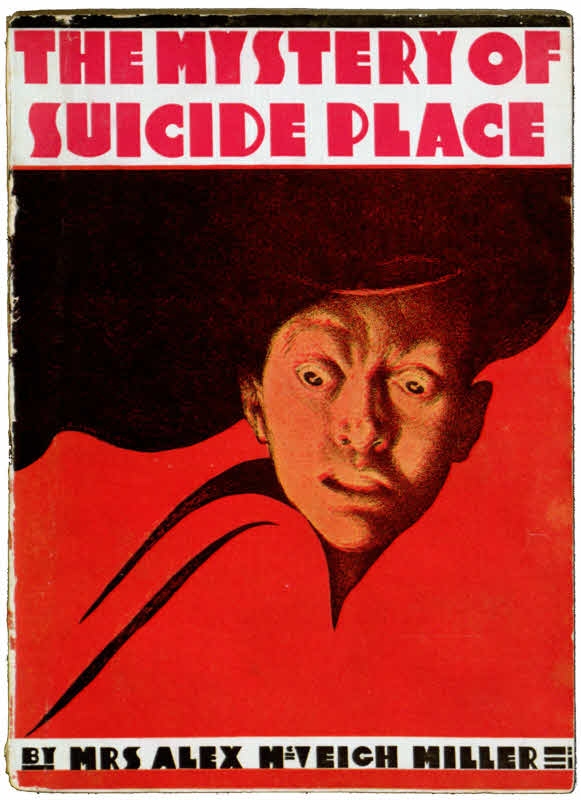

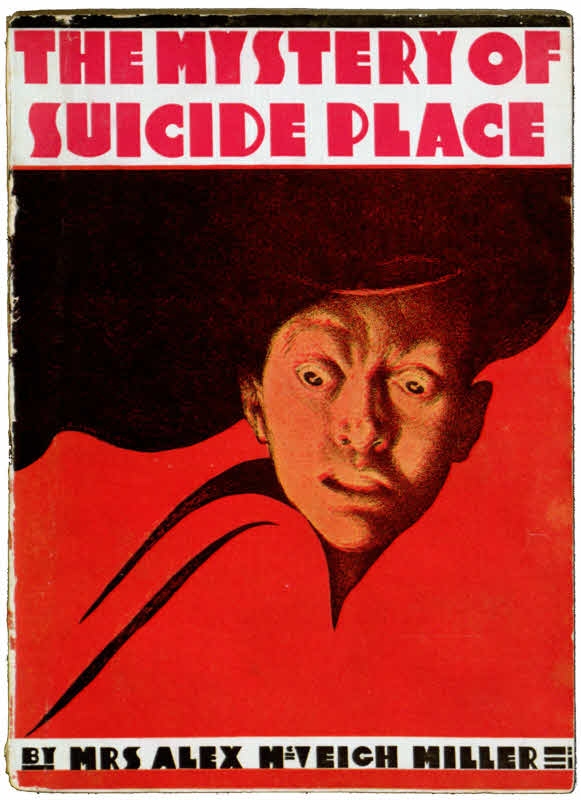

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mystery of Suicide Place, by Mrs. Alex. McVeigh Miller This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Mystery of Suicide Place Author: Mrs. Alex. McVeigh Miller Release Date: October 7, 2019 [EBook #60451] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MYSTERY OF SUICIDE PLACE *** Produced by Demian Katz, Craig Kirkwood, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University (http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

By

Mrs. Alex McVeigh Miller

HART SERIES No. 40

(Printed in the United States of America)

PUBLISHED BY

THE ARTHUR WESTBROOK COMPANY

Cleveland, U. S. A.

| PAGE. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| “If Only——” | 5 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| “Heiress of Fate” | 8 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| A Dastardly Plot | 13 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Why Did She Do It? | 16 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Reason Why | 23 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| A Dream of Roses | 29 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| At the Dread Hour of Midnight | 34 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| “From That Spot by Horror Haunted” | 40 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| “Oh! Those Happy Moments Spent Together!” | 44 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| “Sleeping, I Dreamed, Love!” | 49 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Plighted | 52 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| “When I Am Married!” Cried Floy | 55 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| In the Meshes of Her Hungry Fate | 57 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Thrown on the World | 63 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| “As Proud and as Pretty as a Princess” | 66 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| A Cruel Persecution | 71 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The Fair Dead Face He Had Loved So Well | 75 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| “Cupid” | 79 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| The Beresford Pride | 82 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Alva’s Disappointment | 88 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| “Where is She Now?” | 92 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| “Oh, My Son, My Son!” | 95 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| “You Wicked, Wicked Girl!” Cried the Midnight Visitor | 102 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| “A Royal Road to Fortune” | 106 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| How Those Tender Letters to Another Must Have Stabbed Maybelle’s Heart! | 110 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| “I Will Sell My Life and Honor Dearly!” Cried the Maddened Girl | 116 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| At Bay | 119 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Another Intruder | 122 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| “Oh, How Blest I Am!” Cried Floy | 125 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| “’Tis Home Where’er the Heart Is” | 128 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Near to Death | 134 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| “The Silence of a Broken Heart” | 137 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Pride Brought Low | 140 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Too Late! | 142 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| “He is Fickle and False—My Lover Whom I Trusted So Fondly!—How Can I Bear This Pain and Live?” | 146 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| “Not Till Love Comes” | 152 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| Searching in Vain | 155 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| A Bower of Roses | 158 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| A Little Hand | 161 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| A Startling Revelation | 163 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| Joy and Sorrow | 166 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| A Young Girl’s Pride | 170 |

| CHAPTER XLIII. | |

| Maybelle Writes a Letter | 173 |

| CHAPTER XLIV. | |

| But One Chance in a Hundred | 180 |

| CHAPTER XLV. | |

| “Hope Deferred Maketh the Heart Sick” | 184 |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | |

| “The House is Haunted” | 188 |

| CHAPTER XLVII. | |

| “Life Is So Sad!” Cried Floy | 192 |

| CHAPTER XLVIII. | |

| A Strange Romance | 198 |

| CHAPTER XLIX. | |

| “Something Terrible!” | 203 |

| CHAPTER L. | |

| The Last Victim | 209 |

| CHAPTER LI. | |

| “Just One Kiss!” | 212 |

| CHAPTER LII. | |

| All That Floy Had Longed for in Other Days Was Hers Now—Lucky Little Mortal! | 217 |

[5]

THE MYSTERY

of

SUICIDE PLACE

When the beautiful Miss Maybelle Maury, of Mount Vernon, New York, was returning in October, 1894, from her tour of Europe with her chaperon, Mrs. Vere de Vere, a New York society leader, she was introduced by the latter to our hero, handsome young St. George Beresford, the only son of a New York millionaire.

Life on shipboard offers many temptations to flirtation, and the fascinating youth did not show himself indifferent to the challenge that Maybelle’s dark, languishing eyes immediately flashed into his face. He attached himself to her party, and made lazy, languid love to the beauty all the way over.

The chaperon was delighted, and plumed herself not a little on the probable grand match she had brought about for her favorite Maybelle. She knew that the girl’s[6] mother, her own distant relative, would be overjoyed at this lucky turn of Fortune’s wheel. Maybelle was nineteen, and it was time she was making her matrimonial market, because she had two younger sisters at school who must come out in a year or two more, and it would be so expensive having three girls in society at once, for the father, though a prosperous New York merchant, could not be rated among the millionaires.

Our space, however, will not permit us to follow the progress of Maybelle’s flirtation through those bright October days upon the sea.

But when the twain parted in New York, St. George Beresford was invited to visit the beauty at her home in Mount Vernon, close to the great metropolis, and carelessly promised to go “some day.”

It was a shame that the handsome rogue forgot all about it afterward, so that they did not meet again until the winter, when Maybelle was spending a month in the height of the season with her New York friend, Mrs. Vere de Vere.

Her dark eyes flashed with pleasure as they clasped hands again after those months of separation, and she cried reproachfully:

“You forgot your promise!”

The laughing brown eyes grew soft with repentance as he returned, coaxingly:

“Indeed, I meant to come to Mount Vernon, but—I went South the first of November with my folks, and didn’t return until—well, recently. So now—will you forgive me?”

Would she not forgive the deceitful wretch anything, charming Maybelle, who secretly adored him? She knew[7] that he had only remained South five weeks, but she flashed him a melting glance, and murmured, sweetly:

“I’ll forgive you, sir, on only one condition—that you come in the early spring.”

