*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 76394 ***

Footnotes have been renumbered sequentially and collected

at the end of the text. They are linked for ease of reference.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

THE LOVE OF AN UNCROWNED QUEEN

SOPHIE DOROTHEA.

From a painting formerly at Ahlden.

THE LOVE OF AN

UNCROWNED QUEEN

SOPHIE DOROTHEA, CONSORT OF

GEORGE I., and her Correspondence with

Philip Christopher Count Königsmarck (Now

first published from the originals)

BY

W. H. WILKINS

M.A. (Clare College, Cambridge), F.S.A.

Author of “Caroline the Illustrious, Queen Consort of George II.”

NEW AND REVISED EDITION

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK AND BOMBAY

1903

v

PREFACE TO THE REVISED EDITION.

When this book was first published in April, 1900,

I had no idea that it contained any of the elements

of popularity. The subject which it treats

had been of interest with me for years, and my

researches were made from love of the work. In

my quest I followed as closely as possible the footsteps

of Sophie Dorothea during her life. I visited

Celle where she was born, Hanover where she

lived during her unhappy marriage, and Ahlden

where for more than thirty years she was imprisoned.

To Hanover I went again and again,

and in connection with this book I also visited

Berlin and Dresden. But it was not until six

years ago, in 1897, that I lighted by chance (while

turning over old volumes in a second-hand bookshop

at Leipzig) upon the fact that an unpublished

correspondence between Sophie Dorothea and

Königsmarck existed. For a long time I could

not find where these letters were deposited, and

went in vain search to Upsala, but at last I learned

that they were reposing in the library of the little

university of Lund in Sweden. To Lund accordingly

I went, and with the permission of the university

authorities carefully examined the manuscripts.

The result of my investigations is described

at length in the chapter on “The History and

viAuthenticity of the Letters”. It was the finding

of these letters which determined me to write this

book; it is built up around them.

Even when the book was written I published

it with misgiving, thinking it would have little

interest for any except the few who love the

untrodden paths and byeways of history. But,

contrary to expectation, the book attracted a good

deal of attention both in England and America.

In France and Germany too it called forth comment,

and in a short time several editions were

exhausted, until at last it ran out of print.

By that time I had learned something from

my critics, more especially from those in Germany,

and I determined not to issue another edition, until

I had the opportunity of testing what I had written

in the light of further historical research. I was

then working at another book, Caroline the Illustrious,

Queen Consort of George II., which also treats

of the Hanoverian period, at a little later date,

and until that book was finished, I had not the

leisure to follow up fresh clues in connection with

this one. Hence the publication of this revised

edition has been delayed, for the book has been out

of print some little time.

Another consideration has also weighed with

me, namely the fact, of which I was ignorant when

the first edition was published, that a further instalment

of the correspondence between Sophie

Dorothea and Königsmarck is preserved in the

Secret State Archives at Berlin. The letters

herein are all from Lund, and found their way

into Sweden through Amalie, Countess Lewenhaupt,

Königsmarck’s sister, who married a Swedish

nobleman and eventually settled in Sweden. But

there are others.

viiIt was known that, after the catastrophe of July

1, 1694, the Hanoverian Government seized many

of the letters that had passed between the lovers,

and these were used against the Princess with

crushing effect, to bring about her divorce on

Hanover’s own terms. As Leibniz says, “They

would never have believed at Celle that she was

so guilty had not her letters been produced”.[1] The

fate of these letters has long been a mystery. It

was known that Duke George William wished them

to be sent to Celle to be destroyed, but the Elector

Ernest Augustus refused and kept them at Hanover.

It was afterwards rumoured that George II., on his

first visit to Hanover after his accession to the

English throne, burned them with his own hands,

to conceal all traces of his mother’s disgrace, but

the rumour was unfounded. It now appears that

all, or nearly all, of them are in existence, and some

are those preserved in the Secret State Archives of

Berlin.

The exact way in which these letters reached

Berlin is unknown, but they have been there a long

time. According to the Calendar of the Secret

State Archives they were found among the private

papers of Frederick the Great at Sans Souci, after

his death. The luckless prisoner of Ahlden was

his grandmother, her daughter, the second Queen

of Prussia, was his mother. It is known that the

Queen of Prussia was much interested in the fate

of her unhappy mother, she corresponded with her

secretly, and at one time sought to obtain her release.

It is probable, therefore, that these letters (a part

of the incriminating correspondence seized by the

viiiHanoverian Government) were sent to Berlin by

order of George I. to convince his daughter, the

Queen of Prussia, of her mother’s errors and so

disarm her sympathy. After the Queen’s death

the letters were not returned to Hanover; they

passed into the hands of Frederick the Great,

and thence into the safe keeping of the Berlin

State Archives.

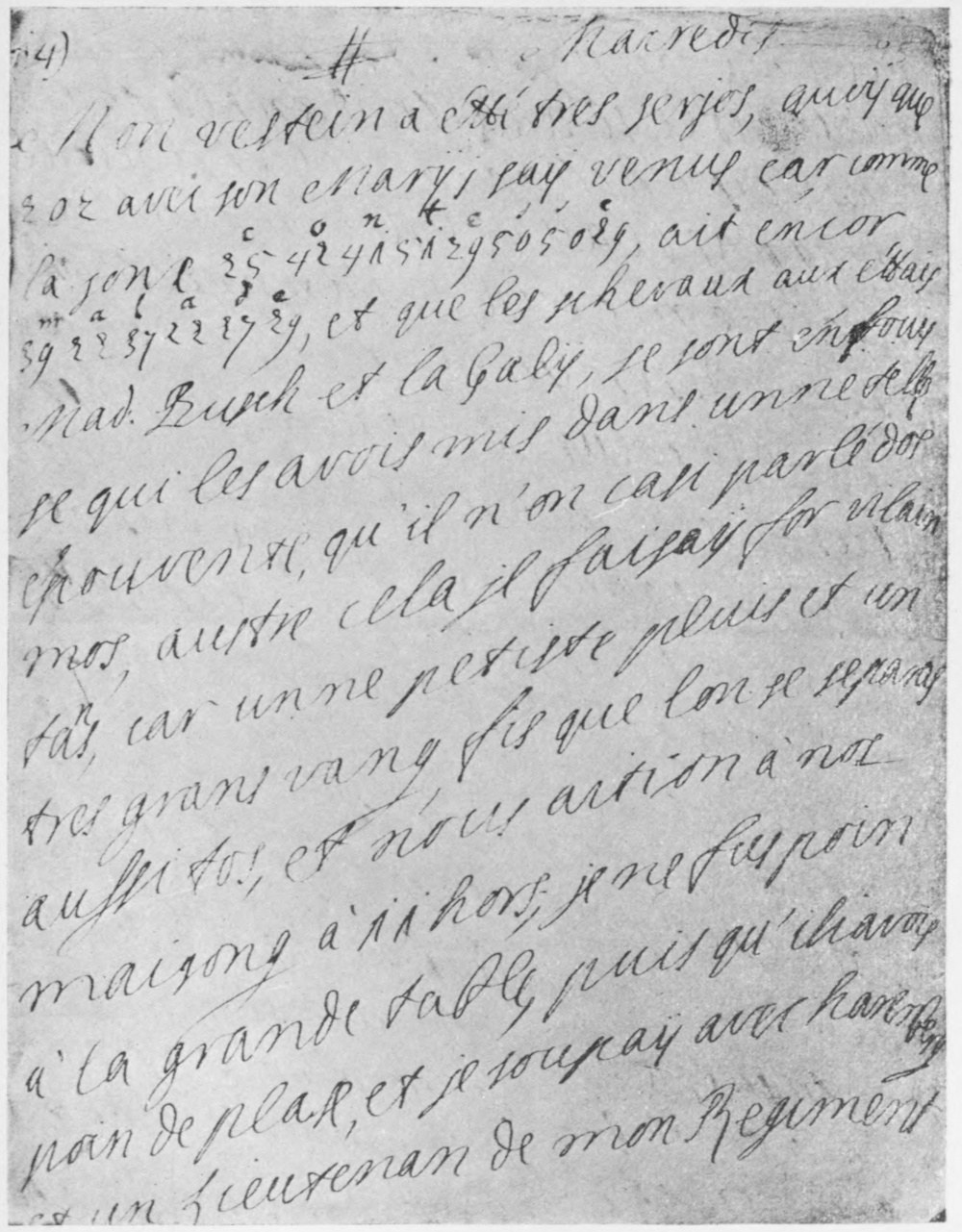

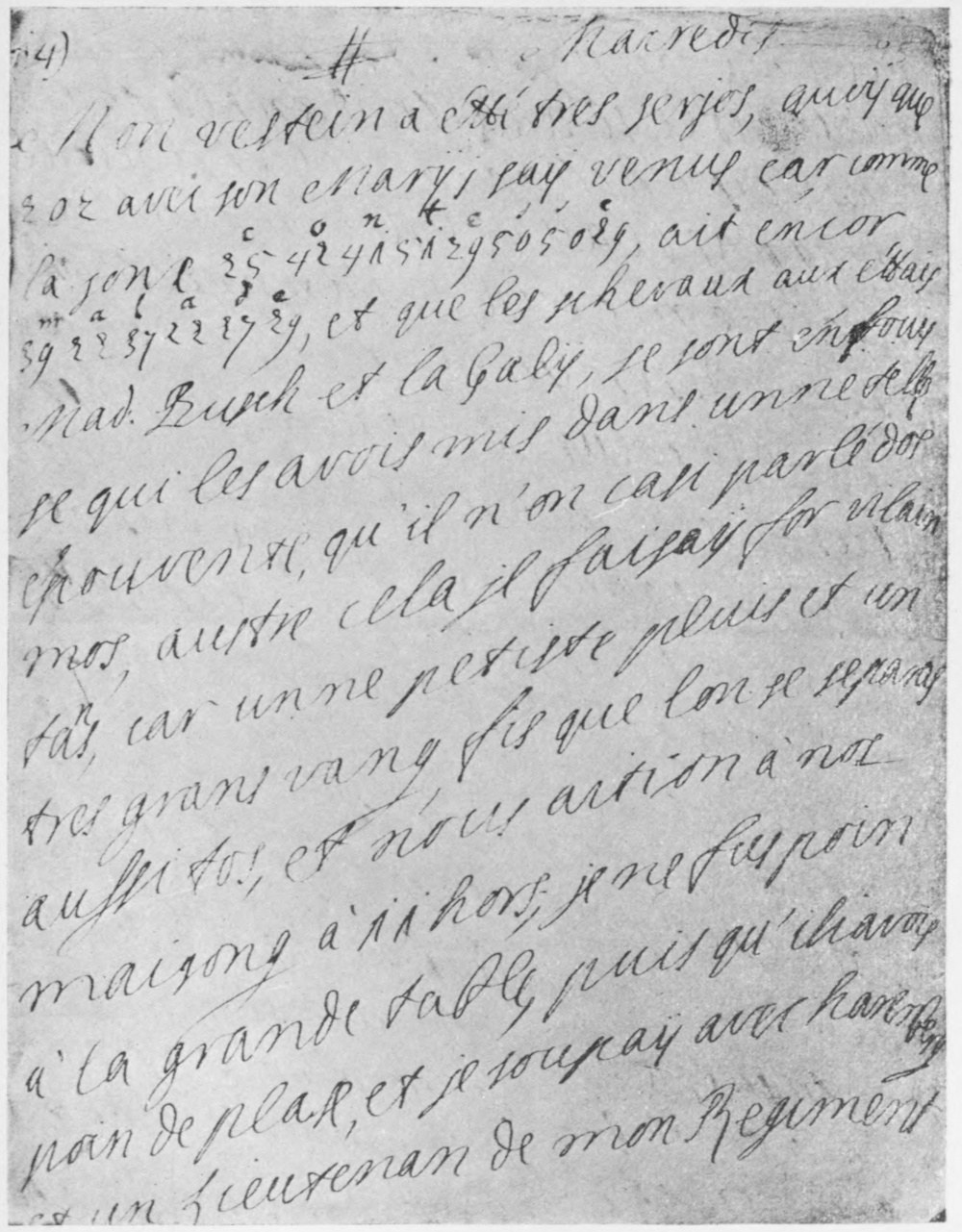

The correspondence between Sophie Dorothea

and Königsmarck is very voluminous. The greater

part of it (six hundred and seventy-nine sheets, one

hundred and ninety-nine from the Princess and four

hundred and eighty from Königsmarck) is preserved

in the university library of Lund. The letters at

Berlin number sixty-five sheets, fifteen from the

Princess and fifty from Königsmarck. It is certain

that the letters at Berlin and those at Lund spring

from the same source, the exact similarity of the

writing, the use of the same cypher and the same

nicknames, the identity of sentiment and style, and

the fact that some of the Berlin letters seem to be

answers to some of those at Lund and vice versa,

prove this beyond doubt. Clearly they stand or fall

together. Applying to the Berlin letters the same

tests as applied to those at Lund, they yield absolutely

the same results.

The Berlin letters afford little historical interest

outside the politics of the petty courts of Hanover

and Celle. Like those at Lund they are alternately

full of jealous reproaches and passionate avowals

of love. They shed no fresh light on the events

immediately preceding the catastrophe of July 1,

1694, for they appear to be written prior to the visit

Königsmarck made to Dresden before he returned

to Hanover for the last time. Letters must have

passed between the lovers in the months preceding

ixthe tragedy, and these are still needed to make the

correspondence complete. But they are not at Berlin,

they are not at Lund, they are not at Hanover. The

question remains, Where are they?

Last summer, when in Germany, I learned

that more love-letters of Sophie Dorothea and

Königsmarck still existed, over and above those

at Lund and Berlin. I learned this important

fact from a trustworthy source which I am not

permitted at present to make public. These remaining

letters were preserved at Hanover until

1866, not in the Royal Archives, but among the

Guelph domestic papers at Herrenhausen. When

the late King of Hanover, George V., was wrongfully

despoiled of his kingdom by Prussia, and

forced to live in exile, he rightly took his family

papers with him into Austria. Among those

papers was some of the correspondence between

his ancestress Sophie Dorothea and Königsmarck.

These letters are now in the possession of his son,

the Duke of Cumberland, de jure King of Hanover,

at Gmünden. What their contents are I am unable

to say, but it is probable that they contain the

missing links wanted to make the chain of the correspondence

complete. It is my desire some day

to translate the whole correspondence at Lund,

at Berlin, and at Gmünden, and arrange it in

chronological order with the aid of first-hand

documentary evidence drawn from other sources.

(But this, of course, depends upon the necessary

permission being granted.) For this reason, and

because they shed no fresh light on the tragedy,

I have not given herein any of the Berlin letters.

On the contrary, I have omitted from this edition

a few of those letters published in the first, which

were merely a repetition of others; their great

xsimilarity of style and sentiment tended to weary

rather than to edify.[2]

I should like to repeat that this book is largely

based upon papers found in the Hanoverian archives

and elsewhere, duly specified in footnotes. The

despatches of Sir William Dutton Colt, of Cresset

and of Poley, English envoys at Hanover during

the period under consideration, and of Stepney,

sometime English envoy at Dresden, now preserved

in the State Paper Office, London, have also been

drawn upon freely. To this list of hitherto unpublished

documents there remain to be added many

letters from the correspondence at Lund, translated

from the French of the original documents. These

have never before been published in English and

(except for a few unimportant extracts in a Swedish

book long since out of print) have never been published

in any language. I may claim to be the first

to edit and arrange this correspondence in something

like chronological order, and to compare it

with historical documents of undoubted authenticity

with a view to proving its genuineness.

Every effort was made in the first edition to render

this biography as complete as possible. I have now

in the light of subsequent knowledge revised the

text. I find little to add and little to take away.

My additions are chiefly in matters of detail, and will

be found in notes scattered throughout the volume.

These notes for the most part either go to prove

further the genuineness of the letters, or to quote

fuller authorities for the text—to specify more clearly

xiwhat is founded on first-hand historical evidence,

and what is derived from less trustworthy sources.

In this I should like to acknowledge the help

I have derived from my critics, more especially from

the writer of the review of my book in the Edinburgh

Review,[3] and the essay by Dr. Robert Geerds, the

eminent German critic and historian in the Allgemeine

Zeitung.[4]

The writer in the Edinburgh Review, an expert

who has himself examined the contested letters at

Lund, and the admittedly genuine ones at Hanover,

and compared them, says in contravention of a doubt

cast on their genuineness:—

“Allowing for the interval of time and for the

difference of circumstances under which the [Princess’s]

love-letters to Königsmarck and her formal

letters to the Electress were respectively written, we

have no hesitation in saying that it is impossible,

after placing the handwritings side by side, to assert

that there is no resemblance between them. We

have also had an opportunity of comparing a photograph

of Königsmarck’s abbreviated signature with

photographs of genuine signatures of his preserved

at Lund and at Hanover respectively, and no doubt

whatever is left in our mind as to the genuineness

of the (abbreviated) signature in the impugned

correspondence.”

And again:—

“After much careful consideration we feel bound

to express our belief that the probability of these

letters having been written by Sophie Dorothea and

Königsmarck is a very strong one indeed”....

xiiDr. Robert Geerds, who has examined and

compared the letters at Lund with those at Berlin

as well as Hanover, says:—

“The writing of some of the Lund letters ...

corresponds so noticeably with the Hanoverian

writing that it is impossible to doubt they were

written by Sophie Dorothea”.

And again, after reference to my discoveries of

the undesigned coincidences between incidents

mentioned in the letters and in Colt’s despatches:—

“No unprejudiced person can any longer doubt

that in this correspondence, which has been called

into question, we have the true and genuine love-letters

of the unfortunate pair whose tragic fate has

met with such universal sympathy”.[5]

I should like to thank Dr. Carl Petersen,

Assistant Librarian at Lund University, for his

courtesy and assistance; Count Carl Lewenhaupt

(sometime Swedish and Norwegian Minister in

London) for procuring me the portrait of Aurora

Königsmarck, now in the possession of the elder

branch of the Lewenhaupt family; Count C. G.

