The Project Gutenberg EBook of Mark the Match Boy, by Horatio Alger Jr.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Mark the Match Boy

or Richard Hunter's Ward

Author: Horatio Alger Jr.

Release Date: September 17, 2016 [EBook #53071]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MARK THE MATCH BOY ***

Produced by David Edwards, Brian Wilsden and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Other Volumes in Preparation.

"Mark, the Match Boy," is the third volume of the "Ragged Dick Series," and, like its predecessors, aims to describe a special phase of street life in New York. While it is complete in itself, several characters are introduced who have figured conspicuously in the preceding volumes; and the curiosity as to their future history, which has been expressed by many young readers, will be found to be gratified in the present volume.

The author has observed with pleasure the increased public attention which has been drawn to the condition of these little waifs of city life, by articles in our leading magazines, and in other ways; and hopes that the result will be to strengthen and assist the philanthropic efforts which are making to rescue them from their vagabond condition, and [viii] train them up to be useful members of society. That his own efforts have been received with so large a measure of public favor, not limited to the young readers for whom the series is especially written, the author desires to express his grateful thanks.

New York, April, 1869.

RICHARD HUNTER AT HOME.

"Fosdick," said Richard Hunter, "what was the name of that man who owed your father two thousand dollars, which he never paid him?"

"Hiram Bates," answered Fosdick, in some surprise. "What made you think of him?"

"I thought I remembered the name. He moved out West, didn't he?"

"So I heard at the time."

"Do you happen to remember where? Out West is a very large place."

"I do not know exactly, but I think it was Milwaukie."

"Indeed!" exclaimed Richard Hunter, in visible [10] excitement. "Well, Fosdick, why don't you try to get the debt paid?"

"Of what use would it be? How do I know he is living in Milkwaukie now? If I should write him a letter, there isn't much chance of my ever getting an answer."

"Call and see him."

"What, go out to Milwaukie on such a wild-goose chase as that? I can't think what you are driving at, Dick."

"Then I'll tell you, Fosdick. Hiram Bates is now in New York."

"How do you know?" asked Fosdick, with an expression of mingled amazement and incredulity.

"I'll show you."

Richard Hunter pointed to the list of hotel arrivals in the "Evening Express," which he held in his hand. Among the arrivals at the Astor House occurred the name of Hiram Bates, from Milwaukie.

"If I am not mistaken," he said, "that is the name of your father's debtor."

"I don't know but you are right," said Fosdick, thoughtfully.

"He must be prosperous if he stops at a high-priced hotel like the Astor."

"Yes, I suppose so. How much good that money would have done my poor father," he added, with a sigh.

"How much good it will do you, Fosdick."

Fosdick shook his head. "I would sell out my chance of getting it for ten dollars," he said.

"I would buy it at that price if I wanted to make money out of you; but I don't. I advise you to attend to this matter at once."

"What can I do?" asked Fosdick, who seemed at a loss to understand his companion's meaning.

"There is only one thing to do," said Dick, promptly. "Call on Mr. Bates this evening at the hotel. Tell him who you are, and hint that you should like the money."

"I haven't got your confidence, Dick. I shouldn't know how to go about it. Do you really think it would do any good? He might think I was impertinent."

"Impertinent to ask payment of a just debt! I don't see it in that light. I think I shall have to go with you."

"I wish you would,—that is, if you really think there is any use in going."

"You mustn't be so bashful if you want to get on in the world, Fosdick. As long as there's a chance of getting even a part of it, I advise you to make the attempt."

"Well, Dick, I'll be guided by your advice."

"Two thousand dollars would be a pretty good windfall for you."

"That's true enough, considering that I only get eight dollars a week."

"I wish you got more."

"So do I, for one particular reason."

"What is that?"

"I don't feel satisfied to have you pay ten dollars a week towards our board, while I pay only six."

"Didn't you promise not to say anything more about that?" said Dick, reproachfully.

"But I can't help thinking about it. If we had stayed at our old boarding-house in Bleecker Street, I could have paid my full share."

"But this is a nicer room."

"Much nicer. If I only paid my half, I should be glad of the chance."

"Well, I'll promise you one thing. If Mr. Bates pays you the two thousand dollars, you may pay your half of the expense."

"Not much chance of that, Dick."

"We can tell better after calling at the Astor House. Get on your coat and we'll start."

While the boys,—for the elder of the two is but eighteen—are making preparations to go out, a few explanations may be required by the reader. Those who have read "Ragged Dick" and "Fame and Fortune,"—the preceding volumes of this series,—will understand that less than three years before Richard Hunter was an ignorant and ragged boot-black about the streets, and Fosdick, though possessing a better education, was in the same business. By a series of upward steps, partly due to good fortune, but largely to his own determination to improve, and hopeful energy, Dick had now become a book-keeper in the establishment of Rockwell & Cooper, on Pearl Street, and possessed the confidence and good wishes of the firm in a high degree.

Fosdick was two years younger, and, though an excellent boy, was less confident, and not so well fitted as his friend to contend with the difficulties of [14] life, and fight his way upward. He was employed in Henderson's hat and cap store on Broadway, and was at present earning a salary of eight dollars a week. As the two paid sixteen dollars weekly for their board, Fosdick would have had nothing left if he had paid his full share. But Richard Hunter at first insisted on paying eleven dollars out of the sixteen, leaving his friend but five to pay. To this Fosdick would not agree, and was with difficulty prevailed upon at last to allow Richard to pay ten; but he had always felt a delicacy about this, although he well knew how gladly his friend did it.

The room which they now occupied was situated in St. Mark's Place, which forms the eastern portion of Eighth Street. It was a front room on the third floor, and was handsomely furnished. There was a thick carpet, of tasteful figure, on the floor. Between the two front windows was a handsome bureau, surmounted by a large mirror. There was a comfortable sofa, chairs covered with hair-cloth, a centre-table covered with books, crimson curtains, which gave a warm and cosey look to the room when lighted up in the evening, and all the accessories of a well-furnished room which is used at the same [15] time as parlor and chamber. This, with an excellent table, afforded a very agreeable home to the boys,—a home which, in these days, would cost considerably more, but for which, at the time of which I write, sixteen dollars was a fair price.

It may be thought that, considering how recently Richard Hunter had been a ragged boot-black, content to sleep in boxes and sheltered doorways, and live at the cheapest restaurants, he had become very luxurious in his tastes. Why did he not get a cheaper boarding-place, and save up the difference in price? No doubt this consideration will readily suggest itself to the minds of some of my young readers.

As Richard Hunter had a philosophy of his own on this subject, I may as well explain it here. He had observed that those young men who out of economy contented themselves with small and cheerless rooms, in which there was no provision for a fire, were driven in the evening to the streets, theatres, and hotels, for the comfort which they could not find at home. Here they felt obliged to spend money to an extent of which they probably were not themselves fully aware; and in the end wasted considerably [16] more than the two or three dollars a week extra which would have provided them with a comfortable home. But this was not all. In the roamings spent outside many laid the foundation of wrong habits, which eventually led to ruin or shortened their lives. They lost all the chances of improvement which they might have secured by study at home in the long winter evenings, and which in the end might have qualified them for posts of higher responsibility, and with a larger compensation.

Richard Hunter was ambitious. He wanted to rise to an honorable place in the community, and he meant to earn it by hard study. So Fosdick and he were in the habit of spending a portion of every evening in improving reading or study. Occasionally he went to some place of amusement, but he enjoyed thoroughly the many evenings when, before a cheerful fire, with books in their hands, his room-mate and himself were adding to their stock of knowledge. The boys had for over a year taken lessons in French and mathematics, and were now able to read the French language with considerable ease.

"What's the use of moping every evening in your [17] room?" asked a young clerk who occupied a hall bedroom adjoining.

"I don't call it moping. I enjoy it," was the reply.

"You don't go to a place of amusement once a month."

"I go as often as I like."

"Well, you're a queer chap. You pay such a thundering price for board. You could go to the theatre four times a week without its costing you any more, if you would take a room like mine."

"I know it; but I'd rather have a nice, comfortable room to come home to."

"Are you studying for a college professor?" asked the other, with a sneer.

