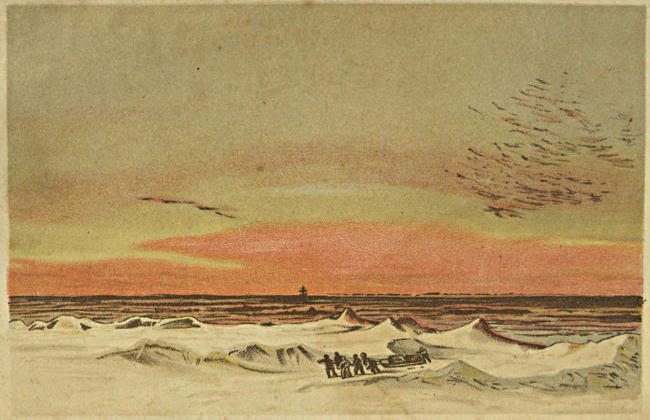

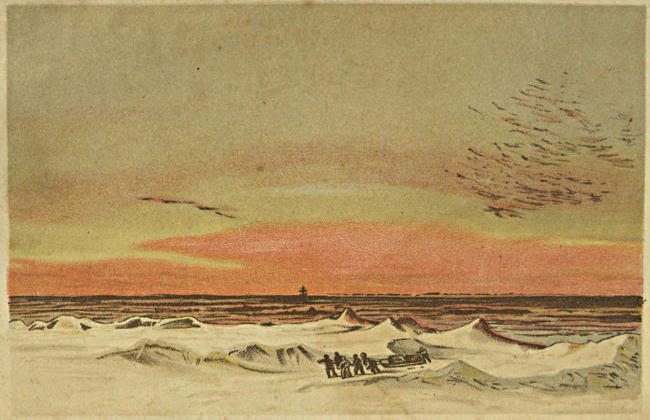

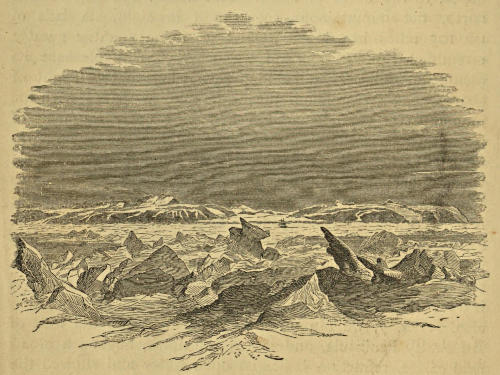

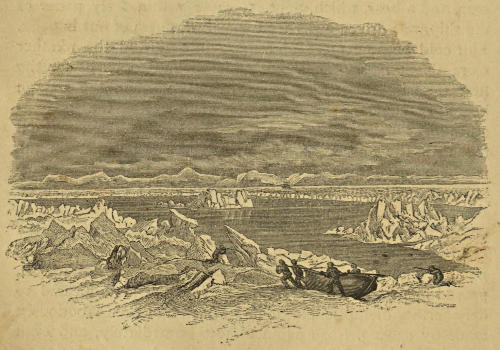

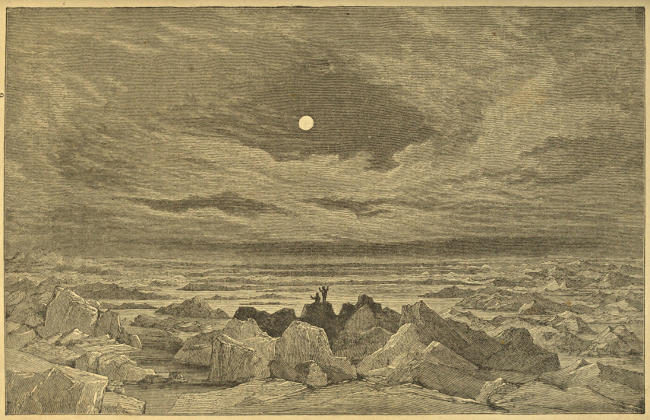

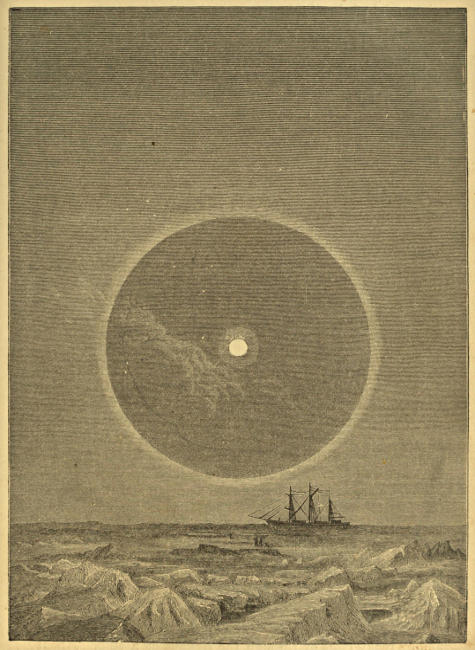

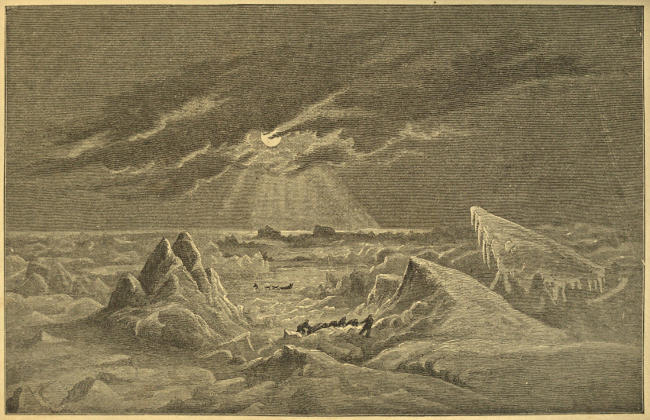

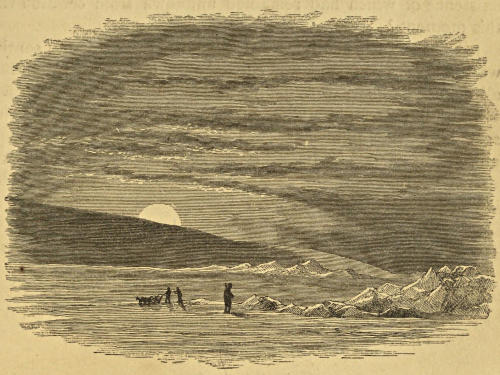

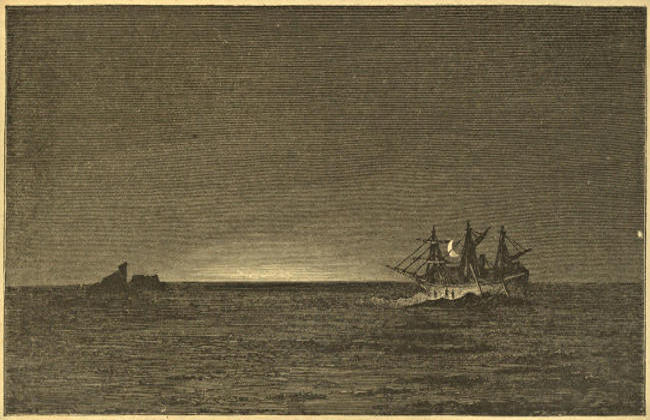

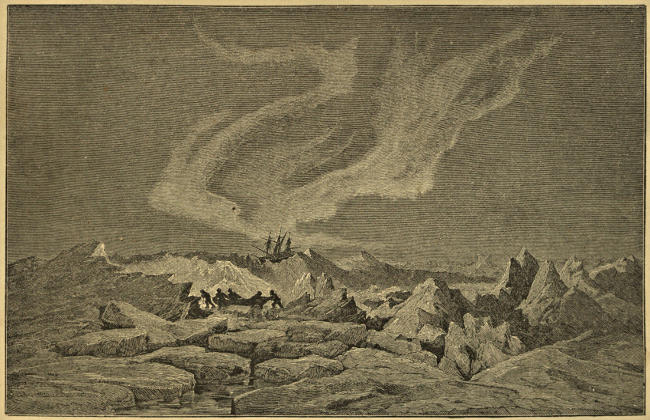

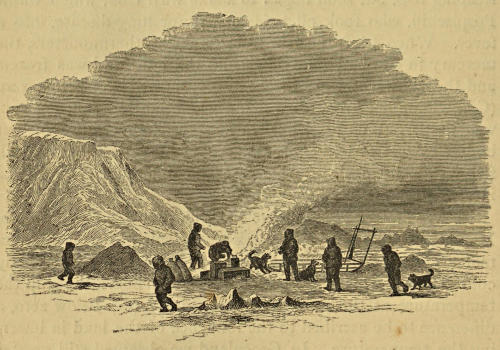

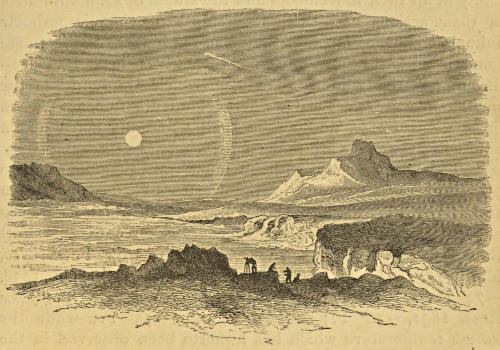

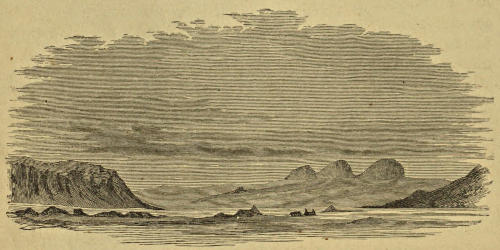

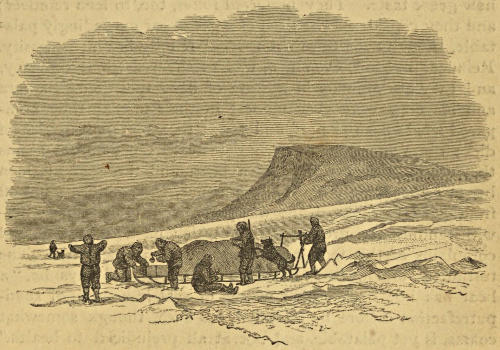

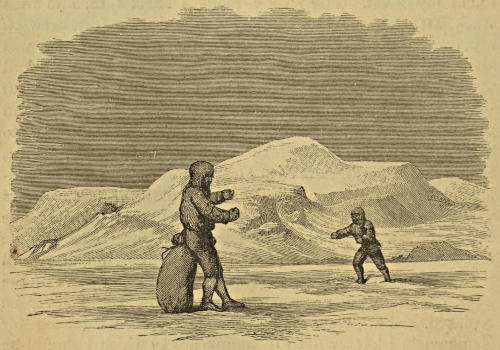

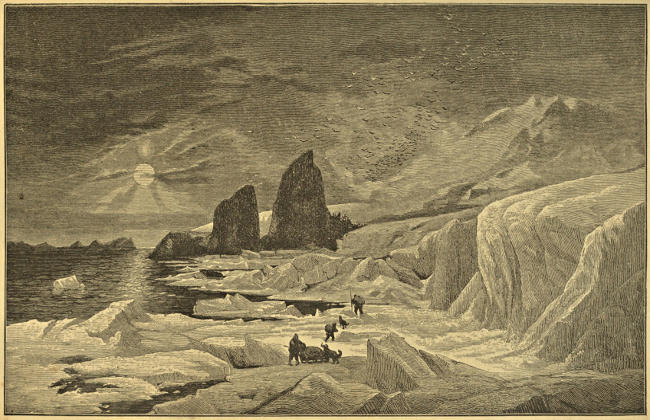

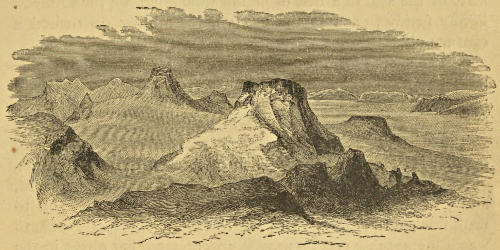

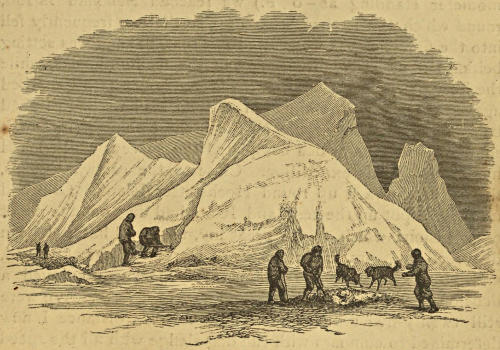

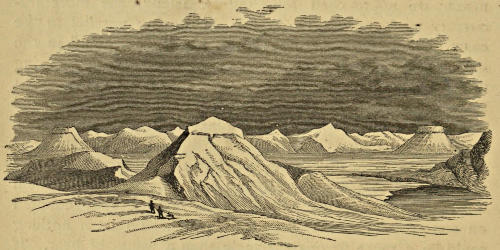

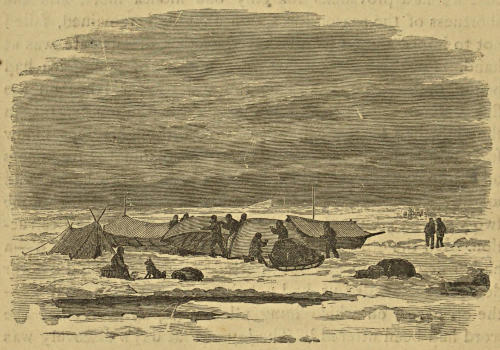

TWILIGHT AT MIDDAY, FEBRUARY 1874.

TWILIGHT AT MIDDAY, FEBRUARY 1874.

NARRATIVE OF THE DISCOVERIES

OF THE AUSTRIAN SHIP “TEGETTHOFF”

IN THE YEARS 1872-1874.

BY

JULIUS PAYER,

ONE OF THE COMMANDERS OF THE EXPEDITION.

WITH MAPS AND NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS FROM DRAWINGS

BY THE AUTHOR.

Translated from the German, with the Author’s Approbation.

NEW YORK:

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY,

549 AND 551 BROADWAY.

1877.

In laying this book before the Public I desire, in the first instance, to acknowledge without reserve my sense of the great merits of my colleague, Lieutenant Weyprecht. The reader of the following pages will learn with what unwearied, though fruitless, energy he struggled to free the Tegetthoff from her icy prison, and what dauntless courage and unfailing command of resources he displayed in our hazardous retreat from the abandoned ship, till the moment of our happy rescue. The order and discipline maintained on board ship, and in the terrible march over the Frozen Ocean, as well as in the perilous boat voyage after leaving the ice-barrier, were mainly due to his distinguished abilities. He had supreme command of the expedition, as long as its duties were strictly nautical; when the operations of sledging and surveying began, I had the responsibility of a separate and independent command.

