by

T. McKENNY HUGHES, M.A., F.R.S., F.G.S., F.S.A.

Woodwardian Professor of Geology

with

A Description of the Shippea Man

by

ALEXANDER MACALISTER, M.A., F.R.S., M.D., Sc.D.

Professor of Anatomy

Cambridge:

at the University Press

1916

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

C. F. CLAY, Manager

London: FETTER LANE, E.C.

Edinburgh: 100 PRINCES STREET

New York: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS

Bombay, Calcutta and Madras: MACMILLAN AND Co., Ltd.

Toronto: J. M. DENT AND SONS, Ltd.

Tokyo: THE MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA

All rights reserved

| PAGE | |

| Geography of the Fenland | 1 |

| Subsidence of the Valley of the Cam | 2 |

| Turbiferous and Areniferous Series | 3 |

| Absence of Elephant and Rhinoceros in Turbiferous Series | 6 |

| Absence of Peat in Areniferous Series | 6 |

| Fen Beds not all Peat | 7 |

| Sections in Alluvium | 7 |

| Peat; Trees etc.: Tarn and Hill Peat; Spongy Peat and Floating Islands; Bog-oak and Bog-iron | 13 |

| Marl: Shell Marl and Precipitated Marl | 17 |

| The Wash: Cockle Beds (Heacham):Buttery Clay (Littleport) | 18 |

| Littleport District | 18 |

| Buttery Clay | 19 |

| The Age of the Fen Beds | 20 |

| Palaeontology of Fens | 20 |

| Birds | 25 |

| Man | 27 |

| Description of the Shippea man by Prof. A. Macalister | 30 |

The Fenland is a buried basin behind a breached barrier. It is the "drowned" lower end of a valley system in which glacial, marine, estuarine, fluviatile, and subaerial deposits have gradually accumulated, while the area has been intermittently depressed until much of the Fenland is now many feet below high water in the adjoining seas.

The history of the denudation which produced the large geographical features upon which the character of the Fenland depends needs no long discussion, as there are numerous other districts where different stages of the same action can be observed.

In the Weald for instance where the Darent and the Medway once ran off higher ground over the chalk to the north, cutting down their channels through what became the North Downs, as the more rapidly denuded beds on the south of the barrier were being lowered. The character of the basin is less clear in this case because it is cut off by the sea on the east, but the cutting down of the gorges pari passu with the denudation of the hinterland can be well seen.

The Thames near Oxford began to run in its present course when the land was high enough to let the river flow eastward over the outcrops of Oolitic limestones which, by the denudation of the clay lands on the west, by and by stood out as ridges through which the river still holds its course to the sea—the lowering of the clay lands on the west having to wait for the deepening of the gorges through the limestone ridges. A submergence which would allow the sea to ebb and flow through these widening gaps would produce conditions there similar to those of our fenlands. So also the Witham and the Till kept on lowering their basin in the Lias and Trias, while their united waters cut down the gorge near Lincoln through a barrier now 250 feet high.

The basin of the Humber gives us an example of a more advanced stage in the process. The river once found its way to the sea at a much higher level over the outcrops of Jurassic and Cretaceous rocks west of Hull, cutting down and widening the opening, while the Yorkshire Ouse, with the Aire, the Calder and other tributaries, were levelling the New Red Sandstone plain and valleys west of the barrier and tapping more and more of the water from the uplands beyond. The equivalent of the Wash is not seen behind the barrier in the estuary of the Humber, but the tidal water runs far up the river and produces the fertile estuarine silt known as the Warp.

The Fenland is only an example of a still further stage in this process. The Great Ouse and its tributaries kept on levelling the Gault and Kimmeridge and Oxford Clays at the back of the chalk barrier which once crossed the Wash between Hunstanton and Skegness.

The lowlands thus formed lie in the basin of the Great Ouse which includes the Fenland, while the Fenland includes more than the Fens properly defined, so that things recorded as found in the Fenland may be much older than the Fen deposits.

During the slow denudation which resulted in the formation of this basin many things happened. There were intermittent and probably irregular movements of elevation and depression. Glacial conditions supervened and passed away.

The proof of this may be seen in the Sections, Figs. 1, 2 and 3, pp. 8, 9 and 10.

At Sutton Bridge the alluvium has been proved to a depth of 73 feet resting on Boulder Clay. At Impington the Boulder Clay runs down to a depth of 86 feet below the surface level of the alluvium. That means that this part of the valley was scooped out before the glacial deposits were dropped in it, and that the bottom of the ancient valley is now far below sea level.

In front of Jesus College, gravel with Elephas primigenius was excavated down to a depth of 30 feet below the street, while in the Paddocks behind Trinity College the still more recent alluvium was proved to a depth of 45 feet, i.e. 16 feet below O.D. These facts indicate a comparatively recent subsidence along the valley, as no river could scoop out its bed below sea level.

We need not for our present purpose stop to enquire whether this depression was confined to the line of the valley or was part of more widespread East Anglian movements which are not so easy to detect on the higher ground. From the above-mentioned sections it is clear that the denudation, which resulted in the formation of the basin in the lowest hollow of which the Fen Beds lie, was a slow process begun and carried on long before glacial conditions prevailed and before the gravel terraces were formed.

As soon as the sea began to ebb and flow through the opening in the barrier, the conditions were greatly altered and we see the results of the conflict between the mud-carrying upland waters and the beach-forming sea.

The Fen Beds belong to the last stage and, notwithstanding their great local differences, seem all to belong to one continuous series. Seeing then that their chief characteristic is that they commonly contain beds of peat it may be convenient to form a word from the late Latin turba, turf or peat, and call them Turbiferous to distinguish them from the Areniferous series which consists almost entirely of sands and gravels.

When the land had sunk so far that the velocity of the streams was checked over the widening estuary and on the other hand the tide and wind waves had more free access, some outfalls got choked and others opened; turbid water sometimes spread over the flats and left mud or was elsewhere filtered through rank plant growth so that it stood clear in meres and swamps, allowing the formation of peat unmixed with earthy sediment.

Banks are naturally formed along the margin of rivers by the settling down of sand and mud when the waters overflow, as seen on a large scale along the Mississippi, the Po, as well as along the Humber and its tributaries.

The effect of a break down of the banks is very different. A great hole is scooped out by the outrush, and the mud, sand and gravel deposited in a fanshape according to its degree of coarseness and specific gravity.

A good example of this was seen in the disastrous Mid-Level flood at Lynn in 1862[1] and the more recent outburst near Denver in the winter of 1914-15[2] , of which accounts were published in contemporary newspapers. The varied accompanying phenomena can be well studied in the process of warping in Yorkshire or the colmata in Italy.

This was a much commoner catastrophe in old times, before the banks were artificially raised, and, as the streams could never get back into their old raised channel, this accounts for the network of ancient river beds which intersect the Fens.