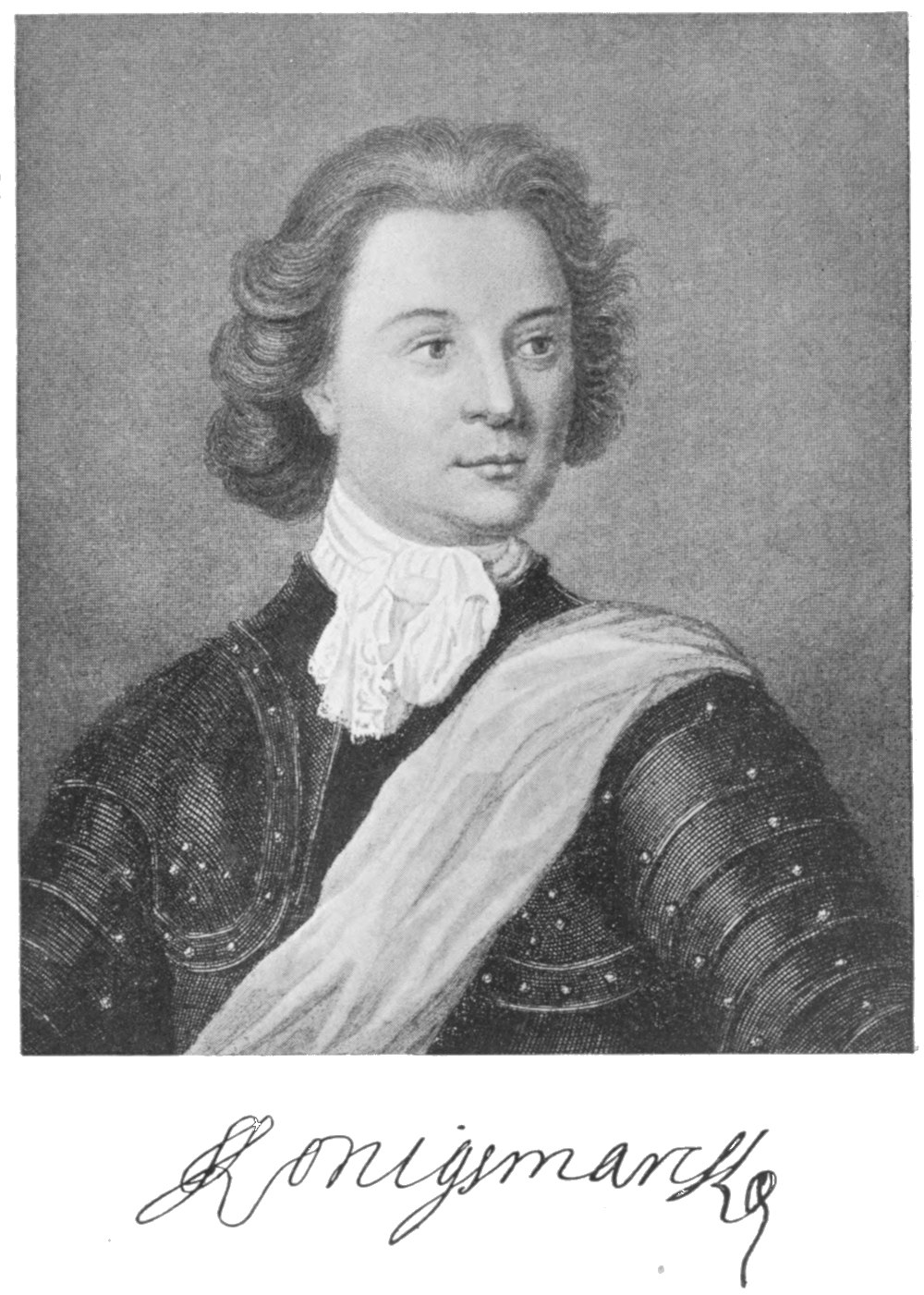

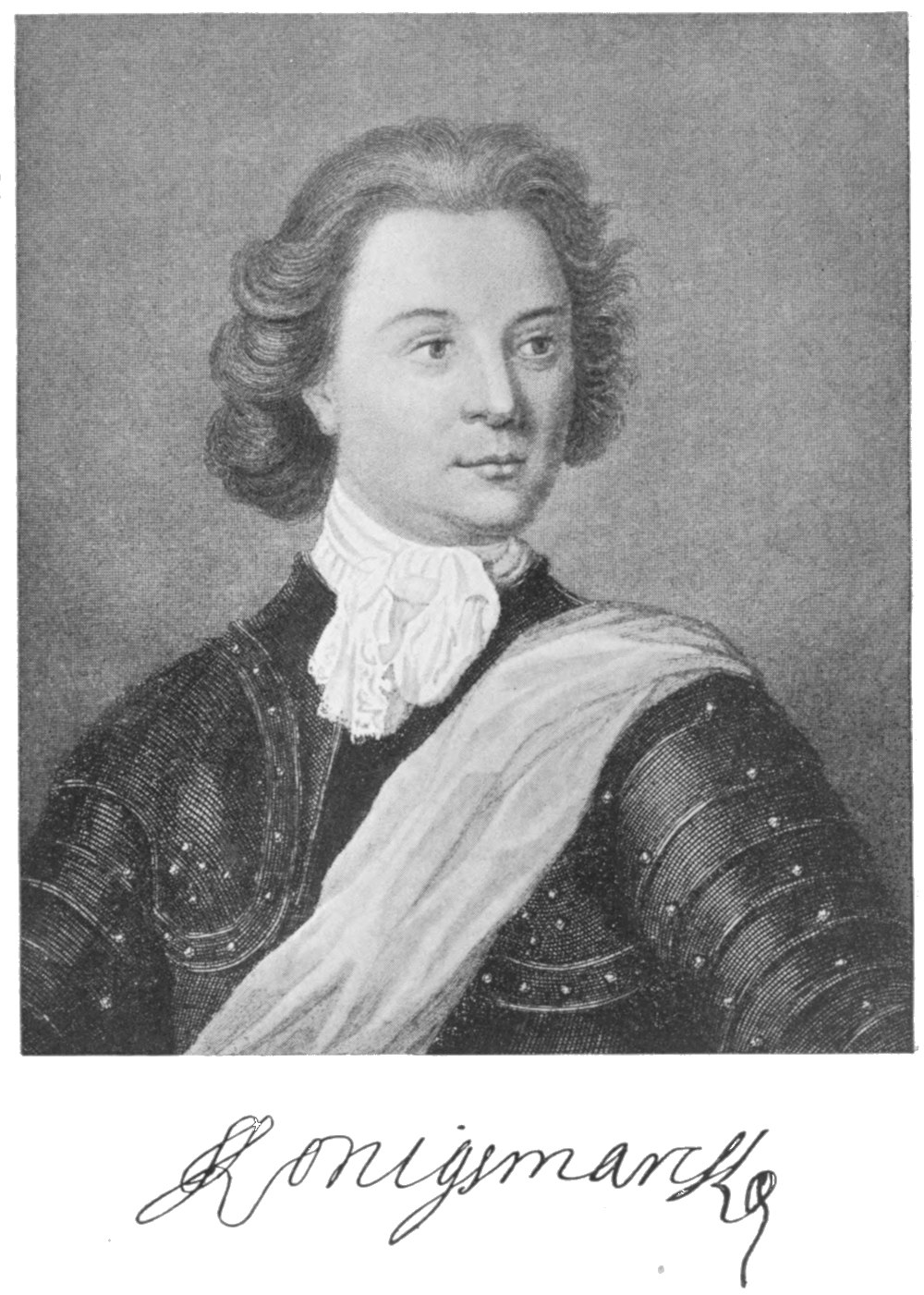

von Rosen for permission to reproduce the portrait

of Philip Christopher Königsmarck; Count

Kielmansegg for allowing me to see Lady Darlington’s

patent of peerage at Gülzow; and Count

Erich Kielmansegg for calling my attention to a

slight error in the history of the Lund letters,

corrected in this edition.

As an edition of this book has been published

in America without my knowledge or consent, and

xiiias it is, moreover, full of grammatical and other

errors, for which I am not responsible, I take this

opportunity of saying that this is the only authorised

edition for sale in America.

In conclusion, I should like to repeat what I

wrote in the preface to my first edition: “The story

of the romantic life of this uncrowned Queen has

been shrouded in mystery, and she has been even

more misrepresented than Mary Queen of Scots.

Her imprisonment in the lonely castle of Ahlden

was longer and more rigorous than Mary’s captivity

in England, and the assassination of Königsmarck

was as dramatic as the murder of Rizzio.”

W. H. Wilkins.

March, 1903.

xv

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. |

PAGE |

| |

|

| The Romance of the Princess’s Parentage |

1 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER II. |

|

| |

|

| The Progress of Eléonore |

13 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER III. |

|

| |

|

| The Wisdom of Serpents |

25 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER IV. |

| |

|

| Prince George Goes a-Wooing |

38 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER V. |

| |

|

| The Sacrifice |

47 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER VI. |

|

| |

|

| The Court of Hanover |

59 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER VII. |

|

| |

|

| The Power of Countess Platen |

70 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER VIII. |

|

| |

|

| Enter Königsmarck |

82 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER IX. |

|

| |

|

| Playing with Fire |

94 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER X. |

|

| |

|

| The Embroidered Glove |

107 |

| xvi |

|

| CHAPTER XI. |

|

| |

|

| History and Authenticity of the Letters |

118 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XII. |

|

| |

|

| The Dawn of Passion |

139 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XIII. |

|

| |

|

| Crossing the Rubicon |

156 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XIV. |

|

| |

|

| The Princess’s Letters |

172 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XV. |

|

| |

|

| Doubts and Fears |

189 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XVI. |

|

| |

|

| The Battle of Steinkirk |

204 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XVII. |

|

| |

|

| The Visit to Wiesbaden |

217 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XVIII. |

|

| |

|

| Königsmarck Returns from the War |

233 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XIX. |

|

| |

|

| The Tryst at Brockhausen |

256 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XX. |

|

| |

|

| Love’s Bitterness |

277 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XXI. |

|

| |

|

| The Campaign against the Danes |

302 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XXII. |

|

| |

|

| The Gathering Storm |

325 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XXIII. |

|

| |

|

| The Murder of Königsmarck |

340 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XXIV. |

|

| |

|

| The Ruin of the Princess |

352 |

| xvii |

|

| CHAPTER XXV. |

|

| |

|

| The Divorce |

371 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XXVI. |

|

| |

|

| The Prisoner of Ahlden |

388 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XXVII. |

|

| |

|

| The Flight of Years |

405 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XXVIII. |

|

| |

|

| Crown and Grave |

421 |

| |

|

| CHAPTER XXIX. |

|

| |

|

| Retribution |

437 |

| |

|

| Appendix |

445 |

| |

|

| Index |

447 |

xix

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| Sophie Dorothea. From a painting formerly at Ahlden |

Frontispiece. |

| |

|

| Eléonore d’Olbreuse, Duchess of Celle. From a painting at Herrenhausen |

Facing page 8 |

| |

|

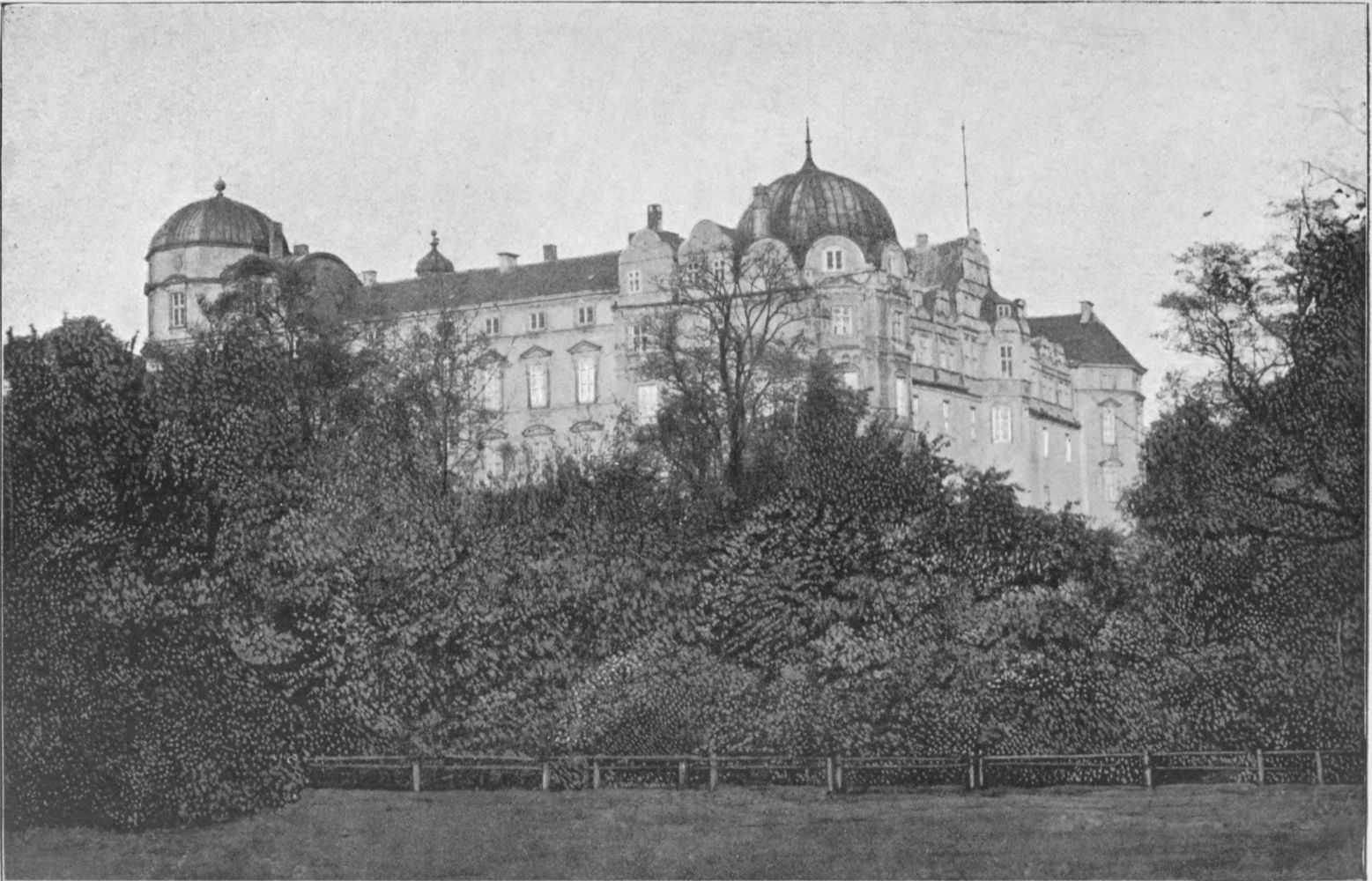

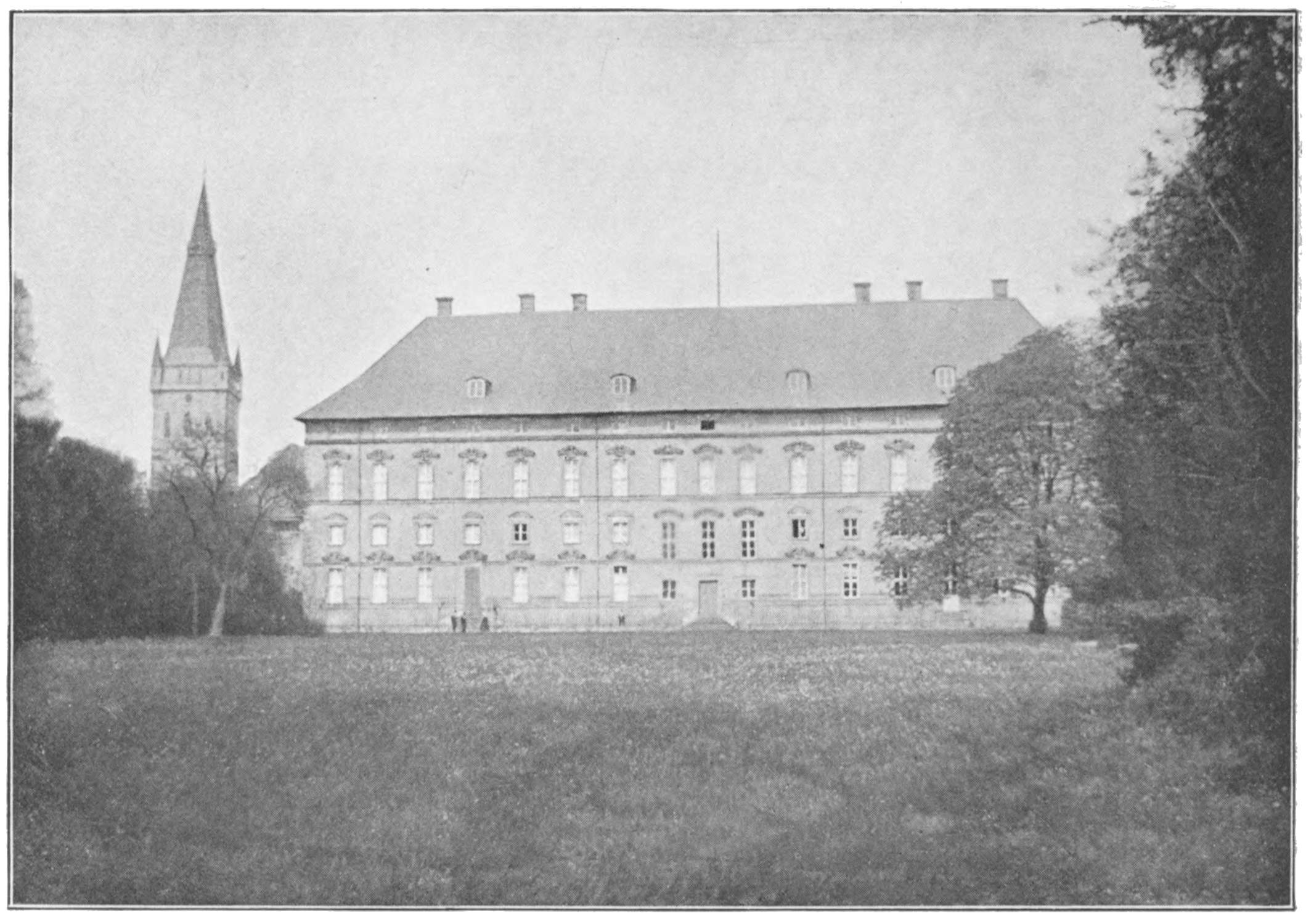

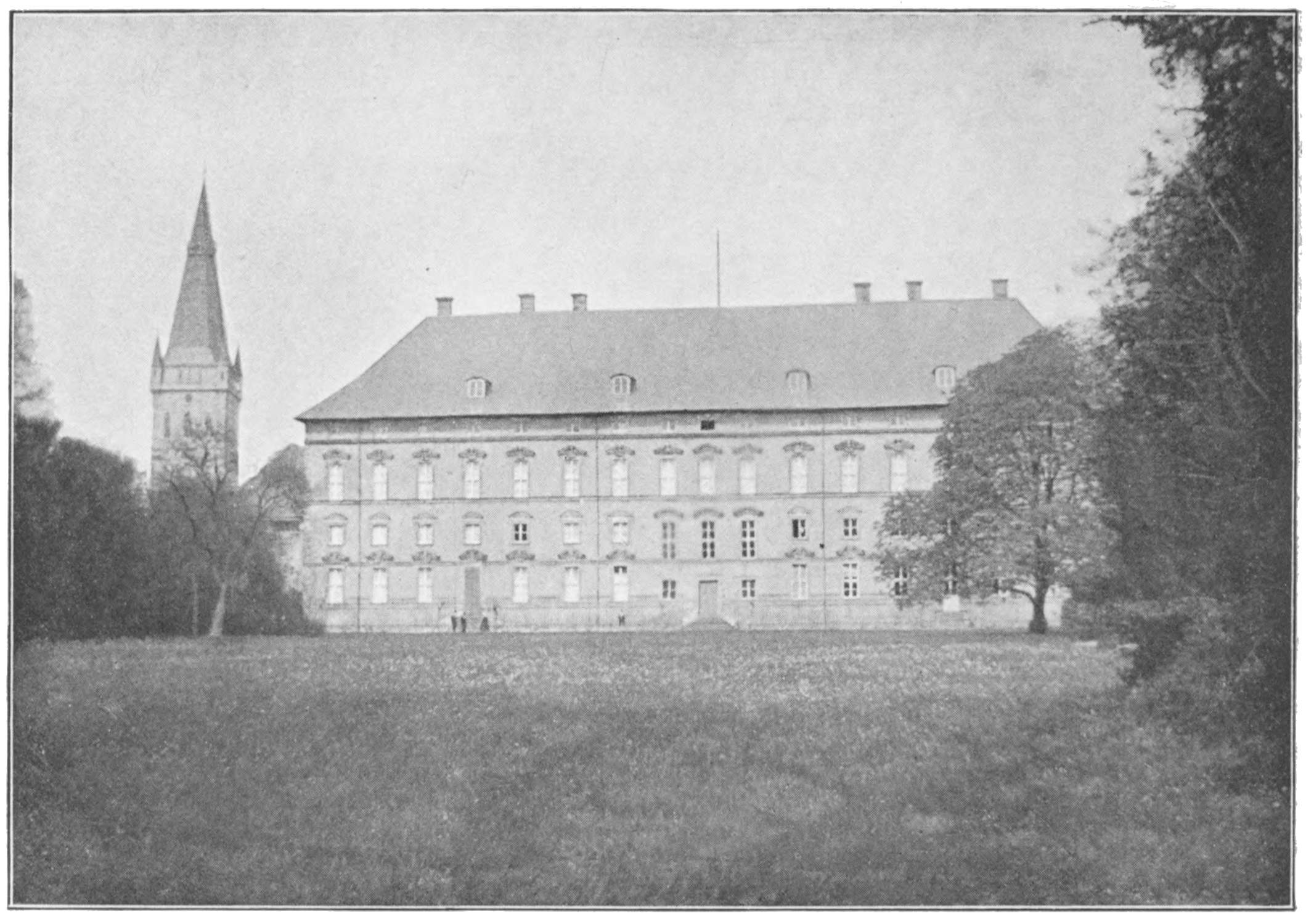

| The Castle of Celle |

” ” 26 |

| |

|

| Prince George Louis of Hanover (afterwards George I. of England). From a picture at Hanover |

