Finally they found better going along a narrow ledge

Project Gutenberg's Girl Scouts in the Rockies, by Lillian Elizabeth Roy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Girl Scouts in the Rockies Author: Lillian Elizabeth Roy Release Date: November 15, 2011 [EBook #38018] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GIRL SCOUTS IN THE ROCKIES *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Finally they found better going along a narrow ledge

CONTENTS

“Girls, this is our third Summer as the Dandelion Troop of Girl Scouts,—do you realize that fact?” commented Mrs. Vernon, generally called “Verny” by the girls, or “Captain” by her friends.

“That first Summer in camp seems like mere child’s play now, Verny,” returned Juliet Lee, known as “Julie” or just “Jule” by her intimates.

“That really wasn’t camping, at all,—what with all the cooked food our families were bringing weekly to us, and the other housekeeping equipment they brought that day in the ‘furniture shower,’” Joan Allison added, giggling as she remembered the incident.

“But last Summer in the Adirondacks was real camping!” declared Ruth Bentley, nodding her head emphatically.

“Yes. Still it wasn’t anything like this year’s camping experience promises to be,—in the Rocky Mountains,” replied Mrs. Vernon. “Mr. Gilroy furnished the tents and cots and other heavy camping things last summer, but this year we will have to do without such luxuries.”

“We don’t care what we have to do without, Verny, because we are so thankful to be here at all!” exclaimed Anne Bailey, who was one of the five additional scout members admitted to the circle of the four founders of Dandelion Troop the preceding summer.

“I’m so sorry the other girls can’t be with us this trip,” remarked Julie, who was Scout Leader of the troop.

“It’s a shame that Amy’s mother treats her as if she were a babe. Why, this sort of trip is exactly what the girl needs to help her get rid of her nerves,” said Joan.

“Yes; didn’t every one say how well she was after last summer’s camp in the Adirondacks?” added Ruth Bentley.

“Poor Amy, she’ll have to stay home now, and hear her mother worry about her all summer,” sighed Betty Lee, Julie’s sister.

“Well, I am not wasting sympathy on Amy, when dear old Hester needs all of it. The way that girl pitched in and helped earn the family bread when her father died last winter, is courageous, say I!” declared Julie.

“We all think that, Julie. And not a word of regret out of her when she found we were coming away, with Gilly, to the Rockies,” added Joan.

“Dear old pal! We must be sure to write her regularly, and send her souvenirs from our different stopping-places,” said Mrs. Vernon, with tears glistening in her eyes for Hester’s sacrifice.

“If Julie hadn’t been my sister, I’m sure Mrs. Blake would have frightened May into keeping me home,” announced Betty. “When she told sister May of all the terrible things that might happen to us in the Rockies, Julie just sat and laughed aloud. Mrs. Blake was real angry at that, and said, ‘Well, May, if your mother was living she’d never allow her dear little girls to risk their lives on such a trip.’”

Julie smiled and added, “I told Mrs. Blake, then and there, that mother would be delighted to give us the opportunity, and so would any sensible mother if she knew what such a trip meant! Mrs. Blake jumped up then, and said, I’m sure I’m as sensible as any one, but I wouldn’t think of letting Judith and Edith take this trip.’”

“I guess it pays to be as healthy as I am,” laughed Anne Bailey, who was nicknamed the “heavyweight scout,” “’cause no one said I was too nervous to come, or too delicate to stand this outing.”

The other scouts laughed approvingly at Anne’s rosy cheeks and abundant fine health.

The foregoing conversation between Mrs. Vernon and five girl scouts took place on a train that had left Chicago, and Mr. Vernon, the day before. He had had personal business to attend to at that city, and so stopped over for a few days, promising to join the Dandelion Troop at Denver in good time to start on the Rocky Mountain trip.

“It’s perfectly lovely, Verny, to think Uncle is to be one of our party this summer,” remarked Joan. “He and Mr. Gilroy seem to get on so wonderfully, don’t they?”

“Yes, and Mr. Gilroy’s knowledge of camping in the Rockies, combined with Uncle’s being with us, lightens much of the responsibility I felt for taking you all on this outing,” answered Mrs. Vernon.

“It will seem ages for us to kill time about Denver when we’re so anxious to get away to the mountains,” said Julie.

“But there’s plenty to do in that marvelous city; and lots of short trips to take that will prove very interesting,” returned the Captain.

“Besides, we will have to get a number of items to add to our outfits,” suggested Ruth.

“That reminds me, girls; the paper Uncle gave me as he was about to leave the train is a memo Mr. Gilroy sent, about what to take with us for this jaunt. Shall I read it to you now?” asked Mrs. Vernon.

“Oh yes, do!” chorused the girlish voices; so Mrs. Vernon opened the page which had been torn from a letter addressed to Mr. Vernon by Mr. Gilroy. Then she began reading:

“About taking baggage and outfit for this trip in the Rockies, let me give you all a bit of advice. Remember this important point when considering your wardrobe, etc.,—that we will be on the move most of the time, and so every one must learn how to do without things. We must travel as the guides and trappers do—very ‘light.’ To know when you are ‘traveling light’ follow this rule:

“First, make a pyramid of everything you think you must take for use during the summer, excluding the camp outfit, which my man will look out for at Denver.

“Next, inventory the items you have in the heap. Study the list earnestly and cross out anything that is not an actual necessity. Take the articles eliminated from the heap, throw them behind your back, and pile up the items that are left.

“Then, list the remainder in the new pyramid, and go over this most carefully. Cast out everything that you have the least doubt about there being an imperative need of. Toss such items behind you, and then gather the much smaller pyramid together again.

“Now, forget all your past and present needs, all that civilized life claims you should use for wear, or camp, or sleep, and remove everything from the pyramid excepting such articles as you believe you would have to have to secure a living on a desert island. If you have done this problem well, you ought to have a list on hand, after the third elimination, about as follows:

“A felt hat with brim to shed the rain and to shade your eyes from the sun; a good all-wool sweater; winter-weight woolen undergarments that will not chill you when they are dripping with water that is sweated out from within, or soaked through from without; two or three large handkerchiefs, one of silk to use for the head, neck, or other parts of the body in case of need; three pairs of heather stockings,—one pair for day use, one pair to wear at night when it is cold, and the third pair to keep for extra need; high boots—one pair to wear and one to carry; two soft silk shirts—shirt-waists for you girls; a pure wool army blanket; one good rubber blanket; a toothbrush, hairbrush and comb, but no other toilet articles. Be sure to have the girl-scout axe, a steel-bladed sheath knife, a compass, the scout pocket-knife, fishing tackle, and a gun. (More about this gun hereafter, girls.)

“Now, being girl scouts, you will naturally wear the approved scout uniform. If possible, have this made up in good wiry serge that will shed dust and other things, along the trail. You will want a good strong riding-habit, and two pairs of silk rubber bloomers, the latter because of their thin texture and protection against moisture.

“Wear a complete outfit, and then pack your extras in the blanket; roll the bundle in the rubber blanket, and buckle two straps about the roll. Then slip this in the duffel-bag, and you are ready.

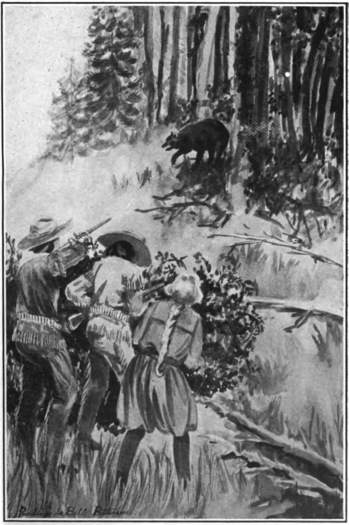

“About the gun. Don’t let your parents have a panic over the item mentioned. You girls had excellent target practice all last winter, so the fact of your carrying a rifle on this trip should not unduly excite any one. In the Rockies, a gun is as necessary as an axe or knife, and no one incurs a risk from carrying such a weapon unless he is careless. Being trained scouts, with experience back of you, you will be perfectly safe on this outing even though you do carry a rifle.

“An old Indian guide that I had some years ago, sent word that he would be happy to give us his time for the summer. So he will attend to all the camping needs,—utensils and canvas and horses, for the trip. I told him that we would have a party of girls with us this time, and he smiled when he said he would have to add needle and thread, cold cream, and such requisites to his list.”

