Jean de la Fontaine

CONTENTS

As Essay on the Life and Works of Jean de la Fontaine xiii

The Life of Æsop, the Phrygian xxxiii

Dedication to Monseigneur the Dauphin li

Preface lv

To Monseigneur the Dauphin lxiii

The Grasshopper and the Ant 3

The Raven and the Fox 5

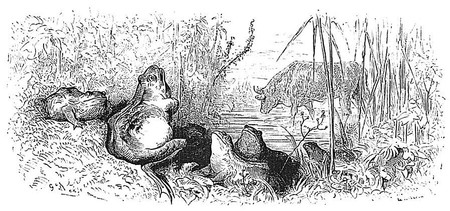

The Frog that Wished to make Herself as Big as the Ox 7

The Two Mules 11

The Wolf and the Dog 13

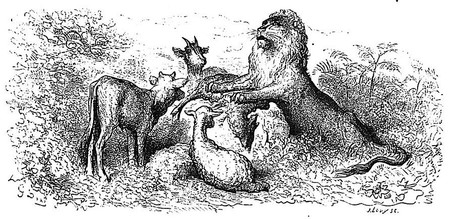

The Heifer, the She-goat, and the Lamb, in Partnership

with the Lion 16

The Wallet 18

The Swallow and the Little Birds 20

The Town Rat and the Country Rat 27

The Man and his Image 29

The Dragon with many Heads, and the Dragon with

many Tails 31

The Wolf and the Lamb 35

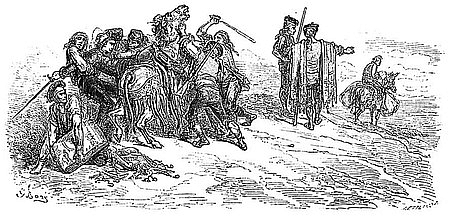

The Robbers and the Ass 37

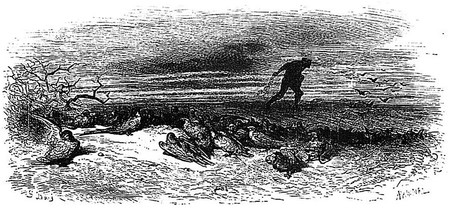

Death and the Woodcutter 39

Simonides rescued by the Gods 43

Death and the Unhappy Man 47

The Wolf turned Shepherd 51

The Child and the Schoolmaster 53

The Pullet and the Pearl 55

The Drones and the Bees 56

The Oak and the Reed 61

Against Those Who are Hard to Please 63

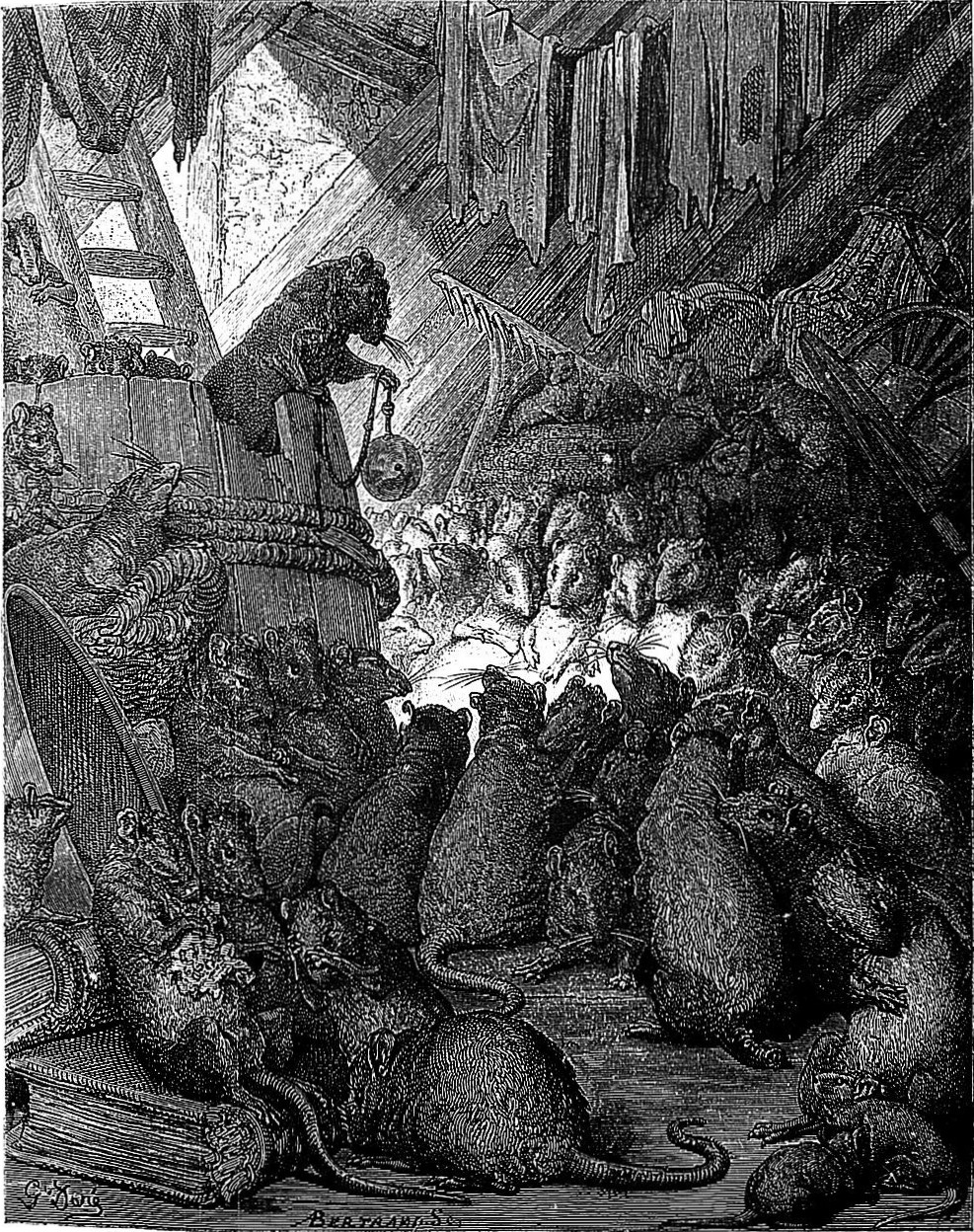

The Council held by the Rats 69

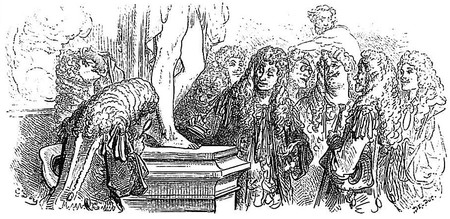

The Wolf Pleading against the Fox before the Ape 71

The Middle-Aged Man and the Two Widows 73

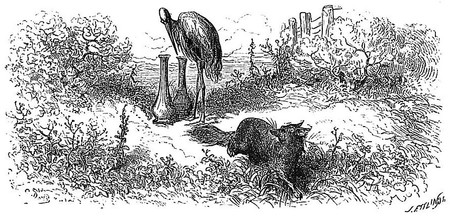

The Fox and the Stork 75

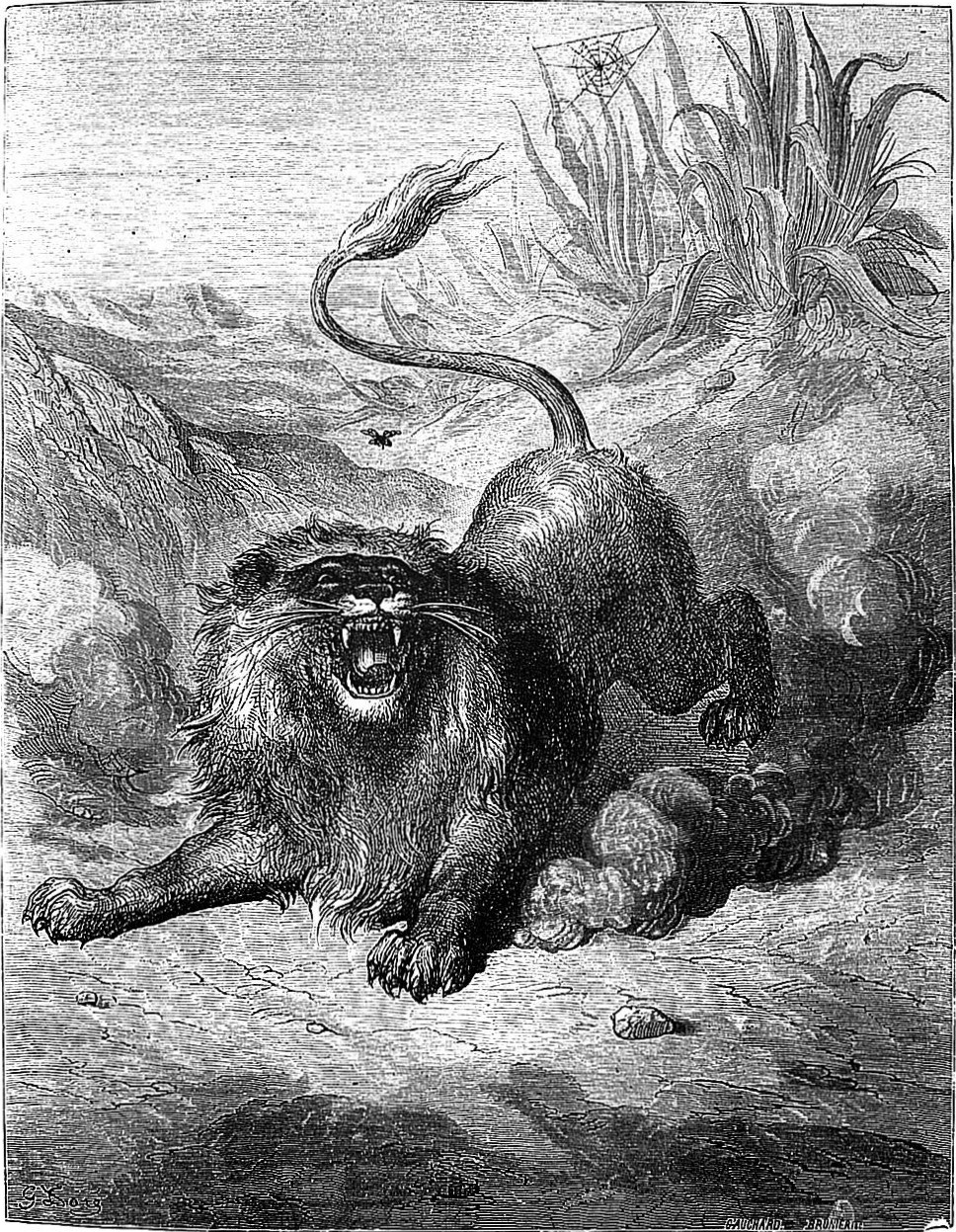

The Lion and the Gnat 79

The Ass Laden with Sponges, and the Ass Laden

with Salt 82

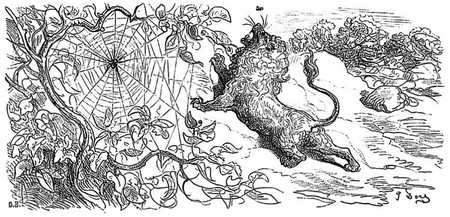

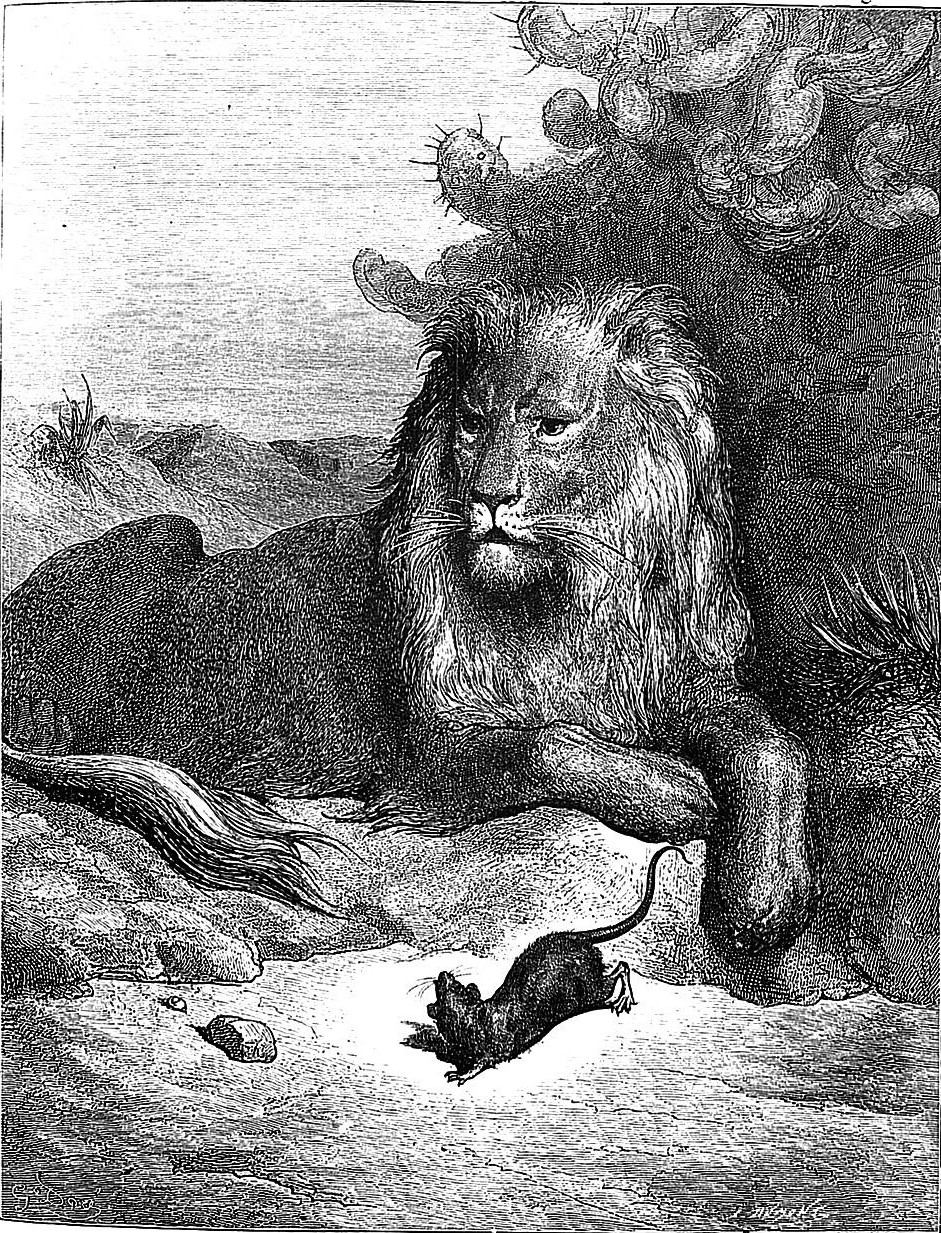

The Lion and the Rat 84

The Dove and the Ant 88

The Astrologer Who let Himself Fall into the Well 90

The Hare and the Frogs 95

The Two Bulls and the Frog 97

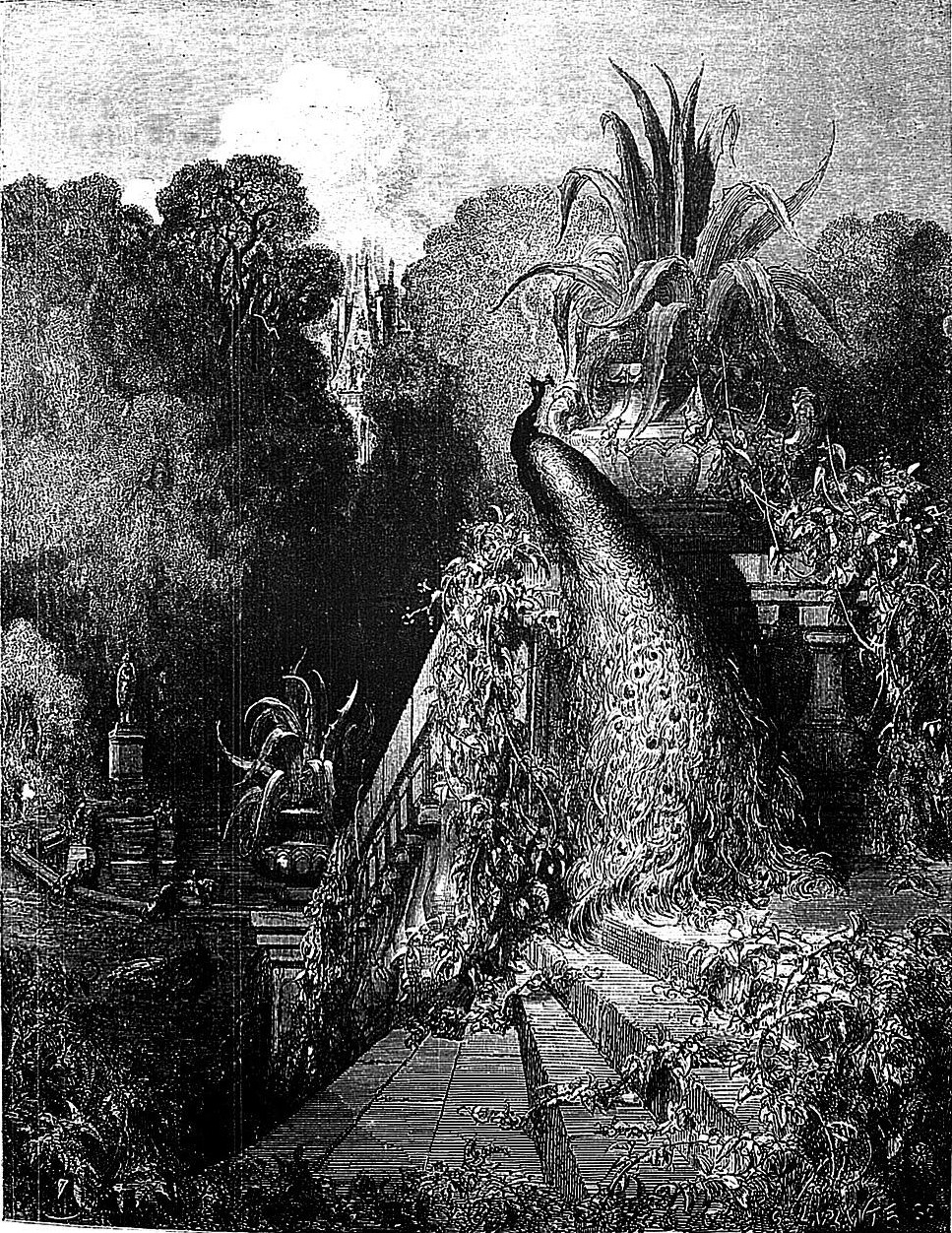

The Peacock Complaining to Juno 101

The Bat and the Two Weasels 103

The Bird Wounded by an Arrow 105

The Miller, his Son, and the Ass 106

The Cock and the Fox 113

The Frogs Who Asked for a King 116

The Dog and Her Companion 121

The Fox and the Grapes 125

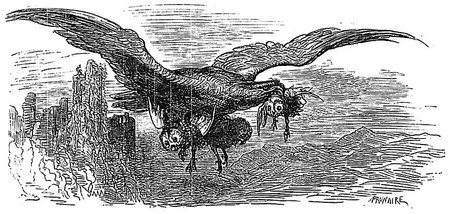

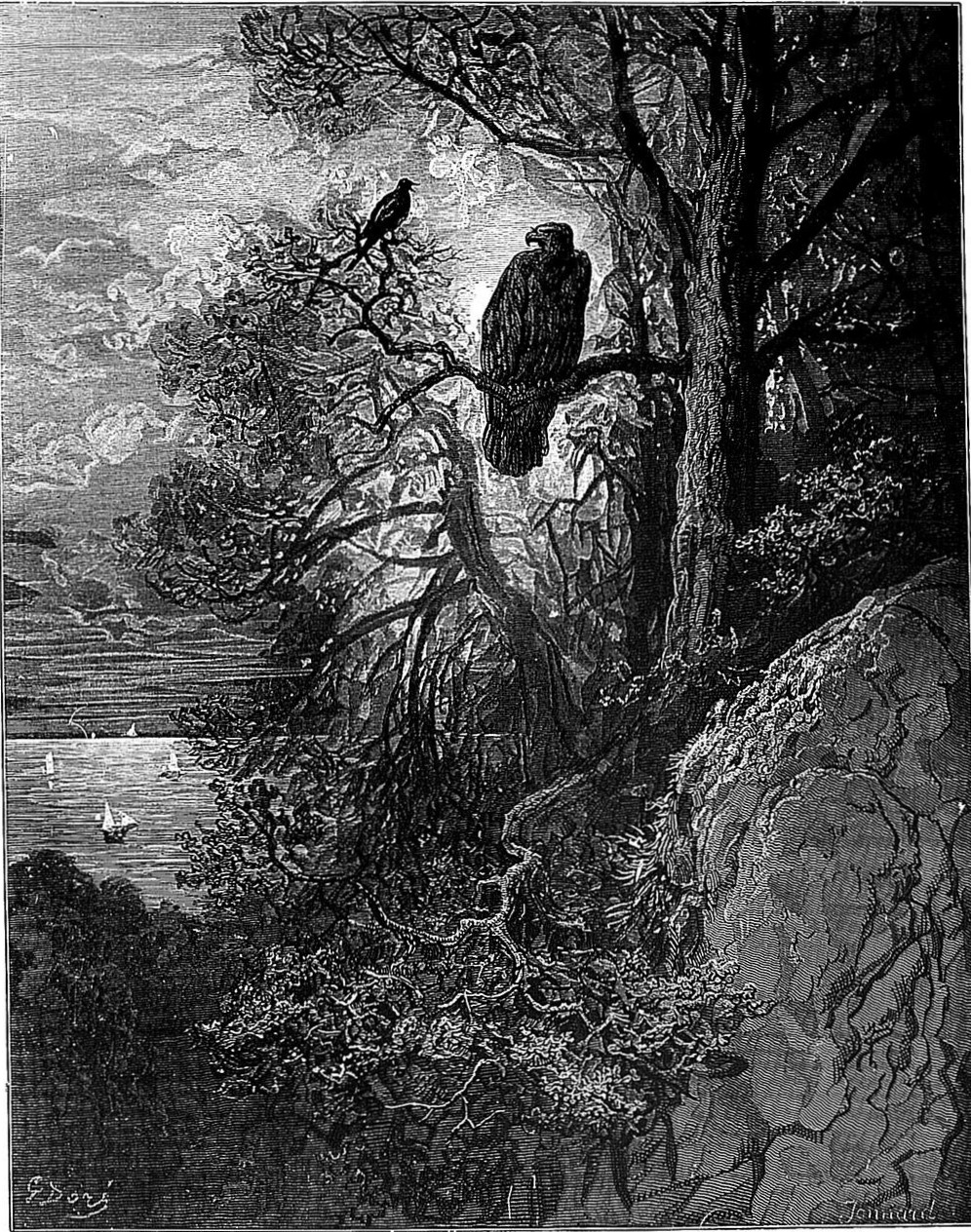

The Eagle and the Beetle 126

The Raven Who Wished to Imitate the Eagle 130

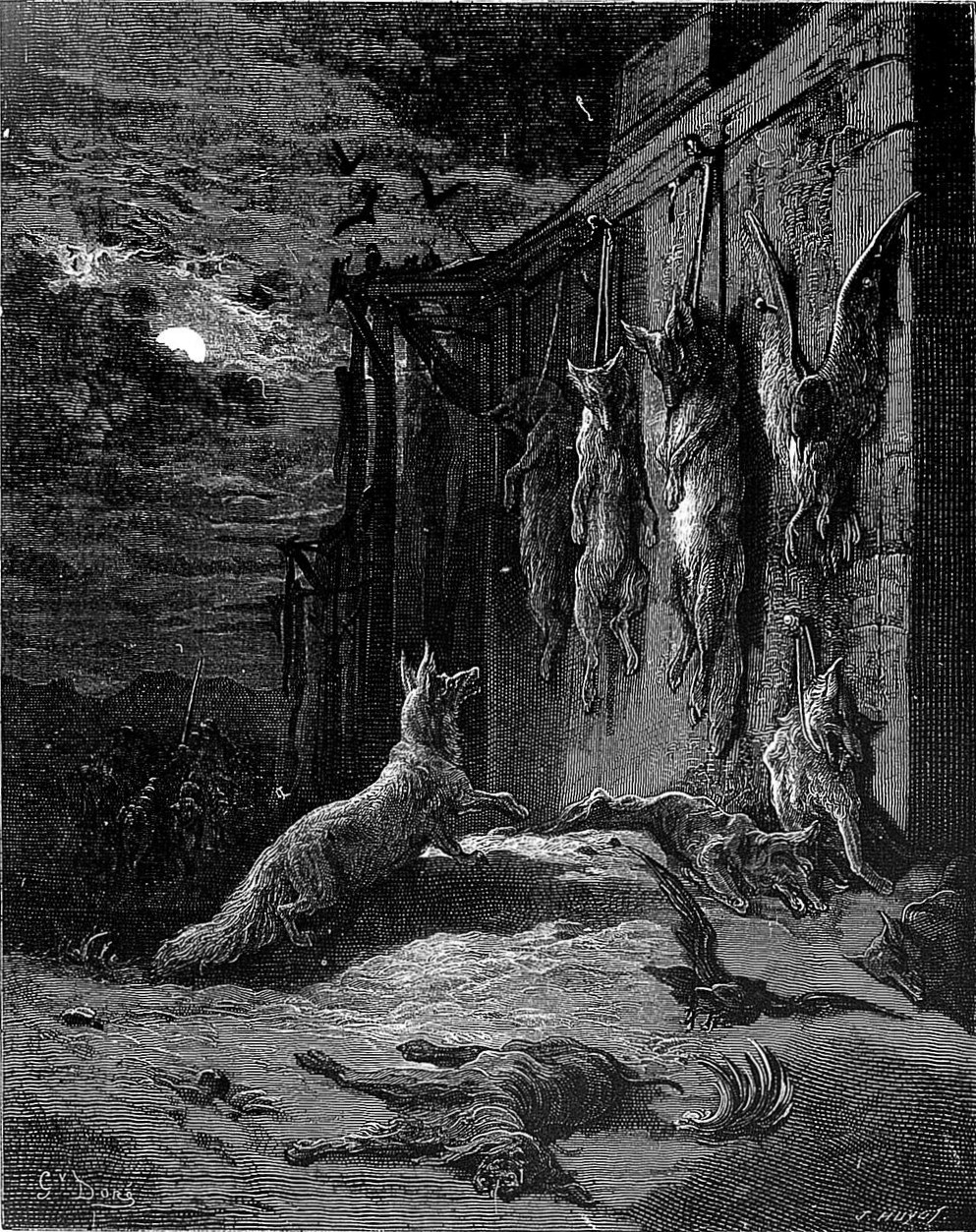

The Wolves and the Sheep 132

The Cat Changed into a Woman 136

[Pg vi]Philomel and Progne 141

The Lion and the Ass 143

The Cat and the Old Rat 145

A Will Interpreted by Æsop 151

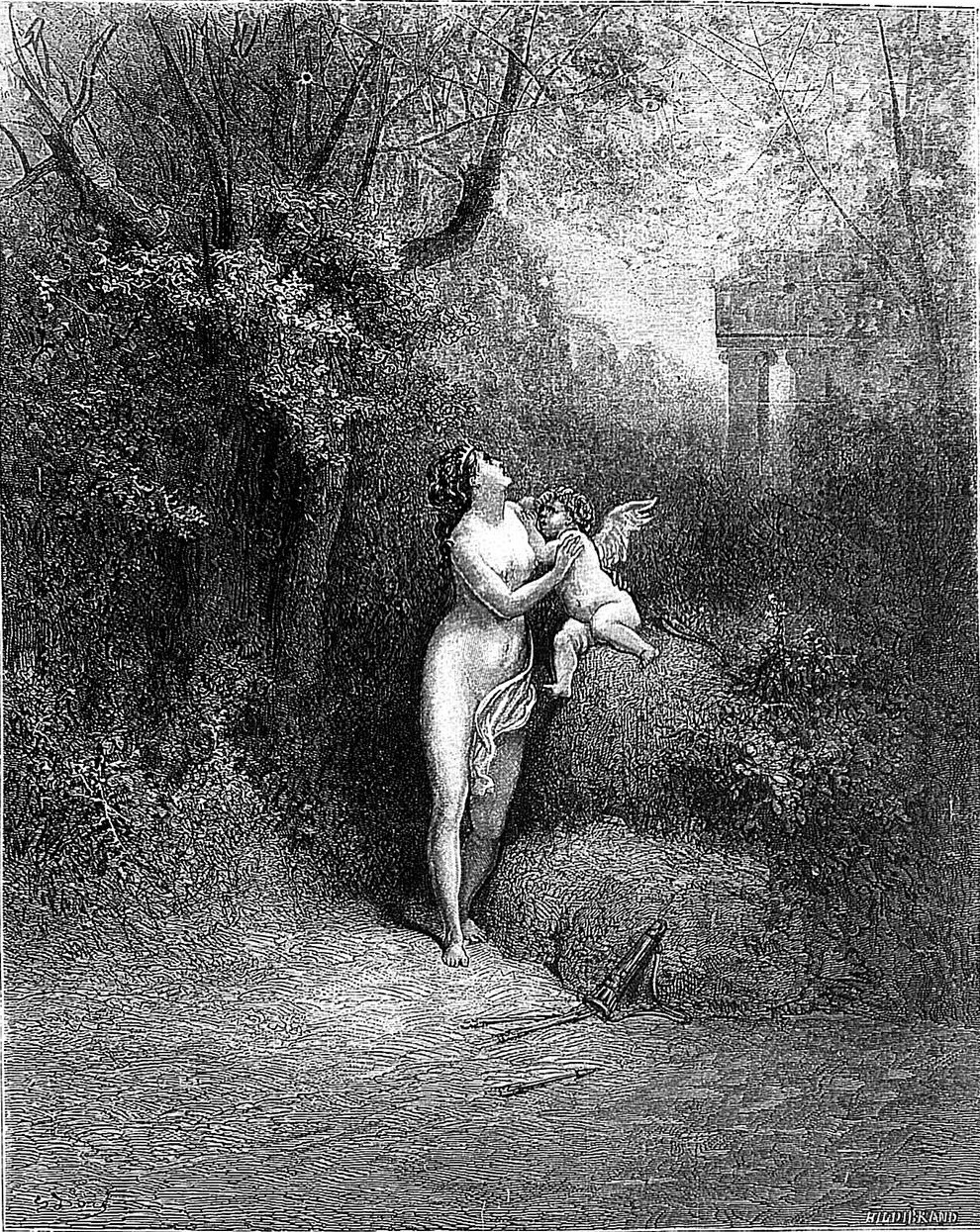

The Lion in Love 156

The Fox and the Goat 161

The Shepherd and the Sea 165

The Drunkard and His Wife 167

King Caster and the Members 169

The Monkey and the Dolphin 172

The Eagle, the Wild Sow, and the Cat 177

The Miser Who Lost His Treasure 180

The Gout and the Spider 185

The Eye of the Master 188

The Wolf and the Stork 193

The Lion Defeated by Man 195

The Swan and the Cook 196

The Wolf, the Goat, and the Kid 198

The Wolf, the Mother, and the Child 200

The Lion Grown Old 205

The Drowned Woman 207

The Weasel in the Granary 209

The Lark and Her Little Ones With the Owner

of a Field 211

The Fly and the Ant 217

The Gardener and his Master 220

The Woodman and Mercury 223

The Ass and the Little Dog 230

Man and the Wooden Idol 233

The Jay Dressed in Peacock's Plumes 235

The Little Fish and the Fisherman 239

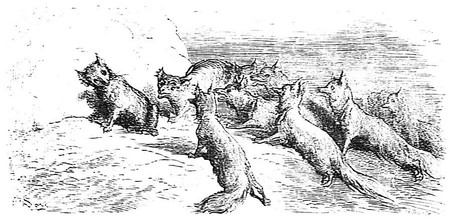

Battle Between the Rats and Weasles 241

The Camel and the Drift-Wood 244

The Frog and the Rat 246

The Old Woman and Her Servants 251

The Animals Sending a Tribute to Alexander 253

The Horse Wishing to be Revenged on the Stag 257

The Fox and the Bust 259

The Horse and the Wolf 263

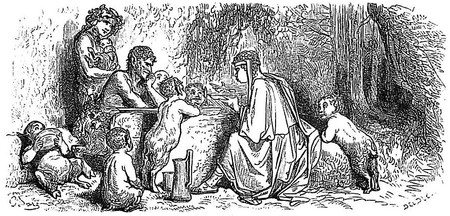

The Saying of Socrates 265

The Old Man and His Children 267

The Oracle and the Impious Man 270

The Mountain in Labour 272

Fortune and the Little Child 275

The Earthen Pot and the Iron Pot 277

The Hare's Ears 279

The Fox with His Tail Cut Off 281

The Satyr and the Passer-By 283

The Doctors 287

The Labouring Man and His Children 289

The Hen with the Golden Eggs 291

The Ass that Carried the Relics 295

The Serpent and the File 296

The Hare and the Partridge 298

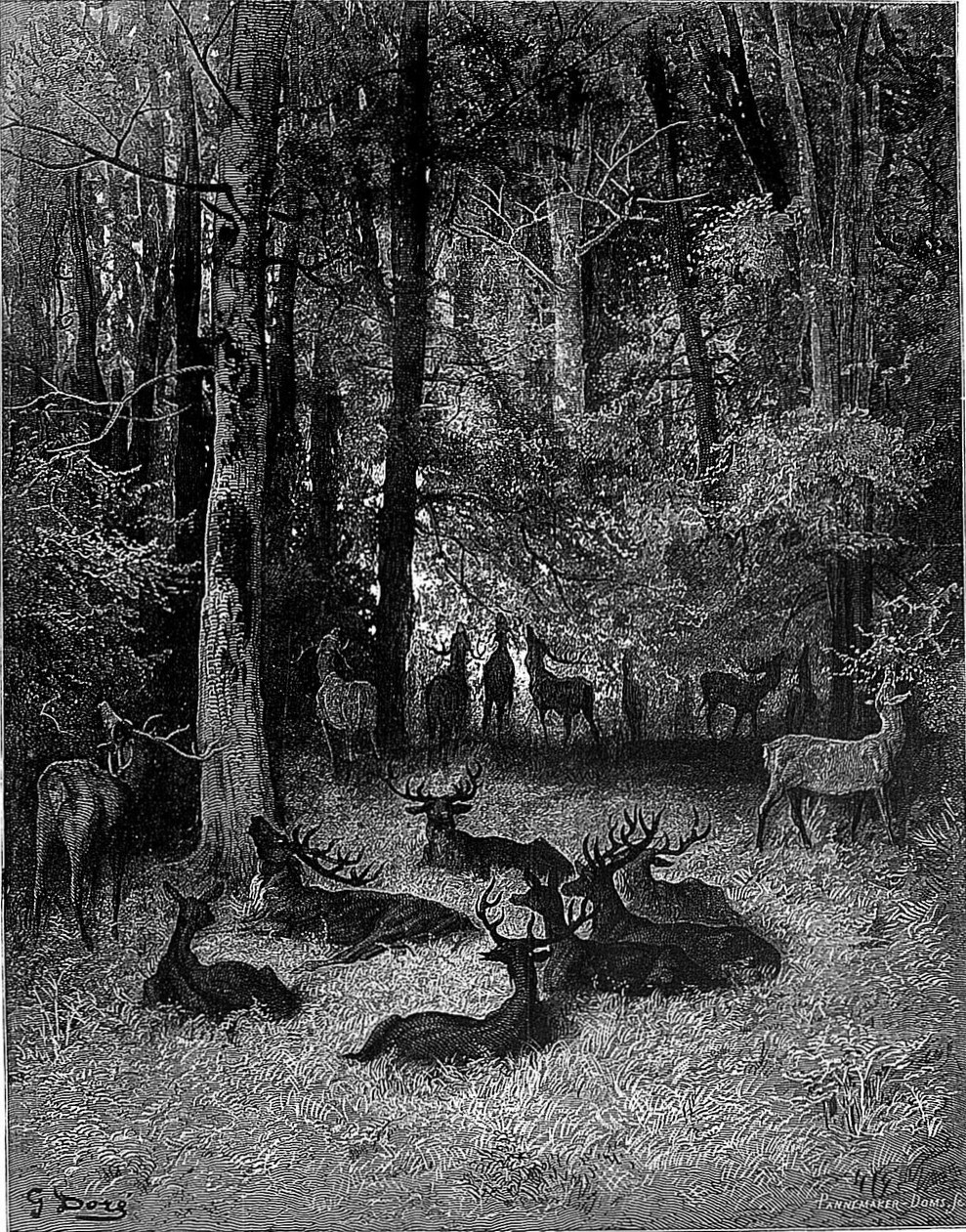

The Stag and the Vine 300

The Lion Going to War 304

The Ass in the Lion's Skin 306

The Eagle and the Owl 308

The Shepherd and the Lion 313

The Lion and the Hunter 316

Phœbus and Boreas 318

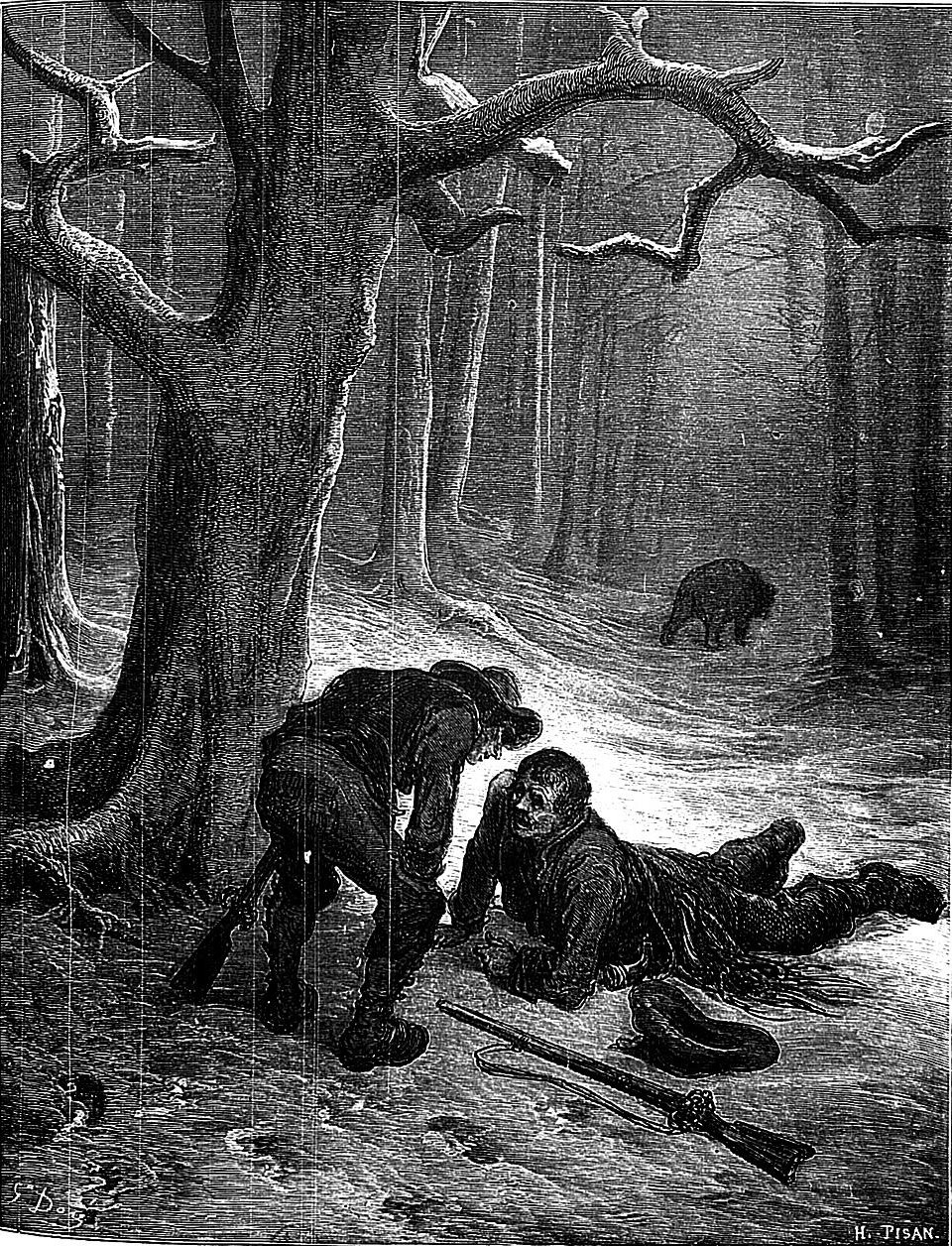

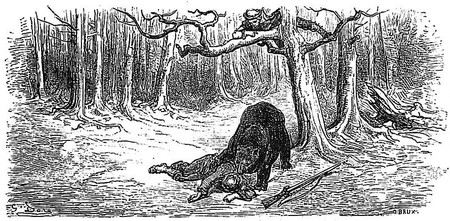

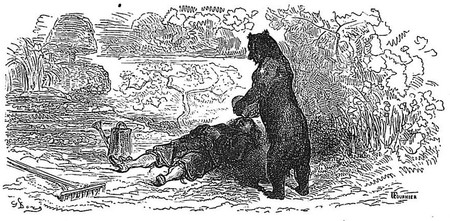

The Bear and the Two Friends 323

Jupiter and the Farmer 326

The Stag Viewing Himself in the Stream 328

The Cockerel, the Cat, and the Little Rat 332

The Fox, the Monkey, and the Other Animals 335

The Mule That Boasted of His Family 337

The Old Man and the Ass 339

The Countryman and the Serpent 343

The Hare and the Tortoise 345

The Sick Lion and the Fox 348

The Ass and His Masters 352

The Sun and the Frogs 354

The Carter Stuck in the Mud 356

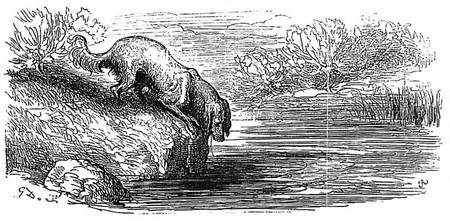

The Doc and the Shadow 360

[Pg vii]

