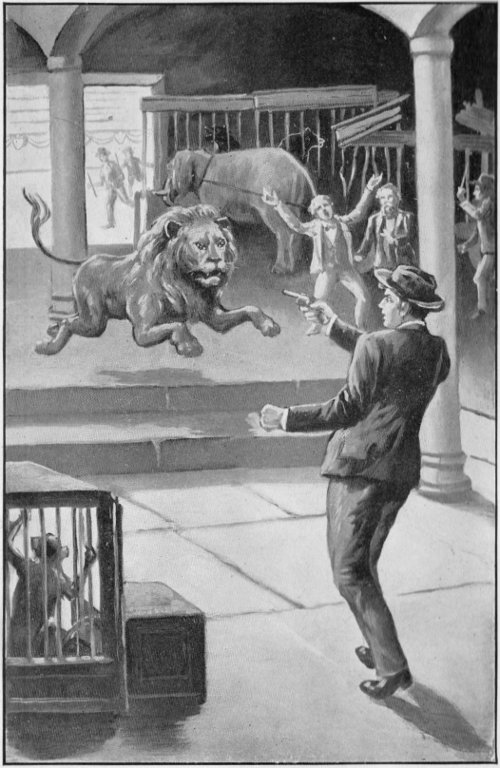

IT WAS THE LAST SHOT. AS HE FIRED IT LARRY LEAPED TO ONE SIDE TO ESCAPE THE LION’S CLAWS.

OR

STRANGE ADVENTURES IN A

GREAT CITY

BY

HOWARD R. GARIS

AUTHOR OF “FROM OFFICE BOY TO REPORTER,” “THE ISLE OF BLACK FIRE,” “THE WHITE CRYSTALS,” ETC., ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

New York

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Publishers

Copyright, 1907, by

CHATTERTON-PECK CO.

Larry Dexter, the Young Reporter

My Dear Boys.—Those of you who were interested in the first story of this series, telling how Larry Dexter rose from a copy boy to become a reporter, may desire to follow his further adventures as a newspaper worker. Many of the occurrences told of in this volume are actual ones. In some I participated personally. In others newspaper friends of mine were concerned, though I have made some slight changes from what actually happened.

The tracing of the blue-handed man, who blew open the safe by means of nitro-glycerine, is an actual fact, having taken place in the city where I live. He was arrested afterwards because a detective observed the stains left by the acid on his fingers. The riot in Chinatown is similar to several that have occurred there, and kidnappings, such as befell Jimmy, are common enough in New York. There are few reporters, especially on the large papers, who have not gone through as thrilling incidents as those which happened to Larry, for, as I can vouch from many years’ experience, a newspaper man’s life is anything but a quiet and uneventful one.

Yours sincerely, Howard R. Garis.

July 1, 1907.

“Copy!”

The city editor’s voice rang out sharply, and he held in his extended hand a bunch of paper, without lifting his eyes from the story he was going over with a correcting pencil. There was no answer save the clicking of half a score of typewriters, at which sat busy reporters.

“Copy!” cried the editor once more. There was a shuffle among a trio of boys on the far side of the room.

“Copy! copy!” fairly shouted the exasperated editor, as he shook the papers, looking up from his work towards the boys who were now advancing together on a run. “What’s the matter with all of you? Getting deaf, or are you tired of work? When you hear ‘Copy’ called at this time of day you want to jump! Now all the way up to the composing room with that, Bud. It’s got to make the first edition!”

“Yes, sir!” exclaimed Bud Nelson, head copy boy on the New York Daily Leader, one of the largest afternoon papers of the metropolis, as he raced upstairs to where the clicking type-setting machines were in noisy operation.

“You boys must be more lively,” went on Mr. Bruce Emberg, the city editor. “This is not a playroom nor a kindergarten. You must learn to jump up whenever you hear the assistant city editor or myself call ‘Copy.’ I make some allowances for you boys who have not been here long, but it must not occur again.”

The two remaining lads went back to their bench looking a little startled, for, though Mr. Emberg was a kind man, he could be severe when there was occasion for it.

“Did he give you a laying-out?” asked Bud, of his companions, when he returned.

“I just guess yes,” replied Charles Anderson, the tallest of the copy boys. “You ought to have heard him!”

“I was so busy telling you fellows about the party last night I didn’t hear him call,” said Bud. “We’ll have to be more careful, or we’ll lose our jobs.”

“Copy!” called the editor again, and this time the three reached the desk almost at the same instant.

“That’s the way to do it,” remarked Mr. Emberg. “That’s what I like to see.”

For the next few minutes there was a busy scene in the city room of the Leader. Reporters were writing like mad on their typewriters, and rushing with the loose sheets of paper over to the desk of the city editor or his assistant. These, and two copy readers, rapidly scanned the stories, made whatever corrections were necessary, put headings, or “heads,” as they are called, on them, and gave them to the copy boys.

The lads ran out to the pneumatic tube that shot the copy to the composing room, or, in case of an important story, took it upstairs themselves so that it would receive immediate attention from the foreman.

The boys were running to and fro, as if in training for a race, typewriters were clicking as fast as though the operators were in a speed contest, the editors were slashing whole pages from stories to make them shorter, and the copy readers were doing likewise.

“Hurry up that stuff, Jones!” exclaimed the editor to one reporter. “You’ve only got two minutes!”

“Here it is!” cried Jones, yanking the last page from his typewriter.

For two minutes there was a wilder scene of activity than ever. Then came a comparatively quiet spell.

“That’s all we can make for the first,” remarked the editor, with something like a breath of relief. “We did pretty well.”

The editor looked over a book that lay open in front of him on his desk. The cover was marked “Assignments,” and it was the volume in which memoranda of all the items that were to be gotten that day appeared. The editor glanced down the page.

“Here, Larry!” he called to a tall, good-looking youth, who was seated at a small desk. “Get this obituary, will you? It’s about a man over on the West Side. He was ninety-eight years old, and belonged to a well-known New York family.”

“Shall I get his picture?” asked Larry Dexter, as he came forward to go out on the assignment.

“No, we haven’t time to make it to-day. Just get a brief sketch of his life. Hurry back.”

Larry got his hat from the coat room, and left the office. He was the newest reporter on the Leader. The other reporters spoke of him as the “cub,” not meaning anything disrespectful, but only to indicate that he was the “freshman,” the apprentice, or whatever one considers the beginner in any line of work. Larry was a sort of fledgling at the business, though he had been on the Leader a number of months.

He began as a copy boy, just like one of the lads whom Mr. Emberg had cautioned about being in a hurry. Larry, with his mother, his sisters, Lucy, aged thirteen, and Mary, aged five, and his brother, James, lived in a fairly good tenement in New York City. They had come there from the village of Campton, New York, where Larry’s father, who had been dead a few years, once owned a fine farm. But reverses had overtaken the family, and some time after Mr. Dexter’s death the place was sold at auction.

When the place had been disposed of, Mrs. Dexter desired to come to New York to live with her sister, Mrs. Edward Ralston. But, as related in the first volume of this series, entitled, “From Office Boy to Reporter; or, The First Step in Journalism,” when Mrs. Dexter, with Larry and the other children, reached the big city, they found that Mrs. Ralston’s husband had been killed a few days before in an accident. Mrs. Ralston, writing a hasty letter to her sister, had gone to live with other relatives in a distant state.

But Mrs. Dexter did not receive this letter on time, in consequence of having hastily undertaken the journey from Campton, and so did not hear of her sister’s loss until she reached the house where Mrs. Ralston had lived. The travelers made the best of it, however, and were cared for by kind neighbors.

Larry soon secured work as an office, or copy, boy on the Leader, through one day being able to help Harvey Newton, one of the best reporters on the paper, at an exciting fire.

In those days Larry had trouble with Peter Manton, a rival copy boy, and he was kidnapped by some electric cab strikers who thought he was a reporter they wanted to pay off an old score on. The lad and Mr. Newton were sent to report a big flood in another part of the state, where the big dam broke, and where many persons were in danger of being drowned.

While in the flooded district Larry met his old enemy, Peter, and there was a race between them to see who would get some copy, telling of the flood, to the telegraph office first. Larry won, and for this good work was promoted from an office boy to be a regular reporter. In the course of his duties as a copy boy he once saved a valuable watch from being stolen by pickpockets from a celebrated doctor, and the physician, in his gratitude, operated on Larry’s sister Lucy, who suffered from a bad spinal disease, and cured her.

