ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY.

| Page | |

| THE CEDAR WAXWING. | 193 |

| THE PREACHER-BIRD. | 194 |

| COFFEE. | 197 |

| AN ABANDONED HOME. | 198 |

| THE CONY. | 203 |

| COFFEE. | 204 |

| THE TWO ACORNS. | 210 |

| A DEFENSE OF SOME BIRDS. | 211 |

| MARCH AND MAY. | 212 |

| BONAPARTE'S GULL. | 215 |

| EGG COLLECTING. | 216 |

| THE BABOON. | 217 |

| THE SUMMER POOL. | 218 |

| THE FEATHER CRUSADE. | 221 |

| GOD'S SILENCE AND HIS VOICES ALSO. | 222 |

| THE OWLS' SANCTUARY. | 223 |

| THE WATER THRUSH. | 227 |

| THE TARSIER. | 228 |

| THE TRAILING ARBUTUS. | 229 |

| THE HAIRY-TAILED MOLE. | 230 |

| TREES. | 233 |

| THE CINERARIA. | 236 |

| INDEX VOL. V. | |

| INDEX VOLS. I., II., III., IV., V. | i |

LYNDS JONES.

THERE is no more beautiful bird in our northern states, if there be in the whole country, than our waxwing. Many birds are more gorgeously appareled, and with many there are more striking contrasts exhibited, but nowhere do we encounter a texture more delicate covering a bearing more courtly. One despairs of adequately describing the silky softness of the plumage and the beautiful shades of color. But the perfecting of color photography has made that task unnecessary. We may wonder why some crested birds have this regal insignia bestowed upon them by nature, but it would be impossible to think of the waxwing without his crowning glory. Not less characteristic are the horny appendages resembling red sealing wax attached to the secondary wing feathers and sometimes also to the tail feathers. They seem to be outgrowths of the tip of the shaft. These, with the yellow-tipped tail, form the only bright colors in the plumage.

The cedar waxwings are gregarious, except during the breeding-season, wandering about the country in flocks of a dozen individuals, more or less, stopping for any considerable time only where food is plentiful. Their wandering propensities make their presence a very uncertain quantity at any season of the year. During the whole of 1898 they were present in considerable numbers at Oberlin, Ohio, nesting in orchards and shade trees plentifully, but thus far in 1899 very few have been seen. No doubt their presence is not suspected even when they may be numerous, because they do not herald their appearance with a loud voice nor with whistling wing. Their voice accords perfectly with their attire, their manners are quiet and unassuming, and their flight is well-nigh noiseless. One moment the flock is vaulting through the air in short bounds, the next its members are perched in a treetop with erected crests at attention. If all is quiet without cause for suspicion, the flock begins feeding upon the insect pests, if they are in season; upon the fruit, if that is in season. So compact is the flock, both in flight and while resting, that nearly every member might be taken at a single shot. The birds are so unsuspicious that they can easily be approached, thus presenting a tempting prize to the small hunter who may design the beautiful plumage for some hat decoration.

In common with the goldfinch, the waxwings are late breeders, making their nests in June, July, and August. They seem to prefer rather small trees and low ones, nesting in orchard trees and in ornamental shrubbery as well as in shade trees. The nest is not usually an elaborate affair, but rather loosely made of twigs, grass, rootlets, and leaves, often lined with grape-vine bark, thus hinting that the species has sprung from an original tropical stock, which necessarily makes its nest as cool and airy as practicable. The eggs are unique among the smaller ones, in their steely bluish-gray ground, rather evenly overlaid with dots and scratches of dark brown or black, thus presenting an aggressiveness out of all harmony with the birds. But the peculiar colors and pattern aid greatly in rendering the eggs inconspicuous in the nest, as anyone may prove by noticing them as they lie on their bed of rootlets or leaves. They are usually four in number [Pg 194] in this locality, but may vary somewhat according to the season and individual characteristics.

The food of the waxwing is varied both according to season and other conditions. Wild fruit, berries, and seeds form much of their food during the fall and winter months. Mr. A. W. Butler states that, "in winter nothing attracts them so much as the hack-berry (Celtis occidentalis). Some years, early in spring, they are found living upon red buds." The investigations of the food of this species by Professor F. E. L. Beal prove that the greater share of it consists of wild fruit or seeds with a very small allowance of cultivated fruits. Animal matter forms a relatively small proportion of the food, but this small proportion by no means indicates the insect-feeding habits of the birds. It might well be suspected that so varied a diet would enable the birds to accommodate themselves to almost any conditions, largely feeding upon the food which happens to be the most abundant at the time. Thus, an outbreak of any insect pest calls the waxwings in large flocks which destroy great numbers to the almost entire exclusion of fruit as a diet for the time. It cannot be denied that the waxwings do sometimes destroy not a little early fruit, calling down upon them righteous indignation; but at other times they more than make amends for the mischief done.

Of the voice Mr. A. W. Butler says, "They have a peculiar lisping note, uttered in a monotone varying in pitch. As they sit among the branches of an early Richmond cherry tree in early June, the note seems to be inhaled, and reminds me of a small boy who, when eating juicy fruit, makes a noise by inhalation in endeavoring to prevent the loss of the juice and then exclaims, 'How good!' As the birds start to fly, each repeats the note three or four times. These notes develop into a song as the summer comes on; a lisping, peculiar song that tells that the flocks are resolving into pairs as the duties of the season press upon them." After the pairing season there is a great show of affection between the two birds, which often continues long after the nesting season has closed.

JENNY TERRILL RUPRECHT.

LISTEN near a grove of elms or maples and you will not fail to hear its song, a some what broken, rambling recitative, which no one has so well described as Wilson Flagg, who calls this bird the preacher, and interprets its notes as "You see it! You know it! Do you hear me? Do you believe it?"—Chapman's Bird-Life.

|

||

| FROM COL. F. M. WOODRUFF. | CEDAR WAXWING. 5/7 Life-size. |

COPYRIGHT 1899, NATURE STUDY PUB. CO., CHICAGO. |

ANNA R. HENDERSON.

COFFEE is a native of Abyssinia, being first used by the natives of the district called Kaffa, whence its name. It is still found wild in parts of Africa.

It was introduced into Arabia in the fifteenth century, and is so well suited to that soil and climate that the Mocha coffee has never been excelled. It became so popular that in 1638 the Mohammedan priests issued an edict against it, as the faithful frequented the coffee shops more than the mosques.

In 1638 the beverage was sold in Paris, but did not win favor for a few years until it was introduced to the aristocracy by Soliman Aga, the Ambassador of the Sublime Porte at the Court of Louis XIV. Coffee sipping became fashionable, and before the middle of the seventeenth century was the mode in all the capitals of Europe.

Cromwell ordered the closing of the coffee shops of England, but its popularity did not wane.

In 1699 coffee was planted in Batavia and Java. In 1720 three coffee shrubs were sent from the Jardin des Plantes in France to the Island of Martinique.

The voyage was long, and water becoming scarce two of the plants perished, but Captain Declieux shared his ration of water with the other plant, and it lived to become the ancestor of all the coffee groves in America.

On the coat of arms of Brazil which adorns every flag of that country is a branch of coffee, a fit emblem, as Brazil produces three-fourths of the coffee of the world. It was first planted there in 1754, and the first cargo was shipped to the United States in 1809.

It can be grown from seeds or from slips. Shrubs begin bearing the second or third year, and are profitable for fifteen years, some trees continue bearing for twenty-five years.

They are planted six or eight feet apart, and not allowed to grow more than twelve feet high; and are not pruned, so that the limbs bend nearly to the ground. The long slender drooping branches bear dark green, glossy leaves, directly opposite to each other. Between these leaves bloom the flowers; clusters of five or six white star-shaped blossoms, each an inch in diameter. These jessamine-like flowers touch each other, forming a long snowy spray bordered with green. Nothing can exceed the beauty of a coffee grove in bloom, and its fragrance makes it a veritable Eden.

It is beautiful again when the berries are ripe. They resemble a large cranberry, each berry containing two grains, the flat sides together. The fruit is slightly sweet but not desirable. Three crops are gathered in one year. I have in memory a coffee plantation in the mountains of Brazil, where the pickers were African slaves. They made a picturesque sight, picking into white sacks swung in front of them, occasionally emptying the fruit into broad, flat baskets. Each man will pick more than thirty pounds a day, and at sunset they wind down the mountain paths with their broad baskets of red berries balanced on their heads.

The ripe fruit is put through a mill which removes the pulp. The wet berries are then spread to dry in the sun on a floor of hardened earth, brick or slate.