The Bird-Catcher, the Hawk, and the Skylark 361

The Horse and the Ass 363

The Charlatan 365

The Young Widow 368

Discord 373

The Animals Sick of the Plague 375

The Rat Who Retired From the World 381

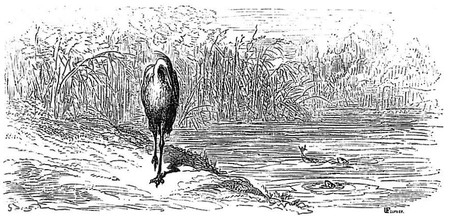

The Heron 383

The Man Badly Married 385

The Maiden 388

The Wishes 393

The Vultures and the Pigeons 396

The Court of the Lion 401

The Milk-Maid and the Milk-Pail 404

The Curate and the Corpse 409

The Man Who Runs After Fortune, and the Man

Who Waits for Her 411

The Two Fowls 416

The Coach and the Fly 420

The Ingratitude and Injustice of Men Towards

Fortune 422

An Animal in the Moon 426

The Fortune-Teller 431

The Cobbler and the Banker 435

The Cat, the Weasel, and the Little Rabbit 440

The Lion, the Wolf, and the Fox 443

The Head and the Tail of the Serpent 448

The Dog Which Carried Round His Neck His

Master's Dinner 451

Death and the Dying Man 456

The Power of Fables 460

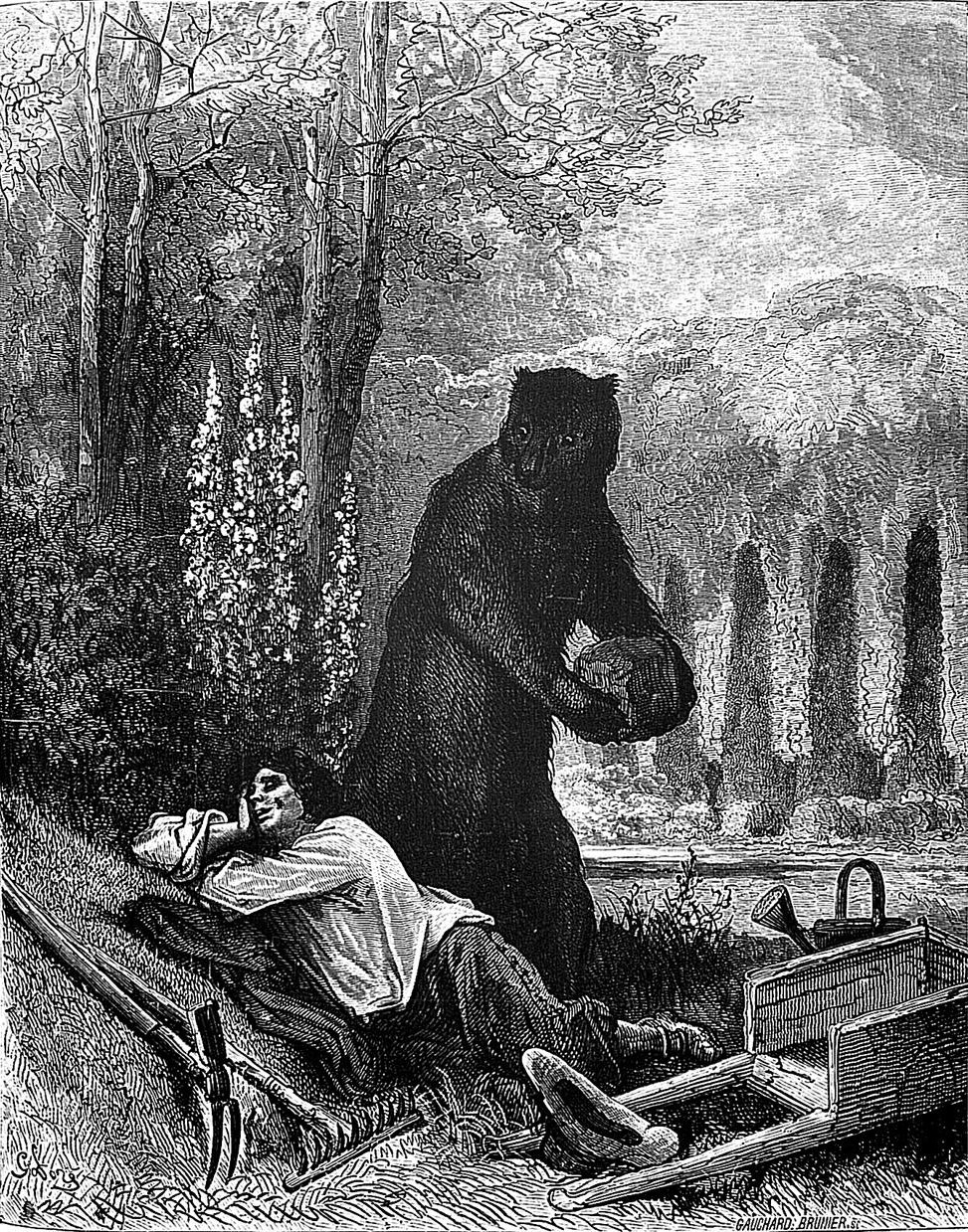

The Bear and the Amateur of Gardening 464

The Man and the Flea 469

The Woman and the Secret 471

Tircis and Amaranth 475

The Joker and the Fishes 479

The Rat and the Oyster 481

The Two Friends 484

The Pig, the Goat, and the Sheep 486

The Rat and the Elephant 488

The Funeral or the Lioness 492

The Bashaw and the Merchant 496

The Horoscope 502

The Torrent and the River 507

The Ass and the Dog 511

The Two Dogs and the Dead Ass 514

The Advantage of Being Clever 520

The Wolf and the Hunter 523

Jupiter and the Thunderbolts 529

The Falcon and the Capon 533

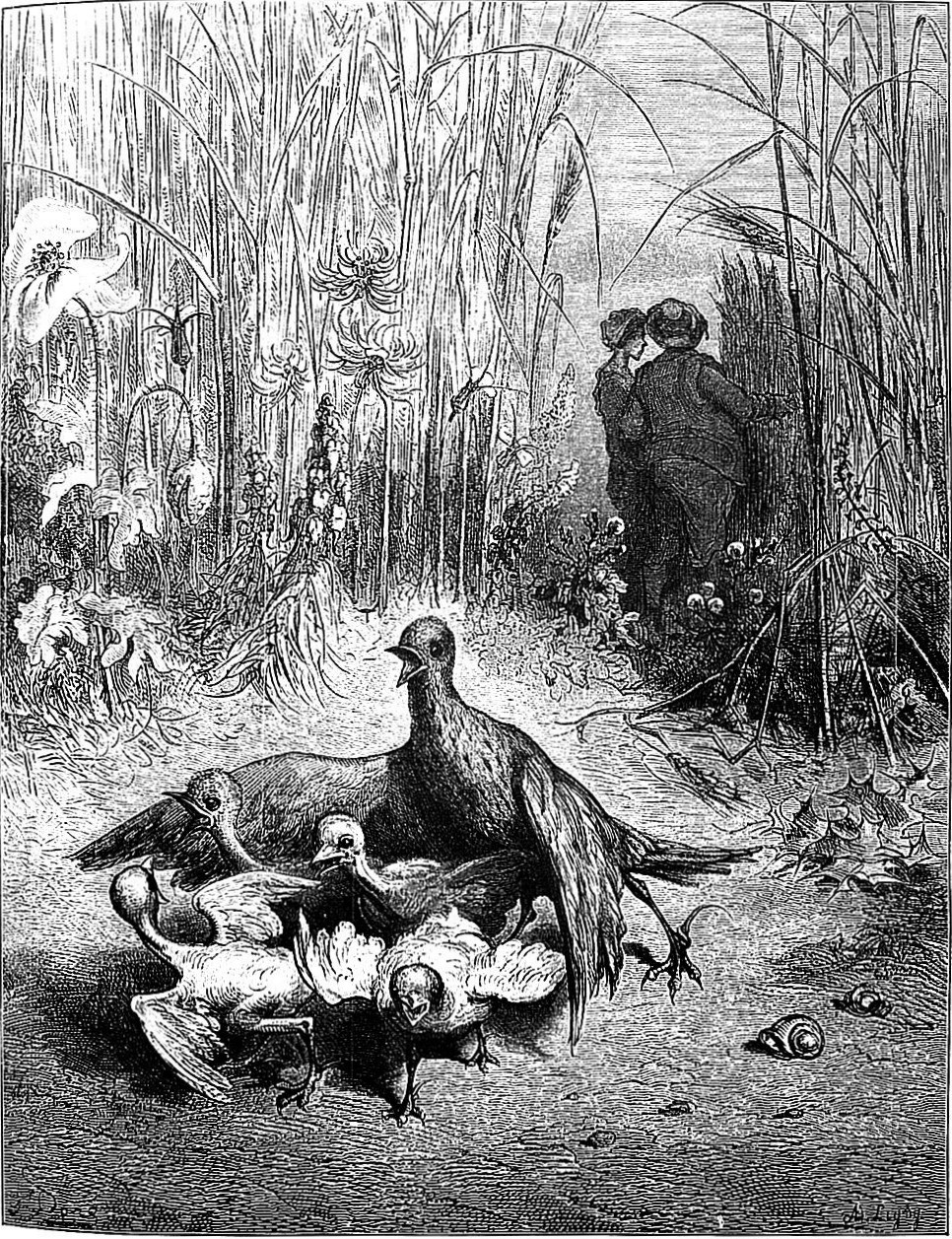

The Two Pigeons 536

Education 543

The Madman Who Sold Wisdom 547

The Cat and the Rat 549

Democritus and the Anderanians 553

The Oyster and Its Claimants 559

The Fraudulent Trustee 561

Jupiter and the Traveller 567

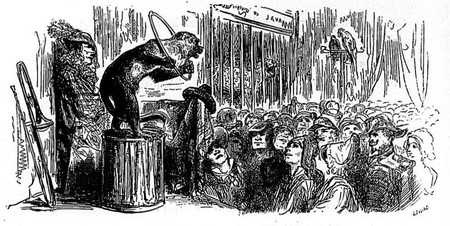

The Ape and the Leopard 571

The Acorn and the Gourd 574

The School-Boy, the Pedant, and the Nursery

Gardener 577

The Cat and the Fox 580

The Sculptor and the Statue of Jupiter 585

The Mouse Metamorphosed Into a Girl 588

The Monkey and the Cat 595

The Wolf and the Starved Dog 597

The Wax Candle 599

"Not Too Much" 601

The Two Rats, the Fox, and the Egg 604

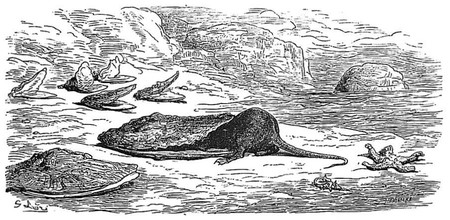

The Cormorant and the Fishes 619

The Husband, the Wife, and the Robber 624

The Shepherd and the King 627

The Two Men and the Treasure 635

The Shepherd and His Flock 637

The Kite and the Nightingale 639

The Fish and the Shepherd Who Played on

the Clarionet 643

The Man and the Snake 645

[Pg viii]

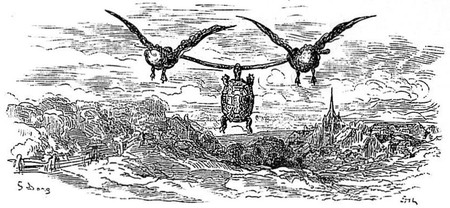

The Tortoise and the Two Ducks 650

The Two Adventurers and the Talisman 655

The Miser and his Friend 659

The Wolf and the Peasants 662

The Rabbits 667

The Swallow and the Spider 672

The Partridge and the Fowls 674

The Lion 676

The Dog Whose Ears Were Cut 682

The Two Parrots, the Monarch, and His Son 684

The Peasant of the Danube 688

The Lioness and She-Bear 695

The Merchant, the Nobleman, the Shepherd, and

the King's Son 697

The Old Man and the Three Young Men 700

The Gods as Instructors of Jupiter's Son 705

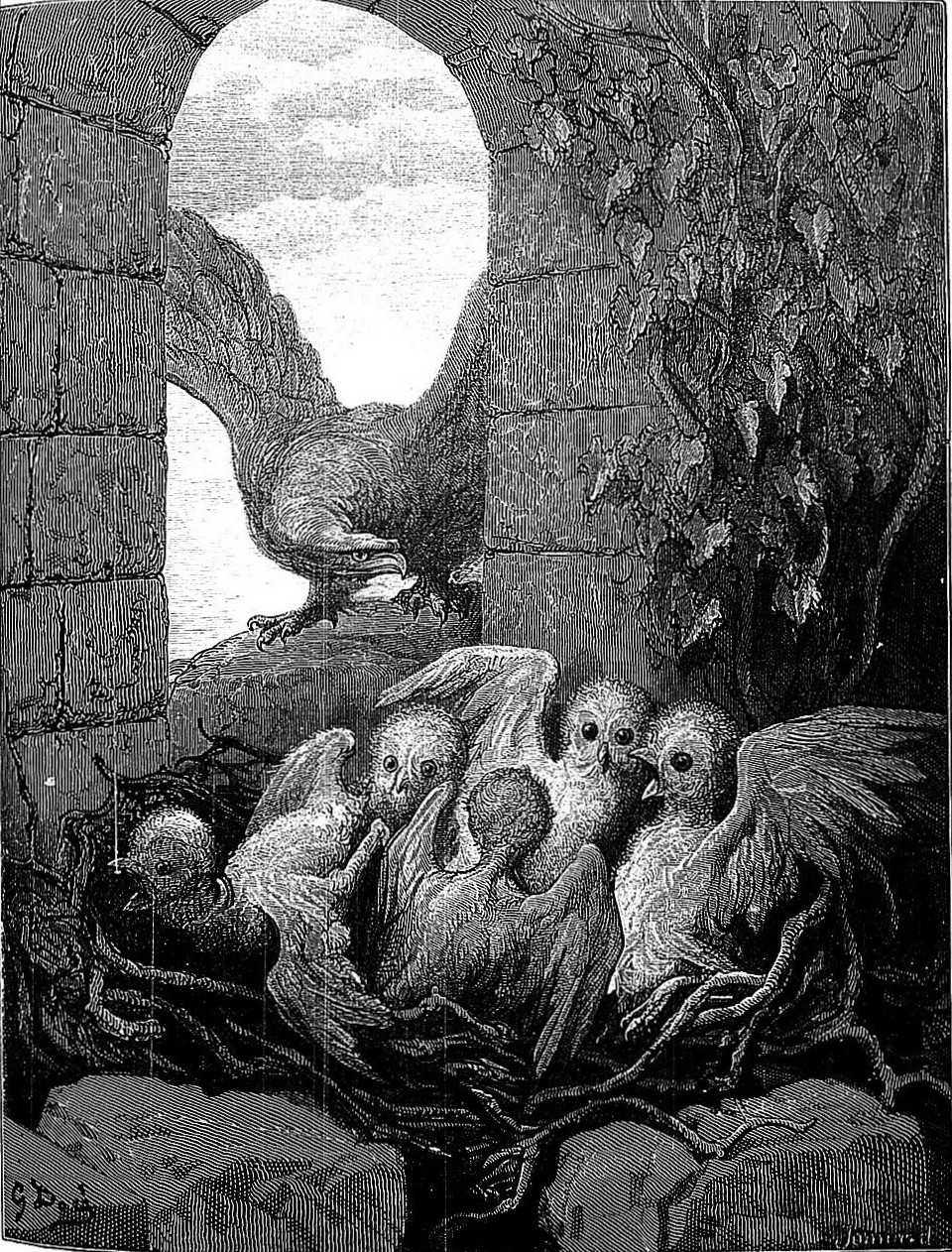

The Owl and the Mice 708

The Companions of Ulysses 713

The Farmer, the Dog, and the Fox 721

The Dream of an Inhabitant of Mogul 725

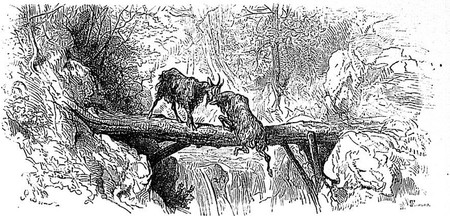

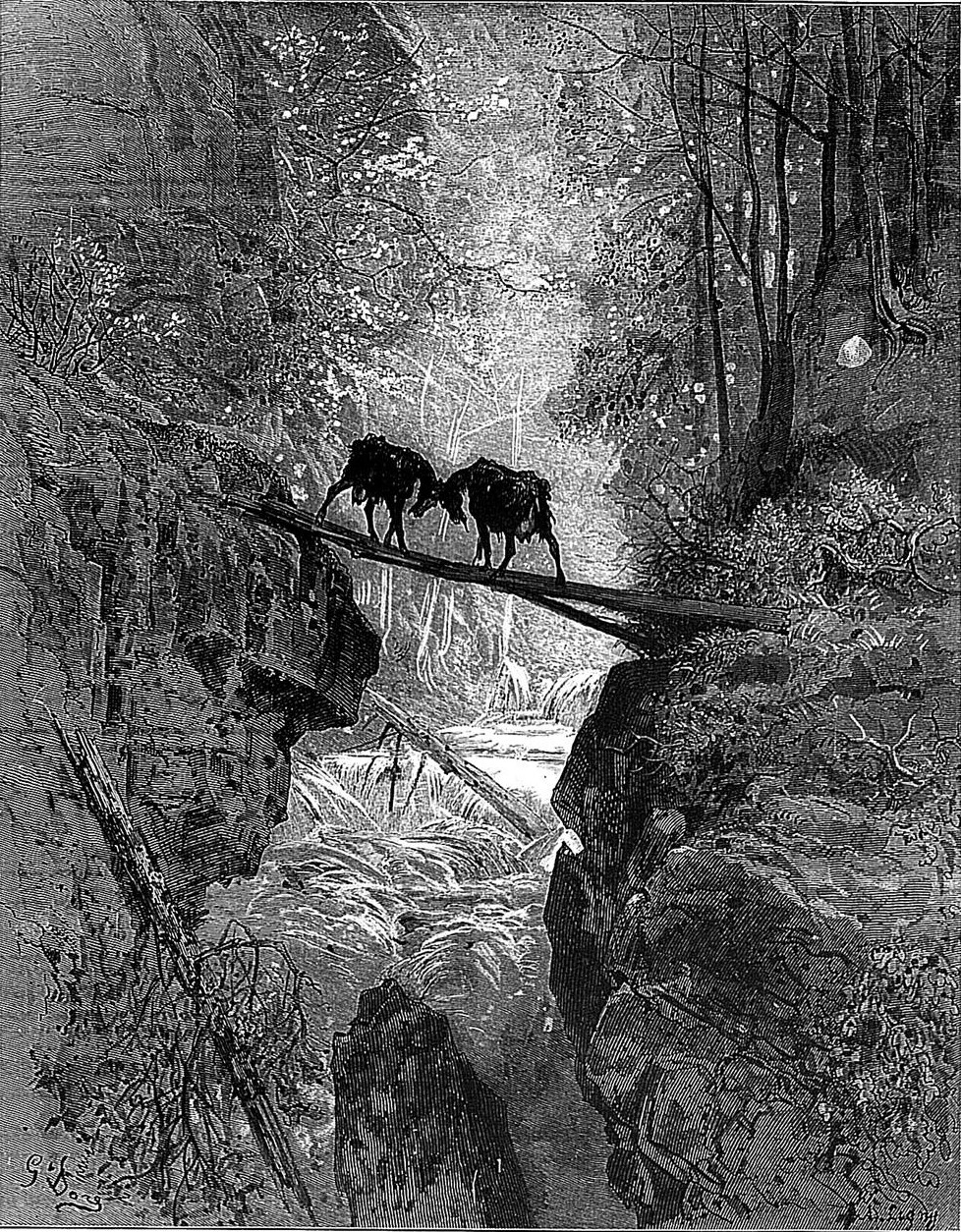

The Two Goats 728

The Lion, the Ape, and the Two Asses 733

The Wolf and the Fox 737

The Sick Stag 740

The Cat and the Two Sparrows 744

The Miser and the Ape 747

To the Duke of Burgundy 750

The Old Cat and the Young Mouse 752

The Bat, the Bush, and the Duck 754

The Eagle and the Magpie 759

The Quarrel of the Dogs and the Cats; and,

Also, That of the Cats and

the Mice 762

Love and Folly 767

The Wolf and the Fox 770

The Crab and Its Daughter 774

The Forest and the Woodman 776

The Fox, the Flies, and the Hedge-Hog 780

The Hawk, the King, and the Falcon 782

The Fox and the Turkeys 791

The Crow, the Gazelle, the Tortoise, and the Rat 793

The English Fox 803

The Ape 807

The Fox, the Wolf, and the Horse 809

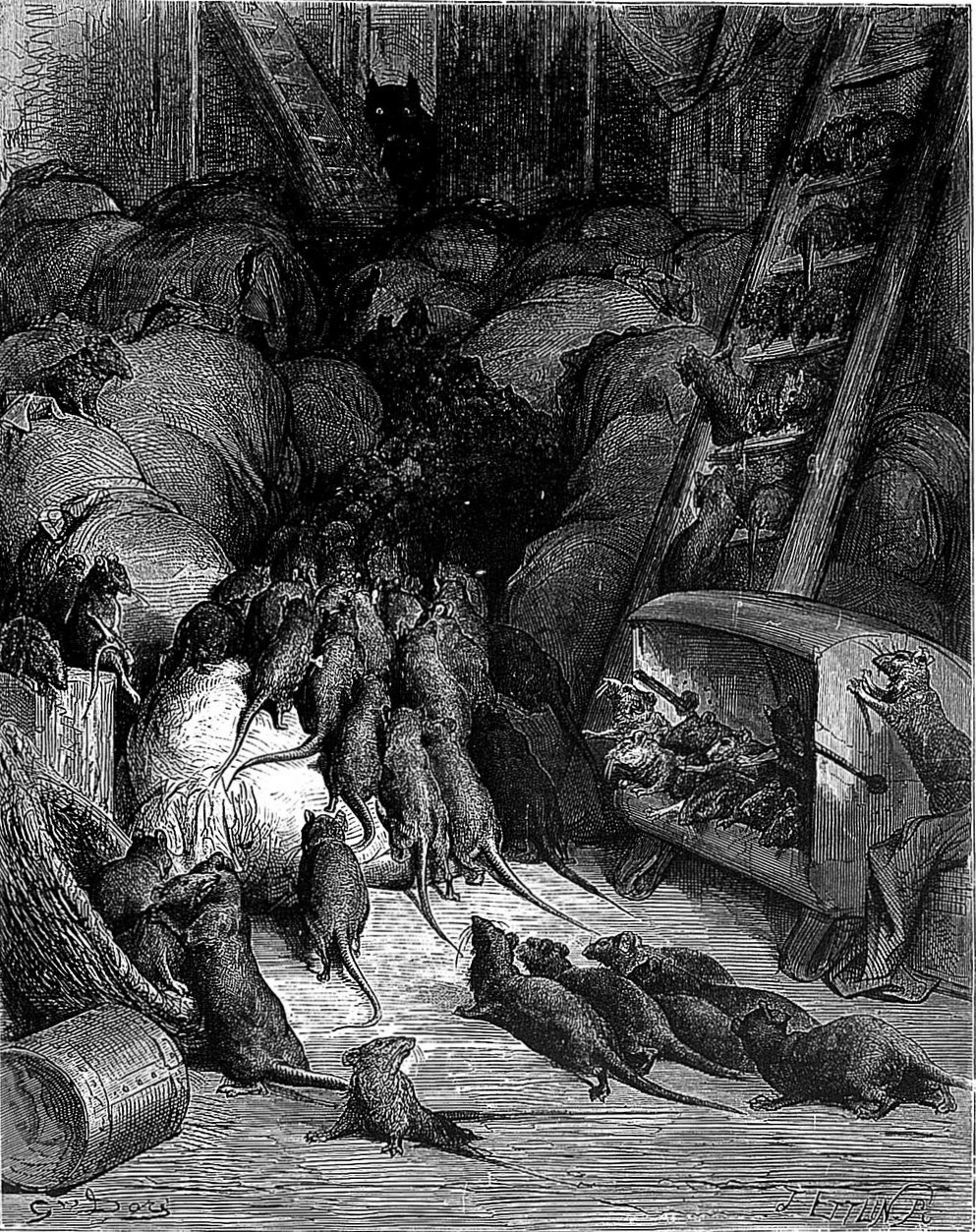

The League of the Rats 812

A Scythian Philosopher 817

Daphnis and Alcimadura 820

The Elephant and Jupiter's Monkey 826

The Madman and the Philosopher 829

The Frogs and the Sun 831

The Arbitrator, Almoner, and Hermit 833[Pg ix]

LIST OF FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS.

