EXPORTS OF DOMESTIC WHEAT AND FLOUR

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

RAILROADS

RATES AND REGULATION

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

RAILROADS

FINANCE AND ORGANIZATION

8vo. Pages xx + 638, with Index. $3.00 Net

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | |

|---|---|

| I | Railroad Construction Finance. |

| II | Capital and Capitalization. |

| III | Railroad Securities: Capital Stock, etc. |

| IV | Railroad Securities: Mortgage Indebtedness, etc. |

| V | The Course of Market Prices. |

| VI | Speculation. |

| VII | Stock-Watering. |

| VIII | Stock-Watering (continued). |

| IX | State Regulation of Security Issues. |

| X | The Determination of Reasonable Rates. |

| XI | Physical Valuation: Reasonable Rates. |

| XII | Receivership and Reorganization. |

| XIII | Intercorporate Relations. |

| XIV | Combination: Eastern and Southern Systems. |

| XV | Railroad Combination in the West. |

| XVI | The Anthracite Coal Arrangement. |

| XVII | Dissolution under the Anti-Trust Law. |

| XVIII | Pooling and Inter-Railway Agreements. |

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

BY

WILLIAM Z. RIPLEY, PH.D.

Nathaniel Ropes Professor of Economics In Harvard University

WITH 41 MAPS AND DIAGRAMS

New Impression

LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO.

FOURTH AVENUE & 30TH STREET, NEW YORK

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, AND MADRAS

1916

COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

Published, November, 1912

Reprinted, November, 1913

September, 1916

THE·PLIMPTON·PRESS

[W·D·O]

NORWOOD·MASS·U·S·A

This treatise is the outcome of a continuous personal interest in railroads, practically coincident in point of time with the period of active participation of the Federal government in their affairs. During these years, since 1887 when the Act to Regulate Commerce was passed, as the problem of public regulation has gradually unfolded, opportunity has offered itself to me to view the subject from different angles. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as instructor of embryo engineers in the economic aspects of their callings; in service for the United States Industrial Commission in 1900-01, in touch alike with government officials and, travelling all about the country, with shippers and commercial bodies during a period of acute unrest; and finally ripening the practical experience, thus gained, in the favoring atmosphere of Harvard University, seeking to imbue future citizens with a sense of their civic responsibilities; through all these years, the conviction has steadily grown that, as one of the most fundamental agents in our American economic affairs, the subjection of transportation to public control was a primary need of the time. An earnest effort has been made to set down the facts concerning this highly controversial subject with scientific rigor and with fairness to all three of the great parties concerned, the owners, the shippers and the people. If bias there be, it will in all likelihood be found to favor the welfare of the "dim inarticulate multitude,"—that so inert mass of interests and aspirations, too indefinitely informed as to details and too much occupied in earning its daily bread, to be able to analyze its own vital concerns, to give expression to its will, and even sometimes, as it seems, wisely to choose its spokesmen and representatives.[Pg vi] It is this helpless and unorganized general public, always in need of an advocate, which, perhaps, most strongly appeals to the academic mind. If there be lack of judicial poise in this regard, it is, at all events, palliated by free confession in advance.

Nor is the history of the assumption by public authority of its inherent right to control railroads, as narrow an interest as it at first appears. Transportation, as a service, is the commodity produced by common carriers. The manner in which the price of this commodity has been brought under governmental regulation has a direct bearing upon another problem just beginning to open up; namely that of the control by the state of the prices of other things. It is not unlikely, in my judgment, that the final solution of the so-called Trust Problem in the United States, whether for good or ill, may ultimately contain as one important feature, the determination by governmental authority of reasonable prices for such prime necessities of life as milk, ice, coal, sugar and oil, when produced under monopolistic conditions. This view is shared by my colleague Professor Taussig in his "Principles of Economics." It is also distinctly set forth by President Van Hise of the University of Wisconsin, in his recent "Concentration and Control." When the seed of such an industrial policy is planted, as I believe it possible in time, the soil will have been richly prepared for its reception by our experience in the determination of reasonable charges for the services of railroads and other public utilities.

A word of explanation may also be offered to the reader who finds in these pages an almost exuberant mass of illustrative material. Possibly, even, it may be alleged that in places so thick are the circumstantial trees of evidence that one can scarcely perceive the wood of principle. But, under the circumstances, it is almost inevitable that this should be so. The method of inquiry adopted has been mainly inductive. Text books and theoretical treatises have been used only by the way. I hold them to be merely of secondary importance. The principal reliance has been upon concrete data, painstakingly[Pg vii] gathered through many years from original sources. In this present excursion in the far more complex domain of the social sciences, an endeavor has been made to adhere strictly to the same scientific method pursued in the field of natural science in writing "The Races of Europe." A search far and wide for every possible bit of raw material had to be made at the outset. To this succeeded the classification and realignment of the concrete data thus obtained. The last step of all, was the formulation of the governing economic principles. But an almost indispensable result of this mode of work is a plenitude of reference and example. One might almost say that under such circumstances it becomes second nature to demand concrete illustration for every economic theory or principle laid down. Such a statement, however, would be fallacious. It would misrepresent the true sequence of events as above outlined. Rather should it be affirmed, that, inasmuch as the concrete examples are the sources of the reasoning, no theory can be held valid for which somewhere or somehow, positive illustration drawn from practice cannot be found. Such an ideal is, indeed, difficult to attain; but it may be stated as a cardinal principle to be always kept in mind. And it ought to excuse an author from the charge of over-elaboration of detail in illustration. The only crimes for which no verbal atonement will suffice are that the chosen illustration does not fit the principle, or else that the facts have been distorted to serve a preconceived idea.

References throughout this work to a second volume will be noted. This will deal primarily with matters of finance and corporate relations. The general subject of railroad combination was necessarily relegated to another set of covers. This, however, is quite fitting, inasmuch as the connection between matters of finance and organization is at all times so intimate and necessary. The development of inter-railway relationships has been, perhaps, next to the establishment of government regulation, the most striking phenomenon of the last decade. It is absolutely essential to a comprehension of present day financial problems, to understand the nature and extent of the[Pg viii] consolidation of interests which obtains. This second volume, now nearly completed, will, it is hoped, appear early in 1913.

This volume is also frequently linked by means of cross references to a set of reprints of notable interstate commerce cases or special articles which was published some years ago as "Railway Problems." (Ginn & Co.) Much new material having accumulated since its original appearance in 1907, it is the intention to prepare a new and revised edition, particularly designed as an accompaniment to this treatise. But the same chapter numbers will be preserved for all material taken over from the first edition.

Many friends and specialists, who shall be unnamed, have been of assistance in various ways for which I am duly grateful. But a few have been so peculiarly helpful that it is fitting to make more particular mention of my personal obligation. Especially is this true of Hon. Balthasar H. Meyer of the Interstate Commerce Commission, from whom through many years of friendship and common interest in the subject, have come all sorts of aid and suggestion. Prof. F. H. Dixon of Dartmouth College, Statistician of the Bureau of Railway Economics at Washington, also a co-worker in the same field, has always without reserve freely shared the best he had to give. I have drawn liberally from his special contributions on transportation, particularly in the history of recent Federal legislation. Despite the difference in our point of view, the always friendly criticism of Frederic A. Delano, President of the Wabash Railroad, has been most welcome and serviceable. In matters of classification, Mr. D. O. Ives, Traffic Expert of the Boston Chamber of Commerce, has extended a helping hand. And I have profited greatly from the published work of Mr. Samuel O. Dunn, now Editor of the Railway Age Gazette. In this connection, acknowledgment should be made of my deep obligation to the other editors of that admirable technical journal, who have in series during a number of years afforded me an opportunity of reaching a class of readers and, it should be added, not infrequently of unsparing critics, whose intelligence and technical knowledge have held me to a strict accounting[Pg ix] in all matters of fact or principle. Without this critical oversight, many statements, happily now tested, would have held less secure place. Then again, there is the entire staff of the Interstate Commerce Commission to whom I have been a care and trouble for so many years. Ungrudgingly have its members always given response to all sorts of requests, whether for documents, statistics or opinions. Without the official stores of information at Washington, this present volume would have been woefully incomplete.

CHAPTER I

THE HISTORY OF TRANSPORTATION IN THE UNITED STATES

Significance of geographical factors, 1.—Toll roads before 1820, 2.—The "National pike," 3.—Canals and internal waterways before 1830, 4.—The Erie Canal, 4.—Canals in the West, 6.—First railroad construction after 1830, 7.—Early development in the South, 9.—Importance of small rivers, 10.

The decade 1840-1860, 11.—Slow railway growth, mainly in the East, 12.—Rapid expansion 1848-1857; western river traffic, 13.—Need of north and south railways, 14.—Traffic still mainly local, 15.—Effect of the Civil War, 16.—Rise of New York, 17.—Primitive methods, 17.

The decade 1870-1880, 18.—Trans-Mississippi development, 18.—Pacific Coast routes opened, 19.—Development of export trade in grain and beef, 20.—Trunk line rate wars, 21.—Improvements in operation, 23.—End of canal and river traffic, 24.

The decade 1880-1890, 27.—Phenomenal railway expansion, 28.—Transcontinental trade, 28.—Speculation rampant, 29.—Growth of western manufactures, 30.—Rise of the Gulf ports, 31.—Canadian competition, 33.—General résumé and forecast, 34.

Public land grants, 35.—Direct financial assistance, 37.—History of state aid, 39.—Federal experience with transcontinental roads, 40.

CHAPTER II THE THEORY OF RAILROAD RATES

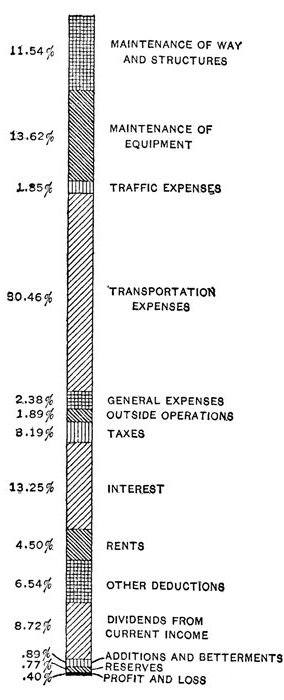

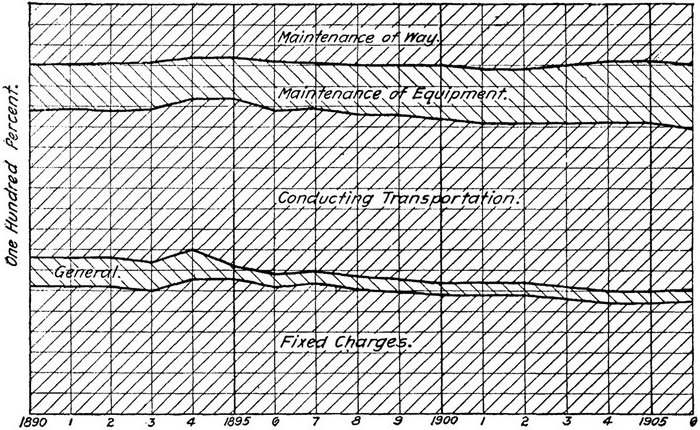

Analysis of railroad expenditures, 44.—Constant v. variable outlays, 45.—Fixed charges, 46.—Official grouping of expenses, 46.—Variable expenses in each group, 51.—Peculiarities of different roads and circumstances, 56.—Periodicity of expenditures, 61.—Joint cost, 67.—Separation of passenger and freight business, 68.

CHAPTER III THE THEORY OF RAILROAD RATES (Continued)

The law of increasing returns, 71.—Applied to declining traffic, 73.—Illustrated by the panic of 1907, 75.—Peculiarly intensified on railroads, 76.

