| Number 34. | SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 1841. | Volume I. |

Though our own good metropolis is confessedly one of the most ancient cities in the empire, yet there are few towns of any importance either in England, Scotland, or Ireland, that have so little appearance of old age; we have indeed a couple of venerable cathedrals, which is more, we believe, than any other city in her Majesty’s dominions, except London, can boast of; and we have a few insignificant remains of monastic edifices, but hid in obscure situations, where they are only known to zealous antiquaries:—with the exception of these, however, we have nothing that has not a modern look, though too often a tattered one; nor is there, we believe, a single house within our Circular Road that has seen two hundred years. Our bridges and other public edifices in like manner are all modern—specimens of mushroom architectural aristocracy—very dignified and imposing, no doubt, in their aspect, but without any hallowing associations connected with remote times to make us respect them.

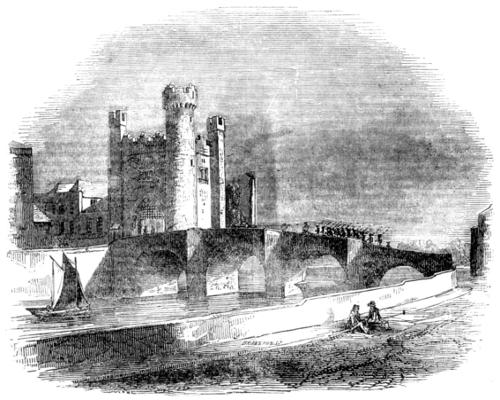

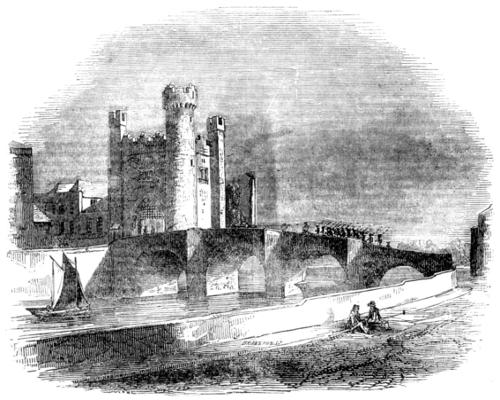

It is owing, perhaps, to these circumstances that we have always had a pleasure in seeing the old-looking bridge and gateway which form the subject of our prefixed illustration—we say old-looking, for in reality neither is very old: but they have an antique appearance about them which prevents us from thinking our city a mere creation of yesterday. They are very picturesque also, and contrast well with the other bridge scenes along our quays, which, though more splendid and architectural, are as yet too new-looking and commonplace.

Though Barrack Bridge, or, as it is more popularly called, Bloody Bridge, is now the oldest of the eight bridges which span the Liffey within our city, its antiquity is no earlier than the close of the seventeenth century: and yet this very bridge is the second structure of the kind erected in Dublin, as previously to its construction there was but one bridge—the Bridge, as it was called, connecting Bridge-street with Church-street—across the Liffey. And this fact is alone sufficient to prove the advance in prosperity and the arts of civilised life which Dublin has made within a period of little more than a century.

Barrack Bridge was originally constructed of wood, and was erected in 1670; and its popular name of Bloody Bridge[Pg 266] was derived, as Harris the historian states, from the following circumstance, which occurred in the year after. The apprentices of Dublin having assembled themselves riotously together with an intention to break down the bridge, it became necessary to call out the military to defeat their object, when twenty of the rioters were seized, and committed to the Castle. It happened, however, afterwards, that as a guard of soldiers were conveying these young men to the Bridewell, they were rescued by their fellows, and in the fray four of them were slain; “from which accident it took the name of Bloody Bridge.” In a short time afterwards, this wooden structure gave place to the stone bridge we now see, which is of unadorned character, and consists of four semicircular arches. Its rude and antique appearance, however, harmonizes well with the military gateway placed at its south-western extremity, on the road leading to the Royal Hospital at Kilmainham. This gateway, which was designed by the late eminent architect, Francis Johnston, Esq. P.R.H.A., and erected for government, under his superintendence, in 1811, consists of a square tower, having smaller square towers projecting from three of its angles, and a circular one of greater diameter and altitude at its fourth or north-eastern angle. The object for which this gateway tower was erected, as well as the period of its erection, is indicated by escutcheons on its east and west sides, bearing the arms of the Duke of Richmond and the Earl of Harrington, the lord-lieutenant and the commander of the forces of the time. A similar shield on its north side facing the river, sculptured with the armorial bearings of the family of Johnston, indicates the name of its architect; and it is worthy of mention as a characteristic of the love for posthumous fame of Mr Johnston, that this tablet was not known to exist till within a few years back, and after he had himself paid the debt of nature; having been concealed from view by a box of wood fastened against it, and which was suffered to remain—a strange mystery to the curious observer—till it fell off from decay.

P.

BY MARTIN DOYLE.

Among the common Irish farmers, indifference to the quality of all seeds is still remarkable. Even in respect to wheat, that most valuable grain, stupidity and carelessness are observable, though the loss sustained in consequence, both in the quantity and quality of the produce, is very great. It is no doubt principally owing to the superiority of climate that wheat and other corn crops grown in the midland counties of England are so far superior to our grain productions; but much of the excellence which we perceive is attributable to the care taken in changing seed, and using that only which is really good. An English farmer will send his waggon a considerable distance for the seed which will best answer for his land, and he is willing to pay an advanced price for it, as he knows that his advantage will be proportional.

We do not import from the principal wheat counties of England a sufficient quantity of seed: degeneracy rapidly takes place in the quality of that which we do sow of imported grain, and on that account a regular and frequent change is necessary, and by the more economical distribution of this, the difference between the prices of home-grown and imported seed would be scarcely felt. Not that I would recommend, except in some of our most calcareous inland counties, those white varieties which flourish in Kent, or Suffolk, or Buckinghamshire, but the hardier red Lammas kinds which succeed with us in general, but which require frequent renewal, else they become thick skinned and dark coloured, and consequently of inferior value to the miller. By substituting the drill system for the broad-cast in fit seasons, and on land perfectly suited to it, one part in four, certainly one in five, is saved, even by those who sow in the narrowest possible drills, and thickly.

