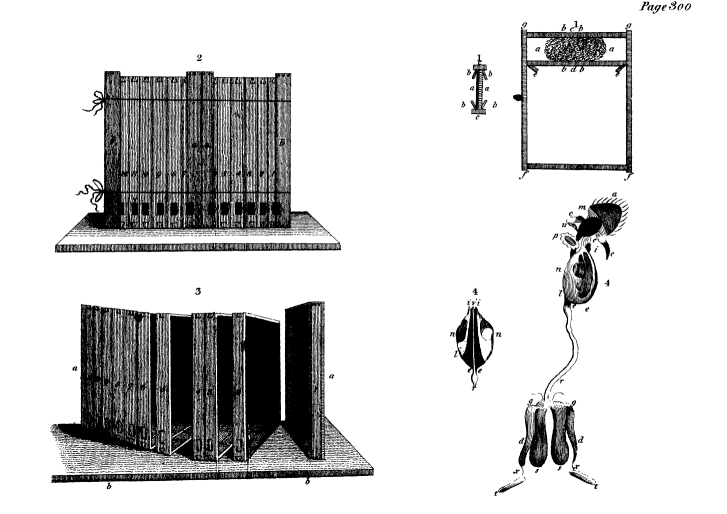

Figures 1 to 4

Figures 1 to 4

The Project Gutenberg EBook of New observations on the natural history of bees, by Francis Huber This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: New observations on the natural history of bees Author: Francis Huber Translator: Anonymous Release Date: August 28, 2008 [EBook #26457] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NEW OBSERVATIONS ON BEES *** Produced by Louise Pryor, Steven Giacomelli and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images produced by Core Historical Literature in Agriculture (CHLA), Cornell University)

The spelling in the original is sometimes idiosyncratic. It has not been changed, but a few obvious errors have been corrected. The corrections are listed at the end of this etext and marked with a mouse-hover.

The four figures appear in a single illustration in the original. In this etext they also appear close to the text that refers to them: Fig 1, Fig 2, Fig 3, Fig 4.

EDINBURGH:

PRINTED FOR JOHN ANDERSON,

AND SOLD BY

LONGMAN, HURST, REES, AND ORME,

LONDON.

ALEX SMELLIE, Printer.

1806.

To

SIR JOSEPH BANKS, Bart.

KNIGHT OF THE MOST HONOURABLE ORDER

OF THE BATH, A PRIVY COUNCILLOR,

PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL

SOCIETY OF LONDON,

&c. &c.

THIS TRANSLATION

IS INSCRIBED.

| LETTER 1.—On the impregnation of the queen bee | page 1 |

| LETTER 2.—Sequel of observations on the impregnation of the queen bee | 41 |

| LETTER 3.—The same subject continued; observations on retarding the fecundation of queens | 44 |

| LETTER 4.—On M. Schirach's discovery | 76 |

| LETTER 5.—Experiments proving that there are sometimes common bees which lay fertile eggs | 89 |

| LETTER 6.—On the combats of queens; the massacre of the males; and what succeeds in a hive where a stranger queen is substituted for the natural one | 108 |

| LETTER 7.—Sequel of observations on the reception of a stranger queen; M. de Reaumur's observations on the subject | 137 |

| LETTER 8.—Is the queen oviparous? What influence has the size of the cells where the eggs are deposited on the bees produced? Researches on the mode of spinning the coccoons | 145 |

| LETTER 9.—On the formation of swarms | 171 |

| LETTER 10.—The same subject continued | 201 |

| LETTER 11.—The same subject continued | 223 |

| LETTER 12.—Additional observations on queens that lay only the eggs of drones, and on those deprived of the antennæ | 237 |

| LETTER 13.—Economical considerations on bees | 253 |

| Appendix | 275 |

The facts contained in this volume are deeply interesting to the Naturalist. They not only elucidate the history of those industrious animals, whose nature is the peculiar subject of investigation, but they present some singular features in physiology which have hitherto been unknown.

The industry of bees has proved a fertile source of admiration in all countries and in every age; and mankind have endeavoured to render it subservient to their gratifications or emolument. Hence innumerable theories, experiments, and observations have ensued, and uncommon patience has been displayed in prosecuting the enquiry. But although many interesting peculiarities have been discovered, they are so much interwoven with errors, that no subject has given birth to more absurdities than investigations into the history of bees: and unfortunately those treatises which are most easily attained, and the most popular, only serve to give such absurdities a wider range, and render it infinitely more difficult to eradicate them. A considerable portion of the following work is devoted to this purpose. The reader will judge of the success which results from the experiments that have been employed.

Perhaps this is not the proper place to bestow an encomium on a treatise from which so much entertainment and instruction will be derived. However, to testify the estimation in which it is held in other nations, the remarks upon it by the French philosopher Sue, may be quoted, 'The observations are so consistent, and the consequences seem so just, that while perusing this work, it appears as if we had assisted the author in each experiment, and pursued it with equal zeal and interest. Let us invite the admirers of nature to read these observations; few are equal to them in excellence, or so faithfully describe the nature, the habits, and inclinations of the insects of which they treat.'

It is a remarkable circumstance that the author laboured under a defect in the organs of vision, which obliged him to employ an assistant in his experiments. Thus these discoveries may be said to acquire double authority. But independent of this the experiments are so judiciously adapted to the purposes in view, and the conclusions so strictly logical, that there is evidently very little room for error. The talents of Francis Burnens, this philosophic assistant, had long been devoted to the service of the author, who, after being many successive years in this manner aided in his researches, was at last deprived of him by some unfortunate accident.

Whether the author has prosecuted his investigation farther does not appear, as no other production of his pen is known in this island.

It is vain to attempt a translation of any work without being to a certain degree skilled in the subject of which it treats. Some parts of the original of the following treatise, it must be acknowledged, are so confused, and some so minute, that it is extremely difficult to give an exact interpretation. But the general tenor, though not elegant, is plain and perspicuous; and such has it been here retained.

SIR,

When I had the honour at Genthod of giving you an account of my principal experiments on bees, you desired me to transmit a written detail, that you might consider them with greater attention. I hasten, therefore, to extract the following observations from my journal.—As nothing can be more flattering to me than the interest you take in my researches, permit me to remind you of your promise to suggest new experimentsA.

After having long studied bees in glass hives constructed on M. de Reaumur's principle, you have found the form unfavourable to an observer. The hives being too wide, two parallel combs were made by the bees, consequently whatever passed between them escaped observation. From this inconvenience, which I have experienced, you recommended much thinner hives to naturalists, where the panes should be so near each other, that only a single row of combs could be erected between them. I have followed your admonitions, Sir, and provided hives only eighteen lines in width, in which I have found no difficulty to establish swarms. However, bees must not be entrusted with the charge of constructing a single comb: Nature has taught them to make parallel ones, which is a law they never derogate from, unless when constrained by some particular arrangement. Therefore, if left to themselves in these thin hives, as they cannot form two combs parallel to the plane of the hive, they will form several small ones perpendicular to it, and, in that case, all is equally lost to the observer. Thus it became essential previously to arrange the position of the combs. I forced the bees to build them perpendicular to the horizon, and so that the lateral surfaces were three or four lines from the panes of the hive. This distance allows the bees sufficient liberty, but prevents them from collecting in too large clusters on the surface of the comb. By such precautions, bees are easily established in very thin hives. There they pursue their labours with the same assiduity and regularity; and, every cell being exposed, none of their motions can be concealed.

It is true, that by compelling these insects to a habitation where they could construct only a single row of combs, I had, in a certain measure, changed their natural situation, and this circumstance might possibly have affected their instinct. Therefore, to obviate every objection, I invented a kind of hives, which, without losing the advantages of those very thin, at the same time approached the figure of common hives where bees form several rows of combs.

