The Project Gutenberg EBook of Frank in the Mountains, by Harry Castlemon This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Frank in the Mountains Author: Harry Castlemon Release Date: January 8, 2013 [EBook #41802] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FRANK IN THE MOUNTAINS *** Produced by Greg Bergquist, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

PHILADELPHIA:

PORTER & COATES.

CINCINNATI, O.:

R. W. CARROLL & CO.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1868,

by R. W. CARROLL & CO.

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States,

for the Southern District of Ohio.

| CHAPTER I. | The Foot-race | 5 |

| CHAPTER II. | What Came of It | 20 |

| CHAPTER III. | Frank Learns Something | 34 |

| CHAPTER IV. | The Trapper a Prisoner | 48 |

| CHAPTER V. | Archie Finds a New Uncle | 66 |

| CHAPTER VI. | The Medicine-man | 85 |

| CHAPTER VII. | In the Mountains | 102 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | Frank's Friend the Grizzly | 123 |

| CHAPTER IX. | Adam Brent's Story | 142 |

| CHAPTER X. | Turning out a Panther | 159 |

| CHAPTER XI. | Frank in Search of his Supper | 181 |

| CHAPTER XII. | Adam Besieged | 200 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | Dick in a New Character | 219 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | A Ride for Life | 239 |

| CHAPTER XV. | Conclusion | 257 |

One sultry afternoon in September, about four weeks after the occurrence of the events we have attempted to describe in the second volume of this series, Frank and Archie found themselves comfortably settled in new quarters, hundreds of miles from the scene of their recent exploits. According to arrangement, they accompanied Captain Porter on his expedition, and in due time encamped a short distance from an old Indian trading-post, in the very heart of the Rocky Mountains.

The journey across the plains, from Fort Yuma on the Colorado to the head-waters of the Missouri, was accomplished without danger or difficulty. The expedition traveled rapidly, and the only incidents that occurred to relieve the monotony of the ride were a buffalo hunt and a chase after a drove of wild horses. On these occasions the cousins gained hearty applause from the trappers—Frank by his skill with the rifle, and Archie by his persevering but unsuccessful efforts to capture one of the wild steeds.

Had a stranger been dropped suddenly into the midst of the scenes with which the boys were now surrounded, he could scarcely have realized that he was miles and miles outside of a fence, and in the heart of a wilderness which but a few years before had been in undisputed possession of savages. The boys could hardly believe it themselves. If the fort, the trappers, and the Indian camp had been removed, Frank and Archie could easily have imagined that they were in the midst of a thriving farming region, and that they had only to cross to the other side of the mountains to find themselves in the streets of a prosperous and growing city. The country looked civilized. There were well-filled barns, rich fields of grain waiting to be harvested, and a herd of cattle standing under the shade of the trees on the banks of the clear dancing trout brook, which flowed by within a stone's throw of the house. There were wagons moving to and fro, between the barns and the fields, flocks of noisy ducks and hens wandering about, and Archie said he was every moment expecting to see a company of school-children come trooping by, with their dinner-baskets on their arms.

There was one thing that did not look exactly right, and that was the farm-house. It was built of sun-dried bricks, its walls were thick, and provided with loop-holes, and around it were the ruins of the palisade that had once served it as a protection against the Indians.

The farm-house was situated in the center of a delightful valley, which was surrounded on all sides by lofty mountains. In one corner of the valley, and in plain view of the house, was Fort Stockton, the trading-post of which we have spoken. Outside the walls a band of Indians, about a hundred in number, was encamped. They had come there to dispose of their furs, and were now having a glorious time among themselves, being engaged in various sports, such as running, wrestling, jumping, riding, and shooting at a mark. In a little grove between the house and the fort the trappers belonging to Captain Porter's expedition had made their camp, and the Captain himself sat on the porch, smoking his long Indian pipe, and conversing with Mr. Brent, the owner of the rancho. These gentlemen were old acquaintances and friends, having formerly been engaged in the fur trade together; and when the expedition made its appearance in the valley, Mr. Brent insisted that the Captain and his young friends should make their headquarters at his house, until they were ready to resume their journey. The boys willingly accepted the invitation—Frank for the reason that there was a well-filled library in the house, and Archie because he wanted to be near a new acquaintance he had made.

Close beside the stairs which led to the porch, Dick and old Bob lay stretched out on their blankets, listening to the yells of the Indians, and watching all that was going on in the camp; and, if one might judge by their looks and actions, they were not at all pleased with the state of affairs. Indeed, they had kept up a constant grumbling ever since they came into the valley, and had repeatedly declared that they had never expected to see the day that Indians would be permitted to come into a white settlement and carry things with so high a hand.

"Times aint as they used to be, Bob," said Dick, knocking the ashes from his pipe, and filling up for a fresh smoke. "When me an' ole Bill Lawson trapped in this yere valley, years ago, I never thought that I should set here, as I do now, an' let a hul tribe of screechin' varlets jump about afore my very eyes, without drawin' a bead on some of 'em. This country is ruined; I can see that easy enough."

"Dick is growling again," said Archie. "If he could have his own way, there wouldn't be an Indian in the world by this time to-morrow."

The cousins occupied an elevated position on the porch, from which they could observe the proceedings in the Indian camp. Near them stood the son of the owner of the rancho, Adam Brent. He was about Archie's age and size, only a little more thick-set and muscular; and with his brown, almost copper-colored complexion, dark eyes, and long black hair, might easily have passed for an Indian. His dress consisted of a hunting shirt of heavy cloth, buckskin leggins and moccasins, and a fur cap, which he wore both summer and winter.

Our heroes had made some alterations in their costumes since we last saw them. They had worn the Mexican dress while in California, because it was particularly adapted to the warm climate; but now they had discarded their wide pants for buckskin trowsers and leggins, although they still held to their sombreros, light shoes, and jackets.

The boys had spent but three days at Mr. Brent's rancho, but they were already famous, for Dick and Bob had never neglected an opportunity to relate the story of their adventures and exploits in California. When they visited the fort, the officers and soldiers looked at them as though they had been some curious wild animals; the trappers belonging to the expedition treated them with a great deal of respect; and their new acquaintance, Adam Brent, acknowledged that he had been greatly mistaken in the opinions he had formed concerning boys from the States. They arose still higher in his estimation before he bade them good-by.

When Archie spoke, Bob and Dick raised themselves on their elbows and looked at him.

"Yes, little un, I am growlin' agin," said the latter; "an' I reckon you'd growl too, if you knowed as much about them Injuns as I do. I'll allow that if I could have my way thar wouldn't be as many of 'em by this time to-morrow as thar are now, but I wouldn't like to sweep 'em out of the world by any onnateral means. I'll tell you what I'd do," he added, pointing to the grove in which the trappers were encamped. "Thar are twenty fine fellers layin' around under them trees, an' I like 'em, 'cause they're honest men, an' hate Injuns as bad as I do. I'd say to 'em: 'Boys, get up an' show them ar' red skins what sort of stuff you're made of!' They'd do it in a minit, an' be glad of the chance; an' thar'd be a thinnin' out of them Injun's ranks that would do your eyes good to look at."

"Perhaps some of you would get thinned out too," said Frank. "Those Indians are all well armed."

"I know that; but I, fur one, would be willin' to run the risk. I don't like to see 'em playin' about that ar way. When I walk through their camp, it is as hard fur me to keep from pitchin' into one of 'em as it is for a duck to keep out of the water."

"Let's go down there," said Archie. "I'd like to see what is going on."

Frank replied by picking up his hat; while Adam looked toward his father, who shook his head very decidedly. The cousins were a good deal surprised at this, and they had been surprised at the same thing more than once during their short stay at the rancho. Adam was never allowed to go anywhere, unless his father went with him. Mr. Brent kept watch of him night and day, and never appeared to be at ease if his son was out of his sight. He seemed to be afraid that some mischief would befall him unless he kept him constantly under his eye.

"You will have to go without me," said Adam, with some disappointment in his tone.

