“The gold of that land is good.”—Gen. 2:12.

| I. | Jan. | 7. | Mother knows best | 7 |

| II. | ″ | 14. | Led into Sin—and out | 14 |

| III. | ″ | 21. | Naughty Dick | 21 |

| IV. | ″ | 28. | The Little Red House | 27 |

| V. | Feb. | 4. | “Dot” | 35 |

| VI. | ″ | 11. | Choosing a Master | 42 |

| VII. | ″ | 18. | Tod’s Stratagem | 50 |

| VIII. | ″ | 25. | The Helping Hand | 57 |

| IX. | March | 4. | Bell’s Bargain | 65 |

| X. | ″ | 11. | Walking with God | 72 |

| XI. | ″ | 18. | Brown-Haired Bess | 79 |

| XII. | ″ | 25. | Maybee’s Stepping-Stones | 81 |

| SECOND QUARTER. | ||||

| I. | April | 1. | Better than “a Rich Cousin.” | 91 |

| II. | ″ | 8. | Tryphosa | 99 |

| III. | ″ | 15. | Playing “Injuns” | 107 |

| IV. | ″ | 22. | Greedy Bell and Honest Bennie | 115 |

| V. | ″ | 29. | God’s Side the Strongest | 123 |

| VI. | May | 6. | Stronger than Papa | 131 |

| VII. | ″ | 13. | Real “Minding” | 133 |

| VIII. | ″ | 20. | And the Last, First | 139 |

| IX. | ″ | 27. | Phosy’s Work | 145 |

| X. | June | 3. | Phosy’s Hymn | 154 |

| XI. | ″ | 10. | Maybee’s Rebellion | 155 |

| XII. | ″ | 17. | “Because” | 163 |

| XIII. | ″ | 24. | Why Fred was Punished | 168 |

| THIRD QUARTER. | ||||

| I. | July | 1. | Farmer Vance | 170 |

| II. | ″ | 8. | Telling the Tidings | 177 |

| III. | ″ | 15. | Jesus’ Name | 184 |

| IV. | ″ | 22. | The Invitation | 190 |

| V. | ″ | 29. | Dick’s “Yoke” | 195 |

| VI. | Aug. | 5. | Maybee’s Pledge | 206 |

| VII. | ″ | 12. | The “New Song” | 216 |

| VIII. | ″ | 19. | The Wonderful Book | 223 |

| IX. | ″ | 26. | Aunty McFane’s Hymn | 230 |

| X. | Sept. | 2. | How to be Good | 232 |

| XI. | ″ | 9. | Bell’s Bible-reading | 240 |

| XII. | ″ | 16. | What Cousin Mate Said | 249 |

| XIII. | ″ | 23. | “Christ” or “Self” | 253 |

| XIV. | ″ | 30. | Miss Lomy’s Sermon | 256 |

| FOURTH QUARTER. | ||||

| I. | Oct. | 7. | How not to be Troubled | 264 |

| II. | ″ | 14. | Tod’s “Persecute” | 268 |

| III. | ″ | 21. | Will Carter | 276 |

| IV. | ″ | 28. | How Dick carried the Day | 283 |

| V. | Nov. | 4. | How Farmer Vance reasoned | 290 |

| VI. | ″ | 11. | Farmer Vance’s “Leading” | 297 |

| VII. | ″ | 18. | Almost Persuaded | 302 |

| VIII. | ″ | 25. | Needle Rock | 304 |

| IX. | Dec. | 2. | The Rescue | 312 |

| X. | ″ | 9. | Will’s Debt | 319 |

| XI. | ″ | 16. | Mr. Blackman | 324 |

| XII. | ″ | 23. | Maybee’s “Preach” and Practice | 329 |

| XIII. | ″ | 30. | Uncle Thed’s Christmas Plan | 340 |

“But he forsook the counsel of the old men, which they had given him.”

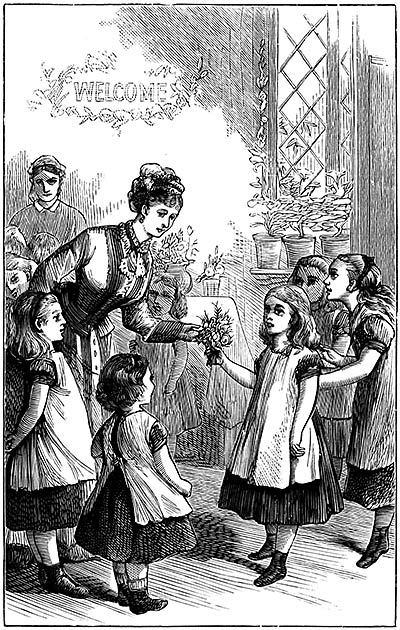

“Tod’s coming!” said Maybee, dancing up and down on the doorstep.

“How do you suppose they’ll behave?” said Sue, taking books, lunch-basket, and two clean pocket-handkerchiefs from mamma’s careful hands. “Tod is so queer; and what shall I do with Maybee’s tongue?”

“Do exactly as you would be done by,” said mamma, smoothing the anxious little forehead. “Remember, everything will be new and strange, and keep the wee things under your own wing as much as possible. Be very gentle and patient, help them over all the hard places, and my word for it, they will be your most obedient servants. I think Mabel means to be very good and quiet,” she added, stooping to kiss the dimpled chin on the doorstep.

“Yes’m, ’course,” nodded Maybee, skipping away to meet the freckle-faced Theodore, six months her junior. “On’y my ap’n’s so slippery it will rattle, and Tod’s got starch in his shoes, so’s he can’t go very sofferly.”

Sue took Tod’s other hand and walked on in her most matronly manner.

“Good-morning,” said Bell Forbush, coming out of her gate. “You look for all the world like a hen with two chickens. Don’t tell me those tots are going to school.”

“Why not? Maybee is six,” returned Sue, dignifiedly, “and Tod wants to go everywhere she does, so aunty said he might.”

“They’ll be such a bother, only, of course, you can leave them quite by themselves; they’ll get broken in all the sooner.”

“Mamma expects I’ll take care of them,” said Sue, dropping behind with Bell.

“Oh, fudge! Grown-up folks never seem to think we need any better fun than looking after such small fry, when really they ought to wait on us. In English schools they call them fags, and make them run errands and everything. Now, take my advice, Sue Sherman: put those young ones in a front seat, and just let them know who is who to begin with. Fan is going to bring her croquet this morning.”

Mamma had said, “Be very gentle and patient, help them over the hard places, and they will be your obedient servants”; but to have them mind simply because they ought to was a deal easier, and besides, Sue was so fond of croquet and the children would only be in the way. “You mustn’t stir one inch till I come back,” she said, lifting the little dumpy figures into the seat Bell picked out, and running off, mallet in hand.

It just suited Maybee,—the shouting, laughing, and general confusion; but poor little Tod! He couldn’t hide his face on Maybee’s shoulder because it would “rumpfle” her “ap’on,” and so he hung his round flaxen head at a right angle very trying to his bit of a neck. It was such a relief when a tall, black-whiskered man rang a bell and it grew suddenly quiet. He liked the singing and reading, and he could even venture to look around when the hum of study and recitation began. Maybee, on the contrary, found that dull and tiresome.

But we can’t begin to tell all the day’s trials,—how Maybee crept away to where Sue and Bell were busy with slates and pencils, and was picked up by the stern Mr. Blackman and dropped back into her seat as if she had been a spelling-book, after which Tod didn’t dare wink when anybody was looking; and how Maybee crawled away again to an empty seat, and played “keep house” with the peanut-shells, bits of chalk and crumbs stowed away in the desk; how she meant just to touch her tongue to the ink-bottle, and tilted it up against her nose and all down the “slippery” white apron; how Sue gave them their lunch at noon, and sent them alone to the pump to wash; how Joe Travers sprinkled water all over them, and Tom Lawrence ran off with the “apple turnovers”; how somebody called Tod a “toad,” and tried to scrub off his freckles, and everybody else laughed at the way Maybee’s saucy little tongue sputtered, and her big black eyes blazed with indignation; how Tod’s miseries reached a climax, just before school was dismissed, in a loud outburst of grief, and how Mr. Blackman, with pity in his heart no doubt, but multiplication and mountains and a million or less of other matters in his head, laid a huge hand on the little yellow pate, stopping the flow of tears as suddenly as a patent stop-cock; and how the tears turned to a big fountain of revenge way down in the angry little heart, so that when Sue tied on their hats and bade them walk straight along home, behind Bell and herself, Tod broke out with an emphatic “You bet! my’ll knock ’ou over.”

“Why, The-od-erer Smith! you wicked boy!” exclaimed Maybee, very much shocked.

Bell and Sue were already some ways ahead, talking over their new hats.

“All ’em big toads say it,” pouted Tod, “an’ my’s going to gwow till my can pound ’em heads off.”

Poor little Tod! Both lips and heart blackened with the touch of evil, so much worse than the dust and ink on Maybee’s white apron.

When the girls stopped at Bell’s gate the little flaxen and brown heads had both disappeared.

