The Project Gutenberg EBook of Pictures of Hellas, by Peder Mariager

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Pictures of Hellas

Five Tales Of Ancient Greece

Author: Peder Mariager

Translator: Mary J. Safford

Release Date: April 6, 2018 [EBook #56929]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PICTURES OF HELLAS ***

Produced by Charlie Howard and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BY

PEDER MARIAGER

TRANSLATED FROM THE DANISH

BY

MARY J. SAFFORD

NEW YORK

WILLIAM S. GOTTSBERGER, PUBLISHER

11 MURRAY STREET

1888

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1888

By WILLIAM S. GOTTSBERGER

in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington

The author’s preface to “Pictures of Hellas” is so full, that the translator has nothing to add to the English version except the acknowledgment of valuable assistance rendered in “the obscure recesses of Greek literature” by Professor Andrews, Ph.D., of Madison University.

Mary J. Safford.

i

Nearly all the more recent romances and dramas, whose scene is laid in classic times, depict the period of the great rupture between Paganism and Christianity. This is true of “Hypatia,” “Fabiola,” “The Last Days of Pompeii,” “The Epicureans,” “The Emperor and The Galilean,” “The Last Athenian,” and many other works. The cause of this coincidence is not difficult to understand; for a period containing such strong contrasts invites æsthetic treatment.

The present tales derive their material from a different, but no less interesting epoch. They give pictures of the flowering of Hellas, the distant centuries whose marvellous culture rested solely on the purely human elements of character as developed beneath a mild and radiant sky.

Yet it required a certain degree of persistence to procure this material. When we examine the Greek writers to find descriptions of the men of those times or the special characteristics of the social life of the period, Greek literature, so rich in accounts of historical events, becomes strangely laconic, nay almost silent.

How entirely different is the situation of a personii who desires to sketch a picture of the Frenchmen of the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries. The whole collection of memoirs is at his disposal. In these writings the author discourses familiarly with the reader, gives him lifelike portraits of the ladies and gentlemen of the court, and tells him the most minute anecdotes of the society of that day.

Greek literature has nothing of this kind. The description of common events and the history of daily existence are forms of writing of later origin, nothing was farther from the minds of ancient authors than the idea that private life could contain anything worth noting. Herodotus and Thucydides narrated little or nothing of what the novelists of the present day seek, nay, even among the orators only scattered details are found, and strangely enough there are more in the speeches of Lysias than of Demosthenes.

Among the poets Aristophanes produces a whole gallery of contemporary characters, but indistinctly and in vague outlines; they were what would now be called “originals from the street” who, during the performance of his comedies, sat among the spectators, and whom he only needed to mention to evoke the laughter of the crowd. Something more may be gathered from Lucian and Apuleius, together with the better “Milesian” tales, especially from Heliodorus and Achilles Tatius while, on the contrary, the great Alexandrian lumber-room, owed to Athenaeus, contains more gewgaws of learning and curiosa than really marked characteristics.

iii In the obscure recesses of Greek literature, where we are abandoned by all translators, and where—as everybody knows who has devoted himself to the interpretation of the classics—only short excursions can be made, we are sometimes surprised at finding, by pure accident, useful matter. Dion Chrysostomus (VII) gives extremely interesting descriptions of life in the Greek villages and commercial towns. But what is discovered is always so scattered that only a few notes can be obtained from numerous volumes.

When I decided to turn what I had read to account, I was fully aware that a presentation of ancient life in the form of a romance or novel was one of the most difficult æsthetic tasks which could be undertaken. If, nevertheless, I devoted myself to it, I naturally regarded the work only as an experiment.

In choosing the narrow frame-work of short stories I set before myself this purpose—to sketch the ordinary figures of ancient life on a historical background. I have—resting step by step on the classic writers—endeavored to present some pictures of ancient times; but I have no more desired to exalt former ages at the expense of our own than the contrary. As to the mode of treatment—I have steadily intended to keep the representations objective, and to avoid using foreign words or giving the dialogues a form so ancient that they would not be easy to read.A The stiffiv classic ceremonies, foot-washings, etc., I have almost entirely omitted, and the archaeological and historical details have everywhere been subordinated to the contents of the story, so that they merely serve to give an antique coloring to the descriptions. Lastly, I have believed that the Greek characters ought to be completely banished from the book, and even from the notes and preface.

A So far as the idiomatic differences of the two languages would permit, the translator has endeavored to retain the simplicity of style deemed by the author best suited to his purpose.

After these general remarks I must be permitted to dwell briefly upon the different tales, partly to point out the authority for such or such a stroke and partly to give some few more detailed explanations.

Little is known of the Pelasgian epoch; but it is a historical fact that a woman was abducted at the fountain of Callirrhoë. On this incident the first story “Zeus Hypsistos” is founded, and the climax of Periphas’ death is based upon an ancient idea: a voice of fate. The belief in Phēmai or Cledones is older than in that of most oracles, and dates back to the days of Homer. When Ulysses is wandering about, pondering over the thought of killing the suitors, he prays to Zeus for a sign and omen, a voice of fate, which then sounds in a thunder-clap and, inside of the house, he hears a slave-girl wishing evil to the suitors. The old demi-god Cychreus of Salamis is mentioned by Pausanias (I. 36). It was a universal idea in ancient times that demi-gods liked to transform themselves into serpents. In the battle of Salamis a serpent appeared in the Athenian fleet; the oracle declared that it was the ancient demi-god Cychreus. In Eleusis Demeter hadv a serpent called the Cychrean, for Cychreus, who had either slain it or himself assumed its form. For the remarkable ceremonial of purification after a murder (page 58), see Apollonius’ Argonautica (IV. 702). The words: “Zeus was, Zeus is, and Zeus will be” are borrowed from the ancient hymn sung by the Dodonian priestesses, called Peleiades (doves.)

In “The Sycophant” the notes cited on pages 72–73 would be valueless, if they did not contain the punishments which, according to Attic law, were appointed for the transgressions named.

Hetaeriae was the name given to secret societies or fraternities, where six, seven, or more members united to work against or break down the increasing power of the popular government, which was exerting a more and more unendurable pressure. There were many kinds of “hetaeriae,” but the most absolute secrecy was common to all. The members were conspirators, pledged to assist one another by a solemn oath, sworn by what was dearest to them in life. The harmless hetaeriae comprised those who were pursuing no political object, but merely consisted of office-seekers whose purpose was to aid one another in the election to office or before the courts of justice. The hetaeria here described is of the latter sort; for the delineation of a political society of this kind would require a far more extensive apparatus than could be contained within the brief limits of a tale. Several of the characters in “The Hetaeria” have actually existed. The comedian Sthenelus is mentioned by Aristophanes (vesp. 1313) asvi well as the orator and tragedian Acestor (vesp. 1220; aves 31) both are sketched from the more minute details of the Scoliastae. Phanus is also mentioned by Aristophanes (equit. 1233) as Cleon’s clerk. Among the women of the tale there is also an historical personage, the foreign witch Ninus, who professed to be a priestess of the Phrygian god Sabazius. She travelled through Hellas at the time of the Peloponnesian War and reaped a rich harvest by her divination and manufacture of love potions; but her end was tragical—she was summoned before the courts as a poisoner and condemned to death (A. Schaefer, Demosth. I. 199). The main outlines of the relations between Hipyllos and Cleobule are taken from the commencement of Cnemon’s story in Heliodorus (I. 2) and the description of Sthenelus’ fall from the boards is almost literally repeated from Lucian (The Dream, 26). The account of the naval battle at Rhion is an extract from Thucydides (II. 86–92).

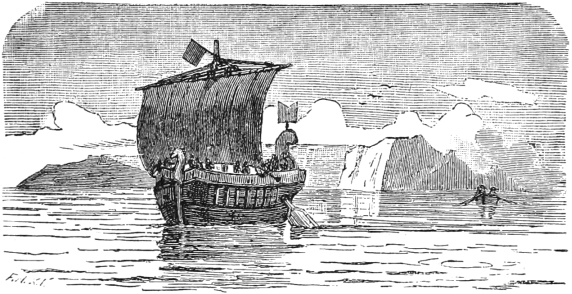

“Too Happy” is founded upon an ancient idea: the prayer for a sign and the acceptance of an omen. Piracy, which plays a prominent part in the narrative, was practised at an early period in the Ægean Sea and afterwards attained such dangerous extent that large and magnificent fleets of pirate cruisers finally threatened Rome herself with intercepting the importations of grain from Pontus. It might perhaps be considered too romantic for a disguised corsair to examine the ship lying in port before plundering her in the open sea. Quite different things, however, are reported. Thevii Phoenician pirates had secret agents who discovered where a ship with a rich cargo lay and promised the helmsman “ten-fold freight money,” if he would anchor in some secluded place, behind a promontory, etc., where the vessel could be overpowered. (Philostratus, vita Apoll. Tyan. III. 24). The conclusion of the story (the ladder hung outside of the ship so that it touches the water) is taken from Plutarch (Pompeius, 24).