“There, girls,” continued Mrs. Vernon, when she had concluded the reading of Mr. Gilroy’s instructions, “that is about all Gilly said about the outfit. But I knew we had conformed to most of these requirements already, so there is nothing more to do about it. When we go over the duffel-bags in Denver, Gilly may ask you scouts to throw out your manicure cases, or whimsical little things you deem an absolute necessity now, and several articles of wear that you think you must take, but, otherwise, we are ready to ‘travel light,’ as he says.”

“Shan’t we take our sleeping-bags, Verny?” asked Ruth.

“Gilly doesn’t say a word about them, so I don’t know whether he forgot them, or thought you left them home.”

“I wonder what sort of an outfit the guide will take?” remarked Julie.

“Aluminum-ware for cooking, and a cup, plate, and cutlery for each member of the party, Uncle Vernon said,” answered Mrs. Vernon.

Just before reaching Denver, Mrs. Vernon asked of the eager scouts, “Did you girls read the books I mentioned, to become familiar with this wonderful country through which we are going to travel?”

“I read all I could, and I’m sure the other girls did, too, because every time I asked for one of those books at the Public Library I was informed it was out. Upon investigation, I learned that one or the other of Dandelion Troop was reading it,” laughed Julie.

“Well, then, you learned that Colorado can boast of more than fifty mountain peaks, each three miles or more in height; a hundred or so nearly that high. And between these peaks can be found the wildest gorges, most fertile valleys and plains, that any state in the Union can boast.

“And because of these great peaks with their snow-capped summits, many of which are snowy all the year round, the flow of water from the melting snows furnishes the many scenic streams that give moisture to the plains; which in turn produce the best crops in the West.

“But the plains and valleys were not the attraction that first brought pioneers to Colorado. It was the gold and silver hidden in the mountains, and the upthrust of valuable ore from the sides of the canyons and gulches that was the magnet which caused mankind to swarm to this state. Thus, you see, it became generally populated, the mountainous, as well as the ranch sections.”

While riding westward from Chicago, the gradual rise of the country failed to impress the scouts, so they were all the more surprised when Mrs. Vernon exclaimed, “I verily believe I am the first to see Pike’s Peak, girls!”

“Oh, where? where?” chorused the scouts, crowding to the windows on the side of the train where the Captain sat.

“Away off there—where you see those banks of shadowy clouds! There is one cloud that stands out more distinctly than its companions—that’s it,” replied the Captain.

“Oh, Verny, that’s not a peak!” laughed Joan.

“Of course not! That’s only a darker cloud than usual,” added Julie, while the other scouts laughed at their Captain’s faulty eyesight.

Mrs. Vernon smiled, but kept her own counsel, and half an hour later the girls began to squint, then to doubt whether their hasty judgment had been correct, and finally to admit that their guide and teacher had been quite right! They saw the outline of a point that thrust itself above the hanging clouds which hid its sides in vapor, and the point that stood clearly defined against the sky was Pike’s Peak!

“But it isn’t snow-clad, and it isn’t a bit beautiful!” cried Ruth in disappointment.

“Still it is the first Rocky Mountain peak we have seen,” Betty Lee mildly added.

“Scouts, this is known as ‘The Pike’s Peak Region,’” read Julie from a guide-book.

“It ought to be called ‘Pike’s Bleak Region,’” grumbled Anne. “I never saw such yellow soil, with nothing but tufts of grass, dwarfed bushes, and twisted little trees growing everywhere.”

Mrs. Vernon laughed. “Anne, those tufts are buffalo grass, which makes such fine grazing for cattle; and your dwarfed bushes are the famous sage-brush, while the twisted trees are cottonwoods.”

“Oh, are they, really?” exclaimed Anne, now seeing these things with the same eyes but from a changed mental viewpoint.

“And notice, girls, how exhilarating the air is. Have you ever felt like this before—as if you could hike as far as the Continental Range without feeling weary?” questioned Mrs. Vernon.

When the train pulled in at Denver, Mr. Gilroy was waiting, and soon the scouts were taken to the hotel where he had engaged accommodations for the party.

“Don’t say a word until you have washed away some of that alkali dust and brushed your clothes. Then we will go out to view the village,” laughed he, when the girls plied him with questions.

But the scouts wasted no time needlessly over their toilets, and soon were down in the lobby again, eager for his plans.

“Now I’ll tell you what Uncle wired me from Chicago to-day,” began Mr. Gilroy, when all were together. “He’ll be there three days longer, so we’ve almost five days to kill before meeting him at this hotel.”

“I’ve engaged two good touring cars, and as soon as you approve of the plan, we will start out and see the city. To-morrow morning, early, we will motor to Colorado City and visit Hot Springs, and all the points of interest in that section. Then we can return by a different route and embrace dear old Uncle, who will be waiting for us. How about it?”

“How needless to ask!” exclaimed Mrs. Vernon, when the chorus of delight had somewhat subsided. Mr. Gilroy laughed.

“Come on, then! Bottle up the news, and stories of crime you experienced on the way West from New York, until we are en route to Colorado Springs. Then you can swamp me with it all,” said he.

So that day they visited the city of Denver, which gave the scouts much to see and talk about, for this wonderful city is an example of western thrift, ambition, and solid progress. Early the following morning, the touring party started in the two machines to spend a few days at Colorado Springs.

Without loss of time they drove to the famous Hot Springs, and then on through the picturesque estate of General Palmer, the founder of Colorado City. His place was copied after the well-known English castle Blenheim, and Julie was deeply impressed with the architecture of the building.

“Girls, to-morrow morning I want you to see the sun rise from the vantage point of Pike’s Peak, so we won’t climb that to-day. But we will go to Manitou, where the setting sun casts long-fingered shadows into the ravines, turning everything to fairy colors,” said Mr. Gilroy.

The scouts were awed into silence at the grandeur of the scenery they beheld, and Mr. Gilroy said, “The Ute Indians used to come to the Manitou Waters for healing, you know. To-morrow, on your way down from the Peak, we will stop at the Ute Pass. But I want you to see the marvelous feat of engineering in this modern day that has made an auto drive to the top of Pike’s Peak a possibility.”

So very early the next morning the scouts were called, and after a hurried breakfast started out in the cars for the Peak. Having driven over the fine auto road, recently completed, to the top of the Peak, they got out to watch the sunrise. This was truly a sight worth working for. From the Peak they could see over an expanse of sixty thousand square miles of country, and when the rays of the sun began to touch up with silver places here and there on this vast stretch, the scene was most impressive.

After leaving Pike’s Peak, Mr. Gilroy told the chauffeur to drive to the Ute Pass. That same day the girls visited the scenic marvels of the Garden of the Gods, the Cave of the Winds, Crystal Park, and other places.

They dined at the “Hidden Inn,” which was a copy of one of the Pueblo cliff-dwellings of the Mesa Verde. This Inn is built against a cliff, and is most picturesque with its Indian collection of trophies and decorations after the Pueblo people’s ideals.

They visited William’s Canyon and the Narrows, with its marvelous, painted cliffs of red, purple, and green; and went to Cheyenne Mountain and the canyon with its beautiful “Seven Falls.” Other places that Mr. Gilroy knew of but that were seldom listed in the guidebooks because they were out of the way, were visited and admired.

The last day of their visit to Colorado City, they all took the railroad train and went to Cripple Creek. The train wound over awesome heights, through rifts in cliffs, and past marvelously colored walls of rock, and so on to the place where more gold is mined than at any other spot in the world.

That night the scouts returned to the hotel at Colorado City well tired out, but satisfied with the touring they had accomplished in the time they had been in Colorado. In the morning they said good-bye to the gorgeous places in Pike’s Peak Park and headed again for Denver.

A splendid road led through Pike View, where the best views of Pike’s Peak can be had. Then they passed the queer formation of rock called “Monument Park,” and on still further they came to a palisade of white chalk, more than a thousand feet wide and one-fifth that in height, that was known as Casa Blanca.

Castle Rock was the next place of interest passed. It is said to be a thousand feet higher than Denver. Then several picturesque little towns were passed by, and at last Fort Logan was reached. As an army post this spot interested the scouts, but Mr. Gilroy gave them no time to watch the good-looking young officers, but sped them on past Loretto, Overland, and Denver Mile, finally into Denver again.

