|

List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

THE SUBTROPICAL GARDEN.

Works by the same Author.

/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\

ALPINE FLOWERS FOR ENGLISH GARDENS. With 70 Illustrations.

THE WILD GARDEN, or our Groves and Shrubberies made beautiful by the naturalisation of hardy exotic plants. With Frontispiece.

MUSHROOM CULTURE: its Extension and Improvement. With Illustrations.

Nearly Ready.

HARDY FLOWERS; or, HERBACEOUS, BULBOUS, AND ALPINE PLANTS. This will be the most comprehensive and practically instructive book ever published on these plants. With Frontispiece.

A CATALOGUE OF CULTIVATED HARDY PERENNIALS, BULBS, ANNUALS, etc., including also all British Plants. Prepared for the purpose of facilitating exchanges, &c., and enumerating nearly 10,000 hardy exotic and British plants.

BY W. ROBINSON, F.L.S.,

AUTHOR OF ‘ALPINE FLOWERS,’ ‘THE WILD GARDEN,’ ‘HARDY FLOWERS,’ ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET.

1871.

The right of Translation is reserved.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET

AND CHARING CROSS.

![]()

THIS book is written with a view to assist the newly-awakened taste for something more than mere colour in the flower-garden, by enumerating, describing, indicating the best positions for, and giving the culture of, all our materials for what is called “subtropical gardening.” This not very happy, not very descriptive name, is adopted from its popularity only; fortunately for our gardens numbers of subjects not from subtropical climes may be employed with great advantage. Subtropical gardening means the culture of plants with large and graceful or remarkable foliage or habit, and the association of them with the usually low-growing and brilliant flowering-plants now so common in our gardens, and which frequently eradicate every trace of beauty of form therein, making the flower-garden a thing of large masses of colour only.

The guiding aim in this book has been the selection of really suitable subjects, and the rejection of many that have been recommended and tried for this purpose. This point is more important than at first sight would appear, for in most of the literature hitherto devoted to the subject plants entirely unsuitable are named. Thus we find such things as Alnus glandulosa aurea and Ulmus campestris aurea (a form of the common elm) enumerated among subtropical plants by one author. Manifestly if these are admissible almost every species of plant is equally so. These belong to a class of variegated hardy subjects that have been in our gardens for ages, and have nothing whatever to do with subtropical gardening. Two other classes have also purposely been omitted: very tender stove-plants, many of which have been tried in vain in the Paris and London Parks, and such things as Echeveria secunda, which though belonging to a type frequently enumerated among subtropical plants, are, more properly, subjects of the bedding class. But if I have excluded many that I know to be unsuitable, every type of the vegetation of northern and temperate countries has been searched for valuable kinds; and as no tropical or subtropical subject that is really effective has been omitted, the result is the most complete selection that is possible from the plants now in cultivation.

No pains have been spared to show by the aid of illustrations the beauty of form displayed by the various types of plants herein enumerated. For some of the illustrations I have to thank MM. Vilmorin and Andrieux, the well-known Parisian firm; for others, the proprietors of the ‘Field;’ while the rest are from the graceful pencil of Mr. Alfred Dawson, and engraved by Mr. Whymper and Mr. W. Hooper. I felt that engravings would be of more than their usual value in this book, inasmuch as they place the best attainable result before the reader’s eye, thus enabling him to arrange his materials more efficiently. A small portion of the matter of this book originally appeared in my book on the gardens of Paris, in which it will not again be printed. For the extensive list of the varieties of Canna I am indebted to M. Chatè’s “Le Canna.” Most of the subjects have been described from personal knowledge of them, both in London and Paris gardens.

W. R.

April 3, 1871.

![]()

| PART I. | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION AND GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS | 1 |

| PART II. | |

| DESCRIPTION, ARRANGEMENT, CULTURE, ETC., OF SUITABLE SPECIES, HARDY AND TENDER, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED | 43 |

| PART III. | |

| SELECTIONS OF PLANTS FOR VARIOUS PURPOSES | 221 |

![]()

Separate plates to face the pages given.

| PAGE | |

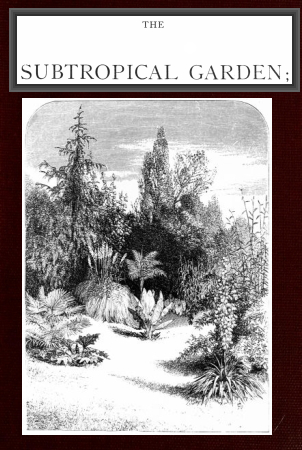

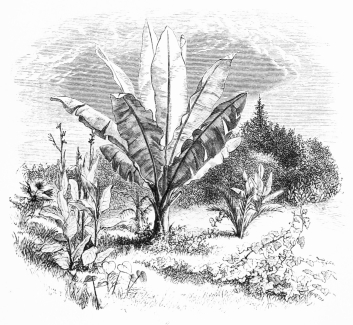

| Frontispiece—Hardy and tender Plants in the Subtropical Garden. | |

| Cannas in a London park | 13 |

| Anemone japonica alba | 17 |

| Group and single specimens of plants isolated on the grass | 23 |

| Portion of plan showing Yuccas, etc. | 25 |

| Formal arrangements in London parks | 26 |

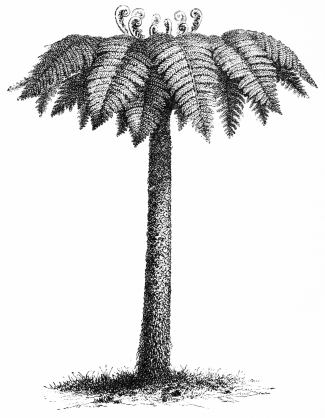

| Tree Ferns and other Stove Plants | 28 |

| Ailantus and Cannas | 30 |

| Young Conifers, etc. | 32 |

| Gourds | 34 |

| Section of raised bed at Battersea | 40 |

| Acanthus latifolius | 47 |

| Aralia canescens | 58 |

| Aralia japonica | 60 |

| Aralia papyrifera | 61 |

| Asplenium Nidus-avis | 70 |

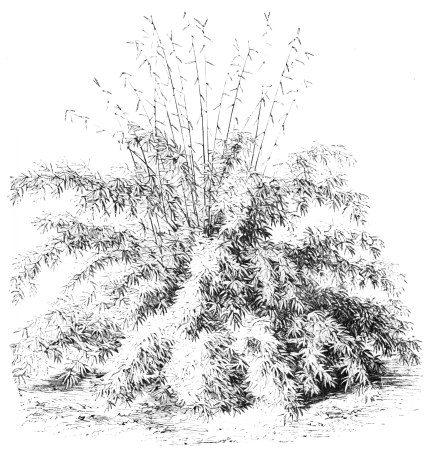

| Bambusa aurea | 72 |

| Bambusa falcata | 74 |

| Berberis nepalensis | 79 |

| Blechnum brasiliense | 80 |

| Bocconia cordata | 81 |

| Buphthalmum speciosum | 83 |

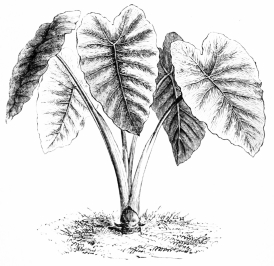

| Caladium esculentum | 84 |

| Colocasia odorata | 85 |

| Canna | 86 |

| Carlina acaulis | 110 |

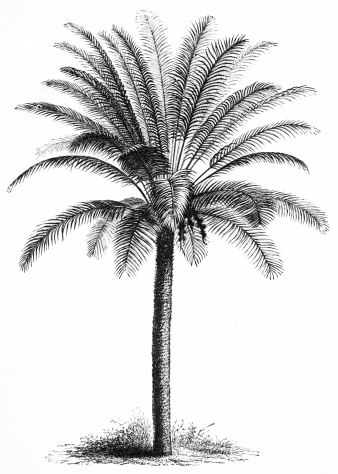

| Caryota sobolifera | 111 |

| Centaurea babylonica | 112 |

| Chamædorea | 114 |

| Chamærops excelsa | 116 |

| Cycas | 120 |

| Tree Fern | 123 |

| Dimorphanthus mandschuricus | 124 |

| Erianthus Ravennæ | 132 |

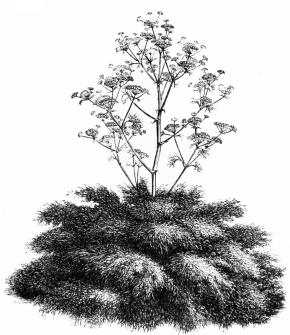

| Ferula communis | 136 |

| Ficus elastica | 139 |

| Gynerium argenteum | 142 |

| Gunnera scabra | 144 |

| Heracleum | 147 |

| Malva crispa | 153 |

| Melianthus major | 155 |

| Monstera deliciosa | 156 |

| Montagnæa heracleifolia | 157 |

| Morina longifolia | 158 |

| Mulgedium alpinum | 159 |

| Musa Ensete | 160 |

| Nicotiana Tabacum | 163 |

| Onopordum Acanthium | 164 |

| Poa fertilis | 174 |

| Rheum Emodi | 178 |

| Rhus glabra laciniata | 180 |

| Seaforthia elegans | 185 |

| Solanum robustum | 190 |

| Solanum Warscewiczii | 195 |

| Uhdea bipinnatifida | 205 |

| Wigandia macrophylla | 208 |

| Yucca filamentosa | 212 |

| Yucca pendula | 214 |

| Yucca filamentosa variegata | 217 |

![]()

SUBTROPICAL GARDENING.

