| Number 18. | SATURDAY, OCTOBER 31, 1840. | Volume I. |

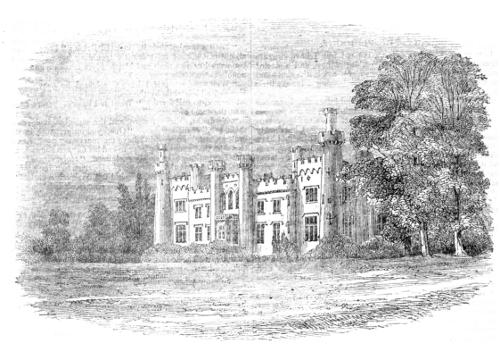

Woodlands, the seat of one of our good resident landlords, Colonel White, considered in connection with its beautiful demesne, may justly rank as the finest aristocratic residence in the immediate vicinity of our metropolis. As an architectural composition, indeed, the house, or castle, as it is called, will not bear a comparison, either for its classical correctness of details, or its general picturesqueness of outline, with the Castle of Clontarf—the architectural gem of our vicinity; but its proportions are on a grander scale, and its general effect accordingly more imposing, while its demesne scenery, in its natural beauties, the richness of its plantations, and other artificial improvements, is without a rival in our metropolitan county, and indeed is characterised by some features of such exquisite beauty as are very rarely found in park scenery any where, and which are nowhere to be surpassed. Well might the Prince Pückler Muskau, who despite of his strange name has undoubtedly a true taste for the beautiful and picturesque, describe the entrance to this demesne as “indeed the most delightful in its kind that can be imagined.” “Scenery,” he continues, “by nature most beautiful, is improved by art to the highest degree of its capability, and, without destroying its free and wild character, a variety and richness of vegetation is produced which enchants the eye. Gay shrubs and wild flowers, the softest turf and giant trees, festooned with creeping plants, fill the narrow glen through which the path winds, by the side of the clear dancing brook, which, falling in little cataracts, flows on, sometimes hidden in the thicket, sometimes resting like liquid silver in an emerald cup, or rushing under overhanging arches of rock, which nature seems to have hung there as triumphal gates for the beneficent Naïad of the valley to pass through.”

This description may appear somewhat enthusiastic, but we can truly state as our own opinion, formed on a recent visit to Woodlands, that it is by no means overdrawn, but, on the contrary, that it would be equally difficult, if not impossible, either for the pencil or the pen to convey an adequate idea of the peculiar beauties of this little tract of fairy land.

Singularly beautiful, however, as this sylvan glen unquestionably is, it is only one of the many features for which Woodlands is pre-eminently distinguished. Its finely undulating surface—its sheets of water, though artificially formed—its noble forest timber—but above all, its woodland walks, commanding vistas of the exquisite valley of the Liffey, with the more remote scenery bounded by the Dublin and Wicklow mountains—all are equally striking, and present a combination of varied and impressive features but rarely found within the bounds of even a princely demesne.

Though Woodlands derives very many of its attractions from modern improvements, its chief artificial features are of no recent creation, and are such as it would require a century or two to bring to their present perfection. Woodlands is emphatically an old place, and is said to have been granted by King John to Sir Geoffry Lutterel, an Anglo-Norman knight who accompanied him into Ireland, and in possession of whose descendants it remained, and was their residence from the close of the fifteenth till the commencement of the present century, when it was sold to Mr Luke White by the last Earl of Carhampton. Up to this period it was known by[Pg 138] the name of Lutterelstown, a name which, for various reasons, the family into whose possession it has passed have wisely changed.

The principal parts of the mansion were rebuilt about fifty years back. But a portion of the original castle still remains, and an apartment in it bears the name of King John’s chamber. It has also received additional extension from its present proprietor, who is now making further additions to the structure.

Woodlands is situated on the north bank of the Liffey, about five miles from Dublin.

P.

“And now, Mickey Brennan, it’s not but I have a grate regard for you, for troth you’re a dacint boy, and a dacint father and mother’s child; but you see, avick, the short and the long of it is, that you needn’t be looking after my little girl any more.”

Such was the conclusion of a long and interesting harangue pronounced by old Brian Moran of Lagh-buoy, for the purpose of persuading his daughter’s sweetheart to waive his pretensions—a piece of diplomacy never very easy to effect, but doubly difficult when the couple so unceremoniously separated have laboured under the delusion that they were born for each other, as was the ease in the affair of which our story tells; and certainly, whatever Mr Michael Brennan’s other merits may have been, he was very far from exhibiting himself as a pattern of patience on the occasion.

“Why, thin, Brian Moran!” he outrageously exclaimed, “in the name of all that’s out of the way, will you give me one reason, good, bad, or indifferent, and I’ll be satisfied?”

“Och, you unfortunate gossoon, don’t be afther axing me,” responded Brian dolefully.

“Ah, thin, why wouldn’t I?” replied the rejected lover. “Aren’t we playing together since she could walk—wasn’t she the light of my eyes and the pulse of my heart these six long years—and when did one of ye ever either say or sign that I was to give over until this blessed minute?—tell me that.”

“Widdy Eelish!” groaned the closely interrogated parent; “’tis true enough for you. Botheration to Peggy, I wish she tould you herself. I knew how it ’ud be; an’ sure small blame to you; an’ it’ll kill Meny out an’ out.”

“Is it that I amn’t rich enough?” he asked impetuously.

“No, avich machree, it isn’t; but, sure, can’t you wait an’ ax Peggy.”

“Is it because there’s any thing against me?” continued he, without heeding this reference to the mother of his fair one—“Is it because there’s any thing against me, I say, now or evermore, in the shape of warrant, or summons, or bad word, or any thing of the kind?”

“Och, forrear, forrear!” answered poor Brian, “but can’t you ax Peggy!” and he clasped his hands again and again with bitterness, for the young man’s interest had been, from long and constant habit, so interwoven in his mind with those of his darling Meny, that he was utterly unable to check the burst of agony which the question had excited. The old man’s evident grief and evasion of the question were not lost upon his companion.

“I’m belied—I know I am—I have it all now,” shouted he, utterly losing all command of himself. “Come, Brian Moran, this is no child’s play—tell me at once who dared to spake one word against me, an’ if I don’t drive the lie down his throat, be it man, woman, or child, I’m willing to lose her and every thing else I care for!”

“No, then,” answered Brian, “the never a one said a word against you—you never left it in their power, avich; an’ that’s what’s breaking my heart. Millia murther, it’s all Peggy’s own doings.”