As they drove into the city, Mr. Gilroy explained why he had to hurry them. “You see, this is almost the middle of June, and I am supposed to return from the mountains in September with reports and specimens for the Government.

“Few people tarry in the Rockies after September, as the weather is unbearable for ‘Tenderfeet.’ So I have to get through my work before that time. Besides, Uncle Vernon is probably now awaiting us at the hotel, and he must not be left to wander about alone, or we may lose him.”

“When can we start for the Rockies, Gilly?” eagerly asked Julie, voicing the cry of all the other scouts.

“As soon as the Indian guide gives us the ‘high sign,’” replied Mr. Gilroy.

“About when will that be?” insisted Julie.

“Where is he now, Gilly?” added Ruth.

“I suppose he is in Denver waiting for us, but we can tell better after we see Uncle. I wired him to meet Tally there and complete any arrangements necessary to our immediate departure from Denver the day after we get back there.”

“I hope the guide’s name is easier to say than Yhon’s was last summer,” laughed Mrs. Vernon.

“The only name I have ever given him is ‘Tally’; but his correct name has about ninety-nine letters in it and when pronounced it sounds something like Talitheachee-choolee. Now can you blame me for quickly abbreviating it to Tally?” laughed Mr. Gilroy.

“I should say not!” laughed the girls, and Julie added, “Ho, Tally is great! It will constantly remind the scouts to keep their records up to date.”

Mr. Vernon was found at the hotel, comfortably ensconced in a huge leather chair. He pretended to be fast asleep, but was soon roused when the lively scouts fell upon him in their endeavor to tell him how glad they were to see him again.

“Spare me, I beg, and I will lead you to the nicest meal you ever tasted!” cried he, gasping.

Mr. Gilroy laughed and added, “You’d better, for it’s Tally, and wild Indian cooking hereafter, for three months!”

“That threat holds no fears for us brave scouts,” retorted the Corporal.

The girls followed quickly after Mr. Vernon, just the same, when he led the way to the dining-room. Here he had his party seated in a quiet corner, and then he reported to Mr. Gilroy all he had done since he landed in Denver in the morning.

“I have the surprise of the season for the scouts, I’m thinking,” began Mr. Vernon, smiling at the eager faces of the girls. “Have you formed any idea of how we are going to travel to the Divide?”

Even Mr. Gilroy wondered what his friend meant, for he had asked Tally to secure the best horses possible in Denver. And the scouts shook their heads to denote that they were at sea.

Mrs. Vernon laughed, “Not on foot, I trust!”

“No, indeed, my dear! Not with shoe leather costing what it does since the war,” retorted Mr. Vernon.

“We all give up,—tell us!” demanded his wife.

“First I have to tell you a tale,—for thereby hangs the rest of it.

“You see, Tally came here first thing this morning, and when I came in from my train, which was an hour late from Chicago, he greeted me. I hadn’t the faintest idea who he was until after the clerk gave me the wire from Gilly, then I saluted as reverently as he had done. Finally his story was told.

“It seems ‘Mee’sr Gil’loy’ told Tally to get outfit and all the horses, including two mules for pack-animals (although I never knew until Tally told me, that mules were horses). And poor Tally was in an awful way because he couldn’t find a horse worth shucks in the city of Denver. I fancy Tally knows horseflesh and would not be taken in by the dealers, eh, Gilly?” laughed Mr. Vernon.

Mr. Gilroy nodded his head approvingly, and muttered, “He is some guide, I tell you!” Then Mr. Vernon proceeded with his tale.

“Well, Tally got word the other day from his only brother, who runs a ranch up past Boulder somewhere, that a large ranch-wagon, ordered and paid for several months before, was not yet delivered. Would Tally go to the wagon-factory, and urge them to ship the vehicle, as the owner was in sore need of it this summer.

“Tally had gone to the factory all right, but the boss said it was impossible to make any deliveries to such out-of-the-way ranches, and the railroad refused freight for the present. Poor Tally wired his brother immediately, and got a disconcerting reply.

“He was authorized to take the wagon away from the manufacturer and send it on by any route possible. But the brother did not offer any suggestions for that route, nor did he provide means by which Tally could hitch the wagon up and send it on via its own transportation-power or expenses.

“Fortunately for Tally, and all of us, a horse-dealer had overheard the story and now joined us. ‘’Scuse me fer buttin’ in,’ he said, ‘but I got some hosses I want to ship to Boulder, and no decent driver fer ’em. Why cain’t we-all hitch up our troubles an’ drive ’em away. Let your Injun use my hosses as fur as Boulder, and no charge to him. He drives the animals to a stable I’ll mention and c’lect fer feed and expenses along the road, but no pay fer himself,—that’s squared on the use my beasts give you-all.’

“I ruminated. Here we were with Tally who had a wagon on his hands and no horses, and here was a dealer with four horses and no wagon. It sure seemed a fine hitch to make, so we all hitched together. So now we are all starting early in the morning via a prairie schooner to Boulder. How do you like it?”

A cry of mingled excitement and delight soon told him what the scouts thought of the plan, but Mr. Gilroy remarked, “But what am I to do about horses for the rest of the jaunt?”

“Oh, Tally says he can drive much better bargains with ranchers than in the city here, and the horses trained for mountain climbing by the ranchers are far superior to the hacks that have been used for years to trot about Denver City. So I decided to put it right up to Tally, and he agreed to supply splendid mounts for each one of us, or guide you free of charge all summer,” said Mr. Vernon.

Imagination had painted for the scouts a most thrilling ride in a prairie schooner, but they learned to their sorrow that the great ranch wagon built for travel over the heavy western roads and rough trails, was not quite as luxurious as a good automobile, going on splendid eastern state roads.

Ranch wagons are manufactured to withstand all sorts of ditches and obstructions in western roadways. They are constructed with great stiff springs, and the wheels have massive steel bands on still more massive rims. Into such a vehicle were packed the baggage and camping outfits that were meant to provide lodging and cooking for the party for the summer.

The four strong horses, which were to be delivered to a dealer in Boulder, pulled the wagon. Tally understood well how to drive a four-in-hand, but the going was not speedy, accustomed as the passengers were to traveling in fast automobiles.

Tally took the direct road to Boulder because it was the best route to the Rocky Mountain National Park, where Mr. Gilroy wished to examine certain moraines to find specimens he needed for his further work.

The wagon had rumbled along for several hours, and the tourists were now in the wonderful open country with the Rockies frowning down upon them from distant great heights, while the foothills into which they were heading were rising before them.

The road they were on ran along a bald crest of one of these foothills. Turning a bend in the trail, the scouts got their first glimpse of a genuine cattle-ranch. It was spread out in the valley between two mountains, like a table set for a picnic. The moving herd of cattle and the cowboys looked like dots on the tablecloth.

“Oh, look, every one! What are those tiny cowboys doing to the cattle?” called Julie, eagerly pointing to a mass of steers which were being gathered together at one corner of the range.

“I verily believe they are working the herd, Vernon! What say you,—shall we detour to give the scouts an idea of how they do it?” asked Mr. Gilroy.

Mr. Vernon took the field glasses and studied the mass for a few moments, then said, “To be sure, Gilroy! I’d like to watch the boys do it, too.”

“I have never witnessed the sight, although we all have heard about it,” added Mrs. Vernon. “It will be splendid to view such a scene as we travel along.”

Mr. Gilroy then turned to the driver. “Tally, when we reach the foot of this descent, take a trail that will lead us past that ranch where the cowboys are working cattle out of the herd.”

Tally nodded, and at the first turn he headed the horses towards the ranch a few miles away. When the tourists passed the rough ranch-house of logs, a number of young children ran out to watch the party of strangers, for visitors in that isolated spot were a curiosity.

The guide reined in his horses upon a knoll a short distance from the scene where the cattle were being rounded up. Spellbound, the scouts watched the great mass of the broad brown backs of the restless cattle, with their up-thrusting, shining horns constantly tossing, or impatient heads swaying from side to side. All around the vast herd were cowboys, picturesque in sombreros, and chaps with swinging ropes coiled ready to “cut out” a certain steer. Meanwhile, threading in and out of the concentrated mass, other horsemen were driving the cattle to the edge of the round-up.

“What do they intend doing with those they lasso, Gilly?” asked Joan.

“They will brand them with the ranch trade-mark, and then ship them to the large packing-houses.”