The bottom of the Turbiferous alluvium is always, as far as my experience goes, sharply defined. This of course cannot be seen in a borehole or very small section.

The surface of the older deposits seems to have been often washed clean either by the encroaching sea or by the upland flood waters.

In saying that there is an absence of sand and gravel in the Fen Beds we must be careful not to force this description too far. For when the first encroaching water was washing away any pre-existing superficial deposits the first material left as the base of the Fen Beds must have depended upon the character of the underlying strata, the velocity of the water and other circumstances.

This is well seen in the Whittlesea brickpit where an ancient gravel with marine shells rests on the Oxford Clay and over the gravel there creeps the base of the Turbiferous series. It here consists chiefly of white marl which thins out to the left of the section and above becomes full of vegetable matter until it passes up into peat, over which there is a flood-water loam.

About a mile west-north-west of Little Downham near Ely, and within a couple of hundred yards of Hythe, the Fen Beds were seen in a deep cut carried close to the gravel hill which here stretches out north into the Fens.

They consist at the base of material washed down from the spur of gravel and sand of the Areniferous series against which the Fen Beds here abut.

This basement bed is succeeded by beds of silt and peat of no great thickness as they are near the margin of the swamp.

When any considerable thickness of the older Areniferous gravels has been preserved, the base of the Turbiferous series is smooth or only gently undulating. But where only small patches or pot-holes of gravel remain, there the top of the clay has been contorted and over-folded so as often to contain irregularly curved pipes and even isolated nests of sand and gravel[3]. The base of the Areniferous gravel must generally have been thrown down upon clay which had been clean cut to an even surface by denudation without any soaking of the surface or isolated heaps of gravel sinking into the clay under alternation of dry and wet conditions, such as would puddle the surface under the heaps and allow the masses of heavy gravel to sink in pipes and troughs. These small outlying patches of gravel are sometimes so little disturbed that we leave them in the Areniferous, whereas they are sometimes so obviously rearranged that we must include them in the Turbiferous series, taking care not to include derivative bones from the older in our list of fossils from the newer series.

The basement beds of the Turbiferous or Newer Alluvial Fen Beds are clearly separated by their stratification from the Areniferous or Older Alluvial Terrace Beds down the sloping margin of which they creep, but there is not anywhere, as far as I am aware, any passage or dovetailing of the Fen Beds into the gravel of the river terraces, while the difference in the fauna is very marked.

It is however from such sections as those just described that the erroneous view arose that the Elephant and Rhinoceros occurred in the older Fen Beds. It is true that they have been found under peat in the Fenland, but that is only where the gravel spurs of the Old Alluvial Terraces or Areniferous Series have passed under the newer Fen Beds.

I saw the remains of Rhinoceros tichorhinus in the gravel beds belonging to the older or Areniferous Series at Little Downham, and from the base of the gravel in the Whittlesea brickpit I obtained a fine lower molar of Elephas antiquus. This was, however, not in the Gravel, but squeezed into the soft surface of the underlying Jurassic Clay.

There have never been any remains of Elephant or Rhinoceros found in the Turbiferous series.

It is not easy to realise what the conditions were during the formation of the later Terrace Gravels (Barnwell type), and, if it is a fact, why there was not then, as in later times, a marshy peat-bearing area here and there between the torrential deposits of the upper streams near the foot of the hills and the region where the tide met the upland waters. A few plants have been found in the Barnwell gravel but they are very rare in this series. The older Terrace Gravel (Barrington type) might be expected to furnish evidence of the existence of abundant vegetation if we are right in assigning it to about the age of the peaty deposits overlying the Weybourn Crag. But at present we have no evidence of any such deposit in the Cambridge gravels.

Although there are great masses of vegetable matter formed in the swamps of tropical regions, peat is essentially a product of northern climes. Pliny[4] evidently refers to peat as used in Friesland but not as a thing with which he was familiar.

It must not, however, be imagined that the Fen Beds consist wholly or even chiefly of peat. As we travel north from Cambridge the surface of the alluvium is brown earth for miles and only here and there shows the black surface of peat. The numerous ditches for draining the land confirm this observation, and when we have the opportunity of examining excavations carried down to great depths into the alluvium we usually find only a little peat on the surface or in thin beds alternating with silt and clay and marl. Sometimes, but only sometimes, we have evidence of the growth of peat for a long time, then of the incoming of turbid water leaving beds of clay, then again of the tranquil growth of peat. All this points to changes of local conditions and shifting channels during a gradual sinking of the area, for some of the peat is below sea level.

I believe that the volume of clay is much greater than that of peat, although from the common occurrence of peat on the surface and clay in the depth the area over which peat is seen is greater. We have not, however, the data for estimating the proportion of each.

In embayed corners along the river even above Cambridge we find little patches of peat, while on the other hand in deep excavations near the middle of the valley we find only thin streaks of peat or peaty silt. In the trial boreholes at the Backs of the Colleges there was only this kind of record of former swamp vegetation.

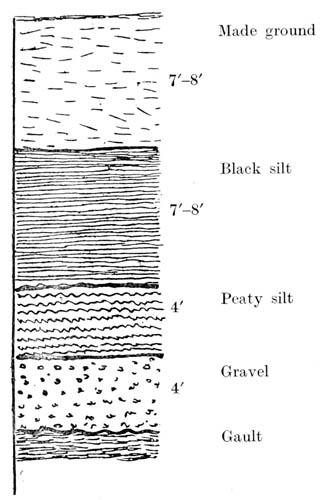

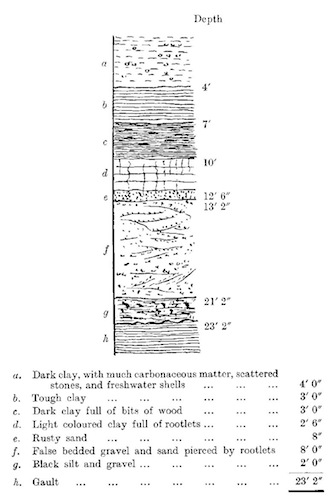

In digging the foundations for the chimney of the Electric Lighting Works opposite Magdalene College the following section was seen (Fig. 1, p. 8).

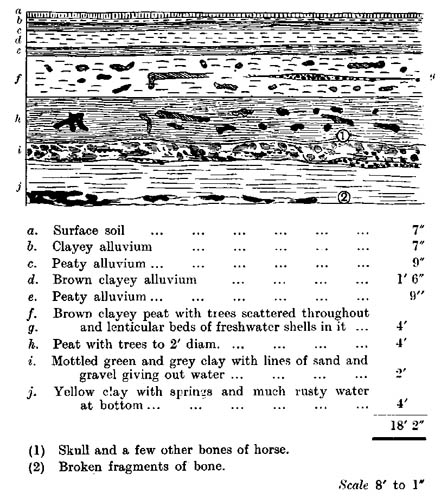

Under the new Tennis Courts in Park Parade facing Mid-summer Common the section was somewhat different (Fig. 2, p. 9).