"I don't know," said Dick, good-humoredly; "but I'm open to proposals, as the oyster remarked. If you know any first-class institution that would like a dignified professor, of extensive acquirements, just mention me, will you?"

So Richard Hunter kept on his way, indifferent to the criticisms which his conduct excited in the minds of young men of his own age. He looked farther than they, and knew that if he wanted to succeed in [18] life, and win the respect of his fellow-men, he must do something else than attend theatres, and spend his evenings in billiard saloons. Fosdick, who was a quiet, studious boy, fully agreed with his friend in his views of life, and by his companionship did much to strengthen and confirm Richard in his resolution. He was less ambitious than Dick, and perhaps loved study more for its own sake.

With these explanations we shall now be able to start fairly in our story.

AT THE ASTOR HOUSE.

The two friends started from their room about seven o'clock, and walked up to Third Avenue, where they jumped on board a horse-car, and within half an hour were landed at the foot of the City Hall Park, opposite Beekman Street. From this point it was necessary only to cross the street to the Astor House.

The Astor House is a massive pile of gray stone, and has a solid look, as if it might stand for hundreds of years. When it was first erected, a little more than thirty years since, it was considered far up town, but now it is far down town, so rapid has been the growth of the city.

Richard Hunter ascended the stone steps with a firm step, but Henry Fosdick lingered behind.

"Do you think we had better go up, Dick?" he said irresolutely.

"Why not?"

"I feel awkward about it."

"There is no reason why you should. The money belongs to you rightfully, as the representative of your father, and it is worth trying for."

"I suppose you are right, but I shan't know what to say."

"I'll help you along if I find you need it. Come along."

Those who possess energy and a strong will generally gain their point, and it was so with Richard Hunter. They entered the hotel, and, ascending some stone steps, found themselves on the main floor, where the reading-room, clerk's office, and dining-room are located.

Dick, to adopt the familiar name by which his companion addressed him, stepped up to the desk, and drew towards him the book of arrivals. After a brief search he found the name of "Hiram Bates, Milwaukie, Wis.," towards the top of the left-hand page.

"Is Mr. Bates in?" he inquired of the clerk, pointing to the name.

"I will send and inquire, if you will write your name on this card."

Dick thought it would be best to send his own name, as that of Fosdick might lead Mr. Bates to guess the business on which they had come.

He accordingly wrote the name,

in his handsomest handwriting, and handed it to the clerk.

That functionary touched a bell. The summons was answered by a servant.

"James, go to No. 147, and see if Mr. Bates is in. If he is, give him this card."

The messenger departed at once, and returned quickly.

"The gentleman is in, and would be glad to have Mr. Hunter walk up."

"Come along, Fosdick," said Dick, in a low voice.

Fosdick obeyed, feeling very nervous. Following the servant upstairs, they soon stood before No. 147.

James knocked.

"Come in," was heard from the inside, and the two friends entered.

They found themselves in a comfortably furnished room. A man of fifty-five, rather stout in build, and with iron-gray hair, rose from his chair before the fire, and looked rather inquiringly. He seemed rather surprised to find that there were two visitors, as well as at the evident youth of both.

"Mr. Hunter?" he said, inquiringly, looking from one to the other.

"That is my name," said Dick, promptly.

"Have I met you before? If so, my memory is at fault."

"No, sir, we have never met."

"I presume you have business with me. Be seated, if you please."

"First," said Dick, "let me introduce my friend Henry Fosdick."

"Fosdick!" repeated Hiram Bates, with a slight tinge of color.

"I think you knew my father," said Fosdick, nervously.

"Your father was a printer,—was he not?" inquired Mr. Bates.

"Yes, sir."

"I do remember him. Do you come from him?"

Fosdick shook his head.

"He has been dead for two years," he said, sadly.

"Dead!" repeated Hiram Bates, as if shocked. "Indeed, I am sorry to hear it."

He spoke with evident regret, and Henry Fosdick, whose feelings towards his father's debtor had not been very friendly, noticed this, and was softened by it.

"Did he die in poverty, may I ask?" inquired Mr. Bates, after a pause.

"He was poor," said Fosdick; "that is, he had nothing laid up; but his wages were enough to support him and myself comfortably."

"Did he have any other family?"

"No, sir; my mother died six years since, and I had no brothers or sisters."

"He left no property then?"

"No, sir."

"Then I suppose he was able to make no provision for you?"

"No, sir."

"But you probably had some relatives who came forward and provided for you?"

"No, sir; I had no relatives in New York."

"What then did you do? Excuse my questions, but I have a motive in asking."

"My father died suddenly, having fallen from a Brooklyn ferry-boat and drowned. He left nothing, and I knew of nothing better to do than to go into the streets as a boot-black."

"Surely you are not in that business now?" said Mr. Bates, glancing at Fosdick's neat dress.

"No, sir; I was fortunate enough to find a friend,"—here Fosdick glanced at Dick,—"who helped me along, and encouraged me to apply for a place in a Broadway store. I have been there now for a year and a half."

"What wages do you get? Excuse my curiosity, but your story interests me."

"Eight dollars a week."

"And do you find you can live comfortably on that?"

"Yes, sir; that is, with the assistance of my friend here."

"I am glad you have a friend who is able and willing to help you."

"It is not worth mentioning," said Dick, modestly. "I have received as much help from him as he has from me."

"I see at any rate that you are good friends, and a good friend is worth having. May I ask, Mr. Fosdick, whether you ever heard your father refer to me in any way?"

"Yes, sir."

"You are aware, then, that there were some money arrangements between us?"

"I have heard him say that you had two thousand dollars of his, but that you failed, and that it was lost."

"He informed you rightly. I will tell you the particulars, if you are not already aware of them."

"I should be very glad to hear them, sir. My father died so suddenly that I never knew anything more than that you owed him two thousand dollars."

"Five years since," commenced Mr. Bates, "I was a broker in Wall Street. As from my business [26] I was expected to know the best investments, some persons brought me money to keep for them, and I either agreed to pay them a certain rate of interest, or gave them an interest in my speculations. Among the persons was your father. The way in which I got acquainted with him was this: Having occasion to get some prospectuses of a new company printed, I went to the office with which he was connected. There was some error in the printing, and he was sent to my office to speak with me about it. When our business was concluded, he waited a moment, and then said, 'Mr. Bates, I have saved up two thousand dollars in the last ten years, but I don't know much about investments, and I should consider it a favor if you would advise me.'

"'I will do so with pleasure,' I said. 'If you desire it I will take charge of it for you, and either allow you six per cent, interest, or give you a share of the profits I may make from investing it.'"

"Your father said that he should be glad to have me take the money for him, but he would prefer regular interest to uncertain profits. The next day he brought the money, and put it in my hands. To [27] confess the truth I was glad to have him do so, for I was engaged in extensive speculations, and thought I could make use of it to advantage. For a year I paid him the interest regularly. Then there came a great catastrophe, and I found my brilliant speculations were but bubbles, which broke and left me but a mere pittance, instead of the hundred thousand dollars which I considered myself worth. Of course those who had placed money in my hands suffered, and among them your father. I confess that I regretted his loss as much as that of any one, for I liked his straightforward manner, and was touched by his evident confidence in me."

Mr. Bates paused a moment and then resumed:—

"I left New York, and went to Milwaukie. Here I was obliged to begin life anew, or nearly so, for I only carried a thousand dollars out with me. But I have been greatly prospered since then. I took warning by my past failures, and have succeeded, by care and good fortune, in accumulating nearly as large a fortune as the one of which I once thought myself possessed. When fortune began to smile upon me I thought of your father, and tried through an agent to find him out. But he reported to me that [28] his name was not to be found either in the New York or Brooklyn Directory, and I was too busily engaged to come on myself, and make inquiries. But I am glad to find that his son is living, and that I yet have it in my power to make restitution."

Fosdick could hardly believe his ears. Was he after all to receive the money which he had supposed irrevocably lost?

As for Dick it is not too much to say that he felt even more pleased at the prospective good fortune of his friend than if it had fallen to himself.

FOSDICK'S FORTUNE.

Mr. Bates took from his pocket a memorandum book, and jotted down a few figures in it.