I shall detail the mode by which the land is prepared for sowing, and the process of sowing, in Buckinghamshire, on clover ley, the most troublesome for the purpose:—

Farm-yard manure being spread upon the surface, wheel ploughs drawn by three powerful horses are set to work to plough the land in the usual British way. In wide lands or stitches, after the sod has been turned and laid at an angle of forty-five degrees, the seed is sometimes then sown and harrowed down. But the neatest farmers, instead of sowing at this stage of the work, employ a compressing implement formed of two parallel metal wheels at one end of an axle, and very close to each other, and a guide wheel of the same diameter at the other end. The interior rims of the compressing wheels (or rollers) are four inches wide, and nearly touch each other; the exterior surfaces are narrowed to two inches; these wheels sink into the earth at the junctions of the furrow slices, and by pressing down the grassy edges, and forming perfect grooves at the intervals of seven or nine inches, the seed may be sown with extreme exactness, and without the loss of a single grain, and at a uniform depth. But though the seed is frequently sown with the preparation just stated, the practice of the neatest and most judicious farmers is to harrow down these drills after the rollers have formed and completed them, and then to sow with the Suffolk drill-machine in the free and pulverized surface. This implement forms and sows several shallow drills at each bouting, and with perfect precision; the experienced eye of the man who follows in the rear, enabling him in an instant to perceive any possible irregularity in the movement of the hoppers and distribution of the seed.

The great advantage derived from the action of these compressing wheels is, that the grassy edges of the furrow slices are prevented altogether from vegetating by the depth to which they are removed from the surface, and that the pressure of the portions into which the rollers sink, is far more effective and consolidating than if an ordinary broad roller were to pass over the entire area. In preparing any loose fallow land for vetches, these compressing rollers are very serviceable. By following two ploughs, and in the same tracks, the ploughing and the perfect formation of the drills by pressure are accomplished in the same space of time, the two wheels obviously describing double the number of furrows described by each plough in the same period.

In heavy clay soils this compression is at least unnecessary, and in stony land drilling is difficult and unadvisable, but in light open soils the advantages of this system are considerable. The proper season for sowing is also a point of great consideration, both as regards the economy of seed of any kind, and the productiveness of the crop.

Some people labour to effect their seed-sowing on a particular day or week without other calculations, and are quite satisfied that all is well if the seed is in the ground at the precise time which they have appointed for the purpose. Now, any rule as to time alone is especially absurd in our variable climate; even in the midland counties of England, where extreme vicissitudes of weather are less frequent, it is injudicious to fix any certain rule as to the exact time for committing the various sorts of corn to the ground. Experience has taught those who have considered the subject, that it is unwise to force a season. For example, the middle of October is considered in Buckinghamshire to be the best time for sowing wheat; but the earth at that time may be so dry (and actually was so in the past year) as to be more fit for barley than wheat; or it may then be so wet as to be equally unfit for the reception of the seed. In either case the judicious farmer waits for the correct season, which experience has taught will have a corresponding harvest.

After a wet cold summer the light dry soils of that county being firm and consolidated, it is perhaps desirable to sow wheat at a very early period of the autumn; and after a hot dry summer, when the land is in a contrary condition, it would be better to wait for the autumnal rains to obtain a firm seed bed. Again, with barley on the same soil, the first of April is considered a good time; but the farmer who should persist in sowing just then in spite of the weather or the unprepared state of the land, would be a fool indeed, and would discover the effect of his blunder in the shortness of his crop. It is true that the superstitions of the ancients which so ridiculously influenced the affairs of husbandry, have long since ceased to be regarded. No one in these days would think it expedient to steep his seed in the juice of wild cucumbers; nor to bring it into contact with the horns of an ox, for luck; nor to cover the seed basket with the skin of a hyæna, to keep off by its odour the attacks of vermin; nor to sprinkle corn before sowing with water in which stags’ horns or crabs had been immersed; nor to mix powdered cypress leaves through the seed—though pickles and solutions for destroying insects are not to be despised. Neither are the planetary influences now much respected; yet there are[Pg 267] many foolish old farmers who attach no little importance to the state of the moon, the dark nights in November being a favourite season, without the really important considerations that the earth and the weather are in an appropriate and congenial state.

I have stated that the drills formed by the Suffolk drill-machine are very shallow; they are merely sufficient to afford about an inch of covering to the grain; but I have been assured by the best judges that the natural tendency of the cereal grains to strike their fibres is such that a heavy covering is unnecessary. Our national opinion is in favour of a heavy covering, and our wheat especially is actually imbedded deeply in the ground with a plough.

The practice in Great Britain universally is to harrow in the grain. The same practice is universally prevalent in France, where the land is left roughly harrowed (in the case of winter wheat), in order that the mouldering of the clods in spring may afford a kind of earthing to the plants, and prevent the running together of the earth in the wet winter months, as is too frequent on tenacious soils too finely harrowed.

It is not very long since the advantage of compressing the soil, for wheat in particular, was discovered in Buckinghamshire, by the accidental circumstance of a roller (which had been used for some different purpose) having been drawn in a zig-zag direction across a wheat field. The plants tillered better, looked far more vigorous during their advance to maturity, and yielded a far better return on the part of the field so distinguished by the course of the rollers, which soon after became a favourite implement in the culture of grain crops.

There is no doubt that all seeds are frequently sown with wasteful prodigality, because they are cheap or indifferent in quality. How much better then is it to have those of superior quality, though at a higher price, and to encourage the distribution of them in the soil by a careful mode of sowing!

Grains of corn of superior excellence are frequently selected with great care, as by Colonel le Couteur, in Jersey, and then sown with a dibble in seedling beds. The plants thus carefully treated tiller surprisingly, and produce accordingly; after two or three seasons, a fine variety, or a renovation of some previously established one, is obtained, and the seed is anxiously sought for.

Do any of our farmers ever dream of going through their corn fields in harvest, and thus obtain choice seeds? And yet what is there to prevent success in this respect? A poor farmer who cannot afford to purchase celebrated varieties at a high cost, may become his own seedsman, by care and assiduity, in an incredibly short time. Let some of our readers make the desired experiments for their own sakes.

On the Theory of Suspension Bridges, with some account of their early history. By Mr G. F. Fordham. Head at the Scientific Society, March 12, 1840.