I took several small fir boxes, a foot square and fifteen lines wide, and joined them together by hinges, so that they could be opened and shut like the leaves of a bookB. When using a hive of this description, we took care to fix a comb in each frame, and then introduced all the bees necessary for each particular experiment. By opening the different divisions successively, we daily inspected both surfaces of every comb. There was not a single cell where we could not distinctly see what passed at all times, nor a single bee, I may almost say, with which we were not particularly acquainted. Indeed, this construction is nothing more than the union of several very flat hives which may be separated. Bees, in such habitations, must not be visited before their combs are securely fixed in the frames, otherwise, by falling out, they may kill or hurt them, as also irritate them to that degree that the observer cannot escape stinging, which is always painful, and sometimes dangerous: but they soon become accustomed to their situation, and in some measure tamed by it; and, in three days, we may begin to operate on the hive, to open it, remove part of the combs, and substitute others, without the bees exhibiting too formidable symptoms of displeasure. You will remember, Sir, that on visiting my retreat, I shewed you a hive of this kind that had been a long time in experiment, and how much you were surprised that the bees so quietly allowed us to open it.

In these hives, I have repeated all my observations, and obtained exactly the same results as in the thinnest. Thus, I think, already to have obviated any objections that may arise concerning the supposed inconvenience of flat hives. Besides, I cannot regret the repetition of my labours; by going over the same course several times, I am much more certain of having avoided error; and it also appears, that some advantages are found in these which may be called Book or Leaf-hives, as they prove extremely useful in the economical treatment of bees, which shall afterwards be detailed.

I now come to the particular object of this letter, the fecundation of the queen bee; and I shall, in a few words, examine the different opinions of naturalists on this singular problem. Next I shall state the most remarkable observations which their conjectures have induced me to make, and then describe the new experiments by which I think I have solved the problemC.

Swammerdam, who studied bees with unremitting attention, and who never could see a real copulation between a drone and a queen, was satisfied that copulation was unnecessary for fecundation of the eggs: but having remarked that, at certain times, the drones exhaled a very strong odour, he thought this odour was an emanation of the aura seminalis, or the aura seminalis itself, which operated fecundation by penetrating the body of the female. His conjecture was confirmed on dissecting the male organs of generation; for he was so much struck with the disproportion between them and those of the female, that he did not believe copulation possible. His opinion, concerning the influence of the odour, had this farther advantage, that it afforded a good reason for the prodigious number of the males. There are frequently fifteen hundred or two thousand in a hive; and, according to Swammerdam, it is necessary they should be numerous, that the emanation proceeding from them may have an intensity or energy sufficient to effect impregnation.

Though M. de Reaumur has refuted this hypothesis by just and conclusive reasoning, he has failed to make the sole experiment that could support or overturn it. This was to confine all the drones of a hive in a tin case, perforated with minute holes, which might allow the emanation of the odour to escape, but prevent the organs of generation from passing through. Then, this case should have been placed in a hive well inhabited, but completely deprived of males, both of large and small size, and the consequence attended to. It is evident, had the queen laid eggs after matters were thus disposed, that Swammerdam's hypothesis would have acquired probability; and on the contrary it would have been confuted had she produced no eggs, or only sterile ones. However the experiment has been made by us, and the queen remained barren; therefore, it is undoubted, that the emanation of the odour of the males does not impregnate bees.

M. de Reaumur was of a different opinion. He thought that the queen's fecundation followed actual copulation. He confined several drones in a glass vessel along with a virgin queen: he saw the female make many advances to the males; but, unable to observe any union so intimate that it could be denominated copulation, he leaves the question undecided. We have repeated this experiment: we have frequently confined virgin queens with drones of all ages: we have done so at every season, and witnessed all their advances and solicitations to the males: we have even believed we saw a kind of union between them, but so short and imperfect that it was unlikely to effect impregnation. Yet, to neglect nothing, we confined the virgin queen, that had suffered the approaches of the male, to her hive. During a month that her imprisonment continued, she did not lay a single egg; therefore, these momentary junctions do not accomplish fecundation.

In the Contemplation de la Nature, you have cited the observations of the English naturalist Mr Debraw. They appear correct, and at last to elucidate the mystery. Favoured by chance, the observer one day perceived at the bottom of cells containing eggs, a whitish fluid, apparently spermatic, at least, very different from the substance or jelly which bees commonly collect around their new hatched worms. Solicitous to learn its origin, and conjecturing that it might be the male prolific fluid, he began to watch the motions of every drone in the hive, on purpose to seize the moment when they would bedew the eggs. He assures us, that he saw several insinuate the posterior part of the body into the cells, and there deposit the fluid. After frequent repetition of the first, he entered on a long series of experiments. He confined a number of workers in glass bells along with a queen and several males. They were supplied with pieces of comb containing honey, but no brood. He saw the queen lay eggs, which were bedewed by the males, and from which larvæ were hatched, consequently, he could not hesitate advancing as a fact demonstrated, that male bees fecundate the queen's eggs in the manner of frogs and fishes, that is, after they are produced.

There was something very specious in this explanation: the experiments on which it was founded seemed correct; and it afforded a satisfactory reason for the prodigious number of males in a hive. At the same time, the author had neglected to answer one strong objection. Larvæ appear when there are no drones. From the month of September until April, hives are generally destitute of males, yet, notwithstanding their absence, the queen then lays fertile eggs. Thus, the prolific fluid cannot be required to impregnate them, unless we can suppose that it is necessary at a certain time of the year, while at every other season it is useless.

To discover the truth amidst these facts apparently so contradictory, I wished to repeat Mr Debraw's experiments, and to observe more precaution than he himself had done. First, I sought for the fluid, which he supposes the seminal, in cells containing eggs. Several were actually found with that appearance; and, during the first days of observation, neither my assistant nor myself doubted the reality of the discovery. But we afterwards found it an illusion arising from the reflection of the light, for nothing like a fluid was visible, except when the solar rays reached the bottom of the cells. Fragments of the coccoons of worms, successively hatched, commonly cover the bottom; and, as they are shining, it may easily be conceived that, when much illuminated, an illusory effect results from the light. We proved it by the strictest examination, for no vestiges of a fluid were perceptible when the cells were detached and cut asunder.

Though the first observation inspired us with some distrust of Mr Debraw's discovery, we repeated his other experiments with the utmost care. On the 6. of August 1787, we immersed a hive, and, with scrupulous attention, examined the whole bees while in the bath. We ascertained that there was no male, either large or small; and having examined all the combs, we found neither male nymph, nor worm. When the bees were dry, we replaced them all, along with the queen, in their habitation, and transported them into my cabinet. They were allowed full liberty; therefore, they flew about, and made their usual collections; but, it being necessary that no male should enter the hive during the experiment, a glass tube was adapted to the entrance, of such dimensions that two bees only could pass at once; and we watched the tube attentively during the four or five days that the experiment continued. We should have instantly observed and removed any male that appeared, that the result of the experiment might be undisturbed, and I can positively affirm that not one was seen. However, from the first day, which was the sixth of August, the queen deposited fourteen eggs in the workers cells; and all these were hatched on the tenth of the same month.

This experiment is decisive, since the eggs laid by the queen of a hive where there were no males, and where it was impossible one could be introduced, since these eggs, I say, were fertile, it becomes indubitable that the fluid of the males is not required for their exclusion.