"Don't you get tired of staying about the house all the time?" asked Archie. "I'd dry up like a mummy, for want of some jolly exercise to stir up my blood."

"I do get very tired of it," replied Adam, "but I can't help it. It would be as much as my life is worth to go out of sight of this house. If I should go down to that camp, I might never come back again. I'll tell you a story before you leave us."

Frank and Archie would have been glad to postpone their visit to the camp, and to listen to the story then and there; but Adam left them, and entered the house. Dick and Bob accompanied them to the fort, and while on the way the boys talked over what Adam had said to them, and speculated upon the causes that rendered it necessary for him to be kept so close a prisoner; but that was a mystery, and would probably remain so until Adam saw fit to enlighten them.

After a few minutes' walk they reached the camp, and seated themselves upon a little knoll, under the shade of a spreading oak, to watch the games. The principal sport, among the younger members of the tribe, seemed to be running foot-races; and, in this, one youthful savage excelled all his companions. He was a tall, active fellow, apparently about Frank's age, as straight as an arrow, and very muscular. He easily distanced every one of his competitors, and finally he stepped up to the visitors, and fastening his eyes upon Frank, asked him if he could run.

"I reckon he can," replied Dick, before Frank could speak. "Fur one of his years he is about the liveliest feller on his legs I ever seed; an' I've met a heap of smart youngsters in my day, I tell you. You haint got no business with him. He would go ahead of you like a bird on the wing."

"Ugh!" exclaimed the young Indian.

"It's a fact; an' that aint all he can do, nuther. He can not only beat you runnin', but he can out-ride, out-shoot, an' out-jump you; an' he can take your measure on the ground as fast as you can get up."

The Indian listened attentively to all the trapper had to say, and then turned and surveyed Frank from head to foot. A white boy would have thought twice before selecting so formidable an opponent; but the Indian, evidently having great confidence in his powers, stepped back, and motioned to the young hunter to follow him—an invitation which Frank had no desire to accept. He would not have been at all averse to a friendly trial of speed and skill with the young warrior, if Dick had not been so lavish in his praises; but what if he should be beaten after all the complimentary things the trapper had said about him? The Indian had shown himself to be a great braggart. Whenever he won a race, he announced the fact by a series of hideous yells, that were heard all over the camp; and if he should chance to distance Frank, how he would crow over him!

"I believe I won't try it, Dick," said the latter.

"What!" exclaimed old Bob, in great amazement. "Are you goin' to set thar an' take a banter like that, an' from an Injun, too? I haint been fooled in you, have I? Come on, and show the red skins what you can do."

"Yes, go Frank," chimed in Archie, "and take some of the conceit out of that fellow. I know you can beat him. See how impudent he looks!"

Frank glanced toward the Indian, who stood patiently awaiting a response to his challenge, and meeting with a sneering smile, which told him as plainly as words that he was believed to be a coward, he sprang to his feet, and accompanied by his cousin and the trappers, followed the Indian toward the race-course. The latter kept up a loud shouting as he walked along, and Frank noticed, with no little uneasiness, that the Indians, old and young, abandoned their own sports and fell in behind.

"They 're goin' out to see the race," said Dick. "That boaster is tellin' 'em how bad he is goin' to beat you. I reckon he'll be about the wust fooled man them Injuns ever seed."

The prospect of a contest between a white boy and one of their own number, created quite a commotion among the savages; and by the time Frank and his companions reached the race-course, the village had been deserted. Among the spectators were the officers of the fort, and four white trappers who made their home among the Indians. In these last, if Frank had noticed them, he would have recognized old acquaintances, whom he had good reason to remember; but as they did not make themselves very conspicuous, he did not see them. They did not seem to care much about the race, but they appeared to be greatly interested in Dick and Bob, and their young friends. They looked at Frank, then held a whispered consultation, and one of them left his companions, and, mounting a small gray horse, rode off toward the mountains; while the others devoted their entire attention to Archie, whom they watched as closely as ever a cat watched a mouse. If Frank could have seen that horse, it is possible that there would have been an uproar in that camp immediately; and if Archie had known what the men were saying about him, and what they were intending to do with him, he would have wished himself safe back in California again.

When Frank reached the race-course, and looked back at the cloud of spectators that hung upon the outskirts of the village, his heart failed him; but it was only for a moment. It was too late to think of backing out, and with a firm determination to win the race, he began preparing for it by throwing off his hat and jacket, and tying his handkerchief around his waist. At this moment the principal chief of the band appeared upon the ground, and assumed the management of affairs. He was a very dignified looking Indian, stood more than six feet in his moccasins, wore a profusion of feathers in his hair, a red blanket over his shoulders, and was altogether the finest specimen of a savage the boys had ever met. Frank was very much interested in him; but before many hours had passed over his head, he had reason to wish he had never seen him.

"He is my beau ideal of a warrior," whispered Archie. "He looks exactly as I imagined all Indians looked before I knew as much about them as I do now. Isn't he splendid, Dick?"

"Sartin," replied the trapper. "I'd like to meet him alone in the mountains, an' show him how easy I can raise that har of his'n. Now, youngsters, if you are all ready, I am. I see that some of the Injuns are goin' to run the race too—jest to encourage their man, you know—an' I am goin' with you. Do your level best, now."

The race-course was about half a mile long. At the end of it was a tree which the runners were to double, terminating the race at the place from which they started. This the chief explained to Frank in broken English, and, after placing the rival runners side by side, and glancing up and down the course to satisfy himself that the way was clear, he raised a yell as the signal to start. Before his lips were fairly opened the race was begun.

No sooner had the chief's yell died away than the whole tribe took it up; and such a din as that which rung in Frank's ears during the next few seconds, he had never heard before. The yells did not express delight, but surprise and indignation; for their youthful champion was being left behind at the very commencement of the race. Frank took the lead at the start. The instant the signal was given, he bounded forward like an arrow from a bow, and was well under way before the Indian had made a step.

"Whoop!" yelled Dick, his stentorian voice ringing out loud and clear above the noise made by the excited savages; "if that wasn't well done may I never draw a bead on an Injun agin." The trapper was following close at Frank's heels, swinging along with an easy, graceful motion, and moving over the ground so lightly that he scarcely seemed to touch it. "Don't be in too big a hurry," said he, as Frank continued to increase his speed. "Save some of your wind for the finish. Come along, thar," he added, looking over his shoulder at the young Indian. "If you can't keep up, come here an' I'll tote you."

The savage, however, was not yet beaten. Quickly recovering from his surprise, and spurred on by the yells of derision which his friends sent after him, he exerted himself to the utmost; and before they reached the end of the course, he had overtaken Frank, and was running side by side with him; but he could not pass him. Indeed, it was quite as much as he could do to keep pace with him; while Frank was running well within himself, with plenty of power held in reserve, and ready, at a word from the trapper, to put on a fresh burst of speed, and leave his rival far in the rear. They reached the tree at the end of the course, swung round it like two flashes of light, and sped along the home stretch with unabated speed, the Indian beginning to feel the effects of his rapid run, and Frank apparently as fresh as when he started.

"He aint half the runner I thought he was," said the trapper, to encourage his young friend. "He's blowing his bellows already. I say, Injun! I reckon you're a little out of practice, aint you? The next time you banter a white feller to race with you, you had better pick out a good hoss to carry you. We haint begun to run yet. Let out just the least bit, youngster."

Frank "let out" a good deal; and although the Indian made desperate attempts to keep pace with him, he quickly left him behind, and finally flew past the place where the chief was standing, the winner by fifty yards.

"Whoop! Whoop!" shouted Dick, who seemed to be almost beside himself with delight. "I say, chief! If you've got any young fellers in camp, who think themselves something great at ridin', jumpin', throwin' the lasso, an' handlin' the rifle, jest trot 'em out. We've beat you runnin', an' now that we have got our blood up, we are ready for a'most any thing."