Suspension Bridges appear to be of very ancient origin: travellers have discovered their existence in South America, in China, in Thibet, and in the Indian peninsula. They are most frequently met with in mountainous regions, and being suspended across a deep ravine, or an impetuous torrent, permit the passage of the traveller where the construction of any other kind of bridge would be entirely impracticable. Humboldt informs us that in South America there are numerous bridges of this kind formed of ropes made from the fibrous parts of the roots of the American agavey (Agave Americana). These ropes, which are three or four inches in diameter, are attached on each bank to a clumsy framework composed of the trunk of the Schinus molle; where, however, the banks are flat and low, this framework raises the bridge so much above the ground as to prevent it from being accessible. To remedy this inconvenience, steps or ladders are in these cases placed at each extremity of the bridge, by ascending which all who wish to pass over readily reach the roadway. The roadway is formed by covering the ropes transversely with small cylindrical pieces of bamboo. The bridge of Penipé erected over the Chamboo is described as being 120 feet long and 8 feet broad, but there are others which have much larger dimensions. A bridge of this kind will generally remain in good condition 20 or 25 years, though some of the ropes require renewing every 8 or 10 years. It is worthy of remark, as evincing the high antiquity of these structures, that they are known to have existed in South America long prior to the arrival of Europeans. The utility of these bridges in mountainous countries is placed in a striking point of view by the fact mentioned by Humboldt, of a permanent communication having been established between Quito and Lima, by means of a rope bridge of extraordinary length, after 40,000l. had been expended in a fruitless attempt to build a stone bridge over a torrent which rushes from the Cordilleras or the Andes. Over this bridge of ropes, which is erected near Santa, travellers with loaded mules can pass in safety.

But suspension bridges composed of stronger and more durable materials than twisted fibres and tendrils of plants, are found to exist in these remote and semi-barbarous regions; in Thibet, as well as in China, many iron suspension bridges have been discovered, and it is no improbable conjecture that in countries so little known and visited by Europeans, others may exist, of which we have as yet received no accounts. The most remarkable bridge of this kind of which we have any knowledge in Thibet, is the bridge of Chuka-cha-zum, stretched over the Tehintchieu river, and situated about 18 miles from Murichom. Turner, in his Embassy to the Court of Thibet, says, “Only one horse is admitted to go over it at a time: it swings as you tread upon it, re-acting at the same time with a force that impels you every step you take to quicken your pace. It may be necessary to say, in explanation of its construction, that on the five chains which support the platform, are placed several layers of strong coarse mats of bamboo, loosely put down, so as to play with the swing of the bridge; and that a fence on each side contributes to the security of the passenger.” The date of the erection of this bridge is unknown to the inhabitants of the country, and they even ascribe to it a fabulous origin. The length of this bridge appears to be about 150 feet.

Turner describes in the following terms a bridge for foot passengers of an extraordinary construction. “It was composed of two chains stretched parallel to each other across the river, distant four feet from each other, and on either side resting upon a pile of stones, raised upon each bank about eight feet high; they were carried down with an easy slope and buried in the rock, where, being fastened round a large stone, they were confined by a quantity of broken rock heaped upon them. A plank about eight inches broad hung longitudinally suspended across the river by means of roots and creepers wound over the chains with a slackness sufficient to allow the centre to sink to the depth of four feet below the chains. This bridge, called Selo-cha-zum, measured, from one side of the water to the other, 70 feet. The creepers are changed annually, and the planks are all loose; so that if the creepers give way in any part, they can be removed, and the particular part repaired without disturbing the whole.”

Numerous suspension bridges formed of iron chains exist also in China; and though the accounts which travellers have transmitted respecting them are less detailed and explicit than would have been desirable, descriptions of two of them have been furnished, which are sufficiently minute and intelligible to excite considerable interest. The first to which I refer is contained in Kircher’s China Illustrata. The following is a translation of the author’s words: “In the province of Junnan, over a valley of great depth, and through which a torrent of water runs with great force and rapidity, a bridge is to be seen, said to have been built by the Emperor Mingus, of the family of the Hamæ, in the year of Christ 65, not constructed of brickwork, or of blocks of stone cemented together, but of chains of beaten iron and hooks, so secured to rings from both sides of the chasm, that it forms a bridge by planks placed upon them. There are 20 chains, each of which is 20 perches or 300 palms in length. When many persons pass over together, the bridge vibrates to and fro, affecting them with horror and giddiness, lest whilst passing it should be struck with ruin. It is impossible to admire sufficiently the dexterity of the architect Sinensius, who had the hardihood to attempt a work so arduous, and so conducive to the convenience of travelling.” Another suspension bridge in this country is described in the 6th vol. of the “Histoire Generale des Voyages.” The following is a translation: “The famous Iron Bridge (such is the name given to it) at Quay-Cheu, on the road to Yun-Nan (Junnan?) is the work of an ancient Chinese general. On the banks of the Pan-Ho, a torrent of inconsiderable breadth, but of great depth, a large gateway has been formed between two massive pillars, 6 or 7 feet broad, and from 17 to 18 feet in height. From the two pillars of the east depend four chains attached to large rings, which extend to the two pillars of the west, and[Pg 268] which being connected together by smaller chains, assume in some measure the appearance of a net. On this bridge of chains a number of very thick planks have been placed, some means of connecting which, have been adopted in order to obtain a continuous platform; but as a vacant space still remains between this platform and the gateways and pillars, on account of the curve assumed by the chains, especially when loaded, this defect has been remedied by the aid of planking supported on trusses or consoles. On each side of this planking small pilasters of wood have been erected, which support a roof of the same material, the two extremities of which rest on the pillars that stand on the banks of the river.” The writer proceeds to remark, that “the Chinese have made several other bridges in imitation of this. One, on the river Kin-cha-Hyang, in the ancient canton of Lo-Lo, which belongs to the province of Yun-Nan, is particularly known. In the province of Se-Chuen there are one or two others, which are sustained only by ropes; but though of an inconsiderable size, they are so unsteady and so little to be trusted that they cannot be crossed without sensations of fear.”

While our attention is directed to early accounts and to the origin of suspension bridges, it may be proper to remark, that although, as we have seen, the inhabitants of the mountainous districts of South America, or the wild and barbarous regions of Thibet, appear to have been well acquainted with the purposes for which these structures are best adapted, and to have practised their construction from the most remote ages, neither the Greeks, the Romans, nor the Egyptians, according to all we know of those nations, had any knowledge of their uses or properties, or ever employed them as a means for crossing a river, or other natural impediment. It is not, therefore, from these celebrated nations of antiquity that the engineer has derived his first hints for the construction of suspension bridges, but from those rude and unpolished people, the results of whose ingenuity have just been described.

