Printed by

M'Caw, Stevenson & Orr, Limited,

Linenhall Works,

Belfast.

The favourable reception which was accorded to the paper entitled "The Spanish Armada in Ulster and Connacht," which appeared in Vol. I., Part III., April, 1895, of The Ulster Journal of Archæology, and the continued interest in the subject, which seems rather to increase as the literature becomes more extensive, has induced me to re-write the paper, and add much information I was not possessed of when the first paper was printed. Mr. Crawford's most valuable contribution, which forms the second part of this book, should at least justify the present publication. To Francis Joseph Bigger, M.R.I.A., my best thanks are due for the use of copious notes and references, which have been of material assistance.

Ballyshannon, May, 1897.

THE publication of a work entitled "La Armada Invincible" [Madrid, 1885], by Captain Cesareo Fernandez Duro, a Spanish naval officer, has been the means of bringing to light many fresh and interesting particulars relating to this ill-fated venture; and, though the incidents narrated are, as might be expected, viewed from the Spanish standpoint, yet the history is written in a spirit of moderation, and gives evidence of great research.

Amongst the valuable documents which have been collected and printed by Captain Duro, that having for its title "Letter of One who was with the Armada for England, and an Account of the Expedition," is of most lively interest to us, seeing that it presents a graphic picture of the North and North-West of Ireland in 1588, drawn by one who was an actual eye-witness of what he describes.

FIGUREHEAD OF A SPANISH GALLEON

WRECKED AT STREEDAGH, 1588.

(Now in possession of Simon Cullen, J.P., Sligo.)

Before proceeding, it may be well to observe that these adventures have already been dealt with by several writers. The Nineteenth Century, September, 1885, contained a valuable and interesting paper, entitled "An Episode of the Armada," by the Earl of Ducie. In Longman's Magazine [September, October, and November, 1891] appeared "The Spanish Story of the Armada," by J. A. Froude; and in the Proceedings, Royal Irish Academy, 1893, Professor J. P. O'Reilly contributed a paper, entitled "Remarks on Certain Passages in Captain Cuellar's Narrative."

The present paper has been written with the desire to identify some of the places visited by Cuellar while in Connaught and Ulster. His references to these places are, as might have been expected from a foreigner, in many instances obscure; and in order to correctly trace his wanderings, and identify the spots he visited, an intimate acquaintance with the local topography of the district is essential.

Sometimes the clue afforded by his narrative is so slender, that anyone unfamiliar with the localities intended might easily miss the meaning, and be led to an entirely wrong conclusion. The present writer has had the valuable assistance of R. Crawford, C.E., late Professor of Engineering, T.C.D., an accomplished Spanish scholar—not merely a translator—who possesses a practical acquaintance with the idioms of the language. By this knowledge, Mr. Crawford has been able to elucidate many obscure passages in the Spanish book, which would otherwise have proved stumbling-blocks in the way of a proper understanding of the author's meaning. Mr. Crawford has made a literal translation of the whole of Cuellar's letter, which forms the second part of this book. A careful perusal of Mr. Crawford's introductory remarks, and of his translation, will well repay the reader, and is, in fact, needful for the proper understanding of the subject-matter of these pages.

Before entering on Cuellar's adventures on Irish soil, it may be as well to refer to an evident error into which Mr. Froude has fallen in his description of the wreck of the three vessels in Sligo Bay, in one of which Cuellar was. In the article before referred to, the following passage occurs: "Don Martin, after an ineffectual struggle to double Achill Island, had fallen back into the bay, and had anchored off Ballyshannon in a heavy sea with two other galleons. There they lay for four days, from the first to the fifth of September, when, the gale rising, their cables parted, and all three drove on shore on a sandy beach among the rocks. Nowhere in the world does the sea break more violently than on that cruel, shelterless strand," etc. Now, the facts disclosed by Cuellar's narrative, and by other contemporary writers, show that these Spanish ships were not at all near to Ballyshannon; but having been caught in the violent gales which were then raging round the coast, they were disabled, and being at the best of times unwieldy and difficult to steer, they drifted down from the north, and, failing to double Erris Head, were drawn into Sligo Bay, where they anchored about a mile and a half off shore, in the hope of being able to repair damages, and, when the gales subsided, proceed on their homeward voyage.

Don Francisco Cuellar was captain of the San Pedro, a galleon of twenty-four guns, which belonged to the squadron of Castile. The account of Cuellar's adventures, as detailed by himself, are related in the letter to which reference has been made. This document was discovered in the archives of the Academia de la Historia, in Madrid, where it had lain in oblivion for three centuries. Passing over the first part of the letter, which relates his adventures in the San Pedro, which sustained great damage in an engagement with English vessels off the coast of France, being in a leaky and unseaworthy condition, owing to the number of "shot holes," the San Pedro, by order of the mate (Cuellar having retired to take some rest after the fight), moved a short distance away from the Admiral's ship, for the purpose of carrying out some repairs to the damaged hull. This action on the part of the San Pedro raised the anger of the Admiral, who ordered Cuellar and another officer to be hanged at the yard's arm. Fortunately for Cuellar this unjust sentence was not carried out in his case, chiefly through the friendly offices of the Judge Advocate—Martin de Aranda.

But Cuellar was no longer left in command of the San Pedro: he henceforward sailed in the vessel of the Judge Advocate, who was also styled Provost Marshal. Having passed round the north coast of Scotland, the vessel in which Cuellar was, in company with two other ships—all of large tonnage—encountered head winds and rough weather. Passing Tory Island, they were endeavouring to clear Erris Head on the Mayo coast; but the storms increasing, and the sea running high, they were unable to make that point. With shattered spars and torn canvas, and a weight of water in their holds, which the constant working of the pumps could hardly keep under, these vessels in a rough sea were unmanageable, and, drifting downwards, found themselves enbayed off the Sligo coast, where they hoped to find temporary anchorage. In the sailing instructions given by the Duke of Medina to the Spanish vessels on their return home, the following occurs: "The course that is first to be held is to the north-north-east, until you be found under 61 degrees and a half, and then to take great heed lest you fall upon the Island of Ireland, for fear of the harm that may happen unto you upon that coast. Then parting from those islands, and doubling the Cape in 61 1⁄2 degrees, you shall run west-south-west, until you be found under 58 degrees, and from thence to the south-west," etc. These particulars are valuable in showing the direction in which the Spaniards endeavoured to navigate their unwieldy craft. Captain Duro in his book refers to the frequency of the opening of the seams in the old Spanish ships, which defect he attributes to the excessive weight and height of the masts, whose leverage in heavy weather caused a strain on the hulls which necessitated the constant employment of caulkers.

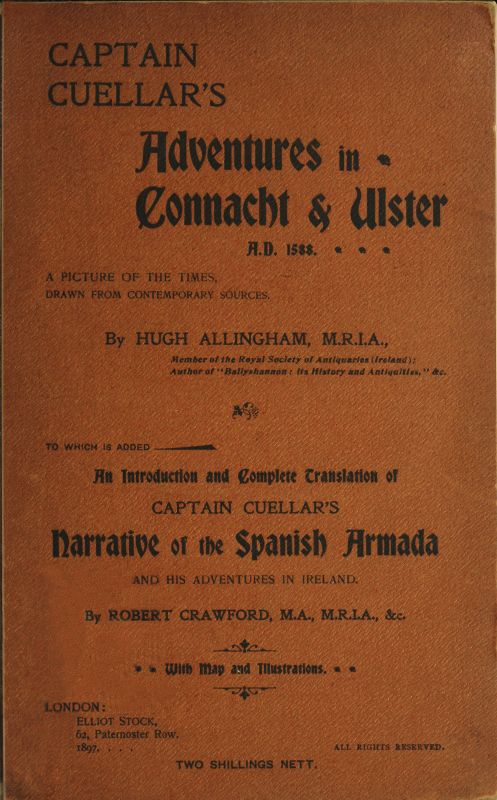

A Map of the West and North West Coasts of Ireland,

Drawn in 1609. From the original in the British Museum

showing the places connected with the Spanish Armada.