The issue of the race greatly astonished the Indians. Frank, as he passed the chief, was welcomed with cheers from the officers of the fort, the trappers, and from Archie, who hurried up to him, and shook his hand as though he had not met him for months; while the defeated runner was greeted with jeers and ridicule. No one, not even Dick, seemed more delighted than the chief. He approached the place where Frank was standing, patted him on the back, and looked at him with as much curiosity and admiration as he would have bestowed upon a steamboat or a locomotive, had one suddenly made its appearance in the valley. "Good boy!" said he, approvingly. "Ought to be Injun."

"He had oughter be a trapper," said old Bob. "A boy who can run like that is wasting his time by living in the States. If you would stay out here among the mountains fur a few years, Master Frank, you might get to be the leader of a band of trappers, or the captain of a wagon train."

Frank, flushed with excitement and exercise, turned to look for his rival. He saw him standing at a little distance from the other members of the tribe, leaning against a tree, with his arms folded, and a fierce scowl on his face. His defeat, and the reception he had met with from his friends, had made him very angry. Now and then some one jeered at him, but the majority of the tribe took no notice of him whatever. They seemed to think that an Indian who would allow a white boy to run faster than he did, was not worth noticing.

"You've give him a big back-set, Frank," said Dick; "an' my advice to you is to keep your eyes open as long as we stay in the valley. You've made an enemy of that feller, an' I know, by the squint in his eye, that he wouldn't think no more of slippin' a ball or arrer into you, than he would of eatin' a piece of jerked buffaler. You see these Injuns are mighty wild yet; they haint been whipped enough to make 'em tame. They seem friendly enough now, but they've no great love fur white folks; an', if they thought they could do it without bringin' harm to themselves, they would massacree the last one of us afore they are an hour older. I don't like the way they act, any how; an', mark what I say, youngster, we're goin' to have trouble with 'em. Bars an' buffaler! What's up now?"

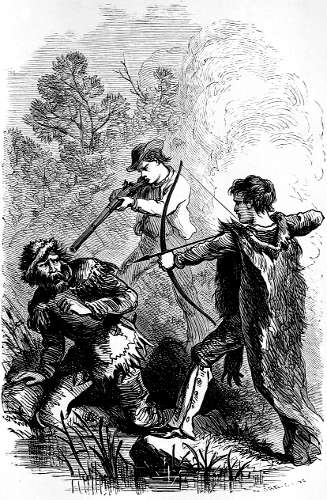

The trapper was not long in finding out what was up, and neither was Frank. The young Indian, smarting under his defeat, and stung by the ridicule of his friends, had determined to retrieve his lost reputation. If he could not distance the white boy in a foot-race, he could perhaps beat him at something else, and so regain some of the laurels that had been wrested from him. He resolved to try it; and before Frank knew what was going on, the Indian stepped up behind him, and clasping his sinewy arms around his body, lifted him from his feet, and attempted to throw him to the ground. He took Frank by surprise, and caught him in such a manner that his arms were pinned to his side, thus placing him at great disadvantage.

"That's a cowardly way of doing business," shouted Archie, indignantly. "Why don't you give a fellow a fair chance? If he throws you, Frank, get up and try it again, for this won't be a fair test."

"He aint a goin' to be throwed," said the trapper. "That Injun will have to eat a heap of dried buffaler meat afore he can get Frank off his pins. Show him what you can do, youngster."

The young Indian speedily found that he had got his hands full, and that one hundred and sixty pounds of bone and muscle was an exceedingly unhandy weight to manage, especially when backed up by such skill and courage as Frank possessed. The latter positively refused to be thrown. The Indian, although he exerted himself to the utmost, could not force him from an upright position, for Frank, like a cat, always fell feet foremost. The excitement ran high as the young athletes struggled over the ground. Yells of delight and encouragement from the friends of both parties arose in deafening chorus, and Indians, officers, and trappers pushed and elbowed one another to obtain a position from which they could view the contest, which was decided in Frank's favor much more easily and quickly than the foot-race. After a few ineffectual attempts, he succeeded in freeing his arms; and catching the Indian around the body, broke his hold in an instant, and sent him headlong to the ground. The ease with which it was done astonished every one who witnessed it, and had a very chilling effect upon the ardor of the Indian, who jumped to his feet and stole off toward the village, looking exceedingly humiliated and crestfallen.

Frank, although he was proud of his victories, as any other boy would have been under the same circumstances, was almost sorry that he had allowed himself to be persuaded into contesting the Indian's claims to superiority. The expression he saw on the face of his rival told him that he was almost beside himself with fury; and Frank did not relish the thought that any one, even an Indian, whom he never expected to see again, should be angry at him for any thing he had done. He would have been astonished had he known what was to be the result of this morning's work. He was destined to see and know a great deal more of his rival, and also of the chief, whose interest in him now seemed to be redoubled; and this foot-race and wrestling match were the preludes to more than one exciting and disagreeable event that was to happen before he saw California again.

"Youngster, I am proud of you," exclaimed Dick, seizing Frank's hand, and giving it a grip and a shake that made the boy double up like a jack-knife; "but I say agin, that you had better keep a good lookout as long as them red skins stay about here. They're mighty onsartin, an' thar's no knowin' what they may do. Let's go home."

Frank put on his jacket and hat, and followed the trappers toward the house. He found Captain Porter, Mr. Brent, and Adam impatiently awaiting his arrival, for they had witnessed the race, and were anxious to know all about it. Dick, as usual, acted as spokesman; and Frank afterward said that he had not the least idea how swift a runner he was, or what an astonishing victory he had won, until he heard the trapper relate the particulars. If one might judge by what he said, Frank could beat any mustang in Mr. Brent's stables.

The listeners were all as highly elated as the trapper. Adam shook his new friend warmly by the hand, and the Captain laughed until he shook all over like a big bowl of jelly. Frank was once more a hero, and during the next half hour the race formed the chief topic of conversation; but even that grew tiresome at last, and the cousins, who could not remain long inactive, strolled off toward the camp of the trappers. Shortly afterward they emerged from the grove, mounted on their horses, and rode toward the mountains.

They had not decided where they were going, or what they would do; but, as far as the sport they were likely to meet with was concerned, that made little difference. In that wilderness they could not run amiss of something to excite and amuse them, let them go in what direction they would. If they preferred quiet sport, there was plenty of it to be found in the brook that ran through the valley. No city fishermen, with their jointed poles and artificial flies, had ever invaded this retired spot; and having no enemies except an occasional fishhawk, and a few straggling Indians and trappers to contend with, the trout had increased and multiplied until the stream fairly swarmed with them. If they decided to try their rifles, and engage in some more active and exhilerating sport than fishing, there were the mountains, which abounded in game of every description. If they felt so inclined they might, within less than half an hour, make the acquaintance of a panther or two, or renew their intimacy with the grizzlies. Archie did not deny that he was afraid of grizzly bears, and, for that reason, he thought it best to give them and their haunts a wide berth. He picked out a shady spot on the bank of the brook, and said he would stop there and try his luck at fishing; while Frank, who had heard that elk were plenty in the mountains, thought he would ride farther on and see if he could find one. "I shall not go far," said he, "for not being acquainted with the country, I might get lost; and I shouldn't like the idea of being obliged to stay in the mountains all night."

"Nor I either," replied Archie; "and for that reason I am going to stay here, where I know I am safe. Hold on a minute, and see me catch a fish."

Archie dismounted from his horse, and after tying the animal to a neighboring tree, cut from the thicket a long, slender sapling, which, on being stripped of its branches, promised to answer the purpose for which it was intended, and to pull out a trout as well as any twenty-five-dollar rod. Then he produced a fish-line from his pocket, and in a short time his pole was rigged. The bait was dropped carefully over the bank, and no sooner had it touched the water than it was seized by a ravenous trout, which found itself struggling on the ground in a twinkling.

"He is rather larger than those we used to catch about Lawrence, isn't he?" said Frank. "Now, if I am fortunate enough to knock over an elk, we'll have a supper such as people in the cities do not often enjoy."

Archie, intent upon securing his fish before it floundered back into the water, did not reply; and when he looked up again, his cousin was out of sight.