“Only too glad to promise—so good of you to permit me,” cooed the jeunesse dorée; and so the flirtation was resumed, although not very spiritedly on his part. He was five-and-twenty, and several years in the social swim had made him shy of pretty anglers for rich catches.

They met at balls, operas, and receptions—they drove together a few times, he made several short calls, and sent her flowers and books, but his frank nonchalance through it all was not encouraging. It was froth on a light wave, and even the keen attention of Mrs. Vere de Vere could detect no latent earnestness.

“He does not seem to mean anything in particular,” she confided candidly to the girl on the last day of her stay; and Maybelle laughed and answered that she did not care—she had only been flirting with him.

But that night her pillow was wet with tears because of his careless farewell when he heard she was going.

But she could not banish his image from her warm heart. Her love, as well as her pride, was enlisted, and a little spark of hope kept alive in her heart the longing that he would keep his promise to come in the spring.

But it is more than probable that he would have audaciously forgotten again, only her brother Otho sought his acquaintance and attached himself to him, with the result that he “bagged the game”—that is, he brought St. George Beresford to Mount Vernon in May, when the handsome home on Prospect Avenue, Chester Hill, was looking its best among its trees and flowers.

Oh, how shyly happy Maybelle was at his coming! The[8] love in her heart made her dusky beauty more dazzling than ever before. Joy lent a deeper, fuller cadence to her musical voice. Hope shone again like a brilliant star in her languishing dark eyes, with their heavy, black-fringed lashes.

St. George Beresford suddenly found her winning on him in a subtle fashion and told himself that really she was growing more charming with each day and hour. This tenderness and admiration might have ripened into passion for Maybelle, if only——

Ah! those words, if only—so short, so simple, yet so fraught with meaning!

Maybelle might have won Beresford’s heart and become his bride, if only he had not seen, as he lounged at the gate with Otho Maury, one May morning, that vision of a blue-eyed, golden-haired, cherry-lipped, dimpled-faced girl in dark blue flashing past the gate on a shining wheel, leaving in his heart a memory of the sweetest, sauciest, most adorable young face in the world.

“Who is she?” he asked, hoarsely, of Otho; who replied, carelessly:

“Miss Florence Fane, the carpenter’s daughter, nicknamed Fly-away Floy, by reason of her hoidenish ways and never did a girl deserve the title more.”

It was that lovely face, dear reader, that brought the elements of tragedy into my story.

Otho Maury’s tone was light and contemptuous, but at heart he was furious. He had a penchant for Florence Fane himself, and dreaded a rival in this man whose[9] face had paled at the sight of her, and whose voice had trembled as he asked her name—ay, whose very heart shone in his splendid eyes as he leaned over the gate watching the flying wheel and its graceful rider like one in a dream—a dream of love, for his pulse beat fast, his heart leaped wildly, his very soul was stirred within him in strange, delirious ecstasy.

Maybelle came down the graveled walk to them, beautiful in a dainty white gown with purple lilacs at her slender waist.

But St. George Beresford did not turn to meet her gaze, and Otho said, sneeringly:

“Beresford has been struck dumb by the sight of a beauty on a bicycle.”

“A beauty?” frowningly.

“Yes. Little Fly-away Floy.”

“Nonsense, she is no beauty, only a mischievous little hoiden! Don’t let her turn your head, Mr. Beresford; she isn’t in our set at all. Her father is a mechanic, and her mother a seamstress.”

“Ah!” he exclaimed, carelessly, turning around and flashing her a bright, quizzical glance, in which he seemed to dismiss the thought of Florence Fane.

He was very proud, and did not wish her to know that he had been fascinated by one so far below him in social position.

But Maybelle had equivocated, and she hoped ardently that he would not find it out.

A flavor of romance and mystery hung around Florence Fane’s origin.

John Banks, the kind-hearted carpenter, had taken the sobbing child nine years ago from the side of her dead mother and carried her home to his childless wife, who,[10] because Floy seemed to have no kith or kin, had taken her into her heart and called her daughter, and both lavished a world of tenderness on the seven-year-old child. But save in nobility of nature and a tender heart, she was no more like the homely pair than a restless humming-bird is like a toiling honey-bee. She was rarely, exquisitely beautiful, lovable after an imperious fashion, but willful and untamable in disposition, the result of spoiling by a too fond and overindulgent mother, who at the last had deserted her by fleeing from life’s pains and penalties by the forbidden path of suicide.

Floy was heiress by her birth to a small estate and to a terrible taint of blood—the mania for suicide.

She was a descendant of the Nellest family, that for forty years had numbered in each decade a suicide among its members.

The scene of these tragedies was at an old farm-house on a lonely road two miles from Mount Vernon.

The house, a substantial and somewhat pretentious structure of rough dark stone, overgrown picturesquely in many places with creeping ivy, stood back from the road in a magnificent grove of old oak-trees, and twenty-five acres of rich farming land stretched away in the rear.

But so grewsome was the reputation of the place, that for nine years it had had no tenants, and its name had changed, by tacit consent of the neighborhood, from Nellest Farm to Suicide Place.

The Nellest family had owned and tilled this farm almost a hundred years, but in the middle of the century the head of the family had committed suicide by cutting his throat, and just ten years later, his only son was found hanging from a tree near the spot where his father died.

[11]

The widow of the son, with her only daughter, continued to reside at the farm, employing a competent man to manage it. But when another decade rolled around, the neighborhood was horrified to learn that the manager had shot himself in the head, adding the third to the list of deaths by suicidal mania.

Horrified and unnerved by all these tragedies, Widow Nellest fled from the place with her beautiful young daughter, leaving the property in the hands of a lawyer for rent or sale.

But neither buyer nor tenant could be found, and successive crops of weeds ripened and died on the untilled acres. The poorest beggar would have refused to live there rent-free.

At almost the end of the next decade the daughter of Widow Nellest returned to the place in widow’s weeds, and with a child seven years old. Her mother had died of a broken heart, she said, and she herself had been married and widowed.

In spite of the horror of the neighborhood, she took up her abode at Suicide Place, declaring herself poor and unable to make a home elsewhere. Here she lived alone with her child, as neither man-servant nor maid-servant would have gone inside the gates for love or money.

And here, after a few months’ solitude, Mrs. Fane, overcome by the terrible, mysterious spirit of the old place, succumbed to the mania of her family and poisoned herself.

John Banks, who had been employed by the woman to mend her gates, heard the frightened shrieks of little Floy one morning when he came to his work, and most reluctantly entered the house.

He found Mrs. Fane dead, with a bottle of poison[12] clutched in her stiffened hand. She had been dead for hours.

The carpenter took the orphan child to his own home, and into his big, generous heart. Then he reported the case, after which there was a coroner’s inquest and a verdict of suicide by poison.

Enough money was found in the house to bury her decently, and then the old place was left to its grim solitude again.

This was Florence Fane’s inheritance—the old farm that none would rent or buy, and the terrible taint of blood that made her an object of a romantic interest and pity to the many who knew what must be her probable fate.

But, strange to say, the child herself knew and laughed at these whisperings. She had no superstition in her make-up; and, although forbidden by her adopted parents to enter even the gates, she was in the habit of going secretly to the old house and rambling through it at will. She even declared that she would go and live there, if any one would bear her company; but no one accepted her defiant challenge to fate.

Meanwhile, the time was approaching when the grim, unappeasable Moloch of the place would demand, in all probability, its fifth victim. It was shunned like the plague, for all remembered that not only the family, but one of no kith or kin, had met self-sought death there. None but Floy ventured near the place—willful Floy, who laughed to scorn their predictions that she would be the next sacrifice. When they tried to reason with her, she would not listen to their warnings, darting away like a gay, elusive little humming-bird.

When St. George Beresford turned away from the[13] gate where he had watched Fly-away Floy out of sight, he knew that his heart had gone with her forever, and that he never had, and never could love Maybelle Maury as she wished to have him do—for he had long since fathomed the tender secret of her heart. The knowledge made him feel very pitiful toward the poor girl, and rendered him so abstracted that she guessed the change in him directly, and became furiously jealous of her unconscious rival, merry little Floy.

He tried to smile and chat as usual with Maybelle and Otho, but his thoughts wandered from them in spite of himself.

Oh, how strange it was—how strange! Only a careless glance from a pair of blue eyes, as the girl had smiled and nodded at Otho Maury, and all the world had changed for St. George Beresford. He wondered vaguely if his glance had made any impression on the girl’s heart.

The first moment that Maybelle was alone with Otho she clung to his arm, whispering, sorrowfully:

“Otho, I am wretched! Did you mean what you said this morning—that St. George admired that girl?”