“What!” he replied—“I’ll be bound Peggy had a bad dhrame about the match. Arrah, out with it, an’ let us hear what Peggy the Pishogue has to say for herself—out with it, man; I’m asthray for something to laugh at.”

“Oh, whisht, whisht—don’t talk that way of Peggy any how,” exclaimed Brian, offended by this imputation on the unerring wisdom of his helpmate. “Whatever she says, doesn’t it come to pass? Didn’t it rain on Saturday last, fine as the day looked? Didn’t Tim Higgins’s cow die? Wasn’t Judy Carney married to Tom Knox afther all? Ay, an’ as sure as your name is Mickey Brennan, what she says will come true of yourself too. Forrear, forrear! that the like should befall one of your dacint kin!”

“Why, what’s going to happen me?” inquired he, his voice trembling a little in spite of all his assumed carelessness: for contemptuously as he had alluded to the wisdom of his intended mother-in-law, it stood in too high repute not to create in him some dismay at the probability of his figuring unfavourably in any of her prognostications.

“Don’t ax me, don’t ax me,” was the sorrowing answer; “but take your haste out of the stable at once, and go straight to Father Coffey; and who knows but he might put you on some way to escape the bad luck that’s afore you.”

“Psha! fudge! ’pon my sowl it’s a shame for you, Brian Moran.”

“Divil a word of lie in it,” insisted Brian; “Peggy found it all out last night; an’ troth it’s troubling her as much as if you were her own flesh and blood. More betoken, haven’t you a mole there under your ear?”

“Well, and what if I have?” rejoined he peevishly, but alarmed all the while by the undisguised pity which his future lot seemed to call forth. “What if I have?—hadn’t many a man the same afore me?”

“No doubt, Mickey, agra, and the same bad luck came to them too,” replied Brian. “Och, you unfortunate ignorant crathur, sure you wouldn’t have me marry my poor little girl to a man that’s sooner or later to end his days on the gallows!”

“The gallows!” he slowly exclaimed. “Holy Virgin! is that what’s to become of me after all?” He tried to utter a laugh of derision and defiance, but it would not do; such a vaticination from such a quarter was no laughing matter. So yielding at last to the terror which he had so vainly affected to combat, he buried his face in his hands, and threw himself violently on the ground; while Brian, scarcely less moved by the revelation he had made on the faith of his wife’s far-famed sagacity, seated himself compassionately beside him to administer what consolation he could.

Mickey Brennan, in the parlance of our country, was a snug gossoon, well to do in the world, had a nice bit of land, a comfortable house, good crops, a pig or two, a cow or two, a sheep or two, a handsome good-humoured face, a good character; and, what made him more marriageable than all the rest, he had the aforementioned goods all to himself, for his father and mother were dead, and his last sister had got married at Shrove-tide. With all these combined advantages he might have selected any girl in the parish; but his choice was made long years before: it was Meny Moran or nobody—a choice in which Meny Moran herself perfectly concurred, and which her father, good, easy, soft-hearted Brian, never thought of disputing, although he was able to give her a fortune probably amounting to double what her suitor was worth. But was the fair one’s mother ever satisfied when such a disparity existed? Careful creatures! pound for pound is the maternal maxim in all ages and countries, and to give Peggy Moran her due, she was as much influenced by it as her betters, and murmured loud and long at the acquiescence of her husband in such a sacrifice. She murmured in vain, however: much as Brian deferred to her judgment and advice in all other matters, his love for his fond and pretty Meny armed him with resolution in this. When she wept at her mother’s insinuations, he always found a word of comfort for her; and if words wouldn’t do, he managed to bring Mickey and her together, and left them to settle the matter after their own way—a method which seldom failed of success. But Peggy was not to be baulked of her will. What! she whose mere word could make or break any match for five miles round, to be forbidden all interference in her own daughter’s: it was not to be borne. So at last she applied herself in downright earnest to the task. She dreamed at the match, tossed cups at it, saw signs at it: in fine, called her whole armoury of necromancy into requisition, and was rewarded at last by the discovery that the too highly-favoured swain was inevitably destined to end his days on the gallows—a discovery which, as has been already seen, fulfilled her most sanguine wishes.

Whatever may be the opinion of other and wiser people on the subject, in the parish of Ballycoursey or its vicinity it was rather an ugly joke to be thus devoted to the infernal gods by a prophetess of such unerring sagacity as Peggy Moran, or, as she was sometimes styled with reference to her skill in all supernatural matters, Peggy the Pishogue—that cognomen implying an acquaintance with more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in philosophy; and most unquestionably it was no misnomer: the priest himself was not more[Pg 139] deeply read in his breviary than was she in all the signs and omens whereby the affairs of this moving world are shadowed and foretokened—nothing was too great or too small for her all-piercing ken—in every form of augury she was omniscient, from cup-tossing up to necromancy—in vain the mystic dregs of the tea-cup assumed shapes that would have puzzled Doctor Wall himself: with her first glance she detected at once the true meaning of the hieroglyphic symbol, and therefrom dealt out deaths, births, and marriages, with the infallibility of a newspaper—in vain Destiny, unwilling to be unrolled, shrouded itself in some dream that would have bothered King Solomon. Peggy no sooner heard it than it was unravelled—there was not a ghost in the country with whose haunts and habits she was not as well acquainted as if she was one of the fraternity—not a fairy could put his nose out without being detected by her—the value of property was increased tenfold all round the country by the skill with which she wielded her charms and spells for the discovery of all manner of theft. But I must stop; for were I to recount but half her powers, the eulogium would require a Penny Journal for itself, and still leave matter for a supplement. It would be a melancholy instance indeed of Irish ingratitude if for all these superhuman exertions she was not rewarded by universal confidence. To the credit of the parish be it said that no such stigma was attached to it: nothing could equal the estimation in which all her words and actions were held by her neighbours—nothing but the estimation in which they were held in her own household by her husband and daughter.

Such being the gifted personage who had foretold the coming disasters of Mickey Brennan, it is not to be wondered at that the matter created a sensation, particularly as sundry old hags to whom she had imparted her discovery were requested to hush it up for the poor gossoon’s sake. His friends sorrowed over him as a gone man, for not the most sceptical among them ventured to hazard even a doubt of Peggy’s veracity—in fact, they viewed the whole as a matter requiring consolation and sympathy rather than as a scrutiny into the sources of her information, which by common consent were viewed as indubitable, while some, more compassionate than the rest, went so far as to declare “that since the thing could not be avoided, and Mickey, poor fellow, must be hanged, they hoped it might be for something dacint, not robbing, or coining, or the like.”

