CHILE AND HER PEOPLE OF TO-DAY

Uniform with This Volume

| Cuba and Her People of To-day | $3.00 |

| By Forbes Lindsay | |

| Panama and the Canal To-day. New Revised Edition | 3.00 |

| By Forbes Lindsay | |

| Chile and Her People of To-day | 3.00 |

| By Nevin O. Winter | |

| Argentina and Her People of To-day | 3.00 |

| By Nevin O. Winter | |

| Brazil and Her People of To-day | 3.00 |

| By Nevin O. Winter | |

| Guatemala and Her People of To-day | 3.00 |

| By Nevin O. Winter | |

| Mexico and Her People of To-day. New Revised Edition | 3.00 |

| By Nevin O. Winter | |

| Bohemia and the Čechs | 3.00 |

| By Will S. Monroe | |

| In Viking Land. Norway: Its Peoples, Its Fjords and Its Fjelds | 3.00 |

| By Will S. Monroe | |

| Turkey and the Turks | 3.00 |

| By Will S. Monroe | |

| Sicily, the Garden of the Mediterranean | 3.00 |

| By Will S. Monroe | |

| In Wildest Africa | 3.00 |

| By Peter MacQueen |

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

53 Beacon Street, Boston, Mass.

CHILE AND HER

PEOPLE OF

TO-DAY

AN ACCOUNT OF THE

CUSTOMS, CHARACTERISTICS, AMUSEMENTS,

HISTORY AND ADVANCEMENT

OF THE CHILEANS, AND THE

DEVELOPMENT AND RESOURCES OF

THEIR COUNTRY

BY

NEVIN O. WINTER

Author of “Mexico and Her People of To-day,”

“Guatemala and Her People of To-day,”

“Brazil and Her People of To-day,”

“Argentina and Her People of

To-day”

ILLUSTRATED FROM ORIGINAL AND SELECTED

PHOTOGRAPHS BY THE AUTHOR

BOSTON

L. C. PAGE AND COMPANY

MDCCCCXII

Copyright, 1912

By L. C. Page & Company

(INCORPORATED)

All rights reserved

First Impression, January, 1912

Electrotyped and Printed by

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. Simonds & Co., Boston, U.S.A.

To the jealousy of Francisco Pizarro was due the discovery and conquest of Chile. Reports having reached Pizarro that there were regions to the south yet virgin, and teeming with wealth richer than that of Peru, he sent Diego de Almagro, one of his lieutenants, with an expedition to conquer these unknown lands. Almagro failed, and later he sent Pedro de Valdivia with another expedition. There was another reason for sending these expeditions, for Pizarro hoped that neither of these men would return to Peru, since he feared their shrewdness and popularity.

Valdivia succeeded in establishing a permanent settlement, but himself fell a victim to the hardy tribesmen of the central valley of Chile, who were far different from the soft and mild Incas enslaved by Pizarro. He had found that it was no easy task he had undertaken, and the sturdy race of Araucanians was still[vi] unconquered when the Spaniards were driven out of the country by the generations that had grown up from the time of its first settlement.

The Chileans have ever been independent in thought and action, and they have proved to be the best soldiers of South America. The temperate climate, the mountainous character of the country and its isolation, and the admixture of blood with the unconquerable Araucanians, who most nearly resemble the North American redmen of any of the aborigines of South America, have all contributed to the development of this characteristic.

The government is now as stable and hopeful as that of any of the South American nations, and, because of its natural formation, Chile has developed into the strongest maritime nation of that continent. Its fine bays and harbours, its coal supplies and its long seacoast, undoubtedly destine Chile to be the master of the southern seas in the ages yet to come. Furthermore, its vast and fertile valleys, where every product of the temperate climate grows, and where immense herds of cattle may be fed, its mineral wealth and vast nitrate fields, undoubtedly destine it to a greatness on land as well as on the sea.

The history of Chile has always appealed to the writer, in common with thousands of other people, and it has been a pleasure to trace the development of the country from its incipiency to its present condition. The same care has been exercised in the preparation of “Chile and Her People of To-day” as in the other books of the series, which have been so well received. Any repetitions that appear of expressions or ideas are intentional and not the result of hasty or careless preparation.

The author wishes to acknowledge his obligation to The Pan-American Bulletin for two or three photographs which appear in this work, and also to the Bureau under which it is issued for many courtesies received at the hands of the Director and his associates.

Nevin O. Winter.

Toledo, Ohio, January, 1912.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Preface | v | |

