and conducted her to the edge of the battlefield, where Mars, the god of war, sat gloating over his work. A cloud surrounded him and concealed him from mortal eyes. “Dear brother,” said Aphrodite, “lend me thy horses that I may quickly reach Olympus. Look! A mortal has wounded me.” Iris took the reins and the horses flew swiftly away through the air.

Meanwhile Diomedes was still on the field seeking Æneas, and not until he heard Apollo’s threatening voice, “Take heed, son of Tydeus, and give way, tremble and do not strive with the gods,” did he desist and remember Athena’s warning. Apollo carried Aphrodite’s son to his sacred temple on the heights of Pergamus. There he healed and strengthened him, and the hero soon reappeared among his followers, who were amazed at the miracle. He at once plunged into the fight and slew many brave youths among the Achaians.

Apollo had meanwhile complained to Mars of the defeat of the Trojans and of Diomedes’ insolence in daring to attack the gods. The god of war, who inclined first to one side, then to the other, was persuaded to take part in the battle himself, and this time to support the Trojans. Concealed in a cloud, he strode first before Hector, then before another Trojan, and wherever he went the aim never failed. Diomedes, however, had been endowed by his friend Athena with the power to recognize the gods when they appeared amongst men, so that he was terrified, as he was about to throw himself upon Hector, to see the war god striding before him. He started back, and hastening toward the other Greek warriors cried: “Take care, friends, give way and do not contend with the gods! For Hector hath ever a god at his side. Mars is with him now in the guise of a mortal.” Diomedes, in awe of Mars, retired from the field, although the battle still raged. Hector slew two of the bravest Greek warriors and captured their horses. Ajax of Salamis looked grimly on, but did not dare attack him; he preferred to pursue a weaker man, Amphius of Pæsus.

The battle had begun almost under the walls of Troy, but the Greeks had been forced back nearly to the ships, and they began to lose courage. Juno and Athena now determined to protect their favorites; for had they not promised Menelaus to avenge his wrongs? They signed Hebe to hitch the horses to the splendid chariot. Athena donned her breastplate, put on her golden helmet, and took up her mighty lance and the shield called ægis. It was decorated with golden tassels and in the midst was the head of Medusa, the mere sight of which turned men to stone. Thus armed, she mounted the shining chariot, and Juno, standing beside her, guided the steeds. The gates of heaven, guarded by the Horæ, opened of themselves and the goddesses stormed the heights of Olympus, where the father of the gods was sitting in solitude looking down upon the confusion. “Art thou not angered, Father Jupiter,” spake Juno, “that Mars is destroying the great and noble Achaian people? Wilt thou object if I force him from the field?”

Jupiter answered: “To work! Set Pallas Athena upon him. She will soon discomfit him.”

Overjoyed at the permission, Juno turned the horses and in an instant they had descended to the field before Troy. They paused where the Simois flows into the Scamander and enveloped chariot and steeds in a thick cloud. Then they hastened to the side of Tydeus’ son, and in Stentor’s shape and with his brazen voice Juno cried out: “Shame upon ye, people of Argos, so glorious to look upon and so faint-hearted. When Achilles was among you, the Trojans scarce ventured from the gates, but now that the only man among you is gone, they push you back to the ships.”

Athena approached Diomedes where he stood beside his chariot, cooling the wound which Pandarus had inflicted. He was just beginning to feel the pain of it and could scarcely move his arm. He loosened the leather straps and pressed out the blood. “Shame upon you, son of Tydeus,” said the goddess reproachfully. “Thou art not as thy noble father. He was more eager for the fray and slew countless men of Cadmus’ race before Thebes. Thou knowest that I never leave thy side. Speak, how can fear have dominion over thee?”

“Goddess,” answered the hero, “for I recognize thy voice, neither sloth nor fear restrain me, but I remember thy command. I plunged into the thick of the fight and piled corpse on corpse, until I saw Mars, the terrible, who fights in the front ranks of the Trojans. I gave way before him and warned the others; for who shall fight against the gods?”

The goddess answered: “Diomedes, beloved of my soul, henceforth fear neither Mars nor any of the immortals, for I am beside thee. Turn thy prancing horses upon Mars and wound him boldly at close range, the unstable one.”