The hardest task of all is to describe the feelings of poor Brennan himself on the occasion; for much as he had affected to disparage the sybilline revelations of the wierd woman of Ballycoursey, there was not one in the neighbourhood who was more disposed to yield them unlimited credence in any case but his own; and even in his own case he was not long enabled to struggle against conviction. Let people prate as they may about education and its effects, it will require a period of more generations than one to root the love of the marvellous out of the hearts of our countrymen; and until that be effected, every village in the land will have its wise woman, and with nine-tenths of her neighbours what she says will be regarded as gospel. Some people of course will laugh to scorn such an assertion, and more will very respectfully beg leave to doubt it, but still it is true; and in the more retired inland villages circumstances are every day occurring far more extravagant than anything detailed in this story, as is very well known to all who are much conversant with such places. But to return to the doomed man:—How could he be expected to bear up against this terrible denunciation, when all the consolation he could receive from his nearest and dearest was that “it was a good man’s death?” Death! poor fellow, he had suffered the pains of a thousand deaths already, in living without the hope of ever being the husband of his Meny. Death, instant and immediate, would have been a relief to him; and it was not long until, by his anxiety to obtain that relief, he afforded an opportunity to Peggy of displaying her own reliance on the correctness of her prognostications. Goaded into madness by his present sufferings and his fears for the future, he made an attempt upon his life by plunging into an adjacent lake when no one, as he thought, was near to interrupt his intentions. It was not so, however—a shepherd had observed him, but at such a distance that before help could be obtained to rescue him he was to all appearance lifeless. The news flew like wildfire: he was dead, stone dead, they said—had lain in the water ten minutes, half an hour, half the day, since last night; but in one point they all concurred—dead he was; dead as St Dominick.

“Troth he’s not,” was Peggy’s cool rejoinder. “Be quiet, and I’ll engage he’ll come to. Nabocklish, he that’s born to be hanged will never be drowned. Wait a while an’ hould your tongues. Nabocklish, I tell you he’ll live to spoil a market yet, an’ more’s the pity.”

People shook their heads, and almost began to think their wise woman had made a mistake, and read hemp instead of water. It was no such thing, however: slowly and beyond all hopes, Brennan recovered the effects of his rash attempt, thereby fulfilling so much of his declared destiny, and raising the reputation of Mrs Moran to a point that she never had attained before. That very week she discovered no less than six cases of stolen goods, twice detected the good people taking unauthorised liberties with their neighbours’ churns, and spaed a score of fortunes, at the very least; and he, poor fellow, satisfied at last that Fortune was not to be bilked so easily, resigned himself to his fate like a man, and began to look about him in earnest for some opportunity of gracing the gallows without disgracing his people.

And Meny—poor heart-stricken Meny—loving as none but the true and simple-minded can love, the extent of her grief was such as the true and simple-minded only can know; and yet there was worse in store for her. Shortly after this consummation of her mother’s fame, a whisper began to creep through the village—a whisper of dire import, portending death and disaster on some luckless wight unknown—“Peggy Moran has something on her mind.” What could it be? Silent and mysterious she shook her head when any one ventured to question her—the pipe was never out of her jaw unless when she slept or sat down to her meals—she became as cross as a cat, which to do her justice was not her wont, and eschewed all sorts of conversation, which most assuredly was not her wont either. The interest and curiosity of her neighbours was raised to a most agonising pitch—every one trembled lest the result should be some terrible revelation affecting himself or herself, as the case might be: it was the burden of the first question asked in the morning, the last at night. Every word she uttered during the day was matter of speculation to an hundred anxious inquirers; and there was every danger of the good people of Ballycoursey going absolutely mad with fright if they were kept any longer in the dark on the subject.

At length there was a discovery; but, as is usually the case in all scrutinies into forbidden matters, it was at the cost of the too-daring investigator. Peggy and Brian were sitting one night before the fire, preparing for their retirement, when a notion seized the latter to probe the sorrows of his helpmate.

“’Deed it well becomes you to ax,” quoth the wierd woman in answer to his many and urgent inquiries; “for Brian, achorra machree, my poor ould man, there’s no use in hiding it—it’s all about yourself.”

“No, then!” exclaimed the surprised interrogator; “the Lord betune us an’ harm, is it?”

“’Deed yes, Brian,” responded the sybil with a melancholy tone, out of the cloud of smoke in which she had sought to hide her troubles. “I’m thinking these last few days you’re not yourself at all at all.”

“Tare an ounties! maybe I’m not,” responded he of the doubtful identity.

“Do you feel nothing on your heart, Brian achree?”

“I do; sure enough I do,” gasped poor Brian, ready to believe anything of himself.

“Something like a plurrisy, isn’t it?” inquired the mourner.

“Ay, sure enough, like a plurrisy for all the world, Lord betune us an’ harm!”

“An’ you do be very cold, I’ll engage, these nights, Brian?” continued she.

“Widdy Eelish! I’m as could as ice this minute,” answered Brian, and his teeth began to chatter as if he was up to his neck in a mill-pond.

“An’ your appetite is gone entirely, achra?” continued his tormentor.

“Sorra a word o’ lie in it,” answered the newly discovered invalid, forgetful however that he had just finished discussing a skib of potatoes and a mug of milk for his supper.

“And the cat, the crathur, looked at you this very night after licking her paw.”

“I’ll engage she did. Bad luck to her,” responded Brian, “I wouldn’t put it beyant her.”

“Let me feel your pulse, asthore,” said Peggy in conclusion; and Brian submitted his trembling wrist to her inspection, anxiously peering into her face all the while to read his doom therein. A long and deep sigh broke from her lips, along with a most voluminous puff of smoke, as she let the[Pg 140] limb drop from her hold, and commenced rocking herself to and fro, uttering a low and peculiar species of moan, which to her terrified patient sounded as a death summons.

“Murther-an’-ages, Peggy, sure it’s not going to die I am!” exclaimed Brian.

“Och, widdy! widdy!” roared the afflicted spouse, now giving full vent to her anguish, “it’s little I thought, Brian asthore machree, when I married you in your beauty and your prime, that I’d ever live to cry the keen over you—ochone, ochone! ’tis you was the good ould man in airnest—och! och!”

“Arrah, Peggy!” interposed the object of her rather premature lamentations.