| I. | The Country | 1 |

| II. | The West Coast | 19 |

| III. | Vale of Paradise | 46 |

| IV. | The City of Saint James | 69 |

| V. | The Granary of the Republic | 92 |

| VI. | The Land of the Fire | 120 |

| VII. | The Backbone of the Continent | 148 |

| VIII. | A Laboratory of Nature | 178 |

| IX. | The People | 191 |

| X. | An Unconquerable Race | 212 |

| XI. | Education and the Arts | 230 |

| XII. | The Development of Transportation | 243 |

| XIII. | Religious Influences | 261 |

| XIV. | The Struggle for Independence | 280 |

| XV. | The Nitrate War | 315 |

| XVI. | Civil War and Its Results | 336 |

| XVII. | Present Conditions and Future Possibilities | 360 |

| Appendices | 391 | |

| Index | 405 |

| PAGE | |

| A Chilean Girl with the Manta (See page 90) | Frontispiece |

| Map of Chile | 2 |

| The Andes from Santa Lucia | 6 |

| The West Coast | 20 |

| A Milk Boy in Peru | 28 |

| Row Boats Crowding around a Steamer | 33 |

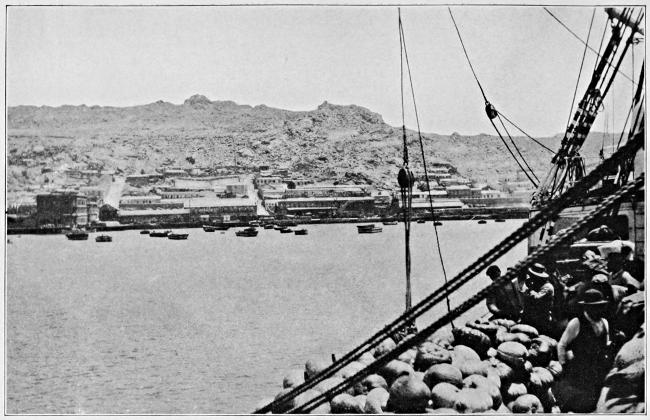

| The Harbour of Arica | 36 |

| A Street Scene, Antofagasta | 42 |

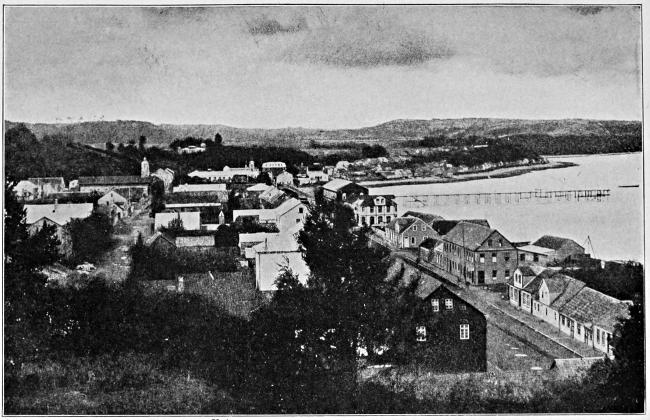

| Coquimbo, a Typical West Coast Town | 44 |

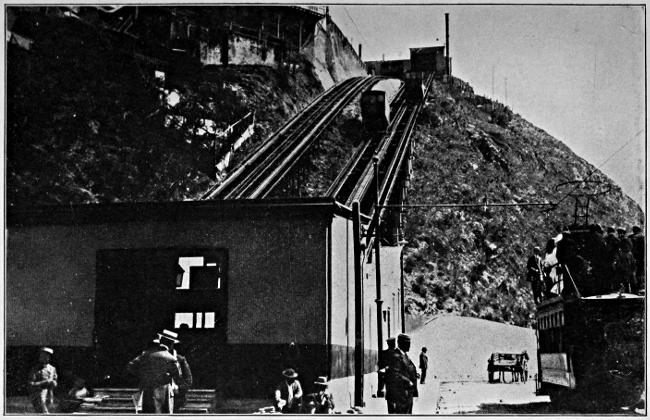

| An “Ascensor” in Valparaiso | 47 |

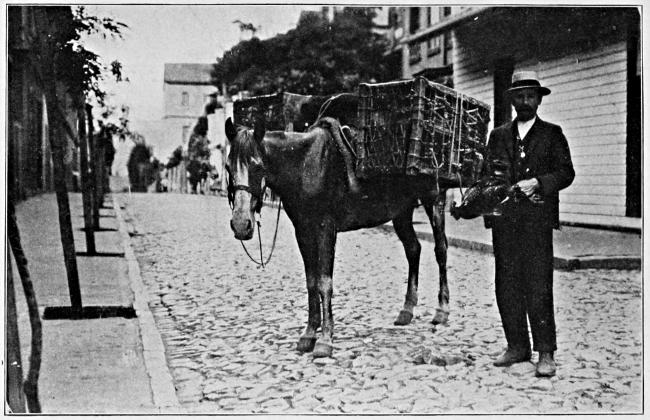

| A Chicken Peddler, Valparaiso | 57 |

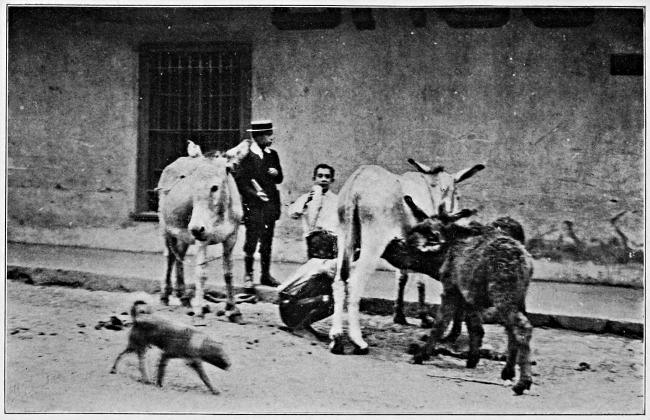

| A Vender of Donkey’s Milk, Valparaiso | 58 |

| An Attractive Home, Viña del Mar | 60 |

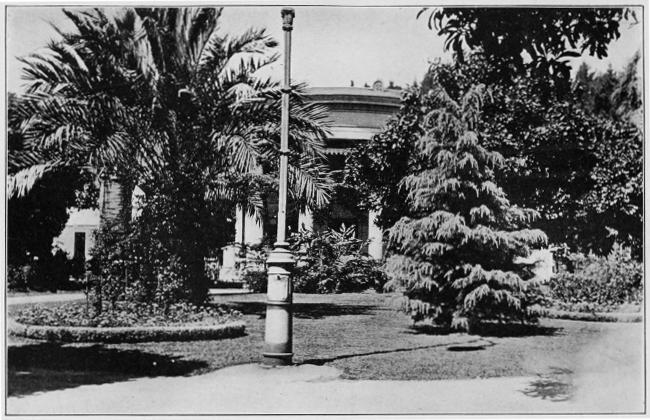

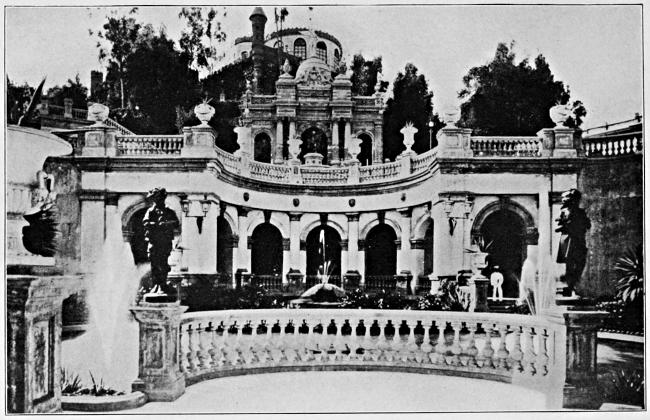

| Santa Lucia | 71 |

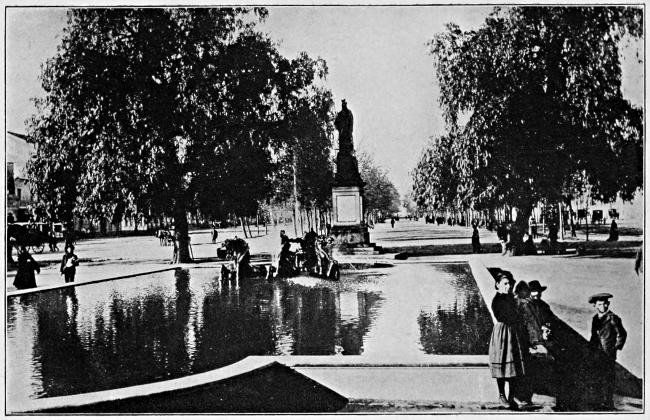

| Alameda de las Delicias, Santiago | 72 |

| Dancing La Cueca, the National Dance | 75 |

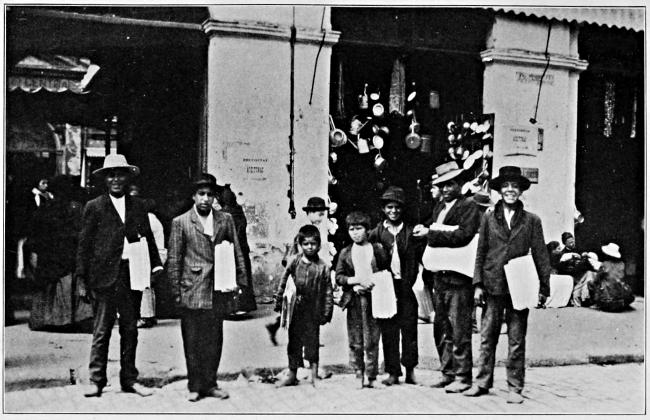

| A Group of Newsboys, Santiago | 81 |

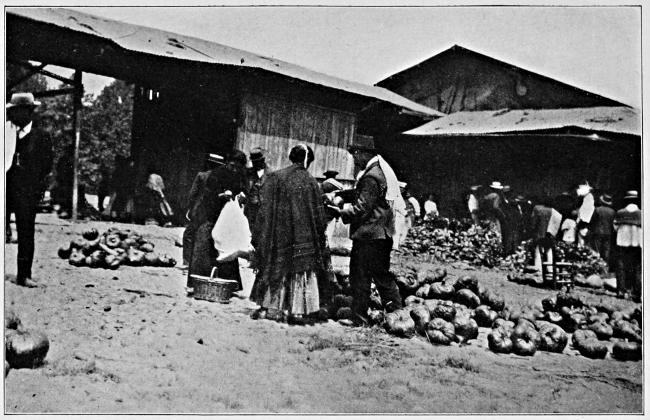

| A Market Scene, Santiago | 82 |

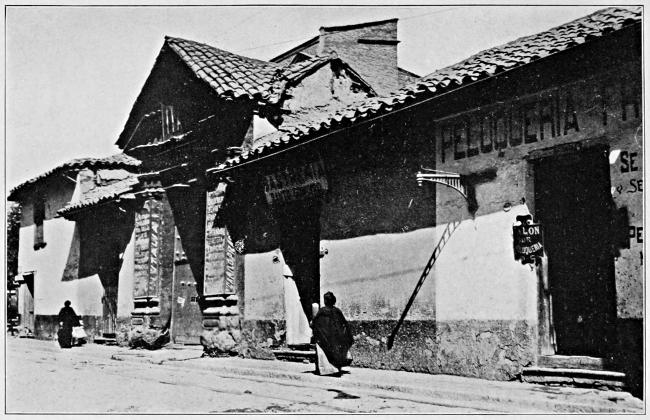

| The Oldest Building in Santiago | 89 |

| A Plantation Owner | 97 |

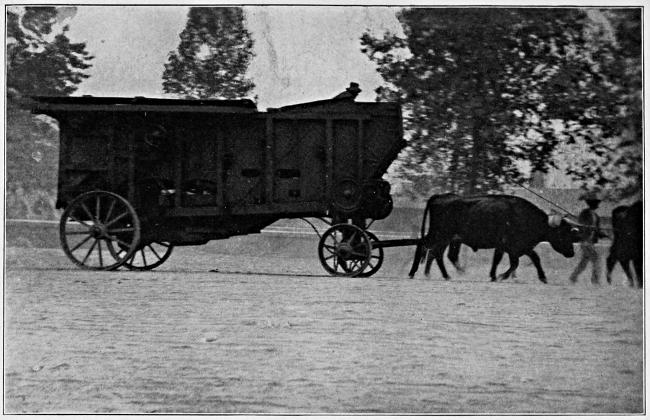

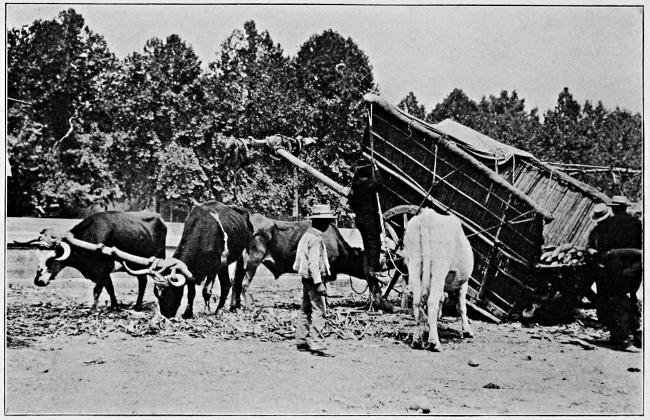

| Drawing an American Thresher | 99 |

| View of Puerto Montt | 108 |

| In the Straits of Magellan | 122 |

| A Wreck on the Coast of Chile | 128 |

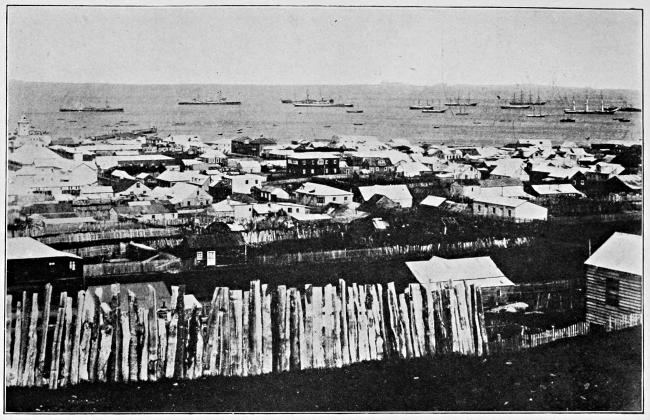

| General View of Punta Arenas | 132 |

| [xii]Port Famine, in the Straits of Magellan | 135 |

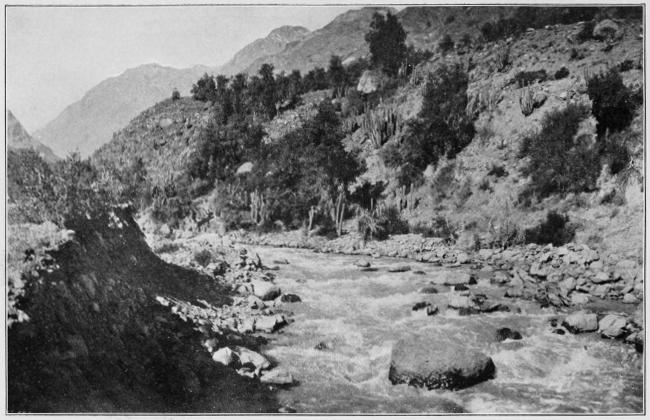

| The Aconcagua River | 149 |

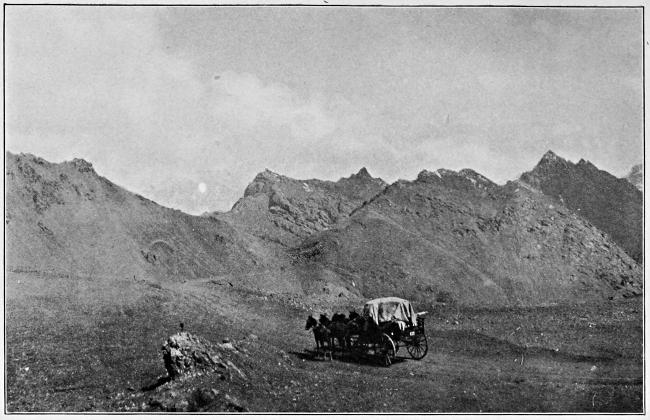

| Looking towards Aconcagua | 151 |

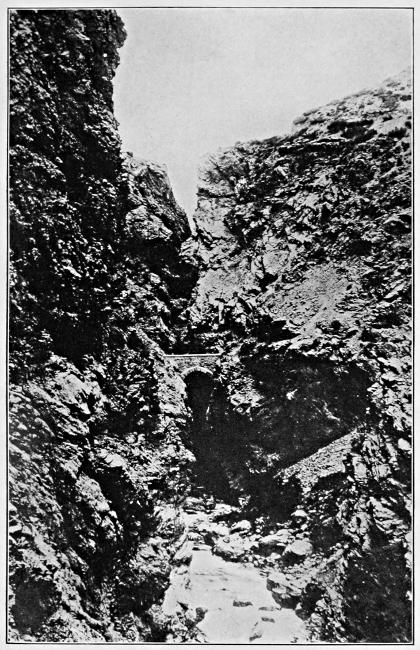

| The Salto del Soldado | 154 |

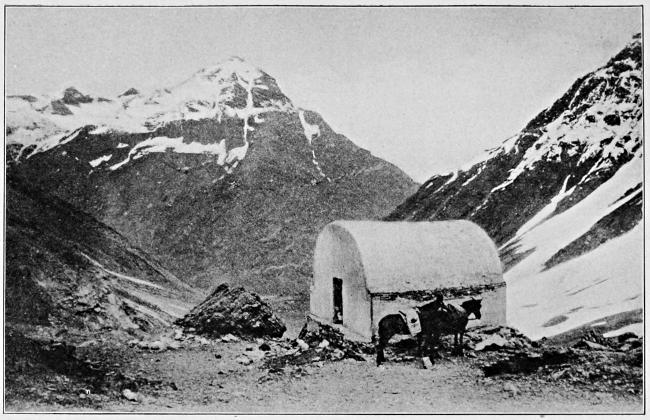

| Refuge House along the Old Inca Trail | 157 |

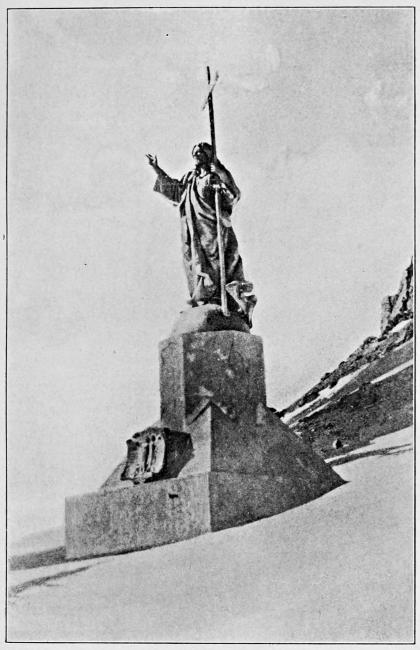

| The Christ of the Andes | 161 |

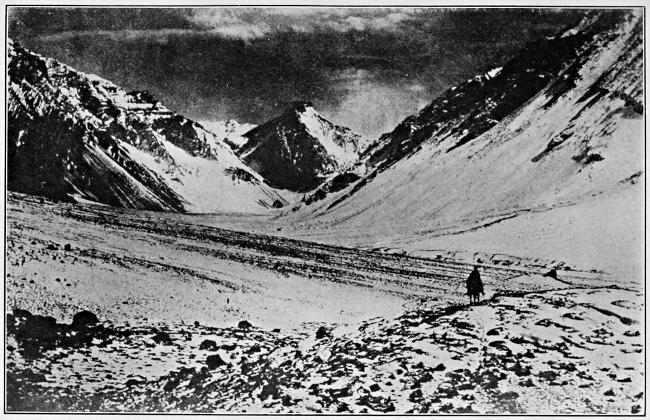

| The Solitude of the Andes | 163 |

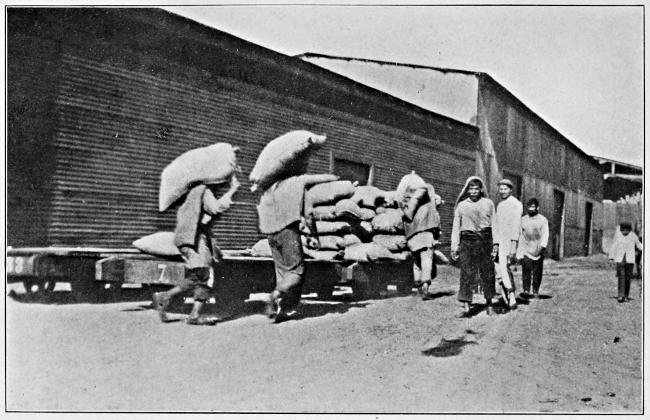

| Loading Nitrate | 186 |

| A Group of Chilean Girls | 206 |

| Ox Carts | 223 |

| The Escuela Naval, Valparaiso | 233 |

| The Harbour, Valparaiso | 248 |

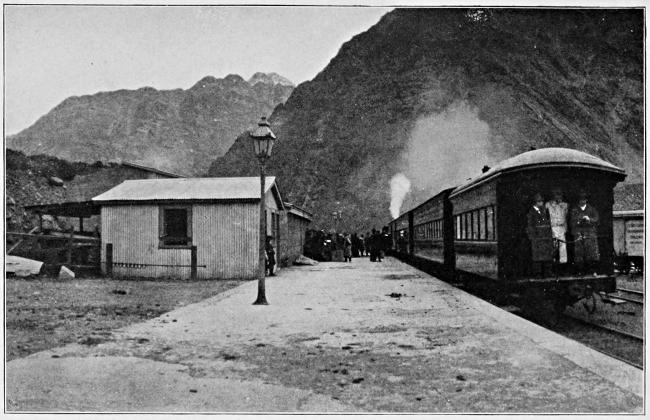

| Juncal Station | 258 |

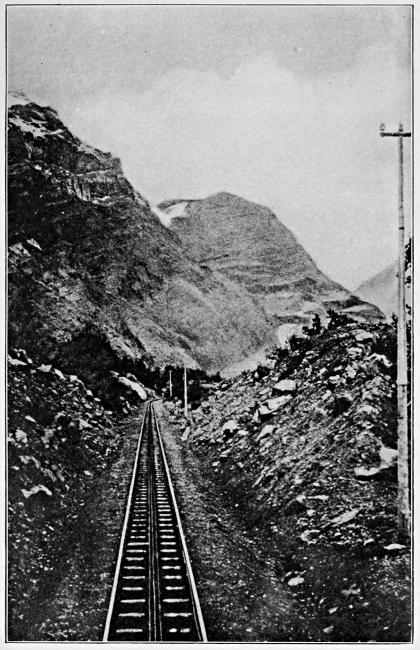

| Transandino Chileno Railway, Showing Abt System Of Cogs | 260 |

| A Chilean Priest | 268 |

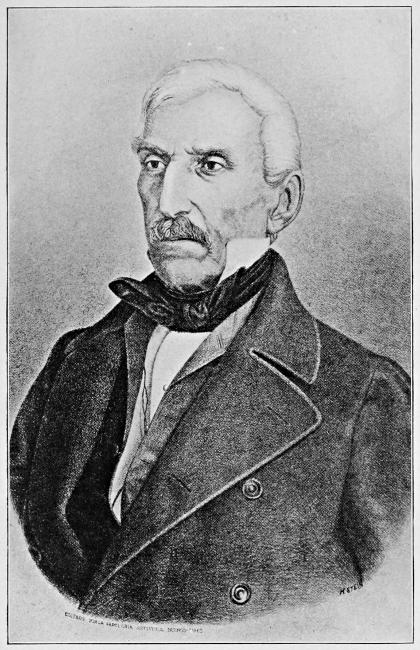