The coffee terrane in my memory was about eighty feet square, laid with smooth slate, and slightly sloping. It had around it a moulding of plaster with spaces of perforated zinc for the escape of water. Orange and fig trees dropped their fruit over its border and it was an ideal spot for a moonlight dance. The coffee house was near, and an approaching cloud was a signal to gather the coffee in.

When dry the grains are put through a mill, or where primitive methods prevail, pounded in a mortar to remove a thin brittle shell which encloses each grain. The coffee is then put into sacks of five arrobas, or 160 pounds each and carted to the warehouses of the city.

BY ELANORA KINSLEY MARBLE.

CHAPTER II.

"WELL, I'm glad to get over to this tree again out of the sound of mother's voice. Duty to my husband; that's all she could talk about. All wives help to build the home-nest," she says, "and indeed do the most toward making it snug and comfortable, and that I must give up my old pastimes and pleasures and settle down to housekeeping. Well, if I must, I must, but oh! how I wish I had never got married."

Not a word was exchanged between the pair that night, and on the following morning Mrs. B., with a disdainful toss of her head, ironically announced her willingness to become a hod-carrier, a mason, or a carpenter, according the desires of her lord.

They elected to build their nest in the maple-tree, and you can imagine the bickerings of the pair as the house progressed. Mrs. B's. groans and bemoaning over the effect, such "fetchings and carryings" would have upon her health, already delicate. How often she was compelled from weakness and fatigue to tuck her head under her wing and rest, while Mr. B. carried on the work tireless and uncomplaining.

"She may change when she has the responsibility of a family," he mused, "and perhaps become a helpmeet after all. I must not be too severe with her, so young and thoughtless and inexperienced."

So the nest at length was completed.

"My!" said a sharp-eyed old lady bird, whose curiosity led her to take a peep at the domicile one day while Mrs. B. was off visiting with one of her neighbors, "such an uncomfortable, ragged looking nest; it is not even domed as a nest should be when built in a tree. And then the lining! If the babies escape drowning in the first down-pour, I am sure they'll be crippled for life, if not hung outright, when they attempt to leave the nest. You know how dangerous it is when they get their feet entangled in the rag ravelings and coils of string, and if you'll believe me that shiftless Jenny has just laid a lot of it around the edges of the nest without ever tucking it in. The way girls are brought up now-a-days! Accomplishments indeed! I think," with a sniff, "if she had been taught something about housekeeping instead of how to arrange her feathers prettily, to dance and sing, and fly in graceful circles it would have been much better for poor Mr. B. Poor fellow, how I do pity him," and off the old lady flew to talk it over with another neighbor.

Unlike some young wives of the sparrow family, Mrs. B. did not sit on the first almost spotless white egg which she deposited in the nest, but waited till four others, prettily spotted with brown, and black, and lavender lay beside it.

"Whine, whine from morning till night!" cried her exasperated spouse after brooding had begun. "Sitting still so much, you say, doesn't agree with you. Your beauty is departing! You are growing thin and careworn! The little outings you take are only tantalizing. I am sure most wives wouldn't consider it a hardship to sit still and be fed with the delicious grubs and dainty tidbits which I go to such pains to fetch for you. That was a particularly fine grub I brought you this morning, and you ate it without one word of thanks, or even a look of gratitude. Nothing but complaints and tears! It is enough to drive any husband mad. I fly away in the morning with a heavy heart, and when I see and hear other sparrows hopping and singing cheerfully about their nests, receiving chirps of encouragement and [Pg 199] love from their sitting mates in return, I feel as though—as though I would rather die than be compelled to return to my unhappy home again."

"Oh, you do?" sarcastically rejoined Mrs. B. "That is of a piece with the rest of your selfishness, Mr. Britisher, I am sure. Die and leave me, the partner of your bosom, to struggle through the brooding season and afterward bring up our large family the best I may. Oh," breaking into tears, "I wish I had never seen you, I really do."

"Oh, yes, that has been the burden of your song for days, Mrs. B. I'm sure I have no reason to bless the hour I first laid eyes on you. Why, as the saying goes, Mrs. B., you threw yourself at my head at our very first meeting. And your precious mamma! How she did chirp about her darling Jenny's accomplishments and sweet amiability. Bah, what a ninny I was, to be sure! Oh, you needn't shriek and pluck the feathers from your head. Truth burns sometimes, I know, and—oh you are going to faint. Well faint!" and with an exclamation more forcible than polite Mr. B. flew away out of sight and sound of his weeping spouse.

Wearily and sadly did Mrs. B. gaze out of her humble home upon darkening nature that evening. Many hours had passed since the flight of Mr. B., and the promptings of hunger, if nothing else, caused her to gaze about, wistfully hoping for his return. The calls of other birds to their mates filled the air, and lent an additional mournfulness to her lonely situation.

"How glad I shall be to see him," she thought, her heart warming toward him in his absence. "I'll be cheerful and pretend to be contented after this, for I should be very miserable without him. I have been very foolish, and given him cause for all the harsh things he has said, perhaps. Oh, I do wish he would come."

Night came down, dark and lonely. The voices and whirrings of her neighbors' wings had long since given place to stillness as one after another retired for the night. The wind swayed the branches of the tree in which she nested, their groanings and the sharp responses of the leaves filling the watcher's mind with gloomy forebodings.

"I am so frightened," she murmured, "there is surely going to be a storm. Oh, I wish I had listened to Mr. B. and not insisted upon building our home in the crotch of this tree. He said it was not wise, and that we would be much safer and snugger under the eaves or in a hole in the wall or tree. But, no, I said, if I was compelled to stay at home every day and sit upon the nest it should be situated where I could look out and see my neighbors as they flew about. That was the reason I was determined it should not be domed. I wanted to see and be seen. Oh, how foolish I have been! What shall I do? What shall I do? I am afraid to leave the nest even for a minute for fear the eggs will get cold. Mr. B. would never forgive me, then, I am sure. But to stay out here in the storm, all alone. Oh, I shall die, I know I shall."

Morning broke with all nature, after the rain, smiling and refreshed. Sleep had not visited the eyelids of the forsaken wife and with heavy eyes and throbbing brain, she viewed the rising dawn.

"Alas," she sighed, as the whirr of wings and happy chirps of her neighbors struck upon her ears, "how can people be joyous when aching hearts and lives broken with misery lie at their very thresholds? The songs and gleeful voices of my neighbors fill me with anger and despair. I hate the world and everybody in it. I am cold and wet and hungry. I even hate the sun that has risen to usher in a new day.

"I must make an effort," she murmured as the morning advanced and Mr. B. did not return, "and get home to mother. I am so weak I can scarcely stand, much less fly. I am burning with fever, and oh, how my head throbs! Such trouble and sorrow for one so young! I feel as though I shall never smile again."

She steadied herself upon the edge of the nest and, turning, gazed wistfully and sadly upon the five tiny eggs, which she now sorrowed to abandon.

"I may return," she sighed, "in time [Pg 200] to lend them warmth, or may find my dear mate performing that office in my absence. I will pray that it may be so as I fly. Praises would be mockery from my throat to-day, mockery!"

"Why, Jenny!" shrieked her mother as Mrs. B. sank down exhausted upon the threshold of her old home. "Whatever is the matter with you, and what has brought you here this time of day?"

"I am hungry and sick, mother, and I feel as though, as though—I am going to die!"

"And where is Mr. Britisher? You've no business to be hungry with a husband to care for you," tartly replied her mother, whilst bustling about to find a grub or two to supply her daughter's wants.

"I have no husband, I fear, mother. He is—"

"Dead!" shrieked the old lady. "Don't tell me Mr. Britisher is dead!"

"Dead, or worse," sadly replied her daughter.

"Worse? Heaven defend us! You don't mean he has deserted you?"

"He left me yesterday afternoon in anger, and has not returned."

"Highty, tighty, that's it, is it? Well, you have brought it all upon yourself and will have to suffer for it. I am sure your father talked enough about idleness and vanity for you to have heeded, and time and time again I have told you that every husband in the sparrow family is a bully and a tyrant, and every wife, if she expects to live happily, must let her mate have his own way."

Mrs. B. sighed, and wearily dropped her head upon her breast.

"You must go back," emphatically said her mother, "before the neighborhood gets wind of the affair. Mr. Britisher may be home this very minute, and glad enough he will be to see you, I am sure. So go back, dear, before the eggs grow cold and your neighbors will be none the wiser."

"I am going, mother, but oh, I feel so ill, so ill!" said the bereaved little creature as she wearily poised for her flight.