In “Lycon with the Big Hand” the artist Aristeides and what is said of his paintings are historical. The same is true of the traits of character cited about the tyrant Alexander of Pherae. Under the description of the earthquake is given an account of what is called in seismology a tidal wave. A side-piece to this may be found in Thucydides (III. 89) where—after a remark about the frequency of earthquakes during the sixth year of the Peloponnesian War—it is stated: “Among these earthquakes the one at Orobiæ in Eubœa displayed a remarkable phenomenon. The sea receded from the shore; then suddenly returned with a tremendous wave and flooded part of the coast, so that what was formerly land became a portion of the sea. Many people perished.”

In these five stories the scene is laid in Athens, on the Ægean Sea, and in Thessaly—but, wherever it is, I have always endeavored to give the characters life and movement, and make them children of the times and of the Hellenic soil. I have also sought to delve deeper into the life of ancient times than usually happens inviii novels. Many peculiarities, like the purification after a murder in the first tale, the Baetylus oracle in “The Hetaeria,” and the use of the great weapon of naval warfare, the dolphin, in “Too Happy” have scarcely been previously described in any form in our literature. The belief in marvellous stones animated by spirits was widely diffused in ancient times, as such stones, under the name of abadir, were known in Phoenicia. The description of the Baetylus oracle is founded upon Pliny (17, 9, 51), Photius (p. 1047) and Pausanias (X. 24). It is evident enough that the stone-spirit’s answer was given by the ventriloquist’s art. Though the ancients had several names for ventriloquists, such as engastrimythae, sternomanteis, etc., the art was certainly little known in daily life, it seems to have been kept secret and used for the answers of oracles, etc. The soothsayer and ventriloquist Eurycles, mentioned by Aristophanes, endeavored to make the people believe that a spirit spoke from his mouth because he uttered words without moving his lips. For the dolphin, the weapon used in naval warfare, see Scholia graeca in Aristoph. (equit 762) and Thucydides (VII. 41).

In the ancient dialogue I have always endeavored to give the replies an individual coloring, and it will be found that Acestor speaks a different language from Sthenelus, Philopator from Polycles, etc. Phrases like: “Begone to the vultures,” “show the hollows under the soles of the feet,” “casting fire into the bosom,” etc., may easily be recognized as borrowed from theix classic writers. To enter into the subject more minutely would be carrying the matter too far. Single characteristic expressions, such as palpale legein, etc. cannot be reproduced.

In introducing the reader to so distant and alien a world, it has been a matter of great importance to me to win his confidence; with this purpose I have sought by quotations to show the authority for what I have written. Here and there, to remove any doubt of the existence of an object in ancient times, I have added the Greek names. For the rest I have everywhere striven to follow the old maxim artis est celare artem.

Copenhagen, November 1, 1881.

P. Mariager.

| PAGE | |

| ZEUS HYPSISTOS, | 1 |

| THE SYCOPHANT, | 69 |

| THE HETAERIA, | 95 |

| TOO HAPPY, | 203 |

| LYCON WITH THE BIG HAND, | 225 |

| PAGE | |

| Gold-fillet (Dr. Schliemann. Hissarlik, Troy.) | 1 |

| Dragon figure on a gold plate (Dr. Schliemann, Mycenæ.) | 65 |

| The market of Athens at a later period, about 200 B. C. (In the upper part, in the background, is the Acropolis with the Parthenon, the colossal statue of Athene, and the Propylæa. To the left of the centre is a part of King Attalus’ hall, afterwards the Stoa Poecile, the circular Tholus, and behind, the Bouleuterium. In the foreground is a statue of Eirene, Peace, with the child Plutus in her arms; in the centre of the steps the square orator’s stage with hermae at the corners.) | 69 |

| Antique vase design, | 92 |

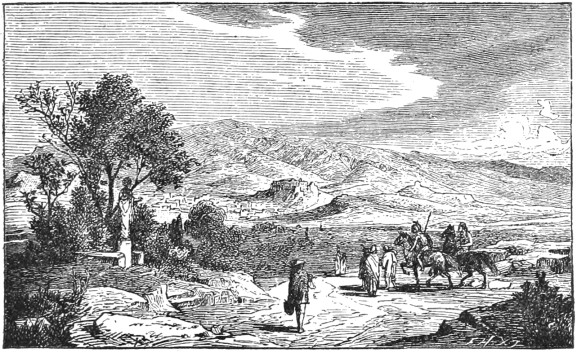

| Athens seen from the road to Eleusis. (In the centre of the picture the Acropolis, with the lower town in front, in the background Mt. Hymettus.) | 95 |

| Antique vase design, | 199 |

| The Ægean Sea. (A large ploion, merchant ship, followed by a pirate craft. Two of the Cyclades in the background.) | 203 |

| Renaissance design, | 222 |

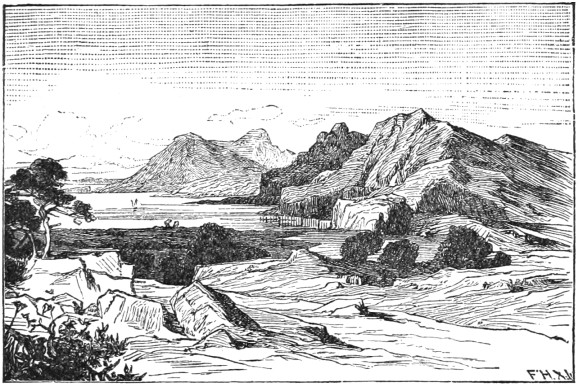

| Coast scene in Thessaly, (near Pass of Thermopylæ,) | 225 |

| Ancient jugglers. (The figure at the right is performing a “sword dance.”) | 318 |

1

The region was one of the most noteworthy in Attica. Manifold in variety were the objects crowded together within a narrow space. By the side of riven masses of rock appeared the smooth slopes of a mountain plateau, and—the centre of the landscape—a huge crag with a flat top and steep sides towered aloft like a gigantic stone altar, reared by the earth itself to receive the homage and reverence of mankind. Two rivers, a wide and a narrow stream, flowed down its sides. Height and valley, ravine and mountain peak, closely adjoined each other, all easy of access and affording a surprising wealth of beautiful views.

The spot had a lofty destination. Here temples and pillared halls, hermae and statues were to appear2 like the marble embodiment of a dream of beauty in the youth of the human race; from hence the light of intellect was to diffuse its rays over the whole inhabited world.

But in the distant ages of which we are now speaking Athens had no existence even in name. Yet a suburb of the city afterwards so renowned was already in course of construction. On the Pnyx, the Areopagus, and part of the Museium stood a number of dwellings, and even at the present day traces may be found on these heights of eight or nine hundred houses, which must have lodged three or four thousand persons.

This city, founded by inhabitants of the island of Salamis, was called Kranaai, and its residents were known by the name of Cranai, dwellers on the heights.

Nothing could be more simple than these houses. As may still be seen, they consisted merely of a room hollowed in the cliff, closed in front and above with clay and stones,—the latter seem to have rested upon logs to prevent a sudden fall during the earthquakes so frequent in this region. Here and there small holes, into which the ends of the pieces of timber were thrust, may still be discerned in the cliffs. Many of the dwellings were arranged in rows, rising like stairs one above another, all with an open space in front to serve as a place of meeting for the inhabitants. These terraces were connected by small steps hewn in the rock; here and there appeared altars, large storehouses, and tombs, the latter consisting of one or more subterranean rock chambers. Great numbers of such sepulchres are still3 found scattered over large tracts of the ancient cliff-city.

Other remains of masonry may be seen in the holes in the earth made to collect rain-water. More than twenty of these ancient wells can be counted in this region, for though the Attic country was richly dowered in many respects, it lacked water, and it was not without cause that Solon’s law afterwards prohibited any one from borrowing of a neighbor more than a certain quantity. The inhabitants of Kranaai had located their wells so skilfully that even now—after the lapse of more than thirty centuries—many of them collect and keep the rain.