| José de San Martin | 289 |

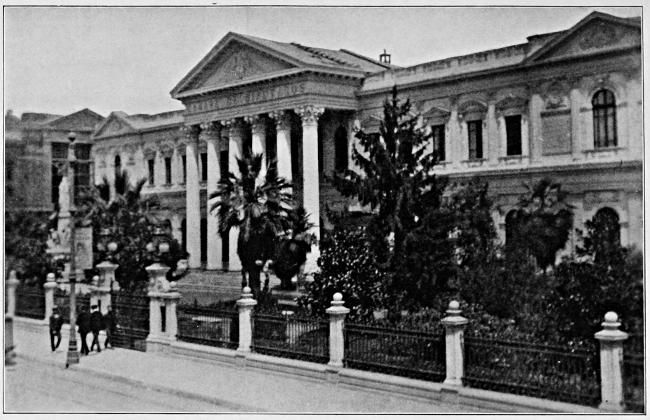

| Congress Palace, Santiago | 305 |

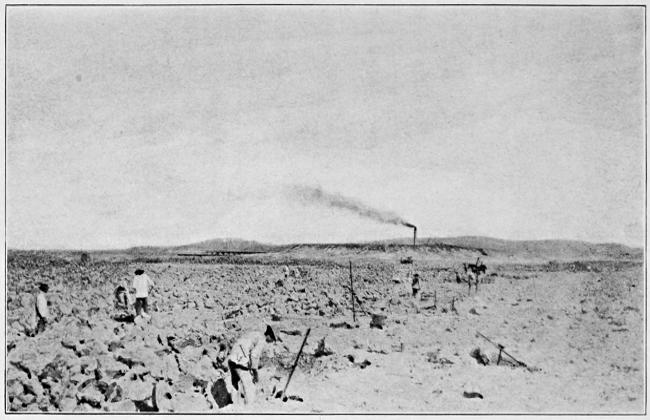

| Digging Nitrate | 316 |

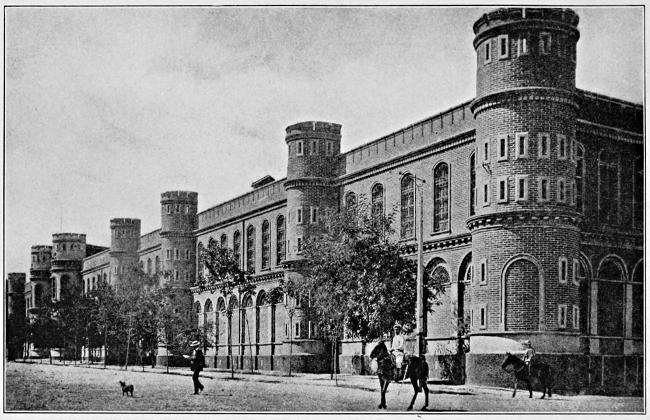

| The Military Barracks, Santiago | 346 |

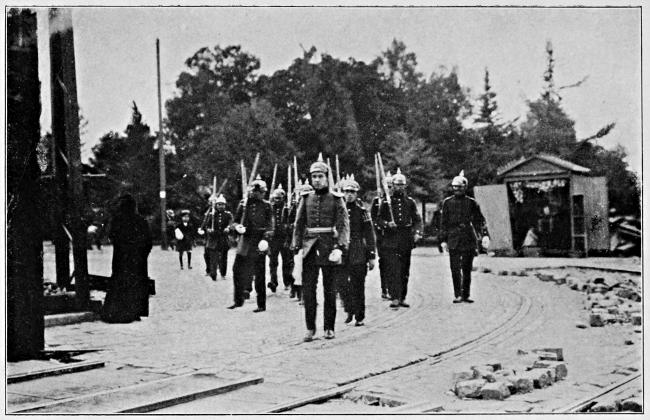

| Chilean Soldiers | 352 |

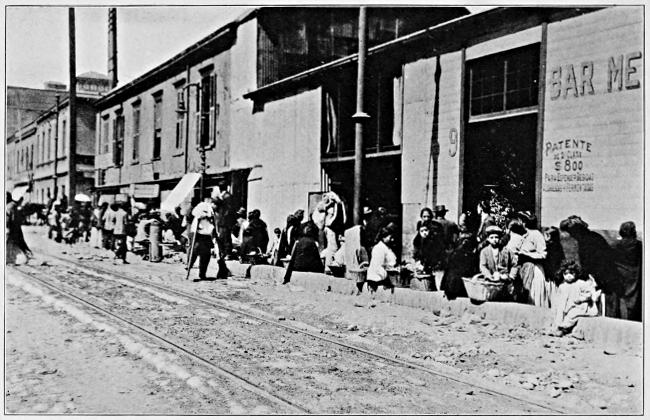

| A Market Scene, Valparaiso | 364 |

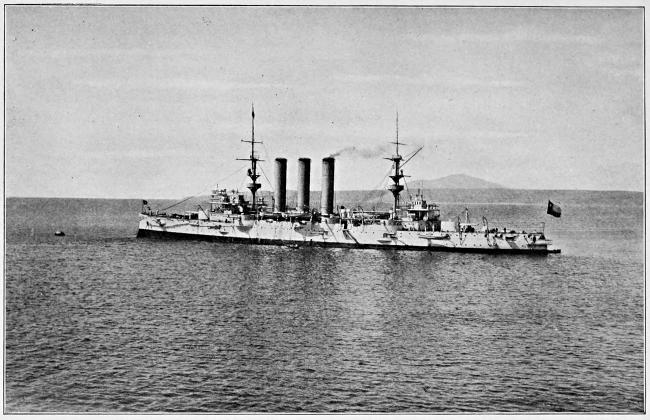

| The Battleship, “O’Higgins” | 371 |

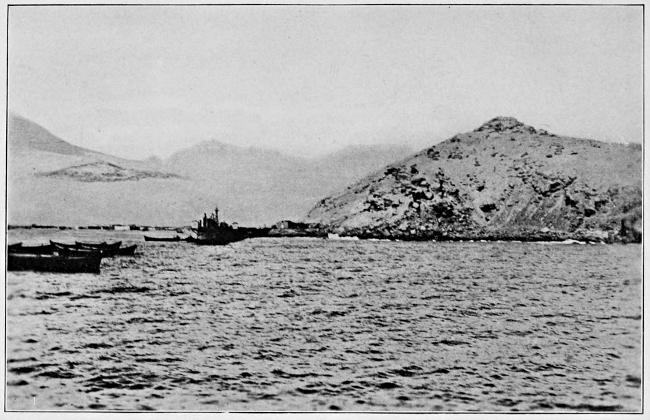

| A Typical Coast Scene | 377 |

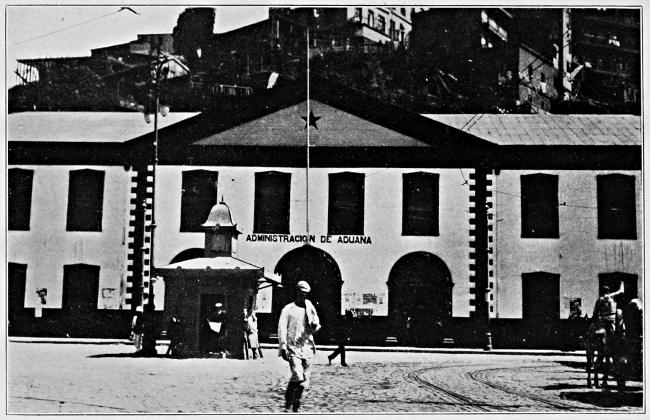

| The Custom House, Valparaiso | 388 |

The republic of Chile has one of the strangest configurations of any country on the globe. It stretches over thirty-eight degrees of latitude, thus giving it a coast line of twenty-six hundred and twenty-five miles from its northern border to the most southerly point on the Fuegian Archipelago. It is a long and narrow ribbon of land, at no place wider than two hundred miles, and in places narrowing to sixty-five miles. It has an average width of only ninety miles, while the length is fully thirty times the average width. Placed on the western coast of North America, in the corresponding latitude, this republic would extend from Sitka, Alaska, to a point on the Pacific coast opposite the City of Mexico. If the state of[2] Texas should be stretched out into a narrow strip of land two thousand and five hundred miles in length, it would give a fair idea of the peculiar shape of Chile. It follows quite closely the seventieth parallel of longitude, which would correspond with that of Boston. This strange development has been due to the Andean mountain range, which, with its lofty peaks and numberless spurs, forms the eastern boundary throughout its entire length. For a long time the boundary lines with its neighbours were in dispute, but these have all been successfully adjusted.

Transcriber’s Note: The map is clickable for a larger version, if the device you’re reading this on supports that.

Within these boundaries there is naturally a wide divergence of climate. In the north, at sea level, the vegetation is tropical, and it is semi-tropical for several hundred miles south. If one goes inland the mountains are soon encountered, and the line of perpetual snow is reached at about fifteen thousand feet, but this line descends as you proceed south. On the Fuegian Islands snow seldom disappears from sight, although at sea level it may all thaw. The temperature everywhere varies according to altitude and proximity to the sea. In the north it is milder than the same latitude on the eastern coast, because of the Antarctic Current[3] which washes the shores, and at the south it is warmer than the same latitude in North America. Within these extremes, from the regions which are washed by the Antarctic seas to the banks of the Sama River, which separates it from Peru, and between the shores where the Pacific breakers roll and the Cordilleras of the Andes which mark the boundary with Argentina, there are two hundred and ninety-one thousand, five hundred square miles, and supporting a population of three and a quarter millions of people, of many shades of colour.