“Oh, don’t talk to me—don’t talk to me. I’ll never hould up my head again, so I won’t!” continued the widow that was to be, in a tone that quickly brought all the house about her, and finally all the neighbours. Great was the uproar that ensued, and noisy the explanations, which, however, afforded no small relief to the minds of all persons not immediately concerned in the welfare of the doomed Brian. Peggy was inconsolable at the prospect of such a bereavement. Meny clung in despair to the poor tottering old man, her grief too deep for lamentation, while he hobbled over his prayers as fast and as correctly as his utter dismay would permit him. Next morning he was unable to rise, refused all nourishment, and called vehemently for the priest. Every hour he became worse; he was out of one faint into another; announced symptoms of every complaint that ever vexed mankind, and declared himself affected by a pain in every member, from his toe to his cranium. No wonder it was a case to puzzle the doctor. The man of science could make nothing of it—swore it was the oddest complication of diseases that ever he had heard of—and strongly recommended that the patient be tossed in a blanket, and his wife treated to a taste of the horse-pond. Father Coffey was equally nonplussed.

“What ails you, Brian?”

“An all-overness of some kind or other, your reverence,” groaned the sufferer in reply, and the priest had to own himself a bothered man. Nothing would induce him to rise—“where’s the use in a man’s gettin’ up, an’ he goin’ to die?” was his answer to those who endeavoured to rouse him—“isn’t it a dale dacinter to die in bed like a Christian?”

“God’s good!—maybe you won’t die this time, Brian.”

“Arrah, don’t be talking—doesn’t Peggy know best?” And with this undeniable assertion he closed all his arguments, receiving consolation from none, not even his heart-broken Meny. Despite of all his entreaties to be let die in peace, the doctor, who guessed how matters stood, was determined to try the effects of a blister, and accordingly applied one of more than ordinary strength, stoutly affirming that it would have the effect of the patient being up and walking on the morrow. A good many people had gathered into his cabin to witness the cure, as they always do when their presence could be best dispensed with; and to these Peggy, with tears and moans, was declaring her despair in all remedies whatever, and her firm conviction that a widow she’d be before Sunday, when Brian, roused a little by the uneasy stimulant from the lethargy into which they all believed him to be sunk, faintly expressed his wish to be heard.

“Peggy, agra,” said he, “there’s no denyin’ but you’re a wonderful woman entirely; an’ since I’m goin’, it would be a grate consolation to me if you’d tell us all now you found out the sickness was on me afore I knew it myself. It’s just curiosity, agra—I wouldn’t like to die, you see, without knowin’ for why an’ for what—it ’ud have a foolish look if any body axed me what I died of, an’ me not able to tell them.”

Peggy declared her willingness to do him this last favour, and, interrupted by an occasional sob, thus proceeded:—

“It was Thursday night week—troth I’ll never forget that night, Brian asthore, if I live to be as ould as Noah—an’ it was just after my first sleep that I fell draiming. I thought I went down to Dan Keefe’s to buy a taste ov mate, for ye all know he killed a bullsheen that day for the market ov Moneen; an’ I thought when I went into his house, what did I see hangin’ up but an ugly lane carcase, an’ not a bit too fresh neither, an’ a strange man dividin’ it with a hatchet; an’ says he to me with a mighty grum look,

“‘Well, honest woman, what do you want?—is it to buy bullsheen?’

“‘Yes,’ says I, ‘but not the likes of that—it’s not what we’re used to.’

“‘Divil may care,’ says he; ‘I’ll make bould to cut out a rib for you.’

“‘Oh, don’t if you plase,’ says I, puttin’ out my hand to stop him; an’ with that what does he do but he lifts the hatchet an’ makes a blow at my hand, an’ cuts the weddin’ ring in two on my finger?”

“Dth! dth! dth!” was ejaculated on all sides by her wondering auditory, for the application of the dream to Brian was conclusive, according to the popular method of explaining such matters. They looked round to see how he sustained the brunt of such a fatal revelation. There he was sitting bolt upright in the bed, notwithstanding his unpleasant incumbrance, his mouth and eyes wide open.

“Why, thin, blur-an’-ages, Peggy Moran,” he slowly exclaimed, when he and they had recovered a little from their surprise, “do you mane to tell me that’s all that ailed me?”

Peggy and her coterie started back as he uttered this extraordinary inquiry, there being something in his look that portended his intention to leap out of bed, and probably display his indignation a little too forcibly, for, quiet as he was, his temper wasn’t proof against a blister; but his bodily strength failed him in the attempt, and, roaring with pain, he resumed his recumbent position. But Peggy’s empire was over—the blister had done its business, and in a few days he was able to stump about as usual, threatening to inflict all sorts of punishments upon any one who dared to laugh at him. A laugh is a thing, however, not easy to be controlled, and finally poor Brian’s excellent temper was soured to such a degree by the ridicule which he encountered, that he determined to seek a reconciliation with young Brennan, pitch the decrees of fate to Old Nick, and give Father Coffey a job with the young couple.

To this resolution we are happy to say he adhered: still happier are we to say, that among the county records we have not yet met the name of his son-in-law, and that unless good behaviour and industry be declared crimes worthy of bringing their perpetrator to the gallows, there is very little chance indeed of Mickey Brennan fulfilling the prophecy of Peggy the Pishogue.

A. M’C.

Bustles!—what are bustles? Ay, reader, fair reader, you may well ask that question. But some of your sex at least know the meaning of the word, and the use of the article it designates, sufficiently well, though, thank heaven! there are many thousands of my countrywomen who are as yet ignorant of both, and indeed to whom such knowledge would be quite useless. Would that I were in equally innocent ignorance! Not, reader, that I am of the feminine gender, and use the article in question; but my knowledge of its mysterious uses, and the various materials of which it is composed, has been the ruin of me. I will have inscribed on my tomb, “Here lies a man who was killed by a bustle!”

But before I detail the circumstances of my unhappy fate, it will perhaps be proper to give a description of the article itself which has been the cause of my undoing. Well, then, a bustle is…

But the editor will perhaps object to this description as being too distinct and graphic. If so, then here goes for another less laboured and more characteristically mysterious.

A bustle is an article used by ladies to take from their form the character of the Venus of the Greeks, and impart to it that of the Venus of the Hottentots!

That ladies should have a taste so singular, may appear incredible; but there is no accounting for tastes, and I know to my cost that the fact is indisputable.

I made the discovery a few years since, and up to that time I had always borne the character of a sage, sedate, and promising young man—one likely to get on in the world by my exertions, and therefore sure to be helped by my friends. I was even, I flatter myself, a favourite with the fair sex too; and justly so, for I was their most ardent admirer; and there was one most lovely creature among them whom I had fondly hoped to have made my own. But, alas! how vain and visionary are our hopes of human happiness: such hopes with me have fled for ever! As I said before, I am a ruined man, and all in consequence of ladies’ bustles.