She then took Sthenelus’ place in the chariot, wearing the helm of Aides, which rendered her invisible even to Mars. She guided the chariot straight towards him. When Mars saw Diomedes approaching he turned towards him, and leaning over, was about to plunge his spear into his body, but Athena turned it aside, and now Diomedes gave him such a thrust in the side that a mortal would certainly have succumbed. He withdrew the shaft and Mars fled, howling like ten thousand men. Both Achaians and Trojans were terrified at the din and Diomedes was amazed at his own deed and saw with astonishment the god rise up into the sky. There he showed the painful wound to Jupiter and complained loudly of Athena.

But the father of the gods answered grimly: “Spare me thy whining! I despise thee above all the gods. Thou hast always loved quarrels and bickerings and art as stubborn and contentious as thy mother, Juno. But I cannot see my son suffer.” With these words he commanded Pæon, the physician of Olympus, to heal him. He placed a cooling balm upon the wound and Mars was healed, for he was immortal. Then Juno bathed him and clothed him with soft garments. As soon as the murderous Mars had been driven from the field the goddesses returned to the dwellings of the Olympian gods.

The day was declining, but once more the Achaians pressed forward with renewed courage, knowing that Mars was no longer on the field. The Trojans gave way before them, and soon they were near enough to see again the elders and the women upon the city walls. Hector and Æneas did their best to spur the soldiers to resistance, but without avail. Then Helenus, one of Priam’s sons, who had the gift of prophecy, spake unto Hector: “Dear brother, do thou and Æneas try once more to encourage the people. Then go and leave the battle to us. Hasten into the city. Tell our mother quickly to summon the noble women of the city to Athena’s sacred temple and there to lay her most costly garment in the lap of the goddess. Furthermore she shall promise to sacrifice twelve yearling calves upon Athena’s altar, if she will repulse that terrible warrior, Tydeus’ son.”

Hector carried out his brother’s bidding and while he was away the Achaians regained the supremacy. Nestor went busily about admonishing them not to waste any time in collecting booty, but only to kill, kill, kill. Afterward, he said, there would be plenty of time to strip the accoutrements from the slain. Diomedes the insatiable, panting still for fresh conquests, espied a man among the Trojans whom he had never seen before, but who appeared by his rich armor, his stature, and commanding mien to be one of the leaders. When they had approached each other within a spear’s cast, they both reined in their steeds and Diomedes cried out to the enemy: “Who art thou, excellent sir? I have not seen thee before, although thou seemest to be a practised warrior. Art thou some god? Then would I not contend with thee, for such rashness hath ever brought misfortune to a mortal. But if thou art a man like myself, advance, that thou mayest quickly meet thy doom.”

It was Glaucus, Hippolochus’ son, who answered: “Oh son of Tydeus, dost thou ask who I am? The children of men are like the leaves of the forest, blown about by the winds and budding anew when Spring approaches. One flourishes and another fades. My race is a glorious one. It sprang from the Argive land and my ancestors ruled the city of Ephyra. Anolus was the founder of my family; Sisyphus, his son, was that wise king whose son was Glaucus; his son in turn the glorious Bellerophon, endowed by the gods with superhuman beauty and strength. Who has not heard of his heroic deeds? He slew Chimæra, the creature with a lion’s head, a dragon’s tail, and body of a goat—a savage, ravening monster. Next he conquered the king’s hostile neighbors, gaining every battle. The king gave him his beautiful daughter and half of his kingdom. His two sons were Isander and Hippolochus, who is my father. He sent me hither to Troy and admonished me to excel all others and never to disgrace my ancestors.”

Diomedes planted his spear in the sand, crying joyfully: “Then thou art my friend for old times’ sake. My grandfather Œneus entertained the glorious Bellerophon in his house for twenty days, and on his departure they exchanged gifts in token of friendship. Œneus’ gift was a purple girdle and Bellerophon’s a golden goblet, which I have in my possession and often admire. Therefore thou shalt be my guest in Argos and I thine, if I should ever visit Lycia. So let us avoid each other in the battle. There remain enough Trojans for me and enough Achaians for thee to kill. But as a pledge of the agreement let us exchange armor that it may be seen that we are friends of old standing.” They descended from their chariots, shook hands cordially, and took off their armor. Glaucus got the worst of the bargain, for his breastplate and shield were of gold, while those of Diomedes were only of brass. However, he gave them up gladly. They then renewed their vows of friendship and drove rapidly away in opposite directions.