“They’ve lagged behind on purpose. Come in and I’ll show you my new dress,” said Bell. Then Sue must see it tried on. Of course the children had gone right along home. Sue wasn’t so sure, but Bell talked so fast it was half an hour before she could get away.

“They may have gone to aunty’s,” said mamma, looking anxiously up and down the street, after Sue had stammered out something about “waiting,” and “supposing,” and “not thinking.”

But they were not at aunty’s, and the two mothers ran here and there, half wild with fright. Uncle Thed was out of town, but Papa Sherman was summoned from the bank; and in the gathering twilight, men, women, and children went hurrying about the village, across the outlying green fields, into the dark, lonesome woods. Sue, up-stairs, her face buried in the pillows, sobbed and moaned and listened.

Oh, if she had only kept fast hold of the little hands! if she had only kissed the tired, dirty little faces! If she had only taken mother’s advice instead of Bell’s! Such sorrowful “ifs”! And then on her knees she whispered over and over, “Dear Father in Heaven, if you will only bring them safe back, I’ll never—never—never forget mother knows better than all the little girls in the whole world.”

“And He shall give Israel up because of the sins of Jeroboam, who did sin, and who made Israel to sin.”

Where were Tod and Maybee?

Half-way between the school-house and Bell Forbush’s, a sort of cart-path led off from the main road into Farmer Grey’s sugar-orchard, shaded with large, thick-leaved maples, carpeted with soft, green grass, and spangled with golden dandelions and buttercups.

“Isn’t it nice? S’ouldn’t ’ou like to go down it?” asked Tod, the new, “starched” shoes feeling, oh, so hot and dusty!

“Yes; but Sue wouldn’t let us,” said matter-of-fact Maybee.

“My don’t care, my will! ” returned Tod, shaking two soiled fists at Cousin Sue and her chatty friend. “Let’s wun.”

It was a sudden temptation, and Maybee yielded at once. Hand in hand they scampered down the cool, shady lane, never once stopping till the farther side of the orchard was reached. Then, how they rolled and tumbled in the fresh, green grass! What handfuls of daisies and violets they picked! and what a dear little brook they found, babbling along over the stones, and how fast and far they skipped along beside it, tossing in dandelions to see if the fishes liked butter, and launching bits of bark loaded with clover blossoms.

“Hello! What’s going on?” cried Dick Vance, the laziest, wickedest boy in school, now on the way after his father’s cows. Tod recognized one of his noon-time tormentors, and straightened himself up, muttering, “My’ll kill you, you bet!” with a furtive glance at Maybee, who was busy a little ways off, launching a whole fleet of maple-leaves.

“Ho! here’s a man for you,” cried Dick. “Ain’t he a stunner now! Regular man, he is.”

Tod relaxed a little at the compliment.

“Want me to make you a boat, a real boat with masts?” asked Dick, dropping down on the ground and opening his knife. Is there any magnet stronger than a knife to draw little boys to itself? Tod settled down just a few feet from the new-comer. Dick whittled and talked; Tod edged nearer and nearer.

“I wouldn’t make boats for many boys,” said Dick, “but you’re ’cute. If I had a sail, now! Let me have that red pocket-handkerchief of yours. By thunder! we’ll have a gay one.”

“By funder! my will,” echoed Tod, exactly as Dick meant he should.

Maybee had followed her little fleet quite out of sight. There was no one but the All-seeing Father up in heaven to hear, and Dick seldom thought of him; so he went on, saying vulgar, wicked words, and dreadful oaths, laughing till he had to hold his sides to hear Tod echo them in his droll baby-fashion. After a while Maybee came hurrying back into hearing of the low, mean words Dick was rattling off so glibly. Then she stopped.

“The-od-orer Smith, come right away, quick as ever you can!” she screamed, with her fingers in both ears. “My mamma says it’s catching-er than anything.”

Just then down went the sun behind the woods, and a great darkness settled suddenly around them.

“Who put ve light out?” asked Tod, huskily.

“God,” said Maybee, solemnly; and something in her large black eyes, uplifted so trustingly, checked the sneering laugh on Dick’s lips and made him slink quietly away, without even a whistle.

“Now let’s sit down and see God hang the stars out,” said Maybee.

“My don’t like it to be dark,” whined Tod.

“Why, don’t you merember what the verse says,—that one ’bout the chickens under their mamma’s wing?

What you s’pose my mamma meant, ’bout Sue’s wing? ’course she don’t have any, but God does; on’y He’s so big we can’t see Him cover us all up safe. I like to feel Him though, don’t you?”

“No,” said Tod, “my’s afwaid of bears an’ fings.”

“Pho! it was naughty children the bears in the Bible eat,” returned Maybee,—which remark was sorry comfort to poor Tod.

“Ma-bel! Ma-a-b-e-ll!” called somebody away off in the distance.

“Oh my! I do b’lieve we’ve forgot to go home,” exclaimed Maybee, jumping up and pulling Tod in the direction of the voices.

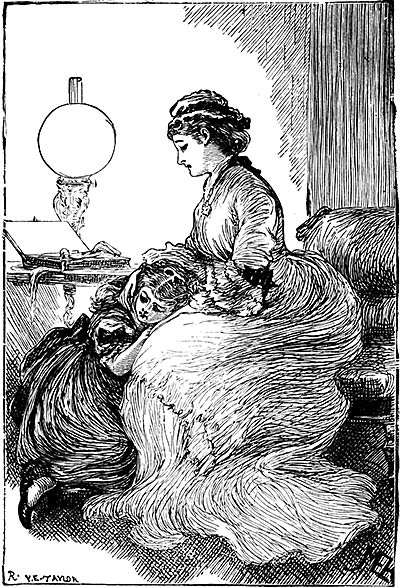

You must imagine all the kissings and huggings, how soundly Tod slept all night, and how Sue kept pinching Maybee to be sure she was really there. The saddest thing is yet to be told.

At breakfast next morning Tod used some of the wicked words he had learned. Oh, how grieved and shocked his mamma was! Tod was positive he should “never do so any more,” after he had been away with her up-stairs and asked God to forgive him. But the very next day, although Sue scarcely left the children a moment, Dick contrived to coax Tod away, and persuade him it was manly to swagger and swear; and then Tod kept trying it a little all by himself, and somehow the bad words would slip out when he didn’t mean them to. Mamma talked and punished,—little punishments at first; then she tried scrubbing the inside of his mouth with soap-suds, and twice she shut him up a whole day, with nothing but bread and water. Still Tod persisted in “talking big,” as he called it, and at last, with tears in her eyes, mamma gave him over to Uncle Thed, who took him away into the library, and used a little stick just as Solomon says we must sometimes. Then he insisted on a whole long week without any good-night kisses from mamma, which almost broke poor Tod’s heart.

“My’ll never say ve bad, ugly words adin; my hates ’em!” he broke out one night, just as mamma was going down-stairs; and this time he kept his word.

Do you think they were cruel to the little boy? But you know Maybee’s white apron had to be soaked, and rubbed, and boiled, and bleached, before it was fit to wear again.

And so, although naughty Dick was sadly to blame, we are sure, when Tod is a man, he will be thankful for all the suffering which helped take away the stain of that dreadful sin from his heart and tongue.

“But evil men and seducers shall wax worse and worse, deceiving and being deceived.”

Whiz went a paper-wad past Ned Holden’s head. He didn’t need to look up from his Compound Interest to know where it came from: most of the mischief started with Dick Vance. Little Joe Burns, puzzling over c-o-u-g-h, b-o-u-g-h, d-o-u-g-h, caught a glimpse of Dick’s eyes through a pair of green goggles and giggled outright. Sue Sherman tripped and fell on her way to the grammar class, but the string was in Dick’s pocket before anybody saw it. But that wasn’t the worst of it. Wherever Dick was on the playground, there the boys played “for keeps,” cheated in “tallies,” swore over their quoits, and made ruinous bargains in jack-knives; and where Dick was, there too were more than two thirds of the other boys. You can easily guess he wasn’t an ugly, cross-grained, disobliging fellow. That isn’t the kind of stuff Satan chooses to make tools of. No one could learn more quickly than Dick, although he hated study and seldom had a perfect lesson; and a better-natured, kinder-hearted boy you couldn’t find in that school or any other. So whatever Dick said “Do,” the others generally did, and whatever Satan put into Dick’s head was generally the thing to be done. And Satan was leading him from bad to worse as fast as possible. A year ago, Dick would have scouted the idea of taking a twenty-five-cent scrip from Mr. Bower’s money-draw. It began with a few nuts “hooked” when Mr. Bowers was drawing molasses: it would end—where? Dick never stopped to think.

The week Tod began going to school, Dick played truant one day. It was the first time; for the boys, even the scape-grace Dick, stood very much in awe of Mr. Blackman.

“Won’t you catch it to-morrow?” said they all; but the next morning Dick walked coolly up to the master’s desk and presented a note of excuse. And then what a glee he set the boys into, telling how he had to pretend somebody was driving cows and one ran down a lane, and there was nobody to help but Dick, although it made him late at school, and Mr. Blackman would insist on his bringing an excuse. Just a word and his father’s name would do.

O Dick! You would have scorned that lie a year ago.