Though it did not appear that any reasonable objection could be started against this conclusion, yet, as I had been accustomed in all my experiments to seek for the most trifling difficulties that could arise, I conceived that Mr Debraw's partisans might maintain, that the bees, deprived of drones, perhaps would search for those in other hives, and carry the fecundative fluid to their own habitations for depositing it on the eggs.

It was easy to appreciate the force of this objection, for all that was necessary was a repetition of the former experiments, and to confine the bees so closely to their hives that none could possibly escape. You very well know, Sir, that these animals can live three or four months confined in a hive well stored with honey and wax, and if apertures are left for circulation of the air. This experiment was made on the tenth of August; and I ascertained, by means of immersion, that no male was present. The bees were confined four days in the closest manner, and then I found forty young larvæ.

I extended the precautions so far as to immerse this hive a second time, to assure myself that no male had escaped my researches. Each of the bees was separately examined, and none was there that did not display its sting. The coincidence of this experiment with the other, proved that the eggs were not externally fecundated.

In terminating the confutation of Mr Debraw's opinion, I have only to explain what led him into error; and that was, his using queens whose history he was unacquainted with from their origin. When he observed the eggs produced by a queen, confined along with males, were fertile, he thence concluded that they had been bedewed by the prolific fluid in the cells: but to render his conclusion just, he should first have ascertained that the female never had copulated, and this he neglected. The truth is, that, without knowing it, he had used, in his experiments, a queen after she had commerce with the male. Had he taken a virgin queen the moment she came from the royal cell, and confined her along with drones in his vessels, the result would have been opposite; for, even amidst a seraglio of males, this young queen would never have laid, as I shall afterwards prove.

The Lusatian observers, and M. Hattorf in particular, thought the queen was fecundated by herself, without concourse with the males. I shall here give an abstract of the experiment on which that opinion is founded.D

M. Hattorf took a queen whose virginity he could not doubt. He excluded all the males both of the large and small species, and, in several days, he found both eggs and worms. He asserts that there were no drones in the hive, during the course of the experiment; but although they were absent, the queen laid eggs, from which came worms: whence he considers she is impregnated by herself.

Reflecting on this experiment, I do not find it sufficiently accurate. Males pass with great facility from hive to hive; and M. Hattorf took no precaution that none was introduced into his. He says, indeed, there was no male, but is silent respecting the means he adopted to prove the fact. Though he might be satisfied of no large drone being there, still a small one might have escaped his vigilance, and fecundated the queen. With a view to clear up the doubt, I resolved to repeat his experiment, in the manner described, and without greater care or precaution.

I put a virgin queen into a hive, from which all the males were excluded, but the bees left at perfect liberty. For several days I visited the hive, and found new hatched worms in it. Here then is the same result as M. Hattorf obtained? But before deducing the same consequence from it, we had to ascertain beyond dispute that no male had entered the hive. Thus, it was necessary to immerse the bees, and examine each separately. By this operation, we actually found four small males. Therefore, to render the experiment decisive, not only was it requisite to remove all the drones, but also, by some infallible method, to prevent any from being introduced, which the German naturalist had neglected.

I prepared to repair this omission, by putting a virgin queen into a hive, from which the whole males were carefully removed; and to be physically certain that none should enter, a glass tube was adapted at the entrance of such dimensions that the working bees could freely pass and repass, but too narrow for the smallest male. Matters continued thus for thirty days, the workers departing and returning performed their usual labours: but the queen remained sterile. At the expiration of this time, her belly was equally slender as at the moment of her origin. I repeated the experiment several times, and always with the same consequence.

Therefore, as a queen, rigorously separated from all commerce with the male, remains sterile, it is evident she cannot impregnate herself, and M. Hattorf's opinion is ill-founded.

Hitherto, by endeavouring to confute or verify the conjectures of all the authors who had preceded me, by new experiments, I acquired the knowledge of new facts, but these were apparently so contradictory as to render the solution of the problem still more difficult. While examining Mr. Debraw's hypothesis, I confined a queen in a hive, from which all the drones were removed; the queen nevertheless was fertile. When considering the opinion of M. Hattorf on the contrary, I put a queen, of whose virginity I was perfectly satisfied, in the same situation, she remained sterile.

Embarrassed by so many difficulties, I was on the point of abandoning the subject of my researches, when at length by more attentive reflection, I thought these contradictions might arise from experiments made indifferently on virgin queens, and on those with whose history I was not acquainted from the origin, and which had perhaps been impregnated unknown to me. Impressed with this idea, I undertook a new method of observation not on queens fortuitously taken from the hive, but on females decidedly in a virgin state, and whose history I knew from the instant they left the cell.

From a very great number of hives, I removed all the virgin females, and substituted for each a queen taken at the moment of her birth. The hives were then divided into two classes. From the first, I took the whole males both large and small, and adapted a glass tube at the entrance, so narrow, that no drone could pass, but large enough for the free passage of the common bees. In the hives of the second class, I left all the drones belonging to them, and even introduced more; and to prevent them from escaping, a glass tube, also too narrow for the males, was adapted to the entrance of these hives.

For more than a month, I carefully watched this experiment, made on a large scale; but much to my surprise, all the queens remained sterile. Thus it was proved, that queens confined in a hive would continue barren though amidst a seraglio of males.

This result induced me to suspect that the females could not be fecundated in the interior of the hive, and that it was necessary for them to leave it for receiving the approaches of the male. To ascertain the fact was easy, by a direct experiment; and as the point is important, I shall relate in detail what was done by my secretary and myself on the 29. June 1788.

Aware, that in summer the males usually leave the hive at the warmest time of the day, it was natural for me to conclude that if the queens were also obliged to go out for impregnation, instinct would induce them to do so at the same time as the males.

At eleven in the forenoon, we placed ourselves opposite a hive containing an unimpregnated queen five days old. The sun had shone from his rising; the air was very warm; and the males began to leave the hives. We then enlarged the entrance of that which we wished to observe, and paid great attention to the bees that entered and departed. The males appeared, and immediately took flight. Soon afterwards, the young queen appeared at the entrance; at first she did not fly, but brushed her belly with her hind legs, and traversed the board a little; neither workers nor males paid any attention to her. At last, she took flight. When several feet from the hive, she returned, and approached it as if to examine the place of her departure, perhaps judging this precaution necessary to recognize it; she then flew away, describing horizontal circles twelve or fifteen feet above the earth. We contracted the entrance of the hive that she might not return unobserved, and placed ourselves in the centre of the circles described in her flight, the more easily to follow her and observe all her motions. But she did not remain long in a situation favourable for us, and rapidly rose out of sight. We resumed our place before the hive; and in seven minutes, the young queen returned to the entrance of a habitation which she had left for the first time. Having found no external appearance of fecundation, we allowed her to enter. In a quarter of an hour she re-appeared; and, after brushing herself as before, took flight. Then returning to examine the hive, she rose so high that we soon lost sight of her. Her second absence was much longer than the first; twenty-seven minutes elapsed before she came back. We then found her in a state very different from that in which she was after her first excursion. The sexual organs were distended by a white substance, thick and hard, very much resembling the fluid in the vessels of the male, completely similar to it indeed in colour and consistenceE.

But more evidence than mere resemblance was requisite to establish that the female had returned with the prolific fluid of the males. We allowed this queen to enter the hive, and confined her there. In two days, we found her belly swoln; and she had already laid near an hundred eggs in the worker's cells.

To confirm our discovery, we made several other experiments, and with the same success. I shall continue to transcribe my journal.