"As nearly as I can remember," he said, "it is four years since I ceased paying interest on the money which your father entrusted to me. The rate I agreed to pay was six per cent. How much will that amount to?"

"Principal and interest two thousand four hundred and eighty dollars," said Dick, promptly.

Fosdick's breath was almost taken away as he heard this sum mentioned. Could it be possible that Mr. Bates intended to pay him as much as this? Why, it would be a fortune.

"Your figures would be quite correct, Mr. Hunter" said Mr. Bates, "but for one consideration. You forget that your friend is entitled to compound interest, as no interest has been paid for four years. Now, as [30] you are do doubt used to figures, I will leave you to make the necessary correction."

Mr. Bates tore a leaf from his memorandum book as he spoke, and handed it with a pencil to Richard Hunter.

Dick made a rapid calculation, and reported two thousand five hundred and twenty-four dollars.

"It seems, then, Mr. Fosdick," said Mr. Bates, "that I am your debtor to a very considerable amount."

"You are very kind, sir," said Fosdick; "but I shall be quite satisfied with the two thousand dollars without any interest."

"Thank you for offering to relinquish the interest; but it is only right that I should pay it. I have had the use of the money, and I certainly would not wish to defraud you of a penny of the sum which it took your father ten years of industry to accumulate. I wish he were living now to see justice done his son."

"So do I," said Fosdick, earnestly. "I beg your pardon, sir," he said, after a moment's pause.

"Why?" asked Mr. Bates in a tone of surprise.

"Because," said Fosdick, "I have done you injustice. I thought you failed in order to make money, [31] and intended to cheat my father out of his savings. That made me feel hard towards you."

"You were justified in feeling so," said Mr. Bates. "Such cases are so common that I am not surprised at your opinion of me. I ought to have explained my position to your father, and promised to make restitution whenever it should be in my power. But at the time I was discouraged, and could not foresee the favorable turn which my affairs have since taken. Now," he added, with a change of voice, "we will arrange about the payment of this money."

"Do not pay it until it is convenient, Mr. Bates," said Fosdick.

"Your proposal is kind, but scarcely business-like, Mr. Fosdick," said Mr. Bates. "Fortunately it will occasion me no inconvenience to pay you at once I have not the ready money with me as you may suppose, but I will give you a cheque for the amount upon the Broadway Bank, with which I have an account; and it will be duly honored on presentation to-morrow. You may in return make out a receipt in full for the debt and interest. Wait a moment. I will ring for writing materials."

These were soon brought by a servant of the hotel [32] and Mr. Bates filled in a cheque for the sum specified above, while Fosdick, scarcely knowing whether he was awake or dreaming, made out a receipt to which he attached his name.

"Now," said Mr. Bates, "we will exchange documents."

Fosdick took the cheque, and deposited it carefully in his pocket-book.

"It is possible that payment might be refused to a boy like you, especially as the amount is so large. At what time will you be disengaged to-morrow?"

"I am absent from the store from twelve to one for dinner."

"Very well, come to the hotel as soon as you are free, and I will accompany you to the bank, and get the money for you. I advise you, however, to leave it there on deposit until you have a chance to invest it."

"How would you advise me to invest it, sir?" asked Fosdick.

"Perhaps you cannot do better than buy shares of some good bank. You will then have no care except to collect your dividends twice a year."

"That is what I should like to do," said Fosdick. "What bank would you advise?"

"The Broadway, Park, or Bank of Commerce, are all good banks. I will attend to the matter for you, if you desire it."

"I should be very glad if you would, sir."

"Then that matter is settled," said Mr. Bates. "I wish I could as easily settle another matter which has brought me to New York at this time, and which, I confess, occasions me considerable perplexity."

The boys remained respectfully silent, though not without curiosity as to what this matter might be.

Mr. Bates seemed plunged in thought for a short time. Then speaking, as if to himself, he said, in a low voice, "Why should I not tell them? Perhaps they may help me."

"I believe," he said, "I will take you into my confidence. You may be able to render me some assistance in my perplexing business."

"I shall be very glad to help you if I can," said Dick.

"And I also," said Fosdick.

"I have come to New York in search of my grandson," said Mr. Bates.

"Did he run away from home?" asked Dick.

"No, he has never lived with me. Indeed, I may add that I have never seen him since he was an infant."

The boys looked surprised.

"How old is he now?" asked Fosdick.

"He must be about ten years old. But I see that I must give you the whole story of what is a painful passage in my life, or you will be in no position to help me.

"You must know, then, that twelve years since I considered myself rich, and lived in a handsome house up town. My wife was dead, but I had an only daughter, who I believe was generally considered attractive, if not beautiful. I had set my heart upon her making an advantageous marriage; that is, marrying a man of wealth and social position. I had in my employ a clerk, of excellent business abilities, and of good personal appearance, whom I sometimes invited to my house when I entertained company. His name was John Talbot. I never suspected that there was any danger of my daughter's falling in [35] love with the young man, until one day he came to me and overwhelmed me with surprise by asking her hand in marriage.

"You can imagine that I was very angry, whether justly or not I will not pretend to say. I dismissed the young man from my employ, and informed him that never, under any circumstances, would I consent to his marrying Irene. He was a high-spirited young man, and, though he did not answer me, I saw by the expression of his face that he meant to persevere in his suit.

"A week later my daughter was missing. She left behind a letter stating that she could not give up John Talbot, and by the time I read the letter she would be his wife. Two days later a Philadelphia paper was sent me containing a printed notice of their marriage, and the same mail brought me a joint letter from both, asking my forgiveness.

"I had no objections to John Talbot except his poverty; but my ambitious hopes were disappointed, and I felt the blow severely. I returned the letter to the address given, accompanied by a brief line to Irene, to the effect that I disowned her, and would never more acknowledge her as my daughter.

"I saw her only once after that. Two years after she appeared suddenly in my library, having been admitted by the servant, with a child in her arms. But I hardened my heart against her, and though she besought my forgiveness, I refused it, and requested her to leave the house. I cannot forgive myself when I think of my unfeeling severity. But it is too late too redeem the past. As far as I can I would like to atone for it.

"A month since I heard that both Irene and her husband were dead, the latter five years since, but that the child, a boy, is still living, probably in deep poverty. He is my only descendant, and I seek to find him, hoping that he may be a joy and solace to me in the old age which will soon be upon me. It is for the purpose of tracing him that I have come to New York. When you," turning to Fosdick, "referred to your being compelled to resort to the streets, and the hard life of a boot-black, the thought came to me that my grandson may be reduced to a similar extremity. It would be hard indeed that he should grow up ignorant, neglected, and subject to every privation, when a comfortable and even luxurious home awaits him, if he can only be found."

"What is his name?" inquired Dick.

"My impression is, that he was named after his father, John Talbot. Indeed, I am quite sure that my daughter wrote me to this effect in a letter which I returned after reading."

"Have you reason to think he is in New York?"

"My information is, that his mother died here a year since. It is not likely that he has been able to leave the city."

"He is about ten years old?"

"I used to know most of the boot-blacks and newsboys when I was in the business," said Dick, reflectively; "but I cannot recall that name."

"Were you ever in the business, Mr. Hunter?" asked Mr. Bates, in surprise.

"Yes," said Richard Hunter, smiling; "I used to be one of the most ragged boot-blacks in the city. Don't you remember my Washington coat, and Napoleon pants, Fosdick?"

"I remember them well."

"Surely that was many years ago?"

"It is not yet two years since I gave up blacking boots."

"You surprise me Mr. Hunter," said Mr. Bates [38] "I congratulate you on your advance in life. Such a rise shows remarkable energy on your part."

"I was lucky," said Dick, modestly. "I found some good friends who helped me along. But about your grandson: I have quite a number of friends among the street-boys, and I can inquire of them whether any boy named John Talbot has joined their ranks since my time."

"I shall be greatly obliged to you if you will," said Mr. Bates. "But it is quite possible that circumstances may have led to a change of name, so that it will not do to trust too much to this. Even if no boy bearing that name is found, I shall feel that there is this possibility in my favor."

