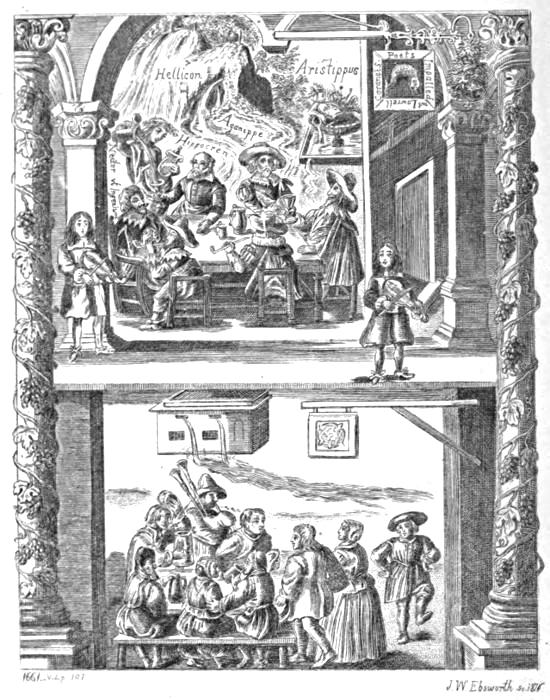

1661. Vide p. 107.

J. W. Ebsworth sc. 1876

Choyce Drollery.

Choyce

DROLLERY:

SONGS & SONNETS.

BEING

A Collection of Divers Excellent

Pieces of Poetry,

OF SEVERAL EMINENT AUTHORS.

Now First Reprinted from the Edition of 1656.

TO WHICH ARE ADDED THE EXTRA SONGS OF

MERRY DROLLERY, 1661,

AND AN

ANTIDOTE AGAINST MELANCHOLY, 1661:

EDITED,

With Special Introductions, and Appendices of Notes,

Illustrations, Emendations of Text, &c.,

By J. Woodfall Ebsworth, M.A., Cantab.

BOSTON, LINCOLNSHIRE:

Printed by Robert Roberts, Strait Bar-Gate.

M,DCCCLXXVI.

TO THOSE

STUDENTS OF ART,

AMONG WHOM HE FOUND

Friendship and Enthusiasm;

BEFORE HE LEFT THEM,

Winners of Unsullied Fame,

AND SOUGHT IN A QUIET NOOK

Content, instead of Renown:

THESE

“DROLLERIES OF THE RESTORATION”

ARE BY THE EDITOR

DEDICATED.

| PAGE | |

| DEDICATION | v |

| PRELUDE | ix |

| INTRODUCTION TO “CHOICE DROLLERY, 1656” | xi |

| § 1. HOW CHOICE DROLLERY WAS INHIBITED | xi |

| 2. THE TWO COURTS IN 1656 | xix |

| 3. SONGS OF LOVE AND WAR | xxvi |

| 4. CONCLUSION: THE PASTORALS | xxxiii |

| ORIGINAL “ADDRESS TO THE READER,” 1856 | |

| “CHOYCE DROLLERY,” 1656 | 1 |

| TABLE OF FIRST LINES TO DITTO | 101 |

| INTRODUCTION TO “ANTIDOTE AGAINST MELANCHOLY,” 1661 | |

| § 1. REPRINT OF “ANTIDOTE” | 105 |

| 2. INGREDIENTS OF “AN ANTIDOTE” | 108 |

| ORIGINAL ADDRESS “TO THE READER,” 1661 | 111 |

| ” CONTENTS (ENLARGED) | 112 |

| [viii]“ANTIDOTE AGAINST MELANCHOLY,” 1661 | 113 |

| EDITORIAL POSTSCRIPT TO DITTO: § 1. ON THE “AUTHOR” OF THE ANTIDOTE. 2. ARTHUR O’BRADLEY | 161 |

| “WESTMINSTER DROLLERIES,” EDITION 1674: EXTRA SONGS | 177 |

| “MERRY DROLLERY,” 1661: | |

| PART 1. EXTRA SONGS | 195 |

| ” 2. DITTO | 233 |

| APPENDIX OF NOTES, &c., ARRANGED IN FOUR PARTS: | |

| 1. “CHOICE DROLLERY” | 259 |

| 2. “ANTIDOTE AGAINST MELANCHOLY” | 305 |

| 3. “WESTMINSTER DROLLERY,” 1671-4 | 333 |

| 4. § 1. “MERRY DROLLERY,” 1661 | 345 |

| 2. ADDITIONAL NOTES TO “M. D.,” 1670 | 371 |

| 3. SESSIONS OF POETS | 405 |

| 4. TABLES OF FIRST LINES | 411 |

| FINALE | 423 |

J. W. E.

June 1st, 1876.

Charles.—“They say he is already in the forest of Arden, and a many merry men with him; and there they live like the old Robin Hood of England. They say many young gentlemen flock to him every day, and fleet the time carelessly, as they did in the golden world.”

(As You Like It, Act i. sc. 1.)

We may be sure the memory of many a Cavalier went back to that sweetest of all Pastorals, Shakespeare’s Comedy of “As You Like It,” while he clutched to his breast the precious little volume of Choyce Drollery, Songs and Sonnets, which was newly published in the year 1656. He sought a covert amid the yellowing fronds of fern, in some old park that had not yet been wholly confiscated by the usurping Commonwealth; where, under the broad shadow of a beech-tree, with the squirrel[xii] watching him curiously from above, and timid fawns sniffing at him suspiciously a few yards distant, he might again yield himself to the enjoyment of reading “heroick Drayton’s” Dowsabell, the love-tale beginning with the magic words “Farre in the Forest of Arden”—an invocative name which summoned to his view the Rosalind whose praise was carved on many a tree. He also, be it remembered, had “a banished Lord;” even then remote from his native Court, associating with “co-mates and brothers in exile”—somewhat different in mood from Amiens or the melancholy Jacques; and, alas! not devoid of feminine companions. Enough resemblance was in the situation for a fanciful enthusiasm to lend enchantment to the name of Arden (p. 73), and recall scenes of shepherd-life with Celia, the songs that echoed “Under the greenwood-tree;” without needing the additional spell of seeing “Ingenious Shakespeare” mentioned among “the Time-Poets” on the fifth page of Choyce Drollery.

Not easily was the book obtained; every copy at that time being hunted after, and destroyed when found, by ruthless minions of the Commonwealth. A Parliamentary injunction had been passed against it. Commands were given for it to be burnt by the hangman. Few copies escaped, when spies and informers were numerous, and fines were levied upon[xiii] those who had secreted it. Greedy eyes, active fingers, were after the Choyce Drollery. Any fortunate possessor, even in those early days, knew well that he grasped a treasure which few persons save himself could boast. Therefore it is not strange, two hundred and twenty years having rolled away since then, that the book has grown to be among the rarest of the Drolleries. Probably not six perfect copies remain in the world. The British Museum holds not one. We congratulate ourselves on restoring it now to students, for many parts of it possess historical value, besides poetic grace; and the whole work forms an interesting relic of those troubled times.

Unlike our other Drolleries, reproduced verbatim et literatim in this series, we here find little describing the last days of Cromwell and the Commonwealth; except one graphic picture of a despoiled West-Countryman (p. 57), complaining against both Roundheads and “Cabbaleroes.” The poems were not only composed before hopes revived of speedy Restoration for the fugitive from Worcester-fight and Boscobel; they were, in great part, written before the Civil Wars began. Few of them, perhaps, were previously in print (the title-page asserts that none had been so, but we know this to be false). Publishers made such statements audaciously, then as now, and forced truth to limp behind them without chance of[xiv] overtaking. By far the greater number belonged to an early date in the reign of the murdered King, chiefly about the year 1637; two, at the least, were written in the time of James I. (viz., p. 40, a contemporary poem on the Gunpowder Plot of 1605; and, p. 10, the Ballad on King James I.), if not also the still earlier one, on the Defeat of the Scots at Muscleborough Field; which is probably corrupted from an original so remote as the reign of Edward VI. “Dowsabell” was certainly among the Pastorals of 1593, and “Down lay the Shepherd’s swain” (p. 65) bears token of belonging to an age when the Virgin Queen held sway. These facts guide to an understanding of the charm held by Choyce Drollery for adherents of the Monarchy; and of its obnoxiousness in the sight of the Parliament that had slain their King. It was not because of any exceptional immorality in this Choyce Drollery that it became denounced; although such might be declared in proclamations. Other books of the same year offended worse against morals: for example, the earliest edition known to us of Wit and Drollery, with the extremely “free” facetiæ of Sportive Wit, or Lusty Drollery (both works issued in 1656), held infinitely more to shock proprieties and call for repression. The Musarum Deliciæ of Sir J[ohn] M[ennis] and Dr. J[ames] S[mith], in the same year, 1656, cannot[xv] be held blameless. Yet the hatred shewn towards Choyce Drollery far exceeded all the rancour against these bolder sinners, or the previous year’s delightful miscellany of merriment and true poetry, the Wit’s Interpreter of industrious J[ohn] C[otgrave]; to whom, despite multitudinous typographical errors, we owe thanks, both for Wit’s Interpreter and for the wilderness of dramatic beauties, his Wit’s Treasury: bearing the same date of 1655.