The Grasshopper and the Ant 1

The Two Mules 9

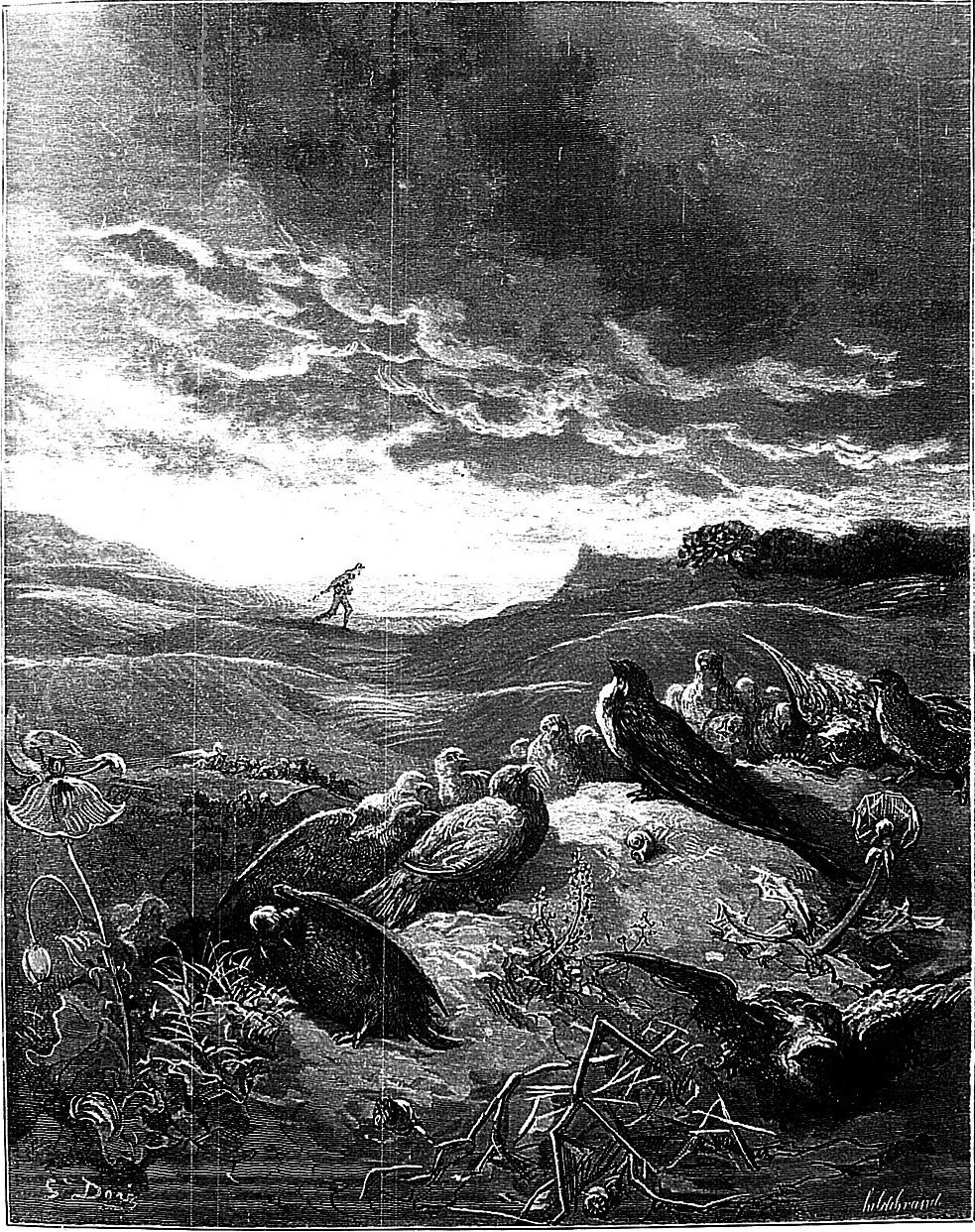

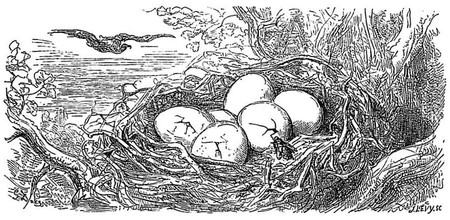

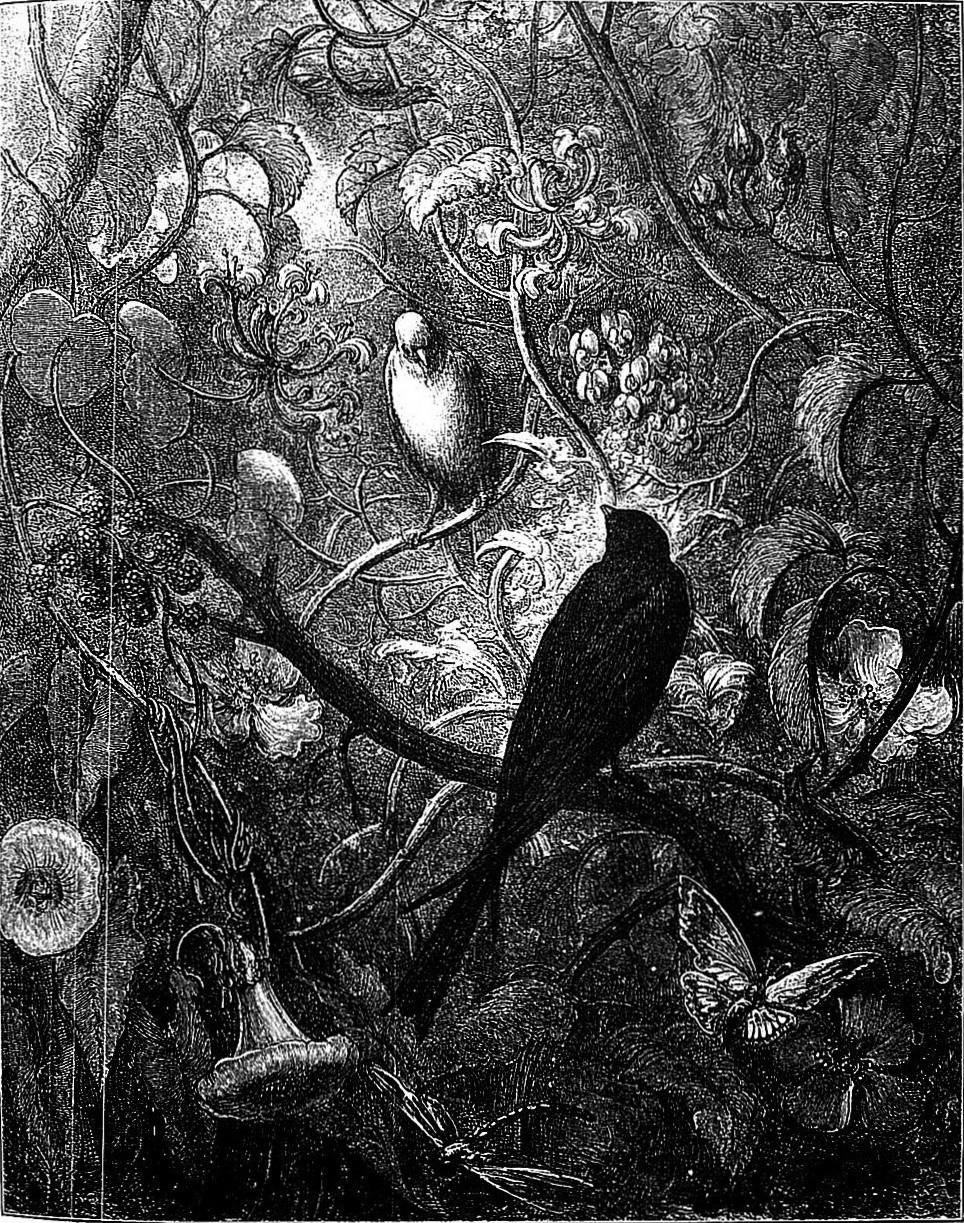

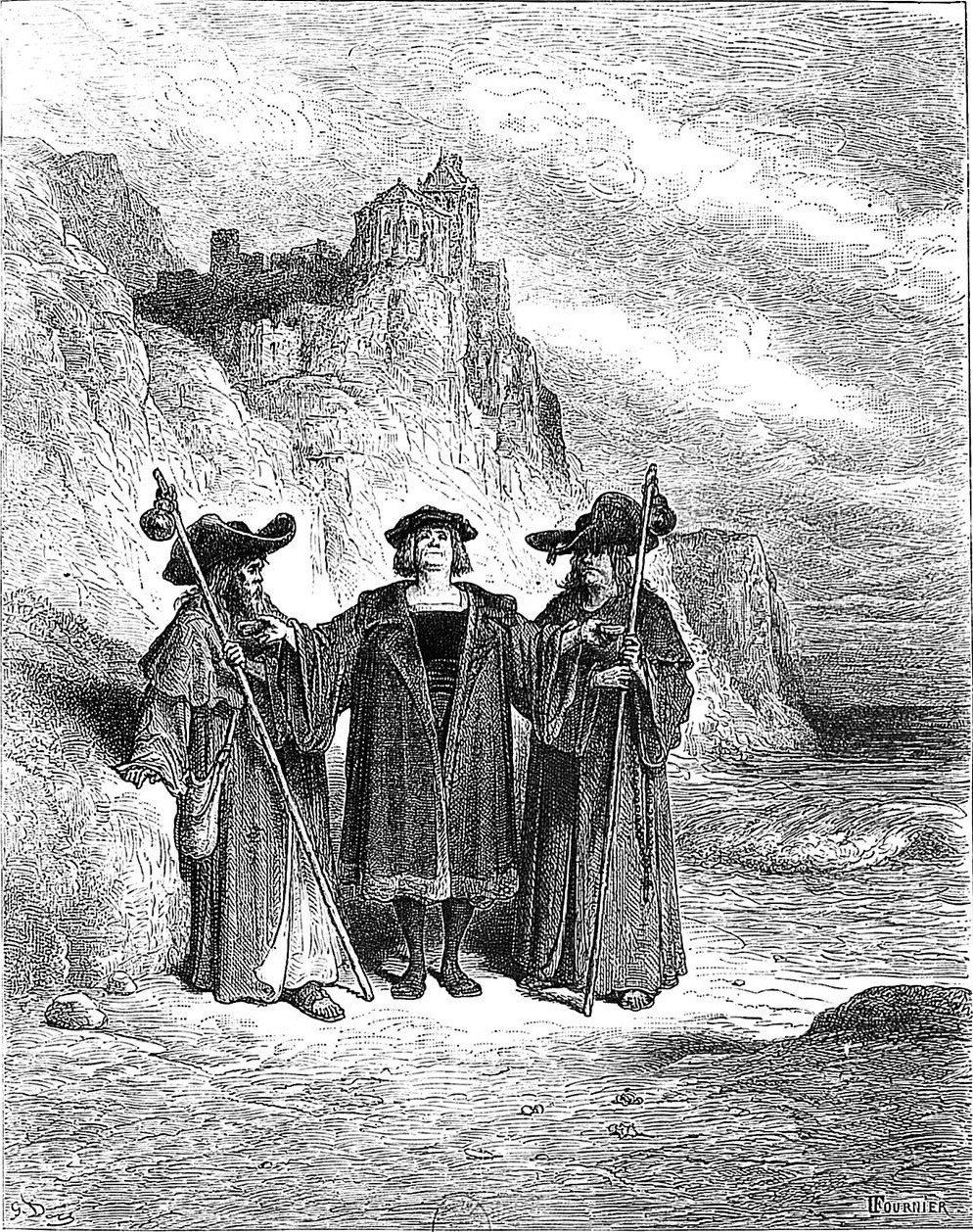

The Swallow and the Little Birds 21

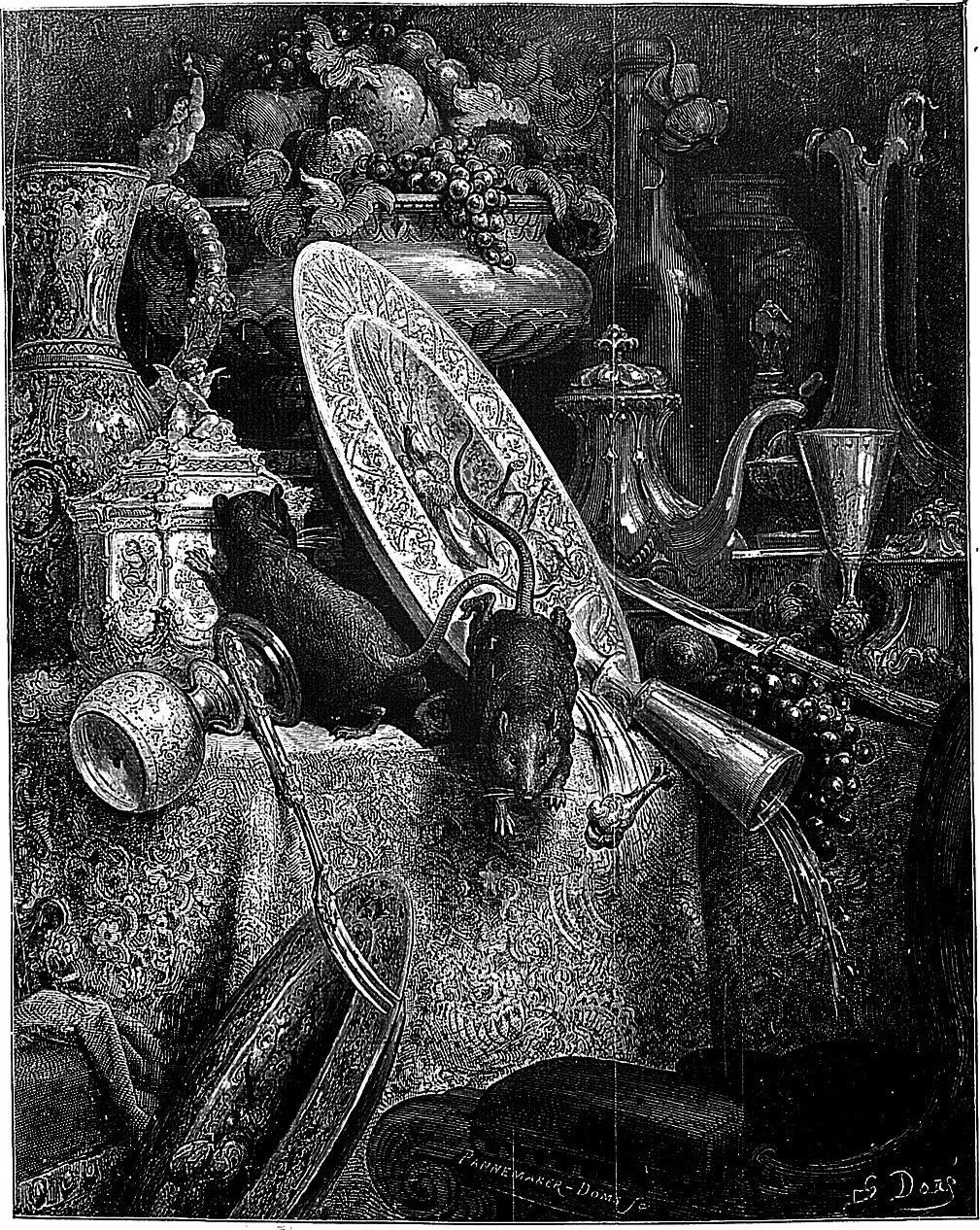

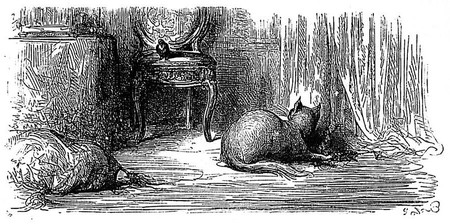

The Town Rat and the Country Rat 25

The Wolf and the Lamb 33

The Robbers and the Ass (To face page) 38

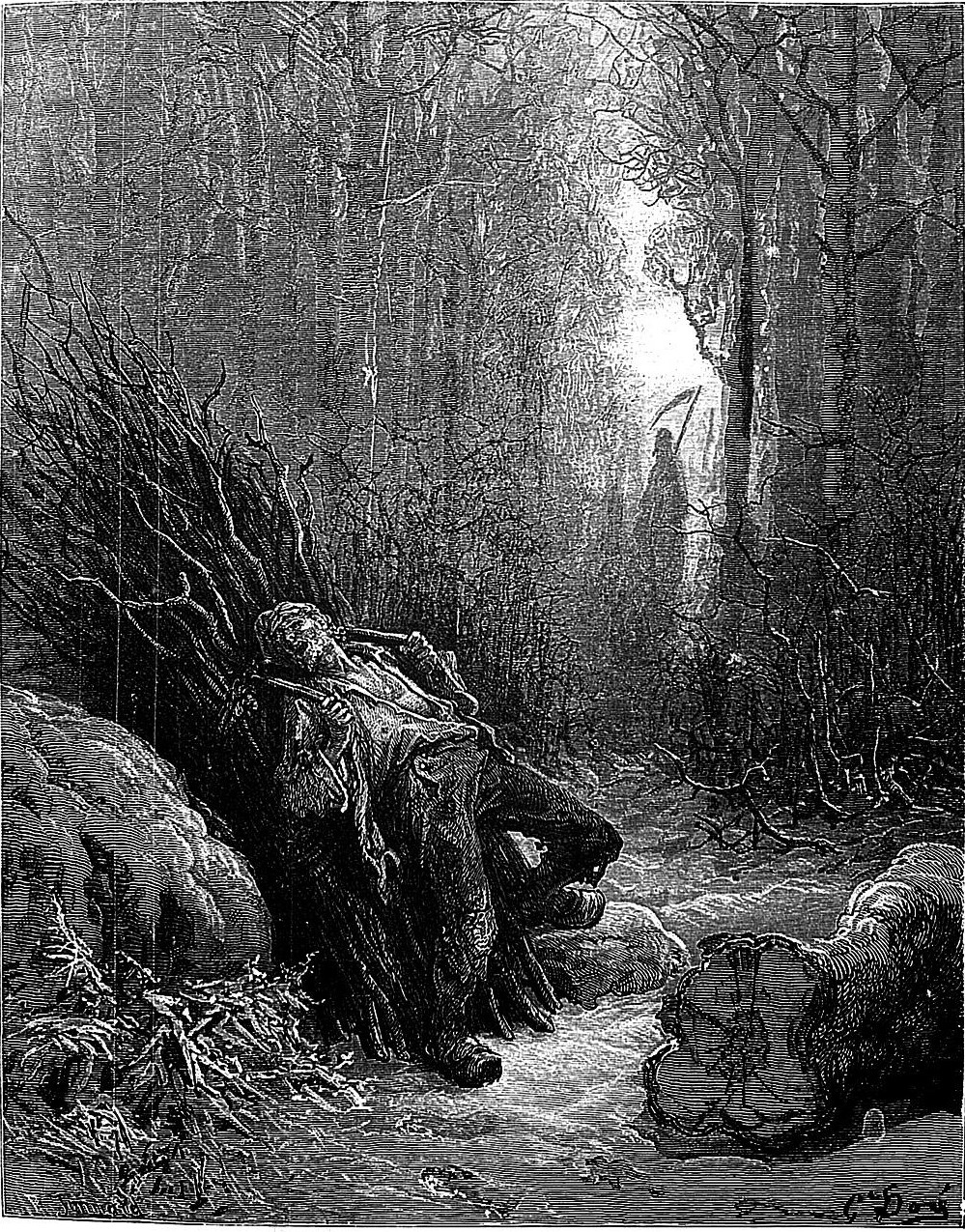

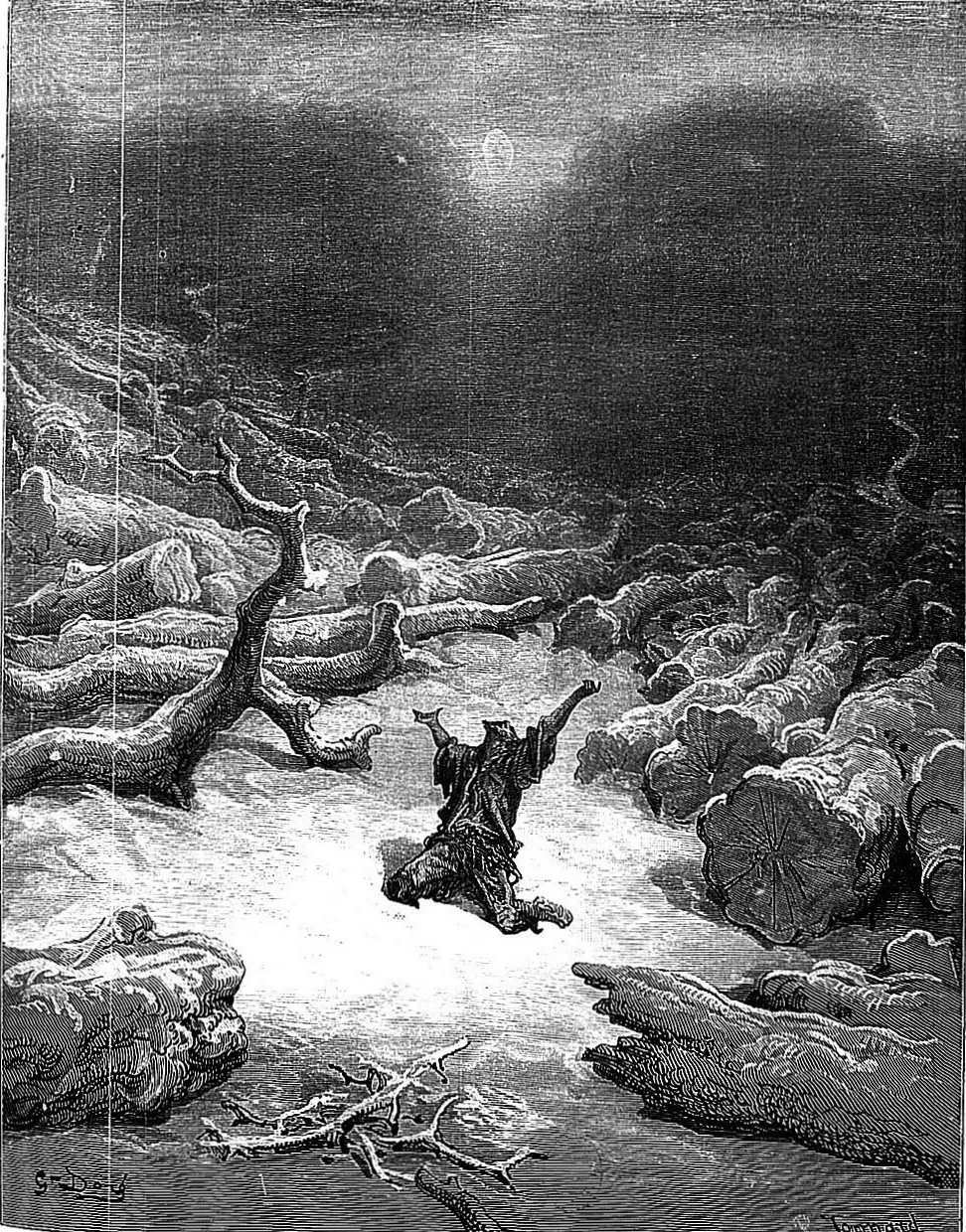

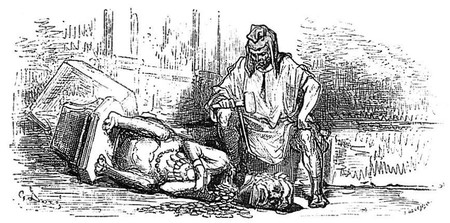

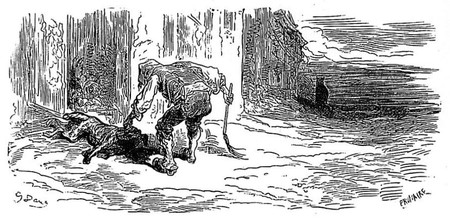

Death and the Woodcutter 41

The Wolf Turned Shepherd 49

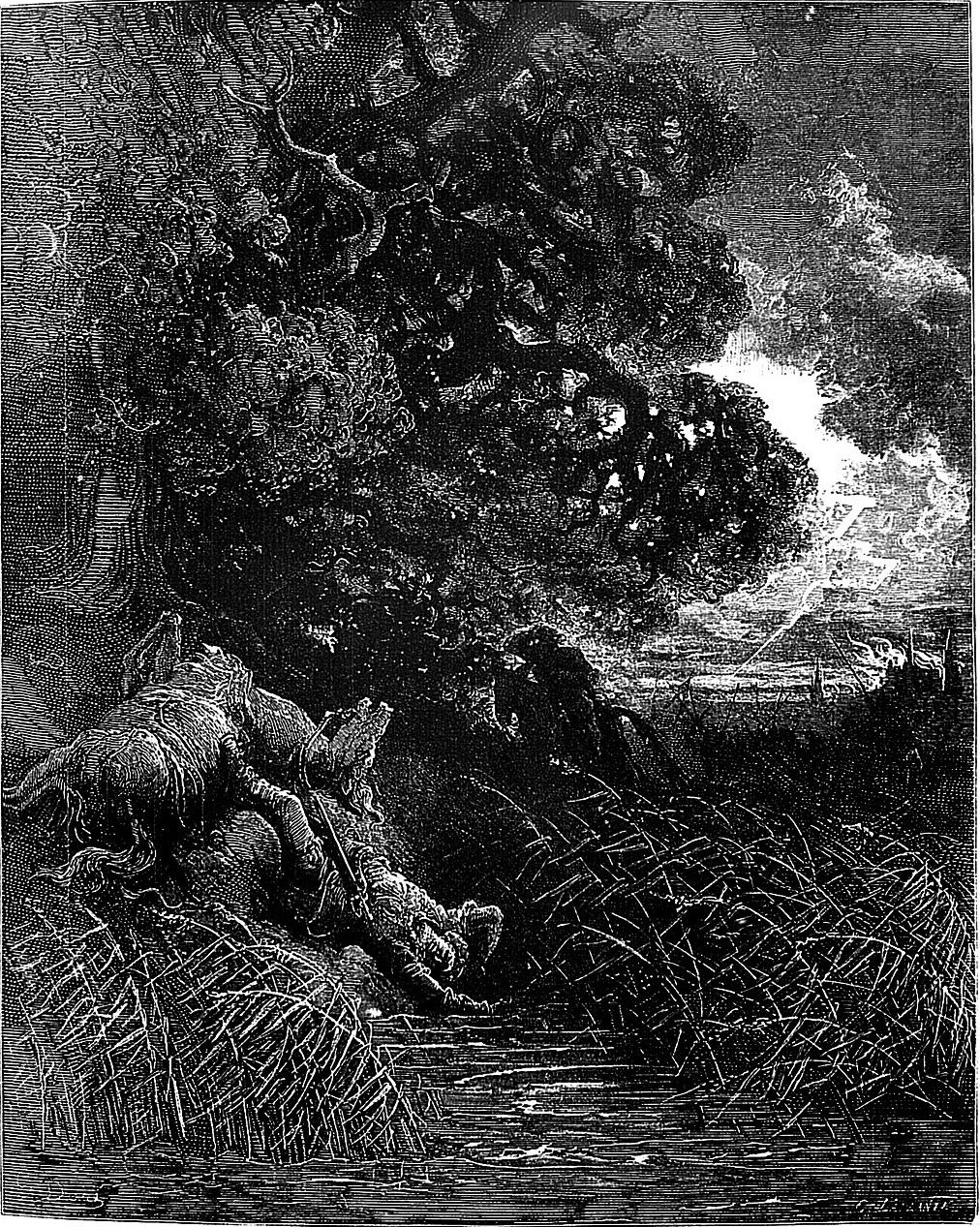

The Oak and the Reed 60

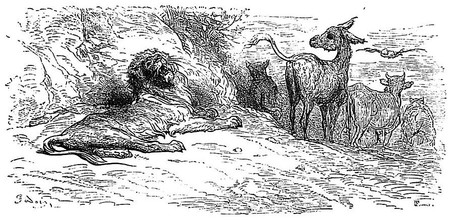

The Council Held by the Rats 68

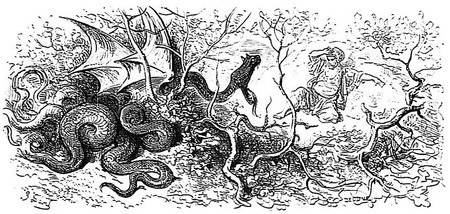

The Lion and the Gnat 77

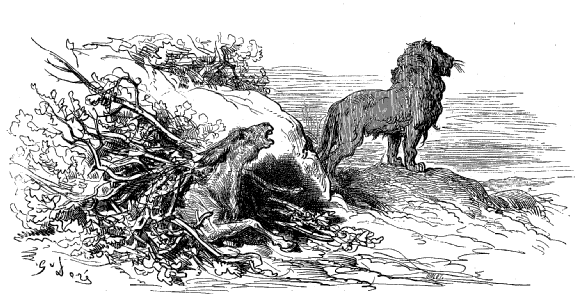

The Lion and the Rat 85

The Hare and the Frogs 93

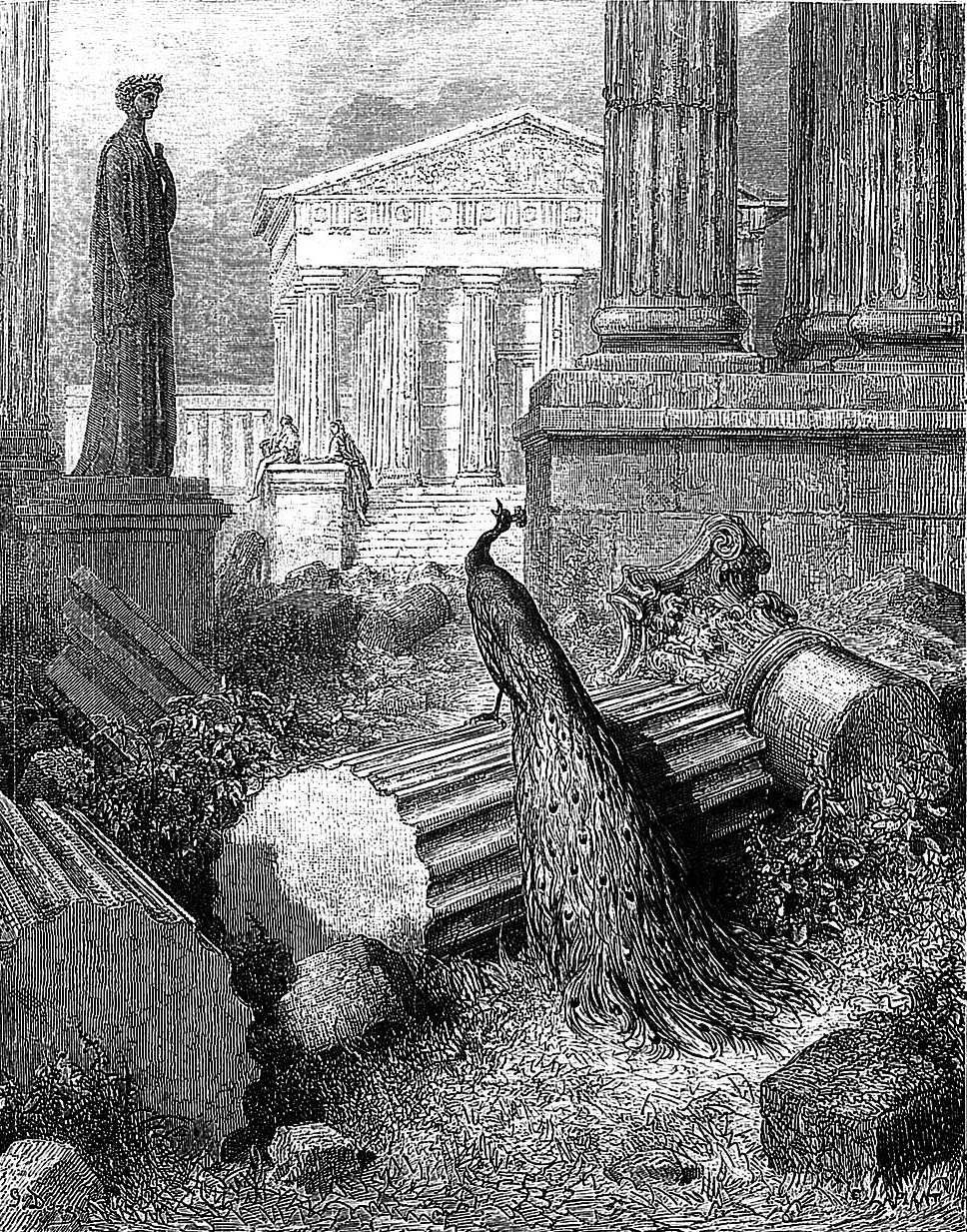

The Peacock Complaining to Juno 100

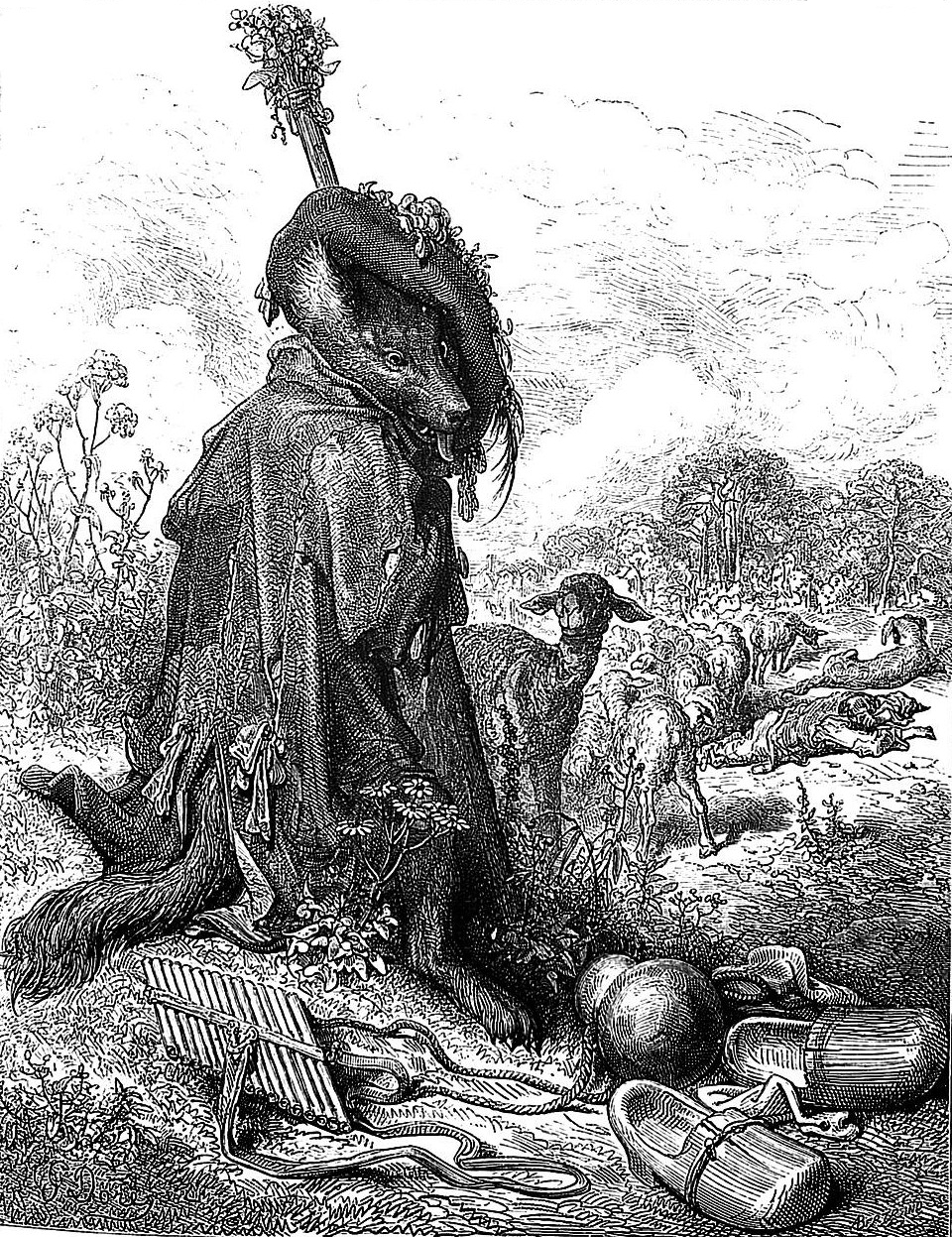

The Miller, His Son, and the Ass 109

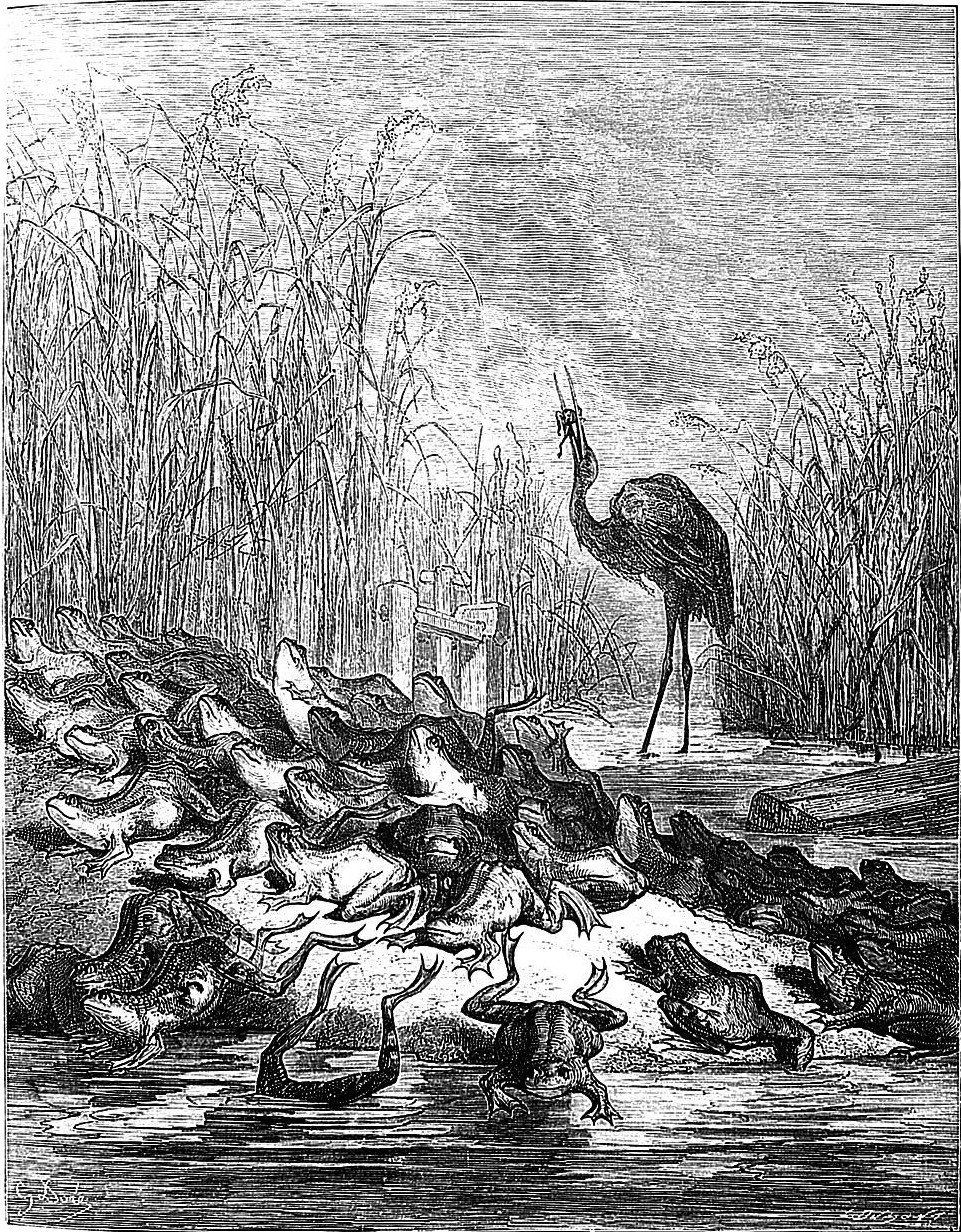

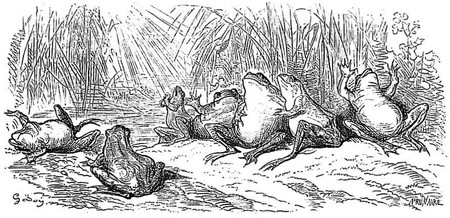