Mrs. Vernon managed to get several fine photographs of the interesting work, and then the Indian guide was told to drive on. Seeking for a way out to the main trail again, Tally ascended a very steep grade. Upon reaching the top, the scouts were given another fine view of the valley on the other side of the ridge. The scene looked like a Titanic checkerboard, with its squares accurately marked off by the various farms that dotted the land. But these “dots” really were extensive ranches, as the girls learned when they drove nearer and past them.

The day had been unusually hot for the month of June in that altitude, and towards late afternoon the sky became suddenly overcast.

“Going to get wet, Tally?” asked Mr. Gilroy, leaning out to glance up at the scudding clouds.

“Much wet,” came from the guide, but he kept his horses going at the same pace as before.

Thunderstorms in the Rockies do not creep up gradually. They just whoop up, and then empty the contents of their black clouds upon any place they select,—although the clouds are impartial, as a rule, in the selection of the spot.

Had the storm known that a crowd of tenderfeet were in the ranch wagon it could scarcely have produced a greater spectacle. It seemed as if all the elements combined to make impressive for the girls this, their first experience of a thunderstorm in the Rockies.

Before the sun had quite hidden behind an inky curtain, a blinding flash cleft the cloud and almost instantaneously a deafening crash followed. Even though every one expected the thunder, it startled them. In another minute’s time the downpour began. Wherever water could find entrance, there the howling wind drove in the slanting rain.

“Every one huddle in the middle of the wagon—keep away from the canvas sides!” Mr. Gilroy tried to shriek to those behind him.

Flashes with the accompanying cracks of thunder followed closely one upon the other, so that no one could be heard to speak, even though he yelled at the top of his lungs. The wind rose to a regular gale and the wagon rocked like a cockleshell on a choppy sea. The Indian sat unconcerned and kept driving as if in the most heavenly day, but the four horses reared their heads, snorting with fear and lunging at the bits in nervousness.

The storm passed away just as unexpectedly as it came, but it left the road, which was at best rough and full of holes, filled with water. The wagon wheels splashed through these wells, soaking everything within a radius of ten feet, and constantly shaking the scouts up thoroughly.

“I feel like a pillow, beaten up by a good housekeeper so that the feathers will fluff up,” said Julie.

“I’d rather feel like a pillow than to have my tongue chopped to bits,” cried Ruth, complainingly. “If I have any tongue left after this ride, I shall pickle it for safekeeping.”

“Can’t Featherweight sit still?” laughed Joan.

Mrs. Vernon placed an arm about Ruth’s shoulder to hold her steadier, just as an unusually deep hole shook up everybody and all the baggage in the wagon.

“There now! That’s the last bite left in my tongue! Three times I thought it was bitten through, but this last jolt twisted the roots so that I will have to have an artificial one hinged on at the first hospital we find,” wailed Ruth, showing the damaged organ that all might pity her.

Instead of giving sympathy, every one laughed, and Julie added, “At least your tongue is still in use, but my spine caved in at that last ravine we passed through, and now I have no backbone.”

Just as the scouts began laughing merrily at the two girls the front wagon wheel on the right side dropped into a hole, while the horses strained at the traces. The awful shock and jar given the passengers threw them against the canvas sides, and then together again in a heap.

The babel of shouting, screaming, laughing voices that instantly sounded from the helpless pile of humanity frightened the nervous horses. The leaders plunged madly, but the wheel stuck fast in the hole. Tally held a stiff rein, but the leaders contaminated the two rear horses, and all four plunged, reared, snorted, and pulled different ways at once. The inevitable was sure to happen!

“Jump, Tally, and grab the leaders! I’ll hold them in!” cried Mr. Gilroy, catching hold of the reins.

“Here, Gill, let me hold the reins while you help Tally!” shouted Mr. Vernon, instantly crawling over the front seat and taking the reins in hand.

So Mr. Gilroy sprang out after Tally, and made for one of the leaders while the guide caught hold of the other. But just as the Indian reached up to take the leather, the horse managed to work the bit between his teeth. At the same time, the lunging beasts yanked the wagon wheel up out of the hole, and feeling the release of what had balked their load, the horses began tearing along the road.

Tally dangled from the head of the first horse whose bit he had tried to work back into place. Mr. Vernon held firmly to the reins as he sat on the driver’s seat of the wagon. But Mr. Gilroy was left clear out of sight, standing in the middle of the muddy road, staring speechlessly after the disappearing vehicle. The scouts were tossed back and forth like tennis balls, but the tossing was not done as gracefully as in a game of tennis.

Fortunately for all concerned, the road soon ascended a steep grade, and a long one. The cumbersome wagon was too heavy to be flipped up that hill without the four horses becoming breathless. The leaders were the first to heave and slow down in their pace; then the two rear beasts panted and slowed, and finally all came to a dead stop. This gave Tally his opportunity to drop from his perilous clutch and glare at the horses.

“Outlaws!” hissed he at the animals, as if this ignominious western term was sufficient punishment to shame the horses.

“Poor Gilly! Have we lost him?” cried Betty, who had been shaken into speechlessness during the wild ride.

Mr. Vernon took the field glasses from his pocket and focussed them along the road he had so recently flown over in the bouncing wagon. Suddenly a wild laugh shook him, and he passed the glasses to his wife.

The Captain leveled them and took a good look, then laughing as heartily as her husband, she gave them to Julie and hurriedly adjusted the camera.

The Scout Leader took them and looked. “Oh, girls! You ought to see Gilly. He is trying to hurry up the long road, but he is constantly jumping the water holes and slipping in the mud. Here—every one take a squint at him.”

By the time Mr. Gilroy came up the long steep hill, every scout had had a good laugh at the appearance he made while climbing, and the Captain had taken several funny snapshots of him.

Upon reaching the wagon, Mr. Gilroy sighed, “Well, I am not sure which was worse—Tally’s ride or that walk!”

“Um—him walk, badder of all!” grinned the Indian.

The scouts rolled up the side curtains of the wagon that they could admire the view as they passed. And with every one feeling resigned to a mild shaking as compared to the last capers of the four horses, the journey was resumed.

Great overhanging boulders looked ready to roll down upon and crush such pigmies as these that crawled along the road under them. Then, here and there, swift, laughing streams leaped over the rocks to fall down many, many hundreds of feet into the gorges riven between the cliffs. The falling waters sprayed everything and made of the mist a veritable bridal-veil of shimmering, shining white.

“Tally, shall we reach Boulder to-night?” asked Mr. Gilroy, gazing at the fast-falling twilight.

“Late bimeby,” Tally said, shrugging his shoulders to express his uncertainty.

“Well, then, if we are going to be late, and as the way is not too smooth, I propose we pitch camp for the night. What say you?” suggested Mr. Gilroy, turning to hear the verdict of the scouts.

“Oh, that will be more fun than stopping at a hotel in Boulder!” exclaimed the Leader, the other girls agreeing with her.

“Very well, Gilly; let us find a suitable place for camp,” added the Captain.

“We need not pitch the tents, as you scouts can sleep in the wagon, and we three men will stretch out beside the campfire. Tally can pull in at the first good clearing we find along the way,” explained Mr. Gilroy.

“If we bunk in the wagon, we’ll have to stretch out in a row,” remarked Joan.

“We’ll look like a lot of dolls on the shelf of a toy-shop,” giggled Julie.

“I don’t want to sleep next to you, Julie—you’re such a kicker in your sleep,” complained Betty. Everybody laughed at the sisters, and Anne said:

“I don’t mind kicks, as I never feel them when I’m asleep.”

Tally had brought canned and prepared food for just such an emergency as an unexpected camp; so now the supper was quickly cooked and the travelers called to enjoy it.

Night falls swiftly in the mountains, and even though the day may have been warm, the nights in the Rockies are cold. A fire is always a comfort, so when supper was over the scouts sat around the fire, thoroughly enjoying its blaze.

The late afterglow in the sky seemed to hover over the camp as if reluctant to fade away and leave the scouts in the dark. The atmosphere seemed tinged with orchid tints, and a faint, almost imperceptible white chill pervaded the woods.

“Girls,” said Mr. Gilroy, “we have shelter, food and clothing enough, in this wonderful isolation of Nature—is there anything more that humans can really secure with all their struggling for supremacy? Is not this life in grand communion with Mother Nature better than the cliff-dwellers in great cities ever have?”