It was not because of sins against taste and public or private morals, (although, we admit, it has some few of these, sufficient to afford a pretext for persecutors, who would have been equally bitter had it possessed virginal purity:) but in consequence of other and more dangerous ingredients, that Choyce Drollery aroused such a storm. Not disgust, but fear of its influence in reviving loyalty, prompted the order of its extermination. Readers at this later day, might easily fail to notice all that stirred the loyal sentiments of chivalric devotion, and consequently made the fierce Fifth-Monarchy men hate the small volume worse than the Apocrypha or Ikon Basilike. Herein was to be found the clever “Jack of Lent’s” account of loyal preparations made in London to receive the newly-wedded Queen, Henrietta Maria, when she came from France, in 1625, escorted by the Duke of Buckingham, who compromised her sister by his rash attentions: Buckingham,[xvi] whom King Charles loved so well that the favouritism shook his throne, even after Felton’s dagger in 1628 had rid the land of the despotic courtier. Here, also, a more grievous offence to the Regicides, was still recorded in austere grandeur of verse, from no common hireling pen, but of some scholar like unto Henry King, of Chichester, the loyal “New-Year’s Wish” (p. 48) presented to King Charles at the beginning of 1638, when the North was already in rebellion: wherein men read, what at that time had not been deemed profanity or blasphemy, the praise and faithful service of some hearts who held their monarch only second to their Saviour. Referring to their hope that the personal approach of the King might cure the evils of the disturbed realm, it is written:—

Here was a sincere, unflinching recognition of Divine Right, such as the faction in power could not possibly abide. Even the culpable weakness and ingratitude of Charles, in abandoning Strafford, Laud, and other champions to their unscrupulous destroyers, had not made true-hearted Cavaliers falter in their faith to him. As the best of moralists declares:—

These loyal sentiments being embodied in print within our Choyce Drollery, suitable to sustain the fealty of the defeated Cavaliers to the successor of the “Royal Martyr,” it was evident that the Restoration must be merely a question of time. “If it be now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come: the readiness is all!”

To more than one of those who had sat in the ill-constituted and miscalled High Court of Justice, during the closing days of 1648-9, there must have been, ever and anon, as the years rolled by, a shuddering recollection of the words written anew upon the wall in characters of living fire. They had shown themselves familiar, in one sense much too familiar, with the phraseology but not the teaching of Scripture. To them the Mene, Mene, Tekel Upharsin needed no[xviii] Daniel come to judgment for interpretation. The Banquet was not yet over; the subjugated people, whom they had seduced from their allegiance by a dream of winning freedom from exactions, were still sullenly submissive; the desecrated cups and challices of the Church they had despoiled, believing it overthrown for ever, had been, in many cases, melted down for plunder,—in others, sold as common merchandize: and yet no thunder heard. But, however defiantly they might bear themselves, however resolute to crush down every attempt at revolt against their own authority, the men in power could not disguise from one another that there were heavings of the earth on which they trod, coming from no reverberations of their footsteps, but telling of hollowness and insecurity below. They were already suspicious among themselves, no longer hiding personal spites and jealousies, the separate ambition of uncongenial factions, which had only united for a season against the monarchy and hierarchy, but now began to fall asunder, mutually envenomed and intolerant. Presbyterian, Independent, and Nondescript-Enthusiast, while combined together of late, had been acknowledged as a power invincible, a Three-fold Cord that bound the helpless Victim to an already bloody altar. The strands of it were now unwinding, and there scarcely needed much prophetic wisdom to discern that one by one they could soon be broken.

To us, from these considerations, there is intense attraction in the Choyce Drollery, since it so narrowly escaped from flames to which it had been judicially condemned.

At this date many a banished or self-exiled Royalist, dwelling in the Low Countries, but whose heart remained in England, drew a melancholy contrast between the remembered past of Whitehall and the gloomy present. With honest Touchstone, he could say, “Now am I in Arden! the more fool I. When I was at home I was in a better place; but travellers must be content.”

Meanwhile, in the beloved Warwickshire glades, herds of swine were routing noisily for acorns, dropped amid withered leaves under branches of the Royal Oaks. They were watched by boys, whose chins would not be past the first callow down of promissory beards when Restoration-day should come with shouts of welcome throughout the land.

In 1656 our Charles Stuart was at Bruges, now and then making a visit to Cologne, often getting into difficulties through the misconduct of his unruly followers, and already quite enslaved by Dalilahs, syrens against whom his own shrewd sense was powerless to defend him. For amusement he read his favourite[xx] French or Italian authors, not seldom took long walks, and indulged himself in field sports:

For he was only scantily supplied with money, which chiefly came from France, but if he had possessed the purse of Fortunatus it could barely have sufficed to meet demands from those who lived upon him. A year before, the Lady Byron had been spoken of as being his seventeenth Mistress abroad, and there was no deficiency of candidates for any vacant place within his heart. Sooth to say, the place was never vacant, for it yielded at all times unlimited accommodation to every beauty. Music and dances absorbed much of his attention. So long as the faces around him showed signs of happiness, he did not seriously afflict himself because he was in exile, and a little out at elbows.

Such was the “Banished Duke” in his Belgian Court; poor substitute for the Forest of Ardennes, not far distant. By all accounts, he felt “the penalty of Adam, the season’s difference,” and in no way relished the discomfort. He did not smile and say,

For, in truth, he much preferred avoiding such counsel,[xxi] and relished flattery too well to part with it on cheap terms. He never considered the “rural life more sweet than that of painted pomp,” and, if all tales of Cromwell’s machinations be held true, Charles by no means found the home of exile “more free from peril than the envious court.” On the other hand, his own proclamation, dated 3rd May, 1654, offering an annuity of five hundred pounds, a Colonelcy and Knighthood, to any person who should destroy the Usurper (“a certain mechanic fellow, by name Oliver Cromwell!”), took from him all moral right of complaint against reprisals: unless, as we half-believe, this proclamation were one of the many forgeries. As to any sweetness in “the uses of Adversity,” Charles might have pleaded, with a laugh, that he had known sufficient of them already to be cloyed with it.

The men around him were of similar opinion. A few, indeed, like Cowley and Crashaw, were loyal hearts, whose devotion was best shown in times of difficulty. Not many proved of such sound metal, but there lived some “faithful found among the faithless”; and

The Ladies of the party scarcely cared for anything beyond self-adornment, rivalry, languid day-dreams of future greatness, and the encouragement of gallantry.

There was not one among them who for a moment can bear comparison with the Protector’s daughter, Elizabeth Claypole—perhaps the loveliest female character of all recorded in those years. Everything concerning her speaks in praise. She was the good angel of the house. Her father loved her, with something approaching reverence, and feared to forfeit her conscientious approval more than the support of his companions in arms. In worship she shrank from the profane familiarity of the Sectaries, and devotedly held by the Church of England. She is recorded to have always used her powerful influence in behalf of the defeated Cavaliers, to obtain mercy and forbearance. Her name was whispered, with blessing implored upon it, in the prayers of many whom she alone had saved from death.[1] No personal ambition, no foolish pride and ostentation marked her short career. The searching glare of Court publicity could betray no flaw in her conduct or disposition; for the[xxiii] heart was sound within, her religion was devoid of all hypocrisy. Her Christian purity was too clearly stainless for detraction to dare raise one murmur. She is said to have warmly pleaded in behalf of Doctor Hewit, who died upon the scaffold with his Royalist companion, Sir Harry Slingsby, the 8th of June, 1658 (although she rejoiced in the defeat of their plot, as her extant letter proves). Cromwell resisted her solicitations, urged to obduracy by his more ruthless Ironsides, who called for terror to be stricken into the minds of all reactionists by wholesale slaughter of conspirators. Soon after this she faded. It was currently reported and believed that on her death-bed, amid the agonies and fever-fits, she bemoaned the blood that had been shed, and spoke reproaches to[xxiv] the father whom she loved, so that his conscience smote him, and the remembrance stayed with him for ever.[2] She was only twenty-nine when at Hampton Court she died, on the 6th of August, 1658. Less than a month afterwards stout Oliver’s heart broke. Something had gone from him, which no amount of power and authority could counter-balance. He was not a man to breathe his deeper sorrows into the ear of those political adventurers or sanctified enthusiasts whose glib tongues could rattle off the words of consolation.[xxv] While she was slowly dying he had still tried to grapple with his serious duties, as though undisturbed. Her prayers and her remonstrances had been powerless of late to make him swerve. But now, when she was gone, the hollow mockery of what power remained stood revealed to him plainly; and the Rest that was so near is not unlikely to have been the boon he most desired. It came to him upon his fatal day, his anniversary of still recurring success and happy fortune; came, as is well known, on September 3rd, 1658. The Destinies had nothing better left to give him, so they brought him death. What could be more welcome? Very few of these who reach the summit of ambition, as of those other who most lamentably failed, and became bankrupt of every hope, can feel much sadness when the messenger is seen who comes to lead them hence,—from a world wherein the jugglers’ tricks have all grown wearisome, and where the tawdry pomp or glare cannot disguise the sadness of Life’s masquerade.

