TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

MENTAL EVOLUTION IN MAN

By the same Author.

Crown 8vo. 5s.

JELLY-FISH, STAR-FISH, AND SEA-URCHINS.

Being a Research on Primitive Nervous Systems.

[International Scientific Series.

Crown 8vo. 5s.

ANIMAL INTELLIGENCE.

Fourth Edition.

[International Scientific Series.

Demy 8vo. 12s.

MENTAL EVOLUTION IN ANIMALS.

Second Thousand.

With a Posthumous Essay on Instinct by

Charles Darwin, F.R.S.

London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co.

MENTAL EVOLUTION IN MAN

ORIGIN OF HUMAN FACULTY

BY

GEORGE JOHN ROMANES, M.A., LL.D., F.R.S.

LONDON

KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH & CO., 1, PATERNOSTER SQUARE

1888

(The rights of translation and of reproduction are reserved.)

PREFACE.

In now carrying my study of mental evolution into the province of human psychology, it is desirable that I should say a few words to indicate the scope and intention of this the major portion of my work. For it is evident that “Mental Evolution in Man” is a subject comprehending so enormous a field that, unless some lines of limitation are drawn within which its discussion is to be confined, no one writer could presume to deal with it.

The lines, then, which I have laid down for my own guidance are these. My object is to seek for the principles and causes of mental evolution in man, first as regards the origin of human faculty, and next as regards the several main branches into which faculties distinctively human afterwards ramified and developed. In order as far as possible to gain this object, it has appeared to me desirable to take large or general views, both of the main trunk itself, and also of its sundry branches. Therefore I have throughout avoided the temptation of following any of the branches into their smaller ramifications, or of going into the details of progressive development. These, I have felt, are matters to be dealt with by others who are severally better qualified for the task, whether their special studies have reference to language, archæology, technicology, science, literature, art, politics, morals, or religion. But, in so far as I shall subsequently have to deal with these subjects, I will do so with the purpose of arriving at general principles bearing upon mental evolution, rather than with that of collecting facts or opinions for[vi] the sake of their intrinsic interest from a purely historical point of view.

Finding that the labour required for the investigation, even as thus limited, is much greater than I originally anticipated, it appears to me undesirable to delay publication until the whole shall have been completed. I have therefore decided to publish the treatise in successive instalments, of which the present constitutes the first. As indicated by the title, it is concerned exclusively with the Origin of Human Faculty. Future instalments will deal with the Intellect, Emotions, Volition, Morals, and Religion. It will, however, be several years before I shall be in a position to publish these succeeding instalments, notwithstanding that some of them are already far advanced.

Touching the present instalment, it is only needful to remark that from a controversial point of view it is, perhaps, the most important. If once the genesis of conceptual thought from non-conceptual antecedents be rendered apparent, the great majority of competent readers at the present time would be prepared to allow that the psychological barrier between the brute and the man is shown to have been overcome. Consequently, I have allotted what might otherwise appear to be a disproportionate amount of space to my consideration of this the origin of human faculty—disproportionate, I mean, as compared with what has afterwards to be said touching the development of human faculty in its several branches already named. Moreover, in the present treatise I shall be concerned chiefly with the psychology of my subject—reserving for my next instalment a full consideration of the light which has been shed on the mental and social condition of early man by the study of his own remains on the one hand, and of existing savages on the other. Even as thus restricted, however, the subject-matter of the present treatise will be found more extensive than most persons would have been prepared to expect. For it does not appear to me that this subject-matter has hitherto received at the hands of psychologists any approach to the amount of[vii] analysis of which it is susceptible, and to which—in view of the general theory of evolution—it is unquestionably entitled. But I have everywhere endeavoured to avoid undue prolixity, trusting that the intelligence of any one who is likely to read the book will be able to appreciate the significance of important points, without the need of expatiation on the part of the writer. The only places, therefore, where I feel that I may be fairly open to the charge of unnecessary reiteration, are those in which I am endeavouring to render fully intelligible the newer features of my analysis. But even here I do not anticipate that readers of any class will complain of the efforts which are thus made to assist their understanding of a somewhat complicated matter.

As no one has previously gone into this matter, I have found myself obliged to coin a certain number of new terms, for the purpose at once of avoiding continuous circumlocution, and of rendering aid to the analytic inquiry. For my own part I regret this necessity, and therefore have not resorted to it save where I have found the force of circumstances imperative. In the result, I do not think that adverse criticism is likely to fasten upon any of these new terms as needless for the purposes of my inquiry. Every worker is free to choose his own instruments; and when none are ready-made to suit his requirements, he has no alternative but to fashion those which may.

To any one who already accepts the general theory of evolution as applied to the human mind, it may well appear that the present instalment of my work is needlessly elaborate. Now, I can quite sympathize with any evolutionist who may thus feel that I have brought steam-engines to break butterflies; but I must ask such a man to remember two things. First, that plain and obvious as the truth may seem to him, it is nevertheless a truth that is very far from having received general recognition, even among more intelligent members of the community: seeing, therefore, of how much importance it is to establish this truth as an integral part of the doctrine of descent, I cannot think that either time or[viii] energy is wasted in a serious endeavour to do so, even though to minds already persuaded it may seem unnecessary to have slain our opponents in a manner quite so mercilessly minute. Secondly, I must ask these friendly critics to take note that, although the discussion has everywhere been thrown into the form of an answer to objections, it really has a much wider scope: it aims not only at an overthrow of adversaries, but also, and even more, at an exposition of the principles which have probably been concerned in the “Origin of Human Faculty.”

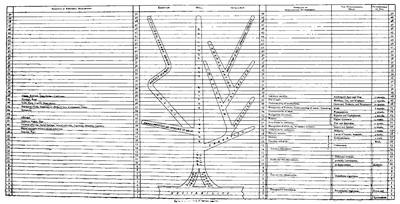

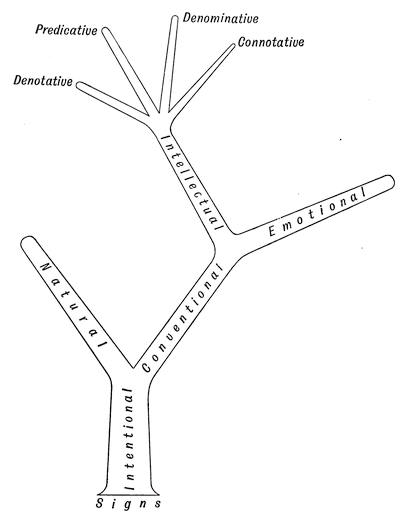

The Diagram which is reproduced from my previous work on “Mental Evolution in Animals,” and which serves to represent the leading features of psychogenesis throughout the animal kingdom, will reappear also in succeeding instalments of the work, when it will be continued so as to represent the principal stages of “Mental Evolution in Man.”

18, Cornwall Terrace, Regent’s Park,

July, 1888.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Man and Brute | 1 |

| II. | Ideas | 20 |

| III. | Logic of Recepts | 40 |

| IV. | Logic of Concepts | 70 |

| V. | Language | 85 |

| VI. | Tone and Gesture | 104 |

| VII. | Articulation | 121 |

| VIII. | Relation of Tone and Gesture to Words | 145 |

| IX. | Speech | 163 |

| X. | Self-Consciousness | 194 |

| XI. | The Transition in the Individual | 213 |

| XII. | Comparative Philology | 238 |

| XIII. | Roots of Language | 264 |

| XIV. | The Witness of Philology | 294 |

| XV. | The Witness of Philology—continued | 326 |

| XVI. | The Transition in the Race | 360 |

| XVII. | General Summary and Concluding Remarks | 390 |

MENTAL EVOLUTION IN MAN.