Nor ought I to be slow to pay my tribute of respect to the perseverance and constant self-denial of Lieutenant Brosch and Midshipman Orel. It would be difficult to determine, whether they shone more as officers of the ship, or as observers of scientific phenomena. The highly important duty of managing the stores and provisions was discharged also by Lieutenant Brosch with a conscientiousness that secured the confidence of all.

To the watchful skill of Dr. Kepes we owed it, that the health and constitution of the members of the expedition suffered so little from all their hardships and privations.

The conduct of the crew was on the whole praiseworthy. Their obedience to command, their perseverance and resolution shown on every occasion, will be cited as an example of what these virtues and qualities can achieve amid the most appalling dangers and trials.

With regard to my narrative, I make no claim for it founded on its literary excellence; rather I sue for indulgence to its manifold shortcomings. I have not written for the man of science, though I have not shunned a few scientific details. Nor have I aimed at presenting a record, which might be profitable to those who shall follow us in the same career of discovery, though some hints will be found in my pages which will not be without their use to those who may consult them for information and guidance. Rather I have endeavoured to narrate our sufferings, adventures, and discoveries in a manner which shall be interesting to the general reader who reads to amuse himself.

The magnetical and meteorological observations, so carefully taken and tabulated by Weyprecht, Brosch, and Orel, together with the sketches of the Fauna of the Frozen Ocean, drawn by myself from the collection of Dr. Kepes, were presented to the Imperial Academy of Sciences of Vienna, and will in due time be published under the auspices of that august body.

It will be interesting to English readers to learn a few particulars concerning the two leaders of the Austrian North Polar Expeditions. Carl Weyprecht was born in Hesse-Darmstadt in 1838, and in his eighteenth year entered the Austrian navy. Ten years afterwards he was present at the action between the Austrian and Italian fleets at Lissa—July 20, 1866; was promoted to the rank of lieutenant of the second class, and decorated with the order of the Iron Cross in recognition of his services in that battle. It was shortly after this, that Weyprecht volunteered to take the command of a small vessel, manned by only four seamen, which was to sail from Hammerfest to explore the Arctic Ocean. This dauntless offer was the basis of the first German North Polar expedition. When, however, permission to act in this capacity was obtained, Lieutenant Weyprecht was serving on board the Austrian frigate Elizabeth, which formed one of the squadron sent by the Austrian Government to bring home the body of the ill-fated Maximilian. Immediately on his return to Europe he repaired to Gotha, eager to place his services at the command of the expedition which had meantime been planned by Petermann and a committee of patrons of Arctic exploration. But unhappily, just at this moment his health, which had suffered from fever caught at New Orleans, failed, and the command of the expedition, known as the first German North Polar Expedition (May 24-October 10, 1868), was undertaken by Captain Koldewey. It was only in 1871 that he recovered his health, and in the June of that year[viii] began, in the Isbjörn, his life of Arctic experience and discovery. In the following year, 1872, he was appointed to the naval command of the expedition which sailed in the Tegetthoff, whose strange and eventful history is recorded in the following pages.

His companion and colleague, Julius Payer, was born at Schönau in Teplitz, Bohemia, in 1841, and received his education as a soldier at the Wiener-Neustadt Military Academy, 1856-59, where General Sonnklar was his teacher in geographical science, and early imbued his mind with a love for the grandeurs of the glacier world. With the rank of “Ober-Lieutenant” he served in the campaign of 1866 in Italy, and was decorated for his distinguished services at the battle of Custozza. Afterwards, while serving with his regiment in Tyrol, he gained great celebrity as one of the most successful Alpine climbers, and turned his experience as a mountaineer to profit in his surveys of the Orteler Alps and glaciers. Payer gained his first experience as an Arctic discoverer in the second German North Polar Expedition, under Koldewey and Hegemann—June 15, 1869-Sept. 11, 1870. His services during that expedition were of a most distinguished character. He shared in the most important discoveries which were then made, specially those of König Wilhelm’s Land, and of the noble Franz-Josef Fjord. He acquired in East Greenland the experience of sledging, which was of such eminent use in his explorations of the great discovery of the Tegetthoff Expedition—Kaiser Franz-Joseph Land. He shines too as an author in his descriptions of Greenland scenes, in the Second German North Polar Voyage, published in 1874 by Brockhaus of Leipzig, and partially reproduced in an English translation by the Rev. L. Mercier and Mr. H. W. Bates. For these services, on the return of the expedition, he was again decorated, receiving the order of the Iron Crown.

In the voyage of the Isbjörn, June 21-Oct. 4, 1871, we find him associated with Weyprecht in the pioneering voyage described in the earlier part of this work, and lastly as joint commander of the renowned Tegetthoff expedition, June, 1872-September, 1874.

The Gold Medals entrusted to the Royal Geographical Society were awarded in 1875: the Founder’s Medal to Lieutenant Weyprecht, and the Patron’s Medal to Lieutenant Julius Payer.

As these pages are passing through the Press, the country has been deeply moved by the unexpected intelligence of the return of the Arctic Expedition. Gratulations on its safe and happy return have been unanimously and eagerly expressed by all the organs of public opinion. Disappointment, however, has, we fear, fallen on many minds as, after the first feelings of joy at the safe arrival of the officers and crews of the Alert and Discovery, they read the brief telegraphic summary sent by Captain Nares: “Pole impracticable,”—“No land to northward.” Popular enthusiasm looked rather for the conquest of the Pole; expected, perhaps, to read, one day, that the Union Jack had been hoisted there, to commemorate the triumph of England’s perseverance at last rewarded. Few, we apprehend, would pass through the chill of these two clauses of the message to mark the hope contained in the third—“voyage otherwise successful.” In what special respects the success proclaimed was achieved, we must patiently wait for a future record to reveal; but while awaiting the history which no doubt will be written to justify and prove this announcement, let us exercise our loyal belief in the skill and courage of our countrymen, and feel persuaded that what men could do under their circumstances no doubt was done by them.

The interest which will be excited afresh in Arctic discovery and adventure, will doubtless sharpen the interest in the volumes which record the fortunes of the Austrian expedition; and we venture to affirm—without undue partiality—that, though the history of Arctic exploration and discovery abounds in records of lofty resolution and patient endurance of almost incredible hardships, the narrative of the voyage of the Tegetthoff will be found to fall below none in these high qualities. The mere destiny of the vessel itself equals, if it does not exceed, in the element of the marvellous, anything[x] which has before been recorded. Surely this is borne out when we think, that on August 20, 1872, the Tegetthoff was beset off the coast of Novaya Zemlya; remained a fast prisoner in the ice, spite of all the efforts made by her officers and crew to release her; drifted during the autumn and the terrible winter of 1872—amid profound darkness—whither they knew not; drifted to the 30th of August in the following year (1873), till, as if by magic, the mists lifted, and lo! a high, bold, rocky coast—lat. 79° 43′ E., long. 59° 33′—loomed out of the fog straight ahead of them. Close to this land—which could be visited with safety only twice, on the 1st and 3rd of November of that year—the ship remained still fast bound in the ice. Not till the winter of 1873 had passed, and the sun had again returned, was it possible to explore the land, which had been so marvellously discovered. On the 10th of March, 1874, the sledge journeys commenced, and terminated May 3rd, after 450 miles had been passed over, and the surveys and explorations completed, which enabled Payer to write the description of Kaiser Franz-Josef Land (pp. 258-270), which shows that other still undefined lands, with an archipelago of islands, have been added to the geography of the earth.

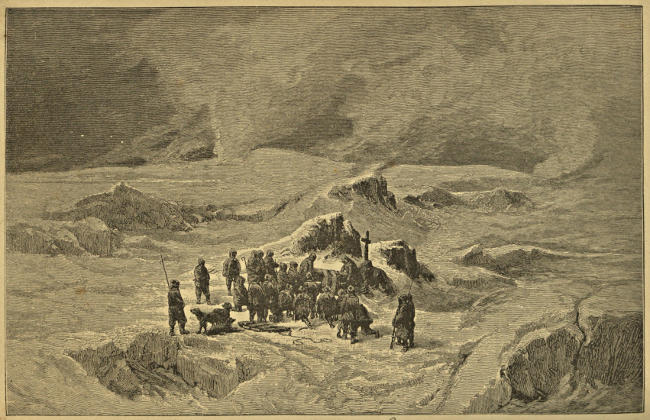

But the perils of the expedition did not end here. On the 20th of August, 1874, it was resolved to abandon the Tegetthoff in the ice, and to return in sledges and boats to Europe. Captain Nares tells us, in his telegraphic despatch, that the sledging parties of the Alert and Discovery compassed on an average one-and-a-quarter mile per day on the terrible “Sea of Ancient Ice,” and discovered, after the experience gained in seventy miles passed under these conditions, that the “Pole was impracticable.” If our readers wish to have a conception of the toils and perils of the Austrian sledge parties on their return from the Tegetthoff let them mark the single image presented to the mind by the statement (p. 364):—“After the lapse of two months of indescribable efforts, the distance between us and the ship was not more than nine English miles.” Had the ice on the Novaya Zemlya seas remained as obstinate as it seems to[xi] have done in the new desolation, the “Sea of Ancient Ice,” escape would have been as impossible to the Tegetthoff’s crew, as advance towards the Pole was to the sledge parties of our last Arctic expedition. But fortunately, soon after, “leads” opened out in the ice; the boats were launched, and after about another month of alternate rowing and sledging, the ice barrier was happily reached in the unusually high latitude 77° 40′; and the brave men who three months before had left the Tegetthoff were saved.

This is perhaps the most marked analogy between the perils of the two expeditions; so far as those of our own are yet known. But the scientific conclusions of Lieutenant Payer, as set forth in the general Introduction to his narrative, strikingly harmonize with the actual discoveries of the Alert and Discovery. Already it is authoritatively announced, that there is no open Polar Sea; that this hypothesis is as baseless as the existence of President’s Land. In the fourth chapter of that Introduction (pp. 25-31), our author has analysed with great sagacity the various theories on which that hypothesis was made to rest, working up to the conclusion, that no such sea exists. The demonstration of experience now takes the place of enlightened argument and opinion; fact and theory are here at one.

Nor can we forbear to direct attention to another statement in the same chapter. Let our readers mark the prophetic spirit of the following passage: “All the changes and phenomena of this mighty network lead us to infer the existence of frozen seas up to the Pole itself; and according to my own experience, gained in three expeditions, I consider that the states of the ice between 82° and 90° N. L. will not essentially differ from those which have been observed south of latitude 82°; I incline rather to the belief that they will be found worse instead of better” (p. 30). And “worse instead of better” they have been found, as we cannot doubt, when we weigh the ominous significance of the designation the “Sea of Ancient Ice.”

History may or may not verify the position which the telegram so briefly resumes—“The Pole impracticable.”[xii] Impracticable no doubt it was, if the condition of the ice seen by our expedition in that awful sea be its normal condition. All that it was possible for men to dare and achieve, England will feel that her officers and sailors dared and achieved under the circumstances they encountered. It may be, that later experience will show, that even that Sea may present to future explorers an aspect less tremendous; yea, that in some seasons, which science may yet predict, when her theories of the sun-spots are matured and formulated, open water will be found, as perhaps it was found in the year of the expedition of the Polaris, where the heroic sledging parties from the Alert and Discovery saw nothing and found nothing, but piled-up barriers of ice rising to the height of 150 feet.

It would be idle to predict, in the face of these results, that the Pole shall yet be reached. Any confident prediction in this spirit would, at the present moment, be singularly inopportune, as well as unwise. But despair would be equally unjustifiable, while its influence would be most hurtful and depressing, especially if Arctic exploration and the attainment of the Pole were supposed to be identical propositions. There are two things: reaching the North Pole, and the exploration of the Polar region. If the former appeals more to the imagination, and readily calls forth the emotions which are fed by the love of the marvellous, the latter enlists the sympathies of those who take a broader view of the necessities of Arctic exploration. These have found a powerful representative in one whose services entitle him to speak with authority, in the naval chief of the Tegetthoff expedition. At a meeting of the German Scientific and Medical Association held at Gratz in September of 1875, Weyprecht read a paper on the principles of Arctic exploration, in which, according to the summary of its contents, which appeared in Nature, October 11, 1875, he maintains, that the Polar regions offer, in certain important respects, greater advantages than any other part of the globe for the observation of natural phenomena—Magnetism, the Aurora, Meteorology, Geology, Zoölogy, and Botany. He deplores, that while large sums have been spent and much hardship endured for geographical knowledge,[xiii] strictly scientific observations have been regarded as holding a secondary place. Though not denying the importance of geographical discovery, he maintains, that the main purpose of future Arctic expeditions should be the extension of our knowledge of the various natural phenomena which may be studied with so great advantage in those regions. He insists in that paper on the following propositions:—“1. Arctic exploration is of the highest importance to a knowledge of the laws of nature. 2. Geographical discovery in those regions is of superior importance only in so far as it extends the field of scientific investigation in its strict sense. 3. Minute Arctic topography is of secondary importance. 4. The geographical Pole has for science no greater significance than any other point in high latitude. 5. Observation stations should be selected without reference to the latitude, but for the advantages they offer for the investigation of the phenomena to be studied. 6. Interrupted series of observations have only a relative value.” The suggestions thrown out by Lieutenant Weyprecht have been taken up by one whose mind seems to rise instinctively to all high aims and objects. Prince Bismarck forthwith appointed a German Commission of Arctic Exploration, consisting of some of the most eminent men of science of whom Germany can boast, who reported to the Bundesrath in a memoir, the recommendations of which were unanimously adopted. From Nature, November 11, 1875, which we have already quoted, we borrow the following résumé of that report:—

“1. The exploration of the Arctic regions is of great importance for all branches of science. The Commission recommends for such exploration the establishment of fixed observing stations. From the principal station, and supported by it, exploring expeditions are to be made by sea and by land.

“The Commission is of opinion that the region to be explored by organised German Arctic explorers is the great inlet to the higher Arctic regions situated between the eastern shore of Greenland and the western shore of Spitzbergen....

“3. It appears desirable, and, so far as scientific preparations are concerned, possible, to commence these Arctic expeditions in 1877.”

“4. The Commission is convinced that an exploration of the Arctic regions, based on such principles, will furnish valuable results, even if limited to the region between Greenland and Spitzbergen; but it is also of opinion, that an exhaustive solution of the problems to be solved can only be expected when exploration is extended over the whole Arctic zone, and when other countries take their share in the undertaking.