Below the cliff-city itself the direction of the streets may still be discerned, especially in the deep gully leading down to the Ilissus. Here there are distinct traces of wheels, between which the stone was roughened to give the draught-animals a better foothold, and along the sides of the road ran smooth-hewn gutters to carry off the rain-water pouring down from both bluffs.

Many generations had already succeeded each other in the cliff-city, when a new race settled on the little plateau between the Hill of the Nymphs and the Gulf of Barathron. Like their predecessors, the new-comers originated in Salamis, but they called themselves4 Cychreans, from a family descended from Cychreus, one of the demi-gods of the island.

While on the Pnyx alone was found the altar of Zeus Hypsistos, the supreme Zeus, around which gathered the native inhabitants and the Cranai to worship a common god, the new-comers erected a sanctuary to the sea-nymph Melite, Hercules’ love, who was related to the Æacidae, natives of Salamis.

The two neighboring colonies thus each worshipped its own divinity and lived in peace and friendship, nay at last some of the Cychreans took wives among the daughters of the Cranai.

On the other hand the new-comers were by no means on good terms with the natives; for, as the latter lived scattered over the country and did not seem to be very numerous, the Cychreans had forced those they met to work for them. They had already employed them to smooth the cliff, to enable them to build there, and many of the Pelasgians had been seriously injured by the toilsome labor. Nay, Tydeus, a tall, handsome youth, brother of one of their chiefs, had suffered a terrible death, having been stoned because he had defended himself and refused to work for the foreigners.

The Cychreans endeavored to conceal their crime, fearing that when the matter reached the Pelasgians’ ears they would make war upon them. There was very grave cause for alarm; for the Cychreans had often seen from their cliff Pelasgian scouts hiding behind the clumps of broom on the plains, evidently watching for an opportunity to approach their enslaved5 countrymen. Young, swift-footed youths, whom it was lost time to pursue, had invariably been chosen for this service, so the Cychreans lay in ambush, captured some of the lads and questioned them narrowly then, as they pretended to know nothing, forced them to work like the others.

The morning after the capture of these spies the Cychreans noticed that, far out on the plain, a pile of wood had been lighted, on which ferns and green plants were undoubtedly thrown; for it sent forth a dense, blackish-brown smoke, which rose to a considerable height and could be seen far and near. Later in the day another bale-fire was discovered farther off, and before noon ten columns of smoke were counted from the cliff, five on each side, the last of which were almost lost to sight in the distance. There was something strangely menacing in these murky clouds which, calling to and answering each other, rose like a mute accusation towards the sky.

The whole Cychrean nation, young and old, bond and free, gathered outside of their houses and stared at the unknown sign. They suspected that it was a signal for the Pelasgians to assemble, but when they spoke of it to the new bondmen the latter said they had never seen such a smoke, but that the Cychreans might rely upon it that the Pelasgians would not march against them until the arrival of a more propitious day. When the new settlers asked when that would be, they answered:

“When the moon is large in the sky.”

6 The Cychreans were obliged to be content with this, but each man in secret carefully examined his weapons; no one believed himself safe.

Lyrcus, son of Xanthios, was one of the principal Cychrean chiefs. He was feared for his strength and, in those days, fear was synonymous with respect. Lyrcus had devoted himself to the trade of war; he understood how to forge and handle weapons and taught the youths their use. In personal appearance he was a tall man with curling black locks, a reddish-brown beard, and a keen, but by no means ugly face. He usually went clad in a tight-fitting garment made of wolf-skins, that left his muscular legs and arms bare, and wore around his waist a leather girdle in which was thrust a bronze knife a finger long. Many tales about him were in circulation among the Pelasgians; for being a warlike man he had often quarrelled with them and on predatory excursions with some of his comrades had plundered their lands, carrying off goats, barley, figs, honey, and whatever else pleased him.

Lyrcus was no longer very young. He had seen the green leaves unfold and the swallows return some forty times. Nevertheless, he had always scoffed at love and considered it foolish trifling. When he was not forging, his mind was absorbed in the chase and in practising the use of arms.

7 Yet, though Lyrcus was so fierce a warrior, Aphrodite had touched his heart and shown that she, as well as Artemis, deserved the name of Hekaërge, the far-shooting. Once, during a short visit to the neighboring settlement, Lyrcus had seen Byssa, the fairest maiden in the cliff-city, drawing water from the well in front of her house, and had instantly been seized with an ardent passion for her. Grasping her firmly by the arm, he gazed intently at her and, when the blushing maiden asked why he held her so roughly, he replied: “Never to let you go!” Such was the fierce Lyrcus’ wooing.

Byssa’s father, Ariston, the priest of Zeus Hypsistos, was an aged, gentle-natured man who dared not refuse the turbulent warrior; yet he only gave his consent on condition that Byssa should keep the faith of her ancestors and not offer sacrifices to Melite in the Cychreans’ sanctuary. Nevertheless, both he and his wife had tears in their eyes when Lyrcus bore their only child away and, in taking leave of Byssa, Ariston laid his hands upon her head, saying:

“Be a good wife to this stranger. But do not abandon Zeus Hypsistos, that Zeus Hypsistos may not abandon you.”

Since that day a whole winter had passed, and Lyrcus seemed to love Byssa more and more tenderly. There was only one subject on which the husband and wife held different opinions. When Lyrcus saw the other women flocking to Melite’s sanctuary he often wished that Byssa should accompany them. But8 Byssa was inflexible. “Remember your promise to my father,” she said. “Whatever may befall me, I shall never forget his counsel: ‘Do not abandon Zeus Hypsistos, that Zeus Hypsistos may not abandon you.’” And so the matter rested. But when a Phoenician ship came to the coast—for in those days the Phoenicians were the only people who dared to sail across the sea—Lyrcus bought the finest stuffs, ornaments, and veils. It seemed as though he could not adorn Byssa enough, she was to be more richly attired than any of the Cychrean women.

Byssa had already had one suitor before her marriage, one of the Pelasgian chiefs, a man thirty-eight years old, named Periphas. He was the owner of a large herd of goats, often offered sacrifices to Zeus, smoothed many a quarrel, and had the reputation of being a good and upright man. Yet there was little reason that he should be renowned for piety and sanctity, for he could scarcely control his passions and had so violent a temper that he had once killed a soothsayer because the latter, in the presence of the people, had predicted that he would die a shameful death.

While offering a sacrifice in the cliff-city Periphas had seen pretty Byssa and instantly asked her of her father, promising rich bridal gifts. But the priest Ariston had answered that the maiden was still too young.

After that time Periphas was often met in the vicinity of the Cranai’s cliff and, when sacrifices were offered on the ancient altar, always appeared at the head of the Pelasgians. But from the hour Lyrcus9 had carried Byssa home none of the Cranai had seen him, though it was said that on one of Lyrcus’ pillaging excursions he had shouted:

“Beware, when the day of retribution comes, I shall not content myself with carrying off goats.”

Such was the state of affairs at the beginning of our tale. It almost seemed as if the capture of the spies was to give occasion for war; one of the youths had succeeded in escaping and the Cychreans feared that during his stay among them he might have obtained news of Tydeus’ death. This Tydeus, who had been so shamefully stoned, was Periphas’ brother, and the chief thus had double cause for vengeance—his brother’s murder and his slighted love.

But spite of the danger, under these circumstances, of leaving the Cychreans’ cliff Lyrcus had too restless a nature to remain quietly at home. The very day that the columns of smoke had struck such terror into the people he had set out early in the morning, accompanied by six or eight men, to hunt on the plains or among the woods that clothed Mt. Parnes.

The day had been one of scorching heat. The sun had still one-sixth of its course to run, and the air quivered over the heated cliffs.

The Cychreans had sought refuge outside of their small, close dwellings to get a breath of the north10 wind. On each terrace, men, women, and children were moving about, the former often clad merely with the skin of some animal thrown around the hips, the boys perfectly nude, and the women in looped, sleeveless garments or sometimes with only a short petticoat over the loins. Most of these robes were white, and the others were made of red, yellow, or blue stuffs; at that time people valued only bright pure colors. Everywhere merry conversation was heard, and these hundreds of half-nude figures formed an indescribably animated picture against the dark background of rock. Fear of the Pelasgians seemed to have vanished even before the fires were extinguished, at any rate it did not prevent the Cychreans from enjoying the present moment.