Frank urged Roderick into a gallop, and soon had left the valley behind, and was threading his way through a thickly-wooded ravine that led into the mountains. Here he became more cautious in his movements, and allowed his horse to walk leisurely along, while he peered through the trees on every side of him, in the hope of meeting with one of the numerous elk which every evening descended from the mountains into the valley to crop the grass and slake their thirst at the brook. His chances for a shot at one of these animals would have been greatly increased if he had left his horse behind; but grizzlies were plenty, and Frank did not like the idea of encountering one while on foot. On this particular evening, however, the mountains seemed to be deserted. Not a living animal of any description did he see, during the hour and a half that he continued on his course up the ravine; and becoming discouraged at last, he turned Roderick about and rode toward the rancho.

"I wish I could see just one squirrel," said Frank, who, like all young hunters, considered it his duty to empty his gun at something before he returned home. "What's that?"

A slight movement in the bushes in advance of him attracted his attention; then a twig snapped behind him, and a yell, so sudden and appalling that it made Frank's blood run cold, echoed through the ravine; and before he could look about him to see what was the matter, he was pulled from his saddle and thrown to the ground. In a twinkling his rifle was torn from his grasp, his hands bound behind his back, and he was helped to his feet to find himself surrounded by a party of Indians in war costume.

Frank was as frightened as a boy could be. Amazed at the suddenness of the assault, he gazed in stupid wonder at the savages, winked his eyes hard to make sure that he was not dreaming, and looked again. But there was no dreaming about it—it was all a reality; and as he stood there powerless among his captors, and looked at their glittering weapons, and painted, scowling faces, all the stories he had heard the trappers relate of their experience among the Indians, came fresh to his memory. He recognized one of the savages, and that was the chief. His blanket and buckskin hunting shirt were gone, he wore the tomahawk and scalping knife in his belt, his face was covered with paint, and altogether he looked fierce enough to frighten any boy who had never seen Indians in war costume before.

Frank took these things in at a glance; and while he was wondering what object the Indians could have in view in capturing him, and what they intended to do with him, he was trying hard to summon all his courage to his aid, and to appear as unconcerned as possible. If there had been any hostile Indians in that part of the country, he could have understood the matter; but he had been told that they were all friendly.

"Look here, chief," said he, "I'd like to know what this means. You have made a mistake."

The savage paid no more attention to his words than if he had not spoken at all. He gave a few orders in his native tongue to his companions, two of whom placed Frank on Roderick's back and held him there, while a third seized the horse by the bridle, and followed after the chief, who led the way down the ravine. How far they went, or in what direction, Frank could not have told, for his mind was in too great confusion. He was trying to arrive at some satisfactory explanation concerning the Indians' conduct. He had expected that the first action on their part would be to pull his hair, strike at him with their knives and tomahawks, point their guns and arrows at him, and try, by every means in their power, to frighten him. That was the way they always served their prisoners; but thus far he had no reason to complain of their treatment. He wished the chief would explain matters to him, and thus relieve him of suspense.

At the end of half an hour, during which time Frank made several unsuccessful attempts to induce some of the Indians to talk to him, the chief emerged from the ravine, and led the way into a little valley, similar to the one in which Mr. Brent's rancho was located. The sight that here met Frank's gaze astonished him. The valley was filled with lodges, and Frank saw more Indians at the single glance he swept about the camp than he had ever seen before in all his life. Children were playing about in front of the lodges, the women were engaged in various occupations, and the braves, all of whom were in their war-paint, smoked their pipes, and lounged in the shade. Frank was greatly relieved to find that no one noticed the chief and his party. When he first came in sight of the village, he had screwed up all his courage again, expecting no very friendly reception. Bob and Dick had told him that when they were carried into an Indian camp as prisoners, every man, woman, and child turned out to meet them, and to amuse themselves by beating them with switches and clubs; but nothing of the kind was attempted now. Those who looked at Frank at all, merely took one glance at him; and the most of them did not even look up when he passed.

The chief walked straight through the village, and stopped in front of a large wigwam that stood a little apart from the others. At a sign from him, Frank was pulled from his horse, and after his hands had been unbound, a corner of the wigwam, which served as a door, was lifted up, and he was pushed under it. Then the door was dropped to its place, and Frank heard the Indians moving off with Roderick.

The light was all shut out from the inside of the lodge, and as soon as the prisoner's eyes became accustomed to the darkness, he began to look about him. The lodge was about fifteen feet in diameter, and was built of neatly-dressed skins, supported on a frame-work of saplings. Weapons of all kinds were suspended from the walls, the chiefs blanket, bridle, spear, and head-dress occupied one corner, and several buffalo robes, which doubtless served him for a bed, were piled in another. There was no one in the lodge, and Frank, being no longer compelled to wear the appearance of unconcern he had assumed while in the presence of the Indians, gave full vent to his pent-up feelings. His forced calmness forsook him, a feeling of desolation such as he had never before experienced came over him, and covering his face with his hands, he staggered toward the buffalo robes, and threw himself upon them.

"If I only knew what they intend to do with me," sobbed Frank, "I should not feel so badly about it. If they have made up their minds to tie me to the stake, or to compel me to run the gauntlet, why don't they tell me so, and give me a chance to prepare for it? Can it be possible that that race and wrestling match have any thing to do with my capture? The Indians seemed friendly enough when I first visited their camp at the trading-post, and I'd like to know what they mean by taking me prisoner when I wasn't doing any thing to them! What could have induced them to change their camp so suddenly, any how? A few hours ago there were not more than a hundred in the band; now there must be five times as many, and the braves are all in war-paint, too? I can't understand it."

A step outside the lodge, and a rustling among the skins which formed the door, aroused Frank, and he once more made a strong effort to compose himself. The door was raised, and a face appeared at the opening—a dark, scarred, scowling face, which was almost concealed by a fur cap and thick bushy whiskers. Frank was thunderstruck. He leaned forward to examine the face more closely, and then his heart seemed to stop beating, and with a cry of alarm he sprang to his feet. As much as he feared the Indians, he feared this man more.

"Ah, my young cub, are you thar?" growled the visitor, as he stepped into the lodge.

"Black Bill!" exclaimed Frank, in dismay.

"Ay! That's what they call me. 'Member me, don't you? Heered all about me, most likely, from ole Bob and Dick Lewis. They didn't tell you nothin' good of me, I reckon."

Frank tried to speak, but he seemed to have lost all control over his tongue. He had trembled every time he thought of the night he had passed in the camp of the outlaws, and he had hoped that he should never meet them again; but here he was, face to face with one of them, when he least expected it.

"I didn't kalkerlate on seein' you agin," said the outlaw, with a savage smile, "an' I aint agoin' to say that I'm glad to see you now, 'cause I aint. I hate any body that's a friend to Bob an' Dick, an' if I could have my way I'd split your wizzen fur you in a minit. But you b'long to the chief, an' I don't reckon he would see harm come to you."

"To the chief!" repeated Frank, drawing a long breath as if a heavy load had been removed from his shoulders. It was a great satisfaction to him to know that this man could not do as he pleased with him.

"That's what I said," replied the visitor.

"But what does he want to do with me? What is his object in taking me prisoner?" asked Frank.

"He's goin' to make an Injun of you."

"What! I—you don't mean——"

"Sartin I do. It's a fact. He's goin' to take you into the tribe an' make an Injun of you," said the outlaw, in a louder tone.

"And never let me go home again, but keep me here always?" demanded Frank, growing more and more astonished.

"Exactly!"

"Well, he can't do it—he shan't. I don't want to be adopted into the tribe, and I won't be, either."

"I don't reckon you can help yourself, can you?" said the outlaw, with a grin. "You see, the chief used to have a son just about your age—an' a smart, lively young Injun he was, too; but he was killed a little while ago in a scrimmage with the Blackfeet, an' the chief wants another. You're an amazin' chap fur runnin' an' wrastlin' fur one of your years, an' that's the reason he picked you out."

"I don't care if it is; he sha'n't have me. I won't stay here and be his son. Why, I never heard of such a thing. Why don't he select some Indian boy?"

