Peace is only a matter of time, says Mr. HUGHES. The ex-Kaiser is said to be of the opinion that Mr. HUGHES might have been more explicit as to who is going to get that "time."

Meanwhile the ex-Kaiser is growing a beard. He evidently has no desire to share the fate of "Wilhelmshaven."

After reading the numerous articles on whether he should be charged with murder or not, we have come to the conclusion that the answer now rests solely between "Yes" or "No."

Mr. DE VALERA has been appointed a delegate of the Irish Republic to the Peace Conference. The fact that he has not ordered the Peace Conference to come to Brixton prison should satisfy doubters like The Daily News that Sinn Fein can be moderate when it wants to.

People in search of quiet amusement will be glad to know that there will be an eclipse of the sun on May 29th.

Owing to the overcrowding of Tube trains we understand there is some talk of men with beards being asked to leave them in the ticket offices.

It is reported that an All-Tube team has applied for admission to the Rugby Union.

A large number of forged five-pound notes are stated to be in circulation in London. The proper way to dispose of one is to slip it between a couple of genuine fivers when paying your taxi fare.

The ancient office of Town Crier of Driffield, which carries with it a retaining fee of one pound per annum, is vacant. Several Army officers anxious to better themselves have applied for the job.

A large number of "sloping desks," made specially for Government Departments, are offered for sale by the Board of Works. The bulk of them, it is understood, slope at 3.30 P.M.

The mysterious disappearance of sheep from Barnstaple has led to the report that some Government Department has fixed a price for sheep.

"It is not practicable," says the London Electric Railway Company, "for passengers to enter Tube cars at one door and leave by the other, because the end cars have only one door." The idea of reserving these cars for persons getting in or out, but not both, appears to have been overlooked.

There is no truth in the report that the lodging, fuel and light allowance of Officers is to be raised from two shillings and sevenpence to two shillings and sevenpence halfpenny per day, the cost of living having increased since the Peninsular War.

"What is reported to be the largest sapphira in the world," says a contemporary, "disappeared when the Bolshevists took Kieff." We suspect that the largest living Ananias had a hand in the affair.

It is not surprising to learn, following the Police Union meeting, that the burglars have decided to "down jemmies" unless the eight-hour night is conceded.

The rumour that there was a vacant house in the Midlands last week has now been officially denied.

With reference to the Market Bosworth woman who, though perfectly healthy, has remained in bed for three years, until removed last week by the police, it now appears that she told the officers that she had no idea it was so late.

"What can be done to make village life more amusing?" asks The Daily Mirror. We are sorry to find our contemporary so ignorant of country life. Have they not yet heard of Rural District Councils?

An Oxted butcher having found a wedding ring in one of the internal organs of a cow, it is supposed that the animal must have been leading a double life.

"In order to live long," says Dr. EARLE, "live simply." Another good piece of advice would be: "Simply live."

A Streatham man who has been missing from his home since November, 1913, has just written from Kentucky. This disposes of the theory that he might have been mislaid in a Tube rush.

"Distrust of lawyers," Mr. Justice ATKIN told the boys of Friars School recently, "is largely caused by ignorance of the law." Trust in them, on the other hand, is entirely due to ignorance of the cost.

Giving evidence at Marylebone against a mysterious foreigner charged with using a forged identity book, the police said they did not know the real name and address of the man. The Bench decided to obviate the difficulty in the matter of the address.

In a Liverpool bankruptcy case last week the debtor stated that he had lost six hundred pounds in one day rabbit-coursing. The Receiver pointed out that he could have almost bought a new set of rabbits for that.

From a list of wedding presents:—

"Case of sauce ladies from Mr. W. ——."—Provincial Paper.

No doubt he was glad to be rid of them.

"The —— National Kitchen has had to close down.... The great majority of the patrons were Army Pap Corps."

Who presumably required only liquid refreshment.

"The German Government has protested to Russia against the 'criminal interference' of olsheviks in the internal affairs of Germany."—Daily Mail.

Much correspondence will now doubtless take place, as it seems evident that the Bolsheviks have sent their initial letter in reply.

"If you belong to any of the following classes," said the Demobilisation advertisement, "do nothing." So Lieut. William Smith did nothing.

After doing nothing for some weeks he met a friend who said, "Hallo, aren't you out yet?"

"Not yet," said William, looking at his spurs.

"Well, you ought to do something."

So Lieut. William Smith decided to do something. He was a pivotal-man and a slip-man and a one-man-business and a twenty-eight-days-in-hospital man and a W.O. letter ZXY/999 man. Accordingly he wrote to the War Office and told them so.

It was, of course, a little confusing for the authorities. Just as they began to see their way to getting him out as a pivotal man, somebody would decide that it was quicker to demobilise him as a one-man-business; and when this was nearly done, then somebody else would point out that it was really much neater to reinstate him as a slip-man. Whereupon a sub-section, just getting to work at W.O. letter ZXY/999, would beg to be allowed a little practice on William while he was still available, to the great disgust of the medical authorities, who had been hoping to study the symptoms of self-demobilisation in Lieut. Smith as evidenced after twenty-eight days' in hospital.

Naturally, then, when another friend met William a month later and said, "Hallo, aren't you out yet?" William could only look at his spurs again and say, "Not yet."

"Better go to the War Office and have a talk with somebody," said his friend. "Much the quickest."

So William went to the War Office. First he had a talk with a policeman, and then he had a talk with a porter, and then he had a talk with an attendant, and then he had a talk with a messenger girl, and so finally he came to the end of a long queue of officers who were waiting to have a talk with somebody.

"Not so many here to-day as yesterday," said a friendly Captain in the Suffolks who was next to him.

"Oh!" said William. "And we've got an army on the Rhine too," he murmured to himself, realising for the first time the extent of England's effort.

At the end of an hour he calculated that he was within two or three hundred of the door. He had only lately come out of hospital and was beginning to feel rather weak.

"I shall have to give it up," he said.

The Captain tried to encourage him with tales of gallantry. There was a Lieutenant in the Manchesters who had worked his way up on three occasions to within fifty of the door, at which point he had collapsed each time from exhaustion; whereupon two kindly policemen had carried him to the end of the queue again for air.... He was still sticking to it.

"I suppose there's no chance of being carried to the front of the queue?" said William hopefully.

"No," said the Captain firmly; "we should see to that."

"Then I shall have to go," said William. "See you to-morrow." And as he left his place the queue behind him surged forward an inch and took new courage.

A week later William suddenly remembered Jones. Jones had been in the War Office a long time. It was said of him that you could take him to any room in the building and he could find his way out into Whitehall in less than twenty minutes. But then he was no mere "temporary civil-servant." He had been the author of that famous W.O. letter referring to Chevrons for Cold Shoers which was responsible for the capture of Badajoz; he had issued the celebrated Army Council Instruction, "Commanding Officers are requested to replace the pivots," which had demobilised MARLBOROUGH's army so speedily; and, as is well known, HENRY V. had often said that without Jones—well, anyhow, he had been in the War Office a long time. And William knew him slightly.

So William sent up his card.

"I want to talk to somebody," he explained to Jones. "I can't manage more than of couple of hours a day in the queue just now, because I'm not very fit. If I could sit down somewhere and tell somebody all about myself, that's what I want. Any room in the building where there are no queues outside and two chairs inside. I'd be very much obliged to you."

"I'll give you a note to Briggs," said Jones promptly. "He's the fellow to get you out."

"Thanks awfully," said the overjoyed William.

A messenger girl took him and the note to Captain Briggs. Briggs listened to the story of William's qualifications—or rather disqualifications—and considered for a moment.

"Yes, we ought to get you out very quickly," he said.

"Good," said William. "Thanks awfully."

"Walters will tell you just what to do. He's a pal of mine. I'll give you a note to him."

So in another minute the overjoyed William was following a messenger girl to the room of Lieutenant Walters.

Walters was very cheerful. The thing to do, he said, was to go to Sanders. Sanders would get him out in half-an-hour. He'd give William a note, and then Sanders would do his best. The overjoyed William followed the messenger girl to Sanders.

"That's all right," said Sanders a few minutes later. "We can get you out at once on this. Do you know Briggs?"

"Briggs," said William, with a sudden sinking feeling.

"I'll give you a note to him. He knows all about it. He'll get you out at once."

"Thank you," said William faintly.

He put the note in his pocket and strode briskly out in search of the dear old queue.

"It will be quicker after all," he told himself, as he took his place at the end of the queue next to a Lieutenant in the Manchesters. ("Don't crowd him," said a policeman to William; "he wants air.")

And you think perhaps that the story ends here, with William in the queue again? Oh, no. William is a man of resource. The very next day he met another friend, who said, "Hallo, aren't you out yet?"

"Not yet," said William.

"My boy got out a month ago."

"H-h-h-how?" said William.

"Ah well, you see, he's going up to Cambridge. Complete his education and all the rest of it. They let 'em out at once on that."

"Ah!" said William thoughtfully.

William is thirty-eight, but he has taken the great decision. He is going up to Cambridge next term. He thinks it will be quicker. He no longer stands in the queue for two hours every day; he spends the time instead studying for his Little Go.

The larch-tree gives them needles

To stitch their gossamer things;

Carefully, cunningly toils the oak

To shape the cups of the fairy folk;

The sycamore gives them wings.

The lordly fir-tree rocks them

High on his swinging sails;

The hawthorn fashions their tiny spears,

The whispering alder charms their ears

With soft mysterious tales.

The chestnut decks their ball-room

With candles red and white,

While all the trees stand round about

With kind protecting arms held out

To guard them through the night.

Lord CURZON rises with the lark—

That is (at present) when it's dark—

Breakfasts in haste on tea and toast,

Then grapples with the early post,

And reads the newspapers, which shed

Denunciation on his head.

Having digested their vagaries

He calls his faithful secretaries

And keeps them writing, sheet on sheet,

Until he's due in Downing Street.

The Cabinet is seldom through

Until the clock is striking two,

When Ministers, dispersing, munch

Their frugal sandwiches for lunch.

Then back into affairs of State

Again they plunge from three till eight,

Presiding, guiding, interviewing,

Tea conscientiously eschewing,

Until exhausted nature cries

At half-past eight for more supplies.

Another hasty meal is snatched

And, when the viands are despatched,

Once more our admirable Crichton,

Though feeling like a weary Titan,

Resumes the toil of brain and pen

Till two is sounded by Big Ben.

The life of those whom duty spurs on

To lead laborious days, like CURZON,

Is not the life of BILLY MERSON

Or any gay inferior person.

The Selborne Society, which used to be a purely rural expeditionary force, has lately taken to exploring London, and personally-conducted tours have been arranged to University College in darkest Gower Street, where Sir PHILIP MAGNUS and Sir GREGORY FOSTER will act as guides, and to the Royal Courts of Justice, where Sir EDWARD MARSHALL HALL, K.C., "will describe the methods of conducting civil actions." What GILBERT WHITE would say to all this brick-and-mortar sophistication we do not dare to guess. All that we venture to do is to suggest one or two more urbane adventures.

Why, for example, should not a visit be paid to the House of Lords, under the direction of the new LORD CHANCELLOR? Five minutes spent on the Woolsack in such company not only would be a treasured memory, but a liberal (or, at any rate, a coalition) education. After such an experience all the Selbornians should come away better fitted to climb the ascents which life offers.

Again, if Sir HORACE MARSHALL, the Lord Mayor, invited the Society to the Mansion House they might be enormously benefited. Of turtle doves they naturally know all; GILBERT WHITE would have seen to that; but what do they know of turtle soup? Well, the LORD MAYOR would instruct them. He would show them the pools under the Mansion House where these creatures luxuriate while awaiting their doom; he would indicate the areas beneath the shell from some of which is extracted the calipash and from some the calipee; he might even induce the Most Worshipful Keeper of the Turtles, O.B.E., to discourse on the subject.

Then there is New Scotland Yard. It would be a scandal for the members of the Selborne Society not to visit that home of amity and see all the New Scots at work in tracking down the breakers of the laws that are made in the picturesque building with the clock tower so close by. And not very distant is the War Office, where mobilisation-while-you-wait may be studied at first hand, we don't think. Indeed, London offers such opportunities that we shall be surprised if the Selborne Society ever looks at a mole or a starling again.