On one of the lowest terraces, directly opposite to the Areopagus, stood Lyrcus’ house and beside it the shed where he forged his weapons. At the door he had chained a large yellow dog of the Molossian breed, a sort of bull-dog, and in the shelter of the dwelling an old female slave was busy at a fire, over which she had hung a soot-encrusted clay vessel.

A few paces off, towards the edge of the cliff, a canopy of rushes was stretched between long poles. Beneath its shadow stood Byssa busied in weaving loose bits of woollen stuff into a single piece. The “chain” was placed perpendicularly, so that the weaving was done standing;—the horizontal loom, which had been used in Egypt for centuries, was not yet known in Hellas.

11 As Byssa stood near the verge of the cliff, with the blue sky behind her, there was an excellent opportunity to observe her. She had fastened her dark hair in a knot through which a bronze pin was thrust, and wore around her neck a row of blue glass beads. The rest of her dress consisted merely of a red petticoat, reaching from her hips to her knees. But her low brow, her calm black eyes, brilliant complexion, and full bust displayed the voluptuous beauty peculiar to the South, and which, even in early youth, suggests the future mother. In short, she was a true descendant of the grand Hellenic women, who from the dim mists of distant ages appear in the bewitching lore of tradition, fair enough to lure the gods themselves and strong enough to bear their ardent embrace and become the mothers of demi-gods and heroes.

It was a pleasure to see how nimbly she used her hands, and how swiftly the weaving progressed. Each movement of the young wife’s vigorous, rounded, slightly-sun-burned body, though lacking in grace, possessed a peculiar witchery on which no man’s eye would have rested with impunity.

But all men seemed banished from her presence. Every one knew that Lyrcus’ jealousy was easily inflamed, and however great the charm Byssa exercised, fear of the fierce warrior was more potent still.

Byssa’s thoughts did not seem to be absorbed in her work. Each moment she glanced up from her weaving.

The Attic plain lay outspread before her in the sunlight. Here were no waving grain-fields, no luxuriant12 vineyards; the layer of soil that covered the rocks was so thin that the scanty crop of grass could only feed a few goats. Here and there appeared a few gnarled olive-trees, whose green-grey foliage glistened with a silvery lustre, and wherever there was a patch of moisture the earth was covered with a speckled carpet of crocus, hyacinth, and narcissus blossoms.

Finding the plain always empty and desolate, the young wife at last let her hands fall and, sighing deeply, turned towards the slave.

“How long he stays!” she exclaimed, breaking the silence.

“Lyrcus is strong and well armed,” replied the slave as she heaped more wood on the fire. “The Pelasgians fear him worse than death. He will return unhurt.”

Byssa worked on silently; but she was not at ease and looked up from her weaving still more frequently than before.

“Why,” cried the slave suddenly, “there they are. Look at Bremon.”B The bull-dog had risen on its hind legs and was leaning forward so that the chain was stretched tight; snuffing the wind and growling impatiently it wagged its tail with all its might.

B Growler.

Byssa stepped farther from under the rush canopy and shaded her eyes with her hands. On the right the13 view was closed by Mt. Lycabettus, whose twin peaks looked almost like one; on the left the gaze rested on dark Parnes, whose strangely-formed side-spur, Harma, the chariot, was distinctly visible from the Cychreans’ cliff.

For a long time Byssa saw nothing, then she accidentally noticed, much nearer than she had expected, a white spot among some trees.

“There he is! There he is!” she cried joyously, clapping her hands. “Tratta, rejoice! I see a light spot out there—his white horse.”

In a mountainous country like Attica even the plains are uneven, and a rise of the ground concealed her view of the approaching steed.

At last the light spot appeared again—this time considerably nearer. Then several moments passed, during which it seemed to grow larger.

Byssa strained her sight to the utmost, her bosom heaving with anxious suspense. Suddenly she turned very pale and throwing herself upon Tratta’s breast, faltered in a low voice:

“Something terrible has happened. The horse is alone—riderless.”

Almost at the same instant she released herself from the slave’s embrace and went to the very verge of the cliff. From thence, at a long distance behind the horse, she descried a group of people slowly advancing. Several men who looked like black specks seemed to be carrying another, and several more followed.

At this sight Byssa uttered a loud shriek and14 clenched both hands in her hair. But Tratta held her back.

“Be calm, child,” she said with all the authority of age. “First learn what has happened. You can find plenty of time to mourn.”

But Byssa did not heed her. The horse had come very near and was galloping swiftly to its stable at the foot of the cliff.

Ere Tratta could prevent it, Byssa hurried to the nearest flight of stairs and darted madly down the rough-hewn steps, where the slightest stumble would cause mutilation or death. The slave, not without an anxious shake of the head, slowly followed.

The horse had scarcely allowed itself to be caught when Byssa, with tears in her eyes and a peculiar solemnity of manner, turned to the old servant and pointed to the animal’s heaving flank.

There was not the slightest wound to be seen; but a streak of blood a finger broad had flowed down the steed’s white side and matted its hair together.

“I knew it, Tratta, I knew it!” cried Byssa despairingly.

Then, in a lower tone, she added: “It is his blood.”

But Tratta answered almost angrily:

“His or some other person’s; what do you know about it? Help me to get the horse into the shed.”

Byssa, without knowing what she was doing, obeyed and then looked out over the plain, where she beheld a sight that made her tremble from head to foot.

15 Lyrcus was approaching uninjured at the head of his men.

Byssa uttered a shriek of joy that echoed from cliff to cliff as, with outstretched arms and fluttering hair, she flew to meet her husband.

Lyrcus knit his brows.

“What is it? What do you want here?” he asked, surprised to find her at the base of the cliff.

But Byssa heeded neither words nor look. Throwing her arms around his neck she clung to him and covered his wolf-skin robe with tears and kisses.

“Lyrcus, you are alive,” she repeated frantically, while all the fear and suspense she had endured found vent in soothing sobs.

“Byssa, speak! What is it?” asked Lyrcus, amazed at the excitement in which he found his wife.

Byssa took him by the hand, led him to the stable, and put her finger on the red streak upon the horse’s side.

“Simpleton!” said Lyrcus laughing. “That is no human blood.” And he pointed to a huge dead wild-boar, which two men could scarcely carry on a lance flung over their shoulders. “After the hunt,” he continued, “we wanted to put the great heavy beast on the horse; but it was frightened, bolted, and ran home.”

Meantime the men had come up. In spite of their fear of Lyrcus they could not refrain from looking at pretty Byssa, who was now doubly beautiful in her agitation and delight. Nay, some were not content with16 gazing at her face, but cast side-glances at her bare feet and ankles, which were sufficiently well-formed to attract attention, though it was customary for women to go about with looped garments.

Lyrcus noticed these stolen glances, and frowning gripped his lance more firmly.

“Why do you wear that red rag?” he said harshly, pointing to Byssa’s short petticoat. “Haven’t I given you long robes?”

“The sun is so hot—and I was alone at my weaving,” stammered the poor young wife with a burning blush.

As she spoke, confused and abashed, she put her foot on the lowest step of the rock-stairs and was going to hurry up the cliff. But Lyrcus seized her and hurling her behind him so that he concealed her with his own body, shouted sternly to his companions:

“Forward!”

Then he himself went up after them, watching rigidly to see that no one looked back, but left Byssa and the slave to follow as best they could.

On the cliff above there was great joy among the Cychreans over the splendid game. But when the animal was flayed and its flesh cut into pieces all, not merely the hunters themselves but their friends and relatives, wanted a share of the prize. From words17 they came to blows, and Lyrcus needed all his authority to restrain the infuriated men.

Meantime the sun had set behind the mountains of Corydallus. The olive-trees on the plain cast no shadows, the whole of the level ground was veiled in darkness. Everything was silent and peaceful, ever and anon a low twittering rose from the thickets.

The Cychreans lingered gossipping together after the labor of the day. Some of them asked Lyrcus and his companions whether anything had happened during the hunt. Lyrcus replied that small parties of Pelasgians had been seen passing in the distance, but he seemed to attach no importance to the matter, and many of the Cychreans were preparing to go to rest—when a child’s clear voice cried in amazement:

“Look, look! The hills are moving!”

Every eye followed the direction of the child’s finger.

Far away over some low hills, whose crests stood forth in clear relief against the evening sky, a strange rippling motion was going on. It looked as though some liquid body was flowing down, for one dark rank succeeded another, as wave follows wave.

There was something in the sight which turned the blood in the Cychreans’ veins to ice. Nothing was visible on the plain itself; everything there was shrouded in the dusk of evening.