“Yes, I meant it, every word, Maybelle, for it is true, curse the luck! and unless we carry things with a high hand, he is lost to you forever. In fact, I never saw a fellow so hard hit in all my life. He actually turned white to the lips with emotion, and his voice was hoarse and strange as he demanded her name; and, of course, you noticed how distrait and half-hearted he has been all day?”

[14]

“Yes, I saw it too plainly; but, oh, I can not give him up! Oh, surely, he would not stoop to her—so far beneath him socially! Besides, she isn’t so pretty, either—only with a babyish kind of beauty.”

“Not so pretty, Maybelle! Why, now you make a fatal mistake, underrating the girl’s charms. Half the fellows are raving over her style; and she could have a dozen proposals to-morrow, only she laughs them to scorn, the saucy little darling!”

“You are very enthusiastic, Otho!” she cried, suspiciously. “Perhaps you are in love with her yourself. I wish you would marry her to-morrow, and make it impossible for her to become my rival.”

He flushed, then laughed, answering, coolly:

“Thank you; but the plan isn’t feasible. I shouldn’t mind making love to the pretty little thing, for she’s sweet enough to turn any man’s head; but I intend, like yourself, to marry money when I sacrifice myself on Hymen’s altar.”

“Oh, brother, I am wretched, wretched! It isn’t alone for the money I want him. I have had other offers—rich ones, too; but I love him, love him, love him! I must win him or die! All in a minute I feel desperately wicked, and willing to do anything to win him for my own. I hate that girl already, and wish her dead! Why does she not go and kill herself like her mother?”

“Probably she will in the end; but she isn’t unhappy enough yet.”

“Then let us do something to drive her mad with despair at once!” cried Maybelle, feverishly, recklessly, her dark eyes flashing with a tigerish light not good to see.

Otho’s eyes flashed back the same spirit, for his heart[15] was burning with a cruel passion for bonny Floy. Stooping close to her ear, he whispered, hoarsely:

“Suppose I could drive her mad with love for me?”

“Try it, Otho, try it! Begin at once, please!” she responded, eagerly, hopefully.

“I will, for I fancy she admires me immensely already by her blushes when I speak to her, and I’ll follow up the good impression at once, storm the castle of her fancy, as it were, with ardent love-making, persuade her to elope with me, perhaps—oh, a mock marriage, of course! She is poor, and so she could not be taken au serieux.”

She listened without a protest to his diabolical scheme for wrecking the life of a pure and lovely girl. Oh, a jealous woman can be so hard and pitiless!

He continued:

“Of course you know she will be at the picnic we attend to-morrow?”

“No! Who dared invite the creature?” imperiously.

“Pshaw! Maybelle, that scorn was well acted before Beresford to-day; but in private we know that the girl really has some rights and a sort of footing in our set, so that we’re apt to meet her at less exclusive functions, such as this picnic will be. We can not keep from meeting her to-morrow, but we can forestall Beresford’s suit by plotting beforehand.”

“Tell me how, Otho, and be sure I will act my part.”

“I am sure you will; but I must first think it over, and in the morning I will confide my plans to you before we start for the picnic. And I’ll call at the carpenter’s cottage this evening. She is always on the porch with her guitar. I’ll get in her good graces so that I can monopolize her company to-morrow, and make him think he has no show with her at all. I’ll throw in some little fibs,[16] too, that he’s engaged to you, etc., so that she will shun him.”

“Yes, Otho, I see. That is a splendid idea, and easy to carry out. Oh, how I thank you for your clever help all through!” she cried, in a transport of joy and gratitude.

Otho accepted the praise complacently, but he knew he was working more for himself than for her.

It would be a most delightful part to play, the making love to Floy, and as for the rest, he was heart and soul in the scheme to win a millionaire for his brother-in-law. He was selfish and extravagant, and always in hot water with his father about money, so when Maybelle secured her prize he would make her pay a heavy price for his help.

The next morning dawned gloriously, and in due time the carriages reached the picnic-grounds—just a mile past Suicide Place—a picturesque grove on the banks of a river. There was a pavilion and music for dancing, with every device for pleasure.

And Floy was there with the rest, charming in a white duck suit and big hat, self-possessed as a young princess, and not one whit abashed when Otho led her to his party, and said, graciously:

“You know my sister Maybelle, don’t you? She has been away a great deal lately, but she remembers little Fly-away Floy, and this is my friend, Mr. St. George Beresford.”

They all bowed graciously, and then the quartet sat[17] down together on the river-bank, for all this condescension was the plot that wicked Otho had unfolded to his sister that morning. Other couples joined them, while some danced in the pavilion, and still others swung in the hammocks under the shady trees.

They talked lightly and desultory on frothy subjects, as people at picnics usually do, and barely any one but Beresford remembered afterward that it was Otho Maury who started the subject of bravery and courage, and contrasted the difference in man and woman on these qualities of mind and strength. He exclaimed, finally:

“I adore courage and bravery in man or woman. Indeed, I would not marry a girl who was a coward—who ran shrieking from a mouse, or trembled at the thought of a burglar—but I could worship a fearless girl; such a one, for instance, as would dare to spend a night alone in a haunted house.”

The pretty girls who heard him all shrieked and shuddered with dismay—all except Floy, who shrugged her pretty shoulders, and said, vivaciously:

“Pshaw! that is not any great thing to do. I shouldn’t be afraid to stay in a haunted house all night.”

“Aren’t you afraid of ghosts, like most young girls?” asked Otho, incredulously.

“No, I’m not afraid, for I don’t believe in spirits.”

Maybelle laughed tauntingly.

“You are joking, Floy. You wouldn’t dare stay alone all night in Suicide House—now, would you?”

The girls all applauded Maybelle, sneering at Floy’s pretense of bravery, until the impulsive girl saw that they were overtly challenging her to a proof of her courage.

Flushing with anger, her blue eyes blazing with defiance, she cried, stormily:

[18]

“I am not a coward, Maybelle Maury, and I am not afraid of anything, ghost or human; and I will prove it to you all by staying alone at Suicide House to-night!”

“No, no; you must not!” cried a few voices, frightened at the thought of what she had been goaded to do.

But Floy’s high spirit was up in arms, and she would not be dissuaded from her purpose.

“I shall surely do it, and no one shall prevent me!” she cried; adding: “When we go home to-night, you may leave me at Suicide Place, and I will lock myself in, for I have the keys with me now, and you can go by and tell auntie I stayed all night with one of the girls. In the morning you may send a committee to escort me home in triumph. Why do you all look so pale and frightened? There is no danger, I tell you; I’ve been over the house a hundred times alone, and the only ghosts are rats. It will be rare fun staying there all night!”

No one could dissuade her, so they gave up trying. Everybody was sorry for it, but Otho and his sister, who exchanged furtive looks of satisfaction.

St. George Beresford had not spoken a word during the whole conversation, though his eager, admiring eyes had scarcely left Floy’s lovely flower-like face. He was silent, abstracted, bitterly piqued at Floy’s pronounced indifference to himself.

She had not seemed to see him since the first glance in which she had acknowledged their introduction by Otho Maury, and of course he could not know that it was because Otho had said to her at the cottage gate last night:

“My sister Maybelle will be at the picnic to-morrow with her handsome betrothed—the rich New Yorker she is to marry this fall. She is as jealous of him as a little[19] Turk, and it makes her angry for any other girl to even look at him.”

He had counted rightly on Floy’s high sense of honor.

She was a mischievous little madcap, but she respected Maybelle’s rights, and feigned indifference to Beresford, although she could not avoid noticing the ardent glance he threw in her direction, and she thought, indignantly:

“No wonder Maybelle is jealous, for I can see already that he’s a wretched flirt. I won’t even look at him, though he is awfully, awfully handsome!”

So with a sigh, whose subtle meaning she could not understand, she turned her back on the wretched Beresford, and entered readily into an animated conversation with Otho, maddening her silent admirer with such keen jealousy that he could bear it no longer.

“Let us go and dance,” he said to Maybelle, hoarsely.

“Oh, I’m too lazy to move. Go and find another partner,” she laughed.

“But I’m not acquainted with any of the girls here.”

“Otho, go along and introduce him to some girls, and I’ll stay with Floy and tell her about my lovely trip to Europe last year.”

Beresford, disappointed in a faint hope that she might have proffered Floy to him as a partner, went away with Otho, and Maybelle made herself agreeable to her companion.

At last she observed, patronizingly:

“You’ve never been anywhere, have you, Floy?”

“Not since mamma brought me a little girl back to the farm,” Floy answered, flushing sensitively, for she felt the sting in Maybelle’s patronizing tone.