Of course we know demobilisation is proceeding apace. We know that pivotal men are simply pirouetting to England in countless droves. We know it because we see it in the papers (when they come), and it is a great source of comfort to us. But since it is six days' train journey and four days' lorry-hopping from where we sit guarding the wrong side of the river to the necessary seaport, perhaps they have forgotten us, or they are keeping all the pivots in this area for one final orgy of demobilisation at some future date, which for the moment I am not at liberty to disclose.

At present my poor friend Cook is sitting in the Company Mess with his thoughts all of the inside of Army prisons, instead of the glowing pictures he used to have of himself exchanging his battle-bowler for the headgear of civilisation. He says I'm responsible for his state of mind, because I first put the idea into his head. Well, I did; but I don't see how you can blame the fellow who filled the shell if some silly ass hits it on the nose-cap with a hammer.

It started like this. After the Demobilisation General Post had sounded Cook spent his time writing to everybody who did not know him well enough to down his chances, filled up all the forms in triplicate and packed his valise ready to start off any time of the day or night for England, home and wholesale hardware, which is his particular pivot. I may say here that nominally this business is run by him and his brother, and the fact that they are now both in the Army is probably the chief reason why the manager in charge is able to make the business pay. However, you know what people are; if they draw receipts from a business nothing will persuade them but that they must be there, "on the spot you know," to "look after it." So, seeing his face grow longer and longer as the days went by without the Quarter-Master coming round and handing him his ration trilby hat, civvy suit and the swagger cane he hopes for, I said, "Why don't you put in for two months' business leave?"

The air was at once rent with a fearful rush of leaves of his A.B. 153, and he ceased to take any interest in his platoon from that moment. In vain I urged upon him the consummate folly of neglecting to inquire more closely into the case of a reprobate in No. 11 Platoon who had so far forgotten all sense of discipline as to set out his kit with haversack on the left instead of the right (or vice-versâ, I forget which, but the Sergeant-Major spotted it.). He even went the length of saying he didn't care a cuss; and when I asked him sarcastically if he had forgotten the Platoon Commander's pamphlet-bible, "Am I offensive enough?" he said he thought he was, and I agreed with him.

When the whole mess-room was simply a-flutter with torn-out leaves from his A.B. 153, representing his abortive attempts to put down his application succinctly and plausibly, we all began to take an interest in his case. We crowded round and offered him most valuable hints. Together we got through two very pleasant evenings and three or four A.B.'s 153, and still the application remained in a tentative state. We got on all right to start with, but it was after the "I have the honour to submit for the approval and recommendation of the Commanding Officer this my application for two months' business leave" that we got stuck.

Of course I know it was no use, anyway. I have seen these things go forward before. They have no chance.

It was then that a stroke of genius (unfortunate, as it turned out, but a stroke of genius nevertheless) occurred to me. "Why not say that your manager is a complete fool and in his hands the business is going to rack and ruin?" I said. He bit at it like a tiger, and only the law of libel prevented him putting it into execution there and then; [pg 77] but all the same we had a jolly fine argument (six of us) about it for some three hours, and nobody got put out of the room for introducing acrimony into the discussion.

Finally, he said that he was sure his brother wouldn't mind his saying it about him, and the application went in as follows:—

To Adjutant, First Crackshire Regt.

Sir,—I have the honour to submit for the approval and recommendation of the Commanding Officer this my application for two months' business leave in the following special circumstances:—

The necessity of my presence in the business (wholesale hardware) has become more and more urgent of late. It is imperative that I should get home at once owing to the total incapability of my partner to carry out simple directions which are dictated by letters, and it is no exaggeration to say that the business, which has been built up almost entirely by my efforts, must inevitably collapse unless it receives my personal attention at once.

My address would be, etc., etc., London.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient Servant, etc., etc.

The Adjutant looked serious when he read it. So did Cook, for he thought the Adjutant had noted the London address and had remembered the business was in Bristol. But it was all right. It wasn't that at all really. Pencil and squared paper are poor means of conveying information at any time, and when the Adjutant had been assured that the business was really "wholesale hardware," and not "wholesale hardbake," as he had first read it, everything went swimmingly. The C.O. signed it and off it went on its momentous journey. Cook began to take a renewed interest in his platoon, and, having discovered the recalcitrant one of No. 11 actually coming on parade with only the front of the tip of his bayonet-scabbard polished, he took a fiendish delight in seeing the criminal writhing under the brutal and savage sentence of three days' C.B.

A week later he got a great surprise. His brother-partner turned up with a draft of men and found himself posted to the battalion. The brothers met, as only brothers can, with the words, "What the deuce are you doing here?" Highly elated, Cook told him about the application for business leave and gloated over his chances of being home first, and on full pay too. His brother was intensely amused, and they both laughed heartily, when he told us that he himself, while waiting at the reception-camp with the draft, had put in much the same kind of application, saying the same kind of things about Cook.

But when they realised that both applications would be forwarded to the same Divisional Headquarters for consideration the joke lost some of its savour. And when the Adjutant called them up and handed the two returned applications pinned together both brothers needed all their qualities of toughness and rigidity which, as I understand, are acquired in the wholesale hardware business.