It was still 1656, of which we write (the year of Choyce Drollery and Parnassus Biceps, of Wit and Drollery and of Sportive Wit); not 1658: but shadows of the coming end were to be seen. Already it was evident that Cromwell sate not firmly on the throne, uncrowned, indeed, but holding power of sovereignty. His health was no longer what it had been of old. The iron constitution was breaking up. Yet was he only nine months older than the century. In September his new Parliament met; if it can be called a Parliament in any sense, restricted and coerced alike from a free choice and from free speech, pledged beforehand to be servile to him, and holding a brief tenure of mock authority under his favour. They might declare his person sacred, and prohibit mention of Charles Stuart, whose regal title they denounced. But few cared what was said or done by such a knot of praters. More important was the renewed quarrel with Spain; and all parties rejoiced when gallant Blake and Montague fell in with eight Spanish ships off Cadiz, captured two of them and stranded others. There had been no love for that rival fleet since the Invincible Armada made its boast in 1588; but what had happened in “Bloody Mary’s” reign, after her union with Philip, and the later cruelties wrought under Alva against the patriots of the[xxvii] Netherlands, increased the national hatred. We see one trace of this renewed desire for naval warfare in the appearance of the Armada Ballad, “In eighty-eight ere I was born,” on page 38 of our Choyce Drollery: the earliest copy of it we have met in print. Some supposed connection of Spanish priestcraft with the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 (Guido Faux and several of the Jesuits being so accredited from the Low Country wars), may have caused the early poem on this subject to be placed immediately following.

But the chief interest of the book, for its admirers, lay not in temporary allusions to the current politics and gossip. Furnishing these were numerous pamphlets, more or less venomous, circulating stealthily, despite all watchfulness and penalties. Next year, 1657, “Killing no Murder” would come down, as if showered from the skies; but although hundreds wished that somebody else might act on the suggestions, already urged before this seditious tract appeared, not one volunteer felt called upon to immolate himself to certain death on the instant by standing forward as the required assassin. Cautious thinkers held it better to bide their time, and await the natural progress of events, allowing all the enemies of Charles and Monarchy to quarrel and consume each other. Probably the bulk of country farmers and their labourers cared not one jot how things fell[xxviii] out, so long as they were left without exorbitant oppression; always excepting those who dwelt where recently the hoof of war-horse trod, and whose fields and villages bore still the trace of havoc. Otherwise, the interference with the Maypole dance, and such innocent rural sports, by the grim enemies to social revelry, was felt to be a heavier sorrow than the slaughter of their King.[3] So long as wares were sold, and profits gained, Town-traders held few sentiments of favour towards either camp. It was (owing to the parsimony of Parliament, and his continual need of supplies to be obtained without their sanction,) the frequency of his exactions, the ship-money, the forced loans, and the uncertainty of ever gaining a repayment, which had turned many hearts against King Charles I., in his long years of difficulty, before shouts arose of “Privilege.” But for the cost of wasteful revels at Court, with gifts to favourites, the expense of foreign or domestic wars, there would have been no popular complaint against tyranny. Citizens care little about questions of Divine Right and Supremacy, pro or con, so long as they are left[xxix] unfettered from growing rich, and are not called on to disgorge the wealth they swallowed ravenously, perhaps also dishonestly. Some remembrance of this fact possessed the Cavaliers, even before George Monk came to burst the city gates and chains. The Restoration confirmed the same opinion, and the later comedies spoke manifold contempt against time-serving traders; who cheated gallant men of money and land, but in requital were treated like Acteon.

Although, in 1656, disquiet was general, amid contemporary records we may seek far before we meet a franker and more manly statement of the honest Englishman’s opinion, despising every phase of trickery in word, deed, or visage, than the poem found in Choyce Drollery, p. 85,—“The Doctor’s Touchstone.” There were, doubtless, many whose creed it stated rightly. A nation that could feel thus, would not long delay to pluck the mask from sanctimonious hypocrites, and drag “The Gang” from out their saddle.

Here, too, are the love-songs of a race of Poets who had known the glories of Whitehall before its desecration. Here are the courtly praises of such beauties as the Lady Elizabeth Dormer, 1st Countess of Carnarvon, who, while she held her infant in her arms, in 1642, was no less fascinating than she had been in her virgin bloom. The airy trifling, dallying[xxx] with conceits in verse, that spoke of a refinement and graceful idlesse more than passionate warmth, gave us these relics of such men as Thomas Carew, who died in 1638, before the Court dissolved into a Camp. Some of them recal the strains of dramatists, whose only actresses had been Ladies of high birth, condescending to adorn the Masques in palaces, winning applause from royal hands and voices. These, moreover, were “Songs and Sonnets” which the best musicians had laboured skilfully to clothe anew with melody: Poems already breathing their own music, as they do still, when lutes and virginals are broken, and the composer’s score has long been turned into gun-wadding.

What sweetness and true pathos are found among them, readers can study once more. The opening poem, by Davenant, is especially beautiful, where a Lover comforts himself with a thought of dying in his Lady’s presence, and being mourned thereafter by her, so that she shall deck his grave with tears, and, loving it, must come and join him there:—

Seeing, alongside of these tender pleadings from the worshipper of Beauty, some few pieces where the taint of foulness now awakens our disgust, we might feel wonder at the contrast in the same volume, and the taste of the original collector, were not such feeling of wonder long ago exhausted. Queen Elizabeth sate out the performance of Love’s Labour’s Lost (if tradition is to be believed), and was not shocked at some free expressions in that otherwise delightful play;—words and inuendoes, let us own, which were a little unsuited to a Virgin Queen. Again, if another tradition be trustworthy, she herself commissioned the comedy of Merry Wives of Windsor to be written and acted, in order that she might see Falstaffe in[xxxii] love: but after that Eastcheap Boar’s-Head Tavern scene, with rollicking Doll Tear-sheet, in the Second Part of Henry IV., surely her sedate Majesty might have been prepared to look for something very different from the proprieties of “Religious Courtship” or the refinements of Platonic affection in the Knight, who, having “more flesh than other men,” pleads this as an excuse for his also having more frailty.

Suppose we own at once, that there is a great deal of falsehood and mock-modesty in the talk which ever anon meets us, the Puritanical squeamishness of each extremely moral (undetected) Tartuffe, acting as Aristarchus; who cannot, one might think, be quite ignorant of what is current in the newspaper-literature of our own time.[5] The fact is this, people now-a-days keep their dishes of spiced meat and their Barmecide show-fasts separate. They sip the limpid spring before company, and keep hidden behind a[xxxiii] curtain the forbidden wine of Xeres, quietly iced, for private drinking. Our ancestors took a taste of both together, and without blushing. Their cup of nectar had some “allaying Tyber” to abate “the thirst complaint.” They did not label their books “Moral and Theological, for the public Ken,” or “Vice, sub rosa, for our locked-cabinet!” Parlons d’autres choses, Messieurs, s’il vous plâit.

There were good reasons for Court and country being associated ideas, if only in contrast. Thus Touchstone states, when drolling with Colin, as to a Pastoral employment:—“Truly, shepherd in respect of itself it is a good life; but in respect it is not in the Court, it is tedious.” The large proportion of pastoral songs and poems in Choyce Drollery is one other noticeable characteristic. Even as Utopian schemes, with dreams of an unrealized Republic where laws may be equally administered, and cultivation given to all highest arts or sciences, are found to be most popular in times of discontent and tyranny, when no encouragement[xxxiv] for hope appears in what the acting government is doing; even so, amid luxurious times, with artificial tastes predominant, there is always a tendency to dream of pastoral simplicity, and to sing or paint the joys of rural life. In the voluptuous languor of Miladi’s own boudoir, amid scented fumes of pastiles and flowers, hung round with curtains brought from Eastern palaces, Watteau, Greuze, Boucher, and Bachelier were employed to paint delicious panels of bare-feeted shepherdesses, herding their flocks with ribbon-knotted crooks and bursting bodices; while goatherd-swains, in satin breeches and rosetted pumps, languish at their side, and tell of tender passion through a rustic pipe. The contrast of a wimpling brook, birds twittering on the spray, and daintiest hint of hay-forks or of reaping-hooks, enhanced with piquancy, no doubt, the every-day delights of fashionable wantonness. And as it was in such later times with courtiers of La belle France surrounding Louis XV., so in the reign of either Charles of England—the Revolution Furies crept nearer unperceived.