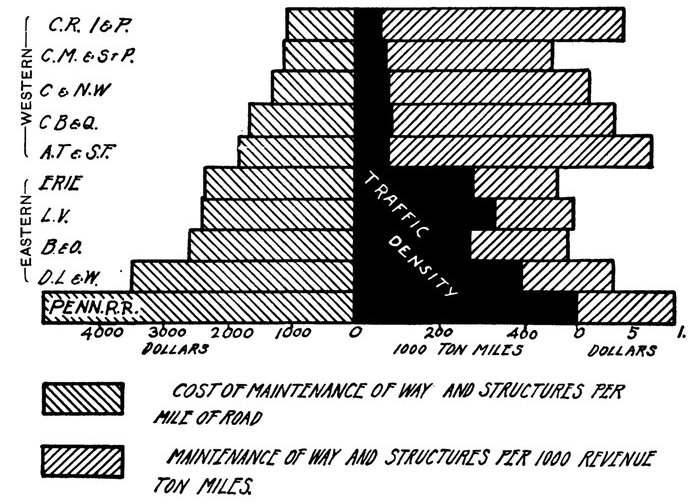

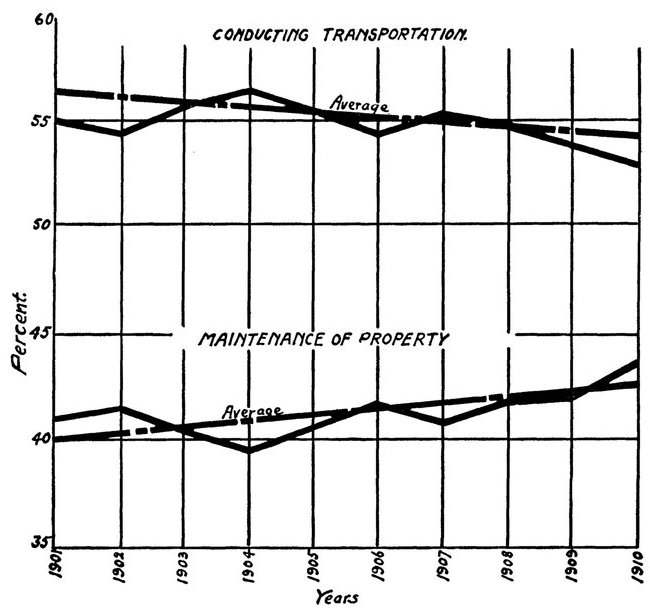

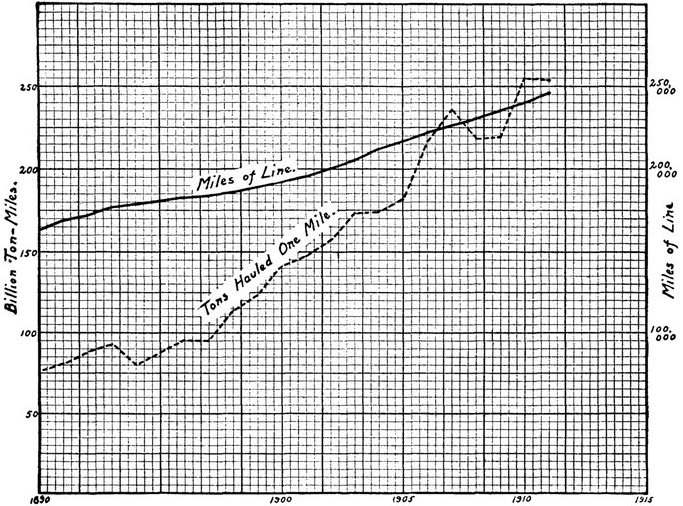

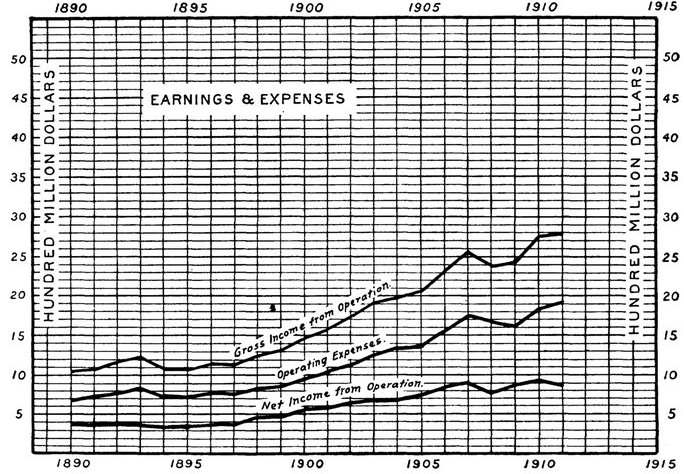

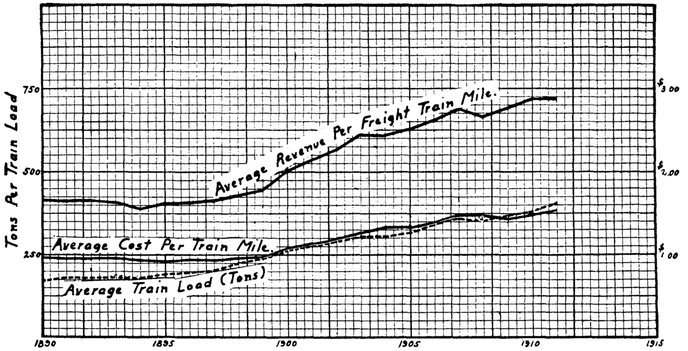

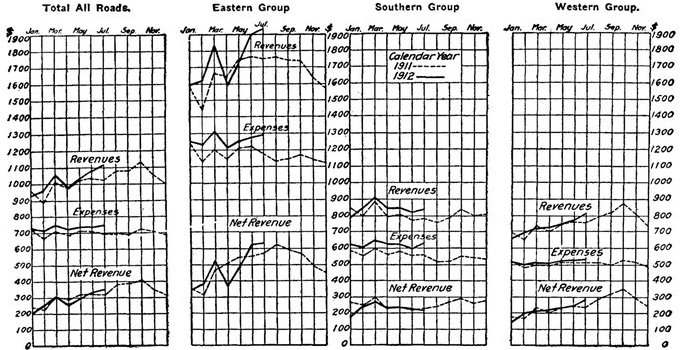

Growth of mileage and traffic in the United States since 1889, 77.—Increase of earnings, 79.—Operating expenses, gross and net income, 80.—Comparison with earlier decades, 85.—Density of traffic, 86.—Increase of train loads, 88.—Limitations upon their economy, 92.—Heavier rails, 93.—Larger locomotives, 94.—Bigger cars, 95.—Net result of improvements upon efficiency and earning power, 97.

The law of increasing returns due to financial rather than operating factors, 99.

CHAPTER IV

RATE MAKING IN PRACTICE

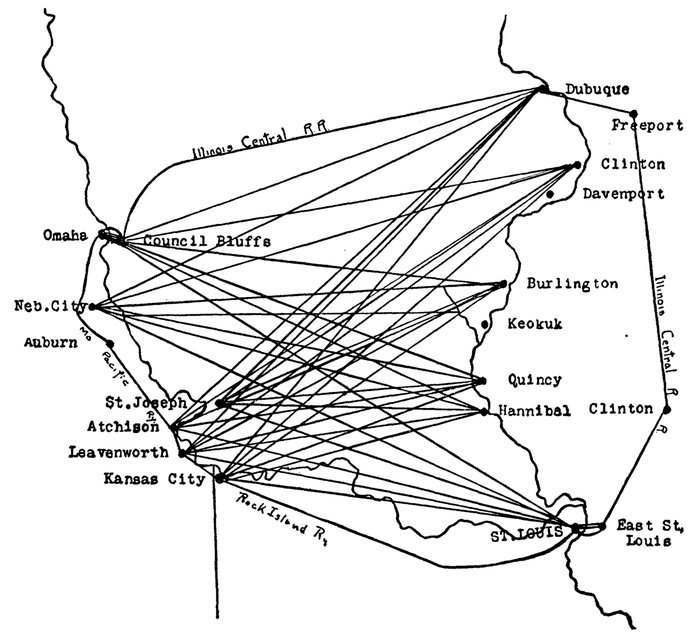

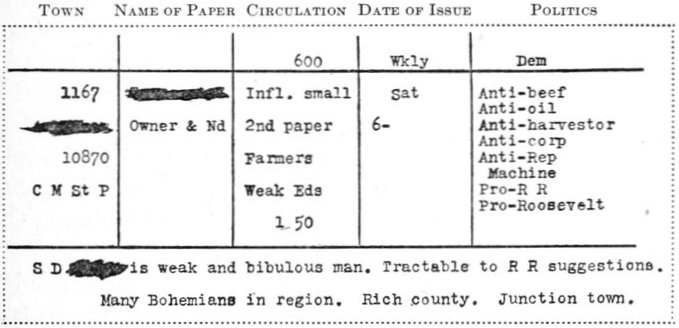

Evolution of rate sheets, 101.—Terminal v. haulage costs, 102.—Local competition, 104.—What the traffic will bear, 107.—Trunk line rate system, 111.—Complexity of rate structure, 113.—Competition of routes, 114.—Competition of facilities, 116.—Competition of markets, 118.—Ever-widening markets, 119.—Primary and secondary market competition, 121.—Jobbing or distributive business, 124.—Flat rates, 127.—Mississippi-Missouri rate scheme, 128.—Relation between raw materials and finished products, 134.—Export rates on wheat and flour, 135.—Cattle and packing-house products, 139.—Refrigerator cars, 140.—By-products and substitution, 142.—Kansas corn and Minnesota flour, 143.—Ex-Lake grain rates, 145.

CHAPTER V

RATE MAKING IN PRACTICE (Continued)

Effect of changing conditions, 147.—Lumber and paper rates, 148.—Equalizing industrial conditions, 148.—Protecting shippers, 149.—Pacific Coast lumber rates, 150.—Elasticity and quick adaptation, 152.—Rigidity and delicacy of adjustment, 153.—Transcontinental rate system, 154.—Excessive elasticity of rates, 155.—More stability desirable, 159.—Natural v. artificial territory and rates, 159.—Economic waste, 159.—Inelastic conditions, 161.—Effect upon concentration of population, 162.—Competition in transportation and trade contrasted, 163.—No abandonment of field, 165.

Cost v. value of service, 166.—Relative merits of each, 167.—Charging what the traffic will bear, 169.—Unduly high and low rates,[Pg xiii] 171.—Dynamic force in value of service, 177.—Cost of service in classification, 179.—Wisconsin paper case, 181.—Cost and value, of service equally important, checking one another, 184.

CHAPTER VI

PERSONAL DISCRIMINATION

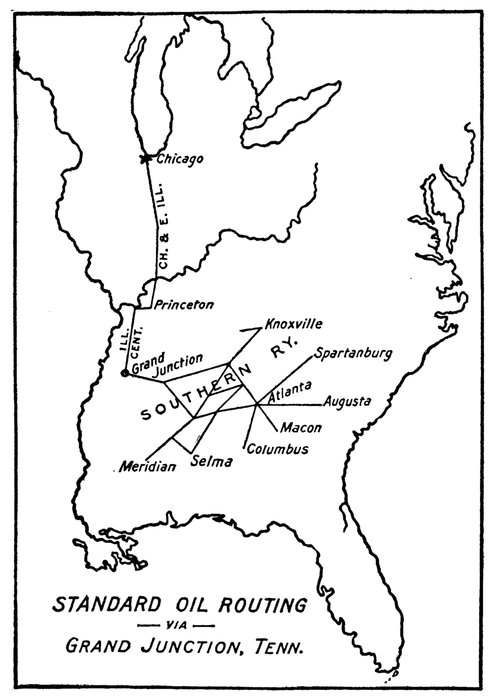

Rebates and monopoly, with attendant danger to carriers, 185.—Personal discrimination defined, 188.—Distinction between rebating and general rate cutting, 188.—Early forms of rebates, 189.—Underbilling, underclassification, etc., 190.—Private car lines, 192.—More recent forms of rebating described, 195.—Terminal and tap-lines, 196.—Midnight tariffs, 197.—Outside transactions, special credit, etc., 198.—Distribution of coal cars, 199.—Standard Oil Company practices, 200.—Discriminatory open adjustments from competing centres, 202.—Frequency of rebating since 1900, 204-6.—The Elkins Law of 1903, 205.—Discrimination since 1906, 207.—The grain elevation cases, 211.—Industrial railroads once more, 212.