"That is true," said Dick. "It is very common for boys to change their name. Some can't remember whether they ever had any names, and pick one out to suit themselves, or perhaps get one from those they go with. There was one boy I knew named 'Horace Greeley'. Then there were 'Fat Jack,' 'Pickle Nose,' 'Cranky Jim,' 'Tickle-me-foot,' and plenty of others.[1] You knew some of them, didn't you, Fosdick?"

"I knew 'Fat Jack' and 'Tickle-me-Foot,'" answered Fosdick.

"This of course increases the difficulty of finding and identifying the boy," said Mr. Bates. "Here," he said, taking a card photograph from his pocket, "is a picture of my daughter at the time of her marriage. I have had these taken from a portrait in my possession."

"Can you spare me one?" asked Dick. "It may help me to find the boy."

"I will give one to each of you. I need not say that I shall feel most grateful for any service you may be able to render me, and will gladly reimburse any expenses you may incur, besides paying you liberally for your time. It will be better perhaps for me to leave fifty dollars with each of you to defray any expenses you may be at."

"Thank you," said Dick; "but I am well supplied with money, and will advance whatever is needful, and if I succeed I will hand in my bill."

Fosdick expressed himself in a similar way, and after some further conversation he and Dick rose to go.

"I congratulate you on your wealth, Fosdick," [40] said Dick, when they were outside. "You're richer than I am now."

"I never should have got this money but for you, Dick. I wish you'd take some of it."

"Well, I will. You may pay my fare home on the horse-cars."

"But really I wish you would."

But this Dick positively refused to do, as might have been expected. He was himself the owner of two up-town lots, which he eventually sold for five thousand dollars, though they only cost him one, and had three hundred dollars besides in the bank. He agreed, however, to let Fosdick henceforth bear his share of the expenses of board, and this added two dollars a week to the sum he was able to lay up.

Footnotes

[1] See sketches of the Formation of the Newsboys' Lodging-house by C. L. Brace, Secretary of the Children's Aid Society.

A DIFFICULT COMMISSION.

It need hardly be said that Fosdick was punctual to his appointment at the Astor House on the following day.

He found Mr. Bates in the reading-room, looking over a Milwaukie paper.

"Good-morning, Mr. Fosdick," he said, extending his hand. "I suppose your time is limited, therefore it will be best for us to go at once to the bank."

"You are very kind, sir, to take so much trouble on my account," said Fosdick.

"We ought all to help each other," said Mr. Bates. "I believe in that doctrine, though I have not always lived up to it. On second thoughts," he added, as they got out in front of the hotel, "if you approve of my suggestions about the purchase of bank shares, it may not be necessary to go [42] to the bank, as you can take this cheque in payment."

"Just as you think best, sir. I can depend upon your judgment, as you know much more of such things than I."

"Then we will go at once to the office of Mr. Ferguson, a Wall Street broker, and an old friend of mine. There we will give an order for some bank shares."

Together the two walked down Broadway until they reached Trinity Church, which fronts the entrance to Wall Street. Here then they crossed the street, and soon reached the office of Mr. Ferguson.

Mr. Ferguson, a pleasant-looking man with sandy hair and whiskers, came forward and shook Mr. Bates cordially by the hand.

"Glad to see you, Mr. Bates," he said. "Where have you been for the last four years?"

"In Milwaukie. I see you are at the old place."

"Yes, plodding along as usual. How do you like the West?"

"I have found it a good place for business, though [43] I am not sure whether I like it as well to live in as New York."

"Shan't you come back to New York some time?"

Mr. Bates shook his head.

"My business ties me to Milwaukie," he said. "I doubt if I ever return."

"Who is this young man?" said the broker, looking at Fosdick. "He is not a son of yours I think?"

"No; I am not fortunate enough to have a son. He is a young friend who wants a little business done in your line and, I have accordingly brought him to you."

"We will do our best for him. What is it?"

"He wants to purchase twenty shares in some good city bank. I used to know all about such matters when I lived in the city, but I am out of the way of such knowledge now."

"Twenty shares, you said?"

"Yes."

"It happens quite oddly that a party brought in only fifteen minutes since twenty shares in the —— Bank to dispose of. It is a good bank, and I [44] don't know that he can do any better than take them."

"Yes, it is a good bank. What interest does it pay now?"

"Eight per cent."[2]

"That is good. What is the market value of the stock?"

"It is selling this morning at one hundred and twenty."

"Twenty shares then will amount to twenty-four hundred dollars."

"Precisely."

"Well, perhaps we had better take them. What do you say, Mr. Fosdick?"

"If you advise it, sir, I shall be very glad to do so."

"Then the business can be accomplished at once, as the party left us his signature, authorizing the transfer."

The transfer was rapidly effected. The broker's commission of twenty-five cents per share amounted to five dollars. It was found on paying this, added to the purchase money, that one hundred and nineteen

dollars remained,—the cheque being for two thousand five hundred and twenty-four dollars.

The broker took the cheque, and returned this sum, which Mr. Bates handed to Fosdick.

"You may need this for a reserve fund," he said, "to draw upon if needful until your dividend comes due. The bank shares will pay you probably one hundred and sixty dollars per year."

"One hundred and sixty dollars!" repeated Fosdick, in surprise. "That is a little more than three dollars a week."

"Yes."

"It will be very acceptable, as my salary at the store is not enough to pay my expenses."

"I would advise you not to break in upon your capital if you can avoid it," said Mr. Bates. "By and by, if your salary increases, you may be able to add the interest yearly to the principal, so that it may be accumulating till you are a man, when you may find it of use in setting you up in business."

"Yes, sir; I will remember that. But I can hardly realize that I am really the owner of twenty bank shares."

"No doubt it seems sudden to you. Don't let it make you extravagant. Most boys of your age would need a guardian, but you have had so much experience in taking care of yourself, that I think you can get along without one."

"I have my friend Dick to advise me," said Fosdick.

"Mr. Hunter seems quite a remarkable young man," said Mr. Bates. "I can hardly believe that his past history has been as he gave it."

"It is strictly true, sir. Three years ago he could not read or write."

"If he continues to display the same energy, I can predict for him a prominent position in the future."

"I am glad to hear you say so, sir. Dick is a very dear friend of mine."

"Now, Mr. Fosdick, it is time you were thinking of dinner. I believe this is your dinner hour?"

"Yes, sir."

"And it is nearly over. You must be my guest to-day. I know of a quiet little lunch room near by, which I used to frequent some years ago when I was in business on this street. We will drop in there [47] and I think you will be able to get through in time."

Fosdick could not well decline the invitation, but accompanied Mr. Bates to the place referred to, where he had a better meal than he was accustomed to. It was finished in time, for as the clock on the city hall struck one, he reached the door of Henderson's store.

Fosdick could not very well banish from his mind the thoughts of his extraordinary change of fortune, and I am obliged to confess that he did not discharge his duties quite as faithfully as usual that afternoon. I will mention one rather amusing instance of his preoccupation of mind.

A lady entered the store, leading by the hand her son Edwin, a little boy of seven.

"Have you any hats that will fit my little boy?" she said.

"Yes, ma'am," said Fosdick, absently, and brought forward a large-sized man's hat, of the kind popularly known as "stove-pipe."

"How will this do?" asked Fosdick.

"I don't want to wear such an ugly hat as that," said Edwin, in dismay.

The lady looked at Fosdick as if she had very strong doubts of his sanity. He saw his mistake, and, coloring deeply, said, in a hurried tone, "Excuse me; I was thinking of something else."

The next selection proved more satisfactory, and Edwin went out of the store feeling quite proud of his new hat.

Towards the close of the afternoon, Fosdick was surprised at the entrance of Mr. Bates. He came up to the counter where he was standing, and said, "I am glad I have found you in. I was not quite sure if this was the place where you were employed."

"I am glad to see you, sir," said Fosdick.

"I have just received a telegram from Milwaukie," said Mr. Bates, "summoning me home immediately on matters connected with business. I shall not therefore be able to remain here to follow up the search upon which I had entered. As you and your friend have kindly offered your assistance, I am going to leave the matter in your hands, and will authorize you to incur any expenses you may deem advisable, and I will gladly reimburse you whether you succeed or not."

Fosdick assured him that they would spare no efforts, and Mr. Bates, after briefly thanking him, and giving him his address, hurried away, as he had determined to start on his return home that very night.