![]()

The system of garden-decoration popularly known as “Subtropical,” and which simply means the use in gardens of plants having large and handsome leaves, noble habit, or graceful port, has taught us the value of grace and verdure amid masses of low, brilliant, and unrelieved flowers, and has reminded us how far we have diverged from Nature’s ways of displaying the beauty of vegetation, our love for rude colour having led us to ignore the exquisite and inexhaustible way in which plants are naturally arranged. In a wild state brilliant blossoms are usually relieved by a setting of abundant green; and even where mountain and meadow plants of one kind produce a wide blaze of colour at one season, there is intermingled a spray of pointed grass and other leaves, which tone down the mass and quite separate it from anything shown by what is called{4} the “bedding system” in gardens. When we come to examine the most charming examples of our own indigenous or any other wild vegetation, we find that their attraction mainly depends on flower and fern, trailer, shrub, and tree, sheltering, supporting, relieving and beautifying each other, so that the whole array has an indefinite tone, and the mind is satisfied with the refreshing mystery of the arrangement.

We may be pleased by the wide spread of purple on a heath or mountain, but when we go near and examine it in detail, we find that its most exquisite aspect is seen in places where the long moss cushions itself beside the ling, and the fronds of the Polypody peer forth around little masses of heather. Everywhere we see Nature judicious in the arrangement of her highest effects, setting them in clouds of verdant leafage, so that monotony is rarely produced—a state of things which it is highly desirable to attain as far as possible in the garden.

We cannot attempt to reproduce this literally—nor would it be wise or convenient to do so—but assuredly herein will be found the chief source of true beauty and interest in our gardens as well as in those of Nature; and the more we keep this{5} fact before our eyes, the nearer will be our approach to truth and success.

Nature in puris naturalibus we cannot have in our gardens, but Nature’s laws should not be violated; and few human beings have contravened them more than our flower-gardeners during the past twenty years. We should compose from Nature, as landscape artists do. We may have in our gardens—and without making wildernesses of them either—all the shade, the relief, the grace, the beauty, and nearly all the irregularity of Nature.

Subtropical gardening has shown us that one of the greatest mistakes ever made in the flower-garden was the adoption of a few varieties of plants for culture on a vast scale, to the exclusion of interest and variety, and, too often, of beauty or taste. We have seen how well the pointed, tapering leaves of the Cannas carry the eye upwards; how refreshing it is to cool the eyes in the deep green of those thoroughly tropical Castor-oil plants, with their gigantic leaves; how grand the Wigandia, with its wrought-iron texture and massive outline, looks, after we have surveyed brilliant hues and richly-painted leaves; how greatly the sweeping palm-leaves beautify the{6} British flower-garden; and, in a word, the system has shown us the difference between the gardening that interests and delights all beholders, as well as the mere horticulturist, and that which is too often offensive to the eye of taste, and pernicious to every true interest of what Bacon calls the “purest of humane pleasures.”

But are we to adopt this system in its purity? as shown, for example, by Mr. Gibson when superintendent of Battersea Park. Certainly not. It is evident, that to accommodate it to private gardens an expense and a revolution of appliances would be necessary, which are in nearly all cases quite impossible, and if possible, hardly desirable. We can, however, introduce into our gardens most of its better features; we can vary their contents, and render them more interesting by a better and nobler system. The use of all plants without any particular and striking habit, or foliage, or other desirable peculiarity, merely because they are natives of very hot countries, should be tabooed at once, as tending to make much work, and to return—a lot of weeds; for “weediness” is all that I can ascribe to many Solanums and stove plants, of no real merit, which have been employed under this name. Selection of the most{7} beautiful and useful from the great mass of plants known to science is one of the most important of the horticulturist’s duties, and in no branch must he exercise it more thoroughly than in this. Some of the plants used are indispensable—the different kinds of Ricinus, Cannas in great variety, Polymnia, Colocasia, Uhdea, Wigandia, Ferdinanda, Palms, Yuccas, Dracænas, and fine-leaved plants of coriaceous texture generally. A few specimens of these may be accommodated in many gardens; they will embellish the houses in winter, and, transferred to the open garden in summer, will lend interest to it when we are tired of the houses. Some Palms, like Seaforthia, may be used with the best effect for the winter decoration of the conservatory, and be placed out with a good result, and without danger, in summer. Many fine kinds of Dracænas, Yuccas, Agaves, etc., which have been seen to some perfection at our shows of late, are eminently adapted for standing out in summer, and are in fact benefited by it. Among the noblest ornaments of a good conservatory are the Norfolk Island and other tender Araucarias; and these may be placed out for the summer, much to their advantage, because the rains will thoroughly clean and freshen them for winter{8} storing. So with some Cycads and other plants of distinct habit—the very things best fitted to add to the attractions of the flower-garden. Thus we may, in all but the smallest gardens, enjoy all the benefits of what is called Subtropical Gardening, without creating any special arrangements for it.

But what of those who have no conservatory, no hothouses, no means for preserving large tender plants in winter? They too may enjoy the beauty which plants of fine form afford. A better effect than any yet seen in an English garden from tender plants may be obtained by planting hardy ones only! There is the Pampas grass, which when well grown is unsurpassed by anything that requires protection. There are the Yuccas, noble and graceful in outline, and thoroughly hardy, and which, if planted well, are not to be surpassed, if equalled, by anything of like habit we can preserve indoors. There are the Arundos, conspicua and Donax, things that well repay for liberal planting; and there are fine hardy herbaceous plants like Crambe cordifolia, Rheum Emodi, Ferulas, and various graceful umbelliferous plants that will furnish effects equal to any we can produce by using the tenderest exotics. The{9} Acanthuses too, when well grown, are very suitable for this use. Then we have a hardy Palm, that has preserved its health and greenness in sheltered positions, where its leaves could not be torn to shreds by storms, through all our recent hard winters.

And when we have obtained these, and many like subjects, we may associate them with not a few things of much beauty among trees and shrubs—with elegant tapering young pines, many of which, like Cupressus nutkaensis and the true Thuja gigantea, have branchlets as graceful as a Selaginella; not of necessity bringing the larger things into close or awkward association with the humbler and dwarfer subjects, but sufficiently so to carry the eye from the minute and pretty to the higher and more dignified forms of vegetation. By a judicious selection from the vast number of hardy plants now obtainable in this country, and by associating with them, where it is convenient, house plants that may be placed out for the summer, we may arrange and enjoy charms in the flower-garden to which we are as yet strangers, simply because we have not sufficiently selected from and utilized the vast amount of vegetable beauty at our disposal.{10}

In dealing with the tenderer subjects, we must choose such as will make a healthy growth in sheltered places in the warmer parts of England and Ireland at all events. There is some reason to believe that not a few of the best will be found to flourish much further north than is generally supposed. In all parts the kinds with permanent foliage, such as the New Zealand flax and the hardier Dracænas, will be found as effective as around London and Paris; and to such the northern gardener should turn his attention as much as possible. Even if it were possible to cultivate the softer-growing kinds, like the Ferdinandas, to the same perfection in all parts as in the south of England, it would by no means be everywhere desirable, and especially where expense is a consideration, as these kinds are not capable of being used indoors in winter. The many fine permanent-leaved subjects that stand out in summer without the least injury, and may be transferred to the conservatory in autumn, there to produce as fine an effect all through the cold months as they do in the flower-garden in summer, are the best for those with limited means.