Recurrence to Pastorals in Choyce Drollery is simply in accordance with a natural tendency of baffled Cavaliers, to look back again to all that had distinguished the earlier days of their dead monarch, before Puritanism had become rampant. Even Milton, in his[xxxv] youthful “Lycidas,” 1637, showed love for such Idyllic transformation of actual life into a Pastoral Eclogue. (A bitter spring of hatred against the Church was even then allowed to pollute the clear rill of Helicon: in him thereafter that Marah never turned to sweetness.) Some of these Pastorals remain undiscovered elsewhere. But there can be no mistaking the impression left upon them by the opening years of the seventeenth, if not more truly the close of the sixteenth, century. Dull, plodding critics have sneered at Pastorals, and wielded their sledge-hammers against the Dresden-china Shepherdesses, as though they struck down Dagon from his pedestal. What then? Are we forbidden to enjoy, because their taste is not consulted?——

Always will there be some smiling virtuosi, here or elsewhere, who can prize the unreal toys, and thank us for retrieving from dusty oblivion a few more of these early Pastorals. When too discordantly the factions jar around us, and denounce every one of moderate opinions or quiet habits, because he is unwilling to become enslaved as a partisan, and fight under the banner that he deems disgraced by falsehood[xxxvi] and intolerance, despite its ostentatious blazon of “Liberation” or “Equality,” it is not easy, even for such as “the melancholy Cowley,” to escape into his solitude without a slanderous mockery from those who hunger for division of the spoil. Recluse philosophers of science or of literature, men like Sir Thomas Browne, pursue their labour unremittingly, and keep apart from politics; but even for this abstinence harsh measure is dealt to them by contemporaries and posterity whom they labour to enrich. It is well, no doubt, that we should be convinced as to which side the truth is on, and fight for that unto the death. Woe to the recreant who shrinks from hazarding everything in life, and life itself, defending what he holds to be the Right. Yet there are times when, as in 1656, the fight has gone against our cause, and no further gain seems promised by waging single-handedly a warfare against the triumphant multitude. Patience, my child, and wait the inevitable turn of the already quivering balance!—such is Wisdom’s counsel. Butler knew the truth of Cavalier loyalty:—

Some partizans may find a paltry pleasure in dealing stealthy stabs, or buffoons’ sarcasms, against the foes they could not fairly conquer. Some hold a silent dignified reserve, and give no sign of what they hope or fear. But for another, and large class, there will be solace in the dreams of earlier days, such as the Poets loved to sing about a Golden Pastoral Age. Those who best learnt to tell its beauty were men unto whom Fortune seldom offered gifts, as though it were she envied them for having better treasure in their birthright of imagination. The dull, harsh, and uncongenial time intensified their visions: even as Hogarth’s “Distressed Poet”—amid the squalour of his garret, with his gentle uncomplaining wife dunned for a milk-score—revels in description of Potosi’s mines, and, while he writes in poverty, can feign himself possessor of uncounted riches. Such power of self-forgetfulness was grasped by the “Time-Poets,” of whom our little book keeps memorable record.

So be it, Cavaliers of 1656. Though Oliver’s troopers and a hated Parliament are still in the ascendant, let your thoughts find repose awhile, your hopes regain bright colouring, remembering the plaints of one despairing shepherd, from whom his Chloris fled; or of that other, “sober and demure,”[xxxviii] whose mistress had herself to blame, through freedoms being borne too far. We, also, love to seek a refuge from the exorbitant demands of myriad-handed interference with Church and State; so we come back to you, as you sit awhile in peace under the aged trees, remote from revellers and spies, “Farre in the Forest of Arden”—O take us thither!—reading of happy lovers in the pages of Choyce Drollery. Since their latest words are of our favourite Fletcher, let our invocation also be from him, in his own melodious verse:—

J. W. E.

September 2nd, 1875.

Choyce

DROLLERY:

SONGS & SONNETS.

BEING

A Collection of divers excellent

pieces of Poetry,

OF

Severall eminent Authors.

Never before printed.

LONDON,

Printed by J. G. for Robert Pollard, at the

Ben. Johnson’s head behind the Exchange,

and John Sweeting, at the

Angel in Popes-Head Alley.

1656.

Courteous Reader,

Thy grateful reception of our first Collection hath induced us to a second essay of the same nature; which, as we are confident, it is not inferioure to the former in worth, so we assure our selves, upon thy already experimented Candor, that it shall at least equall it in its fortunate acceptation. We serve up these Delicates by frugall Messes, as aiming at thy Satisfaction, not Saciety. But our designe being more upon thy judgement, than patience, more to delight thee, to detain thee in the portall of a tedious, seldome-read Epistle; we draw this displeasing Curtain, that intercepts thy (by this time) gravid, and almost teeming fancy, and subscribe,

R. P.

[On the welcoming of Queen Henrietta Maria, 1625].

FINIS.

| page. | |

| A Maiden of the Pure Society | 44 |

| A story strange I will you tell | 31 |

| A Stranger coming to the town | 16 |

| And will this wicked world never prove good? | 40 |

| As I went to Totnam | 45 |

| Blacke eyes, in your dark orbs do lye | 81 |

| Cloris, now thou art fled away | 63 |

| Come, my White-head, let our Muses | 10 |

| Deare Love, let me this evening dye | 1 |

| Down lay the Shepheards Swain | 65 |

| Drink boyes, drink boyes, drink and doe not spare | 42 |

| Farre in the Forrest of Arden | 73 |

| Fire! Fire! O, how I burn | 97 |

| Fuller of wish, than hope, methinks it is | 62 |

| He that a Tinker, a Tinker, a Tinker will be | 52 |

| Hide, oh hide those lovely Browes | 53 |

| How happy’s that Prisoner that conquers, &c. | 93 |

| I keep my horse, I keep my W | 60 |

| I love thee for thy curled hair | 49 |

| I never did hold, all that glisters is gold | 85 |

| [102]I tell you all, both great and small | 68 |

| Idol of our sex! Envy of thine own! | 55 |

| If at this time I am derided | 9 |

| In Celia a question did arise | 80 |

| In Eighty-eight, ere I was born | 38 |

| Let not, sweet saint, let not these eyes offend you | 92 |

| List, you Nobles, and attend | 20 |

| My Mother hath sold away her Cock | 43 |

| Never was humane soule so overgrown | 17 |

| No Gypsie nor no Blackamore | 88 |

| Nor Love, nor Fate dare I accuse | 4 |

| Oh fire, fire, fire, where? | 33 |

| On the twelfth day of December | 78 |

| One night the great Apollo, pleas’d with Ben | 5 |

| Shall I think, because some clouds | 15 |

| She’s not the fairest of her name | 99 |

| The Chandler grew neer his end | 72 |

| There is not halfe so warme a fire | 61 |

| This day inlarges every narrow mind | 48 |

| ’Tis late and cold, stir up the fire | 100 |

| ’Tis not how witty, nor how free | 98 |

| Trust no more a wanton Wh— | 90 |

| Uds bodykins, Chill work no more | 57 |

| We read of Kings, and Gods that kindly took | 83 |

| What ill luck had I, silly maid that I am | 84 |

| When first the magick of thine eye | 8 |

| When James in Scotland first began | 70 |

AN

ANTIDOTE

AGAINST

MELANCHOLY:

Made up in PILLS.

Compounded of Witty Ballads, Jovial

Songs, and Merry Catches.

Printed by Mer. Melancholicus, to be sold in London

and Westminster, 1661.

[Aprill, 18.]