Footnotes

[2] This was before the war. Now most of the National Banks in New York pay ten per cent., and some even higher.

INTRODUCES MARK, THE MATCH BOY.

It was growing dark, though yet scarcely six o'clock, for the day was one of the shortest in the year, when a small boy, thinly clad, turned down Frankfort Street on the corner opposite French's Hotel. He had come up Nassau Street, passing the "Tribune" Office and the old Tammany Hall, now superseded by the substantial new "Sun" building.

He had a box of matches under his arm, of which very few seemed to have been sold. He had a weary, spiritless air, and walked as if quite tired. He had been on his feet all day, and was faint with hunger, having eaten nothing but an apple to sustain his strength. The thought that he was near his journey's end did not seem to cheer him much. Why this should be so will speedily appear.

He crossed William Street, passed Gold Street, and turned down Vandewater Street, leading out of [51] Frankfort's Street on the left. It is in the form of a short curve, connecting with that most crooked of all New York avenues, Pearl Street. He paused in front of a shabby house, and went upstairs. The door of a room on the third floor was standing ajar. He pushed it open, and entered, not without a kind of shrinking.

A coarse-looking woman was seated before a scanty fire. She had just thrust a bottle into her pocket after taking a copious draught therefrom, and her flushed face showed that this had long been a habit with her.

"Well, Mark, what luck to-night?" she said, in a husky voice.

"I didn't sell much," said the boy.

"Didn't sell much? Come here," said the woman, sharply.

Mark came up to her side, and she snatched the box from him, angrily.

"Only three boxes gone?" she repeated. "What have you been doing all day?"

She added to the question a coarse epithet which I shall not repeat.

"I tried to sell them, indeed I did, Mother Watson, [52] indeed I did," said the boy, earnestly, "but everybody had bought them already."

"You didn't try," said the woman addressed as Mother Watson. "You're too lazy, that's what's the matter. You don't earn your salt. Now give me the money."

Mark drew from his pocket a few pennies, and handed to her.

She counted them over, and then, looking up sharply, said, with a frown,"There's a penny short. Where is it?"

"I was so hungry," pleaded Mark, "that I bought an apple,—only a little one."

"You bought an apple, did you?" said the woman, menacingly. "So that's the way you spend my money, you little thief?"

"I was so faint and hungry," again pleaded the boy.

"What business had you to be hungry? Didn't you have some breakfast this morning?"

"I had a piece of bread."

"That's more than you earned. You'll eat me out of house and home, you little thief! But I'll pay you off. I'll give you something to take away [53] your appetite. You won't be hungry any more, I reckon."

She dove her flabby hand into her pocket, and produced a strap, at which the boy gazed with frightened look.

"Don't beat me, Mother Watson," he said, imploringly.

"I'll beat the laziness out of you," said the woman, vindictively. "See if I don't."

She clutched Mark by the collar, and was about to bring the strap down forcibly upon his back, ill protected by his thin jacket, when a visitor entered the room.

"What's the matter, Mrs. Watson?" asked the intruder.

"Oh, it's you, Mrs. Flanagan?" said the woman, holding the strap suspended in the air. "I'll tell you what's the matter. This little thief has come home, after selling only three boxes of matches the whole day, and I find he's stole a penny to buy an apple with. It's for that I'm goin' to beat him."

"Oh, let him alone, the poor lad," said Mrs. Flanagan, who was a warm-hearted Irish woman. "Maybe he was hungry."

"Then why didn't he work? Them that work can eat."

"Maybe people didn't want to buy."

"Well, I can't afford to keep him in his idleness," said Mrs. Watson. "He may go to bed without his supper."

"If he can't sell his matches, maybe people would give him something."

Mrs. Watson evidently thought favorably of this suggestion, for, turning to Mark, she said, "Go out again, you little thief, and mind you don't come in again till you've got twenty-five cents to bring to me. Do you mind that?"

Mark listened, but stood irresolute:

"I don't like to beg," he said.

"Don't like to beg!" screamed Mrs. Watson. "Do you mind that, now, Mrs. Flanagan? He's too proud to beg."

"Mother told me never to beg if I could help it," said Mark.

"Well, you can't help it," said the woman, flourishing the strap in a threatening manner. "Do you see this?"

"Yes."

"Well, you'll feel it too, if you don't do as I tell you. Go out now."

"I'm so hungry," said Mark; "won't you give me a piece of bread?"

"Not a mouthful till you bring back twenty-five cents. Start now, or you'll feel the strap."

The boy left the room with a slow step, and wearily descended the stairs. I hope my young readers will never know the hungry craving after food which tormented the poor little boy as he made his way towards the street. But he had hardly reached the foot of the first staircase when he heard a low voice behind him, and, turning, beheld Mrs. Flanagan, who had hastily followed after him.

"Are you very hungry?" she asked.

"Yes, I'm faint with hunger."

"Poor boy!" she said, compassionately; "come in here a minute."

She opened the door of her own room which was just at the foot of the staircase, and gently pushed him in.

It was a room of the same general appearance as the one above, but was much neater looking.

"Biddy Flanagan isn't the woman to let a poor [56] motherless child go hungry when she's a bit of bread or meat by her. Here, Mark, lad, sit down, and I'll soon bring you something that'll warm up your poor stomach."

She opened a cupboard, and brought out a plate containing a small quantity of cold beef, and two slices of bread.

"There's some better mate than you'll get of Mother Watson. It's cold, but it's good."

"She never gives me any meat at all," said Mark, gazing with a look of eager anticipation at the plate which to his famished eye looked so inviting.

"I'll be bound she don't," said Mrs. Flanagan. "Talk of you being lazy! What does she do herself but sit all day doing nothin' except drink whiskey from the black bottle! She might get washin' to do, as I do, if she wanted to, but she won't work. She expects you to get money enough for both of you."

Meanwhile Mrs. Flanagan had poured out a cup of tea from an old tin teapot that stood on the stove.

"There, drink that, Mark dear," she said. "It'll warm you up, and you'll need it this cold night, I'm thinkin'."

The tea was not of the best quality, and the cup was cracked and discolored; but to Mark it was grateful and refreshing, and he eagerly drank it.

"Is it good?" asked the sympathizing woman, observing with satisfaction the eagerness with which it was drunk.

"Yes, it makes me feel warm," said Mark.

"It's better nor the whiskey Mother Watson drinks," said Mrs. Flanagan. "It won't make your nose red like hers. It would be a sight better for her if she'd throw away the whiskey, and take to the tea."

"You are very kind, Mrs. Flanagan," said Mark, rising from the table, feeling fifty per cent. better than when he sat down.

"Oh bother now, don't say a word about it! Shure you're welcome to the bit you've eaten, and the little sup of tea. Come in again when you feel hungry and Bridget Flanagan won't be the woman to send you off hungry if she's got anything in the cupboard."

"I wish Mother Watson was as good as you are," said Mark.

"I aint so good as I might be," said Mrs. Flanagan; "but I wouldn't be guilty of tratin' a poor [58] boy as that woman trates you, more shame to her! How came you with her any way? She aint your mother, is she."

"No," said Mark, shuddering at the bare idea. "My mother was a good woman, and worked hard. She didn't drink whiskey. Mother was always kind to me. I wish she was alive now."

"When did she die, Mark dear?"

"It's going on a year since she died. I didn't know what to do, but Mother Watson told me to come and live with her, and she'd take care of me."

"Sorra a bit of kindness there was in that," commented Mrs. Flanagan. "She wanted you to take care of her. Well, and what did she make you do?"

"She sent me out to earn what I could. Sometimes I would run on errands, but lately I have sold matches."

"Is it hard work sellin' them?"

"Sometimes I do pretty well, but some days it seems as if nobody wanted any. To-day I went round to a great many offices, but they all had as many as they wanted, and I didn't sell but three boxes. I tried to sell more, indeed I did, but I couldn't."

"No doubt you did, Mark, dear. It's cold you must be in that thin jacket of yours this cold weather. I've got a shawl you may wear if you like. You'll not lose it, I know."