But of infinitely greater importance are the hardy plants; for however few can indulge in the{11} luxury of rich displays of tender plants, or however rare the spots in which they may be ventured out with confidence, all may enjoy those that are hardy, and that too with infinitely less trouble than is required by the tender ones. Those noble masses of fine foliage displayed to us by tender plants have done much towards correcting a false taste. What I wish to impress upon the reader is, that in whatever part of these islands he may live, he need not despair of producing sufficient similar effect to vary his flower-garden or pleasure-ground beautifully by the use of hardy plants alone; and that the noble lines of a well-grown Yucca recurva, or the finely chiselled yet fern-like spray of a graceful young conifer, will aid him as much in this direction as anything that requires either tropical or subtropical temperature.

Since writing the preceding remarks I have visited America, and when on my way home landed at Queenstown with a view of seeing a few places in the south of Ireland, and among others Fota Island, the residence of Mr. Smith Barry, where I found a capital illustration of what may be easily effected with hardy plants alone. Here an island is planted with a hardy bamboo (Bambusa falcata), which thrives so freely{12} as to form great tufts from 16 ft. to 20 ft. high. The result is that the scene reminds one of a bit of the vegetation of the uplands of Java, or that of the bamboo country in China. The thermometer fell last December (1870) seventeen degrees below freezing point, so that they suffered somewhat, but their general effect was not much marred. Accompanying these, and also on the margins of the water, were huge masses of Pampas grass yet in their beauty of bloom, and many great tufts of the tropical-looking New Zealand flax, with here and there a group of Yuccas. The vegetation of the islands and of the margins of the water was composed almost solely of these, and the effect quite unlike anything usually seen in the open air in this country. Nothing in such arrangements as those at Battersea Park equals it, because all the subjects were quite hardy, and as much at home as if in their native wilds. Remember, in addition, that no trouble was required after they were planted, and that the beauty of the scene was very striking a few days before Christmas, long after the ornaments of the ordinary flower-garden had perished. The whole neighbourhood of the island was quite tropical in aspect; and, as behind the silvery plumes of the Pampas{13} grass and the slender wands of the bamboo the exquisitely graceful heads of the Monterey and other cypresses and various pines towered high in the air, it was one of the most charming scenes I have yet enjoyed in the pleasure-grounds of the British Isles. And this, which was simply the result of judiciously planting three or four kinds of hardy plants, will serve to suggest how many other beautiful aspects of vegetation we may create by utilising the rich stores within our reach.

We will next speak of arrangement and sundry other matters of some importance in connection with this subject. The radical fault of the “Subtropical Garden,” as hitherto seen, is its lumpish monotony and the almost total neglect of graceful combinations. It is fully shown in the London parks every year, so that many people will have seen it for themselves. The subjects are not used to contrast with or relieve others of less attractive port and brilliant colour, but are generally set down in large masses. Here you meet a troop of{14} Cannas, numbering 500, in one long formal bed—next you arrive at a circle of Aralias, or an oval of Ficus, in which a couple of hundred plants are so densely packed that their tops form a dead level. Isolated from everything else as a rule these masses fail to throw any natural grace into the garden, but, on the other hand, go a long way towards spoiling the character of the subjects of which they are composed. For it is manifest that you get a far superior effect from a group of such a plant as the Gunnera, the Polymnia, or the Castor-oil plant, properly associated with other subjects of entirely diverse character, than you can when the lines or masses of such as these become so large and so estranged from their surroundings that there is no relieving point within reach of the eye. A single specimen or small group of a fine Canna forms one of the most graceful objects the eye can see. Plant a rood of it, and it soon becomes as attractive as so much maize or wheat. No doubt an occasional mass of Cannas, etc., might prove effective—in a distant prospect especially—but the thing is repeated ad nauseam.

The fact is, we do not want purely “Subtropical gardens,” or “Leaf gardens,” or “Colour gardens,”{15} but such gardens as, by happy combinations of the materials at our disposal, shall go far to satisfy those in whom true taste has been awakened—and, indeed, all classes. For it is quite a mistake to assume that because people, ignorant of the inexhaustible stores of the vegetable kingdom, admire the showy glares of colour now so often seen in our gardens, they are incapable of enjoying scenes displaying some traces of natural beauty and variety.

The fine-leaved plants have not yet been associated immediately with the flowers; hence the chief fault. Till they are so treated we can hardly see the great use of such in ornamental gardening. Why not take some of the handsomest plants of the medium-sized kinds, place them in the centre of a bed, and then surround them with the gaily-flowering subjects? The Castor-oil plants would not do so well for this, because they are rampant growers in fair seasons, but the Yuccas, Cannas, Wigandias, and small neat Palms and Cycads would suit exactly. Avoid huge, unmeaning masses, and associate more intimately the fine-leaved plants with the brilliant flowers. A quiet mass of green might be desirable in some positions, but even that could be varied most effectively as regards form.{16} The combinations of this kind that may be made are innumerable, and there is no reason why our beds should not be as graceful as bouquets well and simply made.

However, it is not only by making combinations of the subtropical plants with the gay-flowering ones now seen in our flower-gardens that a beautiful effect may be obtained, but also with those of a somewhat different type. Take, for instance, the stately hollyhock, sometimes grown in such formal plantations as to lose some of its charms, and usually stiff and poor below the flowers. It is easy to imagine how much better a group of these would appear if seen surrounded by a graceful ring of Cannas, or any other tall and vigorous subjects, than they have ever yet appeared in our gardens.

Consider, again, the Lilies, from the superb, tall, and double varieties of the brilliant Tiger lily to the fair White lily or the popular L. auratum. Why, a few isolated heads of Fortune’s Tiger lily, rising like candelabra above a group of Cannas, would form one of the most brilliant pictures ever seen in a garden. Then, to descend from a very tall to a very dwarf lily, the large and white trumpet-like flowers of L. longiflorum would look superb, emerging from the outer margin of a mass of{17}

subtropical plants, relieved by the rich green within; and anybody, with even a slight knowledge of the lily family, may imagine many other combinations equally beautiful and new. The bulbs would of course require planting in the autumn, and might be left in their places for several years at a time, whereas the subtropical plants might be those that require planting every year; but as the effect is obtained by using comparatively few lilies, the{18} spaces between them would be so large, as to leave plenty of room to plant the others. However, it is worth bearing in mind, that most of the Cannas, by far the finest group of “Subtropical” plants for the British Isles, remain through the winter in beds in the open air protected by litter: hence, permanent combinations of Lilies and Cannas are perfectly practicable.

Then, again, we have those brilliant and graceful hosts of Gladioli, that do not show their full beauty in the florist’s stand or in his formal bed, but when they spring here and there, in an isolated manner, from rich foliage, entirely unlike their own pointed sword-like blades. Next may be named the flame-flowered Tritoma, itself almost subtropical in foliage when well grown. Any of the Tritomas furnish a splendid effect grouped near or closely associated with subtropical plants. The lavishly blooming and tropical-looking Dahlia is a host in itself, varying so much as it does from the most gorgeous to the most delicate hues, and differing greatly too in the size of the flowers, from those of the pretty fancy Dahlias to the largest exhibition kinds. Combinations of Dahlias with Cannas and other free-growing subtropical plants have a most satisfactory effect; and where beds or groups are{19} formed of hardy subjects (Acanthuses and the like), in quiet half-shady spots, some of the more beautiful spotted and white varieties of our own stately and graceful Foxglove would be charmingly effective. In similar positions a great Mullein (Verbascum) here and there would also suit; while such bold herbaceous genera as Iris, Aster (the tall perennial kinds), the perennial Lupin, Baptisias, Thermopsis, Delphiniums, tall Veronicas, Aconites, tall Campanulas, Papaver bracteatum, Achillea filipendula, Eupatoriums, tall Phloxes, Vernonias, Leptandra, etc., might be used effectively in various positions, associated with groups of hardy subjects. For those put out in early summer, summer and autumn-flowering things should be chosen.