But it will now be interesting to inquire how far we can trace back the antiquity of suspension bridges in more civilized countries—on the Continent, in the British Isles, and in the United States of America. Scamozzi speaks of suspension bridges existing in Europe in the beginning of the seventeenth century, but it is very questionable if he employed that term to designate the same structure to which it is now applied; and this is rendered the more improbable, as no such bridges are now in existence, and other writers are totally silent upon the subject. It does not appear, then, that suspension bridges of other than recent erection have existed on the Continent, and in England the oldest of which we have any account has not been constructed more than a century. The first suspension bridge in the United States was erected in the year 1796. In England the oldest bridge of the kind is believed to have been the Winch Chain Bridge, suspended over the Tees, and thus forming a communication between the counties of Durham and York. Mr Stevenson (Edinburgh Philosophical Journal) expresses his regret at not having been able to learn the precise date of the erection of this bridge; from good authority, however, he concludes it to be about the year 1741. It may also be mentioned here, that at Carric-a-rede, near Ballintoy, in Ireland, there is a rope bridge, which in 1800 was reported to have been in use longer than the present generation could remember.

In the years 1816 and 1817, some wire suspension bridges were executed in Scotland, and, though not of great extent, are the first example of this species of bridge architecture in Great Britain. As, however, full descriptions of these bridges are to be met with elsewhere, it will not be necessary to notice them further.

In 1818, Mr Telford was consulted by government as to the practicability of erecting a suspension bridge over the Menai Strait, and was commissioned to prepare a design, if upon an examination of the localities he found the project feasible. Having accordingly surveyed the spot, he was led to propose the construction of a suspension bridge near Bangor Ferry, and in 1819 an act was obtained, authorising the erection of the bridge, a sum of money having been previously voted by Parliament for that purpose. This structure, which will always be regarded as a monument of the engineering abilities of Telford, was commenced in August 1819, and opened to the public on the 30th January 1826, having occupied six and a half years in its erection. The Union Bridge across the Tweed was designed and executed by Captain Brown, and was the first bar chain bridge of considerable size that was completed in this country. It was commenced in August 1819, and finished in the month of July 1820. After the completion of the Menai Bridge, bridges on the suspension principle began to be universally adopted throughout Europe; but it was not till iron wires had been proved to be more firm than bars of a greater thickness that these bridges received their most extensive applications. Since 1821, Messrs Sequin have constructed more than fifty wire bridges in France with the most complete success. The wire suspension bridge at Freyburg, in Switzerland, the largest in the world, was erected by Mons. Challey, and depends across the valley of the Sarine. It was commenced in 1831, and thrown open to the public in 1834. A suspension bridge has also been erected at Montrose, the size of which is scarcely inferior to that of the Menai Bridge. At Clifton a very large suspension bridge is now in progress of erection by Mr Brunel, and a suspension bridge of 1600 feet in length is about to be erected over the Danube, between Pest and Offen, the design for which is the production of Mr W. Tierney Clark, and under whose able superintendence its construction will be effected.—Civil Engineer and Architect’s Journal.

That man should be happy, is so evidently the intention of his Creator, the contrivances to that end are so multitudinous and so striking, that the perception of the aim may be called universal. Whatever tends to make men happy, becomes a fulfilment of the will of God. Whatever tends to make them miserable, becomes opposition to his will.—Harriet Martineau.

BY W. CARLETON.

When a superstition is once impressed strongly upon the popular credulity, the fiction always assumes the shape and form which the peculiar imagination of the country is constituted to body forth. This faculty depends so much on climate, temperament, religion, and occupation, that the notions entertained of supernatural beings, though generally based upon one broad feature peculiar to all countries, differ so essentially respecting the form, character, habits, and powers of these beings, that they appear to have been drawn from sources widely removed. To an inquiring mind there can be no greater proof than this of their being nothing but the creations of our own brain, and of assuming that shape only which has uniformly been impressed upon our imagination at the precise period of life when such impressions are strongest and most permanent, and the reason which ought to combat and investigate them least capable of doing so. If these inane bugbears possessed the consistence of truth and reality, their appearance to mankind would be always uniform, unchangeable, and congruous; but they are beheld, so to speak, through different prejudices and impressions, and consequently change with the media through which they are seen. Hence their different shape, character, and attributes in different countries, and the frequent absence of rational analogy with respect to them even in the same.

Where now are the multitudinous creations of the old Greek and Roman mythologies? Where are their Lares, their Penates, their Fauns, Satyrs, Nymphs, Dryads, Hamadryads, Gods, and Goddesses? And yet the peasantry of the two most enlightened nations of antiquity were so firmly fixed in a belief of their distinct and individual existence, that the worship of them formed an essential part of their religion. Where are they now? And who believes in the existence of a Faun, a Dryad, or a Hamadryad? They melted into what they were—nothing—before the lustre of Revelation, which, by bringing the truth of immortality to light, banished the whole host of such incongruous monsters from the earth, and impressed the imagination of mankind with truer notions and simpler imagery. The pure but severe morality of the Christian religion, by making man sensible of his responsibility in another life, opened up to the good and rational the bright hopes of future happiness. But we have our fears as well as our hopes, and as these preponderate in proportion to our fitness for death, so will we view the world that is to come either with joy or terror. Every truth is abused and perverted by man’s moral delinquencies: and the consequence is, that an idle fear of ghosts and apparitions is an abuse of the doctrine of our immortality. Judgment and eternal life were brought near us by Revelation, but we fear them more than we love them, and hence the terrors of our imagination on thinking of any thing that is beyond the grave. As the old monsters of the mythologies disappeared before reason and religion, so also will ghosts, fairies, and all such nonsense, vanish when men shall be taught to reason upon them as they ought, and to entertain higher notions of God than to believe that his purposes could be thwarted by the power or malignity of a fairy. Why, what, for instance, is every ghost story that we have heard, granting them to be true, but a direct revelation, and so far antiscriptural and impious? What new truth has the information of a spectre ever conveyed to us? What knowledge of futurity beyond that which we already know have these dialogues with the dead ever brought to light? What view of our moral, religious, or social duties, with which we were not acquainted before, have apparitions ever taught us? None. Away, then, with these empty and pusillanimous chimeras, which are but the mere hallucinations of a weak judgment, acted upon and misled by a strong fancy or a guilty conscience.