While in the pit dug some years ago by Mr Bullock at the other end of the Parade at the lower end of Portugal Place in the south-east corner of the Common there was a section very similar to the last (Fig. 3, p. 10).

Fig. 1. Section seen in foundations of chimney for Electric Lighting Works near river opposite Magdalene College, July, 1892.

These three sections, immediately north of Cambridge where the valley of the Cam opens out on to the Fens, are important as showing the variations right across the alluvium from side to side and the absence, here at any rate, of any indication of a constant sequence distinctly pointing to important geographical changes. A section seen under Pembroke College Boat House gave 16 feet of clay and peaty silt on the black gravel which here, as in the borings at the Backs of the Colleges, forms the base of the alluvium. About half way down were bones of horse and stag, but I do not believe that these are of any great antiquity, probably not earlier than mediaeval.

Fig. 2. Section seen in digging foundations of Tennis Courts on Midsummer Common, Cambridge.

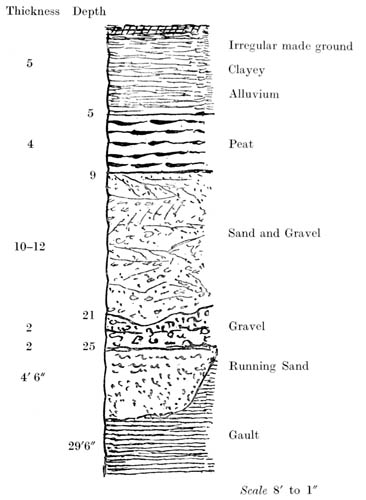

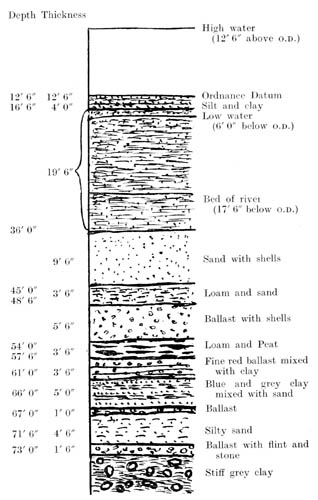

Lower down the river near Ely a most important and interesting section has recently been exposed. A new bridge was built over the Ouse near the railway station and to obtain material for easing the gradient up to the bridge a pit was sunk close to it on the east side of the river, and was carried down to the Kimmeridge Clay thus giving a clear section through the whole of the alluvium (Fig. 4, p. 11).

Fig. 3. Section seen in Bullock's Pit in S.E. corner of Midsummer Common.

It will be noticed that there is very little peat here and all of it was below O.D. The upper four feet of the clayey peat (f) looked as if the vegetable matter had been transported, perhaps from peat beds being destroyed by the river higher up, and been carried down in flood with the clay, while the lower four feet of peat (h) was only a cleaner sample of the same, before the river had cut down into the clay. The trees in both f and h were not trees that had grown on the spot and had been blown down, but were broken, water-worn, and evidently transported.

Fig. 4. Section seen in pit dug for material for making up the roadway east of the new bridge over the Ouse by the railway station. Ely, 1910.

If now we travel about 30 miles a little west of north we shall arrive near the shore of the Wash about half way across its southern coast line at Sutton Bridge. Here I had an opportunity of seeing the material of which the alluvium is composed. With a view to securing a sound base for the foundation of the piers of the Midland and Great Northern Railway bridge an excavation was made through the whole of the Fen Beds down to the Boulder Clay which as I have already stated was reached at a depth of 73 feet. The clerk of the works kindly gave me the following measurements (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Section seen at Sutton Bridge.

Here again we see that the only peat is a bed between three and four feet in thickness of mixed loam and peat more than 40 feet below mean sea level.

From these sections it is clear that along the direct and more permanent outfall from Cambridge to the north, peat forms but a small part of the Fen Beds.

Peat is a substance of so much value as fuel, of such importance to the agriculturist, of such commercial value in what we may call its by-products, and of such scientific interest in the history of its formation and the remains which its antiseptic properties have preserved, that it has, as might be expected, a large literature of its own.

I have before me a list of more than 150 references to peat or to the Fens.

When we turn aside into the areas cut off by spurs of gravel and islands of Jurassic rock, we find wide and deep masses of peat which has grown and been preserved from denudation in these embayed and isolated areas. Burwell Fen, for instance, protected on the north and west by the Cretaceous ridge of Wicken and the Jurassic ridge of Upware, furnishes most of the peat used in the surrounding district. If we travel about two miles to the north-west from the pit dug near the railway station (see Fig. 4, p. 11) over the hill on which Ely stands, we shall come to West Fen, where there is a great mass of peat which has grown in a basin now almost quite surrounded by Kimmeridge Clay. In this there is a great quantity of timber at a small depth from the surface. The tree trunks almost all lie with their root-end to the south-west, but some are broken off, some are uprooted, telling clearly a story of growth on the peat which had increased and swelled till the surface was lifted above the level of floods. Then some change—perhaps more rapid subsidence, perhaps changes in the outfalls—let in flood water, the roots rotted and a storm from the south-west, which was the most exposed side and the direction of the prevalent winds, laid them low. The frequent occurrence of large funguses, Hypoxylon, Polyporus, etc., points to conditions at times unfavourable to the healthy growth of timber.

It is worth noting when trying to read the story of the Fens as recorded by their fallen trees that in all forests we find now and then a few trees blown down together though the surrounding trees are left. This may be the result of a fierce eddy in the cycloidal path of the storm, but more commonly it seems to be due to the fact that every tree has its "play," like a fishing rod, and recurring gusts, not coinciding with its rhythm, sometimes catch it at a disadvantage and break or blow it down.

The story told by the West Fen trees is quite different from that told by the water-borne and water-worn trunks in the section by Ely station.

The same variable conditions prevailed also in the more westerly tracts of the Fen Basin, but the above examples are sufficient for our present purpose.

From the large numbers of trees found in some localities and from records referring to parts of the Fens as forest it has sometimes been supposed that the Fens were well wooded, but forest did not generally and does not now always mean a wood, as for example in the case of the deer forests of Scotland.

When Ingulph[5] says that portions of the Fenland were disafforested by Henry I, Stephen, Henry II, and Richard, who gave permission to build upon the marshes, this probably meant that they no longer preserved them so strictly, but allowed people to build on the gravel banks and islands in them.

Dugdale, recording a stricter enforcement of game-laws, quotes proceedings against certain persons in Whittlesea, Thorney and Ramsey for having "wasted all the fen of Kynges-delfe of the alders, hassacks and rushes so that the King's deer could not harbour there." He does not mention forest trees.