In an unlucky hour I was in a ball-room, seated at a little distance from my fair one—my eyes watching her every air and look, my ears catching every sound of her sweet voice—when I heard her complain to a female friend, in tones of the softest whispering music, that she was oppressed with the[Pg 141] heat of the place. “My dear,” her friend replied, “it must be the effect of your bustle. What do you stuff it with?” “Hair—horse-hair,” was the reply. “Hair!—mercy on us!” says her friend, “it is no wonder you are oppressed—that’s a hot-and-hot material truly. Why, you should do as I do—you do not see me fainting; and the reason is, that I stuff my bustle with hay—new hay!”

I heard no more, for the ladies, supposing from my eyes that I was a listener, changed the topic of conversation, though indeed it was not necessary, for at the time I had not the slightest notion of what they meant. Time, however, passed on most favourably to my wishes—another month, and I should have called my Catherine my own. She was on a visit to my sister, and I had every opportunity to make myself agreeable. We sang together, we talked together, and we danced together. All this would have been very well, but unfortunately we also walked together. It was on the last time we ever did so that the circumstance occurred which I have now to relate, and which gave the first death-blow to my hopes of happiness. We were crossing Carlisle-bridge, her dear arm linked in mine, when we chanced to meet a female friend; and wishing to have a little chat with her without incommoding the passengers, we got to the edge of the flag-way, near which at the time there was standing an old white horse, totally blind. He was a quiet-looking animal, and none of us could have supposed from his physiognomy that he had any savage propensity in his nature. But imagine my astonishment and horror when I suddenly heard my charmer give a scream that pierced me to the very heart!—and when I perceived that this atrocious old blind brute, having slowly and slyly swayed his head round, caught the—how shall I describe it?—caught my Catherine—really I can’t say how—but he caught her; and before I could extricate her from his jaws, he made a reef in her garments such as lady never suffered. Silk gown, petticoat, bustle—everything, in fact, gave way, and left an opening—a chasm—an exposure, that may perhaps be imagined, but cannot be described.[1]

As rapidly as I could, of course, I got my fair one into a jarvy, and hurried home, the truth gradually opening in my mind as to the cause of the disaster—it was, that the blind horse, hungry brute, had been attracted by the smell of my Catherine’s bustle, made of hay—new hay!

Catherine was never the same to me afterwards—she took the most invincible dislike to walk with me, or rather, perhaps, to be seen in the streets with me. But matters were not yet come to the worst, and I had indulged in hopes that she would yet be mine. I had however taken a deep aversion to bustles, and even determined to wage war upon them to the best of my ability. In this spirit, a few days after, I determined to wreak my vengeance on my sister’s bustle, for I found by this time that she too was emulous of being a Hottentot beauty. Accordingly, having to accompany her and my intended wife to a ball, I stole into my sister’s room in the course of the evening before she went into it to dress, and pouncing upon her hated bustle, which lay on her toilet table, I inflicted a cut on it with my penknife, and retired. But what a mistake did I make! Alas, it was not my sister’s bustle, but my Catherine’s! However, we went to the ball, and for a time all went smoothly on. I took out my Catherine as a partner in the dance; but imagine my horror when I perceived her gradually becoming thinner and thinner—losing her enbonpoint—as she danced; and, worse than that, that every movement which she described in the figure—the ladies’ chain, the chassee—was accurately marked—recorded—on the chalked floor with—bran! Oh dear! reader, pity me: was ever man so unfortunate? This sealed my doom. She would never speak to me, or even look at me afterwards.

But this was not all. My character with the sex—ay, with both sexes—was also destroyed. I who had been heretofore, as I said, considered as an example of prudence and discretion for a young man, was now set down as a thoughtless, devil-may-care wag, never to do well: the men treated me coldly, and the women turned their backs upon me; and so thus in reality they made me what they had supposed I was. It was indeed no wonder, for I could never after see a lady with a bustle but I felt an irresistible inclination to laughter, and this too even on occasions when I should have kept a grave countenance. If I met a couple of country or other friends in the street, and inquired after their family—the cause, perhaps, of the mourning in which they were attired—while they were telling me of the death of some father, sister, or other relative, I to their astonishment would take to laughing, and if there was a horse near us, give the lady a drag away to another situation. And if then I were asked the meaning of this ill-timed mirth, and this singular movement, what could I say? Why, sometimes I made the matter worse by replying, “Dear madam, it is only to save your bustle from the horse!”

Stung at length by my misfortunes and the hopelessness of my situation, I became utterly reckless, and only thought of carrying out my revenge on the bustles in every way in my power; and this I must say with some pride I did for a while with good effect. I got a number of the hated articles manufactured for myself, but not, reader, to wear, as you shall hear. Oh! no; but whenever I received an invitation to a party—which indeed had latterly been seldom sent me—I took one of these articles in my pocket, and, watching a favourable opportunity when all were engaged in the mazy figure of the dance, let it secretly fall amongst them. The result may be imagined—ay, reader, imagine it, for I cannot describe it with effect. First, the half-suppressed but simultaneous scream of all the ladies as it was held up for a claimant; next, the equally simultaneous movement of the ladies’ hands, all quickly disengaged from those of their partners, and not raised up in wonder, but carried down to their—bustles! Never was movement in the dance executed with such precision; and I should be immortalised as the inventor of an attitude so expressive of sentiment and of feeling.

Alas! this is the only consolation now afforded me in my afflictions: I invented a new attitude—a new movement in the quadrille: let others see that it be not forgotten. I am now a banished man from all refined society: no lady will appear, where that odious Mr Bustle, as they call me, might possibly be; and so no one will admit me inside their doors. I have nothing left me, therefore, but to live out my solitary life, and vent my execration of bustles in the only place now left me—the columns of the Irish Penny Journal.

[1] A fact.