But the latter continued, gently and purringly:

“It’s too bad your having to stay with those poor, hard-working[20] people, isn’t it? Shouldn’t you like to support yourself, Floy?”

“I should not know how to earn a penny,” murmured Floy, who was like the naughty Brier-Rose of the poem:

“Suppose I tell you what papa was saying about you last night?” continued Maybelle.

“Yes,” Floy answered, helplessly.

“He was saying that he needed two new salesgirls in his big dry-goods store in New York, and he wondered if any girls in Mount Vernon would like to go. He said he had thought of you, and that maybe old John Banks would be glad to have you find a situation and help earn your own living.”

Floy reddened, paled, then gasped:

“I don’t believe Uncle John would like it at all. He loves me—he and auntie—and he doesn’t mind taking care of me.”

“But you’ll tell him of this offer, won’t you, dear, and you’ll think of it yourself? Papa says he’ll keep the place open a week for you,” said Maybelle, who had suggested the plan to Mr. Maury herself.

“I’ll tell Uncle John,” promised Floy; but she seemed tongue-tied after that, and went moodily away from Maybelle’s vicinity to join some other girls, keeping so resolutely[21] away that they did not meet again until that afternoon, when most of the dancers were resting after dinner on the banks of the beautiful river.

At heart Floy was cruelly wounded by Maybelle’s patronizing, but she was too proud to show her pain. Once St. George Beresford ventured to seek her for a partner in the dance, but she refused so curtly that he turned away indignantly, wondering why she was so cold to him while so kind to others.

“She has plenty of smiles for that shallow Otho. I’d like to wring his little black neck!” he thought, angrily.

Otho was a cur, indeed, but he was slight and dark and elegant—one of those types that very young girls rave over. Beresford saw that he stood high in Floy’s good graces, and began to hate him accordingly.

When the couples paired off on the river-bank beneath the shady trees, there was Maybelle and Beresford, and next to them Floy and Otho.

Floy was bright and restless, feeling Beresford’s gaze ever seeking hers, and wondering why it thrilled her so when she knew it was not right for him to look at any other than Maybelle, his beautiful, dark-eyed betrothed.

She turned her back on him rather rudely, and exclaimed to Otho:

“People are very foolish and superstitious. They are always going on about Suicide Place, and saying that it must claim another victim soon; and they are even hinting that I will be the doomed one.”

“That is nonsense. I am sure you are too strong-minded to yield to such a temptation,” Otho replied, reassuringly.

St. George could not help listening to the sound of the[22] musical voice and watching the beautiful profile when it turned toward him in her animated talk.

Heavens, how lovely she was! What eyes, what lips, what dimples, what a mesh of curly, golden hair in which to entangle a man’s throbbing heart! And yet it was not simply her beauty that inthralled him, and he knew it. She had that psychical charm we call personal magnetism, that is like the perfume to the flower and seems to endow it with a soul.

He heard her continue, almost defiantly, as if annoyed:

“I wish they would not talk about it, for it makes me angry. Why should I kill myself? I’m young and gay, and, in a way, happy! And yet,” musingly, “I suppose, after all, that the terrible taint of that mania is in my blood. I am not superstitious, but perhaps it may conquer me after all, who knows? Do you suppose I shall ever kill myself?”

“I hope not. You would break a dozen hearts if you did, mine among the rest,” Otho replied, banteringly, with a killing glance.

She continued, meditatively:

“They will go on expecting me to commit suicide, of course, and always selecting the old farm as the scene of the fifth tragedy. Why should I not choose some other scene for the final act? This river, say,” pointing to it as it rippled below the bank, dark and deep and dangerous in its beauty.

Laughing, she rose to her feet, and he said:

“It seems that fate always demands the sacrifice within the gates of the grim old place.”

“Do you think so? Well, I shall defy the fate to which I was born, and break the charm of Suicide Place. If, following the taint in my blood, I must indeed kill[23] myself, I shall disappoint everybody in the location. It shall not be at the old farm, but—here!”

Then all at once the startling tragedy happened.

Floy stepped to the edge of the bank with a strange, mocking laugh on her red lips, and, as if the terrible mania had seized on her suddenly, red-handed and implacable as fate itself, she threw up her arms above her beautiful head, and leaped into the river that divided hungrily to receive the girlish form, then closed again greedily over its prey.

Pretty Floy’s startling, unexpected, and terrible action produced the effect of a thunder-clap on the gay and thoughtless crowd of young people who witnessed it.

A moment of blank, awed silence ensued, then every one seemed to join in a cry of alarm and dismay as they pressed forward to the banks and watched the eddying circles of water over the deep and dangerous spot where that lovely form had disappeared from view.

They watched eagerly for the golden head to reappear.

Meanwhile, Otho Maury sat motionless gazing at the water, his face marble-white, but in his eyes, beneath their lowered lids, a strange and devilish gleam of joy, as he thought to himself:

“How deuced clever in the little girl to hasten the dénouement of her life like this! It saves Maybelle and me a world of trouble.”

As for Maybelle, when Floy sprung into the water, she uttered one loud, hysterical shriek, and clutched her companion with both hands, hiding her dark eyes against[24] his shoulder as though she could not bear the sight of the river.

But in an instant Beresford recovered from his trance of horror, and struggled to release himself and rise.

But Maybelle clung to him so wildly that he could not loosen her grasp without hurting the clinging white hands.

“Do not leave me—do not leave me, St. George! I am so frightened!” she wailed, beseechingly.

“Otho! Otho!” called Beresford, sternly; and as Maury looked around with a dazed expression, he added: “Come to your sister—I must save that girl!”

Otho did not stir from his position, pretending not to understand, and Maybelle tightened her frantic clutch until he saw that he must use gentle force to release himself.

“I beg your pardon, but in common humanity I must go,” he said, resolutely, and wrenched himself free, rushing forward, throwing off his coat and hat as he went. Then, amid ringing cheers, the big, handsome fellow plunged into the river.

Out of that crowd of perhaps fifty young men he was the only one that had volunteered to save the drowning girl, although half a score of them had pretended to adore her.

As Beresford sprung into the water, Floy’s little head suddenly appeared above it some distance away from where she had sunk. He struck out in that direction, shouting to her to be brave, that he would save her life.

But at the sound of his voice, the girl’s head suddenly sunk beneath the water again, as though she were determined to accomplish her purpose of suicide.

Our hero, swimming with strong and gallant strokes toward[25] the spot, made a bold dive down to the depths, but rose again without Floy.

Directly her head bobbed up again some distance off, but swimming quickly toward her, Beresford grasped her where she lay easily floating on the water, not having realized in his excitement that she had been swimming furtively under the water, leading him a race for the fun of the thing, for she was not in the least danger.

Grasping her tightly, he said in hoarse tones, broken with joyful emotion:

“Thank Heaven, I reached you before you sunk again! It was a terrible thing you attempted, but I shall save you in spite of yourself.”

Floy laughed softly, and answered in a meek little voice:

“Oh, I’m sorry now that I did it. I don’t believe I want to die after all!”

“That is right,” he cried, heartily. “Now, be calm, and I will take you safely to the shore. Put your hands on my shoulder easily, like this,” placing them. “Be cool, and don’t get frightened and clutch at me—above all, don’t clasp my neck, for the current is very deep and strong, and you must not impede my motions. Do you understand?”

“Oh, yes; and I’ll do as you say. I—I should have liked to hold you around the neck, but if you object to it so seriously, I won’t.”

Was there a tone of exquisite raillery in the girl’s voice? He looked suspiciously into her face, and saw veiled mischief in the clear blue eyes. She was not frightened—not in the least.

“Thank you,” he returned, coolly, but with a fast-beating heart. “I am sure the experience would be delightful;[26] and if you like to try it after we are safe on land, I shall be most happy.”

“I hate you!” pouted Floy, and letting her hands slip, sunk again below the surface.

Terribly alarmed, he dived and brought her safely to the surface once more, saying, sternly:

“Do not be so careless again, or you may lose your life.”

To his amazement, she laughed mockingly.

“Swim on and I’ll keep by your side. Don’t be alarmed over me, for I’ve been doing all this for a purpose. I can swim like a fish.”

And, to his wonder and chagrin, for he felt himself grow hot even in the cold water with the thought that he had suddenly been turned from a conquering hero into an object of ridicule, Fly-away Floy, the merry little madcap, swam along by his side as easily and gracefully as a beautiful mermaid, until they reached the bank, when he gave her his hand to assist her, and they came again upon terra firma, greeted by admiring cheers from the onlookers.