In the growth and accidents of vegetation in a swamp there are some circumstances which are of importance to note with a view to the interpretation of the results observed in the Fens.

For instance in fine weather there is a constant lifting and floating of the confervoid algae which grow on the muddy bed of the stream. This is brought about by the development of gas under the sun's influence in the thick fibrous growth of the alga. The little bubbles give it a silvery gleam and by and by produce sufficient buoyancy in the mass to tear it out and make it rise to the surface dropping fine mud as it goes and thus making the water turbid. Other plants, such as Utricularia, Duckweed, etc., have their period of flotation, and in the "Breaking of the Mere" in Shropshire we have a similar phenomenon. In the "Floating Island" on Derwentwater the same sort of thing is seen with coarser plants. All these processes are going on in the meres and in the streams which meander through the Fens and did so more freely before their reclamation. But besides this, when the top of the spongy peat is raised above the water level and dries by evaporation, then heath, ferns and other plants and at last trees grow on it, until accident submerges it all again.

This at once shows why we often find an upper peat with a different group of plant remains resting upon a lower peat with plants that grow under water.

The most conspicuous examples of these various kinds of peat we see in the mountainous regions of the North and West, where the highest hills are often capped with peat from eight to ten feet in thickness, creeping over the brow and hanging on the steep mountain sides. Sometimes, close by, we see the gradual growth of peat from the margin of a tarn where only water-weeds can flourish.

The "Hill Peat" is made up of Sphagnum and other mosses and of ferns and heather.

The "Tarn Peat" of conferva, potamogeton, reeds, etc.

As Hill Peat now grows on the heights and steeps where no water can stand and Tarn Peat in lakes and ponds lying in the hollows of the mountains and moors, so the changes in the outfalls and the swelling and sinking of the peat have given us in the Fens, here the results of a dry surface with its heather and ferns and trees, and there products of water-weeds only, and, from the nature of the case, the subaerial growth is apt to be above the subaqueous.

One explanation of the growth of peat under both of these two very different geographical conditions is probably the absence of earthworms. The work of the earthworm is to drag down and destroy decaying vegetable matter and to cast the mineral soil on to the surface, but earthworms cannot live in water or in waterlogged land, and where there are no earthworms the decaying vegetation accumulates in layer after layer upon the surface, modified only by newer growths. Some years ago a great flood kept the land along the Bin Brook under water for several days and the earthworms were all killed, covering the paddock in front of St John's New Buildings in such numbers that when they began to decompose it was quite disagreeable to walk that way. It reminded me of the effects of storm on the cocklebeds at the mouth of the Medway, where the shells were washed out of the mud, the animals died on the shore and the empty shells were in time washed round the coast of Sheppey to the sheltered corner at Shellness. Here they lie some ten feet deep and are dug to furnish the material for London pathways.

In those cases when the storm had passed the earthworms and the cockles came again, but the Hill Peat is always full of water retained by the spongy Sphagnum and similar plants, and the Fens are or were continually, and in some places continuously, submerged and no earthworms could live under such conditions.

The blackness of peat and of bog-oak may be largely but certainly not wholly due to carbonaceous matter. Iron must play an important part. There is in the Sedgwick Museum part of the trunk of a Sussex oak which had grown over some iron railings and extended some eight inches or more beyond the outside of the part which was originally driven in to hold the rails. Mr Kett came upon the buried iron when sawing up the tree in his works and kindly gave it to me. From the iron a deep black stain has travelled with the sap along the grain, as if the iron of the rail and the tannin of the oak had combined to produce an ink. The well-known occurrence of bog-iron in peat strengthens this suggestion. An opportunity of observing this enveloping growth of wood round iron railings is offered in front of No. 1, Benet Place, Lensfield Road.

The trees in the Fens often lie at a small depth and when exposed to surface changes perish by splitting along the medullary rays.

It is not clear how long it takes to impart a peaty stain to bone, but we do find a difference between those which are undoubtedly very old and others which we have reason to believe may be more recent. Compare the almost black bones of the beaver, for instance, with the light brown bones of the otter in the two mounted skeletons in the Sedgwick Museum.

"Marl," as commonly used, is Clay or Carbonate of Lime of a clayey texture or any mixture of these.

Beds of shell marl tell the same tale as the peat. Shells do not accumulate to any extent in the bed of a river. They are pounded up and decomposed or rolled along and buried where mud or gravel finds a resting place. Only sometimes, where things of small specific gravity are gathered in holes and embayed corners, a layer of freshwater shells may be seen.

But to produce a bed of pure shell marl the quantity of dead shells must be very large and the amount of sediment carried over the area very small, while the margin of the pond or mere in which the formation of such a bed is possible must have an abundant growth of confervoid algae and other water plants to furnish sustenance for the molluscs. Shell marl therefore suggests ponds and meres. Of course it must be borne in mind that in a region of hard water, such as is yielded in springs all along the outcrop of the chalk, there is often a considerable precipitation of carbonate of lime, especially where such plants as Chara help to collect it, as the Callothrix and Leptothrix help to throw down the Geyserite.

These beds of white marls, whether due to shells or to precipitation, are thus of great importance for our present enquiry as they throw light on the history of the Fens.

We should have few opportunities of examining the marl were it not for its value to the agriculturist. As it consists of clay and lime, it is not only a useful fertiliser but also helps to retain the dusty peat, which when dry and pulverised is easily blown away. Moreover, as the marl occurs at a small depth and often over large areas, it can commonly be obtained by trenching on the ground where it is most wanted.

We have now carried our examination of the Fen Beds up to the sea, but to understand this interesting area we must cross the sea bank and see what is happening in the Wash. There is no peat being formed there, nor is there any quantity of drifted vegetable matter such as might form peat. There are marginal forest beds near Hunstanton and Holme, for instance, and it is not clear whether they point to submergence or to the former existence of sand dunes or shingle beaches sufficient to keep out the sea and allow the growth of trees below high water level behind the barrier, such as may be seen at Braunton Burrows, near Westward Ho, or at the mouth of the Somme. What is the most conspicuous character of the Wash is that the upland waters, now controlled as to their outlet, keep open the troughs and deeps while tidal action throws up a number of shifting banks of mud, sand and gravel, many of which are left dry at low water. Along the quieter marginal portions fine sediment is laid down, and relaid when storms have disturbed the surface. On these cockles and other estuarine molluscs thrive. Before the sea banks were constructed these tidal flats extended much further inland.

In the light of this evidence let us examine the Fen Beds east of Littleport, a district of great interest not only from its geographical position in relation to the Fens but also from the remains recently discovered there.

Looking north and west there is no high ground between us and the Wash. If we could sweep out the soft superficial deposits and abolish the sea banks the tide would still ebb and flow over the whole area.