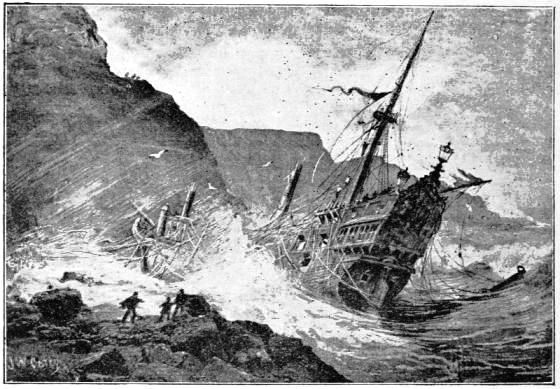

Cuellar says they anchored half a league from the shore, where they remained "four days without being able to make any provision or do anything. On the fifth day there sprang up such a great storm," he says, "on our beam, with a sea up to the heavens, so that the cables could not hold, nor the sails serve us, and we were driven ashore upon a beach covered with very fine sand, shut in on one side and the other by great rocks. Such a thing was never seen; for within the space of an hour all three ships were broken in pieces, so that there did not escape 300 men, and more than 1,000 were drowned, and amongst them many persons of importance—captains, gentlemen, and other officials." Of the three vessels which were wrecked on the Streedagh Strand—(in a map of the coast, made in 1609, the rock, which is still called Carrig-na-Spaniagh, is thus marked: "Three Spanish shipps here cast ashore in Anno Domi, 1588")—the name of one was the San Juan de Sicilia. She was commanded by Don Diego Enriquez, "the Hunchback."

This officer, as Cuellar relates, came to his death in a sad way. Fearing the very heavy sea that was washing over the deck of his vessel, which was going to pieces on the strand, he ordered out his large boat, a decked one, and, accompanied by the Count of Villa Franca, and two other Portuguese gentlemen, they closed themselves into the hold of the boat, hoping to be washed ashore. Having gone below, and bringing with them sixteen thousand ducats in jewels and crown pieces, they ordered the hatchway to be tightly fastened down, in order to prevent the ingress of water; but just as the boat was leaving the disabled ship, more than seventy men, terror-stricken with the fate that awaited them, wildly jumped on the deck of the boat, hoping thereby to reach the land; but the small craft, unable to bear the great weight above water-line, and having been struck by a wave, toppled over and sank, all on deck being swept away. She afterwards rose to the surface, and was drifted about in different directions, ultimately reaching the shore upside down. Those unfortunates who were below were all killed, with the exception of Don Diego Enriquez, who, after being in such a sad condition for more than twenty-four hours, was found still living when the hold was broken into by the "savages" who were searching for plunder. They took out the dead men, and Don Diego, who only survived a few minutes; and, having[10] secured the plunder—jewels and money—left the dead stripped and naked on the strand, denying them even the rights of Christian burial! Cuellar, though in great extremities, was not unmindful of the kindness he had received from the Judge Advocate, Martin de Aranda. "One touch of nature makes the whole world kin." Cuellar, the deposed captain, and the Judge Advocate, were standing on the same deck, with the horrors of death facing them on all sides. Martin de Aranda, seeing the destruction of all that was dear to him, had little energy left to make any effort to escape; but Cuellar endeavoured to rally his drooping spirits, and made every effort he could to help him, and bring him to shore. Taking a hatchway from the deck of the vessel they were in, Cuellar got it afloat, and succeeded in getting the Judge Advocate on also; but in the act of casting off from the ship, a huge wave engulphed them, and the Judge Advocate, being unable to hold on, was drowned. Cuellar, grievously wounded by being struck by pieces of floating timber, succeeded in keeping his footing on the hatchway, and at length reached the shore, "unable to stand, all covered with blood, and very much injured."[1]

Fenton, writing to Burleigh (State Papers, 1588-9), says: "At my late being in Sligo, I found both by view of eye and credible report that the number of ships and men perished at these coasts was more than was advertised thither by the Lord Deputy and Council, for I numbered in one strand [Streedagh], of less than five miles in length, eleven hundred dead corpses of men which the sea had driven on the shore. Since the time of the advertisement, the country people told me the like was in other places, though not of like numbers; and the Lord Deputy, writing to the Council, says: 'After leaving Sligo, I journeyed towards Bundroys [Bundrowse] and so to Ballyshannon, the uttermost part of Connaught that way, and riding still along the sea-shore, I went to see the bay where some of these ships were wrecked, and where, as I heard not long before, lay twelve or thirteen hundred of the dead bodies. I rode along that strand near two miles (but left behind me a long mile and more), and then turned off that shore; in both which places, they said that had seen it, there lay as great store of timber of wrecked ships as was in that place which myself had viewed, being in my opinion (having small skill or judgment therein) more than would have built four of the greatest ships I ever saw, beside mighty great boats, cables, and other cordage answerable thereto,[11] and such masts, for bigness and length, as in my knowledge I never saw any two that could make the like.'"

The account given by the Lord Deputy of his journey from Sligo to Ballyshannon, though rather obscurely worded, points to the probability of there having been more than one spot on that coast which was a scene of disaster. It is evident that the entire shore from Streedagh to Bundrowse was littered with the wreckage of the Spanish vessels, and it could hardly be expected that all the "flotsam and jetsam" referred to in the report we have quoted would have come from the three vessels described by Cuellar.

To return to the narrative. Cuellar now found himself in a desperate plight; wounded, half-naked, and starving with hunger, he managed to creep into a place of concealment during the remainder of the day; and he says: "At the dawn of day I began to walk little by little, searching for a monastery of monks that I might repair to it as best I could, the which I arrived at with much trouble and toil, and I found it deserted, and the church and images of the Saints burned and completely ruined, and twelve Spaniards hanging within the church by the act of the English Lutherans, who went about searching for us to make an end of all of us who had escaped from the perils of the sea." Some writers on this shipwreck have been unable to explain this reference to a monastery in the vicinity of the sea-shore at Streedagh. No such difficulty, however, exists in identifying the place indicated; for within sight of the strand stood the Abbey of Staad, which tradition says was founded by St. Molaise, the patron saint of the neighbouring island of Inismurray. It was then to this monastery that Cuellar repaired, in the expectation of finding there a safe asylum in his dire necessity. He was, however, disappointed; for he found the place deserted, and several of his fellow-countrymen hanging from the iron bars of the windows. The ruins of Staad Abbey, which still remain, are inconsiderable, consisting of portions of the church, which was oblong in form, and measured, internally, 34 feet in length by 14 feet 5 inches in width. There are indications that a much older building once occupied the site of the existing ruin. Outside the walls of the old church it was customary to light beacons for the purpose of signalling with the inhabitants of Inismurray and elsewhere, and this mode of communication by fire-signals was adopted in Ireland from remote times, and its existence amongst us to the present day is an interesting survival of primitive life. Cuellar, sick at heart with the ghastly spectacle in the monastery, betook himself to a road "which lay through a great wood," and after wandering about[12] without being able to procure any food, he turned his face once more to the sea-shore, in the hope of being able to pick up some provisions that might have been washed in from the wrecks. Here he found, stretched on the strand in one spot, more than 400 Spaniards, and amongst them he recognised Don Enriquez and another honoured officer. He dug a hole in the sand and buried his two friends. After some time he was joined by two other Spaniards. They met a man who seemed rather friendly towards them. He directed them to take a road which led from the coast to a village, which Cuellar describes as "consisting of some huts of straw." This was probably the village of Grange, a couple of miles distant; and the huts he refers to were the cabins with thatched roofs, still a common feature in the country. From descriptions of these, which are given by writers of the 16th century, there seems to be but slight difference in the mode of constructing cabins then and now. At Grange was a castle in which soldiers were stationed. It was an important outpost at the period, being on the highway between Connacht and Tirconnell. From this castle, bodies of soldiers used to sally forth, scouring the neighbourhood for Spanish fugitives and plunder. Fearing these military scouts, Cuellar turned off from the village, and entered a wood, in which he had not gone far when a new misfortune befel him. He was set upon by an "old savage," more than seventy years of age, and by two young men—one English, the other French. They wounded him in the leg, and stripped him of what little clothing was left to him. They took from him a gold chain of the value of a thousand reals; also forty-five gold crown pieces he had sewed into his clothing, and some relics that had been given him at Lisbon. But for the interference of a young girl, whom Cuellar describes as of the age of twenty, "and most beautiful in the extreme," it would have gone hard with him in the hands of these men. Having robbed him of all he had, they went on their way in search of further prey, and the young girl, pitying the sad condition of the Spaniard, made a salve of herbs for his wounds, and gave him butter and milk, with oaten bread to eat.