But Mark had a boy's natural dislike to being dressed as a girl, knowing, moreover, that his appearance in the street with Mrs. Flanagan's shawl would subject him to the jeers of the street boys. So he declined the offer with thanks, and, buttoning up his thin jacket, descended the remaining staircase, and went out again into the chilling and uninviting street. A chilly, drizzling rain had just set in, and this made it even more dreary than it had been during the day.

BEN GIBSON.

But it was not so much the storm or the cold weather that Mark cared for. He had become used to these, so far as one can become used to what is very disagreeable. If after a hard day's work he had had a good home to come back to, or a kind and sympathizing friend, he would have had that thought to cheer him up. But Mother Watson cared nothing for him, except for the money he brought her, and Mark found it impossible either to cherish love or respect for the coarse woman whom he generally found more or less affected by whiskey.

Cold and hungry as he had been oftentimes, he had always shrunk from begging. It seemed to lower him in his own thoughts to ask charity of others. Mother Watson had suggested it to him once or twice, but had never actually commanded it before. Now he was required to bring home twenty-five cents. He [61] knew very well what would be the result if he failed to do this. Mother Watson would apply the leather strap with merciless fury, and he knew that his strength was as nothing compared to hers. So, for the first time in his life, he felt that he must make up his mind to beg.

He retraced his steps to the head of Frankfort Street, and walked slowly down Nassau Street. The rain was falling, as I have said, and those who could remained under shelter. Besides, business hours were over. The thousands who during the day made the lower part of the city a busy hive had gone to their homes in the upper portion of the island, or across the river to Brooklyn or the towns on the Jersey shore. So, however willing he might be to beg, there did not seem to be much chance at present.

The rain increased, and Mark in his thin clothes was soon drenched to the skin. He felt damp, cold, and uncomfortable. But there was no rest for him. The only home he had was shut to him, unless he should bring home twenty-five cents, and of this there seemed very little prospect.

At the corner of Fulton Street he fell in with a [62] boy of twelve, short and sturdy in frame, dressed in a coat whose tails nearly reached the sidewalk. Though scarcely in the fashion, it was warmer than Mark's, and the proprietor troubled himself very little about the looks.

This boy, whom Mark recognized as Ben Gibson, had a clay pipe in his mouth, which he seemed to be smoking with evident enjoyment.

"Where you goin'?" he asked, halting in front of Mark.

"I don't know," said Mark.

"Don't know!" repeated Ben, taking his pipe from his mouth, and spitting. "Where's your matches?"

"I left them at home."

"Then what'd did you come out for in this storm?"

"The woman I live with won't let me come home till I've brought her twenty-five cents."

"How'd you expect to get it?"

"She wants me to beg."

"That's a good way," said Ben, approvingly; "when you get hold of a soft chap, or a lady, them's the ones to shell out."

"I don't like it," said Mark. "I don't want people to think me a beggar."

"What's the odds?" said Ben, philosophically. "You're just the chap to make a good beggar."

"What do you mean by that, Ben?" said Mark, who was far from considering this much of a compliment.

"Why you're a thin, pale little chap, that people will pity easy. Now I aint the right cut for a beggar. I tried it once, but it was no go."

"Why not?" asked Mark, who began to be interested in spite of himself.

"You see," said Ben, again puffing out a volume of smoke, "I look too tough, as if I could take care of myself. People don't pity me. I tried it one night when I was hard up. I hadn't got but six cents, and I wanted to go to the Old Bowery bad. So I went up to a gent as was comin' up Wall Street from the Ferry, and said, 'Won't you give a poor boy a few pennies to save him from starvin'?'"

"'So you're almost starvin', are you, my lad?'" says he.

"'Yes, sir,' says I, as faint as I could.

"'Well, starvin' seems to agree with you,' says [64] he, laughin'. 'You're the healthiest-lookin' beggar I've seen in a good while.'

"I tried it again on another gent, and he told me he guessed I was lazy; that a good stout boy like me ought to work. So I didn't make much beggin', and had to give up goin' to the Old Bowery that night, which I was precious sorry for, for there was a great benefit that evenin'. Been there often?"

"No, I never went."

"Never went to the Old Bowery!" ejaculated Ben, whistling in his amazement. "Where were you raised, I'd like to know? I should think you was a country greeny, I should."

"I never had a chance," said Mark, who began to feel a little ashamed of the confession.

"Won't your old woman let you go?"

"I never have any money to go."

"If I was flush I'd take you myself. It's only fifteen cents," said Ben. "But I haven't got money enough only for one ticket. I'm goin' to-night."

"Are you?" asked Mark, a little enviously.

"Yes, it's a good way to pass a rainy evenin'. You've got a warm room to be in, let alone the play, which is splendid. Now, if you could only beg fifteen [65] cents from some charitable cove, you might go along of me."

"If I get any money I've got to carry it home."

"Suppose you don't, will the old woman cut up rough?"

"She'll beat me with a strap," said Mark, shuddering.

"What makes you let her do it?" demanded Ben, rather disdainfully.

"I can't help it."

"She wouldn't beat me," said Ben, decidedly.

"What would you do?" asked Mark, with interest.

"What would I do?" retorted Ben. "I'd kick, and bite, and give her one for herself between the eyes. That's what I'd do. She'd find me a hard case, I reckon."

"It wouldn't be any use for me to try that," said Mark. "She's too strong."

"It don't take much to handle you," said Ben, taking a critical survey of the physical points of Mark. "You're most light enough to blow away."

"I'm only ten years old," said Mark, apologetically. "I shall be bigger some time."

"Maybe," said Ben, dubiously; "but you don't look as if you'd ever be tough like me."

"There," he added, after a pause, "I've smoked all my 'baccy. I wish I'd got some more."

"Do you like to smoke?" asked Mark.

"It warms a feller up," said Ben. "It's jest the thing for a cold, wet day like this. Didn't you ever try it?"

"No."

"If I'd got some 'baccy here, I'd give you a whiff; but I think it would make you sick the first time."

"I don't think I should like it," said Mark, who had never felt any desire to smoke, though he knew plenty of boys who indulged in the habit.

"That's because you don't know nothin' about it," remarked Ben. "I didn't like it at first till I got learned."

"Do you smoke often?"

"Every day after I get through blackin' boots; that is, when I aint hard up, and can't raise the stamps to pay for the 'baccy. But I guess I'll be goin' up to the Old Bowery. It's most time for the doors to open. Where you goin'?"

"I don't know where to go," said Mark, helplessly.

"I'll tell you where you'd better go. You won' find nobody round here. Besides it aint comfortable lettin' the rain fall on you and wet you through." (While this conversation was going on, the boys had sheltered themselves in a doorway.) "Just you go down to Fulton Market. There you'll be out of the wet, and you'll see plenty of people passin' through when the boats come in. Maybe some of 'em will give you somethin'. Then ag'in, there's the boats. Some nights I sleep aboard the boats."

"You do? Will they let you?"

"They don't notice. I just pay my two cents, and go aboard, and snuggle up in a corner and go to sleep. So I ride to Brooklyn and back all night. That's cheaper'n the Newsboys' Lodgin' House, for it only costs two cents. One night a gentleman came to me, and woke me up, and said, 'We've got to Brooklyn, my lad. If you don't get up they'll carry you back again.'

"I jumped up and told him I was much obliged, as I didn't know what my family would say if I didn't get home by eleven o'clock. Then, just as [68] soon as his back was turned, I sat down again and went to sleep. It aint so bad sleepin' aboard the boat, 'specially in a cold night. They keep the cabin warm, and though the seat isn't partic'larly soft its better'n bein' out in the street. If you don't get your twenty-five cents, and are afraid of a lickin', you'd better sleep aboard the boat."

"Perhaps I will," said Mark, to whom the idea was not unwelcome, for it would at all events save him for that night from the beating which would be his portion if he came home without the required sum.

"Well, good-night," said Ben; "I'll be goin' along."

"Good-night, Ben," said Mark, "I guess I'll go to Fulton Market."

Accordingly Mark turned down Fulton Street, while Ben steered in the direction of Chatham Street, through which it was necessary to pass in order to reach the theatre, which is situated on the Bowery, not far from its junction with Chatham Street.