When Hector reached the Scæan gate he was surrounded by Trojan women inquiring for their sons, brothers, and husbands, but he could not stay to comfort them and hastened away to his father’s palace, where he sought out his venerable mother, Hecuba. “Dear son,” she began, “why hast thou deserted the battlefield to come hither? The cruel Achaians are pressing us hard. But tarry until I bring thee good wine, that thou mayest make an offering to the gods and then refresh thyself; for wine giveth strength to a weary man.”

“Not so, mother,” answered Hector. “Befouled as I am, how can I sacrifice to the gods? Not for this did I come hither, but to bring thee a message from Helenus.” Then he repeated his brother’s instructions and Hecuba hastened to obey them.

Hector meanwhile made his way to the handsome palace of Paris, where he found his brother turning over and examining his weapons. Helen sat by the fireside among her maidens, occupied with domestic tasks. “Strange man!” said Hector. “I cannot understand thy conduct. The people are melting away before the walls and this bloody battle is chiefly on thine account. Thou wert always bitter against the slothful and hast ever encouraged others to fight. Come, let us go, before the city is fired by the enemy.”

“Gladly will I follow thee, brother,” answered Paris. “Thy reproaches are just. I have been brooding upon my misfortune, but my wife has just persuaded me to return to the field, and I am ready. Tarry a while until I have put on my armor or else go and I will follow thee.”

“Dear Hector,” spake gracious Helen sadly, “how it grieves me to see you all engaged in this cruel war, for the sake of a contemptible woman like myself. O that I had been destroyed at birth or had been flung into the sea! Or, if the gods have destined me to such misfortune, would at least that I had fallen into the hands of a brave man, who would take the disgrace and reproaches of his family to heart and could wipe out his shame by heroic deeds. But Paris is not a man. Enter and be seated, Hector, for thou has toiled most arduously in my behalf and suffered most for thy brother’s crime.”

“Thy gracious invitation I may not accept,” answered Hector, “for my heart urges me to return to aid the Trojans. I beg thee persuade Paris to overtake me before I leave the city. Now I must go to my own house to see my wife once more and little son; for who knoweth whether I shall ever return?”

He did not find his spouse at home, but on the tower at the Scæan gate, where she was following the fate of the Trojans. As he neared the gate she came to meet him, the modest, sensible Andromache, and behind her came the nurse with the little boy. His loving wife took him tenderly by the hand and wept over him. “Thy courage will surely be thy death,” she said. “Take pity on thy miserable wife and infant son, for the Achaians will surely kill thee, and then I had best sink into the earth; for what would remain for me? I am alone. Hector, thou art father and mother and brother to me, my precious husband. Take pity on me and remain in the tower. Do not make me a widow and thy son an orphan.”

Hector answered: “Dearly beloved, I am troubled also at thy fate, but I could not face the Trojan people if I shunned danger like a coward. True, I foresee the day when sacred Ilium will fall, bringing disaster upon the king and all the people, and thy fate touches me more nearly than that of father, mother, or brothers. Thou mayest be carried away to slavery in Argos to labor for a cruel mistress. Rather would I be in the grave than see thee in misery.”

Sadly the hero stretched out his arms to his boy, but the child hid his face in the nurse’s bosom, terrified at the helmet with its fluttering plumes. Smiling, the father took it off and laid it on the ground, and now the boy went to him willingly. He kissed the child tenderly, and turning his eyes heavenward prayed fervently; “Jupiter and ye other gods, grant that my boy may be a leader among the Trojans like his father and powerful in Ilium, that sometime it may be said: ‘He is much greater than his father.’ May his mother rejoice in him.”

As he placed the child in its mother’s arms, she smiled through her tears. “Poor wife,” he said, caressing her, “do not grieve too much. I shall not be sent to Hades unless it is my fate—no one can escape his destiny, be he high or low. Do thou attend to thine affairs at home and keep thy maidens busily at work. Men are made for war, and I most of all.” He picked up his helmet and hurried away. Andromache went also, but often turned to gaze after her dear husband.