” ” 40 |

| |

|

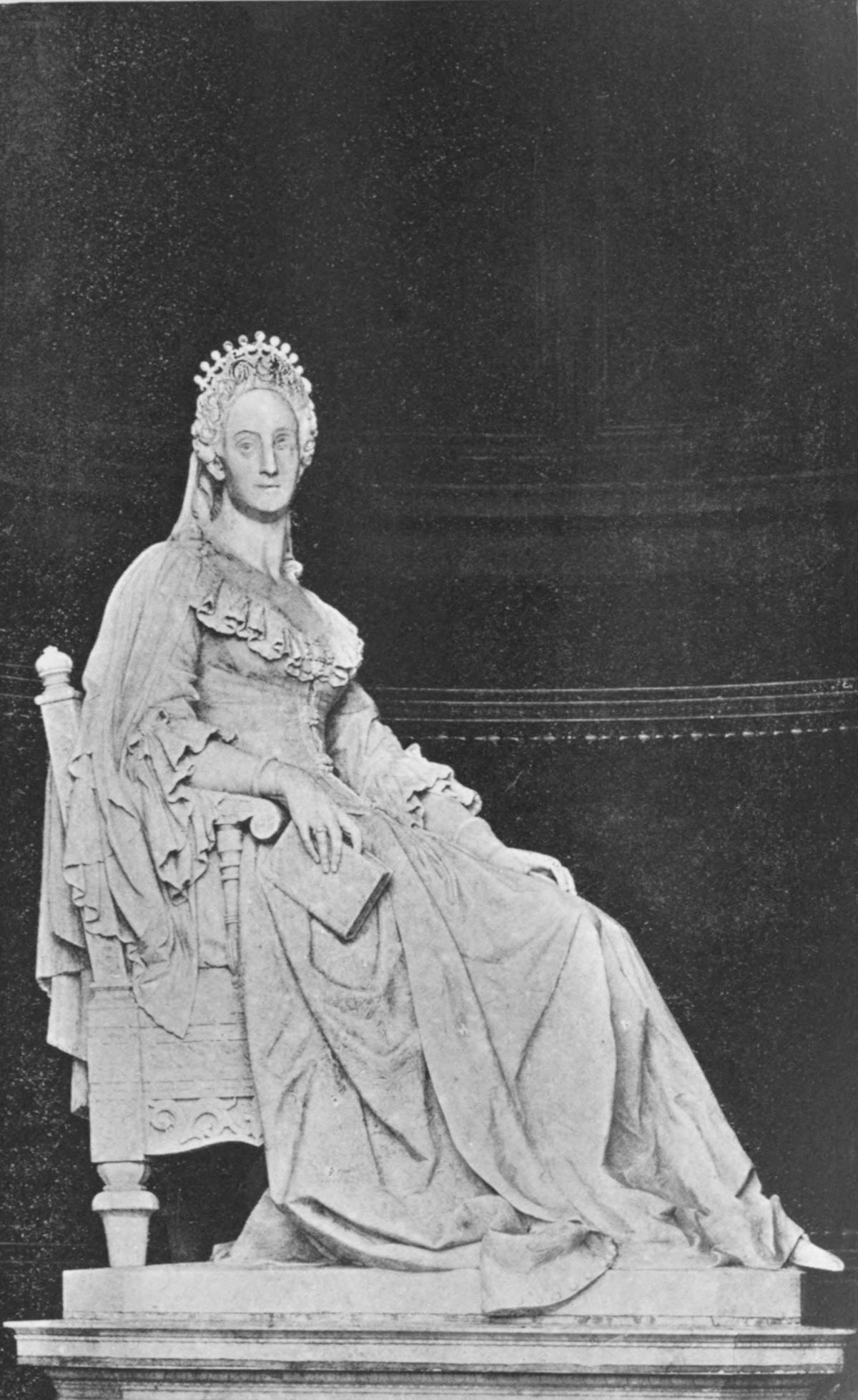

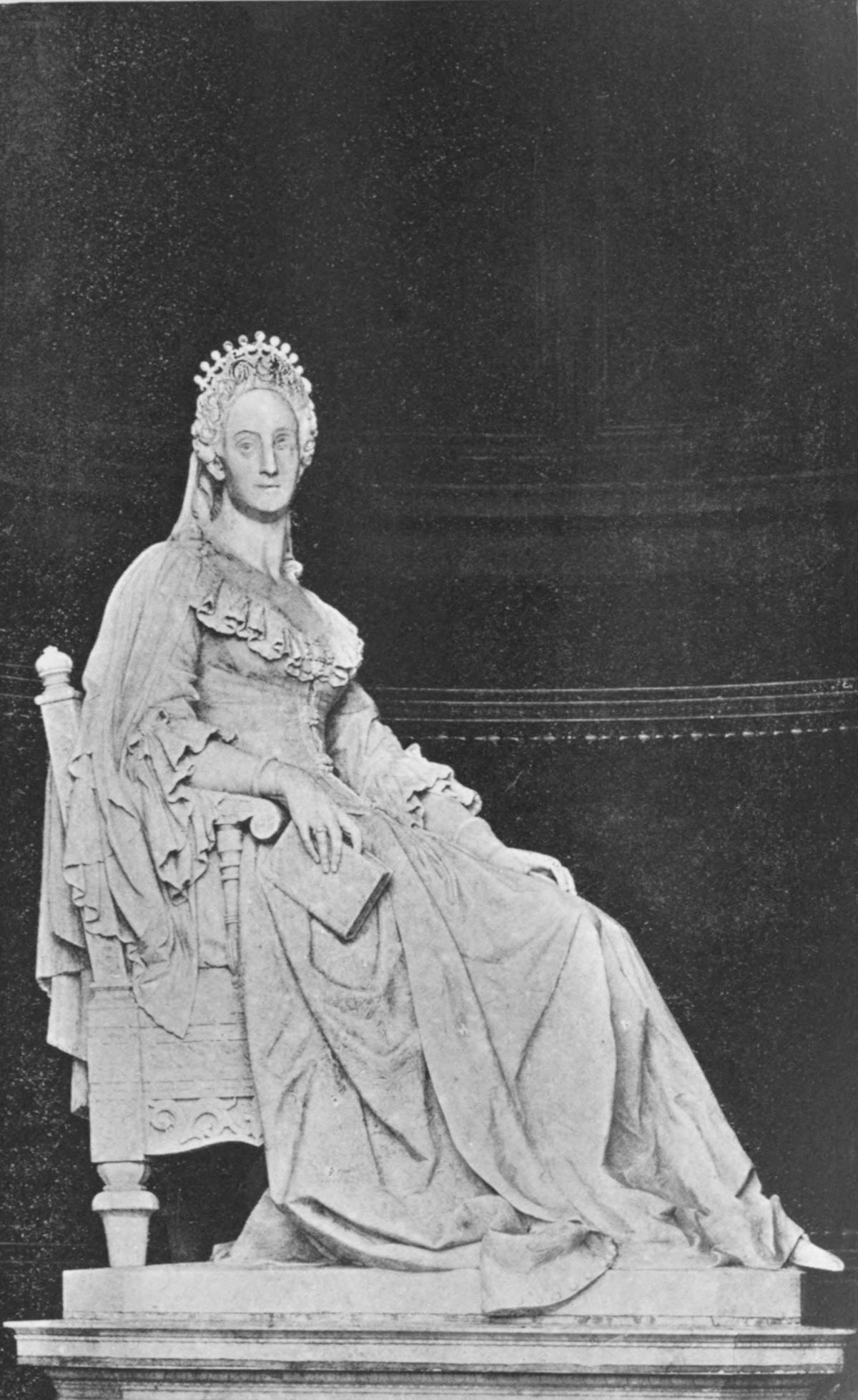

| The Electress Sophia. Photographed from the statue in the gardens of Herrenhausen |