If we look north and east we see the high ground stretching from Downham Market to Stoke Ferry and sweeping round to the south by Methwold and Feltwell and the islands of Hilgay and Southery, thus enclosing a great bay into which the Wissey on the north and the Brandon River on the south deliver the waters collected on the eastern chalk uplands.

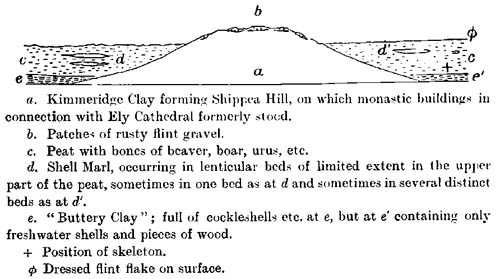

The island known as Shippea Hill marks the trend of an ancient barrier blocking the northward course of the river Lark. (Fig. 6, p. 29.)

Here, then, it seems probable that we might find evidence of a local change from the conditions we now see in the Wash and those which have resulted in the formation of the Fens.

In deep trenching in the Fen between Littleport and Shippea Hill in order to obtain clay for laying on the peaty surface a very fine unctuous deposit was found at a depth of four or five feet. The overlying Fen Beds were chiefly peat with lenticular beds of white marl and grey clay, obviously laid down from time to time in small depressions in the surface of the peat. This marl was often largely made up of, or was at any rate full of, freshwater shells but sometimes showed evidence of having been gathered on the stems of Chara which on perishing have left small cylindrical hollows penetrating the partly consolidated marl. Under these beds of peat and marl there was the unctuous clay, which is sometimes referred to as the Buttery Clay. It is an estuarine deposit like that mentioned above as occurring in the Wash off Heacham, for instance. It contains shells of Cardium edule, Tellina (Tacoma) balthica, Scrobicularia piperata, and other estuarine shells, some of which had the valves adherent or rather adjoining, for the ligament had perished. Mrs Luddington has in her collection the bones of the Urus, Wild Boar and Beaver, obtained from the peat above this Buttery Clay.

On the other or south-western side of Shippea Hill, which is an island of Kimmeridge Clay, we get further into the embayed and isolated portions of the Fen and we find more peat in proportion to the other deposits although it is very thin. There are still small lenticular beds of white marl similar to that nearer Littleport and the peat rests upon Buttery Clay of unknown thickness. In this part, however, no shells have yet been noticed. Near Shippea Hill the peat has recently been trenched with a view to obtaining clay with which to dress the surface of the peat and it was here, at a depth of four feet from the surface and four inches above the Buttery Clay, that the human bones described below (pp. 27-35) were found.

Now we may enquire what are the limits within which we may speculate as to the age of the Fen Beds.

These Turbiferous deposits all belong to one stage, though it may be one of long duration. They are sharply separated from the Areniferous deposits, i.e. the sands and gravels of the terraces and spurs which always pass under and, in fairly large sections, can always be clearly distinguished from the resorted layers at the base of the Fen Beds.

There is no definite chronological succession which will hold throughout the Fens. The variations observed are geographical—clay, marl, peat, etc., alternating in different order in different localities and subaerial, fluviatile, estuarine, and marine, having only a changing topographical significance.

The Fen Beds crept over an area where the underlying formation had been undergoing vicissitudes due to slow geographical changes—changes which, being at sea level and near the conflict of tides and upland water, produced irregular but often important results.

There is not in the Fens any continuous record of what took place between the age in which the Little Downham Rhinoceros was buried in the gravel and that in which the Neolithic hunters poleaxed the Urus in the peat near Burwell.

Nor do we find any constant succession in the fauna and flora in the sections in the Fens any more than we find a uniform distribution of plants and animals over the surface to-day. The most numerous and largest specimens of the Urus I have obtained from near Isleham: the best preserved Beaver bones from Burwell. Modern changes of conditions have limited the district in which the fen fern (Thelypteris) or the swallow-tailed butterfly may now be seen; but nature in old times produced as great changes in local conditions as those now due to human agency.

When we compare the fauna of the Areniferous Series with that of the Turbiferous, although there is not an entire sweeping away of the older vertebrate and invertebrate forms of life and an introduction of newer, there is a marked change in the whole facies.

There is plenty of evidence about Cambridge of the gradual extermination of species still going on. Indeed, I feel inclined to say that there is no such thing as a Holocene age. I remember land shells being common of which it is difficult now to find live specimens, and my wife[6] has shown how the mollusca are being differentiated in isolated ponds left here and there along the ancient river courses above the town.

But we have not in older beds of the Turbiferous or newer beds of the Areniferous Series any suggestion of continuity between the two. There must have been between them an unrepresented period of considerable duration in which very important changes were brought about. Perhaps it was then that England became an island and unsuitable for most of the life of the Areniferous age.

Not only have we in the Turbiferous as compared with the Areniferous Series a change of facies but we have many "representative forms," a point to which that keen naturalist, Edward Forbes, always attached great importance.

We have for instance in the Fen Beds the Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) with his flat pig-like skull, instead of the Grizzly (Ursus ferox) of the Gravels with his broad skull and front bombé.

If we turn to the horned cattle we shall find a confirmation of the view that there was not an entire break between the Turbiferous and Areniferous fauna for the Urus (Bos primigenius) occurs in both. This species became extinct in Britain in the Turbiferous period and before the coming of the Romans, for no trace of it seems to have been found with Roman remains in this country; and indeed when we remember the numerous tribes, the dense population and high civilisation of the natives of Britain in Roman times it seems improbable that they can have tolerated such a formidable beast as this wild bull around their cultivated land.

Some confusion has arisen as to the description and the names of the Urus and the Bison. Caesar, who was not a big game hunter and probably never saw either, has given under the name Urus a description which evidently mixes up the characters of both. Both existed on the continent down to quite recent times and the Bison is still found in Poland, but later writers also have evidently confounded them. For instance, the Augsburg picture of the Urus is correct, but Herberstein's, which also is said to represent the Urus, is obviously that of a Bison. I have gone into this question more fully elsewhere[7].

The Urus (Bos primigenius) is common in the Fen Beds and is of special importance for our present enquiry, as there is in the Sedgwick Museum a skull of this species found in Burwell Fen with a Neolithic flint implement sticking in it. The implement is thin, nearly parallel sided, rough dressed, except on the front edge which is ground, and it is made of the black south-country flint. It is very different in every respect from the thick bulging implements with curved outlines, which being made of the mottled grey north-country flint or of felstone or greenstone suggest importation from a different and probably more northerly source.

This gives us a useful synchronism of peat, a Neolithic implement of a special well-marked type, and the Urus.

The Bison is the characteristic ox of the Gravels and never occurs in the Fen Beds; while the Urus, as I have pointed out above, occurs in both the Turbiferous and Areniferous deposits.