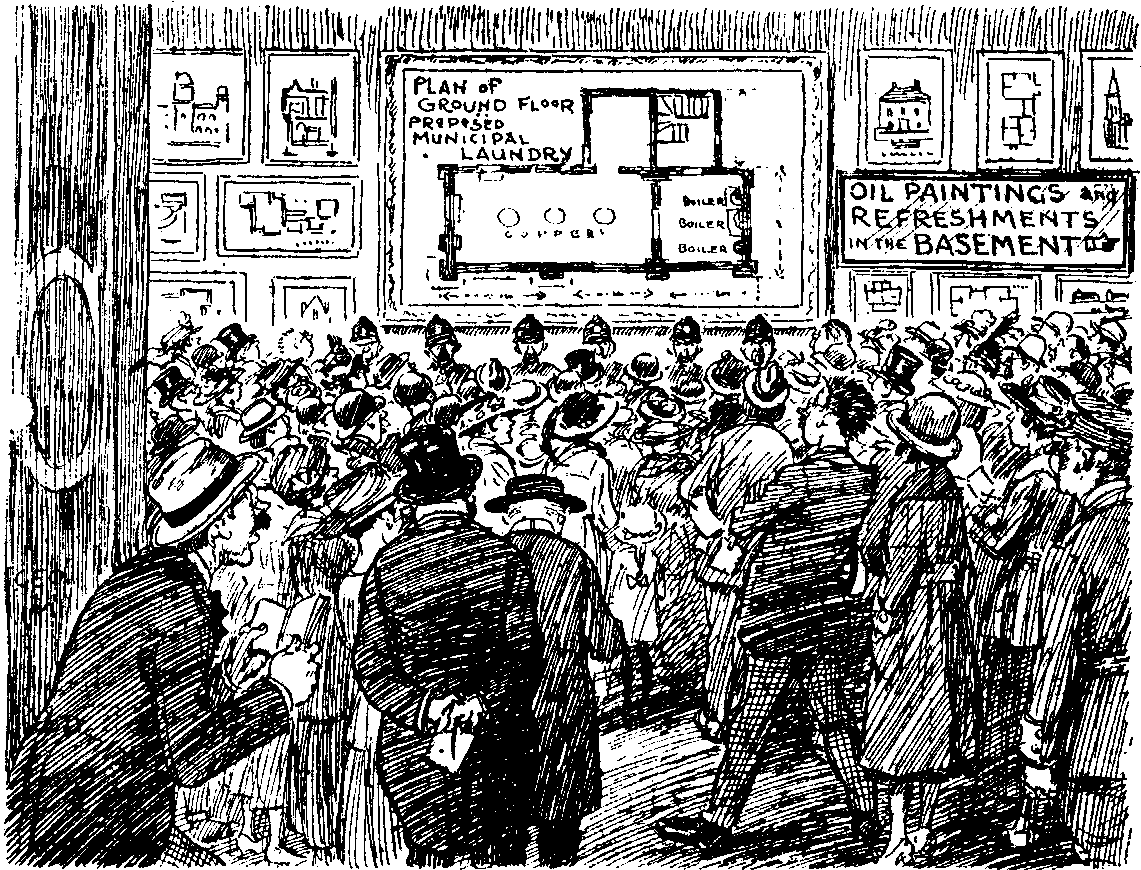

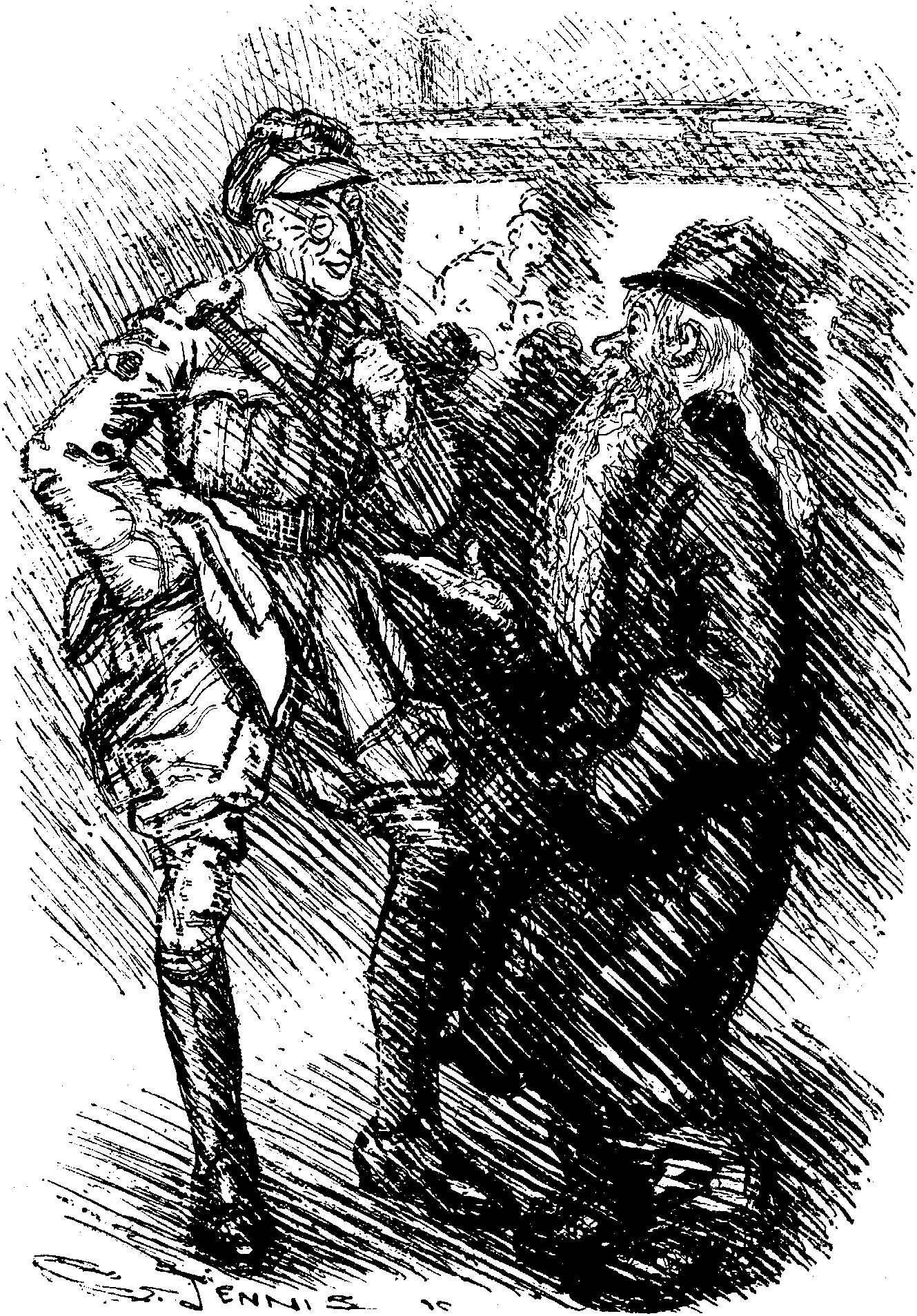

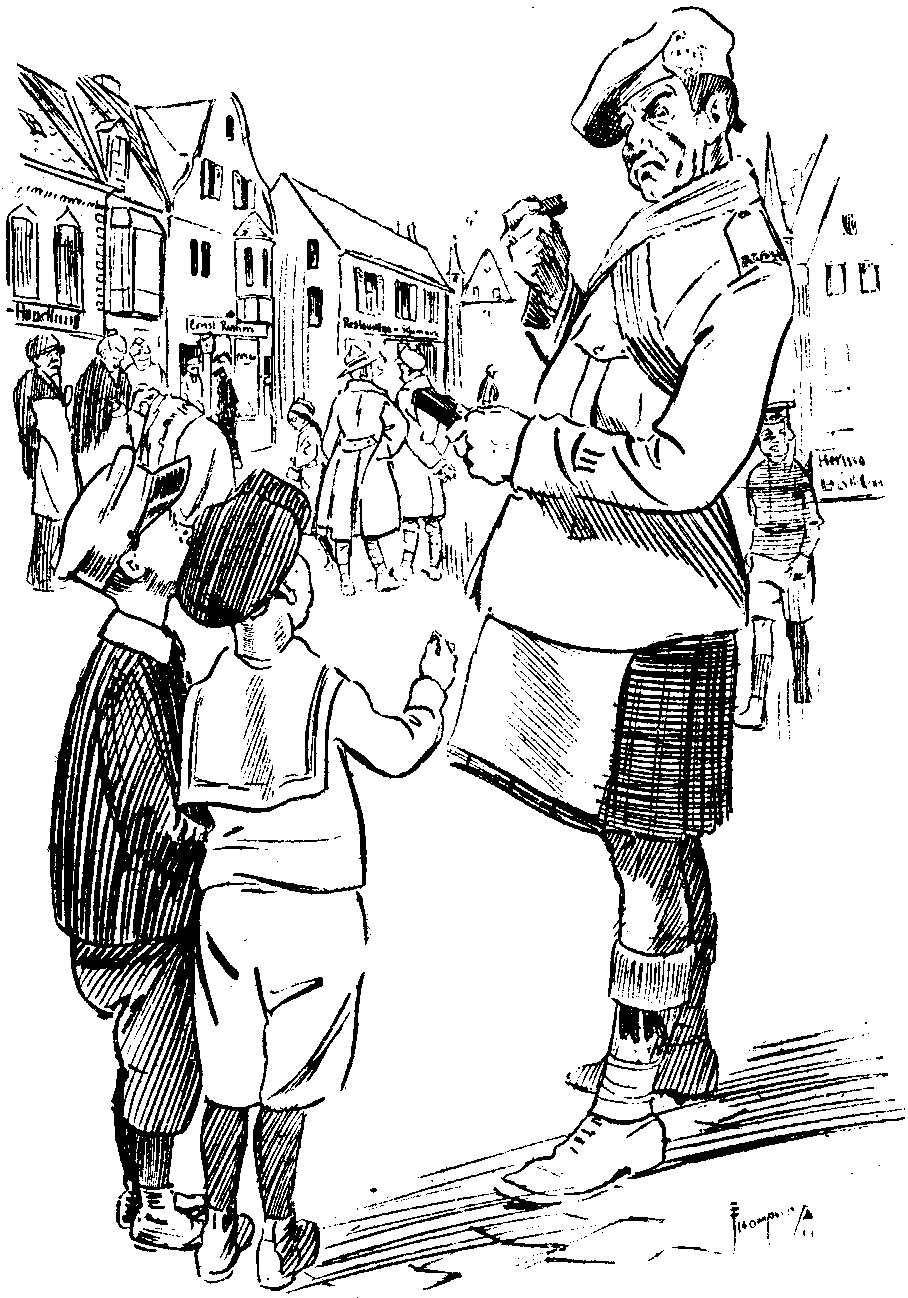

Shortsighted Traveller. "IS THERE SOME DELAY ON THE LINE, MY GOOD MAN?"

Naval Officer. "WHO THE —— DO YOU THINK I AM, SIR?"

Traveller. "ER—N-NOT THE VICAR, ANYWAY."

"Oak bedstead, 3 ft. 6 in., with wife and Wool Mattress, new condition, £5 10s. 0d. lot."—Provincial Paper,

"One Parsel Furnishing goods curtains, cushion covers, etc., Rs. 26; one bundle babies, Rs. 5.—Apply Mrs. ——."—Ceylon Independent.

"Temporary Cook wants Hampshire."—Morning Post.

Really quite moderate. Some cooks nowadays seem to want the whole earth.

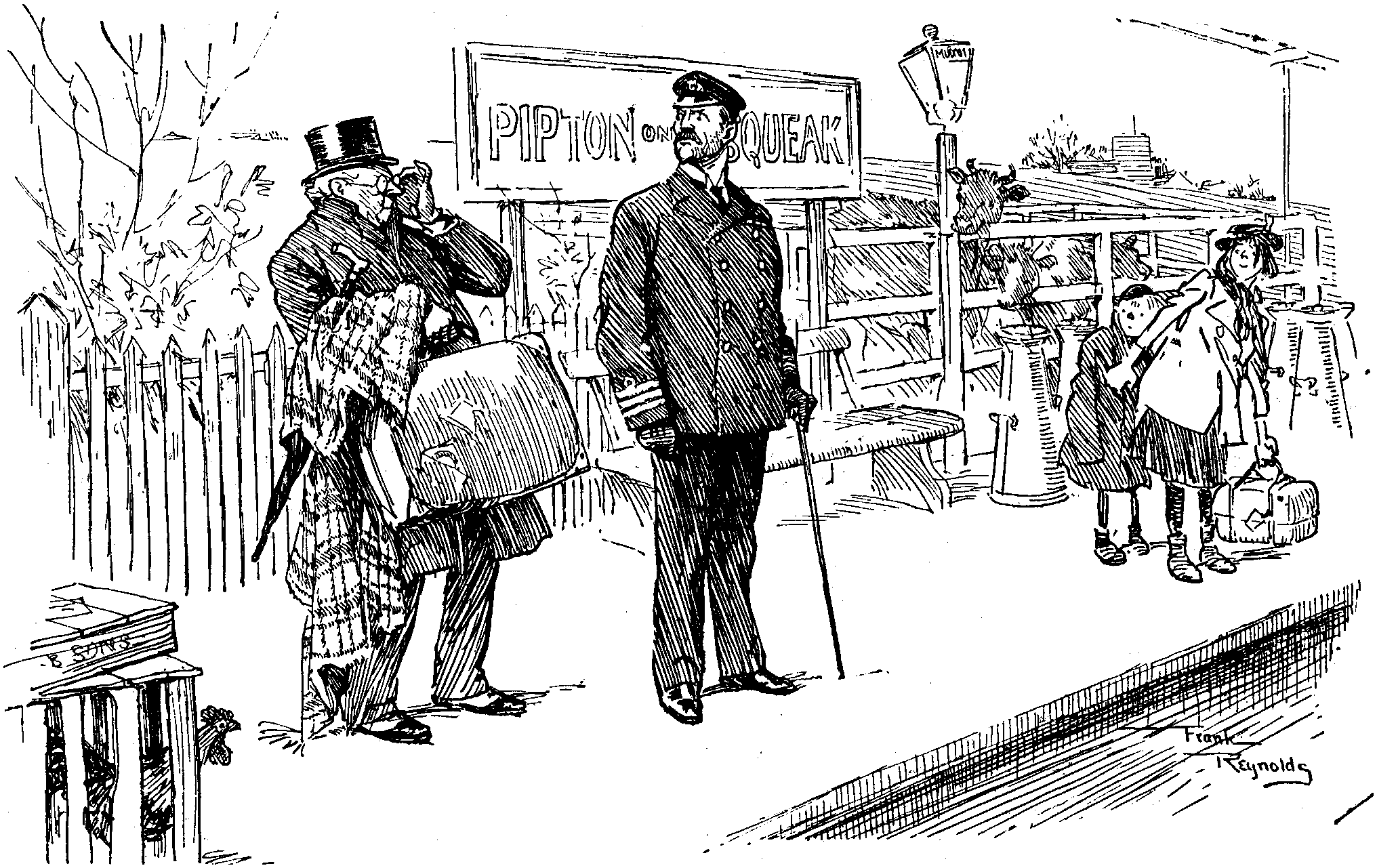

Adjutant (who has been interrupted in his real work by a summons from Colonel). "YES, SIR?"

Temporary Colonel. "I SAY—ER—SMITH—IT'S SO UNCERTAIN HOW LONG WE SHALL BE OUT HERE—DEMOBILISATION, YOU KNOW. ER—FACT IS—DO YOU THINK IT WORTH MY WHILE GETTING ANOTHER PAIR OF BREECHES?"

When yesterday I went to see my friends—

(Watching their patient faces in a row,

I want to give each boy a D.S.O.)—

When yesterday I went to see my friends,

With cigarettes and foolish odds and ends

(Knowing they understand how well I know

That nothing I may do can make amends,

But that I must not grieve or tell them so),

A pale-faced Inniskilling, tall and slim,

Who'd fought two years and now was just eighteen,

Smiled up and showed, with eyes a little dim,

How someone left him, where his leg had been,

On the humped bandage that replaced the limb,

A tiny green glass pig to comfort him.

These are the men who've learned to laugh at pain,

And if their lips have quivered when they spoke

They've said brave things or tried to make a joke;

Said it's not worse than trenches in the rain,

Or pools of water on a chalky plain,

Or bitter cold from which you stiffly woke,

Or deep wet mud that left you hardly sane,

Or the tense wait for "Fritz's master stroke."

You seldom hear them talk of their "bad luck,"

And suffering has not spoiled their ready wit,

And oh! you'd hardly doubt their fighting pluck,

When each new operation shows their grit;

Who never brag of blows for England struck,

But only yearn to "get about a bit."

"The Allies had threatened to destroy the Dardanelles if the Medina garrison did not surrender."—Birmingham Mail.

So, being reduced to its last Straits, the garrison surrendered.

"MATRIMONY—Young Lady (21), good prospects, wishes to correspond with young man, similar age, with a view to above; no rebels need apply."—Irish Paper.

But we guess there will be one Home Ruler in the family.

"Replying to a query concerning the rumour that Messrs. Guinness were in treaty for the purchase of the National hell Factory, Parkgate Street, a representative of that firm said this afternoon: 'We have no statement to make at all.'"—Irish Paper.

We gather that the printer is a Prohibitionist.

"At Doncaster on Saturday, Messrs. —— sold for £7,100 the fully licensed house at Armthorpe known as the Plough Inn to the Markham Main Colliery Company, the proprietors of the colliery being sunk in the parish."—Yorkshire Post.

Not spurlos versenkt, we trust. Perhaps it is hoped that the Plough will unearth them.

Here is a simple method of aiding the admirable efforts of educational Staff-Officers in the army.

Let all Regimental Orders be interspersed with items of information likely to be of use in civilian life. Thus:—

53. ... will be rendered to this office, in triplicate, by noon to-morrow.

53A. Etiquette, Points of. It is not considered correct to address an Archbishop as "Archie" unless one is on terms of considerable intimacy with him. In writing to a Duchess never commit the vulgar error of putting a stamp on the envelope; the sixth footman in a ducal household is always provided with a fund in respect of unpaid postage on incoming correspondence.

54. ... is placed out of bounds to all troops on account of an outbreak of mumps.

54A. Data, Geographical.—Of all fish those of the Bay of Biscay are perhaps the best nourished. An isthmus is a piece of land which saves another piece of land from being an island. The principal exports of Germany are prisoners of war.

55. ... to be read on three consecutive parades.

55A. Theory, Untenable, Literary.—The The theory that BACON was a pork-butcher and derived inspiration for Hamlet by gazing at the viands in his shop has now been disproved.

56. ... and a sum of twopence per haircut will be chargeable against public funds.

56A. Courts, Foreign.—The Sultan of Socotra is entitled to a salute of fourteen popguns and one catapult. Before approaching the throne of the Duke of the Djibouti one is required to take lessons from the Court Contortionist.

57. ... and Company Commanders are reminded of their responsibility in this matter.

57A. World, the Animal.—It is interesting to know that the inventor of the Tank first planned that engine of warfare while watching the peregrinations of the armadillo at a travelling menagerie. The efficacy of our blockade was such that large consignments of armadillo-fodder were prevented from reaching Germany, the consequent demise of all German-kept armadilloes thus robbing our enemy of the opportunity of devising a similar instrument.

58. ... will parade in full marching order at Reveille.