While they were in the water, Otho had hurried to Maybelle, and whispered, hoarsely:

“Why didn’t you hold him tighter, you little fool? If you could have kept him from going to her assistance a short time, she would have been drowned and out of your way.”

“I knew it, and I tried to keep him back, but he shook me off in a rage, and I—I’m sure he even swore at me under his breath,” whimpered Maybelle, despairingly.

“Very likely,” grumbled Otho; and then he turned from her to watch Beresford’s progress, and saw to his amazement the man and girl clambering up the bank.

[27]

In the silence that followed the rousing cheer of joy at their return, Floy turned to her dripping cavalier, saying demurely:

“I thank you from my heart, Mr. Beresford, for your noble attempt to save my life. I was not in any danger, it is true, for I can swim like a duck, but of course you did not know that, and you are just as truly a real hero as if your brave attempts had indeed saved me from a watery grave.”

There was a swelling murmur of surprise from all around her, and one little girl, bolder than the rest, came up and said:

“Why, Floy, didn’t you intend to drown yourself after all?”

Floy tossed back her wet curly mass of short ringlets, and returned merrily:

“Of course not, little goosie; why should I be so silly as to kill myself, I that am so young and happy? I only jumped in to frighten you all—yes, and to test the courage of a gentleman who told us only this morning how much he adored physical courage.”

Her accusing blue eyes turned on Otho Maury, and she said, with light, laughing scorn:

“I thought as you pretended to be so very, very fond of me, that you would risk your life to save mine, but you proved yourself a coward after all!”

He was livid with secret, sullen rage, but putting a bold face on the matter, he answered, carelessly:

“Oh, I knew it was only a trick, and that you could swim as well as anybody; so I didn’t choose to humor your fancy to have me jump in the water and ruin my new fifty-dollar suit, like my friend Beresford here, who, it’s plain to be seen, is as mad as a March hare at the way[28] he was fooled. Come, mon ami, shall I drive you into town for some dry clothes?”

“If you please,” returned Beresford, who was indeed bitterly chagrined at being made the butt of such a joke, and angrily conscious of cutting such a poor figure among them all in his drenched clothing. He picked up his hat and coat and went away with Otho, who returned alone within the hour, saying that Beresford was in the sulks and wouldn’t come back.

“And as for you, little mischief,” he said, banteringly, to Floy, who had been over to a house close by and borrowed a pretty suit, in which she reappeared as fresh as a rose—“as for you, the lordly Beresford will never forgive you for making him appear ridiculous by jumping into the river to rescue a girl who could swim as well as he could. He said he should have liked to shake you for a naughty, saucy little vixen.”

“Who cares?” returned Floy, gayly, not the least abashed by Mr. Beresford’s resentment.

When the picnic was over, Maybelle slyly reminded her of her promise about Suicide Place.

“Oh, yes, I’m going to spend the night there, certainly,” she replied; and left the carriage at the gates of the grim old house, in spite of the remonstrances of many of the party, who were really uneasy at the thought of such a daring adventure.

Floy would not listen to any of them; she answered them with careless, merry banter; and as the carriages rolled away, they saw her standing inside the gates, waving her little hand in farewell, her slender, white-robed figure clearly defined in the gloom of the falling twilight.

[29]

Merry little Floy went dancing like a sunbeam through the dark oak grove, and sat down to rest on the porch before she entered the house for her night’s vigil.

She rested there while the full moon rose over the tree-tops, silvering the scene with an unearthly light, and throwing fantastic leaf-shadows on the short green grass. It was like an enchanted palace, so calm, so quiet, undisturbed by any sound save the plaintive call of a whip-poor-will away off in the dim, silent woods.

She mused a little soberly on the events of the day.

“That big coward, Otho Maury, I was beginning to fancy myself in love with him, but—I despise him now!” curving a red, disdainful lip. “And how I fooled them all! They really thought I was attempting suicide! Ha, ha! But how splendid Maybelle’s fiancé was; how brave, how cool, and if only—he wasn’t engaged, I believe I should have lost my heart to him—so there!”

Perhaps she had lost her heart to him anyway, in spite of Maybelle, for she could not get the thought of the big, handsome, brown-eyed fellow out of her little curly head, and she recalled with a sudden warm wave of color rushing to her face the audacious frankness of the words he had said to her in the water, answering her saucy jest:

“I’m sure the experience would be delightful, and if you like to try it when we are safe on land, I shall be most happy.”

Floy had thrilled with sweet ecstasy at his daring words, and now she said, audaciously:

“Yes, I—I should like to try it! I should throw my arms around his big neck and hug him tight, and kiss his[30] sweet, brave lips, the beautiful hero, only——” and the words trailed off into a deep sigh at the sudden thought of Maybelle, who stood between them.

And like a dash of cold water came the memory of Otho’s words.

Beresford was angry with her for the joke she had played, and would like to shake her for a naughty, saucy little vixen.

“Let him try it—that’s all!” she exclaimed, shaking her bright head defiantly, then leaning it half despondently on her arm.

Wearied by the pleasures of the long, bright day, she sunk into slumber.

Sweet dreams came to her there in the fragrant gloom of the warm spring night.

To her fancy she was walking with St. George Beresford in a beautiful rose garden.

Overhead there leaned a sky all darkly, beautifully blue, while little fleecy clouds tempered the golden brightness of noon.

From afar there came to her the soft murmur of the sea blended with low, soft music divinely sweet and tender—the music of love.

All around her were the rarest roses filling the summer air with fragrance—roses intwining shady bowers of lattice-work, roses wreathing triumphal arches, roses bordering long winding walks, delicious thickets of roses so dense that the sun’s rays had not yet dried the dew from their velvet petals.

On her head was a wreath of pink roses, at the waist of her beautiful fleecy white gown, were white and pink ones blended in exquisite contrast.

[31]

By her side, with his arm about her slender, supple waist, walked handsome St. George Beresford.

They were lovers.

And in this beautiful rose garden they seemed to be as much alone as Adam and Eve were in Eden.

No faintest sound of the great surging, wicked world intruded on the delicious solitude—nothing came to their hearing save the low murmur of the distant sea, that soft music breathing the soul of love, and the song of birds mating and nesting in the rose-trees that shook down their bloomy petals in rosy clouds over every path.

They did not miss nor want the world in this Eden. They were all in all to each other, this beautiful pair of lovers.

They roamed here and there with their arms about each other, speaking but little, only now and then Beresford would pause to draw her into his arms and caress her, murmuring between ardent kisses:

“My only love, my bride!”

Beautiful, dark-eyed, jealous Maybelle Maury was forgotten just as entirely as though she had never existed. They were blissfully happy in this dream that Floy was dreaming there that May night in the grim shadow of Suicide Place.

But suddenly a dark, portentous cloud overspread the sky, and a low rumble of thunder shook the earth.

The soft voice of the sea changed to a hollow roar, as though a storm were lashing its waves into fury, and the tender music wailed itself into silence like the cry of a broken heart. The winds rose and lashed the rose-trees in a furious gale, till the air was full of their flying petals and spicy perfumes. The song-birds fled affrighted, and their little nests were dashed upon the ground.

[32]

“Oh, I am so frightened! Save me!” sobbed pretty Floy, clinging to her fond lover, who clasped and kissed her again, whispering that there was no danger for her while he was by his little darling’s side.

But at that very moment a flash of lightning irradiated the gloom, and Floy saw a woman dashing toward her in insane fury.

She had the dark, beautiful, jealous face of Maybelle Maury, and she rushed between them and thrust Floy away.

“Go, girl, go! He is mine, mine, mine!” she was crying, madly, when all at once Floy awoke, as we do in dreams at some moment of unbearable grief and woe.

Her dream had been only half a dream, after all.

The moonlight was darkened by clouds, there was low, rumbling thunder, followed by flashes of lightning, and a fitful rain was driven into the porch by the wayward wind, wetting Floy’s face and hands and dress. It was this that had woven itself in with her dream and awakened her to unpleasant reality.

Dazed and wondering, she sprung to her feet, and it was several minutes before she could realize her position.

Then it came to her that Maybelle had dared her to spend a night alone at Suicide Place, and she had vowed she would do it.

She had come and fallen asleep on the porch and dreamed that exquisite dream that was so lovely until—Maybelle came.

“How strange that I should dream of Maybelle’s lover—and dream that he was mine!” she murmured, wonderingly, as she hurried into the house out of the muttering storm.

Fortunately she had brought some matches, and she[33] knew that there was a lamp in the parlor, so letting herself in, she hurriedly lighted the lamp, throwing its feeble glare on the dark oak furniture of the long apartment.