Having found that sixty-five of our previous pages, in the second volume of the Drolleries Reprint, were filled with songs and poems that also appear in the Antidote against Melancholy, 1661; and that all the remaining songs and poems of the Antidote (several being only obtainable therein) exceed not the compass of three additional sheets, or forty-eight pages, the Editor determined to include this valuable[106] book. Thus in our three volumes are given four entire works, to exemplify this particular class of literature, the Cavalier Drolleries of the Restoration.[7]

To that portion of our present Appendix which is devoted to Notes to the Antidote against Melancholy, 1661, we refer the reader for the admirable brief Introduction written by John Payne Collier, Esq.; to whose handsome Reprint of the work we owe our first acquaintance with its pages. His knowledge of our old literature extends over nearly a century; his opportunities for inspecting private and public libraries have been peculiarly great; and he has always been most generous in communicating his knowledge to other students, showing throughout a freedom from jealousy and exclusiveness reminding us of the genial Sir Walter Scott. He states:—“We have never seen a copy of an ‘Antidote against Melancholy’ that was not either imperfect, or in some places illegible from dirt and rough usage, excepting the one we have employed: our single exemplar is as fresh as on the day it was issued from the press. There is an excellent and highly finished engraving on the title-page, of gentlemen and boors carousing; but as the repetition[107] of it for our purpose would cost more than double every other expense attending our reprint, we have necessarily omitted it. The same plate was afterwards used for one of Brathwayte’s pieces; and we have seen a much worn impression of it on a Drollery near the end of the seventeenth century. It does not at all add to our knowledge of the subject of our reprint. J. P. C.”

Nevertheless, the copper-plate illustration is so good, and connects so well with the Bacchanalian and sportive character of the “Antidote against Melancholy,” and other Drolleries, that the present Editor not unwillingly takes up the graver to reproduce this frontispiece for the adornment of the volume and the service of subscribers. Our own Reprint and our engraving are made from the perfect specimen contained in the Thomason Collection, and dated 1661 (with “Aprill 18” in MS.; see p. 161). We make a rule always to go to the fountain-head for our draughts, howsoever long and steep may be the ascent. Flowers and rare fossils reward us as we clamber up, and in good time other students learn to trust us, as being pains-taking and conscientiously exact. The first duty of one who aspires to be honoured as the Editor of early literature is to faithfully reproduce his text, unmutilated and undisguised. To amend it, and elucidate it, so far as lies in his power, can be done[108] befittingly in his notes and comments, while he gives his readers a representation of the original, so nearly in fac-simile as is compatible with additional beauty of typography. Throughout our labours we have held this principle steadily in view; and, whatever nobler work we may hereafter attempt, the same determination must guide us. There may be debate as to our wisdom in reproducing some questionable facetiæ, but there shall be none regarding our fidelity to the original text.

A pleasant book it appeared to Cavaliers and all who were not quite strait-laced. It is almost unobjectionable, except for a few ugly words, and bears comparison honourably with “Merry Drollery” or “Wit and Drollery,” both of the same date, 1661. Unlike the former, it is almost uninfected with political rancour or impurity. It is a jovial book, that roysters and revellers loved to sing their Catches from; nay, if some laughing nymphs did not drop their eyes over its pages we are no conjurors. A vulgar phrase or two did not frighten them. Lucy Hutchinson herself, the Colonel’s Puritan wife, fires many a volley of coarse epithets without blushing; and, indeed, the Saintly Crew occasionally indulged in foul language as freely as the Malignants, though it was condoned as being theologic zeal and controversial phraseology.

In “The Ex-Ale-tation of Ale” we forgive the verbosity, for the sake of one verse on the noted Ballad-writer (see note in Appendix):—

We find the character of the songs to be eminently festive: almost every one could be chanted over a cup of burnt Sack, and there was not entire forgetfulness of eating: witness “The Cold Chyne,” on page 55 (our p. 148). The Love-making is seldom visible. Such glimpses as we gain of Puritans (Bishop Corbet’s Hot-headed Zealot, Cleveland’s “Rotundos rot,”) are only suggestive of playful ridicule. The Sectaries, being no longer dangerous, are here laughed at, not calumniated. The odd jumble of nations brought together in those disturbed times is seen in the crowd of lovers around the “blith Lass of Falkland town” (p. 133) who is constant in her love of a Scottish blue bonnet:—“If ever I have a man, blew-Cap for me!” But, sitting at ease once more, not hunted into bye-ways or exile, and with enough of ready cash to wipe off tavern scores, or pay for braver garments than were lately flapping in the wind, the Cavaliers recall the exploits of their patron-saint, “St. George for England,” the gay wedding of Lord Broghill, as[110] described by Sir John Suckling in 1641, the still noisier marriage of Arthur o’ Bradley, or that imaginary banquet afforded to the Devil, by Ben Jonson’s Cook Lorrell, in the Peak of Derbyshire. Early contrasts, drawn by their own grandsires, between the Old Courtier of Queen Elizabeth and the New Courtier of King James, are welcomed to remembrance. They forgive “Old Noll,” while ridiculing his image as “The Brewer,” and they repeat the earlier Ulysses song of the “Blacksmith,” by Dr. James Smith, if only for its chorus, “Which no body can deny.” The grave solemnity wherewith Dr. Wilde’s “Combat of Cocks” was told; the light-hearted buffoonery of “Sir Eglamore’s Fight with the Dragon;” the spluttering grimaces of Ben Jonson’s “Welchman’s praise of Wales;” and the sustained humour as well as enthusiasm of Dr. Henry Edwards’s “On the Vertue of Sack” (“Fetch me Ben Jonson’s scull,” &c.), are all crowned by the musical outburst of “The Green Gown:”—

(see Appendix to Westminster Drollery, p. liv.) Our readers may thus additionally enjoy a full-flavoured bumper of the “Antidote against Melancholy.”

J. W. E.

August, 1875.

| Original: | Our | |||

| page. | vols, | page | ||

| 1. | The Exaltation of a Pot of Good Ale, | 1 | iii. | 113 |

| 2. | The Song of Cook-Lawrel, by Ben Johnson | 9 | ii. | 214 |

| 3. | The Ballad of The Black-smith, | 11 | 225 | |

| 4. | The Ballad of Old Courtier and the New | 14 | iii. | 125 |

| 5. | The Ballad of the Wedding of Arthur of Bradley, | 16 | ii. | 312 |

| 6. | The Ballad of the Green Gown, | 20 | i. | Ap. 54 |

| 7. | The Ballad of the Gelding of the Devil, | 21 | ii. | 200 |

| 8. | The Ballad of Sir Eglamore, | 25 | 257 | |

| 9. | The Ballad of St. George for England, | 26 | iii. | 129 |

| 10. | The Ballad of Blew Cap for me, | 29 | 133 | |

| 11. | The Ballad of the Several Caps, | 31 | 135 | |

| 12. | The Ballad of the Noses, | 33 | ii. | 143 |

| 13. | The Song of the Hot-headed Zealot, | 35 | 234 | |

| 14. | The Song of the Schismatick Rotundos, | 37 | iii. | 139 |

| 15. | A Glee in praise of Wine [Let souldiers], | 39 | ii. | 218 |

| 16. | Sir John Sucklin’s Ballad of the Ld. L. Wedding. | 40 | 101 | |

| 17. | The Combat of Cocks, | 44 | 242 | |

| 18. | The Welchman’s prayse of Wales, | 47 | iii. | 141 |

| 19. | The Cavaleer’s Complaint [and Answer], | 49 | ii. | 52 |

| 20. | Three several Songs in praise of Sack | |||

| [: Old Poets Hipocrin, &c. | 52 | iii. | 143 | |

| Hang the Presbyter’s Gill, | 53 | 144 | ||

| ’Tis Wine that inspires, | 54 | 145 | ||

| [A Glee to the Vicar, | W.D. Int. | |||

| [On a Cold Chyne of Beef, | 55 | iii. | 146 | |

| [A Song of Cupid Scorned, | 56 | 147 | ||

| 21. | On the Vertue of Sack, by Dr. Hen. Edwards | 57 | ii. | 293 |

| 22. | The Medly of Nations, to several tunes, | 59 | 127 | |

| 23. | The Ballad of the Brewer, | 62 | 221 | |

| 24. | A Collection of 40 [34] more Merry Catches and Songs. | 65-76 | iii. | 149 |

| [Of these 34, ten are given in Merry Drollery, Complete, on pages 296, 304, 308, 232, 337, 300, 280, 318, 348, and 341. The others are added in this volume | iii. | 52 | ||

[p. 1.]

[Followed by Ben Jonson’s Cook Lorrel, and by The Blacksmith: for which see Merry Drollery, Complete, pp. 214-17, 225-30.]

[p. 14.]

[Part Second.]

[Here follow, Arthur of Bradley (see Merry Drollery, Compleat, p. 312); The Green Gown: “Pan leave piping,” (see Westm. Droll., Appendix, p. 54); Gelding of the Devil: “Now listen a while, and I will you tell” (see Merry D., C., p. 200); Sir Egle More (ibid, p. 257); and St. George for England (ibid, p. 309). But, as the variations are great, in the last of these, it is here given from the Antidote ag. Mel., p. 26.]

[p. 26.]

[p. 30.]