The tall and graceful Sparaxis pulcherrima would look exquisite leaning forth from masses of rich foliage about a yard high; the common and the double perennial Sunflower (Helianthus multiflorus, fl. pl.) would serve in rougher parts, where admired; in sheltered dells the large and hardy varieties of Crinum capense would look very tropical and beautiful if planted in rich moist ground; and the Fuchsia would afford very efficient aid in mild districts, where it is little injured in winter, and where, consequently, tall{20} specimens flower throughout the summer months; and lastly, the many varied and magnificent varieties of herbaceous Peony, raised during recent years, would prove admirable as isolated specimens on the grass near groups of fine-foliaged plants. Then again we have the fine Japan Anemones, white and rose, the showy and vigorous Rudbeckias, the sweet and large annual Datura ceratocaula, the profusely-flowering Statice latifolia, the Gaillardias, the Peas (everlasting and otherwise), the ever-welcome African Lily (Calla), the handsome Loosestrife (Lythrum roseum superbum), and the still handsomer French Willow, and not a few other things which need not be enumerated here, inasmuch as it is hoped enough has been said to show our great and unused resources for adding real grace and interest to our gardens. This phase of the subject—the association of tall or bold flowers with foliage-plants—is so important, that I have bestowed some pains in selecting the many and various subjects useful for it from almost every class of plants; and they will be found in a list at the end of the alphabetical arrangement.

Many charming results may be obtained by carpeting the ground beneath masses of tender{21} subtropical plants with quick-growing ornamental annuals and bedding plants, which will bloom before the larger subjects have put forth their strength and beauty of leaf. If all interested in flower-gardening had an opportunity of seeing the charming effects produced by judiciously intermingling fine-leaved plants with brilliant flowers, there would be an immediate revolution in our flower-gardening, and verdant grace and beauty of form would be introduced, and all the brilliancy of colour that could be desired might be seen at the same time. Here is a bed of Erythrinas not yet in flower: but what affords that brilliant and singular mass of colour beneath them? Simply a mixture of the lighter varieties of Lobelia speciosa with variously coloured and brilliant Portulacas. The beautiful surfacings that may thus be made with annual, biennial, or ordinary bedding plants, from Mignonette to Petunias and Nierembergias, are almost innumerable.

Reflect for a moment how consistent is all this with the best gardening and the purest taste. The bare earth is covered quickly with these free-growing dwarfs; there is an immediate and a charming contrast between the dwarf-flowering and the fine-foliaged plants; and should the last{22} at any time put their heads too high for the more valuable things above them, they can be cut in for a second bloom. In the case of using foliage-plants that are eventually to cover the bed completely, annuals may be sown, and they in many cases will pass out of bloom and may be cleared away just as the large leaves begin to cover the ground. Where this is not the case, but the larger plants are placed thin enough to always allow of the lower ones being seen, two or even more kinds of dwarf plants may be employed, so that the one may succeed the other, and that there may be a mingling of bloom. It may be thought that this kind of mixture would interfere with what is called the unity of effect that we attempt to attain in our flower-gardens. This need not be so by any means; the system could be used effectively in the most formal of gardens.

One of the most useful and natural ways of diversifying a garden, and one that we rarely or never take advantage of, consists in placing really distinct and handsome plants alone upon the grass, to break the monotony of clump margins and of everything else. To follow this plan is necessary wherever great variety and the highest beauty are desired in the ornamental garden. Plants may be{23}

placed singly or in open groups near the margins of a bold clump of shrubs or in the open grass; and the system is applicable to all kinds of hardy ornamental subjects, from trees downwards, though in our case the want is for the fine-leaved plants and the more distinct hardy subjects. Nothing, for instance, can look better than a well-developed tuft of the broad-leaved Acanthus latifolius, springing from the turf not far from the margin of a pleasure-ground walk; and the same is true of the Yuccas, Tritomas, and other things of like character and hardiness. We may make attractive groups of one family, as the hardiest Yuccas; or splendid groups of one species like the Pampas grass—not by any means repeating the individual, for there are about twenty varieties of this plant known on the Continent, and from these half a dozen really distinct and charming kinds might be selected to form a group. The same applies to the Tritomas, which we usually manage to drill into straight lines; in an isolated group in a verdant glade they are seen for the first time to best advantage: and what might not be{24} done with these and the like by making mixed groups, or letting each plant stand distinct upon the grass, perfectly isolated in its beauty!

Let us again try to illustrate the idea simply. Take an important spot in a pleasure-ground—a sweep of grass in face of a shrubbery—and see what can be done with it by means of these isolated plants. If, instead of leaving it in the bald state in which it is often found, we place distinct things isolated here and there upon the grass, the margin of shrubbery will be quite softened, and a new and charming feature added to the garden. If one who knew many plants were arranging them in this way, and had a large stock to select from, he might produce numberless fine effects. In the case of the smaller things, such as the Yucca and variegated Arundo, groups of four or five good plants should be used to form one mass, and everything should be perfectly distinct and isolated, so that a person could freely move about amongst the plants without touching them. In addition to such arrangements, two or three individuals of a species might be placed here and there upon the grass with the best effect. For example, there is at present in our nurseries a great Japanese Polygonum (P. Sieboldi), which has never as yet{25} been used with much effect in the garden. If anybody will select some open grassy spot in a pleasure-garden, or grassy glade near a wood—some spot considered unworthy of attention as regards ornamenting it—and plant a group of three plants of this Polygonum, leaving fifteen feet or so between the stools, a distinct aspect of vegetation will be the result. The plant is herbaceous, and will spring up every year to a height of from six feet to eight feet if planted well; it has a graceful arching habit in the upper branches, and is covered with a profusion of small bunches of pale flowers in autumn. It is needless to multiply examples; the plan is capable of infinite variation, and on that account alone should be welcome to all true gardeners.

One kind of arrangement needs to be particularly guarded against—the geometro-picturesque one, seen in some parts of the London parks devoted to subtropical gardening. The plants are very often{26} of the finest kinds and in the most robust health, all the materials for the best results are abundant, and yet the scene fails to satisfy the eye, from the needless formality of many of the beds, produced by the heaping together of a great number of species of one kind in long straight or twisting masses with high raised edges frequently of hard-beaten soil. Many people will not see their way to obliterate the formality of the beds, but assuredly we need not do so to get rid of such effective formality as that shown in the accompanying figure!

The formality of the true geometrical garden is charming to many to whom this style is offensive; and there is not the slightest reason why the most beautiful combinations of fine-leaved and fine-flowered plants should not be made in any kind of geometrical garden.

But in the purely picturesque garden it is as{27} needless, as it is in false taste, to follow the course here pointed out. Hardy plants may be isolated on the turf, and may be arranged in beautiful irregular groups, with the turf also for a carpet, or some graceful spray of hardy trailing plants. Beds may be readily placed so that no such objectionable stage-like results will be seen as those shown in the preceding figure: tender plants may be grouped as freely as may be desired—a formal edge avoided by the turf being allowed to play irregularly under and along the margins, while the remaining bare ground beneath the tall plants may be quickly covered with some fast-growing annuals like Mignonette or Nolanas, some soft-spreading bedding plants like Lobelias or Petunias, or subjects still more peculiarly suited for this purpose, such as the common Lycopodium denticulatum and Tradescantia discolor. Choice tender specimens of Tree ferns, etc., placed in dark shady dells, may be plunged to the rims of the pots in the turf or earth, and some graceful or bold trailing herb placed round the cavity so as to conceal it; and in this way such results may be attained as those indicated in the first plate, in those showing the Dimorphanthus, Musa Ensete, and in the frontispiece. The day will come when{28} we shall be as anxious to avoid all formal twirlings in our gardens as we now are to have them perpetrated in them by landscape-gardeners of great repute for applying wall-paper or fire-shovel patterns to the surface of the reluctant earth, and when we shall no more think of tolerating in a garden such a scene as that shown in the preceding figure, than a landscape artist would tolerate it in a picture.

The old landscape-gardening dogma, which tells us we cannot have all the wild beauty of nature in our gardens, and may as well resign ourselves to the compass, and the level, and the defined daub of colour and pudding-like heaps of shrubs, had some faint force when our materials for gardening were few,[A] but considering our present rich and, to a great extent, unused stores from every clime, and from almost every important section of the vegetable kingdom, it is demonstrably false and foolish.

[A] “In gardening, the materials of the scene are few, and those few unwieldy, and the artist must often content himself with the reflection that he has given the best disposition in his power to the scanty and intractable materials of nature.”—Allison.

To these observations on arrangement, etc., one good rule may be added:—Make your garden as distinct as possible from those of your{29}

neighbours—which by no means necessitates a departure from the rules of good taste.