“The Commission recommends, therefore, that the principles adopted for the German undertaking be commended to the governments of the states which take interest in Arctic inquiry, in order to establish, if possible, a complete circle of observing stations in the Arctic zones.”

Thus we are brought face to face with two different purposes, which may be termed, respectively, the romantic and the scientific purposes of Arctic discovery. To the former the attainment of the Pole has hitherto been the all in all of a geographical discovery. “The Pole impracticable,” telegraphed by Captain Nares, as the result of the expedition which has returned baffled to our shores, is a stern reproof to all who would still advocate a dash at the Pole as the worthiest purpose of Arctic discovery. Aims and endeavours not so glaring, nor appealing in the same degree to the love of the marvellous, are suggested in the sagacious proposals of Lieutenant Weyprecht, to whom science will not refuse her calmer and more measured respect, and in whom, as Captain of the Tegetthoff, all who love deeds of daring and energy will find a congenial spirit.

To Lieutenant Payer has fallen the distinguished honour of being not only the colleague in command and friend of Weyprecht, but the historian of their common sufferings and common glory in an enterprise, the fame of which the world, we believe, will not willingly let die.

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| THE FROZEN OCEAN | page 1-10 |

| 1. The ice-sheet of the Arctic region.—2. “Leads” and “ice-holes” defined.—3. Pack-ice and drift-ice.—4, 5, 6. Various designations of ice-forms.—7. Estimate of the thickness of ice.—8. Rate of its formation.—9. Old ice.—10, 11. Characteristics of young ice.—12. Results of the unrest in Arctic seas.—13. The snow-sheet described.—14. Colour of field-ice.—15. Characteristics of sea-ice.—16. Specific gravity of ice.—17. Irregularity of the forms of ice.—18. Temperature of the Arctic Sea.—19. Noise caused by disruption.—20. The ice-blink.—21. The water-sky.—22. Evaporation.—23. Calmness of the sea beneath the ice.—24. Overturning of icebergs.—25. Change of the sea’s colour near ice.—26. Icebergs described.—27. Noise caused by the overturning of icebergs. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| NAVIGATION IN THE FROZEN OCEAN | page 11-19 |

| 1. Preparatory study necessary for Polar navigators.—2. Choice of a favourable year necessary.—3. Navigation in coast-water recommended.—4. Failure often caused by leaving the coast-water.—5. Distance possible to accomplish in one summer.—6. The best time of year.—7. Steam-power recommended.—8. The rate of speed.—9. The build of Arctic ships.—10. Tactics of a ship in the ice.—11. Small vessels preferred.—12. Iron ships not suitable.—13. Two vessels to be employed.—14. “Besetment” and how to avoid it.—15. The use of a balloon recommended.—16. The “crow’s-nest.”—17. Winds and calms.—18. A winter harbour or “dock.” | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE PENETRATION OF THE REGIONS WITHIN THE POLAR CIRCLE; THE PERIOD OF THE NORTH-WEST AND NORTH-EAST PASSAGES | page 20-24 |

| 1. The Pole.—2. Old fancy of reaching India through the ice.—3, 4, 5. The first Polar navigators.—6-10. The North-West and North-East Passages.—11. Strange tales of the old discoverers.—12. The Polar world becomes the object of scientific investigation.—13. M’Clintock perfects the art of sledging.[xvi] | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE INNER POLAR SEA | page 25-31 |

| 1. The Arctic Sea compared to the glaciers of the Alps.—2, 3. Old fancies respecting an Inner Polar Sea.—4. Improbability of such a sea existing.—5. Influence of the Gulf Stream.—6. The Polynjii seen by Wrangel.—7. State of the ice in different years as found by various expeditions.—8. Probability that the most northerly regions do not differ from those already discovered.—9. Improbability that the Pole can be reached by a ship.—10. The English expedition to penetrate Smith’s Sound. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| THE FUTURE OF THE POLAR QUESTION | page 32-36 |

| 1. Material advantage from Arctic voyages.—2. The commercial value of the North-West and North-East Passages no longer thought of.—3. The Polar question a problem of science.—4. The increase of the safety and convenience with which the ice-navigation is now performed.—5. The means of conducting Polar expeditions perfected.—6. Sledge expeditions afford the chief hope of success.—7. Not much more to be expected from ships.—8. The route by Smith’s Sound recommended.—9. The English expedition.—10. Lieutenant Weyprecht’s plan for united scientific investigation. | |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| POLAR EQUIPMENTS | page 37-46 |

| 1. Past experience to be consulted.—2. The commander.—3. Selection of the crew.—4. Discipline and pay.—5. The best men to be obtained.—6. Special qualifications.—7. The medical man.—8. An artist or photographer desirable.—9. Old ideas of equipment.—10. The greatest possible comfort necessary.—11. A table of the sizes of the vessels in various expeditions.—12. The best kind of ships.—13. The allowance of food.—14. Spirituous liquors.—15. The ship becomes a house in the winter.—16. The quarters of the men.—17. Lamps and candles.—18. Clothing of the crew.—19. Instruments and ammunition.—20. The cost of different expeditions. | |

| The Pioneer Voyage of the Isbjörn | page 49-69 |

| 1. A pioneer expedition resolved on.—2, 3. Route to the east of Spitzbergen.—4. The Isbjörn chartered for the service.—5. Attempts to gain information on the probable state of the ice.—6. An unfavourable ice-year predicted.—7. The expedition leaves Tromsoe.—8. The coast of Norway described.—9. The Isbjörn in the ice.—10. Seeking a harbour.—11. Cape Look-out.—12. Two ships met with.—13. In the ice.—14. The return to the ice-barrier.—15. The geological formation of the western coast.—16. Arrive at Hope Island.—17. Ice disappeared.—18. Whales abound.—19. Splendid effects of colour.—20. In a sea.—21. A run along the west coast of Novaya Zemlya.—22. Storms compel us to keep to sea.—23. Object of the voyage.—24. The Austro-Hungarian Expedition of 1872.-25. The plan of the Austro-Hungarian Expedition.[xvii] | |

| VOYAGE OF THE “TEGETTHOFF.” | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| FROM BREMERHAVEN TO TROMSOE | page 73-77 |

| 1. The qualities requisite for a Polar navigator.—2. The crew of the Tegetthoff—3. The Tegetthoff lifts her anchor.—4. The vessel.—5. Crossing the sea.—6. The languages spoken on board the Tegetthoff.—7. The officers and crew of the Tegetthoff.—8. Arrive at Tromsoe.—9. The first and last voyage of the Tegetthoff begins. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| ON THE FROZEN OCEAN | page 78-92 |

| 1. Within the frozen ocean.—2. The sea of Novaya Zemlya.—3. We continue our course by steam.—4. The decay of ice.—5. Effects of light.—6. We meet the Isbjörn.—8-10. The Barentz Islands described by Professor Höfer.—11. Preparations for future contests with the ice.—12. Inclosed in the land-ice.—13. We celebrate the birthday of Francis Joseph I.—14. Our prospects do not improve.—15. The Tegetthoff finally beset. | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| DRIFTING IN THE NOVAYA ZEMLYA SEAS | page 93-100 |

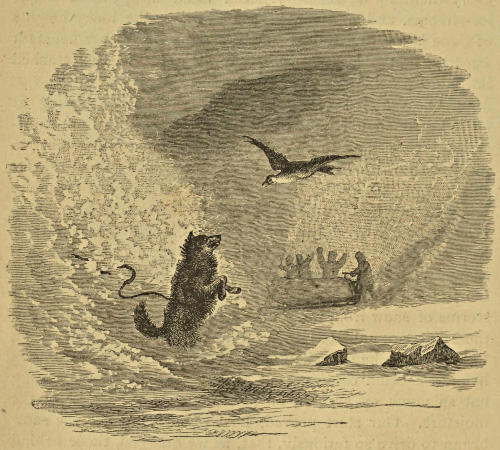

| 1. Winter begins.—2. The impossibility of reaching the coast of Siberia.—3. Unsuccessful efforts to get free.—4. The name-day of the Emperor Francis Joseph I.—5. Encounters with polar bears.—6. A “snow-finch” visits the ship.—7. Novaya Zemlya recedes gradually from our gaze. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE “TEGETTHOFF” FAST BESET IN THE ICE | page 101-113 |

| 1. Signs indicate the insecurity of our position.—2. A dreadful Sunday.—3. We make ready to abandon the ship.—4. The dogs.—5. We return to the ship.—6. We drift in the Frozen Sea.—7. Our alarms.—8. Our constant state of readiness to meet destruction. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| OUR FIRST WINTER (1872) IN THE ICE | page 114-125 |

| 1. Surrounded by deep twilight.—2. Our preparations for winter.—3. The difficulty of sledge-travelling.—4. Sumbu mistaken for a fox—5. The rending of the ice.—6. Our short expeditions.—7. The continual threatening of the ice.—8. A bear shot.—9. The effect of the long Polar night.—10. The middle of the long night.—11. Christmas feasts.—12. The first hour of the new year.—13. The dogs allowed in the cabin.—14. Carlsen writes in the log-book.[xviii] | |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

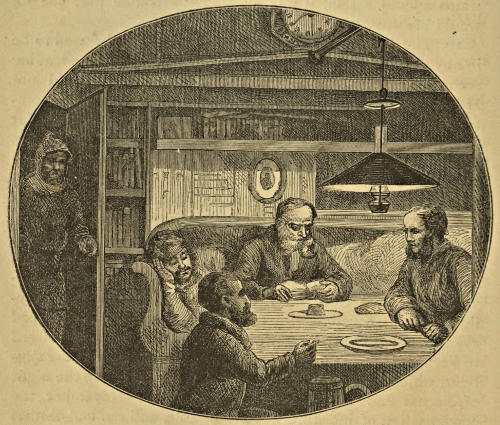

| LIFE ON BOARD THE “TEGETTHOFF” | page 126-138 |

| 1. The Tegetthoff covered with snow.—2. The excessive condensation of moisture.—3. The destruction of the snow wall.—4. The removal of the tent roof.—5. The stove of Meidingen of Carlsruhe.—6. The arrangements of the officers’ mess-room.—7. Those who occupied the mess-room.—8. Our meals.—9. Divine service on deck.—10. After dinner.—11. The monotony of our life.—12. After supper.—13. Middendorf contrasting the influence of climate on men.—14. Our sanitary condition.—15. Baths.—16. Passages from my journal.—17. A school instituted. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| ICE-PRESSURES | page 139-142 |

| 1. Preparations for leaving the ship.—2. Extracts from journal. | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE WANE OF THE LONG POLAR NIGHT | page 143-148 |

| 1. The light increases.—2. A bear hunt.—3. Table of the course of the Tegetthoff.—4. Throw out bottles inclosing an account of the events of the expedition. | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| THE RETURN OF LIGHT.—THE SPRING OF 1873 | page 149-161 |

| 1. The sunrise.—2. Our first look at each other.—3. Visits from bears.—4. The carnival.—5. Continual fall of snow.—6. Return of birds.—7. Ill health of Dr. Kepes.—8. Bear shot.—9. A road constructed.—10. Reading without artificial light.—11. Accumulation of rubbish round the ship.—12. Begin to dig out the ship.—13. Surprised by bears.—14. Our hopes to reach Siberia.—15. Snow continues to fall.—16. Visited by birds.—17. The steam machinery put in working order.—18. A partial eclipse of the sun.—19. Birth of four Newfoundland puppies. | |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| THE SUMMER OF 1873 | page 162-172 |

| 1. Decay of the walls of the ice.—2. The blaze of light on clear days.—3. Our constant digging.—4. Continual sinking of the ship.—5. Nothing but ice.—6. Short expeditions.—7. Feast on the birthday of the Emperor.—8. Table showing our change of place.—9. Some paragraphs from the Admiral’s report of the Tegetthoff—10. Sounding the depth of the sea. | |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| NEW LANDS | page 173-177 |

| 1. Seal-hunting.—2. Sunset at midnight.—3. The second summer gone.—4. Land at last.—5. Kaiser Franz-Josef’s Land.—6. Hochstetter Island.[xix] | |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| THE AUTUMN OF 1873.—THE STRANGE LAND VISITED | page 178-184 |

| 1. Autumn of 1873.—2. Resolve to abandon the vessel.—3. Daylight begins to fail.—4. Everything in readiness to leave the ship.—5. Wilczek Island.—6. Our joy at reaching land.—7. Exploring the island.—8. An expedition.—9. The silence of Arctic Regions.—10. The island continues a mystery. | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| OUR SECOND WINTER IN THE ICE | page 185-198 |

| 1. Night begins to reign.—2. Leisure for study.—3. Complete darkness.—4. Continual fall of snow.—5. The middle of the second Polar night.—6. Ill temper of the dogs.—7. The dogs.—8. Pekel, Sumbu, and Jubinal.—9. Christmas time.—10. Our life in the ship.—11. Improvement in health.—12. Scurvy. | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| SUNRISE OF 1874 | page 199-201 |

| 1. Return of the moon.—2. Sun appears above the horizon.—3. Lieutenant Weyprecht and I resolve to abandon the ship after the sledge journeys. | |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| THE AURORA | page 202-210 |

| 1. The northern lights.—2-4. The appearance of the aurora.—5. The influence on the magnetic needle.—6. Description of the aurora by Lieutenant Weyprecht. | |

| THE SLEDGE JOURNEYS. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| THE EXPLORATION OF KAISER FRANZ-JOSEF LAND RESOLVED ON | page 213-215 |

| 1. Necessity of exploration.—2. Plan of the sledge journeys.—3. Eagerness to begin.—4. Illness of Krisch. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| OF SLEDGE TRAVELLING IN GENERAL | page 216-221 |

| 1. The sledge the best means of exploration.—2. The coast line to be followed.—3. Best season for sledging.—4. State of the snow-road.—5. The formation of depôts.—6. Sledges dragged by men and dogs—7. Sledging best performed by dogs.—8. The instruments required on a sledge journey.[xx] | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

