How the merry breezes blow!

Blue skies, blue eyes,

Baby, bees, and butterflies,

Daisies growing everywhere,

Breath of roses in the air!

Dollie Dimple, swing away,

Baby darling, at your play.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Nursery, July 1881, Vol. XXX, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Nursery, July 1881, Vol. XXX

A Monthly Magazine for Youngest Readers

Author: Various

Release Date: February 22, 2013 [EBook #42156]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NURSERY, JULY 1881, VOL. XXX ***

Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Music

transcribed by Veronika Redfern.

| PAGE | |

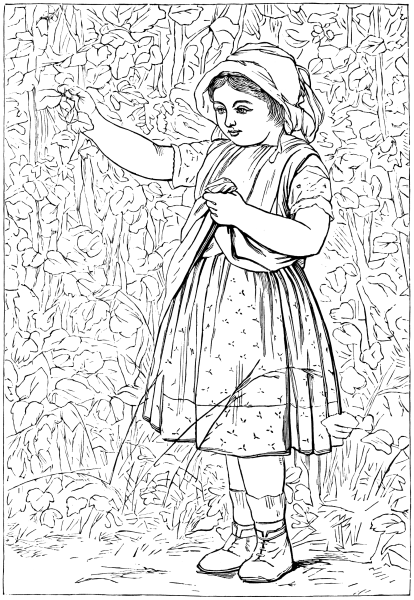

| Hide and Seek | 193 |

| Flowers for Mamma | 195 |

| Outwitted | 197 |

| Zip Coon | 199 |

| The Fuss in the Poultry-Yard | 201 |

| Our Charley | 206 |

| Drawing-Lesson | 209 |

| More about "Parley-voo" | 210 |

| The old Pump | 214 |

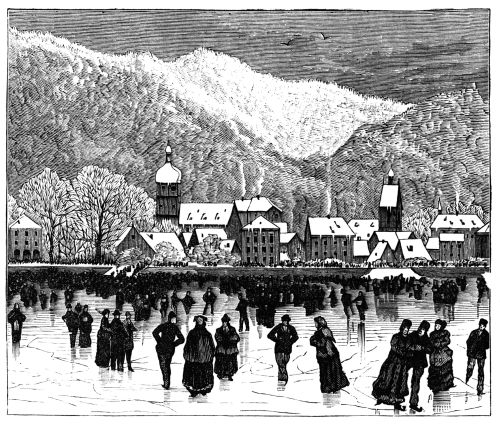

| Winter on Lake Constance | 215 |

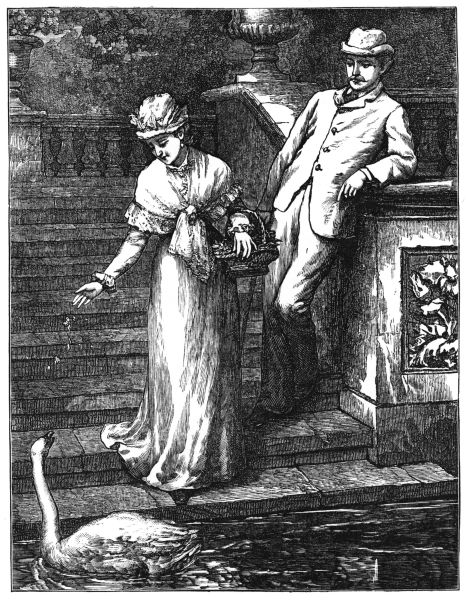

| Swan-upping | 216 |

| The Man in the Moon | 219 |

| The Boy and the Cat | 220 |

IN VERSE. |

|

| Hammock Song | 196 |

| Rosie and the Pigs | 198 |

| What's up | 203 |

| Minding Mother | 204 |

| Peet-Weet | 207 |

| Baby's Ride | 212 |

| Baby-Brother | 222 |

| Under Green Leaves (with music) | 224 |

HIDE AND SEEK.