The Frogs Who Asked For a King 117

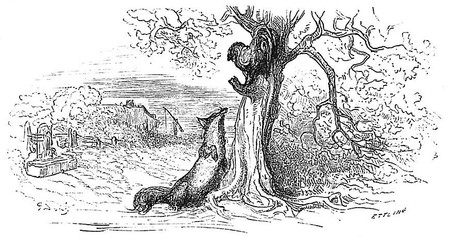

The Fox and the Grapes 124

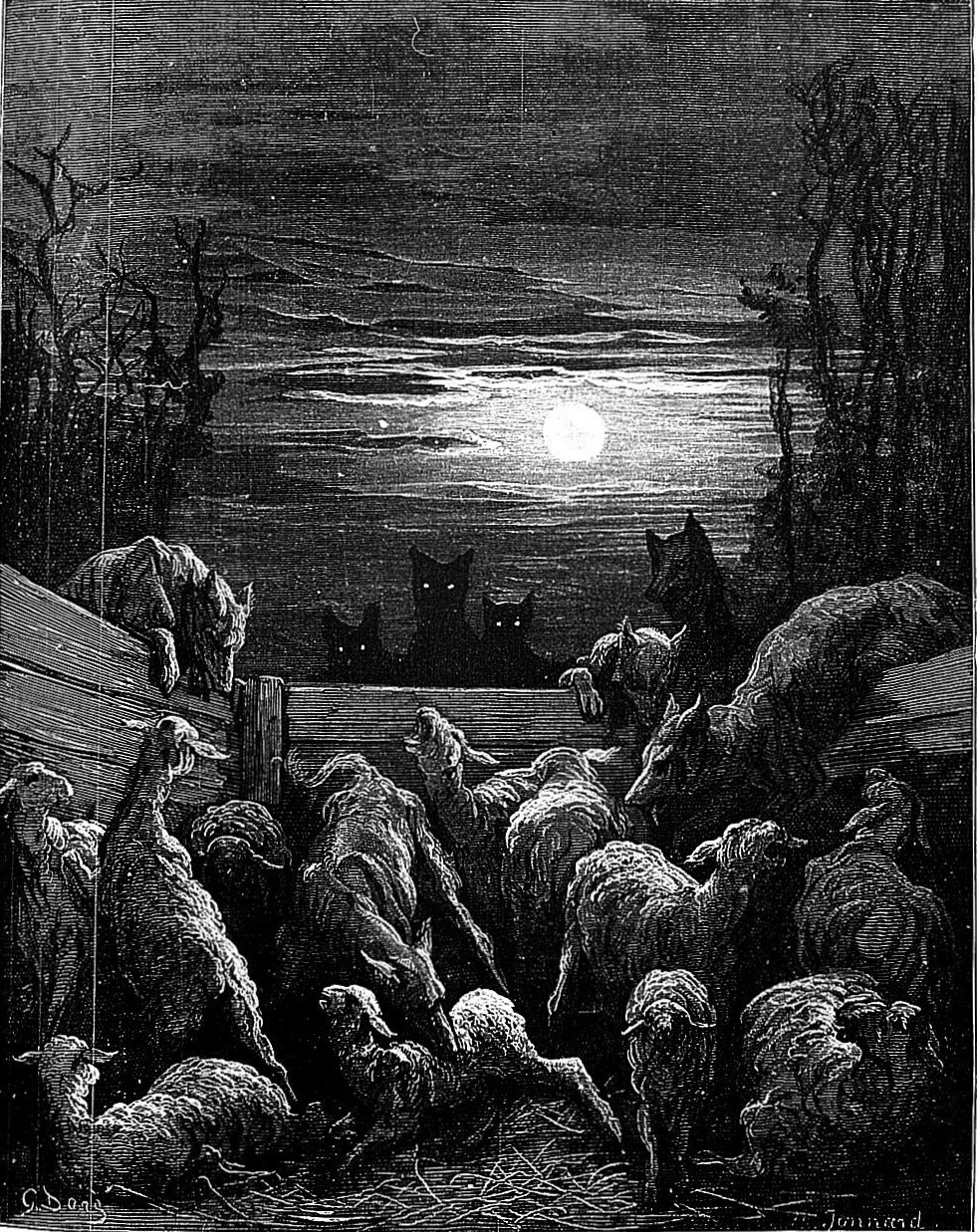

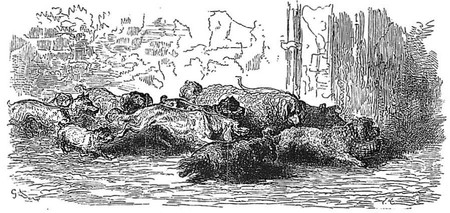

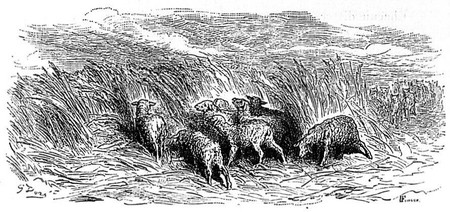

The Wolves and the Sheep 133

Philomel and Progne 140

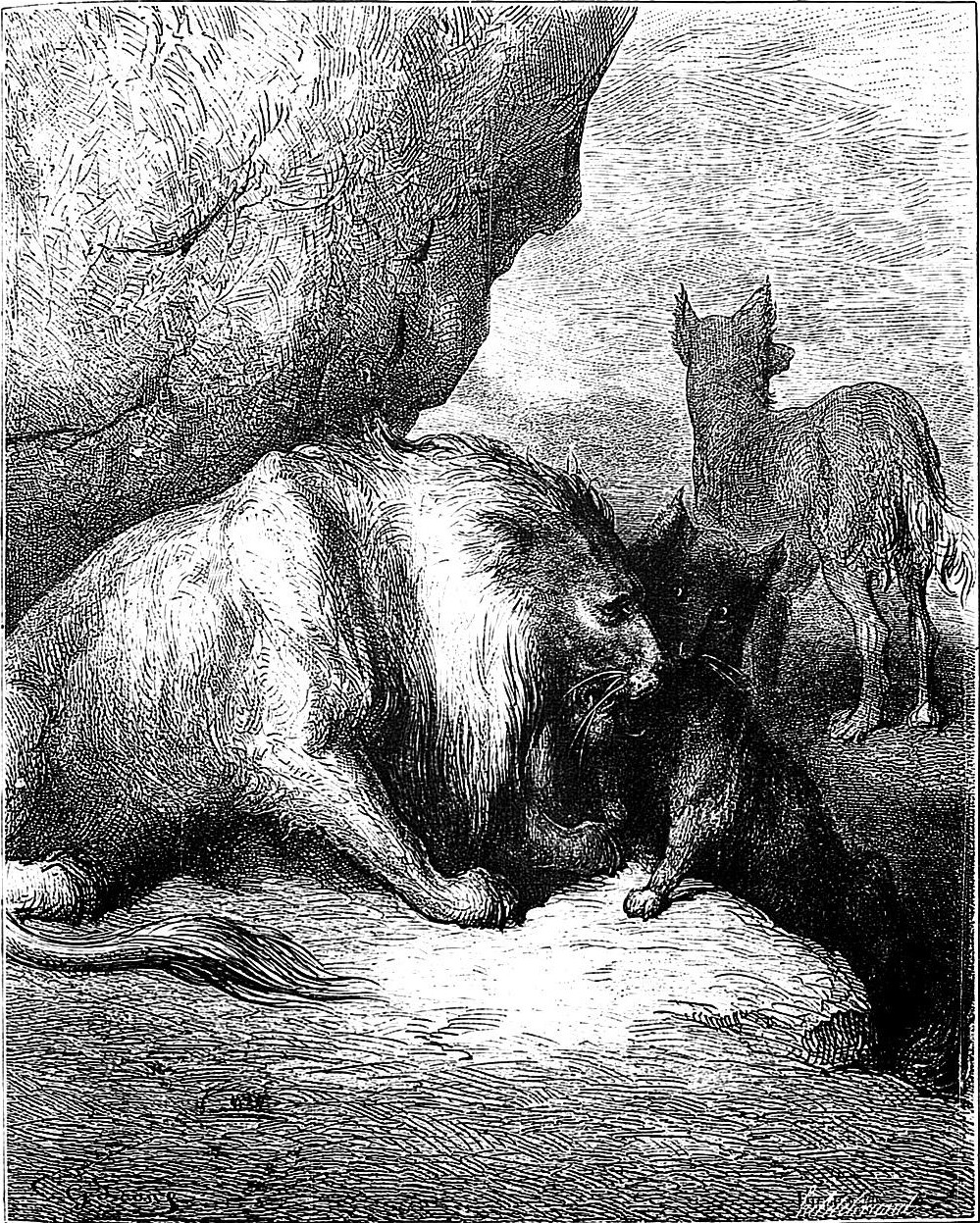

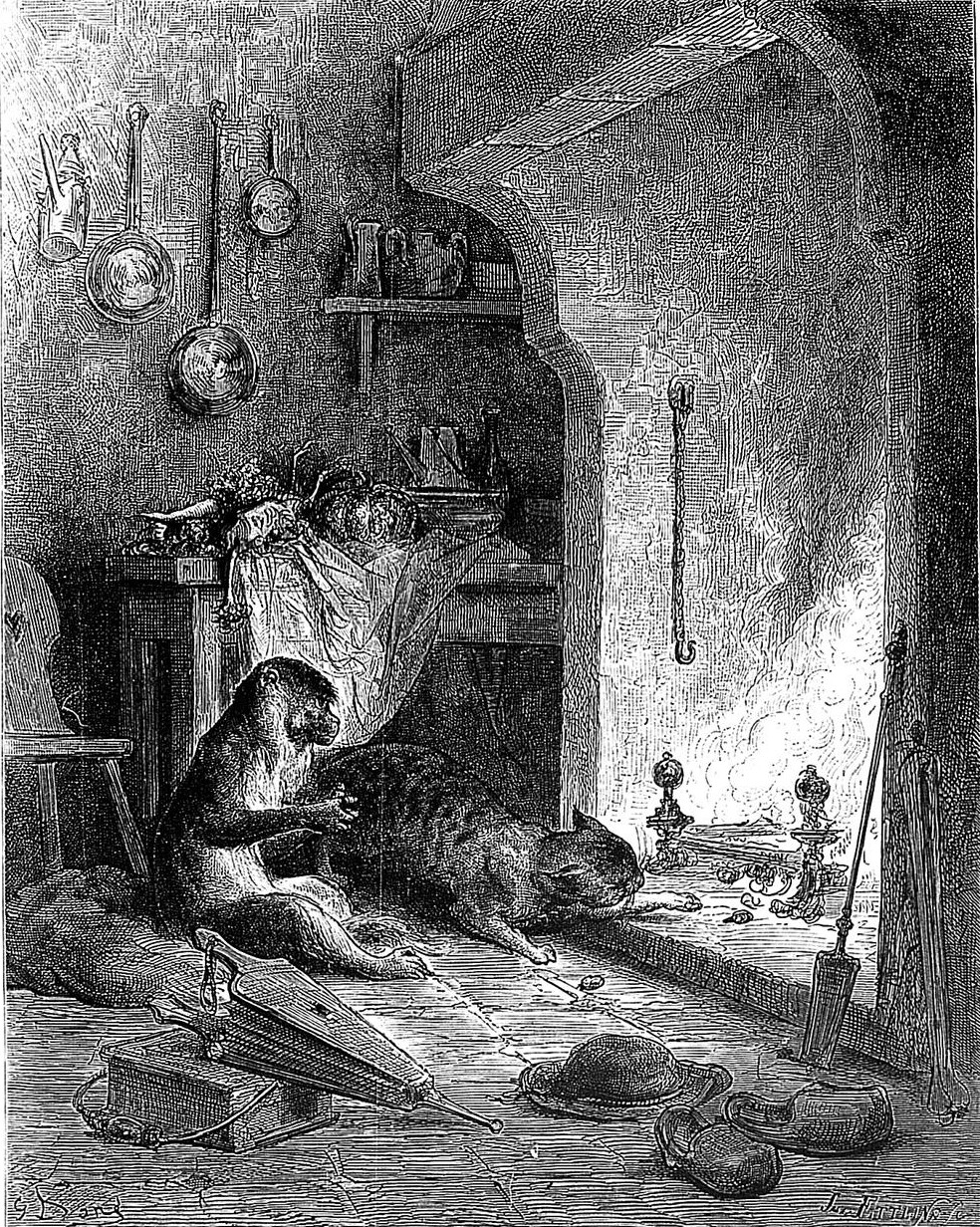

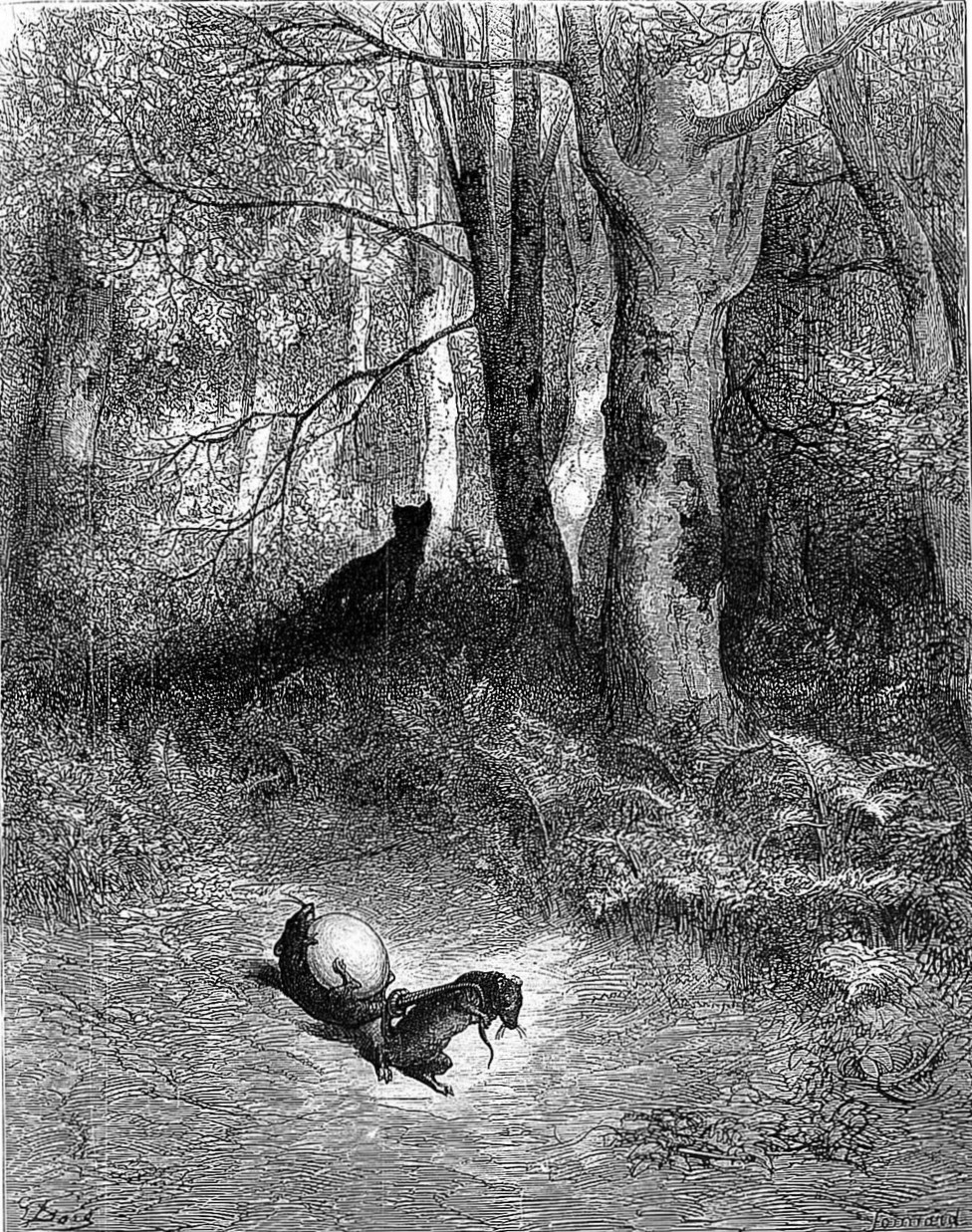

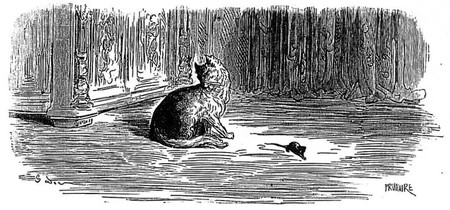

The Cat and the Old Rat 148

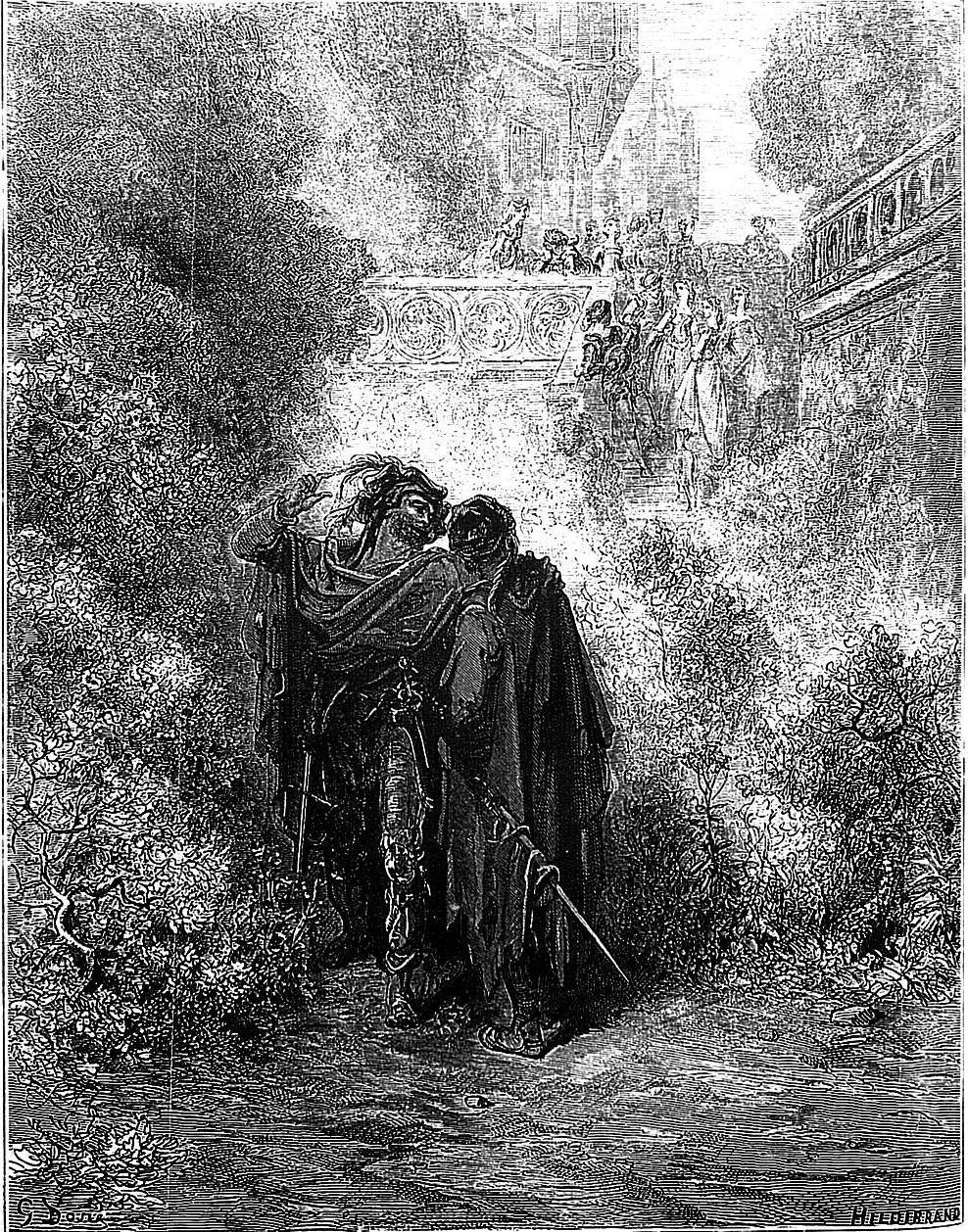

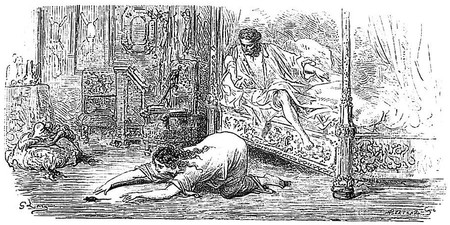

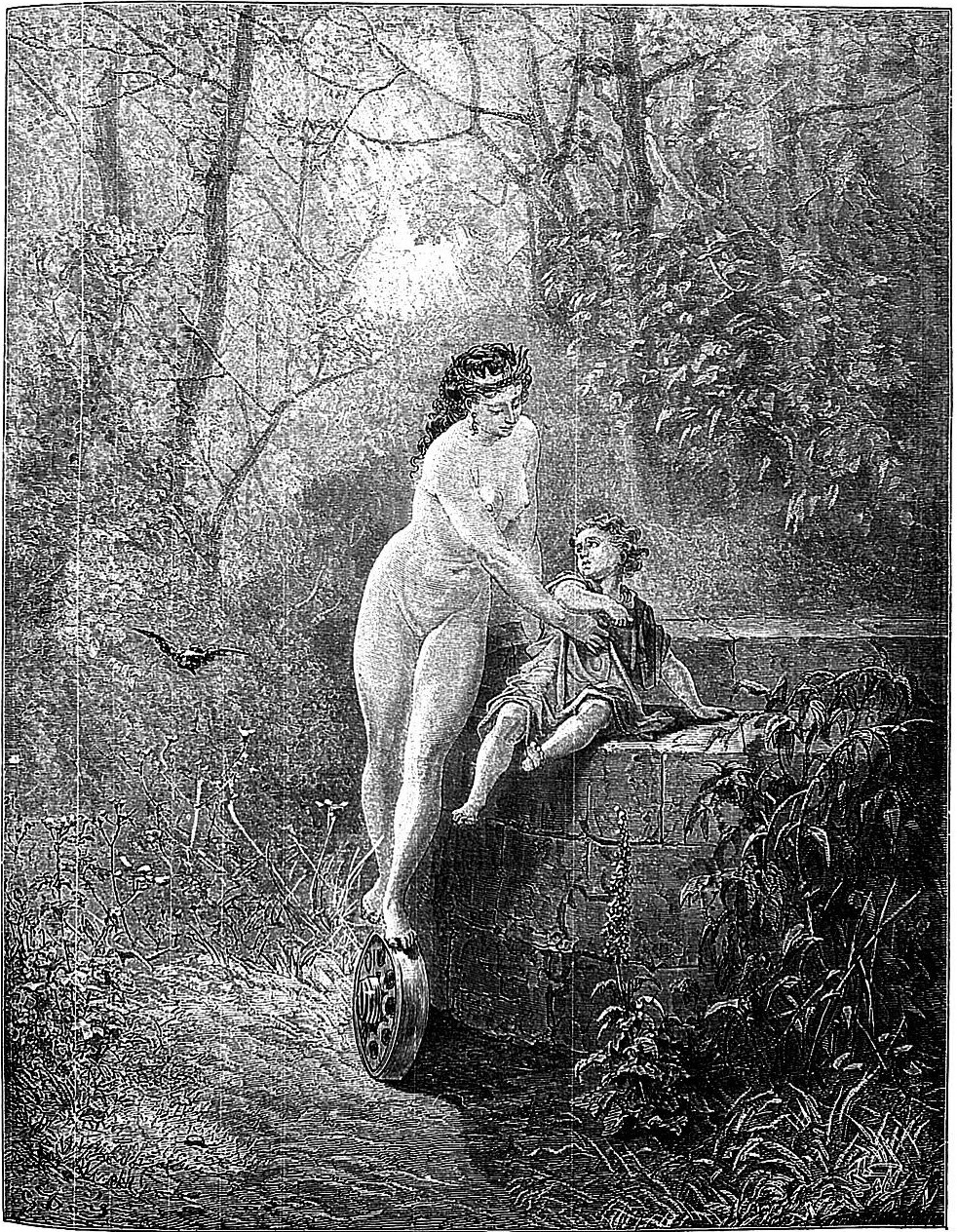

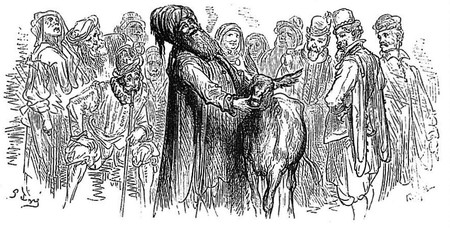

The Lion in Love 157

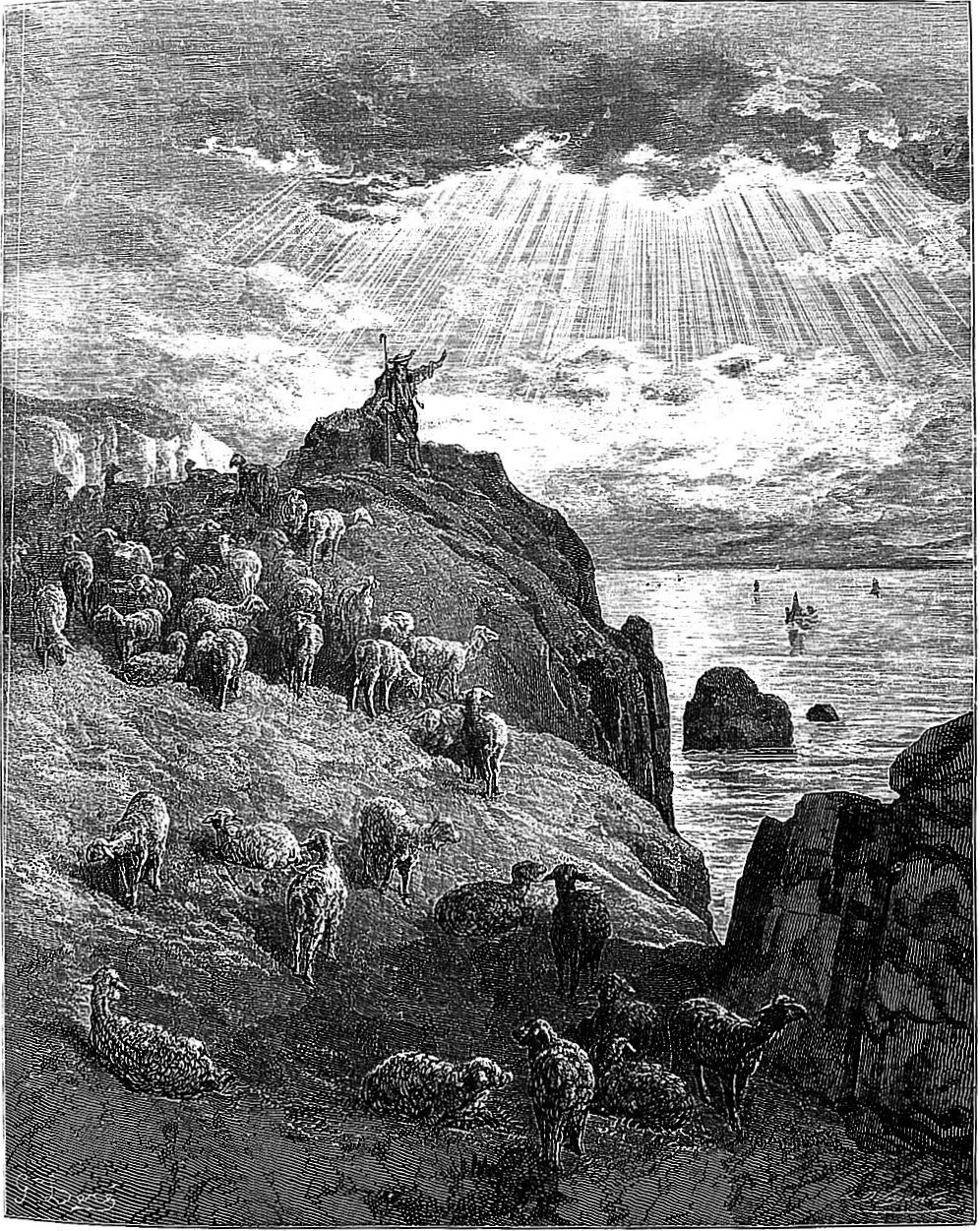

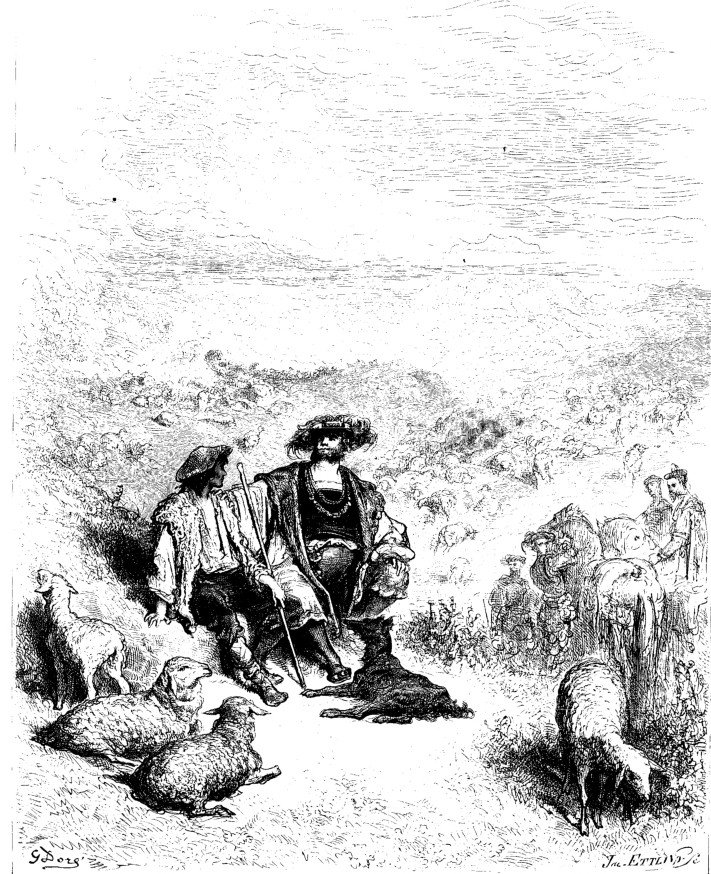

The Shepherd and the Sea 164

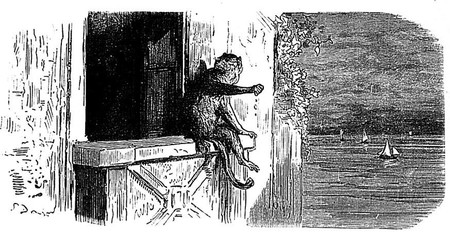

The Monkey and the Dolphin 173

The Miser Who Lost His Treasure 181

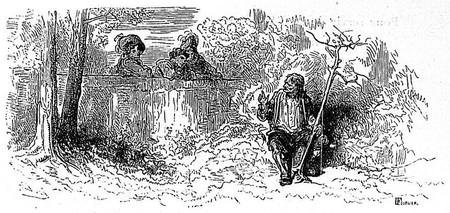

The Eye of the Master 189

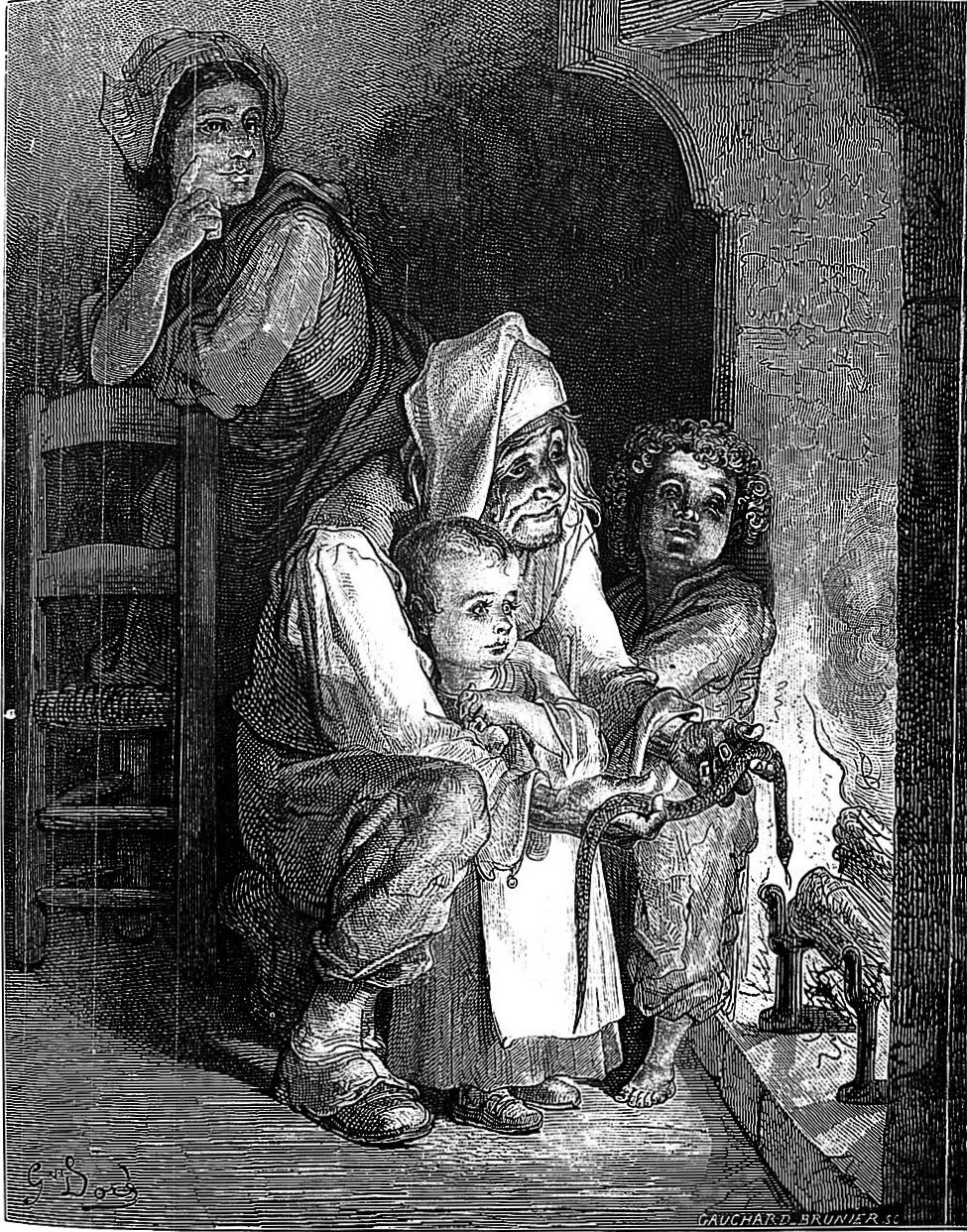

The Wolf, the Mother, and the Child 201

The Lark and Her Little Ones 213

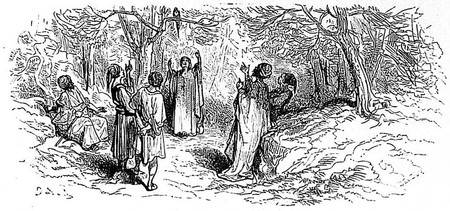

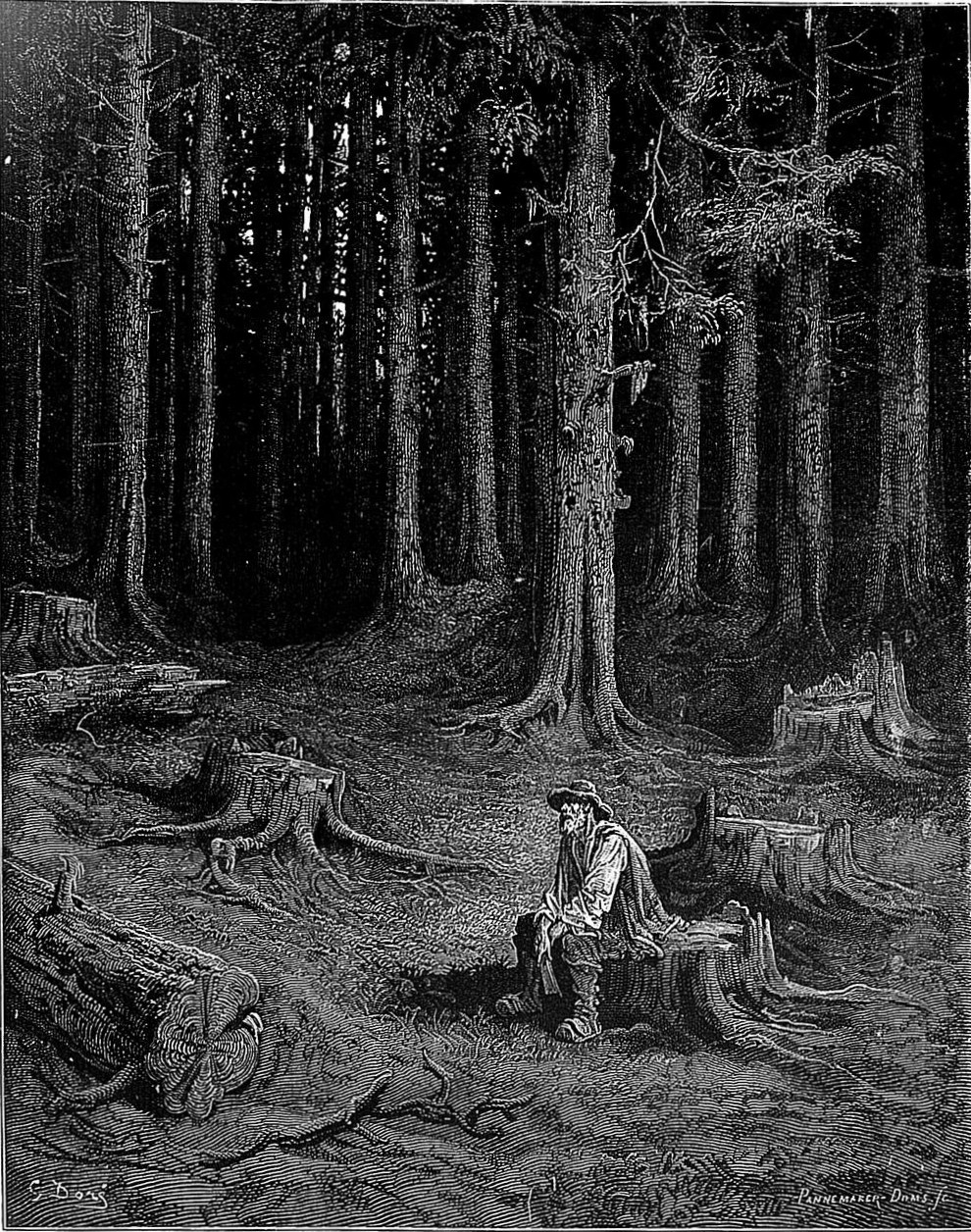

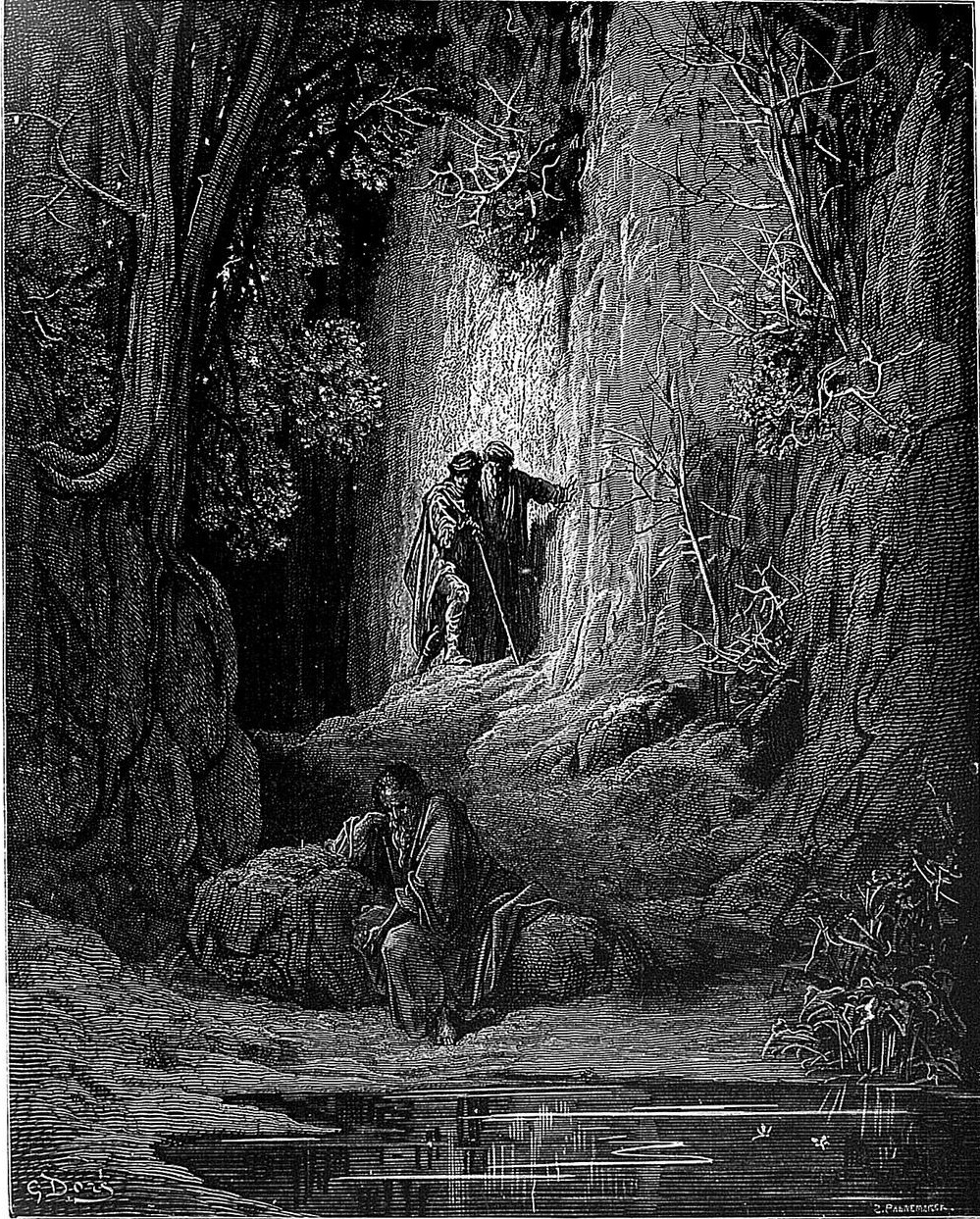

The Woodman and Mercury 225

[Pg x]