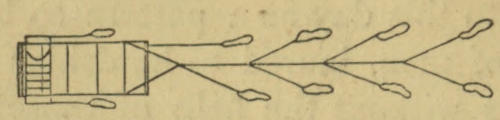

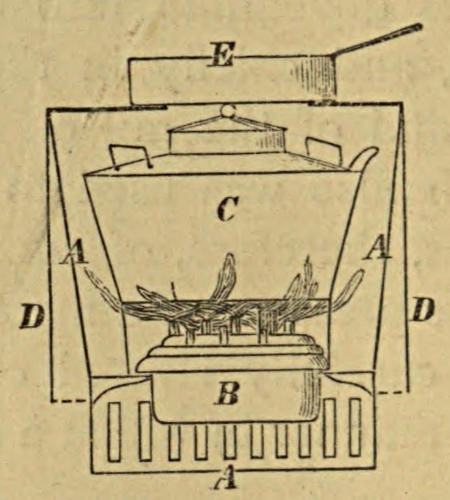

| THE EQUIPMENT OF A SLEDGE EXPEDITION | page 222-234 |

| 1. The equipment of a sledge.—2. Construction of our sledges.—3. The cooking apparatus.—4. Fuel.—5. Tents used at night.—6. The sleeping bag.—7. Arms and ammunition.—8. Chest for instruments, &c.—9, 10, 11. The provisions.—12. Boats in sledge expeditions.—13. Articles of clothing.—14. Furs.—15. Covering for the feet.—16. Drawing the sledge. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE FIRST SLEDGE JOURNEY | page 235-245 |

| 1. Qualities of a leader.—2. Object of our first expedition.—3. My party.—4. We begin our journey.—5. Violent motion of the ice.—6. Conduct of the dogs.—7. Death of the bear.—8. The driving snow.—9. Reach the plateau of Cape Tegetthoff.—10. Ascending the plateau.—11. Night in the sleeping bag.—12. Difficulty of dragging the sledge.—13. Ascend a mountain, Cape Littrow. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| THE COLD | page 246-257 |

| 1. The Sonklar glacier.—2. Effect of cold.—3. The frightful cold of North America.—4. Effect of low temperature on the human frame.—5. The voice in cold weather.—6. Hardness of everything.—7. Effect of cold on the senses.—8. Protection against cold.—9. Danger of frost-bite.—10. Thirst.—11. A block of snow.—12. Return to the ship.—13. Death of Krisch. | |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| A GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF KAISER FRANZ-JOSEF LAND | page 258-270 |

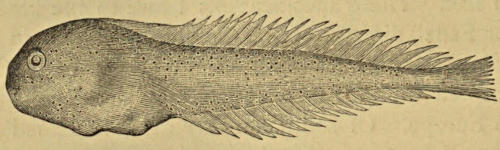

| 1. Size of the country.—2. Surface of ice.—3. Map of the country.—4. Naming of discoveries.—5. Comparison of Arctic lands.—6. The existence of volcanic formations.—7, 8. Geology of Franz-Josef Land.—9. Glaciers of Spitzbergen.—10. Ice of Franz-Josef Land.—11. Temperature of the air.—12. The plasticity of the glaciers.—13. North-east of Greenland and Siberia.—14. The vegetation.—15. Finding drift-wood.—16. Impossibility of inhabiting Franz-Josef Land.—17. The absence of animal life.—18. Seals abound.—19. Species of fish seen.—20. Birds.—21. The collection of Dr. Kepes. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| THE SECOND SLEDGE EXPEDITION.—AUSTRIA SOUND | page 271-294 |

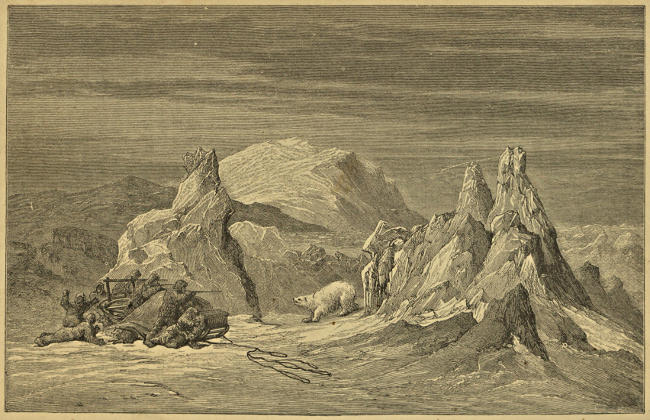

| 1. Plan of second expedition.—2. Danger of leaving the ship.—3. Visited by bears.—4. Our preparations finished.—5. The sledge party.—6. Our march.—7. Torossy wounded by a bear.—8. Danger of frost-bite.—9. Arrive at Cape Frankfurt.—10. The configuration of the country.—11. We penetrate to Cape Hansa.—12. A bear killed.—13. I examine the beach.—14. Loss of the dog Sumbu.—15. Easter Sunday.—16. Approach of a bear.—17. Our canvas boots worn out.—18. We reach Becker Island.—19. We lose a bear.—20. Direct our course towards Cape Rath.—21. A bear shot.—22. Difficulty of advancing.—23. We arrive at Cape Schrötter.[xxi] | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| IN THE EXTREME NORTH | page 295-313 |

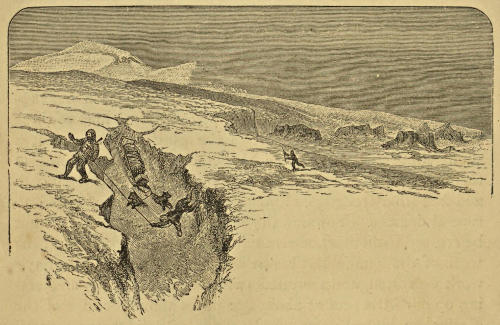

| 1. We ascend the summit of the Dolerite Rock.—2. Our expedition to the extreme north.—3. We divide the provisions.—4. The merits of our dogs.—5. Klotz has to return.—6. Zaninovich and the sledge fall into a crevasse.—7. Reach Cape Habermann.—8. Cape Brorock.—9. The enormous flocks of birds.—10. Difficulty of travelling.—11. Cape Säulen.—12. Reach Cape Germania.—13. Cape Fligely.—14. We plant the Austro-Hungarian flag.—15. Document inclosed in a bottle. | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| THE RETURN TO THE SHIP | page 314-335 |

| 1. Our return journey.—2. Observations of temperature.—3. Snow-blindness.—4. A bear shot.—5. Reach Cape Hellwald.—6. Orel continues to march southwards.—7. Reach Cape Tyrol.—8. Grandeur of the scenery.—9. Find our companions.—10. We sink in the snow.—11. Arrive at open sea.—12. Over the glaciers of Wilczek Land.—13. Enveloped in whirling snow.—14. Digging out our depôt.—15. The difficulty of advancing.—16. Reach Schönau Island.—17. I find the ship.—18. The ship in our absence. | |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| THE THIRD SLEDGE JOURNEY | page 336-340 |

| 1. Our wish to explore Franz-Josef Land.—2. We leave the ship.—3. The dogs and the bears.—4. A bear killed.—5. Ascent of the pyramid-like Cape Brünn.—6. The extreme difficulty of the ascent.—7. Return to the ship. | |

| THE “TEGETTHOFF” ABANDONED.—RETURN TO EUROPE. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| LAST DAYS ON THE “TEGETTHOFF” | page 343-347 |

| 1. “Plundering the ship.”—2. Appearance of the ship.—3. Short expeditions.—4. Rapid decrease of the cold.—5. The boats and their contents.—6. The dogs, Gillis and Semlja, shot.—7. Our stock of clothes.—8. Our plan of escape. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| ON THE FROZEN SEA | page 348-376 |

| 1. The day for abandoning the ship comes.—2. We start.—3. The dogs.—4. We return to the ship to replenish the stores.—5. Shooting bears.—6. Reach Lamont Island.—7. Return to the ship for the jolly boat.—8. Impatience to launch our boats.—9. Launch at last.—10. Shoot a seal.—11. Quotations from the journal.—12. Crossing fissures.—13. Disheartening efforts.—14. From one floe to another.—15. Carlsen.—16. Life in the boats.—17. Our[xxii] dreadful situation.—18. Our rations diminished.—19. Forcing our way.—20. Pushing floes asunder.—21. No advance, but great efforts.—22. Delight caused by an advance of four miles a day.—23. Secure a bear.—24. Our progress greatly increases.—25. Ice-hummocks everywhere.—26. Alternate launching and drawing up the boats.—27. Increased progress.—28. The swell of the ocean.—29. Shut in once more.—30. Contrivances to pass away the time.—31. Calking the boats.—32. We reach the open sea.—33. Farewell to the Frozen Ocean. | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| ON THE OPEN SEA | page 377-389 |

| 1. Sight of the open sea.—2. Compelled to kill the dogs.—3. We take a last look at the ice.—4. Fifty miles from land.—5. We sight Novaya Zemlya.—6. We hold on our course.—7. Vain attempt to land on Novaya Zemlya.—8. Difference in the climate in various years.—9. Land in Gwosdarew Bay.—10. Step on land once more.—11. Coast of Novaya Zemlya.—12. Look in vain for a sail.—13. Our provisions nearly exhausted.—14. We divide the remnant of food.—15. Deliverance at last.—16. The schooner Nikolai.—17. Our reception on board.—18. We hear the news from Europe.—19. Captain Voronin agrees to take us to Norway.—20. The crew of the Nikolai.—21. We run along the coast of Lapland.—22. Landing at Vardö.—23. Reception. | |