CHAPTER VII

LOCAL DISCRIMINATION

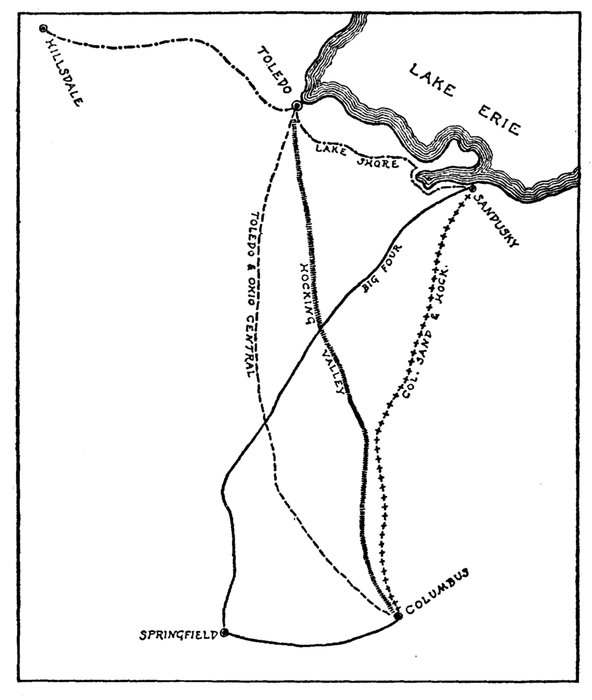

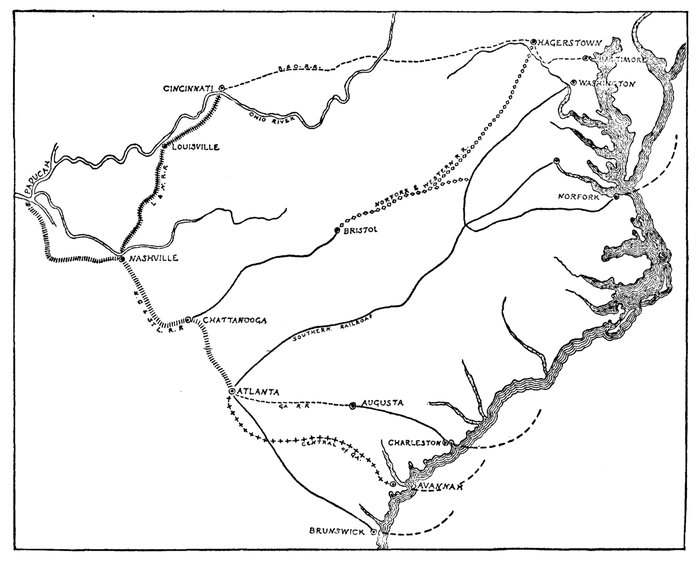

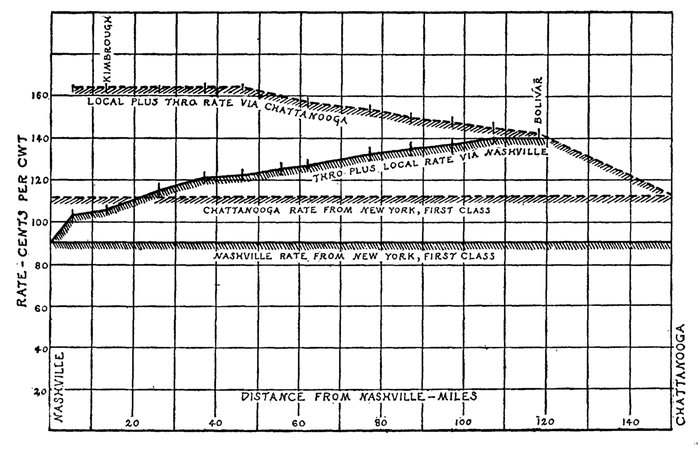

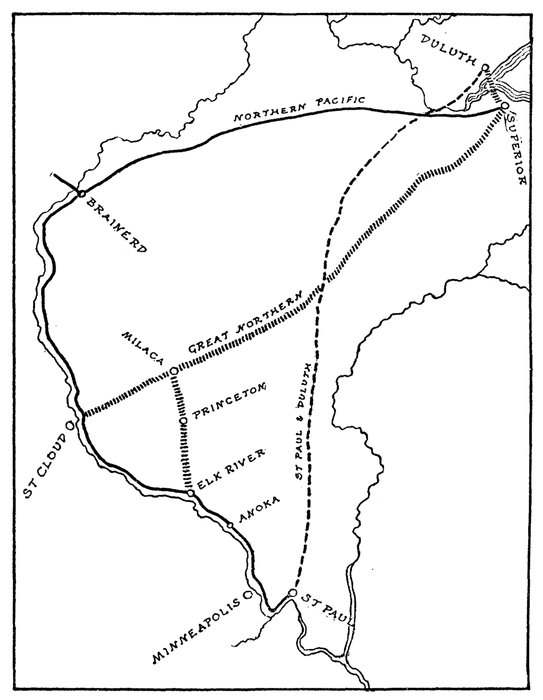

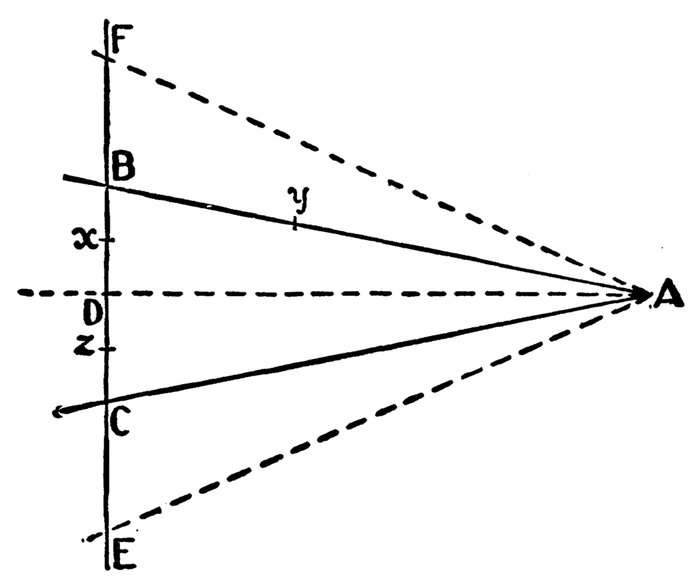

Concrete instances, 215.—Hadley's oyster case not conclusive, 217.—Two variants: lower long-haul rates by the roundabout route, as in the Hillsdale, Youngstown, and some Southern cases, 221; or by the direct route, as in the Nashville-Chattanooga and other southern cases, 225.—Complicating influence of water transportation, 232.—Market competition from various regions, a different case, 234.—The basing point (southern) and basing line (Missouri river) systems, 238.—Their inevitable instability and probable ultimate abandonment, 242.—Postage-stamp rates, illustrated by transcontinental tariffs, 245.—Which line makes the rate? 255.—Cost not distance, determines, 256.—Fixed charges v. operating expenses, 257.—Proportion of local business, 259.—Volume and stability of traffic important, 261.—Generally the short line rules, but many exceptions occur, 263.

CHAPTER VIII

PROBLEMS OF ROUTING

Neglect of distance, an American peculiarity, 264.—Derived from joint cost, 265.—Exceptional cases, 265.—Economic waste in American practice, 268.—Circuitous rail carriage, 269.—Water and rail-and-water shipments, 273.—Carriage over undue distance, 277.—An outcome of commercial competition, 278.—Six causes of economic waste, illustrated, 280.—Pro-rating and rebates, 281.—Five effects of dis[Pg xiv]regard of distance, 288.—Dilution of revenue per ton mile, 289.—Possible remedies for economic waste, 292.—Pooling and rate agreements, 293.—The long and short haul remedy, 295.

CHAPTER IX

FREIGHT CLASSIFICATION

Importance and nature of classification described, 300.—Classifications and tariffs distinguished, as a means of changing rates, 301.—The three classification committees, 304.—Wide differences between them illustrated, 305.—Historical development, 306.—Increase in items enumerated, 309.—Growing distinction between carload and less-than-carload rates, 310.—Great volume of elaborate rules and descriptions, 312.—Theoretical basis of classification, 314.—Cost of service v. value of service, 315.—Practically, classification based upon rule of thumb, 319.—The "spread" in classification between commodities, 319.—Similarly as between places, 320.—Commodity rates described, 322.—Natural in undeveloped conditions, 323.—Various sorts of commodity rates, 324.—The problem of carload ratings, 325.—Carloads theoretically considered, 326.—Effect upon commercial competition, 327.—New England milk rates, 329.—Mixed carloads, 331.—Minimum carload rates, 322.—Importance of car capacity, 334.—Market capacity and minimum carloads, 336.

Uniform classification for the United States, 337.—Revival of interest since 1906, 339.—Overlapping and conflicting jurisdictions, 340.—Confusion and discrimination, 341.—Anomalies and conflicts illustrated, 342.—Two main obstacles to uniform classification, 345.—Reflection of local trade conditions, 345.—Compromise not satisfactory, 346.—Classifications and distance tariffs interlock, 347.—General conclusions, 351.

CHAPTER X

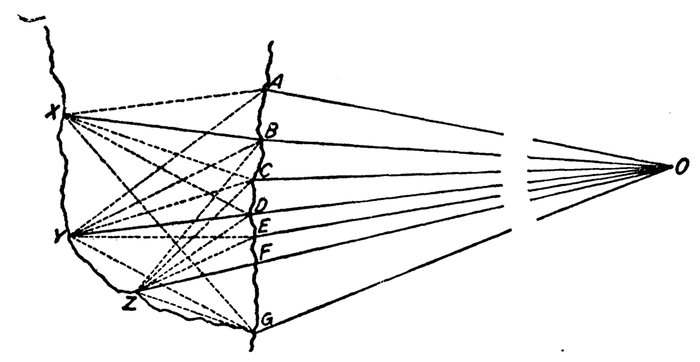

THE TRUNK LINE RATE SYSTEM: A DISTANCE TARIFF

Conditions prevalent in 1875, 356.—Various elements distinguished, 358.—The MacGraham percentage plan, 360.—Bearing upon port differentials, 361.—The final plan described, 363.—Competition at junction points, 368.—Independent transverse railways, 370.—Commercial competition, 372.—Limits of the plan, 375.—Central Traffic Association rules, 376.

CHAPTER XI

SPECIAL RATE PROBLEMS: THE SOUTHERN BASING POINT SYSTEM; TRANSCONTINENTAL RATES; PORT DIFFERENTIALS, ETC.