This made the family feel much happier, as now Lucy could go about like other girls, and did not have to spend many hours in a big chair. Larry’s advancement also brought him a larger salary, so there was no further need for Mrs. Dexter to take in sewing. They were able also to move to a better apartment, though not far from where they had first settled.

Larry was able to put a little money in the bank, to add to the nest-egg of one thousand dollars which he received as a reward for finding the Reynolds jewels, though the thieves were not apprehended.

Larry had been acting in his new position as reporter about eight months when, on the morning that our story opens, he was sent to get the obituary of the aged man. In this time he had learned much that he never knew before, and which would not have come to him in his capacity as copy boy. He had, as yet, been given only easy work, for though he had shown “a nose for news,” as it is called, which means an ability to know a story when it comes one’s way, Mr. Emberg felt the “cub” had better go a bit slow.

The young reporter managed to get what information he wanted without much trouble. He came back to the office, and wrote it up by hand, for he had not learned yet to use a typewriter. While he was engaged on the “obit,” as death accounts are called for brevity, he had his eyes opened to something which stood him in good stead the rest of his life.

The first editions of other New York afternoon papers, all rivals of the Leader, had come into the Leader office. Mr. Emberg was glancing over them to see if his sheet had been beaten on any stories; that is, whether any of the other journals had stories which the Leader did not have, or better ones than those on similar subjects that appeared in the Leader.

“Hello! What’s this?” the city editor exclaimed, suddenly. “Here’s a big story of a fight at that Eleventh Ward political meeting, in the Scorcher. Who covered that meeting for us?”

“I did,” replied a tall, thin youth.

“Did you have anything good in your story?” the editor asked.

“No—no, sir,” stammered the youth, as he saw the angry look on the editor’s face.

“Why not?”

“Because there wasn’t any meeting,” replied the luckless scribe. “It broke up in a free fight!”

“It what?” fairly roared the city editor.

“It broke up in a fight. The candidates tried to speak, but the crowd wouldn’t let ’em. They called ’em names, and then they made a rush, and upset the stand, and there was a free fight. I couldn’t hear any of the speeches, so I came away.”

“You what?” asked the editor, trying to speak calmly. The room seemed strangely quiet.

“I came away. I thought you sent me to report the political meeting, but there wasn’t any. It broke up in a fight,” repeated the reporter.

“I thought you said you were a newspaper man,” the city editor remarked. “I wouldn’t have hired you if I knew you had had no experience.”

“I did have some. I—I,” began the unfortunate one.

“It must have been as society scribbler on the Punktown Monthly Pink Tea Gazette,” exclaimed Mr. Emberg. “Why, you don’t know enough about the business to report a Sunday school picnic.

“If you were sent to a house to get an account of a wedding,” went on Mr. Emberg, “and while there the house should burn down, and all the people be killed, I suppose you would come back and say there wasn’t any wedding, it was a fire! Would you?”

“No—no, sir.”

“Well, I guess you would! I don’t believe you’re cut out for the newspaper business. The idea of not reporting a meeting because it broke up in a fight! It’s enough to make—but never mind! You can go to the cashier and get what money is coming to you. We can’t afford to have mistakes like that occur. This is the best story in many a day. Why, they must have had a regular riot up there, according to the Scorcher. Here, Smith,” the city editor went on, turning to an older reporter, “see what there is in this, and fix up a story,” and Mr. Emberg handed over the article he had clipped from the rival paper. It was a bad beat on the Leader.

“I hope I never make a mistake like that,” thought Larry, as he turned in his article. “My, that was a call-down!”

The unfortunate reporter who had made the mistake, and who had been discharged in consequence, left the room. He had gained his position under somewhat false pretenses, and so there was little sympathy felt for him.

“We don’t want careless work on the Leader,” went on Mr. Emberg, speaking to no one in particular. “We want the news, and those who have no noses for it had better look alive. We’re in the news business, and that’s what we have to give the people.”

The reporter, to whom Mr. Emberg had given the clipping, soon ascertained that, in the main, it was correct. So a story was made up concerning the Eleventh Ward meeting, and run in the second edition of the Leader, much to the disgust of the city editor, who hated to be “beaten.”

The rebuke the unfortunate reporter received produced a feeling of uneasiness among the others on the staff of the Leader, and there were many whispered conferences among the men that afternoon. However the “ax” did not fall again, much to the relief of several who knew they had not been doing as well as they might—the “ax” being the reporter’s slang for getting discharged.

When the last edition had been run off on the thundering presses in the basement, the reporters gathered in small groups in different parts of the room, and began talking over the events of the day. Larry saw his friend Harvey Newton come in from an assignment.

“How did you make out to-day, Larry?” asked Mr. Newton.

“Pretty fair,” responded the boy. “I didn’t have any big stories, though.”

“They’ll come in time. Better go slow and sure.”

“Did you strike anything good?”

“Not much. I’ve been down to City Hall all day, working on a tip I got of some land deal a political gang is trying to put through. Something about a big tract in the Bronx, but I didn’t land it.”

The remark made Larry stop and think. He remembered his mother had, among her papers, a deed to some land in that section of New York City called the Bronx, because it was near a small river of that name. The land had been taken by Mr. Dexter in connection with some deal, and had never been considered of any value. One day, as told in the previous volume, Mrs. Dexter was about to destroy the old deed, but Larry restrained her. He thought the land might some day be of value. So the document was put away.

When Mr. Newton spoke Larry wondered if, by any chance, the land the reporter mentioned as being that over which a political deal was being made, could be located near that which was represented by the old deed. He made up his mind to speak of it some time.

It was now about four o’clock, and, as the reporters went off duty in half an hour, Mr. Emberg was busy over the assignment book.

The Leader was an afternoon paper, but sometimes there were things occurring at night that had to be “covered” or attended to in order to get an account of them for the next day. Usually only very important events were covered at night by the Leader, since the morning papers, or news associations, got accounts of them.

Mr. Emberg came over toward Larry with a slip of paper in his hand.

“How would you like to try your hand at a funny story?” the city editor asked the boy.

“I’d like to, only I don’t know that I could do it. What sort of a story is it?”

“Amateur night at a theater. Did you ever see one?”

Larry said he had not, and Mr. Emberg explained that the managers of certain cheap theaters, in order to get some variety, frequently had amateur nights at their playhouses. They would allow any one who came along to go on the stage between the acts of the regular performance, and sing, dance, recite, do feats of strength, or whatever the amateur considered his specialty.

The audience, for the most part made up of young men and women, seldom had much sympathy to waste on the amateurs, and it must be a very brave youth or maiden who essayed to do a “stunt” under the circumstances.

“Here are two tickets to the Jollity Theater,” said Mr. Emberg. “Go up there to-night, take someone with you if you like, and give us a good funny story to-morrow.”

Larry was delighted at being able to go to the theater without paying, but he was a little doubtful of his ability to do the story. However, he resolved to try. He told his mother of it at supper last night.

“I’ll take Jimmy with me,” said Larry.

“I’m afraid your brother’s too young to go out, as you will have to stay rather late,” said Mrs. Dexter. “Can’t you take Harry Lake?” referring to a boy who lived on the floor below the Dexter apartments.

“I guess I will,” replied the young reporter, and soon he and Harry were on their way to the theater.

The play was one of the usual melodramatic sort but to Larry and Harry it was very interesting. They watched eagerly through the first act, as did hundreds around them, but there was more interest displayed when the manager came before the curtain.

He announced that a number of amateurs had come to go through their various “turns,” and added that they would be allowed to stay and amuse the audience as long as the latter seemed to care for the offerings. When too much displeasure was manifested the performers would be obliged to withdraw, being forcibly reminded to leave, sometimes, by being pulled from the boards by a long-handled hook which the stage hands stuck out from the wings, or sides of the stage.

“Johnny Carroll, in a song and dance specialty,” announced the manager as the first number, and then he retired to give place to Johnny. The latter proved to be a tall, thin youth, who shuffled out upon the stage and stood there looking about rather sheepishly.

“Ladies an’ gen’men,” he began in such weak tones that someone shouted:

“Take your voice out yer pocket!”