58A. Facts, Historical.—There once was a king who never smiled again, but history might have recorded a different verdict had His Majesty witnessed the spectacle of the Second-in-Command, on a frisky horse, trying to drill the Battalion.

59. ... will therefore immediately submit rolls of all skilled organ-blowers of Category B ii.

59A. Information, General.—If all the Treasury Notes circulated in the United Kingdom since 1914 were placed end to end they might reach from Bristol to Yokohama and back, but they would not constitute a sufficient inducement to a London taxi-driver.

60. ... and this practice must cease forthwith.

60A. Query, Our Daily.—What is Popocatapetl? Is it an indoor game, a cannibal tribe, a curative herb, or neither? Solutions are invited.

There are two very advantageous points about this scheme: (1) The ingenious system of numbering would avoid interference with army routine, which must go on: and (2) men might be encouraged to read Regimental Orders.

This suggestion is made without hope of fee or reward. Its author does not even ask for extra duty pay.

Tramp. "CAN YOU SPARE A PORE OLD GENTLEMAN THE PRICE OF A CUP OF KORFEE. SIR?"

Sub. (in high spirits). "RIGHT-O. ALL THE COFFEE YOU WANT AND THE PRICE OF A SHAVE AND A HAIR-CUT AS WELL."

Tramp. "WILL YER? THEN WHO'S A-GOIN' TO KEEP ME WHILE MY 'AIR AN' BEARD GROWS AGAIN?".

"I wish 'as 'ow I warn't married."

Mr. Punt crooned out the impious aspiration as he sorted a judicious modicum of hemp into the canary seed. He spoke in semi-soliloquy, yet quite loud enough to reach the vigilant ear of Mrs. Punt, who was dusting the cages at the other end of the live-stock store. She said nothing in reply, but her eye fixed itself upon him with a glint eloquent of what she might say later.

"Why is that, Mr. Punt?" I asked encouragingly.

"Why, it's on'y to-day, Sir, as I met a lidy, a widder lidy, friend o' Uncle George's down Putney way, as 'as one leg, a nice little bit o' 'ouse property and two great hauk's eggs."

It did seem a rare combination of marriageable qualities. I asked the value of a great auk's egg, and was surprised to learn that a specimen had recently been sold at auction for something like three hundred pounds. I inquired whether all the great auks' eggs that came on the market were genuine, or whether "faked" specimens were to be met with. I had heard, I thought, of "faked" eagles' eggs.

"Different kind o' bird altogether, Sir, and different kind o' egg. Can't very well be imitated. You didn't think as I said great 'awk, Sir?" he asked very anxiously.

"No, no; I understand," I hastened to assure him.

"The 'awk, Sir, is a bird o' the heagle kind; the hauk's a different kind altogether—web-footed, aquatic—was, I should rather say, seeing as 'ow 'e's un appily extinct. Hauk and 'awk, Sir—you take the difference?"

I said that I thought the distinction was perceptible to a fine ear for the aspirate.

The phrase took the little man's fancy wonderfully. "That's it, Sir," he exclaimed, beaming up delightedly at me. "You've 'it it! Done it in one, you 'ave. 'Fine ear for the haspirate'—that's what my darter Maria 'ave and what I, for one, 'ave not. I'm not above confessing of it; 'tain't given to all of us to 'ave everything, as the ant said to the helephant when 'e was boasting about 'is trunk. Some there is as ain't got no ear for music—same as Joe Mangles, the grocer down the street, as 'as caught a heavy cold in 'is 'ead with taking 'is 'at off every time as 'e 'ears 'It's a long long way to Tipperary.' Why, I've knowed men," said Mr. Punt, in the manner of one who works himself up to an almost incredible climax—"I've knowed men as couldn't tell the difference between a linnet's note and a goldfinch."

"Astonishing," I said.

One of the canaries suddenly broke into a rich trill of song, as if to add his personal expression of surprise.

"Now there!" Mr. Punt exclaimed, shaking a podgy forefinger at him. "There's the bird as give all the trouble and cause words 'tween me and Maria, 'e did. 'Artz Mountain roller, that bird is. Beeutiful 'is note, ain't it, Sir?"

There really was a deep full tone, distantly suggestive of a nightingale's, that favourably distinguished the bird's song from the canary's usual acute treble.

"'I'm doubting, Maria,' I say to 'er," Mr. Punt resumed. "No longer ago than this very morning I say it—'I'm doubting whether I did ought to call that 'ere bird a 'Artz Mountain roller,' I say to 'er—me meaning, o' course, as the 'Artz Mountains being, as some thinks, in Germany, that pussons wouldn't so much as go to look at a canary as called 'isself a 'Artz Mountain bird, as it might be a German bird, for all as 'e'd never a-bin no nearer Germany than the Royal Road, Chelsea, not never since 'e chip 'is little shell, 'e 'aven't.

"So I ask 'er the question, doubting like, and she up and say, all saucy as a jay-bird, 'Why, certainly you didn't ought to call 'im so,' she say.

"'Question is, Maria,' I says, 'in that case what did I ought to call 'im?'

"'And I can tell yer that too, Dad,' she say—Maria did. 'You didn't ought to call 'im 'Artz Mountain roller, but ha-Hartz Mountain roller. That's the way to call 'im,' she says—impident little 'ussy! But there—what's in a name, as the white blackbird said when 'e sat on a wooden milestone eating a red blackberry? Still, 'e weren't running a live-stock emporium, I expect, when 'e ask such a question as that 'ere. There's a good deal in 'ow you call a bird, or a dawg or a guinea-pig neither, if you want to pass 'im on to a customer in a honest way o' trade."

I assured Mr. Punt I had not a doubt of it.

"But I shall be a-practisin' my haitches, Sir," he promised me, as I went out with the canary seed which I had called to purchase—"practise 'em 'ard, I shall. It's what I ain't a-got at the present moment—'a fine ear for the haspirate.' Beeutiful expression that, Sir, if you'll excuse me sayin' so. But I don't see no reason as a man mightn't 'ope to acquire it, 'im practising constant and careful—same as a pusson can learn a bullfinch to pipe ''Ome, sweet 'Ome.' That haitch is a funny letter, but it's a letter as I shall practise. Still, haitches or no haitches," he concluded, with a profound sigh, "I wish as I knowed 'ow I could set about coming it over that 'ere one-legged widder lidy at Putney what 'ave the two great hauk's eggs."

Out of the dusty twilight in the far end of the shop Mrs. Punt's eye gleamed balefully.

I went into a tobacco-shop, tendered a pound note and asked for a packet of cigarettes and a box of matches. With much regret and a smiling face, she informed me she had the goods but no change.

What a dilemma! A shop with cigarettes and matches, but I couldn't spare a pound note for them.

An inspiration!—I would go into the hairdressing establishment behind the shop, have a shave—which I really didn't need—obtain change and make my purchase. Besides, with so many barbers closed owing to the strike, it was an opportunity.

This is what happened.

"Good morning, Sir. Your turn next but six."

A long, long interval.

"Shave, Sir? Lovely weather we're having. Razor all right, Sir?"

I said as little as possible; it is the only safe thing.

"Face massage, Sir?"

"No, thanks," I mumbled.

"Wonderful thing for the face, Sir; make a new man of you. Invigorates the circulation, improves the complexion—"

"Oh, all right," I gasped.

And then for about twenty minutes snatches of conversation floated to me through bundles of wet towels. My head was having a Turkish bath. My face was covered with ointments and creams. Currents of electricity played about my brow.

"Just trim your hair, Sir?"

I swear I said "No," but before I knew what was happening the scissors were running merrily over my head.

"Singeing, Sir?"

"Er—no. I—"

"Finest thing in the world, Sir. It's a treat to see hair like this. Just a bit 'endy,' but singeing will soon put that right."

Even had I been blind I should have discovered that I was undergoing the process.

"What would you like for the shampoo, Sir? Eau de Quinine—Violet—"

"I don't think—"

My feeble protest was cut short.

[pg 81]"I always recommend Violet," he said, sprinkling my head profusely.

More rubbing, more towels, more electricity and finally a brush and comb.

"I've a hair-lotion here, Sir—"

"No, thank you."

I meant it.

He helped me on with my coat, brushed off a deal of imaginary dust, said something about skin softeners and bath requisites, but I'd had enough for one morning, and I was yearning to get those cigarettes and have a smoke.

I tendered my pound note.

He took it, and with his best smile said—

"Another sixpence, Sir, please."

There are many things Dora kept dark

That she's now letting into the light,

And to-day an astounding aerial barque

Has suddenly sailed into sight;

But its past makes no sympathies burn,

And its future leaves interest limp,

Compared with the rapture I feel when I learn

That its name is the Blimp.

Who gave it its title, and why?

Was it old EDWARD LEAR from the grave?

Since Jumblies in Blimps would be certain to fly

When for air they abandon the wave.

Was it dear LEWIS CARROLL, perhaps

Sent his phantom to christen the barque,

Since a Blimp is the obvious vessel for chaps

When hunting a snark?

And to-day, in the first-fruits of joy,

I scarcely believe it is true

That Blimp is a word we shall one day employ

As lightly as now Bakerloo;

And my reason refuses to jump

To the fact that a man, not an imp,

Can flash through the other and land with a bump

From a trip in a Blimp.

"It needs no very profound knowledge of the politics of South-Western Europe to surmise that neither Rumania nor Greece would lend military assistance of this kind without being promised something in return.—Manchester Guardian.

But a rather more profound knowledge of the geography might be useful.

It is late in the day to draw attention to Mr. Punch as a prophet. Everyone knows that his eyes have always discerned the farthest horizon. None the less it is pleasant now and again to succumb to the temptation of saying "I told you so," and especially when it is the finger of a friendly reader that points the way to the Sage's triumph. Were we in the habit of quoting from past numbers, as many of our contemporaries do, we should print the following paragraph from the issue of September 2nd, 1871:—

"'According to Le Havre, about forty Prussian officers in mufti leave Dieppe every morning for England, their object being to visit the military establishments of Great Britain.'

"Here at last is an actual invasion! Prussian officers landing on our defenceless shores, on the transparently flimsy pretext of making themselves acquainted with our military establishments, at the rate (excluding Sundays) of 240 a week, or in this present September, of 1,080 a month, or, amazing and terrifying total, of 12,520 a year! We commend this startling announcement to the attention of the Cabinet (Parliament, unfortunately, is not sitting), the Commander-in-Chief, the War Office, the Commanders of all Volunteer Corps, the Author of 'The Battle of Dorking,' Sergeant Blower, and Cheeks the Marine."

Tommy

(homeward bound, and determined not to

disappoint). "WHY, MISSY, THREE DAYS BEFORE THE

ARMISTICE THE AIR WAS THAT THICK WITH AEROPLANES THE

BIRDS HAD TO GET DOWN AND WALK."

Tommy

(homeward bound, and determined not to

disappoint). "WHY, MISSY, THREE DAYS BEFORE THE

ARMISTICE THE AIR WAS THAT THICK WITH AEROPLANES THE

BIRDS HAD TO GET DOWN AND WALK."

[To any English composer who has not yet contributed to the wave of music and dance which is now sweeping the country the writer offers the following as the basis of an entirely new and original dance, strictly national in character and full of that quaint old rustic, not to say aboriginal, grace which distinguishes modern dance-music.]

Oh say, won't you stay down-away at the Sausage Farm?

It's a scream, it wouldn't seem you could dream such perfect ch-e-arm;

You can bet that Jazz'll be beat to a frazzle,

And the old Fox Trot'll be a pale green mottle,

When they gauge what's the rage of the age at the Sausage Farm.

(CRASH! BANG! TINKLE!)

Come along, you'll be wrong if you miss that Sausage Roll.

Every pig does the jig, for he's in this heart and so-ul:

See the old sow shout, "What about my litter?"

But she dries those tears when she hears, poor crittur,

That they're all at the Ball in the Soss-Soss-Sausage Roll.

(TZING! BOOM! The lights go out.)

Oh, haste, life's a waste till you're based at the Sausage Farm,

Where the dog and the hog and the frog go arm-in-arm;

And the farm-yard bosses can all do Sosses;

The old man's crazy, and his poor Aunt Maisie,

Over this hit of bliss (have a kiss) at Sausage Farm.

(CLATTER! BUMP! The walls begin to crack.)