On the second of July, the weather being very fine, numbers of males left the hives. We set at liberty an unimpregnated young queen, eleven days old, whose hive had always been deprived of males. Having quickly left the hive, she returned to examine it, and then rose out of sight. In a few minutes, she returned without any external marks of impregnation. In a quarter of an hour, she departed again, but her flight was so rapid that we could scarcely follow her a moment. This absence continued thirty minutes. On returning, the last ring of the body was open, and the sexual organs full of the whitish substance already mentioned. She was then replaced in the hive from which all the males were excluded. In two days, we found her impregnated.

These observations at length demonstrate why M. Hattorf obtained results so different from ours. His queens, though in hives deprived of males, had been fecundated, and he thence concludes that sexual intercourse is not requisite for their impregnation. But he did not confine the queens to their hives, and they had profited by their liberty to unite with the males. We, on the contrary, have surrounded our queens with a number of males; but they continued sterile; because the precaution of confining the males to their hives had also prevented the queens from departing to seek that fecundation without, which they could not obtain within.

These experiments were repeated on queens, twenty, twenty-five, and thirty days old. All became fertile after a single impregnation; however, we have remarked some essential peculiarities in the fecundity of those unimpregnated until the twentieth day of their existence; but we shall defer speaking of the fact until we can present naturalists with observations sufficiently secure and numerous to merit their attention: Yet let me add a few words more. Though neither my assistant nor myself have witnessed the copulation of a queen and a drone, we think that, after the detail which has just been commenced, no doubt of it can remain, or of the necessity of copulation to effect impregnation. The sequel of experiments, made with every possible precaution, appears demonstrative. The uniform sterility of queens in hives wanting males, and in those where they were confined along with them; the departure of these queens from the hives; and the very conspicuous evidence of impregnation with which they return, are proofs against which no objections can stand. But we do not despair of being able next spring to obtain the complement of this proof, by seizing the female at the very moment of copulation.

Naturalists have always been very much embarrassed to account for the number of males found in most hives, and which seem only a burden on the community, since they fulfil no function. But we now begin to discern the object of nature in multiplying them to that extent. As fecundation cannot be accomplished within, and as the queen is obliged to traverse the expanse of the atmosphere, it is requisite the males should be numerous that she may have the chance of meeting some one of them. Were only two or three drones in each hive, there would be little probability of their departure at the same instant with the queen, or that they would meet in their excursions; and most of the females would thus remain sterile.

But why has nature prohibited copulation within the hives? This is a secret still unknown to us. It is possible, however, that some favourable circumstance may enable us to penetrate it in the course of our observations. Various conjectures may be formed; but at this day we require facts, and reject gratuitous suppositions. It should be remembered, that bees do not form the sole republic among insects presenting a similar phenomenon; female ants are also obliged to leave the ant-hills previous to fecundation.

I cannot request, Sir, that you will communicate the reflections which your genius will excite concerning the facts I have related. This is a favour to which I am not yet entitled. But as new experiments will unquestionably occur to you, whether on the impregnation of the queen or on other points, may I solicit you to suggest them? They shall be executed with all possible care; and I shall esteem this mark of friendship and interest as the most flattering encouragement that the continuance of my labours can receive.

Pregny, 13th August 1789.

You have most agreeably surprised me, Sir, with your interesting discovery of the impregnation of the queen bee. It was a fortunate idea, that she left the hive to be fecundated, and your method of ascertaining the fact was extremely judicious and well adapted to the object in view.

Let me remind you, that male and female ants copulate in the air; and that after impregnation the females return to the ant hills to deposit their eggs. Contemplation de la Nature, Part II. chap. 22. note 1. It would be necessary to seize the instant when the drone unites with the female. But how remote from the power of the observer are the means of ascertaining a copulation in the air. If you have satisfactory evidence that the fluid bedewing the last rings of the female is the same with that of the male, it is more than mere presumption in favour of copulation. Perhaps it may be necessary that the male should seize the female under the belly, which cannot easily be done but in the air. The large opening at the extremity of the queen, which you have observed in so particular a condition, seems to correspond to the singular size of the sexual parts of the male.

You wish, my dear Sir, that I should suggest some new experiments on these industrious republicans. In doing so, I shall take the greater pleasure and interest, as I know to what extent you possess the valuable art of combining ideas, and of deducing from this combination results adapted to the discovery of new facts. A few at this moment occur to me.

It may be proper to attempt the artificial fecundation of a virgin queen, by introducing a little of the male's prolific fluid with a pencil, and at the same time observing every precaution to avoid error. Artificial fecundation, you are aware, has already succeeded in more than one animal.

To ascertain that the queen, which has left the hive for impregnation, is the same that returns to deposit her eggs, you will find it necessary to paint the thorax with some varnish that resists humidity. It will also be right to paint the thorax of a considerable number of workers in order to discover the duration of their life. This is a more secure method than slight mutilations.

For hatching the worm, the egg must be fixed almost vertically by one end near the bottom of the cell. Is it true, that it is unproductive unless fixed in this manner? I cannot determine the fact; and therefore leave it to the decision of experiment.

I formerly mentioned to you that I had long doubted the real nature of the small ovular substances deposited by queens in the cells, and my inclination to suppose them minute worms not yet begun to expand. Their elongated figure seems to favour my suspicions. It would therefore be proper to watch them with the utmost assiduity, from the instant of production until the period of exclusion. If the integument bursts, there can be no doubt that these minute substances are real eggs.

I return to the mode of operating copulation. The height that the queen and the males rise to in the air prevent us from seeing what passes between them. On that account, the hive should be put into an apartment with a very lofty ceiling. M. de Reaumur's experiment of confining a queen with several males in a glass vessel, merits repetition; and if, instead of a vessel, a glass tube, some inches in diameter and several feet long, were used, perhaps something satisfactory might be discovered.

You have had the fortune to observe the small queens mentioned by the Abbe Needham, but which he never saw. It will be of great importance to dissect them for the purpose of finding their ovaries. When M. Reims informed me that he had confined three hundred workers, along with a comb containing no eggs, and afterwards found hundreds in it, I strongly recommended that he should dissect the workers. He did so; and informed me that eggs were found in three. Probably without being aware of it, he has dissected small queens. As small drones exist, it is not surprising if small queens are produced also, and undoubtedly by the same external causes.

It is of much consequence to be intimately acquainted with this species of queens, for they may have great influence on different experiments and embarrass the observer: we should ascertain whether they inhabit pyramidal cells smaller than the common, or hexagonal ones.

M. Schirach's famous experiment on the supposed conversion of a common worm into a royal one, cannot be too often repeated, though the Lusatian observers have already done it frequently. I could wish to learn whether, as the discoverer maintains, the experiment will succeed only with worms, three or four days old, and never with simple eggs.

The Lusatian observers, and those of the Palatinate, affirm, that when common bees are confined with combs absolutely void of eggs, they then lay none but the eggs of drones. Thus, there must be small queens producing the eggs of males only, for it is evident they must have produced those supposed to come from workers. But how is it possible to conceive that their ovaries contain male eggs alone?

According to M. de Reaumur, the life of chrysalids may be prolonged by keeping them in a cold situation, such as an ice-house. The same experiment should be made on the eggs of a queen; on the nymphs of drones and workers.

Another interesting experiment would be to take away all the combs composing the common cells, and leave none but those destined for the larvæ of males. By this means we should learn whether the eggs of common worms, laid by the queen in the large cells, will produce large workers. It is very probable, however, that deprivation of the common cells might discourage the bees, because they require them for their honey and wax. Nevertheless, it is likely, by taking away only part of the common cells, the workers may be forced to lay common eggs in the cells of drones.

I should also wish to have the young larvæ gently removed from the royal cell, and deposited at the bottom of a common one, along with some of the royal food.