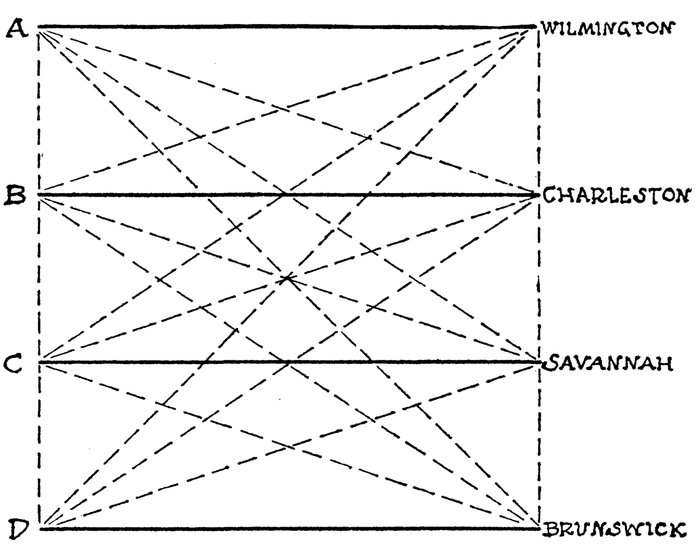

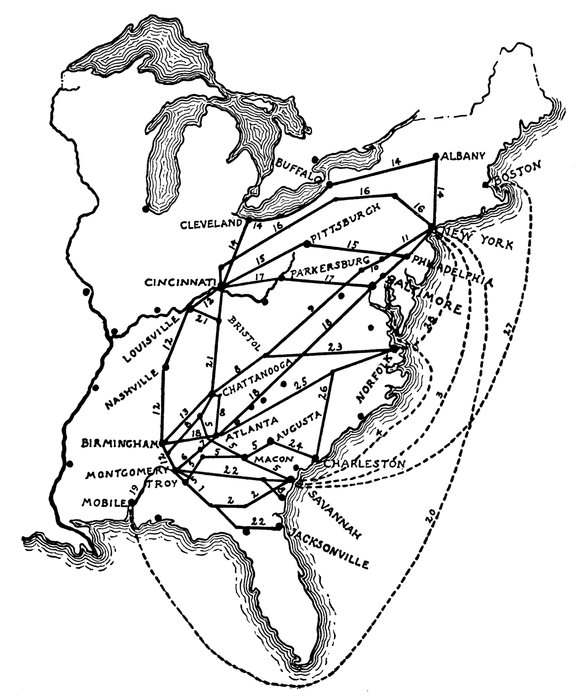

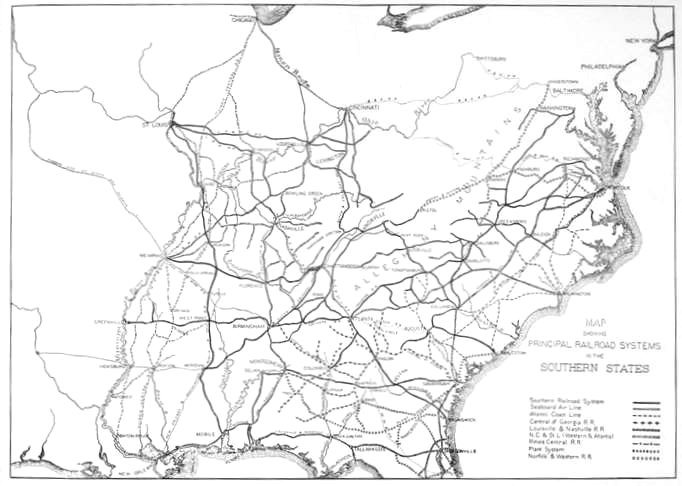

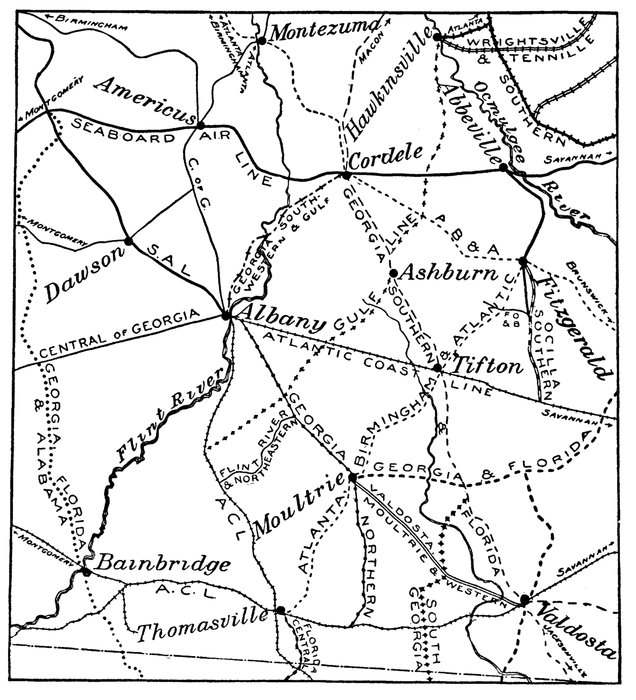

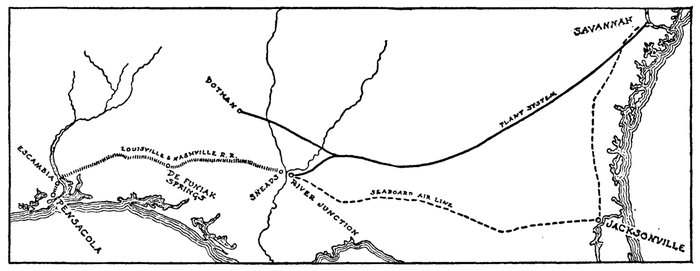

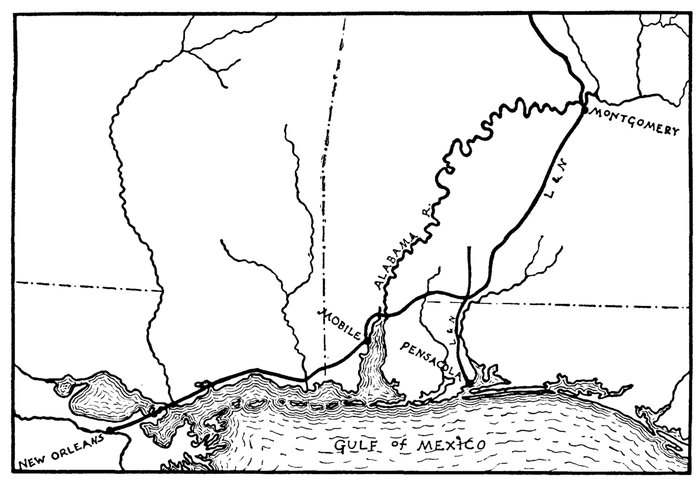

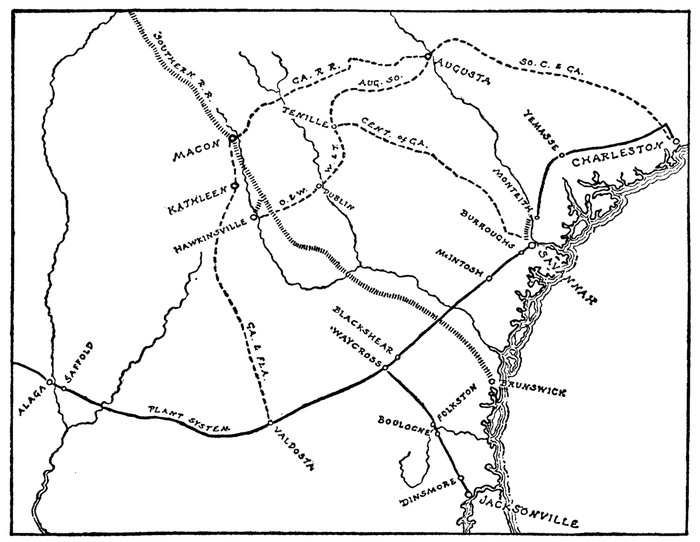

Contrast between the basing point and trunk line systems, 380.—Natural causes in southern territory, 381.—Economic dependence, 381.—[Pg xv]Wide-spread water competition, 382.—High level of rates, 382.—The basing point system described, 383.—Its economic defences, 384.—Early trade centres, 384.—Water competition once more, 385.—Three types of basing point, 387.—Purely artificial ones exemplified, 388.—Different practice among railroads, 390.—Attempts at reform, 391.—Western v. eastern cities, 391.—Effect of recent industrial revival, 392.—The Texas group system, 393.—An outcome of commercial rivalry, 394.—Local competition of trade centres, 395.—Possibly artificial and unstable, 395.—The transcontinental rate system, 395.—High level of charges, 396.—Water competition, 396.—Carload ratings and graded charges, 398.—Competition of jobbing centres, 398.—Canadian differentials, 400.—"Milling-in-transit" and similar practices, 401.—"Floating Cotton," 402.—"Substitution of tonnage," 403.—Seaboard differentials, 403.—Historically considered, 403.—The latest decision, 403.—Import and export rates, 404-409.

CHAPTER XII

THE MOVEMENT OF RATES SINCE 1870; RATE WARS

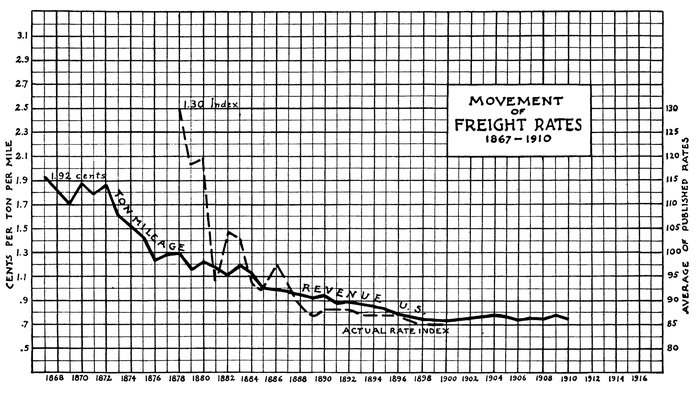

Contrast before and after 1900, 411.—Revenue per ton mile data, 412.—Their advantages and defects, 414.—Nature of the traffic, 416.—Low-grade traffic increasing, 416.—Growing diversification of tonnage, 418.—Present conditions illustrated, 419.—Length of the haul, 421.—The proportion of local and through business, 422.—Effect of volume of traffic, 424.—Proper use of revenue per ton mile, 425.—Index of actual rates, 426.—Its advantages and defects, 427.—Difficulty of following rate changes since 1900, 427.—Passenger fares, 429.—Freight rates and price movements, 430.

Improvement in observance of tariffs, 431.—Conditions in the eighties, 432.—The depression of 1893-1897, 433.—Resumption of prosperity in 1898, 436.—The rate wars of 1903-1906, 438.—Threatened disturbances in 1909-1911, 439.

CHAPTER XIII

THE ACT TO REGULATE COMMERCE OF 1887

Its general significance, 441.—Economic causes, 442.—Growth of interstate traffic, 442.—Earlier Federal laws, 443.—Not lower rates, but end of discriminations sought, 443.—Rebates and favoritism, 445.—Monopoly by means of pooling distrusted, 446.—Speculation and fraud, 447.—Local discrimination, 448.—General unsettlement from rapid growth, 449.—Congressional history of the law, 450.—Its constitutionality, 451.—Summary of its provisions, 452.—Its tentative character, 453.—Radical departure as to rebating, 454.

CHAPTER XIV

1887-1905. EMASCULATION OF THE LAW

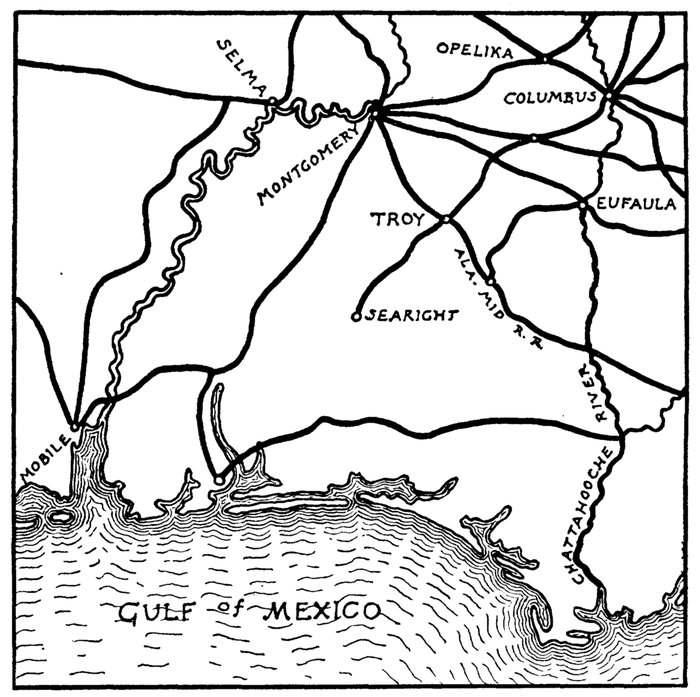

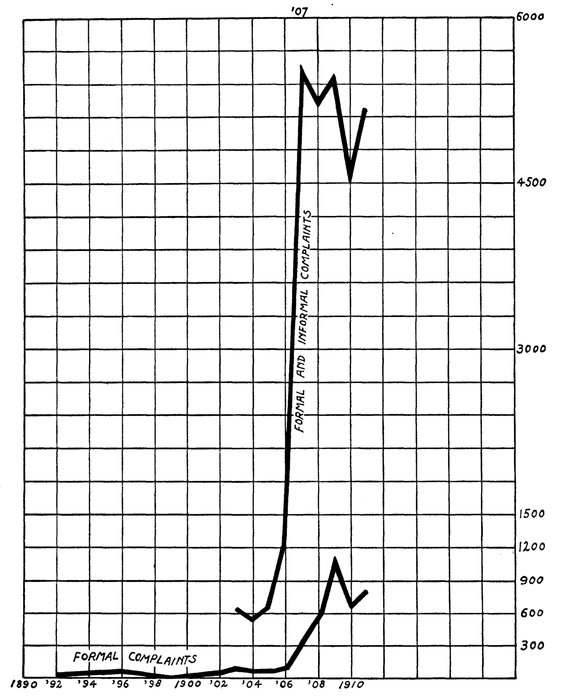

Favorable reception, 456.—First resistance from unwilling witnesses concerning rebates, 457.—Counselman and Brown cases, 458.—The Brimson case, 459.—Relation to Federal Courts unsatisfactory, 460.—Interminable delay, 461.—Original evidence rejected, 461.—The Commission's court record examined, 462.—Rate orders at first obeyed, 467.—The Social Circle case, 468.—Final breakdown in Maximum (Cincinnati) Freight Rate case, 469.—Other functions remaining, 472.—The long and short haul clause interpreted, 474.—The Louisville and Nashville case, 474.—The "independent line" decision, 476.—The Social Circle case again, 478.—"Rare and peculiar cases," 479.—The Alabama Midland (Troy) decision, 481.—Attempted rejuvenation of the long and short haul clause, 483.—The Savannah Naval Stores case, 484.—The dwindling record of complaints, 485.

CHAPTER XV

THE ELKINS AMENDMENTS (1903): THE HEPBURN ACT OF 1906

New causes of unrest in 1899, 487.—The spread of consolidation, 487.—The rise of freight rates, 488.—Concentration of financial power, 490.—The new "trusts," 491.—The Elkins amendments concerning rebates, 492.—Five provisions enumerated, 493.

More general legislation demanded, 494.—Congressional history 1903-1905, 495.—Railway publicity campaign, 496.—President Roosevelt's leadership, 498.—The Hepburn law, 499.—Widened scope, 499.—Rate-making power increased, 500.—Administrative v. judicial regulation, 501.—Objection to judicial control, 503.—Final form of the law, 505.—Broad v. narrow court review, 506.—An unfortunate compromise, 507.—Old rates effective pending review, 508.—Provisions for expedition, 511.—Details concerning rebates, 512.—The commodity clause, 513.—History of its provisions, 514.—Publicity of accounts, 515.—Extreme importance of accounting supervision, 516.—The Hepburn law summarized, 520.

CHAPTER XVI

EFFECTS OF THE LAW OF 1906; JUDICIAL INTERPRETATION, 1905-'10

Large number of complaints filed, 522.—Settlement of many claims, 524.—Fewer new tariffs, 525.—Nature of complaints analyzed, 526.—[Pg xvii]Misrouting of freight, 527.—Car supply and classification rules, 527.—Exclusion from through shipments, 529.—Opening new routes, 530.—Petty grievances considered, 530.—Decisions evenly balanced, 532.—The banana and lumber loading cases, 532.—Freight rate advances, 534.—General investigations, 536.

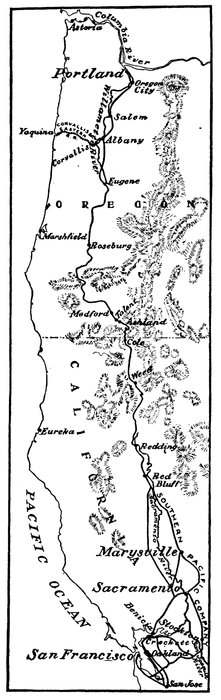

Supreme Court definition of Commission's authority, 538.—The Illinois Central car supply case, 538.—Economic v. legal aspects considered, 540.—The Baltimore and Ohio decision, 541.—The Burnham, Hanna, Munger case, 542.—The Pacific Coast lumber cases, 543.—Decisions revealing legislative defects, 546.—The Orange Routing case, 546.—The Portland Gateway order, 547.—The Commission's power to require testimony affirmed, 549.—The Baird case, 549.—The "Immunity Bath" decision and the Harriman case, 550.—Interpretation of the "commodity clause," 552.—Means of evasion described, 553.

CHAPTER XVII

THE MANN-ELKINS ACT OF 1910

Prompt acquiescence by carriers, 557.—Opposition begins in 1908, 557.—Political developments, 558. President Taft's bill, 559.—Three main features of the new law, 560.—Suspension of rate changes, 561.—Former defective injunction procedure remedied, 562.—The new long and short haul clause, 564.—Provision for water competition, 566.—The new Commerce Court, 566.—Congressional debates, 567.—Jurisdiction of the new Court, 568.—Its defects, 569.—Prosecution transferred to the Department of Justice, 570.—Liability for rate quotations, 571.—Wider scope of Federal authority, 572.—The Railroad Securities Commission, 573—Its report analyzed, 574.—The statute summarized, 578.