Come a-quick, you'll be sick if you miss that Sausage Roll,

For the cow does it now and the cat we can't contro-ol,

And I heard as she purred, "Oh, I've found my kittens,

You could bet they'd get with the best-born Britons,

For they're all at the Ball in the Soss-Soss-Sausage Roll."

(CRASH! BANG! The roof falls in.)

"SHANGHAI MUNICIPAL COUNCIL POLICE FORCE.—Police recruits are now required. Applicants must be unmarried, of good physique, with sound teeth, about 20 to 25 years of age, not less than 57 ft. 10 in. in height."—Weekly Paper.

"Lloyd's agent at Chriseiansund telegraphs that wreckage marked 'Wilson Line' drifted ashore near Switzerland."—Provincial Paper.

Following the WILSON line the seas appear to be already behaving with unusual freedom.

"'George Eliot' (Mary Ann Evans), the gifted Warwickshire authoress, who wrote 'Adam Bede' and several other popular works."—Daily Telegraph.

We have noticed the name from time to time, and we are glad to know who "GEORGE ELIOT" was.

From a "multiple shop" catalogue:—

"SMOKING ROOM.—The decorations are well worth a special note, and are quite unique of their kind, being without a match anywhere."

Surely not "unique." We know a lot of smoking-rooms equally matchless.

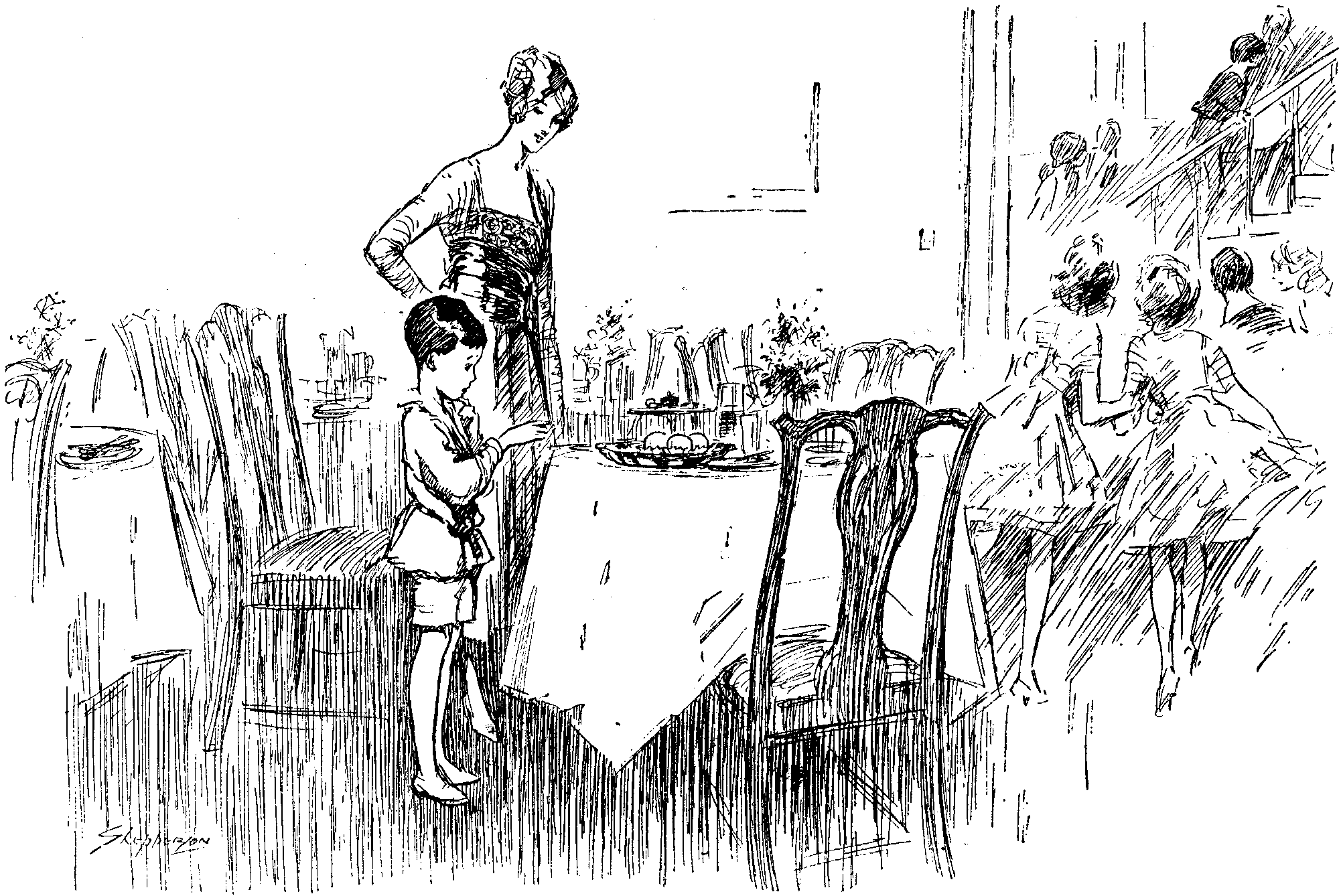

Hostess (to small guest, who is casting lingering glances at the cakes). "I DON'T THINK YOU CAN EAT ANY MORE OF THOSE CAKES, CAN YOU, JOHN?"

John. "NO, I DON'T THINK I CAN. BUT MAY I STROKE THEM?"

An evening newspaper informs its readers that arrangements are being made for "a school for M.P.'s"—"a weekly meeting of Unionist M.P.'s new to Parliamentary life, who will receive instruction in the forms of the House. They will be taught how to address the SPEAKER, how to frame a question," and so forth.

This intelligence is of particular interest in that it conveys an admission that our new M.P.'s do not know everything.

Interviewed by a correspondent, Mr. Raleigh Quawe, the able young educationist, who, it is understood, is watching the experiment with some concern, said, "While I do not wish to seem to be giving away too much to the gloom of youth, I cannot help feeling that the school may be run on wrong lines unless the greatest care is exercised. Will the opportunity be taken for testing methods which have been so disastrously absent hitherto from our public school system? I would urge those in authority to put away the old formulæ, and to ensure the introduction of a right spirit in the school by the appointment of young masters endowed with vision and enthusiasm.

"I hope that the worship of sport will not be encouraged. I was never one who believed that our battles have been won on the playing-fields of Westminster. I am confident that I am not alone in the hope that the old games at Westminster will be abandoned.

"It is most important that there should be no suppression of the emotional nature. Rob politics of emotion and the newspapers are not worth reading; and it must not be forgotten that what Westminster does to-day is read of by the British Empire to-morrow. No effort should be spared to awaken the artistic sense of the pupils. If the pictures and sculptures in and about the corridors of the Houses of Parliament are not enough, let others be prepared. No expense should be spared. For my part I see no reason why a little music should not be introduced occasionally.

"Freedom of opinion should also be encouraged. One fault of our educational system has been its tendency to produce mass-thinking. This will never do among our Unionist Members of Parliament. Yes, I would even advocate that some of the seniors should be allowed to read The Herald if they wished to do so, and I question whether The Nation would do any of them any harm."

Notice in a watchmaker's window:—

"No repairs except to watches recently purchased."

Advertisement in Provincial Paper:—

"WALK IN,

But you will be happier when you go out."

"An extraordinary plague of rats prevails on the Sheffield Corporation rubbish tips at Killamarsh. The rodents have constructed beaten tracks eight inches wide, extending to corn stacks on a local farm, where they have wrought munch havoc."—Local Paper.

Quite the right epithet, we feel sure.

"We make a speciality of gorillas and chimpanzees. They are wonderfully intelligent and can be trained right up to the human standard in all except speech. One of our directors, Mr. ——, and his wife are both able to only be tamed to live in captivity."—Irish Paper.

A perusal of the above paragraph is said to have stimulated Mr. ——'s gift of speech in a startling degree.

One day last week, it might be Wed-

nesday, or even Friday,

A day not yet entirely dead,

A shortly-doomed-to-die day,

The Naiad who lay stretched in dream

Awoke and gave a shiver—

The Naiad who has charge of stream

And rivulet and river.

I had intended to write the whole of this article in verse, of which the above is a shocking sample, but, on the whole, I think I will go on in prose. When you have committed yourself to double rhymes, prose is the easier medium. In verse it is more difficult to stick to your subject, and as the subject in this case is a very important one and deserves to be stuck to, I shall do the rest in prose.

Anyhow, the fact is that I have read a paragraph in one of the papers about a proposed revival of rowing. Rowing, like other sports, has, it seems, lain dormant for the past four years and a half. From the moment in 1914 when war was declared it suffered a land-change; shorts and zephyr and blazer and sweater were abandoned at once, and, for the oarsman as for everybody else, khaki became the only wear. Already trained by long discipline to obey, our oarsmen trooped to the colours, and wherever hard fighting was to be done their shining names are to be found on the muster-roll of fame. Some will return to us, but for others there waited the eternum exitium cymbæ—a very different craft from those to which they were accustomed, but they accepted it with pride and without a murmur.

Bearing these things in mind, I went to Henley last week to interview Father Thames. I found the veteran totally unchanged in his quarters on the Temple Island, and immediately began the interview.

"Dull?" he said. "I believe you, my boy. But they tell me there's talk of reviving the regatta. You tell them with my compliments not to be in too great a hurry about it. Think of what Henley meant to the lads who rowed. They hadn't learnt their skill in a day—no, nor in as many days as go to a year."

"Do you then," I said, "consider the regatta only from the oarsman's point of view?"

"Really," said the old gentleman, "there's no other. Not but what," he added with a chuckle, "it gave them more pleasure to row their races with lots of pretty faces to look on. Lor' bless you, I don't object to 'em. It's the prettiest scene in the world when the sun shines as it sometimes does. And that's enough talking for one afternoon." With that he plunged, and nothing I did could bring him to the surface again.

Bound South from Japan to the port of Hong Kong

We fell in with a little junk blowing along;

We met her all bright at the breaking of day,

And we gave her good-morning and passed on our way.

She had stretched her red sails like the wings of a bat,

And light, like a gull, on the water she sat;

She had two big bright eyes for to keep a look-out;

On her stern there were dragons cavorting about.

And Mrs. Ah Fit by the kitchen did sit

Preparing some breakfast for Mr. Ah Fit,

The gentleman who, as we saw when we neared her,

By waggling the tickle-stick skilfully, steered her.

The little Fit men and the little Fit maids

Were playing at tig round the brass carronades,

And with all the delight of a juvenile Briton

The littlest Ah Fitlet was plucking the kitten.

With a "How do you do, Sir?" and "Hip, hip, hooray!"

'Twas so they blew by at the breaking of day.