CHAPTER I.

MAN AND BRUTE.

Taking up the problems of psychogenesis where these were left in my previous work, I have in the present treatise to consider the whole scope of mental evolution in man. Clearly the topic thus presented is so large, that in one or other of its branches it might be taken to include the whole history of our species, together with our pre-historic development from lower forms of life, as already indicated in the Preface. However, it is not my intention to write a history of civilization, still less to develop any elaborate hypothesis of anthropogeny. My object is merely to carry into an investigation of human psychology a continuation of the principles which I have already applied to the attempted elucidation of animal psychology. I desire to show that in the one province, as in the other, the light which has been shed by the doctrine of evolution is of a magnitude which we are now only beginning to appreciate; and that by adopting the theory of continuous development from the one order of mind to the other, we are able scientifically to explain the whole mental constitution of man, even in those parts of it which, to former generations, have appeared inexplicable.

In order to accomplish this purpose, it is not needful that I should seek to enter upon matters of detail in the application of those principles to the facts of history. On the contrary,[2] I think that any such endeavour—even were I qualified to make it—would tend only to obscure my exposition of those principles themselves. It is enough that I should trace the operation of such principles, as it were, in outline, and leave to the professed historian the task of applying them in special cases.

The present work being thus a treatise on human psychology in relation of the theory of descent, the first question which it must seek to attack is clearly that as to the evidence of the mind of man having been derived from mind as we meet with it in the lower animals. And here, I think, it is not too much to say that we approach a problem which is not merely the most interesting of those that have fallen within the scope of my own works; but perhaps the most interesting that has ever been submitted to the contemplation of our race. If it is true that “the proper study of mankind is man,” assuredly the study of nature has never before reached a territory of thought so important in all its aspects as that which in our own generation it is for the first time approaching. After centuries of intellectual conquest in all regions of the phenomenal universe, man has at last begun to find that he may apply in a new and most unexpected manner the adage of antiquity—Know thyself. For he has begun to perceive a strong probability, if not an actual certainty, that his own living nature is identical in kind with the nature of all other life, and that even the most amazing side of this his own nature—nay, the most amazing of all things within the reach of his knowledge—the human mind itself, is but the topmost inflorescence of one mighty growth, whose roots and stem and many branches are sunk in the abyss of planetary time. Therefore, with Professor Huxley we may say:—“The importance of such an inquiry is indeed intuitively manifest. Brought face to face with these blurred copies of himself, the least thoughtful of men is conscious of a certain shock, due perhaps not so much to disgust at the aspect of what looks like an insulting caricature, as to the awaking of a sudden and profound mistrust of time-honoured theories and strongly[3] rooted prejudices regarding his own position in nature, and his relations to the wider world of life; while that which remains a dim suspicion for the unthinking, becomes a vast argument, fraught with the deepest consequences, for all who are acquainted with the recent progress of anatomical and physiological sciences.”[1]

The problem, then, which in this generation has for the first time been presented to human thought, is the problem of how this thought itself has come to be. A question of the deepest importance to every system of philosophy has been raised by the study of biology; and it is the question whether the mind of man is essentially the same as the mind of the lower animals, or, having had, either wholly or in part, some other mode of origin, is essentially distinct—differing not only in degree but in kind from all other types of psychical being. And forasmuch as upon this great and deeply interesting question opinions are still much divided—even among those most eminent in the walks of science who agree in accepting the principles of evolution as applied to explain the mental constitution of the lower animals,—it is evident that the question is neither a superficial nor an easy one. I shall, however, endeavour to examine it with as little obscurity as possible, and also, I need hardly say, with all the impartiality of which I am capable,[2]

It will be remembered that in the introductory chapter of my previous work I have already briefly sketched the manner in which I propose to treat this question. Here, therefore, it is sufficient to remark that I began by assuming the truth of the general theory of descent so far as the animal kingdom[4] is concerned, both with respect to bodily and to mental organization; but in doing this I expressly excluded the mental organization of man, as being a department of comparative psychology with reference to which I did not feel entitled to assume the principles of evolution. The reason why I made this special exception, I sufficiently explained; and I shall therefore now proceed, without further introduction, to a full consideration of the problem that is before us.

First, let us consider the question on purely a priori grounds. In accordance with our original hypothesis—upon which all naturalists of any standing are nowadays agreed—the process of organic and of mental evolution has been continuous throughout the whole region of life and of mind, with the one exception of the mind of man. On grounds of analogy, therefore, we should deem it antecedently improbable that the process of evolution, elsewhere so uniform and ubiquitous, should have been interrupted at its terminal phase. And looking to the very large extent of this analogy, the antecedent presumption which it raises is so considerable, that in my opinion it could only be counterbalanced by some very cogent and unmistakable facts, showing a difference between animal and human psychology so distinctive as to render it in the nature of the case virtually impossible that the one could ever have graduated into the other. This I posit as the first consideration.

Next, still restricting ourselves to an a priori view, it is unquestionable that human psychology, in the case of every individual human being, presents to actual observation a process of gradual development, or evolution, extending from infancy to manhood; and that in this process, which begins at a zero level of mental life and may culminate in genius, there is nowhere and never observable a sudden leap of progress, such as the passage from one order of psychical being to another might reasonably be expected to show. Therefore, it is a matter of observable fact that, whether or not human intelligence differs from animal in kind, it certainly does[5] admit of gradual development from a zero level. This I posit as the second consideration.

Again, so long as it is passing through the lower phases of its development, the human mind assuredly ascends through a scale of mental faculties which are parallel with those that are permanently presented by the psychological species of the animal kingdom. A glance at the Diagram which I have placed at the beginning of my previous work will serve to show in how strikingly quantitative, as well as qualitative, a manner the development of an individual human mind follows the order of mental evolution in the animal kingdom. And when we remember that, at all events up to the level where this parallel ends, the diagram in question is not an expression of any psychological theory, but of well-observed and undeniable psychological fact, I think every reasonable man must allow that, whatever the explanation of this remarkable coincidence may be, it certainly must admit of some explanation—i.e. cannot be ascribed to mere chance. But, if so, the only explanation available is that which is furnished by the theory of descent. These facts, which I present as a third consideration, tend still further—and, I think, most strongly—to increase the force of antecedent presumption against any hypothesis which supposes that the process of evolution can have been discontinuous in the region of mind.

Lastly, it is likewise a matter of observation, as I shall fully show in the next instalment of this work, that in the history of our race—as recorded in documents, traditions, antiquarian remains, and flint implements—the intelligence of the race has been subject to a steady process of gradual development. The force of this consideration lies in its proving, that if the process of mental evolution was suspended between the anthropoid apes and primitive man, it was again resumed with primitive man, and has since continued as uninterruptedly in the human species as it previously did in the animal species. Now, upon the face of these facts, or from a merely antecedent point of view, such appears to me, to say[6] the least, a highly improbable supposition. At all events, it certainly is not the kind of supposition which men of science are disposed to regard with favour elsewhere; for a long and arduous experience has taught us that the most paying kind of supposition which we can bring with us into our study of nature, is that which recognizes in nature the principle of continuity.