The otter varies in size, some adult specimens measuring no more than thirty-six inches in length, tail inclusive, while others, again, are to be found from four and a half to five feet long. The head of the otter is broad and flat; its muzzle is broad, rounded, and blunt; its eyes small and of a semi-circular form; neck extremely thick, nearly as thick as the body; body long, rounded, and very flexible; legs short and muscular; feet furnished with five sharp-clawed toes, webbed to three-quarters of their extent; tail long, muscular, somewhat flattened, and tapering to its extremity. The colour of the otter is a deep blackish brown; the sides of the head, the front of the neck, and sometimes the breast, brownish grey. The belly is usually, but not invariably, darker than the back; the fur is short, and of two kinds; the inferior or woolly coat is exceedingly fine and close; the longer hairs are soft and glossy, those on the tail rather stiff and bristly. On either side of the nose, and just below the chin, are two small light-coloured spots. So much for the appearance of the otter: now we come to its dwelling. The otter is common to England, Ireland, and Scotland; a marine variety is also to be met with, differing from the common only in its superior size and more furry coat. Some naturalists have set them down as a different species: I am, however, disposed to regard them as a variety merely.

The native haunt of the otter is the river-bank, where amongst the reeds and sedge it forms a deep burrow, in which it brings forth and rears its young. Its principal food is fish, which it catches with singular dexterity. It lives almost wholly in the water, and seldom leaves it except to devour its prey; on land it does not usually remain long at any one time, and the slightest alarm is sufficient to cause it to plunge into the stream. Yet, natural as seems a watery residence to this creature, its hole is perfectly dry; were it to become otherwise, it would be quickly abandoned. Its entrance, indeed, is invariably under water, but its course then points upwards into the bank, towards the surface of the earth, and it is even provided with several lodges or apartments at different heights, into which it may retire in case of floods, throwing up the earth behind it as it proceeds into the recesses[Pg 142] of its retreat; and when it has reached the last and most secure chamber, it opens a small hole in the roof for the admission of atmospheric air, without which the animal could not of course exist many minutes; and should the flood rise so high as to burst into this last place of refuge, the animal will open a passage through the roof, and venture forth upon land, rather than remain in a damp and muddy bed. During severe floods, otters are not unfrequently surprised at some distance from the water, and taken.

In a wild state the otter is fierce and daring, will make a determined resistance when attacked by dogs, and being endued with no inconsiderable strength of jaw, it often punishes its assailants terribly. I have myself seen it break the fore-leg of a stout terrier. Otter-hunting was in former times a favourite amusement even with the nobility, and regular establishments of otter-hounds were kept. The animal is now become scarce, and its pursuit is no longer numbered in our list of sports, unless perhaps in Scotland, where, especially in the Western Islands, otter-hunting is still extensively practised.

Otters are easily rendered tame, especially if taken young, and may be taught to follow their master like dogs, and even to fish for him, cheerfully resigning their prey when taken, and dashing into the water in search of more. A man named James Campbell, residing near Inverness, had one which followed him wherever he went, unless confined, and would answer to its name. When apprehensive of danger from dogs, it sought the protection of its master, and would endeavour to spring into his arms for greater security. It was frequently employed in catching fish, and would sometimes take eight or ten salmon in a day. If not prevented, it always attempted to break the fish behind the fin which is next the tail; and as soon as one was taken away, it always dived in pursuit of more. It was equally dexterous at sea-fishing, and took great numbers of young cod and other fish. When tired it would refuse to fish any longer, and was then rewarded with as much food as it could devour. Having satiated its appetite, it always coiled itself up and went to sleep, no matter where it was, in which state it was usually carried home.

Brown relates that a person who kept a tame otter taught it to associate with his dogs, who were on the most friendly terms with it on all occasions, and that it would follow its master in company with its canine friends. This person was in the habit of fishing the river with nets, on which occasions the otter proved highly useful to him, by going into the water and driving trout and other fish towards the net. It was very remarkable that dogs accustomed to otter-hunting were so far from offering it the least molestation, that they would not even hunt any other otter while it remained with them; on which account its owner was forced to part with it.

The otter is of a most affectionate disposition, as may at once be seen from its anxiety respecting its young. Indeed, the parental affection of this creature is so powerful that the female otter will often suffer herself to be killed rather than desert them. Professor Steller says, “Often have I spared the lives of the female otters whose young ones I took away. They expressed their sorrow by crying like human beings, and following me as I was carrying off their young, while they called to them for aid with a tone of voice which very much resembled the crying of children. When I sat down in the snow, they came quite close to me, and attempted to carry off their young. On one occasion when I had deprived an otter of her progeny, I returned to the place eight days after, and found the female sitting by the river listless and desponding, who suffered me to kill her on the spot without making any attempt to escape. On skinning her I found she was quite wasted away from sorrow for the loss of her young.” This affection which the otter, while in a state of nature, displays towards her young, is when in captivity usually transferred to her master, or perhaps, as in an instance I shall mention by and bye, to some one or other of his domestic animals. As an example of the former case I may mention the following:—A person named Collins, who lived near Wooler in Northumberland, had a tame otter, which followed him wherever he went. He frequently took it to the river to fish for its own food, and when satisfied it never failed to return to its master. One day in the absence of Collins, the otter being taken out to fish by his son, instead of returning as usual, refused to answer to the accustomed call, and was lost. Collins tried every means to recover it; and after several days’ search, being near the place where his son had lost it, and calling its name, to his very great joy the animal came crawling to his feet. In the following passage of the “Prædium Rusticum” of Vaniere, allusion is made to tame otters employed in fishing:—

Mr Macgillivray, in his interesting volume on British Quadrupeds in the Naturalist’s Library, mentions several instances of otters having been tamed and employed in fishing. Among others he relates that a gentleman residing in the Outer Hebrides had one that supplied itself with food, and regularly returned to the house. M’Diarmid, in his “Sketches from Nature,” enumerates many others. One otter belonging to a poor widow, “when led forth plunged into the Urr, and brought out all the fish it could find.” Another, kept at Corsbie House, Wigtonshire, “evinced a great fondness for gooseberries,” fondled “about her keeper’s feet like a pup or kitten, and even seemed inclined to salute her cheek, when permitted to carry her freedoms so far.” A third, belonging to Mr Montieth of Carstairs, “though he frequently stole away at night to fish by the pale light of the moon, and associate with his kindred by the river side, his master of course was too generous to find any fault with his peculiar mode of spending his evening hours. In the morning he was always at his post in the kennel, and no animal understood better the secret of ‘keeping his own side of the house.’ Indeed his pugnacity in this respect gave him a great lift in the favour of the gamekeeper, who talked of his feats wherever he went, and averred besides, that if the best cur that ever ran ‘only daured to girn’ at his protegé, he would soon ‘mak his teeth meet through him.’ To mankind, however, he was much more civil, and allowed himself to be gently lifted by the tail, though he objected to any interference with his snout, which is probably with him the seat of honour.”