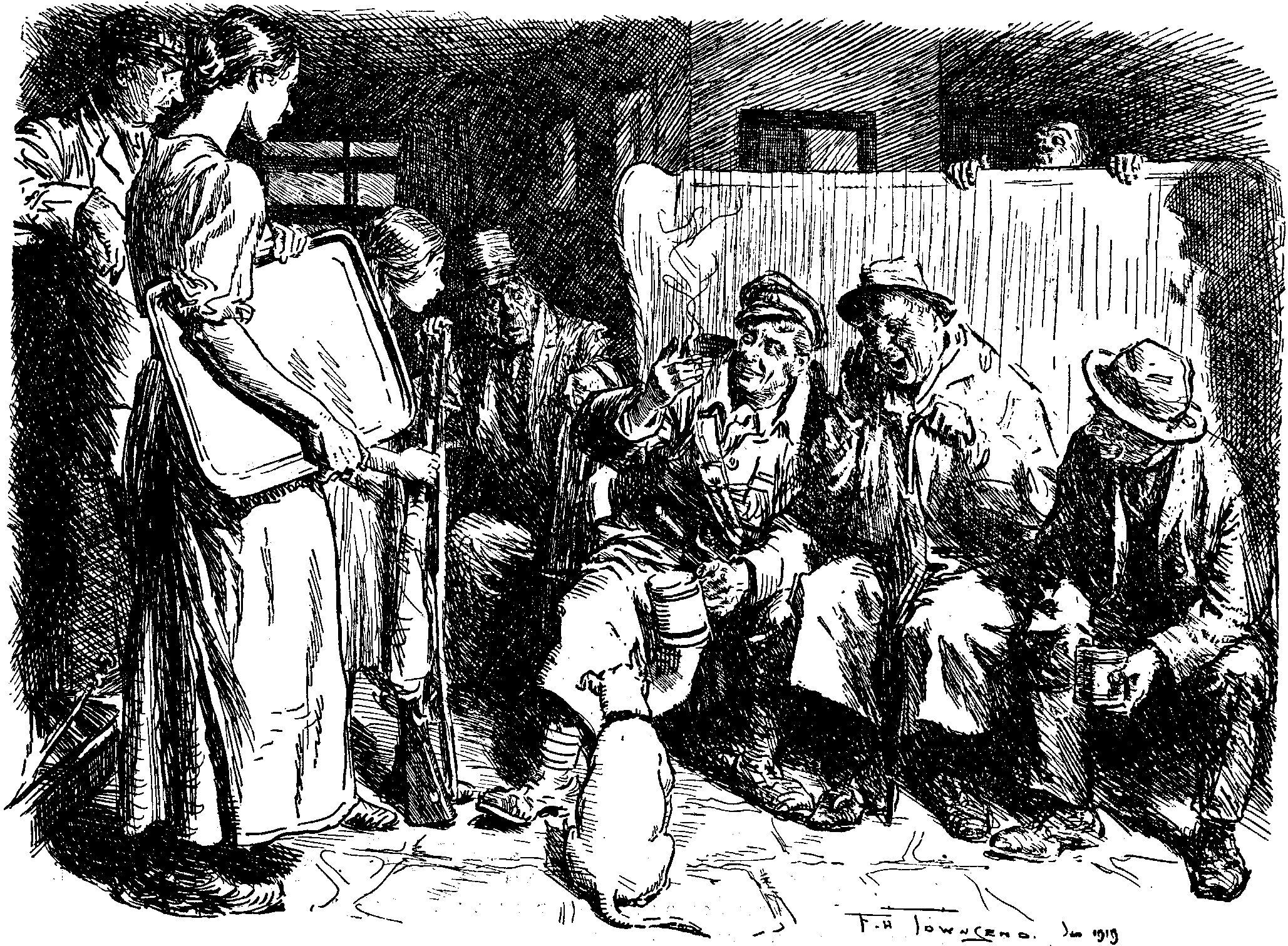

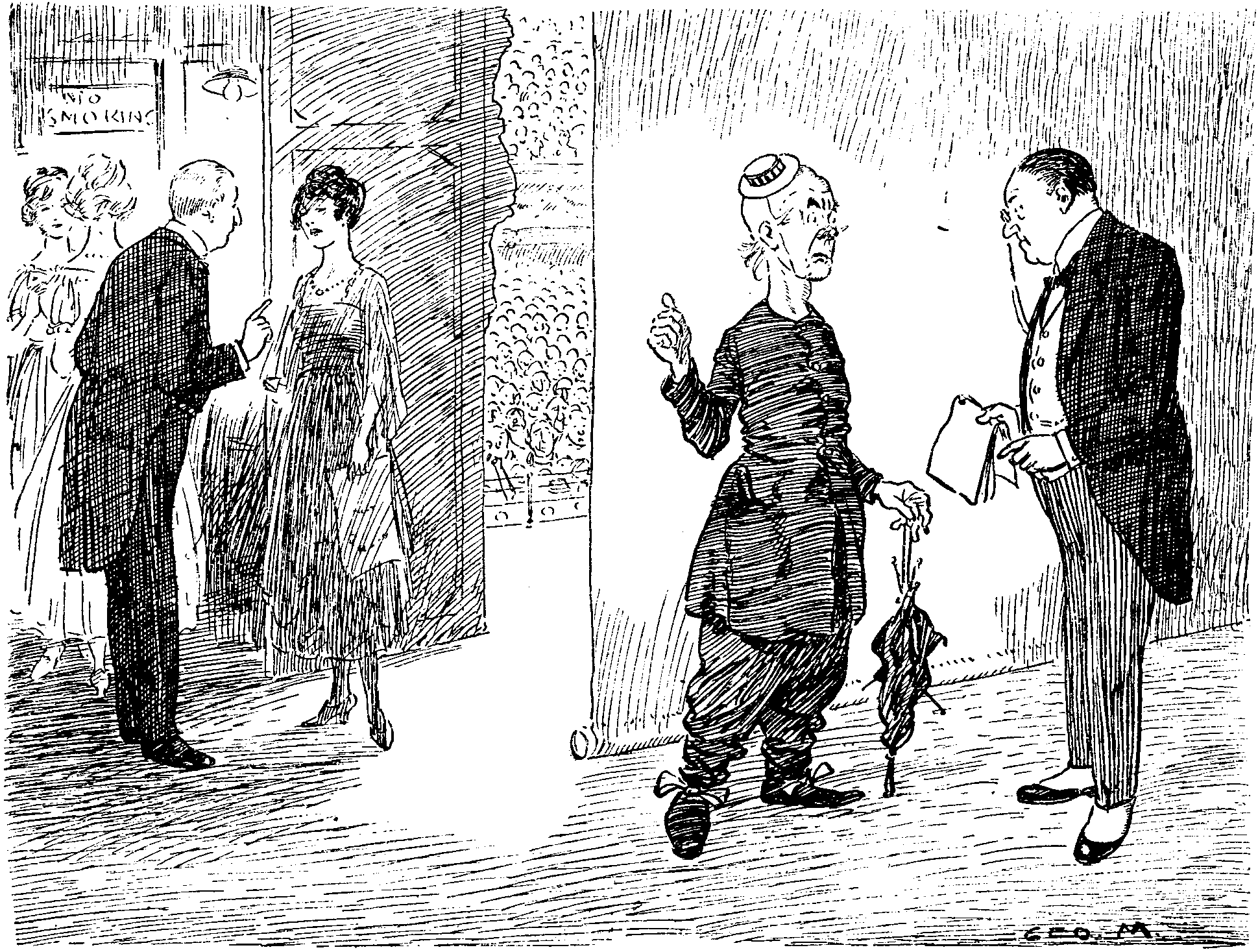

Comedian (who has been

instructed to modify his humour to suit the taste of a

select audience at a charity performance at the local

theatre). "THERE YOU ARE! NOT A LAUGH! THIS IS WOT

COMES OF YOUR 'FUNNY WITHOUT BEIN' VULGAR'!"

Comedian (who has been

instructed to modify his humour to suit the taste of a

select audience at a charity performance at the local

theatre). "THERE YOU ARE! NOT A LAUGH! THIS IS WOT

COMES OF YOUR 'FUNNY WITHOUT BEIN' VULGAR'!"

"Not a bad possie," said George, looking round the village. "Let's rustle a bivvie before the crowd comes along."

All George's performances in the art of rustling bivvies rank as star. He permits no coarse and obvious gathering of an expectant horde about the opening door; no slacking of straps and bootlaces until the final "I will" is said on either side. He debouches in extended order on the doomed house; gets his range and has the barrage well in hand (the quantity and quality of Madame's gesticulations furnish the key to this) before Colin drifts off the horizon and shows a peaked face with haunting eyes over George's shoulder. Colin does not speak. That is not his métier. He is the star shell illuminating the position; and usually in about six minutes' time it is safe for John to put in an appearance with the kit.

This is the recognised procedure, and it has served us indifferently well up and down three years of war and a good deal of France and Flanders. Therefore John was not to blame when, after waiting the scheduled six minutes, he arrived to find the other two still in the thick of it. Either Colin was not haunting up to form (which was likely, as he had been over-fed lately) or George's French (which was never made in the place where they make marriages) had scandalised Madame.

She stood in the door like some historical personage, probably the Sphinx, and repeated a guttural kind of incantation while George stretched his ears until they stood out more than usual in a struggle to understand.

"Rotten patois some of these people speak," he said. "I believe she has a room, though something's biting her. Likely enough Fritz went off with all her furniture; but I've already explained twenty times that that doesn't matter. Écoutez, Madame. We only want a room. Chambre-à-coucher. We can furnish it. We have three beds. Trois lits. Trois stretcher-beds sent over from Angleterre. À la gare. We've just seen them. Trois lits nous avons. Three beds."

"Beds!" Madame pounced on the word. "C'est cela! No beds, Monsieur. Je n'en ai pas."

"Ah, now we know where we are." George looked round triumphantly. "Écoutez, Madame. We don't want beds. Nous les desirons jamais. We have them. Trois lits. We don't want them. We have beds. Comprenez?"

"No beds," explained Madame firmly.

"But I've just told you—" George plunged again into the maelstrom, and a pretty girl appeared from the firelit room behind to stir him to his highest flights of eloquence. A smell of savoury cooking came also, and out in the street night shut down dark and chill and sinister, as it does in all the best novels. John let part of the kit down on the door-sill. It was his way of explaining that at the present moment there was a deeper, more intimate call than the Call of the Wild. Colin moved up a step and turned the haunting-stop full on. George redoubled his efforts, making them very clear indeed. We could understand almost every word he said.

Then Madame answered, and we could understand that too.

[pg 88]"No beds," she said.

The pretty girl smiled in a troubled way and murmured something in a soft voice.

"She says they haven't got any beds in the rooms. Fritz took them all," interpreted George. "Écoutez, Mademoiselle. We have beds. Trois lits. Nous les avons. Tous les trois. Oui. À la gare. Absolument."

Mademoiselle looked at Madame with a kink of her pretty brows. Madame rose like a balloon to the need.

"No beds," she said very distinctly, with a rounding of eyes and mouth. "No beds, Messieurs. No-o-o—beds."

Before George could recover John interfered. He makes a hobby of cutting Gordian knots.

"Oh, what's the earthly use of telling 'em we have beds when they can see for themselves that we haven't? They just think we can't understand. Let's go up and take the rooms if they're decent. Then we'll get the stretchers and put 'em up. That's the only sort of argument we can handle."

Manfully George went to work again. And reluctant, and yet obviously fascinated by his French, like a bird by a snake, Mademoiselle led up the narrow stairs and into a sizeable room, clean as a pin and as naked. On the threshold Madame washed her hands of hope.

"Regardez! No beds. C'est affreux!"

George began again. He had courage. Whatever else Nature and luck denied him there was no question of that. For a little it looked as though he were in sight of the goal. Then Mademoiselle explained. They were désolées, but the sales Boches had stolen all the beds, and Madame would not let the bare rooms to Messieurs les Anglais. It would not be convenable when they had no beds.

"No beds!" Madame appealed to the skylight as witness, and we looked at each other. It was getting late and the others would have rustled all the best bivvies by now. John had another brain-wave.

"Let's pantomime it. They always understand pantomime. There's no use saying we've got beds—not when George has to say it. We'll show them."

Earnestly we pantomimed stretcher beds—our own stretcher beds—and reposeful slumber thereon. "Mon Dieu!" cried Mademoiselle, retreating in haste. "No beds," repeated Madame, unconvinced and unafraid.

"She means that she doesn't want to have us," said John in cold despair.

"She'd be a fool if she did now," answered Colin grimly. "Let's get out of this."

And then John had a third brain-wave. He ordered George on guard, and descended with Colin in search of the concrete proof of our sanity. And Madame's voice, faint yet pursuing, followed us down.

"No beds," it said.

In ten minutes we were back triumphant with the three stretchers. It was a full six months since we had written to England for them, and they had come at last. Visions of rest went upstairs with us, and under the big eyes of Madame and Mademoiselle and several more Madames who had collected as unobtrusively as a silk hat collects dust we slashed at the coverings, ripped them off and disclosed—three deck-chairs.

We did not attempt to meet the situation. We left it to the devil—or Madame. And she, with the lofty serenity of one who through long and grievous misunderstanding has won home at last, was completely adequate.

"No beds," she said.

"ADOPTION.—Fine healthy boy, 3½ years; entire surrender to good home. reception. 5 bedrooms; £1,100."—Provincial Paper.

What an exacting young rascal!

"Liebknecht was the son of a father who opposed tyranny in earlier days, who sounded the toxin for liberty."—Express and Star (Wolverhampton).

But, to do old LIEBKNECHT justice, it was the son, not the father, who spelt it that way.

I expected, of course, when I declared the resolution, "Dogs not Doormats," open for general discussion that there would be some pretty plain barking, but nothing calling for the intervention of the Chair. Britain's dogs are sound at heart, even if they do talk a bit wildly about the Tyranny of Man and Rabbitism and Abolishing the Biscuiteer. I don't agree with a lot of it myself—we Airedales have always been conservatively inclined; but I am bound to say that three years in the Army open one's eyes to a lot of things.