One-fourth or more of the territory of Chile is made up of islands. The largest of these, of course, is Tierra del Fuego, of which a little more than one-half is Chilean territory. The coast from Puerto Montt to the southern limits of the continent is notched and indented with fiords and inlets, and scores of islands have been formed, probably by volcanic action. Few of these have claimed any attention, and, of all those lashed by the waves of the Antarctic seas, Tierra del Fuego is the only one that has received any development. The sheep man has taken possession of portions of that island, and hundreds of thousands of sheep now graze on its succulent grasses. The island of Chiloé,[4] near Puerto Montt, is one of the most important of the islands, and several small foreign colonies have been located on its rich soil. Some of the islands are very remote from the mainland. The most isolated one is Pascua, or Easter, island, which is at a distance of more than two thousand miles from the coast. It is almost in the centre of the Pacific Ocean. The San Felix and San Ambrosio groups, and that of Juan Fernandez, the reputed home of Robinson Crusoe, are also at a distance of several hundred miles from the shores of the republic.

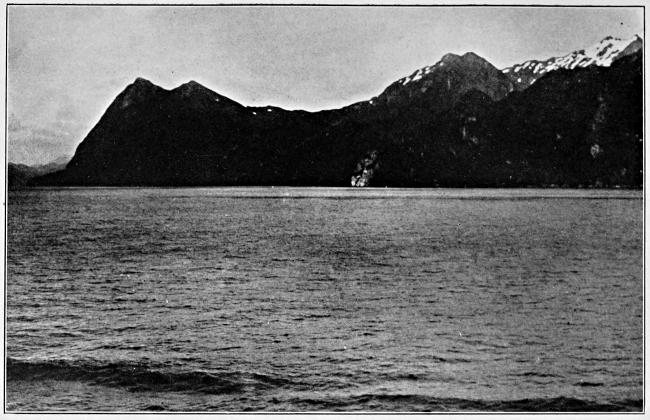

From the northern boundary to Concepción, the coast line is generally uniform and indentations are rare. There are only a few bays of any considerable size, and only an occasional cape or promontory. From Chiloé to Tierra del Fuego is a stretch of coast five hundred miles in length, which a glance at the map will show is a perfect network of islands, peninsulas and channels. This is the Chilean Patagonia. It provides scenery as grandly picturesque as the famous fiords along the coast of Norway, and greatly resembles that broken and rugged coast. The bays and gulfs cut into the shores to the foothills of the Andean[5] range. They are of great depth. The Gulf of Las Peñas furnishes an entrance to this labyrinth at the north, and the Straits of Magellan at the south. Some of the passes are so narrow that they seem like gigantic splits in the mountain ranges—grandly gloomy and narrow. Through these openings in the rock the water rushes with terrific force owing to the action of the tides. But, once within, the opening broadens out into little bays, where the waters are as calm and serene as a mountain lake. These channels are a vast Campo Santo, or God’s Acre, of wrecked vessels. Numerous as the disasters have been the sight of a stranded boat is rare, for the grave is usually hundreds of fathoms deep. In every case, however, the wrecked vessel has given her name to the rock that brought disaster, and the official charts are dotted with the names of rocks, which thus form eternal headstones for the unfortunate vessels. One writer has given the following account of these channels:—

“If one can imagine the Hudson River bordered continuously by verdure-covered mountains descending precipitously into the water, and jutting out here and there in fantastic buttress-like headlands, one has some[6] idea of Messier Channel. But add to this a network of long, thin cataracts threading their way thousands of feet down through gullies and alleys from mountain crest to water edge. Far up the mountain sides they are so distant as to seem motionless, like threads of silver beaten into the crevices of the rocks; but near the water their motion can be both seen and heard as they fall amid the rocks to reach the sea.”

The southern portion of the republic terminates in two peninsulas, known as King William and Brunswick, which are separated by the gulfs of Otway and Skyring. The Straits of Magellan then separate the mainland from the Fuegian Archipelago. This channel, which varies in width from one to twenty-five miles, is three hundred and sixty-two miles in length from Cape Pillar to Cape Virgenes, the latter being the eastern, or Atlantic, terminus. It affords a safe passage for vessels, and is used almost exclusively by steamers bound from one coast to the other.

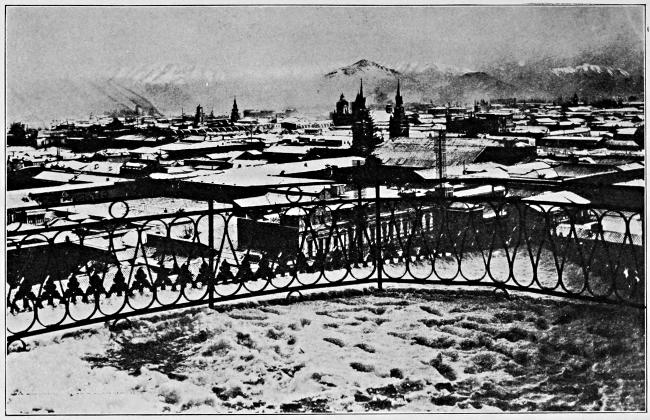

THE ANDES FROM SANTA LUCIA.

After forming the plateau of Bolivia, the Andes, the backbone of South America, stretches down to the lower end of the continent. It is formed by a succession of high[7] mountains, with lofty peaks covered with the eternal snows. At intervals passes are found which permit of access from one side of the mountain to another. The highest point of this mighty range is reached just opposite Valparaiso, Mt. Aconcagua, and from there it descends until, at the Straits of Magellan, it reaches sea level. It probably continues still farther, but its highest spurs are engulfed beneath the ocean. The width also varies greatly, from forty-five to one hundred miles. Along the Chilean border there are more than fifty definite peaks exceeding thirty-three hundred feet in height, and twenty-nine of more than ten thousand feet in altitude. Four are above twenty thousand feet. Most of these were originally volcanoes, but they are nearly all now extinct or quiescent. South of Aconcagua is a succession of lofty volcanic peaks, such as San José de Maipu, San Fernando, Tingueririca and others, all apparently extinct. Then follow Nevado del Chillan, Antuco, Villarica and Osorno, all of which occasionally emit vapour, and, lastly, the Tronador (thunderer) near the southern extremity of the country.

By reason of its peculiar shape easy access[8] is given to all parts of the republic, and the exploitation of its resources has been comparatively easy. In no place are the mountains far distant, and short spurs of railway connect the mineral deposits with the sea. Along the coast there are no fewer than fifty-nine ports, between which regular communication by steamer is carried on. Fourteen of these are ports of entry, in which customs houses are located, and the others are minor ports, at which only national coasting steamers stop.

There are very many rivers in the country, but only a very few of them are any aid to navigation. They are mostly short streams which are formed by the melting snows of the Andes, and then rush onward toward the sea by a more or less direct route. The principal rivers are all in the southern half of the country. In the deserts of the northern section the waters formed by melting snows are evaporated or are absorbed by the parched soil long before they reach the sea. The Yelcho and Palena are the largest rivers of Chile. The latter is the longest, for it cuts through a pass in the Andes and runs back into Argentine territory for seventy-five miles. Others are the Maullin, Calle-Calle, Bio-Bio, Bueno and[9] Maule. Some, such as the Bio-Bio and Maule, are navigable for short distances by vessels of shallow draft. Their importance to commerce is insignificant, however, when compared with the great rivers of the eastern coast. The Bio-Bio, for instance, is only one hundred and sixty miles long. They do furnish water for irrigation purposes, only a small portion of which has as yet been developed. There are several lakes in Chile, of which Llanquihue, Todos Santos, and Ranco are the most important. The two first mentioned have steam navigation.

There are many valleys of very fertile land which can be made among the richest agricultural lands of the world. As a rule these valleys are small and irrigated by streams flowing from the east to the west. The great central valley, which runs in a southerly direction for several hundred miles from Santiago, is one of the most remarkable features of the country and the garden of the republic. This valley is almost six hundred miles in length from north to south, but varies considerably in width. Its average width for the entire length is probably thirty miles. This is the granary of the country, and the source of its principal food supply. All of the cereals grow to perfection[10] in this climate and on this soil. Wheat, barley, corn, rye and oats are cultivated in large quantities. All of the vegetables and fruits that flourish in the temperate zone of the Northern Hemisphere also grow to large size. Alfalfa makes a fine pasture. And yet even this fertile valley has only been developed in part. Not more than one-fourth of the landed surface of Chile is fitted for cultivation, but of this portion not more than one-fourth has been touched by the agriculturist or ranchman. Hence there are great possibilities of development yet unexploited in this republic. Cattle and sheep are profitable and are increasing in number. The waterfalls, also, give great possibilities of cheap power for manufacturing purposes, and the future will probably find all of the railroads operated by electric power, because of the cheapness with which current can be produced. This result seems to be only the natural outcome of existing conditions.

Such a country, with such a long extent of sea coast, would ordinarily be an almost impossible country to handle. It has, perhaps, been fortunate that the coast is easily reached in all parts, from the inhospitable deserts of the northern regions to the dense forests of the[11] south. No country of equal size in the world has such a marvellously varied configuration. The humming-bird follows the fuchsia clear to the Straits of Magellan, and the penguin has followed the fish almost as far as Valparaiso. The government has done well in managing this ribbon-like country. Coast service has been built up and a longitudinal railway promises an interior development. Cross lines and transcontinental routes will provide much needed facilities for the interchange of commerce. The telegraph and telephone have linked together hitherto remote sections, and a creditable postal service has been created.

Chile is a republic, with the customary division into legislative, executive and judicial branches. It is not a confederation of provinces, as in Brazil and Argentina, but is a single state with one central government. It is divided for governmental purposes into twenty-three provinces and one territory. These are again divided into departments, districts and municipalities. Congress is composed of a Senate and Chamber of Deputies. The former is at present composed of thirty-two members and the latter of ninety-four. Deputies are elected for a term of three years[12] by direct vote, in the proportion of one to every thirty thousand inhabitants. Senators are elected for six years in the proportion of one to every three deputies, and the terms of one-third expire every two years. Members of the House of Deputies must have an income of five hundred dollars a year, and a Senator must be thirty-six years of age and is required to have an annual income four times that sum. Congress sits from June 1 to September 1 each year, but an extra session may be called at any time. A peculiar feature is that during the recess of Congress a committee consisting of seven from each house acts for that body, and is consulted by the President on all matters of importance.

The President is chosen by electors, who are elected by direct vote, for a term of five years. He serves the state for a salary of about eleven thousand dollars, including the allowance for expenses. He is ineligible to serve two consecutive terms and may not leave the country during his term of office, or for one year after its expiration, without the consent of Congress. He has a cabinet of six secretaries, who are known as Ministers of Interior, Foreign Affairs, Justice and Public Instruction, Treasury,[13] War and Marine, Industry and Public Works. The Minister of the Interior is the Vice-President, and succeeds to the office of President in the event of his death or disability. Elections are held on the 25th of June every fifth year, and inauguration of the new President follows on the succeeding 18th of September. The cabinet may be forced to resign at any time by a vote of lack of confidence by Congress, to whom they are directly responsible. In addition to the cabinet there is a Council of State consisting of eleven members, six of whom are appointed by Congress and five by the President, who assist that official in an advisory capacity. Furthermore, when Congress adjourns, it appoints a standing committee of seven from each house, which acts as the representative of that body during vacation. The President must consult with it in certain matters, and the committee may request him to call an extraordinary session if, in their opinion, such a course is advisable.

There is a national Supreme Court of seven members that sits at Santiago, which is the final judicial authority. Courts of appeal consisting of from five to twelve members also sit at Santiago, Valparaiso, Tacna, Serena, Talca,[14] Valdivia and Concepción. There are also a number of minor courts which are located in the various provinces and departments. Each province is governed by an intendente, who is appointed by the President of the republic. The departments are governed by governors, who are subordinate to the intendentes, and the districts by inspectors, who are also appointed. The only popular element is the municipal district, or commune, which is governed by a board composed of nine men, who are elected by direct vote in each municipality.