Mr Glennon, of Suffolk-street, Dublin, informs me that Mr Murray, gamekeeper to his Grace the Duke of Leinster, has a tame otter, which enters the water to fish when desired, and lays whatever he catches with due submission at his master’s feet. Mr Glennon further observes, that the affection for his owner which this animal exhibits is equal or even superior to that of the most faithful dog. The creature follows him wherever he goes, will suffer him to lift him up by the tail and carry him under his arm just as good-humouredly as would a dog, will spring to his knee when he sits at home, and seems in fact never happy but when in his company. This otter is well able to take care of himself, and fearlessly repels the impertinent advances of the dogs: with such, however, as treat him with fitting respect, he is on excellent terms. Sometimes Mr Murray will hide himself from this animal, which will immediately, on being set at liberty, search for him with the greatest anxiety, running like a terrier dog by the scent. Mr Glennon assures me that he has frequently seen the animal thus trace the footsteps of its master for a considerable distance across several fields, and that too with such precision as never in any instance to fail of finding him.

I myself had once a tame otter, with a detail of whose habits and manners I shall now conclude this article. When I first obtained the animal she was very young, and not more than sixteen inches in length: young as she was, she was very fierce, and would bite viciously if any one put his hand near the nest of straw in which she was kept. As she grew a little older, however, she became more familiarized to the approaches of human beings, and would suffer herself to be gently stroked upon the back or head; when tired of being caressed, she would growl in a peculiar manner, and presently use her sharp teeth if the warning to let her alone were not attended to. In one respect the manners of this animal presented a striking contrast to the accounts I had read and heard of other tame individuals. She evinced no particular affection for me; she grew tame certainly, but her tameness was rather of a general than of an exclusive character: unlike other wild animals which I had at different times succeeded in domesticating, this creature testified no particular gratitude to her master, and whoever fed her, or set her at liberty, was her favourite for the time being. She preferred fish to any other diet, and eagerly devoured all descriptions, whether taken in fresh or salt water, though she certainly preferred the former. She would seize the fish between her fore paws, hold it firmly on the[Pg 143] ground, and devour it downwards to the tail, which with the head the dainty animal rejected. When fish could not be procured, she would eat, but sparingly, of bread and milk, as well as the lean of raw meat; fat she could on no account be prevailed upon to touch.

Towards other animals my otter for a long period maintained an appearance of perfect indifference. If a dog approached her suddenly, she would utter a sharp, whistling noise, and betake herself to some place of safety: if pursued, she would turn and show fight. If the dog exhibited no symptoms of hostility, she would presently return to her place at the fireside, where she would lie basking for hours at a time.

When I first obtained this animal, there was no water sufficiently near to where I lived in which I could give her an occasional bath; and being apprehensive, that, if entirely deprived of an element in which nature had designed her to pass so considerable a portion of her existence, she would languish and die, I allowed her a tub as a substitute for her native river; and in this she plunged and swam with much apparent delight. It was in this manner that I became acquainted with the curious fact, that the otter, when passing along beneath the surface of the water, does not usually accomplish its object by swimming, but by walking along the bottom, which it can do as securely and with as much rapidity as it can run on dry land.

After having had my otter about a year, I changed my residence to another quarter of the town, and the stream well known to all who have seen Edinburgh as the “Water of Leith,” flowed past the rear of the house. The creature being by this time so tame as to be allowed perfect liberty, I took it down one evening to the river, and permitted it to disport itself for the first time since its capture in a deep and open stream. The animal was delighted with the new and refreshing enjoyment, and I found that a daily swim in the river greatly conduced to its health and happiness. I would sometimes walk for nearly a mile along the bank, and the happy and frolicsome creature would accompany me by water, and that too so rapidly that I could not even by very smart walking keep pace with it. On some occasions it caught small fish, such as minnows, eels, and occasionally a trout of inconsiderable size. When it was only a minnow or a small eel which it caught, it would devour it in the water, putting its head for that purpose above the surface; when, however, it had made a trout its prey, it would come to shore, and devour it more at leisure. I strove very assiduously to train this otter to fish for me, as I had heard they have sometimes been taught to do; but I never could succeed in this attempt, nor could I even prevail upon the animal to give me up at any time the fish which she had taken: the moment I approached her to do so, as if suspecting my intention, she would at once take to the water, and, crossing to the other side of the stream, devour her prey in security. This difficulty in training I impute to the animal’s want of an individual affection for me, for it was not affection, but her own pleasure, which induced her to follow me down the stream; and she would with equal willingness follow any other person who happened to release her from her box. This absence of affection was probably nothing more than peculiarity of disposition in this individual, there being numerous instances of a contrary nature upon record.

Although this otter failed to exhibit those affectionate traits of character which have displayed themselves in other individuals of her tribe towards the human species, she was by no means of a cold or unsocial disposition towards some of my smaller domestic animals. With an Angora cat she soon after I got her formed a very close friendship, and when in the house was unhappy when not in the company of her friend. I had one day an opportunity of witnessing a singular display of attachment on the part of this otter towards the cat:—A little terrier dog attacked the latter as she lay by the fire, and driving her thence, pursued her under the table, where she stood on her defence, spitting and setting up her back in defiance: at this instant the otter entered the apartment, and no sooner did she perceive what was going on, than she flew with much fury and bitterness upon the dog, seized him by the face with her teeth, and would doubtless have inflicted a severe chastisement upon him, had I not hastened to the rescue, and, separating the combatants, expelled the terrier from the room.

When permitted to wander in the garden, this otter would search for grubs, worms, and snails, which she would eat with much apparent relish, detaching the latter from their shell with surprising quickness and dexterity. She would likewise mount upon the chairs at the window, and catch and eat flies—a practice which I have not as yet seen recorded in the natural history of this animal. I had this otter in my possession nearly two years, and have in the above sketch mentioned only a few of its most striking peculiarities. Did I not fear encroaching on space which is perhaps the property of another contributor, I could have carried its history to a much greater length.