I wish particularly to call attention to the fine effects which may be secured, from the simplest and most easily obtained materials, by using some of our hardy trees and shrubs in the subtropical garden. Our object generally is to secure large and handsome types of leaves; and for this purpose we usually place in the open air young plants of exotic trees, taking them in again in autumn; and, perhaps, as we never see them but in a diminutive state, we often forget that, when branched into a large head in their native countries, they are not a whit more remarkable in foliage than many of the trees of our pleasure-grounds. Thus, if the well-known Paulownia imperialis were too tender to stand our winters, and if we were accustomed to see it only in a young and simple-stemmed condition and with large leaves, we should doubtless plant it out every summer as we do the Ferdinanda. There is no occasion whatever to resort to exotic subjects, while we can so easily obtain fine hardy subjects—which, moreover, may be grown by everybody and everywhere. By annually cutting down young plants of various hardy trees and shrubs, and letting them make a clean,{30} simple-stemmed growth every year, we will, as a rule, obtain finer effects than can be got from tender ones. The Ailantus, for example, treated in this way, gives us as fine a type of pinnate leaf as can be desired. Nobody need place Astrapæa Wallichii in the open air, as I have seen done, so long as a simple-stemmed young plant of the Paulownia makes such a column of magnificent leaves. The delicately-cut leaves of the Gleditschias, borne on strong young stems, would be as pretty as those of any fern; and so in the case of various other hardy trees and shrubs. Persons in the coldest and least favourable parts of the country need not doubt of being able to obtain as fine types of foliage as they can desire, by selecting a dozen kinds of hardy trees and treating them in this way. What may be done in this way, in one case, is shown in the accompanying plate, representing a young plant of Ailantus, with its current year’s shoot and leaves, standing gracefully in the midst of a bed of Cannas.

A few words may now be added about some types of vegetation which, though not included among what are commonly termed subtropical plants, may yet be judiciously used in combination with them, and go far to produce very charming effects.{31}

Among conifers we find many subjects of the most exquisite grace, and of a beautiful free and pointed habit, which it is most desirable we should have associated with vegetation more distinguished for brilliancy than grace. They are in many cases as elegantly chiselled and dissected as the finest fern, and it is difficult to find more beautiful masses of verdure than such plants as Retinospora plumosa and R. obtusa display when well developed; they are simply invaluable for those who use them with taste. Apart altogether from our want of a more elegantly diversified surface in the flower-garden—the best and most practical way to meet which is by the use of such plants as these and neat and elegant young specimens of such things as Thujopsis borealis—there is, in many British gardens, a great gulf between the larger tree and shrub vegetation and the humbler colouring material, which most will admit should be filled up, and there is nothing more suitable for it than the many graceful conifers we now possess. Much as conifers are grown with us, how few people have any idea of their great value as ornamental plants for the very choicest position in a garden! We are sometimes too apt to put them in what is called their “proper place,”—or, at all events, too far from the seat of{32} interest to thoroughly enjoy them in winter, when the beauty of their form and their exquisite verdure are best seen. If the dwarfer and choicer conifers were tastefully disposed in and immediately around a flower-garden not altogether spoiled by a profusion of beds for masses of colour, that flower-garden could hardly fail to look as well in winter as in summer; in fact I have seen places where, from rather close association of the more elegant types, the best kind of winter garden was made. Our efforts must tend to prevent a desert-like aspect at any time of the year; and to this end nothing can help us more than a judicious selection of conifers. Almost every beauty of form is theirs. They possess a permanent dignity and interest, always occupying the ground and embellishing it, displaying distinct tints of ever-grateful green in spring and summer, waving majestically before the gusts of autumn, and beautiful when bearing on their deepest green the snows of winter. Some of the more suitable kinds are named in a list at the end of this book, but the graceful pines are so commonly grown that few will have any difficulty in securing proper sorts.

The Gourd tribe is capable, if properly used, of adding much remarkable beauty and character to{33}

the garden; yet, as a rule, it is seldom used. There is no natural order more wonderful in the variety and singular shapes of its fruit than that to which the melon, cucumber, and vegetable marrow belong. From the writhing Snake-cucumber, which hangs down four or five feet long from its stem, to the round enormous giant pumpkin or gourd, the grotesque variation, both in colour and shape and size, is marvellous. There are some pretty little gourds which do not weigh more than half an ounce when ripe; while, on the other hand, there are kinds with fruit almost large enough to make a sponge bath. Eggs, bottles, gooseberries, clubs, caskets, folded umbrellas, balls, vases, urns, small balloons,—all have their likenesses in the gourd family. Those who have seen a good collection of them will be able to understand Nathaniel Hawthorne’s enthusiasm about these quaint and graceful vegetable forms when he says: “A hundred gourds in my garden were worthy, in my eyes at least, of being rendered indestructible in marble. If ever Providence (but I know it never will) should assign me a superfluity of gold, part of it shall be expended for a service of plate, or most delicate porcelain, to be wrought into the shape of gourds gathered{34} from vines which I will plant with my own hands. As dishes for containing vegetables they would be peculiarly appropriate. Gazing at them, I felt that by my agency something worth living for had been done. A new substance was born into the world. They were real and tangible existences, which the mind could seize hold of and rejoice in.” Of course the climate of New England is much better suited for fully developing the gourd tribe than ours, but it is satisfactory to know that they may be readily and beautifully grown in this country.

There are many positions in gardens in which they might be grown with great advantage; on low trellises, depending from the edges of raised beds, the smaller and medium-sized kinds trained over arches or arched trellis-work, covering banks, or on the ordinary level earth of the garden. Isolated, too, some kinds would look very effective, and in fact there is hardly any limit to the uses to which they might be applied. In the Royal Botanic{35} Gardens at Dublin, there is a singular wigwam made by placing a number of dead branches so as to form the framework, and then planting Aristolochia Sipho all round these. It runs over them, and the large leaves make a perfect summer roof. A similar tent might be made with the free-growing gourds, and it would have the additional merit of suspending some of the most singular, graceful, and gigantic of all known fruits from the roof. A few words on their culture, and a selection of kinds, occur at the end of the book.

Although some Ferns are named in the descriptive part of this book, it is desirable to allude to the family here. Why do we always put ferns in the shade, when many of the best and hardiest kinds grow freely in the full sun if sufficiently moist at the root? Why do we always confine them to the fernery proper, when there are so many other places that could be graced by their presence? The very highest beauty of form might be added to beds of low flowers, by the introduction of such ferns as the Struthiopteris, Pteris, Lastrea, etc., while they should also be freely planted in various parts of the pleasure-ground, either alone, or grouped with the Acanthuses and other hardy fine-leaved plants. Not a few of the{36} Umbelliferous plants recommended have foliage as finely cut as any of the Ferns, and would associate very well with them. Even in cases where the soil might not be suitable for ferns, it would, instead of confining them to the fernery proper, be much better to arrange for having small groups or beds of them in places alongside of shady wood-walks or similar positions. By reference to the Osmunda article, it will be seen how these have been grown to magnificent proportions. It may be easily imagined that groups of fine ferns, grown to the luxuriance there described, would contrast with and relieve groups of the brilliant flowers in a superb way.

As the culture of most of the subjects has been sufficiently spoken of in the descriptive part, it is needless to say much of it here, but a few general remarks may help to make the matter clearer to the amateur. It is hoped that the greater number of the hardy subjects enumerated will sufficiently prove that it is not only those persons who have streets of glass-houses to whom the luxury of “subtropical gardening” is accessible. Once placed in suitable soil and position, these hardy kinds may, as a rule, be left to take care of themselves.

A great number of subjects, like the Ricinus{37} and the Annuals, may be considered practically hardy, inasmuch as they only require to be raised in warm or cool frames, or even (some of them) in the open air. When once planted out for the summer, they give but little further trouble.

In the next group may be placed the tender greenhouse kinds; long-lived subjects, like the Dracænas, American Aloe, etc., which thrive in greenhouses or conservatories in winter, and are great ornaments there, and which may be placed in the open air in summer without the least injury. Next to the hardy group, this is the most important, from the fact that the subjects are effective at all seasons of the year, and useful indoors as well as without. They also, unlike the following, may be enjoyed by every one who possesses any kind of a cool glazed structure; and even, in some cases, this is not needed, for I have seen some very fine specimens of Agave americana kept in a large entrance hall in winter, and put out of doors in May to be taken in again in October.