“Whew! what a musty old place!” she ejaculated, throwing open a window, heedless of the fine mist of rain that came blowing in, mixed with delicious fresh air and gusts of delicate perfume from great lilac-trees outside loaded with white and purple blooms.

Then she uttered a cry of dismay and looked back half fearfully over her shoulder at a piano in a dark corner.

The lid was closed, but from the keys were coming low, discordant sounds, as of music played by childish hands all ignorant of time or tune. It was terrible, that sound, and Floy, who had never known fear before, felt as if ice-cold water were trickling down her spine.

Then a quick suspicion came to her, and running straight to the instrument, she threw back the lid.

Several mice that, alarmed by her entrance, had been running up and down the keys, producing discordant notes, jumped out upon the floor and ran away into the dark corners with little frightened squeaks.

Floy laughed aloud merrily:

“Just as I suspected, after my first moment of terror at that sudden sound. But a cowardly person would have sworn it was a ghost playing the piano. I wonder if that discord was the sweet music I heard in my dream?”

She threw herself into a large easy-chair cushioned in leather, and closed her eyes.

“I am not the least bit afraid—not the least,” she declared aloud. “But I wish I could go to sleep again and dream the first half of that lovely dream.”

But slumber refused to visit her eyes again. She felt preternaturally wide awake.

[34]

Rising, she paced up and down the room, listening to the muttering of the storm outside, and the wild rain driving against the creaking old windows.

Several old family portraits hung against the walls, and the eyes of those buried ancestors seemed to follow her up and down with grim curiosity as she moved to and fro.

Such a thing will seriously annoy one sometimes. The eyes of a portrait may take on a living look, and render one horribly nervous when alone at midnight.

Those following eyes, so persistent in their stare, annoyed Floy, and gave her the same creepy chill down her back that she had felt when the mice scurried over the piano keys.

She could not resist a sudden longing to escape from the room, and from the grim scrutiny of her pictured ancestors.

Taking the lamp in her hand, she started out to explore the house.

Hurrying along the draughty hall, and in and out of the musty old rooms familiar to her childhood, the girl tried to dispel the shadow that began to fall on her spirits like an ominous cloud.

Presently, over the roar of the storm outside, her voice rang out in a loud, wild, terrified shriek thrice repeated—then awful silence.

Half an hour passed by slowly.

The storm was over.

The lightning, thunder, and rain had ceased, and the[35] moon was coming out from the black wrack of clouds where she had hidden her glory.

Her silver light shone again upon the sleeping world, and flashed into the parlor window that Floy had opened before she left the room half an hour ago.

In the sheen of the moonlight, the staring eyes of the portraits on the wall seemed to be watching eagerly for their descendant to reappear.

The hall door opened softly, and Floy staggered across the threshold, bearing the lamp unsteadily in her small hand.

What a change had come over the sparkling riante face!

She was pale to the lips—pale as a ghost, as the saying goes—and there was a strange expression in her blue eyes, as if they had looked upon something uncanny.

With an unsteady step, as though she trembled in every limb, the lamp flaring dismally in her grasp, she dragged herself across the room to a long swinging mirror between the windows, and held the light up over her golden head, looking at herself carefully, as she whispered:

“I wonder if my hair has turned white?”

The words, coupled with her appalling shrieks of half an hour ago, proved two facts. First, that Floy had sustained a severe shock of some kind, since only sudden fright or grief is supposed to whiten the hair in a single hour; and secondly, that she was recovering from her alarm, as manifested by her anxiety over her personal appearance.

The long mirror gave her back faithfully the beautiful form with the graceful swelling curves of dawning womanhood, and the lovely face lighted by clear blue eyes, and crowned by waves of crinkly gold above the frank white brow.

[36]

No, her hair had not turned white, despite the untold horror that had shaken her soul to the center. Not even one silver thread shone among the gold.

Floy heaved a long, bursting sigh of intense relief, set down the lamp, and dropped wearily into a chair near the window.

The moon’s rays shone in her white face, so pale and horror-struck, and she saw that the storm was over and the sky clear again.

“Oh, how much longer must I stay here?—how long before the dawn?” she muttered, fearfully, gazing straight before her into the night, as if afraid to look back into the grewsome room with its dark, shadowy corners.

And this was Fly-away Floy, the fearless, with her nerves of steel, and her contemptuous disbelief in the supernatural—this pale, startled creature who had just looked into the mirror to see if the golden locks of youth had changed to the frosty ones of age.

What had changed and shaken the careless girl like this? Would she ever reveal the secret? Or would her indomitable pride seal her lips?

She leaned out of the window, reaching down and breaking off great clusters of wet, fragrant lilacs, in which she buried her stricken face, while low, bursting sobs convulsed her form—sobs of abject misery.

Hark! what was that sound? Only the low wind of the summer night soughing through the trees.

“No,” she cried, dismissing the fancy and springing to her feet, “it is a step in the hall!”

She clung to the window-sill, looking over her shoulder with terrified blue eyes, her heart beating wildly against her side.

[37]

She was half tempted to spring from the window and seek refuge in flight.

But it was at least ten feet from the ground, and she did not fancy the idea of making a cripple of herself.

The door was suddenly flung open, and a laughing voice exclaimed, eagerly:

“Where are you, Floy?”

The very sound of a human voice was bliss to her after the long and fearful night.

She sprung up, sobbing with joy and relief, as Otho Maury entered the room with a lantern.

“So you have come for me! I—I didn’t guess it was near daylight yet,” she faltered.

“It isn’t, Floy—only a little past midnight.”

He came up to her with a jubilant air, and his eager, dark eyes burned on her face as he continued:

“But I couldn’t rest for thinking of you, Floy, all alone in this terrible place, exposed to Heaven knows what dangers! I—I—my heart ached for your loneliness, dear little one, and so I came to share your vigil.”

At the first moment her face had brightened with relief, but when he came up close she drew back shrinkingly, and at his words she took swift alarm.

“You have been frightened. I knew you would be, though you pretended to be so brave. I see the tears on your lashes. Now, aren’t you glad I came?” triumphantly.

“Yes, I’m glad, for I did wrong to come. I’ve grown nervous waiting here alone, and you may take me home at once,” she answered, gratefully, throwing on her hat and turning toward the door.

“Wait a little, Floy, for there’s a storm coming up. I[38] did not think you would want to go until daylight, when the committee called for you with a carriage.”

She recoiled, looking at him with startled eyes.

“Do you mean to say that they did not come with you—that you came here alone?” she demanded.

“Why, yes, that was what I told you, Floy. I feared the storm would frighten you, so I came to remain with you till morning.”

The wet lilacs at the window shook and rustled as in a rising gale, but neither heeded it in their excitement.

He pressed closer, and tried to take her hand, but she drew herself to her full height, the color rushing to her pale cheeks, her eyes like blue fire.

“Go! leave me at once!” she commanded, imperiously.

“Leave you, Floy—I can not! Did you not confess just now that you had grown nervous waiting here alone? And there were tears on your lovely cheeks when I found you drooping here. No, darling, I shall stay and cheer your solitude.”

“Is the man mad, or does he think me an ignorant child with no knowledge of the world and its ways? Listen, Otho Maury: you can not remain here through the night with me, for what would people say to-morrow?”

She seemed to grow taller with each word so bravely spoken, as she stood before him like an imperious little queen, her finger still pointing to the door.

But the man made no motion to obey, and his manner was full of a jaunty insouciance that filled her with indefinable dismay.

“Nonsense!” he answered, airily; and his voice sunk to a tender cadence as he continued: “Darling little Floy, no one need know of my being here to-night. No one knew of my coming, and I can slip away just before[39] daylight, don’t you see? Then when the committee comes you will be found alone bright and happy, and they will believe your proud boast that you were not the least afraid to stay alone in Suicide Place.”

“I command you to go at once!” she said, angrily.

“I refuse to obey,” he returned, jauntily; and there was a streaming fire of elation in his eyes that almost drove her wild.

“Then I shall go and leave you here!” she said, scornfully, turning to the door; but he barred her way. “I can spring from the window!” she cried, moving to it, and not noticing the rustling of the lilac branches.

“And kill yourself,” he sneered. “No, Floy, you will not be so rash. You will stay here with me, for I love you madly, beautiful one! and I came here to be alone with you where none could interfere, that I might clasp your lovely form to my heart and kiss your scornful lips till they yielded to my caresses, till your heart thrilled to mine with responsive love!”