Cuellar was directed to travel in the direction of some mountains, which appeared to be about six leagues distant, behind which there were good lands belonging to an "important savage," a very great friend of the King of Spain. The distances in leagues and miles given in the narrative are in most cases considerably over-estimated, and cannot be relied on. Cuellar, it should be remembered, is describing events which happened to him in a strange country,[13] wherein the names of the places, and the distances from place to place, were alike unknown to him; and the journeys he was forced to make, in his lame and wretched condition, must have seemed to him very much longer than they were in reality. A right understanding of this part of the narrative is important, as some writers have fallen into the error of supposing that Cuellar's course was in the direction of the Donegal Mountains, on the other side of the bay, visible, no doubt, from the locality of the wreck, but on the distant northern horizon. A careful reading of the text will show that this was not the direction he took. He says: "I began to walk as best I could, making for the north[2] of the mountains, as the boy had told me." This means that he kept on the north, or sea-side of the Dartry Mountains; and behind them (i.e., on the south side) were good lands belonging to a friendly chief. The word "north" does not here refer to the cardinal point, but is used merely as a relative term, just as "right and left," "back and front," are used in familiar conversation. Besides, Cuellar plainly states the name of the chief he was seeking to reach: he speaks of him as "Senior de Ruerque" (Spanish for O'Rourque), whose territory lay in the direction of the mountain range he was travelling towards. He calls him an "important savage"—a term which he applies to the Irish natives he met with, whether friendly or the reverse: it does not refer to their treatment of him personally; but he intends it to define what he considers their position in the scale of civilization as compared with his own country. Journeying on in the direction pointed out to him, he came to a lake, in the vicinity of which were about thirty huts—all forsaken and untenanted. Going into one of these for shelter, he discovered three other naked men—Spaniards—who had met the same hard treatment as himself. The only food they could obtain here was blackberries and water-cresses. Covering themselves up with some straw, they passed the night in a hut by the lake-side, resolving at daybreak to push forward towards O'Rourke's village.

The lake to which reference is here made is evidently Glenade Lough, from which it was an easy journey to O'Rourke's settlement at Glencar. O'Rourke had another "town" at Newtown, on the borders of the County of Sligo. It seems probable, however, that at this time he had removed his people to Glencar. In the Lough here were several crannogs, remains of which are still visible. Such lacustrine habitations were usually resorted to by the Irish chiefs in times of[14] disturbance; for within their stockaded lake-dwellings they and their possessions were safest from the attack of the enemy. Having arrived at "the village," Cuellar found the chief absent, being at war with the English, who were at the time in occupation of Sligo. Here he found a number of Spaniards. Before many days passed, tidings came that a Spanish ship, probably one of De Leyva's vessels, was standing off the coast, and on the look-out for any Spaniards who had escaped with their lives. Hearing this, Cuellar and nineteen others resolved to make an effort to reach the vessel. They, therefore, set off at once towards the coast. They met with many hindrances on the way; and Cuellar, probably owing to the wounded state of his leg, was unable to keep pace with the others, and was consequently left behind, while the others got on board the vessel. He regards this circumstance of his being left behind as a special interference of Providence on his behalf, for the ship, after setting sail, was, he says, "wrecked off the same coast, and more than 200 persons were drowned."

Resuming the course of Cuellar's fortunes, we find him pursuing his way by the most secluded routes for fear of the "Sassana horsemen," as he styles the English soldiers. He soon fell in with a clergyman, who entered into friendly converse with him in the Latin tongue—a language, it may be observed, that did not at that period in Ireland rank as a "dead" one—men and women of various degrees, both high and low, spoke it freely; of this there is abundant evidence from contemporary writers. The clergyman gave Cuellar some of the food he had with him, and directed him to take a road which would bring him to a castle which belonged to a "savage" gentleman, "a very brave soldier, and a great enemy of the Queen of England—a man who had never cared to obey her or pay tribute, attending only to his castle and mountains, which [latter] made it strong." Following the course pointed out to him, Cuellar met with an untoward circumstance which caused him much anxiety; he was met by a blacksmith who pursued his calling in a "deserted valley." Here he was forced to abide, and work in the forge. For more than a week he (the Spanish officer) had to blow the forge bellows, and, what was worse, submit to the rough words of the blacksmith's wife, whom he calls "an accursed old woman." At length, his friend the clergyman happened again to pass that way, and seeing Cuellar labouring in the forge, he was displeased. He comforted him, assuring him he would speak to the chief of the castle to which he had directed him, and ask that an escort should be sent for him. The following day this promise was fulfilled, and four men from the castle, and a Spanish[15] soldier who had already found his way thither, arrived, and safely conducted him on his way. Here he seems at last to have found kind and humane treatment. He specially mentions the extreme kindness shown him by the chief's wife, whom he describes as "beautiful in the extreme."

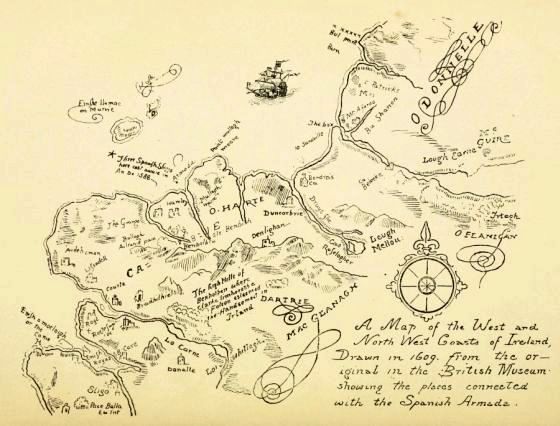

Cuellar, in taking the course pointed out to him by the clergyman, was travelling in an eastward direction, having his back turned on O'Rourke's village, whither he had first gone for succour. The "deserted valley," in which he fell in with the blacksmith, was doubtless the beautiful valley of Glenade, from which place to the island castle of Rossclogher was an easy journey. As this castle is a prominent feature in our narrative, some particulars regarding it and its chiefs may be here noted.

The castle of Rossclogher, the picturesque ruins of which are still prominent in the beautiful scenery of Lough Melvin, was built by one of the clan, at a period—precise date not known—anterior to the reign of Henry VIII. In the Irish Annals the name of MacClancy, chief of Dartraigh, appears at A.D. 1241. The territory was held by the family for three hundred years, their property having been finally confiscated after the wars of 1641. The castle lies close to the southern shore of Lough Melvin, considerably to the westward of the island of Inisheher (see Ordnance Map). It is a peculiar structure, being built on an artificial foundation, somewhat similar to the "Hag's Castle" in Lough Mask, and to Cloughoughter Castle in the neighbouring county of Cavan. Here may be noted a striking instance of the accuracy and appropriateness of Irish names of places. When the island of Inisheher (Inis Siar), i.e., western island, got its name, the site of Rossclogher Castle had not been laid, for where the castle stands is considerably further west than the last natural island, which, from its name, marks it as the most westerly island of the lough.

The Irish name of this family was MacFhlnncdaha, the name being variously written in the State Papers as McGlannogh, McGlanthie, etc., while in the Spanish narrative it is Manglana. In a map drawn in 1609, the territory is marked "Dartrie MacGlannagh" (which see). The MacClancys were chiefs, subject to O'Rourke, and their territory—a formidable one, by reason of its mountains and fastnesses—comprised the entire of the present barony of Rossclogher. According to local tradition, which survived when O'Donovan visited the district in the summer of 1836[3], the extent of "Dartree MacClancy" was from Glack townland on the east to Bunduff[16] on the west—a distance of about six miles; and from Mullinaleck townland on the north to Aghanlish on the south—a distance of about three miles. The townlands of Rossfriar (Ross-na-mbraher, i.e., the Peninsula of the Friars), and that now called Aghanlish, were ancient termon lands appertaining to the church of Rossclogher, the ruins of which stand on the mainland, close to the island castle of our narrative. The romantic and beautiful district over which the MacClancys held sway included Lough Melvin, with its islands and the mountain range behind. Within its bounds were two castles—that of Rossclogher and Dun Carbery. On the island of Iniskeen was MacClancy's crannog; and here it may be pointed out a frequent error has been made in supposing that the Castle of Rossclogher stood on Iniskeen. The crannog was on that large island which is far to the east of the Castle of Rossclogher. This was merely used in troublous times as a place of security—a sort of treasure-house; but not an ordinary dwelling-place. Besides the buildings already mentioned within the territory, were at least three monasteries—that of Doire-Melle, Cacair-Sinchill, and Beallach-in-Mithidheim—as well as numerous churches, the ruins of some being still in existence. The MacClancy clan appear to have sprung from a stock totally distinct from the neighbouring clans of Brefney. Their chief residence was at Rossclogher, but they had another castle—that of Dun Carbery—some ruins of which are still standing close to the village of Tullaghan. This was built in the sixteenth century, and a more commanding site for a fortified house it would have been difficult to select. It was built on the summit of an extensive Dun, or fort, which belonged to a period long anterior to the MacClancy rule; and it is a noticeable fact that the name of the original owner of the Dun Carbery, son of Niall of the Nine Hostages (fifth century), has continued to the present day as the name by which the castle is known.