As the figure of hives has much influence on the respective disposition of the combs, it would be a satisfactory experiment, greatly to diversify their shape and internal dimensions. Nothing could be better adopted to instruct us how bees can regulate their labours, and apply them to existing circumstances. This may enable us to discover particular facts which we cannot foresee.

The royal eggs and those producing drones, have not yet been carefully compared with the eggs from which workers come. But they ought to be so, that we may ascertain whether these different eggs have secret distinctive characteristics.

The food supplied by the workers to the royal worm, is not the same with that given to the common worm. Could we not endeavour, with the point of a pencil, to remove a little of the royal food, and give it to a common worm deposited in a cell of the largest dimensions? I have seen common cells hanging almost vertically, where the queen had laid; and these I should prefer for this experiment.

Various facts, which require corroboration, were collected in my Memoirs on Bees; of this number are my own observations. You can select what is proper, my dear Sir. You have already enriched the history of bees so much, that every thing may be expected from your understanding and perseverance. You know the sentiments with which you have inspired the Contemplator of Nature. Genthod, 18. August 1789.

A All these letters are addressed to the celebrated naturalist M. Bonnet.—T.

B The leaf or book hive consists of twelve vertical frames or boxes, parallel to each other, and joined together. Fig. 1. the sides, f f. f g. should be twelve inches long, and the cross spars, f f. g g. nine or ten; the thickness of these spars an inch, and their breadth fifteen lines. It is necessary that this last measure should be accurate; a a. a piece of comb which guides the bees in their work; d. a moveable slider supporting the lower part; b b. pegs to keep the comb properly in the frame or box; four are in the opposite side; e e. pegs in the sides under the moveable slider to support it.

A book hive, consisting of twelve frames, all numbered, is represented fig. 2. Between 6 and 7 are two cases with lids, that divide the hive into two equal parts, and should only be used to separate the bees for forming an artificial swarm; a a. two frames which shut up the two sides of the hive, have sliders, b. b.

The entrance appears at the bottom of each frame. All should be close but 1 and 12. However it is necessary that they should open at pleasure.

The hive is partly open, fig. 3. and shews how the component parts may be united by hinges, and open as the leaves of a book. The two covers closing up the sides, a. a.

Fig. 4. is another view of fig. 1. a a. a piece of comb to guide the bees; b b. pegs disposed so as to retain the comb properly in the frame; c c. parts of two shelves; the one above is fixed, and keeps the comb in a vertical position; the under one, which is moveable, supports it below.

C I cannot insist that my readers, the better to comprehend what is here said, shall peruse the Memoirs of M. de Reaumur on Bees, and those of the Lusace Society; but I must request them to examine the extracts in M. Bonnet's works, tom. 5. 4to edit. and tom. 10. 8vo, where they will find a short and distinct abstract of all that naturalists have hitherto discovered on the subject.

D Vide M. Schirach's History of Bees, in a memoir by M. Hattorf, entitled, Physical Researches whether the Queen Bee requires fecundation by Drones?

E It will afterwards appear that what we took for the generative fluid, was the male organs of generation, left by copulation in the body of the female. This discovery we owe to a circumstance that shall immediately be related. Perhaps I should avoid prolixity, by suppressing all my first observations on the impregnation of the queen, and by passing directly to the experiments that prove she carries away the genital organs; but in such observations which are both new and delicate, and where it is so easy to be deceived, I think service is done to the reader by a candid avowal of my errors. This is an additional proof to so many others, of the absolute necessity that an observer should repeat all his experiments a thousand times, to obtain the certainty of seeing facts as they really exist.

SIR,

All the experiments, related in my preceding letter, were made in 1787 and 1788. They seem to establish two facts, which had previously been the subject of vague conjecture: 1. The queen bee is not impregnated of herself, but is fecundated by copulation with the male. 2. Copulation is accomplished without the hive, and in the air.

The latter appeared so extraordinary, that notwithstanding all the evidence obtained of it, we eagerly desired to take the queen in the fact; but, as she always rises to a great height, we never could see what passed. On that account you advised us to cut part off the wings of virgin queens. We endeavoured to benefit by your advice, in every possible manner; but to our great regret, when the wings lost much, the bees could no longer fly; and, by cutting off only an inconsiderable portion, we did not diminish the rapidity of their flight. Probably there is a medium, but we were unable to attain it. On your suggestion, we tried to render their vision less acute, by covering the eyes with an opaque varnish, which was an experiment equally fruitless.

We likewise attempted artificial fecundation, and took every possible precaution to insure success. Yet the result was always unsatisfactory. Several queens were the victims of our curiosity; and those surviving remained sterile. Though these different experiments were unsuccessful, it was proved that queens leave their hives to seek the males, and that they return with undoubted evidence of fecundation. Satisfied with this, we could only trust to time or accident for decisive proof of an actual copulation. We were far from suspecting a most singular discovery, which we made in July this year, and which affords complete demonstration of the supposed event, namely, that the sexual organs of the male remain with the female.F

In my first letter, I remarked, that when queens were prevented from receiving the approaches of the male until the twenty-fifth or thirtieth day of their existence, the result presented very interesting peculiarities. My experiments at that time were not sufficiently numerous; but they have since been so often repeated, and the result so uniform, that I no longer hesitate to announce, as a certain discovery, the singularities which retarded fecundation, produces on the ovaries of the queen. If she receives the male during the first fifteen days of her life, she remains capable of laying both the eggs of workers and of drones; but should fecundation be retarded until the twenty-second day, her ovaries are vitiated in such a manner that she becomes unfit for laying the eggs of workers, and will produce only those of drones.

In June 1787, being occupied in researches relative to the formation of swarms, I had occasion, for the first time, to observe a queen that laid none but the eggs of males. When a hive is ready to swarm, I had before observed, that the moment of swarming is always preceded by a very lively agitation, which first affects the queen, is then communicated to the workers, and excites such a tumult among them, that they abandon their labours, and rush in disorder to the outlets of the hive. I then knew very well the cause of the queen's agitation, and it is described in the history of swarms, but I was ignorant how the delirium communicated to the workers; and this difficulty interrupted my researches. I therefore thought of investigating, by direct experiments, whether at all times, when the queen was greatly agitated, even not in the time of the hive swarming, her agitation would in like manner be communicated to the workers. The moment a queen was hatched, I confined her to the hive by contracting the entrances. When assailed by the imperious desire of union with the males, I could not doubt that she would make great exertions to escape, and that the impossibility of it would produce a kind of delirium. I had the patience to observe this queen thirty-four days. Every morning about eleven o'clock, when the weather was fine and the sunshine invited the males to leave their hives, I saw her impetuously traverse every corner of her habitation, seeking to escape. Her fruitless efforts threw her into an uncommon agitation, the symptoms of which I shall elsewhere describe, and all the common bees were affected by it. As she never was out all this time, she could not be impregnated. At length, on the thirty-sixth day, I set her at liberty. She soon took advantage of it; and was not long of returning with the most evident marks of fecundation.

Satisfied with the particular object of this experiment, I was far from any hopes that it would lead to the knowledge of another very remarkable fact; how great was my astonishment, therefore, on finding that this female, which, as usual, began to lay forty-six hours after copulation, laid the eggs of drones, but none of workers, and that she continued ever afterwards to lay those of drones only.

At first, I exhausted myself with conjectures on this singular fact; the more I reflected on it, the more did it seem inexplicable. At length, by attentively meditating on the circumstances of the experiment it appeared there were two principles, the influence of which I should first of all endeavour to appreciate separately. On the one hand, this queen had suffered long confinement; on the other, her fecundation had been extremely retarded. You know, Sir, that queens generally receive the males about the fifth or sixth day, and this queen had not copulated until the thirty-sixth. Little weight could be given to the supposition, that the peculiarity could be occasioned by confinement. Queens, in the natural state, leave their hives only once to seek the males. All the rest of their life they remain voluntary prisoners. Thus, it was improbable that captivity could produce the effect I wished to explain. At the same time, as it was essential to neglect nothing in a subject so new, I wished to ascertain whether it was owing to the length of confinement, or to retarded fecundation.