| APPENDIX. | |

| I. METEOROLOGICAL OBSERVATIONS | page 391-393 |

| II. DIRECTION AND FORCE OF THE WIND | page 394 |

| INDEX | page 395 |

| PAGE | |

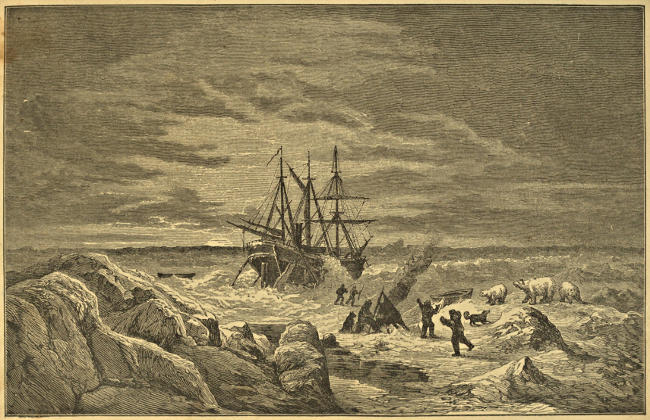

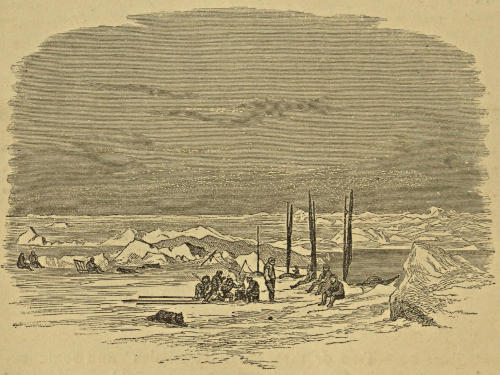

| TWILIGHT AT MIDDAY—FEBRUARY, 1874 | Frontispiece |

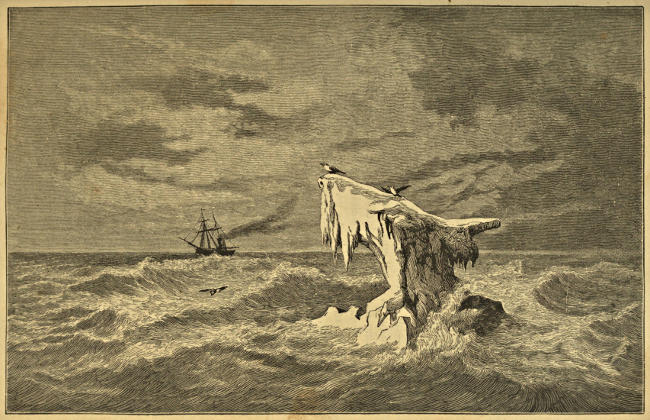

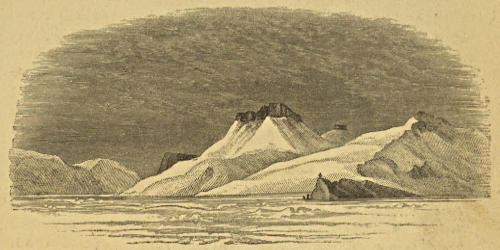

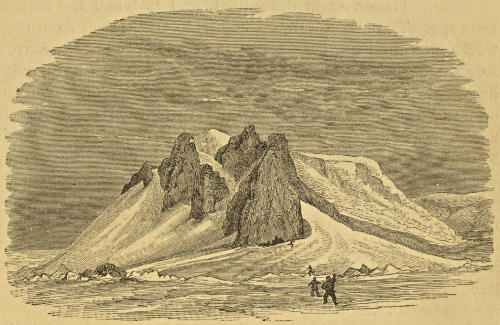

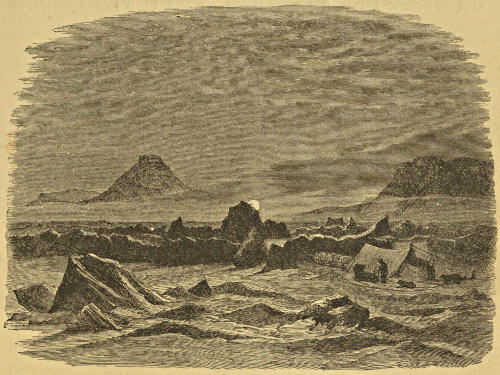

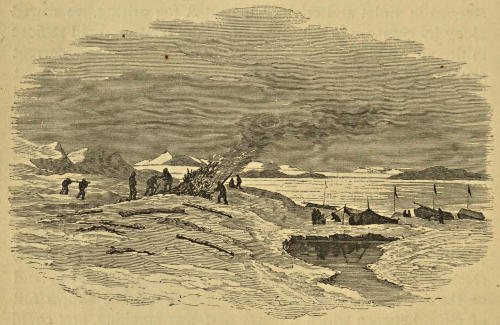

| THE FIRST ICE | 53 |

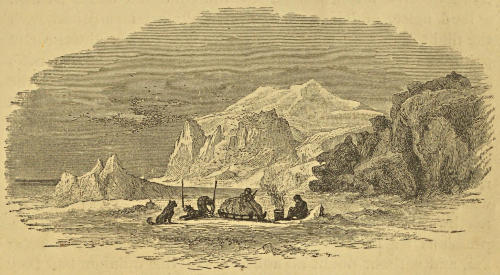

| STILL LIFE IN THE FROZEN OCEAN | 79 |

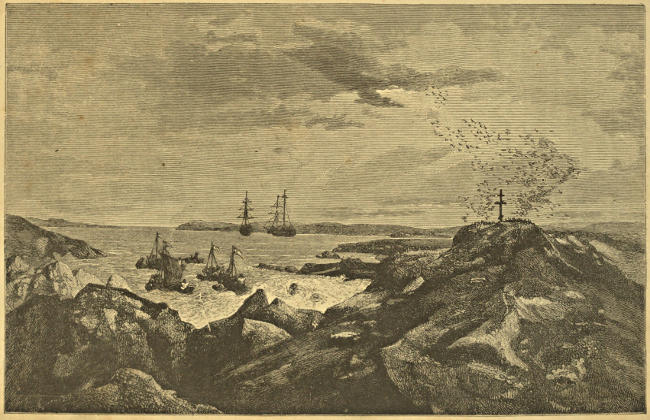

| GWOSDAREW INLET | 84 |

| FORMATION OF THE DEPÔT AT “THE THREE COFFINS” | 89 |

| THE “TEGETTHOFF” AND “ISBJÖRN” SEPARATE | 90 |

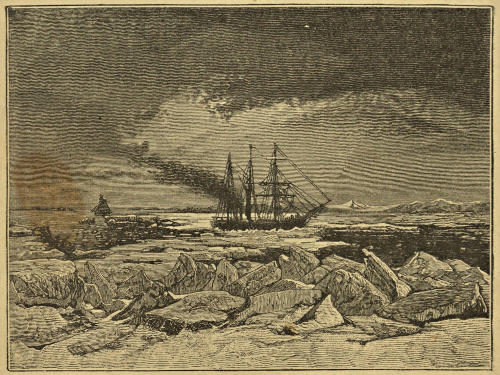

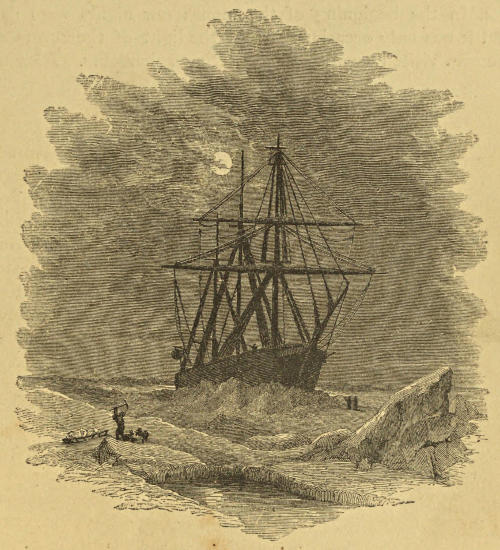

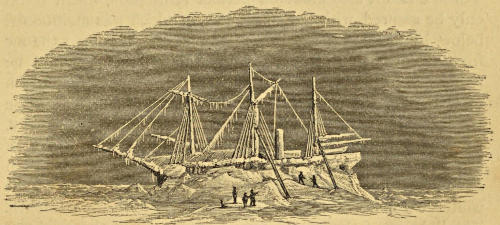

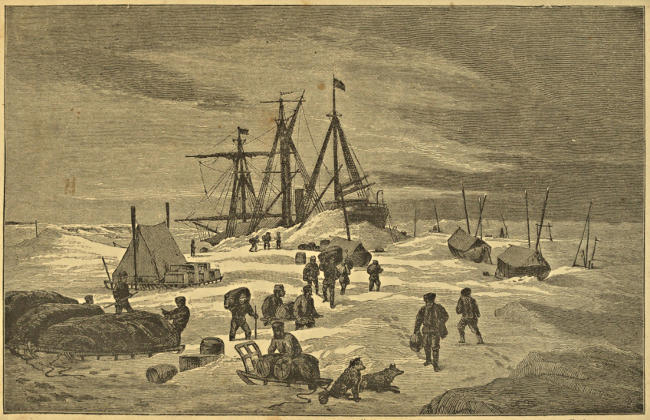

| THE “TEGETTHOFF” FINALLY BESET | 91 |

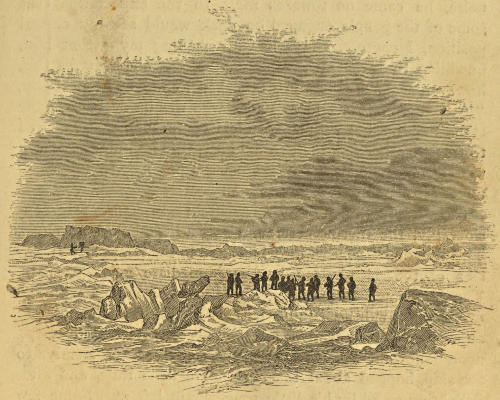

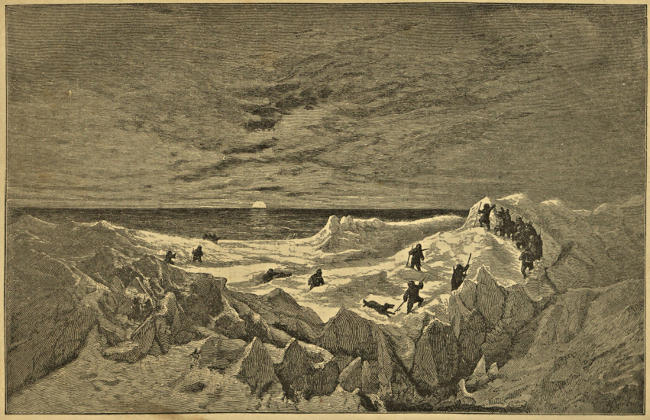

| ATTEMPTS TO GET FREE IN SEPTEMBER | 94 |

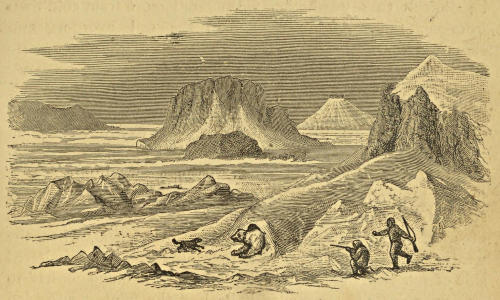

| SEAL-HUNTING—SEPTEMBER 1872 | 96 |

| SHOOTING AT A TARGET, OCTOBER 1872 | 97 |

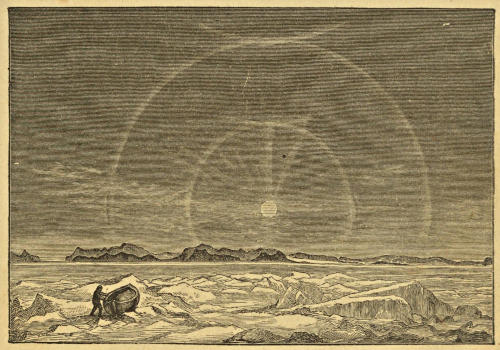

| PARHELIA ON THE COAST OF NOVAYA ZEMLYA | 99 |

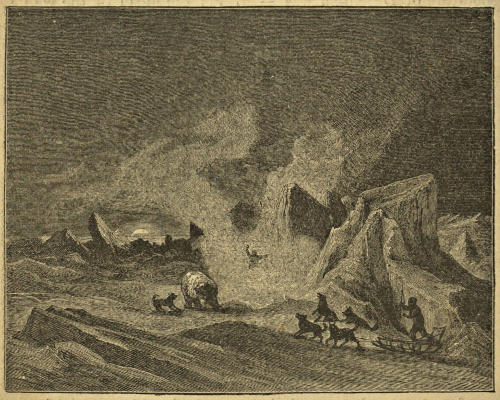

| AN OCTOBER NIGHT IN THE ICE | 105 |

| THE MOON WITH ITS HALO | 109 |

| OUR COAL-HOUSE ON THE FLOE | 111 |

| THE TWILIGHT IN NOVEMBER 1872 | 115 |

| SUMBU CHASED FOR A FOX | 116 |

| WANDERINGS ON THE ICE IN OUR FIRST WINTER | 117 |

| ENCOUNTER WITH A POLAR BEAR | 120 |

| ICE-HOLE COVERED WITH YOUNG ICE | 121 |

| CARLSEN MAKES THE ENTRY IN THE LOG | 124 |

| THE “TEGETTHOFF” IN THE FULL MOON | 127 |

| DIVINE SERVICE ON DECK | 131 |

| ICE-PRESSURE IN THE POLAR NIGHT | 140 |

| FRUITLESS ATTEMPT TO RESCUE MATOSCHKIN | 145 |

| SUNRISE (1873) | 150 |

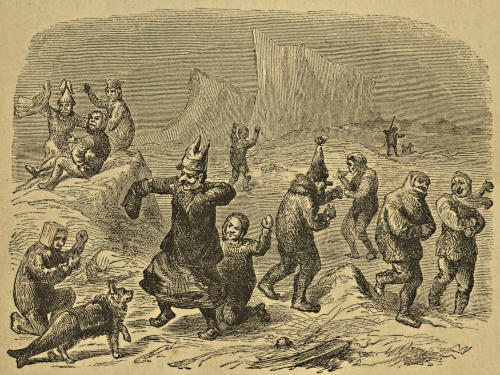

| THE CARNIVAL ON THE ICE | 152 |

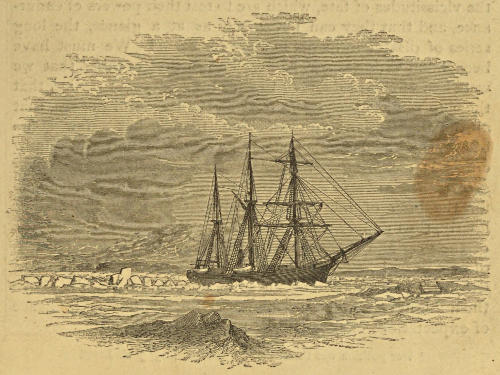

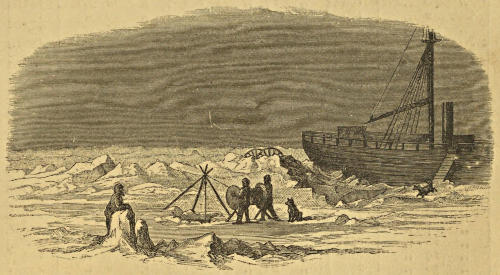

| THE “TEGETTHOFF” DRIFTING IN PACK-ICE—MARCH 1873 | 155 |

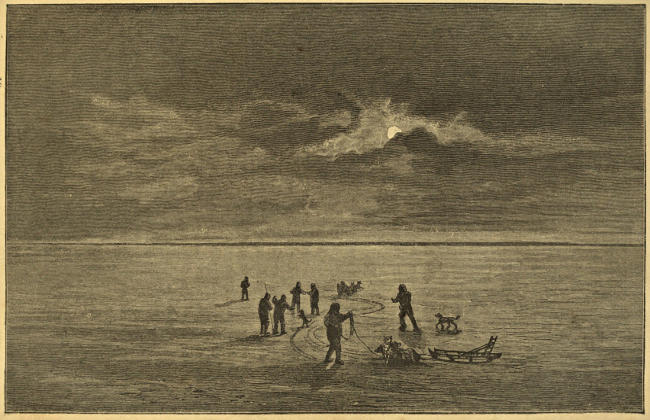

| SOUNDING IN THE FROZEN OCEAN | 171 |

| APPROACHING THE LAND BY MOONLIGHT | 183 |

| DEPARTURE OF THE SUN IN THE SECOND WINTER | 187 |

| NOON ON DECEMBER 21, 1873 | 189 |

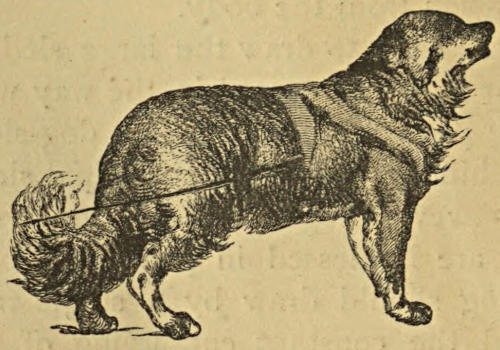

| PEKEL, SUMBU, AND JUBINAL | 193 |

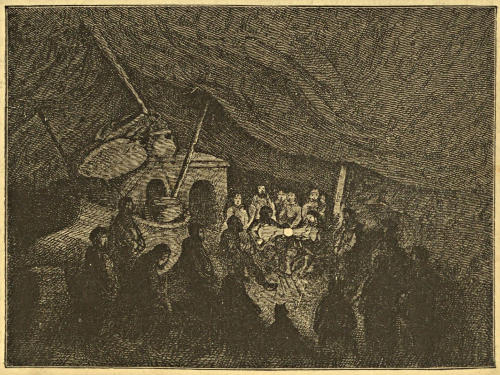

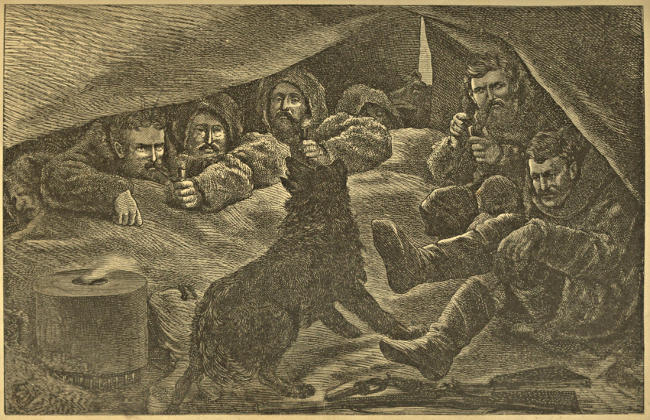

| IN THE MESS-ROOM | 196 |

| THE AURORA DURING THE ICE-PRESSURE | 204 |

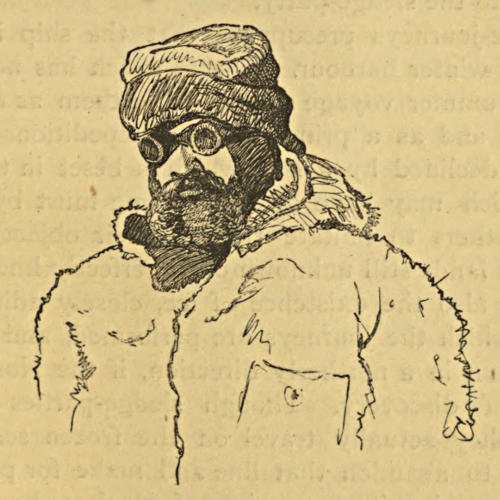

| KRISCH, THE ENGINEER | 215 |

| TEAM OF SEVEN MEN AND THREE DOGS | 224 |

| THE COOKING APPARATUS | 224 |

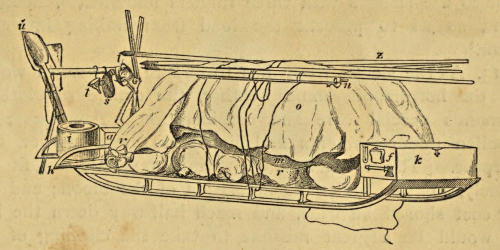

| THE SLEDGE WITH ITS LOAD | 229 |

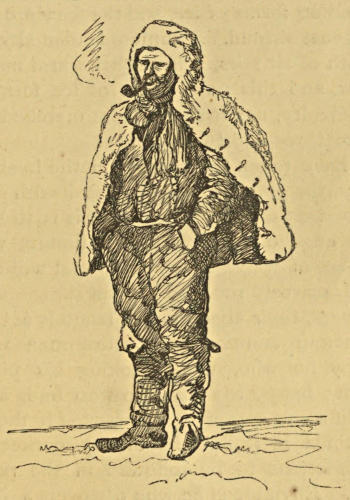

| THE DRESS OF THE ARCTIC SLEDGER | 231 |

| TOROSSY IN HARNESS | 234 |

| CAPE TEGETTHOFF | 242 |

| MELTING SNOW DURING A HALT NEAR CAPE BERGHAUS | 244 |

| [xxiv]ON THE SONKLAR-GLACIER | 247 |

| BLOCK OF SNOW | 254 |

| THE BURIAL OF KRISCH | 256 |

| LIPARIS GELATINOSUS | 266 |

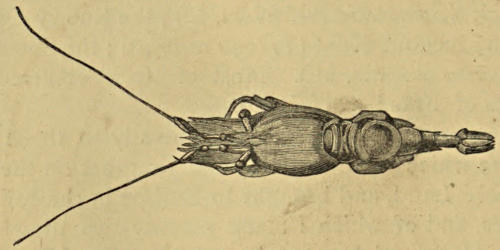

| HIPPOLYTE PAYERI | 268 |

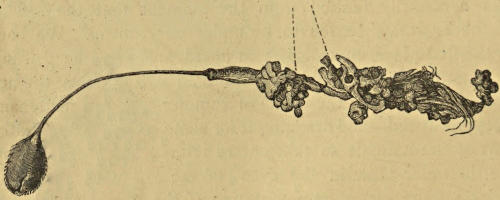

| HYALONEMA LONGISSIMUM | 268 |

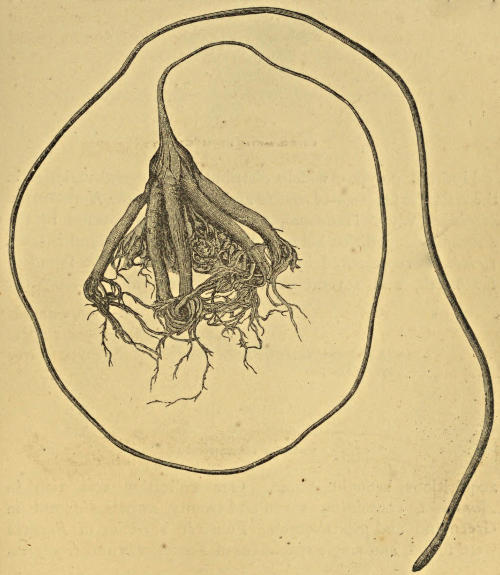

| UMBELLULA | 269 |

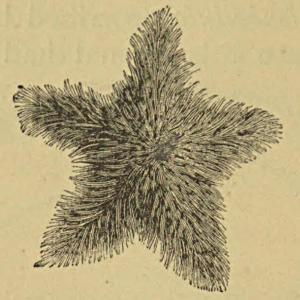

| KORETHRASTES HISPIDUS | 270 |

| NEPHTHYS LONGISETOSA | 270 |

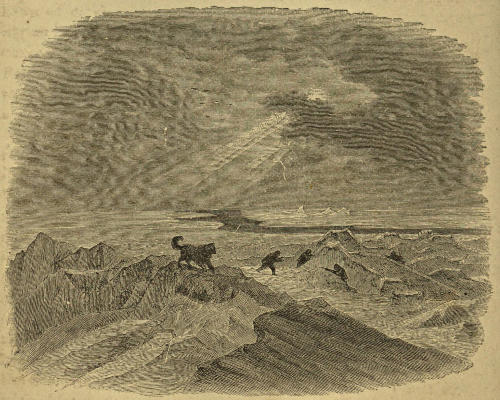

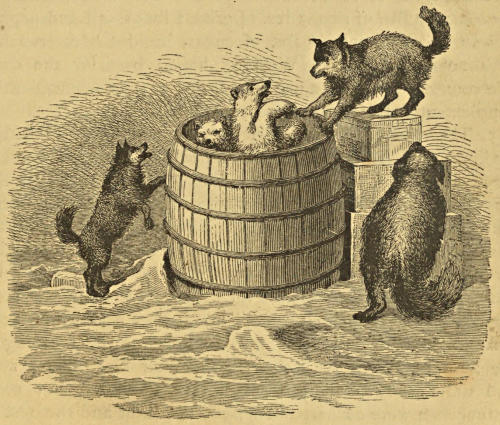

| THE DOGS DIFFER AS TO THE TREATMENT OF YOUNG BEARS | 273 |

| THE WINTER HOLE OF A BEAR | 277 |

| LIFE IN THE TENT | 279 |