Taking, then, these several a priori considerations together, they must, in my opinion, be fairly held to make out a very strong primâ facie case in favour of the view that there has been no interruption of the developmental process in the course of psychological history; but that the mind of man, like the mind of animals—and, indeed, like everything else in the domain of living nature—has been evolved. For these considerations show, not only that on analogical grounds any such interruption must be held as in itself improbable; but also that there is nothing in the constitution of the human mind incompatible with the supposition of its having been slowly evolved, seeing that not only in the case of every individual life, but also during the whole history of our species, the human mind actually does undergo, and has undergone, the process in question.

In order to overturn so immense a presumption as is thus erected on a priori grounds, the psychologist must fairly be called upon to supply some very powerful considerations of an a posteriori kind, tending to show that there is something in the constitution of the human mind which renders it virtually impossible—or at all events exceedingly difficult to imagine—that it can have proceeded by way of genetic descent from mind of lower orders. I shall therefore proceed to consider, as carefully and as impartially as I can, the arguments which have been adduced in support of this thesis.

In the introductory chapter of my previous work I observed, that the question whether or not human intelligence has been evolved from animal intelligence can only be dealt with scientifically by comparing the one with the other, in order to ascertain the points wherein they agree and the points[7] wherein they differ. I shall, therefore, here begin by briefly stating the points of agreement, and then proceed more carefully to consider all the more important views which have hitherto been propounded concerning the points of difference.

If we have regard to Emotions as these occur in the brute, we cannot fail to be struck by the broad fact that the area of psychology which they cover is so nearly co-extensive with that which is covered by the emotional faculties of man. In my previous works I have given what I consider unquestionable evidence of all the following emotions, which I here name in the order of their appearance through the psychological scale,—fear, surprise, affection, pugnacity, curiosity, jealousy, anger, play, sympathy, emulation, pride, resentment, emotion of the beautiful, grief, hate, cruelty, benevolence, revenge, rage, shame, regret, deceitfulness, emotion of the ludicrous.[3]

Now, this list exhausts all the human emotions, with the exception of those which refer to religion, moral sense, and perception of the sublime. Therefore I think we are fully entitled to conclude that, so far as emotions are concerned, it cannot be said that the facts of animal psychology raise any difficulties against the theory of descent. On the contrary, the emotional life of animals is so strikingly similar to the emotional life of man—and especially of young children—that I think the similarity ought fairly to be taken as direct evidence of a genetic continuity between them.

And so it is with regard to Instinct. Understanding this term in the sense previously defined,[4] it is unquestionably true that in man—especially during the periods of infancy and youth—sundry well-marked instincts are presented, which have reference chiefly to nutrition, self-preservation, reproduction, and the rearing of progeny. No one has[8] ventured to dispute that all these instincts are identical with those which we observe in the lower animals; nor, on the other hand, has any one ventured to suggest that there is any instinct which can be said to be peculiar to man, unless the moral and religious sentiments are taken to be of the nature of instincts. And although it is true that instinct plays a larger part in the psychology of many animals than it does in the psychology of man, this fact is plainly of no importance in the present connection, where we are concerned only with identity of principle. If any one were childish enough to argue that the mind of a man differs in kind from that of a brute because it does not display any particular instinct—such, for example, as the spinning of webs, the building of nests, or the incubation of eggs,—the answer of course would be that, by parity of reasoning, the mind of a spider must be held to differ in kind from that of a bird. So far, then, as instincts and emotions are concerned, the parallel before us is much too close to admit of any argument on the opposite side.

With regard to Volition more will be said in a future instalment of this work. Here, therefore, it is enough to say, in general terms, that no one has seriously questioned the identity of kind between the animal and the human will, up to the point at which so-called freedom is supposed by some dissentients to supervene and characterize the latter. Now, of course, if the human will differs from the animal will in any important feature or attribute such as this, the fact must be duly taken into account during the course of our subsequent analysis. At present, however, we are only engaged upon a preliminary sketch of the points of resemblance between animal and human psychology. So far, therefore, as we are now concerned with the will, we have only to note that up to the point where the volitions of a man begin to surpass those of a brute in respect of complexity, refinement, and foresight, no one disputes identity of kind.

Lastly, the same remark applies to the faculties of Intellect.[5][9] Enormous as the difference undoubtedly is between these faculties in the two cases, the difference is conceded not to be one of kind ab initio. On the contrary, it is conceded that up to a certain point—namely, as far as the highest degree of intelligence to which an animal attains—there is not merely a similarity of kind, but an identity of correspondence. In other words, the parallel between animal and human intelligence which is presented in my Diagram, and to which allusion has already been made, is not disputed. The question, therefore, only arises with reference to those superadded faculties which are represented above the level marked 28, where the upward growth of animal intelligence ends, and the growth of distinctively human intelligence begins. But even at level 28 the human mind is already in possession of many of its most useful faculties, and these it does not afterwards shed, but carries them upwards with it in the course of its further development—as we well know by observing the psychogenesis of every child. Now, it belongs to the very essence of evolution, considered as a process, that when one order of existence passes on to higher grades of excellence, it does so upon the foundation already laid by the previous course of its progress; so that when compared with any allied order of existence which has not been carried so far in this upward course, a more or less close parallel admits of being traced between the two, up to the point at which the one begins to distance the other, where all further comparison admittedly ends. Therefore, upon the face of them, the facts of comparative psychology now before us are, to say the least, strongly suggestive of the superadded powers of the human intellect having been due to a process of evolution.

Lest it should be thought that in this preliminary sketch of the resemblances between human and brute psychology I have been endeavouring to draw the lines with a biased hand,[10] I will here quote a short passage to show that I have not misrepresented the extent to which agreement prevails among adherents of otherwise opposite opinions. And for this purpose I select as spokesman a distinguished naturalist, who is also an able psychologist, and to whom, therefore, I shall afterwards have occasion frequently to refer, as on both these accounts the most competent as well as the most representative of my opponents. In his Presidential Address before the Biological Section of the British Association in 1879, Mr. Mivart is reported to have said:—

“I have no wish to ignore the marvellous powers of animals, or the resemblance of their actions to those of man. No one can reasonably deny that many of them have feelings, emotions, and sense-perceptions similar to our own; that they exercise voluntary motion, and perform actions grouped in complex ways for definite ends; that they to a certain extent learn by experience, and combine perceptions and reminiscences so as to draw practical inferences, directly apprehending objects standing in different relations one to another, so that, in a sense, they may be said to apprehend relations. They will show hesitation, ending apparently, after a conflict of desires, with what looks like choice or volition; and such animals as the dog will not only exhibit the most marvellous fidelity and affection, but will also manifest evident signs of shame, which may seem the outcome of incipient moral perceptions. It is no great wonder, then, that so many persons, little given to patient and careful introspection, should fail to perceive any radical distinction between a nature thus gifted and the intellectual nature of man.”

We may now turn to consider the points wherein human and brute psychology have been by various writers alleged to differ.