“I’m goin’ t’ dance a jig!” cried Johnny, defiantly, and the orchestra struck up a lively tune. Three times the young performer tried to get into step, but something seemed to be the matter with his feet, for they would not jig. A general laugh ran around.

“I’m goin’ t’ sing!” cried Johnny, in desperation. “I’ll give you that latest song success, entitled, ‘Give Me Another Transfer, This One Has Expired,’” and the orchestra began playing the opening strains. Johnny opened his mouth to sing, but, as his voice was rather less harmonious than a crow’s, he was met with howls of laughter.

“T’ou’t ye was goin’ t’ sing!” someone in the top gallery shouted.

“Give me a chanst!” pleaded the performer.

“Get the hook! Get the hook!” shouted several, and out from the wings came an instrument like a shepherd’s crook. Johnny was removed from the stage, protesting in vain.

“Sammy Snipe will play the mouth organ,” announced the manager, and Sammy came on. He seemed to be an old hand at the turn, for he entered with an air of confidence, and was greeted with some applause. He lost no time in talking, but began to play, and made not unmusical sounds on the harmonica. He made a “hit” with the audience, and there were no discouraging remarks. Sammy played several popular airs, and then tried to play a jig and dance it at the same time. Sammy would have done better, however, to have stopped when he had the approval of his audience. Unfortunately he could not divide his attention between his playing and his dancing. While he could do either separately, when he essayed both he found he had tried to cover too much territory. He started off on a lively air, but, no sooner had he danced a few steps, than he forgot to keep playing, and he soon lost time. Then he tried to start dancing, and come in with the music when he had the jig going well. This, too, failed, for he soon forgot to dance, and only played.

“Take him away; he’s no good!” the audience shouted, and then came the fatal call: “Get the hook!” and Sammy was removed.

Next a young woman appeared who tried to recite “Curfew Shall Not Ring To-night!” The audience either had no regard for the curfew, or did not care to hear anything tragic. The young woman got as far as the third line when there was a series of groans that indicated anything but enjoyment.

“Ding-dong! Ten o’clock! Time’s up!” called someone, and the performer retired in confusion.

Larry and Harry were enjoying the efforts of the amateurs more than they had the real show. They were anxious for the second act to be over to see what the unprofessional performers would offer next.

When the curtain was rung down the second time, leaving the heroine in great trouble and distress, the next amateur performer was another young woman who wanted to recite. She selected “Paul Revere’s Ride,” and began in a loud tone: “Listen, my Children——” but she had only gone that far when someone in a high falsetto voice called out:

“Oh mercy, mother, did you put the cat out, and lock the door?”

This was too much for the elocutionist, and she rushed off the stage in confusion. Next appeared a tall young man with light hair, and a purple necktie, who tried to sing: “Come Where My Love Lies Dreaming.” He managed to make himself heard through two lines, and then such a chorus of yells, whistles, and cat-calls, mingled with “Get the hook!” broke out, that he had to stand helpless. He was game, however, and Larry could see, by the motion of the youth’s lips, that the performer was going through with the song. But not a sound of it was heard, and there was no second verse.

This was followed by two boys who managed to get through some buck and wing dancing, winning hearty applause. Next there was a youth who essayed a tumbling act.

He, too, seemed to please, and did not get the “hook.” Not so fortunate, however, was the following performer, who was announced as a “strong man.”

Several stage hands carried a number of heavy weights out on the boards. The “strong man” in pink tights, making several bows, lifted a few dumb-bells.

“Aw, I kin do that meself!” exclaimed a disgusted newsboy, leaning far over the edge of the gallery. “Do a hard one, or go back home.”

The performer next tackled a big dumb-bell that must have weighed several hundred pounds. Either he had underestimated its heft, or he had overestimated his powers, for he could not budge it. He strained and tugged, but the bell did not move.

“Fake! No good! Get the hook!” were some of the cries that greeted the man.

He was pulled from the stage by some of the hands, and two of them came on to move the weights. Then it was disclosed that a trick had been played on the “strong” man for the big dumb-bell was merely made of wood, painted to resemble iron. It had been fastened to the floor with hooks, which accounted for the inability of the performer to move it.

One of the stage hands, unfastening the bell, lifted it easily with one hand. Then the laughter broke out louder than ever, Larry and Harry joining in.

Between the third and fourth acts other amateurs appeared. Some did fairly well, but most of them had a bad attack of stage fright, or were scared by the remarks made to them by the audience. Altogether it was a funny experience.

Larry was so anxious to make a good story that he sat up after he reached home that night, and wrote it out, just as he had seen it. He gave it a lively touch, and made the most of the situations. It was with some anxiousness, however, that he placed the story on Mr. Emberg’s desk the next morning.

“What’s this?” asked the city editor.

“That story of amateur night,” replied Larry.

“Oh, yes, I’d forgotten all about it. I’m glad you have the copy in early, as I want you to make a quick trip out of town.”

“Any more floods?” asked Larry, thinking of the big one he had helped cover when he was a copy boy.

“Not this time; this is only to take a run over to New Jersey, to a little town called Cranford.”

“What’s the matter out there?”

“I want you to see Professor Allen. He is to deliver a lecture at the dinner of the Engineers’ Club to-night, and he has promised a copy of his remarks in advance.”

Larry was soon on his way, crossing the Hudson River on the ferry to the New Jersey side, where he took a train for Cranford. He found Professor Allen’s house without much trouble, and inquired for the gentleman.

“I don’t believe you can see him,” replied the girl who answered the door.

“Why not; isn’t he at home?” asked Larry.

“Well, he is and he isn’t,” replied the servant. “You see he’s out in his laboratory making experiments, which is what he’s most always up to, and he hasn’t been in to his meals for a week.”

“Hasn’t he eaten for a week?” asked Larry, in some surprise.

“Oh, bless your heart, of course he’s eaten, but he will not come to the table. His wife has to go out to the laboratory with a plate of victuals and a cup of coffee, and fairly feed him.”

“What’s the trouble?”

“Oh, you see he’s working on a new invention.”

“What sort?” asked Larry, thinking he might get a story out of it.

“Don’t ask me,” cried the servant, with a laugh, for she evidently took Larry for some boy on an errand. “It’s all about wheels and levers and steam and electricity. As near as I can get at, it’s a plan to make an automobile out of a tea kettle.”

“Don’t you suppose I could see the professor?” asked the young reporter.

“Well, you can try,” said the girl. “The laboratory is that small white building down at the far end of the yard. Go down there, and walk right in. If you knock he’ll never answer. Mrs. Allen has just fed him his breakfast, and perhaps he’ll talk to you a little.”

Larry decided this was the only way of securing what he wanted, so he made his way to the laboratory, and, remembering the injunction, entered the door and walked in.

He found himself in a large room, fairly filled with machinery and appliances of all kinds. Overhead there were shafts and pulleys, while all about the sides were benches, lathes, wheels, levers, handles, and springs of various sorts.

Down in one corner was an elderly gentleman, in rather an old and ragged suit, at work over a bench. He did not look up as Larry entered, but called out:

“Come here and give me a hand with this. I’m in a hurry.”

Larry looked around to see if the professor could be speaking to anyone else, but, finding that he was the only one in the room besides the scientist, the lad concluded he was the one addressed.

“Hurry, please,” added Mr. Allen, looking straight at Larry. “I am in the midst of an important experiment.”

Thereupon Larry went to the bench. Mr. Allen was holding one end of a long steel tube from which radiated several smaller tubes of glass. At one end of the steel tube was a rubber pipe which was attached to a gas jet, and at the other end of the tube there was another pipe which was fastened to a water faucet.

“Turn on the gas a little more, and then help me hold this tube,” spoke the scientist. “I am generating steam.”

He spoke as though it was the most natural thing in the world for Larry to be there, and give him assistance. Larry recognized that Mr. Allen was too much absorbed in his experiment to care who helped him, so the boy lent a hand.

Larry turned the gas on, and then grasped one end of the tube. Mr. Allen held the other. There was a curious rumbling sound, followed by a roar.

“Duck! She’s going to explode again!” cried Mr. Allen, dropping his end of the tube, and crawling under a table. Larry lost no time in following his example. The next instant there was a loud report, and pieces of the tube and rubber hose were flying in all directions.

“It’s all over, you can come out now,” remarked the scientist, in a quiet voice, a few seconds later.