| CAPE FRANKFURT, AUSTRIA SOUND, AND THE WÜLLERSDORF MOUNTAINS | 280 |

| HOW SUMBU WAS LOST | 284 |

| CAPE EASTER AND STERNEK SOUND | 285 |

| HOW WE RECEIVED BEARS. CAPE TYROL IN THE BACKGROUND | 286 |

| DINING ON BEARS’ FLESH | 287 |

| CUTTING UP THE BEARS | 292 |

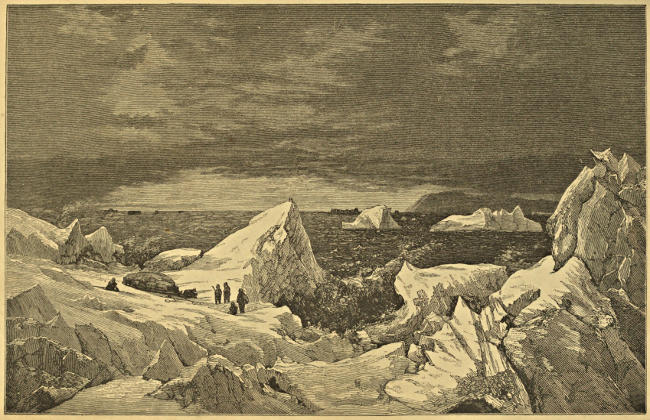

| ICEBERGS AT THE BASE OF THE MIDDENDORF GLACIER | 298 |

| THE SLEDGE FALLS INTO A CREVASSE ON THE MIDDENDORF GLACIER | 300 |

| KLOTZ’S AMAZEMENT | 302 |

| THE ALARM OF THE HOHENLOHE PARTY | 303 |

| HALT UNDER CROWN-PRINCE RUDOLF’S LAND | 305 |

| CAPE AUK | 307 |

| CAPE SÄULEN | 309 |

| THE AUSTRIAN FLAG PLANTED AT CAPE FLIGELY | 311 |

| MELTING SNOW ON CAPE GERMANIA | 315 |

| ENCAMPING ON ONE OF THE COBURG ISLANDS | 318 |

| THE VIEW FROM CAPE TYROL. COLLINSON FIORD—WIENER NEUSTADT ISLAND | 321 |

| BREAKING IN | 323 |

| ARRIVAL BEFORE THE OPEN SEA | 325 |

| DRAGGING THE SLEDGE UNDER THE GLACIERS OF WILCZEK LAND | 326 |

| THE SLEDGE IN A SNOW-STORM | 328 |

| DIGGING OUT THE DEPÔT | 329 |

| THE MIDNIGHT SUN BETWEEN CAPE BERGHAUS AND KOLDEWEY ISLAND | 331 |

| THE “TEGETTHOFF” DESCRIED | 332 |

| KLOTZ | 333 |

| MARKHAM SOUND, RICHTHOFEN PEAK FROM CAPE BRÜNN | 338 |

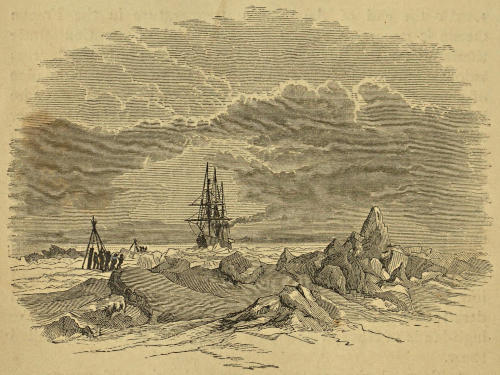

| FIRST ABANDONMENT OF THE “TEGETTHOFF” | 348 |

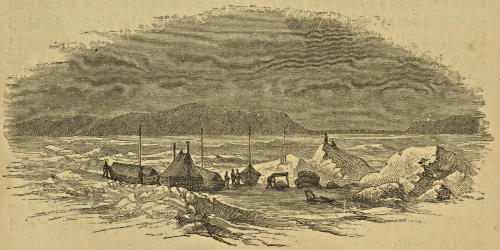

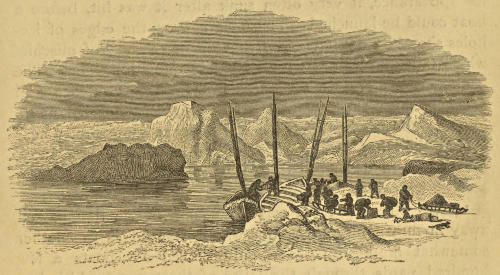

| IN THE HARBOUR OF AULIS | 352 |

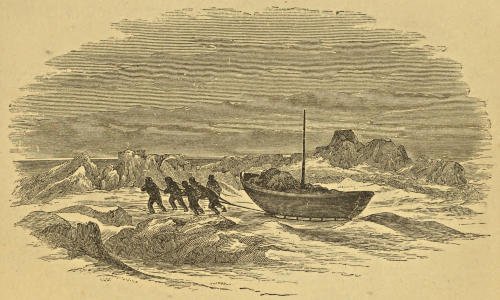

| WE LAUNCH AT LAST | 355 |

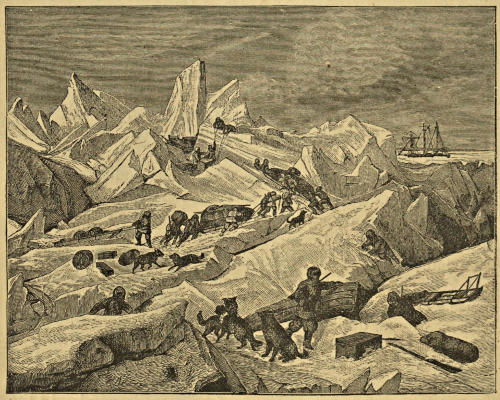

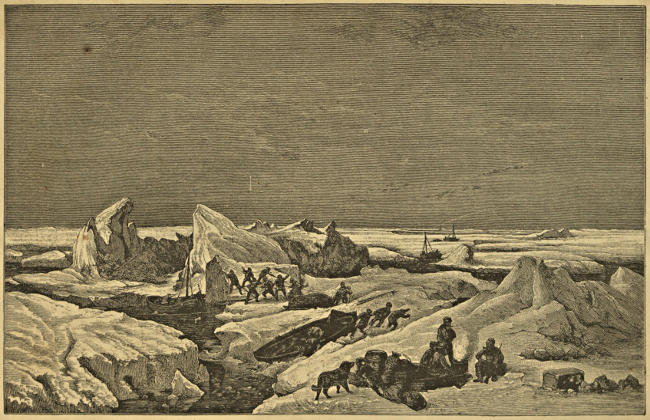

| MARCHING THROUGH ICE-HUMMOCKS | 357 |

| HALT AT NOON | 358 |

| CROSSING A FISSURE | 359 |

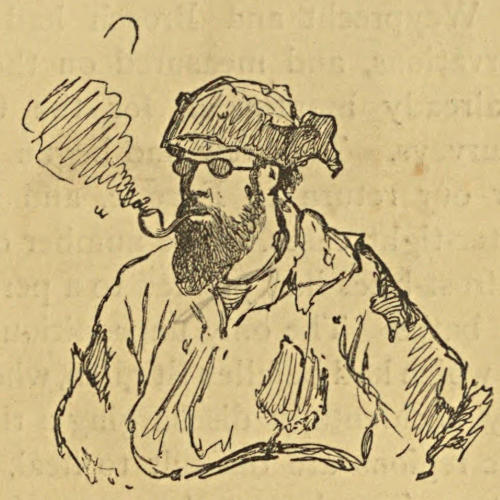

| CARLSEN | 361 |

| SCENE ON THE ICE | 366 |

| BEARS IN THE WATER | 371 |

| CALKING THE BOATS | 374 |

| FAREWELL TO THE FROZEN OCEAN | 375 |

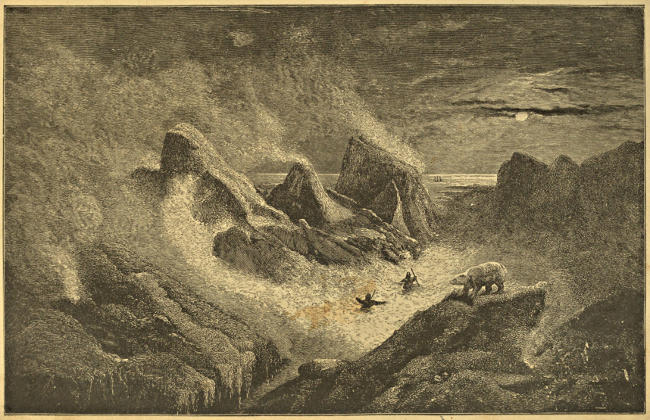

| LANDING ON THE COAST OF NOVAYA ZEMLYA | 380 |

| THE BAY OF DUNES. THE RUSSIAN SCHOONERS | 385 |

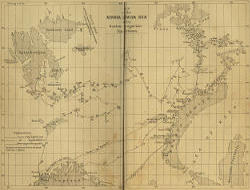

Transcriber’s Note: The map is clickable for a larger version, if the device you’re reading this on supports that.

MAP

of the

NOVAYA ZEMLYA SEA

for the

Austro-Hungarian

Expeditions.

1. The ice-sheet spread over the Arctic region is the effect and sign of the low temperature which prevails within it. During nine or ten months of the year this congealing force continues to act, and if the frozen mass were not broken up by the effects of sun and wind, of rain, waves, and currents, and by the rents produced in it from the sudden increase of cold, the result would necessarily be an absolutely impenetrable covering of ice. The parts of this enormous envelope of ice sundered by these various causes now become capable of movement, and are widely dispersed in the form of ice-fields and floes.

2. The water-ways which separate these parts are called “leads,” or, when their extent is considerable, “ice-holes.” The meshes of this vast net, which is constantly in motion, open and close under the action of winds and currents in summer; and it is only in its southern parts that the action of waves, rain, and thaw produces any considerable detachments. Towards the end of autumn, the ice, forming anew, consolidates the interior portions, while its outer edge pushes forward, like the end of a glacier, into lower regions, until[2] about the end of February the culminating point of congelation is attained. Motionless adhesion of the fields, which naturally reach their greatest size in winter, does not, however, exist even then; for during this period they are incessantly exposed to displacement and pressure from the currents of the sea and the air.