Investigating this was no easy matter. To discover whether captivity, and not retarded fecundation, vitiated the ovaries, it was necessary to allow a female to receive the approaches of a male, and also to keep her imprisoned. Now this could not be, for bees never copulate in hives. On the same account, it was impossible to retard the copulation of a queen without keeping her in confinement. I was long embarrassed by the difficulty. At length, I contrived an apparatus, which, though imperfect, nearly fulfilled my purpose.

I put a queen, at the moment of her last metamorphosis, into a hive well stored, and sufficiently provided with workers and males; the entrance was contracted so as to prevent her exit, but allowed free passage to the workers. I also made another opening for the queen, and adapted a glass tube to it, communicating with a cubical glass box eight feet high. Hither the queen could at all times come and fly about, enjoying a purer air than was to be found within the hive; but she could not be fecundated; for though the males flew about within the same bounds, the space was too limited to admit of any union between them. By the experiments related in my first letter, copulation takes place high in the air only: therefore, in this apparatus, I found the advantage of retarding fecundation, while the liberty the queen now had, did not render her situation too remote from the natural state. I attended to the experiment fifteen days. Every fine morning, the young captive left her hive; she traversed her glass prison, and flew much about, and with great facility. She laid none during this interval, for she had not united with a male. On the sixteenth day, I set her at liberty: she left the hive, rose aloft in the air, and soon returned with full evidence of impregnation. In two days, she laid, first the eggs of workers, and afterwards as many as the most fertile queens.

It thence followed, 1. That captivity did not alter the organs of queens. 2. When fecundation took place within the first sixteen days, she produced both species of eggs.

This was an important experiment. It rendered my labours much more simple, by clearly pointing out the method to be pursued: it absolutely precluded the supposed influence of captivity; and left nothing for investigation but the consequences of retarded fecundation.

With this view, I repeated the experiment; but, instead of giving the virgin queen liberty on the sixteenth day, I retained her until the twenty-first. She departed, rose high in the air, was fecundated, and returned. Thirty-six hours afterwards, she began to lay: but it was the eggs of males only, and, although very fruitful afterwards, she laid no other kind.

I occupied myself the remainder of 1787, and the two subsequent years, with experiments on retarded fecundation, and had constantly the same results. It is undoubted, therefore, that when the copulation of queens is retarded beyond the twentieth day, only an imperfect impregnation is operated: instead of laying the eggs of workers and males equally, they will lay none but those of males.

I do not aspire to the honour of explaining this singular fact. When the course of my experiments led me to observe that some queens laid only the eggs of drones, it was natural to investigate the proximate cause of such a singularity; and I ascertained that it arose from retarded fecundation. My evidence is demonstrative, for I can always prevent queens from laying the eggs of workers, by retarding their fecundation until the twenty-second or twenty-third day. But, what is the remote cause of this peculiarity; or, in other words, why does the delay of impregnation render queens incapable of laying the eggs of workers? This is a problem on which analogy throws no light: nor in all physiology am I acquainted with any fact that bears the smallest similarity.

The problem becomes still more difficult by reflecting on the natural state of things, that is when fecundation has not been delayed. The queen then lays the eggs of workers forty-six hours after copulation, and continues for the subsequent eleven months to lay these alone: and it is only after this period that a considerable and uninterrupted laying of the eggs of drones commences. When, on the contrary, impregnation is retarded after the twentieth day, the queen begins, from the forty-sixth hour, to lay the eggs of males, and no other kind during her whole life. As, in the natural state, she lays the eggs of workers only, during the first eleven months, it is clear that these, and the male eggs, are not indiscriminately mixed in the oviducts. Undoubtedly they occupy a situation corresponding to the principles that regulate laying: the eggs of workers are first, and those of drones behind them. Farther, it appears that the queen can lay no male eggs until those of workers, occupying the first place in the oviducts, are discharged. Why, then, is this order inverted by retarded copulation? How does it happen that all the workers eggs which the queen ought to lay, if fecundation was in due time, now wither and disappear, yet do not, impede the passage of the eggs of drones, which occupy only the second place in the ovaries. Nor is this all. I have satisfied myself that a single copulation is sufficient to impregnate the whole eggs that a queen will lay in the course of at least two years. I have even reason to think, that a single copulation will impregnate all the eggs that she will lay during her whole life: but I want absolute proof for more than two years. This, which is truly a very singular fact in itself, renders the influence of retarded fecundation still more difficult to be accounted for. Since a single copulation suffices, it is clear that the male fluid acts from the first moment on all the eggs that the queen will lay in two years. It gives them, according to your principles, that degree of animation that afterwards effects their successive expansion. Having received the first impressions of life, they grow, they mature, so to speak, until the day they are laid: and as the laws of laying are constant, because the eggs of the first eleven months are always those of workers, it is evident that those which appear first are also the eggs that come soonest to maturity. Thus, in the natural state, the space of eleven months is necessary for the male eggs to acquire that degree of increment they must have attained when laid. This consequence, which to me seems immediate, renders the problem insoluble. How can the eggs, which should grow slowly for eleven months, suddenly acquire their full expansion in forty-eight hours, when fecundation has been retarded twenty-one days, and by the effect of this retardation alone? Observe, I beseech you, that the hypothesis of successive expansion is not gratuitous; it rests on the principles of sound philosophy. Besides, for conviction that it is well founded, we have only to look at the figures given by Swammerdam of the ovaries of the queen bee. There we see eggs in that part of the oviducts contiguous to the vulva, much farther advanced, and larger than those contained in the opposite part. Therefore the difficulty remains in full force: it is an abyss where I am lost.

The only known fact bearing any relation to that now described, is the state of certain vegetable seeds, which, although extremely well preserved, lose the faculty of germination from age. The eggs of workers may also preserve, only for a very short time, the property of being fecundated by the seminal fluid; and, after this period, which is about fifteen or eighteen days, become disorganised to that degree, that they can no longer be animated by it. I am sensible that the comparison is very imperfect; besides, it explains nothing, nor does it even put us on the way of making any new experiments. I shall add but one reflection more.

Hitherto no other effect has been observed from the retarded impregnation of animals, but that of rendering them absolutely sterile. The first instance of a female still preserving the faculty of engendering males, is presented by the queen bee. But as no fact in nature is unique, it is most probable that the same peculiarity will also be found in other animals. An extremely curious object of research would be to consider insects in this new point of view, I say insects, for I do not conceive that any thing analogous will be found in other species of animals. The experiments now suggested would necessarily begin with insects the most analogous to bees; as wasps, humble bees, mason bees, all species of flies, and the like. Some experiments might also be made on butterflies; and, perhaps, an animal might be found whose retarded fecundation would be attended with the same effects as that of queen bees. Should the animal be larger, dissection will be more easily accomplished; and we may discover what happens to the eggs when retarded fecundation prevents their expansion. At least, we might hope that some fortunate circumstance would lead to solution of the problemG.

Let us now return to my experiments. In May 1789, I took two queens just when they had undergone the last metamorphosis: one was put in a leaf hive, well provided with honey and wax, and sufficiently inhabited by workers and males. The other was put into a hive exactly similar, from which all the drones were removed. The entrances of these hives were too confined for the passage of the females and drones, but the common bees enjoyed perfect liberty. The queens were imprisoned thirty days; and being then set at liberty, they departed, and returned impregnated. Visiting the hives in the beginning of July, I found much brood, but wholly consisting of the worms and nymphs of males. There actually was not a single worker's worm or nymph. Both queens laid uninterruptedly until autumn, and constantly the eggs of drones. Their laying ended in the first week of November, as that of my other queens.