But now it seemed quite the thing; and when a large circus was advertised in an adjoining town, it was an easy matter to persuade, not only himself but Joe Travers also, there would be some way of getting round “old Blackman.”

Now, one thing is certain about a circus: there may be lots of good people there, but there is sure to be plenty of wicked ones, and Dick very naturally got among them,—fellows who had outgrown marbles and taken to cards.

Nothing else would have drawn Dick into the low drinking-saloon, or tempted him to taste the vile stuff sold there. They had a “Band of Hope” in school, and Dick had always stood by his pledge. But he was in for a “good time” to-day, and before he knew it had drank enough to make him reckless and quarrelsome.

Fortunately for Joe, that state of affairs disgusted him and sent him off home, tired and cross enough to confess anything. Fortunately or unfortunately for Dick, stumbling over the same ground several hours later, business had suddenly called his father out of town; his mother’s thoughts were all on her dairy and kitchen; to-morrow was Saturday,—no hurry about Mr. Blackman. Dick’s chief concern was how to keep a promise made his new acquaintances to go gunning the next Sunday. He had been brought up to respect the Sabbath, outwardly. Mr. Vance always shaved, put on his best clothes, and read his newspaper. Dick put on his best clothes and lounged on a sofa over the vilest trash put up in an illustrated weekly. Mr. Vance didn’t believe in any kind of religion. Mrs. Vance was always too tired to go to church. To them, it was man’s day of rest simply, not God’s Sun-day of light and love and praise. No wonder Dick seldom thought of the all-seeing Eye, looking straight down into his wicked heart, reading all his plans.

It was easy enough: wrong-doing so often is. He asked permission to spend the day at his grandfather’s, some four miles away. He frequently walked over there on Sunday; and getting an early start before his father was up he had nothing to do but take down the old gun from the shed-chamber and stroll away at his leisure. But long before noon Dick was thoroughly tired of being ordered about, sent to pick up the game, sworn at for being in the way, in short, of being made to feel his youngness,—not of the sin, nor of seeing the poor little birds and bright-eyed squirrels, to whom the sunshine and green trees meant so much, writhe and gasp, and die in his hand. He determined at last to strike out for himself in quite a different direction from the others. Up and down the woods he tramped. All the birds and beasts must have been taking their noonday nap; Dick grew impatient, and suddenly brought his gun to the ground, with an oath. There was a loud report, a stifled scream, and poor Dick lay senseless on the ground.

“In famine he shall redeem thee from death, and in war from the power of the sword.”

Such a funny little clatter! The birds waked up from their afternoon nap, and half a dozen brown nut-crackers stopped to listen, with one tooth just inside the tempting white kernel.

“I’m so glad we came home this way,” Maybee chattered on, quite unconscious of the scores of bright eyes watching her. “Only look, mamma! I guess here’s where the birdies and butterflies had their Sabbath School. So many yellow buttercups, just like little question-books, and daisies and violets for picture-cards; and don’t that funny little brook sound mos’ like a m’lodeon? Oh, see that birdie washing his face! How do you s’pose they merember which tree they live in? I guess their mammas are telling ’em Sunday stories now, they’re so still. Oh, my pity! Here’s all their dear little water-proofs,” and down dropped Maybee in a patch of dainty, nodding, pink lady’s slippers. So many, and such splendid long stems!

“What do you s’pose God made ’em all for?” said Maybee, thoughtfully, trotting after mamma with both hands full.

“I wonder if old Aunty McFane wouldn’t like a bunch to stand beside her bed?” smiled mamma.

“May I give her some my own self? ’cause there’s nobody to pick her any. Mose has to go straight to that rackety old mill soon’s he’s got breakfast, an’ Peter’s too little. ’Sides, Mose won’t let him go in the woods, ’cause he’ll get lost. I b’lieve I must run, mamma; I’m in such a hurry.”

She was back in a trice, however, pale and trembling. Hadn’t mamma heard something very dreadful? Mamma listened to little faint twitterings up in the tree-tops,—that was all,—and pinching the color back into the dimpled cheeks, they walked on, up the path leading to the low, red house where the McFanes lived.

Little brown sparrow sitting close under the eaves could have told them what Maybee heard; she had been watching the tumbled, dusty figure dragging itself slowly and painfully along across the fields from the woods. Poor Dick! It was such a long way to the little red cottage, and then when he tried to call somebody, everything grew strange and dark again; the queer little groan he gave was what Maybee heard. By and by he opened his eyes, but somehow he didn’t care to move or speak. He heard little brown sparrow twittering to herself up under the eaves; he heard the brook gurgling noisily along down in the hollow, and then he heard voices through the open window,—a thin, piping voice saying, “But God didn’t send any wavens to bwing it, gwan’ma, as he did to ’lijah.”

“No, deary; grandma didn’t say he would. You see, ma’am, I’ve told him stories to make him forget like he was hungry, and there’s none like those in the good Book. O ma’am! there’s nothing like that, and the harder things are, the tighter you can take hold of the promises. You mind, ma’am, when that baby was left on my hands an’ me only jest able to hobble round, and how at last it came to lying here from morning till night, with only Mose to help, out of mill hours; but that wasn’t nothing at all to having his work stop entirely, and the little we’d scraped together go and go, and he a-worrying an’ tryin’ to find something to do. Five weeks to-morrow! and last Monday we hadn’t a cent left. He’s tried everywhere for a job; that last tramp over to Luskill Mills is what ails his feet. Friday morning he couldn’t step a step, and not a thing in the house but some dry bread. We’ve never trusted Peter alone, so he dars’n’t go as far as the main road, an’ we’re quite a ways off of the path, even. But I knew the Lord could send somebody. He does hear when folks pray. Don’t you see, Peter, instead of the ravens he sent the kind lady?”

“We come home this way ’cause it was so hot,” put in Maybee; “but I do b’lieve He let Sue come tagging after, so’s mamma could send her home quick to bring you some supper, and p’raps He just made those flowers a-purpose; you know he sees to the sparrows.”

“Does He really?” thought Dick, looking up at the nest over his head. “I wish—but I suppose He knows how wicked I’ve been, and won’t care. I wonder if that’s Sue?”

A light, quick step went up the walk, followed by a scream of delight.

“You must excuse the little fellow, ma’am; he’s so ravenous,” said a man’s voice, and it trembled too. Dick wondered if he was crying. Then he heard the rattle of dishes and the hum of the tea-kettle, and by and by a pleasant voice bidding Sue run back and ask Dr. Helps to come and look at Moses’ feet.

“You won’t disbelieve again, will ye, Moses?” said the grandmother. “You see, ma’am, he couldn’t just believe God cared anything about us, and it’s dreadful to be in the dark and not feel sure there’s an Eye seeing the end from the beginning all along, and a Hand ready to help as soon as ever the right time comes.”

“I wonder if He saw me down in the woods,” thought Dick, dreamily, the voices sounding farther and farther away. “What was it grandpa used to tell me,—‘Remember the Sabbath day’; but I didn’t forget it; I never cared. I wish He wouldn’t look way down in my heart; it’s such a great Eye, and it sees all the bad. Oh, how bright it is, and it hurts so! If He only would go away!”

But the sun, which Dick fancied was the great all-seeing Eye, shone steadily down on the poor, pinched white face, and the voices inside went on:—

“It doesn’t seem, gran’mother, as if such a great Being could care for poor, wicked creatures like us.”

“He made the littlest flower, Moses, as well as the great mountains; and as for the wickedness, didn’t he let his own dear Son die just for us?”

“O me! I do b’le’ve I’m going to cry,” said Maybee, slipping past the doctor and around the corner of the house, full upon Dick, lying still and white, with a wild, staring look in his eyes.

Her screams summoned mamma and the doctor, who together carried him into the one front room of the cottage, and laid him on the “spare bed,” clean and white, if Mose had been sole housekeeper for many months.

“He mustn’t be moved again,” the doctor said; but “they could bring whatever they pleased to the cottage,” he added,—a hint Dick’s father wasn’t slow to take, for besides idolizing his boy, he was a kind-hearted man, and fairly shuddered when Maybee’s mamma told him how nearly starvation had come to the little red house.

Dick knew nobody that night nor for many days; but the sun, as it peeped in morning after morning, and crept reluctantly away at night, found out two things,—that Dick’s mother loved her boy better than her dairy, and that little Peter was growing fat and rosy on something besides “dry bread.”

“And Joshua said, Why hast thou troubled us? The Lord shall trouble thee this day.”

Dick opened his eyes one morning and began to wonder where he was. It seemed as if he had been sailing over mountain-tops and crawling about underground for years. And now, could anybody tell where he had waked up? It wasn’t like any room at the farm-house,—the white-washed walls, smoky ceiling, and bare floor. Such funny red posts to the bedstead, and a big, clumsy red chest under the window! On the chest were tumblers and bottles, and beside it, in a creaky wooden chair, sat a fat, jolly-looking woman, rocking away as if she had nothing else in the world to do. Where had Dick seen her before? Oh, he remembered! she came to their house when his mother had the fever last fall. Through an open door he could see a cooking-stove, a little red-haired, red-stockinged boy, playing with a Noah’s Ark, and another bed, with such a pleasant old lady’s face on the pillow,—such a happy, smiling face,—and a thin, wrinkled hand stroking lovingly a bunch of dry, faded flowers on the stand close by.