3. When the ice is more or less closed, so as to render navigation impossible, it is called “pack-ice,” and “drift-ice” when it appears in detached pieces amid predominating water. Since there are forces operating which promote the loosening process at its outer edge, and its consolidation within, it is self-evident, that the interior portions tend to the character of “pack-ice,” and its outer margin to that of “drift-ice.” This general rule, however, is so modified in many places, by local causes, currents, and winds, that we find not unfrequently at the outer margin of the ice thick barriers of pack-ice, and in the inner ice, ice-holes (polynia[1]) and drift-ice.

4. Ice navigation, during its course of three hundred years, has created a number of terms to designate the external forms of ice, the meaning of which must be clearly defined. Ice formed from salt-water is called “field-ice;” that from the waters of rivers and lakes “sweet-water ice.” The latter is as hard as iron, and so transparent that it is scarcely to be distinguished from water. Icebergs are masses detached from glaciers. The words “patch,” “floe,” “field,” express relative magnitude, descriptive of the smallest ice-table up to the ice-field of many miles in diameter. The term “floe,” however, is generally applied to every kind of field-ice, without reference to its size. The ice which lies along coasts, or which adheres to a group of islands within a sound, is called “land-ice.” Sledge expeditions depend on its existence and character. Along the coast-edge land-ice is broken by the waves and tide, and the forms of its upheaval and deposition on the shore constitute the so-called “ice-foot.” Broken ice, or “brash,” is an accumulation of the smaller fragments of ice which are found only on the extreme edge of the ice-belt. “Bay-ice” is ice of recent formation, and its vertical depth is inconsiderable.

5. Land-ice is less exposed to powerful disturbances, and its surface, therefore, is comparatively level, and is only here and there traversed by small hillocks called “hummocks” or “torrosy.” These are the results of former pressures, and they are gradually reduced to the common level by evaporation, by thawing, and by the snow drifting over them.

6. But ice-floes exposed to constant motion from winds and currents, and to reciprocal pressure, have a more or less undulating character. On these are found piles of ice heaped one upon another, rising to a height of twenty or even fifty feet, alternating with depressions, which collect the thawed water in clear ice-lakes during the few weeks of summer in which the temperature rises above the freezing point. The specific gravity of this water, where it does not communicate with the sea by cracks, is in all cases the same with the specific gravity of pure sweet water; and as the salt is gradually eliminated from the ice, the water produced is perfectly drinkable. In the East Greenland Sea ice-floes frequently measure more than twelve nautical miles across—these are ice-fields properly so called.[2] In the Spitzbergen and Novaya Zemlya Seas, they are much smaller, as Parry also found.

7. The thickness which ice acquires in the course of a winter, when its formation is not disturbed, is about eight feet. In the Gulf of Boothia, Sir John Ross found the greatest thickness about the end of May; it was then ten feet on the sea and eleven feet on the lakes. In his winter harbour in Melville Island, Parry met with ice seven or seven-and-a-half feet thick; and Wrangel gives the thickness of a floe on the Siberian coast, which had been formed in the course of a winter, at nine-and-a-half feet. According to the observations of Hayes the ice measured nine feet two inches in thickness in Port Foulke. He estimates it, however, by implication, far higher in Smith’s Sound: “I have never seen,” he says, “an ice-table formed by direct freezing which exceeded the depth of eighteen feet.”

8. The rate at which ice is formed decreases as the thickness of the floe increases, and it ceases to be formed as soon as the floe becomes a non-conductor of the temperature of[4] the air by the increase of its mass, or when the driving of the ice-tables one over the other, or the enormous and constantly accumulating covering of snow, places limits to the penetration of the cold.

9. While therefore the thickness which ice in free formation attains is comparatively small, fields of ice from thirty to forty feet high are met with in the Arctic Seas; but these are the result of the forcing of ice-tables one over the other by pressure, and are designated by the name of “old ice,” which differs from young ice by its greater density, and has a still greater affinity with the ice of the glacier when it exhibits coloured veins.

10. When the cold is excessive a sheet of ice several inches thick is formed on open water in a few hours; this, however, is not pure ice, but contains a considerable amount of sea-salt not yet eliminated; complete elimination of the saline matter takes place only after continuous additions of ice to its under surface. A newly-formed sheet of ice is flexible like leather, and as it becomes harder by the continued cold, its saline contents come to the surface in a white frosty efflorescence.

11. Hayes mentions that he met with fields of ice from twenty to a hundred feet thick in Smith’s Sound. But if it is difficult in many cases to distinguish glacier-ice, when found in small fragments, from detached portions of field-ice, it is often still more difficult to distinguish between old and new ice, and the attempt to do so is merely arbitrary, because their masses depend not on their age alone, but on other processes to which they are exposed. A floe of normal thickness is never more than two or three years old; and if it is to exist and preserve its size for a longer period, it must somewhere attach itself to land-ice, so as to escape destruction from mechanical causes, and dissolution from drifting southwards. Many floes run their course from freezing to melting within a year.

12. The perpetual unrest in the Arctic Sea, which continues undiminished even in the severest winter, and the incessant change in the “leads” and “ice-holes,” are the main causes of the increase of the ice, both in its area and in its vertical depth. Were this constant movement to cease, the result would be the formation of a sheet of ice of the[5] uniform thickness of about eight feet over the whole Polar region.

13. A layer of snow, which, like the ice itself, is at a minimum in autumn, covers the whole surface of all the ice-fields. This snow, which in winter is sometimes as hard as a rock, sometimes as fine as dust, takes, towards the end of summer, more and more the character of the glacier snow of our lofty Alpine ranges. Its grains, in a humid state, exceed the size of beans, and when in motion they make a rustling noise like sand. This granular snow is the residuum of the incomplete evaporation of what fell in the winter, and of the surface of the ice which has become “rotten” and porous. Its crystals are frequently from a third to a sixth of an inch in length, and firm ice is found even in autumn only at the depth of one or two feet. In the North of Spitzbergen, Parry observed that the surface of the ice was frequently cut up into ice-needles of more than a foot long by the drops of rain, which in summer fall upon it, and in some places he found it overspread with red snow. We ourselves never saw the phenomenon observed by Parry, and the ice-crystals we met with seldom exceeded the length given above.

14. Field-ice is of a delicate azure-blue colour, and of great density, and there is, in these respects, no difference between that of the Arctic and Antarctic regions. Cook, indeed, calls the South Polar ice colourless, though Sir James Clark Ross speaks expressly of the blueness of its ice-masses. Sea-ice surpasses the ice of the Alps both in the beauty of its colour and in its density. The glorious blue of the fissures is due to the incidence of light, the blue rays of which only are reflected, while the other rays are absorbed. A spectrum observation made in 1869 on a Greenland ice-field gave brownish red, yellow, green and blue. The yellowish spots observed in ice are due to the presence of innumerable microscopic animalculæ.

15. Sea-ice, which, when the cold is intense, is hard and brittle, loses this quality with the increase of temperature till it acquires an incredible toughness, far exceeding that of glaciers; and floes several feet thick bend under mutual pressure before they split. Hence the fruitlessness, especially[6] in summer, of all attempts to loosen the connexion of its parts by blasting with gunpowder.

16. The specific gravity of sea-ice is 0.91, and accordingly about nine parts of a cubical block of ice are under water, while one part only rises above the surface. If, however, the ice of a floe be irregularly formed and full of bubbles, the specific gravity will be correspondingly reduced, and the volume submerged may diminish to two-thirds of the whole mass.

17. The irregularity of the forms of ice is so great, that no deduction can safely be drawn from them; cases may occur where a recently-formed ice-floe, which has been attached to old ice, is forced by its neighbour to sink under the normal level; hence the submergence of floes beneath the level of the sea is often overstated.

18. The temperature of the Arctic Sea at the surface is generally below the freezing point, and then increases slightly with the depth. Sir James Ross observed that the temperature in all oceans does not alter at great depths, and placed this constant temperature at 39° F. In summer the temperature of the atmosphere rises little above freezing point, and, according to Sir James Ross, it is still less at the South Pole, because he saw no thaw-water streaming down from the icebergs there as he did in the North. It was first observed in Forster’s days, that is about a century ago, that the salt was gradually eliminated from frozen sea-water. Of this fact Cook knew nothing; and even Sir James Ross endorses Davis’s remark that “the deep sea freezes not.” But the fact that ice is formed on the open sea, and far from the vicinity of land, was first asserted by Scoresby, and has been confirmed by all subsequent observers, though it was long disputed.

19. The crackling sound so commonly heard along the outer edge of the ice exposed to the action of the waves, is a consequence of the penetration of its pores by the sea-water, which is then immediately frozen, and disruption follows at once. But disruption on a far grander scale is due to a cause the very opposite of this, the sudden contraction and splitting of the ice, even in the great ice-fields, which is produced usually in winter by the sudden fall of the temperature.

20. When light falls on a field of pack-ice, it is reflected in the stratum of air above it, and this span of light, called the “ice-blink,” just above the horizon, warns the navigator of the impossibility of penetrating further. This phenomenon is often observed also over drift-ice, although not so intense nor so yellow in colour as over pack-ice.

21. Water spaces, on the other hand, show their presence by dark spots on the horizon, produced by the formation of clouds from ascending mists. These are the so-called “water-sky,” and faithfully indicate the “leads” beneath them. Above the larger “ice-holes,” they assume the dark colours of a thunder-sky, though they are never so strongly defined.

22. The annual evaporation from the surface of the ice, which even in winter is never entirely interrupted during the severest frost, and the destruction of ice by the action of rain and waves, are balanced, to speak generally, by its re-formation by frost. The maximum accumulation of ice takes place in spring, its minimum in the beginning of autumn. We observed in the autumn of 1873 not only the evaporation of the snow of the preceding winter, but also a vertical decrease of ice of about four feet. Evaporation is, therefore, the most potent regulator of the balance between waste and growth in the accumulation of ice; and next in importance is the drifting of its masses towards the south through all those openings by which the Polar waters mingle with the waters of lower latitudes.

23. However great the agitation of the sea may be in the open ocean, and though it may dash its waves with wild fury on the edge of the ice, within the icy girdle it is undisturbed, in consequence of the enormous weight of the superincumbent masses. It is only in the large “ice-holes,” and when the winds are very high, that the action of waves is discernible. An isolated accumulation of floes in a circular form, suffices to produce a calm interior sea, and its outer edge only encounters the beat of the ocean.

24. The ceaseless attack to which the ice is exposed on its outer edge is the cause of its excavation and undermining. Hence its centre of gravity is constantly displaced; and the overturning of its masses and its strange transformations[8] are the consequences of this instability. The smaller the masses of the ice, the more fantastic are the shapes they assume.

25. Change of colour in the sea as we enter the ice-region is frequently, though not invariably, observed. Almost immediately on entering the ice, its normal dull green colour gives place to a deep ultramarine blue, especially in the East Greenland seas, and this colour is maintained under all changes of the weather, and is only modified by local currents. Two hundred and fifty years ago it appeared to Hudson, on the coast of Spitzbergen, that the sea, whenever it was free from ice, was green, and that its being covered with ice and its blueness of colour were intimately connected. Sir James Ross states that in both Polar oceans the colour of the sea changes in the neighbourhood of ice, and that the dull brownish colour sometimes seen near pack-ice in the Antarctic Ocean is owing to an infinite number of animalculæ. The rapid fall of the temperature of the water to the zero point is another indication that ice is near.

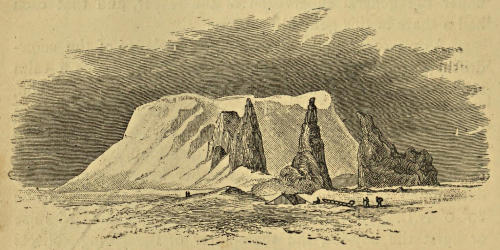

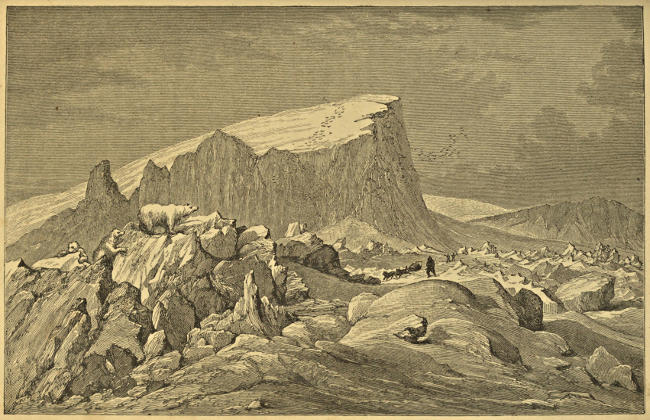

26. Of all the ice-formations in the Arctic Seas, icebergs are the most enormous. “It is well known that ice is not by any means so heavy as water, but readily floats upon its surface. Consequently whenever a glacier enters the sea, the dense salt water tends to buoy it up. But the great tenacity of the frozen mass enables it to resist the pressure for a time. By and by, however, as the glacier reaches deeper water, its cohesion is overcome, and large fragments are forced from its terminal front and floated up from the bed of the sea to sail away as icebergs.”[3] This process is sometimes called “the calving” of the glaciers; and the direction of the cleavage is a pre-indication of the forms of the masses when detached. The characteristic features of icebergs are their simple outline, differing widely from the fantastic shapes which the fragments of sea-ice tend to assume; their great height as compared with their breadth—their greenish-blue colour—their distinct stratification—their slight transparency—and the roughly-granulated character of their ice. Icebergs with long, sharp-pointed peaks, like those exhibited in numerous illustrations, have no[9] real existence. It is only fragments of field-ice, raised up by pressure, exposed to the action of waves and the process of evaporation which are transformed into fantastic shapes. Icebergs are generally of a pyramidal or tabular shape, and in time they are usually rounded off into irregular cones. They vary in height from 20 to 300 feet. Sir John Ross (1818) mentions an iceberg of 51 feet; Baffin (1615) of 240 feet; Parry (1819) of 258 feet; Kane (1853) of 300 feet; and Hayes (1861) one 315 feet high, the depth of which below the water-line he estimated at half a mile. On the coast of East Greenland, Scoresby once counted 500 icebergs, some of which reached the height of 200 feet; and during the second German North-Pole expedition, we saw many at the mouth of the Kaiser Franz-Josef fiord which measured 220 feet in height. In Austria Sound, and on the east coast of Kron-Prinz Rudolph’s land, their altitude varied from 80 to 200 feet. From the covering of mist which envelops them, icebergs generally appear much higher than they really are, and their depth below the surface is not so considerable as is generally supposed. In an iceberg 200 feet above the water, a total height of 600 to 800 feet may, as a mean, be inferred. It is only glaciers of a very great size which shed icebergs; smaller glaciers, like those of Novaya Zemlya, only strew the sea with a multitude of fragments which resemble broken sea-ice. Hence the appearance of icebergs is connected with the proximity to glacier-covered lands, and with the currents which prevail along their coasts. Baffin’s Bay, Smith’s Sound, East Greenland, the South-East of Greenland, Austria Sound, are the principal places where they collect together and lie like fleets before the entrances of bays and gulfs. Under-currents of the sea take them not unfrequently in directions contrary to the drift of the field-ice, which depends only on upper-currents; and abnormal winds may sometimes carry them out to seas where they have been seldom or never seen.[4] This appears to be the case even with those met with on the north-west coast of Novaya Zemlya. On the other hand, they have never been seen on the coasts of Siberia, which have no glaciers.