I was very earnest to learn what would become of them in the subsequent spring, whether they would resume laying, or if new fecundation would be necessary; and if they did lay, of what species the eggs would be. However, the hives being very weak, I dreaded they might perish during winter. Fortunately, we were able to preserve them; and from April 1790, they recommenced laying. The precautions we had taken prevented them from receiving any new approaches of the male. Their eggs were still those of males.

It would have been extremely interesting to have followed the history of these two females still farther, but, to my great regret, the workers abandoned their hives on the fourth of May, and that same day I found both queens dead. No weevils were in the hive, which could disturb the bees; and the honey was still very plentiful: but as no workers had been been produced in the course of the preceding year, and winter had destroyed many, they were too few in spring to engage in their wonted labours, and, from discouragement, deserted their habitation to occupy the neighbouring hives.

In my Journal, I find a detail of many experiments on the retarded impregnation of queen bees, so many, that transcribing the whole would be tedious. I may repeat, however, that there was not the least variation in the principle, and that whenever the copulation of queens was postponed beyond the twenty-first day, the eggs of males only were produced. Therefore, I shall limit my narrative to those experiments that have taught me some remarkable facts.

A queen being hatched on the fourth of October 1789, we put her into a leaf-hive. Though the season was well advanced, a considerable number of males was still in the hive; and it here became important to learn, whether, at this period of the year, they could equally effect fecundation; also, in case it succeeded, whether a laying, begun in the middle of autumn, would be interrupted or continued during winter. Thus, we allowed the queen to leave the hive. She departed, indeed, but made four and twenty fruitless attempts before returning with the evidence of fecundation. Finally, on the thirty-first of October, she was more fortunate: She departed, and returned with the most undoubted proof of the success of her amours: She was now twenty-seven days old, consequently fecundation had been retarded. She ought to have begun laying within forty-six hours, but the weather was cold, and she did not lay; which proves, as we may cursorily remark, that refrigeration of the atmosphere is the principal agent that suspends the laying of queens during winter. I was excessively impatient to learn whether, on the return of spring, she would prove fertile, without a new copulation. The means of ascertaining the fact was easy; for the entrances of the hives only required contraction, so as to prevent her from escaping. She was confined from the end of October until May. In the middle of March, we visited the combs, and found a considerable number of eggs, but, none being yet hatched, we could not know whether they would produce workers or males. On the fourth of April, having again examined the state of the hive, we found a prodigious quantity of nymphs and worms, all of drones; nor had this queen laid a single worker's egg.

Here, as well as in the preceding experiment, retardation had rendered the queens incapable of laying the eggs of workers. But this result is the more remarkable, as the queen did not commence laying until four months and a half after fecundation. It is not rigorously true, therefore, that the term of forty-six hours elapses between the copulation of the female and her laying; the interval may be much longer, if the weather grows cold. Lastly, it follows, that although cold will retard the laying of a queen impregnated in autumn, she will begin to lay in spring without requiring new copulation.

It may be added, that the fecundity of the queen, whose history is given here, was astonishing. On the first of May, we found in her hive, besides six hundred males, already flies, two thousand four hundred and thirty-eight cells, containing either eggs or nymphs of drones. Thus, she had laid more than three thousand male eggs during March and April, which is above fifty each day. Her death soon afterwards unfortunately interrupted my observation, I intended to calculate the total number of male eggs that she should lay throughout the year, and compare it with those of queens whose fecundation had not been retarded. You know, Sir, that the latter lay about two thousand male eggs in spring; and another laying, but less considerable, commences in August, also in the interval, that they produce the eggs of workers almost solely. But it is otherwise with the females whose copulation has been retarded: they produce no workers' eggs. For four or five months following, they lay the eggs of males without interruption, and in such numbers, that, in this short time, I suppose one queen gives birth to more drones than a female, whose fecundation has not been retarded, produces in the course of two years. It gives me much regret, that I have not been able to verify this conjecture.

I should also describe the very remarkable manner in which queens, that lay only the eggs of drones, sometimes deposit them in the cells. Instead of being placed in the lozenges forming the bottom, they are frequently deposited on the lower side of the cells, two lines from the mouth. This arises from the body of such queens being shorter than that of those whose fecundation has not been retarded. The extremity remains slender, while the first two rings next the thorax are uncommonly swoln. Thus, in disposing themselves for laying, the extremity cannot reach the bottom of the cells on account of the swoln rings; consequently the eggs must remain attached to the part that the extremity reaches. The worms proceeding from them pass their vermicular state in the same place where the eggs were deposited, which proves that bees are not charged with the care of transporting the eggs as has been supposed. But here they follow another plan. They extend beyond the surface of the comb those cells where they observe the eggs deposited, two lines from the mouth.

Permit me, Sir, to digress a moment from the subject, to give the result of an experiment which seems interesting. Bees, I say, are not charged with the care of transporting into cells, the eggs misplaced by the queen: and, judging by the single instance I have related, you will think me well entitled to deny this feature of their industry. However, as several authors have maintained the reverse, and even demanded our admiration of them in conveying the eggs, I should explain clearly that they are deceived.

I had a glass hive constructed of two stages; the higher was filled with combs of large cells, and the lower with those of common ones. A kind of division, or diaphraghm, separated these two stages from each other, having at each side an opening for the passage of the workers from one stage to the other, but too narrow for the queen. I put a considerable number of bees into this hive; and, in the upper part, confined a very fertile queen that had just finished her great laying of male eggs; therefore she had only those of workers to lay, and she was obliged to deposit them in the surrounding large cells from the want of others. My object in this arrangement will already be anticipated. My reasoning was simple. If the queen laid workers' eggs in the large cells, and the bees were charged with transporting them if misplaced, they would infallibly take advantage of the liberty allowed to pass from either stage: they would seek the eggs deposited in the large cells, and carry them down to the lower stage containing the cells adapted for that species. If, on the contrary, they left the common eggs in the large cells, I should obtain certain proof that they had not the charge of transporting them.

The result of this experiment excited my curiosity extremely. We observed the queen several days without intermission. During the first twenty-four hours, she persisted in not laying a single egg in the surrounding cells; she examined them one after another, but passed on without insinuating her belly into one. She was restless, and traversed the combs in all directions: her eggs appeared an oppressive burden, but she persisted in retaining them rather than they should be deposited in cells of unsuitable diameter. The bees, however, did not cease to pay her homage, and treat her as a mother. I was amused to observe, when she approached the edges of the division separating the two stages, that she gnawed at them to enlarge the passage: the workers approached her, and also laboured with their teeth, and made every exertion to enlarge the entrance to her prison, but ineffectually. On the second day, the queen could no longer retain her eggs: they escaped in spite of her, and fell at random. Then we conceived that the bees would convey them into the small cells of the lower stage, and we sought them there with the utmost assiduity; but I can safely affirm there was not one. The eggs that the queen still laid the third day disappeared as the first. We again sought them in the small cells, but none were there. The fact is, they are ate by the workers; and this is what has deceived the naturalists, who supposed them carried away. They have observed the misplaced eggs disappear, and, without farther investigation, have asserted that the bees convey them elsewhere: they take them, indeed, not to convey them any where, but to devour them. Thus nature has not charged bees with the care of placing the eggs in the cells appropriated for them, but she has inspired females themselves with sufficient instinct to know the species of eggs they are about to lay, and to deposit them in suitable cells. This has already been observed by M. de Reaumur, and here my observations correspond with his. Thus it is certain that in the natural state, when fecundation takes place at the proper time, and the queen has suffered from nothing, she is never deceived in the choice of the cells where her eggs are to be deposited; she never fails to lay those of workers in small cells, and those of males in large ones. The distinction is important, for the same certainty of instinct is no longer conspicuous in the conduct of those females whose impregnation has been deferred. I was oftener than once deceived respecting the eggs that such queens laid, for they were deposited indiscriminately in small cells and those of drones; and not aware of their instinct having suffered, I conceived that the eggs in small cells would produce workers; therefore I was very much surprised, when, at the moment they should have been hatched, the bees closed up the cells, and demonstrated, by anticipation, that the included worms would change into drones; they actually became males; those produced in small cells were small, those in large cells large. Thus I must warn observers, who would repeat my experiments on queens that lay only the eggs of males, not to be deceived by these circumstances, and expect that eggs of males will be deposited in the workers cells.