[Next follow A Ballad of the Nose (see Merry Drollery, Compleat, p. 143), and A Song of the Hot-headed Zealot: to the tune of “Tom a Bedlam” (Dr. Richard Corbet’s, Ibid, p. 234).]

[p. 37.]

[The three next in the Antidote, respectively by Aurelian Townshend (?), Sir John Suckling, and “by T. R.” (or Dr. Thomas Wild?), are to be found also in our Merry Drollery, Compleat, pp. 218, 101, and 242. See Appendix Notes.]

[p. 47.]

[Followed, in An Antidote, by the excellent poems, The Cavalier’s Complaint; to the tune of (Suckling’s) I’le tell thee, Dick, &c., with The Answer. For these, see Merry Drollery, Compleat, pp. 52-56, and 367.]:

[p. 52.]

[p. 53.]

[p. 54.]

[Followed by A Glee to the Vicar, beginning, “Let the bells ring, and the boys sing:” for which see the Introduction to our edition of Westminster Drollery, pp. xxxvii-viii.]

[p. 55.]

[p. 56.]

[The three next are common to the Antidote and Merry Drollery, Compleat, with a few verbal differences: On the Vertue of Sack, by Dr. Henry Edwards; The Medley of the Nations; and The Brewer, A Ballad made in the Year 1657, To the Tune of The Blacksmith. For them, see M. D., C., pp. 293, 127, 221. These three poems are followed by “A Collection of Merry Catches,” thirty-four in number, of which only ten are found in Merry Drollery, Compleat, (viz., 3. “Now that the Spring;” 5. “Call George again;” 9. “She that will eat;” 13. “The Wise-men were but Seven;” 14. “Shew a room!” 15. “O! the wily wily Fox;” 17. “Now I am married;” 19. “There was three Cooks in Colebrook;” 22. “If any so wise is;” and 29. “What fortune had I,”) on pp. 296, 304, 308, 232, 337, 300, 280, 318, 348, and 341, respectively. See notes on them, also, in Appendix to M. D., C. One other, first in the Antidote, had appeared earlier in Choice Drollery, p. 52: “He that a Tinker,” &c., q.v.]

[p. 65.]

[p. 66.]

[p. 67.]

[p. 70.]

[p. 71.]

[p. 72.]

Translated out of Greek.

[p. 75.]

FINIS.

Thanks be to the worthy bookseller, George Thomason,[8] for prudence in laying aside the “tall copy” of this amusing book, from which we make our transcript of text and engraving. Probably it did not exceed two shillings, in price; (at least, we have seen[162] that Anthony à Wood’s uncropt copy of “Merry Drollery,” 1661, is marked in contemporary manuscript at “1s. 3d.,” each part). The title says:—

Who was the “N. D.” to whose light labours we are indebted for the compounding of these “Witty Ballads, jovial Songs, and merry Catches” in Pills warranted to cure the ills of Melancholy, had not hitherto been ascertained[9]; or whether he wrote anything beside the above couplet, and the humorous address To the Reader, beginning,

As we suspected (flowing though his verse might be), he was more of bookseller than ballad-maker. His injunctions for us to “be wise and buy, not borrow,” had a terribly tradesman-like sound. Yet he was right. Book-borrowing is an evil practice; and book-lending is not much better. Woeful chasms, in what should be the serried ranks of our Library companions, remind us pathetically, in too many cases (book-cases, especially,) of some Coleridge-like “lifter” of Lambs, who made a raid upon our borders, and carried off plunder, sometimes an unique quarto, on other days an irrecoverable duodecimo: With Schiller, we bewail the departed,—

The title of “Pills to Purge Melancholy” was by Playford and Tom D’Urfey afterwards employed, and kept alive before the public, in many a volume from before 1684 until 1720, if not later. Whether “N. D.” himself were the “Mer[cury] Melancholicus” whose name appears as printer, for the book to be “sold in London and Westminster,” is to us not doubtful. By April 18, 1661,[10] Thomason had secured his[164] copy, and there need be no question that it was for sport, and not through any fear of rigid censorship or malicious pettifogging interference by the law, that, instead of printer’s name, this pseudonym or nickname was adopted.

We believe that the mystery shrouding the personality of “N. D.” can be dispelled. The discovery helps us in more ways than one, and connects the Antidote against Melancholy, of 1661, in an intelligible and legitimate manner, with much jocular literature of later date. To us it seems clear that N. D. was no other than [He]n[ry] [Playfor]d. The triplets addressed in 1661 To the Reader, beginning “There’s no purge ’gainst Melancholy,” are repeated at commencement of the 1684 edition of “Wit and Mirth; or, an Antidote to Melancholy” (the third edition of “Pills to Purge Melancholy”) where they are entitled “The Stationer to the Reader,” and signed, not “N. D.,” but “H. P.;” for Henry Playford, whose name appears in full as publisher “near the Temple Church.” Thus, the repetition or alteration of the original title, “An Antidote against Melancholy, made up in Pills,” or, as the head-line puts it, “Pills to Purge Melancholy,” was, in all probability, a perfectly business-like reproduction of what Playford had himself originated. What relation Henry Playford was to John Playford, the publisher of “Select Ayres,”[165] “Choice Ayres,” 1652, &c., we are not yet certain. Thirteen of the longest and most important poems from the 1661 Antidote[11] re-appear in that of 1684, beside four of the Catches. Indeed, the transmission of many of these Lyrics (by the editions of 1699, 1700, 1706, 1707) to the six volume edition, superintended by Tom D’Urfey in 1719-20, is unbroken; though we have still to find the edition published between 1661 and 1684.

But even the 1661 Antidote is not entitled to bear the credit of originating the phrase: Pills to purge Melancholy. So far as we know, by personal search, this belongs to Robert Hayman, thirty years earlier. Among his Quodlibets, 1628, on p. 74, we find the following epigram:—

“To one of the elders of the Sanctified Parlour of Amsterdam.

(Merry Drollery, Compleat, p. 312, 395; Antidote ag. Mel., p. 16.)

So long ago as the Editor can remember, the words and music of “Arthur o’ Bradley’s Wedding” rang pleasantly in his ears. The jovial rollicking strain prepared him to feel interest in the bridal attire of Shakespeare’s Petruchio; who, not improbably, when about to be married unto “Kate the Curst,” borrowed the details of costume and demeanour from this popular hero of song. Or vice versa. To this day, the lilt of the tune holds a fascination, and we sometimes behold, under favourable planetary aspects, the long procession of dancing couples who have, during three centuries, footed the grass, the rashes, or chalked floor, to that jig-melody, accompanied by the[167] bagpipes or fiddle of some rustic Crowdero. Can it be possible? Yes, the line is headed by the venerable Queen Elizabeth, holding up her fardingale with tips of taper fingers, and looking preternaturally grim, to show that dancing is a serious undertaking for a virgin sovereign (especially when the Spanish Ambassador watches her, with comments of wonder that the Head of the Church can dance at all). Yet is there a sly under-glance that tells of fun, to those who are her Majesty’s familiars. Her “Cousin James” is not the neatest figure as a partner (which accounts for her having chosen Leicester instead, let alone chronology); but we see him, close behind, with Anne of Denmark, twirling his crooked little legs about in obedience to the music, until his round hose swell like hemispheres on school-maps. “Baby Charles and Steenie,” half mockingly, follow after with the Infanta. We did once catch a glimpse of handsome Carr and his wicked paramour, Frances Howard, trying to join the Terpsichorean revellers; but, beautiful as they both were, it was felt necessary to exclude them, “for the honour of Arthur o’ Bradley,” since they possessed none of their own. What a gallant assemblage of poets and dramatists covered the buckle and snapped their fingers gleefully to the merry notes! Foremost among them was rare Ben Jonson (unable to resist clothing Adam Overdo in Arthur’s own mantle); and[168] honest Thomas Dekker “followed after in a dream” (as had been memorably printed on our seventh page of Choyce Drollery), thinking of Bellafront’s repentance, and her quotation of the well-known burden, “O brave Arthur o’ Bradley, then!” A score of poets are junketting with merry milkmaids and Wives of Windsor. Richard Brathwaite (the creator of Drunken Barnaby) is not absent from among them; although he sees, outside the circle that for a moment has formed around a Maypole, an angry crowd of schismatic Puritans, who are scowling at them with malignant eyes, and denunciations misquoted from Scripture. Many a fair Precisian, nevertheless, yields to the honeyed pleading of a be-love-locked Cavalier, and the irresistible charms of “Arthur o’ Bradley, ho!” showing the prettiest pair of ankles, and the most delightful mixture of bashfulness and enjoyment; until the Roundhead Buff-coats prove too numerous, and whisk her off to a conventicle, where, the sexes sitting widely apart, for aught we know, the crop-eared rout sing unpoetic versions of the Psalmist to the tune of Arthur o’ Bradley, “godlified” and eke expurgated.