When the Spaniards reached Chile they found native races occupying it. In the northern portions the tribes were under at least the nominal sway of the Incas, although separated from them either by the inhospitable Andes or dreary desert wastes. In the great central valley, however, the land appeared a pleasant garden, and so rich that nowhere had the Spaniards seen anything similar either for its fertility or the wealth of its fruits and herds. “It is all an inhabited place and a sown land or a gold-mine, rich in herds as that of Peru, with a fibre drawn from the soil rich in food supplies sown by the Indians for their subsistence”—so wrote the chroniclers. They lived[15] in comfort and had a certain civilization. Each cacique had his own ranch house, the number of doors indicating the number of his wives, of which some had as many as fifteen. These people were the Araucanians, who proved to be a brave and courageous race. The Spaniards immediately began their usual cruelties and efforts to enslave these people, but succeeded only temporarily. The natives soon rose in rebellion. Three hundred years of warfare decimated their ranks, but did not subdue them, and when the Spanish rule ended these people were as unconquered as when it began. Their history has been written in blood, but it is the struggle of a heroic race, and it is not dimmed by the excesses and cruelties that attached to the Spaniards in their efforts to subjugate and enslave these valiant people.

After he had conquered Peru, Pizarro sent an expedition south to explore the country and take possession of it in the name of the King of Spain. One of his lieutenants, Diego de Almagro, was placed in charge. He crossed the great nitrate desert and reached as far as Copiapó, where he was driven back by hostile Indians. He had reached a valley called by the natives Tchili, which signified in their language[16] beautiful, and that name was given to the country. A few years later, in 1540, another expedition was fitted out under Captain Pedro de Valdivia, which was more successful. He marched as far as the present city of Santiago, and founded a city, which has ever since remained the capital. Although colonists came from Spain, little progress was made for a long time because of the hostility of the Araucanian Indians. These attacks continued until 1640, when a treaty was concluded with these indomitable natives by which the Bio-Bio River was established as the boundary, and both together were to resist the English and Dutch buccaneers, who had begun to harass the coast. Early in the nineteenth century the spirit of independence reached Chile, and insurrections against the Spanish authorities broke out.

On the 18th of September, 1810, the Spanish authorities were deposed and a provisional government was set up. Troops were poured in by Spain, and it was not until 1818, when the Spanish troops were defeated in the battle of Maipu by the Argentine general, San Martin, that freedom from the foreign yoke was secured. General Don Ambrosio O’Higgins, an Irish patriot who had greatly distinguished[17] himself in the war for freedom, was chosen as the first President, and he introduced many reforms and endeavoured to ameliorate the condition of the natives. The Jesuit missionaries followed in the wake of the soldiers and began their work of converting the natives. Since that time there has been considerable internal struggle between rival political factions, and some foreign troubles. There was a brief war with Spain, a frightful conflict with the neighbouring republic of Peru, and disagreements with Bolivia and Argentina. A few years ago war with the latter country seemed inevitable over the international boundary, but wise counsels prevailed and the matter was successfully arbitrated. At the present time peace prevails, although there are continual mutterings in Peru, and that country only needs a hot-headed leader to bring about another war with Chile over the lost revenue from the nitrate fields.

The Chileans are a brave and a courageous people. The natural boundaries have no doubt aided in developing a national spirit and love of independence. Truly no people in South America have fought so long and so hard to achieve national independence. The Araucanian[18] mixture has brought virility and industry into the race—a far different element than the Inca blood farther north. These Yankees of the South American continent have accomplished much, and there is still greater promise for the future.

Cruising along the west coast of South America is a delightful experience. It is the perfection of ocean travel. One is always sure of fine weather, for it neither rains nor blows, and the swell is seldom strong enough to make even the susceptible person seasick. In defiance of our idea of geography the sailors speak of going “up” the coast, when bound towards the south. The boats along this coast are built for fair weather and tropical seas. They have their cabins opening seaward, and the decks reach down almost to the water’s edge. Some swing hammocks and sleep on deck, and it is very comfortable. Such vessels would not be adapted for the stormy Atlantic, and would not live long in a storm upon the Caribbean Sea. Sailors say that the wind is never strong enough to “ruffle the fur on a cat’s back,” and this immense stretch of sea might be likened unto a great mill pond. It is this part of the[20] ocean, between the Isthmus and Peru, that suggested to the Spaniards the name of Pacific.

Near the equator the days and nights are equal. The sun ceases doing duty promptly at six, and reappears at the same hour the following morning. There is no twilight, little gloaming, and darkness succeeds daylight almost as soon as the big red ball disappears in the western sea. At night beautiful phosphorescence may be seen. The water is so impregnated with phosphorus, that each tiny wave is tipped with a light and the vessel leaves a trail of fire. From above the Southern Cross looks down upon the scene in complaisance. And thus the days pass in succession one after the other. The temperature is not uncomfortable, as the Antarctic Current tempers the tropical sun, and there is generally a southerly or southwesterly wind that aids. It is a pleasanter ride, and subject to fewer inconveniences than the ride along the eastern coast of the continent.

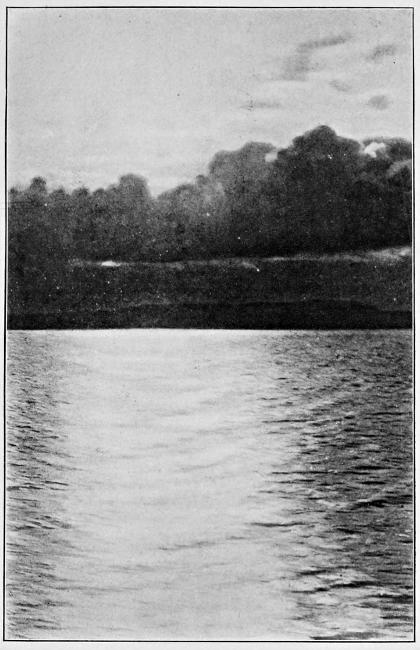

THE WEST COAST.

When the Stars and Stripes have faded from view at Balboa, and the jagged backbone of the continent has disappeared into the mists on either horizon, towards Nicaragua and Colombia, one feels that a new world has been[21] reached. The real South America has been entered, and, when the good ship crosses the Line, about the third day out, home and the rest of the world seem very far away. It is a long journey to Valparaiso, Chile, if one takes a steamer that stops at all the intermediate ports, as it lasts more than three weeks. There are swifter vessels, however, that avoid Ecuador and make the journey in twelve days. The slower vessels follow the coast line, and the passenger is given many a view of the Andes, whose peaks are crowned with eternal snows but are frequently wrapped in fleecy clouds. At Guayaquil, the westernmost city of South America, it is even possible on occasions in clear weather to see Chimborazo, eighty miles from the sea. Nowhere in the world is there a greater assembly of lofty peaks than will be seen as the vessel proceeds along the coast. The Spaniards called these “sierras,” because their uneven summits resembled the teeth of a saw. Some of the peaks are regular in outline, but more often they are irregular and even grotesque, so that the imaginative minds of the natives have fancied resemblances to works of nature and have given them corresponding names. Nowhere in the world are[22] there stranger freaks in geological formations, or more startling contrasts. Near the coast run the foothills, which gradually become higher and bolder until they end in the loftiest peaks. Back, and beyond all, an occasional volcanic peak may be seen lifting itself in solitary grandeur.

At the mouth of the Guayas River, in Ecuador, there is a dense growth of tropical vegetation. It seems to be a veritable hothouse of nature, where plants and trees wage a desperate war for existence against the vines, mosses and other parasites that attack them. This is the end of such scenes, however, for days and days. It would be difficult to find a more dreary aspect than the coast of South America from the boundary of Ecuador almost to Valparaiso. From the water’s edge to the Andes chain of mountains stretches a yellow and brown desert, unrelieved by a tinge of green, except where irrigation has been employed. At midday all is clear, but in the evening a purple haze covers the whole landscape. It bears a close resemblance to parts of Arizona and New Mexico in general characteristics. Cliffs three hundred to four hundred feet high, and which are scooped out into[23] fantastic shapes, often form the water’s edge. The distant mountains look gloomy and forbidding. It very seldom rains there, perhaps once in six or seven years is a fair average. In other places a generation can almost grow up and pass away without an experience with rain. When it does rain, however, the desertlike plains and slopes immediately spring into life. Where for years there has been nothing but drifting sands appear meadows of nutritious grasses, and flowers and plants spring up in great confusion. Wherever the seeds come from is a mystery, but every nook and corner is soon ablaze with vegetation.

The boats stop at many ports from Ecuador to Chile. These little towns will be found nestling in little hollows at the foot of the hills, or tacked on the hillside. Each one is walled away from the other, and each is a gateway to a fertile valley or rich mining section. Sometimes a narrow gauge railway runs back into the interior, but there are no connections coastwise. The steamer furnishes the only communication with the world beyond, and the arrival of the boat is an event of great importance. Each town has its own specialty. At Guayaquil and Paita many merchants will[24] come aboard with Panama hats, and good-natured bargaining will then be carried on with the passengers. Buying a hat is a tedious matter. The seller does not expect more than about one-third of the price he asks. If the passenger looks indifferent the native will hunt him up and reduce his offer. “How much would the señor give?” “Thirty soles! That would be robbery.” But the ship’s gong strikes and the time of departure is at hand. “Here, señor, is your hat. Muchas gracias. Adios!” The deal is concluded, and you have your hat at the price you offered, if you are shrewd enough to see that a cheaper hat was not substituted at the last minute. Deck traders board the vessel and stay with it for days, doing a good business in almost everything from vegetables and fruits to dry goods, and jewelry. Parrots, monkeys and even mild-eyed ant-eaters are offered the passengers for pets. Passengers join the boat at every stop, and, instead of hat boxes, as American women would be burdened with, the women here all bring on board their bird cages with their noisy occupants. Swarthy Spaniards and the darker-hued natives join the boat, many of them dressed in gay attire, and particularly[25] wearing gaudy neckties and waistcoats. The boat always anchors at some distance from the shore, while passengers and freight are brought out either in lighters or row-boats. At some places a dozen lighters may be filled with freight for the steamer. The ship’s crew bring up from the hold scores of bales and boxes with labels familiar and unfamiliar. International commerce becomes real—almost a thing of flesh and blood. Each sling load brought up from the hold has its own tale to tell, and everyone becomes commercialized. The crowing of roosters at night, the bleating of sheep and bawling of the cattle remind you of a country barnyard at times, for the boat carries its own live stock, which are killed as the conditions of the larder demand. Thus it is that these slow galleons float along the coast past Paita, Pacasmayo, Salaverry, Pisco and the rest of the little ports. Five minutes after the ladder would be lowered the deck would become a floating bazaar.

Guayaquil is the port for the equatorial republic of Ecuador. Quite a business is done there, for more than one-third of the world’s supply of cacao beans, from which our chocolate is made, comes through this port. It is[26] generally infested with more or less fever, and most people prefer to make their stay as short as possible. One of the curious things to attract the traveller’s attention is to see the mules with their legs encased in trousers. This is not due to any excessive modesty on the part of the inhabitants, for children several years old may be seen without as much clothing on. The purpose is to protect the legs of the animals from the bite of the gadfly, which is very numerous here. It was near Guayaquil that Pizarro landed with one hundred and eighty men to conquer the empire of the Incas. The capital of Ecuador, Quito, lies in a saucer-shaped cup at the foot of Mt. Pichincha, with many other lofty peaks in sight. It perhaps retains more of the original characteristics than any other city of South America. It vies with the City of Mexico the distinction of being the oldest city of the Americas. For centuries prior to the coming of the Spaniards it was the capital of one of the branches of the Incas, and Atahualpa used to eat his meals off plates made of solid gold. Hitherto accessible only over a long and difficult mountain trail, which was impassable during half of the year, Quito can now be reached by a railroad—thanks to[27] American enterprise. No less than twenty volcanoes are visible from the track, of which three are active, five dormant and twelve are classed as extinct.

Callao (pronounced Cal-ya-o) is the principal port of Peru. It is always full of steamers and masts and has a general aspect of business. More than a thousand vessels touch here every twelve months. Its history has been exciting and there are many monuments to its heroes. Some warships are generally floating in the harbour. Lima is distant but seven miles from Callao, and it is a ride of only twenty minutes by an excellent electric road of American construction throughout. To the hum of the trolley one is hurried past irrigated fields, beautiful gardens and villas, and Inca ruins many centuries old. As the boats remain at Callao for a day the traveller is able to spend a few hours in the “City of the Kings,” as Pizarro christened it. Lima is a wonderfully interesting city, and its history is full of romance. It preserves in wood and stone the spirit of old Spain as it was transplanted into the New World. Carved balconies, which were patterned after their native Andalusia, still overhang the narrow streets of the Peruvian capital.[28] Up-to-date electric cars whirl past old monastery walls where life has scarcely changed in three centuries. The Limaños are an easy-going, pleasure-loving people, among whom the strenuous life has few disciples. It has been the scene of many revolutions, and the marks of street fighting are numerous. Churches and ecclesiastical institutions abound on every hand, and ecclesiastics are numerous on the streets. The cathedral, in which the sacristan will show the alleged bones of Francisco Pizarro, is a fine specimen of architecture—one of the best in the world. On another corner of the plaza is the passageway from which the conspirators emerged on their way to assassinate the conqueror. The building which was the headquarters of the Inquisition in South America occupies still another site on the plaza.