Bos longifrons is the characteristic ox of the Fen Beds and never occurs in the Gravels. It is the breed which the Romans found here, and we dig up its bones almost wherever we find Roman remains. I cannot adduce any satisfactory evidence that it was wild, that is to say more wild than the Welsh cattle or ponies or sheep which roam freely over wide tracts of almost uninhabited country. This species, like the Urus, has horns pointing forward, but the cattle introduced by the Romans had upturned lyre-shaped horns, as in the modern Italian, the Chillingham or our typical uncrossed Ayrshire breed, and soon we notice the effect of crossing the small native cattle (Bos longifrons) with the larger Roman breed.

The Horse appears to have lived continuously throughout Pleistocene times down to the present day and to have been always used for food. Unfortunately the skull of a horse is thin and fragile and therefore it has been difficult to obtain a series sufficiently complete to found any considerable generalisations upon it. The animal found in the peat and alluvium appears to have been a small sized, long faced pony.

The appearances and reappearances of the different kinds of deer is a very interesting question, but it will be more easily treated when I come to speak of the Gravels of East Anglia. I will only point out now that neither of the deer with palmated antlers properly belongs to the Turbiferous series. The great Irish Elk (Cervus megacerus) has not been found in the Fen Beds. Indeed it is not clear that in Ireland it occurs in the peat. The most careful and trustworthy descriptions seem to show that its bones lie either in or on top of the clays on which the peat grew.

The other and smaller deer with palmated antlers, namely, the Fallow deer (Cervus dama), were reintroduced, probably by the Romans, and although some of them have got buried in the alluvium or newer peat in the course of the 1500 years or so that they have been hunted in royal warrens in East Anglia, they cannot be regarded as indigenous or indicative of climate or other local conditions.

Remains of the Red deer (Cervus elaphus) and of the Roe deer (Cervus capreolus) are common in the Fen Beds; both occur in the Gravels also; and both are still wild in the British Isles. Unlike the Red deer, which lives on the open moorland, the Roe deer lives in woods and forests. And this is an interesting fact in its bearing upon our inferences as to the character of the country before the reclamation of the Fens and the destruction of the plateau forest. The open downs and the spurs and islands of the fenlands offered the Red deer a congenial feeding ground, while the thickets on the edge of the upland forest and the bosky patches along the margins of the lowland swamps provided covert for the Roe deer. Sheep and goat are found in the peat and the alluvium, but it is not easy to tell the age of the bones. They do generally appear to be of that lighter brown colour which is characteristic of remains from newer peat as compared with the black bones which seem to belong to the older and more decomposed peat. The sheep is probably a late introduction and is never found in the Terrace Gravel (see Geol. Mag. Decade 2, Vol. X, No. 10, p. 454).

The Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) is fairly common.

It is remarkable that we get very few remains of Wolf, although it is not much more than 200 years since the last was killed. There is in the Sedgwick Museum one fairly complete skeleton, found a long time ago in Burwell Fen and I have recently obtained another from the same locality. There do not seem to be any obvious and constant characters by which we can distinguish a wolf from a dog, and Britain was celebrated for its large and fierce dogs. The bones of the Eskimo dogs are very wolf-like, but they are frequently crossed with wolf.

Perhaps the most interesting animal whose remains are found in the Fens is the Beaver. Why do we not find here and there a beaver dam? Perhaps it is because we have not been on the look-out for it, and the peat-cutters would not have seen anything remarkable in the occurrence of a quantity of timber anywhere in the Fens. We must suppose that the peat which often contains whole forests of trees and even canoes would have preserved the timber of the beaver dam. It is an animal too which might have contributed largely towards the formation of the Fens by holding up and diverting meandering streams. Perhaps it did not make dams down in the Fens, and the skeletons we find are those of stray individuals or of dead animals which have floated down from dams near Trumpington or Chesterford; very suitable places for them. We want more evidence about the fen beaver.

I have heard that there are beavers in the Danube which do not make dams, but among those introduced into this country in recent years the dam building instinct seems to have survived the change. The beavers on the Marquis of Bute's property in Scotland cut down trees and built dams as did the beavers in Sir Edmund Loder's park in Sussex, and even in the Zoological Gardens they recently constructed a "lodge." We have not found the beaver in the Gravels.

Part of the skull of a Walrus was brought to us a long time ago and said to have been found in the peat. But it is a very suspicious case. It does not look like a bone that had been long entombed in peat, and we are not so far from the coast as to make it improbable that it was carried there by some sailor returning home from northern seas.

Bones of Cetaceans are thrown up on the shore near Hunstanton, and Seals are still not uncommon in the Wash, so that we need not attach much importance to the occurrence in marine silt of Whale, Grampus, Porpoise, and such like.

We have paid much attention to the birds of the Fens, partly because of the occurrence of some unexpected species, and also because of the absence, so far as our collection goes, of species of which we should expect to find large numbers.

Perhaps the most interesting are the remains of Pelican (P. crispus or onocrotalus)[8]. Of this we have two bones, not associated nor in the same state of preservation. The determination we have on the authority of Alphonse Milne Edwards and Professor Alfred Newton. One of the bones is that of a bird so young that it cannot have flown over but shows that it must have been hatched or carried here.

Of the Crane (Grus cinerea) we have a great number of bones but of the common Heron not one. I have placed a recent skeleton of heron in the case to help us to look out for and determine any that may turn up. Bones of the Bittern (Botaurus or Ardea stellaris) are quite common, as are those of the Mute or tame Swan (Cygnus olor) as well as of the Hooper or wild Swan (Cygnus musicus or ferus). Goose (Anser) and Duck (Anas) are not so numerous as one might have expected. The Grey Goose (Anser ferus) and the Mallard (Anas boscas) are the most common, but other species are found, as for instance Anas grecca. We have also the Red Breasted Merganser (Mergus serrator), and the Smew (Mergus albellus), the Razor Bill (Alea tarda), the Woodcock (Scolopax rusticola), the Water Hen (Gallinula chloropus) and a few bones of a Limicoline bird, most likely a lapwing. We have found the skull, but no more, of the White-tailed or Sea Eagle (Haliaetus albicilla). The whole is a strangely small collection considering all the circumstances.

We find in the Fens of course everything of later date, down to the drowned animals of last winter's storm, or the stranded pike left when the flood went down. It is a curious fact and very like instinct at fault that in floods the pike wander into shallow water and linger in the hollows till too late to get back to the river, so that large numbers of them are found dead when the water has soaked in or evaporated. An old man told me that he well remembered when pike were more abundant they used to dig holes along the margin when the flood was rising and when it went down commonly found several fine pike in them. This explains why we so often find the bones of pike in the peat, but where did the pike get into a habit so little conducive to the survival of the species?

Although we notice at the present day a constant change in the mollusca, their general continuity throughout the long ages from pre-glacial times is a very remarkable fact.