Paris overtook his brother at the gate. “Do not be angry, brother, at my tardiness,” he said. “My good fellow,” answered Hector, “thou art a brave warrior, but often indifferent. I cannot bear the scornful gossip of the people who are enduring so much for thy sake. But we will talk of this another time—perhaps when we shall make a thankoffering for the defeat of the Achaians.” Thus speaking they hastened towards the battlefield.

To the weary Trojans the appearance of the two heroes was as welcome as a long-desired breeze after a calm at sea to a sailor, and they soon made their presence felt. Pierced by Paris’ arrow, the excellent Menestheus fell and Hector slew the valiant Eïoneus. Many another who had believed Hector far away met death at his hands.

Then came his brother Helenus, the seer, and bade him summon a warrior from among the Achaians to come forth and fight with him in single combat. The gods had revealed to him that the day of Hector’s doom was not yet come. Immediately the hero ran to the front, and requesting a truce cried out: “Hear me, ye Trojans and Achaians! Jupiter hath brought to naught our agreement, and our quarrel has not been settled as we hoped. Let us now arrange a second combat. Send your most valiant warrior forth to fight with me. If he slay me, let him take my costly armor, but my body he shall send to Ilium, that my bones may be burned and the ashes preserved. Should the gods grant that I slay him, then I will hang his armor in the temple of Phœbus Apollo. But ye may raise a fitting monument on the shore, so that when his grandchild sails the Hellespont and passes the high promontory he may say: ‘That is the mighty monument to the brave hero whom Hector slew in the final combat.’”

For a while all was quiet in the Greek camp. Each was waiting for the other to offer himself, for it was a hazardous undertaking. At last Menelaus arose, overcome by a rising feeling of shame, and cried angrily to the other princes: “Ha! ye who can boast so well at home and on the battlefield are women, where is your courage now? It would indeed be our everlasting shame if none of the Achaians dared match himself with Hector. Sit still, ye cowards! I will gird myself for the fight. The victory lies in the hands of the immortal gods.”

He began to put on his armor, but the other kings, and even his brother, restrained him. “Stay, my brother,” said Agamemnon; “do not be in a hurry to take up the challenge. Some other valiant Achaian will doubtless come forward.” Menelaus reluctantly obeyed, and now old Nestor began to reproach the faint-hearted warriors. “Your hearts have no courage and your bones no marrow,” he said. “If I were like myself of old, when I slew the hero Ereuthalion, Hector should soon find his man.”

Abashed at Nestor’s well-merited rebuke, nine men arose and came forward. Agamemnon himself was among them and the two Ajaxes; the others were Diomedes, Ulysses, Idomeneus, and his charioteer Meriones, Eurypylus, and Thoas. It was proposed that they draw lots, and it fell to the elder Ajax, who was proud of the honor that had come to him. “I trust that Jupiter will give me the victory, for I am not unskilful and fear not the foeman; but pray for me that Jupiter may give me success,” he said.

Ajax now rushed forward to meet the waiting Hector. Truly he was no mean adversary, being a man of powerful build. His armor was impenetrable and it was this fact alone which now saved him from certain death. His shield was composed of seven layers of cowhide with an iron covering; helmet and breastplate were equally strong. According to the custom of the time, the combat did not begin at once and in silence, but the warriors first paused to taunt and revile each other.

Ajax cried out: “Now thou canst see, Hector, that there are still men among the Achaians who are not afraid to accept thy challenge, even though Achilles is not with us. I am but one of many. Come, let us to work!”

“Thinkest thou to anger me by thy defiance, son of Telamon?” answered Hector. “Do not deceive thyself. I know how to hurl the spear and turn the shield so that no bolt can touch me. My deeds bear witness to my words. Beware, valiant hero, I shall not attack thee with craft, but openly.”

At the same moment he hurled the great spear with all his might, and it pierced six of the leathern layers of Ajax’s shield before its power was spent. Ajax quickly aimed his own at Hector’s breast. Hector’s shield was not strong enough to withstand the blow; however, by a quick turn of his body, he prevented the point from entering his flesh. Both men now withdrew their spears from the shields and threw themselves upon each other. But Hector’s well-aimed blow only blunted the point of his lance and Ajax’s spear slipped on the smooth surface of Hector’s shield, wounding him slightly in the neck. Then Hector turned hastily to pick up a stone, which he hurled with all his might at Ajax’s head, but the hero warded it off with his shield. Ajax then picked up a much larger stone, which he threw, breaking Hector’s shield and wounding his knee. No doubt Hector would have attacked him once more had the Greeks themselves not interfered, sending forward a herald who separated the heroes, saying: “Warriors, it is enough. Ye are good fighters and beloved of Jupiter; that we have all seen. But night is falling and the darkness bids us cease our strife.”