"She does look weakly and sick, poor thing," said the mother with a sigh watching her out of sight, "but I don't believe in interfering between husband and wife. Mr. Britisher, indeed, gave me to understand from the first that the less he saw of his mother-in-law the better, remarking that if that class would only stay at home and manage their own household affairs fewer couples, he thought, would be parted. I considered that a rather broad hint, and in consequence have never visited them since they began housekeeping. He has only gone off in a huff, of course, and everything will come out all right, I am sure."

Ere nightfall, however, motherly anxiety impelled her to fly over to her daughter's home.

Alas, only desolation and ruin were there. At the foot of the tree lay the form of Mrs. B. Exposure, sorrow, and excitement had done their work. It was a lifeless form which met her tearful gaze.

The fate of Mr. Britisher was never known. Rumor assigned his absence to matrimonial infelicity, but his more charitable neighbors, as they dropped a tear to his memory, pictured his mangled form a victim to the wanton cruelty or mischievous sport of some idle boy.

A gentleman passing by one day saw the dismantled nest upon the ground and carelessly stirred it with his cane.

"What is that, uncle?" queried a little maid of some five summers who walked by his side.

"That, little one," came the answer slowly and impressively, "is an abandoned home."

"An abandoned home," I repeated, as his words floated up to my window. "Aye, truly to the casual observer that is all it seems, but, oh, how little do they dream of the folly, the suffering, the sad, almost tragic ending of the wee feathered couple whom I saw build that humble home."

|

||

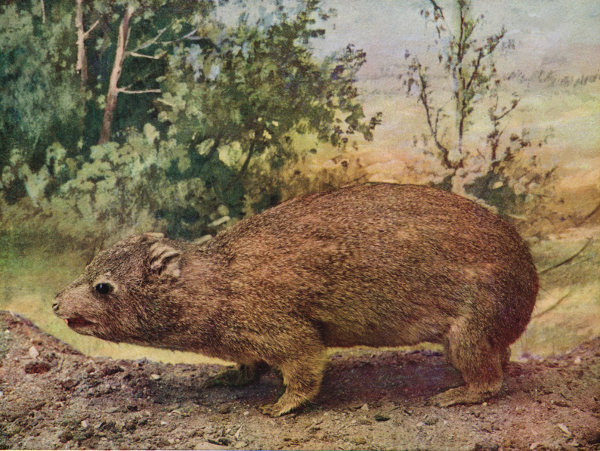

| FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES. 5-99 |

HYRAX. ¾ Life-size. |

COPYRIGHT 1899, NATURE STUDY PUB. CO., CHICAGO. |

C. C. M.

THE specimen of this animal presented here (Hyrax abyssinicus) is the best-known of the species. It measures from ten to twelve inches in length; the fur consists of somewhat long, fine hairs, gray-brown at the base, lighter gray in the middle portions, merging into a dark-brown surmounted by a light-colored tip, the resulting general color of this combination being a mottled pale-gray.

The Book of Proverbs, enumerating four animals which it describes as "exceeding wise," says: "The conies are but a feeble folk, yet they make their houses in the rocks." The conies are mentioned by various writers as well-known animals in days of remotest antiquity. They are found in the wild, desolate mountain regions of Africa and western Asia, and the variety inhabiting Syria and Palestine is probably referred to in the Hebrew text of the Bible under the name of "laphan," which Luther translated by the word, "rabbit," and in the authorized and revised versions is rendered "cony." They inhabit all the mountains of Syria, Palestine, and Arabia, perhaps also of Persia, the Nile country, east, west, and south Africa, frequently at elevations of six thousand or nine thousand feet above sea-level, and "the peaks and cones that rise like islands sheer above the surface of the plains—the presence of the little animals constituting one of the characteristic features of the high table-lands of northeastern Africa." It is stated that if the observer quietly passes through the valleys he sees them sitting or lying in rows on the projecting ledges, as they are a lazy, comfort-loving tribe and like to bask in the warm sunshine. A rapid movement or unusual noise quickly stampedes them, and they all flee with an agility like that usual among rodents, and almost instantly disappear. A traveler says of them, that in the neighborhood of villages, where they are also to be found, they show little fear of the natives, and boldly attend to their affairs as if they understood that nobody thinks of molesting them; but when approached by people whose color or attire differs from that of their usual human neighbors, they at once retreat to their holes in the rocks. A dog inspires them with greater fear than does a human being. When startled by a canine foe, even after they have become hidden, safe from pursuit, in their rocky crevices, they continue to give utterance to their curious, tremulous yell, which resembles the cry of small monkeys.

Brehm confirms the statement of another traveler, who called attention to the striking fact that the peaceable and defenseless cony lives in the permanent society and on the best of terms with a by no means despicable beast of prey, a variety of mongoose.

In regard to their movements and mental characteristics, the conies have been placed between the unwieldy rhinoceros and the nimble rodent. They are excellent climbers. The soles of the feet are as elastic and springy as rubber, enabling the animal to contract and distend the middle cleft or fissure of its sole-pad at will, and thereby to secure a hold on a smooth surface by means of suction. In behavior the conies are gentle, simple, and timid. The social instinct is highly developed in them, and they are rarely seen alone.

The conies have been regarded as the smallest and daintiest of all the existing species of odd-toed animals. Naturalists, however, have held widely divergent opinions as to the classification of the pretty cliff-dwellers. Pallas, because of their habits and outward appearance, called them rodents. Oken thought them to be related to the marsupials, or pouched animals. Cuvier placed them in his order of "many-toed animals," which classification has also been disputed, and Huxley has raised them to the dignity of representatives of a distinct order. Who shall decide where all pretend to know?

DR. ALBERT SCHNEIDER,

Northwestern University School of Pharmacy.

COFFEE is the seed of a small evergreen tree or shrub ranging from 15 to 25 feet in height. The branches are spreading or even pendant with opposite short petioled leaves, which are ovate, smooth, leathery, and dark green. The flowers are perfect, fragrant, occurring in groups of from three to seven in the axils of the leaves. The corolla is white, the calyx green and small. The ovary is green at first, changing to yellowish, and finally to deep red or purple at maturity. Each ovary has two seeds, the so-called coffee beans.

The coffee tree is a native of the tropical parts of Africa, in Abyssinia and the interior. The Arabians were among the first to transport it to their native country for the purposes of cultivation. From Arabia it was soon transplanted to other tropical countries.

The name coffee (Kaffee, Ger., Cafféier, Fr.) was supposed to have been derived from the Arabian word Kahwah or Cahuah, which referred to the drink made from the coffee beans as well as to wines. It is now generally believed that the word was derived from Kaffa, a country of the Abyssinian highlands where the plant grows wild very abundantly.

From Kaffa the coffee plant found its way into Persia about the year 875, and still later into Turkey. According to popular belief, the drink coffee was the invention of the Sheik Omar in 1258. Others maintain that the drink was not known until even a later period. The mufti, Gemal Eddin of Aden, made a trip to Persia in 1500, where he learned the use of coffee as a drink, and introduced it into his own country for the special purpose of supplying it to the dervishes to make them more enduring in their prayers and supplications. In 1511 coffee had already become a popular drink in Mecca. About this time Chair Beg, the governor of Mecca, issued an edict proclaiming coffee-drinking injurious and making the use of coffee a crime against the laws of the Koran. It was prophesied that on the day of judgment the faces of coffee drinkers would be blacker than the pot in which the coffee was made. As a result of this crusade the coffee houses were closed; the coffee plantations were destroyed, and offenders were treated to the bastinade or a reversed ride on a donkey. The next governor of Mecca again opened the coffee houses, and in 1534 Sultan Soliman opened the first coffee houses in Constantinople, which were, however, again closed by Sultan Murad II., but not for long. In 1624 Venetian merchants brought large quantities of coffee into northern Italy. In 1632 there were 1,000 public coffee houses in Cairo. In 1645 coffee-drinking had already become very common in southern Italy. A Greek named Pasqua erected the first coffee house in London (1652). Coffee houses appeared in other cities in about the following order: Marseilles, 1671; Paris, 1672; Vienna, 1683; Nürnberg and Regensburg, 1686; Hamburg, 1687; Stuttgart, 1712; Berlin, 1721. In 1674 the ladies of London petitioned the government to suppress the coffee houses. To discourage the use of coffee it was maintained that the drink was made from tar, soot, blood of Turks, old shoes, old boots, etc.