CHAPTER XVIII

THE COMMERCE COURT: THE FREIGHT RATE ADVANCES OF 1910

The Commerce Court docket, 581.—The Commerce Court in Congress, 582.—Supreme Court opinions concerning it, 583.—Legal v. economic decisions, 586.—Law points decided, 586.—The Maximum (Cincinnati) Freight Rate case revived, 588.—Real conflict over economic issues, 590.—The Louisville & Nashville case, 590.—The California Lemon case, 592.—Broad v. narrow court review once more, 593.

The freight rate advances of 1910, 594.—Their causes examined, 595.—Weakness of the railroad presentation, 596.—Operating expenses and wages higher, 597.—The argument in rebuttal, 598.—"Scientific management," 598.—The Commission decides adversely, 599.

CHAPTER XIX

THE LONG AND SHORT HAUL CLAUSE: TRANSCONTINENTAL RATES

"Substantially similar circumstances and conditions" stricken out in 1910, 601.—Debate and probable intention of Congress, 602.—Constitutionality of procedure, 603.—Nature of applications for exemption, 604.—Market and water competition, 605.

The Intermountain Rate cases, 610.—The grievances examined, 611.—The "blanket rate" system, 611.—Its causes analyzed, 612.—Previous decisions compared, 615.—Graduated rates proposed by the Commission, 616.—The Commerce Court review, 620.—Water v. commercial competition again, 620.—Absolute v. relative reasonableness, 622.—Legal technicalities, 625.—Minimum v. relative rates, 624.—Constitutionality of minimum rates, 625.

CHAPTER XX

THE CONFLICT OF FEDERAL AND STATE AUTHORITY; OPEN QUESTIONS

History of state railroad commissions, 627.—The legislative unrest since 1900, 628.—New commissions and special laws, 629.—The situation critical, 630.—Particular conflicts illustrated, 631.—The clash in 1907, 632.—Missouri experience, 633.—The Minnesota case, 634.—The Governors join issue, 634.—The Shreveport case, 635.

Control of coastwise steamship lines, 638.—Panama Canal legislation, 641.—The probable effect of the canal upon the railroads, especially the transcontinental lines, 643.

| Index | 649 |

RAILROADS

Significance of geographical factors, 1.—Toll roads before 1820, 2.—The "National pike," 3.—Canals and internal waterways before 1830, 4.—The Erie Canal, 4.—Canals in the West, 6.—First railroad construction after 1830, 7.—Early development in the South, 9.—Importance of small rivers, 10.

The decade 1840-1860, 11.—Slow railway growth, mainly in the East, 12.—Rapid expansion 1848-1857; western river traffic, 13.—Need of north and south railways, 14.—Traffic still mainly local, 15.—Effect of the Civil War, 16.—Rise of New York, 17.—Primitive methods, 17.

The decades 1870-1880, 18.—Trans-Mississippi development, 18.—Pacific Coast routes opened, 19.—Development of export trade in grain and beef, 20.—Trunk line rate wars, 21.—Improvements in operation, 23.—End of canal and river traffic, 24.

The decade 1880-1890, 27.—Phenomenal railway expansion, 28.—Transcontinental trade, 28.—Speculation rampant, 29.—Growth of western manufactures, 30.—Rise of the Gulf ports, 31.—Canadian competition, 33.—General résumé and forecast, 34.

Public land grants, 35.—Direct financial assistance, 37.—History of state aid, 39.—Federal experience with transcontinental roads, 40.

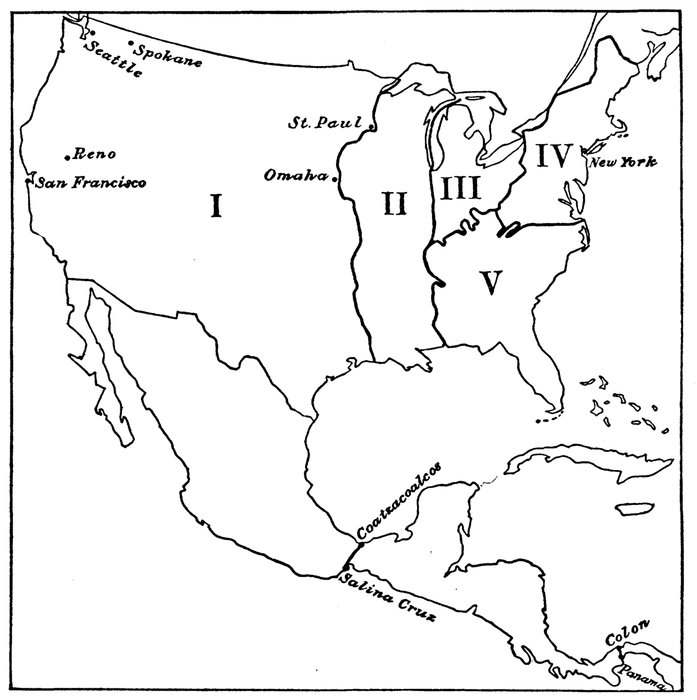

The possibility of a unified nation of ninety odd million souls, spread over a vast territory of three million square miles,—three-fourths of the area of Europe,—was greatly enhanced at the outset by the geographical configuration of the continent of North America. It was fortunate, indeed, that the original thirteen colonies were strictly hemmed in along the Atlantic seaboard, thus being protected against premature expansion. At the same time the north and south direction of this narrow coastal strip, with its variety of climates, soils, natural resources and products, brought about a degree of intercourse and mutual[Pg 2] reliance of the utmost importance. The mere exchange of the dried fish and rum of New England, for the sugar, tobacco, molasses and rice of the southern colonies, paved the way for an acquaintance and intellectual intercourse necessary to the development of national spirit. Throughout the colonial period, the protected coast waters and navigable rivers as far inland as the "fall line," rendered the problem of long distance transportation relatively easy. For everything went by water. Population was compelled to develop the country somewhat intensively, by reason of the difficulty of westward expansion. But this population after the Revolution began to press more and more insistently against the mountain barriers; so that the need of purely artificial means of transportation at right angles to the seaboard became ever more apparent.

The period from the Revolution down to 1829, when Stephenson's "Rocket" made its first successful run between Liverpool and Manchester, attaining a speed of twenty-nine miles per hour, was characterized in the United States by increasing interest in canals and toll roads as means of communication. As involving less expenditure of capital, the highways were naturally developed first. In 1756 the first regular stage between New York and Philadelphia covered the distance in three days, soon to be followed by the "Flying Machine," which made it in two-thirds of that time. Six days were consumed in the stage trip from New York to Boston. But by 1790 a considerable network of toll roads covered the northern territory,—systems which, as in Kentucky by 1840, attained a length of no less than four hundred miles. Post roads linked up such remote points as St. Louis, New Orleans, Nashville, Charleston, and Savannah by 1830. Pennsylvania had made an early beginning in 1806; and by 1822 had subscribed nearly two million dollars to fifty-six turnpike companies and wellnigh a fifth of that sum toward the construction of highway bridges. Most of these roads throughout the country, however, were private enterprises, and, even where aided by the state govern[Pg 3]ments, were imperfectly built and worse maintained, disjointed and roundabout.

The need of a comprehensive highway system, especially for the connection of the coastal belt with the Middle West, early engaged the attention of Congress. Washington seems to have fully appreciated its importance. Ten dollars a ton per hundred miles for cost of haulage by road, necessarily imposed a severe restriction upon the extension of markets. The Federal Congress in 1802 appropriated one-twentieth of the proceeds from the sale of Ohio lands to the construction of such highways. Gallatin's interest in the matter five years later, led to his proposal of an expenditure of $20,000,000 for the purpose. The Cumberland Road or "National Pike" was the result. This great highway started from near the then centre of population in Maryland and cut across the Middle West, half-way between the lakes and the Ohio river. From the upper reaches of the Potomac it followed Braddock's Old Road to Uniontown, Pennsylvania, then by Wheeling over "Zanes trace" to Zanesville, Ohio. From that point on it trended toward St. Louis by way of Columbus and Indianapolis, ending at Vandalia, Illinois. During the space of thirty years about $10,000,000 was expended upon it, and it undoubtedly did much to promote the settlement of the country. But the success of canals and railroads in the meantime sapped the vitality of the movement for further turnpike construction before St. Louis was reached. By the close of the war of 1812, in fact, it had become apparent that highways were destined to serve only as feeders after all; and not as main stems of communication.

Improved riverways and canals constituted the next advance in transportation method. So far as the latter were concerned, although the initial expense was great, the subsequent cost of movement as compared with turnpikes was, of course, low. Especially was this cheapness of movement notable in river traffic. Whereas it was said to cost one-third of the worth of[Pg 4] goods to transport them by land from Philadelphia to Kentucky, the cost of carriage from Illinois down to New Orleans by water was reputed to equal less than five per cent, of their value. Hence the steamboat, invented in 1807 and introduced on the Ohio river in 1811, opened up vast possibilities for enlarged markets. But it was not until the generation of sufficient power to stem the rapid river currents about 1817 that our internal waterways became fully utilized.[2] From that period dates the rapid growth of Pittsburg, Cincinnati, and St. Louis. The real interest of the East in western trade dates from the close of the war of 1812. Even then, however, the natural outlet for the products of the strip of newly settled territory west of the Alleghanies, was still over the mountains to the Atlantic seaboard. Cotton culture in the South had not yet given rise to a large demand for food stuffs in the lower Mississippi valley. It was a long and wellnigh impossible way around by the Gulf of Mexico. Consequently the main attention of the people during the canal period between 1816 and 1840 was focussed upon direct means of communication between the coastal plain and the interior. A few minor artificial waterways, like the Middlesex canal from Boston to Lowell, completed about 1810, proved their entire feasibility from the point of view both of construction and profit. Even earlier than this the Dismal Swamp canal and one along the James river in Virginia had been projected and in part built. But the era of canal construction as such on a large scale cannot be said to begin until after the close of the war of 1812. The most important enterprise, of course, was the building of the Erie Canal to unite the headwaters of the Hudson river with the Great Lakes at Buffalo. This waterway, began in 1817, was completed in eight years and effected a revolution in internal trade. It was not only successful financially, repaying the entire construction in ten years, but it at once rendered New [Pg 5]York the dominant seaport on the Atlantic. Philadelphia was at once relegated to second place. Agricultural products, formerly floated down the Susquehanna to Baltimore, now went directly over the Hudson river route. Branch canals all over New York state served as feeders; and flourishing towns sprang up along the way, especially at junction points. The cost of transportation per ton from Buffalo to New York, formerly $100, promptly dropped to less than one-fourth that sum. By wagon it was said to cost $32 per hundred miles for transport, whereas charges by canal fell to one dollar. Little wonder that the volume of traffic immensely increased, and that, moreover, the balance of power among western centres was at once affected. The future of Chicago, as against St. Louis, was insured; and the long needed outlet to the sea was provided for the agricultural products of the prairie West.

The instant and phenomenal success of the Erie Canal immediately encouraged the prosecution of similar enterprises elsewhere. Philadelphia pushed the construction of a complicated chain of horse railroads, canals and portages in order to reach the Ohio at Pittsburg. In 1834 an entire boat and cargo made the transit successfully. The cost of this enterprise exceeded $10,000,000; but it was expected to provide a successful competitor for the Erie Canal. The latter in the meantime had been linked up with the Ohio river by canals from Cleveland to Portsmouth, from Toledo to Cincinnati, and from Beaver on the Ohio, to Erie on the Lake. By the first of these routes in 1835, no less than 86,000 barrels of flour, 28,000 bushels of wheat and 2,500,000 staves were carried by canal on to New York. Boston and Baltimore were prevented from engaging in similar canal enterprises only by the advent of the railway. Meantime the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was started in 1828 as a joint undertaking of Maryland, Virginia, and the Federal government, to connect the Potomac with the Ohio. It was not completed in fact until 1850, long after its potential usefulness had ceased. Besides these through[Pg 6] routes, canals for the accommodation of local needs were rapidly built in the East. Boston was connected with Lowell; Worcester with Providence; New Haven with the Connecticut river. In Pennsylvania, especially, the anthracite coal industry, developing after 1815, encouraged the building of artificial waterways. The Delaware and Hudson, the Schuylkill, Morris and Lehigh canals were built between 1818 and 1825 along the natural waterways leading out from the hard coal fields. New Jersey connected New York and Philadelphia by the Raritan Canal in 1834-1838 at a cost of nearly $5,000,000; and another canal to connect Delaware and Chesapeake bays was with difficulty, and only by the aid of the Federal government, finally completed about 1825 at a cost of nearly $4,000,000. Further south, many small canals and river improvements were made. The Dismal Swamp enterprise had already connected Chesapeake Bay and the coast waters and sounds of the Carolinas; but provision for slack water navigation of the Tennessee river at Mussel Shoals in Alabama, and of the various branches of the Ohio river in Kentucky was not made until the middle of the thirties.