Lastly, we have the least important group of all, and happily also the most costly, viz., those plants which must be kept through the winter and spring in warm stoves, such as Ferdinanda, Solanum, etc. Considering the vast number of hardy and half-hardy{38} plants from which we may select, this type is not worthy of encouragement in gardens generally, with the exception of a few fine things, such as Polymnia grandis. They may, for the sake of convenience, be considered in two sections: those, like the Polymnia, that should be put out in a young state, and which make a fresh and handsome growth during the summer months; and those which, like the Monstera and Anthurium acaule, make no growth whatever during that season. It need not be said that the first section is by far the most important: it comprises the Wigandia, and some of the noblest things used in this way. Plants of the other section can, in the nature of things, be tried in but few places in this country; they are too expensive, and they are not the most effective: but some persons no doubt may take a pleasure in showing what will endure the open air, even if useless for any other purpose. One general rule may be applied to these last-named subjects—they should be allowed to make a strong growth in the hothouse in spring or early summer, and to mature, and, so to speak, harden off that growth before being placed in the open air early in June, or even later if the season be unfavourable.

Speaking generally of all the tender subjects{39} used, it is necessary to discriminate between kinds that should be planted out in a young state every year, and those which are valuable in proportion to their age and size. Some plants are all the better the higher and larger they are grown; others must be started in a dwarf fresh state every year, or, if not, their foliage will not possess that pristine freshness which charms us when they are properly treated. A large plant of Polymnia grandis, for example, would, if placed in the open air in early summer, speedily become a far from attractive object, while a young plant of the same kind, put out on the same day, would soon produce and carry to the end of the season a mass of fresh and noble leaves. But of course this only applies to kinds that grow rapidly during the summer months in our climate.

With respect to the preparation of the beds for the finer subtropical plants, a peculiar mode is practised in Battersea Park. Here many of the beds are raised above the level of the ground, and underneath and around the mass of light rich soil is a good layer of brick-rubbish, as shown in the accompanying engraving. The soil is first excavated and thrown round the margin of the bed; then the brick-rubbish is put in on the bottom and{40}

around the sides also, raising the bed somewhat above the level of the ground; the cavity in the centre is then filled up, generally with fine light rich soil, using as much of the soil that was dug out as is fit to be used, and arranging the remainder round the edge of the raised bed, covering it neatly with turf. The soil may vary in depth from three feet to eighteen inches, according to the kinds of plants to be grown in it. In this way, by presenting a larger surface to the sun, it is considered that a greater amount of heat is obtained; but I certainly think the advantages of the method are not so great in this way as is generally supposed, and that it is quite needless to adopt it in the case of the great majority of subjects. Its chief merit probably is that it secures a better drainage. Good drainage is undoubtedly indispensable, and,{41} still more so, a thoroughly rich and light mass of deep soil, with abundance of water; without these two last conditions it is hopeless to expect a free rich growth, which is the great charm of these plants. Ricinus, Cannas, Ferdinanda, and some of the freer-growing kinds certainly succeed perfectly without any such arrangement as that above described. The more delicate kinds, such as the Solanums and Wigandia macrophylla, would be those most likely to be benefited by it. It is needless to say, that the numerous fine and hardy subjects enumerated in Part II. do not require anything of the kind, although they too will, as a rule, be fine in proportion to the care bestowed in securing for them a deep and rich body of soil.

One most essential matter is the securing of as perfect shelter as is possible. Warm, sunny, and thoroughly sheltered dells should be chosen where convenient; and, in any case, positions which are sheltered should be selected, as the leaves of all the better kinds suffer very much from strong winds, from which they will be protected if judiciously planted near sheltering banks and trees. Even in quite level districts it will be possible to secure shelter, by planting trees of various kinds, among which such graceful conifers as Thujopsis{42} borealis, Thuja gigantea (true), Cupressus macrocarpa, Cryptomeria elegans, etc., should be freely used in the foreground, as in beauty of form they are unsurpassed by any short-lived inhabitants of the summer garden. Except, however, in the case of the Tree-ferns, and various other things not grown in the open air but simply placed there for the summer, it is very desirable not to place the plants in the shade of trees. All the things which have to grow in the open air should be placed in the full sun. Not a few hardy subjects will thrive very well without any but ordinary shelter, as, for example, the Yuccas and Acanthuses; but, judging by the remarkable way in which the hardy Bamboo thrives when placed in a sheltered dell, shelter has a considerable influence on the well-being even of these, as it must have on all subjects with large leaf-surfaces. But it should not be forgotten that shelter may be well secured without placing the beds or groups so near trees that they will be robbed, shaded, or otherwise injured by them.

W. R.

![]()

DESCRIPTION, ARRANGEMENT, CULTURE, ETC., OF SUITABLE SPECIES, HARDY AND TENDER, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED.

SUBTROPICAL GARDENING.

PART II.

![]()

[*]Acacia Julibrissin.—A native of Persia, with large and elegant much-divided leaves, and flowers somewhat like short tinted brushes from the numerous purple stamens. Though this does not succeed as a standard tree in all parts of England (where it grows well against walls, and sometimes flowers), yet doubtless it would do so in some parts of the south, and I have seen it make presentable standards about Geneva and in Anjou. But for our purposes it is better that it should not be perfectly hardy, as by confining it to a single young stem and using young plants, or plants that have been cut down every year, we shall get an erect stem covered with leaves more graceful than a fern, and that is the kind of ornament we want as a graceful object amidst low-growing flowers. The leaves, like those of some other plants of the pea tribe, are slightly sensitive. On fine sunny days they spread out fully and afford a pleasant shade; on dull ones the leaflets fall down. This interesting phenomenon takes place with other members of the same family—for instance, the elegant A. dealbata of{46} our conservatories. Seed of A. Julibrissin—or the silk-rose, as it is called by the Persians in consequence of its silky stamens—is readily obtained, and it is much better raised from seed, as then you get those single-stemmed and vigorous young plants which are to the flower-garden what an elegant fern is to the conservatory or show-house. To succeed with it in the way above named, it may be protected at the root and cut down every year in spring, or strong young plants may be put out annually, in much the same way as those of A. lophantha.

[*] The names of all hardy species and other kinds easily raised from seed in spring (the kinds useful in all classes of garden), are preceded by an asterisk.

Acacia lophantha.—This elegant plant, though not hardy, is one of those which all may enjoy, from the freedom with which it grows in the open air in summer. It will prove more useful for the flower-garden than it has ever been for the houses, and, being easily raised, is entitled to a place here among the very best. The elegance of its leaves and its quick growth in the open air make it quite a boon to the flower-gardener who wishes to establish graceful verdure amongst the brighter ornaments of his parterre. It has graceful fern-like leaves and a close and erect habit, which permits us to closely associate it with flowering plants without in the least shading them or robbing them. Of course I speak of it in the young and single-stemmed condition, the way in which it should be used. By confining it to a single stem and using it in a young state, you get the fullest size and grace of which the leaves are capable. Allow it to become old and branched, and it may be useful, but by no means so much so as when young and without side branches. It may be raised from seed as easily as a common bedding plant. By sowing it early{47}

in the year it may be had fit for use by the first of June; but plants a year old or so, stiff, strong, and well hardened off for planting out at the end of May, are the best. It would be desirable to raise an annual stock, as it is almost as useful for room-decoration as for the garden. Native of New Holland.

These stout and hardy herbaceous plants are of the greatest importance in the subtropical garden or the pleasure-ground, their effect being very good when they are well established. They thrive in almost any soil, but attain their greatest luxuriance and beauty in deep warm ones. The best uses for these species are as isolated tufts in the grass, in the mixed border, or in picturesque groups with other hardy subjects. In all cases they should be placed in positions where they are not likely to be disturbed, as their beauty is not seen until they are well established. All are easily propagated by division. Few herbaceous genera may be made more useful than this.

*Acanthus hirsutus.—This uncommon species has a narrow spiny leaf, more in the way of Morina longifolia than the ordinary Acanthuses, and is dark green in hue. The leaves grow to a length of about 15 ins. or 16 ins. in ordinary soil. Being distinct, it may be worth growing, though in point of character or importance it is inferior to the larger kinds. South of Europe.