All listened in breathless suspense. Then a rushing sound echoed through the increasing darkness—a noise like a great body of men in motion, the hum of18 many voices, distant shouts, songs, and the clash of weapons. The din seemed to increase and draw nearer. Then flames glimmered, as though instantly covered by dark figures. It was like a living stream, that grew and widened till it surrounded the whole cliff.

Then a torch was lighted and a small party of ten or twelve men approached within a bow-shot. Two of them put long horns of spiral form to their mouths, and wild echoing notes resounded from cliff to cliff. A man clad in a white linen robe stepped forward, raising aloft a laurel staff. Deep silence followed, and his shrill voice was now heard, saying:

“Cychreans! Ye have greatly wronged us. Ye have built houses on land that was not yours; ye have made the men of our nation serve you and, when the youth Tydeus refused, ye basely murdered him.

“For the surrender of the land and in token of subjection ye must pay us, the original inhabitants of the country, an annual tribute of seven hundred spears and as many swords and shields.”

Here a loud clamor arose among the Cychreans. They understood that it was the Pelasgians’ intention to disarm them, and their wrath found vent in fierce invectives.

“Listen to the dogs!” they shouted. “Ere the battle has begun, they talk like conquerors. Do the bragging fools suppose they can blow the cliff over with their snail horns?”

But the herald did not allow himself to be interrupted.

19 “Cychreans!” he continued, “the Pelasgians whom ye have enslaved must be set free and, in compensation for your crime of murder, we demand that you deliver up to us Lyrcus, who has provoked war and pillaged peaceful dwellers in the land. These demands we will enforce by arms. We no longer come with entreaties, but with commands.”

Again a terrible din arose, but Lyrcus ordered silence and springing upon a rock, from which he could be seen and heard far and near, shouted:

“Pelasgians! The land where we have built was desolate and uninhabited; it belonged to us as much as to you. When you demand slaves and wish me to be delivered over to you, the answer is: Come and take us. But mark this: it is you, not we, who begin the war; we only defend ourselves against assault. This answer is deserved, and approved by our people.”

Loud exulting shouts from the Cychreans hailed his words.

Lyrcus gazed confidently around him; for, reckless as he was of his own safety, he was cautious where the people’s welfare was concerned. At the first sign of war he had put the cliff in a posture of defence.

At all the wider approaches he had piled heaps of huge stones to be rolled down on the foe, and where men could climb up singly he had stationed sentinels. The rear of the height was inaccessible; here stretched for more than four hundred ells the Golf of Barathron, bordered along its almost perpendicular sides by cliffs from ninety to a hundred yards high. This dark, wild20 chasm was afterwards used for a place of execution; and it was here that malefactors whom the law sentenced “to be hurled into the abyss” ended their days. Towards the north, the windward side, the cliff had no covering of earth and here at its foot, half concealed among some huge boulders, was the entrance to a cave which led obliquely upward to some subterranean tombs, whence a steep passage extended to one of the lower terraces. In this passage Lyrcus had had steps hewn in order to secure a secret descent to the plain, and for farther concealment he had ordered bushes to be planted outside of the cave.

Though the Cychreans on the whole were in good spirits, they found themselves in a serious mood as the decisive hour approached. Lyrcus, at his first leisure moment, had assured Byssa that the Pelasgians would be received in such a way that not a single man could set foot on the open space before the houses. The young wife silently embraced him; her eyes were full of tears and she could not speak. She trusted her husband implicitly, but nevertheless was deeply moved.

“Before the sun goes down,” she thought, “many an eye will be closed. And what will be Lyrcus’ fate?”

The greater portion of the night passed quietly. They saw the Pelasgians light fires in a semi-circle21 around the cliff and noticed the smell of roasted meat. Songs and laughter were heard, and with the fires a thicket of spears seemed to have grown out of the earth.

On the cliff itself deep silence reigned. Yet a strange crackling sound echoed upon the night, and the wind brought a light mist and a smell of burning. Soon after a red cloud rose into the air and from lip to lip ran the shout:

“The store-house is on fire!”

Was it some foolhardy Pelasgian or one of the new-made bondmen who had set it in flames? In any case the task had been no easy one. The store-house, like the dwellings, had been hewn out of the cliff and contained nothing combustible except seeds and the timbers on which the roof rested. Nevertheless, the flames spread swiftly, when the fire first reached the air, and a part of the roof fell. Vast lurid clouds of smoke whirled aloft and, as usual when seeds are burning, numberless showers of sparks rose with the smoke and fell back again to the earth in a fine rain. Suddenly, just as the fallen timbers burst into a blaze, a lofty column of fire shot up from the roof. The Hill of the Nymphs, the Areopagus, and the height known in later times as the Acropolis were illumined by a crimson glow, and the whole Pelasgian army broke into exulting shouts.

Some of the boldest came nearer, and an old bow-legged simpleton, ridiculously equipped with a gigantic helmet and an enormous club, strode toward the cliff,22 where he made a movement as though he was setting his foot on the neck of a conquered foe.

At this defiance a young Cychrean seized his bow and arrow.

“Rhai—bo—ske—lēs! Bow-legs!” he shouted, his voice echoing far over the plain, “where did you get your shield?”

The bow-string twanged—and the old man just as he took flight fell backward to the ground.

The Cychreans clapped their hands and uttered loud shouts of joy.

At the sight of the old man’s fall—he was probably a chief—a bloodthirsty yell ran through the ranks of the Pelasgians. A long word, rendered unintelligible by the distance, flew from mouth to mouth till it suddenly rang out clearly and distinctly like a command.

“Sphendonētai! Slingers!”

Forth from the dark throng gathered around the fires marched a body of men who had nothing but a sheep-skin around their hips. They formed in two rows facing the cliff, a score of paces intervening between the ranks, and the same distance between man and man.

Among a pastoral race like the Pelasgians the sling was an indispensable implement. It served to keep the herds together; for when a goat or any of the cattle had been hit once or twice by a stone from a sling the shepherd-dog noticed it and kept a strict watch upon the animal. By skill in the use of the sling the herdsman23 thus saved himself the trouble of running after the beasts which strayed away from the flocks, and in a mountainous region like Attica, where one can scarcely walk a few hundred paces without going up or down, it is well to spare the legs.

The sling itself was very simple. It consisted merely of two woollen cords half an ell long and about as thick as the finger, fastened at each corner of a piece of leather shaped like a lance-head, with a hole in the middle to hold the stone firmly. The art of using the implement consisted in letting one cord drop at the moment the stone was in the right curve to reach the mark.

The men with the sheep-skins round their loins collected stones from the ground and hurled them towards the cliff, until they ascertained the distance—then they took them from the pouches they carried suspended by a leather thong over their shoulders. These stones, of which each man carried twelve or fourteen, weighed about eight pounds. Afterwards bullets the size of a hen’s egg were used and these bullets, marked with the Hellenic stamp, are still found on the plain of Marathon.

Suddenly a deafening clatter resounded upon the Cychreans’ cliff from the stones which beat against the houses and fell back on the hard ground. Soon shrieks of pain blended with the din and Lyrcus perceived with alarm that his people were being badly wounded as, under the hail of stones from above, heads were bruised or shoulder-joints injured.

24 The youth who had felled the old chieftain again seized his bow, but Lyrcus dashed it from his hands.

“Luckless wight!” he said, “our bows do not reach half so far as their slings. Do you want to show them it is so?”

After hurriedly stationing sentinels where there was any shelter, he ordered his men to retreat into the houses. But even there they were not safe; for when one or more stones struck a roof whose timbers were not new, it fell wholly or in part, wounding men, women, and children. The cliff soon echoed with wails and shrieks of pain, and the deafening rattle of the shower of stones was gradually weakening the Cychreans’ courage, the more so because they were unable to defend themselves.

Then Lyrcus, who had mounted guard himself, saw a small body of men approaching from the Pelasgian camp, evidently to reconnoitre. They moved along the cliff about a bow-shot off for some time, quietly allowing the stones from the slings to fly over them. Suddenly one who marched at the head of the band raised a large conch horn to his lips, sounding three long, shrill notes, and a great bustle arose among the Pelasgians.

Five or six hundred men gathered in front of the camp and hastily formed in ranks. Leaders were heard firing their zeal and issuing orders. Then they ran at full speed towards the cliff, where the spies, holding their shields over their heads, were already trying25 to show the advancing soldiers the places most easy to ascend.