The theory that brutes are non-sentient machines need not detain us, as no one at the present day is likely to defend it.[6] Again, the distinction between human and brute[11] psychology that has always been taken more or less for granted—namely, that the one is rational and the other irrational—may likewise be passed over after what has been said in the chapter on Reason in my previous work. For it is there shown that if we use the term Reason in its true, as distinguished from its traditional sense, there is no fact in animal psychosis more patent than that this psychosis is capable in no small degree of ratiocination. The source of the very prevalent doctrine that animals have no germ of reason is, I think, to be found in the fact that reason attains a much higher level of development in man than in animals, while instinct attains a higher development in animals than in man: popular phraseology, therefore, disregarding the points of similarity while exaggerating the more conspicuous points of difference, designates all the mental faculties of the animal instinctive, in contradistinction to those of man, which are termed rational. But unless we commit ourselves to an obvious reasoning in a circle, we must avoid assuming that all actions of animals are instinctive, and then arguing that, because they are instinctive, therefore they differ in kind from those actions of man which are rational. The question really lies in what is here assumed, and can only be answered by examining in what essential respect instinct differs from reason. This I have endeavoured to do in my previous work with as much precision as the nature of the subject permits; and I think I have made it evident, in the first place, that there is no such immense distinction between instinct and reason as is generally assumed—the former often being[12] blended with the latter, and the latter as often becoming transmuted into the former,—and, in the next place, that all the higher animals manifest in various degrees the faculty of inferring. Now, this is the faculty of reason, properly so called; and although it is true that in no case does it attain in animal psychology to more than a rudimentary phase of development as contrasted with its prodigious growth in man, this is clearly quite another matter where the question before us is one concerning difference of kind.[7]

Again, the theological distinction between men and animals may be passed over, because it rests on a dogma with which the science of psychology has no legitimate point of contact. Whether or not the conscious part of man differs from the conscious part of animals in being immortal, and whether or not the “spirit” of man differs from the “soul” of animals in other particulars of kind, dogma itself would maintain that science has no voice in either affirming or denying. For, from the nature of the case, any information of a positive kind relating to these matters can only be expected to come by way of a Revelation; and, therefore, however widely dogma and science may differ on other points, they are at least agreed upon this one—namely, if the conscious life of man differs thus from the conscious life of brutes, Christianity and Philosophy alike proclaim that only by a Gospel could its endowment of immortality have been brought to light.[8]

Another distinction between the man and the brute which we often find asserted is, that the latter shows no signs of[13] mental progress in successive generations. On this alleged distinction I may remark, first of all, that it begs the whole question of mental evolution in animals, and, therefore, is directly opposed to the whole body of facts presented in my work upon this subject. In the next place, I may remark that the alleged distinction comes with an ill grace from opponents of evolution, seeing that it depends upon a recognition of the principles of evolution in the history of mankind. But, leaving aside these considerations, I meet the alleged distinction with a plain denial of both the statements of fact on which it rests. That is to say, I deny on the one hand that mental progress from generation to generation is an invariable peculiarity of human intelligence; and, on the other hand, I deny that such progress is never found to occur in the case of animal intelligence.

Taking these two points separately, I hold it to be a statement opposed to fact to say, or to imply, that all existing savages, when not brought into contact with civilized man, undergo intellectual development from generation to generation. On the contrary, one of the most generally applicable statements we can make with reference to the psychology of uncivilized man is that it shows, in a remarkable degree, what we may term a vis inertiæ as regards upward movement. Even so highly developed a type of mind as that of the Negro—submitted, too, as it has been in millions of individual cases to close contact with minds of the most progressive type, and enjoying as it has in many thousands of individual cases all the advantages of liberal education—has never, so far as I can ascertain, executed one single stroke of original work in any single department of intellectual activity.

Again, if we look to the whole history of man upon this planet as recorded by his remains, the feature which to my mind stands out in most marked prominence is the almost incredible slowness of his intellectual advance, during all the earlier millenniums of his existence. Allowing full weight to the consideration that “the Palæolithic age, referring as the phrase does to a stage of culture, and not to any chronological[14] period, is something which has come and gone at very different dates in different parts of the world;”[9] and that the same remark may be taken, in perhaps a smaller measure, to apply to the Neolithic age; still, when we remember what enormous lapses of time these ages may be roughly taken to represent, I think it is a most remarkable fact that, during the many thousands of years occupied by the former, the human mind should have practically made no advance upon its primitive methods of chipping flints; or that during the time occupied by the latter, this same mind should have been so slow in arriving, for example, at even so simple an invention as that of substituting horns for flints in the manufacture of weapons. In my next volume, where I shall have to deal especially with the evidence of intellectual evolution, I shall have to give many instances, all tending to show its extraordinarily slow progress during these æons of pre-historic time. Indeed, it was not until the great step had been made of substituting metals for both stones and horns, that mental evolution began to proceed at anything like a measurable rate. Yet this was, as it were, but a matter of yesterday. So that, upon the whole, if we have regard to the human species generally—whether over the surface of the earth at the present time, or in the records of geological history,—we can no longer maintain that a tendency to improvement in successive generations is here a leading characteristic. On the contrary, any improvement of so rapid and continuous a kind as that which is really contemplated, is characteristic only of a small division of the human race during the last few hours, as it were, of its existence.

On the other hand, as I have said, it is not true that animal species never display any traces of intellectual improvement from generation to generation. Were this the case, as already remarked, mental evolution could never have taken place in the brute creation, and so the phenomena of mind would have been wholly restricted to man: all animals would have required to present but a vegetative form of life. But,[15] apart from this general consideration, we meet with many particular instances of mental improvement in successive generations of animals, taking place even within the limited periods over which human observations can extend. In my previous work numerous cases will be found (especially in the chapters on the plasticity and blended origin of instincts), showing that it is quite a usual thing for birds and mammals to change even the most strongly inherited of their instinctive habits, in order to improve the conditions of their life in relation to some change which has taken place in their environments. And if it should be said that in such a case “the animal still does not rise above the level of birdhood or of beasthood,” the answer, of course, is, that neither does a Shakespeare or a Newton rise above the level of manhood.

On the whole, then, I cannot see that there is any valid distinction to be drawn between human and brute psychology with respect to improvement from generation to generation. Indeed, I should deem it almost more philosophical in any opponent of the theory of evolution, who happened to be acquainted with the facts bearing upon the subject, if he were to adopt the converse position, and argue that for the purposes of this theory there is not a sufficient distinction between human and brute psychology in this respect. For when we remember the great advance which, according to the theory of evolution, the mind of palæolithic man must already have made upon that of the higher apes, and when we remember that all races of existing men have the immense advantage of some form of language whereby to transmit to progeny the results of individual experience,—when we remember these things, the difficulty appears to me to lie on the side of explaining why, with such a start and with such advantages, the human species, both when it first appears upon the pages of geological history, and as it now appears in the great majority of its constituent races, should so far resemble animal species in the prolonged stagnation of its intellectual life.

I shall now pass on to consider the views of Mr. Wallace[16] and Mr. Mivart on the distinction between the mental endowments of man and of brute. Both these authors are skilled naturalists, and also professed evolutionists so far as the animal world is concerned: moreover, they further agree in maintaining that the principles of evolution cannot be held to apply to man. But it is curious that, so far as psychology is concerned, they base their arguments in support of their common conclusion on precisely opposite premisses. For while Mr. Mivart argues that human intelligence cannot be the same in kind as animal intelligence, because the mind of the lowest savage is incomparably superior to that of the highest ape; Mr. Wallace argues for the same conclusion on the ground that the intelligence of savages is so little removed from that of the higher apes, that the fact of their brains being proportionately larger must be held to point prospectively towards the needs of civilized life. “A brain,” he says, “slightly larger than that of the gorilla would, according to the evidence before us, fully have sufficed for the limited mental development of the savage; and we must therefore admit that the large brain he actually possesses could never have been developed solely by any of the laws of evolution.”[10]

Now, I have presented these two opinions side by side because I deem it an interesting, if not a suggestive circumstance, that the two leading dissenters in this country from the general school of evolutionists, although both holding the doctrine that man ought to be separated from the rest of the animal kingdom on psychological grounds, are nevertheless led to their common doctrine by directly opposite reasons.