HIDE AND SEEK.

"No answer. Hark! I hear a noise up in that tree. Can that be Charley? Oh, no! It is a bird. 'Little bird, have you seen a small boy with curly hair? Tell me where to look for him.'

"The bird will not tell me. I must ask the squirrel. 'Squirrel, have you seen a boy with rosy cheeks?' Away goes the squirrel into a hole without saying a word.

"Ah! there goes a butterfly. I will ask him. 'Butterfly, have you seen a boy, with black eyes, rosy cheeks, and curly hair?' The butterfly lights on a bush. Now he flies again. Now he is off without making any reply.

"Dear me! what shall I do? Is my little boy lost in the woods? Must I go home without him? Oh, how can I live without my boy!"

Out pops a laughing face from the bushes.

"Here I am, mamma!" says Charley. "Don't cry. Here I am close by you."

"Why, so you are. Come out here, you little rogue, and tell me where you have been all this time."

"I have been right behind this tree, and I heard every word you said," says Charley.

"What a joke that was! Why, Charley, you must have kept still for as much as three minutes. I never knew you to do that before."

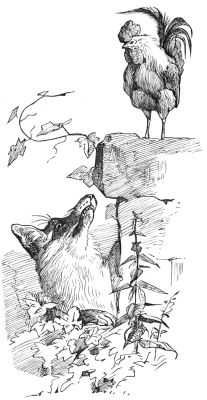

Suddenly, however, the rooster saw him and flew, in a great fright, to the top of the wall.

The fox could not get him there, and he knew it: so he came out from his hiding-place, and addressed the rooster thus: "Dear me!" he cried, "how handsomely you are dressed! I came to invite your magnificence to a grand christening feast. The duck and the goose have promised to come, and the turkey, though slightly ill, will try to come also.

"You see that only those of rank are bidden to this feast, and we beg you to adorn it with your splendid talent for music. We are to have the most delicate little cock-chafers served up on toast, a delicious salad of earthworms,[198] in fact all manner of good things. Will you not return then with me to my house?"

"Oh ho!" said the rooster, "how kind you are! What fine stories you tell! Still I think it safest to decline your kind invitation. I am sorry not to go to that splendid feast; but I cannot leave my wife, for she is sitting on seven new eggs. Good-by! I hope you will relish those earthworms. Don't come too near me, or I will crow for the dogs. Good-by!"

Zip had a long, low body, covered with stiff yellowish hair. His nose was pointed, and his eyes were bright as buttons. His paws were regular little hands, and he used them just like hands.

He was very tame. He would climb up on Isabella's chair, and scramble to her shoulder. Then he would comb her hair with his fingers, pick at her ear-rings, and feel of her collar and pin and buttons.

Isabella's mother was quite ill, but sometimes was able to sit in her chair and eat her dinner from a tray on her lap. She liked to have Zip in her room; but, if left alone with[200] her, Zip would jump up in the chair behind her, and try to crowd her off. He would reach around, too, under her arm, and steal things from her tray.

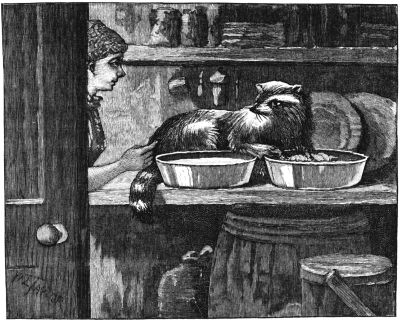

Once the cook in the kitchen heard a brisk rattling of tin pans in the pantry. She opened the door, and there, on a shelf, was Zip. There were two pans standing side by side. One had Indian-meal in it, and the other nice sweet milk. In front of the pans stood Zippy.

He had scooped the meal from one pan into the milk in the other pan, and was stirring up a pudding with all his might. He looked over his shoulder when he heard the cook coming up behind him, and worked away all the faster, as if to get the pudding done before he was snatched up, and put out of the pantry.