“Does it often act that way?” inquired Larry, earnestly.

“That’s the twenty-seventh time it has blown up,” replied the professor. “I guess the glass is not strong enough for the steam.”

“Isn’t it dangerous?” ventured Larry.

“Dangerous? Of course it is! That’s what I expect in this business. But I have another tube here, and we’ll try it again. Just take your coat off, and help me.”

“I’m afraid I haven’t time,” replied the reporter. “I’m from the New York Daily Leader. I came to get a copy of your speech.”

“What’s that?” inquired Mr. Allen, sharply.

Larry repeated his statement more fully.

“Bless my soul!” exclaimed the professor. “I took you for my assistant’s son. He often helps me. I didn’t get a good look at you, I was so busy thinking about this steam problem. I hope you were not hurt when the explosion came.”

“Not a bit,” replied Larry.

“Father! Father! Are you injured?” cried a voice, and a woman, much excited, hurried into the laboratory.

“Not a bit, my dear, not a bit,” replied the professor, as he brushed the dust from his clothes. “Another tube blew up, that’s all,” and he seemed as cheerful as though the experiment had succeeded.

“Oh, those horrible, dangerous steam tubes!” exclaimed the lady. Then she saw Larry, and, observing he was a stranger, was about to withdraw.

“This is a reporter from the New York Leader,” explained the scientist. “He has come for a copy of my speech, and it’s a good thing he did. I had forgotten all about delivering it to-night. I guess I’ll go in the house, and get ready. Come with me,” he added to Larry, “and I’ll get the copy for you.”

“Thank goodness something happened to make him come back to civilization,” remarked the lady to Larry, as they walked toward the house. “He has slept in that laboratory, and taken his meals there ever since he started on this latest idea. It’s a good thing you came along, and awakened him to some realization that there’s something in this world besides those terrible steam tubes.”

“Perhaps the explosion did,” ventured Larry.

“That? It would take more than an explosion,” the lady, who was Mr. Allen’s daughter, replied. “He’s used to them.”

Larry went into the house, where, after some search, Mr. Allen found a copy of his remarks, which he gave to the young reporter.

“Come out and see me again some day,” the scientist invited Larry. “We’ll try that experiment again.”

“I’m afraid once is enough for me,” said Larry, with a smile.

He reached his office shortly after noon, and, handing in the copy of the speech, which had been gotten in advance, so as to be set up ready for the next day’s paper. Then he reported at the desk, announcing to Mr. Emberg that he was ready for another assignment.

“Take a run down to City Hall,” said the city editor. “Mr. Newton is covering it to-day, but he is busy on a story, and he telephoned in he had no time to make all the rounds of the offices. Just see if there are any routine matters he had to overlook.”

It was the first time Larry had ever been assigned to the municipal building alone. He was familiar with most of the offices and knew some of the officials by sight, as Mr. Newton had frequently taken him around to “learn him the ropes,” as he said. So Larry felt not a little elated, and began to dream of the time when he might have important assignments, such as looking after city matters and politics, matters to which New York papers pay great attention.

Larry went into several offices at the hall, and found there was no news. It was rather a dull day along municipal and political lines, and there were few reporters around the building. Larry knew some of them, who nodded to him in a friendly way, and asked him whether there was “anything new,” a reporter’s manner of inquiring for news.

As Larry had nothing he said so, it being a sort of unwritten law among newspaper men not to beat each other on routine assignments, unless there was some special story they were after.

It was almost closing hour at the hall, and within a few minutes of the time the Leader’s last edition went to press, that Larry entered the anteroom of the City Comptroller’s office. He hardly expected there would be any news, and he knew if there was it was almost too late for that day. However, he was tired, and, as there were comfortable chairs in the office, he resolved to have a few minutes’ rest, while waiting to see the official or the chief clerk to ask if there was anything new.

It was while sitting there, with his chair tilted back against a thin partition, that Larry overheard voices in somewhat loud conversation. At first he paid little attention to the matter. But when one of the voices became quite loud he could not help hearing.

“I tell you I’ve got the whole plan outlined, and we can all make big money by it,” someone remarked. “I know the lay of the land. It’s up in the Bronx.”

At that Larry began to take some notice, as he remembered he and his mother were interested in some Bronx property.

“The deal is going through, then?” asked another man.

“Sure.”

Now Larry had no intention of eavesdropping, and, if he had thought the conversation was of a private nature, he would have moved away. But it seemed the men had nothing to conceal, for they talked loudly. They were probably unaware that a transom over the door of the room where they were, was open.

“What makes you so sure the land will be valuable?” asked another voice.

“Because I know it,” came the answer from the one who had first spoken. “There’s going to be an ordinance introduced in the Common Council soon. Now all we have to do is to buy up all the lots——” What followed was in a low tone, and Larry could not hear. Then the voice went on: “It’s a great game, for it will take our votes to pass the ordinance, see?”

“Won’t there be some danger?” asked someone.

“Not a bit. There’s only one hitch. I’ve been looking the thing up, and I find that the most valuable strip of land in the whole tract is owned by some man up New York State.”

“Who is he?”

“Something like Pexter or Wexter,” was the reply, whereat Larry felt his heart beating strongly. Suppose it should happen to be the land for which his mother held the deed?

“Can we put the deal through?” several asked of the man who was doing the most talking.

“Sure we can,” was the answer. “Alderman——”

“Hush! Not so loud!” cautioned a voice.

“Close that transom,” ordered someone, and then Larry moved away, fearing the men might come out, and find him listening. He wanted to know more of the matter, for he felt sure some underhanded game was afoot.

That afternoon, on the way home, Larry told Mr. Newton of what he had heard.

“I’ll bet there’s some sort of a deal on,” said the older reporter. “Glad you happened to overhear that, Larry. I’ll get busy on the tip, and maybe we can block the game.”

“I’ve got a little trip out of town for you, Larry,” said Mr. Emberg the next morning. “There will not be much work attached to it, unless something unexpected happens.”

“What sort of an assignment is it?” asked Larry.

“The Eighth Ward Democratic Club is going to have an outing to Coney Island,” replied the city editor. “It’s a clam chowder party, and, while it is mainly to give the members of the association a good time, there may be some politics discussed.”

“I’m afraid I don’t know much about politics,” answered Larry, somewhat doubtful of his ability to cover that kind of an assignment.

“You’ll never learn any younger,” was Mr. Emberg’s rejoinder, as he smiled at Larry. “Get me a good story of what the men do, and I guess you’ll not miss much. There are going to be some games down at the beach, in the afternoon, races and so on, that may make something funny to write about.”

Mr. Emberg gave Larry a ticket to the chowder outing, and told him where to take the boat.

“You’re in luck, kid,” remarked one of the older reporters, as he saw the “cub” start on his assignment.

“How so?” asked Larry.

“Why, there’s nothing to do except enjoy the trip, eat a good dinner, and sit off in the shade in the afternoon. It’s one of the few decent things we fall into in this business.”

“Well, if I can get a good story that’s all I care about,” responded Larry, who had not been a reporter long enough to lose his early enthusiasm. He was always looking for a chance to get a good story, and no less on this occasion when there was not much of an opportunity.

Larry made his way to the dock whence the boat was to leave. He found a crowd of men at the wharf, all of them wearing gaily-colored badges, for the Eighth Ward Democratic Club was one of the most influential and largest political organizations in New York.

At the dock all was hurry and excitement. A band was playing lively airs, and a number of fat men were wiping the perspiration from their brows, for it was August, and a hot day, and they had marched half-way around the ward before coming to the boat.

Scores of men were piling good things to eat on the boat, for political outings seem to be always regarded as hungry affairs. Larry saw a number of other reporters whom he knew slightly, and spoke to them. Soon all the newspaper men formed a crowd among themselves, and found a comfortable place on the boat, where they sat and talked “shop.”

The older reporters discussed politics, and the younger ones conversed about the assignments they had recently covered. For, curiously enough, though a reporter sees much of life of various sorts that might furnish topics of conversation, no sooner do two or more of them get together than they begin discussions of matters connected directly with their work. Perhaps this is so because everything in life concerns reporters, more or less.

Lunch was served on the boat when it was about half-way to the Island, and Larry thought he never had tasted anything so good, for the salt air made him very hungry. Then such a dinner as there was when the grove where the club held its outings was reached.