While he was watching her, somebody leaned over and kissed him. Dick’s eyes filled with tears, but he knew his mother through them. Only it was so queer for her to kiss him. He could just remember her doing it when he wore dresses, like the little red-haired boy. Since then she had been too busy; she always praised him when he ran errands promptly; she laughed at his jokes and tricks, kept his clothes clean and whole, and made him no end of pies and cakes. Indeed, she was always baking, brewing, churning, sweeping, dusting, mending, or sleeping. She came around the bed now, with a bright little porringer in her hand, gave him something nice to swallow, tucked the clothes around his shoulders, and told him to lie still. He shut his eyes, and was sound asleep before he knew it. When he opened them again the nurse was nodding in her chair, the tea-kettle singing on the stove, and the pleasant-faced old woman sat bolstered up in bed, with the little red-haired boy and our old friends, Maybee and Tod, curled up on the foot, listening with all their eyes and ears. So Dick listened too.

“You see we can’t do wrong,” she was saying, “without troubling somebody else, like the little black-and-white rabbit, you know.”

Peter nodded “Yes.” “No; what was it?” said Tod.

“Why, once there was a little black-and-white rabbit named Dot. He lived with his mother and sisters in a nice little house, in a nice large yard full of green grass. But he was always fretting and whining to get out and hop about the lawn and garden. He liked to nibble the trees and the tender green sauce. ‘Which is exactly what master says you mustn’t do,’ said his mother. ‘He’s mean,’ snarled Dot. ‘No, he isn’t; he gives you plenty to eat that’s nice, and besides, he says there are cruel boys and dogs outside. I advise you to listen to him,’ and Mrs. Bunny took a mouthful of fresh clover. ‘I’ll risk ’em,’ muttered Dot, digging away at the palings till he found a hole big enough to crawl through. ‘I wish you’d show me where the garden is,’ he asked the first boy he met. ‘To be sure. Perhaps you’d like me to carry you?’

“Dot was lazy and forgot all his mother’s warnings. He had a most delightsome ride, but, oh dear! at the end he found himself shoved, head first, into a low, dark box, with hardly room enough to turn around. There he stayed pretty nigh a week, with nothing to eat but coarse hay. His new friend tormented him almost to death, pulling his ears, pinching his nose, and punching him with sharp sticks, and at last he grew so thin he managed to squeeze through between his prison bars. Good or bad luck led him straight into a most beautiful garden, with beds of beets, turnips, radishes, celery, lettuce, everything tender and sweet as sunshine and dew could make it. He ate so much he could scarcely stir, and was just about to curl down under a currant-bush for a quiet snooze when a big man began pelting him with stones. Poor Dot! limping and panting he tried to find the gate, but had finally to crawl under a stone wall. He slept there that night, and didn’t dare even to stick his nose out the next morning till he was so hungry he couldn’t wait another moment. There was a nice clover-field close by, but he had hardly taken a nibble when up ran a big black dog, growling and barking, and there would have been an end of Dot but for a blackberry thicket. He dived into that, and Bose had too much regard for his sleek, fat sides to follow. Every few minutes, however, he would come capering back, and set Dot’s heart beating so he was sure it would come out of his mouth. Not for hours did he dare venture out, all bleeding and dirty, the forlornest looking creature you ever saw. But that wasn’t the worst of it. He was real thankful to see the white palings of his old home just ahead, but instead of going straight there, naughty Dot concluded to take a final stroll across the lawn and taste of the young fruit-trees in the orchard. It was an unfortunate time, for Harry’s papa—Harry was Dot’s little master—had just started to drive down the carriage-way, and Billy, although a very discreet old horse, was nevertheless woefully afraid of anything white. He shied suddenly at sight of Dot, overturned the buggy, and left poor Mr. Wells lying on the ground with three broken ribs.

“‘Such a bad, ungrateful, disobedient rabbit!’ groaned old Mrs. Bunny, when Dot at last crept back through the same hole he went out of. ‘See how much trouble you’ve made! Poor old Jones was depending on his garden-sauce to pay his rent; that Joe Barker got whipped for being late at school three mornings; and here’s master laid up for nobody knows how long.’

“‘Nobody knows the trouble I’ve had,’ grumbled Dot, snatching at the fresh, sweet clover. ‘How could I know whose garden ’twas, or imagine that great horse so silly as to jump at poor little me?’

“‘You couldn’t,’ returned his mother, gravely. ‘You aren’t old or wise enough. That’s why we need a Master to tell us just what to do. You see, things are all joined together somehow, and doing just one wrong thing is sure to make no end of a bother. Mark my word, there’s nothing like having a good master, and doing exactly as he says. If you don’t, there’ll be trouble all round, depend upon it.”

“And Elijah said, How long halt ye between two opinions? If the Lord be God, follow Him; but if Baal, then follow him.”

Dick found lying still from morning till night very dull and tiresome. Mose was at work again, and as the good-natured nurse took upon herself the general house-work, which Mose had managed for more than a year under his grandmother’s direction, Dick was necessarily left alone a good part of the time. It was quite a relief when little Peter was allowed to scramble over the bed, asking questions by the score; still more delightful was it to be bolstered up in the big wooden rocker and drawn out into the cheery little kitchen beside cheery old Aunty McFane, who knew exactly the kind of bear stories boys like best to hear. It seemed a little strange nothing was said about his going home, and that lately his mother had so seldom come to see him.

One day when nurse had gone out to gossip with some of the neighbors, Dick’s patience gave way, and he broke out, with an oath,—

“Great deal folks care for a fellow,—not to come nigh him for most a week! Shut up in this hole, kept on slops, and the doctor running knives into you when he takes a notion.” Another oath finished the sentence.

“Didn’t you know, haven’t they told you your mother was sick?” said Aunty McFane, gravely.

Dick leaned back among his pillows, white and trembling. “How—why—what made her sick?” he stammered.

“She jest overdone, tending to her work and looking after you; and one day, when you was the worst, she came in the rain and got chilled through. She’s never been well sence, but she kept up till last week. She was better yesterday. I don’t think God means to take her from you just yet.”

Dick looked steadily at the old clock; the little mouse nibbling away in the pantry stopped to hear how loud it ticked through the stillness.

“It’s like the little black-and-white rabbit,—all comes of my going to the —— circus,” said Dick at length, with another oath. He didn’t mean to add that: it slipped out before he thought.

“Yes, it is like. Folks, as well as rabbits, need a good and wise Master,” said Aunty McFane, very soberly. “Do you know who is your master, Dicky?”

Dick moved uneasily. Ever since the day he was hurt, that great, all-seeing Eye had seemed to be looking straight into his naughty heart, and it wasn’t a comfortable feeling.

“I—suppose—it’s—God, if He’s everybody’s,” he said, in a low voice.

“Oh no! God hasn’t any servants only those who choose to obey him. It was Satan who told you to go to the circus, and coaxed you off gunning on the Sabbath, and put those dreadful words in your mouth just now. God’s commandments are very different. You know what they are, of course, Dicky?”

“The ten commandments? Grandpa used to tell me, but I—why, I keep most all of them, I guess. I don’t make ‘graven images.’”

“I don’t suppose you do yet, sonny, as the men do who worship their big stores and houses; but if we love anything better than we love God, it’s an idol, an’ I’m afraid you’ve got one idol named Self. And then there’s ‘Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord, thy God, in vain,’”—Dick dropped his head,—“and this, ‘Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy.’”

A little lower drooped the red face.

“Honor thy father and mother.”

“I’m all right there,” cried Dick, suddenly straightening. “I never call my father the ‘old man,’ as some boys do, nor make as if I was too big to mind mother.”

“I’m glad of it, Dick; I hope you can plead ‘Not guilty’ to all the rest; only remember Jesus said, ‘Whoso hateth his brother is a murderer.’ And then there’s the ‘new commandment’ Christ gave us, ‘Love one another.’”

“There’s—I—you know, the other one, ‘Thou shalt not steal,’ and I—I have taken things, little things, sometimes,” said Dick, hurriedly.

“O Dicky Vance! To think Satan could make a brave, kind-hearted boy like you into a thief. How does he pay you? By making you real happy and giving you lots of fun? At the circus the other day, for instance.”

“I should have had a good time if I hadn’t got in with those fellows.”

“But it’s just ‘those fellows’ Satan will always keep you with.”

“We had a tip-top time the other day; we played truant,” said Dick, eagerly. “We went fishing away up by the Crossing, and there didn’t a single bad thing happen. I don’t like stories where every bad boy gets drowned or something.”

“Nor I, either; but did you feel all right? Didn’t you have to keep looking round to see if anybody was coming, and go ever so far out of your way for fear of meeting some one?”

“Why, how did you know?” exclaimed Dick, in surprise.

“I didn’t; I only know it’s the way Satan’s servants mostly do. I shouldn’t think a boy like you would fancy that,—sneakin’ round, afraid to look in folks’ faces. Now, ain’t you ten times happier the days you learn all your lessons and mind the rules, than you was then?”