Zip was very neat and clean. He loved to have a bowl of water and piece of soap set down for his own use. He would take the soap in his hands, dip it into the water, and rub it between his palms; then he would reach all around his body, and wash himself. It was very funny to see him reach way around, and wash his back.

One day, Isabella, not feeling well, was lying on her bed. Zippy was playing around her in his usual way. Pretty soon he ran under the bed, and was busy a long while reaching up, and pulling and picking at the slats over his head. By and by he crawled out; and what do you think he had between his teeth? A pretty little red coral ear-ring that Isabella had lost several weeks before. Zip's bright eyes had spied it as he was playing around under the bed. So you see Zip Coon did some good that time.

When Zip grew older, he became so cross and snappish, that he had to be chained up in the woodshed in front of his little house. On the door of his house was printed in red letters, "Zip Coon: he bites."

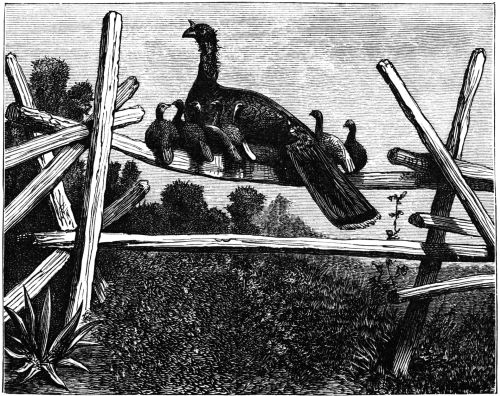

But if we could look round a corner, and take a view of[202] the other side of the barnyard, we should see something quite exciting.

The trouble was made by three hens of foreign breed. They felt so proud because they had big tufts on their heads, that they looked down on the native barn-yard fowls. One old white hen they never cease to pick upon.

Now, the old white hen, although plain, was very smart. If there was a good fat worm to be found anywhere, she was sure to scratch it up. This was what caused the fuss.

Old Whitey scratched up a worm. Three tufted hens at once tried to take it away from her. There was a chase all around the barnyard. Old Whitey, with the worm in her mouth, kept the lead.

Out she dashed through an opening in the fence. Down she went, down the hill back of the barn. The three tufted hens, like three highwaymen, were close upon her.

Well, what was the end of it? They didn't get the worm; I can tell you that. But there was a fight, and I can't say that poor Whitey got off without being badly pecked.

Why does Miss Prim; So stylish and slim, Hold up her head so high? What does she see? A bird in the tree? Or is it a star in the sky? |

|

|

And here is young Jane

In bonnet so plain: And why is she looking up too? Do they seek at high noon For the man in the moon? Now, really, I wish that I knew?

V. W. |

What I am going to tell happened one spring day. It was warm and beautiful out, and the doors and windows of the house were left open for the fresh air to circulate freely. Charley was turned into the front-yard to nibble the green grass for a while. It must have seemed good to him after eating straw and hay all winter.

He ate and ate until he had eaten all he wanted, and probably felt as boys and girls sometimes do when they have room for nothing more, except pie, or pudding, or whatever the dessert may be.

In the house dinner was over, and the table was waiting for Katy to come from the kitchen to clear it off. The family had gone into the sitting-room, and were busy talking about a ramble in the woods for flowers, which had been promised us children for that afternoon.

All at once we heard the tramp of heavy feet passing through the hall into the dining-room. "Run, Willy," said mother, "and see what is making such a noise."

Willy ran out, and came back laughing so he could hardly speak. "It's old Charley," said he. "He's in the dining-room." We all rushed to the door, and, sure enough, there stood Charley by the table, eating what he could find on the platters and children's plates.

Oh, how we all laughed to see him standing there, as sober as if it were his own stall and manger! We were[207] willing that Charley should have what we had left; but it seemed hardly right that a horse should be in the house; besides, we feared that he might push the dishes off.