The open prairies of the West offered the most inviting prospects for canal construction, both because of the dearth of roads and the ease of construction of artificial waterways. Not only through routes to the East, as already described, but local enterprises of various sorts abounded on every side. Chicago was connected with the Mississippi system by way of the Illinois and Michigan Canal; a route across the lower peninsula of Michigan, and many feeders in Indiana and Ohio were built. The demands upon the capital of the country for these purposes during the twenty years after 1815 were enormous; and it was only by resort to state subventions and grants from the Federal government out of the proceeds of sales of public lands, that so much was actually accomplished. State debts aggregating no less than $60,000,000 for canal construction were incurred prior to 1837. Much of this in[Pg 7]vestment proved ultimately unproductive; extravagance and fraud were rife. But the economic results were immediately apparent and highly satisfactory, as witnessed in the higher prices obtainable for all the products of the interior for transportation to the seaboard. Flour, which could be had at three dollars a barrel at Cincinnati in 1826, rose to double that figure by 1835; and corn rose from twelve to thirty-two cents a bushel. The panic of 1837 and the subsequent depression, of course, put a severe check upon further canal building. But an even more potent force was the proved success of the newly invented mode of carriage by railroad. Before 1840 the era of canal construction was definitely at an end. Almost the only exception was the Erie Canal, which continued to prosper by reason of its strategic location. Rates were reduced in 1834; and two years later the canal was widened and deepened to accommodate the ever increasing traffic. Surplus revenues enabled the amortization of its debt; and by 1852 the revenue exceeded three million dollars annually. Although the pressure of railway competition was increasingly felt; as late as 1868, practically all the grain into New York was brought by canal barge. The movement of this canal tonnage, year by year, is shown by the diagram on page 25. As will be seen, it was not until the trunk line rate wars of 1874-1877 that the inferiority of the canal to the railroad, even in this favored instance, was finally demonstrated. The revival of interest in the Erie Canal which has occurred in recent years, leading to the expenditure of millions of dollars by the state of New York in still further enlarging it, is due to an effort to insure the supremacy of the port of New York in export trade against the growing competition of the Gulf ports, which it originally gained when the canal was constructed.

The first serious attempt at railroad operation in the United States was on the Baltimore & Ohio line in 1830. The company, although chartered in 1821, did not begin construction for seven years. It was three years later than this when Peter[Pg 8] Cooper's "Tom Thumb" made a trial run out from Baltimore with a record of thirteen miles per hour. A road from Albany to Schenectady was opened in 1831; and a series of connecting links was rapidly pushed westward across New York state, finally reaching Buffalo in 1842. But prior to 1840, activity in railroad construction was most noticeable in Pennsylvania: partly because of its lack of so admirable a water route to connect it with inland markets as was enjoyed by New York, and partly because of the growth of the coal business which caused the main lines of the Reading Railroad to be laid down as early as 1838. The state of Pennsylvania was busily engaged in improving her existing route over the mountains by replacing the canal and portage portions with rail lines. Pittsburg, which formerly had been five and a half days distant, was thus connected by railroad in 1834. Cars built in the form of boat sections were to be transferred from the rails to canals along part of this route. The Pennsylvania Railroad aiming to provide continuous railway communication over the mountains, was not chartered until 1846; but, nevertheless, as early as 1835 Pennsylvania had over two hundred miles of railway, about one-quarter of the mileage of the United States. New York and New Jersey had about one hundred miles between them, while South Carolina had one hundred and thirty-seven miles. The Baltimore & Ohio during this time was being slowly pushed westward; although it did not reach the Ohio river until 1853, two years after the Erie had, by liberal state aid, been carried to the lakes at Dunkirk, N.Y. Thus it appears that during the decade to 1840 railroad building had progressed unchecked by the panic of 1837. This panic, in fact, by rendering the state construction of canals impossible, may actually have increased the interest in railroad building. The railways of this time were still mainly experimental. They were local and disconnected, serving rather as supplementary to, than as actual competitors of the existing water routes. In Massachusetts and Connecticut the lines[Pg 9] radiating out from seaports were intended to serve only as feeders to coastwise traffic; just as short lines were built along the Great Lakes during the decade to 1850 to bring products out to a connection with the natural water routes. A notable exception was the continuous line which by 1840 was in operation lengthwise of the Atlantic coast plain from New York south to Wilmington, North Carolina. The Camden and Amboy between Philadelphia and New York was operated early in the thirties; about the same time that the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore was completed. Much interesting history centres about the first named road. It seems to have been a notoriously corrupting influence in New Jersey politics from the outset. Public opinion became so roused over its exactions, that a memorial from the merchants of New York to the Thirtieth Congress resulted. The enterprise was the most profitable of all the earlier companies, its net earnings in 1840 amounting to $427,000. In 1855 it paid a twelve per cent. dividend. From Washington south by way of Fredericksburg and Richmond, the southern states could be reached without undertaking the perilous passage round Cape Hatteras. By 1840 the only portions of the original colonies still isolated were New England, at one end, which was still obliged to depend upon Long Island transit to New York by boat; and in the Far South, the back country behind Charleston and Savannah.

Several important economic causes conspired to stimulate railroad construction at a very early time in the southern states.[3] They welcomed the new means of transportation even more eagerly than the wealthier, commercial and more densely populated North. Ever since the invention of the gin in 1793, the production of cotton had grown apace. Profits were so high that all interest in other forms of agriculture waned. Cotton production until about 1817 was mainly confined to [Pg 10]the long narrow strip of Piedmont territory, lying between the sandy "pine barrens" along the coast and the mountains in the rear. This fertile strip—the seat of the plantation system—thus geographically isolated, had only one means of communication with the outer world, namely the coast rivers debouching upon the sea at Charleston, Savannah, or, later on, upon the Gulf at Mobile. But these seaports were not conveniently situated to serve as local trade centres. They were separated from the cotton belt by the intervening pine barrens. The local business of buying the cotton from the planters, and in return supplying their imperative needs for supplies of all sorts, including even foodstuffs which they neglected to raise, was concentrated in a series of towns located at the so-called "fall line" of the rivers. From Alexandria and Richmond on the Potomac and James, round by Augusta, Macon, and Columbia to Montgomery, Alabama, such local centres of importance arose, each one just at the head of navigation. For some years profits were so large that heavy charges for transportation to the sea were patiently borne. But after the opening of the western cotton belt along the Mississippi bottom lands after 1817, the price of cotton experienced a severe decline, greatly to the distress of the older planters. For this reason an insistent demand for improved means of transportation had already brought about great interest in turnpike and canal building. South Carolina at a very early date had expended about two million dollars for these purposes. Steamboats on the smaller rivers were also used. Immediately upon the successful demonstration of traction by steam the aid of the states, cities and individuals was invoked; so that a well planned system of railroads resulted even as early as 1843. The South Carolina Railroad between 1829 and 1833 most successfully operated a pioneer line, its securities being quoted at twenty-five per cent. above par. The Charleston & Hamburg line opened in 1833, one hundred and thirty-seven miles long, was said to be the largest system under one management[Pg 11] in the world. Augusta & Columbia were linked up with the coast. Savannah also penetrated inland to the Piedmont belt by a line finished in 1843 as far as Macon. The interest in a through route to connect Cincinnati and Louisville with Charleston was very keen; and had it not been for the tremendous fall in cotton prices in 1839-1840, the project might have succeeded. As it was, a great railroad convention at Knoxville in 1836 was attended by no less than four hundred delegates from nine different states. It was not so much the mileage of these roads which rendered them notable, as the fact of their intended reliance upon through freight instead of passenger business. Roads in other parts of the country were as yet depending in the main upon passenger traffic or upon the carriage of what we would now call local or parcel freight. These southern lines were built to accommodate traffic in great staple agricultural products—cotton out and foodstuffs in. Unlike the northern roads, also, they early adopted a uniform gauge and sought to promote long distance business. Later developments in the South especially in the direction of improved service were very slow. The northern states speedily outstripped them; but the enterprise of this region in railroad building and operation at the outset has not been fully appreciated.

The decade 1840-1850 was marked by slow growth of the railway net,—everywhere except in New England, where the main lines were being rapidly laid down. The doom of the canal as a competitor had been sealed, to be sure; but the dearth of private capital, except in New England, rendered progress slow until aid from the government was invoked. Until this time private enterprise had been the main reliance. Several important undertakings were now launched. The Pennsylvania Railroad was chartered in 1846, but was not completed to Pittsburg till 1852. The Boston & Albany line was built; and Buffalo had been reached. But neither the Baltimore & Ohio, nor the Erie had yet been pushed to com[Pg 12]pletion. The possibilities of the great Northwest had not dawned upon the people. At the opening of the decade, St. Louis was still almost three times as large as Chicago. Cincinnati was the most important western centre, its prestige being enhanced by the first all-rail line to the Great Lakes at Sandusky, opened in 1848. The relative importance of these inland centres is indicated by their populations. In 1850 these were as follows: Cincinnati, 115,000; Chicago, 30,000; St. Louis, 78,000; and Louisville, 43,000. Cincinnati retained its preëminence until after the Civil War; but by 1880 had dropped to a low third in rank, only half the size of Chicago and two-thirds the size of St. Louis.[4] During the decade to 1850, the Ann Arbor line from Detroit also was pushed on to Chicago in 1852, to cut off the roundabout trip by lake;[5] but St. Louis was still isolated; Indianapolis was barely connected with the Ohio river. The river trade thus still dominated the western situation. In the South one important enterprise monopolized all attention, namely the construction by the state of Georgia of the Western & Atlantic road over the mountains from Atlanta to Chattanooga on the Tennessee river.[6] Atlanta was to become the western terminus of the coast roads, built, as has been said, to provide an outlet to the sea for the Piedmont cotton belt. This new enterprise was to open up a direct route, not alone to the new western South but to the entire Northwest by connecting with a navigable branch of the Ohio. It is an odd fact that at this time the southern ports were nearer the West than the cities of the North Atlantic. Part of the first rush of the Forty-niners to California was by way of Charleston and thence west over the Charleston & Hamburg line. From 1837 on, the Western & Atlantic line was under construction. In the meantime Atlanta had been reached from the east; so that at the beginning of the [Pg 13]next decade, two at least of the main arteries of the southern net were ready for business.

The total mileage of the United States expanded in ten years after 1840 from 2,800 to upwards of 9,000 miles of line. For some time not over four or five hundred miles annually had been constructed; but suddenly the new mileage laid down in 1848 jumped to more than fourteen hundred miles. This was a presage of the great expansion to occur in the next few years,—an expansion made possible partly as a result of important mechanical improvements and inventions. Notable among these was the substitution of the solid iron rail for the primitive method of plating beams with thin strips of iron. The manufacture of rails in the United States, begun in 1844, did much to stimulate the subsequent growth. The repeal of the law of 1832 permitting free entry of railway iron which took place in 1843, marks the beginning of a new era. During these eleven years almost five million dollars in duties on rails was refunded.

The utmost activity in railroad building obtained from 1848 until the panic of 1857, interrupted only by a minor disturbance in 1854. The total mileage expanded more than threefold, attaining a total of 30,000 miles by 1860. A veritable construction mania prevailed in the states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Not very much, relatively, was accomplished in New York and Pennsylvania, and very little in New England, which was already well served. A dominant influence in promoting the new construction at this time was the imperative need of the South for foodstuffs. Cotton culture was in full swing in the lowlands of Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. An enormous steam and flat boat tonnage on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers had grown up to care for this trade.[7] By 1845 the river shipping amounted to nearly two million tons. Fifteen hundred out of four thousand steamboat arrivals at New Orleans in 1859, came from the Ohio river and [Pg 14]the upper Mississippi. The vessels had also greatly increased in size. The flat boats which in 1820 carried only thirty tons of freight, were enlarged tenfold in tonnage and threefold in length by 1855, and in that year first began to be towed back up the river. A rapid increase in coal shipments down stream from Pittsburg also took place during the forties. From 737,000 bushels in 1844, to 22,000,000 bushels in 1855 and 37,900,000 in 1860, represents an enormous development of internal commerce. The lead mines of Missouri shipping through St. Louis had become important after 1832 and quadrupled in volume by 1848, attaining a total of 42,400,000 pigs of sixty pounds each. This traffic steadily dwindled, however, falling away by one half within the next ten years. Memphis was rapidly growing, outstripping the city of Natchez which had formerly played a more important part in the southern trade. But the most important element in this Mississippi river business was the shipment down stream of food stuffs. Produce received at New Orleans was valued at $26,000,000 in 1830, $50,000,000 in 1841, and $185,000,000 in 1860. About thirty per cent. of this consisted of farm produce from the Northwest, together with horses, mules, implements, and clothing. The need of ampler transportation facilities to accommodate all this business was apparent. A response came in plans for new north and south lines of railway. The difficulty of financing these enterprises was solved in part by the expedient of land grants by the different states. These amounted to no less than eight million acres under President Fillmore, attaining a total of nineteen million acres under the Pierce administration. By 1861 these grants, mainly in aid of railroads, had reached a total of no less than 31,600,842 acres,—more than equal to the area of either of the states of Ohio, or New York.[8] The Illinois Central grant in 1851 was the largest among these. Congress in 1850 had made over a tract of 2,700,000 acres to the state of Illinois to be used for this purpose. This gift was [Pg 15]soon followed elsewhere by grants to aid the building of the Mobile & Ohio and the Mississippi Central, together with smaller roads in Alabama and Florida. The Gulf of Mexico was thus reached by through lines from the west in 1858-1861. In other parts of the country railroads were pushed well out in advance of population. The Mississippi was reached by the Rock Island system in 1854, quickly followed by the Alton, the Burlington and the predecessor of the present Northwestern system. The Hannibal & St. Joseph was the first to reach the Missouri river in 1858. There is no doubt that the discovery of gold in California greatly stimulated interest in all these far western enterprises.