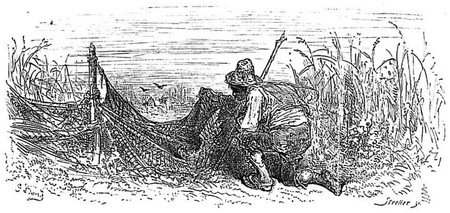

The Little Fish and the Fisherman 236

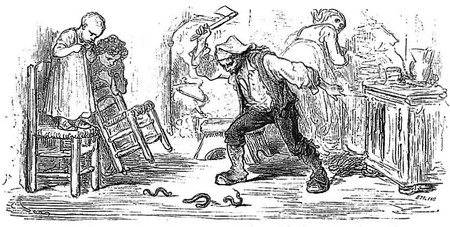

The Old Woman and Her Servants 249

The Horse and the Wolf 261

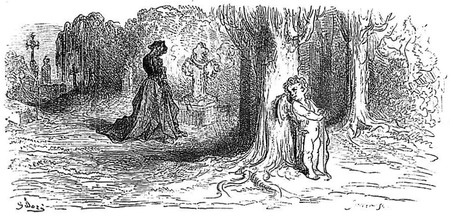

Fortune and the Little Child 273

The Doctors 285

The Hen With the Golden Eggs 293

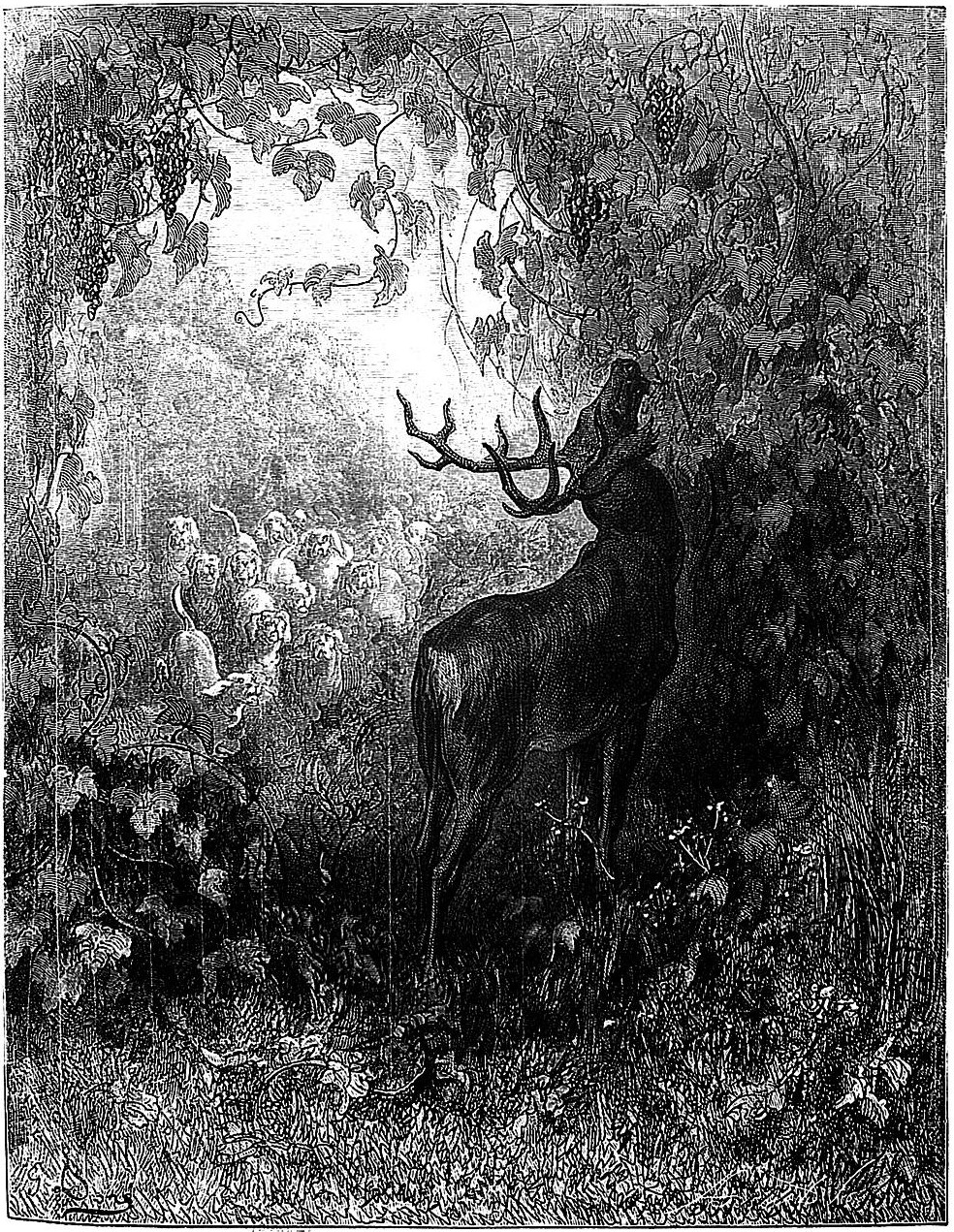

The Stag and the Vine 301

The Eagle and the Owl 309

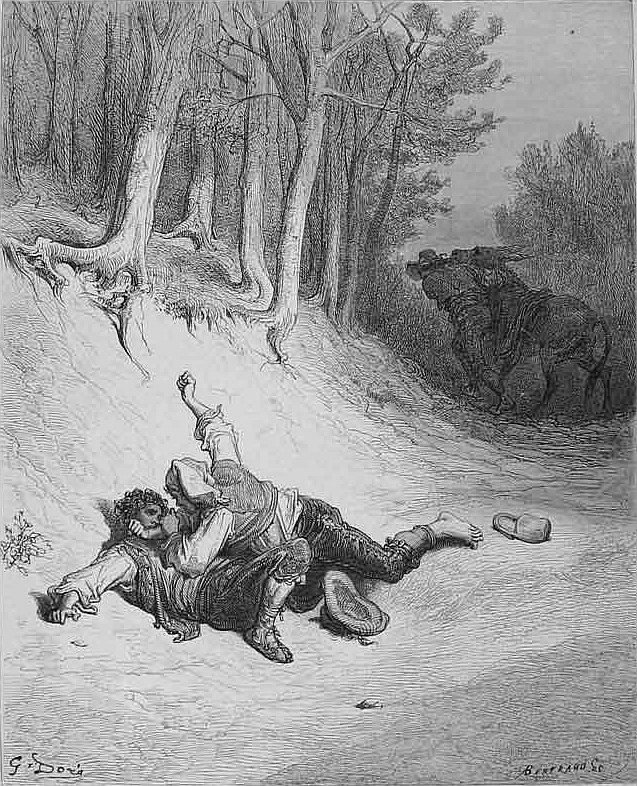

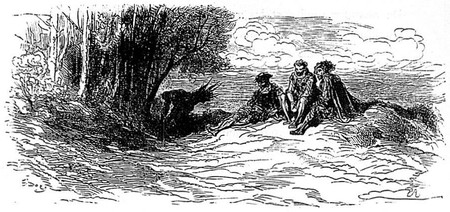

The Bear and the Two Friends 321

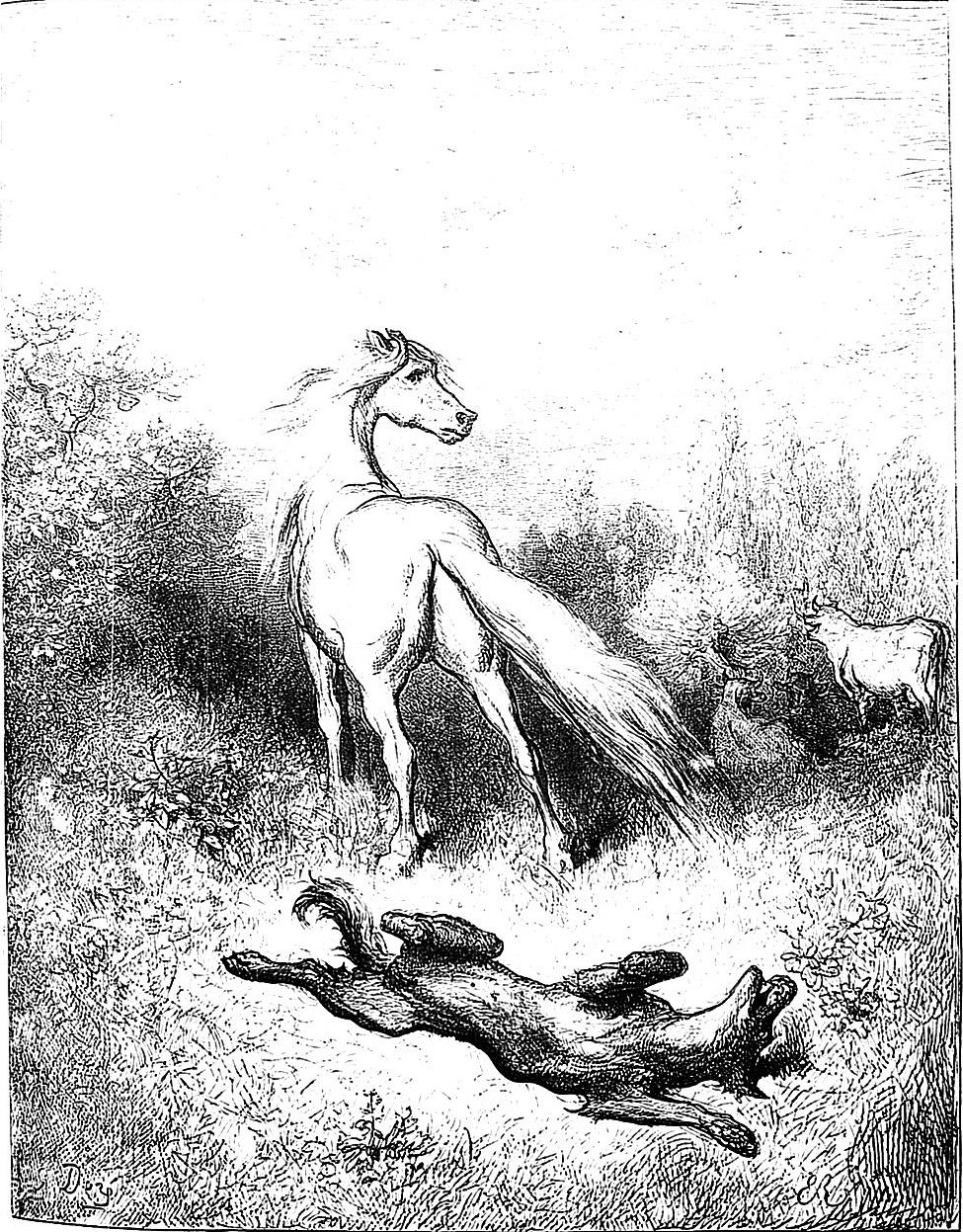

The Stag Viewing Himself in the Stream 329

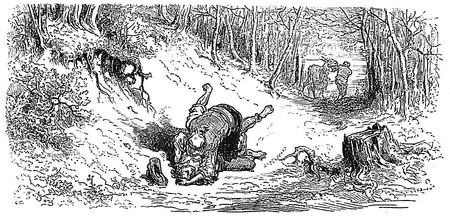

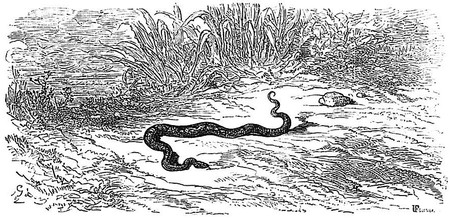

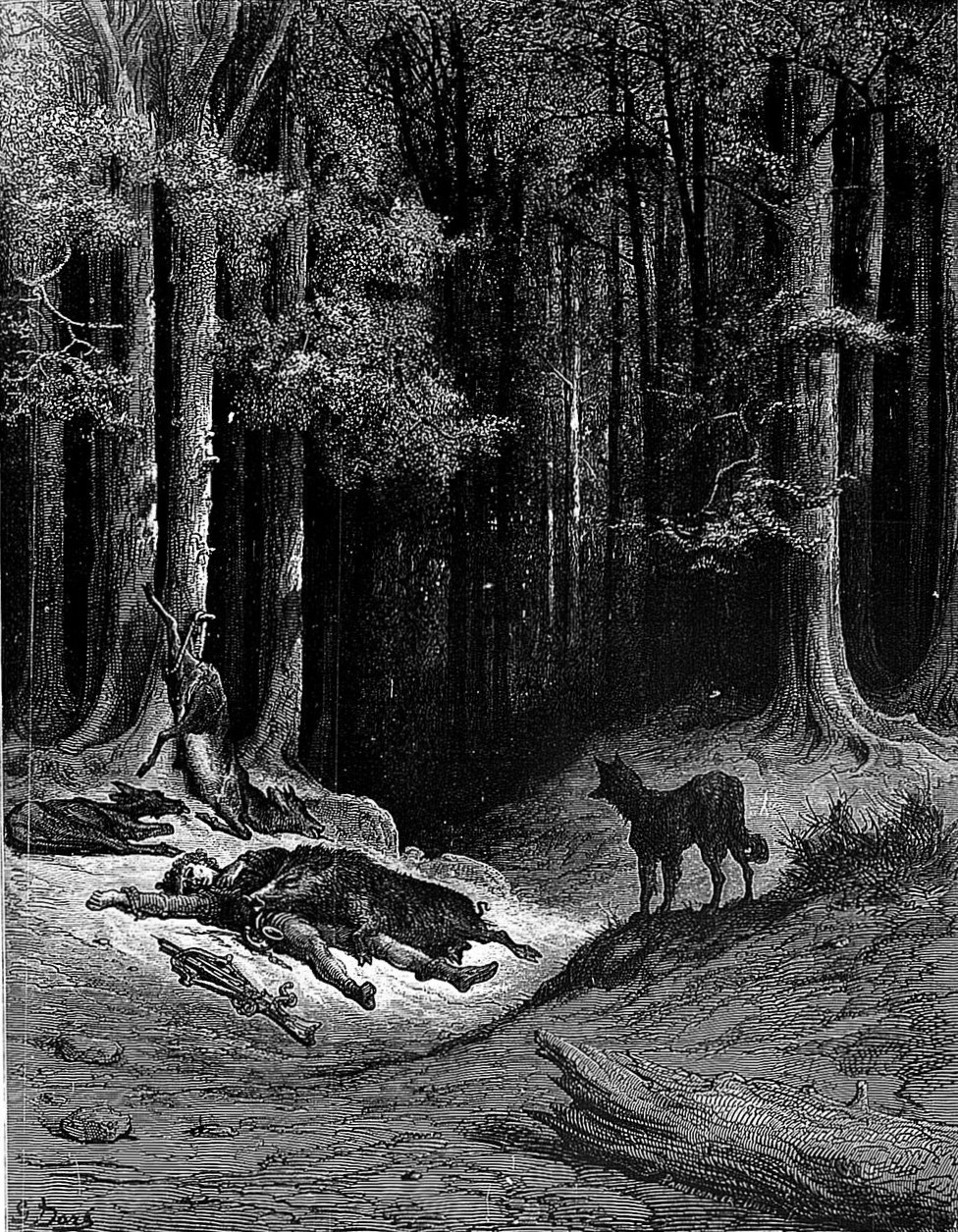

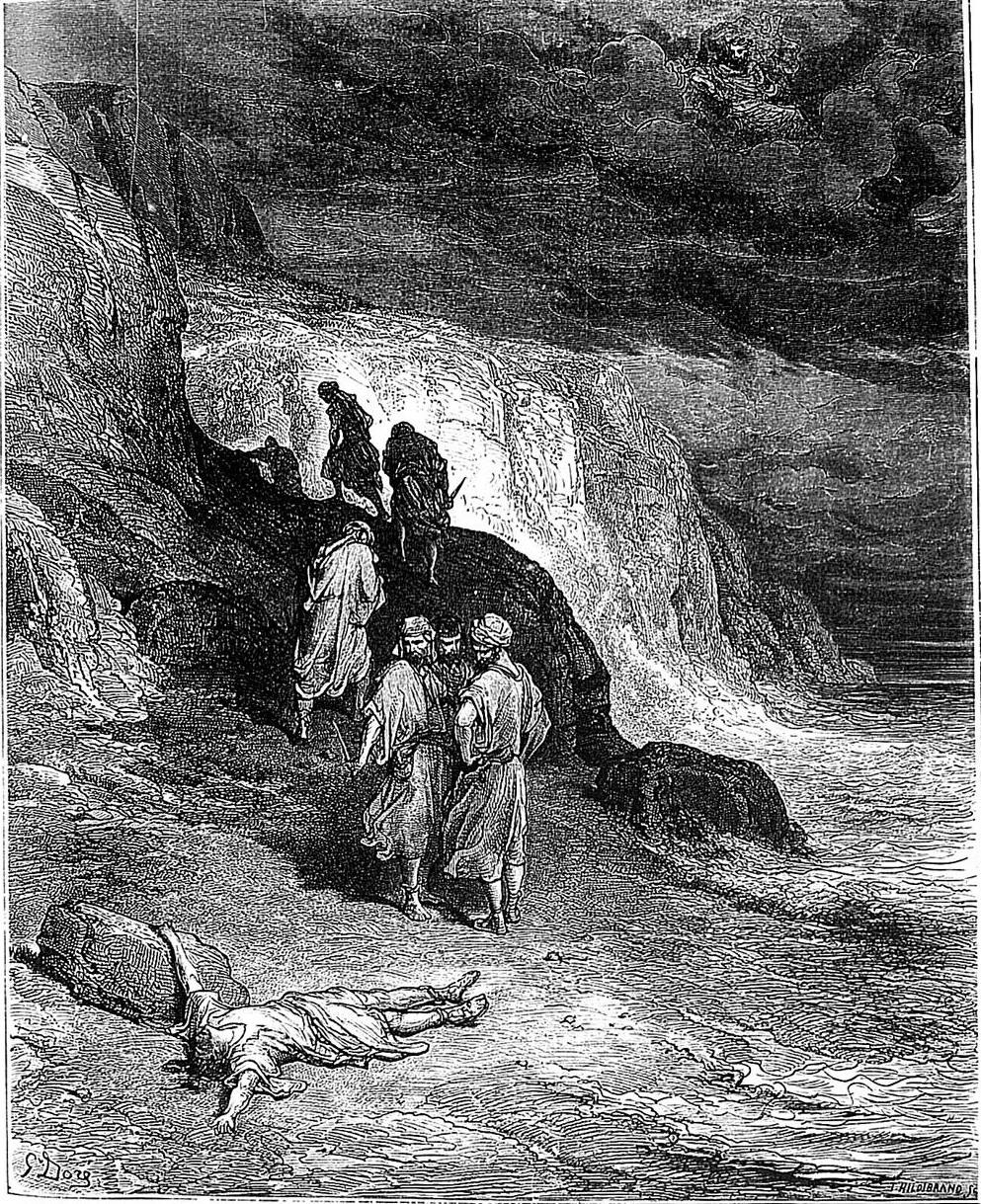

The Countryman and the Serpent 341

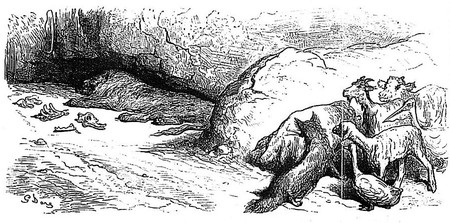

The Sick Lion and the Fox 349

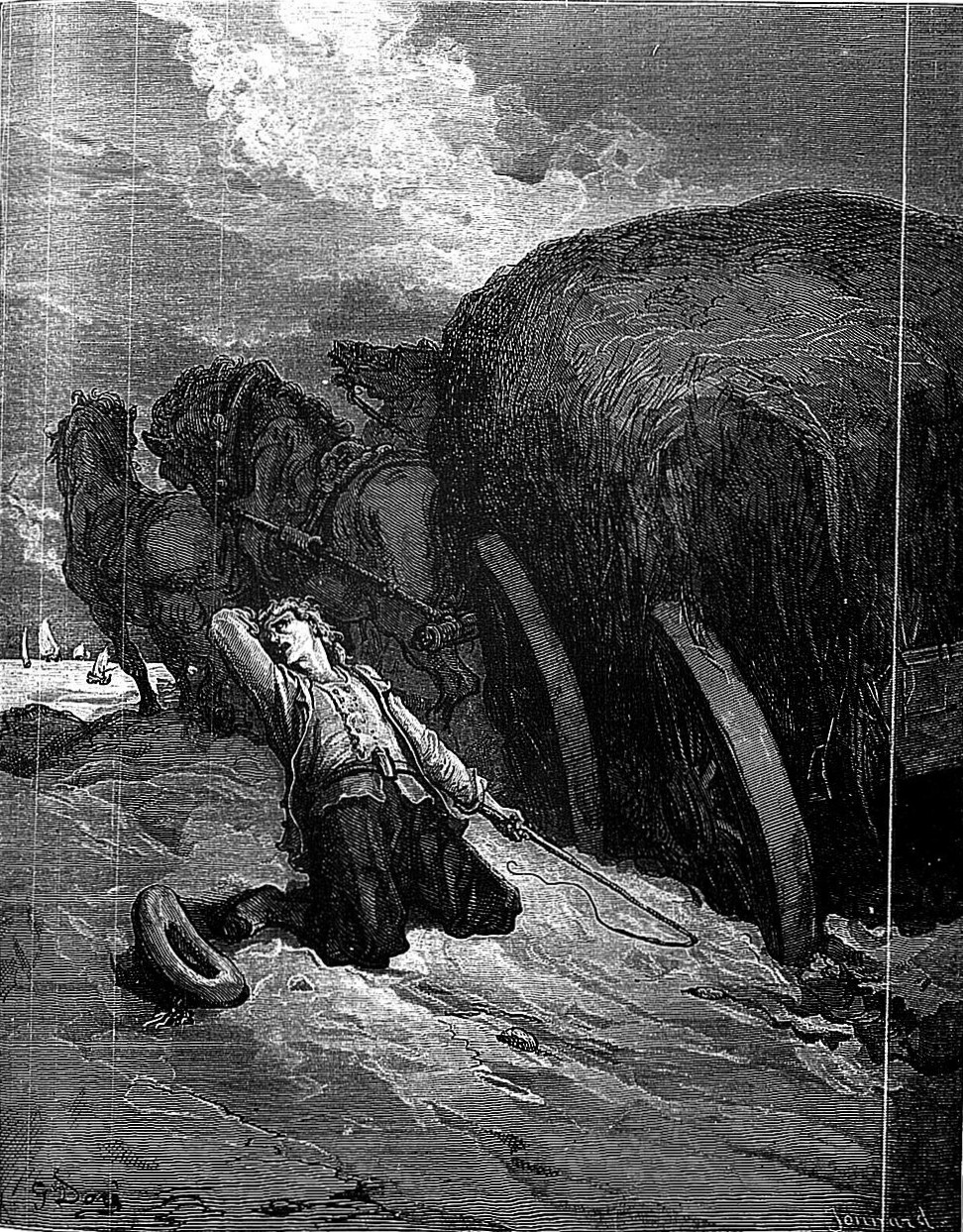

The Carter Stuck in the Mud 357

The Young Widow 369

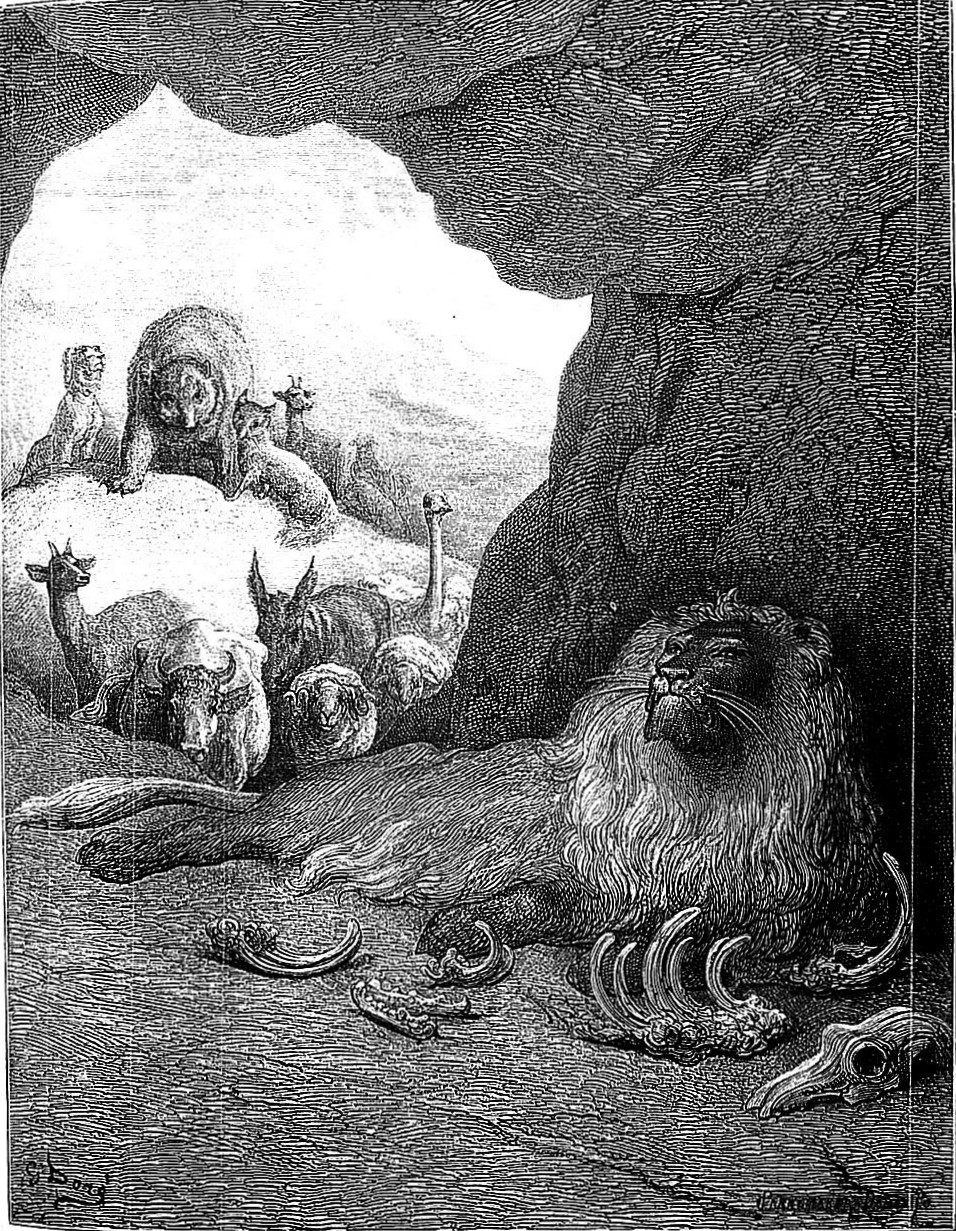

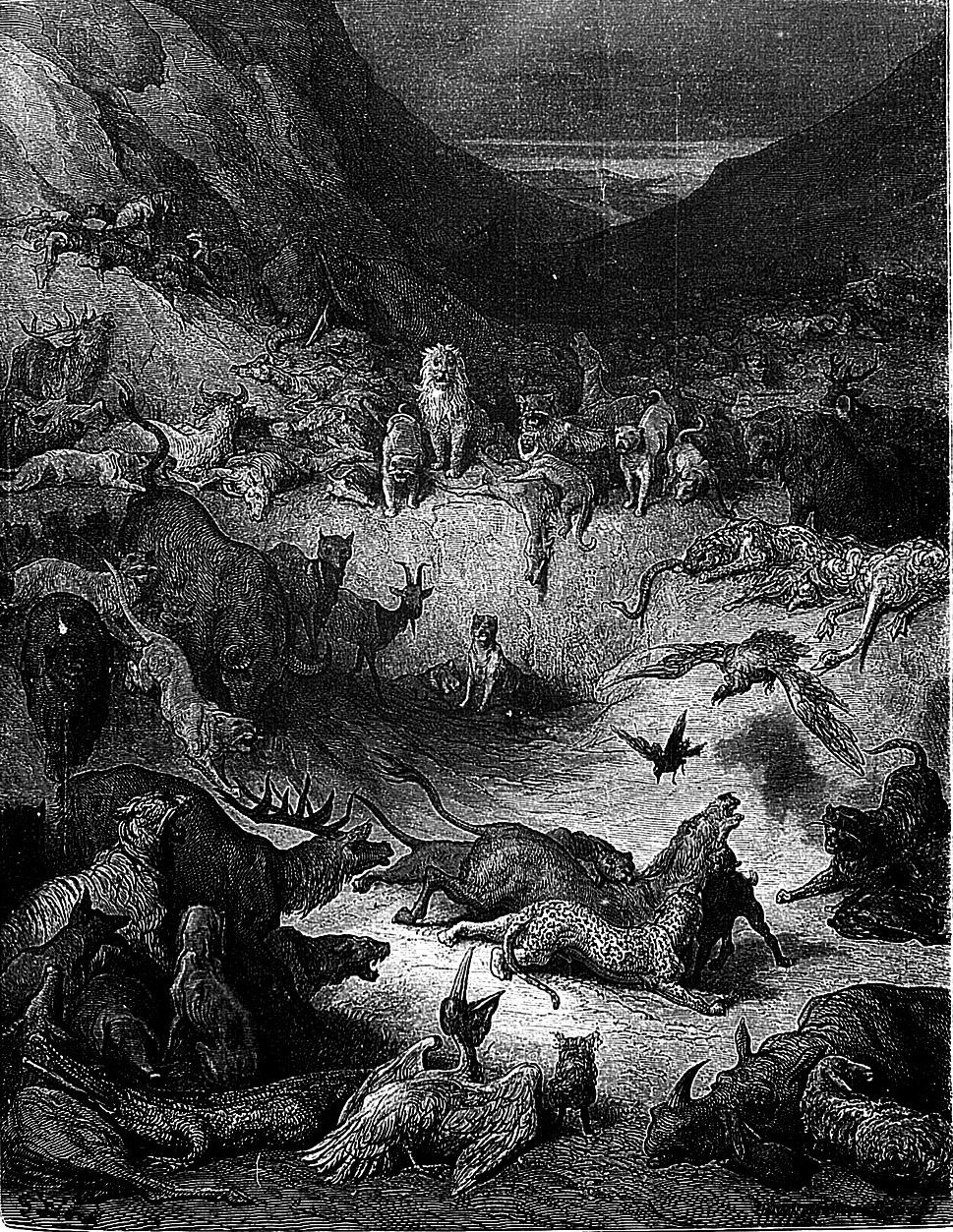

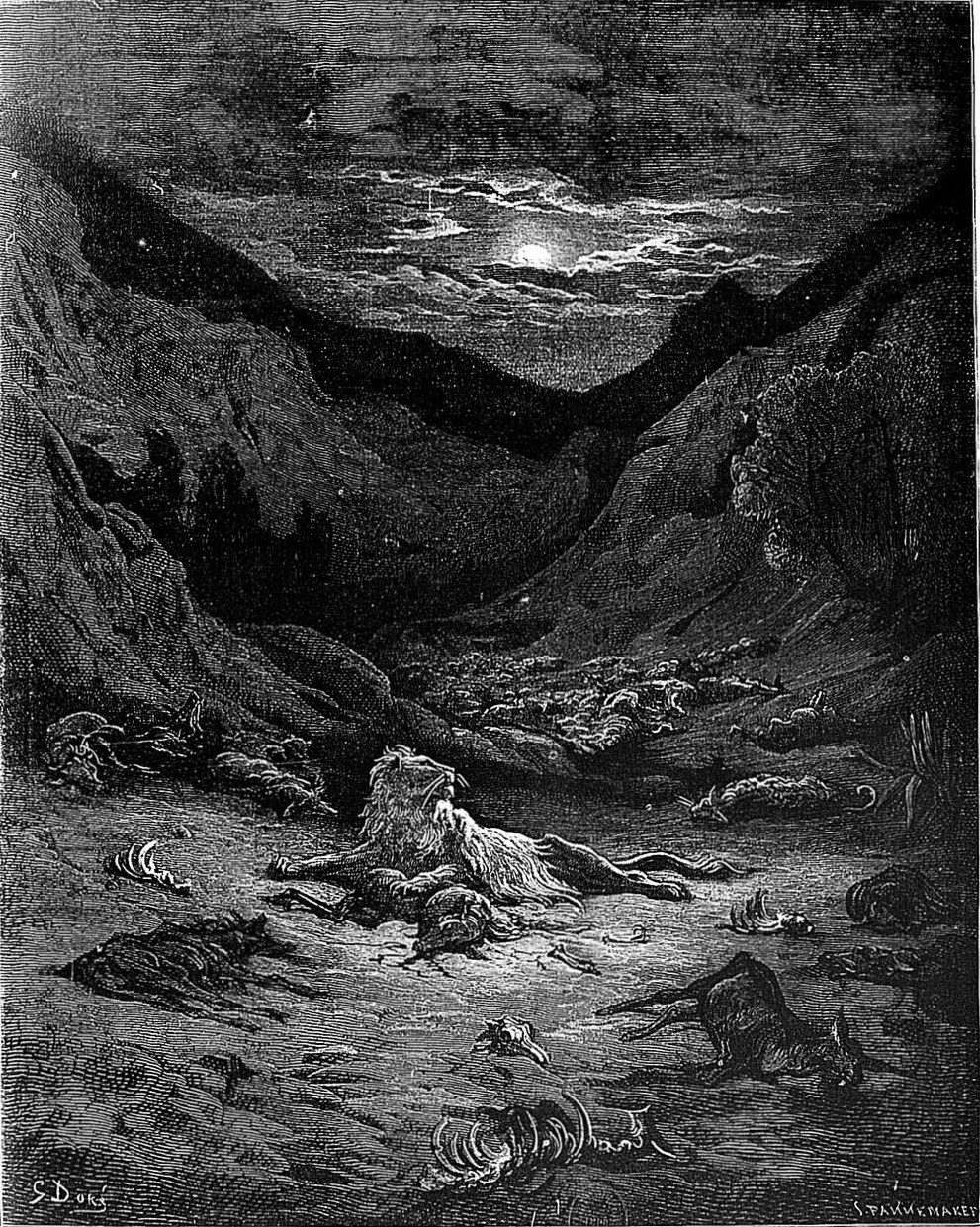

The Animals Sick of the Plague 377