At the moment the dark figures in their goat-skin garments and hoods set foot on the cliff, the hail of stones ceased. The Cychreans now came out of their houses and went to the heaps of stones piled on the steps. Though the fire of the store-house was beginning to die away, the lurid flames still afforded sufficient light to show the Pelasgians their way. When Lyrcus saw that they had scaled part of the height, he gave orders to hurl the stones down. The Cychreans set to work eagerly; rock after rock rolled down, bounding from one boulder to another. Again loud shrieks of pain arose, but this time from the Pelasgians, many of whom missed their footing, plunged downward, and were mangled by the fall.

Nevertheless, many of them, partly by escaping the stones and partly by protecting themselves with their shields, succeeded in approaching the open terrace of the crag unhurt. Here the Cychreans rushed upon them, but they defended themselves with the obstinacy of men who have a steep cliff behind them. For a long time the battle remained undecided—then the Cychrean women hastened to the aid of the men. They flung ashes and sand into the Pelasgians’ eyes, and some finally used heavy hand-mills for weapons. Nay, lads of twelve and fourteen followed their mothers’ example and armed themselves with everything on which they could lay hands.

When Lyrcus perceived that the battle was raging26 violently he turned towards the burning store-house and, seeing that the fire was nearly out, he laughed and exclaimed: “I’ll risk it.” Then, collecting the men who could be spared, he led them by torchlight through the covered passage to the plain. Here, under cover of the darkness, he stole with his soldiers behind the Pelasgians’ camp and, while the latter were gazing intently towards the cliff to see whether the attack was successful, the Cychreans uttered a loud war cry and unexpectedly assailed them in the rear.

Lyrcus, as usual, wore his wolf-skin robe and a hood of the same fur on which, by way of ornament, he had left the animal’s ears—an appendage that gave his head-gear a peculiarly fierce appearance. By the uncertain light of the fires many of the Pelasgians recognized him by the hood with the wolf’s ears, and soon the cry was heard:

“Lyrcus is upon us! Fly from Lyrcus!” Then began a flight so headlong that many of the soldiers thus taken by surprise did not even give themselves time to pull their spears out of the ground.

Just at that moment a chief in a copper helmet, breast-plate, greaves, and shield, sprang from behind a rock, threw himself like a madman before the fugitives and wounded several with his spear.

“Periphas!” shouted Lyrcus, hurling his lance at him. But the Pelasgian parried it with his shield, and at the same instant its edge was cleft by the weapon he stooped behind the rattling pieces. The ash-spear whizzed over his head, ruffling his hair.

27 “So near death!” he thought, and an icy chill ran through bone and marrow.

Lyrcus drew his sword; but a throng of fugitives pressed between him and Periphas—he saw the latter’s glittering helmet whirled around and swept away by the stream of men.

At the name of Lyrcus the alarm spread from watch-fire to watch-fire. Just at that moment a loud shriek of terror arose from those who had climbed the Cychreans’ cliff, for when the glow of the flames from the burning store-house had died away they were forced in the darkness over the verge of the bluff. This shriek hastened the Pelasgians’ flight; they instantly perceived that they could expect no help from their comrades.

Lyrcus, fearing that the enemy might discover how small his band was, soon checked the pursuit, and when his people on the way home vied with each other in lauding him as conqueror, he replied:

“It was their mistake that they used fire as a torch to scale the cliff; for when the flames died down they were suddenly left in thick darkness with the foe in front and a steep bluff behind.... I, for my part, put my trust in the darkness, under whose cover I surprised the Pelasgians, and the darkness did not deceive me as their flames deluded them.”

28

During the first few days after the unsuccessful attack Periphas, from fear of the Cychreans, concealed himself in a cave in Mt. Hymettus. It was known only by the herdsman who brought him his provisions, and the furniture consisted of some goat-skin coverlids, a hand-mill, a few clay vessels, and a stone hearth.

One sultry afternoon when the sun shone into the cavern Periphas was lying almost naked behind a block of stone at the entrance. Before him stood a youth with curling black hair and a deer-skin thrown around his loins. Nomion was the son of a neighboring chieftain, and had been Tydeus’ friend from boyhood.

Both looked grave, nay troubled; they were talking about the Cychreans and Tydeus’ murder.

“I believe you are mistaken,” said Nomion. “Lyrcus had nothing to do with the matter. Tydeus fell in a broil; his refusal to serve the Cychreans irritated them and made them furious. Each threw a stone and wounded him until the hapless youth drew his last breath. It was like a swarm of bees attacking a mule; no single bee can be said to kill it, each one merely gives its little sting—but the animal dies of them.”

Periphas shook his head.

“I know better,” he answered. “Lyrcus hates me and all my race. Did I not woo Byssa?”

“No, no,” persisted Nomion, who as the son of a29 chief used greater freedom of speech in addressing Periphas than most others would have ventured to do. “If Lyrcus was the murderer, how could he enter the places of assembly before the houses and move about among the other Cychreans? Who will associate with an assassin? Are not trials in all cases of murder, according to ancient custom, held under the open sky that neither accusers nor judges may be beneath the same roof with the slayer?”

“I know,” muttered Periphas with a sullen glance, “that a murderer is unclean.”

“Not merely unclean—but under a double ban. The victim’s and the wrath of the gods. Shall the murdered soul wander away from light and life without demanding a bloody vengeance? And the gods—to whom murder is an abomination—shall they forbear to practise righteous retribution?”

Periphas, averting his face, remained silent.

“Forgive me!” exclaimed Nomion, “I forgot that you yourself....”

“The soothsayer,”—said Periphas, lowering his voice, “yes, he fell before my spear. But he was rightly served. Did not the fool proclaim aloud, in the presence of all, what he ought to have confided to me alone?”

“Yet it was a murder.”

“No, my friend, believe me, it was something very different from their crime. Don’t you know, Nomion, that no Pelasgian owns larger herds than I—well! If I have offended the gods, no one has brought them30 more numerous and costly offerings. Besides, I went directly to Kranaai and caused Ariston to purify me, according to priestly fashion, from the stain of blood. As for the dead man’s family—I appeased them long ago with costly gifts.”

“But—the disposition?” asked Nomion, looking Periphas straight in the eye.

“The disposition!” replied Periphas, shunning Nomion’s glance. “Youth, you utter strange words. When neither gods nor men complain, who asks about the disposition?”

And Periphas burst into a strange, forced laugh, that echoed almost uncannily through the cave.

“Be that as it may,” said Nomion. “If the Cychreans suffer murderers to live among them unpunished, will not they, too, will not the whole nation be unclean and exposed to the wrath of the gods?”

“It seems so.”

“Yet the Cychreans remain victors, while we, Tydeus’ avengers, are scattered like chaff before the wind. What is the cause?”

“Perhaps their gods are stronger than ours.”

“The sea-nymph Melite stronger than Zeus Hypsistos! You cannot believe that.”

“Perhaps we ought to have waited for a lucky day.”

“No,” retorted Nomion, “I believe that Lyrcus conquered because he has done no evil. He is a warlike fellow and foremost in the fray, so he cannot content himself with carrying away goats, barley, figs, and31 honey. But he has never killed a man except in fair fight. Had he been present, Tydeus would never have been stoned.”

“You have a remarkably good opinion of Lyrcus,” said Periphas. “But why talk about this Cychrean continually? There are other chiefs in the country.... Well! We’ll see whether the gods will protect him another time.”

“Periphas! What are you planning?”

“Do you know the pretty bird whose name is Kitta? It loves its mate so dearly that it cannot live without it. Let the hen be caught in the nest by some simple snare, and the cock will fly after her of its own accord and allow itself to be captured.”

“In the name of the gods! Do I understand you? Do you mean to steal Byssa?”

“Doesn’t she seem to you worth having? Well, by Zeus,” continued Periphas, the blood mounting into his cheeks, “I would rather carry her away than goats, barley, figs, and honey.”

“Beware, Periphas! Don’t drive Lyrcus to frenzy. He will then be capable of anything.”

“Not when he is in my power.”

At the foot of the heights of Agrae, a part of Mt. Hymettus, the channel of the Ilissus widens. The river here divides into two arms, which enclose a level32 island. At the place where the branches meet the banks form a bluff with two pits; here, trickling between the layers of stone, excellent drinking water collects in such abundance as to form a pond. It is the fountain of Callirhoë (beautiful spring) and is used at the present day as a pool for washing.