The force of imagination alone is capable of conjuring up and shaping out that which never had existence, and that too with as much apparent distinctness and truth as if it was real. We all know that in the ease of a female who is pregnant, a strong impression made upon the imagination of the mother will be visible on the body of the child. And why? Because she firmly believes that it will be so. If she did not, no such impression would be communicated to the infant. But when such effects are produced in physical matters, what will not the consequence be in those that are purely mental and imaginative? Go to the lunatic asylum or the madhouse, and there it may be seen in all its unreal delusion and positive terror.

Before I close this portion of my little disquisition, I shall relate an anecdote connected with it, of which I myself was the subject. Some years ago I was seized with typhus fever of so terrific a character, that for a long time I lay in a state hovering between life and death, unconscious as a log, without either hope or fear. At length a crisis came, and, aided by the strong stamina of an unbroken constitution, I began to recover, and every day to regain my consciousness more and more. As yet, however, I was very far from being out of danger, for I felt the malady to be still so fiery and oppressive, that I was not surprised when told that the slightest mistake either in my medicine or regimen would have brought on a relapse. At all events, thank God, my recovery advanced; but, at the same time, the society that surrounded me was wild and picturesque in the highest degree. Never indeed was such a combination of the beautiful and hideous seen, unless in the dreams of a feverish brain like mine, or the distorted reason of a madman. At one side of my bed, looking in upon me with a most hellish and satanic leer, was a face, compared with which the vulgar representations of the devil are comeliness itself, whilst on the other was a female countenance beaming in beauty that was ethereal—angelic. Thus, in fact, was my whole bed surrounded; for they stood as thickly as they could, sometimes flitting about and crushing and jostling one another, but never leaving my bed for a moment. Here were the deformed features of a dwarf, there an angel apparently fresh from heaven; here was a gigantic demon with his huge mouth placed longitudinally in his face, and his nose across it, whilst the Gorgon-like coxcomb grinned as if he were vain, and had cause to be vain, of his beauty. This fellow annoyed me much, and would, I apprehend, have done me an injury, only for the angel on the other side. He made perpetual attempts to come at me, but was as often repulsed by that seraphic creature. Indeed, I feared none of them so much as I did the Gorgon, who evidently had a design on me, and would have rendered my situation truly pitiable, were it not for the protection of the seraph, who always succeeded in keeping him aloof. At length he made one furious rush as if he meant to pounce upon me, and in self-preservation I threw my right arm to the opposite side, and, grasping the seraph by the nose, I found I had caught my poor old nurse by that useful organ, while she was in the act of offering me a drink. For several days I was in this state, the victim of images produced by disease, and the inflammatory excitement of brain consequent upon it. Gradually, however, they began to disappear, and I felt manifest relief, for they were succeeded by impressions as amusing now as the former had been distressing. I imagined that there was a serious dispute between my right foot and my left, as to which of them was entitled to precedency; and, what was singular, my right leg, thigh, hand, arm and shoulder, most unflinchingly supported the right foot, as did the other limbs the left. The head alone, with an impartiality that did it honour, maintained a strict neutrality. The truth was, I imagined that all my limbs were endowed with a consciousness of individual existence, and I felt quite satisfied that each and all of them possessed the faculty of reason. I have frequently related this anecdote to my friends; but, I know not how it happened, I never could get them to look upon it in any other light than as a specimen of that kind of fiction which is indulgently termed “drawing the long bow.” It is, however, as true as that I now exist, and relate the fact; and, what is more, the arguments which I am about to give are substantially the same that were used by the rival claimants and their respective supporters. The discussion, I must observe, was opened by the left foot, as being the discontented party, and, like all discontented parties, its language was so very violent, that, had its opinions prevailed, there is no doubt but they would have succeeded in completely overturning my constitution.

Left foot. Brother (addressing the right with a great show of affection, but at the same time with a spasmodic twitch of strong discontentment in the big toe), Brother, I don’t know how it is that you have during our whole lives always taken the liberty to consider yourself a better foot than I am; and I would feel much obliged to you if you would tell me why it is that you claim this superiority over me. Are we not both equal in every thing?

Right foot. Be quiet, my dear brother. We are equal in every thing, and why, therefore, are you discontented?

Left foot. Because you presume to consider yourself the better and more useful foot.

Right foot. Let us not dispute, my dear brother; each is equally necessary to the other. What could I do without you? Nothing, or at least very little; and what could you do without me? Very little indeed. We were not made to quarrel.

Left foot (very hot). I am not disposed to quarrel, but I trust you will admit that I am as good as you, every way your equal, and begad in many things your superior. Do you hear that? I am not disposed to quarrel, you rascal, and how dare you say so?

Here there was a strong sensation among all the right members, who felt themselves insulted through this outrage offered to their chief supporter.

Right foot. Since you choose to insult me without provocation, I must stand upon my right——

Left (shoving off to a distance). Right!—there, again, what right have you to be termed “right” any more than I?—(“Bravo!—go it, Left; pitch into him; we are equal to him and his,” from the friends of the Left. The matter was now likely to become serious, and to end in a row.)

“What’s the matter there below?” said the Head; “don’t be fools, and make yourselves ridiculous. What would either of you be with a crutch or a cork-leg? which is only another name for a wooden shoe, any day.”

Right foot. Since he provokes me, I tell him, that ever since the world began, the prejudice of mankind in all nations has been in favour of the right foot and the right hand. (Strong sensation among the left members). Surely he ought not to be ignorant of the proverb, which says, when a man is peculiarly successful in any thing he undertakes, “that man knew how to go about it—he put the right foot foremost!” (Cheers from the right party.)

Left. That’s mere special pleading—the right foot there does not mean you, because you happen to be termed such; but it means the foot which, from its position under the circumstances, happens to be the proper one. (Loud applause from the left members.)

Right foot. You know you are weak and feeble and awkward when compared to me, and can do little of yourself. (Hurra! that’s a poser!)

Left. Why, certainly, I grant I am the gentleman, and that you are very useful to me, you plebeian. (“Bravo!” from the left hand; “ours is the aristocratic side—hear the operatives! Come, hornloof, what have you to say to that?”)

Right hand (addressing his opponent.) You may be the aristocratic party if you will, but we are the useful. Who are the true defenders of the constitution, you poor sprig of nobility?

Left hand. The heart is with us, the seat and origin of life and power. Can you boast as much? (Loud cheers.)

Right foot. Why, have you never heard it said of an excellent and worthy man—a fellow of the right sort, a trump—as a mark of his sterling qualities, “his heart’s in the right place!” How then can it be in the left? (Much applause.)