Ben Gibson is a type of a numerous class of improvident boys, who live on from day to day, careless of appearances, spending their evenings where they [69] can, at the theatre when their means admit, and sometimes at gambling saloons. Not naturally bad, they drift into bad habits from the force of outward circumstances. They early learn to smoke or chew, finding in tobacco some comfort during the cold and wet days, either ignorant of or indifferent to the harm which the insidious weed will do to their constitutions. So their growth is checked, or their blood is impoverished, as is shown by their pale faces.

As for Ben, he was gifted with a sturdy frame and an excellent constitution, and appeared as yet to exhibit none of the baneful effects of this habit. But no growing boy can smoke without ultimately being affected by it, and such will no doubt be the case with Ben.

FULTON MARKET.

Just across from Fulton Ferry stands Fulton Market. It is nearly fifty years old, having been built in 1821, on ground formerly occupied by unsightly wooden buildings, which were, perhaps fortunately, swept away by fire. It covers the block bounded by Fulton, South, Beekman, and Front Streets, and was erected at a cost of about quarter of a million of dollars.

This is the chief of the great city markets, and an immense business is done here. There is hardly an hour in the twenty-four in which there is an entire lull in the business of the place. Some of the outside shops and booths are kept open all night, while the supplies of fish, meats, and vegetables for the market proper are brought at a very early hour, almost before it can be called morning.

Besides the market proper the surrounding sidewalks [71] are roofed over, and lined with shops and booths of the most diverse character, at which almost every conceivable article can be purchased. Most numerous, perhaps, are the chief restaurants, the counters loaded with cakes and pies, with a steaming vessel of coffee smoking at one end. The floors are sanded, and the accommodations are far from elegant or luxurious; but it is said that the viands are by no means to be despised. Then there are fruit-stalls with tempting heaps of oranges, apples, and in their season the fruits of summer, presided over for the most part by old women, who scan shrewdly the faces of passers-by, and are ready on the smallest provocation to vaunt the merits of their wares. There are candy and cocoanut cakes for those who have a sweet tooth, and many a shop-boy invests in these on his way to or from Brooklyn to the New York store where he is employed; or the father of a family, on his way to his Brooklyn home, thinks of the little ones awaiting him, and indulges in a purchase of what he knows will be sure to be acceptable to them.

But it is not only the wants of the body that are provided for at Fulton Market. On the Fulton Street side may be found extensive booths, at which [72] are displayed for sale a tempting array of papers, magazines, and books, as well as stationery, photograph albums, etc., generally at prices twenty or thirty per cent. lower than is demanded for them in the more pretentious Broadway or Fulton Avenue stores.

Even at night, therefore, the outer portion of the market presents a bright and cheerful shelter from the inclement weather, being securely roofed over, and well lighted, while some of the booths are kept open, however late the hour.

Ben Gibson, therefore, was right in directing Mark to Fulton Market, as probably the most comfortable place to be found in the pouring rain which made the thoroughfares dismal and dreary. Mark, of course, had been in Fulton Market often, and saw at once the wisdom of the advice. He ran down Fulton Street as fast as he could, and arrived there panting and wet to the skin. Uncomfortable as he was, the change from the wet streets to the bright and comparatively warm shelter of the market made him at once more cheerful. In fact, it compared favorably with the cold and uninviting room which he shared with Mother Watson.

As Mark looked around him, he could not help [73] wishing that he tended in one of the little restaurants that looked so bright and inviting to him. Those who are accustomed to lunch at Delmonico's, or at some of the large and stylish hotels, or have their meals served by attentive servants in brown stone dwellings in the more fashionable quarters of the city, would be likely to turn up their noses at his humble taste, and would feel it an infliction to take a meal amid such plebeian surroundings. But then Mark knew nothing about the fare at Delmonico's, and was far enough from living in a brown stone front, and so his ideas of happiness and luxury were not very exalted, or he would scarcely have envied a stout butcher boy whom he saw sitting at an unpainted wooden table, partaking of a repast which was more abundant than choice.

But from the surrounding comfort Mark's thoughts were brought back to the disagreeable business which brought him here. He was to solicit charity from some one of the passers-by, and with a sigh he began to look about him to select some compassionate face.

"If there was only somebody here that wanted an errand done," he thought, "and would pay me twenty-five cents for doing it, I wouldn't have to beg [74] I'd rather work two hours for the money than beg it."

But there seemed little chance of this. In the busy portion of the day there might have been some chance, though this would be uncertain; but now it was very improbable. If he wanted to get twenty-five cents that night he must get it from charity.

A beginning must be made, however disagreeable. So Mark went up to a young man who was passing along on his way to the boat, and in a shamefaced manner said, "Will you give me a few pennies, please?"

The young man looked good-natured, and it was that which gave Mark confidence to address him.

"You want some pennies, do you?" he said, with a smile, pausing in his walk.

"If you please, sir."

"I suppose your wife and family are starving, eh?"

"I haven't got any wife or family, sir," said Mark.

"But you've got a sick mother, or some brothers or sisters that are starving, haven't you?"

"No, sir."

"Then I'm afraid you're not up to your business. How long have you been round begging?"

"Never before," said Mark, rather indignantly.

"Ah, that accounts for it. You haven't learned the business yet. After a few weeks you'll have a sick mother starving at home. They all do, you know."

"My mother is dead," said Mark; "I shan't tell a lie to get money."

"Come, you're rather a remarkable boy," said the young man, who was a reporter on a daily paper, going over to attend a meeting in Brooklyn, to write an account of it to appear in one of the city dailies in the morning. "I don't generally give money in such cases, but I must make an exception in your case."

He drew a dime from his vest-pocket and handed it to Mark.

Mark took it with a blush of mortification at the necessity.

"I wouldn't beg if I could help it," he said, desiring to justify himself in the eyes of the good-natured young man.

"I'm glad to hear that. Johnny." (Johnny is a [76] common name applied to boys whose names are unknown.) "It isn't a very creditable business. What makes you beg, then?"

"I shall be beaten if I don't," said Mark.

"That's bad. Who will beat you?"

"Mother Watson."

"Tell Mother Watson, with my compliments, that she's a wicked old tyrant. I'll tell you what, my lad, you must grow as fast as you can, and by and by you'll get too large for that motherly old woman to whip. But there goes the bell. I must be getting aboard."

This was the result of Mark's first begging appeal. He looked at the money, and wished he had got it in any other way. If it had been the reward of an hour's work he would have gazed at it with much greater satisfaction.

Well, he had made a beginning. He had got ten cents. But there still remained fifteen cents to obtain, and without that he did not feel safe in going back.

So he looked about him for another person to address. This time he thought he would ask a lady. Accordingly he went up to one, who was [77] walking with her son, a boy of sixteen, to judge from appearance, and asked for a few pennies.

"Get out of my way, you little beggar!" she said, in a disagreeable tone. "Ain't you ashamed of yourself, going round begging, instead of earning money like honest people?"

"I've been trying to earn money all day," said Mark, rather indignant at this attack.

"Oh no doubt," sneered the woman. "I don't think you'll hurt yourself with work."

"I was round the streets all day trying to sell matches," said Mark.

"You mustn't believe what he says, mother," said the boy. "They're all a set of humbugs, and will lie as fast as they can talk."

"I've no doubt of it, Roswell," said Mrs. Crawford. "Such little impostors never get anything out of me. I've got other uses for my money."

Mark was a gentle, peaceful boy, but such attacks naturally made him indignant.

"I am not an impostor, and I neither lie nor steal," he said, looking alternately from the mother to the son.

"Oh, you're a fine young man. I've no doubt," [78] said Roswell, with a sneer. "But we'd better be getting on, mother, unless you mean to stop in Fulton Market all night."

So mother and son passed on, leaving Mark with a sense of mortification and injury. He would have given the ten cents he had, not to have asked charity of this woman who had answered him so unpleasantly.

Those of my readers who have read the two preceding volumes of this series will recognize in Roswell Crawford and his mother old acquaintances who played an important part in the former stories. As, however, I may have some new readers, it may be as well to explain that Roswell was a self-conceited boy, who prided himself on being "the son of a gentleman," and whose great desire was to find a place where the pay would be large and the duties very small. Unfortunately for his pride, his father had failed in business shortly before he died, and his mother had been compelled to keep a boarding-house. She, too, was troubled with a pride very similar to that of her son, and chafed inwardly at her position, instead of reconciling herself to it, as many better persons have done.