The Castle of Rossclogher is built on a foundation of heavy stones laid in the bed of the lake, and filled in with smaller stones and earth to above water-level. The sub-structure was circular in form, and the entire was encompassed by a thick wall, probably never more than five feet in height. The walls of the castle are very thick, and composed of freestone, obtained from an adjacent quarry on the mainland. They are cemented together with the usual grouting of lime and coarse gravel, so generally used by the builders of old; the outside walls were coated with thick rough-cast, a feature not generally seen in old structures in the locality. Facing the south shore, which is about one[17] hundred yards distant, are the remains of a bastion pierced for musketry. The water between the castle and the shore is deep, and goes down sheer from the foundation.

On the shore, close to the castle, are the remains of military earthworks, evidently constructed by some enemy seeking possession of the castle. On the summit of a hill immediately over this, is a circular enclosure about 220 feet in circumference; it is composed of earth, faced with stone-work. Here the MacClancy-clan folded their flocks and herds, and from this ancient "cattle-booley" a bridle-path led to the mountains above. Portions of this pathway have recently been discovered; it was only two feet in width, and regularly paved with stones enclosed by a kerb.

On the mainland, close to the southern shore, and within speaking distance of the castle, stand the ruins of the old church which was built by MacClancy, and which is of about the same date as the castle to which it was an appendage. In the immediate neighbourhood of the shore, guarded on one side by the lofty mountain range of Dartraigh, on the other by the waters of Lough Melvin, was MacClancy's "town"—an assemblage of primitive huts, probably circular in shape, and of the simplest construction, where dwelt the followers and dependents of the chief, ready, by night or by day, to obey the call to arms, or, as Cuellar expresses it, "Go Santiago," a slang expression in Spain, meaning to attack.[4]

Of the manners and customs of the natives, Cuellar makes sundry observations. Having described at length how he occupied his leisure in the castle by telling the fortunes of the ladies by palmistry, he mentions incidentally that their conversation was carried on in Latin. He goes on to speak of the natives, or "savages," as he calls them. He says: "Their custom is to live as the brute beasts among the mountains, which are very rugged in that part of Ireland where we lost ourselves. They live in huts made of straw; the men are all large bodied and of handsome features and limbs, active as the roe-deer. They do not eat oftener than once a day, and this is at night; and that which they usually eat is butter with oaten bread. They drink sour milk, for they have no other drink; they don't drink water, although it is the best in the world. On feast days they eat some flesh, half-cooked, without bread or salt, for that is their custom. They clothe themselves, according to their habit, with tight trousers and short loose coats of very coarse goat's hair. They cover themselves[18] with blankets, and wear their hair down to their eyes. They are great walkers, and inured to toil. They carry on perpetual war with the English, who here keep garrison for the Queen, from whom they defend themselves, and do not let them enter their territory, which is subject to inundation and marshy."

The reference Cuellar makes to the food of the Irish with whom he sojourned is interesting. He says: "They do not eat oftener than once a day, and this is at night, and that which they usually eat is butter with oaten bread." The partiality for oaten bread here spoken of still survives; but its use has within the last half century greatly declined, owing to the extensive introduction of "white bread," the term applied to ordinary bakers' loaves. When the tide of emigration to America—in the early part of this century—was in full flow from Ballyshannon, the emigrants had to provide their own food on the voyage from this port to the Western Continent, and that universally taken with them was an ample supply of oaten cakes. It may not be out of place here to refer to the curious belief which still lives in the minds of the peasantry of this district, though, like most of the survivals of folklore, it is fading from the memories of the people.

The Feàr-Gortha, or Hungry Grass, is believed to grow in certain spots, and whoever has the bad luck to tread on this baneful fairy herb is liable to be stricken down with the mysterious complaint. The symptoms, which come on suddenly, are complete prostration, preceded by a general feeling of weakness; the sufferer sinks down, and, if assistance is not at hand, he perishes. It is believed that if food be partaken of in the open air, and the fragments remaining be not thrown as an offering to the "good folk," that they will mark their displeasure by causing a crop of "hungry grass" to arise on the spot and produce the effects described. Fortunately, the cure is as simple as the malady is mysterious. Oatcake is the specific, or, in its absence, a few grains of oatmeal. The wary traveller who knows the dangers of the road, carries in his pocket a small piece of oatcake, not intended as food, but as a charm against the Feàr-Gortha.

Cuellar also observes that the chief inclination of these people is to plunder their neighbours, capturing cattle and any other property obtainable, the raids being chiefly carried out at night. He also remarks that the English garrison were in the habit of making plundering expeditions into the territory of these natives, and the only refuge they had was, on the approach of the soldiers, to withdraw to the mountains with their families and cattle till the danger would be[19] past. Speaking of the women, he says: "Most of them are very beautiful, but badly-dressed. The head-dress of the women is a linen cloth, doubled over the head and tied in front." He remarks "the women are great workers and housekeepers, after their fashion." Speaking of the churches, etc., he says most of them have been demolished by the hands of the English, and by those natives who have joined them, who are as bad as they. He concludes his by-no-means flattering description in these words: "In this kingdom there is neither justice nor right, and everyone does what he pleases."

The "sour milk" Cuellar speaks of is buttermilk, as great a favourite here in the nineteenth century as in the sixteenth. The cloth which he calls "very coarse goats' hair" was probably the familiar homespun woollen frieze, which from the earliest times was made by the Irish. The head-dress of the women—a linen cloth—is still adopted by elderly women here.

After enjoying a short period of rest in MacClancy's, or, as Cuellar styles it, Manglana's castle, rumours of an alarming nature reached them. The Lord Deputy Fitzwilliam, or, as he is called in the narrative, "the great governor of the Queen," was marching from Dublin, with a force of 1,700 soldiers, in search of the lost ships and the people who had escaped the fury of the waves, and no quarter could be expected for either the Irish chiefs or the shipwrecked Spaniards; all that came within Fitzwilliam's grasp would certainly be hanged. Cuellar says the Lord Deputy marched along the whole coast till he arrived at the place where the shipwreck happened (at Streedagh), and from thence he came towards the castle of "Manglana." It is at this point of his narrative that he first mentions the name of the chief who had given him refuge.

MacClancy seeing the force that had come against him, felt himself unable to stand a siege, and decided to escape to the friendly shelter of his mountains. He called Cuellar aside and made known his determination, and advised that he and the other Spaniards should consider what they would do for their own safety. Cuellar consulted with his fellows, and they finally agreed that their only chance of life was to hold out in the castle as long as possible, trusting to its strength and isolated situation; and, leaving the result to the fortunes of war, they determined to stand or fall together.

Having communicated their decision to MacClancy, he willingly provided them with all the arms within his reach, and a sufficient store of provisions to last for six months. He made them take an oath to hold the castle "till death," and not to open the gates for[20] "Irishman, Spaniard, or anyone else till his return." Having made these preparations, and removed the furniture and relics out of the church on the shore, and deposited them within the castle, MacClancy, after embracing Cuellar, withdrew to the mountains, taking with him his family and followers, with their flocks and herds. Cuellar now provided himself with several boat-loads of stones, six muskets, and six crowbars, as well as a supply of ammunition. He gives a minute description of the place he was going to defend. He says: "The castle is very strong and very difficult to take, if they do not attack it with artillery, for it is founded in a lake of very deep water, which is more than a league wide at some parts, and three or four leagues long, and has an outlet to the sea; and besides, with the rise of spring tides, it is not possible to enter it; for which reason the castle could not be taken by water, nor by the shore of land which is nearest it, neither could injury be done it, because a league around the 'town,' which is established on the mainland, it is marshy, breast deep, so that even the inhabitants [natives] could not get to it except by paths." These paths, through bogs and shallow lakes, were made of large stones in a hidden, irregular way, unknown to any except those who had the key to their position. Three centuries ago, the aspect of the country was very different from what it now is: the land was in a swampy, undrained condition, and, beyond small patches here and there, which had been cleared for growing corn, dense thickets of brushwood covered the surface everywhere; and, as there were no roads or bridges, but merely narrow paths, where two horsemen could not pass each other, the difficulty—not to say impossibility—of bringing troops, heavy baggage, and artillery across country is apparent. That such a state of things existed in MacClancy's territory there is abundant evidence. The stones with which Cuellar provided himself were a favourite item in the war materials of that period: these were used with deadly effect from the towers of castles, and were also thrown from cannon instead of iron balls. Cuellar says: "Our courage seemed good to the whole country, and the enemy was very indignant at it, and came upon the castle with his forces—about 1,800 men—and observed us from a distance of a mile and a half from it, without being able to approach closer on account of the water [or marshy ground] which intervened." From this description, it is evident the Lord Deputy's forces had taken up their position on the shore of the opposite promontory of Rossfriar—a tongue of land which projects itself into the lough at the north-west end. From this point he says they exhibited "menaces and warnings," and hanged two[21] Spanish fugitives they had laid hold of, "to put the defenders in fear." The troops demanded by trumpet a surrender of the castle, but the Spaniards declined all proposals. For seventeen days, Cuellar says, the besiegers lay against them, but were unable to get a favourable position for attack. "At length, a severe storm and a great fall of snow compelled them to withdraw without having accomplished anything." In the State Papers, under date 12th October, 1588, the Lord Deputy asks the Privy Council of England to send at once two thousand "sufficient and thoroughly appointed men" to join the service directed against the main body of 3,000 Spaniards in O'Donnell's country and the North. In the same month, Fenton writes to the Lord Deputy "that the Spaniards are marching towards Sligo, and are very near Lough Erne." There were, no doubt, a large number of Spaniards who had escaped the dangers of the sea, and had fled for refuge to O'Donnell, O'Neill, and O'Rourke, all of whom were very favourable to them; but the Lord Deputy, for his own ends, greatly exaggerated both their numbers and strength. They were merely fugitives acting on the defensive, and not then[22] inclined to be aggressive. They well knew the fate of hundreds of their countrymen, and what they might expect if they fell into the hands of the Lord Deputy.