” ” 56 |

| |

|

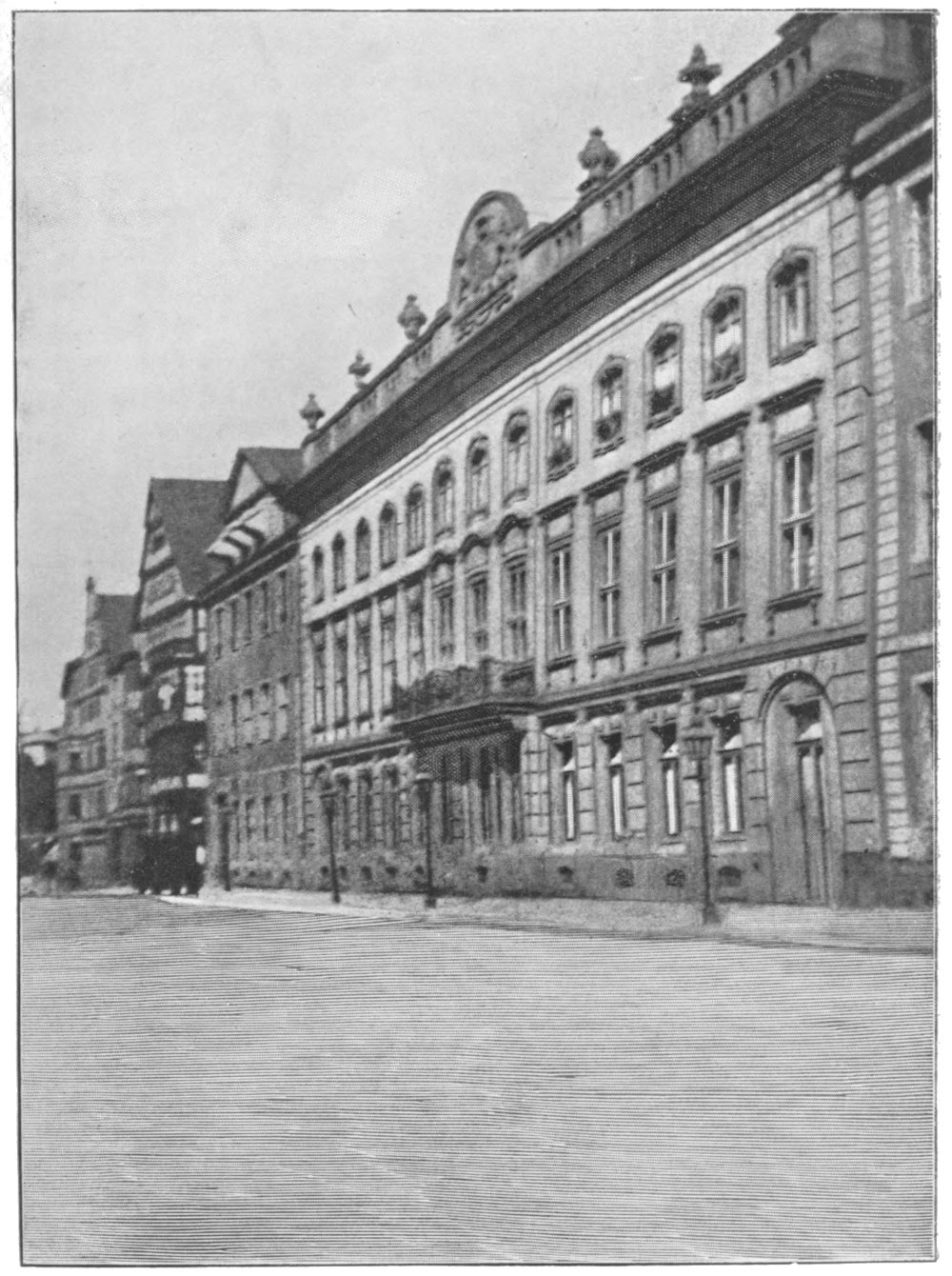

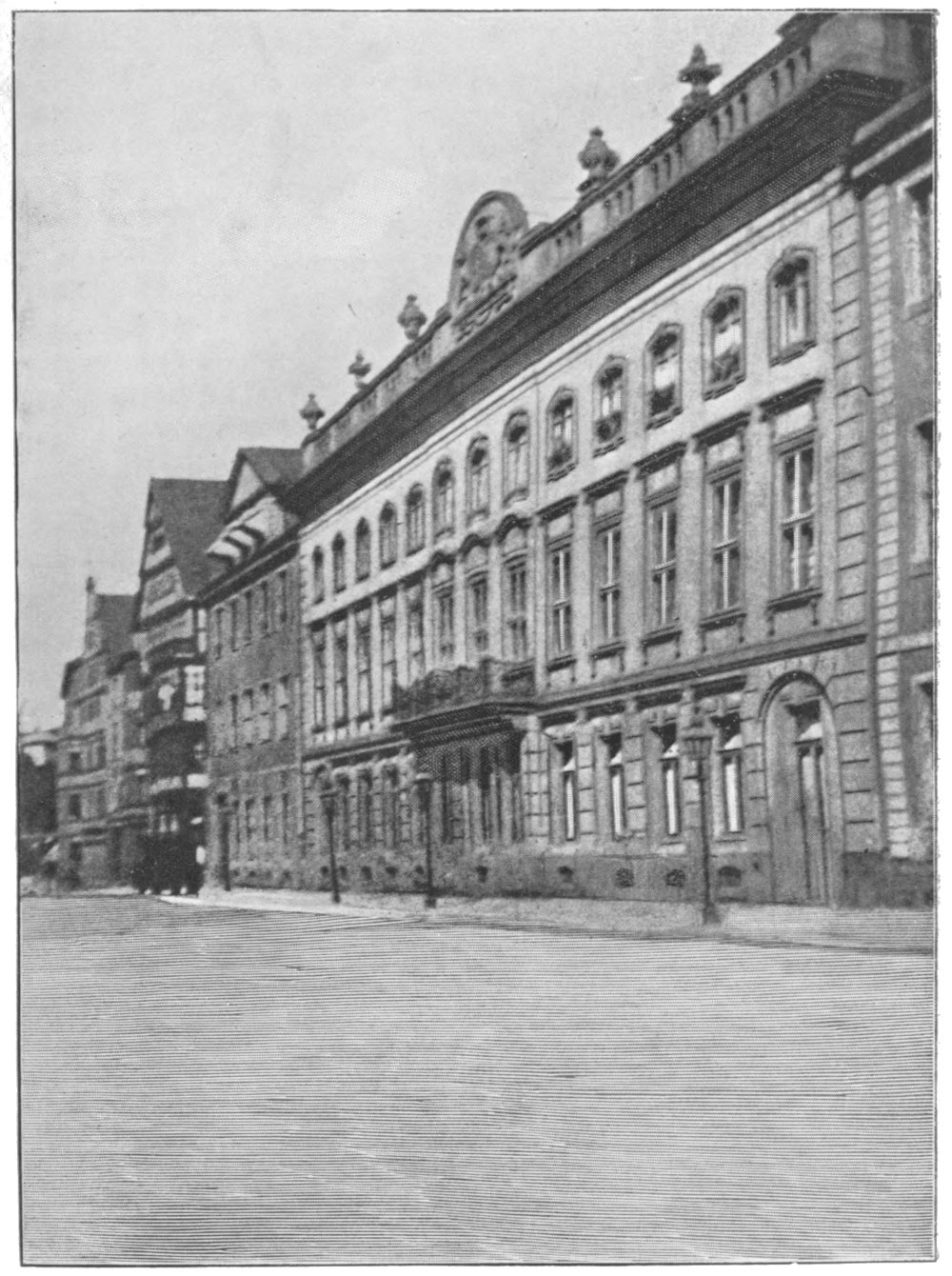

| The Alte Palais, Hanover. From a photograph by the Author |

” ” 74 |

| |

|

| Königsmarck. From the painting at Herrenhausen |

” ” 94 |

| |

|

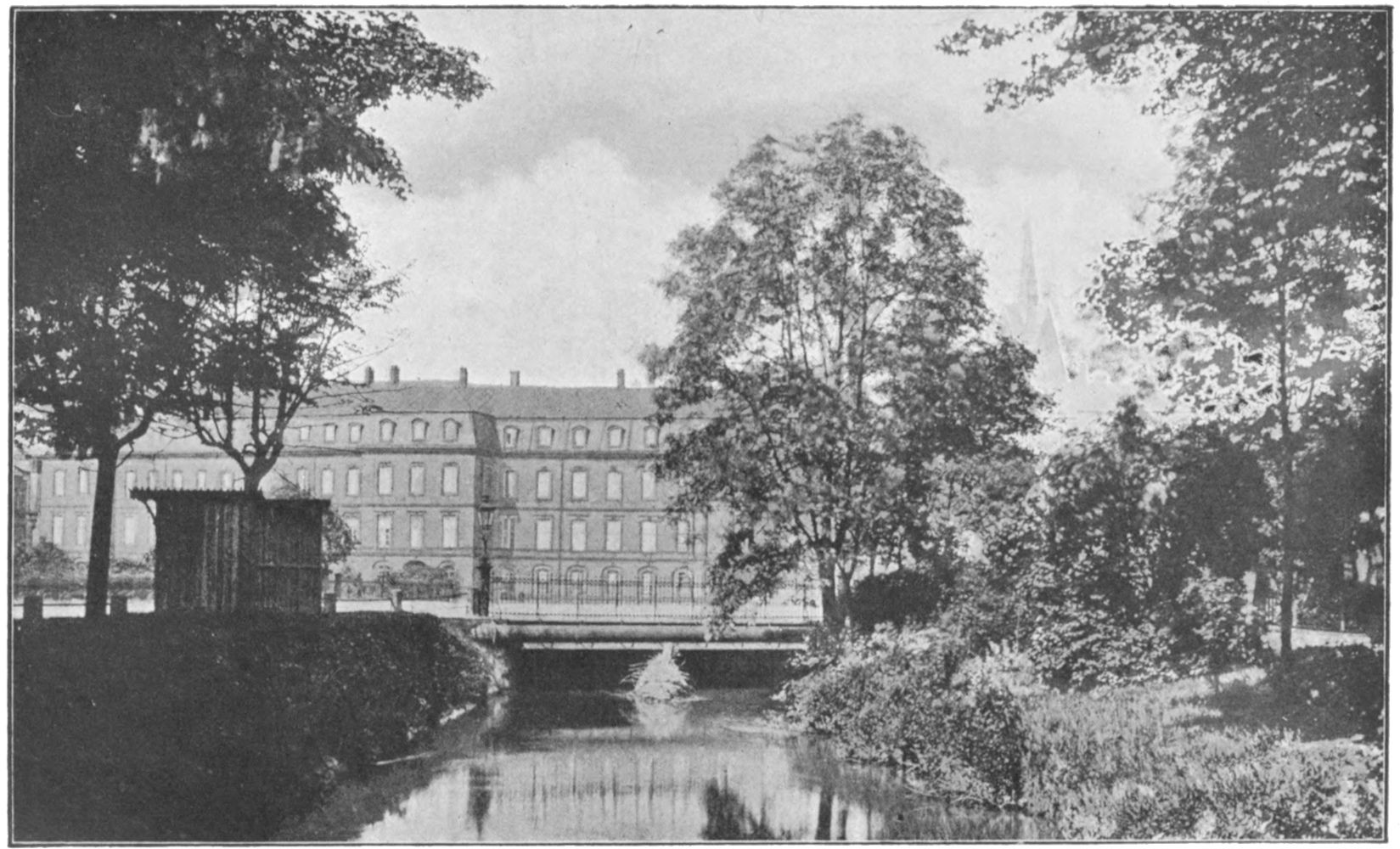

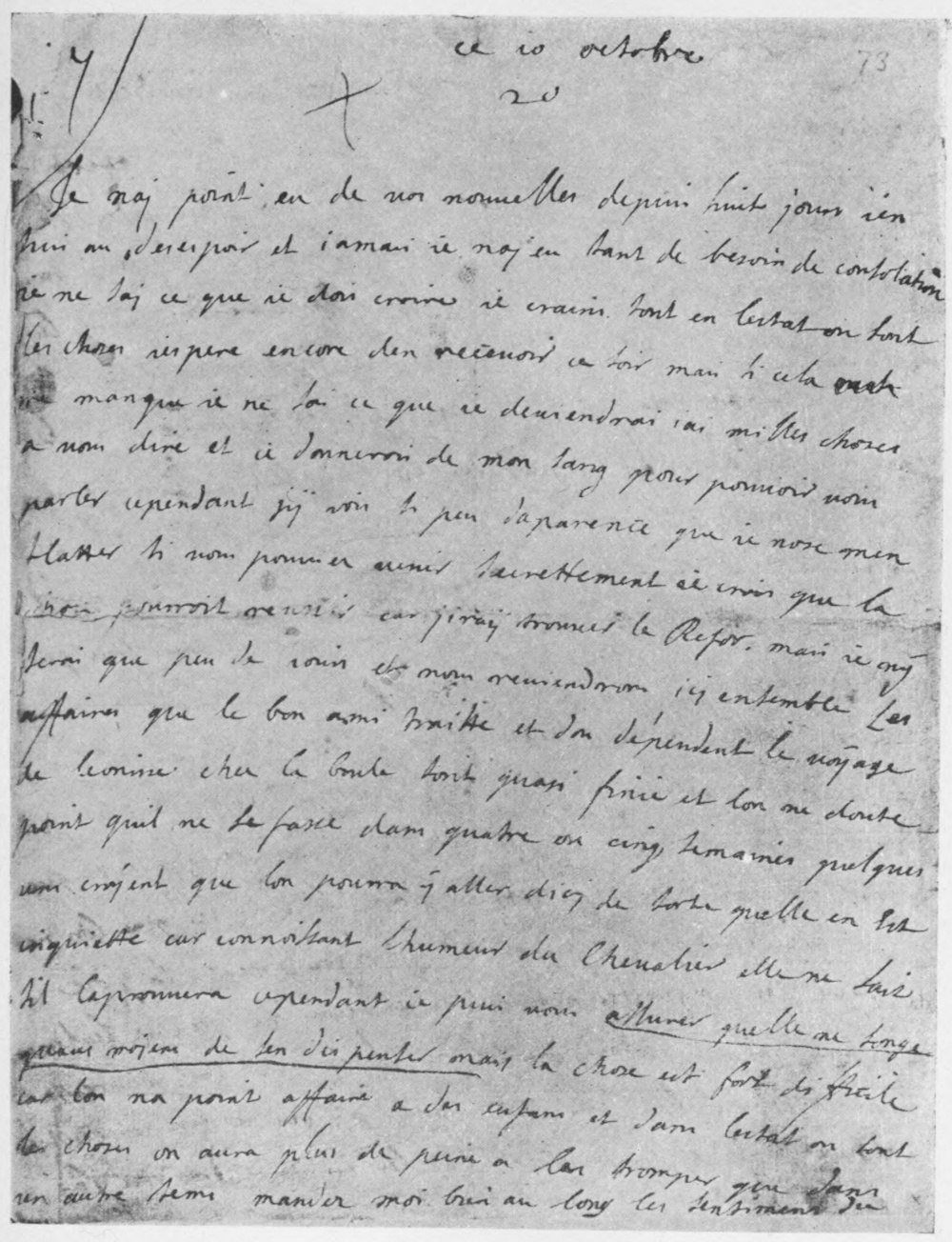

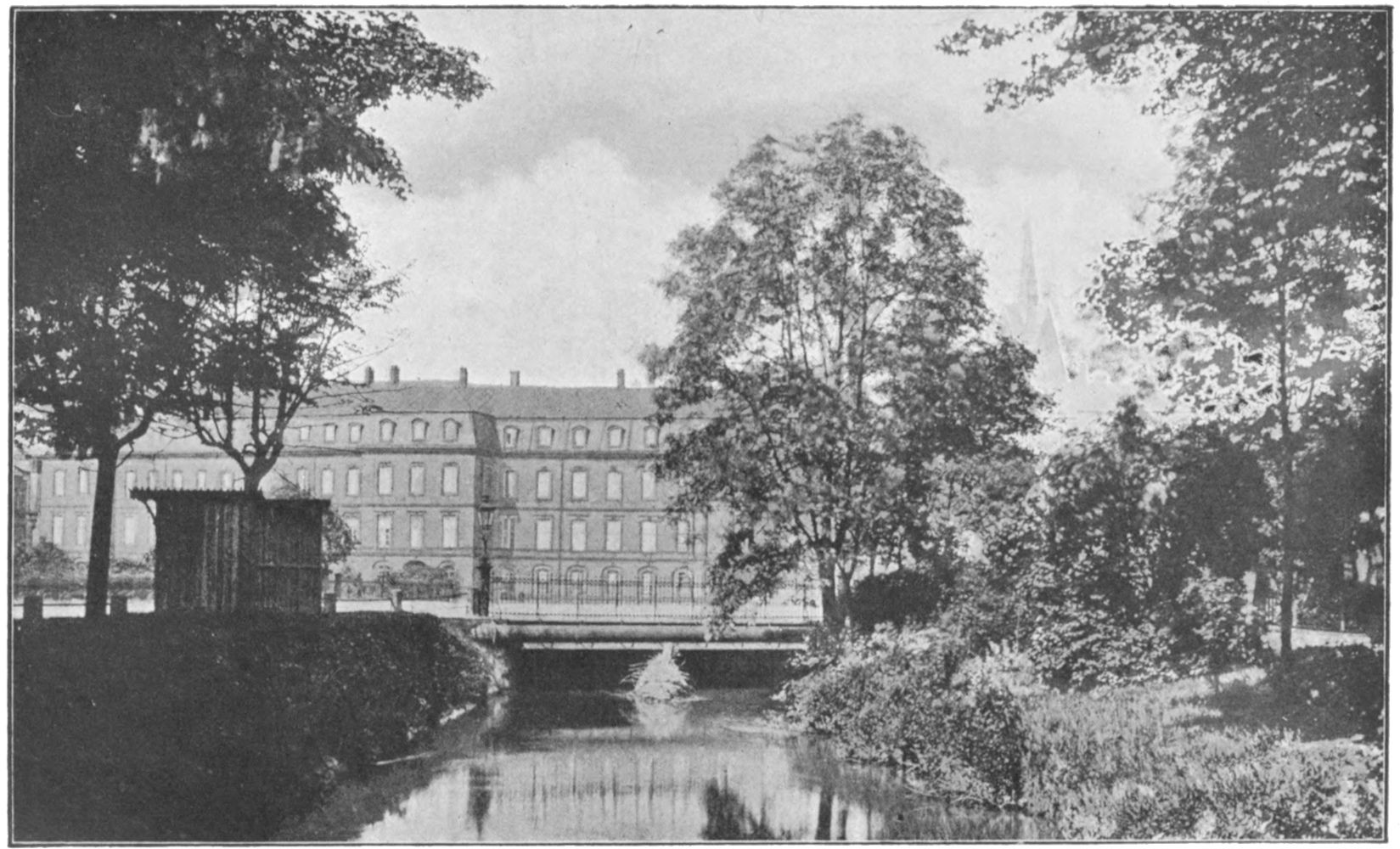

| The Leine Schloss, Hanover |

” ” 110 |

| |

|

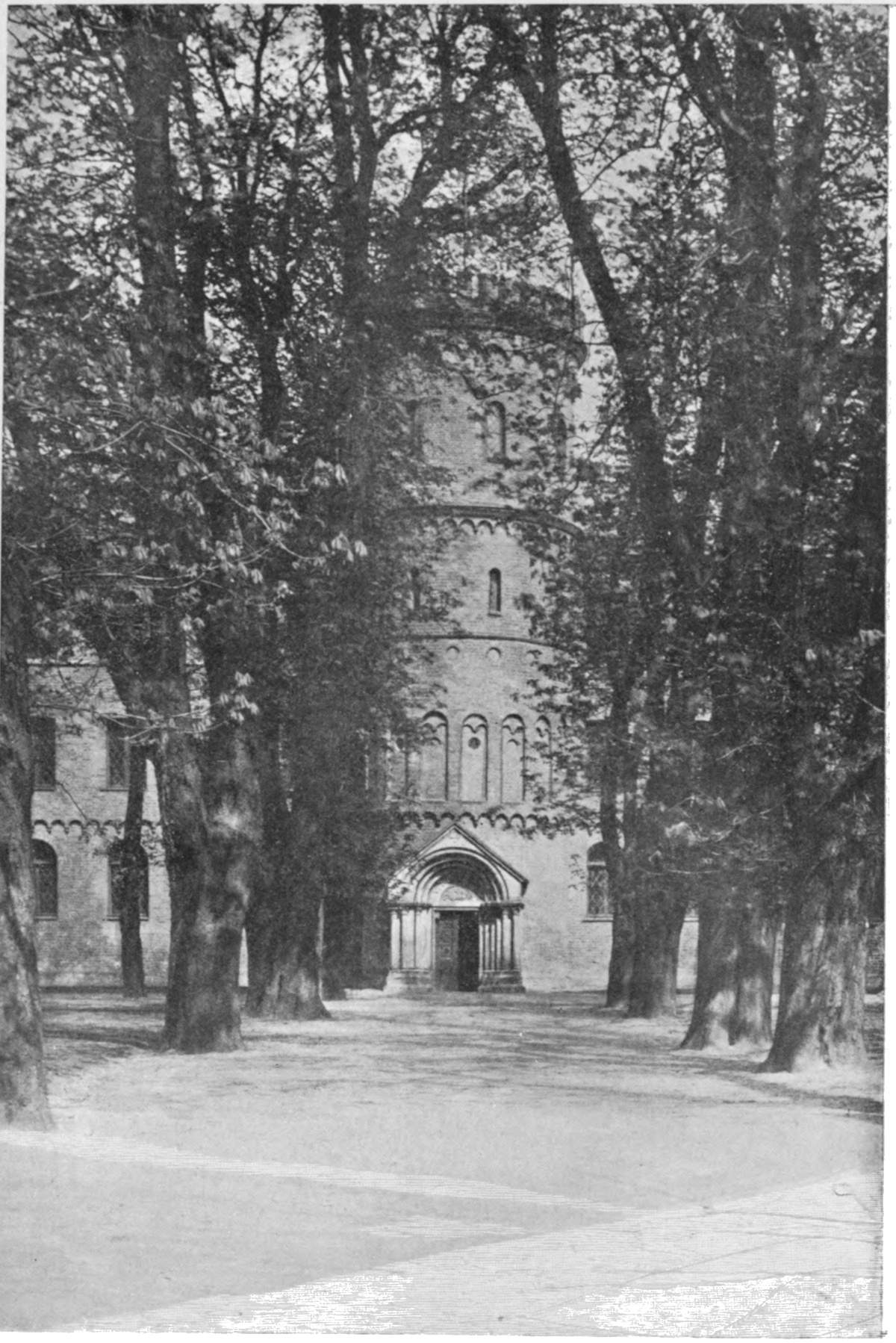

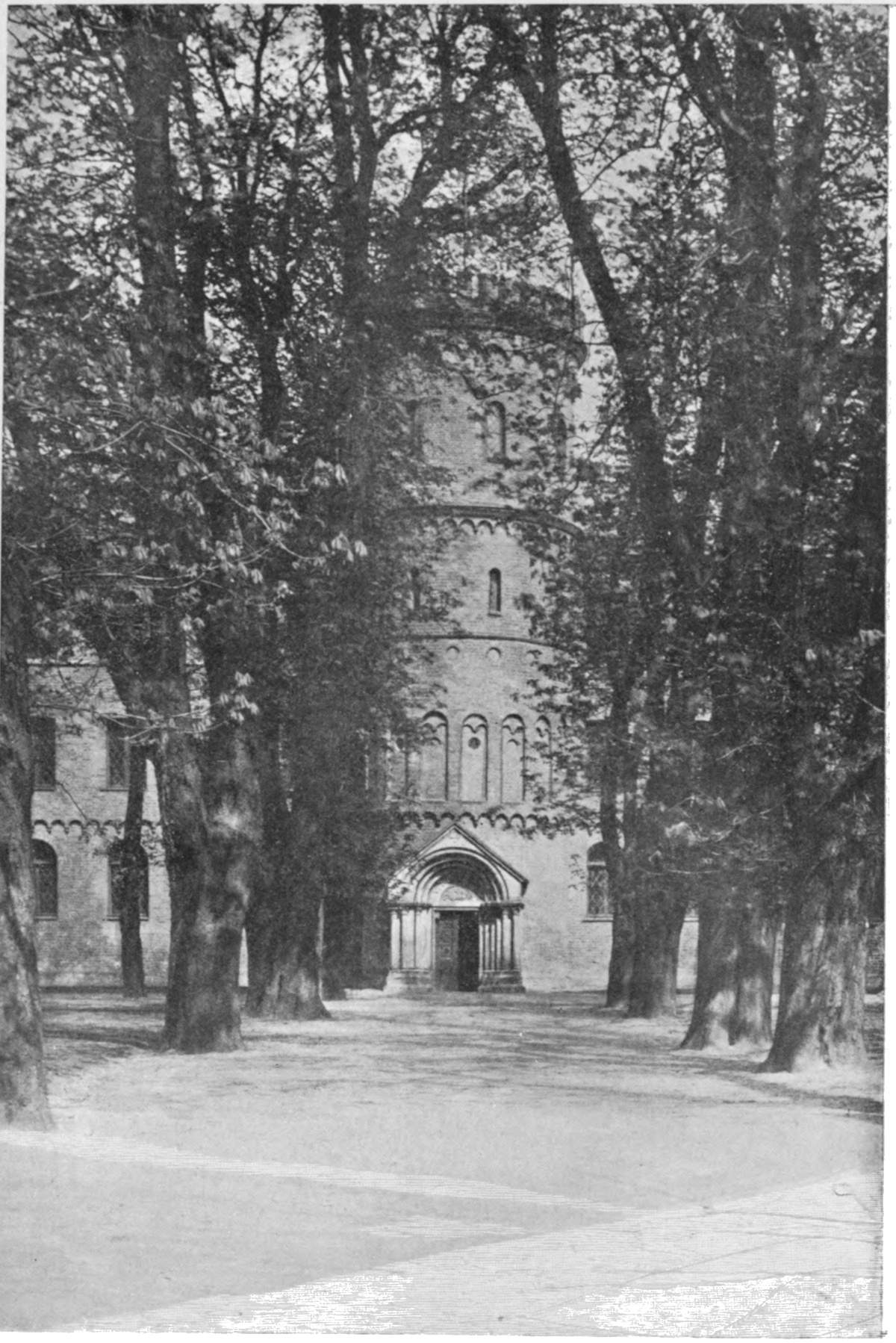

| The University Library, Lund, Sweden |

” ” 128 |

| |

|

| Facsimile of One of Königsmarck’s Letters to the Princess. Photographed from the original manuscript in the University Library of Lund |

” ” 146 |

| |

|

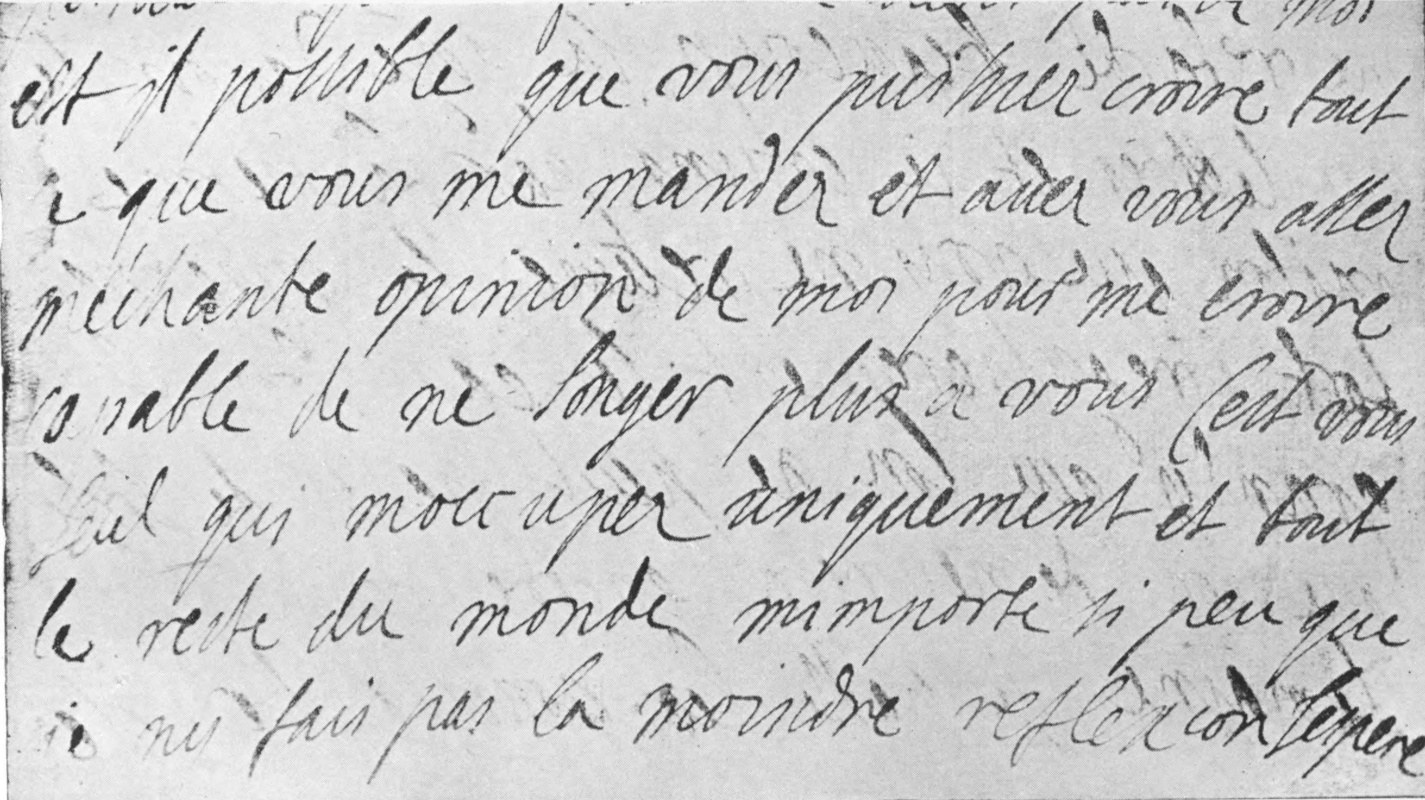

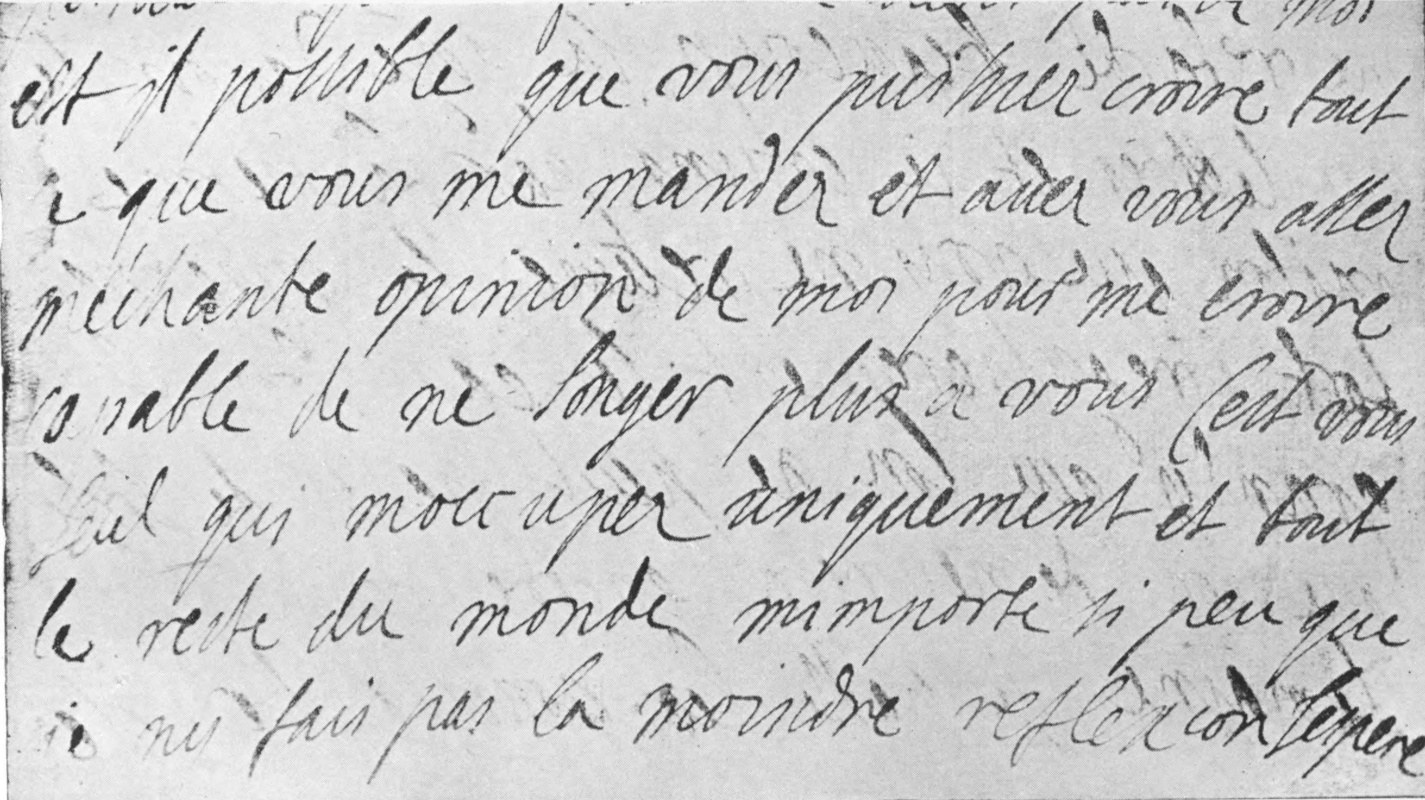

| Facsimile of One of Sophie Dorothea’s Letters to Königsmarck. Photographed from the original manuscript in the University Library of Lund |

” ” 174 |

| |

|

| Sophie Dorothea. From a painting formerly at Ahlden, now at Herrenhausen |

” ” 190 |

| xx |

|

| Facsimile of One of the Princess’s Letters to Königsmarck. Photographed from the original manuscript in the University Library at Lund |

” ” 206 |

| |

|

| Philip Christopher Count Königsmarck. From a painting in the possession of Count Gustav Lewenhaupt |

” ” 224 |

| |

|

| The Countess Aurora Königsmarck. From the painting in the possession of Count C. G. von Rosen |