*Acanthus latifolius.—The leaves of this are bold and noble in outline, and the plant has a tendency, rare{48} in some hardy things with otherwise fine qualities, to retain them till the end of the season without losing a particle of their freshness and polished verdure. In fact, the only thing we have to decide about this subject is, what is the best place for it? Now, it is one of those things that will not disgrace any position, and will prove equally at home in the centre of the mixed border, projected in the grass a little from the edge of a choice shrubbery, or in the flower-garden; nobody need fear its displaying anything like the seediness which such things as the Heracleums show at the end of summer. I should not like to advise its being planted in the centre of a flower-bed, or in any other position where it would be disturbed; but in case it were determined to plant permanent groups of fine-leaved hardy plants, then indeed it could be used with great success. Supposing we have an irregular kind of flower-garden or pleasure-ground to deal with (a common case), one of the best things to do with this Acanthus is to plant it in the grass, at some distance from the clumps, and perhaps near a few other things of like character. It is better than any kind of Acanthus hitherto commonly cultivated, though one or two of these are fine. Give it deep good soil, and do not grudge it this attention, because, unlike tender plants, it will not trouble you again for a long time. Nobody seems to know from whence it came. Probably it is a variety of Acanthus mollis. The plant varies a good deal; I have seen specimens of it about a foot high, with leaves comparatively small and stiff and rigid, as if cast in a mould, by the side of others of thrice that development, and of the usual texture.{49}

*Acanthus longifolius.—A fine, distinct, and new species from Dalmatia and S. Europe, 3½ ft. to 4 ft. high, distinguished from A. mollis (to which it is allied) by the length and narrowness of its arching leaves. They are about 2½ ft. long, very numerous, of a bright green colour, growing at first erect, then inclining and forming a sheaf-like tuft, which has a very fine effect. The flowers are of a wine-red colour, becoming lighter before they fall. A specimen in the gardens of the Museum at Paris, in four years after planting, had twenty-five blooming-stems rising from the midst of a round mass of verdure nearly 2½ ft. in height and width. This would be very effective on the undulating and picturesque parts of landscape-gardens. It does not run so much at the root as A. mollis. It seeds more freely than the other kinds, and may be readily increased by seeds as well as by division. Its free-flowering quality makes this species peculiarly valuable, while it is as good as any for isolation or grouping.

*Acanthus mollis.—A well-known old border-plant from the south of Europe, about 3 ft. high, with leaves nearly 2 ft. long by 1 ft. broad, heart-shaped in outline, and cut into angular toothed lobes. The flowers are white or lilac, the inflorescence forming a remarkable-looking spike, half the length of the stem. Well adapted for borders, isolation, margins of shrubberies, and semi-wild places, in deep ordinary soil, the richer the better. Increased by division of the roots in winter or early spring.

*Acanthus spinosissimus.—This is in all respects among the finest of thoroughly hardy “foliage-plants,”{50} growing to a height of 3½ ft., and bearing rosy-flesh-coloured flowers in spikes of a foot or more in length. It is perfectly hardy, very free in growth, and is quite distinct from any of the other species, forming roundish masses of dark-green leaves, with rather a profusion of glistening spines, by which it is known immediately from its relatives. As a permanent object, fit to plant in a nook in the pleasure-ground or on the grass, associated with the nobler grasses or other plants, there is nothing to surpass it. I know of no hardy foliage-plant so thoroughly neat in its habit at all times. It does not often flower; and if it should throw up a spike, it will perhaps be no loss to cut it off, as its leaves are its best ornament, though the flowers too are interesting. Never at any time does it require the least attention; it will stand any exposure; and is, in a word, invaluable as a hardy ornamental plant. It will thrive best in good and deep soil. South of Europe.

*Acanthus spinosus.—This species appears to flower well more regularly than any other. Its leaves are rather narrow, and very deeply divided into almost triangular segments: they are also covered with short spines. The flowering-stems are about 3 ft. high, and bear dense spikes of purplish flowers. Useful for borders, or grouping with the other kinds and plants of similar character and size. South of Europe.

*Adiantum pedatum.—This fern, which abounds in the woods of Canada and the United States, is unquestionably one of the most elegant of those which are able to endure the climate of Britain, and grows from 16 ins. to 20 ins. high. From the tops of the erect black stems{51} the fronds branch and spread horizontally in a very graceful and peculiar manner. The leaflets are slightly wedge-shaped, the upper margin resembling an arc of a circle. The American Maiden-hair flourishes in a light cool soil, and in a half-shaded position, or in a coarsely-broken, shallow, turfy peat soil, covered with a layer of moss to keep it constantly cool. It is commonly grown in the greenhouse with us, but is especially adapted for embellishing the low and shady parts of rockwork, and for ornamenting beds and mounds of peaty soil which have a north aspect or are sheltered from the full sun. It is propagated by division of the tufts in autumn or early spring. If done in autumn, the divisions should be potted and placed under a frame for the winter, as they form new roots more readily if so treated. There can be no question that, if planted in rich moist soil in a shady wood, we should have no trouble in naturalising this graceful fern, the fronds of which are such graceful objects in the dense woods of the “great country.”

Agave americana.—This and its variegated varieties are plants peculiarly suited for subtropical gardening, being useful for placing out of doors in summer in vases, tubs, or pots plunged in the ground, and also for the conservatory in winter. It forms a large rosette of thick fleshy leaves of a glaucous ashy-green colour, overlapping each other at the base, from 4 ft. to 6½ ft. long, and from 6 ins. to 10 ins. broad, ending in a strong spine, and having numerous spines along the margin. When the plant flowers, which it does only once, and after several years’ growth, it sends up a flowering-stem{52} from 26 ft. to nearly 40 ft. high. The flowers are of a yellowish-green colour, and are very numerous on the ends of the chandelier-like branches. It will grow in any moderately dry greenhouse or conservatory in winter, or even in a large hall, and may be placed out of doors at the end of May and brought in in October. All the varieties are easily increased from suckers. N. America.

*Agrostis nebulosa.—This beautiful annual grass forms most delicate feathery tufts about 1 ft. or 15 ins. in height, terminated when in flower by graceful panicles of spikelets, which are at first of a reddish-green colour, and afterwards change to a light red in the upper part, the remaining two-thirds being of a deep green: the pedicels are extremely slender and of a violet colour. It forms very handsome edgings, and is very valuable for bouquets, vases, baskets, room and table decoration, etc. If cut shortly before the seed ripens, and dried in the shade, it will keep for a long time. Dyed in various colours it is much used by makers of artificial flowers. It may be sown either in September or in April or May. In the former case it will flower from May to July, in the latter from July to September. The seed, being very fine, should be only slightly covered. Though small, this deserves a place in groups of the finer and dwarfer plants, such as Thalictrum minus, and also in herbaceous borders. Spain.

*Ailantus glandulosa.—Much trouble and expense are incurred in the purchase, growth, and protection of tender plants with fine compound leaves like this, but which in our climate never display anything like the fresh vigour, health, spotless appearance, and youthful{53} grace characteristic of hardy subjects. This is one of the most valuable of the hardy trees which, if kept in a dwarf state by being planted young and cut down annually, will furnish as good an effect as any tropical plant. The Ailantus should be kept in a young state, with a single stem clothed with its superb pinnate leaves; and we can readily keep it in this form by planting it young and cutting it down annually, taking care to prevent it from breaking into an irregular head, as then the symmetry of the leaf beauty becomes confused and is not at all so effective as when it is kept to a single stem. Vigorous young plants and suckers in good soil will produce handsome, arching, elegantly divided leaves 5 ft. and even 6 ft. long, not to be surpassed by those of any stove-plant. Under such treatment it could be grown conveniently to about from 4 ft. to 7 ft. high, and would thus do grandly for association with the larger class of garden flowers—Gladioli, Dahlias, and Hollyhocks, for example—while among Cannas and the like it will prove fine. The leaves are not liable to be attacked by insects—a good point in a plant used for the purpose I suggest—and they retain their healthy green till the first frosts in November, when they suddenly drop off. It is propagated with facility by cuttings of the roots, but is cheap in all nurseries. China and Japan.

*Aira pulchella.—One of the most ornamental grasses, with numerous hair-like stems, growing in light elegant tufts 6 ins. to 8 ins. high. It is useful for forming very handsome edgings, or for interspersing amongst plants in borders, or growing in vases or pots for room-decoration.{54} Its delicate panicles give an additional charm to the finest bouquets. May be sown either in September or in April. S. Europe.

*Alisma Plantago.—A native perennial water-plant, growing nearly 3 ft. high, and bearing a very handsome pyramidal panicle of rosy-white flowers from June to September. The leaves are oval-lance-shaped with a cordate base, and are borne nearly erect on long stalks for some distance above the surface of the water. A graceful object on the margins of ponds, lakes, etc., where a plant of it transferred from any place where it grows will soon increase.