Despite this remarkable record of growth, a corresponding development of long-distance communication between different parts of the country had not yet taken place. While the all-rail routes were open, they still consisted in large part of disconnected local lines. The New York Central with difficulty in 1853, and in spite of intense local opposition, succeeded in effecting a consolidation of what were originally eleven separate lines; but the union with the Hudson River Railroad was not to follow until 1869. The Boston & Albany was still a local enterprise, although built with larger ends in view. At this time the possibility of long-distance carriage of grain was only very dimly appreciated. Fast freight lines to operate without breaking bulk over independent roads, constituted the first step in this direction. Such companies on the New York Central in 1855 and on the Erie two years later, were operating in the eastern trunk territory. The so-called Green lines were engaging in long distance business by way of Ohio river connections between the territory to the northwest and the great grain and pork consuming cotton belt. But railroad traffic as a whole was still relatively unimportant as compared with water carriage. The culmination of steadily increasing receipts on the Erie Canal did not occur until 1856. River tonnage went on steadily increasing for another twenty years. The[Pg 16] years just before the war seem to have marked the turning point in respect of canal competition; but the total volume of railroad shipments, nevertheless, still appears insignificant by comparison with the present day. The total traffic in 1859 on the Pennsylvania Railroad was only 353,000 tons east bound and 190,700 tons west bound; while on the New York Central it was 570,900 and 263,400 tons, respectively. The important point was that the cost of shipment was steadily declining. According to H. C. Carey, the passenger rate from Chicago to New York had fallen from about seventy-five dollars to seventeen dollars in 1850; while the freight rate per bushel on wheat had fallen to twenty-seven cents; and per barrel of flour to eighty cents. Nothing but the development of a large surplus production in the West was needed to create a great traffic; and this was dependent upon the spread of population and improvements in agricultural production which had not yet occurred. Transportation as yet waited upon the progress of invention; not in instruments of transportation alone, but in all the other fields of industrial endeavor.

The panic of 1857 and the increasing bitterness of the slavery question, followed by the outbreak of the Civil War, quite diverted the attention of the country from internal development. Railroad construction had already declined from 3,600 miles in 1856 to 1,837 miles in 1860. It fell to less than 700 miles in 1861. Brisk recovery set in after 1865; but it was not until 1868 that any rapid growth again ensued, or even a resumption of the activity of the preceding decade. All of the southern lines were prostrated; the north and south roads, like the Illinois Central system, stood still. The western railway net alone was slowly expanding. The Burlington grew from 168 miles in 1861 to over 400 miles in 1865; and the Chicago & Northwestern then succeeded in bridging the Mississippi. The Erie was still a more important route by fifty per cent., measured by ton mileage, than the New York Central; although its evil days, under the control of Jim Fiske[Pg 17] and Jay Gould in 1866-1869, were about to begin. The Mecca of trade from the Atlantic ports was still St. Louis, although Chicago outgrew it during the decade. The predominant direction of trade is shown by the widespread public interest in New York in the newly opened Western & Atlantic railroad, which by a spur from the Erie road at Salamanca, was to shorten the time of shipment of goods from New York to Cincinnati from one month to a week. The commercial star of New York was steadily rising. A great aid thereto was, of course, the progress of consolidation among the connecting links to Chicago. Vanderbilt and Scott were busily engaged in this constructive work. The former had shifted his interest from steamboats to railroads, and became dominant in the Harlem and Hudson River roads in 1863-1864. Three years later he secured control of the New York Central from Albany west, and consolidated it with the Hudson River line. These trunk line roads, the Pennsylvania and the New York Central, both finally secured connections with Chicago in 1869. A channel for new through currents of trade merely awaited the growth of business.

It is important to realize the relative primitiveness of transportation at the close of the Civil War.[9] The Bessemer steel process was not perfected until the latter half of the decade.[9] Iron rails still rendered light rolling stock necessary. But after 1868 the price of steel rails rapidly declined, from about $166 (currency) per ton in 1867 to $112 in 1872, and to $59 in 1876.[10] This doubtless gave a tremendous impetus to the developments of later years, although its effects were not evident for some time. One of the most troublesome features of the time were the differences of gauge which rendered through traffic difficult. In New York and New England, the standard gauge was four feet eight and one-half inches. West and south of Philadelphia [Pg 18]it was four feet ten inches. In the Far South it was five feet; and in Canada and Maine, either five feet six inches or six feet. Between Chicago and Buffalo five different roads still had no common gauge. Clumsy expedients of shifting car trucks, three rails or extra wide wheel flanges were adopted. Even as late as 1876 Albert Fink refers to the celerity with which trucks could be changed at junction points, not over ten minutes being requisite.[11] The first double tracking in the country, that of the New York Central, was not accomplished until the war period. There was not even a bridge over the Hudson at Albany until 1866, and no bridge at St. Louis, although the Northwestern had bridged the Mississippi higher up. No night trains were run generally. No export grain trade existed, although feeble beginnings had been apparent at New York for some years. Philadelphia did not even have a trunk line as late as the end of the war; and neither Boston nor Philadelphia had regular steamer lines to Europe. For the great staples of trade, the canals and rivers were largely utilized. The Erie Canal during the war, took twice as much freight as the Erie and New York Central together. Even in 1865 the ton mileage of the Erie Canal—844,000,000—compared with a ton mileage of 265,000,000 for the New York Central and 388,000,000 for the Erie Railroad. And in 1872, eighty-five per cent of the freight between New York and Philadelphia still went by water.

Railroad construction during the next decade to 1880 was extremely active. East of the Mississippi developments were confined in the main to building branches and feeders. One new through line in the East was opened, by the entrance of the Baltimore & Ohio into New York in 1873 and into Chicago in the following year. Another important enterprise was the building of the Air Line route to connect Atlanta with Richmond by a road traversing the fertile Piedmont belt. The[Pg 19] completion by the state of Massachusetts of the Hoosac Tunnel line, providing a new outlet to the west from Boston, was also a notable achievement. This route was at last opened in 1874 after a painful experience extending over twenty years, involving an expenditure by the state of about $17,000,000. Most of the new railroad building of the seventies took place in the upper Mississippi valley. The states of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, (eastern) Nebraska and Kansas were rapidly gridironed with new lines. Much of this construction took place after 1868, activity culminating in 1871 with the building of no less than 7,379 miles of line. The panic of 1873 put an end to all this, except in California where expansion went on unabated. Nearly one thousand miles of new line were added to the systems of this state during the five years to 1878,—nearly doubling its mileage during this period. Elsewhere in the country little was accomplished during the protracted hard times. In 1875, for instance, only seventeen hundred miles were constructed. This cessation of development did not change for the better until the resumption of general prosperity in 1878. The net result of ten years building was, nevertheless, considerable, represented by an expansion from 53,000 to upwards of 93,000 miles of line. Railroad building, in fact, increased about two and one-half times as fast as population. So that by 1880 the United States was already more amply furnished with transportation mileage than any country in Europe.

Among the important events to be associated with this period was the opening of the first transcontinental route, marked by the joining of the Union and Central Pacific railroads in 1869. The history of its construction under liberal land grants from the Federal government belongs in another place. Aside from the political effect, the economic results were immediate. Population at once flowed over onto the Pacific slope. And a large volume of trade was at once deflected from the sea route round Cape Horn. The value of goods shipped by water between New York and San Francisco, which[Pg 20] in 1869 amounted to $70,000,000, fell in the next year to $18,600,000, and in 1872 to less than $10,000,000. The success of the enterprise, together with growing interest in the Pacific states, doubtless led to the opening of construction of the Northern Pacific as a transcontinental route in 1870.

The rapid development of an export trade in grain to Europe between 1870 and 1874 was a direct result of improvements in agriculture and the opening up of a surplus grain-producing area. As yet this territory lay mainly east and south of Chicago. Even as late as 1882, over four-fifths of the eastbound trunk line traffic originated not further west than Illinois. Wisconsin and Iowa contributed less than ten per cent. of this business. The methods of handling wheat were still quite primitive. During the Civil War thousands of men were employed to unload the grain by hand, every tenth barrel being weighed. Elevators had been used in Chicago for some time but no eastern city had them until 1861. Prior to 1872, when the first grain elevator was set up at Baltimore, the cost of thus unloading grain by hand amounted to four or five cents per bushel. At Boston until 1867, all the export grain was still unloaded back of the city and hauled across to the waterfront.