Nothing of a really seditious character was said until the Borzoi commenced to address the meeting. I had always disliked the fellow and half suspected him of being an Anarchist or the president of some brotherhood or other. (It's funny how these rascals, whose one idea is to get something which belongs to somebody else without working for it, always call themselves a brotherhood.) But those Russian dogs have such a shifty slinking way with them that you can't always tell what they are driving at. This Borzoi chap had tried once or twice to interest me in what he called the Community of Bones doctrine, but I soon found out that his master was a conscientious objector and a vegetarian and that the doctrine really meant that he would do the communing and I would provide the bones.

The rogue began with some fulsome ingratiating remarks about how pleased he was to see so many fine representatives of the canine race prepared to maintain intact their sovereign doghood whatever the sacrifice might entail. This brought loud applause from the young hotheads; but I noticed traces of disgust along the backs of the older dogs. The time had passed, he continued, for speeches and resolutions and votes of censure. Dogs must act if Man, the enemy, was to be finally crushed. I intervened at this point and told the Borzoi he must moderate his language, upon which he began to bluster, shouting that he would not be put down by an arrogant hireling of effete Militarism. One learns to practise self-control in the trenches, so I was able to repress an inclination to [pg 89] assert my authority then and there. It was no use striking at man himself, he went on, for he had guns and whips and stones at his command. We must strike at him through his children.

Cries of dissent greeted this statement, and I really think the matter would have ended then and there only it so happened that none of those present were personally interested in children, except old Betty the bulldog, who belongs to four little girls who treat her sovereign doghood in a most disrespectful way. But old Betty had gone to sleep, and, anyway, she is rather deaf and has no teeth, so it's likely she would have confined herself to a formal snuffle of protest. "Yes," shouted the Borzoi, now thoroughly worked up, "let every dog take a solemn oath to bite every child on every possible occasion—at least when no one is looking—and Man, the oppressor, will soon come begging for mercy and make peace with us on our own terms. No false loyalty or ridiculous sense of chivalry must withhold us," he continued. "The baby in the pram to-day is the man with the whip of to-morrow and must be bitten with all the righteous fury of outraged doghood." Cries of "Shame!" greeted this remark. I decided that it was time to interpose. With all the severity at my command I bade the wretch be silent.

"Fellow dogs," I said, "it is clear that we must choose here and now, once and for all, between Britishism and Bolshevism. Tails up those who wish to remain British!" And of course every tail went up. "Tails up, the Bolshevists!" But the Borzoi's was down beyond recall and shivering between his legs. "That being your decision, ladies and gentlemen," I continued, "the meeting will constitute itself a Committee of Safety. Remarks have been passed about your Chairman and the canine forces of His Majesty that cannot be allowed to go unchallenged. All I ask is plenty of room and no favour."

All this time the Borzoi had been edging towards the door, and I really think he would have tried to make a dash for it, only at the last minute he caught the eye of the Irish wolfhound. It's no good running away from a dog like that, so Bolshy decided to stay and face the music. Well, as I said before, we war dogs are supposed to be as modest as we are brave, so I will confine myself to saying that down our way Bolshevism hasn't a leg to stand on. Of course Master, when he saw my ear, pretended to be angry, but he knows a war dog doesn't fight except for his country, and when the Borzoi's owner came round next day to complain Master told him he was a miserable Pacifist and had no locus standi. I told Master afterwards that the Borzoi had no loci standi either, because I'd jolly well nearly chewed them off; and he laughed and gave me a whole cutlet with a lot of delicious meat on it, saying he wasn't hungry himself.

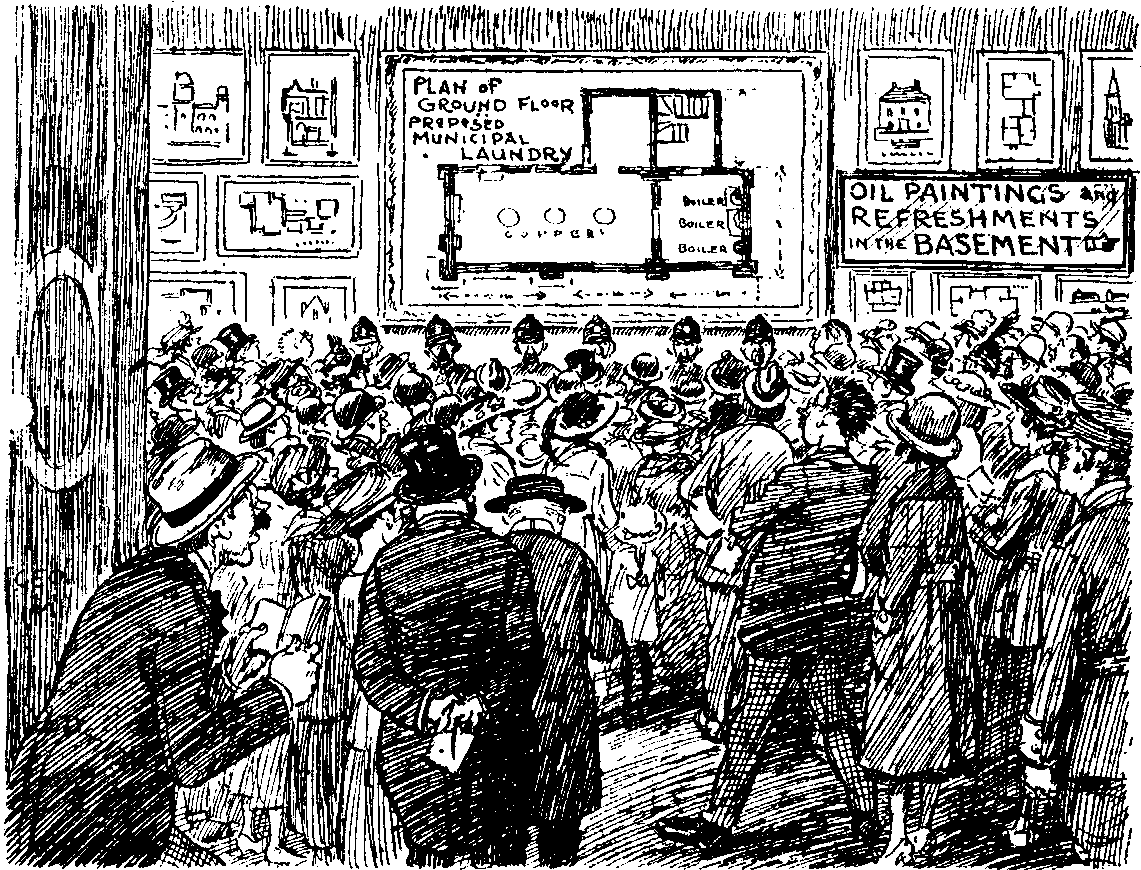

Of course we dogs met again and adopted the rest of our platform; and I don't mind saying I kept a pretty tight grip on the proceedings. In fact, several resolutions, such as those dealing with "Municipal Dog's-meat," "Rabbits in Regent's Park," "The Prosecution of Untruthful Parlourmaids," "Shorter Fur and Longer Legs," were carried without discussion. Naturally the meetings concluded with a vote of thanks to the Chair, to which I replied (they tell me) felicitously.

That is how the War Dogs' Party came into being; and to-morrow I shall tell that little terrier fellow from No. 10, Downing Street, that as long as his master remains faithful to the Dog-in-the-Street the War Dogs' Party will remain faithful to him.

"'The little lass, and what worlds away,' one says to oneself on coming out of Mr. Rosing's recital."—"Times'" Musical Critic.

It's the worst of music that it makes one so love-sick and sentimental.

"As," says one of Mr. Punch's many and very welcome correspondents, "you will probably be writing for the benefit of your readers a short handbook on how to be demobilised, I enclose for your guidance my solicitor's bill. He was engaged from November 12th until I returned home on leave on December 30th and took a hand in the game myself. The chief work was tracing the various Government Departments to their hidden lairs in which they indulge in the pleasing habit of exchanging minutes.

"Some day perhaps demobilisation will reach me. The sooner the better, for I can never settle this account on my Army pay."

So much for the preamble. Here, with the alteration only of certain names, is the document itself. Mr. Jones, it should be mentioned, is a member of the firm to which the Officer in question (whom we will call Mr. Lute) wishes to return:—

| 1918. | £ | s. | d. | |

| Nov. 12. | Attending Mr. Jones on calling on the telephone as to Mr. Lute and advising him to make an application | 6 | 8 | |

| " 27. | Attending Demobilisation Office, Whitehall Gardens, when the place was too crowded to be seen to-day. Engaged nearly two hours. | 13 | 4 | |

| Writing Mr. Lute I was putting through application. | 3 | 6 | ||

| " 28. | Attending New Bridge Street when I interviewed Official and he handed me pivotal form after explaining circumstances | 18 | 4 | |

| " 29. | Attending Mr. Jones on calling when Mrs. Lute was present, filling in form after discussing same. Engaged 3 to 3.50. | 10 | 0 | |

| Copy to keep | 1 | 0 | ||

| " 30. | Attending New Bridge Street, interviewing Official, and he referred Mr. Lute's case to Mr. Bedford Smith, 105a, Portman Square, Head Food Department for your district | 13 | 4 | |

| Dec. 2. | Attending Portman Square, interviewing Official, when he said I had got the wrong form and requested me to go to Whitehall Gardens and ask them about it. | |||

| Attending Demobilisation Office at Whitehall Gardens, interviewing Official when he wanted to know how I had got the form as I had no business to have it as the issue of them had been stopped, and I said it had been given to me, and he was unable to say what should be done with it, but in any event another form ought to be filled up, R.C.V., and he handed me such form. Engaged 10.30 to 1; 2 to 3.45 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| Dec. 3. | Attending Portman Square office, when I said that I had been to the office at Whitehall Gardens and they wanted to know how I had got the pivotal form, but he took it in and said he would refer it to the local committee at once, and he gave me the name of the head man there and suggested we might push it if we went to him, and he had nothing to do with the R.C.V. form. | 13 | 4 | |

| Attending Whitehall Gardens asking what they wanted done with R.C.V. form and they said if it was sent in there filled up it would receive attention in its turn. | 10 | 0 | ||

| Writing Mr. Jones to get in touch with Local Authority. | 3 | 6 | ||

| " 5. | Attending Mr. Jones on telephone as to getting into touch with local representative, which he would do at once | 3 | 4 | |

| " 6. | Filling up same and writing them therewith | 5 | 0 | |

| " 11. | Attending Mr. Jones on telephone when he said Committee had recommended application last Friday evening | 3 | 4 | |

| " 12. | Attending Portman Square, interviewing Official and they had not received recommendation of local committee | 13 | 4 | |

| " 13. | Attending Mr. Jones, informing him thereof on telephone giving me reference No. and he would send on copy letter to him by local committee recommending application | 3 | 4 | |

| " 16. | Attending Portman Square when they had not heard from local committee, handing them copy of their letter and they would act on that | 13 | 4 | |

| " 18. | Writing Mr. Jones as to further form, sent in to him to sign | 3 | 6 | |

| " 19. | Attending Portman Square when application had gone forward | 13 | 4 | |

| Telephoning to Mrs. Lute to that effect. Like Mr. Jones. | 3 | 4 | ||

| " 20. | Writing Mr. Lute as to the matter | 3 | 6 | |

| " 23. | Attending Portman Square Official when application was on way to War Office and they said you would be demobilised shortly | 13 | 4 | |

| " 31. | Attending Mr. Lute, showing me correspondence and requesting me to see Demobilisation Department, Broad Street. | |||

| 1919 | ||||

| Jan. 2. | Attending Broad Street when they had removed to Hotel Windsor and obtaining two forms to fill up to extend your leave while your case went through if necessary and they knew nothing about your case | 13 | 4 | |

| Attending at your office getting Secretary to sign form. | 10 | 0 | ||

| " 4. | Attending Windsor Hotel when department disbanded and had gone to Lancaster Gate | 13 | 4 | |

| Attending you reporting on telephone | 3 | 4 | ||

| " 6. | Fare and expenses | 15 | 0 | |

| —— | — | — | ||

| Total | £14 | 5 | 0 |

Let meaner souls make merry

O'er cups of ruby wine,

With claret, port or sherry

Their tunes incarnadine;

Let little boys emphatic

Become o'er ginger b.