Roswell was not very fortunate in retaining the positions he obtained, being generally averse to doing anything except what he was absolutely obliged to do. He had lost a situation in a dry-goods store in Sixth Avenue, because he objected to carrying bundles, considering it beneath the dignity of a gentleman's son. Some months before he had tried to get Richard Hunter discharged from his situation in the hope of succeeding him in it; but this plot proved utterly unsuccessful, as is fully described in "Fame and Fortune."

We shall have more to do with Roswell Crawford in the course of the present story. At present he was employed in a retail bookstore up town, on a salary of six dollars a week.

ON THE FERRY-BOAT.

Mark had made two applications for charity, and still had but ten cents. The manner in which Mrs. Crawford met his appeal made the business seem more disagreeable than ever. Besides, he was getting tired. It was not more than eight o'clock, but he had been up early, and had been on his feet all day. He leaned against one of the stalls, but in so doing he aroused the suspicions of the vigilant old woman who presided over it.

"Just stand away there," she said. "You're watchin' for a chance to steal one of them apples."

"No, I'm not," said Mark, indignantly. "I never steal."

"Don't tell me," said the old woman, who had a hearty aversion to boys, some of whom, it must be confessed, had in times past played mean tricks on [81] her; "don't tell me! Them that beg will steal, and I see you beggin' just now."

To this Mark had no reply to make. He saw that he was already classed with the young street beggars, many of whom, as the old woman implied, had no particular objection to stealing, if they got a chance. Altogether he was so disgusted with his new business, that he felt it impossible for him to beg any more that night. But then came up the consideration that this would prevent his returning home. He very well knew what kind of a reception Mother Watson would give him, and he had a very unpleasant recollection and terror of the leather strap.

But where should he go? He must pass the night somewhere, and he already felt drowsy. Why should he not follow Ben Gibson's suggestions, and sleep on the Fulton ferry-boat? It would only cost two cents to get on board, and he might ride all night. Fortunately he had more than money enough for that, though he did not like to think how he came by the ten cents.

When Mark had made up his mind, he passed out of one of the entrances of the market, and, crossing [82] the street, presented his ten cents at the wicket, where stood the fare-taker.

Without a look towards him, that functionary took the money, and pushed back eight cents. These Mark took, and passed round into the large room of the ferry-house.

The boat was not in, but he already saw it halfway across the river, speeding towards its pier.

There were a few persons waiting besides himself, but the great rush of travel was diminished for a short time. It would set in again about eleven o'clock when those who had passed the evening at some place of amusement in New York would be on their way home.

Mark with the rest waited till the boat reached its wharf. There was the usual bump, then the chain rattled, the wheel went round, and the passengers began to pour out upon the wharf. Mark passed into the boat, and went at once to the "gentlemen's cabin," situated on the left-hand side of the boat. Generally, however, gentlemen rather unfairly crowd into the ladies' cabin, sometimes compelling the ladies, to whom it of right belongs, to stand, while they complacently monopolize the seats. The gentlemen's [83] cabin, so called, is occupied by those who have a little more regard to the rights of ladies, and by the smokers, who are at liberty to indulge in their favorite comfort here.

When Mark entered, the air was redolent with tobacco-smoke, generally emitted from clay pipes and cheap cigars, and therefore not so agreeable as under other circumstances it might have been. But it was warm and comfortable, and that was a good deal.

In the corner Mark espied a wide seat nearly double the size of an ordinary seat, and this he decided would make the most comfortable niche for him.

He settled himself down there as well as he could. The seat was hard, and not so comfortable as it might have been; but then Mark was not accustomed to beds of down, and he was so weary that his eyes closed and he was soon in the land of dreams.

He was dimly conscious of the arrival at the Brooklyn side, and the ensuing hurried exit of passengers from that part of the cabin in which he was, but it was only a slight interruption, and when the boat, having set out on its homeward trip, reached the New York side, he was fast asleep.

"Poor little fellow!" thought more than one, with a hasty glance at the sleeping boy. "He is taking his comfort where he can."

But there was no good Samaritan to take him by the hand, and inquire into his hardships, and provide for his necessities, or rather there was one, and that one well known to us.

Richard Hunter and his friend Henry Fosdick had been to Brooklyn that evening to attend an instructive lecture which they had seen announced in one of the daily papers. The lecture concluded at half-past nine, and they took the ten o'clock boat over the Fulton ferry.

They seated themselves in the first cabin, towards the Brooklyn side, and did not, therefore, see Mark until they passed through the other cabin on the arrival of the boat at New York.

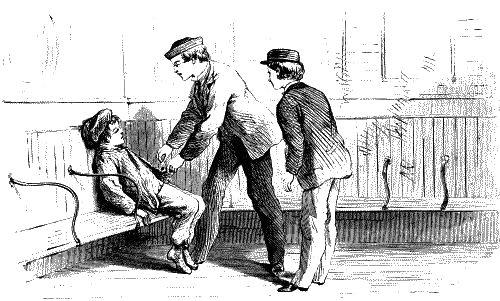

"Look there, Fosdick," said Richard Hunter. "See that poor little chap asleep in the corner. Doesn't it remind you of the times we used to have, when we were as badly off as he?"

"Yes, Dick, but I don't think I ever slept on a ferry-boat."

"That's because you were not on the streets long [85] I took care of myself eight years, and more than once took a cheap bed for two cents on a boat like this. Most likely I've slept in that very corner."

"It was a hard life, Dick."

"Yes, and a hard bed too; but there's a good many that are no better off now. I always feel like doing something to help along those like this little chap here."

"I wonder what he is,—a boot-black?"

"He hasn't got any brush or box with him. Perhaps he's a newsboy. I think I'll give him a surprise."

"Wake him up, do you mean?"

"No, poor little chap! Let him sleep. I'll put fifty cents in his pocket, and when he wakes up he won't know where it came from."

"That's a good idea, Dick. I'll do the same. All right."

"Here's the money. Put mine in with yours. Don't wake him up."

Dick walked softly up to the match boy, and gently inserted the money—one dollar—in one of the pockets of his ragged vest.

Mark was so fast asleep that he was entirely unconscious of the benevolent act.

"That'll make him open his eyes in the morning," he said.

"Unless somebody relieves him of the money during his sleep."

"Not much chance of that. Pickpockets won't be very apt to meddle with such a ragged little chap as that, unless it's in a fit of temporary aberration of mind."

"You're right, Dick. But we must hurry out now, or we shall be carried back to Brooklyn."

"And so get more than our money's worth. I wouldn't want to cheat the corporation so extensively as that."

So the two friends passed out of the boat, and left the match boy asleep in the cabin, quite unconscious that good fortune had hovered over him, and made him richer by a dollar, while he slept.

While we are waiting for him to awake, we may as well follow Richard Hunter and his friend home.

Fosdick's good fortune, which we recorded in the earlier chapters of this volume had made no particular change in their arrangements. They were [87] already living in better style than was usual among youths situated as they were. There was this difference, however, that whereas formerly Dick paid the greater part of the joint expense it was now divided equally. It will be remembered that Fosdick's interest on the twenty bank shares purchased in his name amounted to one hundred and sixty dollars annually, and this just about enabled him to pay his own way, though not leaving him a large surplus for clothing and incidental expenses. It could not be long, however, before his pay would be increased at the store, probably by two dollars a week. Until that time he could economize a little; for upon one thing he had made up his mind,—not to trench upon his principal except in case of sickness or absolute necessity.

The boys had not forgotten or neglected the commission which they had undertaken for Mr. Hiram Bates. They had visited, on the evening after he left, the Newsboys' Lodging House, then located at the corner of Fulton and Nassau Streets, in the upper part of the "Sun" building, and had consulted Mr. O'Connor, the efficient superintendent, as to the boy of whom they were in search. But he had no [88] information to supply them with. He promised to inquire among the boys who frequented the lodge, as it was possible that there might be some among them who might have fallen in with a boy named Talbot.