The eminent French naturalist, Professor Quatrefages, also adopts the opinion that man should be separated from the rest of the animal kingdom as a being who, on psychological grounds, must be held to have had some different mode of origin. But he differs from both the English evolutionists in drawing his distinction somewhat more finely. For while Mivart and Wallace found their arguments upon the mind of man considered as a whole, Quatrefages expressly limits his ground to the faculties of conscience and religion. In other words, he allows—nay insists—that no valid distinction between man and brute can be drawn in respect of rationality or intellect. For instance, to take only one passage from his writings, he remarks:—“In the name of philosophy and psychology, I shall be accused of confounding certain intellectual attributes of the human reason with the exclusively sensitive faculties of animals. I shall presently endeavour to answer this criticism from the standpoint which should never be quitted by the naturalist, that, namely, of experiment and observation. I shall here confine myself to saying that, in my opinion, the animal is intelligent, and, although an (intellectually) rudimentary being, that its intelligence is nevertheless of the same nature as that of man.” Later on he says:—“Psychologists attribute religion and morality to[18] the reason, and make the latter an attribute of man (to the exclusion of animals). But with the reason they connect the highest phenomena of the intelligence. In my opinion, in so doing they confound, and refer to a common origin, facts entirely different. Thus, since they are unable to recognize either morality or religion in animals, which in reality do not possess these two faculties, they are forced to refuse them intelligence also, although the same animals, in my opinion, give decisive proof of their possession of this faculty every moment.”[11]

Touching these views I have only two things to observe. In the first place, they differ toto cælo from those both of Mr. Wallace and Mr. Mivart; and thus we now find that the three principal authorities who still stand out for a distinction of kind between man and brute on grounds of psychology, far from being in agreement, are really in fundamental opposition, seeing that they base their common conclusion on premisses which are all mutually exclusive of one another. In the next place, even if we were fully to agree with the opinion of the French anthropologist, or hold that a distinction of kind has to be drawn only at religion and morality, we should still be obliged to allow—although this is a point which he does not himself appear to have perceived—that the superiority of human intelligence is a necessary condition to both these attributes of the human mind. In other words, whether or not Quatrefages is right in his view that religion and morality betoken a difference of kind in the only animal species which presents them, at least it is certain that neither of these faculties could have occurred in that species, had it not also been gifted with a greatly superior order of intelligence. For even the most elementary forms of religion and morality depend upon ideas of a much more abstract, or intellectual, nature than are to be met with in any brute. Obviously, therefore, the first distinction that falls to be considered is the intellectual distinction. If analysis should show that the school represented by Quatrefages is right in regarding this[19] distinction as one of degree—and, therefore, that the school represented by Mivart is wrong in regarding it as one of kind,—the time will then have arrived to consider, in the same connection, these special faculties of morality and religion. Such, therefore, is the method that I intend to adopt. The whole of the present volume will be devoted to a consideration of “the origin of human faculty” in the larger sense of this term, or in accordance with the view that distinctively human faculty begins with distinctively human ideation. When this matter has been thoroughly discussed, the ground will have been prepared for considering in subsequent volumes the more special faculties of Morality and Religion.[12]

CHAPTER II.

IDEAS.[13]

I now pass on to consider the only distinction which in my opinion can be properly drawn between human and brute psychology. This is the great distinction which furnishes a full psychological explanation of all the many and immense differences that unquestionably do obtain between the mind of the highest ape and the mind of the lowest savage. It is, moreover, the distinction which is now universally recognized by psychologists of every school, from the Romanist to the agnostic in Religion, and from the idealist to the materialist in Philosophy.

The distinction has been clearly enunciated by many writers, from Aristotle downwards, but I may best render it in the words of Locke:—

“If it may be doubted, whether beasts compound and enlarge their ideas that way to any degree; this I think I may be positive in, that the power of abstracting is not at all in them; and that the having of general ideas is that which puts a perfect distinction betwixt man and brutes, and is an excellency which the faculties of brutes do by no means attain[21] to. For it is evident we observe no footsteps in them of making use of general signs for universal ideas; from which we have reason to imagine, that they have not the faculty of abstracting, or making general ideas, since they have no use of words, or any other general signs.

“Nor can it be imputed to their want of fit organs to frame articulate sounds that they have no use or knowledge of general words; since many of them, we find, can fashion such sounds, and pronounce words distinctly enough, but never with any such application; and, on the other side, men, who through some defect in the organs want words, yet fail not to express their universal ideas by signs, which serve them instead of general words; a faculty which we see beasts come short in. And therefore I think we may suppose, that it is in this that the species of brutes are discriminated from men; and it is that proper difference wherein they are wholly separated, and which at last widens to so vast a distance; for if they have any ideas at all, and are not bare machines (as some would have them), we cannot deny them to have some reason. It seems evident to me, that they do some of them in certain instances reason, as that they have sense; but it is only in particular ideas, just as they received them from their senses. They are the best of them tied up within those narrow bounds, and have not (as I think) the faculty to enlarge them by any kind of abstraction.”[14]

Here, then, we have stated, with all the common-sense lucidity of this great writer, what we may term the initial or basal distinction of which we are in search: it is that “proper difference” which, narrow at first as the space included between two lines of rails at their point of divergence, “at last widens to so vast a distance” as to end almost at the opposite poles of mind. For, by a continuous advance along the same line of development, the human mind is enabled to think about abstractions of its own making, which are more and more remote from the sensuous perception of concrete objects; it can unite these abstractions into an endless variety of ideal combinations; these, in turn, may become elaborated into ideal constructions of a more and more complex character; and so on until we arrive at the full powers of introspective thought with which we are each one of us directly cognisant.

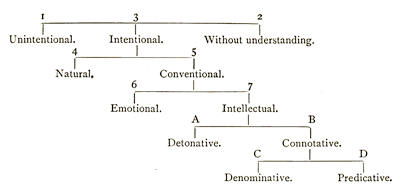

We now approach what is at once a matter of refined analysis, and a set of questions which are of fundamental importance to the whole superstructure of the present work. I mean the nature of abstraction, and the classification of ideas. No small amount of ambiguity still hangs about these important subjects, and in treating of them it is impossible to employ terms the meanings of which are agreed upon by all psychologists. But I will carefully define the meanings which I attach to these terms myself, and which I think are the meanings that they ought to bear. Moreover, I will end by adopting a classification which is to some extent novel, and by fully giving my reasons for so doing.

Psychologists are agreed that what they call particular[23] ideas, or ideas of particular objects, are of the nature of mental images, or memories of such objects—as when the sound of a friend’s voice brings before my mind the idea of that particular man. Psychologists are further agreed that what they term general ideas arise out of an assemblage of particular ideas, as when from my repeated observation of numerous individual men I form the idea of Man, or of an abstract being who comprises the resemblances between all these individual men, without regard to their individual differences. Hence, particular ideas answer to percepts, while general ideas answer to concepts: an individual preception (or its repetition) gives rise to its mnemonic equivalent as a particular idea; while a group of similar, though not altogether similar perceptions, gives rise to its mnemonic equivalent as a conception, which, therefore, is but another name for a general idea, thus generated by an assemblage of particular ideas. Just as Mr. Galton’s method of superimposing on the same sensitive plate a number of individual images gives rise to a blended photograph, wherein each of the individual constituents is partially and proportionally represented; so in the sensitive tablet of memory, numerous images of previous perceptions are fused together into a single conception, which then stands as a composite picture, or class-representation, of these its constituent images. Moreover, in the case of a sensitive plate it is only those particular images which present more or less numerous points of resemblance that admit of being thus blended into a distinct photograph; and so in the case of the mind, it is only those particular ideas which admit of being run together in a class that can go to constitute a clear concept.[15]