The Maiden 389

The Vultures and the Pigeons 397

The Milkmaid and the Milk-Pail 405

The Two Fowls 417

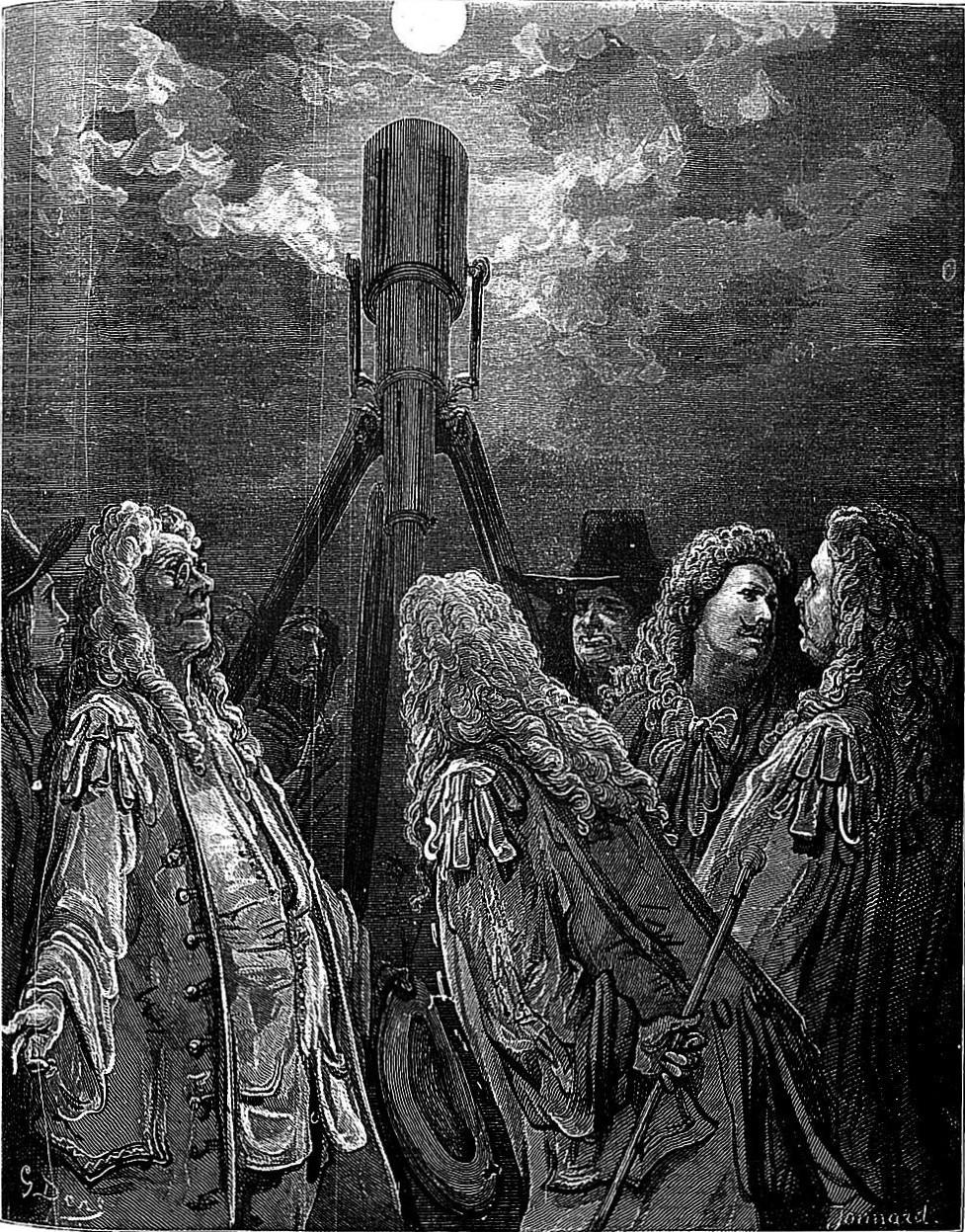

An Animal in the Moon 425

An Animal in the Moon (2) 429

The Fortune-Teller (illustration missing) 432

The Cobbler and the Banker 437

The Lion, the Wolf, and the Fox 445

The Dog and His Master's Dinner 453

The Bear and the Amateur of Gardening 465

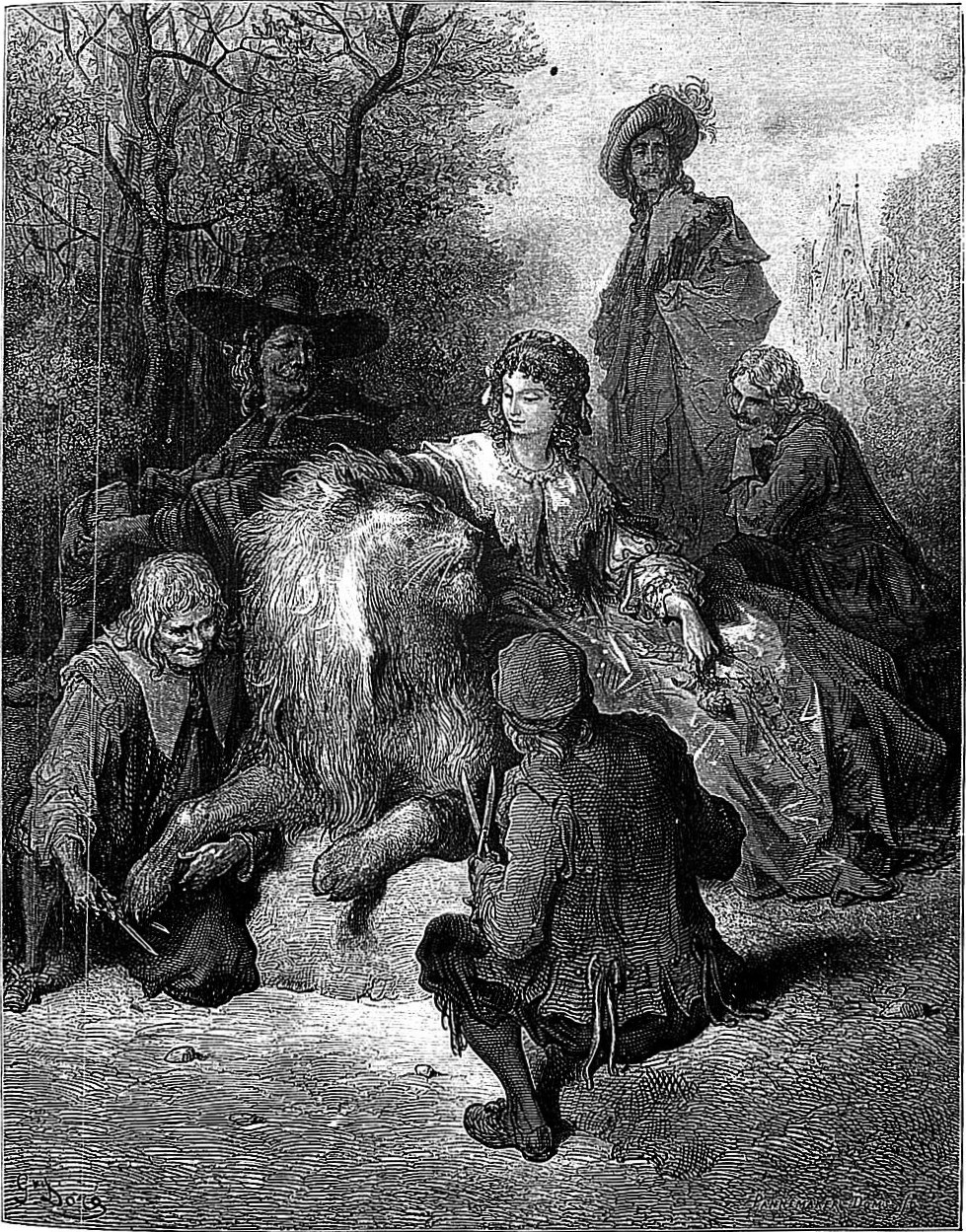

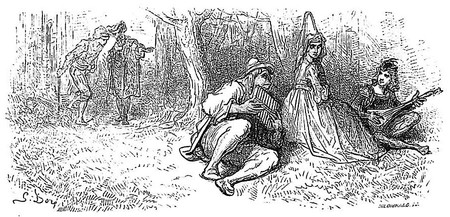

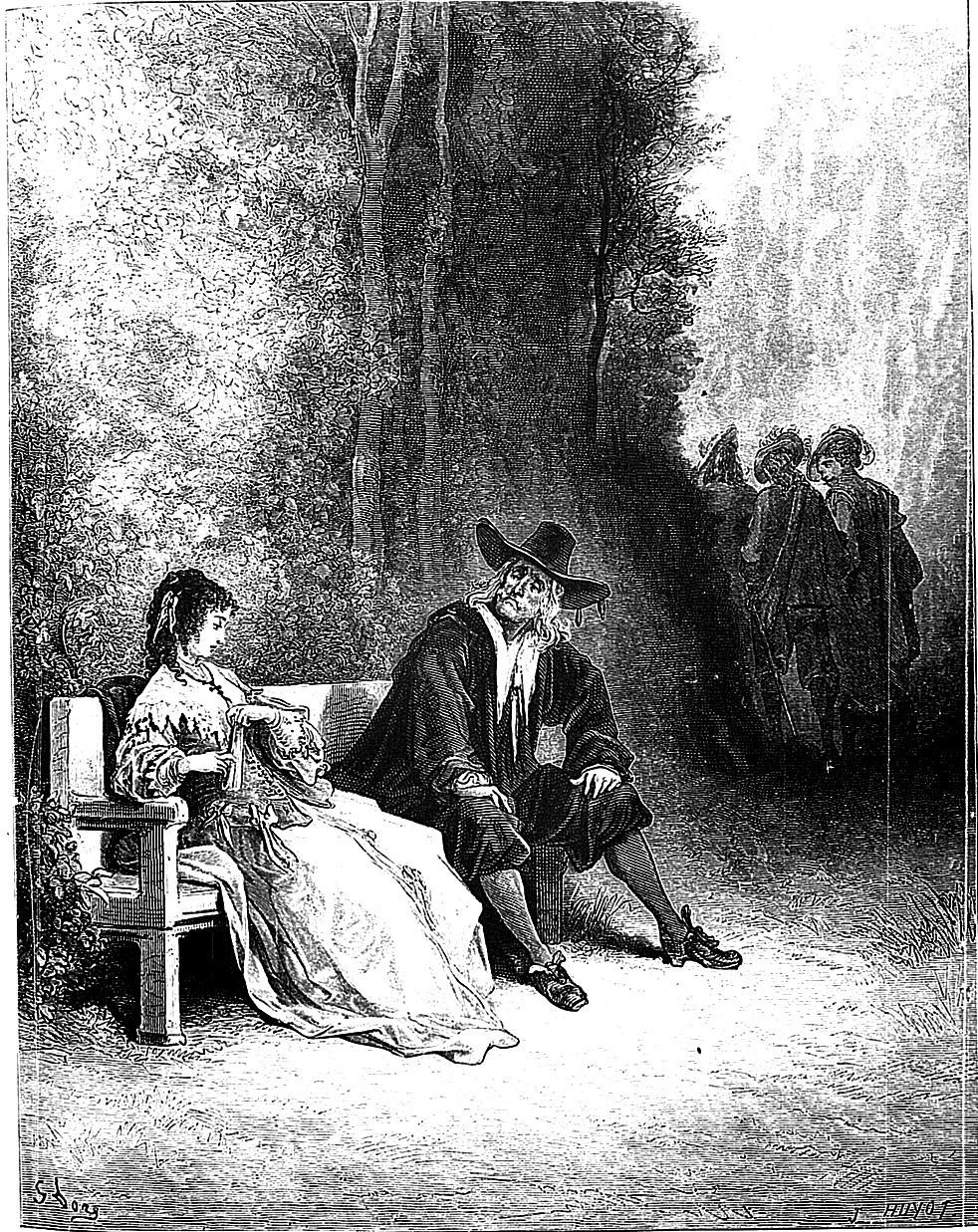

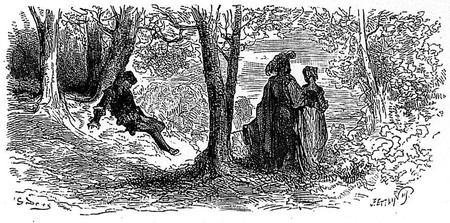

Tircis and Amaranth 473

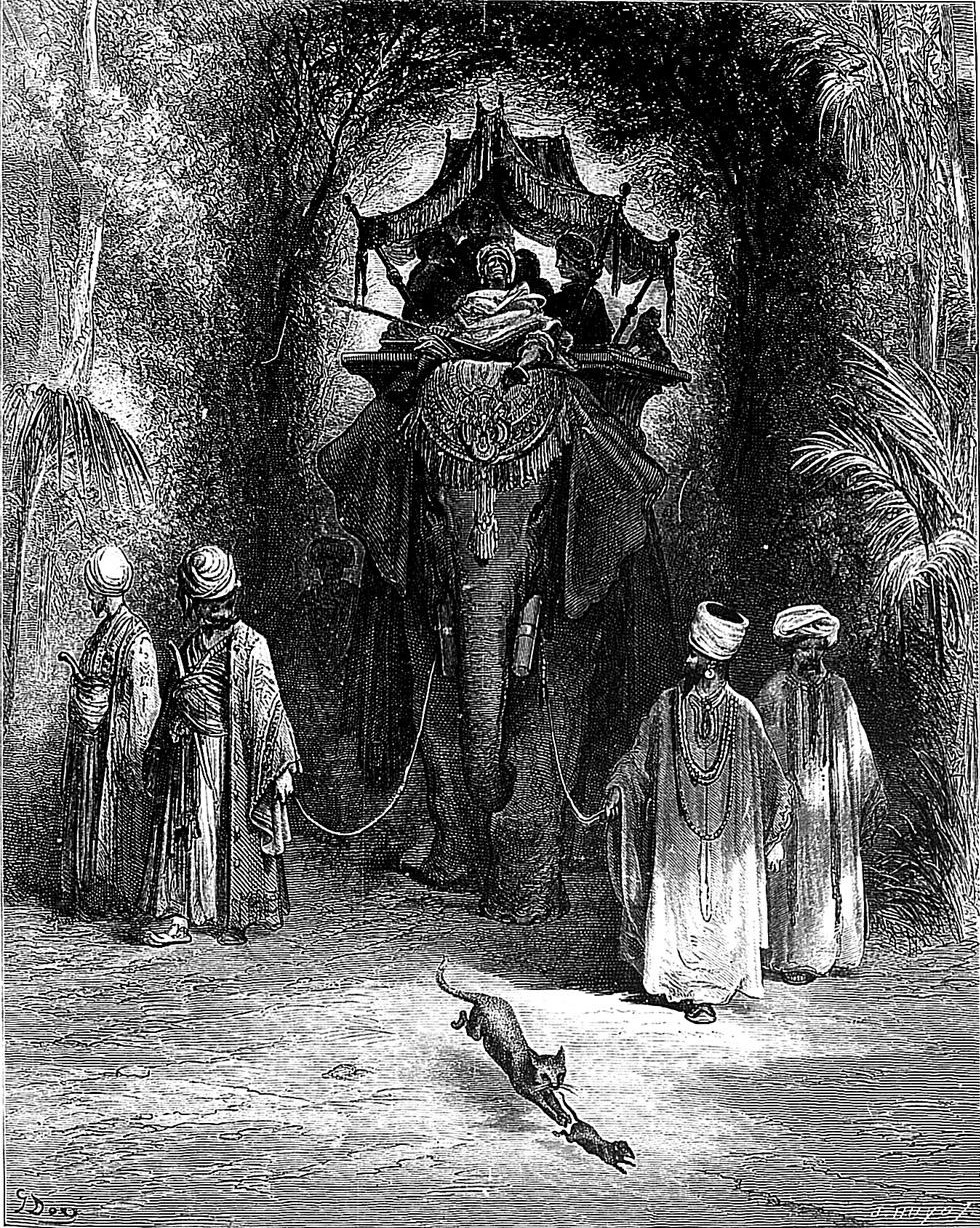

The Rat and the Elephant 489

The Bashaw and the Merchant 497

The Torrent and the River 509

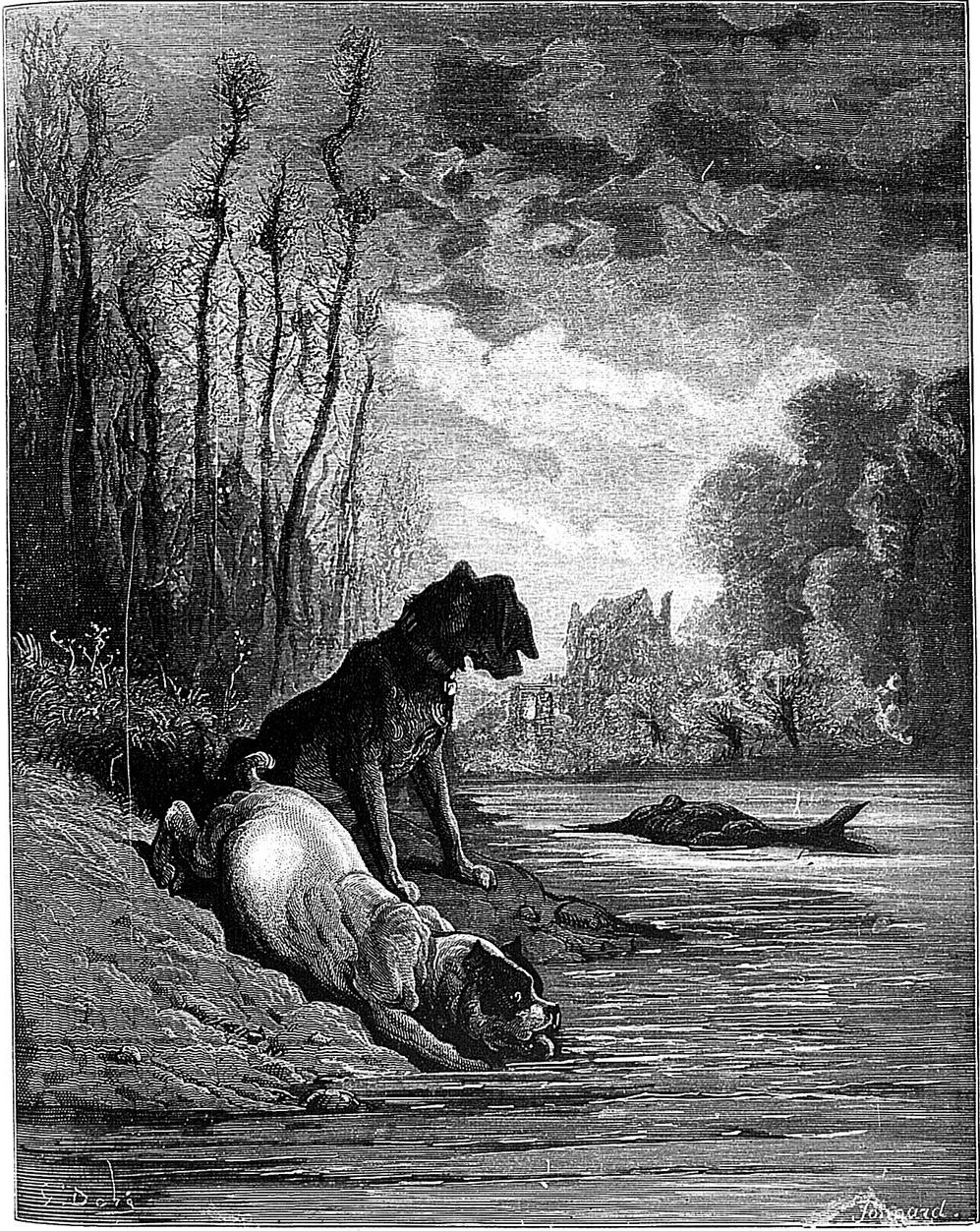

The Two Dogs and the Dead Ass 517

The Wolf and the Hunter 525

The Two Pigeons 537

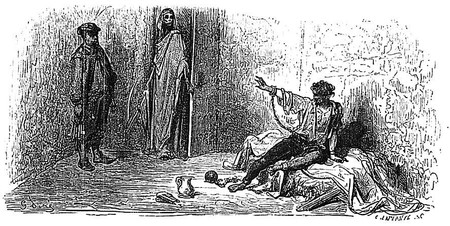

The Madman Who Sold Wisdom 545

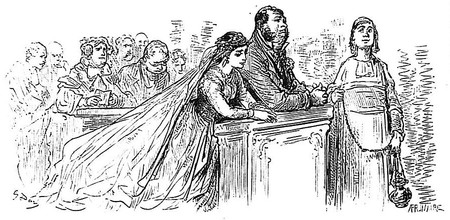

The Oyster and Its Claimants 557

Jupiter and the Traveller 569

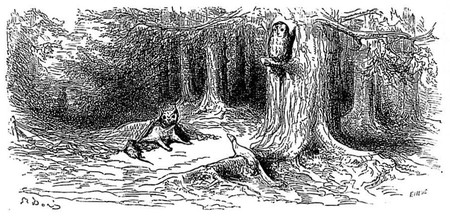

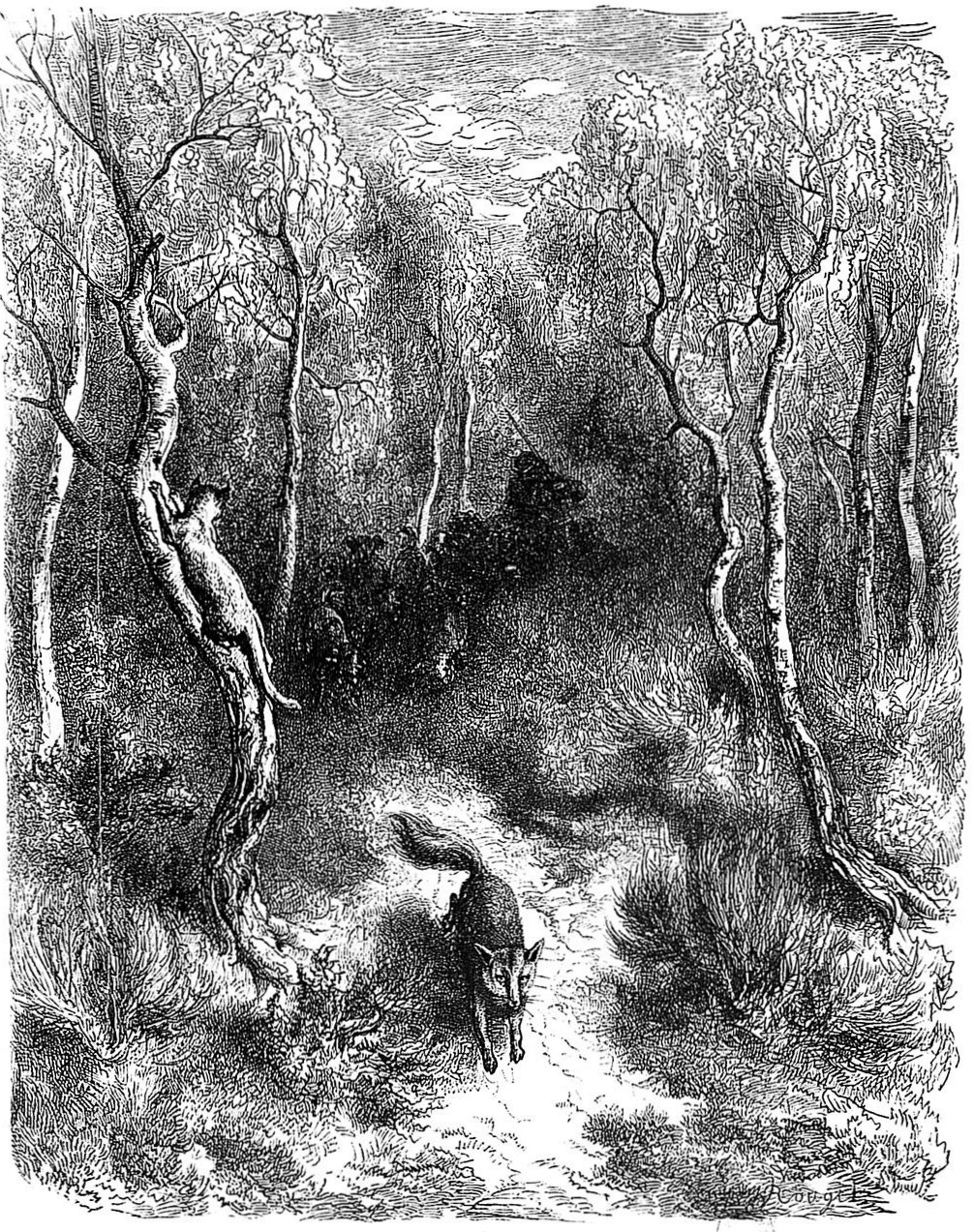

The Cat and the Fox 581

[Pg xi]