Mrs. Vernon agreed thoroughly with him and added, “Yes, and man can have, if he desires it, this sublime and satisfying life in the mountains, where every individual is supreme over all he surveys—as the Creator willed it to be.”

Tally finished clearing away the supper, and sat down to have a smoke. But Mr. Gilroy turned to him, and said, “Tally, we would like to hear one of your tribe’s legends, like those you used to tell me.”

“Oh, yes, Tally! please, please!” immediately came from the group of girls.

Tally offered no protest, but removed the pipe from his lips and asked, “You like Blackfeet tale?”

“Yes, indeed!” chorused those about the fire.

“My people, Blackfeet Tribe. Him hunt buffalo, elk, and moose. Him travel far, and fight big. Tally know tribe history, an’ Tally tell him.”

Then he began to relate, in his fascinating English, a tale that belonged to his people. The Dandelion Scouts would have liked to write the story down in their records as Tally gave it, but they had to be satisfied with such English as they knew.

“Long ago, when the First People lived on earth, there were no horses. The Blackfeet bred great dogs for hauling and packing. Some Indians used elk for that purpose, but the wild animals were not reliable, and generally broke away when they reached maturity.

“In one of the camps of a Blackfeet Tribe lived two children, orphaned in youth. The brother was stone deaf, but the sister was very beautiful, so the girl was made much of, but the boy was ignored by every one.

“Finally the girl was adopted by a Chief who had no children, but the squaw would not have the deaf boy about her lodge. The sister begged that her brother be allowed to live with her, but the squaw was obdurate and prevailed. So the poor lad was kicked about and thrust away from every tent where he stopped to ask for bread.

“Good Arrow, which was the boy’s name, kept up his courage and faith that all would still be righted for him. The sister cried for her brother’s companionship until a day when the tribe moved to a new camp. Then the lad was left behind.

“Good Arrow lived on the scraps that he found in the abandoned camp until, at last, he had consumed every morsel of food. He then started along the trail worn by the moving tribe. It was not a long journey, but he had had no food for several days now, and he knew not where to find any until he reached his sister.

“He was traveling as fast as he could run, and his breath came pumping forth like gusts from an engine. The perspiration streamed from every pore, and he felt dizzy. Suddenly something sounded like a thunderclap inside his head, and he felt something snap. He placed both hands over his ears for a moment, and felt something soft and warm come out upon the palms. He looked, and to his consternation saw that a slender waxen worm had been forced from each ear.

“Then he heard a slight sound in the woods. And he realized, with joy, that he could hear at last! So distinctly could he hear, that he heard a wood-mouse as it crept carefully through the grass a distance from the trail.

“Almost bursting with joy and happiness over his good news, he ran on regardless of all else. He wanted only to reach his sister and tell her.

“But that same morning the Chief, who had adopted the girl, announced to his squaw that he could not stand the memory of the lad’s sad face when the tribe abandoned him. The Chief declared that he was going back and adopt the poor child, so he could be with his sister.

“In spite of his wife’s anger the Chief started back, but met the boy not far down the trail. The lad cried excitedly and showed the waxen worms upon his palms in evidence of his story. The Chief embraced him and told him what he had planned to do that very day. Good Arrow was rejoiced at so much good fortune, and determined to be great, and do something courageous and brave for his Chief.

“He grew to be a fine young brave, more courageous and far more learned in all ways than any other youth in the tribe. Then one day he spoke to his Chief:

“‘I want to find Medicine, but know not where to get it.’

“‘Be very brave, fearless with the enemy, exceedingly charitable to all, of kind heart to rich and poor alike, and always think of others first,—then will the Great Spirit show you how to find Medicine,’ replied the Chief.

“‘Must I be kind to Spotted Bear? He hates me and makes all the trouble he can, in camp, for me,’ returned Good Arrow.

“‘Then must you love Spotted Bear, not treat him as an enemy, but turn him into a friend to you. Let me tell you his story,’ said the Chief.

“‘One day Spotted Bear took a long journey to a lake where he had heard of wonderful Medicine that could be had for the asking. He says he met a stranger who told him how to secure the Medicine he sought. And to prove that he had found it he wears that wonderful robe, which he claims the Great Medicine Man presented to him. He also told us, upon his return, of great dogs that carried men as easily as baggage.

“‘We asked him why he had not brought back the dogs for us, and he said that they were not for us, but were used only by the gods that lived near the lake where he met the Medicine Man.’

“Good Arrow listened to this story and then exclaimed, ‘I shall go to this lake and ask the Medicine Man to give me the dogs.’

“All the persuasions of his sister failed to change his determination, so he started one day, equipped for a long journey. When Spotted Bear heard that Good Arrow had gone for the dogs he had failed to bring to camp, he was furious and wanted to follow and kill the youth. The other braves restrained him, however.

“Good Arrow traveled many days and finally arrived at a lake such as had been described to him by the Chief. Here he saw an old man who asked him what he sought.

“‘Knowledge and wisdom to rule my people justly.’

“‘Do you wish to win fame and wealth thereby?’ asked the bent-over old man.

“‘I would use the gifts for the good of the tribe, to help and enlighten every one,’ returned Good Arrow.

“‘Ah! Then travel south for seven days and you will come to a great lake. There you will meet one who can give you the Medicine you crave. I cannot do more.’

“Then the young brave journeyed for seven days and seven nights, until, utterly exhausted, he fell upon the grass by the side of the trail. How long he slept there, he knew not; but upon awakening, he saw the great lake spread out before his eyes, and standing beside him was a lovely child of perfect form and features.

“Good Arrow smiled on the child; then the little one said, ‘Come, my father said to bring you. He is waiting to welcome you.’

“With these words spoken, the child ran straight into the lake and disappeared under the water.

“Fearfully the youth ran after, to save the little one. He plunged into the deep water, thinking not of himself, but of how to rescue the babe.

“As he touched the water, it suddenly parted and left a dry trail that ran over to a wonderful lodge on the other side. He now saw the child running ahead and calling to a Chief who stood before the lodge.

“Good Arrow followed and soon met the Chief whom he found to be the Great Medicine Man he had sought. The purpose of his journey was soon explained, then the Chief beckoned Good Arrow to follow him.

“‘I will show you the elk-dogs that were sent from the Great Spirit for the use of mortals. But no man has been found good enough or kind enough to take charge of them.’

“Then Good Arrow was taken to the wide prairie, where he saw the most wonderful animals feeding. They were larger than elk and had shining coats of hair. They had beautiful glossy manes and long sweeping tails. Their sensitive ears and noses were quivering in wonderment as they watched a stranger going about their domain.

“‘Young man of the earth,’ said the Chief, patting one of the animals that nuzzled his hand, ‘these are the horses that were meant for mankind. If you wish to take them back with you it is necessary that you learn the Medicine I have prepared for you.’

“Good Arrow was thrilled at the thought that perhaps he might be the one to bring this blessing on man. He thought not of the wealth and fame such a gift would bring to him. The Chief smiled with pleasure.

“‘Ah, you have passed the first test well. This offer to you, that might well turn a great Chief’s head, only made you think of the good it would bring to the children of earth. It is well.’

“So every lesson given Good Arrow was not so much for muscular power or physical endurance, but tests of character and moral worth. The youth passed these tests so creditably that the Chief finally said, ‘My son, you shall return to your people with this great gift from the Spirit, if you pass the last test well.’

“‘Journey three days and three nights without stopping, and do not once turn to look back! If you turn, you shall instantly be transformed into a dead tree beside the trail. Obey my commands, and on the third night you shall hear the hoofs of the horses who will follow you.

“‘Leap upon the back of the first one that comes to you, and all the others will follow like lambs to to the camp you seek.

“‘Now let me present you with a token from myself. This robe is made for Great Medicine Chiefs,’ and as he spoke the Chief placed a mantle like his own over Good Arrow’s shoulders. And in his hand he placed a marvelous spear.

“Good Arrow saw that the robe was exactly like the one worn by Spotted Bear, but he asked no questions about it. When the Chief found the young brave was not curious, he smiled, and said, ‘Because you did not question me about Spotted Bear, I will tell you his story, that you may relate it again to the tribe and punish him justly for his cowardice.