Left. Which is an additional proof that mine is that place and not yours. Yes, you rascal, we have the heart, and you cannot deny it.

Right. We admit he resides with you, but it is merely because you are the weaker side, and require his protection. The best part of his energies are given to us, and we are satisfied.

Left. You admit, then, that our party keeps yours in power, and why not at once give up your right to precedency?—why not resign?

Right. Let us put it to the vote.

Left. With all my heart.

It was accordingly put to the vote; but on telling the house, it was found that the parties were equal. Both then appealed very strenuously to Mr Speaker, the Head, who, after having heard their respective arguments, shook himself very gravely, and informed them (much after the manner of Sir Roger De Coverley) that “much might be said on both sides.” “But one thing,” said he, “I beg both parties to observe, and very seriously to consider. In the first place, there would be none of this nonsense about precedency, were it not for the feverish and excited state in which you all happen to be at present. If you have common sense enough to wait until you all get somewhat cooler, there is little doubt but you will feel that you cannot do without each other. As for myself, as I said before, I give no specific opinion upon disputes which would never have taken place were it not for the heat of feeling which is between you. I know that much might and has been said upon both sides; but as for me, I nod significantly to both parties, and say nothing. One thing, however, I do say, and it is this—take care you, right foot, and you, left foot, that by pursuing this senseless quarrel too far it may not happen that you will both get stretched and tied up together in a wooden surtout, when precedency will be out of the question, and nothing but a most pacific stillness shall remain between you for ever. I shake, and have concluded.”

Now, this case, which as an illustration of my argument possesses a good deal of physiological interest, is another key to the absurd doctrine of apparitions. Here was I at the moment strongly and seriously impressed with a belief that a quarrel was taking place between my two feet about the right of going foremost. Nor was this absurdity all. I actually believed for the time that all my limbs were endowed with separate life and reason. And why? All simply because my whole system was in a state of unusually strong excitement, and the nerves and blood stimulated by disease into a state of derangement. Such, in fact, is the condition in which every one must necessarily be who thinks he sees a spirit; and this, which is known to be an undeniable fact, being admitted, it follows of course that the same causes will, other things being alike, produce the same effects. For instance, does not the terror of an apparition occasion a violent and increased action of the heart and vascular system, similar to that of fever? Does not the very hair stand on end, not merely when the imaginary ghost is seen, but when the very apprehension of it is strong? Is not the action of the brain, too, accelerated in proportion to that of the heart, and the nervous system in proportion to that of both? What, then, is this but a fever for the time being, which is attended by the very phantasms the fear of which created it; for in this case it so happens that the cause and effect mutually reproduce each other.

The conversation detailed above is but a very meagre outline of what was said during the discussion. The arguments were far more subtle than the mere skeletons of them here put down, and very plentifully sprinkled over with classical quotations, both of Latin and Greek, which are not necessary now.

Hibbert mentions a case of imagination, which in a man is probably the strongest and most unaccountable on record. It is that of a person—an invalid—who imagined that at a certain hour of the day a carter or drayman came into his bedroom, and, uncovering him, inflicted several heavy stripes upon his body with the thong of his whip; and such was the power of fancy here, that the marks of the lash were visible in black and blue streaks upon his flesh. I am inclined to think, however, that this stands very much in need of confirmation.

I have already mentioned a case of spectral illusion which occurred in my native parish. I speak of Daly’s daughter, who saw what she imagined to be the ghost of M’Kenna, who had been lost among the mountains. I shall now relate another, connected with the fairies, of which I also was myself an eye-witness. The man’s name, I think, was Martin, and he followed the thoughtful and somewhat melancholy occupation of a weaver. He was a bachelor, and wrought journey-work in every farmer’s house where he could get employment; and notwithstanding his supernatural vision of the fairies, he was considered to be both a quick and an excellent workman. The more sensible of the country-people said he was deranged, but the more superstitious of them maintained that he had a Lianhan Shee, and saw them against his will. The Lianhan Shee is a malignant fairy, which, by a subtle compact made with any one whom it can induce by the fairest promises to enter into, secures a mastery over them by inducing its unhappy victims to violate it; otherwise, it is and must be like the oriental genie, their slave and drudge, to perform such tasks as they wish to impose upon it. It will promise endless wealth to those whom it is anxious to subjugate to its authority, but it is at once so malignant and ingenious, that the party entering into the contract with it is always certain by its manœuvres to break through his engagement, and thus become slave in his turn. Such is the nature of this wild and fearful superstition, which I think is fast disappearing, and is but rarely known in the country. Martin was a thin pale man, when I saw him, of a sickly look, and a constitution naturally feeble. His hair was a light[Pg 271] auburn, his beard mostly unshaven, and his hands of a singular delicacy and whiteness, owing, I dare say, as much to the soft and easy nature of his employment, as to his infirm health. In every thing else he was as sensible, sober, and rational as any other man; but on the topic of fairies, the man’s mania was peculiarly strong and immoveable. Indeed, I remember that the expression of his eyes was singularly wild and hollow, and his long narrow temples sallow and emaciated.

Now, this man did not lead an unhappy life, nor did the malady he laboured under seem to be productive of either pain or terror to him, although one might be apt to imagine otherwise. On the contrary, he and the fairies maintained the most friendly intimacy, and their dialogues—which I fear were woefully one-sided ones—must have been a source of great pleasure to him, for they were conducted with much mirth and laughter, on his part at least.

“Well, Frank, when did you see the fairies?”

“Whist! there’s two dozen of them in the shop (the weaving shop) this minute. There’s a little ould fellow sittin’ on the top of the sleys, an’ all to be rocked while I’m weavin’. The sorrow’s in them, but they’re the greatest little skamers alive, so they are. See, there’s another of them at my dressin’[1] noggin. Go out o’ that, you shingawn; or, bad cess to me if you don’t, but I’ll lave you a mark. Ha! out, you thief you!”

“Frank, aren’t you afear’d o’ them?”

“Is it me? Arra, what ’ud I be afear’d o’ them for? Sure they have no power over me.”

“And why haven’t they, Frank?”

“Becaise I was baptized against them.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“Why, the priest that christened me was tould by my father to put in the prayer against the fairies—an’ a priest can’t refuse it when he’s axed—an’ he did so. Begorra, it’s well for me that he did—(let the tallow alone, you little glutton—see, there’s a weeny thief o’ them aitin’ my tallow)—becaise, you see, it was their intention to make me king o’ the fairies.”