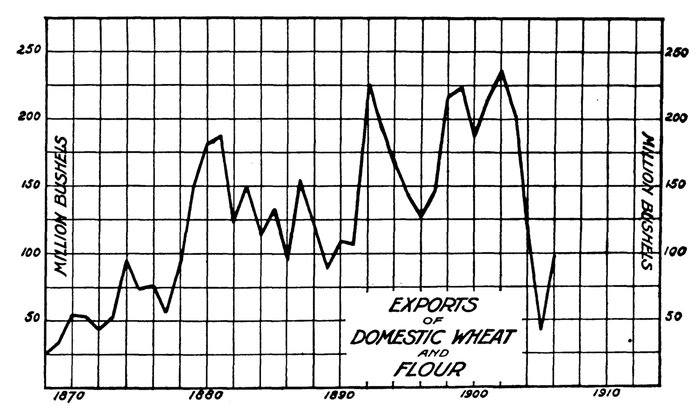

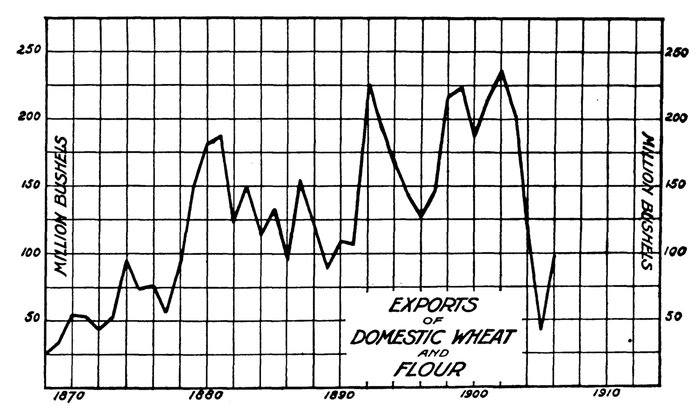

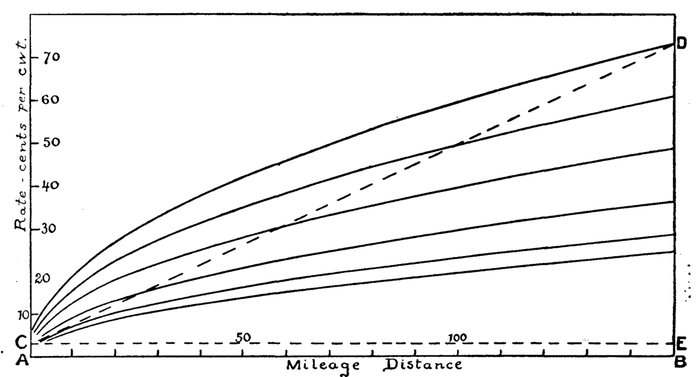

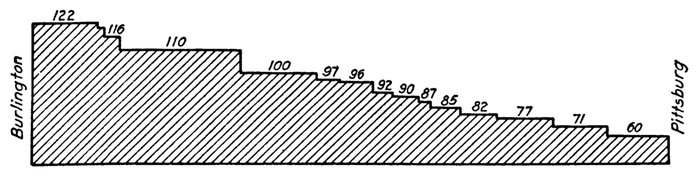

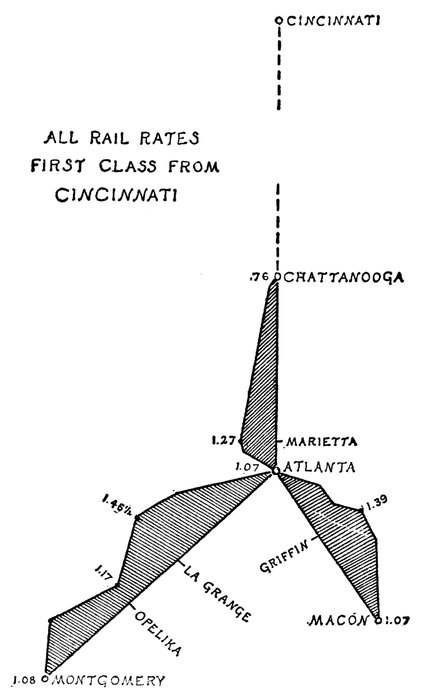

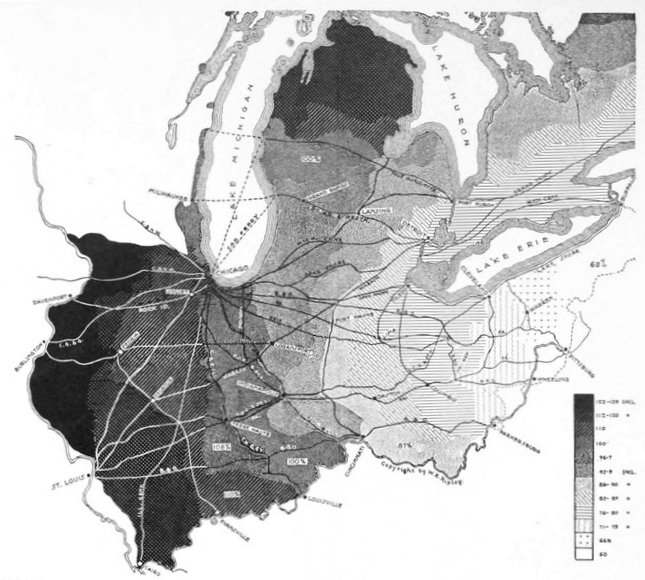

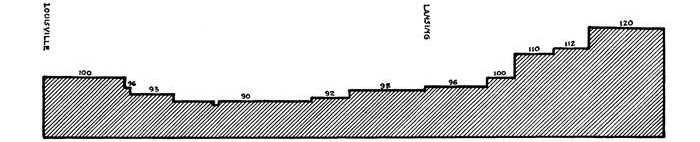

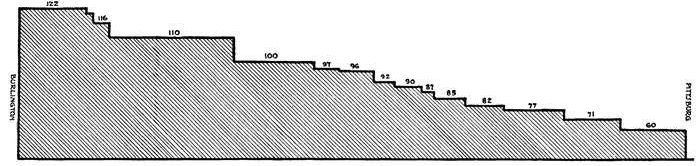

The volume of exportable surplus products of the country rose rapidly after 1870. An increase from five or six bushels of wheat production per capita in 1860, to nearly nine bushels in 1879, left a large margin for foreign sale. The growth of such traffic, big with importance for the carriers, is indicated by the opposite diagram. The large total of 59,000,000 bushels of wheat and (equivalent) wheat flour reached in 1862, partly as a result of the closing of markets in the southern states, was not again surpassed for more than a decade. The most notable increase ensued after 1873, when the level rose about fifty per cent., to become established thereafter upon a permanently higher plane. A second sudden boost occurred again in 1877 when wheat exports rose rapidly to a total of 180,000,000 bushels within three years. The disastrous failure[Pg 21] of European crops in 1879, with a coincident bumper yield in the United States, led to the immediate climax of the movement in 1881. These exports, moreover, which fifty years earlier, owing to the cost of carriage, were almost exclusively in the form of flour, were now in 1880 about three-fourths constituted of raw wheat. Examination of the diagram with its steep pyramid of development at this time is convincing as to the stimulus thereby given to the railway interests. Foreign trade in cattle and beef products also enormously increased during these years. In 1876 only 244 steers were exported, while in 1877, 71,794, and in 1881, 134,000 head were shipped abroad. The value of preserved meats exported quadrupled in one year after 1877, and grew eightfold by 1880. Doubtless part of this disposition of products abroad during the seventies was due to a cessation of demand at home owing to the prevalent hard times; but the important discovery was incidentally made that the demand abroad existed, and merely required cheap transportation for its successful development.

EXPORTS OF DOMESTIC WHEAT AND FLOUR

The second step necessary for permanently developing railroad business was a lowering of the charges. This was first brought about during the seventies through unregulated com[Pg 22]petition between the trunk lines. The fiercest warfare occurred during the years immediately following the entrance of the Baltimore and Ohio and the Grand Trunk railroads into Chicago in 1874. This was some five years after the Pennsylvania and the New York Central had consolidated their through lines to the same point. These two original rivals had already slashed rates indiscriminately. Charges of $1.88 and 82 cents for first-and fourth-class freight from Chicago to New York in 1868, had already for a brief period in the following year dropped to a uniform rate of twenty-five cents for all business. As Hadley justly observes, such rates could not long prevail; and for the next few years nominal rates of one dollar, and one dollar and fifty cents for first class, and sixty and eighty cents for fourth class obtained. The outbreak of open warfare between the Baltimore & Ohio and the Pennsylvania over the charges made by the latter for the use of its lines between Philadelphia and New York, occurred in 1874. Grain rates of sixty cents per hundred pounds from Chicago to New York during 1873 fell to forty cents in 1874 and to thirty cents in 1875. Special or commodity rates were often as low as twelve cents. After a year's truce, only partially observed by the leading participants, discord again prevailed during 1876. The commercial rivalries of seaboard cities now became involved. Different or specially favorable rates had been accorded to Baltimore and Philadelphia as compared with New York since 1869.[12] Rates finally fell lower than ever before. This was especially true of grain. The published rate in March, 1876, was forty-five cents per hundred pounds from Chicago to New York. In May it fell to twenty cents—a rate almost as low as prevails today with all modern improvements in methods of conducting the business. Westbound rates dropped correspondingly. Quotations from New York to Chicago at twenty-five cents per hundred pounds first class, and sixteen cents fourth class were freely given. Actual rates were often much lower than this.

Rival cities again intervened and finally the whole matter was of necessity referred for arbitration to a commission. Even then both the Erie and the Baltimore & Ohio roads were well advanced on the road to bankruptcy. For us, however, the immediate result of importance was a permanent reduction of the general level of freight rates, not alone for the trunk line territory but for the entire country. The diagram on page 413 shows this plainly. From an average revenue per ton of freight moved one mile of 1.92 cents in 1868, intermittently upheld until 1872, the fall of over one-third to about 1.1 cents in 1882 was sudden and continuous. The end was not yet. The renewed outbreak of a rate war between the trunk lines in 1881 and again in 1884 led to further reductions. The decision in 1882 of the Thurman Commission on Differentials settled nothing.[13] All kinds of traffic were affected. Immigrants were carried from New York to Chicago for $1.00 a head. East-bound grain rates were as low as eight cents. At last, late in 1885, the warfare was terminated by an elaborate pooling agreement. These struggles brought about great reductions in the revenue of the carriers concerned; but declines in rates after this period were, in the main, more gradual, with short intervals of relief interspersed.

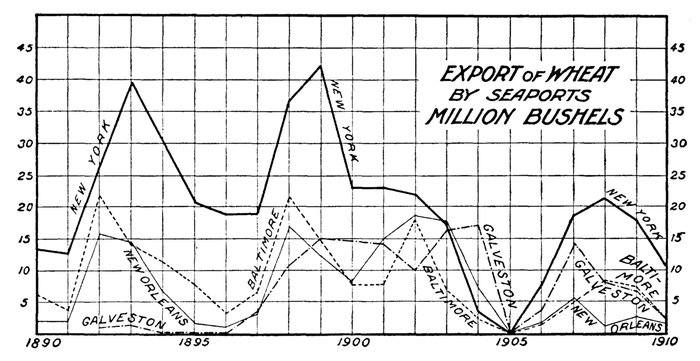

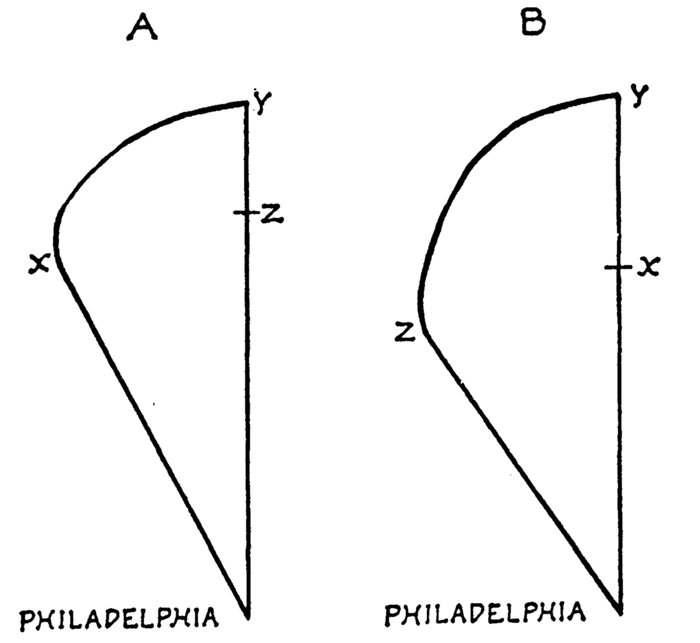

One immediate result of these lower freight rates was the impetus given to economy and systematic operation. This is the period when, as we have said, pooling as a device for restraint of competition first appeared in the "Evening" contracts on beef shipments in the West, in the notable Southern Railway & Steamship Association in 1874 and in the trunk line pool in 1877. Agreement between the anthracite coal roads began about 1872 and has continued with increasing effectiveness ever since.[14] This was also the heyday of the through freight lines which were now operating from every important western centre. In 1876 the first attempt at a systematic scheme of rate adjustment [Pg 24]between competing localities was made in trunk line territory.[15] Order was indeed emerging out of chaos. In respect of operation, larger locomotives and cars and longer trains were rapidly coming into use. On the Lake Shore the average train load in 1870 was 137 tons. Nine years later it had risen to 213 tons. The widespread substitution of steel for iron rails was not yet to follow for some time. For in 1880 only three-tenths of the mileage of the country was laid with steel. This proportion rose to eight-tenths in 1890. It was doubtless this change during the eighties which made possible the heavy decrease in operating expenses which occurred during the five years subsequent to 1881. It appears, indeed, as if the need of economy was enforced by the decline of rates in progress; but, as usual, the supply of economies waited upon the demand and, in fact, tarried well behind it. To this circumstance may be attributed some of the financial hardships suffered by the roads during the ensuing interval between the reduction of rates during the seventies and the mechanical improvements of the succeeding decade. An incidental result of the rate wars of this period, it may also be noted, was the readjustment of the relative shares of the great seaports in foreign business. Philadelphia, especially, increased its quota of exports from about eleven per cent, in 1860 to over twenty per cent. in 1880. Much of this was gained, however, from the southern ports, as the relative status of Baltimore, New York, and Boston remained about the same.

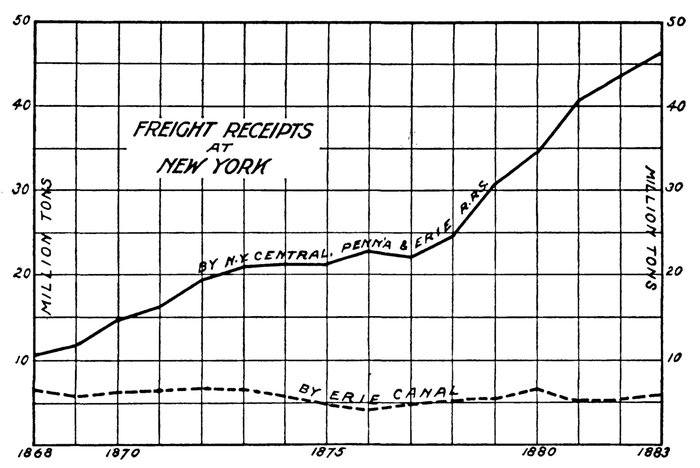

A second important consequence of the severe decline in railroad rates during the seventies, was the permanent supersession of canals and riverways in favor of railroads as means of transportation. The Erie Canal outlasted all the other artificial water routes, most of which had succumbed to rail competition by the close of the Civil War. But even as late as 1868, practically all of the grain arriving at New York came by canal. The change, when it occurred, came suddenly.

FREIGHT RECEIPTS AT NEW YORK

No canal could meet the fierce slashing of rates which suddenly supervened on the rail lines. Since 1855, when the canal carried twice the traffic of all the trunk lines, until 1861-1862 when the rail and water lines were about even, the railroads had steadily gained in tonnage.[16] The turning point was reached in 1872 when the canal traffic actually began to decline. Between 1871 and 1876 the aggregate tonnage (both ways) on the New York canals fell away about half, spasmodically recovered during the great expansion of exports in 1879-1880, held constant for five years, and thereafter steadily dwindled away. As the accompanying diagram shows, the rise of railroad tonnage was rapid up to 1873. Thereafter for several years during the actual panic, despite the railroad wars and low rates, no great change occurred. But by 1876, eighty-three per cent. of all-grain receipts at Atlantic ports came by rail; and over nine-tenths of all the commerce between East and West had left the water routes. At New York the three [Pg 26]main railroads carried six times the traffic of all the state canals in 1880. After that time the canal barges were loaded only with coal, lime, sand, cement, and similar low-grade traffic. So that in the rapid expansion of business, which, as our diagram shows, occurred after 1878, the canal shared not at all. The disparity between east-and westbound tonnage was notably great. In 1870 this eastbound traffic was about three times as great as the tonnage west bound. In 1881 it was seven and one-half times as great, declining thereafter to a proportion of about 6.5 to 1 during the late nineties. This inequality, of course, whetted the appetite of the carriers for back loads to fill the westbound trains, and undoubtedly gave an impetus to rate disturbance. The rate wars led by the New York Central during 1881 were largely due to this fact.

As for water carriage elsewhere, the rivers soon followed the canals in steady decline of relative importance. On the southern streams, such as the Cumberland and Tennessee, the principal diversion to the railroads of traffic in foodstuffs south bound from the West, took place in the five years subsequent to 1866.[17] High-water mark in the Mississippi trade was reached in 1879, the year of the completion of the jetties for the improvement of navigation at the mouth of the river. A steady decline thereafter has ensued down to the present day. New Orleans had then only recently engaged in foreign trade in grain. Exports of wheat and flour (equivalent) had suddenly risen from less than 1,000,000 bushels in 1875 to over 12,000,000 bushels in 1880. At this time this came principally by river. It was nearly ten years later before the Illinois Central actively engaged in such export business. But when the railroads finally seized upon it, the river trade was doomed. The only exception to this decrease of inland water transportation occurred on the Great Lakes. The carriage of coal, iron ore, and lumber rapidly increased. Through the Detroit river, [Pg 27]the tonnage grew from 9,000,000 in 1873 to 20,000,000 tons in 1880; and through the St. Mary's Canal from 403,000 in 1860 to 1,734,000 tons in 1880. Inasmuch as a fair proportion of this rapidly growing business was ultimately destined to reach the seaboard either as raw material or in the form of manufactures, this water traffic contributed to, rather than lessened the prosperity of the trunk lines operating east of the lakes.