“Why, I hate you! hate you! hate you! you cowardly villain, you infamous cur!” raged Floy, tempestuously, as she tried to rush past him and gain the door.

But Otho was too quick for her, agile as she was. Rushing forward, he caught her in his arms, pressing her tightly to his breast, heedless of her wild shrieks of fear and prayers for mercy.

Struggling fiercely to bend back her fair head and kiss her crimson lips, the villain did not catch the rustling sound of the branches at the window, as a man who had been hiding and listening there came at a bound over the sill and into the room.

But the next moment Otho’s arms were caught in a grasp of steel, and a hoarse voice thundered:

[40]

“Release the lady, you vile hound, and take your punishment!”

It was St. George Beresford, raging like a lion in his fury, and as Maury’s grasp on Floy relaxed, he caught up the slim, wriggling coward in his athletic grasp, shook him contemptuously, and flew over to the window.

Floy, raising up her eyes to her noble deliverer, saw him, pale with revengeful fury, as, with superb strength, he lifted Maury up to the window and hurled him through it over the tops of the lilacs far out into the grove.

Floy watched the punishment of Otho Maury with that boundless admiration a woman always feels for manly strength and power.

She thought that St. George Beresford was the grandest, bravest, most beautiful hero in the world, and her heart swelled with gratitude to him for his manly defense of a helpless girl.

But she was frightened, too, when she saw her persecutor’s body flying through the air, and she cried out, shudderingly:

“Oh, you have killed the wretch!”

But her preserver answered, coolly:

“No, indeed; more’s the pity! It’s only a few feet from the window to the ground. Besides, didn’t you hear the thud of his body on the soft wet grass? No bones will be broken, I assure you, though it ought to be his neck. But, anyway, this will teach him a much-needed lesson!”

[41]

And he laughed softly to himself at the ease with which he had sent Maury spinning through the window.

“Oh, I thank you so much—so much! I was so frightened!” faltered Floy, clasping her white hands in the intensity of her joy, and lifting to him her beautiful, clear blue eyes.

He smiled at her kindly, thinking to himself that it was the loveliest face in the round world, and answered:

“It was rather fortunate I came when I did, for I suspected the fellow had been drinking. That was why I followed him here when I found out he was coming.”

“Oh, how good you were—how good, I can never thank you enough!” cried Floy, putting out her hand to him in the exuberance of her gratitude.

Beresford clasped the little hand ardently, and longed to kiss it, but would not frighten her by such a demonstration.

“Poor little soul, she has been alarmed enough already,” he thought, generously; the pale cheeks and tear-wet lashes appealing to all the manliness within him.

“And now you will take me home, will you not?” added Floy, appealingly.

“Yes; for I came here with that purpose, and my carriage is waiting at the gate. Come,” he said, putting out the lamp and taking up the flaring lantern left by Otho Maury, as he moved toward the door.

Floy paused to shut down the window, and followed him, oh, so gladly, out of that horror-haunted house in the sweet moist air of the spring night, breathing a sigh of relief when she found herself going down the graveled walk, through the grove, by Beresford’s side.

“Oughtn’t we to see—if he is hurt or killed?” she murmured, timidly.

[42]

Beresford answered, carelessly:

“Oh, he is all right. I hear him coming behind us now.”

And, sure enough, a voice called, humbly:

“Beresford—Miss Fane! Will you please wait a moment?”

They paused, and saw Otho Maury limping dejectedly toward them, looking very meek in the bright moonlight that streamed through interstices of the trees.

Floy’s tender little heart gave a leap of joy that he was not killed, although she knew that he well deserved it.

He dropped with difficulty on one knee before Floy, muttering:

“I crave your pardon, Miss Fane, for my rudeness just now. I swear I meant no harm except to kiss you. But I had been drinking—and I will own it—I was mad with love for you. But I never should have frightened you so only that I had drunk too much wine and I lost my head. I’m glad Beresford threw me out of the window, for my madness deserved it, though I’m a mass of bruises, and my ankle is either sprained or broken. But that does not matter so that you forgive me. Will you?” contritely.

Floy had the tenderest heart in the world, and Otho’s repentance was so frank and engaging that she hesitated.

“Do you think I ought to forgive him?” she whispered to Beresford, with a ravishing little air of reliance on his judgment!

He shrugged his shoulders, and replied, carelessly:

“Perhaps so—since he asks it.”

“Very well,” said Floy; and looking coldly at the offender, she said, proudly: “I forgive you, as you say you are sorry; but don’t you ever dare speak to me again!”

[43]

She was turning away, with her head held high in scorn, but he caught at her sleeve.

“One moment, please. I have another favor to ask of you and—Beresford,” the last word with a gulp, as if swallowing his pride with difficulty.

They both stopped to listen, and he muttered:

“Will you both keep the story of this affair a secret? It will ruin me if it becomes known. My father—he has threatened to disinherit me if I do not quit drinking. I had promised him, but I—I broke my word to-night. Then, too, the ridicule of my set—you know how it could sting. Beresford, for God’s sake, be merciful, as you are strong and brave!”

He drooped before them—craven, abject, appealing, a cur to despise—in the moonlight.

Beresford knew that what he advanced was true; the story of to-night’s offense and its punishment would make Maury the laughing stock of all who heard it—would follow him with its blight through life.

He was disposed to pity the abject suppliant, the depths of whose meanness his own noble nature could not fathom.

So he answered, after a moment’s reflection:

“It shall be as the young lady says, of course, though I must say you do not merit her leniency.”

“I know too well that I do not, but she is an angel, and will grant my prayer,” muttered the wretched delinquent.

“No, I’m not an angel, and I hate and despise you, Otho Maury!” flashed the lovely girl, stamping her tiny foot on the wet gravel. “But I’ll keep your disgraceful secret as long as you never open your lips to me again. Do you hear?” angrily.

[44]

“I hear, and I’ll stick to the condition, though it’s a hard one. I had as soon be dead as banished from your presence,” sighing. Then he looked at Beresford. “And you?” he said, anxiously.

“I’ll never betray you unless you seek to harm Miss Fane again in any way, even by speaking her name lightly, as you may in malice be tempted to do. You understand?” sternly.

“Yes, and I’ll not forget that you have constituted yourself her protector.”

There was a furtive sneer under the pretended humility of the answer, but Beresford did not heed it, he merely said, warningly: “See that you keep your promise,” and turned away, going down the path with Floy at his side and out at the gate with her to the waiting carriage.

The craven wretch they had left behind followed more slowly, for he was indeed sore and bruised from his fall, and his ankle was twisted from his efforts to alight on his feet.

But as he had come afoot on his secret nefarious mission of evil, he was compelled to return the same way, cursing and groaning at every step with blended pain and chagrin, for his heart was filled with rage against Beresford.

“Curse him! He foiled my clever plan entirely!” he raved to himself.

Beresford led his trembling young companion out to the carriage that waited impatiently at the gates, the horses fretting and the driver swearing under his breath.

[45]

In fact, the young man had been charged a heavy sum for this service, the driver sharing to the full the common terror of Suicide Place.

So it was with a sigh of relief that he received from Floy the directions where to drive, after which she was handed into the carriage by her escort.

“With your permission I will see you safely home,” he said, courteously, springing in after her and closing the door.

They had something more than three miles to drive to Bird’s Nest Cottage, and each heart thrilled with the consciousness of happy moments to be spent together.

As he seated himself by her side, Floy thought of her exquisite dream of the rose garden, where she had walked by his side, with his arm about her waist and his low voice whispering love into her willing and enraptured ears.

Her heart began to throb wildly, the blood leaped warmly through her veins, she felt her cheeks flush and her eyelids quiver in the semi-darkness. She was so overcome with sweet and painful emotion that she could not utter a word, and Beresford, thrilling with the same sweet pain, also remained silent.

He was so madly in love with the little blue-eyed beauty by his side that it was with difficulty he restrained himself from clasping the dainty form in his arms and whispering to her all that was in his heart—the admiration, the tenderness, the passion, the yearning to woo and win her for his worshiped bride.

But the faint remnant of reason remaining to him whispered, warningly:

“Wait till she knows you better. Such impetuous violence would frighten and disgust the little darling!”

[46]

So each remained silent for a brief time, thrilled and dominated by the presence of the other, then Floy, coming back to herself by a great effort of will, murmured, softly:

“You said you came to take me home. Did any one send you?”

“No; I came of my own free will,” he returned, gently.

“Why—why, that was strange!” she faltered, wonderingly.

“Do you think so?” he asked; and there was a tender meaning in his voice that made her cheeks burn warmly, and her heart throb again so wildly that she could not speak. She, who had always been so saucy and ready-witted, flouting with scorn the flatteries of her admirers, could not think of any retort, could not unclose her lips for a coquettish reply.