THE SPANIARDS HOLDING ROSSCLOGHER

CASTLE AGAINST THE LORD DEPUTY.

In the County of Clare, at this time, was another MacClancy—Boethius. He was Elizabeth's High Sheriff there, and, unlike his namesake of Rossclogher, he cruelly treated and killed a number of Spaniards of the Armada, who had been shipwrecked off that coast. In memory of his conduct then, he is cursed every seventh year in a church in Spain. In the State Papers no reference is made to this expedition against MacClancy's castle; all that is said is that troops arrived at Athlone on 10th November, 1588, and returned to Dublin on 23rd December following, "without loss of any one of her Majesty's army; neither brought I home, as the captains inform me, scarce twenty sick persons or thereabouts; neither found I the water, nor other great impediments which were objected before my going out, to have been dangerous, otherwise than very reasonable to pass." In these vague terms Fitzwilliam disposes of a disagreeable subject which he knew was more for his own credit not to enlarge upon. It seems probable that Cuellar has over-estimated the number of soldiers sent to storm the castle which he was defending; there is, however, no ground for doubting the general truth of his account of the transaction. MacClancy, we know, was the subject of peculiar hatred by the authorities; Bingham describes him as "an arch-rebel, and the most barbarous creature in Ireland," and the fact of his having given shelter to Spanish fugitives made him ten times worse in their eyes.

Fitzwilliam, the Lord Deputy, whom Cuellar styles the "Great Governor," was a covetous and merciless man. Not long after his arrival in Ireland, the Spanish shipwrecks took place, and the rumours of the great amount of treasure and valuables which the Spaniards were reported to have with them called into prominence the most marked feature in the Lord Deputy's character—cupidity. His commission shows this: "To make by all good means, both of oaths and otherwise [this means by torture], to take all hulls of ships, treasures, etc., into your hands, and to apprehend and execute all Spaniards of what quality soever ... torture may be used in prosecuting this enquiry."

In the State Papers, at December 3, 1588—Sir R. Bingham to the Queen—the following reference to the Lord Deputy's expedition to the North of Ireland is made: "But the Lord Deputy, having further advertisements from the North of the state of things in those parts, took occasion to make a journey thither, and made his way[23] through this province [Connaught], and in passing along caused both these two Spaniards, which my brother [George Bingham] had, to be executed." One of these was Don Graveillo de Swasso. At December 31st, the Lord Deputy thus refers to his movements: "At my coming to the Castles of Ballyshannon and Beleek, which stand upon the river Earne, and are in possession of one Sir Owen O'Toole, alias O'Gallagher[5], a principal man of that country, I found all the country [people] and cattle fled into the strong mountains and fastnesses of the woods in their own countrie and neighbours adjoining, as O'Rourke, O'Hara, the O'Glannaghies [MacClancy], Maguires, and others." In the State Papers, 15th October, 1588, we learn some curious particulars concerning the wreck of one of the Spanish ships, named La Trinidad Valencera, at Inisowen (O'Doherty's country). This vessel, which was a very large one (1,100 tons), carried 42 guns and 360 men, including soldiers and mariners, many of whom were drowned. They had only one boat left, and this a broken one, in which they succeeded in landing a part of the crew. Some swam to shore, and the rest were landed in a boat they bought from the Inisowen men for 200 ducats. Some curious details are given of how the Spaniards fared on land. When first they came ashore, with only their rapiers in their hands, they found four or five "savages," who bade them welcome, and well-used them: afterwards, some twenty more "wild men" came to them, and robbed them of a money-bag containing 1,000 reals of plate and some rich apparel. The only food they could obtain was horse-flesh, which they bought from the country people, as well as a small quantity of butter. When they had been about a week living here, Fitzwilliam's men came on the scene, as also O'Donnell and his wife. The Spaniards surrendered to the captains that carried "the Queen's ensigns," the conditions being that their lives should be spared till they appeared before the Lord Deputy, and be allowed to take with them a change of apparel from the stores of their own ship. These conditions were not adhered to, and the soldiers and natives were allowed to spoil and plunder the shipwrecked Spaniards. The O'Donnell above referred to was the father of the celebrated Red Hugh, who was at this period within the walls of Dublin Castle, a close prisoner. "O'Donnell's wife" was the celebrated Ineen Dubh, the mother of Red Hugh. O'Donnell felt himself weak and unable to cope with the English power, which was surrounding him on all sides. While not taking an active part in[24] maltreating the Spaniards, who had been thrown on his territory by the violence of the storms, he was guilty in a passive way of permitting them to be ill-used; and when, a short time after these events, he resigned the government of Tirconnell to the more capable hands of his son, Red Hugh, and retired to the solitude of the cloister, the greatest sin which weighed on his conscience was his cruel conduct in slaying a number of Spanish seamen in Inisowen, which act was instigated by the Lord Deputy.

MacClancy at length paid dearly for his part in the Spanish affair. This we learn from a letter in the State Papers, under date 23rd April, 1590: "The acceptable service performed by Sir George Bingham in cutting off M'Glanaghie, an arch-rebel ... M'Glanaghie's head brought in. M'Glanaghie ran for a lough, and tried to save himself by swimming, but a shot broke his arm, and a gallowglass brought him ashore. He was the most barbarous creature in Ireland; his countrie extended from Grange till you come to Ballishannon; he was O'Rourke's right hand; he had fourteen Spaniards with him, some of whom were taken alive." The lough above referred to is Lough Melvin. MacClancy was endeavouring to reach his fortress when he met his end. O'Rourke, shortly after these events, fled to Scotland, where he was arrested, brought to London, arraigned on a charge of high treason, found guilty, and hanged. At the place of execution he was met by the notorious Myler M'Grath, that many-sided ecclesiastic, whose castle walls, near Pettigo, still keep his name in remembrance. M'Grath endeavoured to make him abjure his faith, but O'Rourke could not be shaken; he knew the sordid character of the man, and bitterly reproached him for his own mercenary conduct.

When the siege was raised, MacClancy and his followers returned from the mountains, and made much of Cuellar and his comrades, asking them to remain and throw in their lot with them. To Cuellar he offered his sister in marriage. This, however, the latter declined, saying he was anxious to turn his face homewards. MacClancy would not hear of the Spaniards leaving; and Cuellar, fearing he might be detained against his will, determined to leave unobserved, which he did two days after Christmas, when he and four Spanish soldiers left the castle before dawn, and went "travelling by the mountains and desolate places," and at the end of twenty days they came to Dunluce, where Alonzo de Leyva, and the Count de Paredes, and many other Spanish nobles had been lost; and there, he says, "they went to the huts of some 'savages,' who told us of the great misfortunes of our people who were drowned."

Cuellar does not indicate the course he took in travelling on foot from the castle in Lough Melvin to Dunluce; but it is evident, from the time spent on the journey, that it was the circuitous route round the coast of Donegal to Derry, and from thence to Dunluce. Their journey was one of danger, as military scouts were searching the country everywhere for Spaniards, and more than once he had narrow escapes. After some delay and considerable difficulty, Cuellar, through the friendly assistance of Sir James MacDonnell, of Dunluce, succeeded in crossing over to Scotland, in company with seventeen Spanish sailors who had been rescued by MacDonnell. He hoped to enjoy the protection of King James VI., who was then reported to favour the Spaniards.