At the time of this story Callirhoë was the place from which the wives and daughters of the Cychreans, as well as the Cranai, brought water when the little wells on the cliffs were exhausted. The fountain of Clepsydra was considerably nearer; but as the name (water that steals forth) implies, it was too scanty to supply two colonies. Therefore the people were obliged to fetch water from the banks of the Ilissus, more than two thousand feet off, in a desolate tract of country called Agrae. The journey was not wholly free from peril, for the Pelasgians roving over Mt. Hymettus considered the pool their own and looked askance at all others who sought to use it. Women had often been molested there and several times even abducted. Therefore it had become the custom for the women and girls to go to the fountain in parties, and to be accompanied by armed men. But several years had now elapsed since any one had been molested, and the guard of men was beginning to be rather careless. Instead of weapons, many of the younger ones took the implements of the chase and amused themselves by snaring hares, great numbers of which were found in this region.

The trip to the fountain on the whole was a pleasure33 excursion. With the faculty for making life easy and pleasant possessed by all southern nations, the time was well-chosen. In the first place the party started in the afternoon; the sun was then behind them and when they returned it was hidden below Mt. Corydallus. One of the older men took a syrinx or a flute; the young fellows jested with the pretty maids and matrons, they relieved each other in carrying the water-jars, laughter and song resounded, sometimes they even danced in long lines on the open ground beside the pool.

A few days after the conversation between Periphas and Nomion in the cave on Mt. Hymettus one of these expeditions was made. After the recent victory there was two-fold mirth, and the party could be heard for a long distance amid the rural stillness of the country bordering the Ilissus. At the first sound of the notes of the flute and the merry voices something stirred in the bushes on the crag just below the fountain of Callirhoë. Two sunburnt hands pushed the branches aside and a brown visage appeared, of which, however, little could be seen, as a goat-skin hood was drawn low over the brow. Periphas—for it was he—saw from his hiding-place the women approaching between a double row of men.

“There they are!” he said to Nomion, who lay concealed behind him. “What do you say to the plot? First the wife, then the husband. To-morrow morning, perhaps to-night, Lyrcus will be in our power. Will you help me?”

34 “No, by Zeus, no!” replied Nomion firmly. “On the contrary, I will warn you again. Consider, Periphas! Don’t throw the last anchor upon treacherous ground. It ill-beseems the younger man to advise the older—may Zeus open your eyes while there is yet time.”

“Begone to the vultures, foolish boy!” cried Periphas angrily. “You use sword and lance like a man. But where is your courage?”

“By the gods, it isn’t courage I lack,” replied Nomion, as he let himself slide down the precipice and vanished among the hills.

Meantime the party had come nearer. Suddenly there was a movement in the last rank and the joyous shout: “A hare! A hare!” Without losing a moment the youths divided into two bands who, with long poles in their hands, tried to drive the animal towards some snares set at the end of the valley. The older ones convinced themselves that no Pelasgians were in sight, and then slowly followed to witness the result of the chase.

Had Lyrcus been present, this would not have happened; but he had remained at home to forge some weapons.

The women, who were left to themselves by the men’s zeal for the chase, went to the pool and set down35 their water-jars. The barren, dreary region, where usually nothing was seen except a few goats and shepherds, now swarmed with young Cychrean women in white and variegated robes. Most of them stood talking together by the pond—some, weary and breathless, stretched themselves on the mossy bank of the river; others wiped the dust from their limbs with dry leaves; many gathered flowers in the shade, others waded out into the stream to cool their feet in the shallow, but clear and inviting water.

Periphas, from his hiding-place, saw them all, yet among the whole party his eye sought only one.

Byssa was sitting near the pool among some young matrons of her own age. She had removed her sandals, and while he was watching her, rested her foot on her knee to examine a scratch she had received from the stones on the way. A young woman, whose appearance indicated that she was about to become a mother, approached with her arms full of flowers and, smiling, flung them all into Byssa’s lap, whispering something in her ear as if it were to be kept a secret from the very stones. Byssa flushed crimson and snatched up one of the sandals lying by her side to make a feint of punishing her friend; but, as she raised her arm, the sandal slipped from her hand and flew far out in the water.

There was a general outburst of screams and laughter.

Byssa started up, shaking all the flowers from her lap on the ground, hastily gathered up the folds of her36 garments, and waded out into the stream. But the current had already swept the sandal into somewhat deeper water, so that, to avoid being wet, she was obliged to lift her clothes above her knees. She soon perceived that the task was not so easy. Every time she stretched out her hand she was baffled. The little whirlpools in the stream played sportively with their prize; each moment they bore the sandal under their light foam, and when it again appeared it was in an entirely different place from where its owner expected.

A cold wind was blowing and Byssa, like many of her companions, wore a goat-skin bodice. As she had become heated by the long walk she allowed it to hang loosely about her, and every time the pretty Cychrean bent forward to grasp the sandal, Periphas’ gaze could take a dangerous liberty.

Of all the materials that can be used for clothing, nothing displays better than fur the smoothness and fairness of a woman’s form. At the sight of the beautiful shoulders and still more exquisite bosom rising from the rough, blackish-brown skin Periphas’ eyes dilated, and when Byssa’s movements, ere she succeeded in seizing the sandal, revealed more and more of her nude charms, the half-savage Pelasgian’s passionate heart kindled.

He cast a hurried glance towards the spot where the men had vanished and, as he neither saw nor heard anything, he took a large green leaf between his lips to hide the lower part of his face, drew his hood down to37 his eyes, burst suddenly out of the bushes and leaped from the shore into the stream.

The women, shrieking with terror, instantly sprang to their feet.

But Periphas paid no heed. Seizing Byssa, who was paralyzed by surprise, in his arms, he bore her, spite of her struggles, to the shore. Like all well-developed women she was no light burden and, notwithstanding the Pelasgian’s strength, he felt that it would be impossible for him to carry her up the steep bank and therefore put her down, though without releasing his hold on her arm. But Byssa no sooner felt the solid earth under her feet than her senses returned.

“Help! Help!” she screamed. “Shall we fear this one man? Are we not strong enough to capture him?”

And, following words by action, she boldly grasped the Pelasgian’s belt with her left hand, which was free.

“Quick! quick!” she added. “Only hold him a moment—the men will return directly.”

Byssa’s courage produced its effect. The women hurried towards her from all sides; yet the nearest gave themselves considerably more time than those who were farther away.

Periphas perceived that his position was very critical. Without releasing Byssa’s arm, he drew his sword.

“Beware!” he shouted fiercely, “I’ll hew down on the spot the first one who approaches.”

38 And, as Byssa still did not loosen her grasp from his belt, he muttered between his teeth.

“Follow me, or by Zeus....” He did not finish the sentence, but his sinister glance left no doubt of his meaning.

Byssa trembled, for she thought of the soothsayer of whose death she had heard.

“You are the stronger!” she said, and allowed herself to be led up the bank without resistance.

At the top Periphas turned and shouted:

“Women, the first one who shows herself here I’ll give up to my bondmen.”

But the Pelasgian had nothing more to fear. The sight of the naked sword had banished the women’s courage.

He now carried Byssa among some small hills, where a low, two-wheeled vehicle, drawn by two horses, was waiting under the charge of a slave. “Get in!” said Periphas imperiously, then, to render her more yielding, added: “No harm shall befall you! I only want you to serve me as a hostage.”

“I will obey,” replied Byssa, “but on condition that you don’t lay hands on me again.”

She took her place in the front of the chariot, resting both hands on the top. Periphas grasped the reins, dismissed the slave by a sign, braced his feet firmly against the inner foot-board and, standing behind his enemy’s wife, gave his steeds the rein, swung the whip—and off they rattled over stock and stone.

39

Meantime the men had wandered a considerable distance from the fountain. The youths succeeded in driving the hare into a snare, whose owner thought he had exclusive right to it, while those who had driven it into the trap demanded a share of the prize. When the older people came up their opinions differed and, amid the dispute, they did not notice the screams of the women, especially as they often shrieked in sport when they splashed water upon each other.

Suddenly a very young girl, scarcely beyond childhood, came running towards them, beckoning with agitated gestures while still a long way off. The men suspected that something unusual must have happened and hurried to meet the messenger, though without forgetting the hare. Weeping bitterly, she told them what had occurred.

Her hearers were filled with alarm.

“Byssa carried off!” exclaimed the oldest. “Woe betide us! Woe betide us! Curses on the hare, it is the cause of the whole misfortune.”

The walk home from the fountain was very different from usual.

In those days it was not well to be the bearer of evil tidings. Lyrcus’ outbursts of fury were well known; it was also known how passionately he loved Byssa, and no one felt the courage to tell him what had40 happened. Yet it was necessary that he should hear it.