“I don’t try that often enough to know,” said Dick, laughing and coloring at the same time. “I’ve thought more’n once I would turn square round and keep right up to the mark; but it’s a plaguy bother to toe a straight crack.”

“Now, take my word, Dick, it isn’t half so hard as ’tis to toe Satan’s crooked ones; and besides, my Master helps his servants; he don’t call them servants, he calls them children. Only think! the great God, who made heaven and earth, letting us call him Father, hearing us when we pray, and promising to help us over all the hard places. Why, Dick, he would even help you get your lessons.”

Dick shook his head unbelievingly.

“But I’ve tried him,” continued Aunty McFane, earnestly. “I’ve tried him more than fifty years. He says he numbers the hairs of our heads, and there can’t be anything littler than that. And then he sent his only Son to die for us. We hadn’t done as the Master, who knew better than we, had told us to do, and so Jesus came to ‘save us’ from our sins. Does your master make any such way for you out of trouble? Which do you think is the best one to follow, Dick? because you can’t serve both; you must choose.”

Dick made no reply, and Aunty McFane, too wise to spoil what she had said by saying too much, closed her eyes as if to sleep. I think, way down in her heart, she was asking God to bless the poor boy and help him to choose then. By and by, laying one hand suddenly on his shoulder, she quietly said, “What would have become of you, Dick, if God hadn’t sent little Maybee here that day?”

Dick buried his face in his pillows and burst into tears.

“The God that answereth by fire, let him be God.”

“Come here, you little toad! Before I would play girl-plays the whole time!” cried Joe Travers, one of the big boys, to our little friend Tod, who was running as mail-agent between two of the pretty play-houses under the old oak.

Tod dropped the brown paper mail-bag as if it had burned him, and looked around. Maybee’s sharp little tongue was buzzing away in the farthest corner of the playground. Sue was busily “setting table.”

“Come over here, and we’ll have some jolly witch stories,” called Joe, persuasively; and over went Tod, leaving the poor mail bag, containing Sue’s invitation to a “kettledrum,” and Bell’s telegram for rooms at the Polygon Hotel, soaking in a little pool of water left from yesterday’s rain.

Tod had become a general favorite with both boys and girls. His shyness led him to choose the latter; but the boys, having discovered his fondness for “horrifying stories,” liked nothing better than to get him away by himself, and manufacture the most frightful tales possible on purpose to see the big blue eyes open to their widest extent, not caring a straw that they resolutely refused to shut at night unless mother was close by. To-day, however, Joe had only a simple witch story, about a little boy, stolen from his parents and brought up in a hovel, but finally rescued by the witch and restored to his real father, who lived in a splendid palace, etc. etc.

“Guess, then, him had bus’els of choc’late ca’mels, and riding-horses,” said Tod, smacking his lips.

“Don’t you wish you was that little boy?” put in Tom Lawrence, rather disappointed that Joe’s story was no more exciting.

“Well, but I know something,” said Joe, with a wink at the other boys. “I met an old woman this morning, an’ she told me—”

“What?” cried a dozen voices.

“Well, suppose Mr. Smith wasn’t Tod’s father.”

“My sha’n’t!” said Tod.

“Oh! you needn’t unless you want to; only if ’Squire Ellis was my father, and I could live in that big house on the hill, and have a pony and a dog and a gun and all sorts of things—”

“Did—she—say—my papa—was that great, big man with a cane what keeps that great big store an’ wides two horses to once?” asked Tod, excitedly.

“Oh, I can’t tell you any more, you’ll have to find out yourself,” returned Joe, very sure an idea, once lodged under the flaxen curls, would never lie still.

All the afternoon Tod thought it over. Every morning, of late, he had lingered in front of a new café, looking longingly at the snowy méringues, set off by dark, rich chocolate-browns. His sweet-tooth was one of Tod’s weakest points, and for that reason Papa Smith rather limited his supply of pocket-money, and seldom fished anything less harmless than peppermints out of his own pockets. Tod supposed it was simply from lack of means. Esq. Ellis, now, “could just buy that safe man out if he wanted to.”

“P-i-g, ponies,” spelled Tod, with such a grand plan in his head he could think of nothing else. When school was out he privately invited Maybee to a picnic in the grape-arbor at six that evening, and then, under pretence of going round by his father’s shop, set off alone up the main street. Straight into the big store he marched. Esq. Ellis was busily talking with a couple of men. Tod had been taught manners, and waited patiently beside him till the gentlemen turned to go, then he began: “Please will you—”

“Carter wants that order filled before six o’clock,” said a clerk coming up in the opposite direction.

Tod clutched at the broadcloth coat:—

“If you please—ice-cream an’ ca’mels,—they’re so jolly; an’ if—you know—I’m your little boy—couldn’t you just give me fifty cents right straight off, please? My wants it the very worse kind.”

The busy merchant glanced down into the earnest little face; the clerk touched his arm; he turned quickly.

“The impudence of these beggars! Scott, I thought I told you not to allow them inside. Is that bill made out for Edson & Dodge? And don’t forget Dorr is to have samples at once. How about Carter now?” and he hurried away.

Tod walked dejectedly to the door, his little heart swelling with grief at that horrid, horrid word “beggar.” What if his face and hands were grimy and his apron torn? “My guesses,—’t any rate, my’ll try the other one,” and off he flew up the street, around the corner, into his father’s office. Papa was there, talking to a man of course. Tod slipped one grimy hand into his and waited, choking back the grief that would keep the red lips in a quiver. And the moment the man was fairly gone, he sobbed out,—

“Please, papa, won’t you? it’s so jolly! Just fifty cents for ice-cream and ca’mels. My wanted a party so bad! but he wouldn’t, an’ she’s coming, you know.”

“If you please, sir, Thorpe is waiting to know about that No. 7,” said somebody in a white paper cap.

“In a moment, John,” said Mr. Smith, sitting down in his chair and taking Tod in his arms. “Now, papa’s little man, what is the matter?”

“Just fifty cents, please, papa, for Maybee and me to buy choc’late. My wants it so bad, papa,—jus’ the worst kind.”

“Dear me, that’s very bad, isn’t it? and Sweet-tooth has been very patient of late, to be sure. So Maybee is coming to a party! Well, well, there’s a bright, new, silver half-dollar . How’ll that do? because papa’s in a dreadful hurry.”

Nose, chin, whiskers and all,—how Tod covered them with kisses, squeezing his “own-y to-ny papa” tight as two little arms could.

“Guess my knew how to find out certain true,” he said, sitting with Maybee under the grape-arbor half an hour later, both faces well plastered with chocolate. “Guess the own papas see through a hurry, quick ’nough, when my asks ’em weal hard.”

“Will He plead against me with his great power? No; but he would put strength in me.”

When Dick came back to school you would scarcely have known him, he had grown so tall and stout. The younger boys looked up at him admiringly; the older ones held a little aloof.

It wasn’t at all the Dick who ran away to visit the circus a few months before. In the first place, this Dick was a travelled youth. As soon as his mother was able to ride out, the doctor had ordered them both up among the mountains to try what the clear, bracing air would do to mend matters. It was up there in a little nook among the rocks, with only a bit of blue sky looking in between the tall trees, his mother, with one hand laid lovingly upon his shoulder, had told him how sorry she was she had all these years been too busy to love and serve the kind Father above, who had spared their lives and given them so many blessings, and how she meant now to try and please Him first of all. Dick was very sure he meant to be a better boy, but he didn’t care to think much about God. Of course he could be good just as well. So this Dick went to church and Sabbath School; this Dick was trying not to swear, and no longer loafed about the street-corners and saloon-steps.

The boys had an idea it would be a very sober, stiff old Dick, but they soon found out their mistake. He was as full of fun as ever, only now he tried to keep it for playtimes. Study, however, was uphill work; he had been idle so long, and there were plenty of boys ready to laugh at his blunders, to tempt him into some sly fun, and especially to report every time he swore or broke a rule. Mr. Blackman, too, remembering the old Dick, was forever accusing him of this, that, and the other bit of mischief. Poor man! Wasn’t he tried almost out of his life with the care of so much perpetual motion, and hadn’t Dick always been the most troublesome screw in the machinery? And wasn’t it the most natural thing in the world, when anything went wrong, to give that the first twist?

The brook, beside which Dick gave Tod his first lesson in swearing, ran through a large field not far from the school-house. There the boys went to drill, to fly their kites, and to play base-ball. The brook was much wider there, with a high, steep bank on either side, and of late the boys had taken to walking across on the narrowest plank possible, balancing on one foot in the middle, turning somersaults, and otherwise imitating Blondin at Niagara. The water was shallow and the bottom sandy, so their frequent tumbles resulted in nothing worse than a wetting.

One day, as Tod stood by in open-mouthed astonishment at their performances, it occurred to Tom Lawrence what fun it would be to make the little fellow walk across.

“My couldn’t,” said Tod, his teeth chattering at the bare suggestion.

“Oh yes, you can,” joined in half a dozen boys, ready, as boys too often are, for any fun, no matter at whose expense. “Quick, now, or we’ll duck you!”