The presence of Corbicula fluminalis and Unio littoralis in the Gravels characterized by the cold-climate group of mammals such as Rhinoceros tichorhinus and Elephas primigenius, the absence of those shells from the deposits in which Rh. merckii and E. antiquus are the representative forms, and their existence now only in more southern latitudes, as France, Sicily or the Nile, but not in our Turbiferous Series, lay before us a series of apparent inconsistencies not easy of explanation.

Every step in the line of enquiry we have been following, from whatever point of view we have regarded the evidence, has forced upon us the conclusion that a long interval elapsed between the Areniferous and Turbiferous series as seen in the Fens; and yet, having regard to the geographical history of the area with which we commenced, we cannot but feel that the various deposits represent only episodes in a continuous slow development due to changes of level both here and further afield and the accidents incidental to denudation.

But the particular deposits which we are examining happen to have been laid down near sea level where small changes produce great effects. We may feel assured that over the adjoining higher ground the changes would have been imperceptible when they were occurring and the results hardly noticeable.

If the Fen Beds include nearly the whole of the Neolithic stage the idea that glacial conditions then prevailed over the adjoining higher ground is quite untenable.

So far everything has taught us that the Fens occupy a well-defined position in the evolution of the geographical features of East Anglia and also that the fauna is distinctive, and, having regard to the whole facies, quite different from that of the sands and gravels which occur at various levels all round and pass under the Turbiferous Series of the Fens.

We will now enquire what is the place of these deposits in the "hierarchy" based upon the remains of man and his handiwork.

No Palaeolithic remains have ever been found in the Fen deposits. We must not infer from this that there is everywhere evidence of a similar break or long interval of time between the Palaeolithic and Neolithic ages. There are elsewhere remains of man and his handiwork which we must refer to later Palaeolithic than anything found in the Areniferous Series just near the Fen Beds, and there are, not far off, remains of man's handiwork which appear to belong to the Neolithic age, but to an earlier part of it than anything yet found in association with the Fen Beds.

The newer Palaeolithic remains referred to occur chiefly in caves and the older Neolithic objects are for the most part transitional forms of implement found on the surface in various places around but outside the Fens and in the great manufactures of implements at Cissbury and Grimes Graves, in which we can study the embryology of Neolithic implements and observe the development of forms suggested by those of Palaeolithic age or by nature. The sequence and classification adopted in these groups, both those of later Palaeolithic and those of earlier Neolithic age, are confirmed by an examination of the contemporary fauna; the Areniferous facies prevailing in the caves and the Turbiferous facies characterising the pits and refuse-heaps of Cissbury and Grimes Graves.

It is interesting to note that these ancient flint workings, in which we find the best examples of transitional forms, have both of them some suggestion of remote age. The pits from which the flint was procured at Cissbury are covered by the ramparts of an ancient British camp and the ground near Grimes Graves has yielded Palaeolithic implements in situ in small rain-wash hollows close by—as seen near "Botany Bay." Palaeolithic man came into this area sometime after the uplift of East Anglia out of the Glacial Sea and was here through the period of denudation and formation of river terraces which ensued and the age of depression which followed. But Neolithic man belongs to the later part of that period of depression when the ends of some of the river gravels were again depressed below sea level and the valleys had scarcely sufficient fall for the rivers to flow freely to the sea. In the stagnant swamps and meres thus caused the Fen deposits grew, and in this time the Shippea man met his death mired in the watery peat of the then undrained fens.

Human bones have not been very often found in the Fen, and when they do occur it is not always easy to say whether they really belong to the age of the peat in which they are found or may not be the remains of someone mired in the bog or drowned in one of the later filled up ditches. That they have long been buried in the peat is often obvious from the colour and condition of the bone. By the kindness of our friends Mr and Mrs Luddington my wife and I received early information of the discovery of human bones in trenching on some of their property in the Fen close to Shippea Hill near Littleport and we were able to examine the section and get some of the bones out of the peat ourselves (Fig. 6). A deposit of about 4' 6" of peat with small thin lenticular beds of shell marl here rested on lead colored alluvial clay. In the base of the peat about four inches above the Buttery Clay a human skeleton was found bunched up and crowded into a small space, less than two feet square, as if the body had settled down vertically.

Fig. 6. Diagram Section across Shippea Hill.

Some of the bones were broken and much decayed, while others, when carefully extracted, dried and helped out with a little thin glue, became very sound and showed by the surface markings that they had suffered only from the moisture and not from any wear in transport.

The most interesting point about them is the protuberant brow, which, when first seen on the detached frontal bone, before the skull had been restored, suggested comparison with that of the Neanderthal man.

Much greater importance was attached to that character when the Neanderthal skull was found.

When I announced the discovery of the Shippea man the point on which I laid most stress was that, notwithstanding his protuberant brow, he could not possibly be of the age of the deposits to which the Neanderthal man was referred. I stated "my own conviction that the peat in which the Shippea man was found cannot be older than Neolithic times and may be much newer" and, believing that similar prominent brow ridges are not uncommon to-day, I suggested that he might be even as late as the time of the monks of Ely who had a Retreat on Shippea Hill.

The best authorities who have seen the skull since it has been restored by Mr C. E. Gray, our skilful First Attendant in the Sedgwick Museum, refer it to the Bronze Age which falls well within the limits which I assigned.

This skull is unique among the few that I have obtained from the Fens. Dr Duckworth has described[9] most of these, and I subjoin a description of the Shippea man by Professor Alexander Macalister.

"The calvaria is large, dark coloured and much broken. The base, facial bones and part of the left brow ridge and glabella are gone. The sutures are coarsely toothed and visible superficially although ankylosis has set in in the inner face. The bone is fairly thick (8·10 mm.), and on the inner face the pacchionian pits are large and deep on each side of the middle line especially in the bregmatic part of the frontal and the post-bregmatic part of the parietals. The superior longitudinal groove is deep but narrow, and, as far as the broken condition allows definite tracing, the cerebral convolution impressions are of the typical pattern.

Fig. 7.

"The striking feature is the prominent brow ridge due to the large frontal sinus. The glabella was probably prominent and the margins on each side are large and rough and extend outwards to the supraorbital notches. The outer part of the supraorbital margin and the processus jugalis are thick, coarse and prominent (Fig. 7).