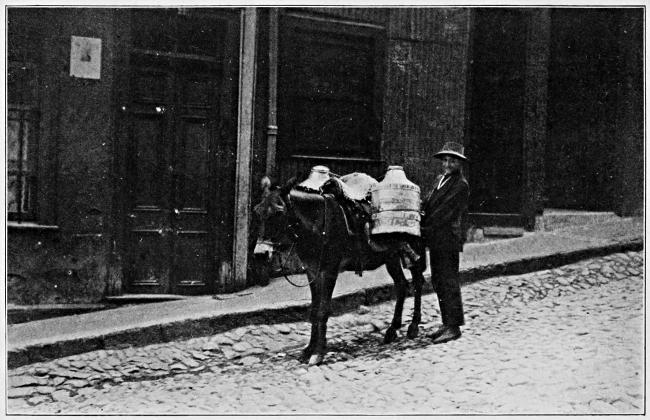

A MILK BOY IN PERU.

Pisco is the next port of importance, and it is situated near a rich and fertile irrigated valley where sugar-cane grows abundantly. It is the port also for the interior towns of Ayacucho and Huancavelica, where numerous rich mines are found. Just a few miles out at sea are the Chincha Islands, from which Peru obtained such a large revenue for the guano[29] found there. These deposits, once considered inexhaustible, because in places they were eighty feet or more in depth, have been almost exhausted. The great wealth received from them and nitrate has been dissipated.

At Mollendo, the last Peruvian port, there is a railway that runs to La Paz, the capital of the inland republic of Bolivia. It is a surf-lashed port where vessels are sometimes unable to land their passengers and freight. In fact the landing is through a “sort of Niagara Gorge gateway of rock, which gives to the mere landing some of the noise and a good deal of the excitement of a rescue at sea.” It takes three days’ travel to reach La Paz from Mollendo, as the train only runs by day. The first stage of the trip, as far as Arequipa, is over an almost trackless desert, where the wind piles the sand up in movable half-moon heaps. The sand-storms of the centuries have covered everything with these whitish particles, and the dusted peaks and hillocks stand out without relief of any kind. The second day brings the traveller to Lake Titicaca, the sacred lake of the Incas, which is crossed by boat, and a side trip will take the traveller to Cuzco, the capital of the Inca confederacy. Lake Titicaca[30] is the highest and one of the most wonderful lakes in the world. It is larger than all the lakes of Switzerland together, and lies in a hollow two and one-half miles above the waters of the ocean. Lying in a peaceful valley, in a scene of desolate grandeur, where the trees are stunted and only a few of the hardiest plants survive, lies La Paz. The City of Peace, its name indicates, but this city has been the scene of turmoil and strife entirely foreign to its name ever since the Spaniards invaded these solitudes. Bolivia is another Tibet—one of the highest inhabited plateaus in the world, as well as one of the richest mineral sections.

In no part of the world, perhaps, is there such an abundance of life in sea and air as along the coast of Peru. Soon after leaving Callao the tedium of the voyage is relieved by the flight of millions upon millions of birds. There are gulls, ducks, cormorants, divers of all kinds and great pelicans with huge pouches under their bills. The sea is as animated as the air, and schools of fish, innumerable in numbers, may be seen darting through the water with their fins showing above its surface. Danger besets them from above and[31] from beneath. The divers poise on wing every few minutes and then drop suddenly into the sea like a flash. For a few seconds they disappear beneath the surface, and then reappear with a fish in their bills. The lumbering and stately pelicans drop with a mighty splash that sends up a dash of spray. These greedy birds continue this foraging process until their pouches are so filled with fish that they are unable to rise out of the water until the load is digested or they disgorge themselves. The seals and sea lions keep themselves as busy as the birds, and constantly display their sinuous and shiny bodies above the surface, as they pursue the fish or come up to breathe.

We passed by the famous guano islands just before nightfall. The air was filled with birds, all of which were flying toward a great island that lifted up its rocky surface above the blue of the sea. At some distance above the sea were the smaller birds, which, at a distance, looked like mere specks against the sky. A little lower were the pelicans flying in single file, and in flocks of from twelve to thirty. They seemed to play the game of “follow the leader,” for if the leader poised his wings or lifted himself higher all did the same. Near[32] the surface were divers, called “pirates” in the local parlance, in flocks of a thousand or more. They sailed along just above the surface of the water and continually altered their formation. With the naked eye the number of birds was myriad, but the telescope showed ten times as many. As far as one could see there was the same multitude of birds, all heading for this one island. The island itself was black with the birds already settled for the night, but each new arrival seemed to find a resting place either on the surface of the rock or in the caves underneath. For countless ages these birds have occupied these sterile volcanic rocks as their resting place, and have deposited the guano which has brought millions of dollars of wealth into the Peruvian treasury. A glimpse of this remarkable bird life shows how the guano has accumulated in such enormous quantities.

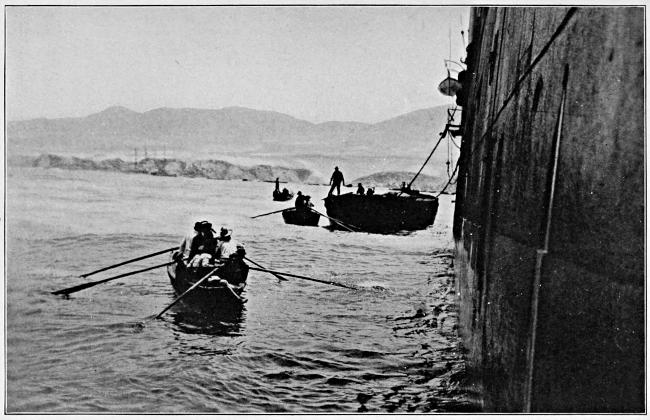

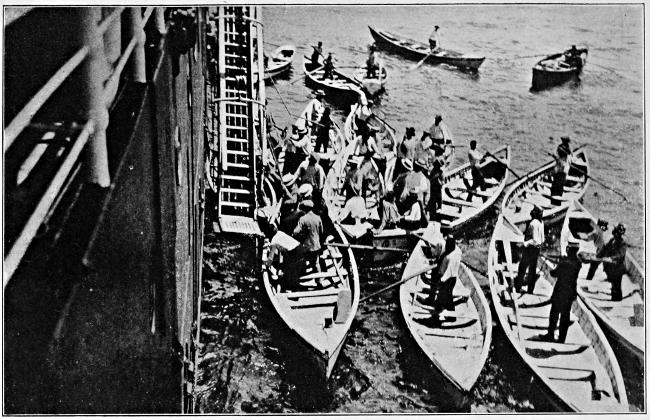

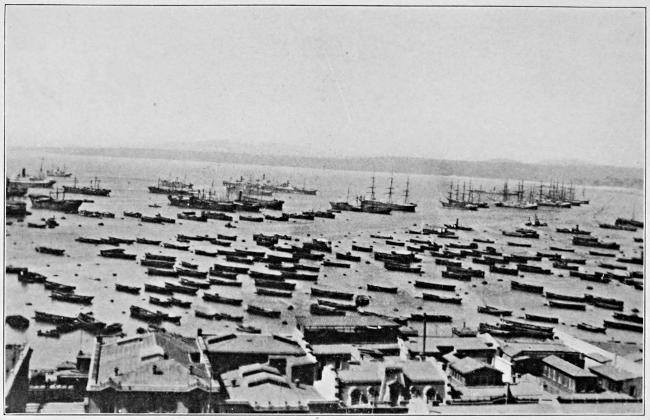

ROW BOATS CROWDING AROUND A STEAMER.

The northern part of Chile contains the dreariest section of this forlorn coast. There are no harbours, and a tremendous surf which rolls half way around the world before it strikes a breakwater dashes into foam upon these beaches. Several prosperous towns are located here as a result of the workings of[33] nature’s laboratories. To reach these ports it is necessary to trust yourself to one of the boatmen, who crowd around the ladder as soon as the vessel drops anchor. Judicious bargaining is always advisable, and never pay the boatman until he has returned you safely to your floating hotel. The boat is guided through the surf with amazing skill, and it is very seldom that an accident occurs. They sometimes crowd each other off, however, in their eagerness to get the best position at the bottom of the ladder and secure the first passengers. But all these men are good swimmers, and the only result is a good wetting and much amusement for the steamer’s passengers who welcome any diversion.

Arica is the first port of importance in Chile at the north. It is only a day’s journey from Mollendo, the last Peruvian port. The Peruvian heaves a sigh when he enters Arica, but there is some hope in it, for he trusts to add this province to Peru’s possessions at some time in the future again. But at Iquique the hope fades, for sovereignty is lost for ever. Although not a large town, Arica has been the scene of several memorable events. It was here that were built the boats which carried[34] the troops for the conquest of Chile. It was at that time a place of some importance among the natives, and the valleys back of it were densely populated and were cultivated by means of irrigation. Sir Francis Drake touched at this place in 1579, and found a collection of Indian huts on the shore. It is supposed to have been founded in 1250 by the Incas. It is like an oasis in the desert to the traveller who has coasted along the shore for days or weeks without seeing vegetation. At the present time it is famous for its oranges. They are grown in the rich valleys that lie behind the rather unattractive and forbidding hills next to the coast, and through the opening in the flat-topped hills one is permitted to catch glimpses of these valleys. Near the coast is a prehistoric cemetery filled with dead bodies, which were embalmed with almost as great skill as the mummies of Egypt.

Arica is a pleasant little place of several thousand inhabitants. There is a handsome little plaza which encloses a plot of shrubbery adorned with morning-glories and purple vine trees. One of the striking features is the brilliant colouring of the houses. There is also a rather imposing parochial church which is[35] painted in the gaudiest colours that I have seen in any country; and it would be hard to duplicate it anywhere, even in Spanish America, a land of rich colouring. It used to be a great market for the skins of the vicuña, which are so beautiful. In late years, however, the skins are becoming less plentiful and the prices have jumped accordingly. The harbour is commodious and well sheltered. Interesting glimpses of native life are afforded by the Indian women coming to town. Some of them ride astride, being almost concealed by the huge panniers containing their market produce. Others trudge along by the side of the animals.

From this city a highway runs into the interior of Peru and Bolivia, which was constructed by the Incas a thousand years ago and has been used ever since. To-day caravans of mules, donkeys and llamas may be seen constantly passing up and down this ancient trail. They bring down ore and take back mining supplies and miscellaneous merchandise. It is known as the “camino real,” and is several hundred miles long. Near here is supposed to be the underground outlet of Lakes Titicaca and Poopo. One argument advanced in favour of this theory is that a certain kind of fresh[36] water fish that abounds in that lake is caught in considerable numbers in the ocean near this town. It has been the scene of several disastrous earthquakes. On August 13th, 1868, it was almost washed away, and many of its inhabitants perished in a tidal wave which came without warning and devastated the coast for a hundred miles. Two United States men-of-war, which were in the harbour at that time, were lifted from their anchorage by waves sixty feet high and carried inland a mile over the roofs of the town. One of the vessels, the Fredonia, was dashed against a ledge of rocks and entirely destroyed, while the other, the Wateree, was left lying in the sand. Everyone on the former boat was lost and about half of the latter. For many years the boat lying on the sand was used as a boarding house for the railway employees.

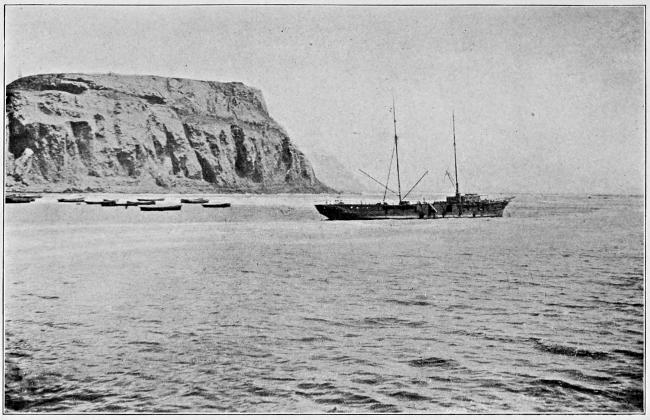

THE HARBOUR OF ARICA.