“Very well, friend,” said Ajax. “Bid Hector lay down his arms, for he began the fight. When he is ready to stop, I also am willing.”

Then Hector said calmly: “Ajax, thou hast borne thyself manfully and some god hath lent thee strength and skill. Let us now rest and renew the fight another time, until death shall claim one of us. Go thou to feast with thy people, while I return to Priam’s city. But before we part let us exchange gifts that future generations may say, ‘Behold, they fought a bitter fight, then parted in friendship.’”

Thereupon he presented Ajax with his finely-chased sword with its graceful scabbard and Ajax gave him his purple belt. Thus they parted, each side welcoming his man with cries of triumphant joy. Agamemnon entertained the chieftains in his tent as usual and to-day he set the largest and choicest pieces before Ajax. When the meal was ended Nestor began: “Listen to my advice, chieftains. Let us pause to-morrow long enough to bury our dead. We will burn the bodies that each may gather the ashes of his friends to bear them home to his people. But here we will erect a great monument to mark the place where the brave warriors have fallen. I have also another proposal to make. What think ye if we should hastily construct a deep moat and a bulwark with a great gateway around our camp? Then we should be as safe in our tents as in a walled city.” The counsel of the old man was received with universal approval and Agamemnon determined to set to work at once.

The Trojan princes too were holding council to decide what they should do to force the Achaians to retire. Antenor, the wise, urged the return of Helen, but none would consent, not even Priam and Hector, to force Paris to give up his beloved wife. “I will gladly return the treasure which we took from Menelaus,” he said, “and give him plentifully of mine own, if that will propitiate the Achaians. But never will I give up Helen.”

“For the present let us be on our guard,” answered King Priam, “and to-morrow let Idæus go down and give Paris’ message to the Achaians and ask if they are not inclined to an armistice, until we have burned the dead and paid them funeral honors.”

Early the next morning Idæus went forth on his errand. He entered Agamemnon’s tent and delivered his message. The Greeks welcomed the proposal for a truce, but Paris’ offer was rejected with disdain. “Let no one take Paris’ property,” roared Diomedes. “We no longer fight for Paris’ wealth, nor even for Helen. Even though he should send her back, Troy shall fall, and truly the end is not far off!” Agamemnon and the other chieftains all signified their approval and the herald took the message back to the city.

Meanwhile the greater part of the Achaians were engaged in digging a moat and building a wall about the camp. The outcome showed that this precaution had not been unnecessary, for as soon as the battle was renewed the Achaians began to lose ground. Jupiter forbade the gods to take sides, and driving the celestial steeds himself, he descended from Olympus to Mount Ida, from whence he could observe the battlefield. The slaughter had begun early in the morning and already many Trojans had fallen, and still more Achaians, for the Trojans fought desperately.

A little past noon a threatening storm gathered on Mount Ida and the people recognized the presence of the father of the gods, for he alone had power over the flashing lightning. It was soon apparent whom he favored, for suddenly a terrible thunderbolt with blinding flashes struck the foremost ranks of the Achaians, so that all were panic-stricken and none dared remain on the field against the will of Jupiter. All fled to the ships, pale with terror. Nestor was about to follow, when an arrow from Paris’ bow laid one of his horses low, and if Diomedes had not come to his rescue, he would certainly have fallen a prey to the pursuing Trojans. Filled with renewed courage at the thunderbolts of Jove, which they took for favorable omens, they were like dogs on the track of the frightened flock. Hector called loudly upon his people to attack the wall and gave orders that firebrands be brought from the city to fire the ships. But the Trojans were dubious about attacking the Greeks within their fortifications. They were not well prepared for such an undertaking.