“Is it possible?”

“Devil a lie in it. Sure you may ax them, an’ they’ll tell you.”

“What size are they, Frank?”

“Oh, little wee fellows, with green coats an’ the purtiest little shoes ever you seen. There’s two o’ them—both ould acquaintances o’ mine—runnin’ along the yarn beam. That ould fellow with the bob wig is called Jim Jam, an’ the other chap with the three-cocked hat is called Nickey Nick. Nickey plays the pipes. Nickey, give us a tune, or I’ll malivogue you—come now, ‘Lough Erne Shore.’ Whist, now—listen!”

The poor fellow, though weaving as fast as he could all the time, yet bestowed every possible mark of attention to the music, and seemed to enjoy it as much as if it had been real. But who can tell whether that which we look upon as a privation may not after all be a fountain of increased happiness, greater perhaps than any which we ourselves enjoy? I forget who the poet is who says,

Many a time when a mere child not more than six or seven years of age, have I gone as far as Frank’s weaving-shop, in order, with a heart divided between curiosity and fear, to listen to his conversation with the good people. From morning till night his tongue was going almost as incessantly as his shuttle; and it was well known that at night, whenever he awoke out of his sleep, the first thing he did was to put out his hand and push them as it were off his bed.

“Go out o’ this, you thieves you—go out o’ this, now, an’ let me alone. Nickey, is this any time to be playin’ the pipes, and me wants to sleep? Go off, now—troth if yez do, you’ll see what I’ll give yez to-morrow. Sure I’ll be makin’ new dressins; and if yez behave dacently, maybe I’ll lave yez the scrapin’ o’ the pot. There now. Och! poor things, they’re dacent crathurs. Sure they’re all gone barrin’ poor Red-cap, that doesn’t like to lave me.” And then the harmless monomaniac would fall back into what we trust was an innocent slumber.

About this time there was said to have occurred a very remarkable circumstance, which gave poor Frank a vast deal of importance among the neighbours. A man named Frank Thomas, the same in whose house Mickey McGrory held the first dance at which I ever saw him, as detailed in a former number of this Journal—this man, I say, had a child sick, but of what complaint I cannot now remember, nor is it of any importance. One of the gables of Thomas’s house was built against or rather into a Forth or Rath called Towny, or properly Tonagh Forth. It was said to be haunted by the fairies, and what gave it a character peculiarly wild in my eyes, was, that there were on the southern side of it two or three little green mounds, which were said to be the graves of unchristened children, over which it was considered dangerous and unlucky to pass. At all events, the season was mid-summer; and one evening about dusk, during the illness of the child, the noise of a handsaw was heard upon the Forth. This was considered rather strange, and after a little time, a few of those who were assembled at Frank Thomas’s went to see who it could be that was sawing in such a place, or what they could be sawing at so late an hour, for every one knew that there was none in the whole country about them who would dare to cut down the few whitethorns that grew upon the forth. On going to examine, however, judge of their surprise, when, after surrounding and searching the whole place, they could discover no trace of either saw or sawyer. In fact, with the exception of themselves, there was no one, either natural or supernatural, visible. They then returned to the house, and had scarcely sat down, when it was heard again within ten yards of them. Another examination of the premises took place, but with equal success. Now, however, while standing on the forth, they heard the sawing in a little hollow, about a hundred and fifty yards below them, which was completely exposed to their view, but they could see nothing. A party of them immediately went down to ascertain if possible what this singular noise and invisible labour could mean; but on arriving at the spot, they heard the sawing, to which were now added hammering and driving of nails, upon the forth above, whilst those who stood on the forth continued to hear it in the hollow. On comparing notes, they resolved to send down to Billy Nelson’s for Frank Martin, a distance only of about eighty or ninety yards. He was soon on the spot, and without a moment’s hesitation solved the enigma.

“’Tis the fairies,” said he. “I see them, and busy crathurs they are.”

“But what are they sawing, Frank?”

“They are makin’ a child’s coffin,” he replied; “they have the body already made, an’ they’re now nailin’ the lid together.”

That night the child certainly died, and the story goes, that on the second evening afterwards, the carpenter who was called upon to make the coffin brought a table out from Thomas’s house to the forth, as a temporary bench; and it is said that the sawing and hammering necessary for the completion of his task were precisely the same which had been heard the evening but one before—neither more nor less. I remember the death of the child myself, and the making of its coffin, but I think that the story of the supernatural carpenter was not heard in the village for some months after its interment.

Frank had every appearance of a hypochondriac about him. At the time I saw him, he might be about thirty-four years of age, but I do not think, from the debility of his frame and infirm health, that he has been alive for several years. He was an object of considerable interest and curiosity, and often have I been present when he was pointed out to strangers as “the man that could see the good people.” With respect to his solution of the supernatural noise, that is easily accounted for. This superstition of the coffin-making is a common one, and to a man like him, whose mind was familiar with it, the illness of the child would naturally suggest the probability of its death, which he immediately associated with the imagery and agents to be found in his unhappy malady.

[1] The dressings are a species of sizy flummery, which is brushed into the yarn to keep the thread round and even, and to prevent it from being frayed by the friction of the reed.

Antiquity of Railways and Gas.—Railways were used in Northumberland in 1633, and Lord Keeper North mentions them in 1671 in his journey to this country. A Mr Spedding, coal-agent to Lord Lonsdale, at Whitehaven, in 1765, had the gas from his lordship’s coal-pits conveyed by pipes into his office, for the purpose of lighting it, and proposed to the magistrates of Whitehaven to convey the gas by pipes through the streets to light the town, which they refused.—Carlisle Journal.

The Hungarian Nobility.—There is no country under heaven where nobility is at so low a par, or rather perhaps I should say, on so unequal a basis; and I was so much amused by the classification lately bestowed on it by a humorous friend of mine, to whom I had frankly declared my inability to disentangle its mazes, that I will give it in his own words.

“The nobility of Hungary are of three orders—the mighty, the moderate, and the miserable—the Esterhazys, the Batthyanyis, and such like, are the capital of the column—the shaft is built of the less wealthy and influential; and the base (and a very substantial one it is) is a curious congeries of small landholders, herdsmen, vine-growers, waggoners, and pig-drivers. Nay, you may be unlucky enough to get a nemes as a servant; and this is the most unhappy dilemma of all, for you cannot solace yourself by beating him when he offends you, as he is protected by his privileges, and he appeals to the Court of the Comitat for redress. The country is indebted to Maria Theresa for this pleasant confusion; who, when she repaid the valour of the Hungarian soldiers with a portion of their own land, and a name to lend it grace, forgot that many of these individuals were probably better swordsmen than proprietors; and instead of limiting their patent of nobility to a given term of years, laid the foundation of a state of things as inconvenient as it is absurd.”