The Monkey and the Cat 593

The Two Rats, the Fox, and the Egg 609

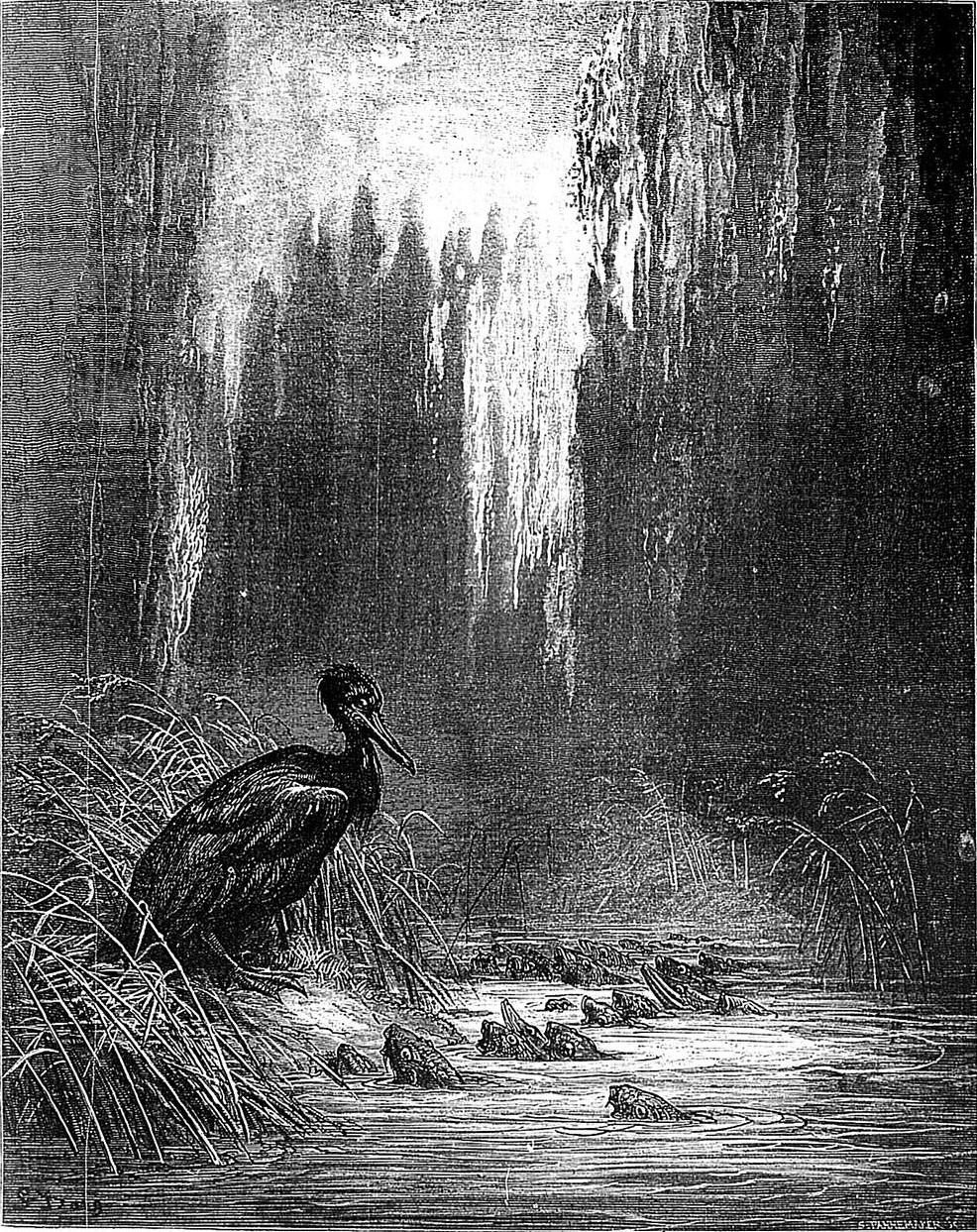

The Cormorant and the Fishes 621

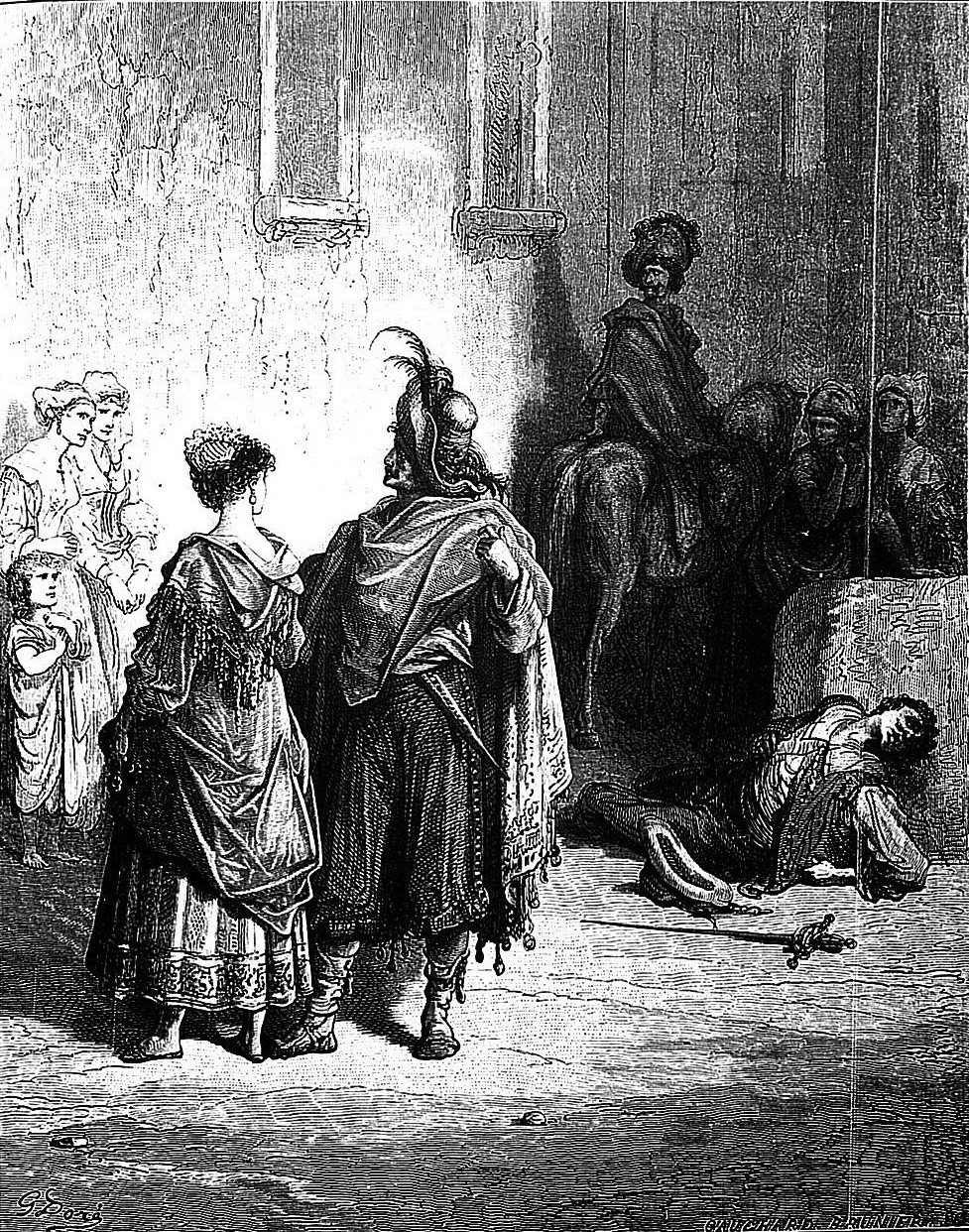

The Shepherd and the King 629

The Fish and the Shepherd Who Played on

the Clarionet 641

The Two Adventurers and the Talisman 653

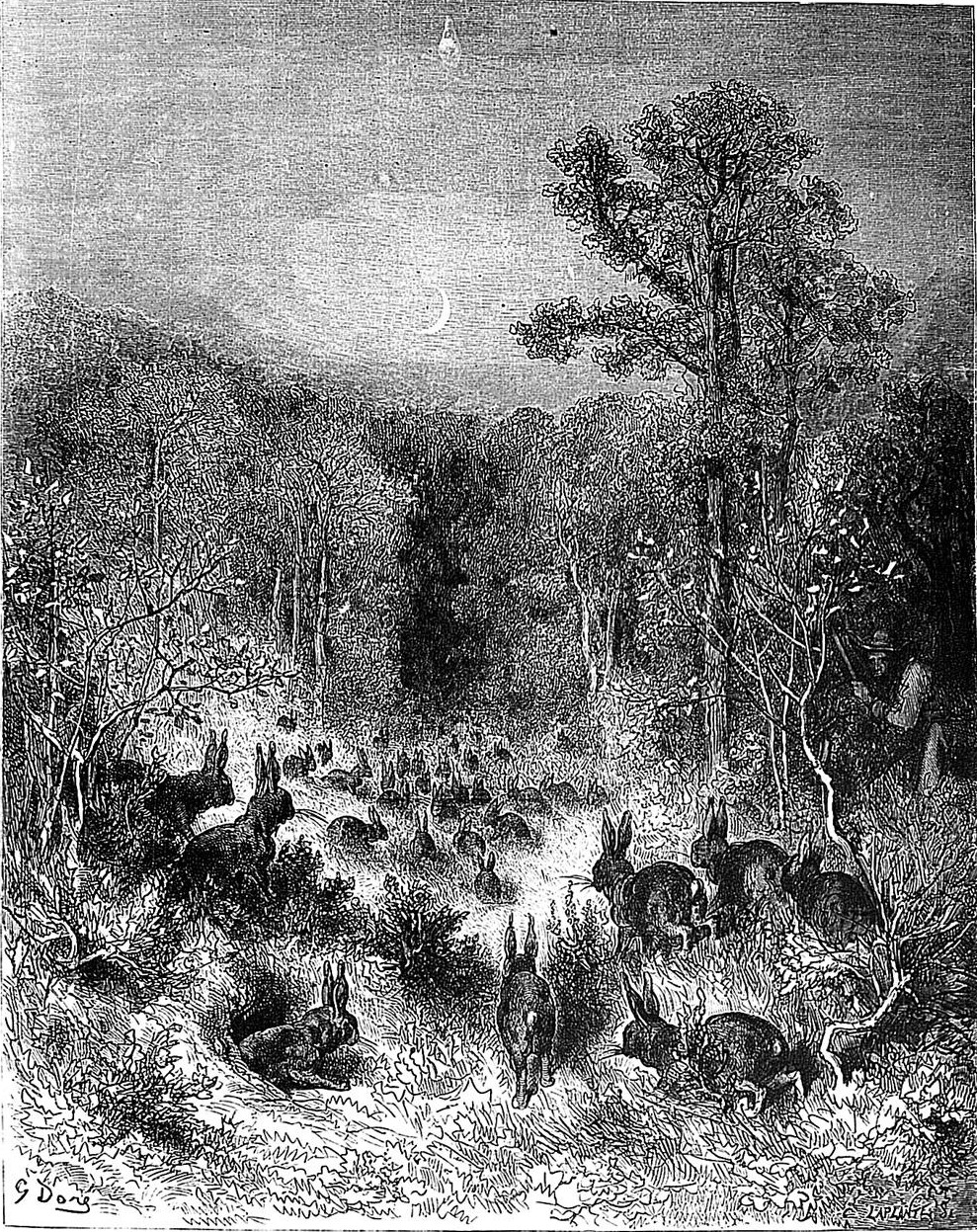

The Rabbits 665

The Lion 677

The Peasant of the Danube 689

The Old Man and the Three Young Men 701

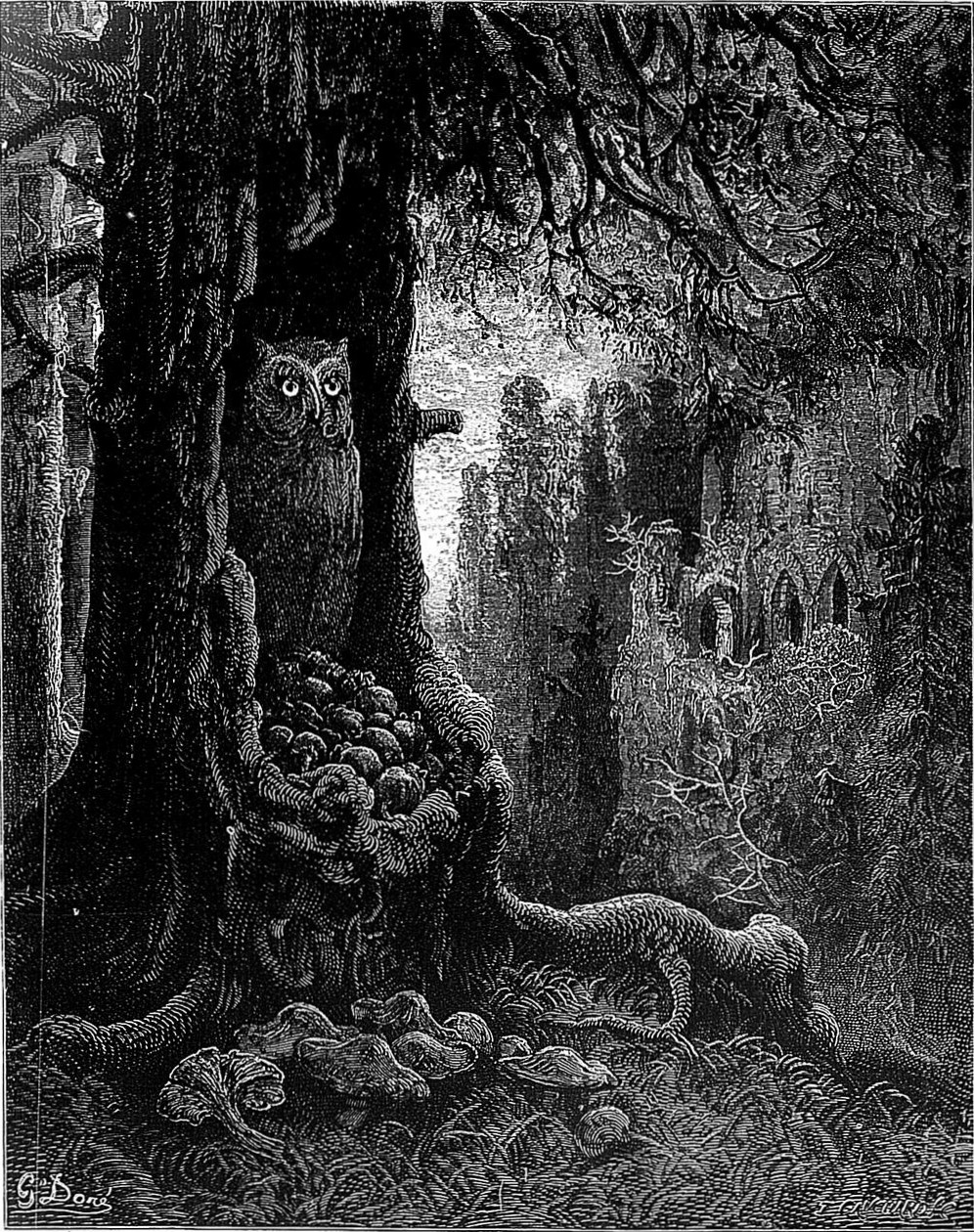

The Owl and the Mice 709

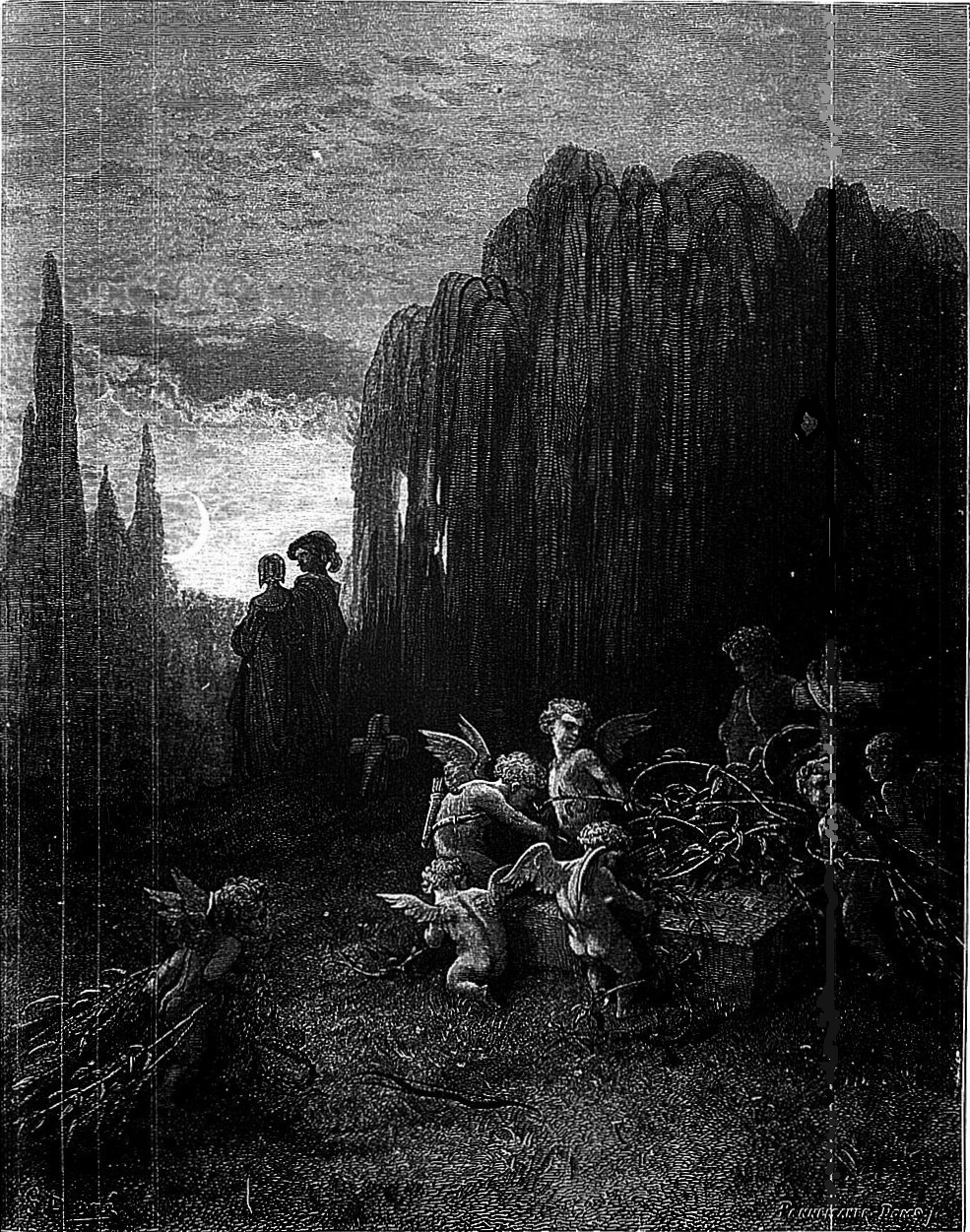

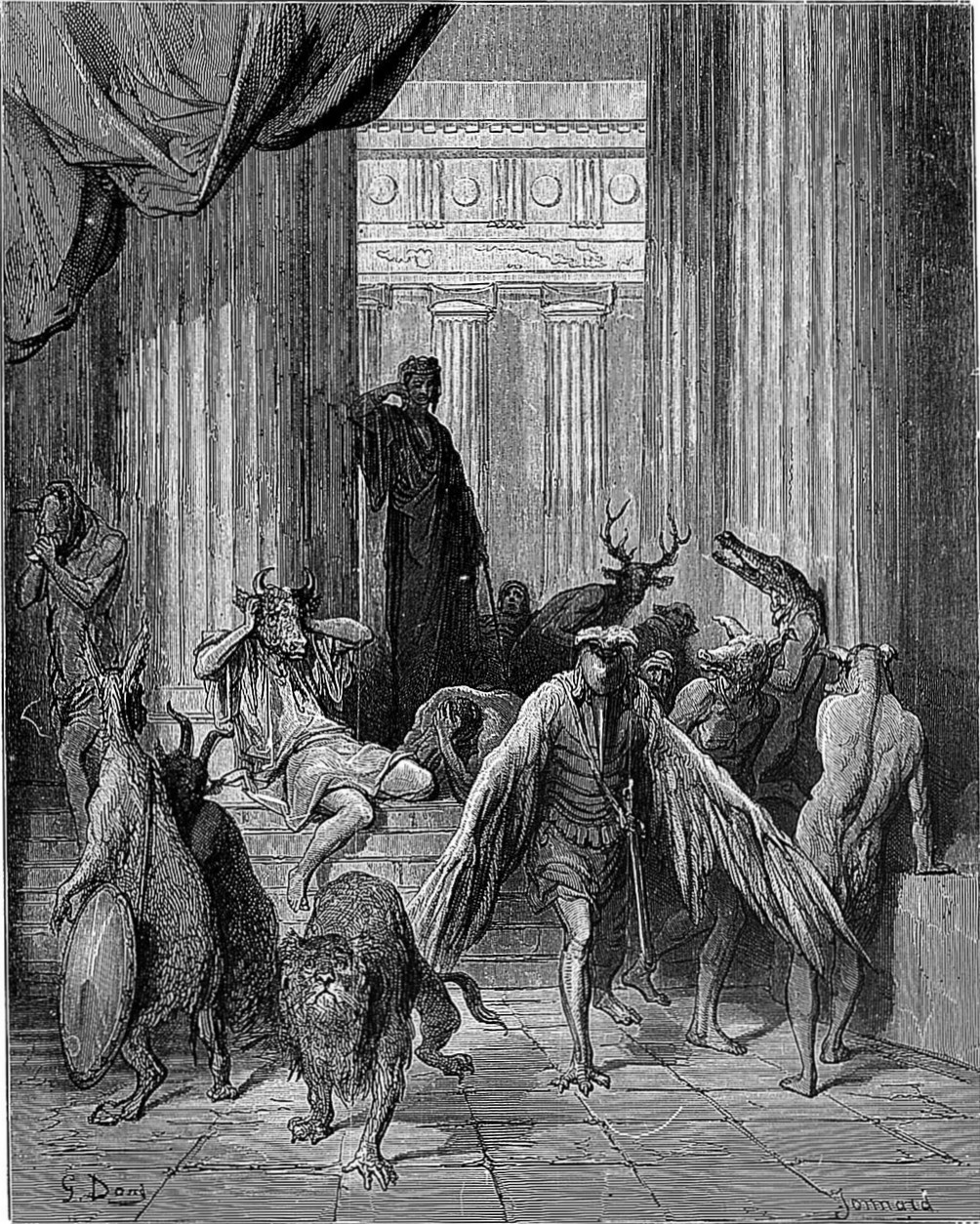

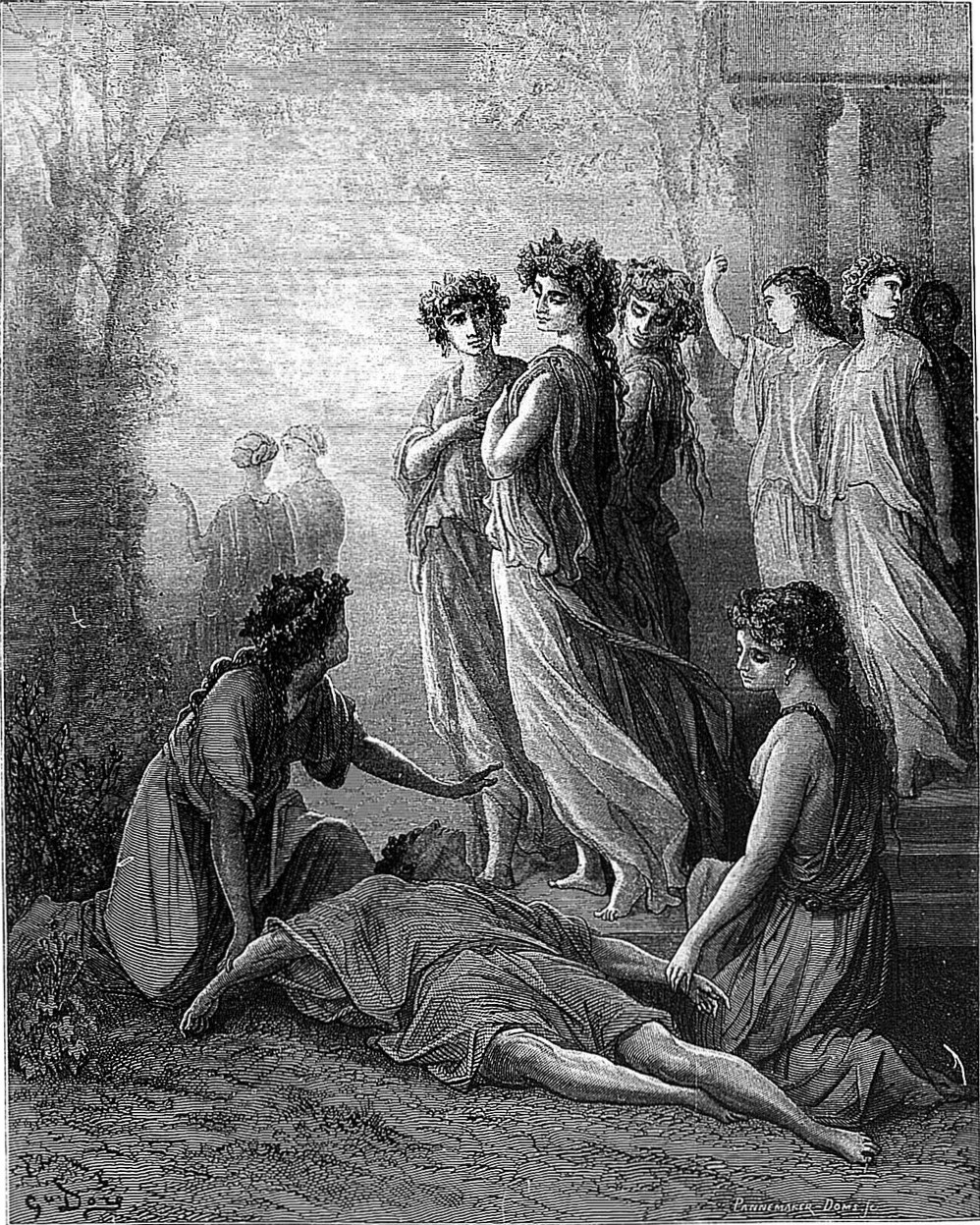

The Companions of Ulysses 717

The Two Goats 729

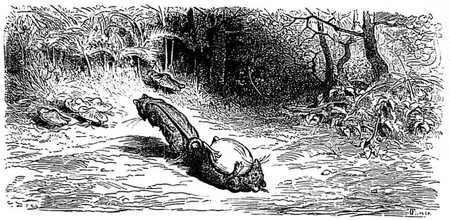

The Sick Stag 741

The Eagle and the Magpie 757

Love and Folly 765

The Forest and the Woodman 777

The Fox and the Turkeys 789

The English Fox 801

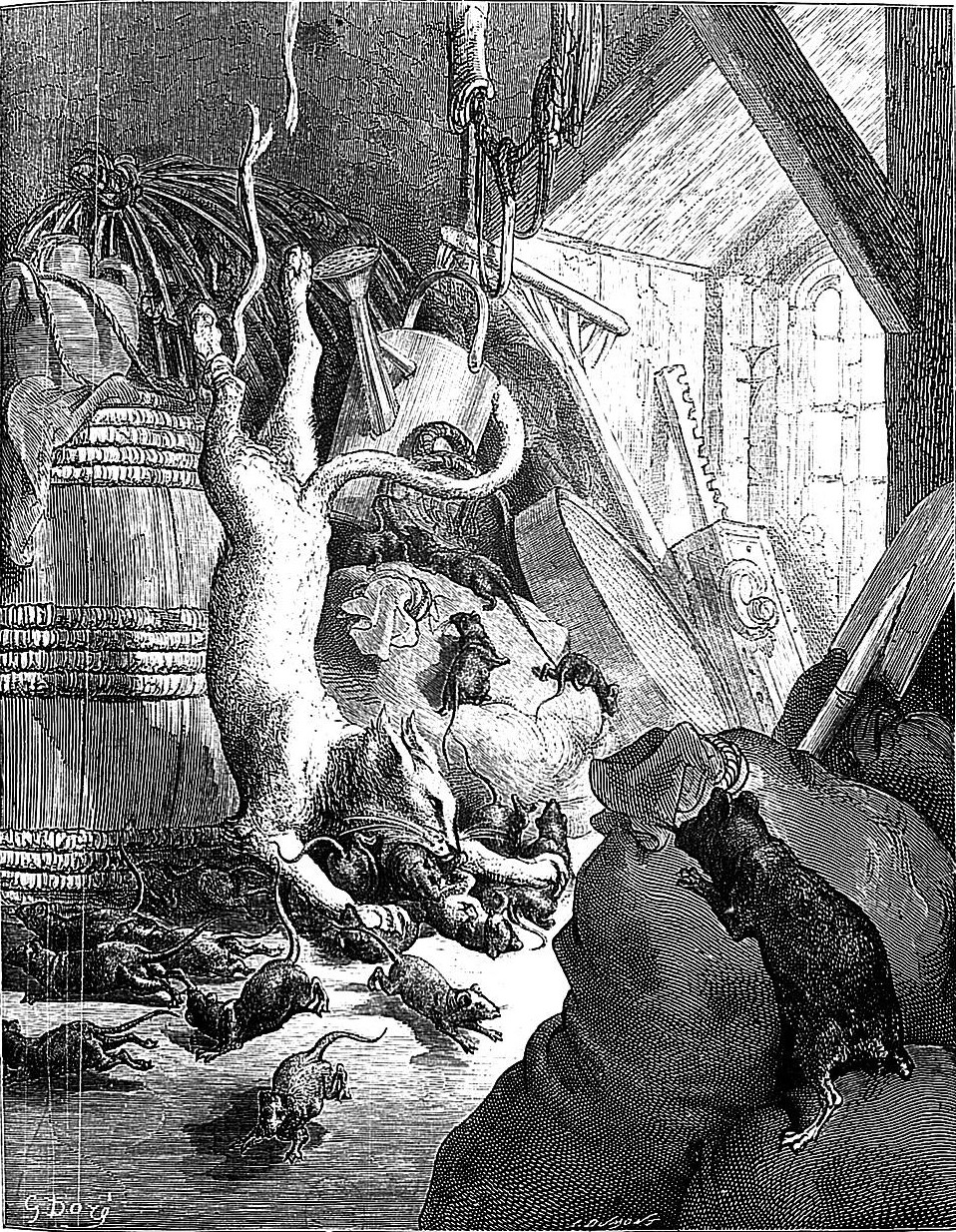

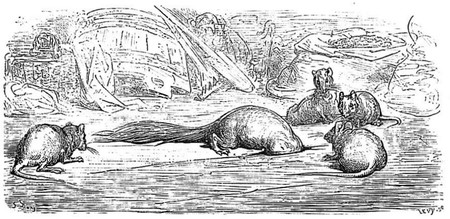

The League of the Rats 813

Daphnis and Alcimadura 821

The Arbitrator, Almoner, and Hermit 837

[Pg xiii]

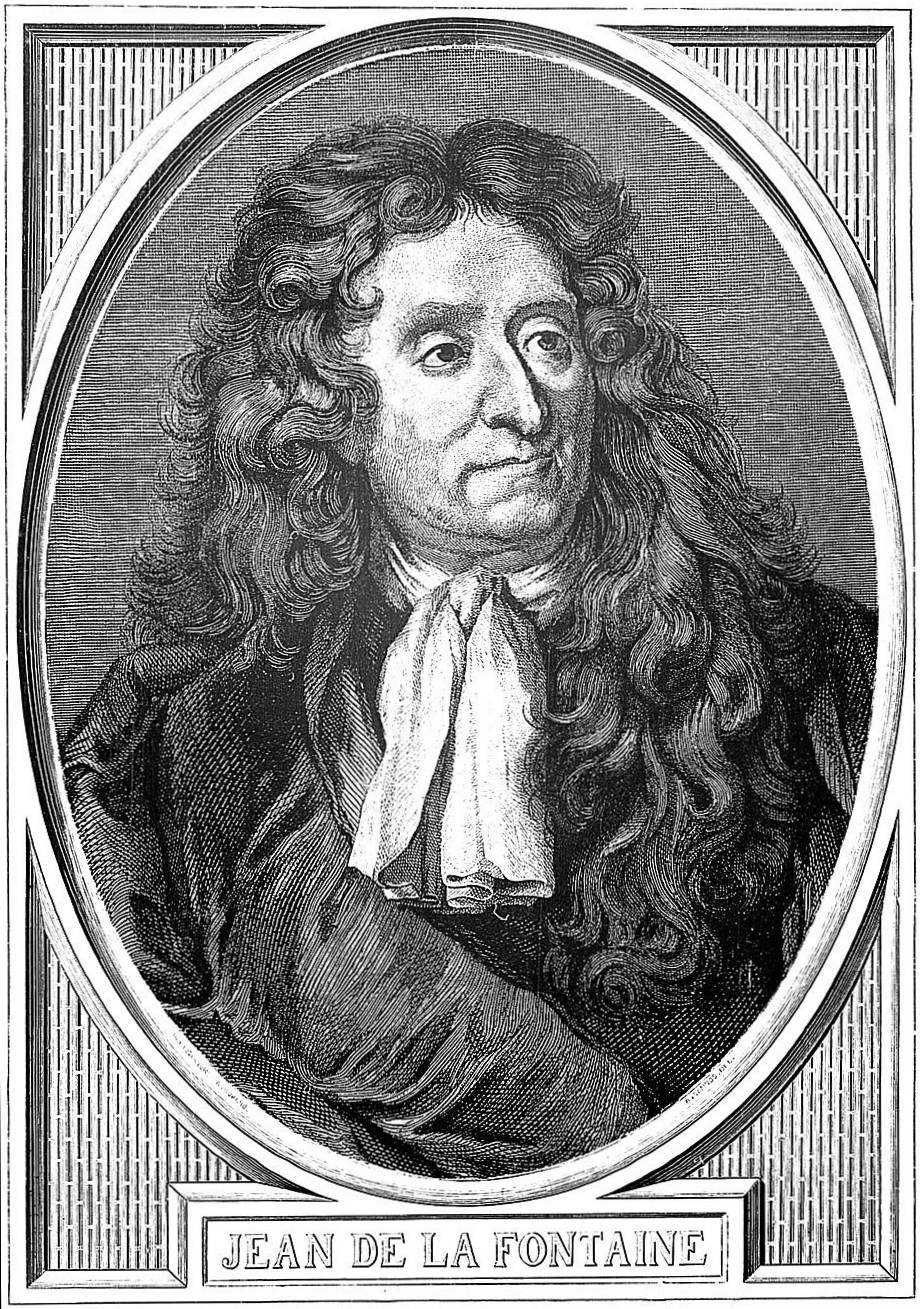

There are some writers the facts about whom can never be entirely told, because they are inexhaustible, and speaking of whom we do not fear to be blamed for repetition, because, though well known, they furnish topics which never weary. La Fontaine is one of this class. No poet has been praised oftener, or by more able critics, and of no poet has the biography been so frequently written, and with such affectionate minuteness. Nevertheless, it is certain that there will yet arise fresh critics and new biographers, who will be as regardless as ourselves of the fact that the subject has been so frequently enlarged upon. And why, indeed, should we refuse to ourselves, or forbid to others, the pleasure of speaking of an old friend of our childhood, whose memory is always fresh and always dear?

This truly worthy man was born in Château-Thierry, a little town of Champagne, where his father, Charles de la Fontaine, was a supervisor of woods and forests. His mother, Françoise Piloux, was[Pg xiv] the daughter of a mayor of Coulommiers. An amiable but careless child, he was lazy in his studies, and certainly did not display, by the direction of his earlier inclinations, the germs of his future genius. At twenty years of age, after the perusal of some religious works, he formed the idea that his vocation was the Church, and entered the seminary of Saint Magloire, where, however, he remained only one year. His example was followed by his brother Claude, with this difference, that the latter persevered to the end. On quitting the seminary, La Fontaine, in the paternal mansion, led that life of idleness and pleasure which so frequently, especially in the provinces, enervates young men of family. To bring him back to a more orderly course of life, his father procured him a wife, and gave him the reversion of his office. He was then twenty-six years of age, and the demon of poetry had not yet taken possession of him. La Fontaine never hurried himself about anything.

The accidental recitation in his presence of an ode by Malherbe aroused in his soul, which had hitherto been devoted to pleasure and idleness, a taste for poetry. He read the whole of Malherbe's writings with enthusiasm, and endeavoured to imitate him. Malherbe alone would have spoiled La Fontaine, had not Pintrel and Maucroix, two of his friends, led him to the study of the true models. La Fontaine himself has left a confession of these first flights of his muse. Plato and Plutarch, amongst the ancients, were his favourite authors; but he could read them only by the aid of translations, as he had never studied Greek. Horace, Virgil, and Terence, whose writings he could approach in the original, also charmed him. Of modern authors his favourites were Rabelais, Marot, De Periers, Mathurin, Régnier, and D'Urfé, whose "Astræa" was his especial delight.

Marriage had not by any means fixed his inconstant tastes. Marie Héricart, whom he had been induced to marry in 1647, was endowed with beauty and intellect, but was unsupplied with those solid qualities, love of order, industry, and that firmness of character which might have exercised a wholesome discipline over her husband. Whilst she was reading romances, La Fontaine sought amusement away from home, or brooded either over his own poems or those of his favourite authors. The natural consequence was, that the affairs of the young people soon fell into disorder; in addition[Pg xv] to this, when La Fontaine's father died, he left our poet an inheritance encumbered with mortgages, which had been the only means of paying debts, and preserving the family estate intact; these became fresh sources of embarrassment to our poet, who being, as may well be supposed, anything but a man of business, incapable of self-denial, and unassisted by his wife, soon, as he himself gaily expressed it, devoured both capital and income, and in a few years found himself without either.

La Fontaine seems to have confined his duties, as supervisor of woods and waters, to simply taking long rambles under the venerable trees of the forests submitted to his care, or to enjoying prolonged slumbers on the verdant banks of murmuring brooks. And that this was the case we may reasonably suppose, since at sixty years of age he declared that he did not know what foresters meant by round timber, ornamental timber, or bois de touche.

His soul was wrapped up in poetry. His first poems were what might be called album verses, and could scarcely have been understood beyond Château-Thierry. These verses, however, obtained so favourable a reception, that at length he ventured to attempt a comedy. But, as the faculty of construction had been denied him, he only adapted one of Terence's plays, changing the names of the characters, and taking certain liberties with the situations. The piece which he had selected, the "Eunuchus," was very unsuited to the boards of the French stage, and he never attempted to get it produced; but he published it, and it was by means of this mediocre, although neatly versified work, that his name first became known to the public, when he had already entered his thirty-third year.

It was about this period that one of his relations, J. Jannart, a counsellor of the king, presented the poet to Fouquet, for whom Jannart acted as deputy in the Parliament of Paris. The Surintendant, partial to men of letters, gave La Fontaine a cordial reception, and bestowed upon him a liberal pension. La Fontaine became, not a mere accessory, but one of the most valued elements of the royal luxury of Fouquet's house, or, rather, court; and it was through his protégé, at a later period, that Fouquet received the only consolation that soothed his disgrace. La Fontaine, established as poet-in-ordinary to Fouquet, received a pension of a thousand livres, on condition that he furnished,[Pg xvi] once in every three months, a copy of laudatory verses. He was henceforth a guest at a perpetual round of fêtes; his eyes were dazzled, his heart was moved, and his mind at last awoke. The years which he passed in the midst of this voluptuous magnificence were years of enchantment, of which he has left traces in the "Songe de Vaux," the earliest indication of a talent which was to develop into genius. The first efforts of his muse at this period were laid at the shrine of gratitude, but grief more happily inspired him, for the "Elegy to the Nymphs of Vaux," the subject matter of which was the disgrace of the Surintendant, raised him to the front rank amongst the masters of his art. Up to this time La Fontaine had been only a pleasant, lively, and ingenious versifier; but on this occasion he proved himself a true poet, and the lines which we have just named are still regarded as amongst the choicest productions of the sort in the French language. "La Fontaine did not merely bewail, in the fall of Fouquet, the loss of his own hopes and pleasures, but the misfortunes of the one friend to whom he was gratefully attached, and of whose brilliant qualities he had the highest admiration. The emotion which he expressed was no fleeting one, for, some years afterwards, when passing by Amboise, the faithful friend desired to visit the apartment in which Fouquet had endured the first period of his imprisonment. He could not enter it, but paused on the threshold, weeping bitterly; and it was only at the approach of night that he could be induced to leave the spot."

Our poet's success amongst the crowd of brilliant men and distinguished women who formed Fouquet's court, could never be understood, if we gave full credence to those stories of odd eccentricities, simplicities, and blunders of which he has so frequently been made the hero. It cannot be denied that he was frequently a dreamer, absorbed in his own thoughts, and too apt to be credulous and absent in mind; but the greeting which was accorded to him, and the eagerness with which his acquaintance was courted in such a place, are sufficient evidences that he could be a charming companion when he pleased. He could be abstracted enough when surrounded by uncongenial spirits; he opened his heart only to those who pleased him: but on his friends he lavishly bestowed his joyous but refined wit, and his delightful bonhomie. The inborn carelessness of his nature rendered him averse to everything[Pg xvii] like effort; he was dumb to those who knew not how to touch the keynote of his soul; to such he was present, indeed, in the body, but his soul was cold and inharmonious. It may even be added, that reverie with him was a species of politeness by which he was wont to conceal his weariness. On such occasions he doubtless fled to the companionship of his fabulous beasts, although he refrained from saying so. Abstraction was to La Fontaine a means of becoming independent, and it is not, therefore, very surprising that he should have allowed people to attribute to him, in an exaggerated degree, a defect which he found so useful.

Fouquet's disgrace threw La Fontaine once more into that family life for the earnest and monotonous duties of which he had now grown more than ever unfitted. A son had been born to him, and this might have been supposed to attach him to his home; but the truth is, that children, whom he has for so many generations amused, were regarded by La Fontaine as his natural enemies, and he never let slip any occasion of expressing this opinion. "The little people," as he called them, were always obnoxious to him. It must be admitted that they are importunate, noisy, ever clamorous for small attentions, and they appear tyrannical to the last degree, in the eyes, at least, of those who have no warm affection for them. And it must also be admitted that La Fontaine was frequently their rival; for he always desired to be, and was, the spoilt child of the house, the child whose caprices were ever humoured, whose tastes were ever consulted. His life was, indeed, one long period of childhood. He arrived at manhood, became grey, and grew old, without ceasing to be a child; and to understand him rightly we must remember this fact. It is the key to, and some excuse for, that neglect of all serious duties which we should have to severely blame in him, if we applied to his case the rules of rigorous morality.

Constituted as he was, La Fontaine would naturally seize every opportunity of quitting his family and that Château-Thierry which he now regarded as a species of tomb. To distract himself from his grief, whilst apparently clinging to it more closely, he followed to Limoges his relation Jannart, who had been exiled by lettre de cachet with Madame Fouquet, to whom he served as secretary and steward. Our poet has written a narrative of this journey in a series of letters to his wife, interspersed with pretty verses, and abounding in vivacity. His stay[Pg xviii] at Limoges was short, and we soon after find him dividing his time between Paris and Château-Thierry, sometimes alone, and sometimes with Madame de La Fontaine, who at first frequently accompanied him in his excursions. The expense of these frequent journeys was naturally calculated to add to the disorder of his affairs; but he troubled himself little on this score, and it was some consolation that his own property alone was melting away, and that his wife would by-and-by be able to live by herself on property devoted to her own use. Let us also remark, in passing, that he did not altogether neglect that son of his who, at a later period, he describes as a charming boy, in that short and singular interview which has been so frequently discussed, and to whose education he attended until he was relieved of that duty by the generosity of the Procureur-General, De Harlay.

To this period must be referred his intimacy with Racine, also a "Champenois," and a brother poet—an intimacy which was due to the good offices of Molière, whom La Fontaine had known, and, consequently admired and loved, when residing with Fouquet. His acquaintance with Racine led again to that with Boileau and Molière Chapelle, that incurable promoter of orgies, that wine-bibbing Anacreon, who was always at war with our four poets, especially towards the conclusion of their suppers. Boileau, the Severe, endeavoured sometimes to curb his joyous comrades, but with scant success, and it is on record that on a certain occasion Chapelle got drunk during the course of an impromptu sermon of Boileau's on the virtues of temperance. Our good friends led a joyous life, which, however, was nearly having a tragic termination, since once, after a dinner at Auteuil, over deep potations of wine, they were led to become philosophic in so melancholy a fashion, that they resolved to drown their several griefs in the Seine, and would have done so, had not Molière happily remarked that it would be more heroic to perform the deed on the morrow. This joyous fraternity soon broke up. Molière was driven away by an ill-judged action on the part of Racine. The royal favour induced Boileau and Racine to become more circumspect; Chapelle gave himself up to inordinate debauchery; and La Fontaine, whilst retaining his friendships, went to dream and amuse himself elsewhere.

Whilst this intimacy lasted, La Fontaine frequently took Racine and Boileau to Château-Thierry, whither he went from time to[Pg xix] time to sell a few acres of land, in order to enable him to balance his receipts against his expenditure. The amiable Maucroix, another Epicurean, arrived in his turn to complete the revel which was now carried on at Rheims, to which city he gladly enticed his dear La Fontaine, who desired nothing better than to follow him thither, for, as he has himself told us,

"Of all fair cities do I most love Rheims,

At once the beauty and the pride of France."

Madame de la Fontaine soon became weary of this life of dissipation, and ceased to follow her volatile husband to Paris. The separation between the spouses was effected, if not without disputes, at any rate without any legal process. Racine frequently urged his friend to become reconciled to his wife, and it was in compliance with such counsels that he made that celebrated journey to Château-Thierry, from which he returned without having even seen Madame de La Fontaine. The anecdote is well known. "Well, have you seen your wife? Are you reconciled?" "I went to see her; but she was in retirement." "Ah! how charmingly naive!" exclaim the biographers; "what a delightful illustration of the poet's habitual bonhomie and abstraction!" Alas! it is nothing of the kind. La Fontaine knew what he was about. He had set out in compliance with his friend's wish, and, in fulfilment of his promise, he had gone to his house door; but, having found no one at home, he had quietly returned, only too glad that he had redeemed his promise, and avoided an interview which he dreaded. Then, returning to his friends, he put them off with a childish excuse, at which he would not be the last to laugh with all his heart. The whole incident is quite in accordance with the man's character. His weak resolution induced him at first to yield, but the natural buoyancy of his spirit recovered itself, and triumphed in the end.

La Fontaine was now more than forty years of age, and, with the exception of his frigid imitation of Terence's comedy, and his admirable elegy on Fouquet, he had produced nothing which proved that he was anything more than a pleasant and elegant versifier. We must remark, however, that he obtained at this time the position of Gentleman-in-Waiting to the Dowager Duchess of Orleans, widow of Gaston, brother of Louis XIII. The little court of the Luxembourg, at least, if not that of the grand King's, was thrown open to La Fontaine, and he[Pg xx] was received there on terms of the pleasantest intimacy. The office to which he was appointed was not merely honorary, and it justified his acceptance of liberalities of which he was not a little in need. The Duchess of Bouillon also became a patroness of our poet, whom she had met at Château-Thierry; and he was now engaged by this princess of easy manners and voluptuous disposition, to apply his talents to, the imitation in verse of those somewhat too gallant tales which Ariosto and Boccaccio borrowed from our Trouvères. This advice, eagerly followed, opened up to La Fontaine a new vein of his genius, and threw him upon apologue as one of the means of poetic expression. "Joconde" was his first effort in this style; and this tale, freely rendered from Ariosto, was the cause of a literary discussion, in which Boileau broke a lance in the service of his friend with another imitator against whom La Fontaine was then pitted, and who has since been forgotten: it was like Pradon being compared to Racine. The success of this first effort encouraged the author to make fresh ones, and he speedily produced new tales, as ingenious and indecent as the first. Such fame as Fontaine acquired by these tales must not be dilated on; for, although there was nothing in the corrupt ingenuity of the pleasant poet that was deliberately vicious, and although he was sincerely astonished that, on account of a few rather free narratives, he should be accused of corrupting the innocence of youth, we must nevertheless hold that the accusation was well founded.

Recognised and appreciated as La Fontaine's talents now were, he would doubtless have been the object of some of those distinguishing marks of favour which Louis XIV. was ever ready to bestow upon men of genius, had not his irregular mode of life, and the character of some of his later productions, offended the susceptibilities of the monarch and those of the severe Colbert, the administrator of his liberalities. That La Fontaine should have once been the friend of Fouquet is not sufficient to account for this denial of royal favour, since Pélisson, the eloquent defender of the Surintendant, was himself at this period the object of distinguished royal patronage. The fall of Fouquet was, indeed, so terribly complete and hopeless, that his enemies could well afford to allow his friends to shelter themselves under the cloak of amnesty. To say, as some have done, that La Fontaine was neglected because he belonged to the "party of the opposition," is idle;[Pg xxi] for, in the first place, le bonne homme had not the courage to resist the majority, and in the second place, there was nothing he more eagerly desired than to be one of the Court poets. Indeed, he seized every opportunity of celebrating the glories of the reign of Louis the Great.

The real truth is, that he was treated coldly on account of the licentiousness, equally great, both of his verses and his mode of life, at a time when he would merely have had to promise amendment for the future, to have been a participator in the royal benefits, and to have been made a member of the Academy.

La Fontaine had not a conscience entirely pure, and, accordingly, strove to hide his misdoings under cover of works perfectly irreproachable. Uninvited, he now proposed to himself the task of amusing and instructing the Dauphin, whose education had then commenced. It was an honourable method of paying homage to the Court, and of atoning for past errors. The elegance of Phædrus and the simplicity of Æsop had already fascinated him—he was ambitious of imitating them; but although thoroughly skilled in the art of narrating, he never suspected that he was about to eclipse his models. He set himself below Phædrus, and Fontenelle has declared that his doing so was one of his blunders—a piquant word, which we may translate in this instance as "a sincere and even exaggerated admiration for consecrated names." A feeling of and a taste for perfection are, moreover, the surest curb-reins to self-love. The playfulness, delicacy, and ingenuity of La Fontaine's spirit, as well as the natural simplicity of his character, preserved him from the illusions of vanity, and caused him even to misconceive the real value of his genius. It was necessary, then, in the first place, that his true vocation should be revealed to him, and actual fame alone could show that his talent had raised him to the first rank.

His first collection of fables, arranged in six books, appeared in 1668, under the modest title of "Æsop's Fables: Translated into Verse by M. de la Fontaine." The work was dedicated to the Dauphin, and this dedication reveals to us the poet's secret intention in the publication of the volume. At a later period we find him taking a more direct part in the education of the grandson of Louis XIV., through the medium of Fénélon. And now, as we have followed so many others in judging of these inimitable compositions, we remark how slowly La Fontaine's talent developed itself, the better to attain the highest state of maturity.[Pg xxii] If the poet, on the one hand, careless as to fortune, allowed his patrimony to melt away, let us observe how much time, pure air, and sunlight he has given to the peaceful cultivation of his genius. The tree has been covered with branches, the leaves in due season have adorned them, and then fruits the most delicious have appeared craving to be gathered. Oh, careless great one! full well had you the right to spurn all vulgar cares; to devour, as you have said, your capital together with your revenue, since you stored up for yourself another capital, which will give you immortal wealth!

La Fontaine's improvidence may be attributed in some degree to his friends, who seem never to have failed him in any necessity. When death had deprived him of the protection of the Duchess of Orleans, he was immediately adopted, so to speak, by the Duchess de la Sablière, whose generosity provided for all his wants, and whose delicate kindness anticipated all his wishes. It was, doubtless, the gratitude with which this lady inspired him, that drew from La Fontaine's heart those verses, which so many others have since recited in a spirit of bitterness—

"Oh, what it is to have a faithful friend," &c.

And here we have another of those names on which one loves to dwell so fondly. Madame de la Sablière was a genuine patroness of philosophers and men of letters. Her house was always open to them, and her fortune encouraged them to prosecute their labours. Sauveur, Roberval, and Bernier experienced her discreet liberality, which disguised itself only that it might be the more freely bestowed. She loved knowledge, and possessed it without the desire of display; she had a passion for doing good, yet she employed an innocent art in concealing it. The devotion which she displayed in an unholy love was, for this woman, otherwise so irreproachable, only a transition to those transports of sincere piety which occupied the closing years of her life. La Fontaine was, up to the seventy-second year of his life, the familiar genius of Madame de la Sablière's mansion, and passed more than twenty years in it in complete tranquillity, at first as one of a most select circle of wits and philosophers, and afterwards as an independent host, doing himself the honours of the house to a rather miscellaneous circle of visitors, which he gathered round him during[Pg xxiii] the prolonged religious seclusions of his patroness, who latterly devoted herself entirely to care for the safety of her soul.