“‘Spotted Bear reached the lake where the child stood, but he would not follow her into the water,—not even to rescue her, when she cried for help. He was driven back by evil spirits, and when he found the old man who had sent him onward to find the elk-dogs, he beat him and took away his robe. That is the robe he now wears, but I permitted him to wear it until a brave youth should ask questions regarding its beauty,—then will it have accomplished its work. You are the youth, and now you hear the truth about Spotted Bear. Judge righteous judgment upon him, and do not fear to punish the crime.

“‘Now, farewell, Good Arrow. You are worthy to guide my horses back to mortals. The robe will never wear out, and the spear will keep away all evil spirits and subdue your enemies.’

“When Good Arrow would have thanked the Chief, he found he was alone upon the shore where he first saw the child. Had it not been for the gorgeous robe upon his back and the spear in his hand, he would have said it was all a dream from which he had but just awakened.

“He turned, as he had been commanded, and straightway journeyed along the trail. He went three days and three nights before he heard a living thing. Then the echoes of hoofbeats thudded on the trail after him. But he turned not.

“Soon afterward, a horse galloped up beside him, and as he leaped upon its back, it neighed. The others followed after the leader, and all rode into camp, as the great Chief had said it would be.

“Great was the wonderment and rejoicing when Good Arrow showed his people the marvelous steeds and told his story. The robe and spear bore him out in his words. But Spotted Bear turned to crawl away from the campfire. Then Good Arrow stood forth, and said in a loud voice of judgment, ‘Bring Spotted Bear here for trial.’

“The story of his cowardice and theft was then related to the tribe, and the judgment pronounced was for the outcast to become a nameless wanderer on the earth. Even as the Chief spoke these words of punishment, the robe he had always bragged about, fell from his back and turned into dust at his feet.

“Thus came the Spirit’s gift of horses to mankind, and Good Arrow became a wise Medicine Man of the Blackfeet.”

Tally concluded his story, and resumed his pipe as if there had been no prolonged lapse between his smokes.

“That was a splendid story, Tally,” said the Captain, as Tally concluded his legend.

“Yes, I like it better than those I have read of the First Horses in books from the Smithsonian Institution,” added Mrs. Vernon.

“Him true story! My Chief tell so,” declared Tally, positively, and not one of the scouts refuted his statement.

“Well, I don’t know how you girls feel, but I will confess that I’m ready for a nap,” remarked Mr. Gilroy, trying to hide a yawn.

“No objections heard to that motion,” declared Mr. Vernon.

“Not after such a day’s voyage in this schooner,” laughed Julie. “I’ll be fast asleep in a jiffy.”

So the blankets were spread out over the floor of the wagon, and the girls rolled themselves into them, and stretched out as planned. The planks of the floor were awfully hard and there seemed to be ridges just where they were not wanted. Directly under Julie’s back was a great iron bolt but she could not move far enough to either one side or the other to avoid it. So she doubled her blanket over it, and left her feet upon the bare wooden planks.

“I’m thankful there are no tall members in this Troop,” remarked the Captain, after they were all settled in a row. “If there were, her feet would have to hang over the side of the wagon.”

Tally and the two men spread out their rubber covers in front of the fire, and all were soon asleep.

Julie’s brag about falling fast asleep in a jiffy proved false, for she could not rest comfortably because of the bolt. So her sleep was troubled and she half-roused several times, although she did not fully awaken. Then, during one of these drowsy experiences when she tried to get on one side of the bolt, she heard a strange sound.

She sat up and looked around. It was still dark, although the first streaks of dawn were showing in the sky. Her companions were stretched out under their covers, and Mrs. Vernon was softly snoring. Julie lifted a corner of the canvas curtain to ascertain what it was that awakened her, and she saw a suspicious sight.

The guide was in the act of getting upon his feet without disturbing the two men who slept soundly by the fireside. He waved a hand, as a signal, towards the brush some ten feet away. And there Julie saw a hand and arm motioning him, but no other part of its owner could be seen.

“Well I never!” thought Julie to herself, as she watched Tally creep away from the fire and make for the bushes.

He was soon hidden behind the foliage, and then Julie heard sounds as of feet moving along the forest trail.

“I’m not going to let him put anything over on us, if I know it!” thought she. And she quickly stepped over the quiet forms in the wagon, and slid down from the back of the schooner. That night the scouts had on moccasins, fortunately, and her feet made no sound as she swiftly followed the Indian through the screen of leaves. Then she saw, some dozen yards ahead of her, two forms hurrying up a steep trail that ran through the forest. One was Tally, and his companion was an Indian maiden.

Unseen, Julie softly followed after them, and finally they came to a roaring mountain torrent that was bridged by a great fallen pine. On the other side of this stream were two shining black horses, with manes and tails so long and thick that the scout marveled. They were caparisoned in Indian fashion with gay colors and fancy trappings.

The maiden quickly loosed the steeds and Tally sprang up into one saddle, while the squaw got up into the other. Then they continued up along the trail without as much as a glance behind.

Julie managed to creep over the treetrunk and gained the other side of the torrent, then ran after them as fast as she could go. But they had disappeared over the crest and the scout had to slow up, as her breath came in panting gasps.

Finally she, too, reached the summit, but there was no sign of horses or riders. A wide cleared area covered the top of the mountain, from which a marvelous view of Denver and its environs could be had. Distant peaks now glimmered in the rising sun, and Julie sighed in ecstasy at such a wonderful sight.

Then she remembered what brought her there, and she ran across the clearing to look for a trail down the other side and, perchance, a glimpse of the Indians.

Passing a screen of thick pines, she suddenly came to an old flower garden, and on the other side of it stood a rambling old stone castle, similar to Glen Eyrie at Colorado Springs.

“Humph! This looks as if some one tried to imitate General Palmer’s gorgeous castle, but gave it up in despair,” thought she.

Julie walked across the intervening space and reached the moss-grown stone steps that led to a great arched doorway. She had a glance, through wide-opened doors, of gloomy hallway and a great staircase, then she skirted the wing of the building, and came out to a wide terrace that ran along the entire front of the pile. The view from this high terrace caused her to stand perfectly still and gaze in awe.

She could see for miles and miles over the entire country from the height she stood upon. It was almost as wonderful a view as that from Pike’s Peak. Sheer down from the stone terrace dropped a precipice of more than five thousand feet. Far down at its base she could see a stream winding a way between dots of ranches and narrow ribbons of roadways.

“This is the most marvelous scene yet!” murmured Julie. Then she frowned as a thought came to her. “If Tally knew of this place,—and it is evident that he did,—why did he not tell us of it, so that we could climb up and see it in the morning? And why isn’t this old castle on the road-map, with a note telling tourists of the magnificent view from this height?”

After a long time given to silent admiration of the country as seen from the terrace, Julie turned and slowly walked up the stone steps that led into the hall. “Wonder if the place is abandoned,” thought she, peeping inside the doorway.

As no sound or sign of life was evident, she tiptoed in and gazed about. The tiles on the floor were of beautiful design and coloring, and the woodwork was tinted to correspond. The walls were covered with rare old tapestries, while here and there adown the length of the hall stood suits of armor and mailed figures.

Bronze chandeliers hung from the high ceilings, and on each side of the hall stood bronze torchères holding gigantic wax candles.

“Well, in all my life I never dreamed of visiting such a museum of old relics!” sighed Julie, who dearly loved antiques.

Suddenly, as silently as everything else about the place, there appeared a white-haired servitor in baronial uniform. He came forward and deferentially bowed, then he spoke to Julie.

“Are you the Indian maiden the guide was to meet to-day?”

Julie was so amazed at the question that she could not reply, so she barely nodded her head.

“Then follow me, as the master waits. The guide sits below, eating breakfast,” added the old servant.

At the mention of breakfast, Julie felt her empty stomach yearn for a bite of it, but she silently turned and followed the major-domo, as she knew him to be, along the hall and up the stairs. As they reached the first landing the old man said, “The master is in his laboratory in the tower. Breakfast will be served there.”

Julie accepted this as cheerful news, so she fearlessly followed after the guide. She had seen no tower from the outside of the rambling building, but, she thought, there might have been one at the wing opposite the one around which she came when she walked to the front of the place.

Having reached the top of the stairs, Julie saw that the entire second-floor walls were covered with ancient portraits. She would have loved to stop and study the ancient costumes of the women, but the man ascended the second flight of stairs, and she must follow.

They went along the hall on the third floor, and at the end the servitor entered a small room that was heavily hung with velour portières. He pushed them aside and turned a knob that seemed to be set in the carved panel. Instantly this panel swung open and disclosed a narrow spiral stairway leading to an iron platform overhead.