So much, then, for ideas as particular and general. Next, the term abstract has been used by different psychologists in different senses. For my own part, I will adhere to the usage of Locke in the passage above quoted, which is the usage adopted by the majority of modern writers upon these subjects. According to this usage, the term “abstract[24] idea” is practically synonymous with the term “general idea.” For the process of abstraction consists in mentally analysing the complex which is presented by any given object of perception, and ideally extracting those features or qualities upon which the attention is for the time being directed. Even the most individual of objects cannot fail to present an assemblage of qualities, and although it is true that such an object could not be divided into all its constituent qualities actually, it does admit of being so divided ideally. The individual man whom I know as John Smith could not be disintegrated into so much heat, flesh, bone, blood, colour, &c., without ceasing to be a man at all; but this does not hinder that I may ideally abstract his heat (by thinking of him as a corpse), his flesh, bones, and blood (by thinking of him as a dissected “subject”), his white colour of skin, his black colour of hair, and so forth. Now, it is evident that in the last resort our power of forming general ideas, or concepts, is dependent on this power of abstraction, or the power of ideally separating one or more of the qualities presented by percepts, i.e. by objects of particular ideas. My general idea of heat has only been rendered possible on account of my having ideally abstracted the quality of heat from sundry heated bodies, in most of which it has co-existed with numberless different associations of other qualities. But this does not hinder that, wherever I meet with that one quality, I recognize it as the same; and hence I arrive at a general or abstract idea of heat, apart from any other quality with which in particular cases it may happen to be associated.[16]

This faculty of ideal abstraction furnishes the conditio sine[25] quâ non to all grades in the development of thought; for by it alone can we compare idea with idea, and thus reach ever onwards to higher and higher levels, as well as to more and more complex structures of ideation. As to the history of this development we shall have more to say presently. Meanwhile I desire only to remark two things in connection with it. The first is that throughout this history the development is a development: the faculty of abstraction is everywhere the same in kind. And the next thing is that this development is everywhere dependent on the faculty of language. A great deal will require to be said on both these points in subsequent chapters; but it is needful to state the facts thus early—and they are facts which psychologists of all schools now accept,—in order to render intelligible the next step which I am about to make in my classification of ideas. This step is to distinguish between the faculty of abstraction where it is not dependent upon language, and where it is so dependent. I have just said that the faculty of abstraction is everywhere the same in kind; but, as I immediately proceeded to affirm that the development of abstraction is dependent upon language, I have thus far left the question open whether or not there can be any rudimentary abstraction without language. It is to this question, therefore, that we must next address ourselves.

On the one hand it may be argued that by restricting the term abstract to ideas which can only be formed by the aid of language, we are drawing an arbitrary line—fixing upon one degree in the continuous scale of a faculty which is throughout the same in kind. For, say some psychologists, it is evident that in our own case most of our more simple abstract or general ideas are not dependent for their existence upon words. Or, if this be disputed, these psychologists are able to point to infants, and even to the lower animals, in proof of their assertion. For an infant undoubtedly exhibits the possession of simple general ideas prior to the possession of any articulate language; and after it begins to use such language it does so by spontaneously widening the generality of signification attaching to its original words. In proof of both these statements numberless observations might be quoted, and further on will be quoted; but here I need only wait to give one in proof of each. As regards the first, Professor Preyer tells us that at eight months old,[17] and therefore long before it was able to speak, his child was able to classify all glass bottles as resembling—or belonging to the order of—a feeding-bottle.[18] As regards the second, M. Taine tells us of a little girl eighteen months old, who was amused by her mother hiding in play behind a piece of furniture, and saying “Coucou.” Again, when her food was too hot, when she went too near the fire or candle, and when the sun was warm, she was told “Ça brûle.” One day, on seeing the sun disappear behind a hill, she exclaimed, “‘A b’ûle coucou,” thereby showing both the formation and combination of general ideas, “not only expressed by words which we do not employ (and, therefore, not by any other words that she can have previously employed), but also corresponding to ideas, consequently to classes[27] of objects and general characters which in our cases have disappeared. The hot soup, the fire on the hearth, the flame of the candle, the noonday heat in the garden, and last of all, the sun, make up one of these classes. The figure of the nurse or mother disappearing behind a hill, form the other class.”[19]

Coming next to the case of brutes, and to begin with the simplest kind of illustrations, all the higher animals have general ideas of “Good-for-eating,” and “Not-good-for-eating,” quite apart from any particular objects of which either of these qualities happens to be characteristic. For, if we give any of the higher animals a morsel of food of a kind which it has never before met with, the animal does not immediately snap it up, nor does it immediately reject our offer; but it subjects the morsel to a careful examination before consigning it to the mouth. This proves, if anything can, that such an animal has a general or abstract idea of sweet, bitter, hot, or, in general, Good-for-eating and Not-good-for-eating—the motives of the examination clearly being to ascertain which of these two general ideas of kind is appropriate to the particular object examined. When we ourselves select something which we suppose will prove good to eat, we do not require to call to our aid any of that higher class of abstract ideas for which we are indebted to our powers of language: it is enough to determine our decision if the particular appearance, smell, or taste of the food makes us feel that it probably conforms to our general idea of Good-for-eating. And, therefore, when we see animals determining between similar alternatives by precisely similar methods, we cannot reasonably doubt that the psychological processes are similar; for, as we know that these processes in ourselves do not involve any of the higher powers of our minds, there is no reason to doubt that the processes, which in their manifestations appear so similar, really are what they appear to be—the same. Again, if I see a fox prowling about a farm-yard, I infer that he has been led by hunger to go where he has a general idea that there are a good many eatable things to be fallen in with—just[28] as I myself am led by a similar impulse to visit a restaurant. Similarly, if I say to my dog the word “Cat,” I arouse in his mind an idea, not of any cat in particular—for he sees so many cats,—but of a Cat in general. Or when this same dog accidentally crosses the track of a strange dog, the scent of this strange dog makes him stiffen his tail and erect the hair on his back in preparation for a fight; yet the scent of an unknown dog must arouse in his mind, not the idea of any dog in particular, but an idea of the animal Dog in general.

Thus far, it will be remembered, I have been presenting evidence in favour of the view that both infants and animals show themselves capable of forming general ideas of a simple order, and, therefore, that to the formation of such ideas the use of language is not essential. I will next consider what has to be said on the other side of the question; for, as previously remarked, many—I may say most—psychologists repudiate this kind of evidence in toto, as not germain to the subject of debate. First, therefore, I will consider their objections to this kind of evidence; next I will sum up the whole question; and, lastly, I will suggest a classification of ideas which in my opinion ought to be accepted by both sides as constituting a common ground of reconciliation.

To begin with another quotation from Locke, “How far brutes partake in this faculty [i.e. that of comparing ideas] is not easy to determine; I imagine they have it not in any great degree: for though they probably have several ideas distinct enough, yet it seems to me to be the prerogative of human understanding, when it has sufficiently distinguished any ideas, so as to perceive them to be perfectly different, and so consequently two, to cast about and consider in what circumstances they are capable to be compared: and therefore I think beasts compare not their ideas further than some sensible circumstances annexed to the objects themselves. The other power of comparing, which may be observed in men, belonging to general ideas, and useful only to abstract reasonings, we may probably conjecture beasts have not.