Cromwell, we know, loved music, withal, and it is not unlikely that those two ladies are his daughters, whom we behold dancing somewhat stiffly in John Hingston’s music-chamber; Mrs. Claypole and her sister, Mrs Rich: there are L’Estrange, who fiddles[169] to them, and Old Noll, smiling pleasantly, though the tune be Arthur o’ Bradley. Our Second Charles (not yet “Restored”) is also dancing to it, at the Hague (as we see in Janssen’s Windsor picture), with the Princess Palatine Elizabeth, and such a bevy of bright faces round them, that we lose our heart entirely. Can we not see him again—crowned now, and self-acknowledged as “Old Rowley”—at one of the many balls in Whitehall recorded by Samuel Pepys,[12] entering[170] gaily into all the mirth with that grave, swarthy face of his; not noticing the pouts of Catherine, who sits neglected while The Castlemaine laughs loudly, the fair Stewart simpers, and the little spaniels bark or caper through the palace, snapping at the dancers’ heels? Be sure that pretty Nelly and saucy Knipp were also well acquainted with the music of “rare Arthur o’ Bradley,” as indeed were thousands of the play-goers to whom the former once sold oranges.

And lower ranks delighted in it. Pierce, the Bagpiper, is himself the central figure, when we look again, “with cheeks as big as a mitre,” such time as that table-full of Restoration revellers (whom we catch sight of in our frontispiece to the Antidote, 1661) are beginning to shake a toe in honour of the music.

So it continues for two centuries more, with all varieties of costume and feature. Certain are we that plump Sir Richard Steele whistled the tune, and Dean Swift gave the Dublin ballad-singer a couple of thirteens for singing it. Dr. Johnson grunted an accompaniment whenever he heard the melody, and James Boswell insisted on dancing to it, though a little “overtaken,” and got his sword entangled betwixt his legs, which cost him a fall and a plastered head-piece, by no means for the only time on record. It is reported that good old George the Third was seen endeavouring to persuade Queen Charlotte to accompany[171] him on the Spinnet, while he set their numerous olive-branches jigging it delightedly “for the honour of Arthur o’ Bradley.” But whenever Dr. John Wolcot was reported to be prowling near at hand, with Peter Pindaresque eyes, the motion ceased. Well was it loved by honest Joseph Ritson, impiger, iracundus inexorabilis, acer—better than vegetable diet and eccentric spelling, or the flagellation of inexact antiquarian Bishops. We ourselves may have beheld him in high glee perusing the black-letter ballad, and rectifying its corrupt text by the Antidote against Melancholy’s. How lustily he skipped, shouting meanwhile the burden of “brave Arthur o’ Bradley!” so that unconsciously he joined the ten-mile train of dancers. They are still winding around us, some in a Nineteenth-Century garb (a little tattered, but it adds to the picturesqueness), blithe Hop-pickers of West-Bridge Deanery. There are a few New Zealanders, we understand, waiting to join the throng, (including Macaulay’s own particular circumnavigating meditator, yet unborn); so that as long as the world wags no welcome may be lacking to the mirth and melody, jigging and joustling,

Having relieved our feelings, for once, we resume the sober duties of Annotation in a chastened spirit:—

In Merry Drollery Compleat, Reprint (Appendix, p. 401), we gave the full quotation from a Sixteenth Century Interlude, The Contract of Marriage between Wit and Wisdom, the point being this:—

Arthur o’ Bradley is mentioned by Thomas Dekker, near the end of the first part of his Honest Whore, 1604; when Bellafront, assuming to be mad, hears that Mattheo is to marry her, she exclaims—

In Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair, 1614, (which covers the Puritans with ridicule, for the delight of James 1st.), Act ii. Scene 1, when Adam Overdo, the Sectary, is disguised in a “garded coat” as Arthur o’ Bradley, to gesticulate outside a booth, Mooncalf salutes him thus:—“O Lord! do you not know him, Mistress? ’tis mad Arthur of Bradley that makes the orations.—Brave master, old Arthur of Bradley, how do you do? Welcome to the Fair! When shall we hear you again, to handle your matters, with your back against a booth, ha?”

In Richard Brathwaite’s Strappado for the Diuell, 1615, p. 225 (in a long poem, containing notices of Wakefield, Bradford, and Kendall, addressed “to all true-bred Northerne Sparks, of the generous Society of the Cottoneers,” &c.) is the following reference to this tune, and to other two, viz. “Wilson’s Delight,” and “Mal Dixon’s Round:”

(By the way: The same author, Richard Brathwaite, in his amusing Shepherds Tales, 1621, p. 211, mentions as other Dance-tunes,

Again, Thomas Gayton writes concerning the hero:—“’Tis not alwaies sure that ’tis merry in hall when beards Wag all, for these men’s beards wagg’d as fast as they could tag ’em, but mov’d no mirth at all: They were verifying that song of—

On pp. 540, 604, of William Chappell’s excellent work, The Popular Music of the Olden Time, are given two tunes, one for the Antidote version, and the other for the modern, as sung by Taylor, “Come neighbours, and listen a while.” He quotes the two lines from Gayton, and also this from Wm. Wycherley’s Gentleman Dancing Master, 1673, Act i, Sc. 2, where Gerrard says:—“Sing him ‘Arthur of Bradley,’ or ‘I am the Duke of Norfolk.’”

It is quite evident, from such passages, that during a long time a proverbial and popular character attached to this noisy personage: such has not yet passed away. The earliest complete imprint of “Arthur o’ Bradley” as a Song, (from a printed original, of 1656, beginning “All[174] you that desire to merry be,”) in our present Appendix, Part iv. Quite distinct from this hitherto unnoticed examplar, not already reprinted, is “Saw you not Pierce, the piper,” &c., the ballad reproduced by us, from Merry Drollery, 1661, Part 2nd., p. 124, (and ditto, Compleat 1670, 1691, p. 312); which agrees with the Antidote against Melancholy, same date, 1661, p. 16. More than a Century later, an inferior rendering was common, printed on broadsheets. It was mentioned, in 1797, by Joseph Ritson, as being a “much more modern ballad [than the Antidote version] upon this popular subject, in the same measure intitled Arthur o’ Bradley, and beginning ‘All in the merry month of May.’” (Robin Hood, 1797, ii. 211.) Of this we already gave two verses, (in Appendix to M. Drollery C., p. 400), but as we believe the ballad has not been reprinted in this century, we may give all that is extant, from the only copy within reach, of Arthur o’ Bradley:—

In this, doubtless, we detect two versions, garbed together. What is now the final verse is merely a variation of the sixth: probably the broadsheet-printer could not meet with a genuine eighth verse. Robert Bell denounced the whole as “a miserable composition” (even as he had declared against the amatory Lyrics of Charles the Second’s time): but then, he might have added, with Goldsmith, “My Bear dances to none but the werry genteelest of tunes.”

Far superior to this was the “Arthur o’ Bradley’s Wedding:

“Come, neighbours, and listen awhile, If ever you wished to smile,” &c.,[175] which was sung by ... Taylor, a comic actor, about the beginning of this century. It is not improbable that he wrote or adapted it, availing himself of such traditional scraps as he could meet with. Two copies of it, duplicate, on broadsheets, are in the Douce Collection at Oxford, vol. iv. pp. 18, 19. A copy, also, in J. H. Dixon’s Bds. and Sgs. of the Peasantry, Percy Soc., 1845, vol. xvii. (and in R. B.’s Annotated Ed. B. P., p. 138.)

There is still another “Arthur o’ Bradley,” but not much can, or need, be said in its favour; except that it contains only three verses. Yet even these are more than two which can be spared. Its only tolerable lines are borrowed from the Roxburghe Ballad. It is the nadir of Bradleyism, and has not even a title, beyond the burden “O rare Arthur o’ Bradley, O!” Let us, briefly, be in at the death: although Arthur makes not a Swan-like end, with the help of his Catnach poet. It begins thus:

Even Ophelia could not ask, after Arthur sinking so low, “And will he not come again?”

J. W. E.

September, 1875.

[So far as possible, to give completeness to our Reprint of Westminster Drollery of 1671-2, and Merry Drollery, Compleat, 1670-1691, we now add the Extra Songs belonging to the former work, edition 1674; and to the latter, in its earlier edition, 1661: with their respective title-pages.]

Westminster-Drollery.

Or, A Choice

COLLECTION

of the Newest

SONGS & POEMS

BOTH AT

Court and Theaters.

BY

A Person of Quality.

The third Edition, with many more

Additions.