“Here comes Dick Vance; he’ll send him over quicker’n lightning,” cried Joe Travers.

Tod looked around at the tall, stout figure leaping the wall; almost a man, Dick seemed to him. Poor little Tod! he felt his doom was sealed, and trembled to the tips of his shiny shoes.

The boys crowded up, shouting, laughing.

“Make him go over there? Of course I can;” and Dick, swinging the little fellow upon one shoulder, bounded over the narrow plank before anybody had time to think.

The boys cheered lustily; boys are never slow to appreciate a daring deed. But “It isn’t fair!” “No play!” followed close upon the cheer.

“You’ll have to do it, Chicken Little, or they’ll make a prodigious row,” said Dick. “Look here, now. I’ll hold one hand all ready to catch you, and promise, sure as I live, you sha’n’t fall; and do you trot straight along without thinking anything about it. Why, it’s just as easy,—with me, you know.”

“You bet! By funder!” rejoined Tod, with a sudden explosion of bravery.

“Don’t let’s say that sort of words any more,” said Dick, looking ashamed and sorry. “Let’s just say we’ll try.”

“My will,” responded Tod, confidently, trudging on without looking to right or left. “My can do it, ’cause your hand is so big.”

Tod cheered as loudly as anybody when he was safe on terra firma again, and then the boys strolled off to base-ball. “What’s up now?” they wondered, as Dick struck off into the woods instead of joining them. “Oh! it’s that fuss this morning. Dick’s riled; got some of the old grit left.”

That morning Dick had made a mistake in putting an example in Long Division on the board; while he was diligently hunting it up, the boys in the back seat—of course Dick was yet in the lower classes—began to chuckle and cough provokingly. Tom Lawrence wiggled his fingers insultingly, and quick as a flash, Dick chalked out a head on the board, unmistakably Tom’s, with a big balloon for a body.

“So that’s the way you do examples!” said Mr. Blackman, coming up just as it was finished. “No wonder such a dunce calls nine times seven, sixty-four. Rub that sum out, sir, and do it over.”

Now, of course, Dick was wrong and Mr. Blackman was right; only, if the latter had known how hard Dick had studied that ninth table the night before, for fear he should fail, and how patiently he was trying to find his mistake when the boys began to laugh, he wouldn’t have spoken just so. Dick was quick-tempered,—such natures always are,—and in a trice he had swept figures and face from the board, and taken his seat.

“You are to put that example on the board again,” said the master; but Dick was firm as a rock; he couldn’t,—wouldn’t,—shouldn’t.

There the matter stood. Until he did, and at the same time made a public apology, Mr. Blackman would not consider him a pupil.

Dick sat down under a tree to think it over. Such a pity to leave school just as he was trying to learn something; but—put that example on the board again? He never could. Expelled! How grieved his mother would be; but a public apology,—never! To be sure, he ought to obey Mr. Blackman; he had really been trying to; but this,—this was too hard. How could he?

What was it Tod said? “My can, ’cause your hand is so big.” How queer that should remind him of his talk with old Aunty McFane, about masters! What did she say?

“My Master will help over all the hard places if you ask him.”

His mother prayed, Dick knew, but he had never really felt like it himself. God was so great; but then, he cared for the sparrows. He was so great? Why, that was the very reason he could help everybody. What was the text his mother had repeated only last Sabbath evening? “I, the Lord thy God, will hold thy right hand, saying unto thee, Fear not, I will help thee.”

The boys stared the next morning, and some of them, I am sorry to say, sneered a little, when Dick, after saying, “I am sorry, sir,” went resolutely to work upon his example again; but Mr. Blackman shook him heartily by the hand, remarking,—

“Only keep on in this way, Dick, my boy, and you’ll surely make a worthy man as well as a fine scholar.”

And Dick, with a bright smile on his face, thought, “‘My can,’ because God’s hand is ‘so big,’ and he does help folks when they ask him.”

And Ahab said to Elijah, Hast thou found me, O mine enemy? And he answered, I have found thee: because thou hast sold thyself to work evil in the sight of the Lord.

Bell Forbush had told something very private to at least fifteen of the girls, nothing more or less than that her Cousin Mate, the dearest, prettiest cousin anybody ever had, was coming to stay at her house two whole months. She was grown up, and very stylish, so rich she didn’t know what to do with her money, and yet so good everybody loved her almost to death. For weeks after her arrival Bell regaled the girls with descriptions of Miss Marvin’s dresses and jewelry, the latter having a special fascination for Bell, particularly a necklace and cross, to possess which, she more than once hinted to Cousin Mate, would make her perfectly happy.

“My mother gave it to me just before she died,” her cousin had said very sadly, which ought to have made it sacred in Bell’s eyes. She had a father, mother, and two big brothers, while poor Cousin Mate was an orphan, with no nearer relative than Bell’s mamma. She was very kind to the little girl, too, letting her wear her coral pin and bracelets to school, and opening the pretty ebony jewel-case whenever Bell wanted to feast her eyes on the pearls and rubies inside.

But oh, that necklace and cross! There was nothing quite like that. Bell tried it on over all her dresses, and lay awake nights fancying how she would look at church in it, and what Nettie Rand would say to see her wearing such an elegant thing.

About this time Jenny King had a birthday. It came on Saturday, and she made a tea-party for her friends. Bell’s new white piqué was just finished, and Cousin Mate had given her a wide blue sash to wear with it. If she could only have the necklace and cross!

Wasn’t it queer Cousin Mate should happen to go away the day before, to stay over the Sabbath? Had she taken the necklace with her? Bell crept up-stairs just at dusk to see. Didn’t Cousin Mate always let her look at it whenever she liked? and, yes, there was the tiny key left in the ebony casket. Suppose she should wear it, what harm would it do? Cousin Mate would never know it, and it was only borrowing, any way. To be sure, she ought to ask leave, but—

Bell kept thinking it over,—how beautiful the soft shimmer of gold would be in the lace at the neck of her dress, and how the lovely pearl cross would gleam out from among the blue ribbons.

The more she thought, the more it seemed she really must. It wasn’t so very wrong, and something might happen: Miss Marvin might think it was lost, and she could keep it for her very own. At break of day she stole into the spare room again, and slipped the chain into the pocket of her new dress, ready to put on when she reached Mrs. King’s.

“I—mother—mother was afraid I—might lose it—under my shawl,” she explained to that lady, who offered to clasp it for her, saying, It is something quite new, isn’t it, dear?——”

“Oh! it—it is Cousin Mate’s; she—she lent it to me,” stammered Bell.

“I didn’t believe it was yours,” said Nettie Rand, provokingly.

“It isn’t mine yet,” returned Bell, reddening, “but Cousin Mate has just as good as promised it to me.”

Ah, Bell! there is no addition like that Satan sets us to do.

But how heavy the little chain grew before night! or was it the sense of wrong-doing made the time drag so wearily to Bell, and made her so glad to wrap her shawl over the long-coveted possession and hurry home through the dusk? Who should meet her on the steps but Cousin Mate herself, returned unexpectedly, and ready, as she always was, to take off the little girl’s hat and give her a kiss.

“I—I—it’s cold,” said Bell, holding her shawl tightly together,—“and—and I want—something up-stairs.”

Straight to the spare chamber she hurried, and unpinned her shawl. The necklace was gone. She looked on the floor, on the stairs, shook her shawl and wrung her hands; but it was surely gone. It was there when she left Mrs. King’s. If she had only put it in her pocket! but she was afraid Nettie Rand would laugh. She couldn’t go back. Would anybody find it? Should she ever see it again?

She went slowly down to the parlor.

“It’s very strange,” mamma was saying, “Katy has been with us too long to doubt her honesty, but this new second-girl,—it must be. Of course the chain could not go off without hands. I took the poor girl out of pity, and she has seemed so anxious to please. Oh dear! there’s no knowing whom to trust.”

Bell slid into a chair, pale and trembling. So Cousin Mate had missed her chain, and thought the new girl had taken it. Her first feeling was one of relief. Then she wondered if they would send the poor girl to states-prison, and what the end of it would be.

“You are all tired out, aren’t you, dear? playing so hard,” remarked her mother, by and by. “You had better go straight to bed.”

Cousin Mate offered to go up with her as she often had of late. Bell talked as fast as she could, pulling off half her boot buttons in her haste. As she stood up to have her dress unfastened, something slid to the floor,—something bright and shining; and there it lay,—the necklace, telling its own story. Bell sank in a little tumbled heap beside it, covering her face with both hands.

“Oh, my little Bell! would you have sold yourself for that?” asked Cousin Mate, dropping down in turn beside her, and drawing the whole little heap into her lap. “Would you have sold yourself for that?” she repeated, uncovering the shame-stricken eyes with one hand, and holding up the necklace with the other.

“Sell myself!” echoed Bell, wonderingly.

“Yes; you know Satan is always trying to make bargains with us. Did you stop to think how much you paid him for this? First, that most precious of all gems—Truth, which you can wear forever in Heaven, while this, you know, moth and rust can corrupt, and thieves steal away from you. And then did you forget, Bell, that this sin, unrepented of, could shut you out of heaven? Would you give up that beautiful home for this poor little trinket, my darling? And didn’t you forget, too, that God was looking down upon you, so grieved and sorry? Wasn’t it a very poor bargain, dear? Would you take the necklace for your very own at such a price?”