27. The constant displacement of the centre of gravity of an iceberg, resulting from the unsymmetrical decrease of its form, causes its periodical oversetting; and the different temperature of the internal and external ice is the principal cause of its rending asunder with a noise like thunder; a process which occurs generally in the height of summer.

1. Although it be impossible to give any one, who has not with his own eyes seen the Arctic Sea, a perfectly clear conception of its character, the phenomena described in the preceding chapter are sufficient to indicate the difficulties and dangers to which its navigation is necessarily exposed. And to these difficulties and dangers, formidable enough in themselves, are often added the evil influences of preconceived theories and exaggerated expectations, usually followed by bitter disillusions. The calm judgment, which, to all the bold plans of navigation within the Polar basin, opposes distrust in their feasibility, while it points to the hundred expeditions which have at last returned home after penetrating but a little way into the frozen sea, is an attainment of slow growth. Years, too, must be devoted to the theoretical study of the Polar question, to the examination of all that predecessors have experienced and recorded. But this study is very important to Polar navigators; for the discoveries which they too readily regard as exclusively their own prove sometimes to have been made centuries before them.

2. A most essential element of success is the choice of a favourable ice year; and the commander of an expedition must possess sufficient self-control to return, as soon as he becomes convinced of the existence of conditions unfavourable for navigation. It is better to repeat the same attempt on a second or even a third summer, than with conscious impotence to fight against the supremacy of the ice.

3. Polar navigators have learnt in the school of experience to distinguish between navigation in the frozen seas remote[12] from the land, and navigation in the so called coast-waters. The former is far more dangerous, entirely dependent on accident, exposed to grave catastrophes, and without any definite goal. It affords no certainty of finding a winter harbour for the long period when cold and darkness render navigation impossible. On the other hand, a strip of open water, which retreats before the growth of the land-ice only in winter, forms itself along coasts, and especially under the lee of those exposed to marine currents running parallel to them; and this coast-water does not arise from the thawing of the ice through the greater heat of the land, but from the land being an immovable barrier against wind, and therefore against ice-currents. The inconstancy of the wind, however, may baffle all the calculations of navigation; for coast-water, open as far as the eye can reach, may be filled with ice in a short time by a change of the wind. Land-ice often remains on the coasts even during summer, and in this case there is nothing to be done but to find the open navigable waters between the extreme edge of the fast-ice and the drift-ice. Should the drift become pack-ice, the moment must be awaited when winds setting in from the land carry off the masses of ice blocking the navigation, and open a passage free from ice, or at least only partially covered with drift-ice. It is evident that navigation in coast-waters must be slow and gradual, though it has always been attended with the greatest advantages. Barentz was the first who tested its value; but it was Parry, the most distinguished of all Polar navigators, who discovered its full importance, and from his day it has been accepted as an incontrovertible canon of ice-navigation. On this point he himself says: “Our experience, I think, has clearly shown, that the navigation of the Polar Seas can never be performed with any degree of certainty without a continuity of land. It was only by watching the openings between the ice and the shore that our late progress to the westward was effected; and had the land continued in the desired direction, there can be no question that we should have continued to advance, however slowly, towards the completion of our enterprise.”[5]

4. The successes of the English in the North American Archipelago were the result of this mode of navigation. Its principle is to search for and sail along the network of narrow channels when the main passage is blocked by pack-ice, and to turn to account the narrowest opening between the ice and the land. In the Siberian coast expeditions also this method of constantly following the coast-waters has been successfully observed. Where coast-water does not exist, or only to a limited extent, as on the East Coast of Greenland, this method is of course impracticable. The fate of the second German North Pole expedition is an illustration of this; it was ordered to penetrate in this direction, and its failure was inevitable. On the other hand, all the unsuccessful attempts of expeditions to penetrate northward from Spitzbergen—expeditions whose course and termination resemble each other as one egg resembles another—may be reckoned among those in seas remote from land. To the same category belong the expeditions for the discovery of a north-east passage, and simply because of the great extent of frozen sea between Novaya Zemlya and Cape Tcheljuskin.

5. In the frozen sea remote from the land, from 200 to 300, or at the most 400, nautical miles must, according to all past experience, be regarded as the greatest distance which a vessel is able to compass, under the most favourable conditions, during the few weeks of summer in which navigation is possible. The fact that Sir James Ross at the South Pole, and Norwegian fishermen in the Sea of Kara, accomplished still greater distances, only proves that they were little or not at all impeded by ice. Ross observed that the ice-floes of the Southern Arctic Seas are smaller than those of the Northern: “The cause of this is explained by the circumstance of the ice of the southern regions being so much more exposed to violent agitations of the ocean, whereas the northern sea is one of comparative tranquillity.”[6] The rarer occurrence of land at the South Pole permits freer scope to the currents of the sea, diminishes the opportunity for the growth of ice on the coasts, tends to widen the passages in the network of water-ways, and thus facilitates navigation. Even the swell of the sea within the ice is observed in the[14] South Polar Ocean, while it is never seen in the North. Besides the greater hindrances peculiar to the whole North Polar Sea, there is the specially unfavourable circumstance, in the case of the North-East passage, that the shallowness of the Siberian Sea prevents a close navigation of its coasts.

6. The choice of the most appropriate season is another important consideration in ice-navigation; for this period does not fall at the same time in all seas, and the disregard of season was a common cause of the failures of the expeditions of earlier centuries. Since the frozen sea remains unbroken and almost unaffected by the action of the sun even in June, and at that time extends far to the south, it is evident that all attempts to force a passage in that month are labour thrown away. The ice-barrier retreating northward, or the transformation of pack into drift-ice, leaves free navigable water four or five weeks later. The month of August is the best time for ice-navigation in Baffin’s Bay; the end of July or beginning of August on the East Greenland coasts; the second half of August and the beginning of September in the Spitzbergen waters; and in the region of the Parry Islands the favourable opportunity ends about the beginning of September. In general, it seems that the time most propitious for all the coast-water routes, begins some weeks earlier than the corresponding period in the frozen seas remote from land. But since, even in the first weeks of September, the most promising conditions are often succeeded by a sudden reaction due to storms, to cold setting in rapidly, or to excessive falls of snow, navigation in the land-remote frozen seas, in itself so extremely hazardous, becomes specially critical, just when the ice-sheet at its minimum appears to promise the greatest results.

7. The help of steam power is an indispensable requisite, as by it a vessel is able to defy the capricious changes of the wind. The movements of a ship amid the ice are made in interminable curves, and the power to describe an arc with the least radius enables a vessel to follow up narrow and often blocked water-ways. As it is incessantly exposed to severe shocks from the ice, a paddle-wheel steamer is useless; and even in screw-steamers care must be taken to protect the propeller by a special construction.

8. The rate of speed of a vessel in the ice must necessarily be moderate. From three to six miles an hour are sufficient: and a rate of eight or ten miles would soon render her not seaworthy. But even with this reduced rate, her whole frame-work is shaken and loosened at last by the incessant shocks she sustains; and this condition of the ship becomes apparent when concussion with the ice is followed not by a noise as of thunder, but by a low, dull, groaning sound. The larger a vessel, the less her capacity to withstand these shocks, and the sooner will these signs of her diminished strength betray themselves.

9. An Arctic ship should be built with sharp rather than with full lines, so that when pressed by the ice, she may more easily escape being nipped and crushed. A ship built with what is called—in England—full lines, a full, round ship, is not easily raised but is liable to be crushed by ice-pressure. The Hansa was built in this manner, and was crushed by the first squeeze from the ice; the Germania and the Tegetthoff were both of them sharp-built ships, and stood the test of the ice excellently well. To protect it from the effects of grinding on ragged “ice-tongues,” the hull is generally iron-plated for some feet under water, and the bows are strengthened as much as possible, because this part of the ship is exposed to the greatest shocks.

10. The tactics of a ship in the ice are guided entirely by the character of the hindrances to be overcome. If the ice-fields be large and heavy, they are then generally separated by broader water-ways and “leads,” and a ship may often amid such ice follow her course for hours with few deviations subject always to the danger of being “beset” and crushed. When the passage is blocked by a barrier of ice, the situation becomes grave and serious; for such fields are not to be displaced by any force which the ship may exert, and nothing is left to the navigator but to await their parting asunder in a position as sheltered as possible. When the ice is loose and the floes comparatively small, the impeding barriers may be charged by the ship. She may then force asunder some of these floes or separate them by the continuous pressure of steam-power. In cases of this kind, large vessels have the advantage, and can bring to bear a greater amount of pressure,[16] whereas smaller ones stick fast and remain immovable. These accumulations of ice, while they make a “besetment” more likely, diminish the danger of pressure.

11. Hence it is clear that small are to be preferred to large vessels for ice-navigation, except under circumstances of rare occurrence; first, because they are more readily handled, and next, because of their greater power of resistance and of their being more easily raised under pressure from the ice. Their one disadvantage of lesser momentum is of comparatively slight consequence. The experience of all the North Pole expeditions of this century shows, that ships of 150, or at the most of 300 tons, are best suited for all purposes.

12. Iron ships have often been employed, but with no success; they are far less able to bear pressure than wooden ships, as was proved, among other things, by the fate of the River Tay in 1868, in Baffin’s Bay, and of the Sophia, a Swedish ship of discovery in the north of Spitzbergen.

13. It admits of no question, that two vessels should be employed in preference to one, and this should be accepted as a first principle whenever the means at our disposal admit of it. Both ships should also be provided with steam-power, for otherwise their separation is almost inevitable,—a danger, however, for which, under all circumstances, they must be prepared.

14. All that is commonly understood about piercing the ice by sawing and boring through it is a delusion, and arises from the misunderstanding of technical expressions. Where there is navigable water, there any one can sail—where there is none, no one. In 1869 and 1870, after coming on a cul-de-sac of ice in Greenland to the east of Shannon Island, we could not penetrate a yard further; in 1871, in loose, but solid ice, we drew away only by warping on the smaller floes, without being able to make the slightest progress, and in 1872 we were twice “beset,” in heavy ice, in spite of our steam power. The penetration of close pack-ice is an impossibility: in this case patient endurance is alone of any avail, and hence Sir John Ross so emphatically recommends the Polar navigator “never to lose sight of the two words caution and patience.”[7] If a[17] vessel, therefore, is arrested by impenetrable masses barring its way, the breaking up of the ice must be patiently awaited, and this, generally, is effected by calms, although the ebb and flow of the tide appear to have an influence on the solidity of the ice. It is then usual with sailing ships to seek the larger “ice-holes,” or keep in the freest water-ways, in order to guard against the danger of being completely inclosed. These precautions, however, are not so requisite for steam-vessels, as their power to escape quickly and in any direction secures them against this danger. A steam-vessel may even venture to fasten on to an ice-floe by means of an ice-anchor, and of course under its lee, the fires being banked up, so that by getting up steam she may shift her place as soon as the ice moves nearer. As a principle, and so far as it is possible without the exhaustion of her powers, a ship in the ice should endeavour to be in constant motion, even though this entail many changes of her course and the temporary return to a position which had been abandoned. The making fast to a floe, however, should never be attempted, except when every hope of navigating in the surrounding waters has been proved fruitless. The fastening a vessel to an iceberg diminishes, indeed, its drifting, but is, if possible, to be avoided, because of the danger of the iceberg overturning or rending asunder, things which occur far more frequently than we should be led to expect from their great appearance of stability. When a ship, notwithstanding every possible caution, is “beset,” it is then advisable to “ship” the rudder in order to protect it from injury, to which it is peculiarly liable from its unusual weight and size. A ship is exposed to considerable danger when she finds herself among icebergs in a calm; but since these are over-spread by a dazzling sheen, even in the thickest mist, the peril of the position is to be avoided at the last moment by warping.

15. As the happy choice of a sea-way is one of the essential conditions of success in ice-navigation, the ability to determine the ship’s position and to ascertain whether a surface covered with ice to the horizon, admits of being penetrated, is most desirable. Hence the employment of a balloon would be of the last importance in Arctic navigation. The advantage of being able to ascend from the ship in a balloon secured by a[18] rope, to the height of a few hundred feet, is self-evident; and, undoubtedly, the first vessel which avails herself of this great resource will derive extraordinary benefit from it.

16. From the deck of a ship even drift-ice appears to be of such solidity at a little distance as to defy navigation, while from the mast-head more water than ice may be descried. In order then to extend the horizon, a look-out, called “the crow’s nest,” is fixed on the mast-head, in which an officer is always on the watch, and from which all the operations of the vessel are directed. In a ship of the size and height of the Tegetthoff the horizon visible from “the crow’s nest” extends to about eleven miles,[8] but at the distance of even five miles the possibility of penetrating cannot be determined with sufficient exactness. It is the business of the officer in “the crow’s nest” to observe the passages through the ice and distant objects generally, as he is in the best position to fulfil this most important duty. It is the special business of the watch on the forecastle to mark what lies in the immediate neighbourhood of the vessel, and his constant care is demanded to avoid isolated ice-floes and prevent collision with them. The seaman at the helm steers the ship by the signs and calls which come to him from “the crow’s nest,” and modifies them according to those of the watch on the forecastle. The rest of the crew remove the smaller fragments of ice from the vessel’s course, special care being taken to prevent their damaging the screw.

17. While sea-currents move the ice in close and continuous lines, winds produce great disturbances in their movement, and open long “leads” in the direction of their course, which often alternate with strips of the thickest pack-ice. This movement of the ice varies with each accumulation of floes, as its rate of motion depends on the height of the ice-field, which then acts as a sail. It is ascertained by experience that calms, on the other hand, have the remarkable property of breaking up the ice. The knowledge and application of these circumstances are essential to the Arctic navigator. If the course of a ship lies across or against a current, it is constantly deflected. The deflection on the coast of East Greenland,[19] for example, amounted to five, even ten miles, within twenty-four hours; hence the importance of choosing routes with and not against the course of currents.