“The next operation we may observe in the mind about[29] its ideas, is composition; whereby it puts together several of those simple ones it has received from sensation and reflection, and combines them into complex ones. Under this head of composition may be reckoned also that of enlarging; wherein, though the composition does not so much appear as in more complex ones, yet it is nevertheless a putting several ideas together, though of the same kind. Thus, by adding several units together, we make the idea of a dozen; and by putting together the repeated ideas of several perches, we frame that of a furlong.

“In this, also, I suppose, brutes come far short of men; for though they take in, and retain together several combinations of simple ideas, as possibly the shape, smell, and voice of his master make up the complex idea a dog has of him, or rather are so many distinct marks whereby he knows him; yet I do not think they do of themselves ever compound them, and make complex ideas. And perhaps even where we think they have complex ideas, it is only one simple one that directs them in the knowledge of several things, which possibly they distinguish less by sight than we imagine; for I have been credibly informed that a bitch will nurse, play with, and be fond of young foxes, as much as, and in place of, her puppies; if you can but get them once to suck her so long, that her milk may go through them. And those animals, which have a numerous brood of young ones at once, appear not to have any knowledge of their number: for though they are mightily concerned for any of their young that are taken from them whilst they are in sight or hearing; yet if one or two be stolen from them in their absence, or without noise, they appear not to miss them, or have any sense that their number is lessened.”[20]

Now, from the whole of this passage, it is apparent that the “comparing,” “compounding,” and “enlarging” of ideas which Locke has in view, is the conscious or intentional comparing, compounding, and enlarging that belongs only to the province of reflection, or thought. He in no way concerns[30] himself with such powers of “comparing and compounding of ideas” as he allows that animals present, unless it can be shown that animals are able to “cast about and consider in what circumstances they are capable to be compared.” And then he adds, “Therefore, I think, beasts compare not their ideas further than some sensible circumstances annexed to the objects themselves. The other power of comparing, which may be observed in men, belonging to general ideas, and useful only to abstract reasonings, we may probably conjecture beasts have not.” So far, then, it seems perfectly obvious that Locke believed animals to present the power of “comparing and compounding” “simple ideas,” up to the point where such comparison and composition begins to be assisted by the power of reflective thought. Therefore, when he immediately afterwards proceeds to explain abstraction thus: “The same colour being observed to-day in chalk or snow, which the mind yesterday received from milk, it considers that appearance alone, makes it a representative of all of that kind; and having given it the name whiteness, it by that sound signifies the same quality, wheresoever it be imagined or met with; and thus universals, whether ideas or terms, are made”—when he thus proceeds to explain abstraction, we can have no doubt that what he means by abstraction is the power of ideally contemplating qualities as separated from objects, or, as he expresses it, “considering appearances alone.” Therefore I conclude, without further discussion, that in the terminology of Locke the word abstraction is applied only to those higher developments of the faculty which are rendered possible by reflection.

Now, on what does this power of reflection depend? As we shall see more fully later on, it depends on Language, or on the power of affixing names to abstract and general ideas. So far as I am aware, psychologists of all existing schools are in agreement upon this point, or in holding that the power of affixing names to abstractions is at once the condition to reflective thought, and the explanation of the difference between man and brute in respect of ideation.

It seems needless to dwell upon a matter where all are agreed, and concerning which a great deal more will require to be said in subsequent chapters. At present I am only endeavouring to ascertain the ground of difference between those psychologists who attribute, and those who deny to animals the faculty of abstraction. And I think I am now in a position to render this point perfectly clear. As we have already seen, and we shall frequently see again, it is allowed on all hands that animals in their ideation are not shut up to the special imaging (or remembering) of particular perceptions; but that they do present the power, as Locke phrases it, of “taking in and retaining together several combinations of simple ideas.”[21] The only question, then, really is whether or not this power is the power of abstraction. In the opinion of some psychologists it is: in the opinion of other psychologists it is not. Now, on what does an answer to this question depend? Clearly it depends on whether we hold it essential to an abstract or general idea that it should be incarnate as a word. Under one point of view, to “take in and retain together several combinations of simple ideas,” is to form a general concept of so many percepts. But, under another point of view, such a combination of simple ideas is only then entitled to be regarded as a concept, when it has been conceived by the mind as a concept, or when, in virtue of having been bodied forth in a name, it stands before the mind as a distinct and organic offspring of mind—so becoming an object as well as a product of ideation. For then only can the abstract idea be known as abstract, and then only can it be available as a definite creation of thought, capable of being built into any further and more elaborate structure of ideation. Or, to quote M. Taine, who advocates this view with great lucidity, “Of our numerous experiences [i.e. individual perceptions of a show of araucarias] there remain on the following[32] day four or five more or less distinct recollections, which obliterated themselves, leave behind in us a simple, colourless, vague representation, into which enter as components various reviving sensations, in an utterly feeble, incomplete, and abortive state. But this representation is not the general or abstract idea. It is but its accompaniment, and, if I may say so, the one from which it is extracted. For the representation, though badly sketched, is a sketch, the sensible sketch of a distinct individual; in fact, if I make it persist and dwell upon it, it repeats some special visual sensation; I see mentally some outline which corresponds only to some particular araucaria, and, therefore, cannot correspond to the whole class: now, my abstract idea corresponds to the whole class; it differs, then, from the representation of an individual. Moreover, my abstract idea is perfectly clear and determinate; now that I possess it, I never fail to recognize an araucaria among the various plants I may be shown; it differs, then, from the confused and floating representation I have of some particular araucaria. What is there, then, within me so clear and determinate, corresponding to the abstract character, corresponding to all araucarias, and corresponding to it alone? A class-name, the name araucaria.... Thus we conceive the abstract characters of things by means of abstract names which are our abstract ideas, and the formation of our abstract ideas is nothing more than the formation of names.”[22]

The real issue, then, is as to what we are to understand by this term abstraction, or its equivalents. If we are to limit the term to the faculty of “taking in and retaining together several combinations of simple ideas,” plus the faculty of giving a name to the resulting compound, then[33] undoubtedly animals differ from men in not presenting the faculty of abstraction; for this is no more than to say that animals have not the faculty of speech. But if the term in question be not thus limited—if it be taken to mean the first of the above-named processes irrespective of the second,—then, no less undoubtedly, animals resemble men in presenting the faculty of abstraction. In accordance with the former definition, it necessarily follows that “we conceive the abstract characters of things by means of abstract names which ARE our abstract ideas;” and, therefore, that “the formation of our abstract ideas is nothing more than the formation of names.” But, in accordance with the latter view, great as may be the importance of affixing a name to a compound of simple ideas for the purpose of giving that compound greater clearness and stability, the essence of abstraction consists in the act of compounding, or in the blending together of particular ideas into a general idea of the class to which the individual things belong. The act of bestowing upon this compound idea a class-name is quite a distinct act, and one which is necessarily subsequent to the previous act of compounding: why then, it may be asked, should we deny that such a compound idea is a general or abstract idea, only because it is not followed up by the artifice of giving it a name?