There was a regular old-fashioned clam chowder and clam-bake in preparation. First came the chowder, which, instead of taking the edges from sharp appetites, seemed only to increase them. Then the members of the club and their friends strolled about, sat under trees, or gathered in little groups to talk, while the clam-bake was being made ready.

Larry thought perhaps he had better go about, and see if he could pick up any political tips. He spoke about it to one of the other reporters, but the latter said:

“There, now, don’t worry about that, Larry. The only time when politics will crop out, if they do at all, is after they’ve had their dinners. That will loosen their tongues, and we may pick up something.”

So Larry decided he might spend some time watching the men prepare the clam-bake.

First they built a big fire of wood in a sort of hollow in the ground. The blaze was so hot it was most uncomfortable to go close to it, but the cook and his assistants did not appear to mind it. They put scores of stones in the blaze, and the cobbles were soon glowing with the heat. Occasionally one would crack, and the pieces flew all about.

“Ever get hit?” asked Larry, of the cook.

“Once or twice, but I’m getting so I can dodge ’em now.”

Just then came another crack, and the cook ducked quickly, as a large piece of stone flew over his head. He laughed, and Larry joined him. When the stones were hot enough the men raked away the charred wood and embers, and then piled the stones up in a round heap. They were so hot that the men had to use long-handled rakes and pitchforks.

On top of the cobbles was thrown a quantity of wet seaweed, which sent up a cloud of vapor. Then the cook and his helpers began piling on top of the steaming weed bushels of clams, scores of lobsters, whole chickens, crabs, potatoes, corn on the cob, and other things. Then the whole mass was covered with more seaweed, and over all a big canvas was spread.

“There, now, it will cook in about an hour,” said the cook, who seemed to have removed considerable anxiety from his mind.

“Don’t you build more fire on it?” asked Larry, who had never been at a clam-bake.

“Not a bit. The hot stones do all the cooking now,” responded the cook.

And so it proved, for in about an hour the canvas was taken off, the weed removed, and there the whole mass of victuals was cooked to a turn. The men gathered around the table, places were found for the reporters, and the feast began. Larry ate so many clams, and so much lobster and chicken, that he feared he would not be able to hold a pencil to take notes, providing anyone was left alive to write about. Everyone seemed to be trying to outdo his neighbor in the amount of food consumed.

But it was a healthful way in which to dine, and no ill effects seemed to follow the clam-bake. An hour’s rest in the shade followed, and then it was announced that the games would be started.

A sack race was the first on the programme, and the contestants, of whom there were eight, allowed themselves to be tied up in bags, which reached to their necks. At the word they started to waddle toward the goal.

There was one very fat man and one thin one who seemed to be doing better than any of the others. They both took little steps inside the bags, and were distancing their competitors.

“Go it, Fatty!” called the stout man’s friends.

“You’ll win, Skinny!” shouted the advocates of the tall, thin one.

The latter began to forge ahead, and, it seemed, would win the race.

“Lie down and roll!” shouted someone to the fat man.

“Dot’s a good ideaness!” answered the fleshy contestant, who spoke with a strong German accent.

He fell upon his knees, and then toppled over on his side on the green grass over which the course was laid. There was a general laugh, most persons thinking the man had fallen, and was out of the race. But not so with the fleshy one. He began rolling over and over, his rotundity and the soft sod preventing him from being hurt. He kept his head away from the ground, and, so rapidly did he revolve that, inside of two minutes he had passed the thin man. The latter in his efforts to come in first took too long steps, his feet got tangled up inside the sack, and he went sprawling on his face.

“I vins!” exclaimed the German, as he rolled over for the last time, and bumped into the goal post.

“You didn’t win fair!” cried the thin man, trying to talk with his mouth filled with grass.

“Shure I dit!” the fleshy one exclaimed. “Vat’s der rules?”

“That’s right, he wins under the rules,” announced the man in charge of the games. “Contestants could walk, run, or roll. Fatty wins and gets the prize.”

“Vot iss dot prize?” asked the German, while some of his friends took him out of the bag.

“This beautiful medal,” replied the man in charge, and he handed the winner a large one made of leather, on which was burned a picture of a donkey. There was a burst of laughter, in which the butt of the joke had to join.

After this came a potato race, in which each contestant had to carry the tubers one at a time, in a spoon, and the one who brought the most to the goal received five dollars. Following there was a wheelbarrow contest, in which the smallest members of the club were obliged to wheel the largest and fattest ones. It was hard on the thin men, but the others appeared to enjoy it.

A swimming race to see who could catch a greased duck caused lots of fun. The men put on bathing suits, and scores of them went into the water.

“Don’t some of you reporters want to join the sport?” asked one of the entertainment committee. Some of the newspaper men did, and said so. Larry resolved to enter, for he was a good swimmer. Soon he had borrowed a suit, and was splashing around with the others. All was in readiness for the contest. The duck was released at the far side of a small cove, the swimmers starting from the opposite shore.

Such shouting, laughing, splashing, and sport as there was! Half the men had no intention of catching the duck, but, instead, took the opportunity of ducking some of their companions under water. Larry had no idea of catching the fowl, since he saw several men try, and lose their grip because of the oil on the duck’s feathers.

“Five dollars to whoever catches the bird!” shouted a man on shore, watching the struggle. At this there was a general rush for the unfortunate fowl. She was caught once or twice, but managed to slip away, leaving a few feathers behind.

“I’m going to catch her,” said Larry to himself. He waited a good opportunity when the duck was in a comparatively free space in the water. Then Larry began swimming slowly toward her. The duck did not see him approaching, and was paddling about. When about ten feet away Larry dived, and began swimming under water. He rose right under the duck, grabbed the fowl by the legs, and held her fast, swimming toward shore with his free arm.

A cheer greeted him as he waded out with the prize.

“There’s your money!” exclaimed the man who offered it, handing Larry a five-dollar gold piece.

Several other reporters gathered about Larry, who stood blushing at the attention he was attracting. He hardly knew whether to accept the money or not. One of his fellow newspaper workers saw his confusion.

“Take it,” he whispered. “It’s all in the game, and you won it fairly. I’ll keep it for you until you get dressed.”

Larry accepted the offer, and gave the money to his friend, who put it in his pocket until the lad had his clothes on once more.

There were a number of other games and sports after this, and then the members of the club, thoroughly tired out with the day’s fun, went aboard the boat for the trip home. There was not much excitement on the way back, and Larry was beginning to fear he might have missed the story.

He thought perhaps there had been politics talked which he had not overheard, and he was worried lest Mr. Emberg would think he had not properly covered the assignment.

Larry ventured to hint at this to some of the other reporters, but they all told him that, contrary to all expectations, there had been no politics worth mentioning discussed on the outing.

“Just make a general story of it,” advised the reporter who had held the money for Larry. “None of us are looking for a beat.”

So Larry made his mind easier. A little later the boat made a stop at a dock to let off several members who had decided to go the rest of the way home by train. The newspaper men, with the exception of Larry, decided, also, to go home on the railroad.

“Better come along,” they said to Larry. “You’ll get no more story.”

“Probably not,” rejoined Larry, “but I’ll stay just the same. The boss told me to keep on the job until it was over, and it isn’t over until the boat ties up at the last dock.”

“You’ll soon get over that nonsense,” said the reporter, with a laugh, as he left the craft. The boat resumed her way up the river, and Larry, who was quite tired out, was beginning to think he was to have his trouble for his pains in explicitly following instructions. There seemed no more chance for news, since most of the men were resting comfortably in chairs, or lounging half-asleep in the cabins. Even the band was too tired to play.

It was getting dusk, and Larry was wondering what time he would get home. He walked about the upper deck, and gazed off across the water.

Suddenly there sounded a commotion on the deck below him. Then came a splash in the water.

“Man overboard! Man overboard!” sung out several deckhands. “Lower a boat!”

At once the steamer was the scene of confusion. Men were running to and fro, a hurried jangle of bells came from the engine room, and the craft slackened speed.

“Turn on the searchlight!” cried someone, and soon the beams from the big glaring beacon were gleaming on the dark waters aft the boat.

“There he is, I see his head!” cried someone at the stern, casting a life buoy toward the figure of the man who had toppled over the rail.

“Who is it?”

“Who threw him in?”

“How did it happen?”

“Is he dead?”