So Willy took him by the mane, and led him out of the house. He went off chewing what he had in his mouth, and nodding his head, as much as to say, "That pie-crust and salt are pretty good. If you please, I'll call again."

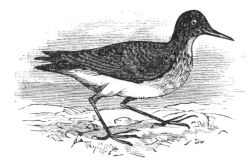

[A] Peet-weet is the common name of the spotted Sandpiper, derived from its note.

DRAWING-LESSON.

DRAWING-LESSON.

"Where's Parley-voo?" asked aunt Tib one afternoon. "I haven't seen him for a long time."

"Where can he be?" said mamma, looking concerned.

"Where can he be?" echoed the French nurse, throwing down her sewing, and going in search of him. "Where can he be? Le méchant!" (She meant "The naughty little boy.") Then she ran down the walk, calling out, "Parley-voo, Parley-voo, Parley-voo!" But not a sound came back.

She went down the lane to the house of the tailoress, where Parley-voo had sometimes been known to go. "Have you seen our little boy to-day?" she asked anxiously of the tailoress, who sat at the window, making a vest.

The tailoress looked up over her glasses, and laughed. "Why, yes: he's here," said she; "and I don't know what his mother will say when she sees him."

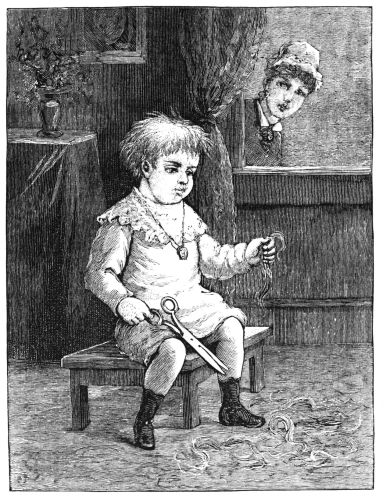

The nurse went up to the window, and looked in. There sat Parley-voo on a little wooden cricket, and ever so much of his bright, pretty hair—as much as he could get at—lay on the floor beside him.

When Parley-voo saw the nurse, he ran into a corner, and hid his face. The poor nurse was so amazed, that she could hardly speak. How came the child in such a plight?

The tailoress told the story as follows. She had gone out to pick some peas in the garden, leaving her husband, a blind man, in the room with Parley-voo. He heard the little boy about the room, and, fearing that he might be in some mischief, told him that he "must not meddle."

But pretty soon the blind man heard the sound of shears going across the table. Parley-voo was certainly doing something with the shears.

"Little boy, you must not meddle," said the blind man again. The noise stopped. "Ah! the boy does not dare to disobey me," thought the blind man.

All of a sudden the noise began again; but it was a very different noise. It was not on the table. The shears went together every little while with a sharp click.

The blind man felt very uneasy. "I do wish," he thought,[212] "my wife would come in and see what the little chap is up to."

To console himself, the blind man opened his snuff-box and took a pinch of snuff. What do you think the little chap did? He slyly put in his finger and thumb, and took a pinch too. And then how he did sneeze!

The tailoress heard him sneeze, and came in. She saw at once what had been going on. Parley-voo had been cutting his hair.

"Oh, my!" exclaimed mamma, when the nurse brought him home.

"Dear, dear!" cried aunt Tib, "what a looking child!"

Then the bonne told where she found him, and they looked at his hair, and talked so much about it, that Parley-voo wished he could sink through the floor out of sight. And he thought to himself that he would never again touch any thing he had been told not to.

The nurse took him up to the nursery, and dressed him all fresh and nice before his father came home. But the pretty yellow hair was two or three months growing out.

This is the pump that stands in the field near our house. The well is very deep, and the water is pure and cold. There is a trough at which the cows and horses often come to drink.

Bridget goes to the pump two or three times a day to get a pail of water. It is quite a task to bring it so far. But Bridget's arms are quite strong. She takes all the care of the hens and cows and pigs.