"That's his business, an' not mine. But if you only knowed it, youngster, it's lucky fur you that the chief tuk sich a monstrous fancy fur you, 'cause if you had stayed at the fort, you would have been massacreed with the rest."

"Massacred!" echoed Frank. "Killed!"

"Yes; killed an' scalped. You'll hear of some fun at that tradin'-post afore you are two days older, an' then, if you go down thar, you won't see nothin' but the ashes of it. It would have been done last night if that ar fur trader had kept away from thar. We had to send off arter more help. I don't mind tellin' you this, 'cause 'taint no ways likely that you'll ever have a chance to blab it. But I come in here to ax you about Adam Brent. Where does he sleep?"

Frank did not reply; indeed, he scarcely heard the question, his mind was so busy with what the outlaw had said to him. He knew now where all those Indians came from, and why they were there. The information he had received almost paralyzed him, and he shuddered when he pictured to himself the scenes of horror that would be enacted in that quiet valley, if the savages were permitted to carry out their designs. What would become of his cousin, of the trappers, of Captain Porter, and of himself? Of course his friends would all be included in the massacre, and he, having no one to look to for help, would be compelled to drag out a miserable existence among those savages. But Frank determined that the massacre should not take place. At the risk of his own life he would do something to stop it. His courage always increased in proportion to the number of obstacles he found in his way, and the danger he was in, and now he was thoroughly reckless and determined.

"I axed you do you know where Adam Brent sleeps?" said the outlaw, who had grown tired of waiting for an answer to his question.

"He sleeps in the house, of course," replied Frank.

"Wal, I reckon I knowed that much afore you told me; but what part of the house?"

"I can't tell. I haven't taken the trouble to inquire into Mr. Brent's family matters."

"I'll allow that you tell the truth thar; 'cause if you had axed any questions, you would know that Brent is my own brother, an' that Adam is my nephew. Aint I a nice lookin' uncle?"

"I don't believe a word of it. What do you want with Adam?

"I reckon that's my business, aint it? I only axed you where he sleeps 'cause I've got something to say to him to-night, an' I shouldn't care to have his father hear me blunderin' about the house. I've got a leetle business with ole Bob Kelly, too."

"If you will take my advice you will let him alone," said Frank. "Dick Lewis is his chum now."

"That don't make no sort of difference to me. I'm half hoss an' half buffaler, with a leetle sprinklin' of catamounts, grizzly bars, an' sich like varmints throwed in. I'm one of them kind of fellers as don't stand no nonsense from nobody; an' I'm the wust man in a rough-an'-tumble this side of the States. I aint afeered of Dick Lewis."

Having said this, the outlaw took his departure, and Frank, who had gone through this interview like one in a dream, again seated himself on the buffalo robes to think over what he had heard, and to determine upon some course of action. He had little imagined that he would ever be placed in a situation like this, and he did not wonder now at the hatred which Dick and old Bob cherished toward the Indians. Here they were, awaiting the arrival of reinforcements, and preparing for a descent on the fort; and there were his friends in the valley, all unconscious of the danger hanging over them. There had been no Indian depredations in that section for a long time, and the officers of the fort and the settlers had been lulled into a feeling of security that promised to be fatal to them. They did not dream of such a thing as an attack; the fortifications had not been kept in a state of defense; and unless they were warned of their danger, the success of the Indians would be complete.

"Oh, if they only knew what is going on here!" cried Frank, springing to his feet, and pacing restlessly up and down the lodge. "If I could see them for just one minute, wouldn't these savages meet with a warm reception when they make the attack on the fort? But how will they find it out unless I carry them the information; and how can I effect my escape, surrounded as I am by enemies?"

This thought made Frank almost beside himself. It rendered him desperate; and he resolved that if he could see the least chance for escape, he would make the attempt at once—that very moment. There was not a single instant to be lost, for there was no telling when the Indians would be ready to make the attack. He rushed to the door, tore it open, and looked out. The first object that met his gaze was a warrior standing close beside the lodge, leaning on his spear. He was undoubtedly a sentry, and had been placed there to watch the prisoner. Frank took one glance at him, and then dropped the door to its place, and hurrying to the other side of the lodge pulled up the skins and looked under them. He saw now what he had not noticed before—that the lodge in which he was confined was in the very center of the village. The nearest wigwams were pitched about fifty yards from it, leaving a clear space on each side that was devoted to the holding of councils and dances. Frank knew that he could never cross that space in broad daylight without being discovered and recaptured, and with a look of disappointment on his face, he dropped the skins and crawled back to his seat on the buffalo robes.

If Frank was disappointed in one respect, he was greatly encouraged in another. He had discovered something that went a long way toward strengthening his hopes of escape, and that was that the Indians were not watching him very closely. The guard at the door had not noticed him when he looked out, and this induced the belief that the chief had placed him there simply to keep Frank from roaming about the village, and not because he feared that his prisoner might attempt to escape. That idea had probably never occurred to him. But the chief did not know much about boys, especially such boys as Frank Nelson. He had yet to learn that the young hunter possessed a goodly share of courage and determination, as well as speed and activity.

Frank lay there on the pile of buffalo robes until dark, and then the door opened, and an old Indian woman came in with a small camp-kettle, which she placed upon the ground in the middle of the lodge, and went out again. The contents of the kettle were smoking hot, and the odor that filled the lodge reminded Frank that he had not lost his appetite, and that he was as hungry as a wolf, in spite of all the excitements of the afternoon. An examination of the kettle showed that it contained buffalo meat. Taking his knife from his pocket, Frank seated himself on the ground and began his supper. It was not quite as good as some he had eaten at his quiet little home on the banks of Glen's Creek, but the buffalo meat was nourishing, and when the last vestige of it had disappeared, Frank arose to his feet, put his knife into his pocket, and declared that he felt better.

"I could run, now, if these Indians would only give me half a chance," said he, to himself. "I may yet show them what I can do, unless they station a sentry at the back of this lodge. Now if I only had a drink of water!"

As Frank said this he went to the door again, and there was the guard, standing in the same position in which he had seen him before, leaning on his spear, and gazing off into vacancy. Frank did not believe that he had moved a muscle during the last two hours.

"I say, old fellow!" he exclaimed, "is there any water about here?" Then, fearing that the savage might not understand him, he made a motion with his hand as though he were drinking from a cup.

The guard did not reply, but beckoned to the prisoner to follow him, and led the way through the village toward the ravine from which the chief and his party had entered the valley. Frank, ever on the alert, exulted at this. He knew that the guard was conducting him to a spring, and he sincerely hoped that it would prove to be outside the village. In that event, one Indian, even though he was armed with a spear, could not prevent him from making at least an attempt at escape. If he could get but two feet the start of the sentry, he believed that he could elude him in the darkness. Unfortunately for the success of these plans, however, the spring was not outside the village. It was but a short distance from the place where he had been confined, and all around it were lodges, beside which stalwart warriors lay upon their blankets, smoking their pipes. The least attempt at escape would have brought them around him like a cloud of mosquitoes. He must wait until some more favorable opportunity.

Frank kneeled down beside the spring, and took a long and refreshing drink, and then quietly followed the guard back to his prison. He looked into the wigwams as he passed along, and now that he had in some measure recovered his usual spirits, he began to be interested in what was going on around him; but he did not see any thing to induce him to give up home and friends, and turn Indian. The idea was a novel one to him, and he could have smiled at it, had it not been for the preparations for battle that were every-where visible in the camp—the horses saddled and waiting, the weapons hung upon the poles of the lodge, where they could be seized at a moment's warning, and the braves in war-paint, ready to move at the word. Frank noticed these things, and thought of his friends at the fort. If the expected reinforcements arrived in time, the savages might make the attack that very night.