H. D. R.

There reached our city, on the morning of the 29th day of July, and sailed from it on the night of the 31st, the most remarkable person perhaps by whom our shores have been lately visited. Were we to second our own feelings, we would apply a higher epithet to William Lloyd Garrison, but we have chosen one in which we are persuaded all parties would agree who partook of his intercourse, however much they may differ from each other and from him in principle and in practice. The object of this short paper is to leave on the pages of our literature some record of an extraordinary individual, who is a literary man himself, being the editor and proprietor of a successful newspaper published at Boston in Massachusetts; but his name may be best recommended to our readers in connection with that of the well-known George Thompson, whose eloquence was so powerful an auxiliary to the unnumbered petitions which at length wrung from our legislature the just but expensive emancipation of the West Indian negroes. Community of action and of suffering, as pleaders for the rights of the black and coloured population of the United States, has rendered them bosom friends, and each has a child called after the name of the other. Thompson is now a denizen of the United Kingdom; but while we write, Garrison is crossing the broad Atlantic to encounter new dangers: comparatively safe at home, his life is forfeited whenever he ventures to pass the moral line of demarcation which separates the free from the slave states—forfeited so surely as there is a rifle in Kentucky or a bowie knife in Alabama.

We have set Garrison down as “an American nobleman,” and the “peerage” in which we look for his titles and dignities is “The Martyr Age of the United States of America,” by Harriet Martineau—a writer to whom none will deny the possession of discrimination, which is all we contend for. “William Lloyd Garrison is one of God’s nobility—the head of the moral aristocracy, whose prerogatives we are contemplating. It is not only that he is invulnerable to injury—that he early got the world under his feet in a way which it would have made Zeno stroke his beard with a complacency to witness; but that in his meekness, his sympathies, his self-forgetfulness, he appears ‘covered all over with the stars and orders’ of the spiritual realm whence he derives his dignities and his powers. At present he is a marked man wherever he turns. The faces of his friends brighten when his step is heard: the people of colour almost kneel to him; and the rest of society jeers, pelts, and execrates him. Amidst all this, his gladsome life rolls on, ‘too busy to be anxious, and too loving to be sad.’ He springs from his bed singing at sunrise: and if during the day tears should cloud his serenity, they are never shed for himself. His countenance of steady compassion gives hope to the oppressed, who look to him as the Jews looked to Moses. It was this serene countenance, saint-like in its earnestness and purity, that a man bought at a print-shop, where it was exposed without a name, and hung up as the most apostolic face he ever saw. It does not alter the case that the man took it out of the frame, and hid it when he found that it was Garrison who had been adorning his parlour.” And he can be no common man of whom it is recorded in the work to which we have already alluded, that, on starting a newspaper for the advocacy of abolition principles, “Garrison and his friend Knapp, a printer, were ere long living in a garret, on bread and water, expending all their spare earnings and time on the publication, and that when it sold particularly well (says Knapp), we treated ourselves with a bowl of milk.”—The Martyr Age of the United States of America, p. 5.

As we are not writing his memoir, we refer such of our readers as may be curious to inquire further into the subject to the pamphlet just cited, and to the chapter headed “Garrison,” in the work on America by the same writer. To one extraordinary feature of his character, however, we cannot forbear adverting. He belongs to a society instituted for the[Pg 144] apparently negative purpose of non-resistance, and is therefore the safest of all antagonists. Buffet as you list the head and sides of W. L. Garrison, and you receive no buffet in return. That this is owing to no deficiency of personal courage, admits of demonstration. Neither the prison into which he was cast when a mere lad in one state, the price set on his head in another, nor the tar-kettle to which he would on one occasion have been dragged but for a stout arm that came to his rescue, has been able to make Garrison swerve from what he considers to be his line of duty. Another cause of this disposition to passive endurance must be sought, and it is easily found: he is in love—deeply in love with all mankind. His principle is to “resist not evil;” and he acts upon it to the fullest extent. In fact, he appears to be several centuries in advance of his time, and to live in a millennium of his own creating.

We shall only add, that the effect which this remarkable man produced on the minds of those who companied with him while in Dublin, was of a very peculiar nature. Among these were persons of various sects and parties, and of all varieties of temperament, but nearly all seemed to concur in their estimate of his character. Though many seemed to think that he carried out the great principle of love to an unnecessary extent, none seemed able to gainsay his reasonings. Here and there tears were seen to start, not called forth by any sublime sentiment or tender emotion to which he had given words at the moment, but educed as it were by the abstract contemplation of the image of intense virtue which he represented; and most agreed in the opinion, that of all individuals with whom they had ever been acquainted, he was the one of whom it could be with most justice asserted, that none could hold much intercourse with him without becoming better. His Dublin host sailed to Liverpool on Monday evening for the mere purpose of enjoying his company for three hours more, which was all the arrangements the Boston steamer would permit, in which he was to leave Liverpool on Tuesday.

It would be an act of great injustice to close this article without making some mention of Garrison’s congenial friend and companion Nathaniel Peabody Rogers of Plymouth, in New Hampshire, also the editor and proprietor of a newspaper, of whom, however, we shall only say, that if (as the phrase goes) anything happened to W. L. Garrison, he is the man who would be ready to occupy his place in the admiration and execration of America.

G. D.

Time.—Time is the most undefinable yet most paradoxical of things: the past is gone, the future is not come, and the present becomes the past even while we attempt to define it, and, like the flash of the lightning, at once exists and expires. Time is the measure of all things, but is itself immeasurable, and the grand discloser of all things, but is itself undisclosed. Like space, it is incomprehensible, because it has no limit, and it would be still more so, if it had. It is more in its source than the Nile, and its termination, than the Niger; and advances like the slowest tide, but retreats like the swiftest torrent. It gives wings of lightning to pleasure, but feet of lead to pain, and lends expectation a curb, but enjoyment a spur. It robs beauty of her charms, to bestow them on her picture, and builds a monument to merit, but denies it a house; it is the transient and deceitful flatterer of falsehood, but the tried and final friend of truth. Time is the most subtle, yet the most insatiable of depredators, and by appearing to take nothing, is permitted to take all, nor can it be satisfied until it has stolen the world from us, and us from the world. It constantly flies, yet overcomes all things by flight; and although it is the present ally, it will be the future conqueror of death. Time, the cradle of hope, but the grave of ambition, is the stern corrector of fools, but the salutary counsellor of the wise, bringing all they dread to the one, and all they desire to the other; like Cassandra, it warns us with a voice that even the sages discredit too long, and the silliest believe too late. Wisdom walks before it, opportunity with it, and repentance behind it; he that has made it his friend, will have little to fear from his enemies; but he that has made it his enemy, will have little to hope from his friends.—Burn’s Youthful Piety.

Diffidence.—A man gets along faster with a sensible married woman in hours than with a young girl in whole days. It is next to impossible to make them talk, or to reach them. They are like a green walnut: there are half a dozen outer coats to be pulled off, one by one and slowly, before you reach the kernel of their characters.

Printed and published every Saturday by GUNN and CAMERON, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin, and sold by all Booksellers.