Julie began to question the wisdom of this reckless act of hers; but having come so far, how could she back out gracefully? Why should this master want to breakfast with an Indian squaw—for such he was expecting?

“This way,” politely reminded the old man, and Julie had to see the thing through to the end—whatever that might be.

At the head of these spiral stairs the man pulled on a heavy cord, and another hidden door set in carved panelling opened. Through this they went, and then the man said:

“Be seated, and I will call the master.”

Julie gazed about her in profound curiosity. The room was an octagon-shaped laboratory, so dark that its corners were in shadow. The only light came from a huge glass dome ceiling. One side of the room was taken up by a great fireplace; opposite this stood a high cabinet filled with the vials and other equipment of a chemist. The paneled door through which she came took up the third side, and the five other sides were filled with tiers of shelves, where stood rows of morocco-bound books.

Great leather chairs stood about the room, and in the center, upon a magnificent Kirmanshaw rug, stood an onyx table with a great crystal globe upon it. At one side, near the narrow door through which the old servant had gone, stood a grand piano.

Julie had no time for further inspection of the room, as a unique figure suddenly appeared in the small doorway through which the servitor had gone. He was very tall and thin, and was clad in wonderfully embroidered East Indian robes. A fez cap covered the bald head on top, and a thin straggly white beard fringed the lower part of his face. Upon his scrawny finger a strange stone glittered and instantly attracted her gaze.

Julie wondered who this unusual person might be, but he vouchsafed no information. In fact, he stood perfectly still as if waiting for her to open the conversation. This proved to be the fact, for he gazed searchingly at the girl, and then murmured, “Well?”

Julie tried to summon a smile and act nonchalant, but the entire atmosphere of the place was too oppressive for such an air, so she stood, changing her weight from one foot to the other. This form of action—or to be more exact, inaction—continued for a few minutes, then the old man gave vent to a hollow laugh. It sounded so sepulchral that Julie shivered with apprehension.

He started to cross the room. When he came within a few feet of his guest he said, raspingly, “Maiden, I know thee. Thou’rt a descendant of Spotted Bear, the coward! And I—I am the young Medicine Man who won the robe and spear, and brought the horses to earth for mankind to use. Hast aught to say to that?”

At these words Julie was too amazed to answer. To see the hero of that wonderful Indian legend standing before her eyes—but oh, how old he must be, for that happened ages ago, and his yellow parchment-like skin attested to a great age.

As she thought over these facts, she could not keep her eyes from the old man’s face, and now she actually could trace a resemblance to the young guide, Tally. Could the latter be a descendant of this Medicine Man’s? As if the old fellow read her thoughts, he chuckled, “Aye! The guide is one of my tribe, and thou art a member of that of the outcast, Spotted Bear. Because I have found thee, I shall see that no descendant of that coward’s goes forth again to trouble the world.”

Julie began to fear that she had been very indiscreet in coming into this old ruin as she had done, especially as she would find it difficult to convince this old man that she was not the Indian maiden he thought her to be. But she paid attention to his next act, which was to pull out a great chair and drop back in it as if too weary to stand longer upon his spindling legs.

“Art hungry? Even my enemy must not complain of our bounty.” So saying, the old man reached forth a long thin arm and his fingers pushed upon a button in the wall. Instantly a panel moved back and disclosed a cellaret built into the wall. Here were delicious fruits, cakes, and fragrant coffee.

“Help thyself. I will wait till thou art done,” said he, waving his hand at the food.

Julie was so hungry that the sight of the fruit made her desperate. Had her future welfare depended upon it, she could not have withstood the temptation to eat some of that fruit. She went over to take an orange, but a horrible thrust in her back caused her to cry out and put both hands behind her.

To her horror she found the old man had thrown some hard knob at her and it had made such a dent in her flesh that it could be distinctly felt at the base of her spine. The insane laughter that greeted her wail of pain made her realize that she was in the presence of a madman!

“Why not eat, Maiden? I will amuse myself, meantime,” said the old man, as he finished his laughter.

Julie saw him rise and hobble over to the piano, then seat himself before the keyboard and begin to play the weirdest music she had ever heard. But the pain in her back continued so that the thought of breakfast vanished. All she cared for now was to get rid of that suffering.

When she could stand the agony no longer, she gathered courage enough to limp over to the piano and beg him to release her, as she was in great pain.

“Aha! Didst ever think of how Spotted Bear caused the child to suffer when it went down in the water?” asked he, suspending his hands over the piano keys.

“But I hadn’t anything to do with that! Why strike me for his crimes?” retorted Julie, gaining courage in her pain.

The old man frowned at her fiercely, and mumbled, “Art obstinate? Then we’ll have to use other ways.” He turned and pushed another button in the wall back of the piano, and instantly the glass dome overhead became darkened, so that Julie could not see the objects in the room very plainly.

The host got up and started slowly for Julie. His eyes seemed afire with a maniac’s wildness, and the scout feared he was planning to attack her. She screamed for help, and ran for the door in the paneling through which she had entered. But the cry seemed muffled in her throat and no audible sound came forth.

The host laughed that same horrible laugh again, and Julie tried again, harder than ever, to shout for help. Still her vocal chords seemed paralyzed, and no sound was heard from them.

Just as she reached the paneling, the old man must have hurled another hard ball at her, for she felt the blow in her back and shrunk with the pain. And as she squirmed, she distinctly felt the painful object move from one side of her spine to the other, as if it were a button under the skin that was movable.

But the door in the panel could not be opened, and Julie worked her hands frantically over its surface, while the old Indian laughed and crept closer to her. When he was near enough to reach out and take her in his awful hands, the scout gathered all her courage and flung herself upon him.

She fought with hands and teeth, and kicked with her feet, hoping that his great age would render him too weak to resist her young muscular strength. She knew she must overpower him or he would kill her, mistaking her for the maiden descended from Spotted Bear.

She had thus far won the hand-to-hand fight, so that he was down upon his knees and she was over him with her hands at his throat, when suddenly he collapsed, and his eyes rolled upwards at her. In her horror she managed to yell for help, and then she heard—

“Julie! Julie! Have mercy! Stop tearing Betty to bits!”

Through a vague distance Julie recognized the voice of Joan. Oh, if they were only there to help! But she kept a grip on the old Chief’s neck while she waited to answer the call.

Then she heard very plainly, “For the love of Pete, Julie, wake up, won’t you!” And some one shook her madly.

Julie sat up and rubbed her eyes dazedly, while the scouts about her laughed wildly, and Betty scolded angrily.

“Oh, Julie, what an awful nightmare you must have had,” laughed Mrs. Vernon.

“Is Tally back?” asked Julie.

“He’s cooking breakfast,—smell it,” said Anne, smacking her lips.

“I can smell coffee,” mumbled Julie, still unconvinced that she had been dreaming. “It smells exactly like that old man’s.”

“What old man?” again asked the circle about her.

“Why, Good Arrow, to be sure! He lives up on that hill—and, girls, he’s as old as Methusaleh, I’m sure!” declared Julie.

The wild laughter that greeted this serious statement of hers did more to rouse the Leader from a cloudy state of mind than anything else, and soon she was up and out of the wagon to look for a trail that might run over the crest of the hill.

But there was no trail, neither was there a mountain climb such as she remembered in her dreams. At breakfast, she told the dream, to the intense amusement of every one, Tally included. Then the Indian guide remarked, “No better sleep on iron bolt, nex’ time!”

“I hope we can say good-by to the old wagon to-day,” said the Captain, after they were seated again, ready to resume the journey.

“You seem not to like our luxurious schooner?” laughed Mr. Gilroy.

“Luxurious! Had we but known what this ride would be like I venture to say every scout would have chosen to walk from Denver,” exclaimed Mrs. Vernon.

“And here I’ve been condemning myself as being the only ingrate in the party!” returned Mr. Gilroy. “I remember with what enthusiasm the scouts hailed the suggestion of traveling a la prairie schooner.”

As the wagon came out from the screen of trees where they had camped for the night, the scouts saw the vapors in the valley eddy about and swiftly vanish in the penetrating gleams from the rising sun. Here and there patches of vivid green lay revealed, but in another half hour the sun would be strong enough, with the aid of a stiff breeze, to dispel all the clinging mists of night into their native nothingness.