Cuellar did not find things much better there, and, after some delay, he eventually took ship and arrived at Antwerp. His narrative is dated October 4, 1589, and was evidently not written till his arrival on the Continent. In forming an estimate of its value, it should be remembered that the greater part, if not all, was written by him from memory. It is highly improbable he would have made notes, or kept a diary in Ireland, as the writing of his adventures never occurred to him (as his narrative shows) till afterwards. This most probable supposition will account for any inaccuracies in his statements as to places, distances, etc.; and allowing for a natural tendency to exaggeration, Cuellar's narrative, corroborated as it is in all essential points by contemporary history, bears on its face the stamp of truth and authenticity.

The State Papers (Ireland) at this year (1588) contain several references to these wrecks on the Connaught coast.[6] Amongst them the following occur: "After the Spanish fleet had doubled Scotland, and were in their course homewards, they were by contrary weather driven upon the several parts of this province [Connaught] and wrecked, as it were, by even portions—three ships in every of the four several counties bordering on the sea coasts, viz., in Sligo, Mayo, Galway, and Thomond:—so that twelve ships perished on the rocks and sands of the shore-side, and some three or four besides to seaboard of the out-isles, which presently sunk, both men and ships, in the night-time. And so can I say by good estimation that six or seven thousand men have been cast away on these coasts, save some 1,000 of them which escaped to land in several places where their ships fell, which sithence were all put to the sword." Of all the ships[26] which composed the Armada, none was a greater object of interest than the Rata, a great galleon commanded by Don Alonzo de Leyva. This officer was Knight of Santiago and Commendador of Alcuesca: a remarkable man, of invincible courage and perseverance, who was destined to meet a watery grave on this expedition. It is said that King Philip felt more grief for his death than for the loss of the whole fleet.

In the Rata were hundreds of youths of the noblest families of Castile, who had been committed to De Leyva's care. Having cleared the northern coast of Scotland and gained the Atlantic, he kept well out to sea, and in the early part of the month of September doubled Erris Head, on the western coast of Mayo, after which he and another galleon came to anchor in Blacksod Bay. Here he sent in a boat, with fourteen men, to ascertain the disposition of the natives, whether friendly or the reverse. Having landed, they soon encountered one of the petty chiefs—Richard Burke by name, familiarly known as the "Devil's Son." This man, true to his character, robbed and maltreated them. Immediately after this a violent storm sprang up, which proved fatal to many of the Spanish ships then off the Irish coast: the Rata broke loose from her anchors, and ran ashore; De Leyva and his men were only able to escape with their lives, carrying with them their arms and any valuables they could lay hold of. They set fire to the Rata; and perceiving hard by an old castle, within it they took up their quarters. The "Devil's Son" and his followers made their way to the wreck, plundering any of the rich garments and stores which they could snatch from the flames. At this juncture, Bryan-na-Murtha O'Rourke, Prince of Breffney, hearing of the abject condition of the Spaniards, sent them immediate assistance, and an invitation to their commander, De Leyva, to come to his castle at Dromahair. There they were well entertained, comfortably clothed, and provided with arms. This is referred to in the Irish State Papers thus: "Certain Spaniards being stript were relieved by Sir Brian O'Rourke, apparelled, and new furnished with weapons."

O'Rourke, whose power and popularity were very great, was a dangerous foe to the Governor of Connaught, who was unable to make him pay the "Queen's Rent." His action in harbouring and succouring the Spaniards, and for a short space enlisting them in his service, had, as shall be seen further on, important results in his approaching downfall. De Leyva resolved, after some time, to quit the country, and to embark his men in the other galleon, the San Martin, which had been able to hold out in the offing. Having made[27] sail, and on their way fallen in with the Girona and another ship—a galliass—they endeavoured to clear Rossan Point; but the sea being still very rough and the wind unpropitious, they were obliged to make for Killybegs. Having reached the entrance to that port, the two larger vessels went on the rocks, and became wrecks; the galliass continued to float, though badly injured; the crews and soldiers, numbering two thousand, were got ashore with their arms, but no provisions were saved.

The State Papers [September, 1588] say that "John Festigan, who came out of the barony of Carbrie [of which Streedagh strand forms a part], saw three great ships coming from the south-west, and bearing towards O'Donnell's country, and took their course right to the harbour of Killybegs, the next haven to Donegal." And in the examination of a Spanish sailor named Macharg,[7] the following reference appears: "After the fight in the narrow sea, she fell upon the coast of Ireland in a haven called 'Erris St. Donnell,' where, at their coming in, they found a great ship called the Rata, of 1,000 tons or more, in which was Don Alonzo de Leyva. After she perished, Don Alonzo and all his company were received into the hulk of St. Anna, with all the goods they had in the ships of any value; as plate, apparel, money, jewels, and armour, leaving behind them victual, ordnance, and much other stuff, which the hulk was not able to carry away." It will be seen from the above that it is stated that it was in the St. Anna De Leyva embarked, after the loss of his own vessel; but it would appear from "La Felicissima Armada" that it was in the San Martin they took ship, and afterward removed to the Duquesa Santa Anna.

The number of wrecks of the Spanish vessels on the Irish coast was largely due to the insufficiency of their anchor-gear; and in explanation of this, it may be observed that it was chiefly hempen cables which were then in use; and even in the largest vessels substantial chain cables had not been adopted.

It would seem that when De Leyva had reached "O'Donnell's country," he found the San Martin so much injured and in such a leaky condition, that he abandoned her and placed his men and valuables in the Duquesa Santa Anna, which, through the friendly aid of O'Neill and McSwine, he was enabled to repair. After obtaining fresh stores of provisions from the people of Tirconnell, De Leyva once more put to sea; but misfortune still followed in his track, and the Santa Anna[28] ran on the rocks in Glennageveny Bay, a few miles west of Inisowen Head. Still undaunted, De Leyva, though now sorely wounded in escaping from the wreck, made another effort. The Girona, which had also been patched up while at Killybegs, lay at anchor in a creek in McSwine's territory, about twenty miles distant from where he now was. In the Girona he determined to sail, and being unable to walk or ride had himself carried across country, the remnant of his men following him—for many had been drowned. Close to the shore, in sight of that relentless sea from which they had already suffered so keenly, these belated men encamped for the space of a week, using every effort to make the Girona—their last means of escape—as tight and seaworthy as possible. They once more embarked, hoping to be able at least to reach the coast of Scotland; but their course was nearly run; and after a few days, while passing near to the Giant's Causeway, they ran on a rock, and in a few minutes were dashed to pieces. It is said every soul on board except five sailors—nobles, mariners, soldiers, and slaves (who were kept as rowers)—were lost. The actual spot of the wreck pointed to by tradition still bears the name of "Spaniard Rock" the western head of Port-na-Spaniagh.

WRECK OF A GALLEON AT PORT-NA-SPANIAGH,

NORTH COAST OF ANTRIM, SEPTEMBER, 1588.

The State Papers (Ireland, 1588) contain the following reference to this event: "The Spanish ship [the Girona] which arrived in[29] Tirconnell with the McSweeny, was on Friday, the 18th of this present month [Oct., 1588], descried over against Dunluce, and by rough weather was perished, so that there was driven to the land, being drowned, the number of 260 persons, with certain butts of wine, which Sorely Boy [MacDonnell] hath taken up for his use." There was another of the Spanish ships wrecked near Dunluce, but the name of the vessel is unknown. From this wreck the MacDonnells recovered three pieces of cannon, which were subsequently claimed by Sir John Chichester for the Government. These cannon were mounted on Dunluce Castle, and MacDonnell refused to give them up. He had also rescued eleven sailors from this wreck, as well as the five from the Girona. These he all took under his protection, and eventually sent them over in a boat to Scotland, from whence they made their way home. From the depositions of an Irish sailor named McGrath, who was on board the Girona, it appears that vessel went aground on a long, low reef of rock at the mouth of the Bush river, which reef was then known as the "Rock of Bunbois."