“No, no! I never want to see it again,” sobbed Bell. “Oh! what shall I do?”

“I will tell you what God said once to his disobedient people,” said Cousin Mate, softly: “‘Ye have sold yourselves for nought,’ ‘Ye shall be redeemed without money.’ You know how He ‘redeemed’ them, Bell, and Who it is that ‘was wounded for our transgressions.’”

And Enoch walked with God and he was not; for God took him.

Miss Cox, Sue’s Sabbath School teacher, was absent, and Miss Marvin, Bell’s cousin, heard the class. Bell was in it, and Nettie Rand, Jenny King, Sarah Ellis, Dick Vance, Robert Rand, Varney Lowe, and Will Carter,—five girls and four boys. The lesson was on Elijah, and the boys were exceedingly interested in speculations about the chariot of fire, its probable appearance, and did Miss Marvin think Enoch had a chariot too?

“It seems the writer of Enoch’s memoir thought that of very little importance; at least, he said nothing about it,” rejoined Miss Marvin, smiling. “But then he only used fifty-three words any way; and yet how much we seem to know about Enoch. Did you ever think of it?”

“Memoirs are awfully stupid; most always there’s three volumes,” said Varney Lowe.

“Paul wrote the second volume of Enoch’s,” said Miss Marvin. “You will find it in Hebrews, eleventh chapter, fifth verse. But there are only thirty-two words in that.”

“It doesn’t say much in Genesis,” said Jenny King, who had opened her Bible, “only how long he lived and that Methuselah was his son.”

“And that God took him,” added Sarah Ellis, who had opened her Bible too.

“One other and best thing of all, twice repeated,—don’t you see it?” asked Miss Marvin.

“Oh, yes; that ‘he walked with God’; but I never could understand really what it meant.”

“What is the first thing necessary when two people walk together?”

“To keep step,” answered Will Carter, who was captain of the “Young Rangers.”

“And to do that they must be agreed, mustn’t they? have one common impulse, do the same thing.”

“But we can’t do what God does,” said Sarah Ellis, in a tone of surprise.

“Can’t we? What does God do?”

“Why, he makes everything and keeps making it beautiful, and takes care of everything and everybody.”

“And isn’t that what he wants us to do? to help beautify this world of his, just the little bit right around us, helping ourselves and others up into better things as fast and as far as we can? I think that was what Enoch did. What else is necessary for people to walk happily together?”

“They must like the same things,” said Dick, “or they won’t have anything to talk about.”

“Very true: Enoch must have loved what God loved, and so should we. God loves truth and holiness, everything pure and noble and good, and he hates sin. What next?”

“They must love each other,” suggested Sue.

“Yes, indeed; two will never walk together long unless they love one another. God loves everybody, and Enoch must have loved God or he couldn’t have walked with him. God said to those who refused to walk in his ways, ‘All day long have I stretched forth my hand, but no man regardeth.’ That reminds me of what I saw coming to church this morning. A gentleman was walking across the fields, with a dear little yellow-haired boy beside him, who tried his best to take as long steps as his father.”

“I most know it was Tod,” whispered Sue.

“You all know the stepping-stones across the marsh where the mud is so black,” continued Miss Marvin. “The stones are some ways apart, and the little fellow drew back doubtfully; but after a while, taking hold of his father’s hand, he began jumping from one to the other. Perhaps you remember a little stream of water trickles between the last two stones, and there he stopped again. His father smiled, and held out his other hand, and without waiting a second the boy seized hold of it and sprang across, straight into his father’s arms. I saw the gentleman hold him tightly, and give him half a dozen kisses before he set him down. He was so glad, you see, to have his little son trust him so entirely. Now, it seems to me that is the way Enoch ‘walked with God.’ Paul says ‘he pleased God,’ and I think it was because he trusted Him, just as that little boy did his father. God is our father, you know, strong and wise enough to lead us.”

Tinkle, tinkle went the superintendent’s bell.

“I wish you’d hear our class next Sabbath,” said Dick. “Miss Cox never tells us anything only what’s in the book.”

“There is more in the book than we can ever learn,” said Miss Marvin, pleasantly. “We want to help each other find out what it means and obey it. I’ll tell you what I will do. If you will all come to Bell’s next Saturday night we will study the lesson together,—as many as would like to, I mean.”

“May I come?” asked Maybee, who had stopped to wait for Sue.

“Yes, indeed, the more the better; and I’ve a pretty bit of poetry perhaps you will like to learn. Now, good-by.”

“Don’t you think—does it seem quite fair—you know it would be so much nicer to go up in a chariot than to be sick and die; and to think only just two! Shouldn’t you like it better?” asked Sarah Ellis, lingering till the others were all gone.

Miss Marvin glanced out at the open door, from which the elegant carriage belonging to the child’s uncle, Esquire Ellis, had just driven away, then back to the faded muslin dress and plain straw hat beside her. Sarah’s mother was a widow, and supported herself and daughter by doing fine sewing.

“We must remember this,” she said, slowly, looking down into the uplifted eyes: “if we really trust God he will surely lead us by the very best way to himself; and when we are with him up there it will make little difference how he took us from down here.”

“I must send her my ‘Brown-Haired Bess’ that I’ve promised Maybee,” said Miss Marvin to herself, as Sarah walked thoughtfully away. “I believe the ‘hidden life’ is beginning to show in that sweet, earnest face.”

“They said, The spirit of Elijah doth rest on Elisha.” 2 Kings 2:15.

“But God is the judge; he putteth down one, and setteth up another.”

A hard, driving, northeast storm. No hope of its breaking away at noon; no getting out with water-proof and rubbers, even; no Sabbath School,—“nothing but a great, long, dull, tiresome day,” Sue said, sitting down to breakfast with a face as cloudy as the sky.

“’Thout papa preaches, and mamma sings, and we make-believe meeting it,” rejoined Maybee, inclined to find a bright side.

Around the breakfast-table on Sabbath mornings, everybody at Mr. Sherman’s was expected to recite a text of Scripture, and that morning it happened papa and Maybee had chosen the same one: “But God is the judge; he putteth down one, and setteth up another.”

“Suppose,” said papa, “we take that for a text, and write a sermon,—Sue, Maybee, and I; Sue, with her Concordance, shall look out in the Bible the sort of people God ‘putteth down’ and ‘setteth up’; and Maybee, with mamma’s help, shall find the names of some of them. Then, when I come back from morning service, we’ll put our heads together and make an application.”

What a short forenoon it seemed! Right after lunch they were to meet in the library. Maybee drew a big chair behind papa’s desk for a pulpit, and placed the chairs in rows for the pews. Then it occurred to her, with mamma for choir, there was nobody left for congregation, and she coaxed Bridget in from the kitchen, rather against that individual’s inclination.

First they sang the Sabbath School hymn, “Better than thrones”; then papa prayed a short prayer, so simple Maybee could understand every word, after which he gave out the text, and called upon Sue for her part of the sermon. Sue had it neatly written out, and read,—

| GOD IS THE JUDGE. | |

|---|---|

| Those that walk in pride he is able to abase. | Yet setteth he the poor on high from affliction, and maketh him families like a flock. |

| He casteth the wicked down to the ground. | The Lord lifteth up the meek. |

| Thine heart was lifted up because of thy beauty; thou hast corrupted thy wisdom by reason of thy brightness: I will cast thee to the ground. | Humble yourselves in the sight of the Lord, and he shall lift you up. |

| There are the workers of iniquity fallen: they are cast down, and shall not be able to rise. | Because he hath set his love upon me, therefore will I deliver him. I will set him on high, because he hath known my name. |

| For the arms of the wicked shall be broken. | But the Lord upholdeth the righteous. |

“Very well. Now, Maybee.”—

And Maybee counted off on her fingers, carefully using her right hand for the good men, “Jacob, Joseph, Moses, David, Solomon”; and then with her left hand, “Pharaoh, Saul, Jeroboam,—and—and—I can’t think, but lots of little bits of kings what wouldn’t mind him.”

“Does the text mean God always promotes the good and puts down the wicked?” asked papa.

“Oh, it can’t,” returned Sue, “because there’s Esq. Ellis, ever so rich, and he never goes to church; and Say Ellis’s mother is real poor, and just as good as she can be. And you know Varney Lowe’s father has failed, and everybody calls him good.”

“They don’t live in the Bible,—that’s why,” said Maybee. “God put all my wicked folks right down, and let all the good ones have real nice times.”

“How was it with poor David when he was hiding away from Saul?”

“Oh, I see!” cried Sue. “It means He will, sometime; but”—and her face clouded again—“there’s Aunty McFane, just as patient and good; she’s always had dreadful times, and she’s so old she can’t live a great while longer.”

“God may not think best to ‘lift her up,’ till he takes her to himself,” observed mamma.

“Then we can’t tell anything about it, now, as they did in the Bible.”