People came from far and near to see it and to skate on it. The lake was black with skaters who were gliding over its surface.

Men, women, and children alike shared the fun. There had not been such skating before for fifty years, and it is no wonder that they made the most of it while it lasted.

In January a warm wind blew for two days: the huge[216] masses of snow melted, and the little brooks were once more set running down the mountain-sides. But winter was soon back again with redoubled severity, bringing fresh snow and severer frost, and thus keeping the lake frozen.

On Candlemas Day (the second day of February) there was a grand festival on the ice. The peasants came from far and near. There were thousands of them there. In the evening there was a grand illumination, and after that there were fireworks, and then a dance on the ice.

In summer the water of Lake Constance is of a dark green color. The River Rhine enters it at the western end, and flows out at the eastern end. The lake is about forty-four miles long and nine miles wide.

The view of the frozen lake from the mountains is said to have been very fine. As you looked down on its smooth glittering surface, the skaters moving over it appeared like mere specks, while the houses in the village were like doll-houses.

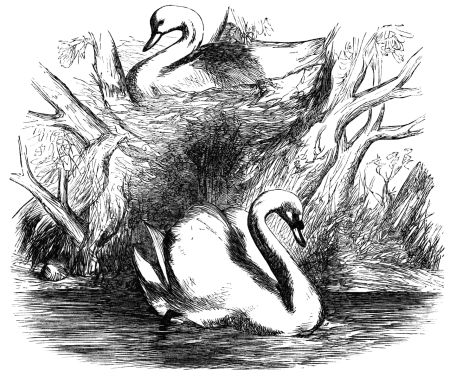

Some miles from London, on one of the most beautiful parts of the River Thames, a great number of swans are kept, which are owned by the Dyers' and Vintners' Companies.

The owners value them so highly, and take such care of them, that they have about as nice a time as any birds could wish to have. I fancy that these Thames swans hold their[217] heads higher, and feel prouder, than any other swans in England.

They build their nests in the osier-beds, by the side of the river, but out of the reach of the water. These nests are compact, handsome structures, formed of osiers, or reeds.

Every pair of swans has its own walk, or district, within[218] which no other swans are permitted to build. Every pair has a keeper appointed to take the entire charge of them.

The keeper receives a small sum for every cygnet that is reared; and it is his duty to see that the nest is not disturbed. Sometimes he helps these lordly birds by building the foundation of the nest for them.

Once a year, in August, the swans are counted and marked. This is called "swan-upping," and a good time it used to be. In gayly decorated barges, with flags flying, and music playing, the city authorities came up the river to take up the swans and mark them.

The "upping" began on the first Monday after St. Peter's Day. But, before the swans could be taken up, they had to be caught. This was no easy matter; for the swans are strong; and often they would lead the uppers a hard chase among the crooks of the river.

The mark of the Vintners' Company is two nicks: hence came the well-known sign on so many inns in England, "The Swan with Two Necks," a corruption from "two nicks."

These "Thames swans" are very beautiful birds, and well worth a trip up the river to see: so I hope, that, if ever the little readers of "The Nursery" take a trip to England, they will visit Hurley in Bucks, and there they will find "The Swans with Two Nicks."

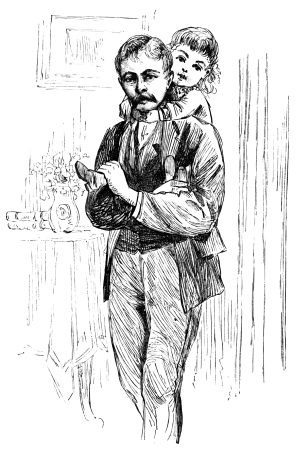

Then I get into the rocking-chair, take Helen on one knee and Lewis on the other, and as they lean on my breast, with their eyes shut, I rock and talk to them thus:—

"Here we are up in the sky on the moon. Oh, how high we are! Below us see the clouds blown about like feathers. Here we are safe and sound in the moon. Look down, and see the trees on the earth. There's where the birds are going to bed. Do you see that streak that looks like a silver ribbon? That is a river flowing to the sea. Now we are over the ocean. You can see our moonlight like great plates of silver all over it. See! there comes a ship all white. It looks as if it had its nightdress on.