The party had almost reached the Cychrean cliff, and still no plan had been formed. But an unexpected event ended their indecision.

Lyrcus came to meet the returning band.

He had just finished his task of forging and, after standing in the heat and smoke, it was doubly pleasant to breathe the cool sea-breeze. He had never felt more joyous and light-hearted.

“How silent you are!” he called as he advanced. “Have the women lost their voices? By Pan, that would be the greatest of miracles.”

But when he came nearer, seeing their troubled faces, he himself became grave, and with the speed of lightning his glance sought Byssa.

The men, one by one, slunk behind the women.

“Where is Byssa?” said Lyrcus.

No one answered.

He now put the same question to a very young girl, who chanced to be the same one who had rushed from the fountain to meet the men and brought the ill-omened message.

Startled by the unexpected query, she turned pale and vainly tried to answer; her throat seemed choked.

Lyrcus seized her firmly by the arm.

“Speak, luckless girl, speak!” he said. “What have you to tell?”

The girl strove to collect her thoughts, and in faltering41 words said that a Pelasgian had sprung out of the thicket and carried Byssa away.

Then, falling at Lyrcus’ feet, she clasped her hands over the knife he wore in his belt, shrieking:

“Don’t kill me. I did nothing....”

“Where were the men?” asked Lyrcus sternly.

She was silent.

“Where were the men?” Lyrcus repeated, in a tone which demanded an answer.

The girl clasped his knees imploringly.

“They had gone hunting,” she whispered almost inaudibly.

Several minutes passed ere Lyrcus opened his lips. The men wished the earth would swallow them; but their chief’s thoughts were already far from their negligence.

“Who was the Pelasgian?” he asked with a calmness which, to those who knew him, boded danger.

No one replied.

At last the young wife who had flung the flowers into Byssa’s lap stepped forward, drew the kneeling girl away and, without raising her eyes to Lyrcus, said with a faint blush:

“No one knew the ravisher. He held in his mouth a green leaf which concealed his face. But Byssa was forced to obey him or she would have been killed before our eyes. He drew his sword.... Directly after we heard a chariot roll away.”

“A chief then!” said Lyrcus, and without another word he returned by the same way he had come.

42 Lyrcus was too good a hunter to have any doubt what he should do. Going directly home he unfastened Bremon, led him into the house, and let him snuff Byssa’s clothes, repeating:

“Where is she? Where is Byssa?”

The dog uttered a low whine, put his muzzle to the ground and snuffed several times, wagging his tail constantly as if to show that he knew what was wanted. Lyrcus buckled his sword around his waist, seized a spear and shield, flung a cloak over his arm and led Bremon out.

The dog fairly trembled with impatience, and without once losing the trail guided Lyrcus, who held his chain, directly to the fountain of Callirhoë.

Here he followed the bank of the river a short distance but suddenly, as if at a loss, began to run to and fro in all directions.

Lyrcus released the animal but, as it constantly ran down to the bank and snuffed the water, the chief perceived that Byssa must have waded out into the stream. So he led Bremon along the shore, hoping to find the place where she had come out on the land.

Suddenly the dog stopped, snuffed, and began to wag his tail again. This was the spot where Periphas had put Byssa down after having carried her to the bank. Bremon now led Lyrcus away from the brink among some low hills, but here once more he began to run to and fro irresolutely—doubtless where Byssa had entered the chariot.

Meantime night had closed in.

43 Lyrcus at first thought of getting a torch, but soon perceived the impossibility of following the trail of the chariot by torch-light. There was nothing to be done except to wait for morning.

It was a time of terrible torture.

Byssa in a stranger’s power! At the thought he was seized with a frenzy of rage that almost stifled him. But whither should he turn? Who was the ravisher—Periphas? No, he would not have had courage for such a deed directly after a defeat. Besides, the abductor seemed to have gone in the opposite direction to the road to Periphas’ home.

Lyrcus did not know that the Pelasgian had concealed himself in a cave in Mt. Hymettus.

While Lyrcus allowed himself to be led by Bremon, Periphas was continuing his wild career. At the foot of a distant height of Hymettus he gave the chariot to a slave and ascended the mountain with Byssa, who had remained perfectly silent during the whole ride.

At the entrance of the cave Periphas cast a stolen glance at her. The young wife’s face was clouded and threatening; not only the expression of her features, but her bearing and movements showed that she was filled with burning wrath. She resembled at this moment an incensed swan, darting along with half-44spread wings, every feather ruffled in rage. Periphas perceived that he must try to soothe her.

He led her into a room in the cave where a clay lamp was burning and on a large flat stone stood dishes containing barley bread, fruit, honey, and milk.

“Do not grieve, fair Byssa,” he said. “A man must secure himself against such a foe as Lyrcus....”

“By stealing women?” Byssa contemptuously interrupted. “Is that the custom among the Pelasgians? Lyrcus carried home neither maids nor matrons.”

“Perhaps so,” replied Periphas calmly. “But the Pelasgians have made war upon the Cychreans and were defeated. As one of the chiefs who took up arms, I have everything to fear. So I sought a hostage, and where could I find a better one than the woman who is most dear to Lyrcus?”

“Your tongue is smooth, Periphas! But I do not trust you.”

“What do you fear, Byssa? Hostages are sacred; you are as secure as if you were under a father’s roof.”

“And Lyrcus! Will he have no suspicion? Will he think I have been under a father’s roof?”

“You will tell him so, and he will believe you. The inside of the cave is yours; no one shall molest you. You will be compelled to stay here only a few days, until everything is arranged between the Pelasgians and Cychreans.”

Byssa gazed sullenly into vacancy.

“Beware, Periphas!” she said. “This will surely bring misfortune.”

45 “To you or to me?” asked Periphas.

“That I do not know,” replied Byssa. “But one thing I do know. It will cause bloodshed.”

Periphas shrugged his shoulders.

“Look,” he said, pointing to a bear-skin couch, “you can rest here in safety; you must be weary. May the gods grant you pleasant dreams—in the morning everything will seem brighter.”

With these words he left her, went to the outer part of the cavern, passed through the entrance, and walking several paces away clapped his hands.

There was a rustling sound among the huge piles of mouldering debris above the cavern. A dark figure clad in skins, with a huge staff in his hand, stood outlined against the grey evening sky. It was the herdsman who supplied the cave with provisions.

“Have you done what I ordered?” asked Periphas. “Have you put sentinels on both sides and brought the men?”

“When you sound the horn, Periphas, twenty Pelasgians will hasten to your aid.”

“Do they know Lyrcus, the Cychrean?”

“Not all of them, but some do.”

“Very well. When he comes, the men must hide until he is half-way between them. Then let him be surrounded. I will make the man rich who brings me Lyrcus alive or dead. Tell the warriors so.”

Periphas then entered the cave and lay down on the couch of skins flung behind the boulder projecting at the entrance. It was a still, star-lit evening, yet46 spite of the peace and silence without, a strange restlessness seized upon him. Sometimes he felt a presentiment of impending misfortune, at others he exulted in the thought of having Byssa in his power. Thanks to the green leaf he had held in his mouth when he carried her away, none of the Cychreans had recognized him. But so long as Lyrcus knew not where to turn he would not summon the warriors. He would pursue his quest alone and fall into the ambush. At the thought Periphas rubbed his hands and became absorbed in planning how he should best humiliate his captive.

The night was far advanced ere the Pelasgian leader fell asleep. A strange dream visited him. It seemed as if he were with Byssa—when he felt a hand on his shoulder. The soothsayer whom he had murdered stood before him, pale and rigid, with a dark blood-stain on his white robes. Periphas stretched out his hand to keep him off, touched his own body, felt with horror an icy, corpse-like chill, opened his eyes, and was broad awake.

As he rose he accidentally laid his hand on the boulder at the entrance. It was dank with the night-dew, and he again felt a chill.

“It was only the rock,” he muttered, with inexpressible relief.

The clear dawn brooded over the land like a soft grey gleam. The mountains were wrapped in clouds and vapor and the swallows were twittering. Periphas breathed the fresh morning air and felt strengthened47 and inspirited. His first thought was that in the cave, only a few paces from him, he had the fairest woman in the Cychrean city, the woman whom he had once wooed, and who had been given to another.

Doubtless she, like himself, had at last fallen asleep from weariness. He must go to her, see her.

With a slight shiver, caused by emotion more than by the chill air of the morning, he bound a goat-skin around his loins, buckled a belt about his waist, thrust his knife into it and with bare feet stole noiselessly into the cave.