“Don’t you remember when we went to the review of troops,” said her father, “we couldn’t see any order or reason in all the marching and counter-marching; but there was the General on horse-back, with all the whys and wherefores in his mind. We could see it a little more plainly after we climbed that high hill, and looked right down upon them. And so when we ‘get up higher,’ we may know more of God’s plans than we do down here. Meanwhile, the text is to teach us, that he is the great Commander and Judge, doing just what he pleases with his creatures. It is for us to trust he will work out the very best plan possible.”

“I can’t just see why he lets good folks have any bad times,” said Maybee.

“Once, when you and Tod were very little, you were making mud-pies in the garden, having a splendid time; and Aunt Sue came and took Tod away to be washed and dressed. They were all going to a picnic on Beech Island, where he would have ever so much more fun; but the poor little fellow couldn’t understand that, and screamed and cried all the time they were getting him ready.”

“Getting ready’s horrid, anyway,” said Maybee.

“Oh no,” said Sue, “not if we keep thinking of what is going to be.”

“That’s it,” said papa. “And we are put into this world to ‘get ready’ for heaven. You know we must be washed in the blood of Christ and clothed with his righteousness before we can enter that beautiful land, and when God takes anything from us that would hinder our getting ready, we need not mind when we think of what is ‘going to be.’ I remember, too, how afraid Tod was that day, of the cars and boat, and how he fretted because Uncle Thed wouldn’t let him walk instead of carrying him over the sand and rocks. So we often grumble at things in our lives,—things God means shall help us along faster towards heaven. We are always wanting to try our own ways.”

“Just as I did the time Maybee was lost,” said Sue. “I think I shall always be sure mother knows best, now.”

“And that is a long step towards trusting our Father in heaven,” said papa pleasantly.

“Oh, oh! see the sun!” cried Maybee; “and there’s Uncle Thed and Tod going home from church.”

“Guess my new wubber boots wasn’t afwaid of the wain,” said Tod, running in and holding up one foot triumphantly. “We comed over the stepping-stones, too. Oh, my! an’ the mud’s all water, now; covers ’em most up.”

“Those stepping-stones are just a nuisance,” remarked Sue. “I wish they’d build a nice plank walk over the marsh.”

“My don’t,” said Tod. “It’s weal fun to take tight hold of papa’s hand and let him step you wight along.”

Uncle Thed lifted Tod on his knee.

“Were you having a meeting here, and isn’t it through?” he asked.

“We were just seeing how far we’d got to heaven; I mean, how was the best way,” said Maybee. “And Sue was so frightened when Tod and me was lost, she won’t never do so again. That’s a step, you know.”

“Dick an’ me isn’t never going to say ‘By funder’ no more, neither,” said Tod complacently.

“Isn’t Dick just as different as can be?” said Sue. “Only think, mamma, if you hadn’t gone into Aunty McFane’s that day—”

“Oh, yes,” put in Maybee, “I’m going always to b’lieve God takes care of everybody when they ask him.”

“And how little squirrels ought to mind their masters, and boys too, my guesses,” added Tod, reminded of Aunty McFane’s story.

“Dick told Miss Marvin the other Sabbath,” said Sue, “that he wished everybody knew what a good master God was. Will Carter laughed, and coming home he asked Dick how many prayers he said a day. I know Dick was real angry, he turned so red and then white, and he didn’t speak for ever so long. Then he asked Will if he didn’t like to ask his father for things he wanted, and why one need to be any more ashamed of praying. Say Ellis said she wished she could walk with God the way Miss Marvin said it meant. Do you believe children can?”

“Why not?” said Mr. Sherman, “if they do as Tod does about the stepping-stones,—take fast hold of God’s hand and let him lead them.”

“And then they’ll be like ‘Brown-Haired Bess,’ and folks’ll know they’re ’quainted with Jesus,” said Maybee.

“Guess they’d better have their own papa,” put in Tod. “Ain’t any use to ask th’ other folks.”

“Exactly,” said Maybee’s papa. “Now let’s sing ‘Nearer, my God, to thee,’ and dismiss our meeting.”

While they were putting back the chairs Maybee told her mother what Miss Marvin had said about the stepping-stones, and how it must have been Uncle Thed and Tod, because she saw Uncle Thed hug Tod to-day when he told about them.

“Don’t you s’pose,” said Maybee thoughtfully, “that’s why God has stepping-stones up to heaven ’stead of a plank walk?”

“And God is able to make all grace abound toward you; that ye, always having all sufficiency in all things, may abound to every good work.”

Miss Cox had found a destitute family down by the Mills, and enlisted the girls of her Sabbath School class to provide suitable clothing, in which the children could come to church.

They were to meet at her house Saturday afternoon to sew, having, the Sabbath before, brought what money they could to purchase material. Bell Forbush had given a whole dollar, while poor Sarah Ellis shook her head sorrowfully when asked for her mite.

“But you will come and sew, and that will do just as well,” said Miss Cox, putting down twenty-five cents for Sue Sherman.

“I gave every bit of my pocket-money,” whispered Bell to Sue; “but, you see, Cousin Mate will give me some more if I just ask her; for, don’t you think, she’s going to stay all summer, and she has such lots of money she’s always giving me some.”

Sue was more than half inclined to envy Bell this stroke of good luck in the shape of a rich cousin. She quite envied her the next Saturday afternoon. It sounded so grand for Bell to say whenever anything was found to be lacking, “O Miss Cox! I will give that. I’ll run right over to the store this minute.”

Buttons, trimmings, handkerchiefs, hair-ribbons, even,—“I had no idea we should make out such complete outfits, and so pretty,” said Miss Cox, “and we shouldn’t but for you, Bell.”

“Bell will certainly become bankrupt if she keeps on,” said Jenny King.

“Not while she has a rich cousin to go to,” said Nettie Rand, in her provoking way.

Bell colored, but had the readiness to say frankly, “that’s the secret of it. Cousin Mate wants me to be benevolent, and has promised to find all the money I need.”

“Great way of being benevolent, that is!” said Nettie, tossing her head.

“It’s doing good just the same,” rejoined Sue, standing up for her friend, “only it must be real nice and easy to know whatever you want is to be had just for the asking.”

Say Ellis looked up with a bright smile, but she said nothing.

“We are very much obliged to Miss Marvin and to Bell too,” remarked Miss Cox, basting away on the last little sacque. “The younger ones are all provided for now, but there’s an older girl. I can’t even get a chance to speak to her yet; folks say she’s a wild, high-flyer of a thing, with an ugly temper, and that she uses dreadful language. I don’t know as we can do anything—”

“Oh! that Tryphosa Harte,” interrupted Nettie. “She’s perfectly horrid. It’s that girl who stood on the steps and mimicked us, the other night, Bell.”

“She’s just about your size, isn’t she?” resumed Miss Cox; “and I was thinking, if each of you should give her something of your own,—things you had done wearing of course, but tasty and like other people’s, dress her up real pretty, you know,—and all take some sort of interest in her, we might get her into Sabbath School and help her be somebody. They say she’s uncommonly smart.”

“But, Miss Cox, she makes all manner of fun of anything good. I’ll ask mother to give her my last summer’s sacque, but I shouldn’t dare speak to her,” exclaimed Sue.

“I could give her one of my cambric dresses and I dare say Cousin Mate would get her a hat, but she’s so disagreeable I never want to go near her,” said Bell.

“It wouldn’t be a bit of use, I know,” put in Nettie Rand. “She’d only laugh in our faces the minute we said Sabbath School to her; and I think it’s hard work enough to ask folks to be good when they treat you decent. I dare say father would give her a pair of shoes, but they’d never walk into church, I’m sure of that.”

“I should call it casting pearls before swine,” laughed Jenny King. “Please, Miss Cox, don’t set us to driving any but little pigs into Sabbath School: you can coax round them easy, but that Tryphosa Harte,—it would take the meekness of Moses to begin with, and the patience of Job to hold out. I know meekness and patience and perseverance are nice things to have, but, you see, none of us has a rich cousin to keep us supplied with that sort of pocket-money.”

Again Say Ellis looked up, with a flash of sunshine in her mild, blue eyes, and this time she spoke:—

“I’d like—to try, Miss Cox. I never spoke to her but once, and then she threw mud at me, but I could—try; and I’d like—to give something. Would a pair of stockings—”

“Yes, indeed; she’ll need everything, I suppose,” said Miss Cox warmly. “If you would try, Sarah dear. I have an idea one of you would succeed much better than I.”

“Whatever did you offer for?” asked Jenny King, as she and Sarah walked home together. “It will be just a waste of kindness.”

“But if there’s plenty more to be had, we needn’t mind,” said Say, smiling.

Jenny stared, and then said slowly, “But I do mind having a dirty, ragged thing like that turn up her nose at me. You just try how it feels a few times, and—”

“But don’t you know—I was thinking—I’m sure it’s something like,” stammered Say.

“What are you getting at?” laughed Jenny good-naturedly, as they stopped before the gate of the small cottage where Sarah lived.

“Why, you said we hadn’t any rich cousin to give us patience and meekness, and I thought, wasn’t God a great deal better, because, you know, it was in our Sabbath School lesson,—Whatsoever we ask, He can give it to us. Only think,—whatsoever!”

“Yes, but I never thought of taking it so, really.”