These coffee houses were of great significance, as may be gathered from the rapidity with which they spread and the general favor with which they [Pg 205] were received. They were visited, not so much on account of the drink that was dispensed there, but rather for the purpose of discussing political situations; they constituted the favorite meeting-places for anarchists, revolutionaries, and high-class criminals. At times it even became necessary to close them entirely in order to check or suppress political intrigues or plottings against the government. At the present time the saloons take the place of coffee houses in most countries, and many of them are still the hotbeds of anarchy and crime. In Turkey, where alcoholic drinks are prohibited, coffee houses have full swing.

The Dutch again seemed to have been the first to attempt the cultivation of the coffee plant. In 1650 they succeeded in transplanting a few trees from Mecca to Batavia. From 1680 to 1690 the island already had large plantations; others were soon started in Ceylon, Surinam, and the Sunda islands. About 1713 Captain Desclieux carried some plants to the French possessions of the West Indies (Martinique). It is reported that only a single plant reached its destination alive, which is the ancestor of the coffee trees of the enormous plantations of the West Indies and South America.

The plant thrives best in a loamy soil in an average annual temperature of about 27 degrees C., with considerable moisture and shade. Most plantations are at an elevation of 1,000 feet to 2,500 above the sea-level. In order to insure larger yields and to make gathering easier the trees of the South American plantations are clipped so as to keep their height at about 6 feet to 6.5 feet. The yield begins with the third year and continues increasingly up to the twentieth year. The fruit matures at all seasons, and is gathered about three times each year. In Arabia, where the trees are usually not clipped, and hence comparatively large, the fruit is knocked off by means of sticks. In the West Indies and South America the red, not fully matured fruit is picked by hand. The outer hard shell (fruit coat, pericarp) is removed by pressure, rolling, and shaking. The beans are now ready for the market.

All of the different varieties or kinds of coffee found upon the market are from two species of Coffea; namely, C. Arabica and C. Liberica; the latter yielding the Liberian coffee, which is of excellent quality.

There are a number of so-called coffees which are used as substitutes for true coffee, of which the following are the more important. California coffee is the somewhat coffee-like fruit of Rhamnus Californica. Crust coffee is a drink resembling coffee in color, made from roasted bread crusts steeped in water. Mogdad or Negro coffee is the roasted seeds of Cassia occidentalis, which are used as a substitute for coffee, though they contain no caffeine. Swedish coffee is the seeds of Astragalus Boeticus used as coffee, for which purpose it is cultivated in parts of Germany and Hungary. Wild coffee is a name given to several plants native in India, as Faramea odoratissima, Eugenia disticha, and Casearia laetioides. Kentucky coffee is a large leguminous tree (Gymnocladus Canadensis) of which the seeds (coffee nut) are used as a substitute for coffee.

The coffee beans are roasted before they are in suitable condition for use. At first the green beans were used. According to one story, a shepherd noticed that some of his sheep ate the fruit of the coffee tree, and, as a result, became very frisky. Presuming that the coffee beans were the cause, he also ate of the beans and noted an exhilarating effect. The use of the roasted beans was said to have originated in Holland. Roasting should be done carefully in a closed vessel in order to retain as much of the aroma as possible. This process modifies the beans very much; they change from green or greenish to brown and dark brown and become brittle; they lose about 15 to 30 per cent. of their weight, at the same time increasing in size from 30 to 50 per cent. The aroma is almost wholly produced by the roasting process, but if continued too long or done at too high a temperature the aroma is again lost. The temperature should be uniform and the beans should be stirred continually. It should also be remembered that not [Pg 206] all kinds or grades of coffee should be roasted alike. In order to develop the highest aroma, Mocha coffee should be roasted until it becomes a reddish yellow, and has lost 15 per cent of its weight. Martinique coffee should be roasted to a chestnut brown, with a loss of 20 percent in weight; Bourbon to a light bronze and a loss in weight of 18 percent.

The various coffee drinks prepared differ very widely in quality. This is dependent upon the varying methods employed in making them. The following method is highly recommended. It is advised to purchase a good quality of the unroasted beans and proceed as follows:

1. Sorting Berries.—Carefully remove bad berries, dirt, husks, stones, and other foreign matter usually present in larger or smaller quantities.

2. Roasting.—Roast as indicated above. Coat the hot beans with sugar to retain the aromatic principles; cool rapidly and keep in a dry place.

3. Grinding.—Grind fine just before the coffee is to be made.

4. Preparing the Coffee.—Coffee is usually made according to three methods; by infiltration, by infusion, and by boiling. Coffee by infiltration is made by allowing boiling water to percolate through the ground coffee. It is stated that much of the aroma is lost by this method. In the second process boiling water is poured upon the ground coffee and allowed to stand for some time. This gives a highly aromatic but comparatively weak coffee. In the third process the coffee is boiled for about five or ten minutes. This gives a strong coffee, but much of the aroma is lost. Since these methods do not give an ideal coffee an eminent authority recommends a fourth, as follows: For three small cups of coffee take one ounce of finely ground coffee. Place three-fourths of this in the pot of boiling water and boil for five or ten minutes; then throw in the remaining one-fourth and remove from the fire at once, stirring for one minute. The first portion of the coffee gives strength, the second the flavor. It is not advisable to filter the coffee as it is apt to modify the aroma. Allow it to stand until the grounds have settled.

Coffee is very frequently adulterated, especially ground coffee. It is stated that the beans have been adulterated with artificial beans made of starch or of clay. It is not uncommon to find pebbles which have been added to increase the weight. Most commonly the beans are not carefully hulled and sorted so that a considerable percentage of spoiled beans and hulls are present. The coffee plant seems to be quite susceptible to the attacks of various pests. The coffee blight is a microscopic fungus (Hemileia vastatrix) very common in Ceylon which has on several occasions almost entirely destroyed the coffee plantations. The coffee borer is the larva of a coleopter (Xylotrechus quadripes) which injures and destroys the trees by boring into the wood. The pest is most abundant in India, while another borer (Areocerus coffeæ) is common in South Africa. Another destructive pest is the so-called coffee bug (Lecanium coffeæ).

Ground coffee is adulterated with a great variety of substances. The roasted and ground roots of chicory (Cichorium intybus), carrot (Daucus carota), beet (Beta vulgaris), are very much used. The rush nut (Cyperus esculentus), and peanut are also used. A large number of seeds are used for adulterating purposes, as corn, barley, oats, wheat, rye, and other cereals; further, yellow flag, gray pea, milk vetch, astragalus, hibiscus, holly, Spanish broom, acorns, chestnuts, lupin, peas, haricots, horse bean, sun flower, seeds of gooseberry and grape. The seeds of Cassia occidentalis known as "wild coffee" are used as a substitute for coffee in Dominica and are said to have a flavor equal to that of true coffee. Sacca or Sultan coffee consists of the husks of the coffee berry, usually mixed with coffee and said to improve its flavor. In Sumatra an infusion is made of the coffee leaves or the young twigs and leaves. This is said to produce a refreshing drink having the taste and aroma of a mixture of coffee and tea. Efforts have been made, especially in England, to introduce leaf coffee with but little success.

|

||

| FROM KŒHLER'S MEDICINAL-PFLANZEN. 5-99 |

COFFEE. | |

DESCRIPTION OF PLATE.

A, twig with flowers and immature fruit, about natural size; 1, Corolla; 2, Stamens; 3, Style and stigma (pistil); 4, Ovary in longitudinal section; 5 and 6, Coffee bean in dorsal and ventral view; 7, Fruit in longitudinal section; 8, Bean in transverse section; 9, Bean sectioned to show caulicle; 10, Caulicle.

As already stated, most of the many varieties of coffee upon the market are obtained from one species, and are usually classified according to the countries from which they are shipped. The following are the most important varieties:

Coffee owes its stimulating properties to an alkaloid caffeine which occurs in the beans as well as in other parts of the plant. Caffeine also occurs in other plants; it is the active principle in Guarana and is perhaps identical with theine, the active principle of tea. It is generally believed that moderate coffee-drinking is beneficial rather than otherwise. It has ever been the favorite drink of those actively engaged in intellectual work. It has been tested and found satisfactory as a stimulant for soldiers on long or forced marches. Injurious effects are due to excessively strong coffee, or a long-continued use of coffee which has been standing for some time and which contains considerable tannin. Caffeine has been found very useful in hemicrania and various nervous affections. It has also been recommended in dropsy due to heart lesion. Strong, black coffee is very valuable in counteracting poisoning by opium and its derivatives. Coffee will also check vomiting. Strong coffee is apt to develop various nervous troubles, as palpitation of the heart, sleeplessness, indigestion, trembling. According to one authority, it is the aromatic principle of coffee which causes sleeplessness.