When Frank found himself once more inside his prison, he stretched himself on the buffalo robes, and waited impatiently for the Indians to go to sleep. How wearily the hours dragged by, and how Frank alternated between hope and fear, can be imagined better than we can describe it. Sometimes he looked upon his escape as an assured thing. When the Indians were all asleep, it would be a matter of but little difficulty for him to creep out of the lodge, and make his way through the village to the ravine. It was easy enough for him to sit there on the buffalo robes and think about it, but when he imagined himself doing it, and pictured to himself the dangers in his way, his hopes fell again; and then, had it not been for the remembrance of what the outlaw had told him, he would have been tempted to abandon all thoughts of escape. If it would have required all the skill and cunning that Dick and Bob possessed to outwit the savages in a case like this, what could an inexperienced boy of sixteen do?

Frank thought the Indians did not intend to go to sleep at all that night. He heard them moving about until a late hour, and it was midnight before the silence that reigned in the camp told him that if he ever intended to carry out the plans he had determined upon, the time had come to do it. His heart beat fast and furiously as he pulled off his shoes, and moved noiselessly across the lodge toward the corner in which the chief had deposited his blanket and spear. He was very deliberate in his movements, and there was need of all his caution; for the guard stood almost within reach of him, and the slightest noise inside the lodge would have brought him in there immediately. Frank threw the chief's blanket over his shoulders, put on the head-dress, picked up the spear, and crept cautiously across the lodge. He threw himself upon his hands and knees, and after listening a moment to assure himself that the guard had not been alarmed, he lifted up the skins which formed the wall of the lodge, and looked out. The camp was as silent as though it had been deserted. On every hand he could see the smoldering embers of the fires by which the savages had cooked their suppers, but not a living being was in sight. Drawing in a long breath he crawled slowly out of the lodge, and after lingering a moment to arrange the blanket about his shoulders, he grasped the spear firmly in his hand, and stole away into the darkness, looking back now and then to make sure that he was keeping the lodge between him and the guard. An intervening row of wigwams finally shut his prison from his sight, and Frank began to congratulate himself on having accomplished the most difficult part of his undertaking.

"When the chiefs reinforcements arrive, and he makes the attack on the fort, and finds the trappers and soldiers ready to receive him, he will wish he had taken a little more pains to watch me," thought Frank, as, with a step that would not have awakened a cricket, he made his way through the village toward the ravine. "If Dick and Bob had been his prisoners he would, no doubt, have kept them bound hand and foot; but I'm a boy, and he thought he had nothing to fear from me. I'll teach him something."

The tall figure of an Indian glided suddenly across the path in front of him, and interrupted his soliloquy. Frank's first impulse was to throw down the spear and blanket, and take to his heels; but remembering in time that he was personating an Indian, and that every thing depended upon his getting out of the village before the guard at the chief's wigwam discovered his flight, he straightened up and boldly approached the Indian, who merely turned his head and looked at Frank, and then disappeared among the lodges. That was another danger passed; and commending the forethought that had induced him to use the chief's clothing as a disguise, he kept on with increased speed toward the mountains, which, to his impatient eye, seemed as far off as when he left his prison. But he was gradually nearing them all the while, and when the last lodge had been left behind, and was concealed from his view by the thick shrubbery and trees that lined the banks of the ravine, his fear and trembling vanished, and it was all he could do to refrain from giving vent to his jubilant feelings. He sat down on the ground to put on his shoes, which he had been thoughtful enough to bring with him, then took the blanket under his arm, and never stopping to think that there might be Indians in front of him as well as behind, he broke into a run and flew down the ravine like the wind.

"I haven't done much to brag of, seeing that I was not very closely watched," thought he, "but still I think I have played those savages a pretty sharp trick. Now, if I only had Dick's speed and experience!"

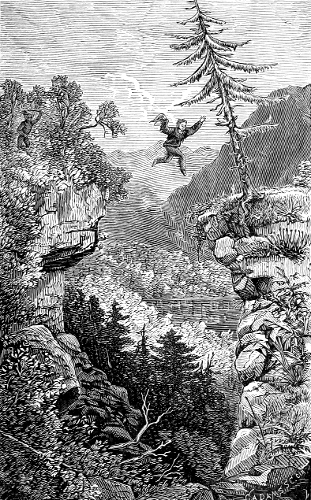

If Frank had possessed the trapper's experience, he would have been much more cautious in his movements, and might, perhaps, have succeeded in reaching the valley in safety. He would have curbed his eagerness which proved fatal to his hopes. There was a party of Indians coming up the ravine with a prisoner; and their quick ears caught the sound of Frank's footsteps long before he came in sight. The prisoner knew who it was approaching at that reckless gate, and so did the Indians, who, at a sign from their leader, quickly concealed themselves beside the path; and when Frank was on the point of passing their ambush, a figure which seemed to rise out of the ground clasped him in its strong arms, and he was a prisoner again almost before he knew it.

The first Indian who confronted him, as he was lifted to his feet, was the chief, who astonished his prisoner by the reception he gave him. He seemed somewhat surprised to see him there, but he did not appear to be angry. He looked at the blanket and spear, then at Frank, and giving him a hearty slap on the back said, approvingly:

"Good boy! Make fine Injun, some day!"

Frank, although his face was very pale, and he was trembling in every limb, was not as badly frightened now as when he first found himself in the power of the savages. For himself he was not at all concerned, for he did not stand in any fear of bodily harm; but there were his friends in the valley, whom he was so anxious to warn of their danger! It was of them he thought, and not of himself.

"I say, youngster," said a cheery, familiar voice, close at his elbow, "you've got a few things to larn yet, haint you? When a feller is in an Injun country he can't go tearin' through the woods as you did a minute ago. I can't shake hands with you, 'cause I am tied hard and fast."

"Dick Lewis!" cried Frank, in alarm. He was too astonished to speak again immediately. The redoubtable trapper was always turning up most unexpectedly, and generally, too, at just the moment when his services were most needed; but on this occasion he was not in a condition to assist his young friend. For the first time in his life Frank was not glad to see Dick. He would rather have had him a hundred miles from there, for he knew that the treatment the trapper would receive at the hands of his savage foes would be very different from his own.

"Well, what are you doing here?" asked Frank, at length.

"I might ask you the same question, I reckon," replied Dick. "What business had you to go roamin' off alone in the mountains, arter I had told you to keep your eyes open fur these Injuns? I knowed what was up the minute Archie come home without you; an' me an' Bob set out to find you. Bob's old legs tuk him safe out of danger, but I was ketched. I am here 'cause I can't help myself."

"But, Dick, does Captain Porter know that these Indians have suddenly turned hostile?"

"Turned!" exclaimed Dick. "They've been hostile ever since they was born. Of course he knows it. Come up closer, youngster, so that I can whisper to you, an' I'll tell you something."

While this conversation was going on, the prisoners were being conducted up the ravine toward the camp. The chief led the way, two Indians, who stepped exactly in his tracks, followed close at his heels, Frank and Dick, who walked side by side, came next, and two more Indians brought up the rear. The savages made no attempt to restrain their prisoners from talking, and Frank was glad it was so.

"The Cap'n didn't like the way these Injuns acted this mornin', no more'n I did," continued the trapper, in a low tone. "He spoke to the major, an' told him that if he knowed when he was well off he would look out fur things a leetle; an' the ole feller tuk the hint an' set his soldiers to work on the fort. Thar's too many ole trappers down in that valley, an' they can't be tuk by surprise."

"You don't know how overjoyed I am to hear that," whispered Frank, who now breathed more freely than at any time since he had fallen into the hands of the savages. "Then Archie will be safe, won't he?"

"Sartin he will, unless he goes about pokin' his nose into danger like he allers does. He's jest spilin' to have his har raised, Archie is, an' it was all me an' ole Bob could do to keep him from comin' with us when we set out to look fur you. The chief's goin' to make an Injun of you, I can see that easy enough."

"That's what Black Bill says."

"Black Bill!" echoed the trapper. "Is he about here? Wal, if I don't settle with him ole Bob will, so it's all the same. I kinder thought, by the squint in the chief's eye, that it would have been better fur you if you had kept away from that camp," he continued. "Injuns don't giner'ly take sich a monstrous shine to white boys fur nothing. It won't be long afore you'll have a chance to see how the red skins treat their prisoners. Mebbe the chief will get up a show fur you to-night."