Myself I grow ecstatic

About a drink called "Tea."

Tea elevates one's pecker,

Rejuvenates the mind,

Enriches the exchequer,

Yet never makes men "blind";

When footsore and effete I'm

From every ache set free,

And not alone at tea-time

I thank the Lord for "Tea."

It tells of balmy breezes

That blow "o'er Ceylon's isle"

(While HEBER mostly pleases

His accent here is vile)—

Of some far-flung plantation

Where Hindus bend the knee;

And would my occupation

Were prefixed (ah!) by "Tea"!

'Tis told in classic fable

The nectar served to Zeus

At his Olympic table

Was just a vinous juice;

That such is purely fiction

I heartily agree,

Having the sound conviction

'Twas nothing less than "Tea."

The Conference will be held in the imposing Salle de la Grande Horloge. The 'hall of the great clock' is about 30in. long by 15in. wide."—Liverpool Echo.

"Imposing," indeed.

"Manchester's £6,000,000 scheme for obtaining water supplies from Haweswater was approved last night at a meeting of ratepayers in the Town Hall. The annual increased consumption of water had been a little over a million gallons per head per day."—Daily Dispatch.

The new slogan of the temperance enthusiasts—What Manchester drinks to-day England will drink to-morrow.

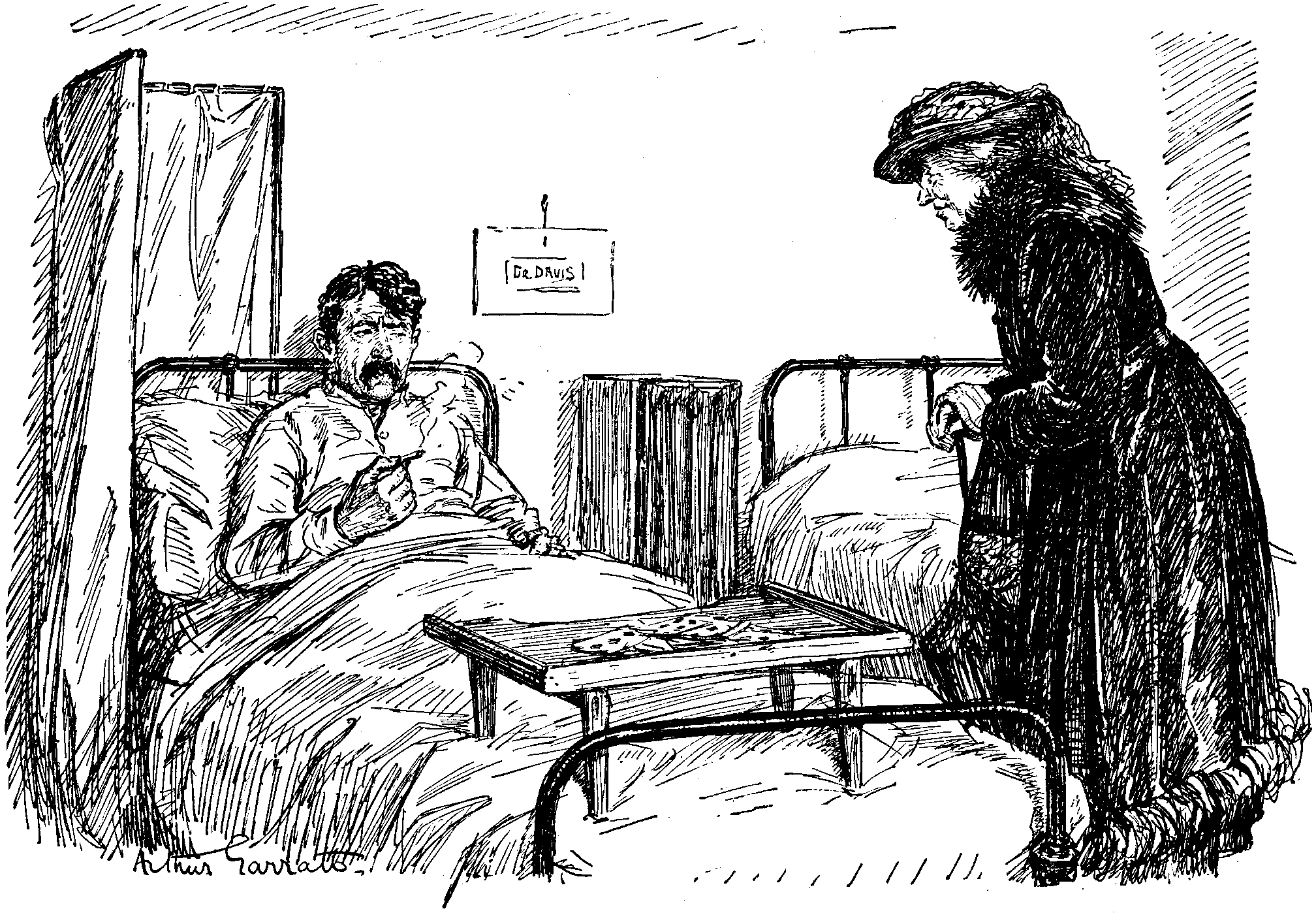

Visitor. "BUT THOSE ATTACKS OF MALARIA DON'T LAST LONG, DO THEY?"

Tommy. "MINE ISN'T ORDINARY MALARIA. THE DOCTOR CALLS IT 'MALINGERING MALARIA.'"

I own that to find the publishers, those sometimes too generous critics, writing upon the wrapper of An English Family (HUTCHINSON) an appreciation that bracketed it with The Newcomes, did little to predispose me in its favour. Later, however, when I had read the book with an increasing pleasure, I was ready to admit that the comparison was by no means wholly unjustified. Certainly Mr. HAROLD BEGBIE has written a very charming story in this history of the Frothinghams and the growth of their typically English characters, maturing just in time for the ordeal that has tested and (one is proud to think) triumphantly approved the spirit of our country. In fact these memoirs of Hugh Frothingham are something more than an idle romance; there is an allegory in them, and some touch of propaganda, cunningly introduced in the fine character of Torrance, the great surgeon who married one of the Frothingham girls and was bombed in the hospital raids. Through the varied activities of the family, as they develop, passes the cleverly-shown figure of Hugh, the narrator, who, starting with fairer prospects than any of the others, is ruined by indolence and an income, and hardly saved by the War from degenerating into the torpid existence of a social pussy-cat. Hugh is an admirable example of the difficult art of seemingly unconscious self-revelation. Altogether I have found An English Family greatly to my taste, displaying as it does a dignity and breadth that recall not unworthily the best traditions of the English novel. But did we speak of Serbia in 1914? I only ask.

High Adventure (CONSTABLE) is in certain ways the most fascinating account of flying and of fliers which has come my way. Captain NORMAN HALL, already well known to readers of Kitchener's Mob, tells us in this later book how he became a member of the Escadrille Américaine and how he learned to fly. And, as his modesty is beyond all praise, I feel sure that he will forgive me for saying that it is not the personal note which is here so specially attractive. What makes his book so different from other books on flying is that in it we have a novice suffering from all sorts of mishaps and mistakes before he has mastered the difficulties of his art. Whether consciously or not Captain HALL performs a very great service in describing the life of a flier while his wings are—so to speak—only in the sprouting stage. In an introduction Major GROS tells us of the work done by American pilots before America entered the War, a delightful preface to a book which both for its matter and style is good to read.

I confess at once that The Uprooters (STANLEY PAUL) is a story that I have found hard to understand. There seems an idea somewhere, but it constantly eluded me. To begin with, exactly who or what were the Uprooters, and what did they uproot? At first I thought the answer was going to name Major and Mrs. Elton, who for no very sufficient reason would go meddling off to Paris, and transporting thence the brother and sister Ormsby to Ireland. The Ormsbys had been happy and (apparently) harmless enough hitherto, but once uprooted they promptly developed the most unfortunate passions—reciprocated, moreover—for their well-wishers. The obvious and laudable moral of [pg 92] which is, never remove your neighbour from his chosen landmarks. Later, however, it became apparent that Mr. J.A.T. LLOYD had a more subtle interpretation for his title in the activities of a band of pacifists, headed by a multi-millionaire, who called himself an American, though somehow his name, Schwartz, hardly inspired me with any feelings of real confidence. On his death-bed, however, this gentleman reveals blood of the most Prussian blue, confessing that his wealth has actually been derived from the dividends of Frau BERTHA; and as the War has by this time resolved the emotional difficulties of the other characters the story comes to its somewhat procrastinated finish. My own belief in it had to endure two tests, of which the less was inflicted by a scene specifically placed in a "dim second class carriage" on the L.&N.W.R. in 1916; and the greater by the cri de coeur of the lady, whose husband surprised her with her lover: "Edmund, get that murderous look out of your eyes, the look of that dreadful ancestor in the portrait gallery!" I ask you, does that carry conviction under the circumstances?

Really, the delight of the publishers over Cecily and the Wide World (HURST AND BLACKETT) is almost touching. On the outside of the wrapper they call it "charming," and are at the further pains to advise me to "read first the turnover of cover," where I find them letting themselves go in such terms as "true life," "sincerity," "charm" (again), "courage," and the like. The natural result of all which was that I approached the story prepared for the stickiest of American cloy-fiction. I was most pleasantly disappointed. Miss ELIZABETH F. CORBETT has chosen a theme inevitably a little sentimental, but her treatment of it is throughout of a brisk and tonic sanity, altogether different from—well, you know the sort of stuff I have in mind. Cecily was the discontented wife of Avery Fairchild, a young doctor with three children and a fair practice. After a while her discontent so increased that she betook herself to the wide, wide world, to live her own life. And as both she and Avery before long fell cheerfully in love with other persons I suppose the move could so far be counted a success. Before, however, the divorce facilities of the land of freedom could bring the tale to one happy ending an accident to Cecily's motor and the long arm that delivered her to her husband's professional care brought it to another. I am left wondering how this dénouement would have been affected if Avery had been, say, a dentist, or of any other calling than the one that so obviously loaded the dice in his favour. I repeat, however, a distinctly well-written and human story, almost startlingly topical too in one place, where Dr. Avery observes, "There's a lot of grippe in town, and it's a thing that isn't reported to the Health Department." The obvious inference being that it ought to be. Avery, you observe, had more practical sense than the majority of heroes, few of whom would ever have thought of this, or, at any rate, mentioned it.

Baroness ORCZY's romance of old Cambrai, Flower o' the Lily (HODDER AND STOUGHTON), should not be regarded as in any way bearing upon the more modern history of that remarkable city. It has nothing to do with our war; it has a war of its own, a rapid affair of bows and arrows, scaling ladders and such desperate situations as can be, and were, saved by the arrival of the right man, single-handed, in the right place at the right moment. Familiar as is his type in novels of this adventurous kind, I think I shall never tire of the consummate swordsman hero who impersonates, for political and matrimonial ends, a man of infinitely higher degree but far less real worth than himself, handling the vicarious business with an incredible adroitness, but mistakenly carrying by storm the love of the lady for himself. The lady is so confoundedly attractive in these circumstances, possibly because there is about them a tonic which lends additional colour to the feminine cheek and a new brilliance to the eye. And, however bitter may be the first moment when the true personalities are divulged, it all comes right in the end. Here is a story of intrigue and battle and love, written in the necessary phraseology of the time and woven round (and, I trust, consistent with) the historical contest between the Spanish and French Powers, disputing the terrain of Flanders; in every way a worthy successor of The Scarlet Pimpernel. It is inevitable to suggest that this story should also be dramatised in due course; it would make as a play an instant and irresistible appeal to that great public which loves the theatre most when it is most theatrical. And it is doubtless destined also for the Movies.

SCENE.—Cologne—Present

Day.

SCENE.—Cologne—Present

Day."Few people realise the difficulty senior officers in the Navy who are married and have children have in making both ends meet. Naval officers who entered over fifteen years ago did not, as a rule, come from the married classes."—Sunday Paper.

"Whilst waiting to be bathed, an old blind female inmate of the —— Institution fell to the floor, breaking her thigh. Her injury has accentuated her death from bronchitis."—Birmingham Post.

With a grave accent, we fear.

"The war broke Germany's hold on world's wild animal trade, the New York Zoological Society chairman states. Zoos and circuses are now turning to British dealers to fill their cages."—Evening Paper.

Provided that the above paragraph has made the British dealers sufficiently wild.