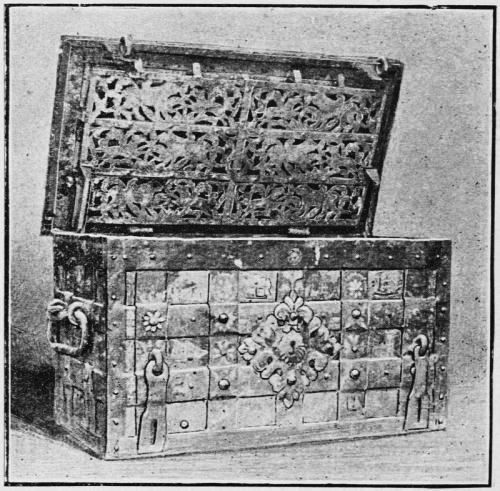

Of the authentic relics of the Armada, those which have attracted most attention, and been the subject of most controversy, are the iron chests. That there are a greater number of these chests still preserved in Ireland than could reasonably be assumed to have belonged to the Spanish vessels which perished on the Irish coast, cannot be denied; nevertheless, it is a mistake which some writers on the subject have fallen into, in supposing that no such chests were in the Spanish vessels, and that they are a mere popular fiction, as their introduction into Ireland must have been at least a century later than the Armada period. The writer has been at pains to obtain from the most trustworthy sources, both in this country and in England, all the information possible, and the result is here summarized. Having examined specimens of these treasure-chests in South Kensington and elsewhere, belonging to the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries, from the earliest chest downwards, the same features are apparent in their construction and ornamentation. They were by no means peculiar to Spain, but were the typical and recognised receptacles for valuables all over the Continent of Europe for many centuries.[8] In Ireland these chests were in use in the time of the O'Donnells, and were doubtless brought over in the vessels which were frequently trading between the ports of Tirconnell and the Brabant Marts. Within the past half-century, while some clay was[30] being turned up and removed from the precincts of O'Clery's Castle, at Kilbarron, near Ballyshannon, the lid of one was discovered with the intricate system of bolts and levers attached. This is now in the custody of the writer, having been kindly lent to him by the owner, General Tredennick, Woodhill, Ardara. When brought to light, it was supposed to have been the lock of the chief entrance to O'Clery's stronghold, and continued to be so regarded till identified by the writer as a portion of a fifteenth-century coffer. This discovery proves beyond question that these chests were in use in Ireland, whether brought over in Spanish or other vessels, at a much earlier date than some have supposed. The lid found at O'Clery's Castle, it is reasonable to infer, belonged to a chest which was used by the historians of Tirconnell for the safe keeping of their valuable manuscripts and other articles; and, looking to the fact that their house and property were confiscated within a period of twenty years or so after the Spanish wrecks, and that Kilbarron was then plundered and dismantled, there can be no doubt that the chest in question belonged to the period when the O'Clerys flourished in their rock-bound fortress. The lid itself offers a curious bit of evidence of its past history: a portion of one of the hinges remains attached, showing that it had been wrenched off with violence, and that the chest to which it belonged had been forced by some plundering enemy who had not possession of the master-key, which actuated all the bolts of the lock. A similar lid was found in the ruins of O'Donnell's Castle at Donegal, and is still in existence in this neighbourhood.

A SPANISH TREASURE-CHEST.

There is in the possession of W. E. Kelly, Esq., St. Helen's, Westport, Co. Mayo (to whom the writer is indebted for the information), a very interesting treasure-chest, which bears satisfactory evidence of having been recovered from one of the Armada ships wrecked on that coast in 1588. After "the flight of the Earls," a branch of the O'Donnells migrated from Tirconnell to Newport, Co. Mayo, and one of the family—Conel O'Donnell, brother of Sir Neal O'Donnell—obtained from a peasant, who lived on the sea-shore at Clew Bay, the chest in question. No particulars are forthcoming as to the exact spot where the peasant found it; but it bears evidence, from its corrosion, of having been subjected to the prolonged action of sea water, and it is not unlikely that this relic was on board the Rata, which De Leyva set fire to in Blacksod Bay. The size of the chest is 2 ft. 10 1⁄2 ins. long, 1 ft. 9 ins. wide, and 1 ft. 7 1⁄2 ins. high.

In the Armada Exhibition, at Drury Lane, held October, 1888, the following amongst other relics were shown:

"No. 240.—Spanish treasure-chest, with two keys; the larger key is emblematical, the bow being the ecclesiastical A.N., the wards being 'chevron' and 'cross.' Inside of chest has engraved face-plate to lock, perforated with Spanish eagles for design.

"No. 241.—Spanish treasure-chest, believed to have come out of the Santa Anna, etc.

"No. 242.—Iron chest from Armada. This chest is of most remarkable construction: there is an apparent keyhole, but the real one is concealed in the lid, which is one large lock, the lock-plate of which is of very fine workmanship of polished iron.

"No. 243.—Iron treasure-chest, taken from the Spanish war-ship during the fight with the Armada.

"Spanish matchlock, taken from a Spaniard on the coast of Ireland.

"Spear head, from one of the Armada ships, wrecked off the coast of Donegal.

"A spoon of curious floral design, found on the shore close to Dunluce Castle, about 90 years ago [supposed to be from the wreck of the Girona.]"[9]

Turning to Cuellar's narrative, in speaking of the wrecks at Streedagh, Co. Sligo, of which he was an eye-witness, the following occurs:[10] "And then [the Irish] betook themselves to the shore to plunder and break open money chests." These are called in Spanish Arcas, i.e., iron chests with flat lids to hold money, etc.

In the State Papers (Ireland, 1588) several references to money chests in the Spanish ships appear. "Plate and ducats" are spoken of as being "rifled out of their chests." At 2nd Aug., 1588 [examination of Spanish prisoners], from the "Nuestra Señora del Rosario," "a chest of the King's was taken wherein was 52,000 ducats, of which chest Don Pedro de Valdez had one key and the King's treasurer or the Duke another. Besides [it is added], many of the gentlemen had good store of money aboard the said ship; also, there was wrought plate and a great store of precious jewels and rich apparel."

In State Papers [4th and 5th August, 1588], in describing the capture of a Spanish "Carrack"—the San Salvador—it is said: "This very night some inkling came unto us that a chest of great weight should be found in the fore-peak of the ship," etc. These and many other references to both treasure and treasure-chests, taken from contemporary sources, show that the Spanish treasure-chests are not mythical, but formed a necessary part of the outfit of an expedition, on which those who had entered had staked all their riches and had brought their valuables with them. A fine specimen of the treasure-chest is in the possession of Major Hamilton, Brownhall. It has been in his family for such a period that its history is lost. The ornamental open-work of polished steel, which covers the inside of lid, is a very fine specimen of mediæval iron work.

In Western Tirconnell is a cluster of islands which, collectively, are called The Rosses. About four and a half miles north-west of Mullaghderg are the "Spanish Stags" or "Enchanted Ships." On this wild and rocky coast, abounding in shoals and sunken rocks, one of the Spanish ships was cast away. Here lies buried in the sand the remains of one of them. A little more than a century ago, an expedition of young men, whose imagination was heated by the traditional accounts of buried treasure, set out in a boat to the Spanish rock, and being good divers and expert swimmers, they succeeded in reaching the wreck. They got on the upper deck, and were able by great effort and perseverance to recover a quantity of lead: they raised a number of brass guns, some of which were 10 feet[33] long. These were broken up and sold as scrap metal at 4 1⁄2d. per lb. The iron guns, of which they found a number, were left in the water. This vessel, tradition says, was a treasure ship; at all events, a number of Spanish gold coins were found, and were in existence some years ago. The brass cannon which were found bore the Spanish arms. It is said some of the Spaniards from this vessel escaped to land, and spent the rest of their lives amongst the Irish in The Rosses.

Anchor of Spanish Galleon

In the spring of 1895, an attempt was made to search for the remains of this ship. A small steamer, called the Harbour Lights, visited the spot, and remained for a fortnight, but without being able to accomplish anything. Owing to the accumulation of sand, which now covers the wreck, there are great obstacles in the way of reaching it. At about a distance of two miles to the south of the "Spanish Rock" another vessel was wrecked, in the Bay of Castlefort, inside of the North Island of Aran. In 1853, the coastguards at Rutland, under the superintendence of their chief officer, Mr. Richard Heard, and at the instance of Admiral Sir Erasmus Ommanney, C.B., who was on a tour of inspection in that year, had their attention directed to the wreck. The search was rewarded by the recovery of a fine anchor, which was forthwith transmitted to London, and presented by the Admiral to the United Service Institution, Whitehall Place. Through the kindness of Sir Erasmus Ommanney, an engraving[11] of this interesting relic is presented, and the writer is also indebted to[34] him for the particulars of the discovery of the anchor. A portion of one of the brass cannon recovered from the Girona was in Castlecaldwell Museum, till the collection was disposed of. The fine figurehead of one of the ships wrecked off Streedagh, which is shown on the first page, is the only existing specimen in Ireland. In the Parish Church of Carndonagh is a bell, which tradition says was recovered from an Armada vessel wrecked at Inishowen. It bears the following legend: "Sancta: Maria: Ora: Pro: Nobis Ricardus Pottar [his sign or trade mark] De Vruain Me Fecit Alla [Allelujah]."