"A show!" repeated Frank.

"Yes. How would you like to see me tied to the stake, or runnin' the gauntlet?"

No one, to have heard the trapper speak these words, would have imagined that he had any fears that such would be his fate; but Frank knew that he expected nothing else.

"The chief is awful mad at me," continued Dick. "Thar were 'leven men in his party, when me an' ole Bob first diskivered 'em, an' now you don't see but four, do you? Thar's four more behind us, bringin' up the three that me an' Bob rubbed out. I'll have to stand punishment fur that; but I don't reckon that burnin' me or slashin' me with tomahawks will bring to life all the braves I have sent to the happy huntin' grounds."

A long, mournful yell from the chief interrupted the conversation. Frank looked up and saw the village in plain sight. The chief had given that yell to warn the camp of his arrival. Dick called it the "death-whoop," and said that one object of it was to inform the warriors that some of those, who had gone out on the scout with the chief, had fallen by the hands of their enemies. Presently an answer came echoing through the woods, then another, and another; and when they emerged from the ravine, Frank found the village, which had been so quiet when he left it but a few minutes before, alive with men, women, and children, who seemed wild with excitement and rage. When their eyes rested on the trapper, they gave utterance to savage yells of exultation, and almost before Frank was aware of it, he was standing alone, gazing after a crowd of struggling, frantic Indians, who were bearing his fellow prisoner toward the chief's wigwam. Tomahawks and knives were flourished in the air close to Dick's face, arrows and rifles were pointed at his breast, spears were thrust at him, and now and then hickory switches in the hands of those behind him, fell with stinging force on his head and shoulders. Before he was carried out of sight, his face was bleeding from more than one wound; but Frank looked in vain for any expression of fear. The trapper was apparently as calm and self-possessed as he would have been had he at that moment been smoking his pipe on the porch of Mr. Brent's rancho. He never winced when the weapons of his savage foes passed within an inch of his person—indeed, one would have thought, from his manner, that he did not see them all. Never before had Frank witnessed such an exhibition of courage and fortitude.

When the trapper had disappeared from his view, Frank, who had stood rooted to the ground, horrified by the scene he was witnessing, awoke to a sense of his own situation, and began to look about him. Although there were Indians on all sides of him, no one seemed to take the least notice of him. His hands were tied behind his back, but he could move about as he pleased, for his feet were free. Scarcely knowing what he was doing, he followed in the direction the crowd had gone; and when he arrived at the chief's lodge he found that some unusual event was about to take place. The yells were hushed, and most of the Indians were gathered in a body on one side of the council ground, in the center of which two or three warriors were busy kindling a fire. Upon looking around for the trapper, he discovered him at the opposite side of the ground, standing with his back to a post, to which he was securely bound. Near him stood a couple of armed Indians; and when Frank approached his friend, they motioned him angrily to retire.

"Oh, don't I wish that my hands were unbound, and that I could have the free use of my knife for just one minute?" groaned Frank, as he reluctantly retraced his steps toward the chief's wigwam. "Dick wouldn't be in that fix long. He has saved me more than once, and I would risk any thing, if I could do as much for him now. Where is Bob, that he don't bring the trappers up here and attack these Indians?"

Frank stood off by himself and watched the preparations going on around him, and wondered what would be the next torture the savages would devise for their prisoner. He could not have been more terrified if he had occupied Dick's place, and had been every moment expecting to hear the death sentence passed upon him. He did not like the deliberation and gravity with which the Indians conducted their proceedings, nor the scowls of mingled hatred and triumph which they threw across the council-ground toward the helpless trapper. He thought things looked exceedingly dark for his friend.

The huge fire that had been kindled by the warriors was well under way at last, and a dozen chiefs walked out from among their companions, and seated themselves in a circle around it. The first business in order was smoking the pipe of peace. The pipe was brought in by an aged warrior, who lighted it with a brand from the fire, and was about to present it to the principal chief, when the proceedings were interrupted by the arrival of a party of four men, who walked up to the fire without ceremony, and seated themselves near it. Frank recognized them at a glance; and that same glance showed him that they had not come alone. They had brought a prisoner with them, and he was standing near the trapper, with his hands bound behind his back.

For an hour and a half after Frank left him, Archie walked up and down the banks of the brook, pulling out trout of a size and weight that astonished him. When nearly two hundred splendid fish had been placed upon his string, he put his line into his pocket, leaned his pole against a tree where he knew he could find it again if he should happen to want it, mounted his horse, and rode slowly toward the rancho, keeping a good lookout on every side for his cousin, and wondering what had become of him. It was getting late. The sun had sunk below the western mountains, the shadows of twilight were creeping through the valley, and Archie began to fear that Frank was in a fair way to pass the night among the grizzlies. He did not find him at the rancho; Adam had not seen him, and neither had Dick, who, upon finding that Archie had returned alone, pulled off his sombrero, and scratched his head furiously, as he always did when any thing troubled him.

"Where's the boy that fit that ar Greaser?" he asked, with some anxiety in his tone.

"I am sure I don't know," was the reply. "He went into the mountains to hunt up an elk for supper, and I haven't seen him since."

"The keerless feller!" exclaimed the trapper.

"He'll have to camp out all night if he doesn't come back pretty soon," continued Archie. "Won't he have a glorious time among the bears and panthers? I wish I had gone with him, for I know he will be lonesome."

"You can thank your lucky stars that you stayed at home. Thar's a heap wusser things in the world than grizzlies an' painters."

The tone in which these words were spoken made Archie uneasy; and when Dick drew old Bob and the Captain off on one side, and held a whispered consultation with them, he began to be really alarmed. He had never seen the trapper act so strangely. Heretofore, when Frank had got into trouble, Dick had always said: "I jest know he'll come out all right;" but he did not say so now. Archie could see that there was something in the wind that he did not understand.

While the Captain and his men were conversing, a trapper galloped up to the porch, and hurriedly ascending the steps, communicated in a whisper what was plainly a very exciting piece of news, for an expression of anxiety overspread the Captain's face, old Bob thumped the floor energetically with the butt of his rifle, and Dick once more pulled off his sombrero and dug his fingers into his hair. Almost at the same moment a second horseman approached from another direction, and he had something to tell that increased the excitement. The Captain listened attentively to his story, and then gave a few orders in a low tone to Dick and Bob, who shouldered their rifles, sprang down the steps, and stole off into the darkness like two specters. They had not made many steps before Archie was at their heels.

"Now, then, you keerless feller, jest trot right back to the house agin," said Dick.

"If you are going out to look for Frank I want to go too," replied Archie. "I can keep up with you."

"Go back," repeated the trapper; "you'll only be in the way. Thar's goin' to be queer doin's in this yere valley, an' you'll see enough to make you glad to stay in the house."

"What's up here, any how?" asked Archie, as he mounted the steps that led to the porch where Adam Brent was waiting for him.

"Indians," was the reply.

"Indians!" repeated Archie, who now thought he understood what the trapper meant when he said that there were things in the world more to be dreaded than bears and panthers. "You surely don't expect trouble with them?"

"That's what they say," replied Adam, coolly. "I heard Captain Porter tell father that they would be down on us, like a hawk on a Junebug, before we see the sun rise again."

"Well, I—I—Eh!" stammered Archie, almost paralyzed by the information.

"Oh, it's the truth. In the first place, they changed their camp very suddenly this afternoon, and without any cause; and since then they haven't showed themselves in the valley. That's a bad sign. When you know there are Indians about you, and you can't see them, look out for them, for they mean mischief. But when they are all around you, and you have to watch them closely to keep them from stealing every thing you've got, there's nothing to fear. In the next place, one of Captain Porter's trappers, who was out hunting this afternoon, said that he crossed the trail of a war party, numbering at least five hundred men. Another trapper brought the information that there is a large camp of Indians about ten miles back in the mountains, and that the braves are all in war-paint. Father says it is plain enough to him that they have determined upon a general massacre of all the settlers in the country. There'll be fun in this valley before morning, and you'll hear sounds and see sights you never dreamed of."