DR. CHARLES MACKAY.

ABBIE C. STRONG.

To the Editor of Birds and All Nature:

IN THE October number of Birds and All Nature was an article containing a list of the enemies of song birds and ordering their banishment, if one would enjoy the presence of the little songsters. Included in the list were the blue jays. There was also an article entitled, "A new Champion for the English Sparrow."

I always rejoice when someone comes forward in defense of the despised class, finding them not wholly faulty. The same hand created all, and surely each must be of some use. I feel like saying something in favor of the blue jay. I am sure that all will acknowledge that the jay has a handsome form and rare and beautiful plumage, which at least makes him "a thing of beauty;" he may not be "a joy forever," but surely a delight to the eye. Formerly my home was in northern Iowa, living many years in one place in a town of about 6,000 inhabitants. Our lawn was spacious for a town, filled with shrubbery and trees, both evergreen and deciduous. We did not encourage cats, usually keeping dishes of water here and there for the accommodation of the birds, and other attractions which they seemed to appreciate, as numerous migratory birds came each season, taking up their abode with us, to their evident enjoyment and giving us much pleasure. The jays were always with us, were petted and as they became friendly and tame, naturally we were much attached to them. The limb of a tree growing very close to a back veranda had been sawed off and a board nailed on the top forming a table, where we daily laid crumbs and a number of jays as regularly came after them. They were fond of meat and almost anything from the table. I found the jay to be a provident bird; after satisfying his appetite he safely buried the remainder of his food. I often noticed them concealing acorns and other nuts in hollow places in the trees, and noticed also that they were left till a stormy day which prevented them from finding food elsewhere as usual. I saw one bury a bit of meat under leaves near a dead flower twig; there came a rather deep fall of snow that night, but the bird managed to find it the next day with little difficulty and flew off with a cry of delight. The jay nested on the grounds, but that did not seem to prevent other birds from coming in great numbers and variety and making their little homes there also. I recall one year which was but a repetition of most of the years. The jays had a nest in a crab apple tree, a cat bird nested in a vine close to the house, a robin came familiarly to one of the veranda pillars in front of the house and built her solid nest of mud and grass. A brown thrush took a dense spruce for her nesting-place. A blackbird, to my surprise, built a nest in a fir tree. A grosbeak built a nest on a swaying branch of a willow at the back of the lot, and a bluebird occupied a little house we had put in a walnut tree for her convenience.

The orioles were always in evidence, usually making their appearance in early May when the fruit trees were in bloom; first seen busily looking the trees over for insects. Generally they selected an outreaching branch of a cottonwood tree, often near where they could be watched from a veranda, building their graceful nests and caring for their little ones. The chattering little wrens never questioned our friendliness, but always built loose little nests quite within our reach, either in a box we provided for them or over the door; at the same time others had their little homes in cozy places in the barn, or in the loose bark of an old tree. Each bird attended to its own affairs without perceptible molestation from others, as a rule. It was evident, however, that the jays were not tolerated in company with other birds to any great extent, and I fancy they had a rather bad reputation, for I noticed the birds took a defensive position often when a jay [Pg 212] made its appearance near their homes without any apparent evil intent, that I could discover. I would sometimes see as many as five varieties of birds after one jay; they were always victors, too. The robin, I always observed, could defend himself against a jay, never seemed afraid to do so, and indeed seemed to be the aggressor. The blue jay may be a sly bird, a "robber and a thief," though I never detected those traits to any especial extent; but he is handsome and brightens the winter landscape. To be sure, I found that he was fond of green peas and corn and did not hesitate in helping himself, also sampling the bright Duchess apples. The robin is equally fond of all small fruits, and greedy as well.

The bluebirds came regularly in the early spring for years, then ceased apparently when the sparrows made their appearance. The sparrows made many attempts to usurp the little house provided especially for the bluebird, but were not allowed to do so and never gained a footing on the premises; still the little spring harbinger ever after kept aloof from us. In the winter season the English sparrow came occasionally to share the bluejays' tidbits, but was promptly repulsed, although other birds came freely. The dainty little snowbird, several kinds of woodpeckers, now and then a chickadee, and some other winter birds came also. I had ways of enticing the birds to come near where I could watch their habits and peculiarities. All birds fear cats. There are cats and cats—some never molest birds or little chickens, but, as a rule, they seem to be their natural enemies. Little boys, I am sorry to say, cause great destruction of birds, often thoughtlessly, by trying their marksmanship. I would banish every "sling shot!" It is even worse than taking eggs, for they are generally replaced; but when the mother-bird is taken a little brood is left helpless to suffer and die. Thoughtful kindness towards little birds should be encouraged among children. I would have one day each year devoted to the subject in all public schools. It would bring birds under the observation of many who otherwise would pass them by unnoticed, and when one takes an interest in anything, be it flowers or birds, he or she is less likely to cause their destruction.

|

||

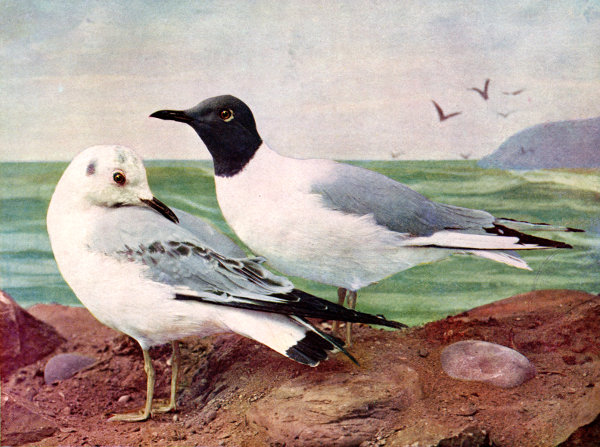

| FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES. 5-99 |

BONAPARTE'S GULL. 4/9 Life-size. |

COPYRIGHT 1899, NATURE STUDY PUB. CO., CHICAGO. |

LYNDS JONES.

THE whole of North America is the home of this pretty little gull—from the Bermudas to Labrador on the east, California to the Yukon on the west, and from the Gulf of Mexico at least to the Arctic circle. This species is often common near streams and other bodies of water large enough to furnish their food of fish. I have often seen flocks of twenty or more birds passing over central Iowa during the vernal migrations, sometimes even stooping to snatch some toothsome grub from the freshly turned furrow, but oftener sweeping past within easy range in that lithe, graceful flight so characteristic of this small gull. To the farm boy, shut in away from any body of water larger than an ice pond, where no ocean birds could ever be expected to wander, the appearance of this bird, bearing the wild freedom of the ocean in his every movement, is truly a revelation. It sends the blood coursing hotly through his veins until the impulse to get away into the broader activities of life cannot be put down. I know not why it is, but some birds, seen for the first time, seem to waft the perfume of an unknown country to us, well-nigh irresistibly calling us away upon a new field of exploration or endeavor.

The flight of Bonaparte's gull is worthy of careful study. In common with the other members of the group of gulls, he progresses easily by continuous leisurely wing beats, each stroke of the wings seeming to throw the light body slightly upward as though it were not more than a feather's weight. In the leisurely flight the watchful eye is turned hither and thither in quest of some food morsel, which may be some luckless fish venturing too near the surface of the water, or possibly floating refuse. The flight is sometimes so suddenly arrested that the body of the bird seems to be thrown backward before the plunge is made, thus giving the impression of a graceful litheness which is not seen in the larger birds of this group.

It is only in the breeding-plumage that this species wears the slaty plumbeous hood. In the winter the hood is wanting, though it may be suggested by a few dark spots, but there is a dusky spot over the ears always. It seems doubtful if the birds attain the dark hood until the second or third year, at which time they may be said to be fully adult.

It was formerly supposed that this gull nested entirely north of the United States, but later investigations have shown that it nests regularly in northern Minnesota and even as far south as the Saint Clair Flats near Detroit, Mich. It may then be said to nest from the northern United States northward to the limit of its range. It is rare along the Alaskan coast of Bering Sea, and there seems to be no record of it along the coast of the Arctic Ocean.

The nest is always placed in elevated situations, in bushes, trees, or on high stumps, and is composed of sticks, grasses, and lined with softer vegetable material. The eggs are three or four in number and have the grayish-brown to greenish-brown color, spotted and blotched with browns, which is characteristic of the gulls as a group.