In my opinion so much has to be said in favour of both of these views that I am not going to pronounce against either. What I have hitherto been endeavouring to do is to reveal clearly that the question whether or not there is any difference between the brute and the man in respect of abstraction, is nothing more than a question of terminology. The real question will arise only when we come to treat of the faculty of language: the question before us now is merely a question of psychological classification, or of the nomenclature of ideas. Now, it appears to me that this question admits of being definitely settled, and a great deal of needless misunderstanding removed, by a slight re-adjustment and a closer definition of terms. For it must be on all hands admitted[34] that, whether or not we choose to denominate by the word abstraction the faculty of compounding simple ideas without the faculty of naming the compounds, at the place where this additional faculty of naming supervenes, so immense an accession to the previous faculty is furnished, that any system of psychological nomenclature must be highly imperfect if it be destitute of terms whereby to recognize the difference. For even if it were conceded by psychologists of the opposite school that the essence of abstraction consists in the compounding of simple ideas, and not at all in the subsequent process of naming the compounds; still the effect of this subsequent process—or additional faculty—is so prodigious, that the higher degrees of abstraction which by it are rendered possible, certainly require to be marked off, or to be distinguished from, the lower degrees. Without, therefore, in any way prejudicing the question as to whether we have here a difference of degree or a difference of kind, I will submit a classification of ideas which, while not open to objection from either side of this question, will greatly help us in our subsequent treatment of the question itself.

The word “Idea” I will use in the sense defined in my previous work—namely, as a generic term to signify indifferently any product of imagination, from the mere memory of a sensuous impression up to the result of the most abstruse generalization.[23]

By “Simple Idea,” “Particular Idea,” or “Concrete Idea,” I understand the mere memory of a particular sensuous perception.

By “Compound Idea,” “Complex Idea,” or “Mixed Idea,” I understand the combination of simple, particular, or concrete ideas into that kind of composite idea which is possible without the aid of language.

Lastly, by “General Idea,” “Abstract Idea,” “Concept,” or “Notion,” I understand that kind of composite idea which is rendered possible only by the aid of language, or by the process of naming abstractions as abstractions.

Now in this classification, notwithstanding that it is needful to quote at least ten distinct terms which are either now in use among psychologists or have been used by classical English writers upon these topics, we may observe that there are really but three separate classes to be distinguished. Moreover, it will be noticed that, for the sake of definition, I restrict the first three terms to denote memories of particular sensuous perceptions—refusing, therefore, to apply them to those blended memories of many sensuous perceptions which enable animals and infants (as well as ourselves) to form compound ideas of kind or class without the aid of language. Again, the first division of this threefold classification has to do only with what are termed percepts, while the last has to do only with what are termed concepts. Now there does not exist any equivalent word to meet the middle division. And this fact in itself shows most forcibly the state of ambiguous confusion into which the classification of ideas has been wrought. Psychologists of both the schools that we are considering—namely, those who maintain and those who deny that there is any difference of kind between the ideation of men and animals—are equally forced to allow that there is a great difference between what I have called a simple idea and what I have called a compound idea. In other words, it is a matter of obvious fact that the only distinction between ideas is not that between the memory of a particular percept and the formation of a named concept; for between these two classes of ideas there obviously lies another class, in virtue of which even animals and infants are able to distinguish individual objects as belonging to a sort or kind. Yet this large and important territory of ideation, lying between the other two, is, so to speak, unnamed ground. Even the words “compound idea,” “complex idea,” and “mixed idea,” are by me restricted to it without the sanction of previous usage; for, as above remarked, so completely has the existence of this intermediate land been ignored, that we have no word at all which is applicable to it in the same way that Percept[36] and Concept are applicable to the lands on either side of it. The consequence is that psychologists of the one school invade this intermediate province of ideation with terms that are applicable only to the lower province, while psychologists of the other school invade it with terms which are applicable only to the higher: the one matter upon which they all appear to agree being that of ignoring the wide area which this intermediate territory covers—and, consequently, also ignoring the great distance by which the territories on either side of it are separated.

In addition, then, to the terms Percept and Concept, I coin the word Recept. This is a term which seems exactly to meet the requirements of the case. For as perception literally means a taking wholly, and conception a taking together, reception means a taking again. Consequently, a recept is that which is taken again, or a recognition of things previously cognized. Now, it belongs to the essence of what I have defined as compound ideas (recepts), that they arise in the mind out of a repetition of more or less similar percepts. Having seen a number of araucarias, the mind receives from the whole mass of individuals which it perceives a composite idea of Araucaria, or of a class comprising all individuals of that kind—an idea which differs from a general or abstract idea only in not being consciously fixed and signed as an idea by means of an abstract name. Compound ideas, therefore, can only arise out of a repetition of more or less similar percepts; and hence the appropriateness of designating them recepts. Moreover, the associations which we have with the cognate words, Receive, Reception, &c., are all of the passive kind, as the associations which we have with the words Conceive, Conception, &c., are of the active kind. Now, here again, the use of the word recept is seen to be appropriate to the class of ideas in question, because in receiving such ideas the mind is passive, as in conceiving abstract ideas the mind is active. In order to form a concept, the mind must intentionally bring together its percepts (or the memories of them), for the purpose of[37] binding them up as a bundle of similars, and labelling the bundle with a name. But in order to form a recept, the mind need perform no such intentional actions: the similarities among the percepts with which alone this order of ideation is concerned, are so marked, so conspicuous, and so frequently repeated in observation, that in the very moment of perception they sort themselves, and, as it were, fall into their appropriate classes spontaneously, or without any conscious effort on the part of the percipient. We do not require to name stones to distinguish them from loaves, nor fish to distinguish them from scorpions. Class distinctions of this kind are conveyed in the very act of perception—e.g. the case of the infant with the glass bottles,—and, as we shall subsequently see, in the case of the higher animals admit of being carried to a wonderful pitch of discriminative perfection. Recepts, then, are spontaneous associations, formed unintentionally as what may be termed unperceived abstractions.[24]

One further remark remains to be added before our nomenclature of ideas can be regarded as complete. It will have been noticed that the term “general idea” is equally appropriate to ideas of class or kind, whether or not such ideas are named. The ideas Good-for-eating and Not-good-for-eating are as general to an animal as they are to a man, and have in each case been formed in the same way—namely, by an accumulation of particular experiences spontaneously assorted in consciousness. General ideas of this kind, however, have not been contemplated by previous writers while dealing with the psychology of generalization: hence the term “general,” like the term “abstract,” has by usage become restricted to those higher products of ideation which depend on the faculty of language. And the only words that I can find to have been used by any previous writers to designate the ideas concerned in that lower kind of generalization which does not depend on language, are the words above given—namely, Complex, Compound, and Mixed. Now, none of these words are so good as the word General, because none of them express the notion of genus or class; and the great distinction between the idea which an animal or an infant has, say of an individual man and of men in general, is not that the one idea is simple, and the other complex, compound, or mixed; but that the one idea is particular and the other general. Therefore consistency would dictate that the term “general” should be applied to all ideas of class or kind, as distinguished from ideas of particulars or individuals—irrespective of the degree of generality, and irrespective, therefore, of the accident whether or not, quâ general, such ideas are dependent on language. Nevertheless, as the term has been through previous usage restricted to ideas of the higher order of generality, I will not introduce confusion by extending its use to the lower order, or by speaking of an animal as capable of generalizing. A parallel term, however, is needed; and, therefore, I will speak of the general or class ideas which are formed without the aid of language as generic. This word has the double advantage of[39] retaining a verbal as well as a substantial analogy with the allied term general. It also serves to indicate that generic ideas, or recepts, are not only ideas of class or kind, but have been generated from the intermixture of individual ideas—i.e. from the blended memories of particular percepts.

My nomenclature of ideas, therefore, may be presented in a tabular form thus:—

| IDEAS | General, Abstract, or Notional = Concepts. Complex, Compound, or Mixed = Recepts, or Generic Ideas. Simple, Particular, or Concrete = Memories of Percepts. [25] |

CHAPTER III.

LOGIC OF RECEPTS.