” ” 244 |

| |

|

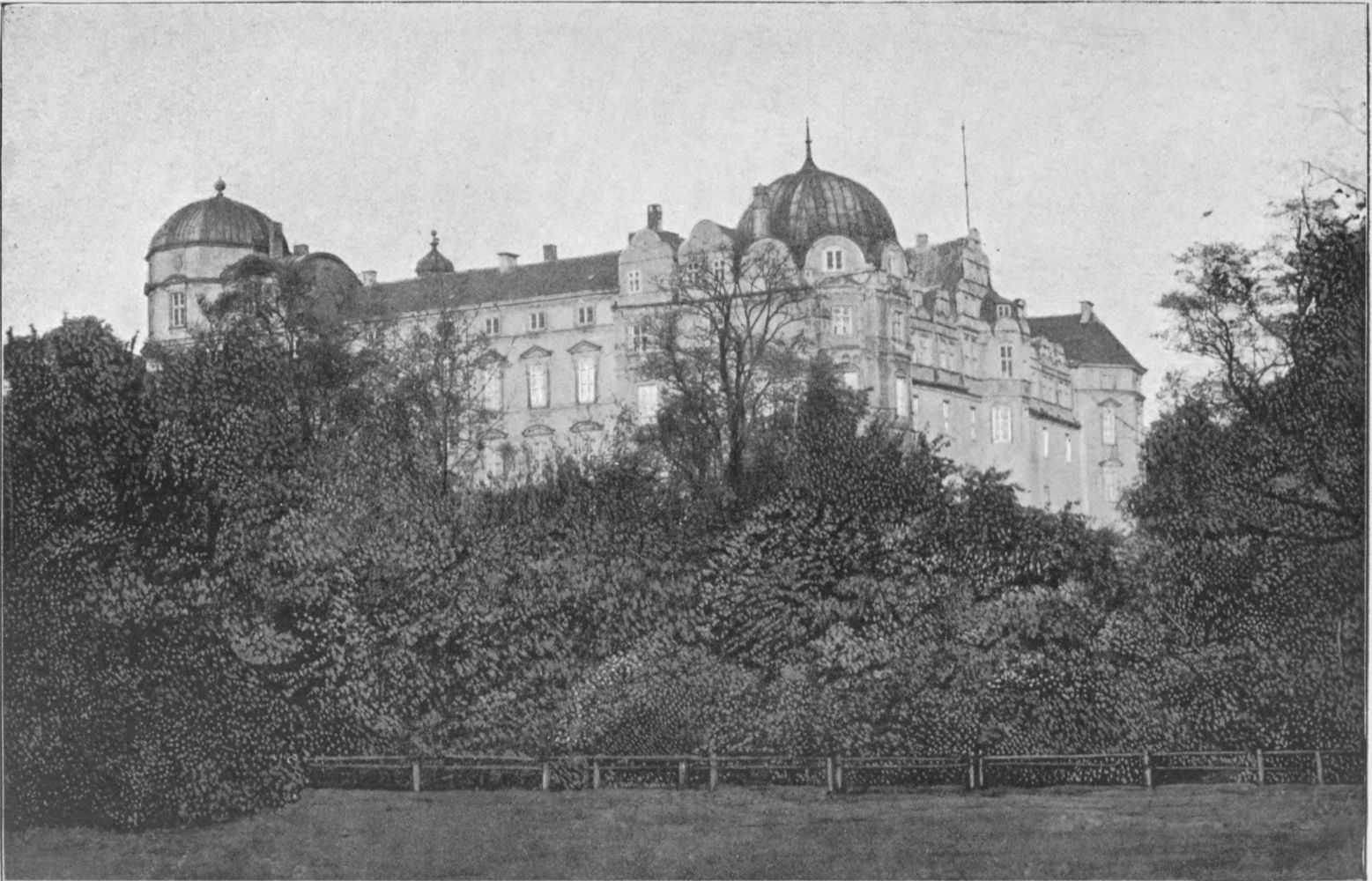

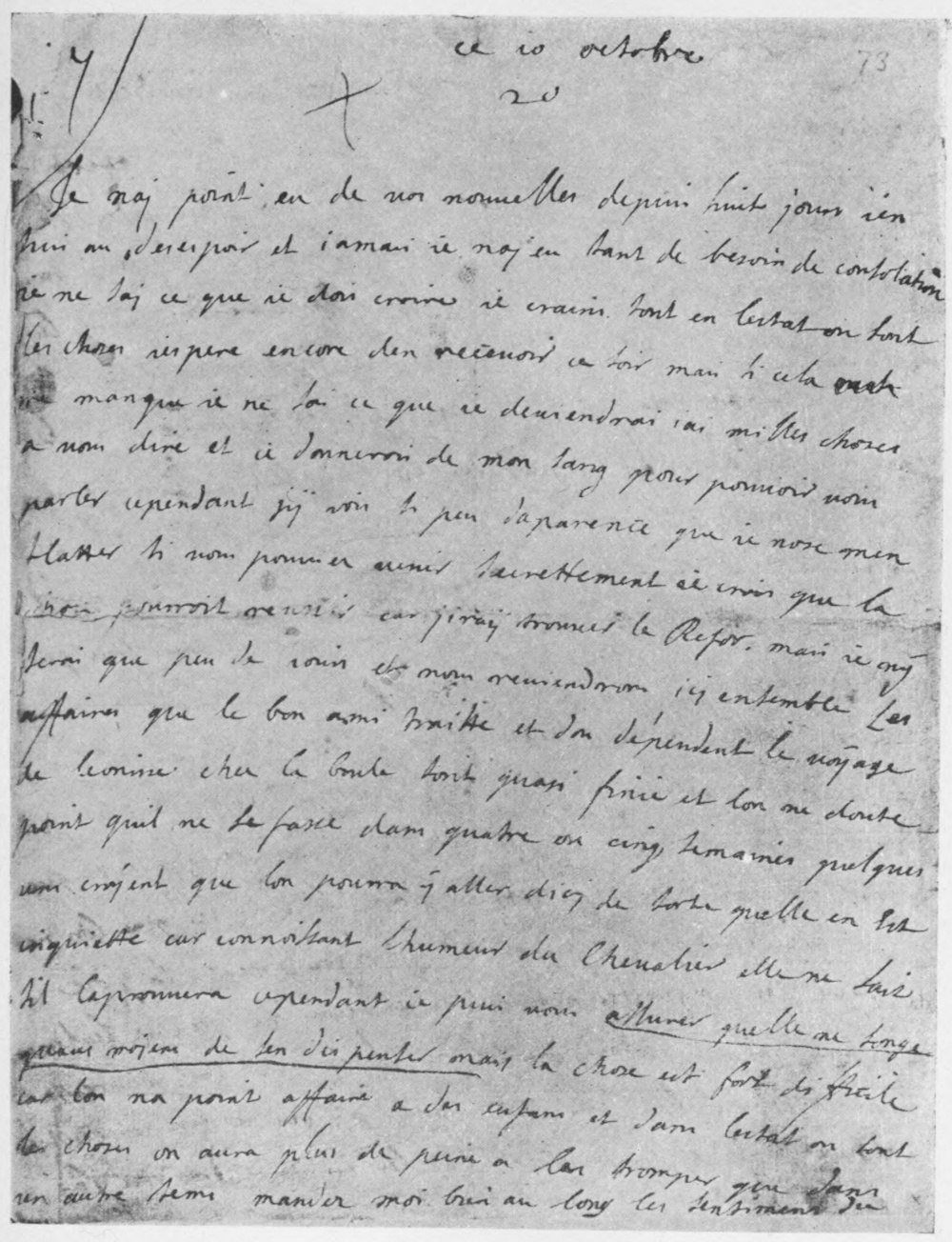

| Herrenhausen |

” ” 270 |

| |

|

| The Elector Ernest Augustus of Hanover. From an old print in the British Museum |

” ” 290 |

| |

|

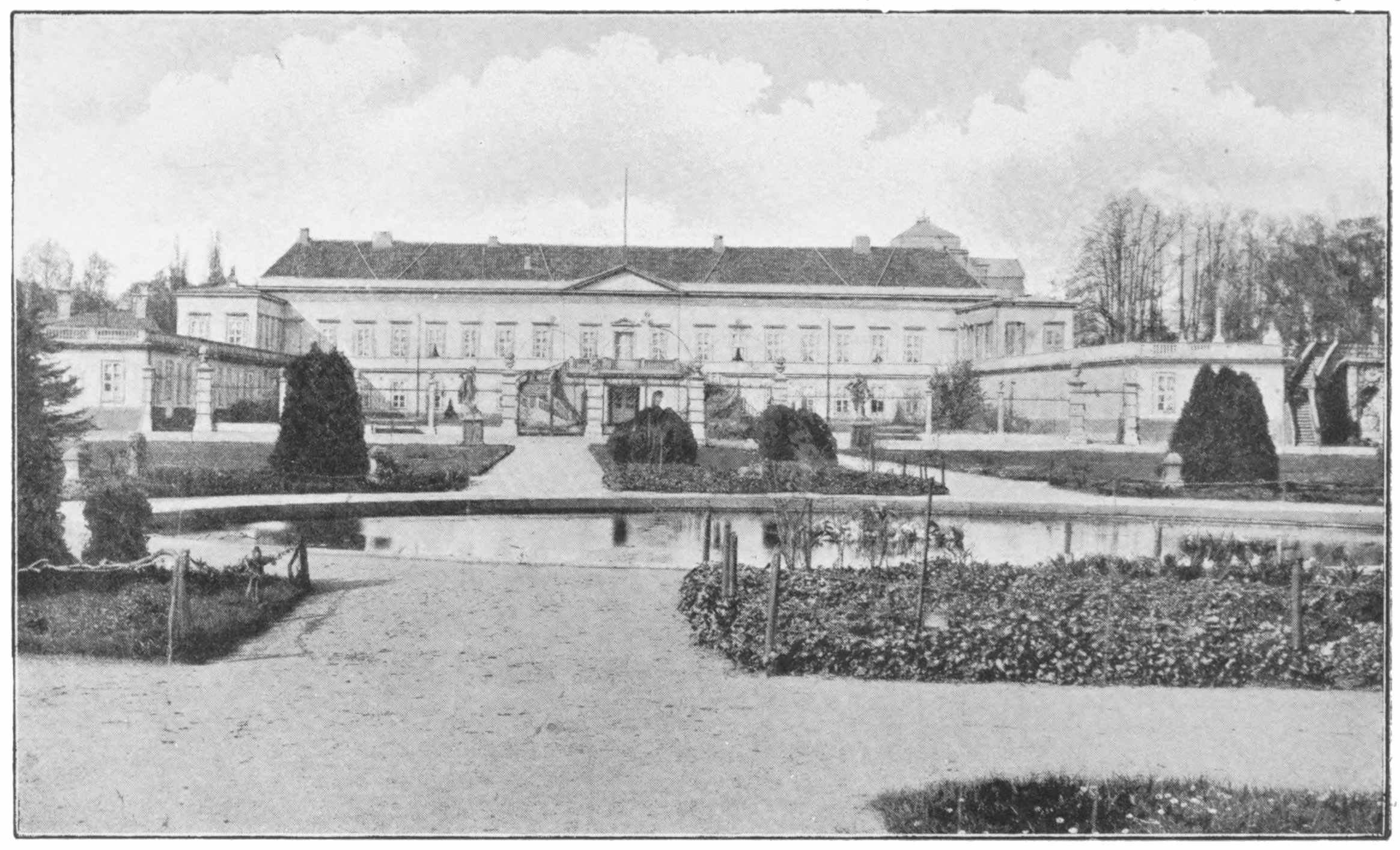

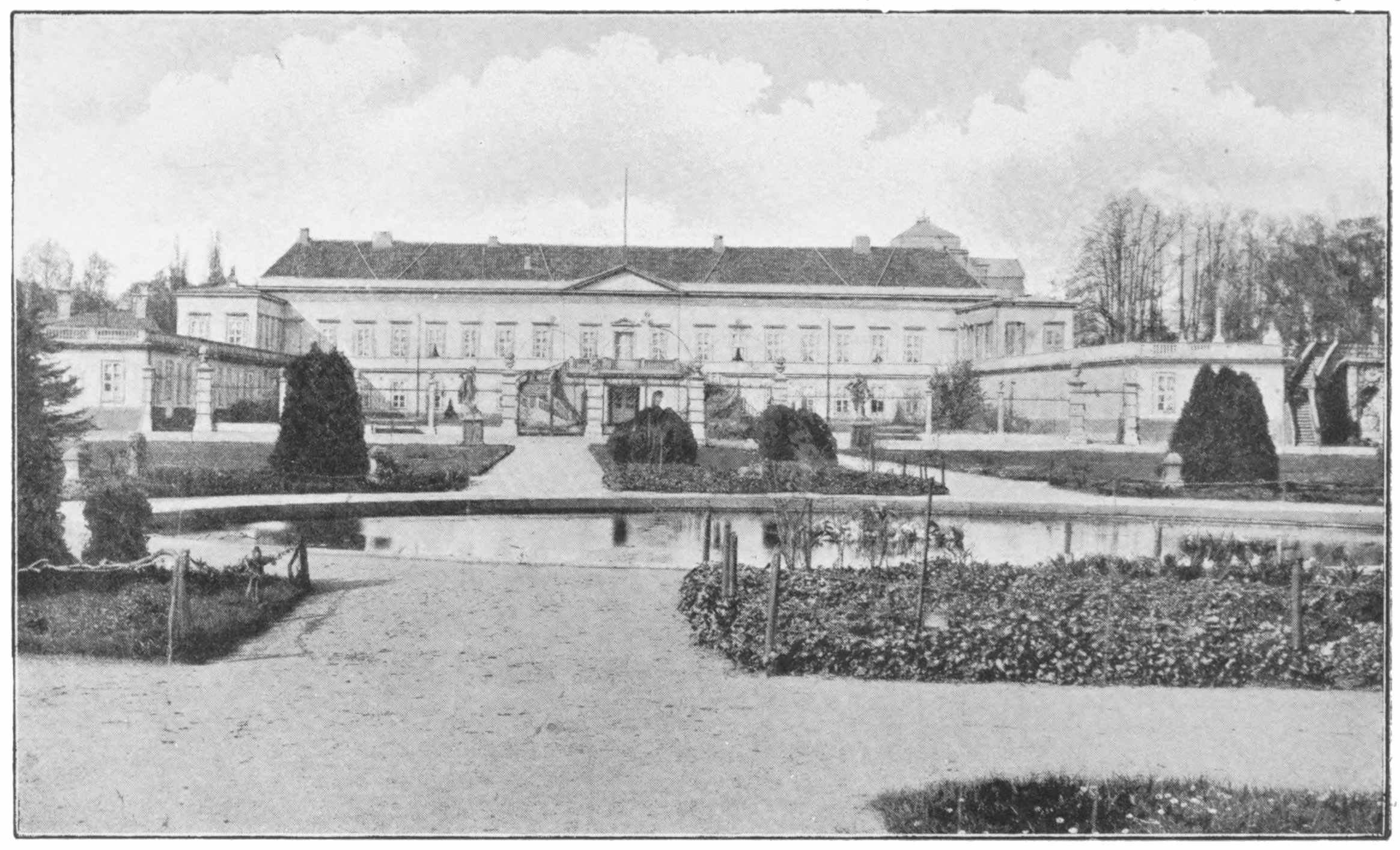

| The Murder of Königsmarck. From an old print |

” ” 348 |

| |

|

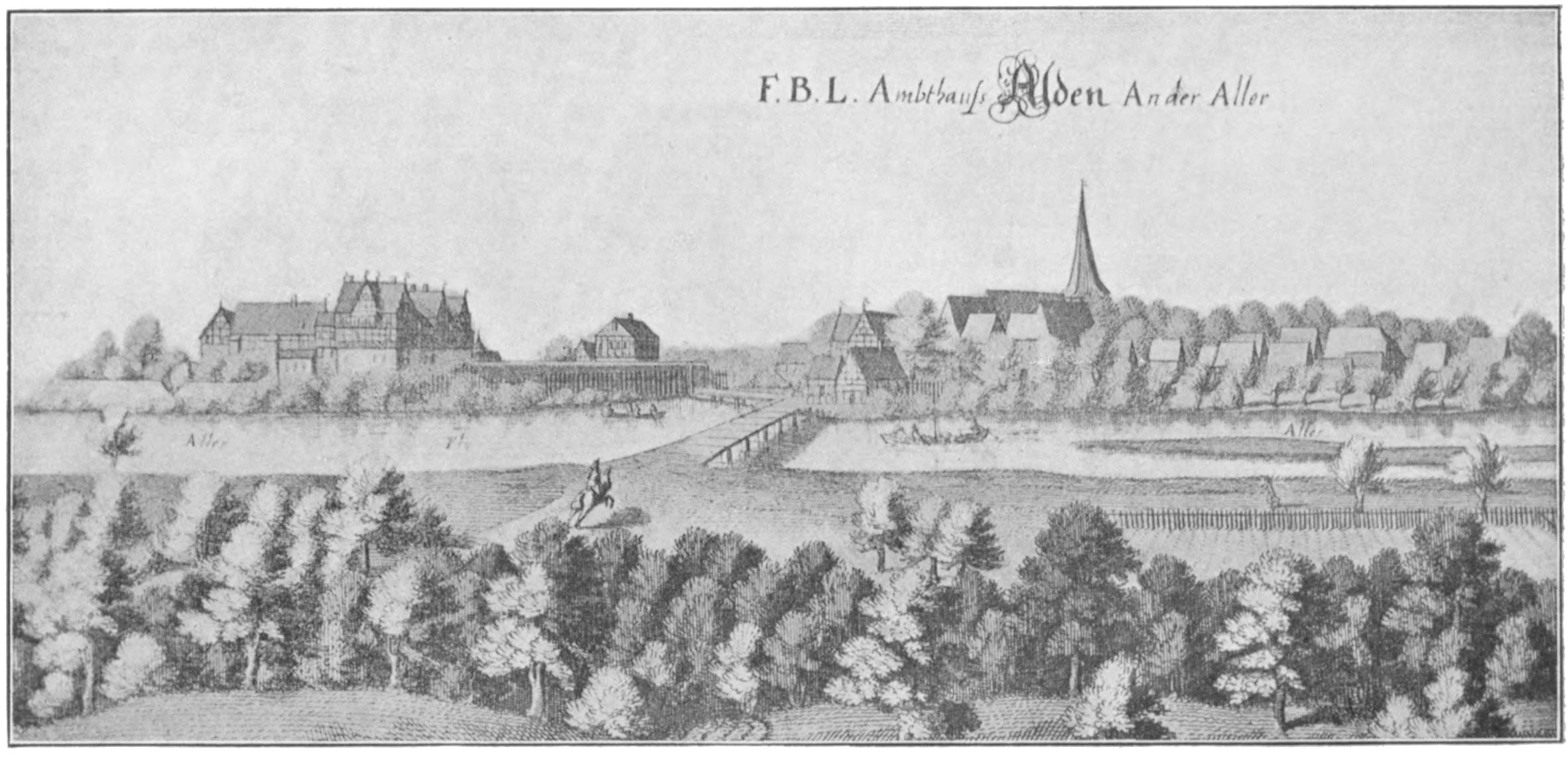

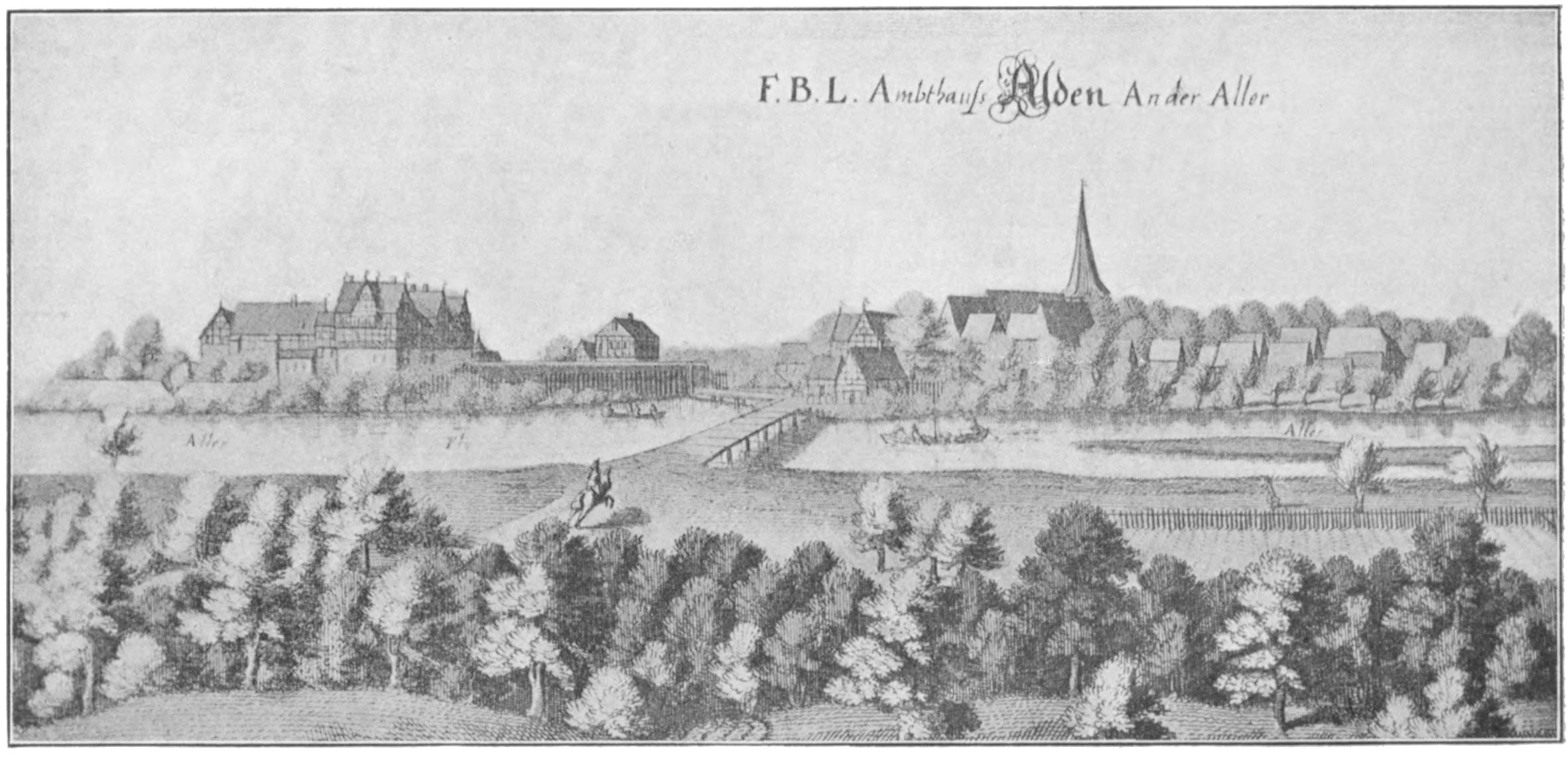

| The Castle of Ahlden as it was when Sophie Dorothea was Imprisoned there. From an old engraving in the Castle |