"Here we are over a town. How beautiful the streets look with gas-lamps burning! And see all the pretty things in the shop-windows. I know what Helen is looking at.[220] It is the big doll dressed in silk and satin. I know what Lewis is looking at. He is looking at the ginger-bread.

"Oh! now we are just over a little white house. I can see through the window a man with two children in his lap. Oh, dear! he's going to do something dreadful with them."

"What's that?" asks Helen. "Put them to bed," I say. But Lewis says nothing. He is fast asleep.

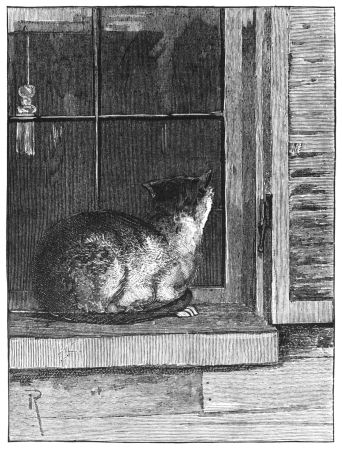

He is looking out of the window. He sees a cat on the sill outside. It is an old strange cat.

The little boy is fond of kittens; but he does not like cats. He is not polite to the strange cat.

"What do you want here?" he says. "Why do you stare at me so? Do you want to eat me? I'm not a mouse. Go away!"

The cat answers with one word, "Mew!"

"What do you say?" asks the boy. "Are you cold? Do you want to come in? Do you want some milk?"

And all that the cat says is, "Mew!"

"Go away!" says the boy again. "My mother does not like strange cats. I do not like strange cats. If you are hungry, go and catch a rat. You can't come in here."

The cat does not budge an inch. But still she answers with a pitiful "Mew!"

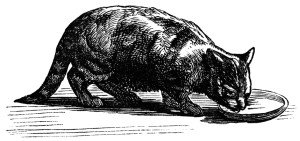

Cats cannot talk; but they can think. This cat looks in at the window and sees the boy. This is what she thinks.

"That boy looks like a boy that I knew when I was a kitten. I was a pet then. Now I am a cat without any home. Nobody cares for me. I go from house to house;[222] but nobody takes me in. I wonder if I can't make that little boy take pity on me. I will try.

"Ah! he treats me like everybody else. He tells me to go away. Pretty soon he will say, 'Scat!' and throw water on me. No: he will not do that. He is so much like the little boy who used to pet me when I was a kitten, that I will not run away from him. I will beg to be let in."

So the cat sat still and said, "Mew!"

And the cat did not make a mistake. The little boy did take pity on her at last. He toddled off to his mother as fast as his legs would carry him, and got a pan of milk, which he set on the floor.

His mother opened the window for him, and the strange cat came in. How eagerly she lapped up the milk! She was really a very nice cat. The little boy soon began to make a pet of her.

And the cat was happy, and the boy was happy; and I don't know which was the happier of the two.

The original text for the July issue had a table of contents that spanned six issues. This was divided amongst those issues.

Additionally, only the July issue had a title page. This page was copied for the remaining five issues. Each issue had the number added on the title page after the Volume number.

End of Project Gutenberg's The Nursery, July 1881, Vol. XXX, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NURSERY, JULY 1881, VOL. XXX ***

***** This file should be named 42156-h.htm or 42156-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/2/1/5/42156/

Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Music

transcribed by Veronika Redfern.

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation information page at www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at 809

North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email

contact links and up to date contact information can be found at the

Foundation's web site and official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For forty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.