LONDON,

Printed for H. Brome, at the Gun in St. Paul’s

Church Yard, near the West End.

MDCLXXIV.

[p. 111.]

[p. 113.]

[p. 114.]

[p. 120.]

[Here ends the 1674 edition; for account of which, and the 1661 Merry Drollery, see our present Appendix, Parts Third and Fourth.]

MERRY

DROLLERY,

OR,

A COLLECTION

| Of | { Jovial Poems, |

| { Merry Songs, | |

| { Witty Drolleries. |

Intermixed with Pleasant

Catches.

The First Part.

Collected by

W.N. C.B. R.S. J.G.

Lovers of Wit.

[1s. 3d.]

LONDON,

Printed by J. W. for P. H. and are to

be Sold at the New Exchange, Westminster-Hall,

Fleet Street, and Pauls

Church-Yard. [May

1661.]

[fol. 2.]

[page 11.]

[p. 14.]

[p. 27.]

[p. 32.]

[p. 56.]

[p. 64.]

[p. 85.]

[p. 88.]

[p. 95.]

[p. 134.]

[Some of these verses are evidently misplaced: We keep them unchanged, but add side-notes to rectify.]

[A song follows, beginning “There were three birds that built very low.” With other four, commencing respectively on pp. 146, 153, 161, and 168, it is degraded from position here; for substantial reasons; and (with a few others, afterwards to be specified,) given separately. Nothing but the absolute necessity of making this a genuine Antiquarian Reprint, worthy of the confidence of all mature students of our Early Literature, compels the Editor to admit such prurient and imbecile pieces at all. They are tokens of a debased taste that would be inconceivable, did we not remember that, not more than twenty years ago, crowds of MP.s, Lawyers, and Baronets listened with applause, and encored tumultuously, songs far more objectionable than these (if possible) in London Music Halls, and Supper Rooms. Those who recollect what R...s sang (such as “The Lock of Hair,” “My name it is Sam Hall, Chimbley Sweep,” &c.), and what “Judge N——” said at his Jury Court, need not be astonished at anything which was sung or written in the days of the Commonwealth and at the Restoration. A few words we suppress into dots in Supplement, &c.]

[p. 148.]

[Part First, 1661, ends on pages 171-175, with The new Medley of the Country man, Citizen, and Souldier (which in the 1670 and 1691 editions are on pp. 182-187). The 1661 edition of Second Part has a complete title-page of its own, in black and red, exactly agreeing with its own First Part, except that the words are prefixed “The || Second Part || of.” A contemporary MS. note in Ant. à Wood’s copy, says, of each part, “1s. 3d.” as the original price. There is also, in the 1661 edition (and in that only), another address, here, which runs as follows:—

“To the Reader:

“Courteous Reader,

“We do here present thee with the Second part of Merry Drollery, not doubting but it will find good Reception with the more Ingenious; The deficiency of this shall be supplied in a third, when time shall serve: In the mean time

Farewel.”

The Third Part, mentioned above, never appeared.

The woodcut Initial W represents Salome, the daughter of Herodias, receiving from the Roman-like Stratiotes the head of John the Baptist (whose body lies at their feet), she holding her charger. The Editor hopes to engrave it for the Introduction to this present volume.

The pagination commences afresh in the 1661 Second Part; but continues in the 1670, and the 1691 editions.]

[Part 2nd., p. 21.]

[p. 22.]

[p. 29.]

[p. 31.]

[p. 32.]

[A Droll of a Louse (p. 33.), seven verses of seven lines each, beginning “Discoveries of late have been made by adventures,” is reserved. Vide ante p. 230.]

[p. 38.]

[Following the above comes a group of more than usually objectionable Songs, viz., John and Joan, beginning “If you will give ear” (p. 46); “Full forty times over I have strived to win,” same title (p. 61); The Answer to it, “He is a fond Lover that doateth on scorn” (p. 62); Love’s Tenement, “If any one do want a house” (p. 64); and A New Year’s Gift, “Fair Lady, for your New Year’s Gift” (p. 81). These are all reserved for the Chamber of Horrors. Vide ante, p. 230.]

[p. 103.]

[p. 106.]

[Followed, in 1661 edition by “Now that the Spring,” &c., and the three other pieces which are to be found in succession, already printed in our Merry Drollery, Compleat of 1670, 1691, pp. 296-301: The last of these being the Song, “She lay all naked in her bed.” This begins on p. 115, of Part 2nd, 1661; p. 300, 1691. In the former edition it is followed by “The Answer,” beginning “She lay up to,” &c., which, like other extremely objectionable pieces, is kept apart. Next follow, in 1661 edition, The Louse, and the Concealment.]

[p. 149.]

[As already mentioned, this is followed, in the 1661 Part Second, page 151, by The Concealment, beginning “I loved a maid, she loved not me,” which is the last of the songs or poems peculiar to that edition. See the end of our Supplement: so paged that it may be either omitted or included, leaving no hiatus. We add, after the Supplement, the title-page of the 1670 edition of Merry Drollery, Compleat; when reissued in 1691, the same sheets held the fresh title-page prefixed, such as we gave in second Volume. Readers now possess the entire work, all three editions, comprehended in our Reprint: which is the Fourth Edition, but the first Annotated. J. W. E.]

Appendix.

(NOW FIRST ADDED.)

Arranged in Four Parts:—

1.—Choyce Drollery, 1656.

2.—Antidote against Melancholy, 1661.

3.—Westminster-Drollery, 1674.

4.—Merry Drollery, 1661; and Additional Notes to 1670-1691 editions: with Index.

Readers, who have accompanied the Editor both in text and comment throughout these three volumes of Reprints from the Drolleries of the Restoration, can scarcely have failed to see that he has desired to present the work for their study with such advantages as lay within his reach. Certainly, he never could have desired to assist in bringing these rare volumes into the hands of a fresh generation, if he believed not that their few faults were far outweighed by their merits; and that much may be learnt from both of these. Every antiquary is well aware that during the troubled days of the Civil War, and for the remaining years of the seventeenth century,[260] books were printed with such an abundance of typographical errors that a pure text of any author cannot easily be recovered. In the case of all unlicensed publications, such as anonymous pamphlets, facetiæ, broad-sheet Ballads, and the more portable Drolleries, these imperfections were innumerable. Dropt lines and omitted verses, corrupt readings and perversions of meaning, sometimes amounting to a total destruction of intelligibility, might drive an Editor to despair.

In regard to the Drolleries-literature, especially, if we remember, as we ought to do, the difficulties and dangers attendant on the printing of these political squibs and pasquinades, we shall be less inclined to rail at the original collector, or “author,” and printers. If we ourselves, as Editor, do our best to examine such other printed books and manuscripts of the time, as may assist in restoring what for awhile was corrupted or lost from the text (keeping these corrections and additions clearly distinguished, within square brackets, or in Appendix Notes to each successive volume), we shall find ourselves more usefully employed than in flinging stones at the Cavaliers of the Restoration, because they left behind them many a doubtful reading or an empty flaggon.

We have given back, to all who desire to study these invaluable records of a memorable time, four complete[261] unmutilated works (except twenty-seven necessarily dotted words): and we could gladly have furnished additional information regarding each and all of these, if further delay or increased bulk had not been equally inexpedient.

1.—In Choyce Drollery, 1656, are seen such fugitive pieces of poetry as belong chiefly to the reign of Charles 1st., and to the eight years after he had been judicially murdered.

2.—In Merry Drollery, 1661, and in the Antidote against Melancholy of the same date, we receive an abundant supply of such Cavalier songs, ballads, lampoons or pasquinades, social and political, as may serve to bring before us a clear knowledge of what was being thought, said, and done during the first year of the Restoration; and, indeed, a reflection of much that had gone recently before, as a preparation for it.

3.—In such additional matter as came to view in the Merry Drollery, Compleat, of 1670 (N.B., precisely the same work as what we have reprinted, from the 1691 edition, in our second volume); and still more in the delightful Westminster-Drolleries of 1671, 1672, and 1674, we enjoy the humours of the Cavaliers at a later date: Songs from theatres as well as those in favour at Court, and more than a few choice pastorals and ditties of much earlier date, lend variety to the collection.

We could easily have added another volume; but enough has surely been done in this series to show how rich are the materials. Let us increase the value of all, before entering in detail on our third series of Appendix Notes, by giving entirely the deeply-interesting Address to the Reader, written and published in 1656 (exactly contemporary with our Choyce Drollery), by Abraham Wright, for his rare collection of University Poems, known as “Parnassus Biceps.”

It is “An Epistle in the behalfe of those now doubly-secluded and sequestered Members, by one who himselfe is none.”

[Sheet sig. A 2.]

“To the Ingenuous

READER.

SIR,