” ” 362 |

| |

|

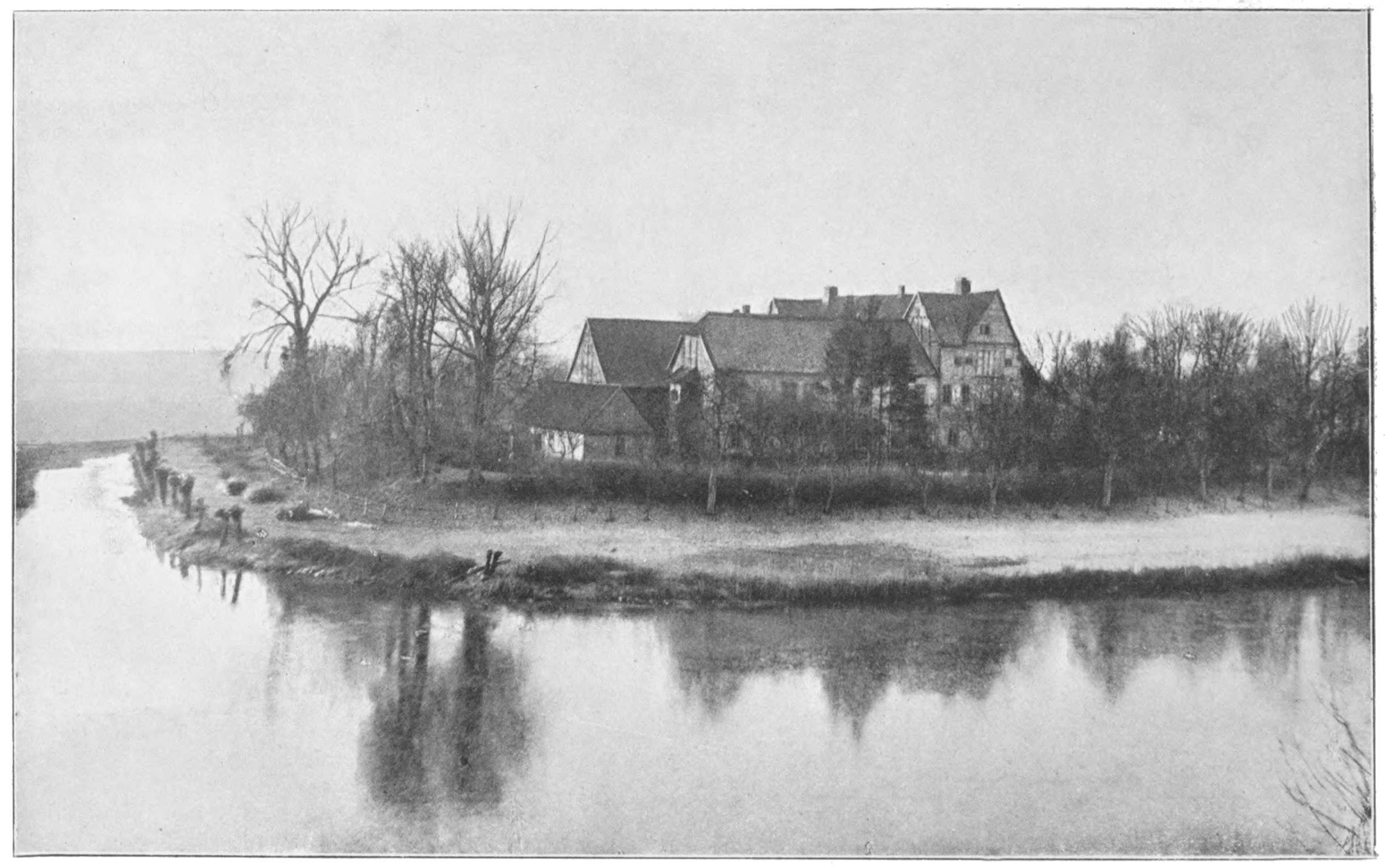

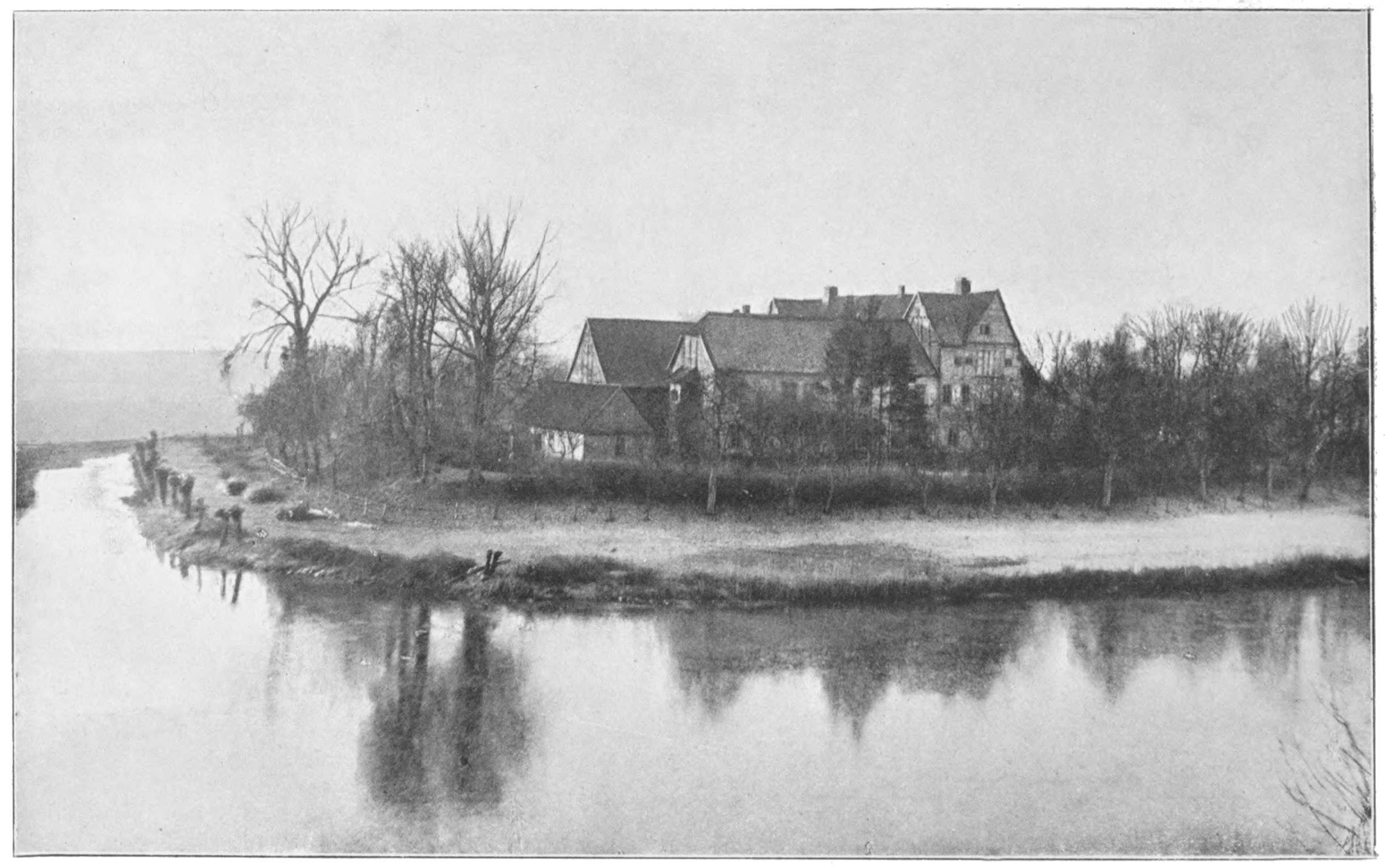

| The Castle of Ahlden as it is To-day |

” ” 376 |

| |

|

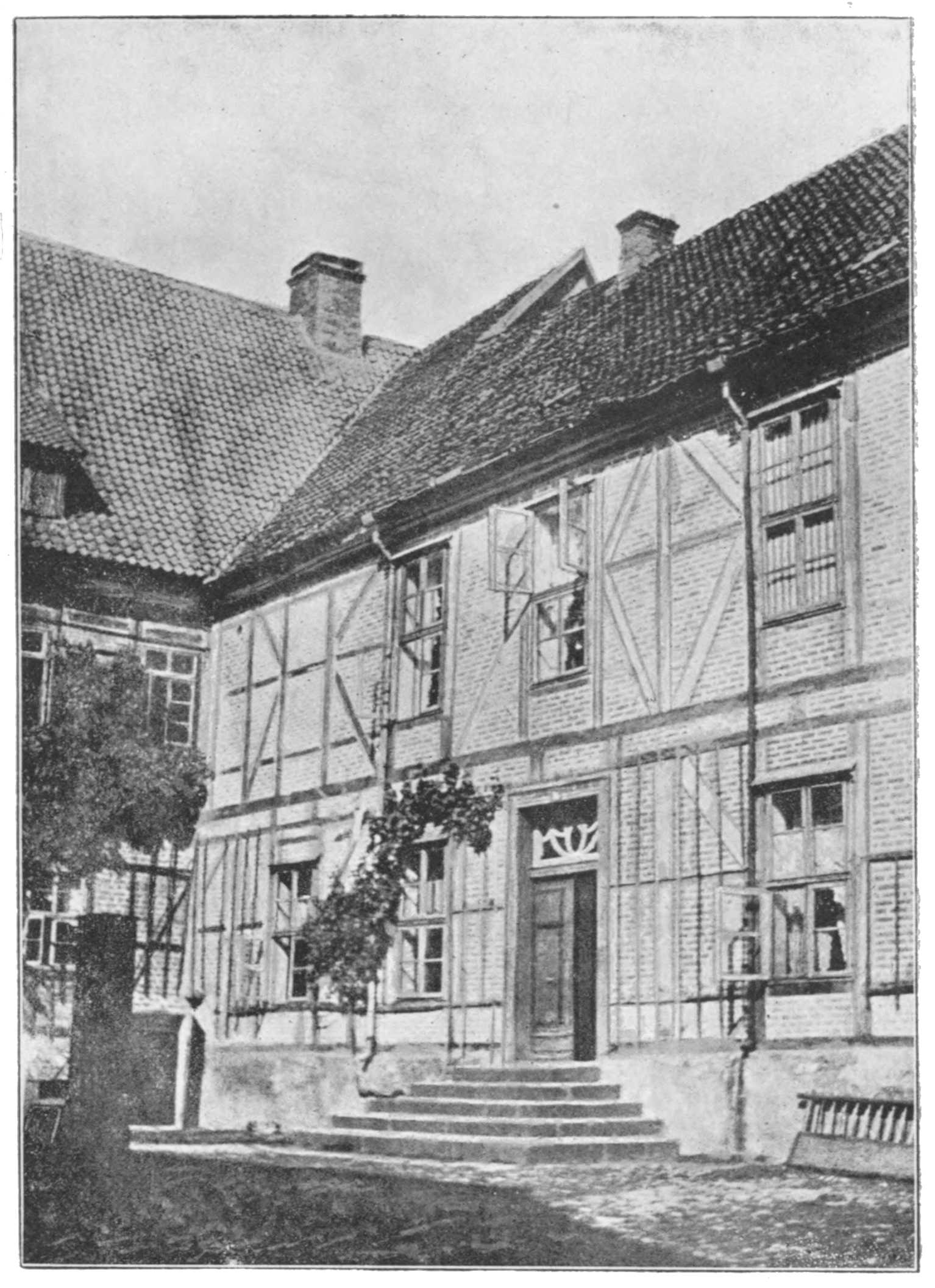

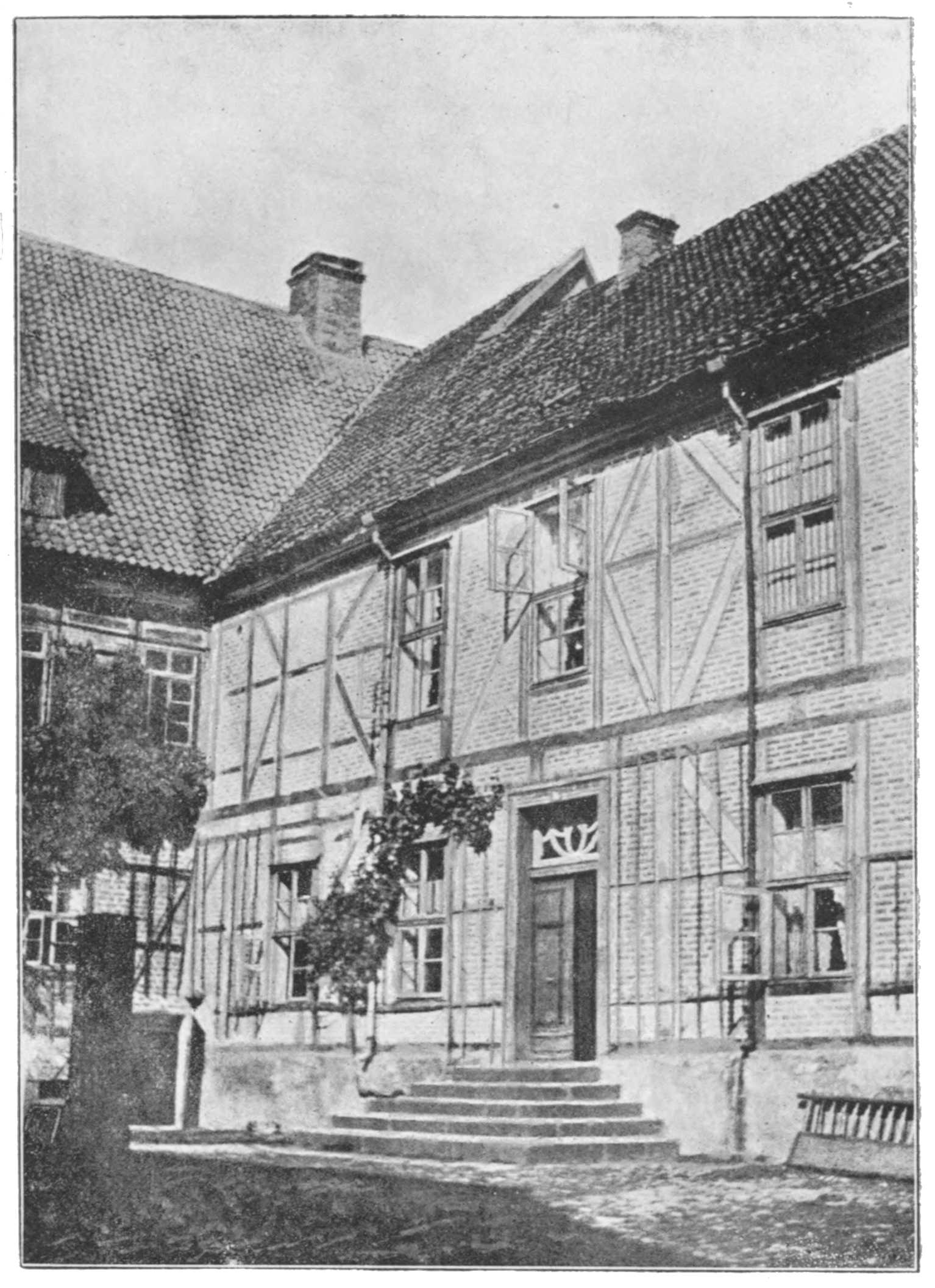

| Sophie Dorothea’s Wing of the Castle of Ahlden. From a photograph by the Author |

” ” 400 |

| |

|

| Sophie Dorothea, Second Queen of Prussia (Daughter of Sophie Dorothea and George I.). From the painting by Johann L. Hirschmann |

” ” 424 |

| |

|

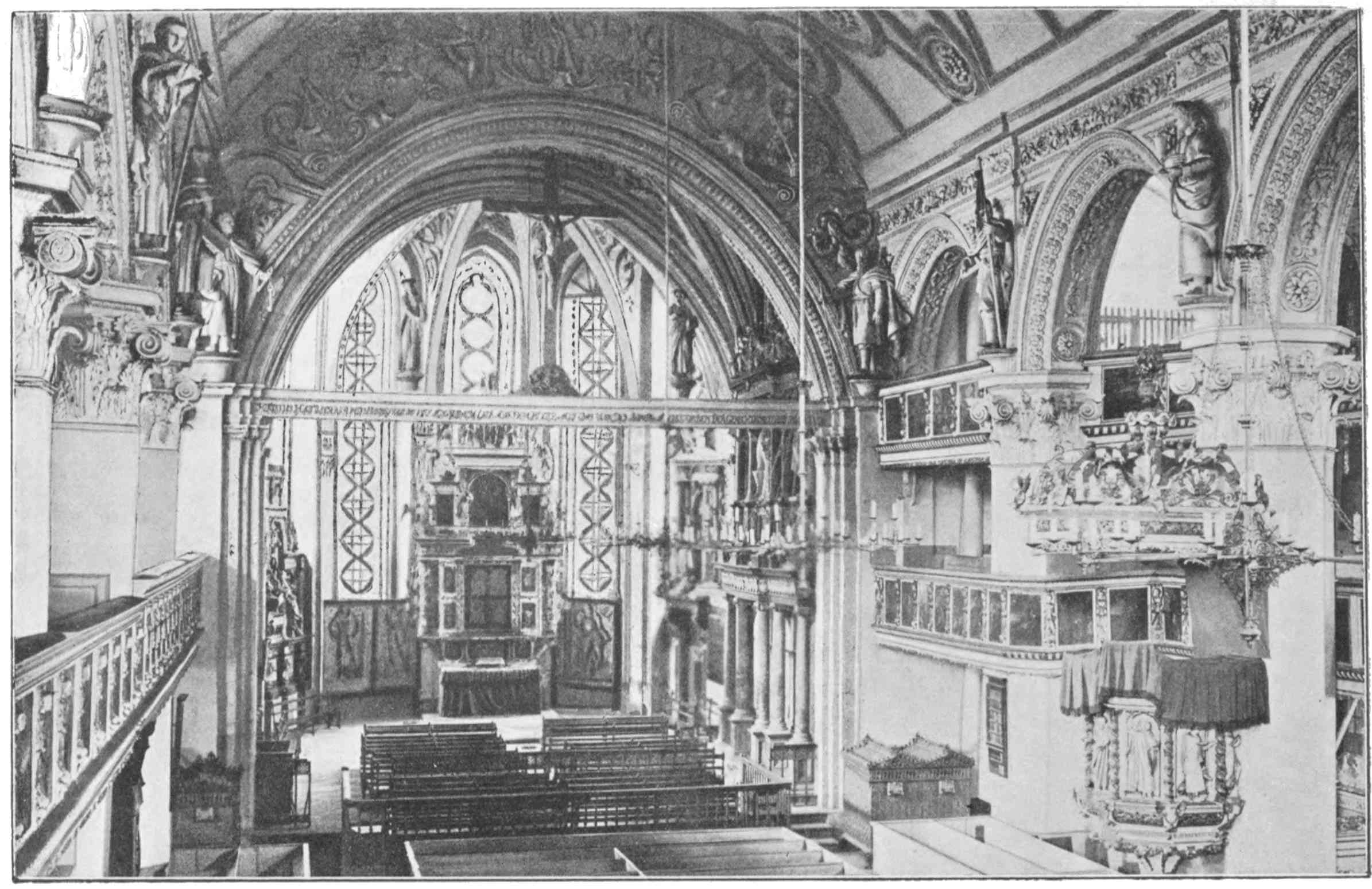

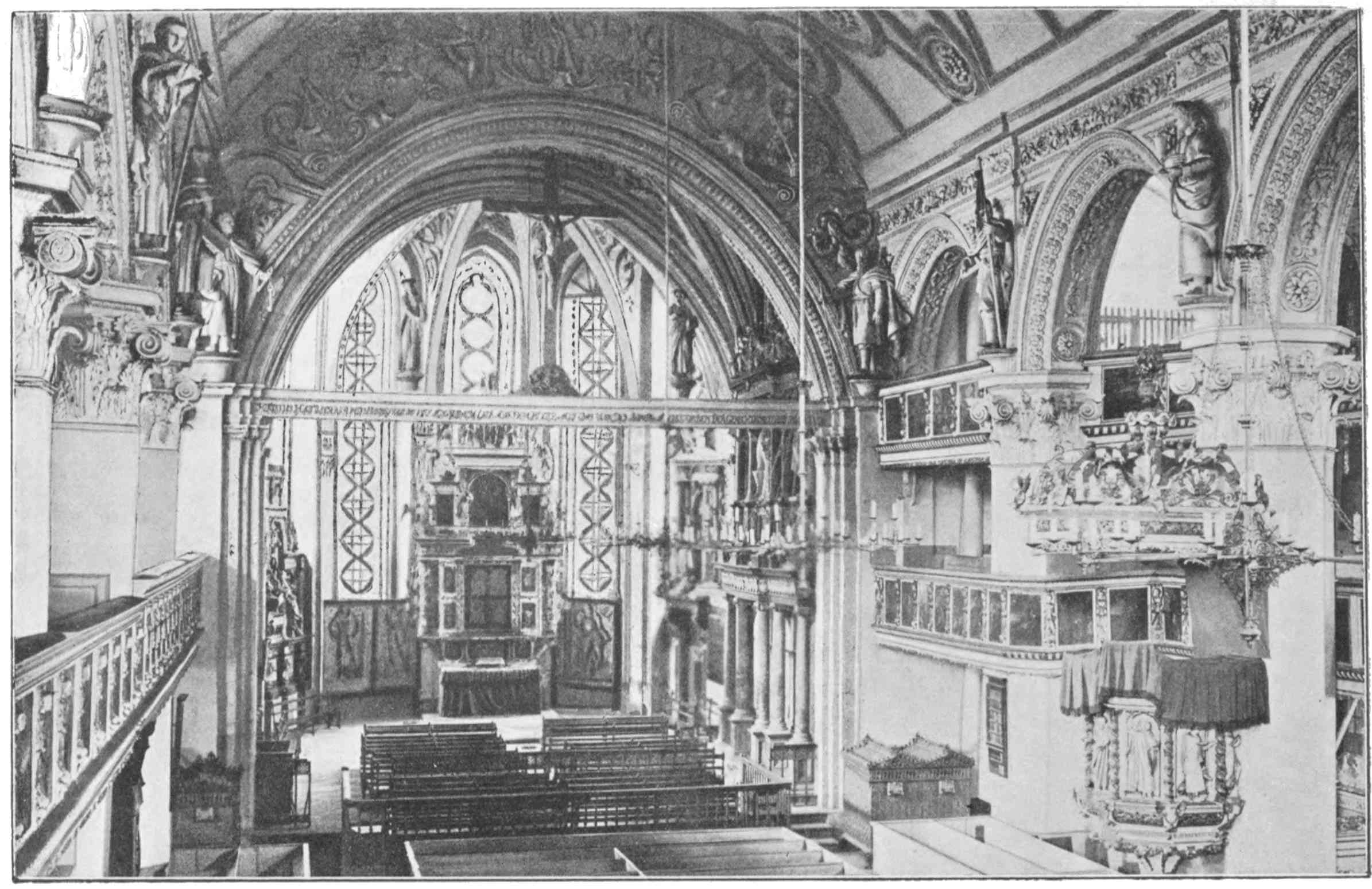

| The Church at Celle, where Sophie Dorothea is Buried |

” ” 438 |

| |

|

| The Castle of Osnabrück |

” ” 442 |

1

CHAPTER I.