While the gulls are fish-eaters and almost constantly hover above the fishers' nets, often catching over again the fish which the nets have trapped, we never hear of any warfare waged against them by the fishermen. On the contrary, the gulls are always on the most friendly terms with them, gladly accepting the fish found unworthy of the market. But let a bird of whatever kind visit the orchard or chicken-yard, for whatever purpose, and his life is not worth a moment's consideration. We need again to sit at the feet of fishermen as earnest inquirers.

FRED MAY,

School Taxidermist.

To the Editor of Birds and All Nature:

I AM glad the magazine of birds is furnishing its readers so many points about the good qualities of our birds. And as they are being protected more every year by the state laws and by the lovers of birds, I think they are sure to increase. I have often been asked about the decrease in bird life. The blame is generally put on the taxidermist, collector, sportsman, and schoolboy, which I claim is all wrong. The taxidermist collector of to-day is a lover of bird-life, and only hunts specimens to mount for a scientific purpose. This gives our school children a better chance to study them. The schoolboy and girl of to-day are doing great good in the protection of bird-life, and your book of birds has a warm friend among them. The true sportsman always lives up to the laws and takes a fair chance with dog and gun. The plume and bird collector will soon be a thing of the past, as hats trimmed with choice ribbons and jets are fast taking the place of those covered with feathers and birds. Now the persons who hide behind all these, and who destroy more bird-life in a single season than all the hunters and collectors of skins, are never brought to the eyes of the press. These are the people who have a fad for egg-collecting. They not only rob the nest of its one setting, but will take the eggs as long as the bird will continue to lay, and, not satisfied with that, will take the eggs from every bird as long as they can find them. They will even take the eggs after incubation has begun, and often-times, after a hard climb for the eggs, will destroy the nest. There are thousands upon thousands of settings of eggs of every kind taken every year by these fad egg collectors and you will see in some of our magazines on ornithology offers of from fifty to five hundred settings for sale. Now, what is an egg to this egg collector? Nothing. But to the lover of birds there is a great deal in that shell. There is a life; the song of the woods and of the home. In that shell is the true and faithful worker who has saved our farmers and our city homes and parks from the plagues of insects that would have destroyed crops and the beauty of our homes. Shall the law allow these nest-robbers to go on summer after summer taking hundreds of thousands of settings? If it shall I am afraid the increase in our bird-life will be slow. With the help of our game wardens and sporting-clubs a great deal of this could be stopped, and a great saving could be made in game birds' eggs. Our country school children can protect our song birds' nests by driving these collectors, with their climbing irons and collecting cans, from their farms in the breeding-season. Yes, it often looks sad to see a song bird drop at the report of the gun of the skin collector. But when we think of the bird-egg collector sneaking like a thief in the night up a tree or through a hedge, taking a setting of eggs on every side while the frightened mother sits high in the tree above, and then down and off in search of more, only to come back in a short time to take her eggs again—what is bird-life to him? What would he care to be sitting in the shade by the lake or stream listening to the song of the robin, or after a hard day's work in the hot summer, be seated on his porch to hear the evening song of the warbler and the distant call of the whippoorwill? Let the lovers of bird-life commence with the spring song, with the building of the nest, and save each little life they can from the egg collector. Will this man, if he may be called a man, look into his long drawers filled with eggs, and his extra settings for sale and trade? Let him think of the life he has taken, the homes he has made unhappy. I should think he would go like Macbeth from his sleep to wash the blood from his hands.

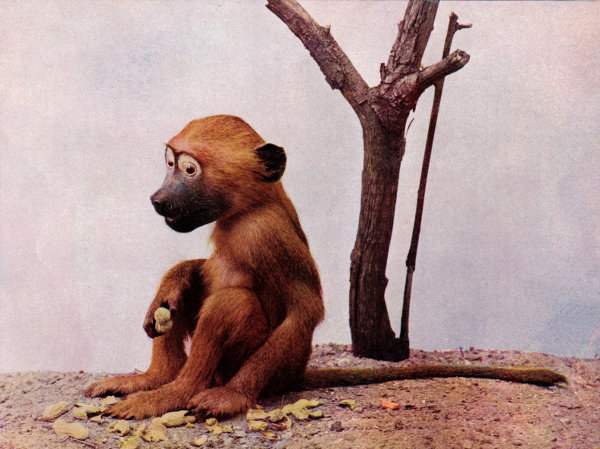

NATURALISTS seem to be agreed that the baboons (cynocephalus), while one of the most remarkable groups of the monkey family, are the ugliest, rudest, coarsest, and most repulsive representatives of it. The animal stands in the lowest degree of development of the monkey tribe, and possesses none of the nobler shapes and qualities of mind of other species. Aristotle called the baboons dog-headed monkeys, on account of the shape of their heads, which have a resemblance to that of a rude, fierce dog.

The baboons are found throughout Africa, Arabia, and India. In the main they are mountain monkeys, but also live in forests and are excellent tree-climbers. In the mountains they go as high as nine thousand to thirteen thousand feet above the sea-level, but give preference to countries having an elevation of three thousand or four thousand feet. Old travelers assert that mountainous regions are their true home.

The food of the baboons consists chiefly of onions, tubers, grass, fruit, eggs, and insects of all kinds, but, as they have also a greedy appetite for animal food, they steal chickens and kill small antelopes. In plantations, and especially vineyards, they cause the greatest damage, and are even said to make their raids in an orderly, deliberate, and nearly military manner.

Brehm, who observed them closely, says that they resemble awkward dogs in their gait, and even when they do stand erect they like to lean on one hand. When not hurried their walk is slow and lumbering; as soon as they are pursued, they fall into a singular sort of gallop, which includes the most peculiar movements of the body.

The moral traits of the baboons are quite in accord with their external appearance. Scheitlin describes them as all more or less bad fellows, "always savage, fierce, impudent, and malicious; the muzzle is a coarse imitation of a dog's, the face a distortion of a dog's face. The look is cunning, the mind wicked. They are more open to instruction than the smaller monkeys and have more common sense. Their imitative nature seems such that they barely escape being human. They easily perceive traps and dangers, and defend themselves with courage and bravery. As bad as they may be, they still are capable of being tamed in youth, but when they become old their gentle nature disappears, and they become disobedient; they grin, scratch, and bite. Education does not go deep enough with them. It is said that in the wild state they are more clever; while in captivity they are gentler. Their family name is 'dog-headed monkeys.' If they only had the dog's soul along with his head!" Another traveler says that they have a few excellent qualities; they are very fond of each other and their children; they also become attached to their keeper and make themselves useful to him. "But these good qualities are in no way sufficient to counterbalance their bad habits and passions. Cunning and malice are common traits of all baboons, and a blind rage is their chief characteristic. A single word, a mocking smile, even a cross look, will sometimes throw the baboon into a rage, in which he loses all self-control." Therefore the animal is always dangerous and never to be trifled with.

The baboons shun man. Their chief enemy is the leopard, though it oftener attacks the little ones, as the old fellows are formidable in self-defense. Scorpions they do not fear, as they break off their poisonous tails with great skill, and they are said to enjoy eating these animals as much as they do insects or spiders. They avoid poisonous snakes with great caution.

This animal is said to be remarkable for its ability in discovering water. In South Africa, when the water begins to run short, and the known fountains have failed, it is deprived of water for a whole day, until it is furious with thirst. A long rope is then tied to its collar, and it is suffered to run about where it chooses. First it runs forward a little, then stops, gets on its hind feet, [Pg 218] and sniffs the air, especially noting the wind and its direction. It will then, perhaps, change its course, and after running for some distance take another observation. Presently it will spy out a blade of grass, pluck it up, turn it on all sides, smell it, and then go forward again. Thus the animal proceeds until it leads the party to water. In this respect at least, baboons have their uses, and on occasions have been the benefactors of man.

The baboons have, in common with the natives, a great fondness for a kind of liquor manufactured from the grain of the durra or dohen. They often become intoxicated and thus become easy of capture. They have been known to drink wine, but could not be induced to taste whisky. When they become completely drunk they make the most fearful faces, are boisterous and brutal, and present altogether a degrading caricature of some men.