The following are the names of the Spanish vessels lost on the coasts of Ulster and Connacht, so far as they are known (several nameless vessels were also cast away):

| Duquesa Santa Anna | 900 | tons. |

| The Rata | 820 | " |

| The San Martin | — | |

| El Gran Grifon, Capitana | 650 | " |

| The Girona | — | |

| The San Juan | 530 | " |

| La Trinidad Valencera | 1,100 | " |

In the valuable work, entitled "State Papers relating to the Defeat of the Spanish Armada, Anno 1588," by Professor Laughton (Navy Records Society)—a work which throws much light on the history of the period, and should be studied in connection with Captain Duro's book—the following remarks are made as to the cause of the loss of so many Spanish vessels: "The Spanish ships were lost partly from bad pilotage, partly from bad seamanship, but chiefly because they were leaking like sieves, had no anchors, their masts and rigging shattered, their water casks smashed."

The actual numbers when the fleet sailed from the Tagus on the 20th May were: 130 ships, 57,868 tons, 2,431 guns, 8,050 seamen, 18,973 soldiers, 1,382 volunteers, 2,088 slaves (as rowers).

1. Amongst those drowned at the wrecks on Streedagh were the following Irishmen: Brian Mac-in-Persium, Andrew Mac-in-Persium, and Cormac O'Larit, all of whom had shipped as sailors in the Spanish vessels.

2. See Translator's Preface for the sense in which the word "north" is used in Spanish.

3. See O'Donovan's Letters (Sligo, R.I.A.)

4. Santiago, the Patron Saint of Spain; hence it became the war-cry or watchword when going to battle.

5. Sir Owen O'Gallagher was O'Donnell's Marshal, and lived in the Castle of Ballyshannon at this period.

6. Sir R. Bingham to Walsyngham, Oct. 1st, 1588.

7. Duro, p. 98; 25, i.

8. Chests of the same type, called Arca, were discovered in the excavations at Pompeii, where they were used for keeping the public money.

9. From the Official Catalogue of Tercentenary Exhibition of Spanish Armada.

10. See Mr. Crawford's translation and relative note, Part II.

11. From a photograph kindly taken by T. B. M'Dowell, Esq., London.

Shortly after the publication in Madrid of the second volume of Captain Duro's book—"La Armada Invencible"—the Earl of Ducie drew special attention to it in an article which appeared in the number of the Nineteenth Century for September, 1885.

Subsequently Mr. Froude took up the subject, and discoursed upon it in Longman's Magazine for September, October, and November, 1891, giving a general sketch of the salient features of the ill-fated expedition from the Spanish point of view, as disclosed in the pages of the book in question.

These glowing pictures aroused much public interest at the time; but they were especially attractive to those persons who happened to combine the conditions of possessing antiquarian tastes, and living near the localities brought into prominence by the recital of the great disasters which befel the "Invincible Armada."

Of all the exciting scenes in that eventful episode in our history, none was more tragic than the wreck of three of the largest of the Spanish ships, which took place, simultaneously, in the bay of Donegal, on the north-west coast of Ireland, in September, 1588.

The fact that in Captain Duro's book there appeared a hitherto unpublished narrative of the event, written at the time by Don Francisco Cuellar, one of the survivors of the catastrophe, and giving a minute account of his wanderings and adventures in the country where he was cast away, contributed to increase the local interest in the matter.

Mr. Hugh Allingham at once began a series of exhaustive investigations in relation to Cuellar's descriptions, the results of which he subsequently placed before the public in the pages of the Ulster Journal of Archæology, April, 1895.

It was solely with the object of assisting him in the researches he then undertook that this translation was prepared, and there was no intention at the time of any future publication of it.

It was a matter of importance to facilitate the process of identification as regards the various localities referred to, as well as to avoid the danger of misinterpreting the writer's meaning when dealing with obscure passages; conditions requiring the translation to be as literal as possible, and leaving the translator with but little freedom in[40] treating a language that at best does not lend itself easily to reproduction in the English idiom.

These facts are mentioned to account for the style in which it has been prepared, as it has no pretensions to merit, except in so far as care has been taken to follow closely the wording of the original Spanish.

As Mr. Allingham is now about to publish a new edition of his "Spanish Armada in Ulster and Connacht," it has been considered desirable that this translation should be added to it in extenso for the convenience of reference. I have, therefore, gone carefully over it again, comparing it with the Spanish text, and have made some slight alterations of an occasional word or phrase in it to make the matter more explicit.

This will explain why in some of Mr. Allingham's quotations from the original translation, as given in the first edition of his paper on this subject, a word here and there may be found to differ from those contained in the present version; but the change does not affect the sense or meaning of any passage, with, I think, a couple of exceptions.

The first of these relates to where Cuellar describes the English as going about searching "for us who had escaped [from the perils of the sea. All the monks had fled] to the woods," etc. The part within the brackets was left out in the original translation by the accidental omission of a line in copying the rough draft; and, as the mutilated sentence still made sense, the omission was not detected at the time.

The other is the only really important change, and I will now proceed to deal with it.

The Spanish words are: "Hacienda Norte de las montañas," which I originally translated as "making for the north of the mountains"; but now prefer to render by the alternative reading: "Making for the direction of the mountains."

I will first show that this latter translation is also perfectly correct, and that I am justified in adopting it, and then explain my reason for doing so.

In Spanish dictionaries generally the meaning of Norte is given, primarily, as North, signifying either the Arctic pole, the northern part of the sphere, the polar star, the north wind, etc.; but it is also used in another and metaphorical sense.

In the best authority we have on such matters—the Dictionary of the Spanish Academy—we find that Norte also means direction, guide, "the allusion being taken from the North Star, by which navigators guide themselves with the direction of the nautical needle" [or[41] mariner's compass]. With such an authority to support me, I think it can scarcely be disputed that the alternative translation, which I recommend, is a fair one.

I will now explain why I prefer it to my first reading of the passage. Cuellar's statement leaves no room for doubt that it was to O'Rourke's country, lying along and to the south of the Leitrim range of mountains, he was bound; while Mr. Allingham's investigations make it equally certain, in my opinion, that Glenade was the particular place Cuellar came to, as described in his account of his wanderings.

Now, as Glenade is among the Leitrim mountains, not on their northern side—along which, in the first instance, I had supposed Cuellar's route to lie—it became necessary for me to re-examine my position and make sure whether the Spanish text required a rigid adherence to my first translation, or might admit of some alternative reading that would account for the apparent discrepancy.

The result was, as already explained, that the pages of the dictionary disclosed a perfectly easy and admissible treatment of the passage in question, that solved the difficulty without the necessity of resorting to any postulates, or putting a forced or novel interpretation upon the words.

Here, perhaps, I should refer to the fact that two other translators of Cuellar's narrative—Professor O'Reilly in the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, December, 1893, and Mr. Sedgwick in a small volume recently published by Mr. Elkin Mathews, of Vigo Street, London—give this passage a very different meaning to that which I attach to it, while they agree tolerably closely with each other.

Professor O'Reilly omits all mention of the mountains, and translates only the rest of the sentence, as: "Taking the northerly direction pointed out by the boy"; while Mr. Sedgwick puts it in this form: "Striking north for the mountains the boy had pointed out."

This latter reading gives the preposition (de) exactly the opposite signification to that which it usually bears.

But, apart from this, there is another and, I think, a fatal objection to the two foregoing translations of the phrase.

Both agree that the boy told Cuellar to go straight on to mountains, pointed out by him, as the place behind which O'Rourke lived. If so, these mountains could not have been situated to the north of where he was at the time, as to go from thence in anything like a northerly direction would have brought him at once into the sea, which lay to the north of him, and extended for several miles farther eastwards.

That this fact must have been apparent to both Cuellar and his guide as they went along will be recognised by those who are acquainted with the locality, which everywhere looks down upon the ocean.

There is another rather important point upon which I differ from the two gentlemen already named, who here again agree closely with each other. It relates to the position of the village in which MacClancy's retainers lived. Cuellar says it was established upon "tierra firme," which one translates as firm, the other as solid, ground. To me the context appears to indicate clearly that the expression was intended to bear its ordinary idiomatic interpretation of mainland in contradistinction to the position of the castle itself, which we are told was built in the lake.