On June 7th, 1880, Arica was the scene of a furious battle and a terrible massacre. At one end of the town, and directly on the sea front, is a promontory, which rises six hundred feet above the sea almost precipitously. On this rock, which is known as the Morro, the Peruvians had erected a powerful battery to defend the harbour. The Chileans, however,[37] landed a force of four thousand men several miles below at night. In the morning the Peruvians found themselves attacked in the rear with no means of escape. As their guns were pointed to the sea they were useless to defend against those back on the landward side. Although short of small arms and ammunition, the Peruvians made a heroic defence and engaged in a hand-to-hand contest that lasted for an hour. At the end of that time the commander leaped over the precipice into the sea, and his body was crushed to a pulp among the rocks. Several hundred of his soldiers followed him, preferring to die that way to having their throats cut by the Chileans. For months afterward their bodies could be seen lying where they had lodged on the jutting rocks below. It is claimed that seventeen hundred Peruvians were killed, as this was the total strength of the garrison and no prisoners were taken. On a slab near the slope of the rock is an inscription in whitewashed stone, “Viva Battalion No. 4.” It was placed there by the victorious Chileans to commemorate the heroism of the enemy.

Arica is in the province of Tacna, which is the most northerly province in the republic,[38] and is about the size of New Jersey. Agriculture in this province is very limited, and there has not been much of mineral development. There are some veins of copper and lead, and some scattered deposits of nitrate as well that have not been worked. A railroad from Arica runs back to the city of Tacna, the capital, which is one of the oldest railroads in South America. It is quite an important town, and is situated in a valley made fertile by irrigation. A railroad is now being built across the Cordilleras from this city to connect with the Bolivian railways. When that is completed it is believed that this line will be the best one, as it is the shortest, and every traveller is anxious to escape as much of the dust in crossing the desert region as possible. It is only a little over three hundred miles from Arica to La Paz. This road will add to the importance of Arica, for it will be one of the main arteries of commerce from Bolivia to the outside world, but it is not likely to help Tacna any in its growth.

The next province adjoining Tacna is Tarapacá, which is one of the wealthiest sections in the Americas because of its nitrate deposits. It contains the richest nitrate region in the[39] world. From Arica the cliffs rise up almost perpendicularly from the sea for the first day’s journey. Pisagua, the first port as you travel “up” the coast, is a city of about five thousand. This port does not differ much from a mining town in the States. Although considerable shipping is done here, Pisagua fades in importance beside its more important rivals.

“We do not want rain in Iquique.”

This statement was made to me by the manager of the nitrate trust, who lives in that prosperous city of thirty thousand or more inhabitants, and which is one hundred and eleven miles south of Arica. It was the first time I had ever heard of a community that did not desire rainfall. Water used to be brought by boat from more favoured regions, and was peddled through the streets at so much a quart or gallon. At times it is said to have sold as high as two dollars per gallon. A pipe line one hundred and fifty miles long now supplies this necessary liquid to this city, and it is sold by the metre instead of being put up in pint or quart bottles.

A walk through this city on the edge of the sea, with bare, brown and rugged hills for a background, showed not a blade of grass, except[40] on the public squares and in a few diminutive courtyards within the houses, where the hand of man supplied the necessary water for growth. It is little wonder that lawn-mowers are a drug on the market in Iquique. The sun is fierce, and its unrelenting rays, absorbed and reflected by the vast area of desert waste, inflame the air to almost furnace heat. The streets are dusty and the fine particles get into your ears and nostrils, and you can almost taste it on your tongue. Many of the houses have a piazza on top, or a second roof, to break the force of the sun’s rays. The Arturo Prat Square has been made quite attractive, and is ornamented with a very creditable statue of that hero. Business around the shipping quarters is always lively, as it is bound to be where such an enormous export and import trade is carried on. In 1891, during the revolutionary fighting between the Balmacedists and Congressists, the custom house was the scene of a stubborn battle. The town was set on fire and confusion and disorder reigned supreme. At the present time Iquique is an important port and more than one thousand vessels enter it each year.

The dreariness and unattractiveness of the[41] surroundings is hard to describe. Street cars with girls as conductors, good stores, the telephone and other modern conveniences, and even comfortable clubs do not make up for the lack of green vegetation. The groceries are filled with condensed milk from England, sardines from France, sausages from Germany, cheese from Holland, jellies and jam from Britain, and macaroni from Italy. But fresh vegetables and meats are at a premium, and unnatural tastes are developed. Many English live in Iquique. They are great brandy drinkers, and show discrimination “in not exhausting the wealth of the nitrate beds by taking too much soda in their brandy,” as one writer says. Nevertheless the people are happy, for wealth lies at their very doors and rain would cause great loss. By reason of this Iquique has grown until it is second only to Valparaiso in commercial importance. It has grown with a swiftness than can only be compared with our own western towns. In the first days of the saltpetre era nothing went slow and the town spread like magic. Much of the population is a rough one and hard to govern, but the authorities have done well. The battles that have been fought with fortune[42] in Iquique and on this coast have cost many lives and much privation. A few have acquired fortune, but more have not even obtained a modest competence in return for the deprivation and sacrifice endured. Whatever has been gained at the cost of much labour and privation has been fully earned by some one—and perhaps by one who did not reap the reward.

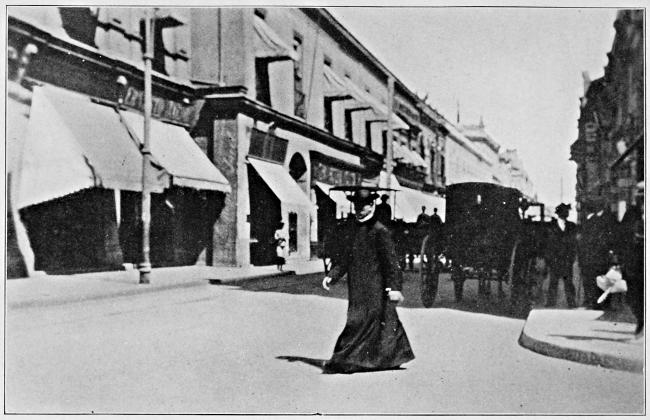

A STREET SCENE, ANTOFAGASTA.

The province of Antofagasta joins that of Tarapacá on the south. Tocopilla is the first port of importance, but Antofagasta, a little over two hundred miles from Iquique, is the principal city. This province is a desert in appearance similar to the other, and this city can boast no advantages over its more northerly rival. Antofagasta is almost on the Tropic of Capricorn, and is in about the same latitude as Rio de Janeiro, on the Atlantic coast. It lies almost at the foot of some hills that are quite high, and is a city of about twenty thousand. The dull-coloured houses can scarcely be distinguished from the sombre hills at a distance. The dust is anything but pleasant. A great deal of nitrate and some copper are shipped from Antofagasta. There are several small wharves, but everything has[43] to be transferred to lighters. The harbour is a wretched roadstead and, to get ashore, one has to brave a lashing surf. The pride of the city is a little plaza, where considerable coaxing has caused a little evidence of green from the grass and a few trees. A narrow gauge railroad, two feet and six inches in width, runs from here to La Paz, and a great deal of freight is transshipped to Bolivian towns.

The province of Atacama comes next, which does not differ much in physical characteristics from the three previously named. In some of the valleys, where water can be secured for irrigation, a little agriculture is attempted. There are also a number of minerals to be found, but not so much as in Tarapacá and Antofagasta. Caldera, the principal port, is two hundred and seven miles from Antofagasta, and has a well sheltered bay. The oldest railroad in South America connects this port with Copiapó, the capital of the province. This city is situated in a fertile valley on the banks of a river of the same name. It is an old and quite important town, and has a number of educational institutions. It will soon be connected with Santiago by the longitudinal railway.

The last of the northern provinces is that of Coquimbo. This province is really at the end of the dry zone, and there are a number of rich valleys where the land is fertile and agriculture flourishes. It is a mining province as well, and a great deal of mineral wealth has been discovered. Guayacan is a port, but the principal port is Coquimbo, which is only a couple of hundred miles from Valparaiso. It has a population of probably ten thousand. The city extends along the bay in an irregular manner for some distance. The capital of the province is La Serena, and it is only a few miles from Coquimbo. There is nothing especially in its favour, although an attractive little city, but it is a relief from the dreary places farther north which have been mentioned.

COQUIMBO, A TYPICAL WEST COAST TOWN.

Every one going this way is bound for Valparaiso. The voyager, who has journeyed twenty-six hundred miles along the Pacific coast, hails with delight the beautiful half-moon bay in which that city is located. He welcomes the splash of the anchor, which means a speedy transfer to the shore and the comforts of a good hotel. Many disasters have been recorded in this bay. In the winter terrific storms arise, and steamers oftentimes lift[45] their anchors and steam out into the open sea for safety. The largest steamers are tossed about like eggshells, while the buoys bob around like water-sprites. The enthusiastic Chilean loves to compare it with the Bay of Naples. But it is not Naples. The waters are not so blue, nor the skies as perfect, but it has a charm all its own. A row boat or launch quickly transfers the traveller to the landing steps, and courteous officials promptly pass the baggage. Then a short ride in a rickety carriage, and the doors of the Royal Hotel hospitably open to receive the guests.

Val-paraiso means the “Vale of Paradise,” and it is the name of both a province and a city. The name is so incongruous on this unattractive shore as to cause a smile, for the location of Valparaiso does not merit any such appellation. It was so named after a little town in Spain, which was the home of Juan de Saavedra, the man who captured the Indian village located at this point in 1536. There is only a narrow strip of land between the bay and the barren hills behind it, which, in places, rise up to a thousand or fifteen hundred feet in height. At one place it is wide enough for only two streets, which are very close together. At other places this ledge creeps back farther, but nowhere does the gap between sea and hills exceed half a mile, and a part of this has been reclaimed from the sea. Through the centre of this level space runs Victoria Street, which follows the coast line the entire length of the[47] city and is several miles in length. It is the main commercial street, and is lined with business houses, public buildings and even private residences.

AN “ASCENSOR” IN VALPARAISO.

It used to be that all of the city was built on this narrow strip of land. Little by little, however, the city has crept up the side of the hills, and the streets rise in terraces one above the other. On the edges of the cliffs in many places the poorer classes have built for themselves dwellings of the rudest kind from all sorts of debris. Some of these are perched upon almost inaccessible rocks, and are propped up with wooden supports. On the extreme upper part of the rock has been built the real residence quarter, and many fine homes are found there. It is reached by steep and winding roads, which tire the pedestrian not used to them; but there are a dozen inclined elevators, or “ascensors,” as they are called in Valparaiso, which carry the passenger to the upper heights for a very small sum. Up the steep roadway the poor horses may be seen drawing their loads, while the drivers beat them and vociferously berate them with their tongues.

From the heights one has a magnificent view[48] of the bay, which is like a half-moon, and is one of the prettiest bays in the world. It has a northern exposure, however, and is subject to terrific storms in the winter season, which lash the seas into a fury and the waves beat upon the sea front with destructive force. It is still to all extents and purposes an open roadstead, although plans have been drawn for a breakwater to provide a sheltered harbour. The drawback has been that the bay is very deep only a short distance from shore, and the problem of building such a protection is a difficult one. The surface of the bay is always dotted with vessels from almost every quarter of the globe. One can at any time see the flags of a half dozen or more different nations floating from the mastheads. Then there are hundreds of small lighters which are used to carry the freight between vessel and shore, as no docks have been constructed at which vessels can unload. In the far distance may be seen, on a clear day, the backbone of the continent, the Andes, with its serrated ridges and snowy summits glistening in the sunlight. The hoary head of Aconcagua, the highest peak of the Cordilleras, can easily be distinguished from the others by reason of its superior height.

Next to San Francisco, Valparaiso is the most important port on the eastern shores of the Pacific. This city of two hundred thousand has as much commerce as the average town of double that size, as it is the port for Santiago and the greater part of Chile. A business-like character is impressed upon the entire city. Here live the men who design and carry out the vast nitrate and mining enterprises of northern Chile, and practically all business, except that of politics, is managed from this city. The docks and warehouses are at all times busy places, and are crowded with boxes and bales from almost every commercial nation. Banditti-like rotos drive carts and wagons filled with merchandise. One of the first sights after being set down on the landing-stage is the two-wheeled dray of Valparaiso. It is drawn by two or three wiry and sweating horses, on the back of one of which rides the driver, who lashes the horses unmercifully. The ridden horse is hitched by a trace just outside the shafts, and he is trained to push at the shaft with his shoulder, or pull at right angles when the occasion arises, and in every way is as clever as any Texas bronco. One of these drays with the driver lashing his team[50] might well figure on the escutcheon of this city.