The Greeks now stood behind the wall, huddled close to the ships. The terrible thunderstorm had passed over and the sun shone once more. Agamemnon boarded a ship, where he might be seen and heard by all. The warriors were silent while he cried: “Shame upon you, sons of Argos, who in Lemnos boasted that ye would each fight one hundred Trojans! Now ye flee like frightened deer before a single man. Already Hector threatens to burn the ships. No wonder! It is your cowardice which makes him bold. Oh, father Jupiter, hast thou ever cursed a king as thou hast me? And yet how many fat cattle have I not offered up? On the way hither I did not pass by a single one of thy sacred temples where I did not stop to burn fat haunches in thine honor. Thou hast doubtless determined to destroy us here.”

Full of pity, the father of gods and men looked down upon him and made a sign that he would save the Danæans. He sent an eagle bearing a young deer in its beak, which it dropped as it flew high above the Greek camp, so that it fell palpitating before the altar of Jupiter on the ships. As soon as the Greeks saw this favorable sign, they pressed forward with fresh zeal into the Trojan lines. The heroes were like ravening wolves. Teucer of Salamis, who was skilful with the bow, remained beside his brother Ajax, who covered him with his shield whenever he was in danger. Every arrow hit its mark. Agamemnon looked on with delight, and clapping the youth on the shoulder, he cried: “Well done, my dear fellow! Thus shalt thou bring joy and glory to thy father in his old age. If the gods grant me the victory over Troy thy reward shall not fail—whether it be a tripod, a pair of horses and a chariot, or a beautiful slave girl.”

Soon afterward Hector’s chariot came galloping up. Teucer quickly set an arrow to his bow and aimed at the hero, but the missile went astray and Hector did not see the youth. Teucer shot another arrow, which pierced the charioteer’s breast. Hector sprang down, and just as Teucer was taking aim for the third time, a rock from Hector’s hand struck his breast and he sank on his knees. Ajax covered him with his shield until soldiers came up and carried the wounded youth away to his tent.

Juno and Athena, gazing sadly at the unfortunate outcome of the battle, ventured in their resentment to disobey the command of the father of the gods and go to the rescue of the hard-pressed Achaians. But Jupiter espied them and sent the gold-winged Iris to warn them to turn back or he would strike them with a thunderbolt that would shatter their chariot and teach them not to resist father and husband. Pouting, they obeyed, and in a rage arrived at Olympus and seated themselves in the great hall. Soon afterwards the mountain trembled at the tread of Jupiter, who entered the hall and seated himself on his golden throne with dark looks at his wife and daughter, whose glances were fixed defiantly on the ground.

“Why are ye so sad?” he began mockingly. “Ye did not remain long on the battlefield, meseems. Your lovely limbs trembled ere ever ye saw the fray. Truly ye would never have returned to the glorious home of the gods had my thunderbolt struck you. My power is far beyond that of the other gods. Even should they all come to measure their strength against mine, and if I stood at heaven’s gate and let down a chain to earth and all Olympus hung to the chain, ye could not pull me down. If I but raised my hand ye would all fly up. Even the earth and sea I would draw up, and if I should wind the chain around the peaked top of Olympus, the whole globe would dangle in space.”

Meanwhile night had fallen, which put a stop to further strife. Hector retired to the middle of the field and gave orders that the whole army should remain in camp lighting watchfires everywhere, so that the Greeks might not board their ships unseen and steal away. The old men and boys were to watch the city gates to guard against surprise.

Fear and unrest prevailed in the camp by the ships, and even Agamemnon was no longer confident. He quietly called the chieftains to a council of war. “Friends,” he said, “I perceive that Jupiter is not inclined to fulfil the promise of his omens and no longer desires that I take Troy and lead ye home laden with booty. He has already destroyed many of us and our misery grows greater day by day. Surely he is but making sport of us. Therefore let us launch our ships and return home, saving at least those of us who are left.”

For a while the princes were silent. Then Diomedes sprang up and spake: “Do not be angry, O King, if I disagree with thee. It seems to me thou art faint-hearted, for none of us has given up hope. Truly the gods do not give everything to one man, and Jupiter has made thee a powerful king; but valor, the flower of manly virtues, he has denied thee. If thou art so anxious to return, very good; then go. The way is open and the ships are ready. But the rest of us will remain until we have destroyed Priam’s fortress. And if all others should flee, I would remain with my friend Sthenelus, for it is the gods who have brought us hither.”