I was immediately reminded by his closing remark of a most ridiculous scene, which, although in itself a mere trifle, went far to prove the truth of his position. My readers are probably aware that none pay tolls in Hungary save the peasants; and it chanced that on one occasion, when we were passing from Pesth to Buda over the bridge of boats, the carriage was detained by some accidental stoppage just beside the tollkeeper’s lodge, when our attention was arrested by a vehement altercation between the worthy functionary, its occupant, and a little ragged urchin of 11 or 12 years of age, who had, as it appeared, attempted to pass without the preliminary ceremony of payment.

The tollkeeper handled the supposed delinquent with some roughness as he demanded his fee: but the boy stood his ground stoutly, and asserted his free right of passage as a nobleman! The belligerent party pointed to the heel-less shoes and ragged jerkin of the culprit, and smiled in scorn. The lad for all reply bade him remove his hand from his collar, and let him pass at his peril; and the tone was so assured in which he did so, that the tollkeeper became grave, and looked somewhat doubtful; when just at the moment up walked a sturdy peasant, who, while he paid his kreutzer, saluted the young nobleman, and settled the point.

It was really broad farce. The respectably clad and comfortable looking functionary loosed his hold in a moment, and the offending hand, as it released the collar of the captive, lifted his hat, while he poured out his excuses for an over-zeal, arising from his ignorance of the personal identity of this young scion of an illustrious house, who was magnanimously pleased to accept the apology, and to raise his own dilapidated cap in testimony of his greatness of soul, as he walked away in triumph. Cruikshank would have had food for a chef d’œuvre.—Miss Pardoe’s Hungary.

African Administration of Justice.—On coming out of my hut at Fandah one morning, I saw the king seated at the gate of his palace, surrounded by his great men, administering justice. At a little distance, on the grass, were two men and two women, who were charged with robbery. The evidence had already been gone through before my arrival. The king was the principal speaker, and when he paused, the whole court murmured approbation. The younger woman made a long defence, and quite astonished me by her volubility, variety of intonation, and graceful action. The appeal, however, seemed to be in vain; for when she had finished, the king, who had listened with great patience, passed sentence in a speech of considerable length, delivered with great fluency and emphasis. In many parts he was much applauded, except by the poor wretches, who heard their doom with shrieks of despair. The king then retired, the court broke up, and the people dispersed. None remained but the prisoners and a decrepit old man, who, with many threats and some ceremony, administered a small bowl of poison, prepared, I believe, from the leaves of a venerable tree in the neighbourhood, which was hooped and propped all round. The poor creatures received the potion on their knees, and before they could be induced to swallow it, cast many a lingering look and last farewell on the beautiful world from which a small draught was about to separate them. They afterwards drank a prodigious quantity of water; and when I next went out, the dose had done its deadly work. I cannot tell how far justice was truly administered, but there was a great appearance of it; and I must say that I never in any court saw a greater display of decorum and dignity.—Allan’s Views on the Niger.

The Planing-machine Room in Messrs Fawcett and Co.’s Engine Factory, Liverpool.—In this room are valuable and elaborately contrived machines for the planing or levelling of large plates, or other pieces of iron or brass, so as to give them a smooth, true, and polished surface. The article or piece to be planed is securely fixed by screw-bolts, &c. to a horizontal iron table, perforated with holes for the insertion of the bolts from beneath it in any required point, to suit the size or form of the article. This table, when put in motion, travels backwards and forwards with its load on two iron rails, or parallel slides. Over the centre is perpendicularly fixed what is called the “planing tool,” an instrument made of steel, somewhat in the form of a hook, with the point so inclined as to present itself towards the surface of the metal to be planed, as it approaches it on the table, so as, when all is adjusted, to plough or plane it in narrow streaks or shavings as it passes under it. The extremity of the tool is about half an inch to three quarters in breadth, and being of a round form at the under side, and ground or bevelled on the upper, presents a sort of point. If a plate of iron is to be planed, the operation commences on the outer edge, and each movement backwards and forwards of the table places it in such a position under the tool, that another small parallel cut is made throughout its whole length. The tool, in ordinary machines of this kind, is fixed so that it cuts only in one direction, as the plate is drawn against its edge or point, which is raised to allow of the backward motion of the plate. A new patent has however been obtained for a great improvement in this respect by Mr Whitworth, of Manchester, and several of his machines are on Messrs Fawcett and Co.’s premises. In these, by a peculiarly beautiful contrivance, the cutting instrument, the moment the plate passes under it, “jumps” up a little in the box or case to which it is attached, and instantly “turns about” in the opposite direction, and commences cutting away, so that both backwards and forwards the operation goes on without loss of time. The workmen very quaintly and appropriately call this new planing tool “Jim Crow.” A workman attends to each of the machines; and when the piece to be cut is fixed with great exactness on the moving table by a spirit-level, he has nothing to do but to watch that it remain so, and that the machinery work evenly and correctly. Where a very smooth surface is required, the operation of planing is repeated, and two plates thus finished will be so truly level, that they will adhere together. It should be added, that so perfect are these machines, that in addition to planing horizontally, they may be so adjusted as to plane perpendicularly, or at any given angle.

The planet revolves for ever in its appointed orbit; and the noblest triumph of mechanical philosophy is to have ascertained that the perturbations of its course are all compensated within determined periods, and its movement exempted from decay. But man, weak and erring though he be, is still progressive in his moral nature. He does not move round for ever in one unvarying path of moral action. The combinations of his history exhibit not only the unity of the material system, but also the continually advancing improvement belonging to beings of a higher order.—Miller’s “Modern History philosophically considered.”

To Prevent Horses’ Feet from Clogging up with Snow.—One pound of lard, half a pound of tar, and two ounces of resin, simmered up together. Stop the horses’ feet, just before starting, with this, which will prevent the feet from balling.—Suffolk Chronicle.

Conscience is merely our own judgment of the moral rectitude or turpitude of our own actions.—Locke.

Printed and published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron, at the Office of the General Advertiser, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; Slocombe & Simms, Leeds, Fraser and Crawford, George Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.