These were a few of the confused cries that came from all parts of the steamer. But while most of the excursionists were greatly excited, the members of the crew of the craft remained calm. They quickly lowered a boat, and, by the aid of the glare from the searchlight, were able to pick out the swimming figure of the man. They headed the boat toward him, and in a little while hauled him into the small skiff. Then they rowed back to the steamer, the rail of which was crowded with anxious friends of the unlucky one.

“Did you save him?” they cried, for they could not see whether their friend was in the boat or not.

“Sure!” cried several of the crew, and one added: “He’s all the better for a little salt water!”

“This will make a good part of the story,” thought Larry, as he watched the craft drawing nearer. “I guess the other fellows will wish they had stayed aboard.”

When the skiff reached the steamer, and the crew, and rescued one, had been taken aboard, there were scores of demands to know how it all happened.

“I’ll tell you,” said the victim of the accident. “I was sleeping on two camp-stools close to the rail. I got to dreaming I was making a political speech, and I was walking up and down the platform telling the audience what a fine party the Democratic one is.

“I must have walked a little too far, for, the first thing I knew, I had stepped over the edge of the platform, and the next thing I knew I was falling. I woke up in the river, and struck out. That’s about all.”

“Lucky for you the searchlight was working,” remarked one of the man’s friends, “or you might have been on the bottom of the river by now.”

“Well, you see,” said the man, with a smile, as he wiped the water from his eyes. “I ate so many clams, lobsters, and crabs to-day that when I got down there the river thought I was a sort of a fish, and so it didn’t drown me.”

Larry made inquiry, and found out the man’s name. He made notes of the occurrence, and, the next morning, on reaching the office, wrote up a lively story of the happening.

He said nothing to Mr. Emberg about being the only reporter on the boat when the thing happened. But that afternoon, when all the other papers came out, and, like the morning issues, had no account of the rescue of the man, who was a prominent politician, the city editor said:

“I hope you weren’t ‘faking’ that story, Larry?” and Mr. Emberg looked serious, for he did not want any of the reporters to “fake,” or write untrue accounts of matters.

“No, sir, it actually happened,” said Larry, and he related how he came to be the only newspaper reporter at the scene. A little later Mr. Newton came in.

“Say,” he asked, “did we have a story of a man falling overboard on that Democratic outing? I just heard of it on the street as I was coming in.”

He had not been in that morning, being out of town on a story.

“Oh, Larry was on hand as usual,” replied the city editor, for by this time he was convinced that Larry’s account was true. “He has given us another beat.”

And so it proved, for the Leader was the only paper in New York that had an account of the incident, and nearly all of the later editions of the afternoon sheets had to use the story, copying it from the Leader.

“It was a good beat, and a good story of the outing besides,” said Mr. Emberg, shortly after the last edition had gone to press, for he liked the half-humorous manner in which Larry had written about the sack race and the other sports in which the members of the club had indulged. “You are doing fine work,” he added, at which praise Larry felt much gratified.

Things were slacking up a bit in the office, now that the paper had gone to press for the day, when one of the reporters who was looking over the front page suddenly cried out:

“Here’s a bad mistake in that account of the meeting of the County Republican Committee last night. It says Jones voted for Smith for chairman, and that’s wrong. I was there. The compositor must have made a mistake. It ought to be corrected, or it will make trouble.”

“I’m afraid it’s too late,” remarked Mr. Emberg, as he grabbed a paper to see the error. “The presses are running, and part of the last edition is off. The only way we can do is to have them smash Jones’s name, and blur it so no one can tell what it is. That’s what I’ll do.”

He tore part of the page off, marked out the name to be smashed, and called to Larry, there being no copy boys in the room then:

“Here, Larry, go down in the pressroom, and tell Dunn, the foreman, to smash that name.”

Though Larry had been on the paper some time he had never been in the pressroom. Nor did he know what the operation of smashing a name might mean, but he decided the best thing to do would be to carry the message.

He hurried down to the basement. As soon as he opened the door leading to it, down a steep flight of steps, Larry thought he had gotten into a boiler factory by mistake. The noise was deafening, and the presses were thundering away like some giant machine grinding tons of rocks to atoms.

Half-naked men were running about here and there. In one corner was a furnace full of melted lead for making the stereotype plates. Larry made his way through the maze of wheels, machinery, and presses.

He was met by a youth whose face was covered with ink.

“Where’s Mr. Dunn?” asked Larry, shouting at the top of his voice.

The youth did not bother to answer in words. He had been in the pressroom long enough to know the uselessness of trying to make himself heard above the din. He had understood Larry’s question from watching his lips, and pointed over in one corner.

There Larry found a quiet man marking something in a book.

“Mr. Emberg says to smash that name!” yelled the boy, handing over the paper. He was afraid he had not made himself heard, but Mr. Dunn seemed to comprehend, for he nodded several times, though he did not seem pleased. He hated to stop the presses, once they were running, until all the edition was off.

However, it had to be done. He left his corner, and went around the rear of the ponderous machine, where the paper, in a large roll, was fed in at one end, to emerge, folded and printed sheets, at the other. Mr. Dunn seized a rope, and yanked it. A bell rang, and the press began to slacken up.

The type from which the paper was printed was cast in one solid sheet, there being several of the sheets, just the size of a page. Each one was half-circular, and fitted around a cylinder on the press. This cylinder whirled around, and the paper, passing under it in a continuous roll, received the impressions.

Once the press was stopped Mr. Dunn crawled up into a sort of hole in front of the cylinder, Then he had the press worked slowly, until the particular page he had to reach came into view.

Next, with a hammer and chisel he smashed the name of Jones so that it was a meaningless blur. After that the press started its thundering again. The remainder of the papers would not contain the name of Jones, and so there would be no danger of that gentleman coming in and demanding an apology for a misstatement made about him. Often papers have to resort to this emergency when it is too late to correct directly in type an error that has been made.

When Larry was eating supper that night he happened to glance out of the window. He saw an unusual light in the sky, and first took it for a glow from some gas furnace or smelting works across on the Jersey shore. But, as he watched, the light grew more brilliant, and there was a cloud of smoke and a shower of sparks.

“That’s a big fire!” he exclaimed, jumping up.

“You’re not going to it, are you, Larry?” asked his mother.

“I think I’d better,” he replied. “Most of the men are working to-night, and none of them may go to the blaze. If we want a good story we must be right on the spot. So I think I’ll go, though I may find Mr. Newton or someone else covering it.”

“Well, be careful, and don’t go too near,” cautioned Mrs. Dexter, who was quite nervous.

“I’ll look out for myself,” said Larry, with all the assurance lads usually have.

“Take me to the fire, I’ll help you report it,” begged Jimmy.

“Not to-night,” answered Larry. “It’s probably a good way off, and you’d get tired.”

“Then you can carry me,” spoke the little fellow, ready to cry at not being allowed to go.

“You stay here, and I’ll tell you a story,” promised Lucy, who had grown to be a strong, healthy girl since the surgical operation. “I’ll tell you about Jack the Giant Killer.”

“Will you truly?” cried Jimmy. “Then I don’t care about the old fire.”

He climbed up into his sister’s lap, and soon was deeply interested in the story. Larry got on his hat and coat, and started out on the run. He found a big crowd in the street, hurrying toward the fire.

“They say it’s a gas tank,” said someone.

“I heard it was an armory,” remarked another.

“It’s neither; it’s a big hotel, and about a hundred people are burned to death,” put in a third.

“Whatever it is, it’s surely a big fire,” was a fourth man’s response as he started to run.

Larry wanted to get to the fire in a hurry, so he asked the first policeman he met where the blaze was. Learning that it was well up town, though the glare in the sky made it seem nearer, Larry decided to get on an elevated train to save a long walk.

As he neared the scene he could see the sky growing brighter, and the cloud of smoke increasing in volume. The trail of sparks across the heavens became larger. Down in the street an ever-increasing throng was hastening toward the conflagration.

Larry dashed from the train as it slacked up at the station nearest the fire. He ran down the stairs, and through the streets. As he came into view of the blaze he saw it was a big drygoods store, which was a mass of fire. It evidently had secured a good start, as every window was belching tongues of yellow flame.

Larry found a crowd of policemen lined up some distance away from the conflagration, keeping people back of the fire lines. Fortunately Larry had a newspaper badge with him, and the sight of this, with a statement that he was from the Leader, soon gained him admittance within the cordon.