“Just as our earthly pains and sorrows go,” remarked Mrs. Vernon.

“Yes, Verny, just like Julie’s dream, eh? She woke up and could hardly believe that she was here—safe and happy,” added Joan.

The road was rough and the joggling was as bad as ever, but the scouts were not so resigned as they had been the day before. Every little while they asked, “Now how far are we from Boulder?” for there they would have surcease from such “durance vile” as this mode of travel imposed upon them.

To distract their attention from physical miseries, Mr. Vernon asked a question, knowing that Mr. Gilroy would instantly divine his intention and follow it up.

“Gilroy, how do you explain the queer fact that the higher we go on these grand heights, the more stunted we find the trees? One would expect to find beautiful timber on top.”

The scouts listened with interest, and Mr. Gilroy noted this and consequently took the cue given him.

“Why, timber-line in the West, Vernon, means more than the end of the forest growth. Most trees near the top of the peaks are stunted by the cold, or are twisted by the gales, and become bent or crippled by the fierce battles they have to wage against the elements. But they are not vanquished—oh, no!

“These warriors of the forests seem to realize with a fine intelligence how great is their task. They must protect the young that grow on the sides further down the mountain; they must hold back the destroying powers of the storm, that the grand and beautiful scions of this forest family be not injured. They have learned, through many courageous engagements with Nature’s fierce winters, that the post appointed them in life can never offer them soft and gentle treatment while there remains such work as theirs to do, work that needs tried strength and brave endurance.

“I have never found a coward growing in the ranks of the closely-linked, shoulder-to-shoulder front of trees that mark the timber-line. Although they may not seem to grow, materially, more than from eight to twelve feet high, and though many look deformed by the overwhelming conditions, so that they present strange shapes in comparison with the erect tall giants down the mountainside, yet I love to remember that in His perfect Creation, these same fighters have won greatness and eternal beauty for their service to others.

“In most cases, you will find that the higher the altitude of the peak and the wilder the winds, the closer grow the trees, as if to find increase of strength in the one united front that they present to the storms. These winter gales are so powerful that they tear at every object offering resistance to their destructive force. Thus the limbs growing on the outer side of the trees on timber-line are all torn away, or twisted back upon the parent trunk.

“But there are times when even the most valiant defenders of the forest are momentarily overpowered. There comes a blizzard; the gale howls and shrieks as it tears back and forth for days at a stretch, trying to force a passage through the defence line. And sometimes a little soldier is rooted up with malignant fury, and used by the merciless gale to batter at his companions. This generally proves futile, however.

“It is not always in the wintertime that the most terrific blizzards occur in the Rockies. In July, when all the country is pining for a breeze, these peaks produce blizzards that surpass anything heard of in winter, and these summer storms are the most destructive, as the trees are green and full of tender tips, that are ruthlessly torn off during the gale.

“Then, too, the summer months generally produce the awful snowslides you hear about, that are quite common in the Rockies.”

“Oh, I wish we could see one of them!” exclaimed Julie, impulsively.

“Child, you don’t know what you are saying!” said Mr. Gilroy, earnestly. “If you ever went through one, as I have, you’d never want to experience another, I assure you.”

“Oh, Gilly! Do tell us about it,” cried the scouts.

And Mr. Vernon added, “Yes, Gilroy, do tell us the story.”

“It was many years ago, while I was on a geological trip through the Rockies. Tally and I were ready to start for a several days’ outing on the peaks when the man we lodged with said, ‘You are going out at a bad time. Some big slides have been reported recently.’

“I, like Julie here, said, ‘I’d like the excitement of riding a slide.’

“The rancher said I was locoed, but he went about his business after that. So I took my snowshoes in case I met a slide and had to ride it.

“Tally and I were soon climbing the trail, and as we went higher and higher, I felt pleasantly excited to see several small slides start from distant peaks and ride ruthlessly over everything to gain a resting-place.

“Then we both heard a rumble and stood looking about. We now beheld a slide quite close at hand—on our own ridge but on the far side. It coasted slowly at first, but gathered momentum as it went, until it was flying downwards.

“It was about fifty feet wide and several hundred feet long, but it cut a clean channel through the forest, carrying great trees, rocks, and other objects on its crest. Before it had traveled five hundred yards, it had gathered into its capacious maw tons of débris, besides the vast blanket of snow it started out with. All this made a resistless force that swept over other forest impedimenta, dragging all along with its flood.

“It looked as if the village that snuggled at the foot of the mountain would be completely smothered and destroyed, when suddenly, the entire river of white was deflected by an erosion that had cut a wayward pathway across the mountainside. This attracted the slide down into the ravine. And as its mass went over the edge of the gulch, fine powdery particles filled the air, but nothing more than a dull, grinding sound rose to me as a tremor shook the ground, and I realized that it had found its end in the canyon.

“Upon my return to the ranch, I was told that that slide had cut down and ruined fifty thousand fine trees. Nothing could be done with them after such a battle with the slide.

“But the next day, as I still thrilled with the memory of the immense slide, I heard a rumbling sound just above where we were. Tally screamed, ‘Look out. She come!’

“I saw snow sliding across a shallow depression above, and heading straight for me. Tally had managed to scramble quickly out of the way, and I worked those snowshoes faster than anything I ever did before or since—believe me!

“Before I could reach a safety zone, however, I was caught in the outer edge of the avalanche and whirled along for some distance. By dint of working those same snowshoes I managed to gain the extreme edge, where I flung myself recklessly out into space, not knowing where I might land.

“Fortunately, I was left sprawling with legs and arms about a pine, while the slide rioted on without me. I lifted my bruised head because I wished to see all I could of it, and I was able to witness the havoc it wrought in its descent. When it reached the bottom of the mountain it collided with a rocky wall on an opposite cliff. The first meeting of the snow with this powerful resistance curled it backward upon itself, while the rest of the slide piled up on top, and quickly filled the narrow valley with its débris.

“Had I not been so near the line of least suction, or had I been in the middle of that fearful slide, nothing could have saved me. I should have been buried under tons of snow even if I survived a death-dealing blow from a rock or tree during the descent.

“Now, Julie, do you still care to experience a hand-to-hand battle with a slide?”

“If it wasn’t for all such thrilling adventures, Gilly, you wouldn’t be so entertaining. When one is in the Rockies, one looks for experiences that go with the Rockies,” declared the girl.

Mr. Gilroy shook his head as if to say Julie was hopeless. But Joan laughingly remarked, “A snowslide wouldn’t be any wilder than Julie’s visit to old man Good Arrow in his castle.”

“And about as frightful as the pit he would have thrown Julie into,” added Mr. Gilroy.

“Joking aside, Scouts. We expect to meet with various thrilling adventures during our sojourn in the Rockies, and I don’t believe one takes such dire risks if one is careful,” said Julie.

“Maybe not, but you are not careful. In fact, you take ‘dire risks’ every time,” retorted Mr. Gilroy.

Nothing was said for a few minutes, then Tally spoke, “Mees’r Gilloy—him come to Boulder, pooty quick!”

“Ha, that’s good news!” remarked Mr. Vernon.

“Yes, and our little scheme worked fine, eh, Uncle,” laughed Mr. Gilroy. But all the coaxings from the scouts could not make either man say what that scheme had been.

At Boulder the party gladly left the wagon for Tally to deliver to his brother, and the horses were turned over to the man they were intended for. While Tally was waiting for his brother’s arrival, Mr. Gilroy found he could conduct his party through the Boulder Canyon, known as “The Switzerland Trail.”

So they got on a train and rode through a canyon which, as the name suggested, was everywhere lined with great boulders of all shapes and sizes. Here a roaring torrent would cleave a way down to the bottom of the canyon, while there an abrupt wall of rock defied the elements and all things else to maintain its stand.

At Tungsten, the end of the trail, the scouts visited the district where this metal is mined. When they were through with the visit, Mr. Gilroy told the girls that Boulder County’s record of income from tungsten alone was more than five million dollars a year.

The State University at Boulder was visited upon the return of the scout tourists to that city. Here the girls learned that the campus covered over sixty acres of ground, and that the university boasted of twenty-two splendidly equipped buildings, equal to any in the world. It also had a library of its own that numbered about eighty-three thousand volumes. The value of the buildings approximated one million, seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars.

“It doesn’t seem possible, when you look around at what this place is—or seems to be!” exclaimed Ruth.