La Fontaine had no longer any need to secure fresh protectors. His destiny was secured, for, like the rat in the fable,

"Provisions and lodgings! what wanted he more?"

We may now, therefore, be as tranquil on his account as he was himself, merely observing that he took advantage of this security to deliver himself up with a species of fury to the demon of poetry, which never deserted him. His first fables were received with favour, and when he published others he met with a good fortune which is accorded to but few poets, for even the later ones increased his fame. However, this, his favourite species of writing, had not completely absorbed his attention; the romance of "Psyche," and some theatrical pieces, occupied his time at intervals. "Psyche," which still amuses us, amused him also much. He worked at it when he wished to rest from other labours, and also at length completed it. The "Songe de Vaux" was less happy; but how could he recall the enchantments and fairy lore of that château where Fouquet had passed the last years of his life in hopeless captivity? Versailles had surpassed it in magnificence, and La Fontaine employed his descriptive talents in describing the palace whose increasing marvels, which struck every eye, he attached incidentally to the plot of his allegorical fable, already complicated with interlocutors, who may be easily recognised under feigned names as Molière, Boileau, Racine, and La Fontaine. The publication of this romance, of which the prose is elegant, and which also contains many excellent verses, took place soon after that of the first fables. It was received with much favour, and Molière, assisted by Corneille and De Quinault, extracted from it an opera, the music of which was composed by Lulli.

La Fontaine's dramatic attempts were, it must be confessed, seldom happy; but Furetierè certainly exaggerates when he tells us that managers never ventured to give a second representation of his pieces, for fear of being pelted. However this may be, the theatre had a great attraction for La Fontaine, and the society of actors a still greater. When Madame de la Sablière's drawing-room appeared too serious to him, he would go to amuse himself at Champmeslé's,[Pg xxiv] and, whilst Racine shaped the talents of this great actress, La Fontaine assisted her husband in the composition of mediocre comedies, in which we can find but few traces of the poet's skill. It is on this account that he has been made to share the responsibility of the authorship of "Ragotin," a dull imitation of the "Roman Comique." There is little more, indeed, to be said in favour of "Je vous prends sans Verts," which has been attributed to him, and which we may surrender to Champmeslé, who will not gain much, while La Fontaine would certainly lose by it. Of all the pieces put on the stage by Champmeslé, there is only one that we should wish to be able, with a clear conscience, to assign to La Fontaine, and that is "Le Florentin," an amusing little comedy, which contains one scene worthy of Molière. The share which La Fontaine took, or is asserted to have taken, in the composition of these comedies, is difficult to determine. What there can be no doubt of is, that at one time he formed the design of writing a tragedy, and this, perhaps, at the instigation of Racine, who could never refrain from a joke, especially at the expense of his friends. Achilles was the hero selected by our poet; but he prudently paused after having made a commencement.

This brings us to the mention of La Fontaine's one great, solitary, and brief fit of anger. Always ready to yield to the advice of his friends, he imprudently listened to Lulli, who had importuned him to produce, at a very short notice, the libretto of an opera. The music was to be marvellous, the Court would applaud to the skies the author and the composer, and the poet would be free of the theatre, and have acquired all the rights of dramatic authorship. What a temptation was this! La Fontaine courageously set himself to work under the guidance of Lulli, who urged him forward, and day by day made fresh suggestions. The poet readily obeyed the spur, and even yielded to the sacrifice of some of his verses; but he had scarcely finished, when he discovered that his perfidious employer had passed over, with all his musical baggage, to the Proserpine of Quinault. We may judge of the poet's rage. The four months' labour utterly lost; the nights passed without sleep; the treachery of the instigation; the heartless abandonment! Ah! how many causes of complaint had the poet against this traitor! La Fontaine could not contain himself, and[Pg xxv] wrote a satire, compound of gall and bile, in which he complains of having been made a fool of. This fit of passion, however, did not last long. Madame de Thianges brought about a reconciliation between the culprit and the victim, and that without much difficulty, for, after all, Lulli was an excellent companion, and La Fontaine was incapable of nursing anger long. To be angry was a trouble to him, and consequently he never kept up a sense of ill-feeling for any length of time. His friends might become estranged from or quarrel with each other; but he remained on the best of terms with them, and saw them separately. One might have thought that he had taken for his motto the verse of the old poet, Garnier—

"To love I am plighted, but never to hate."

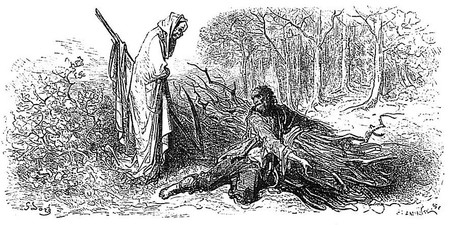

The poetical excursions of La Fontaine out of his own domain added nothing to his renown, and were scarcely perceived amidst the rays of his glory as a fabulist—the title by which he is known to posterity; and it may be added, that the Fable, as it is fashioned by La Fontaine, is one of the happiest creations of the human mind. It is, properly speaking, a charm, as he has said, for in it all the resources of poetry are enclosed in one frame. La Fontaine's apologue is connected with the épopée by the narrative, with the descriptive style by his pictures, with the drama by the play of various personages, and the representation of various characters, and with didactic poetry by the precepts which he inculcates. Nor is this all; for the poet frequently speaks in his own person. The supreme charm of his compositions consists in the vitality with which they are imbued. The illusion is complete, and passes from the poet who has been first subjected to it, to the spectator, whom it entrances. Homer is the only poet who possesses this characteristic in the same degree. La Fontaine has always before his eyes all that he describes, and his description is an actual painting. His spirit, gently moved by the spectacle which at first it enjoys alone, reproduces it in vivid pictures. That simplicity for which he has been praised exists but in the nature of the images which he has chosen as the best means of representing his thoughts, or, rather, his emotions. Properly speaking, we do not so much read La Fontaine's fables as gaze at them; we do not know them by heart, but we have them constantly before our eyes. Let us[Pg xxvi] take as an example "Death and the Woodman," since on this subject two great poets have weakly contended against our fabulist. In this laughable rivalry Boileau and J. B. Rousseau are killed by the spirit of abstraction; whilst La Fontaine triumphs by means of the image which glows before the eyes and penetrates the heart. If we add to the constant attractiveness of living reality the pleasure caused by the representation of humanity under animal symbols, we shall have before us the two active principles of the universal interest excited by La Fontaine's fables—I mean illusion, which excites the imagination; and allusion, which has a reduplicate action on the mind.

We do not pretend to assert that there were no French fabulists in France before La Fontaine. The Trouvères were fabulists, and one of the most remarkable specimens of the literature of the middle ages, the "Romance of the Fox," is a genuine study of feudal society, in the guise of personages selected from the animal kingdom. The resemblance of men to animals in this work is complete, and this strange épopée derives its interest from the allusion, which was so remarkable a characteristic of La Fontaine's fables. But our poet never drew from this abundant source, and was also unaware that Marie de France in the thirteenth century had adopted, in imitation of Æsop, the simplicity of treatment which he himself had surpassed, and that other poets of the same period had not only treated of similar subjects, but had written verses on them, which he reproduced in the full confidence that they were original. La Fontaine drew his materials directly from the Greek, the Latin, or the Oriental, Æsop, Phædrus, and Pilpay were his models; but it must be observed that he might have found amongst French writers guides to that perfection which he alone has attained. P. Blanchet, in "L'Avocat Patelin," has inserted the fable of "The Crow and the Fox," to the first of whom he has given the name of Maitre, adopted by La Fontaine. Clément Marot wrote a little drama, full of grace and playfulness, on the subject of the fable of "The Rat and the Lion;" and Régnier has illumined with his genius the oft-told story of "The Wolf and the Horse." La Fontaine knew no other predecessors, amongst modern poets, than the three above mentioned, and he was at no pains to imitate them. In spite of some few scattered similarities between his writings and theirs, La Fontaine was, on the whole, completely original.

La Fontaine's originality does not consist solely in the particular bent of his imagination, but also in his language. It is true that his style bears the impress of the purity and elegance of the language of his age, and is characterised by that finish which is common to all the great writers of his time; but there is also a peculiar richness, suppleness, and naturalness about his idiom. There is, indeed, a Gallic tone in his writings, which is to be found in the works of no other authors of the same period, and which, though derived from old sources, gives to his works a surprising air of novelty. The use of old words and phrases, which he has revived, is a genuine conquest over the lapse of time, and a convenient method of setting forth ideas which would have been unsuited to the over-strained dignity of classic language. Marot, Rabelais, and Bonaventure des Periers, all contributed to enable La Fontaine to make use of the best colloquial language that has ever been employed by any writer; but La Fontaine's thefts are never discoverable; they blend with such exquisite effect with his own ideas, that they seem rather to be reminiscences than robberies. It is in this way that he has robbed the ancients without betraying himself, and that Horace, Virgil, and Plato, even, have furnished him with happy phrases, which have been obdurate to the efforts of all their translators; phrases which La Fontaine has unconsciously appropriated. His brain took them as they fell in with the current of his thought, and they flowed on with it as though from the same source. Virgil may discover his frigus captabis opacum in "Gouter l'Ombre, et le Frais;" Horace, his O! imitatores, servum pecus in "Quelques Imitateurs sot Bétail, je l'Avoue;" and, again, his at nostri proavi in "Nos Aïeux, Bonnes Gens." But if either Virgil or Horace were to meet with La Fontaine, they would neither exclaim against him as a traitor nor a thief, but only hail him as a brother poet.

La Fontaine was permitted to present his second collection of fables to Louis XIV., and obtained a privilege with respect to its publication which was almost unique; a eulogium on the work being included in its authorisation. Our poet at this period assumed a most discreet air, and out of regard, doubtless, for his patroness, avoided all occasion for scandal. Another, and perhaps a stronger reason was, that he cherished a secret ambition of becoming a member of the Academy. Inspired by this hope, he prevailed on himself so far as to praise Colbert, who had been the vindictive means of the fall of Fouquet. The[Pg xxviii] illustrious fraternity, it must be observed, had given him some intimation that it was willing to elect him, and entreated him to act in such a manner that the election might be unanimous. The goodwill of the Academy was so decided, that, at the death of Colbert, it preferred the fabulist to Boileau, who had the support of the royal favour. But a delay was necessary. The Academy's choice was neither annulled nor confirmed; the final decision being delayed until the death of another of the immortals had created a fresh vacancy, and Boileau and La Fontaine entered the Academy side by side; Boileau as soon as elected, and La Fontaine after a year's delay. As we have already said, he had performed his purgatory, and Louis XIV. had been willing to believe that he would henceforth be discreet. We shall see, however, that La Fontaine had only strength enough to promise, and that he was a living example of the refrain of one of his most charming ballads—

"A promise is one thing—the keeping another."

The desire to become a member of the Academy had been with La Fontaine a passion. He was attracted to the honour as well by his friendship for his comrades as by his love for literature. He rendered himself noticeable by the constancy with which he frequented the Academy, always joining its sittings in time to receive his fee for attendance. One day he was late, and, strict as the rule was, the members present, who knew that this little weekly payment was about all the pocket money their comrade enjoyed, proposed that the rule for that occasion should be relaxed; but La Fontaine was inflexible. Nevertheless, this act of heroism did not prevent Furetière, in the course of his quarrel with the Academy, from stigmatising La Fontaine as a jetonnier. It is well known why this lexicographical abbé, as bilious as reforming grammarians mostly are, entered upon a campaign against his comrades, and how his obstinacy and evil deeds, although he was really in the right, caused his exclusion from the Academy. Fontaine, either through inadvertence or from a feeling of esprit de corps, which is more probably the case, had deposited the fatal black ball for the exclusion of his obstinate friend. The consequence was, that Furetière pursued him with implacable animosity, and showered upon the head of the good old fabulist more than his share of epigrams, which were rather venomous than witty. It was the only attack of this sort that[Pg xxix] La Fontaine had to endure, but it was a particularly sharp one. To style the most inoffensive of men "a monster of perfidy" was the slightest of the onslaughts of the rancorous Abbé of Chalivoix. May Heaven preserve us all from the vengeance of soured friends, for there is nothing to equal their venom and malice!

La Fontaine found himself mixed up in another not less animated Academical quarrel, one in which his opponents did not display so great an absence of courtesy. I refer to the controversy between the ancient and modern schools, which was revived in full Academy by Christopher Perrault. Boileau was as eager in the matter as Racine. La Fontaine enrolled himself in their ranks, with less of partisanship, but equal decision. Thus, the three best instances that the panegyrist of the moderns could have employed in support of his position, were found ranged against him. The turn which the dispute took is singular indeed. Those who were really the rivals of antiquity declared themselves in its favour, while writers of mediocrity, who had much less personal interest in the question than they themselves imagined, proclaimed with fervour the superiority of the moderns. Saint-Sorlin had begun the battle. On Perrault's signal the weapons were snatched up once more, and Lamotte-Houdard continued the war. Strange champions of progress in letters! whom the absurdity of the contrast between their pretensions on behalf of their school and the little merits of themselves, its examples, have almost alone saved from oblivion. In fact, the only thing which remains of the least interest in the bulky files of this controversy is our poet's admirable epistle to the learned Huet, at the time Bishop of Soissons.

As long as La Fontaine was under the watchful eye of Madame de la Sablière, he was guilty of nothing worse than mere peccadilloes; but as soon as she had closed her saloon—having been abandoned by the Marquis de la Fare—and had given herself up to the practice of the most austere devotion, the old infant, whom she had left without a guardian, took advantage of his independence precisely as any school-boy might have done. The princes of the house of Vendôme, who amused themselves in the Temple like real Templars, invited him to their festivals, and led him on by their example. Fresh seductions enticed him to an improper indulgence in pleasures suited only to a time of life far different from his own. It is sad to have[Pg xxx] to record these weaknesses on the part of our poet, but we have, at least, the consolation of knowing that they were expiated by a most sincere repentance.

A serious illness at length warned La Fontaine that it was time for him to refrain from the pursuit of pleasure, and to contemplate the approach of death. He had never, even in the midst of his wildest dissipation, failed in respect for religion: he had neither insulted nor neglected it. The easy morals of men and women of the world in the seventeenth century were by no means a systematic revolt against religious principles. Such persons were quite conscious that they were offending against that which is right, and had no idea of maintaining the contrary. The most licentious of them intended to repent some day. Where such a tone of feeling prevails, a change of life need not be despaired of. It must be acknowledged that La Fontaine was slow to make such a change; but when he did make it, he returned completely to that fervent piety which had led him to resolve in his youth to adopt the sacred calling. Racine, who had long since discarded the brief errors of his youth, nursed his friend during this illness, and procured his reconciliation with the Church. It was he, when at the sick man's pillow, to whom La Fontaine naively proposed to distribute in alms the price which he was to receive for certain copies of a new edition of his "Tales." However, his illness grew daily more serious, and a young vicar of Saint Roch, the Abbé Poujet, was charged with the duty of giving the final direction to Fontaine's penitence. He found him in the best frame of mind, and La Fontaine not only consented to disavow and apologise for his literary offences before a deputation of the Academy, but also promised, should he survive, to write only on moral or religious subjects; and, finally, agreed to sacrifice to the scruples of his director, and the Sorbonne, a comedy in verse, which was about to be represented, and which the poet loved as the child of his old age. This sacrifice was truly meritorious, for it was not accomplished without many regrets. No doubt could exist as to the sincerity of his conversion. La Fontaine accordingly received the last sacrament; and when a rumour was spread abroad that he was dead, it was declared that he had died as a saint. This rumour of his departure, however, was not well founded, for health had returned[Pg xxxi] with peace of soul, and he was yet allowed time to prove, by the rigorous practice of the duties of a Christian, the sincerity of his repentance. Whilst following all the phases of this solemn preparation for death, I am astonished and saddened by the fact that I can behold around the sick man's couch academicians, clergy, and crowds of friends, but neither wife nor child.

While the illustrious and henceforth Christian guest of Madame de la Sablière was recovering his health, his patroness had died at the Incurables, to which she had retired. La Fontaine had scarcely regained his health, when he had to leave the mansion which had afforded him an asylum for more than twenty-two years; he was on the point of quitting it when he met M. d'Hervart, who had come to propose that he should go with him to his hotel in the Rue Plâtrière. La Fontaine's answer is well known. He accepted the offer.

"Which of them loved the other the better?"

It was in this magnificent abode, adorned by the pencil of Mignard, that La Fontaine passed in peace the two years which yet remained to him of life. He still visited the Academy, but he went more frequently to church; he put a few psalms into verse, paraphrased the Dies Iræ, and even yet occasionally found time for the composition of fresh fables. It was in this way that Fénélon was able to give him a share in the education of the young Duke of Burgundy, who furnished subjects which the good old poet put into verse with an infantine delight. The preceptor and his royal pupil rivalled each other in delicate attentions towards the amiable old man, who had not lost by his conversion either his good temper or his wit. Thanks to this high protection, to the vigilance of friendship and the consolation of religion, we shall be able to say, of him when he shall have closed his eyes, "His end was as calm as the close of a summer day."

La Fontaine passed away gently, after a few weeks of extreme weakness, on the 13th of February, 1695, in the seventy-fourth year of his age. Racine saw him die with extreme regret, and Fénélon, deeply affected, expressed in exquisite terms the admiration of his contemporaries. Let us quote the last sentences of this brief funeral oration:—"Read him, and then say whether Anacreon be more gracefully playful; whether Horace has adorned morality with more varied[Pg xxxii] and more attractive ornaments; whether Terence has painted the manners of mankind with more nature and truth; and finally, whether Virgil himself is more touching or more harmonious." We shall not seek for any further homage to his genius; but, as regards his character, we obtain a precious testimony, which has hitherto been unknown to his biographers. On learning of the death of his old friend, Maucroix wrote these touching lines:—"My very dear and faithful friend, M. de La Fontaine, is dead. We were friends for more than fifty years; and I thank God that he allowed our great friendship to survive to a good old age without any interruption or diminution, and that I am able sincerely to say, that I have also tenderly loved him, as much at the last as at the first. God, in his merciful wisdom, has thought fit to take him to his own holy repose. His soul was the most sincere and candid that I have ever met with, and was totally free from anything like guile. I believe that he never told a falsehood in his life."

GERUZEZ.

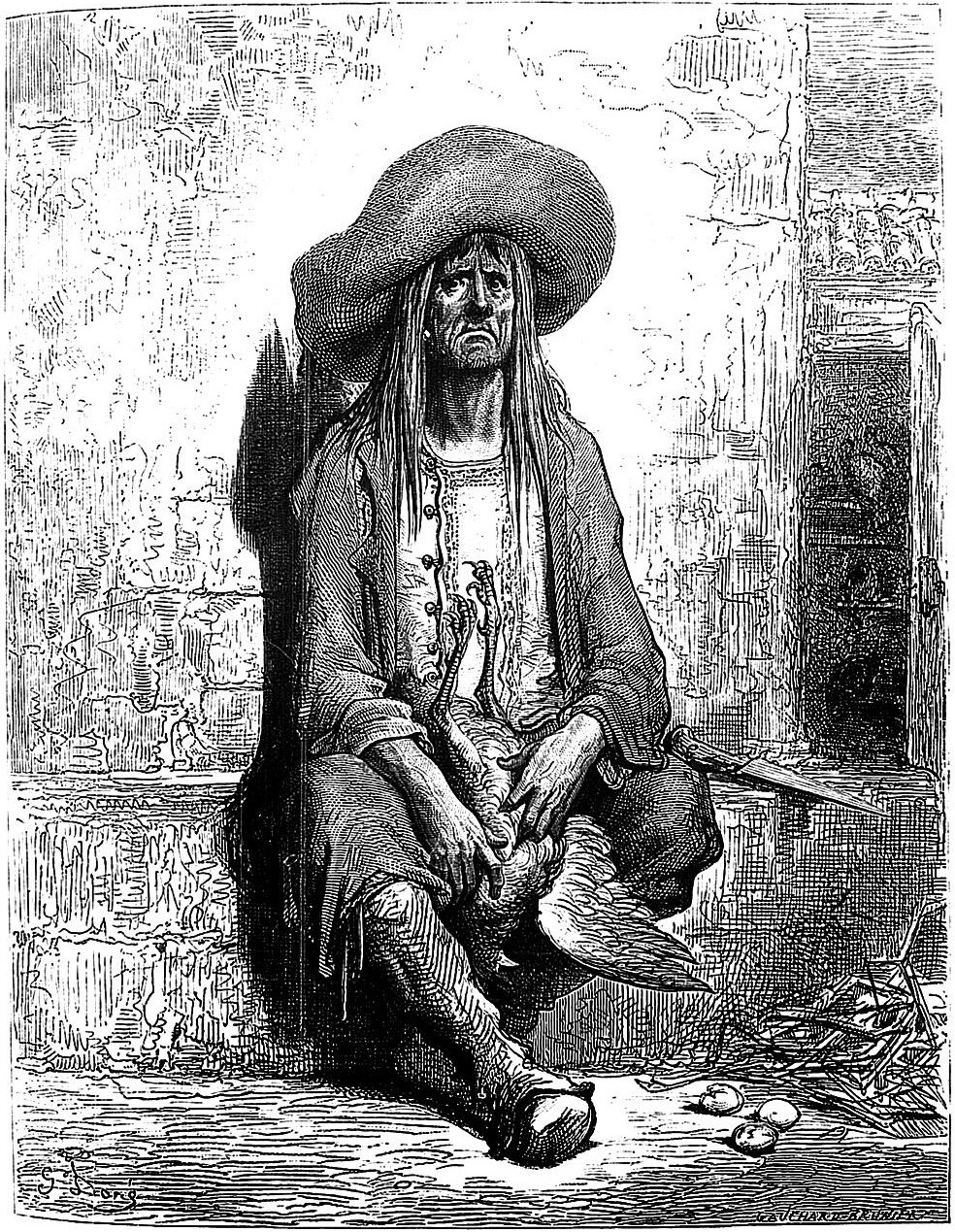

We have no certain records concerning the births of either Homer or Æsop; and scarcely any important circumstance is known respecting their lives: which is somewhat strange, since history readily fathers facts far less interesting and useful. Many destroyers of nations, many ignoble princes, too, have found chroniclers of the most trifling particulars of their lives, and yet we are ignorant of the most important of those of Homer and Æsop—that is to say, of the two persons who have most deserved well of posterity: for Homer is not only the father of the gods, but also of all good poets; whilst Æsop seems to me to be one of those who ought to be reckoned amongst the wise men for whom Greece is so celebrated, since he taught true wisdom, and taught it with more skill than is employed by those who lay down mere definitions and rules. Biographies of these two great men have certainly been written, but the best critics regard both these narratives as fabulous, and particularly that written by Planudes. For my own part I cannot coincide in this criticism; for as Planudes lived in an age when the remembrance of circumstances respecting[Pg xxxiv] Æsop might well be still kept alive,[1] I think it is probable that he had learnt by tradition the particulars he has left us concerning him. Entertaining this belief, I have followed him, suppressing nothing which he has said of Æsop,[2] save such particulars as have appeared to me either too puerile or else wanting in good taste.

Æsop was a Phrygian, a native of a town called Amorium, and was born about the fifty-seventh Olympiad, some two centuries after the foundation of Rome. It is hard to say whether he had to thank or to complain of Nature; for whilst she gave him a keen intelligence, she also afflicted him with a deformed body and ugly face—so deformed and so ugly, indeed, that he scarcely resembled a man; and, moreover, she had almost entirely deprived him of the use of speech. Encumbered by such defects as these, if he had not been born a slave, he could scarcely have failed to become one; but at the same time his soul ever remained free and independent of the freaks of fortune.

The first master whom he had sent him to labour in the fields, either because he thought him unfitted for anything else, or because he wished to avoid the sight of so disagreeable an object. It happened, on a [Pg xxxv]certain occasion, that this master, on paying a visit to his country house, was presented by a peasant with some figs, which he found so good that he had them carefully locked up, giving directions to his butler, who was named Agathopus, to bring them to him when he should leave the bath. It chanced that Æsop had occasion to visit the mansion at this time, and as soon as he had entered it, Agathopus took advantage of the opportunity to share the figs with some of his friends, and then throw the blame of the theft on Æsop, never supposing that he would be able to defend himself from the charge, as he not only stammered, but appeared to be an idiot. The punishments inflicted on their slaves by the ancients were very cruel, and this was an aggravated theft. Poor Æsop threw himself at his master's feet, and making himself understood as well as he could, he begged that his punishment might be deferred for a few moments. This favour having been accorded him, he fetched some warm water, and having drunk it in his master's presence, thrust his finger down his throat. He vomited, and nothing came up but the water as it went down. Having thus proved his own innocence, he made signs that the others should be compelled to do as he had done. Every one was astonished, scarcely believing that Æsop could have devised such a scheme. Agathopus and his companions in the theft drank the water and thrust their fingers down their throats, as the Phrygian had done, and straightway the figs, still undigested, re-appeared with the water. By this means Æsop proved his innocence, and his accusers were punished for their theft and malice.

On the following day, when the master had set off for town, and Æsop was at his usual work, some travellers who had lost their way entreated him, in the name of hospitable Jove, to show them their right road to the town. Upon this, Æsop first prevailed upon them to repose for a time in the shade, and then, after having refreshed them with a slight collation, became himself their guide, not leaving them until he had put them well on their right road. The good people raised their hands to heaven, and besought Jupiter that he would not leave this charitable act unrewarded. Æsop had scarcely left them, when, overcome with heat and with weariness, he fell asleep. During his slumber he dreamt the goddess Fortune appeared before him, and, having untied his tongue, bestowed upon him that art of which he may be termed the author. Startled with delight at such a dream, he at once awoke, and,[Pg xxxvi] leaping up, exclaimed, "What is this? my voice is free, and I can pronounce the words 'plough,' 'rake,' and, in fact, everything I choose!"

This miracle was the cause of his changing masters, for a certain Zenas, who acted as steward on the estate, and who superintended the slaves, having beaten one outrageously for a fault which did not merit such severe punishment, Æsop could not refrain from reproving him, and threatened to make known his bad conduct. Zenas, with the purpose of anticipating Æsop and avenging himself upon him, went to the master and told him a prodigy had happened in his house—that the Phrygian had recovered the use of speech, but that the wretch only made use of his gift to blaspheme and say evil things of his master. The latter believed him, and went beyond this, for he gave Æsop to Zenas, with liberty to do what he liked with him. On returning to the fields, Zenas was met by a merchant, who asked him whether he would sell him some beast of burden. "I cannot do that," said Zenas; "but I will sell you, if you like, one of our slaves;" and then sent for Æsop. On seeing Æsop the merchant said, "Is it to make fun of me that you propose to sell me such a thing as that? One would take him for an ape." Having thus spoken, the merchant went off, half grumbling and half laughing at the beautiful object which had just been shown him. But Æsop called him back, and said, "Take courage and buy me, and you will find that I shall not be useless. If you have children who cry and are naughty, the very sight of me will make them quiet; I shall serve, in fact, as a real old bogy." This suggestion so amused the merchant, that he purchased Æsop for three oboli, and said to him, laughing, "The gods be praised! I have not got hold of any great prize; but then on the other hand I have not spent much money."

Amongst other goods this merchant bought and sold slaves: and as he was on his way to Ephesus to offer for sale those that he had, such things as were required for use on the journey were laid on the backs of each slave in proportion to his strength. Æsop prayed that, out of regard to the smallness of his stature, and the fact that he was a new comer, he might be treated gently; his comrades replied that he might refrain from carrying anything at all, if he chose. But as Æsop made it a point of honour to carry something like the rest, they allowed him to select his own burden, and he selected the bread-basket, which was the heaviest burden of all. Every one believed that he had[Pg xxxvii] done this out of sheer folly; but at dinner-time the basket was lightened of some of its load; the same thing happened at supper, then on the following day, and so on; so that on the second day he walked free of any burden, and was much admired for the keenness of his wit.

As for the merchant, he got rid of his slaves, with the exception of a grammarian, a singer, and Æsop, whom he intended to expose for sale at Samos. Before taking them to the market-place he had the two first dressed as well as he could, whilst Æsop, on the other hand, was only clad in an old sack, and placed between his two companions to set them off. Some intending purchasers soon presented themselves, and amongst others a philosopher named Xantus. He asked of the grammarian and the singer what they could do. "Everything," they replied; on which Æsop laughed in a manner which may be well imagined, and, indeed, Planudes asserts that his grin was so terrible that the bystanders were almost on the point of taking flight. The merchant valued the singer at a thousand oboli, the grammarian at three thousand, and said that whoever first purchased one of the two should have the other thrown in. The high price of the singer and the grammarian disgusted Xantus, but, that he might not return home without having made some purchase, his disciples persuaded him to buy that little make-believe of a man who had laughed with such exquisite grace. He would be useful as a scarecrow, said some; as a buffoon, said others. Xantus allowed himself to be persuaded, and consented to give sixty oboli for Æsop, but before he completed the bargain demanded of him, as he had of his comrades, for what work he was fitted; to which Æsop replied, "For nothing, as his two companions had monopolised all possible work." The clerk of the market, taking the droll nature of the purchase into consideration, graciously excused Xantus from paying the usual fee.

Xantus had a wife of very delicate tastes, who was extremely particular as to the style of persons she allowed to be about her. Xantus knew, therefore, that to present his new slave to her in the ordinary way would be to excite not only her ridicule but her anger. He resolved, accordingly, to make the presentation a subject of pleasantry, and spread a report through the mansion that he had purchased a young slave as handsome as ever was seen. Having heard this, the young girls who waited on the mistress were ready to[Pg xxxviii] tear each other to pieces for the sake of having the new slave as her own particular servant; and their astonishment at the appearance of the new-comer may well be imagined. One hid her face in her hands, another fled, and a third screamed. The mistress of the house, for her part, said that she could very well see that this monster had been brought to drive her away from the house, and that she had long perceived that the philosopher was tired of her. Word followed word, and the quarrel at length became so hot that the lady demanded her goods, and declared that she would return to her parents. Xantus, however, by means of his patience, and Æsop by means of his wit, contrived to arrange matters. The lady resigned her project of insisting upon a divorce from bed and board, and admitted that she might possibly in time become accustomed to even so ugly a slave.

I have omitted many little circumstances in which Æsop displayed the liveliness of his wit; for although they all serve as proofs of the keenness of his mind, they are not sufficiently important to be recorded. We will merely give here a single specimen of his good sense and of his master's ignorance. The latter on a certain occasion went to a gardener's to choose a salad for himself; and when the herbs had been selected, the gardener begged the philosopher to satisfy him with respect to something which concerned him, the philosopher, as much as it concerned gardening in general, and it was this: that the herbs which he planted and cultivated with great care did not prove so valuable as those which the earth produced of itself without any thought. Xantus attributed the whole thing to the will of Providence, as persons are apt to do when they are puzzled. Æsop having overheard the conversation, began to laugh, and having drawn his master aside, advised him to say that he had made so general a reply because it was not suited to his dignity to answer such trivial questions, but that he would leave its solution to his slave-boy, who would doubtless satisfy the inquirer. Then, Xantus having gone to walk at the other end of the garden, Æsop compared the garden to a woman who, having children by a first husband, should espouse a second husband who should have children by a first wife. His new wife would not fail to form feelings of aversion for her step-children, and would deprive them of their due nourishment for the sake of benefiting her own. And it was thus with the earth, which adopted only with reluctance the productions of labour[Pg xxxix] and culture, and reserved all her tenderness and benefits for her own productions alone—being a step-mother to the former, and a passionately fond mother of the latter. The gardener was so delighted with this answer, that he offered Æsop the choice of anything in his garden.

Some time after this a great difference took place between Xantus and his wife. The philosopher, being at a feast, put aside certain delicacies, and said to Æsop, "Carry these to my loving pet;" upon which Æsop gave them to a little dog of which his master was very fond. Xantus, on returning home, did not fail to inquire how his wife liked his present, and as the latter evidently did not understand what he meant, Æsop was sent for to give an explanation. Xantus, who was only too willing to find a pretext for giving his slave a thrashing, asked him whether he had not expressly said, "Carry those sweet things from me to my loving pet?" To which Æsop replied, that Xantus's loving pet was not his wife, who for the least word threatened to sue for a divorce, but his little dog, who patiently endured the harshest language, and which, even after having been beaten, returned to be caressed. The philosopher was silenced by this reply, but his wife was thrown into such a passion by it that she left the house. Xantus employed in vain every relation and friend to endeavour to induce her to return, both prayers and arguments being equally lost upon her. In this dilemma Æsop advised his master to have recourse to a stratagem. He went to the market, and having bought a quantity of game and such things, as though for a sumptuous wedding, managed to be met by one of the lady's servants. The latter, of course, asked why he had bought all those good things, upon which Æsop replied that his master, being unable to persuade his wife to return to him, was about to wed another. As soon as the lady heard this news she was naturally constrained, by the spirit of jealousy and contradiction, to return to her husband's side. She did not do this, however, without being resolved to be avenged some time or other on Æsop, who day after day played some prank, and yet always succeeded by some witty scheme in avoiding punishment. The philosopher found his new slave more than his match.

On a certain market-day Xantus, having resolved to regale some friends, ordered Æsop to purchase the best of everything, and nothing else. "Ah!" said the Phrygian to himself, "I will teach you to specify what you want, and not to trust to the discretion of a slave." He went[Pg xl] accordingly and purchased a certain number of tongues, which he had served up with various sauces as entrées, entremets, and so forth. When the tongues first appeared at table, the guests praised the choice of this dish, but when it appeared in constant succession, they became disgusted with it; and Xantus exclaimed, "Did I not bid you buy whatever was best in the market?" "Well," replied Æsop, "and what is better than the tongue? It is the very bond of civilised life, the key of all the sciences, the organ of reason and truth; by its aid we build cities and organise municipal institutions; we instruct, persuade, and, what is more than all, we perform the first of all duties, which is that of offering up prayers to the gods." "Ah! well," said Xantus, who thought that he would catch him in a trap at last, "purchase then for me to-morrow the worst of everything; the same gentlemen who are now present will dine with me, and I should like to give them some variety."

On the following day Æsop had only the same dish served at table, saying that "the tongue is the worst thing which there is in the world; for it is the author of wars, the source of law-suits, and the mother of every species of dissension. If it be argued that it is the organ of truth, it may with equal veracity be maintained that it is the organ of error, and, what is worse, of calumny. By its means cities are destroyed, and men exhorted to the performance of evil deeds. If, on the one hand, it sometimes praises the gods, on the other it more frequently blasphemes them." Upon this one of the company said to Xantus, that certainly this varlet was very necessary to him, for he was more calculated than any one else to exercise the patience of a philosopher.

"About what are you in trouble?" said Æsop. "Ah! find me," replied Xantus, "a man who troubles himself about nothing." Æsop went on the following day to the market-place, and perceiving there a peasant who regarded all things with the utmost stolidity, he took him to his master's house. "Behold," said he to Xantus, "the man without cares whom you have demanded." Xantus then bade his wife heat some water, put it in a basin, and wash with her own hands the stranger's feet. The peasant allowed this to be done, although he knew very well that he did not deserve any such honour, and merely said to himself, "Perhaps it is the custom in this part of the world." He was then conducted to the place of honour, and took his seat without ceremony. During the repast Xantus did nothing but blame his cook. Nothing[Pg xli] pleased him. If anything was sweet, he declared that it was too salt, and blamed everything that was salt for being repulsively sweet. The man without cares let him talk on, and meanwhile ate away with all his might. At dessert a cake was placed on the table, which had been made by the philosopher's wife, and which Xantus scoffed at, although it was in reality very good. "Behold!" cried the philosopher, "the most wretched pastry I have ever eaten. The maker of it must be burnt alive, for she will never do any good in the world. Let faggots be brought!" "Wait," said the peasant, "and I will go and fetch my wife, so that they may be both burned at the same stake." This final speech disconcerted the philosopher, and deprived him of the hope of being able to catch Æsop in a trap.

But it was not only with his master that Æsop played jokes and found opportunities for witticisms. Xantus having sent him to a certain place, he met on his way a magistrate, who asked him where he was going; and Æsop, either out of thoughtlessness or for some other reason, replied that he did not know. The magistrate, regarding this answer as a mark of disrespect to himself, had him conveyed to prison. But as the officers were hauling him off, Æsop cried out, "Did I not give a proper reply? Could I know that I was going to prison?" Upon this the magistrate had him released, and considered Xantus fortunate in having so witty a slave.

Xantus now began to perceive how important it was for his own interests to have a slave in his possession who did him so much honour. Well, it occurred on a certain occasion that Xantus, having a revel with his disciples, it became soon evident to Æsop, who was in attendance, that the master was becoming as drunk as the scholars. "The effects of drinking wine," said he to them, "may be divided into three different stages. In the first stage the result is pleasurable emotions; in the second, mere intoxication; and in the third, madness." These remarks were received with a roar of laughter, and the wine-bibbing went on more furiously than before. Xantus, in fact, got so drunk that he lost all command over his brains, and swore that he could drink up the sea. This declaration, of course, raised a great guffaw amongst his boon companions, and the natural result was, that Xantus, irritated beyond all bounds, offered to wager his house that he would drink up the whole sea, and, to bind the wager, deposited a valuable ring which he wore on his finger.