It is a singular fact, that the females, whose fecundation has been retarded, sometimes lay the eggs of males in royal cells. I shall prove, in the history of swarms, that immediately when queens, in the natural state, begin their great laying of male eggs, the workers construct numerous royal cells. Undoubtedly, there is some secret relation between the appearance of male eggs and the construction of these cells; for it is a law of nature from which bees never derogate. It is not surprising, therefore, that such cells are constructed in hives governed by queens laying the eggs of males only. It is no longer extraordinary that these queens deposit in the royal cells, eggs of the only species they can lay, for in general their instinct seems affected. But what I cannot comprehend is, why the bees take exactly the same care of the male eggs deposited in royal cells, as of those that should become queens. They provide them more plentifully with food, they build up the cells as if containing a royal worm; in a word, they labour with such regularity that we have frequently been deceived. More than once, in the firm persuasion of finding royal nymphs, we have opened the cells after they were sealed, yet the nymph of a drone always appeared. Here the instinct of the workers seemed defective. In the natural state, they can accurately distinguish the male worms from those of common bees, as they never fail giving a particular covering to the cells containing the former. Why then can they no longer distinguish the worms of drones when deposited in the royal cells? The fact deserves much attention. I am convinced that to investigate the instinct of animals, we must carefully observe where it appears to err.

Perhaps I should have begun this letter with an abstract of the observations of prior naturalists, on queens laying none but the eggs of males; however, I shall here repair the omission.

In a work, Histoire de la Reine des Abeilles, translated from the German by Blassiere, there is printed a letter from M. Schirach to you, dated 15 April 1771, where he speaks of some hives, in which the whole brood changed into drones. You will remember that he ascribes this circumstance to some unknown vice in the ovaries of the queen; but he was far from suspecting that retarded fecundation had been the cause of vitiation. He justly felicitated himself on discovering a method to prevent the destruction of hives in this situation, which was simple, for it consisted in removing the queen that laid the eggs of males only, and substituting one for her whose ovaries were not impaired. But to make the substitution effectual, it was necessary to procure queens at pleasure; a secret reserved for M. Schirach, and of which I shall speak in the following letter. You observe that the whole experiments of the German naturalist tended to the preservation of the hives whose queens laid none except male eggs; and that he did not attempt to discover the cause of the vice evident in their ovaries.

M. de Reaumur also says a few words, somewhere, of a hive containing many more drones than workers, but advances no conjectures on the cause. However, he adds, as a remarkable circumstance, that the males were tolerated in this hive until the subsequent spring. It is true that bees governed by a queen laying only male eggs, or by a virgin queen, preserve their drones several months after they have been massacred in other hives. I can ascribe no reason for it, but it is a fact I have several times witnessed during my long course of observations on retarded impregnation. In general it has appeared that while the queen lays male eggs, bees do not massacre the males already perfect in the hive. Pregny, 21. August 1791.

G The experiments suggested in this paragraph, recall a singular reflection of M. de Reaumur. Where treating of oviparous flies, he says, it would not be impossible for a hen to produce a living chicken, if, after fecundation, the eggs she should first lay could by any means be retained twenty-one days in the oviducts. Mem. sur. les Insect. tom. 4. mem. 10.

When you found it necessary, Sir, in the new edition of your works, to give an account of M. Schirach's beautiful experiments on the conversion of common worms into royal ones, you invited naturalists to repeat them. Indeed such an important discovery required the confirmation of several testimonies. For this reason, I hasten to inform you that all my researches establish the reality of the discovery. During ten years that I have studied bees, I have repeated M. Schirach's experiment so often, and with such uniform success, that I can no longer have the least doubt on the subject. Therefore, I consider it an established fact, when bees lose their queen, and several workers' worms are preserved in the hive, they enlarge some of their cells, and supply them not only with a different kind of food, but a greater quantity of it, and the worms reared in this manner, instead of changing to common bees, become real queens. I request my readers to reflect on the explanation you have given of so uncommon a fact, and the philosophical consequences you have deduced from it. Contemplation de la Nature, part. II, chap. 27.

In this letter I shall content myself with some account of the figure of the royal cells constructed by bees around those worms that are destined for the royal state, and terminate with discussing some points wherein my observations differ from those of M. Schirach.

Bees soon become sensible of having lost their queen, and in a few hours commence the labour necessary to repair their loss. First, they select the young common worms, which the requisite treatment is to convert into queens, and immediately begin with enlarging the cells where they are deposited. Their mode of proceeding is curious; and the better to illustrate it, I shall describe the labour bestowed on a single cell, which will apply to all the rest, containing worms destined for queens. Having chosen a worm, they sacrifice three of the contiguous cells: next, they supply it with food, and raise a cylindrical inclosure around, by which the cell becomes a perfect tube, with a rhomboidal bottom; for the parts forming the bottom are left untouched. If the bees damaged it, they would lay open three corresponding cells on the opposite surface of the comb, and, consequently, destroy their worms, which would be an unnecessary sacrifice, and Nature has opposed it. Therefore, leaving the bottom rhomboidal, they are satisfied with raising a cylindrical tube around the worm, which, like the other cells in the comb, is horizontal. But this habitation remains suitable to the worm called to the royal state only during the first three days of its existence: another situation is requisite for the other two days it is a worm. Then, which is so small a portion of its life, it must inhabit a cell nearly of a pyramidal figure, and hanging perpendicularly; we may say the workers know it; for, after the worm has completed the third day, they prepare the place to be occupied by its new lodging. They gnaw away the cells surrounding the cylindrical tube, mercilessly sacrifice their worms, and use the wax in constructing a new pyramidal tube, which they solder at right angles to the first, and work it downwards. The diameter of this pyramid decreases insensibly from the base, which is very wide, to the point. During the two days that it is inhabited by the worm, a bee constantly keeps its head more or less inserted into the cell, and, when this worker quits it, another comes to occupy its place. In proportion as the worm grows, the bees labour in extending the cell, and bring food, which they place before its mouth, and around its body, forming a kind of cord around it. The worm, which can move only in a spiral direction, turns incessantly to take the food before its head: it insensibly descends, and at length arrives at the orifice of the cell. Now is the time of transformation to a nymph. As any farther care is unnecessary, the bees close the cell with a peculiar substance appropriated for it, and there the worm undergoes both its metamorphoses.

Though M. Schirach supposes that none but worms three days old are selected for the royal treatment, I am certain of the contrary; and that the operation succeeds equally well on those of two days only. I must be permitted to relate at length the evidence I have of the fact, which will both demonstrate the reality of common worms being converted into queens, and the little influence which their age has on the effect of the operation.