Alsophila excelsa.—A noble tree-fern, native of Norfolk Island, where it attains a height of 40 ft., crowned with a magnificent circular crest of bipinnate fronds. These fronds or branches fall off every year, leaving an indentation in the trunk. It stands well in the open air in this country in shady, moist, and thoroughly well sheltered places. It should be put out at the end of May, and taken indoors at the end of September or early in October, and receive warm-greenhouse or temperate-house treatment in winter. The same remarks apply to A. australis, and probably others of the family will be found to thrive well in the open air when sufficiently plentiful to be tried in that position.

Among the common annuals of our gardens I know of none more in want of judicious use and appreciation than these. The few we grow are usually treated as rough{55} common annuals, and sown so thickly that they never attain half their true development, or never fulfil any of the graceful uses for which they are adapted. But the family possesses greater claims on our attention by reason of the more recent additions to it. The old “Love lies bleeding” (A. caudatus), with its dark-red pendent racemes, is a very striking object when well grown, but A. speciosus and some of the more recent varieties are still more so.

*Amarantus caudatus.—A hardy and vigorous-growing species, from 2 ft. to 3¼ ft. high. Flowers from July to September, dark purplish, very small, collected in numerous whorls, which are disposed in drooping spikes so as to form a handsome pendent panicle. There is a variety which has yellow flowers and is equally hardy. It is advisable to give this plant plenty of room to spread; otherwise much of its picturesque effect will be lost; and to use it in positions where its fine and peculiar habit may be seen to advantage,—as, for example, in large vases, edges of large beds of subtropical plants, or dotted among low-growing flowering plants. Although as easily raised as any common annual, it deserves to be properly thinned out, and each plant isolated in rich ground, so that it may attain its full size. E. Indies.

*Amarantus sanguineus.—Is distinguished by the blood-red colour of its leaves, and grows about 3 ft. high. Its purple flowers appear from July to October, disposed partly in small heads in the axils of the upper leaves, and partly in slender, flexible spikes which form a panicle more or less branching. This plant, though a native of the East Indies, is quite hardy, and seems to{56} do best in light soil with plenty of leaf-mould and having a warm aspect. It may be sown in hotbeds in April and pricked out in May, or in the open air at the end of April or beginning of May, and, like the others, should never be allowed to get crowded.

*Amarantus speciosus.—A very large kind, well adapted for associating with subtropical plants, as it grows from 3 ft. to nearly 5 ft. high. The flowers are very numerous, of a dark crimson purple, and arranged in large erect spikes, forming a fine plumy panicle. The leaves are suffused with a reddish tinge. Plants of this species are occasionally met with having leaves with a light green centre surrounded by wavy zones of a reddish hue. This colouring disappears at the time of flowering. It is an effective subject in the autumn months. Culture, the same as for the preceding kind. Nepaul.

*Amarantus tricolor.—Distinguished by the very handsome and remarkable colouring of its leaves, which are of a fine transparent purplish-red, or dark carmine, from the base to the middle. A large spot of lively transparent yellow occupies the greater part of the upper end of the leaf, and sometimes covers it altogether, with the exception of the point, which is mostly green. The leaf-stalk is either of a light green or yellow colour. Sometimes leaves occur which have the lower half green and the upper part red. Another variety (bicolor) has leaves of a tender green variously streaked with light yellow. It is rather delicate, and requires very good soil, and a warm, open aspect. Another variety (bicolor ruber) is hardier than the last-named, and has leaves which are of a brilliant glistening scarlet when young, gradually{57} changing to a dark violet-red mixed with green. Another variety (ruber) has a more squat and ramified habit, and leaves of a deep rose-colour thickly clothing the stems. Other varieties recommended are elegantissimus (with scarlet leaves), Gordoni, melancholicus ruber, and versicolor, all having some claims as bedding plants. The foliage of these varieties is exceedingly ornamental, and rivals the finest flowers in the richness of its hues. Planted along with large-leaved subjects, such as the Cannas, Wigandias, Ricinus, Solanums, etc., the effect is very fine. They may also be advantageously employed in borders and flower-beds of all sizes, and for fringing the edges of shrubberies. The varieties of A. tricolor are a little more tender than the other kinds, and a light soil and a warmer position are necessary for them. They do well in gardens by the seaside. They should be sown in April in a hotbed, pricked out in a hotbed, and finally planted permanently about the end of May. A. t. giganteus is described as very fine in recent catalogues of the nurserymen. To these may be added a beautiful new kind, A. salicifolius, in the possession of the Messrs. Veitch, but not yet sent out. It has highly coloured and very long, narrow, and arching leaves, and is a singularly graceful and brilliant object. E. Indies.

*Andropogon squarrosus is a hardy East Indian grass, which survives the winter with but slight protection, making luxuriant tufts seven feet high, or more, when in flower. It would probably make a beautiful object in the warmer and milder parts of England and Ireland in good soil, but it is not a subject which can with confidence be recommended for every garden. However, all{58} who value fine grasses should try it. Well-drained and deep-sandy loam.

This genus embraces many plants of very diverse aspects, and few that are fitted for the open air in our climate; but in the case of A. canescens, and its relative (A. spinosa), the Angelica-tree of North America, we have subjects which thrive perfectly well in our gardens, and which in the size and beauty of their leaves are far before many “foliage-plants” carefully cultivated in hothouses at a perpetual expense.

*Aralia canescens.—The specimen of this species figured was one of a batch of young plants growing in a London nursery, and sketched in the summer of 1868. The engraving falls far short of rendering the beauty of the plant. It is easy to imagine what a graceful effect may be realised by such an object, either isolated on the turf near the edge of a shrubbery, or grouped with subjects of similar character. Success with these plants may be secured by first selecting a sheltered and warm position, so that their noble leaves may be well developed and not lacerated by storms when they are fully grown; secondly, by giving them a deep, free, and thoroughly-drained soil; and thirdly, by confining them as a rule to a simple and rather dwarf stem, so that the vigour of the individual may not be wasted in several branches. The effect of a plant kept to a single stem, as shown in the plate, is always much superior to that of a branched one. Young plants present this aspect naturally; but old ones may be cut down,{59}

when they will shoot vigorously. If the effect of a full-grown specimen be desired, the shrubbery is the place for it. = A. japonica (Hort.).

*Aralia edulis.—This is a vigorous herbaceous perennial, well suited for those positions in which we desire a luxuriant type of vegetation. It is perfectly hardy, is of a fresh and vigorous habit, and grows 6, 7, and even 8 ft. high in good soil, even so early as the end of June. The leaves attain a length of nearly a yard when the plant is strong, while the shoots droop a little with their weight, and thus it acquires a slightly weeping character. It is rare in this country now, but, being easily propagated, may, it is to be hoped, not long prove so. As it dies down rather early in autumn, it must not be put in important groups, but rather in a position where its disappearance may not be noticed. An isolated position, or one near the margin of an irregular shrubbery, fernery, or rough rockwork by the side of a wood walk, will best suit it. Japan. Division.

*Aralia japonica.—A valuable species, quite distinct from any of the others, with undivided, fleshy, dark-green leaves. It is usually treated as a green-house plant, but is hardy and makes a very ornamental and distinct-looking shrub on soils with a dry porous bottom. It grows remarkably well in the dwelling-house; in fact it is one of the very few plants of like character that will develop their leaves therein in winter. Not difficult to obtain, it may be used with advantage in the flower-garden or pleasure-ground among medium-sized plants—say those not more than a yard high. It would form striking isolated specimens on the turf, and is also{60} very suitable for grouping. A native of Japan. = A. Sieboldi.

*Aralia nudicaulis.—A very vigorous perennial, with a smooth stem scarcely rising out of the ground, bearing large leaves with long-stalked, oval-oblong, pointed, toothed leaflets, and a shorter naked flower-stem, with from two to seven umbels of blossoms. Roots several feet long and highly aromatic. Similar uses to those directed for A. edulis. North America.

Aralia papyrifera (Chinese Rice-paper Plant).—This, though a native of the hot island of Formosa, flourishes vigorously with us in the summer months, and is one of the most valuable plants in its way, being useful for the greenhouse in winter and the flower-garden in summer. It is handsome in leaf and free in growth, though to do well it must, like all the large-leaved things,{61}