As illustrating the characteristics of fear and curiosity in the baboon, we will quote the following from the personal experience of Dr. Brehm, the celebrated traveler. He had a great many pets, among others a tame lioness, who made the guenons rather nervous, but did not strike terror to the hearts of the courageous baboons. They used to flee at her approach, but when she really seemed to be about to attack one of them, they stood their ground fairly well. He often observed them as they acted in this way. His baboons turned to flee before the dogs, which he would set upon them, but if a dog chanced to grab a baboon, the latter would turn round and courageously rout the former. The monkey would bite, scratch, and slap the dog's face so energetically that the whipped brute would take to his heels with a howl. More ludicrous still seemed the terror of the baboons of everything creeping, and of frogs. The sight of an innocent lizard or a harmless little frog would bring them to despair, and they would climb as high as their ropes would permit, clinging to walls and posts in a regular fit of fright. At the same time their curiosity was such that they had to take a closer look at the objects of their alarm. Several times he brought them poisonous snakes in tin boxes. They knew perfectly well how dangerous the inmates of these boxes were, but could not resist the temptation of opening them, and then seemed fairly to revel in their own trepidation.

|

||

| FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES. 5-99 |

COMMON BABOON. ⅓ Life-size. |

COPYRIGHT 1899, NATURE STUDY PUB. CO., CHICAGO. |

Buchanan.

E. K. M.

JUST as the Audubon societies and the appeals of humanitarians in general have had some effect in lessening the demand for the aigrette for millinery purposes, and their banishment, as officially announced, from the helmets of the British army, there springs up a new fashion which, if generally adopted, will prove very discouraging—especially to the birds.

"She made a decided sensation last evening at the opera," says Miss Vanity's fond mamma. "Those blackbirds with outspread wings at either side of her head were simply fetching. They drew every lorgnette and every eye in the house upon her. Not a woman of fashion, or otherwise, I venture to say, will appear at a public function here-after without a pair of stuffed birds in her hair."

A melancholy outlook truly, though as an onlooker expressed it, the effect of the spreading wings was vastly more grotesque than beautiful. The poor little blackbirds! Their destruction goes on without abatement.

"I like the hat," said a gentle-looking little lady in a fashionable millinery establishment the other day, "but," removing it from her head, "those blackbirds must be removed and flowers put in their place."

"A member of the Audubon Society, probably," queried the attendant, respectfully.

"No," was the answer, "but for years the birds have been welcome visitors at our country place, great flocks of blackbirds, especially, making their homes in our trees. This year, and indeed the last, but few appeared, and we have in consequence no love for the hunters and little respect for the women who, for vanity's sake, make their slaughter one of commercial necessity and greed."

'Tis said fashion is proof against the appeals of common sense or morality, and one must accept the statement as true when, in spite of all that has been said upon the subject, the Paris journals announce that "birds are to be worn more than ever and blouses made entirely of feathers are coming into fashion." The use of bird skins in Paris for one week represent the destruction of one million three hundred thousand birds; in London the daily importation ranges from three hundred to four hundred thousand. It is honestly asserted that, in the height of the season, fifty thousand bird skins are received in New York City daily.

At the annual meeting of the Audubon Society of New York state a letter was read from Governor Roosevelt in which he said that he fully sympathized with the purpose of the society and that he could not understand how any man or woman could fail to exert all influence in support of its object.

"When I hear of the destruction of a species," he added, "I feel just as if all the works of some great writer had perished; as if one had lost all instead of only a part of Polybius or Livy."

Rev. Dr. Henry Van Dyke sent a letter in which he said the sight of an aigrette filled him with a feeling of indignation, and that the skin of a dead songbird stuck on the head of a tuneless woman made him hate the barbarism which lingers in our so-called civilization. Mr. Frank M. Chapman, at the same meeting, stated that the wide-spread use of the quills of the brown pelican for hat trimming was fast bringing about the extinction of that species.

DR. N. D. HILLIS.

NATURE loves silence and mystery. Reticent, she keeps her own counsel. Unlike man, she never wears her heart upon her sleeve. The clouds that wrap the mountain about with mystery interpret nature's tendency to veil her face and hold off all intruders. By force and ingenuity alone does man part the veil or pull back the heavy curtains. The weight of honors heaped upon him who deciphers her secret writings on the rock or turns some poison into balm and medicine, or makes a copper thread to be a bridge for speech, proclaims how difficult it is to solve one of nature's simplest secrets. For ages man shivered with cold, but nature concealed the anthracite under thick layers of soil. For ages man burned with fever, but nature secreted the balm under the bark of the tree. For ages, unaided, man bore his heavy burdens, yet nature veiled the force of steam and concealed the fact that both wind and river were going man's way and might bear his burdens.

Though centuries have passed, nature is so reticent that man is still uncertain whether a diet of grain or a diet of flesh makes the ruddier countenance. Also it is a matter of doubt whether some young Lincoln can best be educated in the university of rail-splitting or in a modern college and library; whether poverty or wealth does the more to foster the poetic spirit of Burns or the philosophic temper of Bach. In the beautiful temple of Jerusalem there was an outer wall, an inner court, "a holy place," and afar-hidden within, "a place most holy." Thus nature conceals her secrets behind high walls and doors, and God also hath made thick the clouds that surround the divine throne.

CONCEALMENTS OF NATURE.

Marvelous, indeed, the skill with which nature conceals secrets numberless and great in caskets small and mean. She hides a habitable world in a swirling fire-mist. A magician, she hides a charter oak and acre-covering boughs within an acorn's shell. She takes a lump of mud to hold the outlines of a beauteous vase. Beneath the flesh-bands of a little babe she secretes the strength of a giant, the wisdom of a sage and seer. A glorious statue slumbers in every block of marble; divine eloquence sleeps in every pair of human lips; lustrous beauty is for every brush and canvas; unseen tools and forces are all about inventors, but they who wrest these secrets from nature must "work like slaves, fight like gladiators, die like martyrs."

For nature dwells behind adamantine walls, and the inventor must capture the fortress with naked fists. In the physical realm burglars laugh at bolts and bars behind which merchants hide their gold and gems. Yet it took Ptolemy and Newton 2,000 years to pick the lock of the casket in which was hidden the secret of the law of gravity. Four centuries ago, skirting the edge of this new continent, neither Columbus nor Cabot knew what vast stretches of valley, plain, and mountain lay beyond the horizon.

If once a continent was the terra incognita, now, under the microscope, a drop of water takes on the dimensions of a world, with horizons beyond which man's intellect may not pass. Exploring the raindrop with his magnifying-glass, the scientist marvels at the myriad beings moving through the watery world. For the teardrop on the cheek of the child, not less than the star riding through God's sky, is surrounded with mystery, and has its unexplored remainder. Expecting openness from nature, man finds clouds and concealment. He hears a whisper where he listens for the full thunder of God's voice to roll along the horizon of time.

PROF. HENRY C. MERCER.

SEVEN bluish-white, almost spherical eggs, resting on the plaster floor of the court-house garret, at Doylestown, Pennsylvania, caught the eye of the janitor, Mr. Bigell, as one day last August he had entered the dark region by way of a wooden wicket from the tower. Because the court-house pigeons, whose nestlings he then hunted, had made the garret a breeding-place for years, he fancied he had found another nest of his domestic birds. But the eggs were too large, and their excessive number puzzled him, until some weeks later, visiting the place again (probably on the morning of September 20), he found that all the eggs save one had hatched into owlets, not pigeons.

The curious hissing creatures, two of which seemed to have had a week's start in growth, while one almost feather-less appeared freshly hatched, sat huddled together where the eggs had lain, close against the north wall and by the side of one of the cornice loop-holes left by the architect for ventilating the garret. Round about the young birds were scattered a dozen or more carcasses of mice (possibly a mole or two), some of them freshly killed, and it was this fact that first suggested to Mr. Bigell the thought of the destruction of his pigeons by the parent owls, who had thus established themselves in the midst of the latter's colony. But no squab was ever missed from the neighboring nests, and no sign of the death of any of the other feathered tenants of the garret at any time rewarded a search.

As the janitor stood looking at the nestlings for the first time, a very large parent bird came in the loop-hole, fluttered near him and went out, to return and again fly away, leaving him to wonder at the staring, brown-eyed, monkey-faced creatures before him. Mr. Bigell had thus found the rare nest of the barn owl, Strix pratincola, a habitation which Alexander Wilson, the celebrated ornithologist, had never discovered, and which had eluded the search of the author of "Birds of Pennsylvania." One of the most interesting of American owls, and of all, perhaps, the farmer's best friend, had established its home and ventured to rear its young, this time not in some deserted barn of Nockamixon swamp, or ancient hollow tree of Haycock mountain, but in the garret of the most public building of Doylestown, in the midst of the county's capital itself. When the janitor had left the place and told the news to his friends, the dark garret soon became a resort for the curious, and two interesting facts in connection with the coming of the barn owls were manifest; first, that the birds, which by nature nest in March, were here nesting entirely out of season—strange to say, about five months behind time; from which it might be inferred that the owls' previous nests of the year had been destroyed, and their love-making broken up in the usual way; the way, for instance, illustrated by the act of any one of a dozen well remembered boys who, like the writer, had "collected eggs;" by the habitude of any one of a list of present friends whose interest in animals has not gone beyond the desire to possess them in perpetual captivity and watch their sad existence through the bars of a cage; or by the "science" of any one of several scientific colleagues who, hunting specimens for the sake of a show-case, "take" the female to investigate its stomach.