THE ROMANCE OF THE PRINCESS’S PARENTAGE.

Life, like a dome of many coloured glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity.

Shelley.

Sophie Dorothea of Celle, the uncrowned queen of the

first of our Hanoverian kings, came of the ancient and

illustrious family of Brunswick, which was descended from

Henry the Lion, Duke of Bavaria and Saxony, who, it is

interesting to note, married Matilda, eldest daughter of

King Henry II. of England. It is not necessary to dwell

upon the glories of the House of Brunswick, but the immediate

ancestry of Sophie Dorothea may be of interest.

After the Treaty of Westphalia, which was somewhat

disastrous to the Brunswick princes who took part in the

Thirty Years War, this family was divided into two

branches, Augustus Duke of Brunswick representing one,

and Frederick Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg representing

the other.

On the death of Augustus, his territories were divided

amongst his three sons, with only one of whom we are

concerned, Duke Antony Ulrich of Wolfenbüttel. It is

necessary to mention him, as he played a not unimportant

part in the life of his cousin, Sophie Dorothea of Celle.

From this branch of the family the Dukes of Brunswick

are descended, and it gave another uncrowned queen to

England in the person of the unfortunate Caroline, consort

of George IV.

Frederick Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg died in 1649,

leaving the four sons of his brother, Duke George, his heirs.

Of these, the eldest son, Christian Louis, was given the

sovereign principality of Celle, then the most important;

the second son, George William, subsequently the father of

2Sophie Dorothea, was given the sovereign principality of

Hanover. The two younger sons, John Frederick and

Ernest Augustus, had no territory at first.

When the four ducal brothers, all young men, entered

upon their inheritance, changes took place in the sedate and

simple courts of Hanover and Celle. Hitherto they had

been typical of the petty German courts in the Middle Ages,

untouched as yet by foreign influences. According to

Vehse, at the schloss of Celle meals were served daily in

the great hall, at nine in the morning and at four in the

afternoon. The retainers were summoned to meals by a

trumpeter on the tower, and if they did not appear punctually

they had to go without. As they ate, a page went round

“bidding every one be quiet and orderly, forbidding all

swearing, and rudeness, or throwing about of bread, bones,

or roast, or pocketing of the same”. The butler was warned

not to permit noble or simple to enter the cellar; the squires

were allowed beer and “sleep-drinks,” but wine was only

served at the Duke’s high table. All accounts were carefully

kept, and bills paid weekly. The court was one big

family, and the Duke was the father of his people. But this

well-ordered household was in the days of the old Duke

Christian, a predecessor of the four young princes who now

divided the possessions of Brunswick-Lüneburg.

The eldest, Duke Christian, settled down to a fairly quiet

life at Celle; “his only fault,” we hear, “was drinking,” a

very venial offence in those days. But the second brother,

Duke George William, found life at Hanover unbearably

tedious. He had little liking for the stiff and monotonous

routine of his German court; the simple lives of his subjects

bored him, and their rude manners and coarse habit of

living disgusted him. Though all his life strongly anti-French

in his politics, he belonged to the newer school of

German princes and affected the society and fashions of the

French, so much so that on one occasion a French envoy

said to him at his own table: “But, MonseigneurMonseigneur, this is

charming; there is no foreigner here but you”. Though a

young man, George William had already travelled in Italy,

and acquired a certain polish of manners and superficial

refinement not usually to be found among German princes

of his time. The first use he made of his freedom was to

escape from the tedium of his uninteresting little principality,

3and, in company with his youngest brother, Ernest

Augustus, who was then his boon companion, and largely

dependent upon his bounty, he made another tour in Italy,

visiting Milan and Venice. At Venice, then at its zenith,

the brothers plunged into the delights and dissipations

which the gay city offered. George William formed an

intimacy with a Venetian woman, one Signora Buccolini,

by whom he had a son. For many years he was devoted

to her, and maintained her in considerable affluence; for,

with all his faults, he was of a generous disposition. But

the lady was of so passionate, jealous, and exacting a

temperament that at last she tired the patience of her

protector. After many quarrels he made an arrangement

by which he settled a sum of money upon the mother, and

took the charge of the boy’s education upon himself. This

was the final separation. He took back the young Lucas

Buccolini with him to Hanover, clipped his Italian name

into Bucco, or Buccow, and found him a place in his household.[6]

George William’s subjects did not appreciate these

frequent absences of their liege lord, nor did they approve

of the Italian singers and dancers and the Venetian son

whom he brought back with him to his prim little court.

They became exceedingly restive, and pointed out that

there was need of a duchess and an heir. Duke Christian

of Celle was unwed, and Duke George William of Hanover,

who was next in succession, was a bachelor too. Their

subjects, both of Celle and Hanover, considered this a

neglect of duty on the part of their princes, and, remonstrances

having no avail, at last the members of the state

in Hanover threatened to cut short George William’s

allowance if he did not marry forthwith. Moreover, knowing

his predilections, they intimated plainly that they

wished no foreign bride, and suggested that the Princess

Sophia, the orphan daughter of the luckless Frederick

Prince Palatine, ex-King of Bohemia (by the beautiful

Elizabeth, daughter of James I. of England), would be a

suitable duchess.

4The Princess Sophia was well past her first youth, and

was understood to be anxious to settle herself in life. She

was then living with her brother, the Elector Palatine of

the Rhenish provinces, at Heidelberg. The household was

not a happy one, for the Elector and his wife were leading

a cat-and-dog life, and Sophia’s lot, as a poor relative, was

hardly enviable. She was a healthy little body, decidedly

good-looking, though she had not inherited the beauty of

her mother, “The Queen of Hearts”. “My hair,” she writes,

“was light brown and in natural curls; my general appearance

gay and lightsome; my figure good, but not very tall;

my deportment that of a princess. I take no pleasure in

remembering all the rest, of which my mirror shows me

nothing left.” She had sharp wits and a sharp tongue, and

the life she had led, travelling about Europe in the poverty-stricken

court of Queen Elizabeth, had developed both to an

unusual degree. Yet notwithstanding the financial troubles

of her youth, “my spirits,” she continues, “were so high in

those days that everything amused me; the misfortunes of

my house were unable to depress them, although at times

we had to make repasts richer than Cleopatra’s, and nothing

was eaten at court but pearls and diamonds”. This is one

of Sophia’s figures of speech, for it is to be feared that the

pearls and diamonds had long since gone to the Jews. Despite

her poverty, or perhaps in consequence of it, Sophia

was inordinately proud of her birth, especially her English

ancestry, on which she was never tired of expatiating. At

one time she had been put forward as a suitable wife for her

first cousin, the Prince of Wales, afterwards Charles II. of

England, and with that view had been carefully trained in

the English language and English ways. The match fell

through, and so, in the after years, did many others, some

good, some indifferent, which had been projected for her by

her relations. As Sophia was very ambitious, the failure of

her matrimonial chances was a great disappointment to her.

She was now twenty-nine, and her good looks were somewhat

impaired by an attack of small-pox; she was therefore quite

ready to meet the husband whom the Hanoverians had proposed

for her, half way.

George William, seeing that his subjects’ minds were

made up, shrugged his shoulders and submitted to the

inevitable. If it had to be, Sophia would do as well as

5any other. He therefore started for Heidelberg, on the

way to his beloved Venice, accompanied again by his

brother, Ernest Augustus. Without ado he proposed for

Sophia’s hand, and she “did not at all hesitate to say Yes,”

as she admits in her autobiography. He made no pretence

to any affection, and she required none. A marriage contract

was drawn up and duly signed, with the single proviso

that the betrothal should not be made public for a little

time.

The business having been settled, George William

hurried on to Venice, and revelled in his brief spell of

freedom. But his approaching marriage hung over him

like a pall; he thought over the matter, and one morning

he came to the conclusion that after all he could not take

upon himself the restraints of matrimony with a woman for

whom he had not a particle of affection. The situation was

difficult, for, if he did not wed her, his subjects were determined

to reduce his income, and to the pleasure-loving

Duke this was an equally unpleasant alternative. In this

dilemma he bethought himself of Ernest Augustus, his

youngest brother, and suggested to him that he should act

as his substitute. All that his subjects wanted was an

heir, and with this Ernest Augustus would be able to

furnish them, through Sophia, as well as he. Ernest

Augustus was nothing loth to take his brother’s place—for

a consideration. He was favourably disposed towards

the Princess, with whom he had flirted in his youth;

they had met at the Hague and had played the guitar

together, but as he was a younger son, Sophia nipped the

flirtation in the bud. A deed was drawn up between the

two brothers, in which George William undertook to surrender

certain of his revenues, and bound himself not to

marry, so as to leave his inheritance and all his rights to

the brother who would act as substitute for him in the

matter of his intended bride and ducal obligations. Just

as the contract was signed the other impecunious brother,

John Frederick, came into the room, and, on learning its

contents, fell into a rage because the chance had not been

offered to him first; he tried to tear away the document

from Ernest Augustus, George William looking on with

amusement. This happy-go-lucky way of choosing a bride

was quite in keeping with the traditions of the House of

6Brunswick; an ancestor of these princes cast dice with his

seven brothers for a wife on somewhat similar conditions,

and won the prize—a princess of Hesse-Darmstadt.

The next thing was to acquaint the Princess Sophia

with the arrangement; that lady, having satisfied herself

that the terms of the agreement were equally advantageous

to her and her possible heirs, raised no objection to being

handed over like a bale of goods, and though her pride was

hurt she skilfully concealed her resentment. Her brother,

the Elector Palatine, glad to be rid of her and her sharp

tongue, told her that he thought she was better for the

change of brothers, a remark with which she agreed, adding

that “A good establishment is all I cared for, and if this

be secured to the younger brother, the change is a matter

of indifference”.

These negotiations from first to last took two years; in

September, 1658, the marriage was celebrated with some

pomp at Heidelberg, and in November the Duchess Sophia

took up her abode at Hanover, where she was the first lady

in the land, and treated with every honour. She was always

a great stickler for etiquette, and insisted on every tittle of the

respect due to her rank and illustrious ancestry. Curiously

enough, if we may believe her memoirs, no sooner was she

married to Ernest Augustus than George William became

attracted to her, thereby arousing the jealousy of her husband,

until she begged the elder brother, “for the love of God,” to

leave her in peace.

In 1660 her eldest son, George Louis (afterwards George

I. of England), was born at Osnabrück, and the arrival of

the much-wished-for heir increased her importance. The

following year Ernest Augustus succeeded to the bishopric

of Osnabrück,[7] and Sophia’s prospects were the more improved.

Meantime George William had overcome his belated

penchant for Sophia, if indeed it ever existed save in her

7imagination, and was gratifying his pleasure-loving soul by

making a tour of many cities. Among others, he went to

Breda, an exceedingly gay place at the end of the seventeenth

century, albeit money was somewhat lacking there.

It was the chosen home of political refugees, exiled princes,

and deposed monarchs, who kept up their spirits despite

their fallen fortunes, and maintained phantom courts on

nothing a year. Here Charles II. dwelt for some time in

his exile with many celebrated cavaliers; here, too, his

aunt, the Queen of Bohemia, had held her shadowy court;

here, too, was concluded the peace between England and

Holland. All these things contributed to the importance

and the gaiety of Breda; there were feasts, masquerades,

and revelries, and plays with after-suppers and dances.

Among the gayest of the gay was the Princess de Tarente,

an aunt of the Duchess Sophia, a German princess who

had married a French prince. One of her most cherished

protégées was Eléonore d’Olbreuse, only child of the Marquis

d’Olbreuse, a nobleman of ancient family, of Poitou. He

was one of the many French Huguenots who, after the

revocation of the Edict of Nantes, were persecuted by the

government of Louis XIV. As he would not recant, his

estates were confiscated, he was sent into exile, and found

an asylum in Holland.

Before the persecution of the Huguenot nobles Eléonore

d’Olbreuse had figured at the brilliant court of Louis XIV.,

where she was greatly admired for her wit and beauty.

She was endowed with an exquisite figure, dark brown

hair, regular features, and a brilliant complexion. At this

time she was in the first bloom of youth, and her loveliness

was only equalled by her sprightliness and charm of manner.[8]

George William met her at a ball at the Princess de Tarente’s,

and being of an amorous, though not of a marrying disposition,

he fell in love at first sight. He became a constant

visitor at the Princess de Tarente’s, and a closer acquaintance

with the accomplishments and graces of the bewitching

Eléonore only served to rivet his chains. He affected a

great zeal to perfect his French, and the fair Eléonore

willingly consented to give the good-looking Duke lessons,

8thereby offering fine opportunities for flirtation. What

progress George William made with the French language

is not recorded, but in the art of love there is no doubt he

made rapid advances, for after a few lessons in the conjugation

of the verb aimer, he avowed his passion in most extravagant

terms, and swore that he could not live without

her. He found that the citadel did not yield to the first

attack. Eléonore d’Olbreuse was of a very different calibre

to Signora Buccolini; she had only two available assets,

her beauty and her virtue, and she was well aware of the

value of both. She was not versed in the menue galanterie

of the court of the Grand Monarque for nothing. George

William was fervent in his protestations, prodigal in his

promises of devotion, and what was more to the purpose,

most liberal in his proposals as to settlements; but Eléonore

held firm. Her birth was noble, though not royal, and,

despite her poverty, she held that a French marquis of

ancient descent was not so very inferior to a petty German

prince. George William could not be expected to take

this view, for, though indifferent to the trappings of rank,

he, like all German princes, was inclined to over-estimate

his own importance. But he could not give her up; he

who had been accustomed to command in love was

now its humblest supplicant; he who was indolent, easy-going

in temperament, now developed an ardour and determination

altogether foreign to him; he who was slow

of speech now became more eloquent in the language of

love. Eléonore had worked a transformation. So infatuated

was he that he would willingly have married her

then and there but for the document he had signed when

the marriage was arranged between Ernest Augustus and

Sophia. Eléonore knew nothing of this arrangement, but

she positively refused to entertain any proposals short of

marriage.

ELÉONORE D’OLBREUSE, DUCHESS OF CELLE.

From a painting at Herrenhausen.

In this dilemma George William thought of a morganatic

marriage,[9] and offered handsome settlements. The

Princess de Tarente advised her friend to yield. The

Marquis d’Olbreuse put no pressure on his daughter; but

she was well aware of the straits to which poverty had

9reduced him, and could see that in his heart he favoured

the Duke’s suit. If she consented she would secure for

her father a comfortable provision for his declining years.

Eléonore, too, was really in love with George William;

but still she held back.

To bring matters to a climax, the Princess de Tarente

gave a brilliant entertainment in honour of the birthday of

her friend and protégée, when she presented her with a

jewelled medallion of her lover. The result seemed inevitable,

for she who hesitates is lost; when suddenly couriers

came hot-foot from Celle with the news that George William’s

elder brother, Christian, was dead, and his younger brother,

John Frederick, who owed him a grudge for having been

cheated out of Sophia, had seized on the castle of Celle and

established himself in the duchy. George William had to

post in haste to Celle to uphold his rights and turn out

the usurper, but before leaving Breda he placed a paper

in the hands of his beloved Eléonore, in which she found

that he had settled on her, in the event of his death, the

whole of his private fortune with the exception of a few

legacies.

It took some time for George William to arrange

things satisfactorily at Celle; but at last he persuaded

John Frederick to relinquish the duchy, and gave him

compensation, for his frequent absences had weakened his

rights. George William then became Duke of Celle, and

John Frederick succeeded to Hanover, Ernest Augustus

remaining Bishop of Osnabrück.

When affairs of state were settled satisfactorily George

William’s thoughts once more turned to love. But there

were many difficulties. He could not leave his duchy so

soon again, he could not return to Breda to see the object

of his affections; while she, on her part, refused all entreaties

to come to him. In this dilemma he confided in

his sister-in-law, the Duchess Sophia, of whose judgment

he had great admiration. Sophia sympathised, softened,

doubtless, by one of those little presents whereby George

William was in the habit of buying the complaisance of the

court at Osnabrück, and promised to see the affair through,

provided that nothing were done to impair her rights. It

could hardly have been a congenial task to Sophia, and her

jealousy showed itself early by her scoffing at Eléonore’s

10airs of virtue, which she declared were only assumed to

increase her value. But she was not one to allow sentiment

to stand in the way of substantial benefit. Sophia’s

prospects had again distinctly improved by the death of

Duke Christian. John Frederick was still unwed, and

likely to remain so;[10] and if she could tie George William

down to an amour without legitimate heirs, in the fulness

of time she or her children might reign not only at Osnabrück,

but also at Hanover and Celle. So the illustrious

Duchess Sophia, the descendant of kings, the great lady

of Osnabrück, wrote a specious letter to the poor exiled

Eléonore, asking her to come, assuring her of respect, and

offering her as a pretext the post of lady-in-waiting at her

court. Eléonore still hesitated. She was very proud and

very poor; but she was very much in love, and wearied

with importunities. The Duchess wrote again, even more

urgently. These attentions from one who was known

everywhere as a great princess flattered Eléonore’s pride,

and the prospect of joining her lover gratified her love.

She consented and came.

Eléonore was received with every mark of respect.

Sophia, accompanied by George William, met her at the

foot of the grand staircase of the castle. She was led up to

the Duchess’s own chamber, where coffee and salt biscuits,

an unusual honour, were offered her, and she was then conducted

to her apartments. No one could be more affable

than the Duchess; everything seemed straightforward, and

it is no wonder that Eléonore, a stranger in a strange land,

was outwitted. She soon found that she could not draw

back without compromising her reputation, so she yielded

to advice, not altogether reluctantly, and accepted at last

the left-handed marriage offered her. A contract was drawn

up, worded almost as if it were a regular marriage; but

carefully guarding the rights of Sophia, her husband, and

her children; and the signatures of Ernest Augustus and

Sophia were written under those of George William of Celle

and Eléonore d’Olbreuse. After the ceremony, which took

place in September, 1665, Eléonore was granted the title of

Madame von Harburg, so called from an estate of the Duke’s,

and her nominal place of lady-in-waiting was filled by her

11sister Angelica, whom she later married to the Comte de

Reuss.

In her memoirs Sophia declares that at first she was

agreeably surprised to find Eléonore a very amiable person,

of modest and even retiring manners, and she no doubt

thought she would be easily kept in her place—not a high

one. She soon found herself mistaken. For some months

after the morganatic marriage—the anti-contrat de mariage

Sophia contemptuously called it—Eléonore continued to

live in the household of the Duchess, and was not treated

with any great honour, and certainly not admitted to an

equality of rank. For instance, at meal-times she did not

take her place at the ducal table, and had to sit on a low

chair, without anything to eat, at a respectful distance from

Sophia and George William and Ernest Augustus, who ate

their food while Madame von Harburg looked on. But she

was allowed to remain seated when any princes were present,

and this was considered a great concession. Her pride was

much hurt at this etiquette, nor did the heavy living and

coarse manners of the German court appeal to her finer

tastes. In her interesting letters to her uncle she complains

that “her heart was sadly turned” by the enormous dishes

brought before the princely eaters, their menu consisting

chiefly of greasy sausages thrown in lumps on red cabbage,

and a farinaceous mass of ginger and onions. This was

washed down by cloudy, heavy ale, of which they drank

freely. “Now,” the Duchess Sophia would exclaim after

she had eaten her fill, mopping her face with a napkin,

“you may go, my dear, and help your ‘angelic’ sister with

her saucepans.” This was a jeer at the habit of Eléonore

and Angelica preparing for themselves a little meal after

the French cuisine in their dressing-rooms.

Madame von Harburg was not stinted in her establishment;

she was allowed a chariot drawn by six horses, but

she was never seen abroad with the Duchess Sophia or the

Bishop of Osnabrück. She was not, however, a lady content

with the second place, and as her influence with her husband

was great, and grew greater as his love increased, she had

little difficulty in persuading him to take her away with

him to the schloss at Celle, where she was safe from the

patronage of the Duchess Sophia and could develop on her

own lines. GeorgeGeorge William was glad to take up his abode

12at the capital of his duchy, and, thanks to his morganatic

wife, he abandoned his roving habits and settled down as a

model duke, making plans for the improvement of his castle

and the better government of his people.

After they had been a few months at Celle, Eléonore

set the seal on her influence with her husband by presenting

him with a daughter—Sophie Dorothea.

13

CHAPTER II.

THE PROGRESS OF ELÉONORE.

(1666-1676.)

Oh, were I seated high as my ambition,

I’d place this naked foot on necks of monarchs!

Walpole.

Sophie Dorothea was born in the castle of Celle on

September 15, 1666. On the anniversary of her birth two

hundred and thirty-two years later it chanced that the

writer visited Celle. It must have been on just such a

September morning that Sophie Dorothea was born, with

the sun blazing down on the yellow-washed walls and

shining into the chamber where the birth-bed was, with the

limes and silver beeches in the garden flecked with the gold

of autumn, and the blue-green reeds waving on the edge of

the sluggish moat. The fine old schloss had changed little

with the flight of centuries. The drawbridge and portcullis

had gone; but the moat, filled with water from the Aller,

still flowed dully about the walls, separated from them only

by a strip of garden. The great courtyard, with its high

yellow walls, timeworn sundial, and pyramid of cannon-balls

in one corner (doubtless the spoil of one of George

William’s many campaigns), even the flock of white and

purple pigeons fluttering down on the rough stones, all

seemed to breathe the spirit of the seventeenth century.