Archie was astounded—not only at the news he had heard, but also at the free and easy manner in which it was communicated. He was trembling in every limb with suppressed excitement and alarm; and here was this new friend of his standing with his hands in his pockets, and talking about a fight with the Indians—which would be delayed but a few hours at the most—with as much apparent indifference and unconcern as if it had been some holiday pastime. But then Adam was accustomed to such things. The house in which he lived has been used as a fort in days gone by, and when trouble was expected with the savages, the settlers, for miles around, would flock into it for protection. It had withstood more than one siege, and Adam, before he was strong enough to lift a rifle to his shoulder, had heard the war-whoop echoing through the valley, and had molded bullets and cut patching for the men who were standing at his father's side, defending the house against the assaults of the savages. Archie could have told of things that would have made Adam's hair stand on end. He had ridden in the cars and on steamboats; and he had held the helm of the Speedwell in many a race around Strawberry island, when the white caps were running, and the wind blowing half a gale. Adam, in these situations, would have been as badly frightened as Archie was now.

While the latter was thinking over what he had heard, and wishing that his friend could impart to him some of his indifference and courage, Mr. Brent, who, with his men, had been engaged in collecting the valuables in the house, and loading them into a wagon for transportation to the fort, approached, and said to his son:

"Adam, get your rifle and ammunition, and go down to the fort and stay there until I come. Archie, you had better go with him."

Archie thought this good advice. If the Indians had really determined on making a descent into the valley—and he knew that Mr. Brent had had too much experience to be deceived in such matters—the sooner he found a place of safety the better it would be for him. He had been considerably disappointed because he had not been allowed an opportunity to assist the settlers in their fight with Don Carlos and his men, but he had never expressed a desire to take part in a battle with the Indians. He trembled at the thought; and he was almost afraid to ride through the grove with Adam. He held his rifle in readiness for instant use, and so nervous and excited was he, that it might have been dangerous for even a friendly trapper to approach him unexpectedly. He and Adam reached the fort, however, without encountering any of their enemies; and then Archie drew a long breath of relief, and began to feel more like himself.

Every one of the hundred soldiers comprising the garrison was hard at work; and so were the trappers. Some were engaged in repairing the palisades, some were covering the roofs of the buildings with earth, to prevent the savages from setting them on fire with lighted arrows, others were cleaning and loading the weapons, and every thing was done without the least noise or confusion. Not a word was spoken above a whisper; the men moved about with cautious footsteps, and a person standing at a distance of fifty yards from the fort, could not have told that there was any one stirring within its walls. One thing that surprised Archie was, that among all these men, who had fought the Indians more than once, and who knew just what their fate would be if the fort proved too weak to resist the attacks of their savage foes, there was not one who seemed to be in the least concerned. There were some pale faces among them—pale with excitement rather than fear—but their manner was quiet and confident, and Archie began to gather courage.

His first care was to look up a place of safety for his horse. The garrison being composed entirely of cavalrymen, there was plenty of stable room in the fort, and Archie soon found an empty stall, in which he tied the mustang; and after strapping his revolvers around his waist, and filling his pockets with cartridges for his rifle, he went out to look about the fortifications. He found Adam in the soldiers' quarters, sitting beside a fire, and engaged in running bullets. He kept him company for a while, but he was too uneasy and excited to remain long in one place, and finally he went out again, and resumed his wanderings about the fort. He watched the soldiers at their work, looked at the loop-holes, and tried to imagine how he should feel standing at one of them when the bullets and arrows were whistling about his ears, and the fort was surrounded by hundreds of yelling Indians thirsting for his blood, and at last he found his way out of the gate to the prairie where Frank had run the foot-race a few hours before. How lonesome the place seemed now, and what an unearthly silence brooded over it! Archie felt his courage giving away again, and aroused himself with an effort.

"I am getting to be a regular coward," said he, to himself. "If Frank were here he would be ashamed of me. I'd like to know where he is, and what he is doing. I hope he has made his camp where the Indians will not stumble upon it. There's the Captain going back to the house. If it is safe there for him, I guess it is safe for me, too."

Archie shouldered his rifle, and hurried off in the direction the Captain had gone. He passed through the grove in safety, and when he reached the house he found that Mr. Brent and his men were still engaged in collecting all the movable property, and hauling it to the fort. The former knew that all his stock, barns, and crops would be destroyed, and it was his desire to save as much of his household furniture as possible.

Archie leaned his rifle in one corner, and worked with the rest until the wagon was loaded, and then sat down on the porch to await its return from the fort. He wished he had gone with it before many minutes had passed over his head, for scarcely had the wagon disappeared when he heard a stealthy step behind him, and, upon looking up, he saw three trappers standing close at his elbow. Although he was startled by their sudden appearance, he was not alarmed, for he thought that he recognized them as some of the men belonging to Captain Porter's expedition; but a second glance showed him that they were strangers. He sprang to his feet, and, boldly confronting the men, waited for them to make known their business. They looked at him closely for a moment, and then one of them said to his companions:

"That's him, aint it?"

"I reckon it is," replied another. "Now, my cub, no screechin' or fussin'. If you make the least noise, you're a goner."

Archie did not hear all this warning, for, while the trapper was speaking, he had seized the boy in an iron grasp, and pressed a brawny hand over his mouth to stifle his cries for help; another tore his revolvers from his waist; the third caught up his feet and held them firmly under his arm; and, before Archie could fairly make up his mind what was going on, he was being carried rapidly across the valley toward the mountains. Astonished and enraged, he struggled furiously for a time, but all to no purpose; he was held as firmly as if he had been in a vice; and, exhausted at last by his efforts, he lay quietly in the grasp of his captors, wondering at this new adventure, and trying in vain to find some explanation for it. He was not kept long in ignorance, however, for in a few minutes the trappers had carried him across the valley, through the willows that skirted the base of the mountains, and into a deep, thickly-wooded ravine, and set him down in front of a camp-fire, before which stood a tall, fierce-looking man leaning on his rifle.

Archie was so bewildered that, for a minute or two, he could not have told whether he was awake or dreaming. He swallowed a few times to overcome the effect of the choking he had received, rubbed his eyes, and looked about him; and all the while the tall trapper stood regarding him, with a savage smile on his face, while his three companions seated themselves beside the fire, and coolly proceeded to fill their pipes.

"It's him, aint it, Bill?" asked one, at length.

"Yes," replied the person addressed, still looking fixedly at his prisoner, and evidently enjoying his bewilderment, "it's him. Seems to me you might have a good word to say to your uncle, seein' it's so long since we've met one another."

"My uncle!" exclaimed Archie, now for the first time recovering the use of his tongue.

"Sartin. You aint agoin' to deny it? You aint agoin' back on me, are you? I've been through a heap since I seed you last—I've been chawed up by bars an' catamounts, an' been shot at by Injuns an' white fellers, an' mebbe I've changed a leetle. I never did brag much on my good looks, but I'm your uncle, fur all that."

"You!" almost shouted Archie, gazing in amazement at the trapper's dark, scarred face; "you my uncle! Not if I know who I am, and I think I do. Do you take me for a lunatic, or are you crazy yourself?"

"Nary one, I reckon. I take you fur my nephew—Adam Brent—an' I know what I'm sayin'."

"Well, if Adam has such a looking uncle as you are, I am sorry for him. You've made a great mistake. My name is Winters, if it will do you any good to know it."

"No, I reckon not," replied the trapper, who seemed to be greatly pleased at his prisoner's pluck and independence. "I reckon you're Adam Brent."

"I guess I ought to know what my name is, hadn't I?" exclaimed Archie, angrily. "Who are you, anyhow, and what business have you to take me away from my friends?"

"I'm your uncle—Bill Brent—Black Bill fur short; an' as fur the business I have in takin' you prisoner, it's the business every man's got to right the wrongs that's been done him. That's what's the matter."