He could not but think of the first time he had been at a fire in New York, how he had helped Mr. Newton, and, incidentally, got his place on the paper.

But there was no time for idle speculation. The fire was making rapid headway, and, in response to a third and fourth alarm that the chief had sent in, several more engines were thundering up, and taking their places near water hydrants, their whistles screeching shrilly, and the horses prancing and dancing on the stones from which their iron-shod hoofs struck sparks in profusion.

Larry made a quick circle of the building, which occupied an entire block, but failed to see any reporters from the Leader. He knew it was only chance that would bring them to the place, since most of them had assignments in different parts of the city.

“I guess I’ll have to cover this all alone,” thought Larry. “And it’s going to be a big job.”

In fact, it was one of the worst and largest fires New York ever had. It was no small task for several reporters to cover it, and for a young and inexperienced one to undertake it was almost out of the question. But Larry decided that he would do his best.

He went at it in a business-like way, noting the size and general shape of the building, and how the fire was spreading. Then he found how many engines were on hand, and from a group of policemen, who had nothing in particular to do except keep the throng back, Larry learned that the fire had been discovered in the basement about half an hour before. One of the bluecoats told how two janitors in the place had been obliged to slide down a rope, as they were caught by the flames on a side of the building where there were no fire escapes.

Larry got the names of the men from a policeman whose beat took in the store, and who knew them. Then he heard of several other interesting details, which he jotted down. All the while he was hoping some other Leader men would happen along to aid him, and relieve him of some responsibility. But none came.

The store was now a raging furnace. The whole scene was one of magnificent if terrible splendor. High in the air shot a shower of sparks, and every now and then a wall would fall in with a crash that sounded loud above the puffing of the engines, the shrill tootings of the whistles, and the hoarse cries of the firemen.

With a rattle louder than any of the apparatus that had preceded it, the water tower dashed up. It had been sent for when the chief saw that with the ordinary machines he would be unable to cope with the raging flames.

Under the power of compressed air the tower rose high, a long, thin tube of steel. Hose lines from several steamers were quickly attached, and the engines began pumping.

Out of the end of the tube shot a powerful stream of water that fairly tore out part of a side wall it was directed against, and spurted in on the forked tongues that were leaping up from the seething caldron of fire. A cheer went up from the big crowd that gathered as they saw the water tower come into play.

“That’ll soon settle the fire!” cried one man, on the sidewalk, near where the young reporter was standing.

“It will take more than one tower to put out this blaze,” rejoined a companion. “I believe it’s spreading.”

Others seemed to think so, too, for there were a number of quick orders from the chief, and his assistants ran to execute them. Two more water towers were soon on the scene, and then the fire seemed to be in a fair way of being put under control.

Larry was busy going from one side to the other of the big block which the burning department store occupied. He saw several incidents that he made notes of, knowing they would add interest to the story he hoped to write.

On the north side of the structure there loomed a big blank wall, that as yet had not succumbed to the flames. A number of firemen were standing near the base of it, endeavoring to break a hole through so they might get a stream of water on the flames from that side, since to get a ladder to the top of the wall was impossible, as the flames were raging at the upper edge.

Larry paused to watch them. Fierce blows were struck at the masonry with sledges and axes. Pieces of bricks and mortar flew all about. The men had made a small hole, which they were rapidly enlarging when a hoarse voice cried:

“Back! back, men! For your lives! The wall is coming down!”

The fire-fighters needed no second warning. They dropped their implements, and sprang back. Then with a crash that sounded like an explosion, the entire wall toppled over into the street.

Several of the firemen were caught under the débris, and pinned down. Their cries for help brought scores of their comrades up on the run, and Larry pressed forward to see all there was, in order to put it into the story.

“Look out!” called a policeman guarding the fire lines. “More danger overhead!”

Almost as he spoke, a big piece of masonry toppled down, and landed in the street not two feet from where Larry was standing, peering forward to see how the firemen fared. If it had struck him he would have been killed.

“Easy there, men!” called an assistant chief. “Go slow!”

“We don’t care for the danger! We’re going to get the boys out!” cried several of the unfortunate men’s comrades.

“All right, go ahead, I guess most of the wall’s down now,” spoke the assistant chief. “Here, you, young man!” he called to Larry. “What you doing here? Don’t you know you nearly got killed then?”

“Yes, sir,” replied Larry, trying to speak calmly. “But I’m a reporter, and I have to stay here.”

“Oh, you’re a reporter, eh?” asked the fireman, as he started in to help his men. “Well, I suppose you think you’re like a cat, and have nine lives, but you’d better be careful! Now get back a bit, while we see if any of these poor fellows are alive.”

Larry got some distance away, though not so far but that he could see what was going on. The crowd on this side had increased in size as the word went around that several firemen were buried in the ruins.

The rescuers worked madly, tearing at the hot bricks with picks and shovels. With crowbars they pried apart big masses of masonry. The lurid flames lighted up the scene with dancing tongues of fire, and the cries of the wounded mingled with the crackle of the blaze, the toots of the engines, and the hoarse yells of the men.

With loudly clanging bells several ambulances now drew up opposite where the imprisoned men were. They had been telephoned for as soon as it was known that an accident had occurred. After several minutes’ work one of the firemen was taken out. The white-suited doctor hurried to his side, and bent over the man. He listened to his heart.

“It’s too late,” said the physician. “He’s dead.”

Something like a groan went up from the unfortunate fellow’s comrades. It was quickly succeeded by a cheer, however, as another man was brought out. This one was very much alive.

“Be jabbers, b’ys!” he exclaimed, in jolly Irish accents, “it was a hot place ye took me from, more power t’ ye!” and, wiggling out of the hold of his rescuers, the fireman began dancing a jig in the light of the flames.

In quick succession half a dozen more were taken out. There were no more dead bodies, but several of the men were badly hurt, and were hurried off to the hospitals. Larry got their names from other firemen, and jotted them down.

The young reporter had almost forgotten about his narrow escape, so anxious was he to get a good account of the fire, when he was surprised to hear a voice at his side saying:

“Are you trying to get all the good stories that happen?”

Larry looked up, and saw Mr. Newton.

“Golly, but I’m glad to see you!” said Larry.

“What’s this I hear about you nearly getting caught under a wall?” asked Mr. Newton. “A policeman told me.”

“It wasn’t anything,” replied Larry. “I was trying to get close to where the accident happened.”

“There’s such a thing as getting too close,” remarked Mr. Newton, grimly. “Get the news, and don’t be afraid, but don’t go poking your head into the lion’s mouth. You can take it easier now. I’m going to help you.”

“Did you know I was here?” asked Larry.

“No. Mr. Emberg heard of the fire, and telephoned me I had better cover it.”

“It’s ’most over now,” observed Larry.

“So I see,” remarked Mr. Newton, as he noted that the flames were dying out under the dampening influence of tons of water poured on them. “You’ve seen the best part of it. I suppose it will make a good story?”

“Fine,” replied Larry. “I only hope I can write it up in good shape.”

“I guess you can, all right,” responded Mr. Newton. “I’ll help you. Perhaps you had better go home now, as your mother might be worried about you.”

Larry agreed that this was a good plan, and made his way through the crowd to a car, which he boarded for his home, arriving somewhat after midnight.

His mother was sitting up waiting for him, and was somewhat alarmed at his absence, as rumors of the big fire had spread downtown, and it was said that a number had been killed.

“I’m so glad you were not hurt, Larry,” said she. “I hope you were in no danger.”

“Not very much,” replied Larry, for he did not think it well to tell his mother how nearly he had been hurt.

When Mr. Emberg learned the next day that Larry had, without being particularly assigned to it, covered the big fire, the city editor was much pleased. He praised the lad highly, and said he appreciated what Larry had done.

The young reporter had his hands full that day writing an account of the fire. Mr. Newton gave him some help, but the story, in the main, was Larry’s, with some corrections the copy readers made.

“It’s a story to be proud of,” said Mr. Emberg, when the last edition had gone to press. “You are doing well, Larry.”

One afternoon, several days later, when Larry had been sent to the City Hall to get some information about a report the municipal treasurer was about to submit, the boy was standing in the corridor, having telephoned the story in. He saw a short, dark-complexioned man, with a heavy black mustache walking up and down the marble-paved hall. Several times the stranger stopped, and peered at Larry.