Finding that she did not reply, her handsome companion continued:

“I wonder if you would be offended if I should tell you about a strange dream that warned me to come to your assistance!”

Floy started and thrilled, remembering her own beautiful dream, and she found courage to return:

“I—I thought you were too much offended with me to—to dream of me! Mr. Maury said you were so angry with me, you would not come back to the picnic.”

“That was not true. I was a little vexed with you, I own, but I was going back with Otho; only just as we stepped outside the gate, a telegram was handed me that necessitated my return to New York to-morrow, and my sailing for Europe the next day. The matter so worried me that I told Otho to go back without me, as I must[47] remain to see to my packing. I did not bring my valet here with me, and he went alone and made capital of my absence to tell you that falsehood, the villain!”

“Oh, how I hate the false, cowardly wretch, and how glad I am that you came when you did. I believe I should have died with disgust if he had succeeded in kissing me!” cried Floy.

Beresford wondered if she would be willing to kiss him; but he did not dare to offer the caress that was burning on his lips. His strong, true love made him timid and respectful.

He said, soothingly:

“I do not think he will ever dare to annoy you again.”

“I should think not, or I will tell Uncle John, and he will punish him,” Floy replied; then added, timidly: “But the dream that sent you to me?—I am quite curious over it.”

“I should like you to hear it, only—promise me you will not be angry,” tenderly.

“Of course not. One can not stop dreams. And this one must have been a good one.”

“It was charming!” he cried, vivaciously.

“Then tell me all about it.” And it seemed to him that all unconsciously to herself she nestled confidingly closer to his side.

He also leaned nearer, so that their heads were very, very close, so close that his warm breath ruffled the strands of her curly hair and swept her cheek, as he began:

“In the first place, I was seriously annoyed yesterday when I heard you answer Miss Maury’s challenge, by declaring that you would spend the night alone in the haunted house—I believe it is said to be haunted, is it not?[48] Although I was almost a stranger to you, and you seemed to avoid me somehow, I determined to seek an opportunity to dissuade you from your purpose, and to tell you frankly how imprudent such an adventure would be. I even determined that if you refused to listen to me I would seek out your parents and acquaint them with your girlish folly.”

“But I have no parents—only adopted ones, you know.”

“Yes; I heard the story of your life to-day from a young man who seemed to admire you very much,” returned Beresford; adding: “But of course that made no difference, as your adopted parents would exercise the same authority over you as your own.”

Floy remained demurely silent, smiling to herself at the thought of how those dear adopted parents always humored her every madcap whim.

“But,” continued the speaker, “after that came your sensational plunge into the water, frightening every one out of their wits. When the funny farce of saving you was over, and I went back for dry clothes, that telegram drove everything else out of my mind for awhile—even you,” tenderly.

Floy did not answer a word; she listened attentively, thinking how sweet and musical his voice sounded, and[49] how sorry she was that this charming drive would soon be over. She could have gone on, and on, and on with him forever.

But the cross driver, not sharing her predilections, swore at his horses and whipped them up impatiently, while Beresford added:

“The telegram drove everything else out of my mind until I retired, when I fell asleep and dreamed of you.”

“I dreamed of you,” repeated Beresford, bending lower over the girl until her fragrant breath floated up to him, and the magnetism of her nearness enveloped him in an atmosphere of passionate bliss. “I dreamed, little Floy, that you and I were alone together, walking in the most beautiful rose garden in the world.”

“Oh!” cried Floy, with a delicious start, throwing up her little hands.

Beresford caught one of them in his and held it tenderly, as if it had been a little trembling white bird, as he went on softly:

“Words are too weak to describe the beauties of that spot.”

“I can imagine it,” thought Floy, recalling her own dream of roses.

“It must have been in Italy, the sky was so deeply blue, and the roses so grand,” resumed Beresford. “There were thickets of roses so dense that the sun’s rays had not dried the morning dew sparkling on their petals. There were winding walks bordered with rose-trees; there were shady bowers wreathed with climbing roses; there were[50] roses on the ground, roses in your hair—white ones—and at the waist of your white gown were pink and white ones blended.”

“Oh-h-h!” breathed Floy, lost in wonder at the similarity of their dreams, and she listened breathlessly as he went on telling her how the far-off sound of the sea had come to his ears, mixed with the music that breathed of love—the same music she had heard in her own dream.

“Oh, how strange, how passing strange!” she sighed and he answered, tenderly:

“Yes, strange, but sweet, for now I come to the best part of it. And you must not be offended, Floy—remember, you said you would not—for in my dream we were lovers—you and I—and as I walked, my arm was around your slender waist, you raised your face to mine, I kissed it, and called you my love, my bride.”

One moment of thrilling silence, in which they could almost hear each other’s wild hearts leap with joy; then Floy cried, eagerly:

“Oh, let me finish the dream for you! Did not a terrific storm arise and frighten me so that I cried out to you to save me? Did not a dark, beautiful woman rush in and thrust us apart?”

“Yes, oh, yes! that was how it ended. How strange that you should guess at so much of my dream, Floy! But that was the way of it. You clung to me, begging me to save you, and I assured you that I would; and just then a beautiful woman—she had the very face of Maybelle Maury—rushed in and thrust us apart with wild, jealous threats. At that moment I awoke in a cold perspiration, trembling with alarm, and the memory of you rushed over me, and I thought of you alone in that old house so horror-haunted, and your voice seemed calling[51] for me to save you, until I sprung up, threw on my clothes, and darted from the room, intending to ask Maury to accompany me and take you away from that dreadful place.”

“Yes?” breathed Floy, eagerly, as he paused.

“Well, I met Maury’s man-servant in the hall, and on asking for Otho, was told he had gone out. The man begged me to follow and bring him back, as he had been drinking again against his father’s commands, and if it came to the old man’s ears there would be a terrible row. He added that Otho had boasted he was going out to keep an engagement with a lady; but he suspected he might be found at some gambling hell, as he often frequented such resorts.

“‘I will bring him back,’ I assured the man; and rushed from the house, goaded by a frantic suspicion, hurried to a livery stable through the raging storm, secured the carriage after a long argument, and reached Suicide Place soon after the cessation of the storm. You know all that followed. I followed the light in the window, and secreted myself in the shrubbery just in time to witness the entrance of Maury. I heard all that passed between you, clambered over the sill, and collared the wretch just in the nick of time.”

“Just in the nick of time!” echoed Floy; and she added, in a murmur, to herself: “Oh, that blessed dream that sent him to save me!”

He caught the whisper, and repeated, joyously:

“Yes, that blessed dream, for Heaven must have sent it to my pillow, forewarning me in dreams of your peril, that I might hasten to save you. But, Floy—forgive me for calling you that so boldly, but it seems so natural—-how strange it seems that you could follow my[52] dream in thoughts as you did. You must possess the gift of mind-reading.”

“No,” she answered, hesitatingly, then burst out, solemnly: “Oh, it’s so strange I can hardly tell you, and perhaps you will not believe me, but—I knew all your dream as soon as you began to relate it. For—this is the truth, sir, and not a girlish jest—to-night I fell asleep on the porch of Suicide Place before I came into the house, and dreamed the self-same dream just as you have told it, word for word.”

She paused, awed and trembling, overcome by the strange coincidence of her dream.

She heard St. George Beresford laugh low and joyously to himself; she felt him crush the hand he held against his throbbing heart, then he whispered, tenderly:

“Oh, happy, happy dream that brought us together! Let me interpret it, darling little Floy. It means that we indeed are lovers, that Heaven made us for each other. Do you not believe it?”

What Floy would have answered to her lover’s ardent question was lost in the rumble and noise of the carriage wheels as the driver reined up his horses in front of Bird’s Nest Cottage, and loudly announced:

“Here we are!”

Beresford handed Floy out, and walked through the cottage gate up to the door with her, whispering under the leafy shade of the honeysuckle vines a tremulous question:

[53]

“Will you give me love for love, darling Floy? Will you marry me?”

She tried to draw away the hand he held, murmuring, agitatedly:

“You—you have no right to talk to me like this. You are engaged to Maybelle.”

Her voice broke in a sob, and he put his arm around her, drawing her close to his side, hoping that the shadow of the vines was dense enough to prevent the inquisitive driver from watching their love-making.

“I’m not engaged to Maybelle; never was, either. What made you think so, my sweet one?” he whispered.

“Otho Maury told me so the night before the picnic. He said you were to marry his sister in the fall.”