The “U. S.” mark is less frequently seen in Valparaiso than that of Hamburg or London, for the United States has not become such an exporting country of manufactured products as those commercial nations of the older world; nor is the Yankee in flesh and blood. The predominance of the British is shown by the prevalence of the English language. Nearly every one engaged in business has at least a slight acquaintance with that tongue. One can not go far without crossing the path of some ruddy Briton or voluble Irishman. Many of the best stores bear English names, and one will see the same goods displayed as in New York or London. In fact it is more predominantly English in appearance than any other city of South America. There are cafés where they meet to drink their “half-and-half” or other beverages, and there is a club where the Times, Punch, and other favourites can be read. It is said that the foreign population almost equals the native in numbers. Only a small part of this foreign element is English, as there are many Italians, Germans and French, but the English are the bankers and tradesmen,[51] and have impressed their characteristics more forcibly upon the city than the other nations. There are amusements in plenty, for there are clubs, concerts and an abundance of theatres to provide recreation as a relaxation from the strenuous life. There are tennis grounds, football fields and a golf course at Viña. There are many monuments over the city in the plazas and on the new alameda, erected to the nation’s heroes, and one to William Wheelwright, the American who did so much to aid Chile in developing her transportation facilities. The naval school, which crowns one of the hills, is one of the most attractive places in Valparaiso, and provides one of the finest views of the bay and surrounding hills.

“One of the great advantages of life in Valparaiso,” says Arthur Ruhl in “The Other Americans,” “is the absence of a professional fire department. The glorious privilege of fighting fires is appropriated by the élite, who organize themselves into clubs, with much the same social functions as the Seventh Regiment and Squadron A in New York, wear ponderous helmets and march in procession in great style whenever they get a chance. One comes upon these bomberos practising in the evening, on[52] the Avenida, for instance, in store clothes and absent-mindedly puffing cigarettes, getting a stream on an imaginary blaze. In any emergency they perform much the same duties as our militia.

“It is the delightful privilege of the bombero to drop his work whenever the alarm is given, dash from his office to the blaze, and there man hose-lines, smash windows, chop down partitions, and indulge to the fullest one of the keenest primordial emotions of man. Inasmuch as buildings are seldom more than two or three stories in height and built of masonry, there is comparatively little danger of a large conflagration, and the average of one fire in four days is ‘just about right,’ as one of my Valparaiso acquaintances explained, ‘to give a man exercise.’ Their only unhappiness, he said, was that there were about fifteen hundred firemen in town, and they were getting so expert that what one could call a really ‘good’ fire was almost unknown.”

Like its commercial rival, San Francisco, Valparaiso suffered from a destructive earthquake in 1906. Slight quakes are quite common in this city, but the inhabitants do not seem to fear them, and go along the even tenor[53] of their way as though such a thing as an earthquake was unknown. In one year as many as thirty-five shocks have been recorded, but the one mentioned above is the only one for a half century or more in which any lives were lost. In fact Valparaiso has had its full share of troubles and vicissitudes of all kinds. It was captured and sacked three times by buccaneers, twice by the British and once by a Dutch pirate. It has suffered severely from earthquake shocks on half a dozen different occasions, was destroyed by fire in 1858, bombarded by the Spanish fleet in 1866, and much property was destroyed in the Balmaceda revolution a little later. Few cities in the New World have had a career so troubled and diversified.

The most disastrous experience in the history of Valparaiso occurred in 1906. On the 16th of August of that year, only four months after the destruction of San Francisco, the greater part of the city was destroyed by an earthquake and the fire that followed. The day had been unusually calm and pleasant. About eight o’clock in the evening the first earthquake shock was felt, which was almost immediately followed by others. The whole city[54] seemed to swing backward and forwards; then came a sudden jolt, and whole rows of buildings fell with a terrific crash. The electric light wires snapped, and gas and water mains were broken. The city was left in intense darkness, which was rendered all the more horrible by the shrieks of the injured and terrified inhabitants. Fires soon started which, fanned by a strong wind, soon became conflagrations. Between the fires and earthquake a large proportion of the lower town was completely destroyed, but the upper town was practically uninjured. Many of the better-built business houses withstood the earth’s tremblings, and the wind blew the flames in the opposite direction.

The authorities acted promptly in the matter, so that patrols of troops and armed citizens were soon on guard. The progress of the fire was impeded by the use of dynamite. Appeals for help were sent to Santiago and other cities, which were responded to as promptly as possible. There was necessarily some delay, for telegraph lines and the railroads had likewise suffered. The shocks continued for the two following days at irregular intervals, which likewise interfered with the work of[55] cleaning up the city. A terrific downpour of rain also added to the confusion of the first night, for the vivid flashes of lightning and the clanging of the fire-bells made it a night not easily forgotten by the inhabitants. The killed and injured numbered at least three thousand persons. But fifty thousand or more were rendered homeless. Thousands of these were camped on the barren hills above the city, and thousands more were cared for by boats in the bay.

Strangely enough no damage was done to the shipping in the bay. The destruction was not confined to Valparaiso alone, but extended inland as far as Los Andes, and many of the small inland cities near Valparaiso suffered more or less damage. The property loss in Valparaiso has been estimated at one hundred million dollars. Like San Francisco, however, a new Valparaiso is arising which will be superior to the old. The greater part of the destroyed district has been rebuilt in a better and more enduring manner. The national government has advanced large sums of money to the municipality, which, in turn, has given it under certain conditions to those who suffered losses. To-day in the business section of Valparaiso[56] it would be almost impossible, after only five years, to find evidence of this disastrous earthquake, but a little farther out its handiwork can quickly be traced.

There is a quaint side to life in Valparaiso. A visit to the market reveals many things of interest. One will first be impressed by the fine fruits of Chile, for nowhere in the world can one find more delicious pears, peaches and plums. The marketers bring their produce in huge two-wheeled carts drawn by the slow-moving ox. The stalls presided over by men and women fill every available inch of space, until it is almost impossible to force one’s way through. Everywhere are groups bargaining over fruits, vegetables or household articles, for these people dearly love a bargain. Many show by their faces a tinge of the Indian blood that runs in their veins.

A CHICKEN PEDDLER, VALPARAISO.

The peripatetic merchants, who carry supplies from door to door, come to the market for their stock in trade. It is invariably carried on the back of a donkey or mule, as it is difficult to draw a loaded wagon up the steep ascents. Their quaint cries may be heard in almost any part of the city during the morning hours. As a rule this merchant carries only[57] one article, or possibly two or three, if it is vegetables. The chicken peddler has built little coops for his birds which take the place of a saddle. It is interesting to watch him gesticulate and praise the excellence of his fowls to the good housewife, or the servant who comes out in answer to his warning cry. The scissors-grinder and dealers in notions swell the list of perigrinating business men who make the streets vocal with their calls. The milkman carries the milk in cans swung over the back of his mule or donkey, or else drives the cows themselves from door to door.

“Leche de las burras y vacas,” meaning donkey’s and cow’s milk, was the cry that reached my ears one morning in Valparaiso. On looking around I saw a man leading two donkey mares and three cows through the streets. Each donkey mare was closely followed by its pretty but comical little colt. This is a custom imported from Spain and Italy, where goats are also taken from door to door and oftentimes up three or four flights of stairs to be milked. It might even be possible to find a milkman with donkeys, cows and goats in his collection, so that a regular department store variety of milk could be provided his[58] customers. Add to these the camel and reindeer, and you have the sources of the world’s milk supply. Donkey’s milk is used a great deal for babies in South America, as it is considered better for them than the milk of either cows or goats. Milk delivered in this way does not need a sterilized label upon it, or a certificate from the department of health. Furthermore, there is very little danger of adulteration. The housekeeper reaps the benefit of this style of milk delivery, but it must be a slow and costly method for the dairyman. It is another evidence that primitiveness has not entirely disappeared from Chile.

A VENDER OF DONKEY’S MILK, VALPARAISO.

One other peculiar feature of life in Valparaiso is that the conductors on all the street cars are women. This innovation was introduced in the time of war with Peru, when men were hard to secure for that work. They did the work so well that they have been employed continuously ever since. It can not be said of them that they are especially attractive, or even look very jaunty in their uniforms of blue surmounted by a sailor hat. The fares are the cheapest I have ever found. The cars are all double-decked. For two cents one can ride inside, and it costs only half that rate to ride[59] on the upper deck, which is a far better way to see the city. The service is good, and there are more than twenty-five miles of trolley in and about the city. The electric current for this as well as lighting is generated by water power a few miles north of the city, where a huge dam has been built across a stream.

A night view of Valparaiso from the bay is delightful. The many electric lamps in all parts of the city illuminate the otherwise dark shadows, and are reflected in the waters near the shore. Here and there move streaks of light in the lower town, as the electric cars dash along from one end of the city to the other; similar lines of light move up and down in a dozen places, as the “ascensors” carry their loads between the upper and lower town. At such times Valparaiso looks like a city of enchantment, a chosen bit from fairyland.

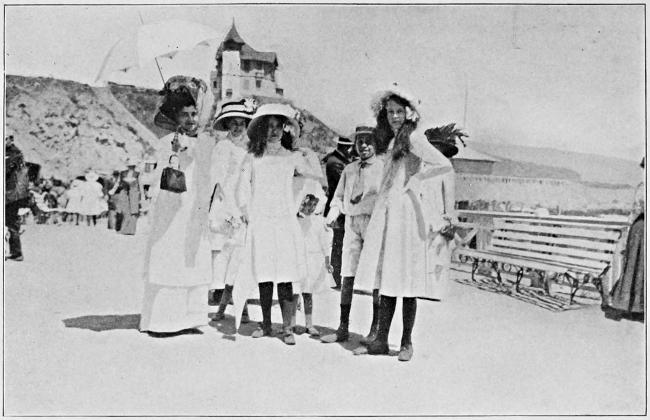

A trolley line leads out to the aristocratic suburb of Viña del Mar, where the rich people of Chile also have their summer residences. There are some beautiful homes in this city, of splendid architecture and surrounded by luxuriant foliage. In these villas the wearied and worried man of business finds rest after business hours. For a few months in the summer[60] this resort is the centre of the social life of the republic, and the hotel is so crowded that it is difficult to secure accommodation, unless arranged for beforehand. There are delightful drives, when not too dusty, and then there are tennis courts, golf links, polo grounds and other places of recreation. A fine club building has been erected, where the devotees of games of chance can find the alluring games that their natures seem to crave. At Miramar is a small bathing resort, but it is extremely dangerous, for just a short distance from shore the bottom seems to drop to a great depth. It is used principally as a place for promenades and dress show for the society folks, and every day a long line of carriages wend their way out to that pleasant little bit of beach.

AN ATTRACTIVE HOME, VIÑA DEL MAR.

The great attraction of Viña, however, is the race course. Sunday is, of course, the gala day, and the race course is crowded with lovers of the sport. The people of Chile have passed the bull-fight period in civilization, for the bull-fight and lottery have both been banished by statutory enactment, and the horse races have taken their place. They vie with the residents of Buenos Aires in their devotion to this sport. The residents entertain house parties on that[61] day and all attend the track. They become very enthusiastic, and few who have the money neglect an opportunity to stake it on the horses, for all are posted on the records of the various animals listed in the races, and each one has his or her favourite.

The province of Valparaiso does not extend quite to the Cordilleras, but it does reach out several hundred miles into the Pacific. Some four hundred miles west of Valparaiso lies the island of Juan Fernandez, which is generally known among English-speaking people as Robinson Crusoe’s Island.

Thus runs the old nursery rhyme with which all of us are familiar. There are few reading people, young or old, who have not read that fascinating tale of adventure, written by Daniel Defoe, which depicts the adventures of Robinson Crusoe. And yet, perhaps, there are not so many who are familiar with the location of the island which Defoe pretends to describe.

The island of Juan Fernandez, generally[62] known among Chileans as Mas-a-Tierra, is a great mass of rock almost twelve miles long by seven miles wide, a large part of which is as barren as a desert. One side, however, where fruits grow and the wild sheep and goats find their sustenance, is covered with a luxuriant vegetation. It is in a desolate location, for it is away from the trade routes and there are few vessels that pass that way. The fishing boats that ply between Valparaiso and the island keep up communication with the mainland. The waters of the Pacific teem with fish, and the fishermen have found the little bays of this small island profitable waters for their trade. It is a great lobster-fishing ground also, and the largest lobsters by far that I ever have seen were caught at this island.