Beyond the extraordinary nesting date, it had been originally noticed that the mother of the owlets was not alone, four or five other barn owls having first come to the court-house with her. Driven by no one knew what fate, the strange band had appeared to appeal, as if in a body, to the protection of man. They had placed themselves at his mercy as a bobolink when storm driven far from shore lights upon a ship's mast.

But it seemed, in the case of the owls, [Pg 224] no heart was touched. The human reception was that which I have known the snowy heron to receive, when, wandering from its southern home, it alights for awhile to cast its fair shadow upon the mirror of the Neshaminy, or such as that which, not many years ago, met the unfortunate deer which had escaped from a northern park to seek refuge in Bucks County woods. At first it trusted humanity; at last it fled in terror from the hue and cry of men in buggies and on horseback, of enemies with dogs and guns, who pursued it till strength failed and its blood dyed the grass.

So the guns of humanity were loaded for the owls. The birds were too strange, too interesting, too wonderful to live. The court house was no sanctuary. Late one August night one fell at a gun shot on the grass at the poplar trees. Then another on the pavement by the fountain. Another, driven from its fellows, pursued in mid air by two crows, perished of a shot wound by the steps of a farm-house, whose acres it could have rid of field mice.

The word went out in Doylestown that the owls were a nuisance. But we visited them and studied their ways, cries, and food, to find that they were not a nuisance in their town sanctuary.

In twenty of the undigested pellets, characteristic of owls, left by them around the young birds, we found only the remains, as identified by Mr. S. N. Rhoads of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, of the bones, skulls, and hair of the field mouse (Microtus pennsylvanicus) and star nose mole (Condylura cristata). "They killed the pigeons," said someone, speaking without authority, after the manner of a gossip who takes away the character of a neighbor without proof. But they had not killed the pigeons. About twelve pairs of the latter, dwelling continually with their squabs in the garret, though they had not moved out of the particular alcove appropriated by the owls, had not been disturbed. What better proof could be asked that THE BARN OWL IS NOT A POULTRY DESTROYER?

It was objected that the owls' cries kept citizens awake at night. But when, one night last week, we heard one of their low, rattling cries, scarcely louder than the note of a katydid, and learned that the janitor had never heard the birds hoot, and that the purring and hissing of the feeding birds in the garret begins about sundown and ceases in the course of an hour, we could not believe that the sleep of any citizen ever is or has been so disturbed.

When I saw the three little white creatures yesterday in the court-house garret, making their strange bows as the candle light dazzled them, hissing with a noise as of escaping steam, as their brown eyes glowed, seemingly through dark-rimmed, heart-shaped masks, and as they bravely darted towards me when I came too near, I learned that one of the young had disappeared and that but one of the parent birds is left, the mother, who will not desert her offspring.

On October 28 two young birds were taken from their relatives to live henceforth in captivity, and it may be that two members of the same persecuted band turned from the town and flew away to build the much-talked-of nest in a hollow apple tree at Mechanics' Valley. If so, there again the untaught boy, agent of the mother that never thought, the Sunday school that never taught, and the minister of the Gospel that never spoke, was the relentless enemy of the rare, beautiful, and harmless birds. If he failed to shoot the parents, he climbed the tree and caught the young.

If the hostility to the owls of the court house were to stop, if the caged birds were to be put back with their relatives, if the nocturnal gunners were to relent, would the remaining birds continue to add an interest to the public buildings by remaining there for the future as the guests of the town? Would the citizens of Doylestown, by degrees, become interested in the pathetic fact of the birds' presence, and grow proud of their remarkable choice of sanctuary, as Dutch towns are proud of their storks? To us, the answer to these questions, with its hope of enlightenment, seems to lie in the hands of the mothers, of the teachers of Sunday schools, and of the ministers.

|

||

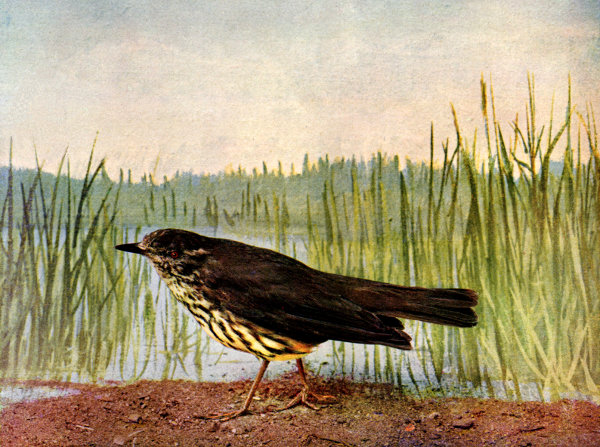

| FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES. 5-99 |

GRINNELL'S WATER THRUSH. Life-size. |

COPYRIGHT 1899, NATURE STUDY PUB. CO., CHICAGO. |

C. C. MARBLE.

THE water thrush (Seiurus noveboracensis) has so many popular names that it will be recognized by most observers by one or more of them. It is called small-billed water-thrush, water wagtail, water kick-up, Besoy kick-up, and river pink (Jamaica), aquatic accentor, and New York aquatic thrush. It is found chiefly east of the Mississippi River, north to the Arctic coast, breeding from the north border of the United States northward. It winters in more southern United States, all of middle America, northern South America, and all of West Indies. It is accidental in Greenland. In Illinois this species is known as a migrant, passing slowly through in spring and fall, though in the extreme southern portion a few pass the winter, especially if the season be mild. It frequents swampy woods and open, wet places, nesting on the ground or in the roots of overturned trees at the borders of swamps. Mr. M. K. Barnum of Syracuse, New York, found a nest of this species in the roots of a tree at the edge of a swamp on the 30th of May. It was well concealed by the overhanging roots, and the cavity was nearly filled with moss, leaves, and fine rootlets. The nest at this date contained three young and one egg. Two sets were taken, one near Listowel, Ontario, from a nest under a stump in a swamp, on June 7, 1888; the other from New Canada, Nova Scotia, July 30, 1886. The nest was built in moss on the side of a fallen tree. The eggs are creamy-white, speckled and spotted, most heavily at the larger ends, with hazel and lilac and cinnamon-rufous.

As a singer this little wagtail is not easily matched, though as it is shy and careful to keep as far from danger as possible, the opportunity to hear it sing is not often afforded one. Though it makes its home near the water, it is sometimes seen at a considerable distance from it among the evergreen trees.

ALONG with Tagals, Ygorottes, and other queer human beings Uncle Sam has annexed in the Philippine islands, says the Chronicle, is the tarsier, an animal which is now declared to be the grandfather of man.

They say the tarsier is the ancestor of the common monkey, which is the ancestor of the anthropoid ape, which some claim as the ancestor of man.

A real tarsier will soon make his appearance at the national zoological park. His arrival is awaited with intense interest.

Monsieur Tarsier is a very gifted animal. He derives his name from the enormous development of the tarsus, or ankle bones of his legs. His eyes are enormous, so that he can see in the dark. They even cause him to be called a ghost. His fingers and toes are provided with large pads, which enable him to hold on to almost anything.

Professor Hubrecht of the University of Utrecht has lately announced that Monsieur Tarsier is no less a personage than a "link" connecting Grandfather Monkey with his ancestors. Thus the scale of the evolution theorists would be changed by Professor Hubrecht to run: Man, ape, monkey, tarsier, and so on, tarsier appearing as the great-grandfather of mankind.

Tarsier may best be described as having a face like an owl and a body, limbs, and tail like those of a monkey. His sitting height is about that of a squirrel. As his enormous optics would lead one to suppose, he cuts capers in the night and sleeps in the daytime, concealed usually in abandoned clearings, where new growth has sprung up to a height of twenty feet or more. Very often he sleeps in a standing posture, grasping the lower stem of a small tree with his long and slender fingers and toes. During his nightly wanderings he utters a squeak like that of a monkey. During the day the pupils of his eyes contract to fine lines, but after dark expand until they fill most of the irises. From his habit of feeding only upon insects he has a strong, bat-like odor.

John Whitehead, who has spent the last three years studying the animals of the Philippines, foreshadows the probable behavior of the tarsier when he arrives at the national "zoo." The Philippine natives call the little creature "magou."