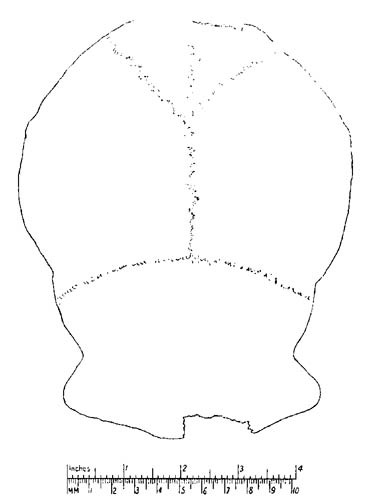

"In norma verticalis the skull is ovoid-pentagonoid euryme-topic with conspicuous rounded parietal eminences, slight flattening at the obelion and a convex planum interparietale below it (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

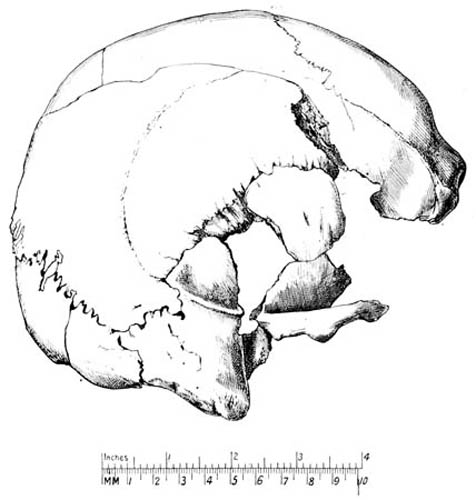

"In norma lateralis the brow ridges are conspicuous; above them is the sulcus transversus from which the frontal ascends with a fairly uniform curve to the bregma. The frontal sagittal arc above the ophryon measures 112 mm. and its chord 116. Behind the bregma the parietals along the front half of the sagittal suture have a fairly flat outline to the medio-parietal region, behind which the flattened obelion is continued downwards with a uniform slope to the middle of the planum interparietale whence it probably descended by a much steeper curve to the inion, which is lost. The parietal sagittal arc, including the region where there was probably a supra-lambdoid ossicle, was about 140 mm. and its chord 121 but the curve is not uniform.

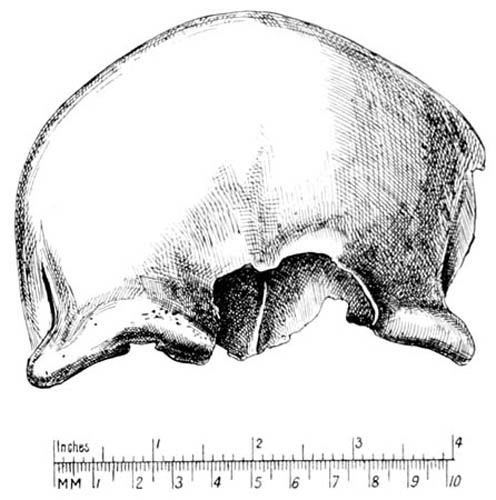

"In norma occipitalis the sagittal suture appears at the summit of a ridge whose parietal sides slope outwards forming with each other an angle of 138°, as far as the parietal eminences. From these the sides drop vertically down to the large mastoid processes. The intermastoid width at the tips of the processes is 115, but at the supramastoid crest is 148 (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

"In norma frontalis the conspicuous feature is the brow ridge. This gives a kind of superficial suggestion of a Neanderthaloid shape, but the broad and well arched frontal dispels the illusory likeness. The jugal processes jut out giving a biorbital breadth of 115 mm. while the least frontal width is 97 and the bistephanic expands to 125. There is a slight median ridge on the frontal ascending from the ophryon, at first narrow but expanding at the bregma to 50 mm. The surface of this elevated area is a little smoother than that of the bone on each side of it.

"The other long bones are mostly broken at their extremities. The femora are strong and platymeric. The postero-lateral rounded edge, which bears on its hinder face the insertion of the gluteus maximus, taken in connexion with the projection of the thin medial margin of the shaft below the tuberculum colli inferior causes the upper end of the shaft to appear flattened. The index of platymeria is ·55. The femoral length cannot have been less than 471 mm. The man was probably of middle stature, not a giant as was the Gristhorpe man. The tibiæ are also broken at their ends, they are eurycnemic (index ·80) with sharp sinuous shin and flat back, the length may have been between 335 and 340 mm. The humeri are also bones with strong muscular crests, and the ulnæ are smooth and long. The fibula was channelled. There is nothing in the bone-features which is inconsistent with the reference of the skull to the Brachycephalic Bronze Age race.

Fig. 10.

"In the following Table are recorded the measurements of the different regions. The two crania which I have selected to compare with it are (1) a Round-barrow skull from near Stonehenge (No. 179 in our Collection) and (2) the Gristhorpe skull, to both of which it bears a very strong family likeness.

| Shippea Hill |

Stonehenge (No. 179) |

Gristhorpe |

|

| Maximal length | 194 | 185 | 192 |

| Maximal breadth | 153 | 153 | 156 |

| Auricular height | 135 | 132 | 133 |

| Biorbital width | 115 | 112 | 117 |

| Bistephanic width | 128 | 132 | 133 |

| Least frontal width | 97 | 103 | 106 |

| Biasterial | 120 | 127 | 125 |

| Auriculo-glabellar radius | 116 | 113 | 114 |

| Auriculo-ophryal radius | 113 | 111 | 105 |

| Auriculo-metopic radius | 134 | 127 | 124 |

| Auriculo-bregmatic radius | 137 | 132 | 134 |

| Auriculo-lambdoid radius | 104 | 102 | 115 |

| Length and breadth index | 78·87 | 82·7 | 81·25 |

"The resemblance to the two Round-barrow skulls of the Bronze Age is too great to be accidental, so we may regard this as a representative of that race, possibly at an earlier stage than the typical form of which the two selected specimens are examples (Fig. 10).

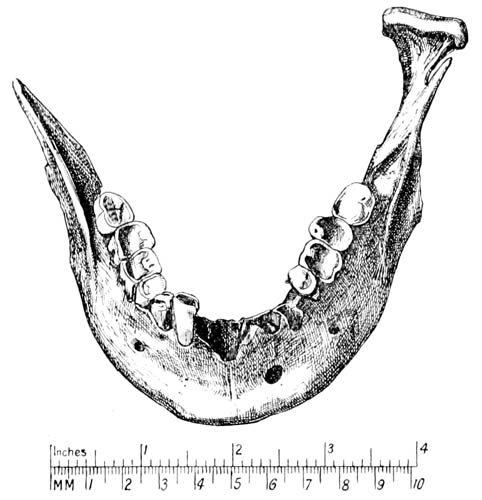

"The mandible also resembles that of the Gristhorpe skull in general shape of angle and prominence of chin.

"The measurements are as appended:

Shippea Stonehenge Hill (No. 179) Gristhorpe Condylo mental length 131 — 130 Gonio mental length 100 — 99 Bigoniac 115 — 116 Bicondylar 139 — 141 Chin height 32 — 33"

Cambridge:

PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A.

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Footnotes

Transcriber's Note:

Minor typographical errors have been corrected without note.

Irregularities and inconsistencies in the text have been retained as printed.