“I hope he will recognize me when he sees me again,” thought the lad.

“Hello, Larry,” called a reporter on another paper, as he came from the tax office, where he had been in search of a possible story. “Anything good?”

“No,” replied Larry. “I was down on that yarn about the treasurer’s report. You got that, I guess.”

“Oh, yes, we got that. Nothing else, eh?”

“Not that I know of. I’m just holding down the job until Mr. Newton gets back. He went out to get a bite to eat, and they didn’t like to leave the Hall uncovered.”

“Well, I guess you can hold it down all right,” replied the other. “That was a good story of the fire that you wrote.”

“Thanks,” answered Larry, as his friend went away.

All this time the dark-complexioned stranger was walking up and down the corridor. Finally he came up to Larry, and asked:

“Is your name Larry Dexter?”

“Yes, sir,” replied the reporter.

“You’re on the Leader, aren’t you?”

“That’s the paper. Why, have you got a story?”

“No,” answered the man, with a short laugh. “I don’t deal in stories, but I see you’re wide awake, always on the lookout for ’em, eh?”

“Have to be.”

“How would you like to get into some other line of business?” asked the man, coming closer, and dropping his voice to a whisper.

Larry thought the proceeding rather a strange one, but imagined the man might not intend anything more than a friendly interest.

“It depends on what sort of business,” replied the youth.

“Do you like reporting very much?” the stranger went on.

“I do, so far.”

“Isn’t it rather hard work and poor pay?”

“Well, it’s hard work sometimes, and then again it isn’t. As for the pay, I guess I get all I’m worth.”

“I’m in a position to get you a better job,” the man continued. “I’m in a big real estate firm, the Universal we call it, and we need a bright boy. I have some friends in the City Hall here, some of the aldermen, and they said you would be a good lad for the place.”

“I don’t know how the aldermen ever heard of me,” remarked Larry.

“Well, I guess you’ve been around the Hall a good bit,” the man went on. “You were at the insurance hearing, weren’t you?”

“I carried copy for one of the reporters,” said Larry.

“Well, anyhow,” resumed the stranger, “do you think you’d like to work in a real estate office? There’s plenty of chances to make money, besides what we would pay you as a salary. We could give you twenty dollars a week to start. How would that strike you?”

Larry was puzzled how to answer. The pay was five dollars a week more than he was getting, and if the man told the truth about the chance to make extra money, it might mean a good deal to the lad and his mother.

“I’ll think about it,” said the young reporter. “I’ll have to talk with my mother about it.”

“I’ve seen your mother, and she says it’s all right,” the man said, quickly. “If you want to you can come with me now, and I’ll start you in at once. You’d better come. The offer is a good one, and I can’t hold it open long.”

Now Larry, though rather young, was inclined to be cautious. It seemed strange that a man, whom, as far as the reporter knew, he had never seen before, should take such a sudden interest in him, and should even go to see Mrs. Dexter to ask if Larry could take another position. Then, too, the stranger seemed altogether too eager to get Larry to leave his position on the Leader. The man saw Larry’s hesitancy.

“I’ll make it twenty-five dollars a week,” he said. “Better come.”

“I can’t decide right away,” the boy returned. “I must see my mother.”

“Do you doubt my word?” asked the stranger somewhat angrily.

“No,” said Larry. “But even if my mother gave her permission I could not leave the Leader without giving some notice to Mr. Emberg. It would not be right.”

“Don’t worry about that,” sneered the man. “They would never bother about giving you notice if they wanted you to leave. They’d fire you in a second, if it suited them. Why should you give any notice?”

The man appeared so eager, and seemed to place so much importance on Larry’s taking the offer, that the boy became more suspicious than ever, that all was not as it should be.

“I will think it over,” said he. “If you will leave me your card I’ll write to you.”

“If you don’t take the offer at once I can’t hold it open,” said the man, in rather unpleasant tones. “However, here’s my card. If you come to your senses, and decide to work for my company, why, I’ll see what I can do for you. Though I can’t promise anything after to-day. You’ll have to take your chance with others.”

“I’ll be willing to do that if I decide to come.”

“Hello, Larry!” exclaimed a voice, and Mr. Newton came around the corner of the corridor. “You here yet?”

“I was waiting for you to come back,” replied Larry. “Mr. Emberg told me to stay, and see that nothing broke loose while you were at lunch.”

“Anything doing?”

“Not a thing.” Larry turned to see if the stranger was at his side, but, to his surprise, the man had vanished.

“What did he want?” asked Mr. Newton, with a nod of his head toward where the man had been standing.

“Why, he wanted me to leave the Leader, and take a position with some real estate firm,” answered Larry.

“Don’t you have anything to do with Sam Perkins,” said Mr. Newton.

“Is that his name?” inquired Larry. Then he looked at the card the man had given him, and read on it: “Samuel Perkins, representing the Universal Real Estate Co. Main Office, 1144 Broadway, New York. Loans and Commissions.”

“That’s who he is,” replied Mr. Newton. “What was his game this time?”

“That’s just what I was trying to puzzle out,” was Larry’s answer, as he related what the man had said.

Mr. Newton listened carefully. He nodded his head several times.

“That’s it, I’ll bet a cookie. When you go home ask your mother just what Perkins said, and let me know.”

“Why, do you think there is something wrong in his offer?”

“I can’t tell. I have my suspicions, but I’ll not speak of them until I know more. Tell me what your mother says. In the meanwhile, if Perkins comes to you again, which I don’t think he will, since he has seen me speaking to you, just put him off until you can communicate with me.”

“Do you know him?”

“Know him? I guess yes!” replied Mr. Newton. “He was mixed up in more than one boodle and land scandal with the aldermen, but we never could get enough evidence to convict him. Maybe we can this time, if he’s up to any of his tricks. Don’t forget to ask your mother all about his visit.”

“I’ll remember,” replied Larry. Then, as the City Hall was about to close for the day, they went back to the office.

That night Larry questioned his mother closely about the visit Mr. Perkins said he had paid her.

“I didn’t know his name,” said Mrs. Dexter, in telling her story. “He came to the door, and asked if you were my son. Then he said a reporter’s life was a hard one, and asked me if I didn’t think you had better get a position somewhere else. I thought he was a friend of yours, and when he said he could give you a good job in the real estate office I thought it would be a good thing, and said so.”

“Is that all, mother?”

“Well, pretty nearly. He did ask a few questions about your father.”

“What did he want to know?”

“Well, he wanted to know where we came from, where we used to live, and whether your father ever owned any land here in New York.”

“What did you tell him?”

“I said I didn’t know much about it, but that I thought your father had some papers, a deed or something, to some property in the Bronx.”

“What did he say to that?”

“He didn’t say much, only he appeared to be interested. He wanted to see the deed, but I couldn’t find it. I remember we had it one night, and I told him I thought we burned it up. Didn’t we destroy it, Larry?”

“We were going to, but, don’t you remember, I said it might be a good thing to save?” said Larry. “I have it put away.”

“I wish I had known it,” went on Mrs. Dexter. “I would have shown it to the man. He seemed very much interested in you, Larry.”

“Altogether too much,” went on Larry. “Mother, don’t trust that man. Mr. Newton knows him, and says he is almost as bad a criminal as though he had been convicted.”

“Why, I’m sure he seemed real polite,” said Mrs. Dexter. “He was very nicely spoken.”

“Those are the worst kind,” said Larry. “Don’t ever show him any of father’s old papers, particularly the deed to the land in the Bronx.”

“Why not, Larry? Is there any chance of that land ever becoming valuable? I remember your poor father saying it would never be any good. He was always sure he would never get any money out of it, as it is in the middle of a swamp. Do you think it will make us rich, Larry?”

“Hardly that, mother. In fact, it may never amount to anything. I doubt if we have even a good claim to it, as I don’t believe the taxes have been paid for a number of years.”

“Then what good is it to keep the deed? Don’t land go to the city if you don’t pay taxes?”

“Sometimes. In fact, I guess it always does. But there is some mystery about this, mother. I don’t know what it is, but I am going to find out.”

“Oh, I hope there is nothing wrong about us having the deed, Larry. I’m sure if your poor father knew there was anything wrong about it, he would never have taken the land.”