All the warriors applauded this, and when Nestor had praised Diomedes’ words, there was no further talk of retreat. The venerable man now counselled that the walls should be carefully guarded and that watchfires should be lighted everywhere. He signed to Agamemnon to invite the friends into his tent, offer them refreshment, learn each one’s opinion, and to follow the best.

Nestor was the first to speak. “Great Atride,” he began, “if thou wilt consider when it was the gods began to compass our ruin, thou wilt admit that our misfortunes began on the day when thou didst unjustly insult and abuse, to our great sorrow, that most valiant man whom even the immortals have honored. We were all displeased and thou knowest how I tried to dissuade thee. I think that even now we had better seek to conciliate the angry man with flattering words and gifts.”

“Honored Nestor,” answered Agamemnon, “I will not deny that I was in the wrong. It is true a single man, if chosen by the gods, is equal in might to an army. But having offended I will gladly make amends and offer him every atonement. I will give him rich gifts and he shall have, besides, the maiden over whom we quarrelled. How glad I would have been to return her as soon as my rage had cooled. If Jupiter will but grant me the good fortune to destroy Priam’s mighty fortress, Achilles’ vessel shall be heaped up with gold and silver and he may select twenty Trojan women for himself, the fairest after Helen. And when we return to Argos I will refuse him none of my daughters, should he wish to become my son-in-law, and will present him with seven of my most populous cities as a wedding gift. Thus will I honor him if he be willing to forget.”

To this Nestor answered: “Son of Atreus, thou dost offer princely gifts which might well propitiate the proudest. Let us send messengers to him. Let them be Ulysses and Ajax and the venerable Phœnix, whom his father Peleus sent hither as his companion and friend. Let the heralds, Hodius and Eurybates, accompany them.”

The encampment of the Myrmidons was on the seashore and they found Achilles in his tent, apart from the others, playing the harp and singing of heroic deeds. His good friend and comrade, Patroclus, sat opposite him listening. Ajax and Ulysses entered first and Achilles immediately put down his harp and came towards them. Patroclus also arose to welcome his old comrades.

“Ye are heartily welcome, old friends,” began Achilles, “for I am not angry with you. Sit on these cushions and, Patroclus, bring a tankard and mix the wine, for we have honored guests here.”

After they had eaten and poured out a libation to the gods, Ulysses took the goblet and drank to Achilles with a hearty handclasp. “Greeting to thee, Pelide,” he began. “It is not food and drink we crave. But we are troubled that thou art not on the battlefield. The Trojans have pushed forward to the ships and nothing stops them. Jupiter has sent fiery tokens to encourage them and the invincible Hector is hard upon us with murder in his eye. Already he has threatened to burn the ships. Even at night he does not retire, but encamps on the open field and the whole plain is illumined by his campfires. No doubt he is now eagerly awaiting daybreak to destroy us, for he fears neither gods nor men.

“Hear what Agamemnon offers thee—gifts so costly that they would suffice to make any man rich and powerful. Ten pounds of gold will he give thee, and seven new tripods, with twenty polished basins, besides twelve magnificent horses and seven Lesbian slave women accompanying Briseïs’ daughter. And when we shall have conquered Priam’s city, thou shalt heap thy ship with gold and bronze and take twenty of Troy’s fairest women for thyself. And when we return to blessed Argos thou shalt be his son-in-law and he will honor thee as his own son. But if thy hatred of Atreus’ son is so great that thou canst not forgive him, then consider the dire need of the Achaian people, who are ready to pay thee honor like a god. Truly thou shalt earn great glory.”

Achilles answered him: “Noble son of Laërtes, let me open my heart to thee frankly. Neither Agamemnon nor any other Greek can move me to fight again for this ungrateful people. The coward and the hero enjoy equal reputation among you. Why should I risk my life for others? As the swallow feeds its young with the morsels which it denies itself, thus I have spent my sweat and blood these many days for the ungrateful Achaian people; have watched through many a restless night, fought brave men, burning their houses and stealing away their women and children. I have destroyed twelve populous cities in Troy by sea and eleven by land and always delivered the spoils up to Agamemnon. He remained quietly at the ships and took my plunder gladly, keeping always the greater part for himself. Although each chieftain received a princely gift, he took mine from me—the lovely woman who was dear to me as a spouse.