And looking up at the north wing, where Sophie Dorothea

was born, it required little effort of the imagination to

people again the deserted courtyard with lackeys and

squires, to conjure up the clatter of hoofs and the clank of

spurs, the bustle of congratulation, the arrival and departure

of messengers and doctors, all of which signified to the little

town of Celle that a daughter was born to the head of the

great House of Brunswick-Lüneburg, and, though they

knew it not, an ancestress to two of the mightiest monarchs

14of the modern world—the King of England and the German

Emperor.[11]

The little town of Celle, at least that part of it which

clusters around the base of the castle’s mighty walls, has

also changed little since the days of Sophie Dorothea. The

old brick church where the babe of that bright morning now

sleeps with her fathers remains the same. The triangular

market-place and the quaint little streets which branch off

from it, many of them narrow and irregular, bear the marks

of the flight of centuries. The old part of the town still

stands with houses dated from 1600 to 1700, having outer

beams carved with curious and uncouth mottoes. Celle,

though a fairly prosperous town, has not shot ahead like

Hanover. But in those days Celle, with its magnificent

schloss, the seat of the elder brother’s duchy, was a place of

considerable importance. It was a veritable Naboth’s vineyard

to Ernest Augustus and Sophia, his spouse, who, from

their little court at Osnabrück, looked towards it with

longing eyes.

The news of the birth of a daughter was not welcome to

them, but they consoled themselves with the thought that

the child was the fruit of a morganatic union, and, after

they had cracked a few coarse jokes, dismissed the subject

from their minds. But they were soon reminded rather

rudely. The infant was given the names of Sophie Dorothea,

and the christening was celebrated with much ceremony and

many festivities and rejoicings. Ernest Augustus angrily

15remarked that if the infant had been a princess instead of

only the daughter of his brother’s madame, they could not

have made more fuss about it; and that was true, for,

from the first moment Sophie Dorothea drew breath,

though in strict law she was a person of no importance,

expressly excluded from holding any rank at Celle, the

same honours were paid to her as if she had been heiress

to the duchy.

From this time onward the rift between the Duchess

Sophia and Eléonore gradually widened into an open feud.

As long as she had to think only of herself Eléonore had

borne patiently Sophia’s insults and humiliations; but now

that a child was born, she determined to spare no effort

to raise herself and her daughter to a recognised position.

She played her part with consummate skill. She had to

fight against not merely the uncompromising hostility of

Ernest Augustus and the jealous hatred of his Duchess,

but the forces of custom and precedence which bind the

petty German courts with an iron band. She had to beat

down the jealousy and prejudice against herself as an

alien and a stranger, and win the support and recognition

not only of her husband’s subjects, but of the

neighbouring princes, and even of the Emperor himself.

When we consider the forces against her, we are lost

in admiration of the courage, patience, and sagacity of

this woman, who year after year toiled for the end she

had in view, and at last found her efforts crowned with

success.

Success did not come in a night. It took Eléonore ten

years before she obtained the object of her desire—ten

years of constant effort; for her arch-enemy and rival, the

Duchess Sophia, was ever on the alert to check her moves

and foil her plans. One great advantage Eléonore had at

this time, she was sure of her husband’s love; and as George

William was as easy-going as his wife was energetic, and as

contented as she was ambitious, she soon managed to gain

a mastery over him—the mastery of a strong mind over a

weak one. Her next duty was to cultivate the arts of

popularity and win the good-will of her husband’s subjects,

no easy matter, for the prejudice against “the Frenchwoman”

and morganatic wife was strong in the little

German principality. But her tact and affability soon won

16her golden opinions in Celle. From the first she seemed

to take the townsfolk into her confidence; she drove about

the town with her infant daughter, radiant with bows and

smiles, and soon the inhabitants began to regard the little

one as their own child, and to be as jealous of her rights as

they were of their own. This devotion of the honest townsfolk

of Celle to Sophie Dorothea never wavered, but lasted

all through her life.

Not content with sowing the seeds of her child’s popularity

in her infancy, Eléonore used other means to endear

herself to her husband’s subjects. At her instigation Duke

George William proceeded to restore the old schloss on a

scale of considerable magnificence, taking care always to

employ local workmen. The little theatre[12] in the castle,

so long unused, was opened again for plays and musical

performances, and to these entertainments gentle and simple

were bidden, and seated according to their rank. Thus,

after many years, a lady was once more châtelaine at the

schloss of Celle, and again there might be said to be a court

there.

George William warmly seconded all these effort of his

wife, and so great was his love for her and the little child

that his one idea seemed to be how best to advance their

interests. The rival court of Osnabrück, queened over by

the descendant of kings, regarded all these innovations

and the “mock court” at Celle with open ridicule yet

concealed uneasiness. Sophia was presenting her husband

with a numerous family, and she was anxious that

17nothing should be done to prejudice the rights of her

offspring.[13]

Ernest Augustus held the security of his brother’s

promise not to enter into a legal marriage, and believed in

it implicitly; but he naturally asked himself to what end

Eléonore was working. He heard much of George William’s

boundless generosity to his morganatic wife, and he liked not

the diversion of his private property from what he thought

its proper direction, to wit, himself.

Within the next few years Eléonore bore her husband

three more daughters, but they all died in infancy. Her hope

of an heir, long cherished, despite the bitter derision of her

enemies, came to nothing, and Sophie Dorothea remained

the spoiled darling of her parents’ affections. So devoted

was her father to the child that the mother’s influence

grew day by day; and when the little girl was five years

old, George William, knowing that by his thoughtless contract

with Ernest Augustus he had shut out his wife and

daughter from all succession to his dominions, began to

purchase land to bequeath as he pleased. To this end he

bought five domains, and settled them upon Eléonore and

Sophie Dorothea, so as to make provision for them in case

of his death. But even this reasonable arrangement was

not carried through without a bribe to satisfy Ernest

Augustus, who would only tolerate his brother’s liberality

to his wife and daughter on the understanding that he

received a handsome commission for himself. This was

the first marked step in the progress of Eléonore, and a

little later she sounded the Emperor Leopold I. about the

possibility of legitimising Sophie Dorothea. The Emperor

18returned a favourable, if somewhat guarded, reply; it was

evident she could obtain her heart’s desire if she could

manage to pay the price. We find her, therefore, instigating

George William to send troops to help the Emperor in

sundry campaigns. This was done, and George William so

distinguished himself that the Emperor received him in

private audience, and most graciously inquired after his

“Duchess,” pretending not to know the true state of affairs.

The Emperor’s condescension reached the ears of the

Duchess Sophia, and the embers of her jealousy burst into

a blaze. Eléonore’s conduct was a model of wifely devotion;

so, as the Duchess Sophia could not bring any charge

against her after her marriage, she raked up some old

slander, and accused her publicly of having simultaneously

carried on two intrigues when she was at the court of France.

She represented her as a designing adventuress, who, while

doing her best to marry Colin, a page-in-waiting of Elizabeth

Charlotte Duchess of Orleans, tried to catch George William

as the bigger match of the two. These charges were not

very damaging or convincing, but malice went further. We

find the Duchess Sophia writing to her niece, the Duchess

of Orleans: “Never would any respectable girl have entered

the house of the Princess de Tarente, for, though she is my

aunt—to my intense disgust—she is not a person with

whom any one can live and remain clean. However,” she

added, “d’Olbreuse being a nobody, it did not matter

much.” George William treated the tale about the intrigue

with the contempt it deserved, but the statement that his

wife was “a nobody” seems to have rankled; so he and

his lady thought of a very poor means of defence. They

paid two thousand thalers to a French genealogist to make

out an elaborate family tree, to prove that Eléonore

d’Olbreuse was descended in an almost direct line from

the kings of France. The Duchess Sophia received the

pedigree with scorn and derision, and transmitted it to the

Duchess of Orleans, who, being malicious and a wit, made

out a caricature, in which she clearly showed that her head

cook was a descendant of Philip the Bold. Naturally these

tactics did not tend to smooth matters between Sophia and

Eléonore, who were now not on speaking terms, nor were

they successful in winning George William from the object

of his affections. Manlike, the more his wife was attacked

19the more he defended her; and Eléonore, who had her share

of vanity, was so upset and wounded by being thus flouted

that she became quite ill, and had to take a cure at Pyrmont,

then a fashionable watering-place, to restore her health.

George William was worried, too, and by way of a consolation

he purchased for Eléonore another and yet more

valuable estate, including the fertile island of Wilhelmsburg,

in the Elbe, near Hamburg. This he settled upon her for

life, and made arrangements for it to become, after her

death, the inheritance of Sophie Dorothea. Again Ernest

Augustus protested, and again he was bought off, this time

with a bribe of eighteen thousand thalers. But all the

same, the victory remained with Eléonore. If she could

not get the genealogy, at least she had substantial consolation.

The possession of a property like the island of

Wilhelmsburg naturally aroused comment, not only at

Osnabrück, but the neighbouring courts. It was regarded

as open evidence of Eléonore’s influence; she became a

person of consequence outside the little circle of Celle, and

all the German princes began to wonder what would happen

next.

They were not left long in doubt. A few months later

the Emperor Leopold sent to the court of Celle the letters

patent which granted the legitimising of Sophie Dorothea,

and gave the title of Countess of Wilhelmsburg to Eléonore.

If the memoirs of the time are to be believed, this Imperial

message came as a surprise even to George William, who,

though evidently pleased, looked askance at his Eléonore

and grunted, “Hum, hum!” as though he fathomed the

source whence the Imperial condescension sprang. He

was right, for the support which Eléonore had given to the

Emperor in influencing her husband to send troops to the

campaign, and a charming letter she had written to him,

had won the Emperor over to her side, and he graciously

acceded to her desire.

The next few years went by uneventfully. It seemed

to the outside world that Eléonore was resting on her

laurels, but in reality she was working for more. Meanwhile

Sophie Dorothea was growing up a lovely child, petted and

spoiled by her parents and the court of Celle. There is a

picture of her, painted about this time, at Herrenhausen,

the portrait of a beautiful child crowned with flowers and

20holding a great bundle of blossoms in her arms—a happy,

winsome, radiant face; and, making allowance for the

flattery of court painters, it is certain that she must have

been exceptionally lovely. The knowledge that the little

girl was to inherit a large fortune made rumour already

begin to find her a husband among the scions of the

nobility. Among Sophie Dorothea’s playmates in the

gardens of Celle was a handsome youth of some sixteen

years, Count Philip Christopher Königsmarck, son of a

wealthy Swedish noble. The youthful Königsmarck was

receiving his military training at Celle, and was staying

there for a few years. It was not unusual at that time for

a soldier to be trained in different courts and serve in

various campaigns, and so acquire a thorough knowledge

of warfare. Count Philip came of a family with a brilliant

military record. His father had held the office of Minister-General

of Artillery in the service of the King of Sweden;

his uncle, Count Otho William, was a marshal in the service

of Louis XIV., and at the court of the Grand Monarque

became acquainted with Eléonore d’Olbreuse. He was a

Huguenot like herself. This acquaintance probably formed

the link which brought his nephew to Celle. Eléonore,

though popular among her husband’s subjects, was devoted

to the land of her birth; she was always “the Frenchwoman,”

and was fond of appointing her compatriots to little

places in her husband’s court, thereby causing some small

jealousies.

There is little doubt that the boy and girl were thrown

together, and a friendship sprang up between them; but at

Sophie Dorothea’s age we can hardly suppose that there

was any deeper affection, though Königsmarck, for his part

(and he was older), afterwards avowed that he had loved

her from childhood.[14] At the most they could only have

been boy and girl playing at lovers. Count Philip, as we

have seen, came of a distinguished family, even in his

boyhood he was endowed with great personal beauty, and

he was known to be heir to considerable wealth. Sophie

Dorothea was an heiress too, and she was then far removed

from the rank of a princess. The possibility of a match

between the two was not so remote as might have been

21imagined—at any rate their names were linked together

even at that early period in the little court of Celle.

It is scarcely likely that Eléonore, Countess of Wilhelmsburg,

shared these views for her daughter—in fact, we know

that she looked higher. Among the neighbouring German

princes who had watched with benevolent interest the

progress of Eléonore was Duke Antony Ulrich of Wolfenbüttel,[15]

a cousin of George William, who later became co-regent

with his brother, Rudolph Augustus, of the duchy of

Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. He was a prince of considerable

talents and artistic and literary gifts, a restless spirit always

intriguing. He was a plain man, so plain that the Duchess

of Orleans called him “an ugly baboon”. He early noted

the great influence Eléonore had obtained over her slow,

easy-going husband. He disliked the Bishop of Osnabrück

and he knew of the Duchess Sophia’s hatred of Eléonore.

He was aware of the arrangement that had been made

between the two brothers as to the succession to the duchy,

but nevertheless he thought it would be a good thing if he

could manage to divert some of the wealth of the fat little

principality of Celle into his somewhat empty coffers. With

this end in view he paid a visit to the court of Celle, and

treated Eléonore with every possible respect; in fact, he

seems to have been genuinely impressed with her virtue and

talents, and this homage, coming from a neighbouring

prince, was grateful to Eléonore’s self-esteem, for she was

sensitive about her somewhat equivocal position. She

recognised in him an ally, and laid the foundations of a

friendship which lasted through life.

After an interval, Duke Antony Ulrich came again to

Celle, this time accompanied by his eldest son, Augustus

Frederick. He communicated to Eléonore his wishes that

his son should be betrothed to Sophie Dorothea, and she

was nothing loth. But he pointed out that there was a

difficulty, in that Sophie Dorothea was not a princess, and

so could not make a regular marriage with his son. The

way to overcome this obstacle was for George William to

legally marry Eléonore, and raise her to the rank of duchess,

22and by this means Sophie Dorothea would become a

princess, and equal in rank with Augustus Frederick.

This reasoning was very grateful to Eléonore, for it showed

the way to the goal of her ambition. She willingly agreed

to work with Antony Ulrich for this object, and they took

into their confidence a councillor named Schütz. Thus a

distinct party was formed at Celle opposed to the interests

of the Bishop of Osnabrück and in favour of those of

Wolfenbüttel. For this the Duchess Sophia was largely to

blame; she had so insulted and humiliated Eléonore that

she had thrown herself into the rival camp. George

William was so much under his wife’s influence that he

readily agreed to support her desire to become his duchess,

especially when his cousin and neighbour, Duke Antony

Ulrich, told him she was in every way worthy of the position,

and it was a reproach to him that he had not espoused her

as his legal wife long before. He also viewed with favour

the betrothal of Sophie Dorothea to Augustus Frederick, to

which this was an indispensable preliminary. Everything

was quickly arranged, and it was resolved to petition the

Emperor. He was already friendly to Eléonore, and when

her prayers were backed up by the powerful support of the

Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and her husband, they

were sure to be granted.

The news of this double event soon reached Osnabrück

and struck consternation into the hearts of Ernest Augustus

and his wife. The Duchess Sophia was beside herself with

rage, and wrote to tell the news to her niece, Elizabeth

Charlotte of Orleans. “We shall soon have to say ‘Madame

la Duchesse,’” she exclaimed, “to this little clot of dirt, for

is there another name for that mean intrigante who comes

from nowhere?” To which Elizabeth Charlotte replied:

“Nowhere? My dear aunt, you are mistaken, if you will

allow me to say so; she comes from a French family, and

therefore from a fraud.” Sophia also contemptuously

spoke of Eléonore as “the Signora,” professing to regard

her merely as the successor of Signora Buccolini, and she

profanely declared that she would rather George William’s

marriage were one before God than before man. But these

feminine amenities, like the Bishop’s protests, were unavailing;

and soon Ernest Augustus and Sophia arrived at the

conclusion that, as it was too late to prevent the mischief,

23the only thing remaining was to safeguard their interests

as closely as possible. A fresh agreement was drawn up,

lawyers and parchments were brought forth, and the

contract between the two brothers was debated and fought

out, clause by clause, like a bill in committee. The heckling

took many months and bore fruit in many documents.

The result of the controversy was at last summarised in a

document duly signed by Duke George William, the

Bishop of Osnabrück, and Duke Antony Ulrich of Wolfenbüttel.

The agreement was signed at Celle in May, 1676,

and its main clauses may be summarised as follows:—

Duke George William was allowed to “enter into

Christian matrimony with the high-born lady Eléonore von

Harburg, Countess of Wilhelmsburg”; and his daughter

Sophie Dorothea, “promised to wife to His Serene Highness

Augustus Frederick Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel,”

was to bear the title and arms of a princess by birth of

Brunswick-Lüneburg. But a clause was added: “Any

other children who may be hereafter born in this wedlock

must content themselves with the titles of Counts and

Countesses of Wilhelmsburg, and they can make no pretences

to the succession to the duchy, which is bestowed on

Ernest Augustus Bishop of Osnabrück and his heirs male”.

The unfairness of this clause is patent; but it was somewhat

modified by the fact that it was extremely unlikely

Eléonore would bear her husband any more children. The

Emperor’s assent was proclaimed with some ceremony; a

convocation of the deputies of the principality was then

assembled, and their agreement with the treaty duly notified.

When all the legal preliminaries were over, George William

led his morganatic wife of eleven years to the altar, and

espoused her with much pomp and solemnity before all

his court, his cousin Antony Ulrich, and the little Sophie

Dorothea, who must have wondered what it was all about.

Ernest Augustus and Sophia were not present at these

festivities, and they dissembled their ire as best they could.

“Ah!” exclaimed the Bishop to his court at Osnabrück on

the night of the marriage, “my brother’s French madame

is not a jot the more his wife for being his duchess; but she

hath a dignity the more, and therewith may madame rest

content.” The jibe was duly reported to the court of Celle;

but Eléonore did not feel its sting. She had reached the

24summit of her ambition; she was the acknowledged consort

of the sovereign of Celle; her name was associated with her

husband’s in the Church prayers; her child was ranked as

princess and betrothed to a prince of equal rank. As

Ernest Augustus had said, she could now afford to rest

content.

25

CHAPTER III.

THE WISDOM OF SERPENTS.

(1676-1681.)

Some rise by sin, and some by virtue fall.

Shakspeare.

The sun of Eléonore’s triumph had no sooner reached its

meridian than its radiance began to be overcast. The first

cloud was the death of the young Prince Augustus Frederick

of Wolfenbüttel, who was killed by a cannon-ball at the

siege of Phillipsburg a few months after his betrothal to

Sophie Dorothea. His death, though it seemed comparatively

unimportant, was destined to exercise an evil influence

over the fortunes of the House of Celle, and it snapped the

strongest band of union between the Celle-Wolfenbüttel

party. The child Princess was happily unconscious of her

loss. The betrothal was merely a matter of policy, to take

effect later; the courtship was yet to come; and when the

tidings came to Celle of the death of her betrothed she was

too young to mourn him.

At first the Prince’s death affected but little the entente

between the courts of Celle and Wolfenbüttel. Duke

Antony Ulrich continued the close friend of Eléonore; he

had another son, more nearly the age of Sophie Dorothea,

and he held him in reserve; for the hour of a fresh arrangement

was not yet, and other plans were in the air.

Meanwhile the little Princess blossomed into lovely girlhood,

the spoiled darling of her father’s court. She was

trained in all the accomplishments suitable to her rank, but

the more solid part of her education seems to have been

neglected, and with the promise of great beauty she early

developed a passion for admiration which lasted all her

life. Now that she was a princess her mother was careful

to keep her away from all suitors not of equal rank. The

early intimacy between the handsome young Königsmarck

26and Sophie Dorothea was broken off, and Königsmarck was

given a hint to leave Celle. He repaired to England to

finish his education, and he and the Princess did not meet

again for many years, and by that time she was a wife and

the mother of two children. Eléonore was justified of her

wisdom, for when Sophie Dorothea was scarcely more than

twelve years old her aunt, the Countess de Reuss, found in

a drawer of the little Princess’s bonheur du jour a love-letter

from a court page. The boy was banished for his audacity

into lifelong exile, and the governess, whose connivance was

responsible, was first imprisoned and then sent away in disgrace.

The news of this affair, which was but a childish

folly after all, got bruited abroad, and reached the ears of

the alert Duchess Sophia. That lady was never tired of

tirading against her sister-in-law, the “little clot of dirt”

as she invariably calls her in her letters to her niece, and

she seized on this incident to point her moral. “Is it not a

pity,” she wrote to the Duchess of Orleans, “that Ernest

Augustus and myself should have made such a blunder and

called to our court that ‘little clot of dirt,’ the more so that

we had at hand the Biegle, whom William liked well enough,

though she was not so fascinating as his French vixen, who

really is a splendid Stückfleisch? She would have done very

well, and at least have remained in her proper place. Never

mind, Sophie Dorothea will avenge us all; she is a little

canaille, and we shall see.”

This, to put it mildly, shows a loose moral view on the

part of the Duchess Sophia, to say nothing of the coarseness

of expression. Her prophecy about the little Princess did

not seem very likely of fulfilment then. The death of

Augustus Frederick of Wolfenbüttel left the field open, and

an alliance with the great House of Lüneburg-Celle was

eagerly courted. The beauty and wealth of Sophie Dorothea,

though she was only just in her teens, made her a desirable

bride, and it was no longer the sons of the nobility who

sought her hand, but princes of the reigning Houses of

Europe. A cousin of William of Orange, Henry Casimir

of Nassau-Dietz, was one of them; for another, the Duke

of Celle had almost arranged a match for his daughter with

Prince George of Denmark (afterwards the husband of Queen

Anne of England) when the Queen of Denmark interposed,

and, with much violence and many expletives, broke off the

27match. This lady had once received Eléonore at dinner, but

had refused her the kiss of honour. In revenge, Eléonore

had commented on the badness of the Queen’s cuisine; so

they were far from friends. Probably the Duchess Sophia,

who was very friendly with the Queen of Denmark, had a

hand in bringing about the failure of these negotiations, for

we find her writing: “Well done! Fancy a king’s son for